LOGIN TO YOUR ACCOUNT

Create a new account.

Can't sign in? Forgot your password?

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Request Username

Can't sign in? Forgot your username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

Change Password

Your password must have 8 characters or more and contain 3 of the following:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Verify Phone

Your Phone has been verified

- This journal

- This Journal

- sample issues

- publication fees

- latest issues

Urgent and long overdue: legal reform and drug decriminalization in Canada

Information & authors, metrics & citations, view options, introduction: employing a human rights approach, the impact of covid-19, covid-19: the impact of the pandemic on pwud and harm reduction efforts, roadmap of the report, 1. the legal context of criminal law, 1.1. a brief history of canada's drug laws.

“The approach set out in this guideline directs prosecutors to focus upon the most serious cases raising public safety concerns for prosecution and to otherwise pursue suitable alternative measures and diversion from the criminal justice system for simple possession cases”.

1.2. The purposes of the criminal law

[The] criminal law should be employed to deal only with that conduct for which other means of social control are inadequate or inappropriate, and in a manner which interferes with individual rights and freedoms only to the extent necessarily for the attainment of its purpose.

As the most serious form of social intervention with individual freedoms, the criminal law is to be invoked only where necessary, when the use of other means is clearly inadequate or would depreciate the seriousness of the conduct in question. As well, the Principle suggests that, even after the initial decision has been made to invoke the criminal law, the nature or extent of the response of the criminal justice system should be governed by considerations of economy, necessity and restraint, consonant of course with the need to maintain social order and protect the public.

In the boundary between criminal law and private morality, various concerns have been expressed about either decriminalizing or diverting from criminal prosecution many acts widely considered crimes of “going to Hell in one's own fashion”, such as drug and gambling offences. Some of these offences are considered too minor to be treated with a heavy hand of the criminal law; others are thought to be more effectively dealt with through public education or regulation.

When we take drugs we do so to alter ordinary waking consciousness. The criminal control of a citizen's desire to alter consciousness is unnecessary. We have other at least equally useful and less punitive methods available for control: taxation, prescription, and prohibition of public consumption. But most important, we should confront our own hypocrisy. We can no longer afford the illusion that the alcohol drinkers and tobacco smokers of Canada are engaging in methods of consciousness alteration that are more safe or socially desirable than the sniffing of cocaine, the smoking or drinking of opiates, or the smoking of marijuana.

The answer is not to usher in a new wave of prohibitionist sentiment against all drugs, nor is the answer to allow the free-market promotion of any psychoactive. The middle ground is carefully regulated access to drugs by consenting adults, with no advertising, fully informed consumers, and taxation based on the extent and harm produced by use. There is a need for tolerance, for both tobacco and heroin addicts. And there is a need for control of the settings and social circumstances of drug use. There are no good, or bad, drugs, though some are more toxic, some are more likely to produce dependence, and some are very difficult to use without significant risks…. The task is to dismantle the costly and violent criminal apparatus that we have built around drug use and distribution, mindful that our overriding concern should be public health, not the self-interested morality of Western industrial culture.

1.3. Alternatives to criminalization

To promote alternatives to conviction and punishment in appropriate cases, including the decriminalization of drug possession for personal use, and to promote the principle of proportionality, to address prison overcrowding and overincarceration by people accused of drug crimes, to support implementation of effective criminal justice responses that ensure legal guarantees and due process safeguards pertaining to criminal justice proceedings and ensure timely access to legal aid and the right to a fair trial, and to support practical measures to prohibit arbitrary arrest and detention and torture.

Review and repeal punitive laws that have been proven to have negative health outcomes and that counter established public health evidence. These include laws that criminalize or otherwise prohibit gender expression, same sex conduct, adultery, and other sexual behaviours between consenting adults; adult consensual sex work; drug use or possession of drugs for personal use; sexual and reproductive health care services, including information; and overly broad criminalization of HIV non-disclosure, exposure, or transmission.

Under international law, Canada has both important latitude under the drug control conventions, and important obligations under human rights treaties it has ratified. It can and should use that latitude in the realm of drug control to better respect, protect and fulfil the human rights it has pledged to uphold, and which are also embodied to various degrees in its own constitution.

2. Forms of decriminalization

2.1. distinction between de jure (in law) and de facto (in practice), 2.2. national de jure decriminalization, 2.2.1. portugal, 2.2.2. spain, 2.3. national de facto approaches, 2.3.1. switzerland, 2.3.2. the netherlands, 3. law reform proposals in canada, 3.1. decriminalization efforts in canada, 3.2. law reform proposals, 3.2.1. city of vancouver: the vancouver model, 3.2.2. province of british columbia, 3.2.3. federal law reform proposals, 3.2.4. expert reports and recommendations, 4. constitutional considerations, 4.1. section 7 of the charter : the right to life, liberty, and security of the person, 4.1.1. criminalization and the right to liberty, 4.1.2. criminalization and the right to life and to the security of the person.

… hospitals dispense opioids every day to relieve pain. These drugs are not killing people because the quality of the supply is regulated, the dosages are managed, ingestion is overseen and, should a problem arise, there are trained people on hand who can intervene and who are not made afraid by the spectre of criminalization and stigma. Proponents of harm reduction argue that context matters and shunting drug consumption out of sight while criminalizing and stigmatizing it does the opposite of keeping people safe.

4.1.3. Criminalizing possession for personal use: the principles of fundamental justice

4.2. criminalizing possession: discrimination, 4.2.1. section 4(1) of the cdsa.

There is now copious evidence of the harms of criminalizing simple possession particularly to vulnerable people. Since criminalization of drug possession directly leads to both individual and systemic stigma, it supports discrimination against people who use drugs and prevents people from seeking services. It also undermines the development of health services because needed resources are diverted to the criminal justice system (including correctional facilities) and because people with problematic drug use, when regarded as criminals, are not seen as deserving of services.

4.3. Section 1 of the Charter

The current prohibitionist approach to drug policy has failed to achieve its stated ends: to prevent the growth of illegal drug markets, to curtail use of illegal substances, and to prevent harms associated with the use of these substances. Instead, harms have been magnified through the creation, in reaction to interdiction, of a highly toxic illegal drug supply, and the criminalization, stigmatization, and marginalization of individuals – many of whom have opioid use disorder, a known chronic, relapsing health condition. In addition, massive profits have been generated for violent criminal enterprises involved in the illegal drug market.

5. Ending the harms associated with criminalization

5.1. stigma, 5.2. drug toxicity, 5.3. barriers to harm reduction, 5.4. health and social inequities, 5.5. harms associated with incarceration, 6. decriminalizing to reduce harms, 6.1. recommendations for law reform, 6.1.1. procedural recommendations, 6.1.2. recommended pillars of a canadian decriminalization model, pillar #1: consistent application of uniform requirements across the country, pillar #2: reducing opportunities for discretionary decision-making by police and prosecutors, pillar #3: determining thresholds: setting realistic regulatory policy, pillar #4: addressing “splitting and sharing”, pillar #5: retroactive expungement of criminal records, 6.1.3. implementing a canadian decriminalization model: a staged approach, stage one: immediate policy changes, stage two: regulatory amendments, stage three: introducing a new comprehensive legislative framework, 7. conclusion, legislation a, information, published in.

Data Availability Statement

- drug policy

- harm reduction

- criminal law

- Integrative Sciences

- Public Health

- Science and Policy

Affiliations

Author contributions, competing interests, other metrics, export citations.

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

There are no citations for this item

View options

Share options, share the article link.

Copying failed.

Share on social media

Previous article, next article.

Decriminalizing drug use is a necessary step, but it won’t end the opioid overdose crisis

Assistant Professor in the School of Criminology, Simon Fraser University

Disclosure statement

Alissa Greer receives funding from Simon Fraser University and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. Dr. Greer is an assistant professor in the School of Criminology at Simon Fraser University, a research affiliate at the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, and a senior associate at Bunyaad Public Affairs.

Simon Fraser University provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA.

Simon Fraser University provides funding as a member of The Conversation CA-FR.

View all partners

Media, policy-makers, advocates and the public claim that decriminalization will make drug use safer and save lives . But can it?

Decriminalization has been somewhat of a policy buzzword in recent years, with ample media coverage . It comes with both public and government support.

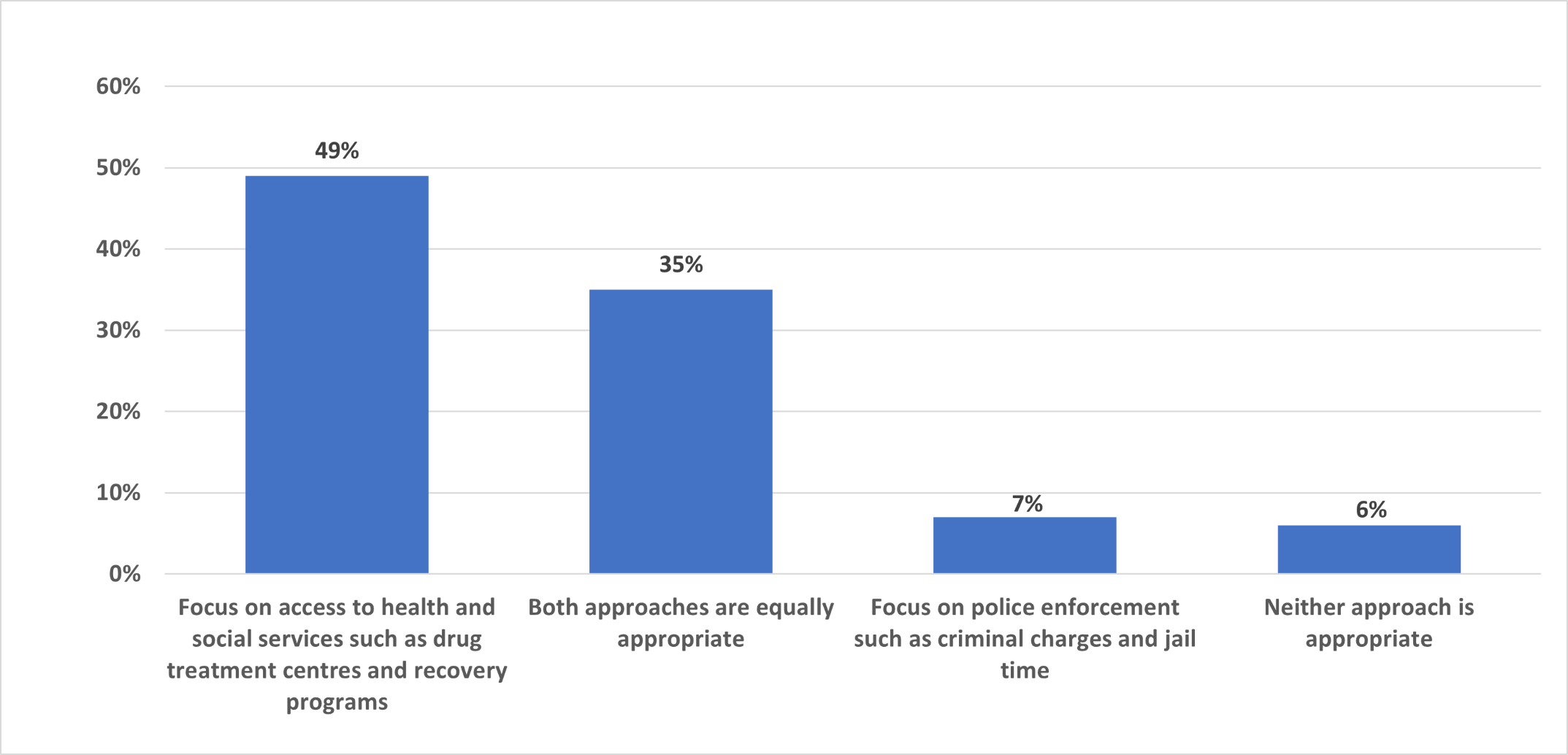

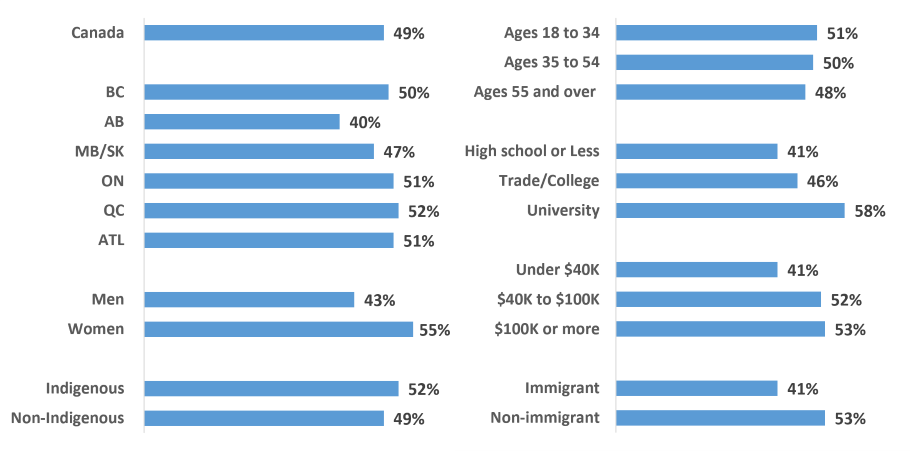

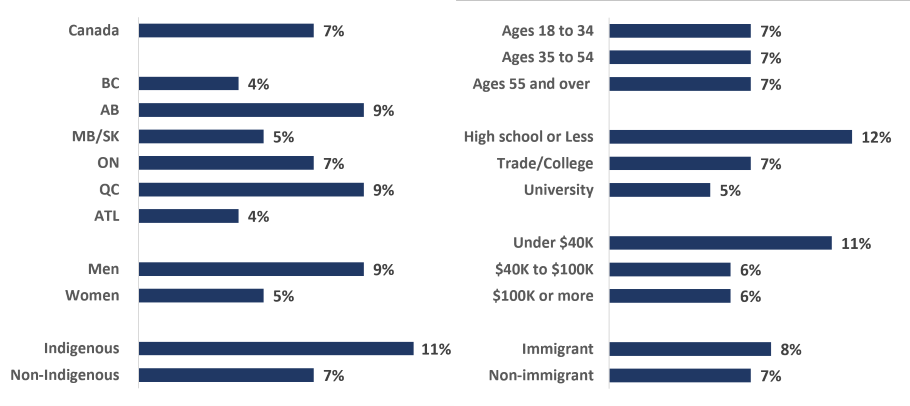

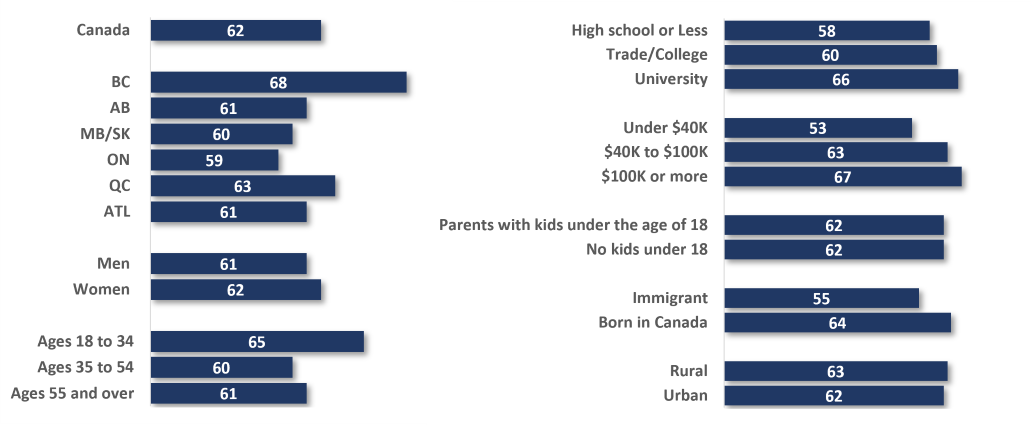

A 2020 survey of more than 5,000 Canadians showed that the majority (59 per cent) favour the decriminalization of drugs . The Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police has also publicly supported decriminalization, along with British Columbia’s chief public health officer .

Such support has also come with action. This year, the City of Vancouver submitted an application to Health Canada for an exemption from Canada’s Controlled Drugs and Substances Act — a policy reform referred to as the Vancouver Model of decriminalization .

An alternative response

In the simplest terms, decriminalization is an alternative response to criminal penalties for simple possession. The most recent data shows there were over 48,000 drug-related offences in Canada in 2019, most of which were for possession for personal use.

The criminalization of drugs results in significant health, social and economic harms , particularly to those who are homeless, experiencing mental health issues, racialized or Indigenous. By eliminating a criminalized response to drug possession, drug policy reform efforts can minimize the contact between people who use drugs and the criminal justice system, and may increase their connection to health and social systems .

However, alongside recognition of the ineffectiveness of criminalization and support for an alternative model, we need to be realistic with our expectations of what decriminalization can do.

Decriminalization versus regulation

Decriminalization does not mean that people can buy cocaine and heroin at the store as they would alcohol and tobacco. Only legal regulation can do that. Legal regulation, which drug policy advocates endorse , includes rules to control who can access what drug and when, as opposed to a free market or full legalization.

An example of legalization is Canada’s Cannabis Act , which provides a legal framework to control the production, sale and possession of cannabis.

Unlike legal frameworks applied to the supply of drugs, decriminalization does not promote a “safer supply” of drugs. The overdose crisis is driven by an unpredictable, illegal drug supply that is marked with adulterants, contaminants and other substances . Decriminalization won’t directly impact this supply of drugs, they will continue to be made in unregulated ways and places.

The illegal drug market will continue to be criminalized, unpredictable and precarious, and people will continue to be unsure of what’s in their drugs (in lieu of better drug checking services or how potent they are. Under a decriminalized model, the overdose risk will inevitably remain high.

That said, decriminalization is still a necessary step in addressing the crisis.

The benefits of decriminalization

Decriminalization changes the way we think about drugs. Drug use will no longer be treated as a criminal issue, but instead a health and social one . This means that instead of addressing drugs through handcuffs, the focus will be on the root causes of drug use, including inequities rooted in housing and health care.

Decriminalization saves governments money. A large proportion of the justice system — police, courts, prisons — are occupied with drug-related crimes . As seen in other decriminalized jurisdictions such as Portugal , it can reduce the demands and costs to this system.

Considering the demonstrated need for addiction and mental health resources, the money saved could be well spent elsewhere, such as community-led responses, health care, housing and social programs.

Decriminalization positively impacts people’s lives. Especially for those targeted by drug law enforcement, namely poor, homeless and racialized people who use drugs, decriminalization can have a positive impact .

For example, eliminating criminal records related to drug possession offences promotes opportunities for people to access employment and housing. Interactions between people who use drugs and police can also be reduced or, better yet, won’t happen at all.

Decriminalization reduces stigma. Negative views towards drugs and people who use them is a major factor in the overdose crisis . By reshaping the way our family, friends and the medical profession think about drugs, drug use can be talked about more openly and honestly.

Reducing stigma can also encourage people who use drugs to talk to their doctors about prescription-based therapies. At the very least, it will help bring drug use out from isolation, where fatal overdoses tend to be the highest .

Decriminalization encourages people to call 911 at the scene of an overdose. Fear of police is currently a barrier to this. Although people cannot be charged with simple possession at the scene of a drug overdose under drug-related Good Samaritan laws , fear of the police is still a deterrent . Legislation that decriminalizes drug possession can reassure people that they will not face criminal penalties. And police will no longer need to respond to calls about overdoses.

Decriminalization is harm reduction. Although some people fear that decriminalization may increase or encourage drug use, this concern is simply not supported by evidence. We know from dozens of countries, states and cities that have decriminalized drugs that use does not significantly increase . In some places, it has actually decreased .

Decriminalization also lowers overdose and disease rates, while increasing people’s access to social services and health care. In this way, a decriminalization model is a basic harm reduction approach, mitigating the harms experienced by people who use drugs by eliminating or minimizing the source of those harms: criminalization.

A critical step

Overall, the notion of decriminalization is not a panacea or a standalone solution to the harms of drug prohibition — but it is a critical step in the right direction. It will have a positive impact on the lives of so many people who are harmed daily from criminalization.

However, in recognizing the limitations of decriminalization models , governments and other stakeholders can refocus efforts on what does directly impact the overdose crisis: a safer supply. Decriminalization must be paired with greater access to safer pharmaceutical alternatives to the toxic and illegal drug market.

That’s what will save lives.

Caitlin Shane, staff lawyer at Pivot Legal Society, co-authored this article.

- Harm reduction

- Opioid crisis

- Health Canada

- Illegal drugs

- Decriminalization

Professor of Indigenous Cultural and Creative Industries (Identified)

Communications Director

Associate Director, Post-Award, RGCF

University Relations Manager

2024 Vice-Chancellor's Research Fellowships

The rise and fall of drug decriminalization in the Pacific Northwest

- Full Transcript

Subscribe to This Week in Foreign Policy

Keith humphreys and keith humphreys esther ting memorial professor and professor of psychiatry - stanford university vanda felbab-brown vanda felbab-brown director - initiative on nonstate armed actors , co-director - africa security initiative , senior fellow - foreign policy , strobe talbott center for security, strategy, and technology.

September 17, 2024

- Drug decriminalization policies in San Francisco, Oregon, and British Columbia reduced drugs arrests, but spurred public concerns about safety.

- Different cultural and social contexts shape the designs and outcomes of decriminalization policies.

- Effective drug policy requires a balanced approach, avoiding extremes between harsh criminalization and complete decriminalization.

- 34 min read

The promise was that harm reduction would at least reduce the harm, but in places like British Columbia, overdoses kept going up. Keith Humphrey's

In this episode, host Vanda Felbab-Brown interviews Stanford professor Keith Humphreys about drug decriminalization in San Francisco, Oregon, and British Columbia. They discuss the origins and motivations for the dramatic policy change in 2020; the design of the policies, including the similarities with and differences from the decriminalization policies in Portugal; and the outcomes in the Northwest, including in terms of drug use, dealing, arrests, and property crime. Humphreys also explains what caused backlash against such policies and, ultimately, policy reversals. Humphreys emphasizes balanced policies, strong community engagement, and evidence-based public health service provision as the way forward.

- Listen to The Killing Drugs on Apple , Spotify , or wherever you like to get podcasts.

- Watch episodes on YouTube .

- Learn about other Brookings podcasts from the Brookings Podcast Network .

- Sign up for the podcasts newsletter for occasional updates on featured episodes and new shows.

- Send feedback email to [email protected] .

FELBAB-BROWN: I am Vanda Felbab-Brown, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, and this is The Killing Drugs . With more than 100,000 Americans dying of drug overdoses each year, the fentanyl crisis in North America, already the most lethal drug epidemic ever in human history, remains one of the most significant and critical challenges we face as a nation. In this podcast and its related project, I am collaborating with leading experts on this devastating public health and national security crisis to find policies that can save lives in the United States and around the world.

On today’s episode, I am exploring the criminalization experiences and challenges in San Francisco, Oregon, and British Columbia. My guest is Doctor Keith Humphreys, who is the Esther Ting Memorial Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University. He’s also a senior research scientist at the Veterans Affairs Health Services Research Center in Palo Alto, and an honorary professor of psychiatry at the Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London. He served on the White House Commission on Drug-Free Communities during the Bush Administration, and as a senior policy adviser in the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy under President Obama. His project paper is titled “The Rise and Fall of Pacific Northwest Drug Policy Reform 2020–2024.”

Keith, thank you for joining me.

HUMPHREYS: Thanks so much for having me, Vanda. I am always delighted to have a chance to talk to you.

FELBAB-BROWN: Well, thanks very much. It’s been terrific collaborating with you over many years. And in this current series, we are delving into the criminalization. And over the past several years, the criminalization has been very significant policy experimentation in the U.S. and Canadian Northwest. At the city level in San Francisco, California, in Vancouver, British Columbia, and at the whole state level in Oregon and Washington. What has that experimentation been about?

HUMPHREYS: It’s been remarkably broad. It certainly involves drug use, but it’s gone well beyond that. And essentially it starts in 2020 just north of me—I live a little bit south of San Francisco—and running up into British Columbia there was a lot of defunding of policing, generally, and sometimes that was cuts, and that was just holding the budget flat.

There was also a pullback of the role police used to have with regulating public space. So, you know, we share a lot of space with each other. We are usually able to sort that out. But in this era, the public’s view much more was that let’s get the police out of that and just kind of let, let people sort it themselves.

And that included people who were using drugs or people who were dealing drugs. That changed the character of these places all up and down the coast and had a whole range of effects, which we try to go into, as you know, in the paper. But what’s been striking to me is how fast it came in and how fast it went straight back out again. So, it’s been extremely dynamic period in drug and crime policy in the Pacific Northwest.

FELBAB-BROWN: Well, and we’ll talk about the significant changes and fluctuations in policy in greater detail on the show. But let me just reiterate the core point that you made. So, the experimentation was about not imprisoning, not penalizing people for using drugs, but also for dealing drugs in local retail markets. And you mentioned that this was part of a broader pullback of police from enforcing various elements of public safety. Did I get it right?

HUMPHREYS: Yes. Yeah, yeah. That’s correct.

FELBAB-BROWN: And so, how did the opioid fentanyl epidemic feed into this? Did it bring about this decriminalization?

HUMPHREYS: We are dealing, as you said with the worst overdose levels we’ve ever seen in the history of the country. Dwarfs things … I I … when I think early in my career, I thought how bad HIV/AIDS was, that we would never see an epidemic that took that many young lives. And this is this is, in fact, substantially worse than that.

FELBAB-BROWN: It’s worse than the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s?

HUMPHREYS: Absolutely. Yeah. The rate of acute deaths now from from overdoses is at a half again as high as the very worst year of HIV/AIDS. And again, in both cases, young people.

So, that that has understandably caused many people, including myself, you know, sadness, grief, frustration, despair. And in that environment, you know, more radical solutions often are brought forward because they have to be because, you know, we’re we’re clear that things are not working the way they are.

The second thing is that in all of these places there were very extensive harm reduction policies in place. So, things like needle exchange and naloxone distribution. And the promise for years had been that if we do that, the promise from people who advocate those approaches, maybe we’ll have more drug use, but at least we won’t have so much harm. And here we have these places, particularly British Columbia, which have more harm reduction than any places in the world, and overdoses were going up and up and up.

So, that also fueled a sense of desperation. Let’s try something really different, which was to change the law in terms of how the criminal justice system responded or didn’t respond to people were using drugs in private or in public, and to some extent also how we respond to people who were dealing drugs.

FELBAB-BROWN: And some people are suggesting that the reason why we have so much more focus on harm reduction and even going to decriminalization in the way you have been describing is because the fentanyl opioid epidemic has affected as much white people as minorities. What’s your take on that?

HUMPHREYS: Well, race shapes most areas of social policy in the United States, it just does, whether we like it or not. That’s the way it is. I think it’s definitely the case that even before fentanyl, you could see there was a more, globally speaking, compassionate response to people who were addicted to opioids, like when people started getting addicted in large numbers to prescription opioids in the ‘90s and and the 2000s, both the social reactions, but also like, you know, the news coverage was far less look at this malignant person destroying society and it was much more look at this poor suburban mom who had a bad back and is now addicted to OxyContin.

And part of that is clearly about race. Part of it’s clearly about social class. You know, methamphetamine, which was in the ‘90s, was mostly white people, but they were poor people, and who were treated less sympathetically.

So, I think those things are in the soup. But that’s, that’s actually proceeded fentanyl that, that really, I think is something we’ve seen in the last 20 years.

FELBAB-BROWN: And we speak about methamphetamine on the first episode with Professor Reuter and Professor Midgette, and the super potent meth as well in the mix of dealing with opioids and with fentanyl.

Let’s delve into the specifics of the policies in San Francisco, Oregon, Washington, Vancouver. So, broadly speaking in this Pacific Northwest spanning the two countries, there is decriminalization. But were the policy designs the same, were they different?

HUMPHREYS: Yeah, there were some very important differences. Probably the most similar policies were British Columbia and Oregon, both of which instituted—at the provincial level for British Columbia, state level for Oregon—complete decriminalization of use in, in private and critically in, in public as well, which ended up having a significant effect on how these policies were perceived.

What San Francisco did is it’s a city, so it didn’t really change the law, but just in terms of priorities, it went all in essentially on the harm reduction proposed in terms of spending very little on prevention, a small amount of treatment, but not not a lot. And the police basically pulled back pretty substantially. So, there are enormous open-air markets in San Francisco, like in the Tenderloin, where I is a neighborhood where I volunteer, I walk by, you know, scads of fentanyl dealers everywhere I go who operate with with complete impunity by that being the de facto policy.

And at night there’s there’s literally hundreds of dealers out there, as well as an enormous market of stolen goods, which is part of the surround of these drug scenes as people, you know, mass shoplifting, selling goods, buying drugs and so on like that.

FELBAB-BROWN: And they’re stealing goods in order to pay for the fentanyl they crave?

HUMPHREYS: Correct. Yeah, yeah. And me, and it’s something important to mention. Relative to, you know, heroin when I started my career, somebody who might come into the hospital for treatment to heroin might be using once or twice a day, they might even have a job that can have that much stability. But fentanyl is much more fast acting, and people might be using it 4 or 5, 10, you know, 20 times a day. And so, it’s a much more consuming, no pun intended, consuming activity. But also, you have the constant need for more money to buy the next, next hit of drugs. And that that’s fueled a lot, a lot of this sort of property crime we see connected around fentanyl.

What happened in Washington was unusual, which was it was a court decision that the state’s law on drug possession was in conflict with the Constitution. So, sort of an unusual moment where they just did something that no, no place on Earth has done, courts just said there is no consequences at all. And then the legislature’s like, oh, gosh, now we have no drug laws. And they had a very interesting debate over the next three months. And should we just keep it this way or should we, you know, change things?

And they had previously had felonies as, for possession, which is pretty serious. You could get sent to prison for a felony. And they instead converted it to a very low-level misdemeanor with lots of rules that you had to give treatment options multiple times. The police had to prove that they had done that. So, that’s how it came about really differently. Whereas for example, in Oregon it came out through a popular vote, through an initiative. This was driven in Washington by a court case.

These places also differed in how much services they provided. British Columbia, as I mentioned, it already had a lot of harm reduction services, probably as much as anywhere in the country. San Francisco had a lot of services. Oregon really had very poor services, and that’s part of the story. They have the worst access to care, you know, in the U.S., very little of, you know, a little treatment, a little harm reduction, but not that much, which helped account for why their experiment turned out to be an unhappy one, as I think everybody knows at this point.

FELBAB-BROWN: Yeah. I mean, what is coming across in what you’re explaining to us is a theme that has run across several of the episodes, that the Devil and Angel really are in the details of policy design, but also in the context. And exactly the same designs might have very different outcomes if the cultural or social political context, structural context is different. And in this case also how the changes to laws, how the changes to policies came about, such as through ballot or through a court case.

So, you know, before we speak about the problems, please tell us what have been the successes, the accomplishments of the decriminalization policies.

HUMPHREYS: So, you know, when you look at what is, you know, achievements or failures of policy, that’s often in the eye of the beholder. So, the very same outcome might be viewed quite differently. And, you know, a good example of this is so in San Francisco there was a one of the big contractors was funded to create a linkage center, which was sold to the public as this will link people to services like housing, like addiction treatments, like, you know, food banks, and things like that. And the provider just decided on their own initiative that, no, it’s going to be a lounge where people can smoke fentanyl without any penalty. And at the end of that, it turned out that they had linked hardly anybody to addiction treatment at all, but nobody had died from using fentanyl like you’d expect in supervised drug consumption sites.

So, some people would say, well, that was an accomplishment, you know, because they wanted safe consumption sites, and this was clearly one that had succeeded. And other people said, that’s a failure because you were supposed to link people to treatment and you didn’t.

So, all these things are, you know, they’re consequences of policy, but people vary in how they think. And the biggest one, I think is how this sort of arrest environment. So, in places like Oregon, there were dramatic reductions in the number of people who were arrested for using drugs and the number of people who were arrested for dealing drugs. Now, if you have a, you know, a libertarian conception that these are rights that should not be abridged by the state, this is a very good outcome. You know, there was really no better place to use drugs or deal drugs then than than Oregon. On the other hand, of course, some people feel like having those things uncontrolled is bad, so they would view that as a failure. But anyway, that was clearly a consequence as was envisioned in the law. We’re not going to do, that sort of thing.

Property crime and violence went up in Washington and Oregon and San Francisco through this period while dropping in the rest of the country. And I think almost everyone would think that is a bad outcome. You know, people might say we’d like fewer drug arrests, but we don’t like the the violence and and the crime.

In, in terms of some of the mechanics of the policy, there were certainly significant failures just in implementation. So, Oregon had the idea that if you give people a ticket or a fine for up to $100 for say, using fentanyl on a, you know, in a public park, and then but the ticket said, you know, but if you call a, a toll-free hotline, you take a health assessment we’ll waive that fine. And they thought lots of people would then, oh, that they’ll do that and they’ll get in treatment. Well, it turned out over 90 percent of people just threw the ticket away.

And so, that was just clearly like a design failure that did not work. It misunderstood the nature of addiction in thinking that people with such a small incentive would lead people to seek help who had already given up much more profound things in order to use fentanyl.

They had terrible problems, too, just rolling out the money. So, the the measure in Oregon did provide more money for services which were really needed. But rather than work with the addiction, the existing treatment system, the designers essentially tried to set up a new system. This is sort of reflecting the distrust of traditional treatment that was common in this era. And with new people, new faces, and all that reallocated, well, you know, you know, 16 months after it was passed, they hadn’t given out a dollar yet. And so, that was clearly an implementation failure.

The last thing is that one of the key promises was that overdoses would drop. And all of this whole region is experiencing record overdoses that they’ve never seen before. San Francisco, Oregon, Washington, British Columbia. Now, it’s certainly true that part of this has to do with the spread of fentanyl to the West. You know, there, you know, you know, Central California has, you know, their overdose deaths are up by 5%. But but not the sort of 40% increases we saw in places like Oregon and Washington, not the historic levels that you see in British Columbia, which has had fentanyl for a very long time.

So, there’s certainly other factors could matter. It’s also a pandemic obviously, and another thing that would have mattered. It was really hard to sustain in the face of such. Incredible increase in overdoses that these policies were reducing overdose. And in fact, it’s interesting a lot of the advocates just shifted to arguing, well, maybe it hasn’t made things worse, but people didn’t vote for these policies on the theory that maybe they won’t make things worse. They really voted for them in the idea that they would save lives, which they did not do.

FELBAB-BROWN: And that’s even before xylazine has spread to the West. Xylazine, of course, is complicating the most important element of harm reduction right now, which is access to naloxone and the reversal of lethal overdose. And we haven’t seen xylazine yet spread beyond the East Coast and hit the West, hit the Pacific region.

Now, there is another example of decriminalization, and that’s Portugal. About a decade and a half ago, Portugal became the pioneer of decriminalization policies. And the country that implemented harm reduction approaches on a nationwide level. And for several years, Portugal registered significant successes. And many of the jurisdictions that you were speaking about would say that they learned from Portugal. Did they in fact learn? And why were the outcomes in Portugal better than in Oregon, Washington, and San Francisco?

HUMPHREYS: So, you’re right. Portugal is cited as, has been cited for years now in American drug policy, as you know, the example, which is interesting because it’s—I love Portugal, wonderful country—but you never hear it mentioned in any other policy sphere other than this one in the U.S. Portugal, when they removed decriminalization, first off, they never really had much criminalization to begin with. So, it was not a huge shift on the policing side, but it was a huge shift on a health side. So, they had quite extensive services for people—addiction treatment, HIV care, harm reduction services. And let’s not forget that Portugal guarantees the right to health care for all citizens and the United States does not. So, that that is a big difference.

Second thing is Portugal has a different type of drug problem than us. You know, when you see synthetics like nitazenes and fentanyls are now appearing in a couple of European, you know, sites, nothing like what you see in the U.S. and Canada though. So, that was different.

FELBAB-BROWN: So, drugs with much less risk of immediate lethal overdose.

HUMPHREYS: Yeah. So, the modal, you know, opioid users coming into contact with, you know, authorities in Portugal is going to be using, you know, heroin or perhaps a diverted prescription opioid, not a fentanyl or a nitazene, for now at least, I mean maybe the future could be different.

Third thing is the Portuguese had a mechanism which was explicitly rejected by the advocates in the U.S., which is that dissuasion commissions. So, if you are out on the streets using drugs, the police in Portugal can arrest you and say you have to go to a dissuasion commission, which is not a punitive process, but it is a certainly a pretty strong nudge process where you get an assessment from people who are expert in this area and they could say, you know, well, this time we’re going to let it go. We don’t think you have a bad problem. But they can also say, we really think you need to go to treatment. And by the way, you’re a cab driver and we’re not going to let you keep driving your cab until you do.

And it’s it’s a compassionate process, but it is definitely also a pushing process, you know, pushing people towards changing their behavior. And particularly, it was much more libertarian flavored movement in the U.S. and their view was, you know, any kind of pushing is wrong. So that’s, you know, they took it, they took that out. And that may have been a mistake.

FELBAB-BROWN: I just to a little bit elaborate on the pushing element in the Portuguese case. So, people who would be arrested for drug use on the street would be sent to the commission. First of all, what would happen if the person did not show up at the commission? And second, I just want to hit what you are saying, namely that, although people would not be sent to prison, presumably, they could face other penalties like losing public licenses, such as to operate a taxi.

HUMPHREYS: Yeah. That’s right. Yeah, you don’t have any choice but to show up to the commission. It doesn’t mean that anything bad will happen to you if you do. That in fact, the majority of cases, they say, well, you know, you were caught using these drugs. We don’t think you have a problem. You should go and sin no more kind of thing. But you you would can endure a punishment for not showing up. They try very hard not to use carceral penalties. But as you say, they do have these other powers like to fine or place restrictions on people where they can go or what they can do.

So, it is not a free for all, which is a lot of people imagine Portugal is. And it’s interesting when my colleagues who helped design that system have seen cities like San Francisco and Vancouver and Portland, they have been shocked and disgusted at the open drug scene and our tolerance of it. That is not what Lisbon looks like.

And, you know, and that that has been sort of sold to out here, yeah, that’s in Portugal it’s that way. And everyone’s just really comfortable with it. It’s like, no, that’s, that’s absolutely not the way it is. They would intervene in that situation both with the state but also through social networks, which is the other point that’s important to mention is this Portugal has a very different culture than the western coast in North America. It is a country that was a dictatorship in living memory. It is heavily Catholic inflected in its values. It is communitarian. Families are strong. People live in multi-generational neighborhoods where their family has been around for decades. And there’s a lot of love and connection that comes with that. There’s absolutely also some constraint that comes with that.

And this is the opposite of what you see out here. People come to San Francisco or come to the West or come to Portland to get away from all that. There’s plenty of people, like, I didn’t want to live in a small town in Iowa where everyone’s watching what I’m doing. I wanted to be me. I wanted to be a punk musician, I wanted to be an entrepreneur, or, you know, I wanted to express myself.

And so, that’s the culture of the West, which in many ways is magnificent. I mean, that’s why we have Silicon Valley, and we have such arts and music, and we have, you know, gay and lesbian rights, and all those, really things to be cherished.

But it doesn’t work the same way for drugs. When you sort of, you know, and we do have a very powerful drug culture. San Francisco, for example, is one of the heaviest drinking cities in the country. It is the heart of cannabis culture, psychedelic culture. Oregon has a lot of this, too. Seattle as well. Because people aren’t necessarily pursuing their individual good and living their own way, that’s the nature of addiction is people’s ability to make those decisions is not as good. People lose control and people start experiencing harm. And therefore, that ethic of kind of be who you are doesn’t have the same consequences.

And, you know, when you take the law away, which all these places did, the only thing left in societies is the culture. In Portugal, that culture happens to be kind of strong, constraining, and out in the West it isn’t. So, there was really the law was only thing between, you know, left. And when that left, we got what we got, which was an awful lot of drug use and an awful lot of consequences for individuals and for the neighborhoods they lived in.

FELBAB-BROWN: Yeah, and on the episode with Professor Jonathan Caulkins, we were talking about the balance between individual rights and community interests and the complexities and how different times, different societies, different cultures make those judgments. And similarly, on the episode with Professor Harold Pollack and Professor Nicole Gastala, we heard about the important role of communities in helping to reduce demand and encouraging people to access treatment, and the absence of communities having significant effects on the policy effectiveness, a theme that will also come up in our conversation with Philomena Kebec on Native American communities and fentanyl.

So, you know, we talked about some of the accomplishments, we talked about the challenges in the northwest. And you have already mentioned that publics in Oregon, in Washington, in San Francisco soured on many of these policies. When that happened, how have policies changed as well?

HUMPHREYS: We have to put ourselves in the mindset of where people were, you know, when all of this started. So, George Floyd was murdered by police officers, the whole world was appalled, appropriately appalled. And people in the Northwest were particularly so. Some of the most largest, most passionate, and most enduring protests were in that region. So, a huge number of people were sympathetic to the idea of, you know, pulling back on policing of all sorts. Said that would create a better and more just society.

Unfortunately, though, that reality, you know, a year later, two years later, was that they saw there was some cost to that. And this was going to be more, more complicated in, in terms of things like the quality of neighborhoods. And that’s something it’s a very hard thing to quantitatively assess. But I just say as someone who spends a lot of time in San Francisco, I go up to Oregon a lot—we have a lot of research partners up there—I’ve been to Washington, I’ve been to British Columbia, just what it’s like to walk down a street really changed dramatically. You have to remember also there was a pandemic on.

But you think, like, what is it like to be, let’s say, a woman in San Francisco who’s walking to her law firm with a huge number of workers, and there’s three or four men who are using drugs on the side of the sidewalk, and there’s a police officer standing around somewhere. That may just be disturbing, but you don’t feel fearful. Then you have that same situation again where the pandemic has cleared things out. That woman is walking alone. Those three men are there and there’s no policeman anywhere in sight. And you’re kind of in a Wild West situation. Now, there’s no more people using drugs on the streets as before, but something that previously felt sad but not frightening starts to feel frightening.

And as other consequences of things are just like, you know, retail theft, housebreaking, vandalism, sort of neighborhoods decaying, get worse and worse. And again, at the time people have said, we don’t want police to do stuff. You know, when when your car’s broken into the tenth time, when, you know, someone has been assaulted, when, when these problems start to spread to bigger and bigger regions, where you see pictures on TV of children having to be literally shepherd by their parents past sometimes, you know, just blocks of people unconscious from drugs, dealing drugs, then the reality sets in. Is, okay, we don’t want to go back to a racist, carceral war on drugs. And also, we’re not satisfied with what’s happening. And we were promised a lot of things that aren’t happening. You know, it’s not easier to get treatment. Deaths are not going down. They’re going up. And our neighborhoods are really decaying.

And so, something that happens that seems sometimes you don’t … you wonder if this ever happens in politics and it did here, is a lot of people change their minds. A lot of people were willing at one moment to try something radically different and see what happened. They got the results of their experiment and they shifted. One of the interesting things about that, by the way, is some of the biggest shifts were among people of color. A lot of this was argued in terms of racial justice. But if you look at the polling against Measure 110, the most hostile people wanted to overturn the most were African Americans.

FELBAB-BROWN: And the please explain to us what is Measure 110?

HUMPHREYS: That was Oregon’s … that was the ballot initiative that Oregon passed to decriminalize all these things, which which, by the way, passed easily at first. It was it was popular. I think it got like 58% of the vote. But, you know, two-and-a-half years later in polling, two-thirds of people said they wanted it repealed in part or in whole. And if you asked people who were Black or people who were Latino, it was three-fourths or even four out of five people were saying that.

And and so, that created a shift that was reflected in politics. In, in San Francisco and in Portland, very sort of defund the police, let’s just accept drugs district attorneys were chucked out of office and replaced by people who promised a much more law-and-order kind of approach. Seattle, you know, you know, I think Joe Biden won Seattle in the 2020 election by something like 50 points. Two years later elected a law-and-order district attorney, who pledge to crack down around drugs and around crime. Vancouver had a complete flipover in their mayoral election. The British Columbian premier, you know, backed off on decriminalization and said in response to the public aspect, said it would no longer be allowing that in public.

FELBAB-BROWN: I want to home in a little on British Columbia and Vancouver, because, you know, other than Portugal, it is often the hallmark, the kind of measure the, the yardstick against which to measure the decriminalization, harm reduction. What are the current policies in Vancouver and British Columbia after the political electoral changes and the the reversal in public acceptance of these policies?

HUMPHREYS: British Columbia has a well-developed network of services that are believed to reduce harms anywhere else. By which I mean, you know, certainly needle exchanges, certainly naloxone, also supervised drug consumption facilities, an enormous number of those, a general sort of tolerance of, of use, and strikingly, what they call safe supply. So, they actually are giving out addictive drugs for unsupervised community use, drugs like hydromorphone, in the hopes that that will reduce addiction. That’s by the way quite for further than Portugal ever went.

FELBAB-BROWN: We learned about this in Jonathan Caulkins’ papers. He gets into the pros and cons and promises and challenges of official supply.

HUMPHREYS: Yes, yes. And we’ll see, you know, we’ll see whether or not that, you know, survives or not. You know, I really don’t I don’t know the answer to that.

But it what it was clear that decriminalization was not politically sustainable in public. When enough people, like, they can’t take their kid to the park anymore because there’s too many needles or it’s just they don’t feel safe because there’s a lot of people are intoxicated, a lot of people are dealing drugs, those communities pushed back. Advocates sued them successfully and said, you cannot restrict the public use of drugs. And, that was even though they won the case, then the premier said, you know, could tell this was a a political nightmare for his party. And so, he himself said, let’s, let’s not do this anymore.

And interestingly, you know, Ontario had applied to copy the same thing, and the national government said no. So, that that seems to reflect a, a change as well. I don’t think, you know, they will go back to I shouldn’t say go back, I don’t think they’re going to adopt a super punitive criminal justice policy because, you know, they never really had one. You know, neither neither by the way did did did Oregon, you know, for for that point.

But they I do think they want to reclaim public space. I think that’s what a lot of this is about. And I don’t think it’s unreasonable for people to want to have some access to public space. I mean, I, I have spent 35 years telling people that people who use drugs matter. When I go to San Francisco or Portland, I usually have to say people who don’t use drugs matter. And there’s nothing wrong with people wanting, you know, like an elderly couple wanting to be able to walk down the street in the early evening and not have to encounter people using drugs, anyone with a gun stuck in their belt, or that type of thing. That’s just something I get. As you know, I’m a middle-class person. Where I live, that should be the right of everybody and should be sustainable. And that’s why I don’t think the public, the public aspects of this around dealing and use are … just are not sustainable.

FELBAB-BROWN: Well certainly reclaiming public spaces, having access to public spaces is so fundamental to the quality of well-being, social organization, economic life—

HUMPHREYS: —and connection. Yeah.

FELBAB-BROWN: Absolutely. Political life and personal life. So, you know, this all then brings us to, in conclusion, to get your reflections on what is the way forward. How do we avoid the trap of the pendulum swinging from highly racist policies that criminalize users and put them in prison for a long time, which we know is deeply ineffective, deeply counterproductive, and embrace what much more empathy-oriented approaches bring, including saving lives and yet avoid the failures and challenges and problems that we have in the Pacific Northwest?

HUMPHREYS: Yeah. So, the way a lot of people think about policy in general is, is an on/off switch. You know, we can only do we have two choices, and often advocates frame things that way to sort of push a radical solution here. You can only have carceral, awful racist war on drugs or a free for all, when the truth is there’s, you know, these are all dials and, you know, we can turn them at different levels.

It’s interesting that these places like San Francisco, Oregon, like British Columbia, like Washington already had their dial turned pretty low on criminal justice, you know, policies. These are by far, you know, the probably the least punitive states. And what they showed is when you turn it down to zero, you get some qualitatively different effects that you may not have expected.

But there’s a lot of the United States that where those dials are turned up pretty high, where they could probably turn them down to where the Pacific Northwest normally functions and be better off. If you went to Mississippi or Alabama, you would still find people being thrown into, you know, a cell for the use of a drug going through withdrawal horribly, perhaps dying from that, or if not getting out without tolerance and then taking their their normal dose of drugs and dying of an overdose, not having the option of treatment, all those sorts of things.

So, I think that’s where the great reform opportunities are for the states, is the places to learn what, you know, what you can do with modest but not completely absent role for law enforcement.

I think another thing we can observe is having services available matters. And this, by the way, you know one of the sad things about Portugal is that the great success, you know, for a number of years, but things are not going as well now. I mean, I think overdoses are up nine years in a row since the financial crisis. They’ve had a great retrenchment of services.

But I think a lesson is that, you know, the decrim not ends up, you know, not in itself, you know, doing much if you don’t have places for people to go where they can get adequate health care. And so, one thing I’m glad about the bill that replaced Measure 110, and this is a synergy between the people who supported it and the people who repealed it, is it does put a lot of money in into the treatment system, recognizing, you know, that these are, you know, fentanyl addiction is really tough and it’s really, really disabling, disturbing, and obviously potentially deadly condition. So, that seems to me to be, you know, something to take away from, from these experiences.

FELBAB-BROWN: And we delve in great detail into treatment in the episode with Professor Harold Pollack and Professor Nicole Gastala. And, you know, the key takeaways for me from our conversation today is that policy should not be thought of as a pendulum, operating only on the extreme sides or, as you phrased it, an on and off switch, with opportunities to fine tune policies existing across the country, in fact, around the world.

And one of the important opportunities that have come out of the Northwest experiment is learning from experimentation. If we don’t allow local experimentation, we don’t allow local policy innovation, we’ll be just perpetually stuck only in one policy.

So, Professor Humphreys, thank you so much for joining me on the show today. Thank you very much for your tremendous contribution in your paper to the project, and the enormous work that you are doing to help people with drug use and their communities and families.

HUMPHREYS: Thank you so much.

FELBAB-BROWN: The Killing Drugs is a production of the Brookings Podcast Network. Many thanks to all my guests for sharing their time and expertise on this podcast and in this project.

Also, thanks to the team at Brookings who makes this podcast possible, including Kuwilileni Hauwanga, supervising producer; Fred Dews, producer; Gastón Reboredo, audio engineer; Daniel Morales, video editor; and Diana Paz Garcia, senior research assistant in the Strobe Talbott Center for Security, Strategy, and Technology; Natalie Britton, director of operations for the Talbott Center; and the promotions teams in the Office of Communications and the Foreign Policy program at Brookings. Katie Merris designed the compelling logo.

You can find episodes of The Killing Drugs wherever you like to get your podcasts and learn more about the show on our website at Brookings dot edu slash Killing Drugs.

I am Vanda Felbab-Brown. Thank you for listening.

Foreign Policy

Strobe Talbott Center for Security, Strategy, and Technology

Election ’24: Issues at Stake Initiative on Nonstate Armed Actors

Beau Kilmer, Roland Neil, Vanda Felbab-Brown

September 10, 2024

David R. Holtgrave, Regina LaBelle, Vanda Felbab-Brown

September 3, 2024

Nicole Gastala, Harold Pollack, Vanda Felbab-Brown

August 27, 2024

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

To fight the opioid crisis, Canada tests decriminalizing possession

Addicts inject themselves in May 2011 at the Insite supervised injection center in Vancouver, Canada. Laurent Vu The/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

Addicts inject themselves in May 2011 at the Insite supervised injection center in Vancouver, Canada.

In a policy shift aimed at reducing deaths from overdoses, Canada is decriminalizing the possession of small amounts of drugs in the western province of British Columbia.

Drug overdose deaths have risen sharply across Canada over the past five years, with opioid-related deaths linked to fentanyl more than doubling.

British Columbia has been the hardest-hit province— it declared fentanyl a public health crisis six years ago — and provincial officials asked for federal permission to decriminalize the possession of small amounts of opioids, cocaine and methamphetamines.

The experimental policy, which takes effect in January 2023, will last three years.

British Columbia's minister of mental health and addictions, Sheila Malcolmson, says the move will put the focus on health care.

"By decriminalizing people who use drugs, we will break down the stigma that stops people from accessing life-saving support and services," she said in a statement.

New York City allows the nation's 1st supervised consumption sites for illegal drugs

In recent years Canada has introduced a number of health care-focused programs for addressing its overdose epidemic, including setting up supervised injection sites, providing tests to check drugs for fentanyl and making heroin available by prescription for those who haven't found success with other treatments.

But overdose deaths spiked at the start of the pandemic and remained high through 2021, according to the latest data available.

The policy change in British Columbia will apply to individuals 18 and older who are in possession of 2.5 grams or less of illicit drugs.

"We are granting this exemption because our government is committed to using all available tools that reduce stigma, substance use harms, and continuing to work with jurisdictions, to save lives and end this crisis," said Carolyn Bennett, Canada's federal minister of mental health and addictions.

The War On Drugs: 50 Years Later

Oregon's pioneering drug decriminalization experiment is now facing the hard test.

In the U.S., voters in the state of Oregon approved a similar policy in 2020, decriminalizing personal use quantities of most illicit drugs under state law. That change was made without approval from the federal government.

- British Columbia

- opioid overdoses

- decriminalization

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.10(9); 2020

Original research

Impact evaluations of drug decriminalisation and legal regulation on drug use, health and social harms: a systematic review, ayden i scheim.

1 Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Dornsife School of Public Health, Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA

2 Centre on Drug Policy Evaluation, St Michael's Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Nazlee Maghsoudi

3 Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Zack Marshall

4 Social Work, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Siobhan Churchill

5 Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada

Carolyn Ziegler

6 Library Services, Unity Health Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

7 Medicine, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, California, USA

Associated Data

bmjopen-2019-035148supp001.pdf

bmjopen-2019-035148supp002.pdf

bmjopen-2019-035148supp003.pdf

To review the metrics and findings of studies evaluating effects of drug decriminalisation or legal regulation on drug availability, use or related health and social harms globally.

Systematic review with narrative synthesis.

Data sources

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science and six additional databases for publications from 1 January 1970 through 4 October 2018.

Inclusion criteria

Peer-reviewed articles or published abstracts in any language with quantitative data on drug availability, use or related health and social harms collected before and after implementation of de jure drug decriminalisation or legal regulation.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two independent reviewers screened titles, abstracts and articles for inclusion. Extraction and quality appraisal (modified Downs and Black checklist) were performed by one reviewer and checked by a second, with discrepancies resolved by a third. We coded study-level outcome measures into metric groupings and categorised the estimated direction of association between the legal change and outcomes of interest.

We screened 4860 titles and 221 full-texts and included 114 articles. Most (n=104, 91.2%) were from the USA, evaluated cannabis reform (n=109, 95.6%) and focussed on legal regulation (n=96, 84.2%). 224 study outcome measures were categorised into 32 metrics, most commonly prevalence (39.5% of studies), frequency (14.0%) or perceived harmfulness (10.5%) of use of the decriminalised or regulated drug; or use of tobacco, alcohol or other drugs (12.3%). Across all substance use metrics, legal reform was most often not associated with changes in use.

Conclusions

Studies evaluating drug decriminalisation and legal regulation are concentrated in the USA and on cannabis legalisation. Despite the range of outcomes potentially impacted by drug law reform, extant research is narrowly focussed, with a particular emphasis on the prevalence of use. Metrics in drug law reform evaluations require improved alignment with relevant health and social outcomes.

Strengths and limitations of this study

- This is the first study to review all literature on the health and social impacts of decriminalisation or legal regulation of drugs.

- We systematically searched 10 databases over a 38-year period, without language restrictions.

- The review was limited to study designs appropriate for evaluating interventions, nevertheless, most included studies used relatively weak evaluation designs.

- Included outcomes were heterogeneous and not quantitatively synthesised.

- Heterogeneity in the details and implementation of decriminalisation or legal regulation policies was not considered in this review.

Introduction

An estimated 271 million people used an internationally scheduled (‘illicit’) drug in 2017, corresponding to 5.5% of the global population aged 15 to 64. 1 Despite decades of investment, policies aimed at reducing supply and demand have demonstrated limited effectiveness. 2 3 Moreover, prohibitive and punitive drug policies have had counterproductive effects by contributing to HIV and hepatitis C transmission, 4 5 fatal overdose, 6 mass incarceration and other human rights violations 7 8 and drug market violence. 9 As a result, there have been growing calls for drug law reform 10–12 and in 2019, the United Nations Chief Executives Board endorsed decriminalisation of drug use and possession. 13 Against this backdrop, as of 2017 approximately 23 countries had implemented de jure decriminalisation or legal regulation of one or more previously illegal drugs. 14–16

A wide range of health and social outcomes are affected by psychoactive drug production, sales and use, and thus are potentially impacted by drug law reform. Nutt and colleagues have categorised these as physical harms (eg, drug-related morbidity and mortality to users, injury to non-users), psychological harms (eg, dependence) and social harms (eg, loss of tangibles, environmental damage). 17 18 Concomitantly, a diverse and sometimes competing set of goals motivate drug policy development, including ameliorating the poor health and social marginalisation experienced by people who use drugs problematically, shifting patterns of use to less harmful products or modes of administration, curtailing illegal markets and drug-related crime and reducing the economic burden of drug-related harms. 19

Given ongoing interest by states in drug law reform, as well as the recent position statement by the United Nations Chief Executives Board endorsing drug decriminalisation, 13 a comprehensive understanding of their impacts to date is required. However, the scientific literature has not been well-characterised, and thus the state of the evidence related to these heterogeneous policy targets remains largely unclear. Systematic reviews, including two meta-analyses, are narrowly focussed on adolescent cannabis use. Dirisu et al found no conclusive evidence that cannabis legalisation for medical or recreational purposes increases cannabis use by young people. 20 In the two meta-analyses, Sarvet et al found that the implementation of medical cannabis policies in the USA did not lead to increases in the prevalence of past-month cannabis use among adolescents 21 and Melchior et al found a small increase in use following recreational legalisation that was reported only among lower-quality studies. 22

Given increasing interest in quantifying the impact of drug law reform, as well as a lack of systematic assessment of outcomes beyond adolescent cannabis use to date, we conducted a systematic review of original peer-reviewed research evaluating the impacts of (a) legal regulation and (b) drug decriminalisation on drug availability, use or related health and social harms. Our primary aim is to characterise studies with respect to metrics and indicators used. The secondary aim is to summarise the findings and methodological quality of studies to date.

Consistent with our aim of synthesising evidence on the impacts of decriminalisation and legal regulation across the spectrum of potential health and social effects, we conducted a systematic review using narrative synthesis 23 without meta-analysis. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed in preparing this manuscript. 24 The review protocol was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42017079681) and can be found online at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=79681 .

Search strategy and selection criteria

The review team developed, piloted and refined the search strategy in consultation with a research librarian and content experts. We searched MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, Web of Science, Criminal Justice Abstracts, Applied Social Sciences Index & Abstracts, International Bibliography of the Social Sciences, PAIS Index, Policy File Index and Sociological Abstracts for publications from 1 January 1970 through 4 October 2018. We used MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms and keywords related to (a) scheduled psychoactive drugs, (b) legal regulation or decriminalisation policies and (c) quantitative study designs. Search terms specific to health and social outcomes were not employed so that the search would capture the broad range of outcomes of interest. See online supplemental appendix A for the final MEDLINE search strategy. For conference abstracts, we contacted authors for additional information on study methods and to identify subsequent relevant publications.

Supplementary data

We included peer-reviewed journal articles or conference abstracts reporting on original quantitative studies that collected data both before and after the implementation of drug decriminalisation or legal regulation. We did not consider as original research studies that reproduced secondary data without conducting original statistical analyses of the data. We defined decriminalisation as the removal of criminal penalties for drug use and/or possession (allowing for civil or administrative sanctions) and legal regulation as the development of a legal regulatory framework for the use, production and sale of formerly illegal psychoactive drugs. Studies were excluded if they evaluated de facto (eg, changes in enforcement practices) rather than de jure decriminalisation or legal regulation (changes to the law). This exclusion applied to studies analysing changes in outcomes following the US Justice Department 2009 memo deprioritising prosecution of cannabis-related offences legal under state medical cannabis laws. Eligible studies included outcome measures pertaining to drug availability, use or related health and social harms. We used the schema developed by Nutt and colleagues to conceptualise health and social harms, including those to users (physical, psychological and social) and to others (injury or social harm). 18

Both observational studies and randomised controlled trials were eligible in principle, but no trials were identified. There were no geographical or language restrictions; titles, abstracts and full-texts were translated on an as-needed basis for screening and data extraction. We excluded cross-sectional studies (unless they were repeated) and studies lacking pre-implementation and post-implementation data collection because such designs are inappropriate for evaluating intervention effects.

Data analysis

Screening and data extraction were conducted in DistillerSR (Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Ontario). We began with title-only screening to identify potentially relevant titles. Two reviewers screened each title. Unless both reviewers independently decided a title should be excluded, it was advanced to the next stage. Next, two reviewers independently screened each potentially eligible abstract. Inter-rater reliability was good (weighted Kappa at the question level=0.75). At this stage, we retrieved full-text copies of all remaining references, which were screened independently by two reviewers. Disagreements on inclusion were resolved through discussion with the first author. Finally, one reviewer extracted data from each included publication using a standardised, pre-piloted form and performed quality appraisal. A second reviewer double-checked data extraction and quality appraisal for every publication, and the first author resolved any discrepancies.

The data extraction form included information on study characteristics (author, title, year, geographical location), type of legal change studied and drug(s) impacted, details and timing of the legal change (eg, medical vs recreational cannabis regulation), study design, sampling approach, sample characteristics (size, age range, proportion female) and quantitative estimates of association. We coded each study-level outcome measure into one metric grouping, using 24 pre-specified categories and a free-text field (see figure 1 for full list). Examples of metrics include: prevalence of use of the decriminalised or regulated drug, overdose or poisoning and non-drug crime.

Metrics examined by included studies. excl., excluding.

We also categorised the estimated direction of association of the legal change on outcome measure(s) of interest (beneficial, harmful, mixed or null). These associations were coded at the outcome (not study) level and classified as beneficial if a statistically significant increase in a positive outcome (eg, educational attainment) or decrease in a negative outcome (eg, substance use disorder) was attributed to implementation of decriminalisation or legal regulation, and vice versa for harmful associations. The association was categorised as mixed if associations were both harmful and beneficial across participant subgroups, exposure definitions (eg, loosely vs tightly regulated medical cannabis access) or timeframes. Although any use of cannabis and other psychoactive drugs need not be problematic at the individual level, we categorised drug use as a negative outcome given that population-level increases in use may correspond to increases in negative consequences; we thought that this cautious approach to categorisation was appropriate given that such increases are generally conceptualised as negative within the scientific literature. For outcomes that are not unambiguously negative or positive, the coding approach was predetermined taking a societal perspective. For example, increased healthcare utilisation (eg, hospital visits due to cannabis use) was coded as negative because of the increased burden placed on healthcare systems. The association was categorised as null if no statistically significant changes following implementation of drug decriminalisation or legal regulation were detected. We set statistical significance at a= 0.05, including in cases where authors used more liberal criteria.

Quality assessment at the study level was conducted for each full-length article using a modified version of the Downs and Black checklist 25 for observational studies ( online supplemental appendix B ), which assesses internal validity (bias), external validity and reporting. Each study could receive up to 18 points, with higher scores indicating more methodologically rigorous studies. Conference abstracts were not subjected to quality assessment due to limited methodological details.

Patient and public involvement

This systematic review of existing studies did not include patient or public involvement.

Study characteristics

As shown in the PRISMA flow diagram ( figure 2 ), we screened 4860 titles and abstracts and 213 full-texts, with 114 articles meeting inclusion criteria ( online supplemental appendix C ). Key reasons for exclusion at the full-text screening stage were that the article did not report on original quantitative research (n=59) or did not evaluate decriminalisation or legal regulation as defined herein (n=23). Details of each included study are presented in online supplemental table 1 . Included studies had final publication dates from 1976 to 2019; 44.7% (n=51) were first published in 2017 to 2018, 43.9% (n=50) were published in 2014 to 2016 and 11.4% (n=13) were published before 2014.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram.

Characteristics of included studies are described in table 1 , both overall and stratified by whether they evaluated decriminalisation (n=19) or legalisation (n=96) policies (one study evaluated both policies). Most studies (n=104, 91.2%) were from the USA and examined impacts of liberalising cannabis laws (n=109, 95.6%). Countries represented in non-US studies included Australia, Belgium, China, Czech Republic, Mexico and Portugal. The most common study designs were repeated cross-sectional (n=74, 64.9%) or controlled before-and-after (n=26, 22.8%) studies and the majority of studies (n=87, 76.3%) used population-based sampling methods. Figure 3 illustrates the geographical distribution of studies among countries where national or subnational governments had decriminalised or legally regulated one or more drugs by 2017.

Characteristics of studies evaluating drug decriminalisation or legal regulation, 1970 to 2018

| Characteristic | Total (%) N (%) (n=114) | Decriminalisation* N (%) (n=19) | Legal regulation* N (%) (n=96) |

| Country | |||

| USA | 104 (91.2) | 10 (52.6) | 95 (99.0) |

| Australia | 3 (2.6) | 3 (15.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Portugal | 2 (1.8) | 2 (10.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| China | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Czech Republic | 1 (0.9) | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Mexico | 1 (0.9) | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Multi-country† | 2 (1.8) | 2 (10.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Focus of drug law reform | |||

| Cannabis | 109 (95.6) | 15 (78.9) | 95 (99.0) |

| Opium | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Peyote | 1 (0.9) | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Multiple/all drugs | 3 (2.6) | 3 (15.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Study design | |||

| Cohort | 4 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.2) |