- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

SIR GAWAIN AND THE GREEN KNIGHT

adapted by Michael Morpurgo & illustrated by Michael Foreman ‧ RELEASE DATE: Oct. 1, 2004

Morpurgo offers a fluid translation of the 14th-century tale. “Chickens, the lot of you. Worse than chickens too,” the anything-but-jolly green giant taunts King Arthur’s court, before losing his head to Sir Gawain—then riding away with it cradled in his arm. A year and a day later, after surviving exhausting hardships, hard battles, and a comically discomfiting attempted seduction, Gawain presents himself, as he had promised, to be beheaded in turn. He looks a trifle undersized in Foreman’s luminous watercolors, which makes his heroism all the more striking as he confronts challenges to his endurance, his knightly prowess, and his stubbornly held honor. In the end, those qualities earn him a new lease on life, though he discovers himself, as Morpurgo writes, “not as honest or true as he would want himself to have been: much like many of us, I think.” Several condensed versions of the story are available for young readers, but enhanced by striking art, plus handsome packaging that includes a text in (perfectly legible) green, this full rendition stands apart. (Folktale. 10-13)

Pub Date: Oct. 1, 2004

ISBN: 0-7636-2519-1

Page Count: 112

Publisher: Candlewick

Review Posted Online: May 19, 2010

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Oct. 15, 2004

CHILDREN'S GENERAL CHILDREN'S

Share your opinion of this book

More by Michael Morpurgo

BOOK REVIEW

by Michael Morpurgo ; illustrated by Tom Clohosy Cole

by Michael Morpurgo ; illustrated by Benji Davies

by Michael Morpurgo ; illustrated by Olivia Lomenech Gill

A YEAR DOWN YONDER

From the grandma dowdel series , vol. 2.

by Richard Peck ‧ RELEASE DATE: Oct. 1, 2000

Year-round fun.

Set in 1937 during the so-called “Roosevelt recession,” tight times compel Mary Alice, a Chicago girl, to move in with her grandmother, who lives in a tiny Illinois town so behind the times that it doesn’t “even have a picture show.”

This winning sequel takes place several years after A Long Way From Chicago (1998) leaves off, once again introducing the reader to Mary Alice, now 15, and her Grandma Dowdel, an indomitable, idiosyncratic woman who despite her hard-as-nails exterior is able to see her granddaughter with “eyes in the back of her heart.” Peck’s slice-of-life novel doesn’t have much in the way of a sustained plot; it could almost be a series of short stories strung together, but the narrative never flags, and the book, populated with distinctive, soulful characters who run the gamut from crazy to conventional, holds the reader’s interest throughout. And the vignettes, some involving a persnickety Grandma acting nasty while accomplishing a kindness, others in which she deflates an overblown ego or deals with a petty rivalry, are original and wildly funny. The arena may be a small hick town, but the battle for domination over that tiny turf is fierce, and Grandma Dowdel is a canny player for whom losing isn’t an option. The first-person narration is infused with rich, colorful language—“She was skinnier than a toothpick with termites”—and Mary Alice’s shrewd, prickly observations: “Anybody who thinks small towns are friendlier than big cities lives in a big city.”

Pub Date: Oct. 1, 2000

ISBN: 978-0-8037-2518-8

Page Count: 144

Publisher: Dial Books

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Sept. 15, 2000

More In The Series

by Richard Peck

More by Richard Peck

by Richard Peck ; illustrated by Kelly Murphy

by Richard Peck illustrated by Kelly Murphy

A WEEK IN THE WOODS

by Andrew Clements ‧ RELEASE DATE: Sept. 1, 2002

Playing on his customary theme that children have more on the ball than adults give them credit for, Clements ( Big Al and Shrimpy , p. 951, etc.) pairs a smart, unhappy, rich kid and a small-town teacher too quick to judge on appearances. Knowing that he’ll only be finishing up the term at the local public school near his new country home before hieing off to an exclusive academy, Mark makes no special effort to fit in, just sitting in class and staring moodily out the window. This rubs veteran science teacher Bill Maxwell the wrong way, big time, so that even after Mark realizes that he’s being a snot and tries to make amends, all he gets from Mr. Maxwell is the cold shoulder. Matters come to a head during a long-anticipated class camping trip; after Maxwell catches Mark with a forbidden knife (a camp mate’s, as it turns out) and lowers the boom, Mark storms off into the woods. Unaware that Mark is a well-prepared, enthusiastic (if inexperienced) hiker, Maxwell follows carelessly, sure that the “slacker” will be waiting for rescue around the next bend—and breaks his ankle running down a slope. Reconciliation ensues once he hobbles painfully into Mark’s neatly organized camp, and the two make their way back together. This might have some appeal to fans of Gary Paulsen’s or Will Hobbs’s more catastrophic survival tales, but because Clements pauses to explain—at length—everyone’s history, motives, feelings, and mindset, it reads more like a scenario (albeit an empowering one, at least for children) than a story. Worthy—but just as Maxwell underestimates his new student, so too does Clement underestimate his readers’ ability to figure out for themselves what’s going on in each character’s life and head. (Fiction. 10-12)

Pub Date: Sept. 1, 2002

ISBN: 0-689-82596-X

Page Count: 208

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Aug. 1, 2002

More by Andrew Clements

by Andrew Clements

by Andrew Clements & illustrated by Mark Elliott

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

| Synopsis | When Sir Gawain, of the Knight of the Roundtable, is challenged by a strange supernatural being called the Green Knight, he must honor the challenge and ride off to meet the being on his terms. |

| Author | Unknown |

| Publisher | Random House Publishing Group |

| Genre | Medieval Fantasy / Epic Poetry |

| Length | 224 Pages |

| Release Date | Tolkien's Translation: December 28th, 1979 |

With the recent release of the trailer for David Lowry’s adaptation of The Green Knight , I’ve been itching to go back and read the story it’s based on. Lowry is the director of recent films like Pete’s Dragon, A Ghost Story, and The Old Man and the Gun, so him making a medieval fantasy film is an exciting prospect! I’d previously seen the book Sir Gawain and the Green Knight looking through fantasy books under the name Tolkien as he famously translated the book in the 1920s. As a fan of Tolkien and a movie fan excited for the upcoming loose retelling of the Welsh legend, I took the effort this past week to dig into the classic Arthurian story.

Content Guide

Spiritual Content: Most every character in the story is overly Catholic and piously religious Violence: Beheadings and some blood described, animals are hunted for food and sport Language/Crude Humor: None Sexual Content: A woman tempts another man sexually to which he is honor bound not to reciprocate Drug/Alcohol Use: Minor alcohol consumption Other Negative Themes: None Positive Content: Themes of honor, integrity, and honesty

Though primarily remembered now for Lord of the Rings , J.R.R. Tolkien was first and foremost a philologist. He loved language. He was the type of chap who was inclined at a young age to learn Icelandic to better understand Norse fables in their original language. Over the course of his life, he nurtured the ideas and stories that would become the Middle Earth saga as a hobby on the side, which he never intended to publish until convinced by his fellow Inkling C.S. Lewis to submit The Hobbit for publication.

Naturally, some of his most interesting work outside of his Middle Earth Saga comes from his scholastic work as a translator. His most famous translation is his personal translation of Beowulf which he worked on in the 1920s. Like most of his work, it was completed and published posthumously by his son Christopher Tolkien in 2014. Lessor revisited is his much celebrated translation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight .

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight was originally written by an unknown Welsh author during the 14th century at the time of Chaucer. In that and several respects it shares similarities with Beowulf . They’re both medieval epic poems and they’re both functionally illegible to modern English readers. They’ve both since been translated into common parlance multiple times. J.R.R. Tolkien’s posthumously published translation is one of several available.

The titular Sir Gawain is of course the Arthurian character of Anglo-Saxon legend. If you aren’t familiar with King Arthur, the Knights of the Round Table, and the overall narrative of his legend, much of this particular style will likely fail to make much sense. The story picks up in the midst of a festival populated by King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. When a mysterious knight and his horse interrupt the proceedings, the court is offered the chance to take a challenge where in an individual can take a shot at the knight with his axe in exchange for the right to do the same thing to the challenger one year and a day later.

Sir Gawain takes up the challenge in Arthur’s place and successfully beheads the knight in one swing. To his surprise, the mysterious knight picks up his head and walks out of the court, their agreement still very much expected to be honored. Nearly a year later, Gawain sets out as a knight of integrity to allow the mysterious Green Knight to take a free swing at him as agreed to. In the process of his travels, he finds himself in the presence of a powerful lord and his wife who simultaneously guide him in his journey to the Green Chapel and provide him a massive series of temptations. Ultimately, he faces the Green Knight and comes to understand a plot conceived by the sorcerous Morgan Le Fay, Arthur’s half-sister.

Fans of Monty Python and the Holy Grail will likely pick up on the similarities the second act of the story has with The Tale of Sir Galahad , obvious differences aside. In that story, Sir Galahad finds himself trapped in a convent of sexually frustrated nuns who want to take advantage of him before he’s saved by Sir Lancelot at the moment he’s most inclined to give into his temptations. That story is obviously being played for comedy, unlike the poem.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is ultimately a story about the integrity of knighthood. Despite his temptations and the deathly consequences of his actions, he allows himself to be taken down the path of danger and honor and ultimately is allowed to return to the Round Table. As a knight who must live by his code of honor, he’s duty bound to allow the mysterious Green Knight to take his turn in the challenge, even if it costs Sir Gawain his life.

As with most stories of this kind, it’s not that clear cut. This isn’t a story of a man riding off to his inevitable demise. It’s about a man being tempted to compromise and not live up to his code in the face of death. Thus most of the second and third acts are dedicated to Sir Gawain struggling with various temptations. As is appropriate with a story about temptation, his perseverance is ultimately that which saves him.

In some ways, I find Sir Gawain and the Green Knight to be a more interesting story than an entertaining one. Even translated by J.R.R. Tolkien, it’s quite a dry read. However, the details of the story are fascinating to reflect upon. As with most of the great medieval fairy stories, there’s immense depth and religiosity to the text. As Tolkien and his translation partner E.V. Gordon mention in the book’s prologue, the author had to have been a singularly devout and educated soul.

“He was a man of serious and devout mind, though not without humour; he had an interest in theology, and some knowledge of it, though an amateur knowledge perhaps, rather than a professional; he had Latin and French and was well enough read in French books, both romantic and instructive; but his home was in the West Midlands of England; so much his language shows, and his metre, and his scenery.”

Certainly coming a century before the works of William Shakespeare, such a man wouldn’t be hard to find in Great Britain. Yet he’s been lost to history. His works were discovered centuries later and spread in the 19th century.

The book is open to much interpretation given its place in history, cultural background, and the depths of the references it’s calling forth. Gawain’s arc and his story are fairly straightforward in their telling, but the implications of the themes and what they mean are fascinating. He must maintain his integrity and pay penance for the choice he made, but to what is he paying penance to?

Tolkien himself had difficulty interpreting exactly what the titular Green Knight within the story symbolizes. Is he a manifestation of nature given his green color? Not exactly, but that’s a common read. Given what we come to understand about his identity and motivations in the final part of the story, he’s mostly a catalyst to bring about an end result for Sir Gawain and King Arthur. He may very well be a representation of chaos only Sir Gawain can satiate with his integrity. It’s worth remembering Gawain didn’t take the challenge initially out of greed, but out of a desire to serve and protect his king. The challenge as laid out ends up being something of an unfair punishment for a man who technically didn’t do anything wrong.

Still, the Green Knight’s supernatural abilities suggest he’s a greater force than a mere physical challenge. His vagueness implies a greater meaning to his challenge. If we take him to be a symbol of nature, this becomes a story of Christian values overcoming man’s bestial state of nature through their integrity. Only by staying chivalric can order be restored and the knight quelled. Only by maintaining our values in the face of oblivion can we maintain society. As the story makes clear by the end, Gawain isn’t totally dedicated to that standard as a human being who struggles with temptation, yet his perseverance is enough for him to return home. Even so, he feels shame for not totally maintaining his standards.

The entire second act of Gawain grappling with the temptations of a powerful Lord’s wife reflects this central theme as well. Throughout this digression, he’s placed between a rock and a hard place being a knight who must respect the marriage of the man who is giving him shelter while still honoring the requests of a married woman who finds him appealing. To this end, he allows the woman to kiss him and then returns the kisses to the lord as part of an elaborate game he’s decided to play with him. Being a knight of integrity doesn’t just mean having integrity in publi; it means having integrity behind closed doors as well. This is, of course, a trial that his contemporary Sir Lancelot famously fails.

None of this even begins to cover the role Morgan Le Fay plays in the story and what the implications of her schemes have on the themes. Fans of T.H. White’s The Once and Future King know her role in Arthur’s story as an agent of King Arthur’s ultimate destruction. Her showing up here has fascinating implications.

I could go on, but there’s decades of academic speculation on the nature of the symbolism of this book that I’m sparsely prepared to comment upon. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is a blessedly short yet endlessly fascinating read that’s been persistently on my mind in the week since I started reading it. There are many ways to read and interpret the story, but it yields much depth to its reader regardless of your preconceptions. It’s a simple tale of gallantry and integrity that gives way to mythic and mysterious ideas. I look forward to revisiting this story again and again!

+ Complex themes on temptation and integrity + Fascinating characters living by chivalric codes + Brisk length

- Somewhat dry writing by modern standards

The Bottom Line

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is a quintessential piece of Arthurian legend and one of the great pieces of classic medieval literature. J.R.R. Tolkien's translation brings the story to life with gentility and gravitas and makes the old English legible to modern eyes and ears.

| Story/Plot | 10 |

| Writing | 9.5 |

| Editing | 9 |

Tyler Hummel

I don’t have anything interesting to say, I just wanted to say that I really liked this review

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

GDPR & CCPA:

Privacy overview.

The Writer in White

A Journey into Storytelling, across Mediums and Methods.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight BOOK REVIEW

One of the many works of J.R.R. Tolkien published posthumously, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is a necessary addition to the libraries of readers of Tolkien and of medieval English literature. It falls within the scope of the Arthurian legends, following the journey of the virtuous Sir Gawain as he embarks on a quest taking him far from Camelot. I originally acquired this book following my reading of Tolkien’s translation of Beowulf (which is the best translation of the epic poem I have ever read). I looked for other work and translations done by Tolkien, and to my joy found several within the Arthurian literary cycle.

Before addressing Sir Gawain and the Green Knight , you must understand the impact of the Arthurian legends, also known as the Arthurian literary cycle. The greater body, known as the Matter of Britain, is the medieval literature and legendary material regarding the great kings and heroes of Britain, of which King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table are prominent. They are an important part of Britain’s national mythology, and their impact can be seen in text, legends, and mythology across Europe. The Arthurian literary cycle is the collection of stories, legends, and poems about King Arthur and his knights, focused on the interwoven telling of two stories: those of Camelot, the doomed utopia of chivalric values, ultimately brought down by the fatal flaws of its heroic characters, such as Arthur, Lancelot, and Gawain; and secondly, the quests for the Holy Grail by the Knights of the Round Table. They combine literature, storytelling, and prose with religion and spiritually, along with humor, romance, tragedy, and triumph.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is a 14th century chivalric romance written by an unknown author, and one of the best known Arthurian stories. Within his translation of the poem, Tolkien’s goal was to interpret the poem for the general reader without losing the narrative skill or the poetic style of the original. Early translations of the text relied heavily on the original form of being written in alliterative verse, as well as the unfamiliar vocabulary and grammar of the author’s English dialect, both of which are difficult to engage with for those unaccustomed to it. It was Tolkien’s expertise in the poetic style, translation from and within Old English, and writing that allowed him to translate a “difficult” poem so that it could be enjoyed by many, not just experts on the subject.

Sir Gawain is a joy to read, though not written to be as easy to consume as contemporary storytelling. As someone who has engaged with only limited work (academic transitions, not retellings) from the medieval period, this book was an enjoyable read, though not a casual one. Written in the style of medieval literature, the reader must be attentive to fully engage with the text, but I imagine anyone reading translations of Tolkien’s will be more than mindful. It is “…a romance, a fairy-tale for adults, full of life and colour.” In the poem, we follow Sir Gawain and are shown the ideals of medieval chivalry that were highly esteemed by the author, as well as across much of the Arthurian legends. In Gawain, we see an idealized knight, vibrant, chivalrous, and nearly virtuous nearly to a fault. His journey across the land to reach the Green Knight is a quest worthy of a knight, and we watch as his quest to prove his worth puts his honor and knightly values to the test.

In addition to Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, the book also contains Tolkien’s translations of Pearl and Sir Orfeo . The first is a poem written by the same unknown author of Sir Gawain , found in the same original manuscript. It has a much different feel to the Arthurian tale, as it is an elegy, or lament, on the death of a child. The commentary on Pearl provided within the Introduction was quite compelling, and I imagine the poem would be a topic of interesting discussion amongst experts. I found it profound, and a worthwhile read and addition to the book.

Sir Orfeo is included as a personal favorite of Tolkien’s, though no writings regarding it were ever found, and thus the translation has little commentary on it. Christopher Tolkien’s intent was to publish his father’s work with as little external additions, modifications, or commentary, instead relying on what his father left behind. As such, some of his work is unfinished, and some, such as Sir Orfeo , have no commentary. As I read through Sir Orfeo , I found myself following the poetry, in rhyme and meter, where I often have little knack for it. It was surprisingly enjoyable, and several times nearly found myself reading aloud in some subconscious impulse to experience the full effect of the poem. I imagine a proper oratory presentation of Sir Orfeo would be something to behold.

I picked up Sir Gawain and the Green Knight for one reason, and walked away thankful for many more. My suggestions for prospective readers would be to approach it one of two ways. The first would be to read the text, then read the Preface and Introduction for commentary, and finally reread the text and translation with the commentary in mind. This method gives the reader the opportunity to enter without expectations, and allows them to be purely influenced by the text and Tolkien’s translation. The other method for reading this book would be to read the Preface and Introduction first, then reading the poems. This gives the reader the intent of the translations going in, as well as context within the light of the history of the text. I thoroughly enjoyed the three poems in this book, each for their own reasons. They are worth reading as an appreciator of the Arthurian literary cycle and British mythology, or as students of the larger body of Tolkien’s work. It is likewise worth reading as a student of English literature and poetry, as the craft displayed by Tolkien’s translations are masterful, and able to be appreciated by the general reader as well as the studied reader. It is an enriching read that requires thought and focus, and rewards it with a beautiful and timeless work of literature.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is written by J.R.R. Tolkien and edited by Christopher Tolkien, and is published by Harper Collins.

Want to pick up a copy of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Pearl, and Sir Orfeo for yourself or someone you know? Purchase a copy through the link below, and you will help support the Writer in White with your purchase.

https://amzn.to/3eFQcIF

Share this:

Leave a comment cancel reply.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Movie Reviews

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

'The Green Knight' Fulfills A Quest To Find New Magic In An Old Legend

Justin Chang

Dev Patel stars as Sir Gawain, King Arthur's nephew, in The Green Knight. A24 hide caption

Dev Patel stars as Sir Gawain, King Arthur's nephew, in The Green Knight.

As powerful a grip as King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table still exert on our imaginations, there haven't been enough great or even good movies made about them. There have been some, of course — I'm fond of the lush Wagnerian grandeur of John Boorman's Excalibur and will always love Monty Python and the Holy Grail — but they're more the exception than the rule.

So I mean it as high praise when I say that I've never seen an Arthurian sword-and-sorcery epic quite like The Green Knight . With this boldly inventive adaptation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight , an anonymously written but enduring 14th-century poem, the writer-director David Lowery has taken a young man's journey of self-discovery and fashioned it into a gorgeous and moving work of art.

Arts & Life

The only 'new' thing about cross-cultural casting is who's getting the roles.

That young man is Gawain, played by a superb Dev Patel, who slips into these medieval trappings as effortlessly as he did the Dickensian world of last year's The Personal History of David Copperfield . His character is a reckless youth, a kind of Middle Ages slacker whom we first meet in a brothel with his lover, Essel, played by Alicia Vikander. His uncle, King Arthur, is played with a benevolent smile by Sean Harris.

On Christmas, Gawain attends a Christmas celebration hosted King Arthur, but the festivities are interrupted by the Green Knight, a mysterious half-man, half-tree figure on horseback. He suggests "a friendly Christmas game," inviting anyone present to strike him down — on the condition that they must reunite a year later so that the blow can be returned. The impetuous Gawain accepts the challenge and decapitates the Green Knight with a sword. But the Green Knight gets up, calmly retrieves his head and leaves, pausing to remind Gawain that they will meet again in one year.

All this is drawn from the original story, with a few intriguing tweaks: In Lowery's retelling, Gawain is the son of King Arthur's sister, the scheming enchantress Morgan le Fay, played here by a quietly imposing Sarita Choudhury. She gives Gawain a magical green sash for protection as he sets out the following year to meet his fate. Is he doomed to lose his head, or will he, like the Green Knight, somehow survive the encounter?

Alicia Vikander and Dev Patel appear in a scene from The Green Knight . A24 hide caption

That's just one of many questions looming over Gawain's long and episodic journey, during which he'll meet many characters who may help or hinder him. Erin Kellyman plays Saint Winifred, a ghostly maiden who asks him for a favor. Joel Edgerton turns up as a hospitable lord whose castle is a maze of strange secrets.

But for the most part, Gawain travels alone, with only a friendly fox to keep him company. While his quest unfolds at a leisurely pace, it never plods or drags; I felt hypnotized in my seat. Lowery and his cinematographer Andrew Droz Palermo summon up one astonishing image after another as they follow Gawain over misty mountains and through mossy forests. At every step, our hero tries to follow a knight's code of chivalry, performing acts of kindness and resisting the many temptations that present themselves.

Like the original poem, the movie is open to more than one interpretation. You don't need to be a theologian to spot the Christian overtones in the story, in which the Green Knight looms as a kind of Christ figure and Gawain is his lowly disciple. Then again, you could also see the Green Knight as a pagan creation, an avatar of the natural world with which humanity will always find itself in conflict. These tensions, between pagan and Christian belief, are perfectly expressed in Patel's performance, which is both a piercing study in moral anguish and a lusty, charismatic star turn. Lowery's film may be a meditation on good and evil, but it also invites us to contemplate the erotic allure of its leading man.

The intensity of the spiritual inquiry in The Green Knight reminded me of quite a few non-Arthurian classics, like Ingmar Bergman's The Seventh Seal and Martin Scorsese's The Last Temptation of Christ . I was also reminded of Lowery's own films, like the Disney remake Pete's Dragon and A Ghost Story, which put their own offbeat spin on familiar myths and archetypes. The Green Knight is another kind of ghost story, full of eerie visions and strange spirits. It leaves you feeling assured that the old legends, and the movies they inspire, are still capable of conjuring their share of magic.

ⓒ 2024 Foreword Magazine, Inc. All rights reserved.

- Book Reviews

- Foreword Reviews

- Young Adult Fiction

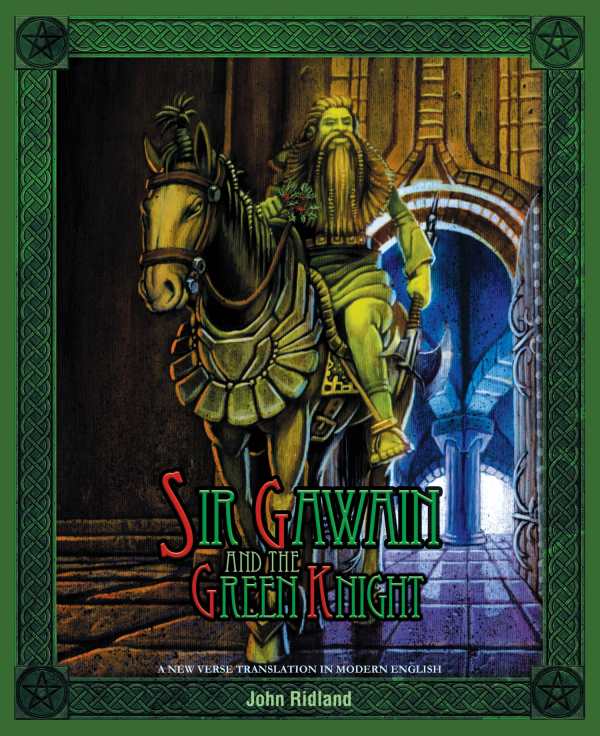

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

John Ridland Able Muse Press ( Aug 22, 2016 ) Hardcover $29.95 ( 124pp ) 978-1-927409-76-3

This well-known classic is translated into modern English verse in this enchanting and captivating book. The activities and challenges faced by the knight Sir Gawain are described in great and sometimes graphic detail as the story moves between what the author calls “hunting” and “bedroom” (interior) scenes. The story follows Gawain’s struggles to live up to the high standards of a knight while he also struggles for survival in the midst of his human frailties and weaknesses. The narrative is structured into four parts, as in the original, each centered around a different event or tale, and even includes a few black-and-white illustrations of the scenes at certain key breaks.

John Ridland, who taught English at the University of California, Santa Barbara, for over forty years, here delivers a version of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight that covers every word of the original and preserves the same line numbering. What gives this translation life, however, is Ridland’s meticulous care in crafting the meter and rhythm of the translation, using tools such as judicious alliteration. The result is a text that preserves the lyrical quality of the original, even if the original meter is no longer relevant. The book also contains Ridland’s introduction and notes, helping to shape the understanding of this text. The resulting work is a must-read for anyone interested in tales of King Arthur, medieval knights, and the wondrous folklore of that period.

Reviewed by Stephanie Bucklin Fall 2016

Disclosure: This article is not an endorsement, but a review. The publisher of this book provided free copies of the book to have their book reviewed by a professional reviewer. No fee was paid by the publisher for this review. Foreword Reviews only recommends books that we love. Foreword Magazine, Inc. is disclosing this in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.

Taking too long? Try again or cancel this request .

The Solomon Code

Official website of the author jd kloosterman, sir gawain and the green knight: a review (11 minutes).

I have a lot of things I want to write about. A lot of things I should write about, instead of playing another round of Terraforming Mars (I just really get excited about space sometimes). My book, for one. A CAPC article on Spiritfarer , for another. I have a blog post in mind about Ready Player One that I really ought to put together sometime, and I actually have a blog post written out about how Catcher in the Rye has a deeply problematic attitude toward sex, but: this thing is a lot more recent and actually timely, so I’m going to write about it instead.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, before it was a movie, is one of the oldest works in the English language, and is in what we would call Middle English, like Le Morte D’arthur and The Canterbury Tales. It’s one of my favorite stories–I wrote my first college paper on it, and I’ve taught it several times in class, despite it being probably a bit too advanced for most high schoolers. It’s fun, it’s clever, it’s got fascinating moral questions involved.

Quick rundown of the poem: Arthur’s giving a Christmas party at Camelot when this massive knight dressed all in green, with green hair and everything, comes in and offers a deal. He’ll take a hit from one of Arthur’s knights if that knight will agree to take a hit from him in a year. Gawain agrees, and chops off his head, whereupon the knight picks up his head and says Gawain should seek him out in a year to get his head chopped off.

Because Gawain’s an awesome knight, he leaves in the Autumn to seek out the Green Knight. He finds this lord, Bertilak, who knows where the Green Knight is. He stays at Bertilak’s house, where the lord’s beautiful wife tries to seduce him, but Gawain, despite being majorly into the lady, holds off because (a) he’s a guest and you don’t do that to your bro, and (b) he’s got a deal going with said bro that he needs to give Bertilak whatever he “gets” in the castle that day. Finally the lady accepts that Gawain’s too honorable to give in, but offers him a love-token to remember her by–a green belt that she says will make him invincible.

Gawain takes it, and doesn’t tell Bertilak.

SPOILERS FOLLOW

Gawain finds the Green Knight, and is required to kneel and not even flinch while the Green Knight swings at his head–but the Green Knight misses, only giving Gawain a little slash on the neck. Gawain jumps up and is super excited because holy cow now the promise is fulfilled and he can just take on the Green Knight in a good old-fashioned battle, but Green Knight just laughs. Turns out he’s Bertilak, and this whole thing–including the attempted seduction–has been a test, devised by Morgan le Fey. Gawain pretty much passed it–except for the belt. That’s his failure, and that’s why Green Knight gave him a knick on the neck.

(Side note here: This is far from the only time in medieval epics when the host of a castle gets his wife or daughter to attempt to seduce a protaganist as a test of character. Guess lords just thought it was fun playing games like that.)

Gawain is “passing wroth”, as they say, and tears off the belt and says he’ll take the blow again without it, and throws in some medieval sexism for good measure about how this is just typical and how women always lead men astray. But the Green Knight refuses, and says he thinks Gawain’s done pretty good, all things considered. He even invites Gawain back to dinner to celebrate New Years with him and his wife. Gawain, understandably, refuses.

Gawain goes back to Camelot and tells the whole story, showing the belt. Everyone’s super impressed and tells Gawain he was awesome, not having sex with the lady and totally being willing to get his head chopped off. But Gawain doesn’t think so. Gawain thinks he’s a complete and utter failure, for being so afraid of death that he was willing to betray his vows. The poem ends, then, on a note of ambiguity. Is Gawain being too hard on himself, or is he, indeed, not the perfect knight everyone sees him as?

So I was initially hesitant, but eventually greatly excited, to see news of A24’s adaptation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. The story doesn’t exactly lend itself to the sort of fantasy epic movie you see these days, and I worried they were using the name-recognition for some action-packed story with massive armies and convoluted gadgetry. However, subsequent trailers showed that they were indeed keeping it small and focused around the central conceit–if using somewhat… bizarre imagery to tell the story. Which honestly, made sense. Medieval poems are not meant to be realistic, strictly speaking, and the strange imagery suggested a lyrical approach. I felt hope that this might be a genuinely engaging adaptation.

And it… sorta is? I’m still sorting through my opinions on it. It makes several glaring changes to the story that in some ways eliminate the central message and tension at the core of the poem, but at the same time it gets at similar ideas in a totally different way. It’s an interesting movie, but it isn’t a good Green Knight adaptation.

First, Sir Gawain. Oddly enough, I felt no qualms about Dev Patel playing Sir Gawain, and I never really heard anyone else voice them either. You’d think it’d be controversial, an Indian actor playing a British follklore hero, but there was nothing. He doesn’t even seem out of place in the film, perhaps because of its very stylistic nature. He fills the role with great personality, showing a wide range of emotion and vulnerability in Gawain’s character, seeming both a vulnerable, directionless youth, and someone who aspires to be a knightly hero with great deeds to his name.

It’s an interesting character, but it’s not the character in the poem. Sir Gawain in the poem is one of King Arthur’s most loyal knights, who takes the challenge of the Green Knight as a way of protecting his sovereign and restoring the honor of Camelot. Sir Gawain in the movie is not even “Sir” Gawain, simply Arthur’s nephew who has barely spoken with his royal uncle before the movie starts, who challenges the Green Knight not to protect Arthur so much as to establish his name as a doer of great deeds.

Sir Gawain in the poem is also considered the pinnacle of chivalry, one of the greatest knights, not just in loyalty and prowess, but in valor, honor, courtesy, etc. He’s a virtuous knight. On the other hand, while Dev Patel’s Gawain has a certain honor and gallantry he aspires to, he makes no pretense to religiosity or virtue. Perhaps this is an element that would simply not translate well to a modern story, but the movie opening with Gawain waking up in a brothel seems… deliberately subversive.

In a way, this makes Gawain’s quest more interesting, as a way of a young knight establishing himself, rather than that of a veteran upholding his reputation–Gawain choosing what sort of knight he wants to be. But it also undermines the great importance of Gawain’s hunt for the Green Knight in the first place, turning it into a quest for self-fulfillment instead of the greatest test of a veteran,

Second is the challenge itself. The Green Knight simply suggests (via letter) a friendly swordfight. When Gawain takes it (because he’s a nobody who hasn’t proved himself yet), the Green Knight kneels and offers his neck to be cut. Arthurs warns Gawain to take the fight as just a game, but Gawain straight up chops the head off, and then things proceed. Unlike in the poem, Gawain chopping off the Knight’s head is seen as a failing, not a sensible move.

Third is when Gawain meets Lord Bertilak. (There’s a bunch of added filler which is not bad).

A lot of the plot elements are the same. Understandably, they streamline the seduction–but it’s really almost as if Gawain does, in fact, give in to Lady Bertilak. Not going to expand on that except to say that it is a very… borderline case. Then in a very odd bit, Bertilak catches Gawain outside the castle and implies that “I think something was given–and I could take it, if I wanted.” It’s almost suggesting that Bertilak has entrapped Gawain as a way of compelling Gawain into having sex with him. The sequence feels like the director doing a “this is what is really going on in this part of the poem” interpretation.

The meeting with the Green Knight is where the director just goes completely into left field, though. (SPOILERS, obviously)

You never find out that the Green Knight is Bertilak. There’s no revelation that this whole thing has been an elaborate test, or what even was the point of that bit in the castle–that’s just left as another irrelevant adventure.

In fact, Gawain doesn’t even keep the belt on.

There’s a sequence–which really accomplishes its purpose rather well–where Gawain imagines himself fleeing, surviving, going back to Camelot and becoming king, living out the rest of his life–but it’s a paltry, unfulfilling life, haunted constantly by the knowledge of his failure. It’s easily the most depressing bit in the film, and is a big part of what left me feeling so disturbed when I left the theatre.

The sequence ends, and Gawain is still facing the Green Knight. He takes off the belt, and says he’s ready.

The Green Knight says, “Well done, my brave knight. And now… off with your head.”

And that’s it. That’s the end. Cut to black.

On the one hand, it has a big impact–what if the deal was as fatal as everyone assumed? What if it really was about a knight meeting their death with courage and dignity and there was no last-minute “twist” that turned it into a happy ending?

On the other hand, it completely undoes the whole ambiguity–is Gawain a good knight, or a bad one? What even was the point of this “test?”

The ending is in part what makes me feel the movie is a good story on its own terms, but not on any level a faithful interpretation of the poem, and in fact one that betrays most of its key themes.

On a basic level, an ending like that pictures very well the medieval ethos at the heart of the poem–that dying well is better than living poorly. The director states, in an interview , that the purpose of the “escape fantasy” where Gawain imagines himself running away to lead a miserable life as the new king of Camelot was to give the “off with your head” ending a triumphant feel instead of a depressing one. And it truly does! It was an immense relief to me to realize the whole thing was a fantasy, and the moment when Gawain took off the belt seemed to crystalize his transformation to a man of honor.

So on that level, the adaptation works, and indeed is more stirring in that it suggest Gawain truly does die for his honor. This was the medieval mindset–the ancient Anglo-Saxon mindset, for that matter, and likely the mindset of people in other cultures I’m less familiar with. You can’t control fate, you can only meet it. You must “take the adventure that fate has granted you.” If a dragon attacks your kingdom, cowering in the castle is simply not an option, you need to go out and meet it, even if you end up being burnt to a crisp. If you’re sitting with all the knights at a table and a magical cup floats through the hall, you must take up the quest to find it again. Or, say, if a Green Knight comes in to suggest a “game.” You’ve been presented with a challenge. Maybe you’ll die, maybe not, but you need to try. There’s a line in the poem, when people tell Gawain he doesn’t need to meet the Green Knight:

Þe knyȝt mad ay god chere,/ And sayde, ‘Quat schuld I wonde? / Of destinés derf and dere / What may mon do bot fonde? ‘

“But Gawain he made good cheer. / He said ‘Why should I fly? / In occasions good or ill / good men can but try.”

So on that level, the adaptation works. But here’s the thing–I’m not positive the director intended that, or that it quite works. Possibly because the concept of “honor” is nebulous in the movie, and indeed in the modern mindset.

The “escape fantasy” segment doesn’t really show Gawain’s life as miserable because of the dishonorable secret. The misery that he’s inflicted with–having to desert the woman he loves, marry another he doesn’t, losing his son, experiencing war, revolt, desertion–doesn’t really have to do with a lack of honor, at least not in any way that’s clear. The director really seems to be saying that life, itself, is not really so great and is full of misery and pain.

And this gets at the heart of the differences, which come down to the director actually rooting for the Green Knight.

See, the director also says that he sees the Green Knight as emblematic of nature–which is true in a way, since the Green Knight was likely a medieval reference to the “Green Man” of pagan tree-worship. Alicia Vikander, who plays Lady Bertilak (as well as Gawain’s prostitute-lover) has a long speech about how green (plants) always survive and supplant, how trying to kill them never works and how they eventually fill and destroy buildings and castles.

This is probably why the Green Knight is never revealed to be Bertilak. The director intends the Green Knight as an elemental avatar, to him it ruins the point for the whole thing to turn out to be a moral test. Indeed, the point is that nature SHOULD kill Gawain and the petty miserable life of civilization that he represents. Arthur, in the movie, is a frail and sickly man, which the actor manages to turn into a saintly, sensitive king, but which the director also flatly states he intended to show how Arthur’s christian Camelot is sickly and dying.

Basically, then, while the original poem is in part about defending Arthur’s modern christian civilization from the dark magic of pagan nature-worship, the film adaptation is about how modern civilization should really just collapse already and let nature take over–a viewpoint that does exist among certain (fringe) environmentalists.

This gets at two interesting questions–Who determines what a story means, and what makes for a good adaptation?

Many people assume the answer to the first is fairly simple–a story means whatever its author intended it to mean. They shaped the tale, after all, and presented the characters and the world and the actions and consequences, so their intended message is what shaped the overall story, so that is what it means.

However, no less a scholar and writer than CS Lewis disa greed with this. “…an author doesn’t necessarily understand the meaning of his story better than anyone else ,” he told Dr. Clyde Kilby, a fan of his, in a letter. (It took me a long time to find this specific quote, but since Lewis is one of the most misquoted authors in the English language, it was worth the effort). Lewis saw literature as seeing through another person’s eyes at the world, but you might see something quite different there than what the original author intended. Modern scholarship views a story’s meaning as something “navigated” between author and reader. People can, of course, read things into stories that aren’t there, but an author can end up making a totally different point then they intended.

An example: Quentin Tarantino sees himself as an anti-violence movie director.

No, really. Quentin Tarantino considers all his movies to be about how violence is hollow and results in emptiness–and how films that glamorize it are cheap schlocky hack jobs. It’s actually easy to see this in films like Inglourious Basterds, where the titular Basterds are simple psychopaths who stumble into and nearly ruin a perfectly good assassination plan put together by a Jewish cinema owner.

But here’s the thing. Does anyone watching a Tarantino flick actually see that? Tarantino may intend a message like that, but the way he lingers on violence and exults in savagery instead amounts to a fetishization of death and gore. The meaning that Tarantino has created is one that glorifies violence–in part because, while he may think he’s making an anti-violence film, he still thinks violence in films is fun.

Another example: I once read an article by a scholar who argued that Pride and Prejudice was a tragedy where aspiring feminist Elizabeth Bennet instead submitted to the patriarchal authority of her father and Darcy. This argument seems ridiculous on the face of it–until you realize that this is truly what a feminist sees in Pride and Prejudice. To a certain class of feminist, the moment when Elizabeth agrees to marry Darcy carries the same tragedy as the moment when Bella agrees to marry Edward instead of Jacob.

(Mind you, since the moment is portrayed as happy in the book, I think it ridiculous to assert that Jane Austen intended this, or that this “tragedy” is what gives Pride and Prejudice such enduring appeal. People don’t like it because it’s a tragedy, they like it because it’s a happy ending. The scholar who wrote the article probably didn’t like the book, which is her right, but that doesn’t change the meaning)

So while understanding the director’s intention in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is important, it’s not the whole story. He intended Arthur to be an almost alien otherworldly force, but the actor turned Arthur into a sensitive sage. To him, the story is about nature triumphing over society, but someone viewing the movie might instead see the medieval ethos of facing death with dignity.

Well, still, it is a far cry from the poem. Is it a bad adaptation?

This is the second question. If a work does not always mean what an author intended, then can an interpretation that changes the meaning be said to be bad?

Everyone has at least heard of The Shining, and is probably most familiar with the stunning adaptation by Stanley Kubrick. However, what is less known is how much Stephen King, the original author, hates that adaptation (he’s since warmed up to it). King even directed an alternative Shining (as a miniseries ) that follows the book more closely than Kubrick’s does–though, since King is not Kubrick, it is decidedly worse.

One of the key ambiguities in the film is whether the Overlook hotel is truly malevolent, or if Jack Torrence is simply an unhinged man driven crazy by cabin fever and alcoholism to violence against his family. King’s book, though, has little such ambiguity. There, the father is genuinely trying to be a decent man, fighting against clear spirits infecting the Overlook Hotel. He even manages to regain control for just long enough for his son to escape. He’s a father trying to do his best, but helpless in the grip of powers larger than himself.

Perhaps King is being disingenous when he claims in On Writing he had no meaning in mind when he, an author struggling with alcoholism and drug abuse, wrote a story about an author struggling with alcoholism and drug abuse and also evil hotel spirits. Perhaps not. Again, King is not necessarily the best judge of what his stories “mean.” Even if one doesn’t view Jack Torrence as a stand-in for King’s own tortured struggle with alcoholism, it’s understandable why King would object to such a dramatic shift.

Yet unquestionably The Shining is an effective and brilliantly disturbing movie. It changes the characters, omits scenes and invents new ones, kills off characters that survive the book, and removes a central tension, creating instead a new ambiguity. It conveys the sense of terror in King’s book, the fear of isolation and of a possibly malevolent building.

King has since reconciled with the movie by taking a new stance toward adaptations of his work–viewing them as entirely their own thing. Based off his work, yes, but not necessarily “true” to those books. A book is not a movie, after all, and even a book is “based off” many other works. Even if The Dark Tower is nothing like King’s book The Gunslinger, that does not make it a bad movie.

You could say this of many films. Starship Troopers is a satire of a wholly serious sci-fi novel. Pride and Prejudice (2008) is an excellent movie, but in some ways completely reverses the original novel’s focus on, well, pride and prejudice. (It makes Darcy shy instead of proud, and severely downplays Lizzie’s realization that she never gave Darcy a fair chance after that first faux paus). A friend of mine once risked his entire relationship with me by saying the Lord of the Rings movies were not good adaptations of Tolkiens work, as they did not convey the flavor of Tolkien’s archaic language and prose. I’m not sure you could, quite, manage something like that, but I see his point.

I would myself say that a film purporting to be an adaptation can be a good film regardless of how well it conveys the source, but what makes it a good adaptation, as opposed to simply a good movie “inspired by” the original, is how well it conveys the themes and tone of the original source–particularly those themes that gave the original such enduring appeal. By this measure, King’s The Shining miniseries may be a good adaptation but a bad movie, while Pride and Prejudice is a bad adaptation but a good movie.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight toes this line very finely. It conveys some of the tone and themes but betrays the central moral. It is best viewed as a very divergent take on the poem. I don’t agree with the message intended by the director, though I think he conveyed more than he meant to. The poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is a Middle English work that simply was never designed to be translated to film, and as a poem it is a brilliant and clever glimpse into the medieval mindset. They are each their own thing, and ought to be viewed as such.

Share this:

2 thoughts on “ sir gawain and the green knight: a review (11 minutes) ”.

This was so enjoyable to read!

Oh good. That was the idea.

Leave a comment Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Find anything you save across the site in your account

“The Green Knight,” Reviewed: David Lowery’s Boldly Modern Revision of a Medieval Legend

David Lowery’s new film, “The Green Knight,” is an adaptation of the Arthurian poem of “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight,” but it’s no more about medieval life and chivalrous norms than Martin Scorsese’s “ The Wolf of Wall Street ” is about stocks and bonds. Instead, Lowery, who both wrote and directed the movie, follows in the path of one of his previous works, “ A Ghost Story ”—which he created outside the studios, with a personal sense of urgency—to make a rueful and mighty work of apocalyptic cinema. Just as Scorsese spotlights, in “The Wolf of Wall Street,” money hunger as society’s original sin—which affects his viewers and the world at large no less than it does his antihero—Lowery portrays the bold challenge facing Gawain (played by Dev Patel), in his confrontation with the titular monster (Ralph Ineson), as a folly and a delusion far more comprehensive than the codes of knighthood. Lowery’s underlying subject is martial valor, the test of violence that stands as a misguided model of manhood and which corrupts and ravages current-day society at its very core.

Gawain, a callow young nobleman, is introduced in the movie’s first shot, one that, true to Lowery’s tone throughout, is as contemplative as it is spectacular. It is an extended-take long shot that moves gradually back from an animal-filled courtyard, through a window, to land on a visage of the sleeping hero. He’s awakened, with a comedic rudeness, by a splash of water in the face, delivered by his lover, Essel (Alicia Vikander), a prostitute in a teeming bawdy house with whom he has just spent Christmas Eve. He goes home, where his mother (Sarita Chowdhury) teases him about his night out—but there’s already trouble afoot in the kingdom, because Gawain’s night of love with the joyful, compassionate, and wise Essel is indeed a sacrament, one that his society, no less than our own, would recognize as such.

Taking his place at a Christmas feast hosted by his uncle, King Arthur (Sean Harris), Gawain is called upon by the ruler to tell a tale of himself—and finds that he has no tale to tell, which is to say he has no tale that he deems worthy of telling a table of battle-tested warriors. But Gawain’s tale is being written—by his mother, who applies witchcraft to set Gawain on his ostensibly heroic path. Her mystical ways conjure a monster, a green-clad, seemingly tree-like giant who turns up at the feast with a challenge: that someone deal this Green Knight a sword blow and take possession of his mighty axe, on the condition that this person, the following Christmas, show up at the Green Knight’s Green Chapel to accept a blow from him. The risk is obvious and none of the knights at Arthur’s table dare accept. But Gawain breaks the ostensibly cowardly silence, takes up the challenge, and decapitates the Green Knight in a single blow. The monster isn’t killed, however; he rises and lifts his severed head, which speaks and laughs and leaves, to await Gawain in a year.

Gawain, a noble nobody, becomes an instant celebrity: the tale of his bloody blow to the Green Knight is bruited about far and wide in the kingdom. Children watch a puppet show in which he’s the hero. He sits for a portrait. Drinkers in a tavern recognize him and deem themselves honored by his presence, and Gawain in turn lives like a swell-headed young celebrity, carousing with them every night and stumbling home splattered in mud and contented with his bloody deed. Yet, when he’s prepared to live on his legend and welch on his end of the bargain, his mother forces him onto the road to seek the Green Knight: “Is it wrong to want greatness for you?” (She’s a maternal martial instigator akin to Volumnia in Shakespeare’s “Coriolanus.”) (Before he leaves, he spends another night with Essel, who tries to persuade him not to leave. He declares that his “honor” depends on it, but she scoffs. “This is how silly men perish,” she says, adding, “Why is goodness not enough?” Yet Gawain sets forth on his dubious journey, riding off on horseback and followed by children who call his name and cheer him on. This scene is intercut, movingly, with Essel’s proposal of marriage to Gawain (done with wit—she moves his jaw with her hand and impersonates him proposing to her), which he spurns in view of his adventure.

Avoiding spoilers, suffice it to say that Lowery shares Essel’s point of view regarding not only Gawain’s adventure but the entire system of values on which it’s based—a system that insures Essel’s exclusion from the high society that lionizes Gawain and is preparing him for power. An air of grim foreboding launches Gawain’s journey to the Green Chapel, when he soon happens upon a battlefield strewn with unburied corpses. There, Gawain encounters a young man—a boy, really (played, with a Shakespearean flourish, by Barry Keoghan)—who says proudly that his two brothers lie dead there, and bitterly complains that his mother wouldn’t let him go to battle alongside them. Though the cards seem stacked against Gawain, Lowery, by means of his fundamental and inspired cinematic artistry, nonetheless conveys the glory and the wonder that illuminate and exalt the journey. The encounter on the blood-soaked plain is realized in a single long, thrilling, and starkly graphic tracking shot that evokes the extraordinary and the mysterious even amid the unrelenting horror of death in war.

Lowery fills “The Green Knight” with such astounding visions: a three-hundred-and-sixty-degree pan shot that conjures Gawain’s dire foreboding; a majestic crane shot over a hilltop that reveals the presence of diaphanous colossi; a galaxy that appears in the depths of water; a talking fox. These moments of visual poetry, using images in the place of lyrical language, evoke a realm of magic and of living fantasy that make the world of Gawain alluring, enticing, bewitching, seductive, inspiring. Yet that world comes off as no mere fantasy but as a synecdoche of the world of our own, here and now. The wonders and mysteries, the dramatic encounters and narrow escapes, the suspenseful journey and the dazzling images all add up to the kind of tale that Gawain, at the story’s outset, didn’t have, the only kind of tale that he deems worth telling—and the kind of tale that current-day readers and viewers, as consumers of stories, deem worth reading or watching.

As in “The Wolf of Wall Street,” the seductiveness of the misguided venture is central to the idea of “The Green Knight.” Lowery’s subject isn’t what’s wrong with the quest to become a knight—it’s the very world in which “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight” has been handed down, from generation to generation, as an exemplary work of literature of heroes tested in battle, consecrated in blood, and celebrated for killing. In Lowery’s “A Ghost Story,” the ghost isn’t just an apparition but a silent and ubiquitous eye that gives the audience a privileged view of the horrors of history and their perpetuation in the present day. In “The Green Knight,” Lowery revises a legend, in style and in substance, in order to evoke a way of telling different stories, and of telling stories differently. He takes the risk of perpetuating a deluded gospel of evil, or of seeming to do so, in a daring effort to dramatize a world in desperate need of artistic redemption.

New Yorker Favorites

- Why walking helps us think .

- Was Jeanne Calment the oldest person who ever lived —or a fraud?

- Sixty-two of the best documentaries of all time .

- The United States of Dolly Parton .

- Was e-mail a mistake ?

- How people learn to become resilient .

- Sign up for our daily newsletter to receive the best stories from The New Yorker .

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Get the Reddit app

r/Fantasy is the internet's largest discussion forum for the greater Speculative Fiction genre. Fans of fantasy, science fiction, horror, alt history, and more can all find a home with us. We welcome respectful dialogue related to speculative fiction in literature, games, film, and the wider world. We ask all users help us create a welcoming environment by reporting posts/comments that do not follow the subreddit rules.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight-J.R.R. Tolkien translation review

After seeing The Green Knight movie last year, I decided to finally read the epic poem it's based on. So I picked up the copy that Tolkien translated and was published after his death that also includes Pearl and Sir Orfeo

I'll tell you right now, I don't know if it's all editions, but I kinda wish I had found a copy like some of the other Posthumous works like Beowulf or Sigurd or the Children of Hurin that had lots and lots of footnotes to explain some of the prose like what you see in those Barnes and Noble Classics. After all it is a translation from Middle English

I could follow the narrative easy with how it flows and having seen the movie did help, kinda, to at least put names to faces. Even if the movie is a different take than the Tolkien translation And it is a quick ready you can do in about oh....a couple hours

Pearl is a very complex religious poem that I felt like I needed to be in Medieval literature 101 just to make sure I was reading it right

Never heard of Sir Orfeo until this book and reading it, I could see in a very round about way where themes and ideas for Middle Earth come from. About a king who gives up everything to go seek his stolen wife and all he has is a harp.

By continuing, you agree to our User Agreement and acknowledge that you understand the Privacy Policy .

Enter the 6-digit code from your authenticator app

You’ve set up two-factor authentication for this account.

Enter a 6-digit backup code

Create your username and password.

Reddit is anonymous, so your username is what you’ll go by here. Choose wisely—because once you get a name, you can’t change it.

Reset your password

Enter your email address or username and we’ll send you a link to reset your password

Check your inbox

An email with a link to reset your password was sent to the email address associated with your account

Choose a Reddit account to continue

- Literature & Fiction

Sorry, there was a problem.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight Paperback – Import, January 1, 1979

- Print length 160 pages

- Language English

- Publisher OXFORD

- Publication date January 1, 1979

- ISBN-10 0048210390

- ISBN-13 978-0048210395

- See all details

Product details

- Publisher : OXFORD; New Ed edition (January 1, 1979)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 160 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0048210390

- ISBN-13 : 978-0048210395

- Item Weight : 4.6 ounces

- #10,167 in Poetry Anthologies (Books)

Videos for this product

Click to play video

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight; Pearl; [and] Sir Orfeo

Amazon Videos

About the author

J. r. r. tolkien.

J.R.R. Tolkien was born on 3rd January 1892. After serving in the First World War, he became best known for The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, selling 150 million copies in more than 40 languages worldwide. Awarded the CBE and an honorary Doctorate of Letters from Oxford University, he died in 1973 at the age of 81.

Customer reviews

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 5 star 82% 12% 4% 1% 1% 82%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 4 star 82% 12% 4% 1% 1% 12%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 3 star 82% 12% 4% 1% 1% 4%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 2 star 82% 12% 4% 1% 1% 1%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 1 star 82% 12% 4% 1% 1% 1%

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Customers say

Customers find the book great and classic, with useful appendices on pronunciation of Middle. They also appreciate the translation, which is very well done and reasonably priced. Readers also find the readability fun and easy to understand, with a brief glossary for weapons.

AI-generated from the text of customer reviews

Customers find the book rich in cultural mythology. They also say it's an interesting story with heavy Christian messaging. Readers also appreciate the useful appendices on pronunciation of Middle English.

"... Really interesting story actually if you like Arthurian legends. And throw in Tolkien? That just made it all the better!" Read more

" Great addition to my Tolkien library " Read more

"...I appreciated the overall story and message . But simply as "a read" I found it less enjoyable and myself rushing through many of the stanzas...." Read more

"...'s insights are to be trusted, and this particular book provides useful appendices on pronunciation of Middle English, notes on word meanings and..." Read more

Customers find the translation very well done, with an excellent glossary that points to when in the poem each listed word. They also describe the book as beautiful, enlightening, and colorful. Readers also mention that the font and layout are okay. They say the pages are unique and the gold on the cover is striking.

" Beautiful book poem like & enlightening too!" Read more

"...The font and layout are A-OK though. This is a fine edition for anyone wanting to read these tales...." Read more

"...The translation itself was well done keeping the alliterative verse and was an interesting story with heavy Christian messaging...." Read more

"...medieval material such as this, but so often the translations are not very accessible . Tolkien is one of the best." Read more

Customers find the book fun to read, easy to understand, and great at fantasy and adventure. They also mention that it has a flavor of old English.

"...it becomes a thoroughly enjoyable and enriching experience to travel back nearly 700 years to recite this..." Read more

"I got this book to read and I love how easy it is to use however, I really wish there was a transcript of some kind that came with it which will..." Read more

"This was really interesting to read prior to David Lowery's film adaptation...." Read more

"...This was an absolute pleasure to revisit ." Read more

Customers find the book imaginative, rich in cultural mythology, and a great look at the interplay between chivalry and courtly love.

"...I really enjoyed "Gawain." This is a great look at the interplay between chivalry/courtly love..." Read more

"...single surviving copy of it, so that we could realize how diverse, imaginative and rich in cultural mythology that Medieval society was...." Read more

" Clever and entertaining story. Gotta love Tolkien." Read more

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- About Amazon

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell products on Amazon

- Sell on Amazon Business

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Become an Affiliate

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Make Money with Us

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Amazon and COVID-19

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- Alternative

- Biographies

- Children’s Comics

- Franco-Belgian/Ligne Claire

- Independent/Self-Published

- Infographics

- Law and Comics

- Miscellania

- Philippines

- Politics and Comic Books

- Science Fiction

- Slice of Life

- Superheroes

- United Kingdom

- United States

- Western Comics

Read a Random Post

Emily: Emergence (Review)

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (review)

- February 3, 2022

Writer: John Reppion

Artist: Mark Penman

Independently published, 2021

Aficionadoes of medieval English will enjoy this new interpretation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight , a tale written in around 1350AD and forming part of the canon of the tales of Camelot. Appropriately, it is put together by two Englishmen, John Reppion and Mark Penman.

Any review of an Arthurian legend requires the critic to arm themselves with the sword of symbolic interpretation, and a dog-eared copy of La Morte d’Artur as a shield. Messrs Reppion and Penman have decided to spare their readership the Middle English version of the tale with its bob and wheel pentameter. Instead, we have an intermingling of narrative by rhyme and contemporary English dialogue.

Interestingly, the creative team have confined themselves to three colours: black, red and green. Red is the colour of both passion and martyrdom. There is no mystery around why Sir Gawain is coloured red: he offers himself up to the Green Knight’s game, and then keeps to his chivalric oath to meet the Green Knight’s axe in a year (and here, again, red is important – in Medieval Christendom, calendars were writing in red, giving us “red letter days”).

The colour green is inevitable, given the subject matter. But green is symbolic of rebirth and fertility – the Green Knight’s ability to survive decapitation is better thought of as a manifestation of an over-abundance of life – and through out story the Green Knight is surrounded by leaves and trees.

We found the colours startling – the green is extremely bright, pervasive, and contrasts spectacularly with the red so as to precisely delineate the major characters. And the drawings themselves have a decidedly woodblock feel to them: some of the leaves especially (see the image above) could be derived from decorative woodwork.

But it is Mr Penman’s layouts which steal the show. In this particular panel below, Sir Gawain is depicted as a fox. Foxes are traditionally regarded as crafty and untrustworthy. They do not run in a straight line. It is an interesting interpretation of Sir Gawain’s character, especially having regard to his interaction with Lady Bertilak. Sir Gawain is not really a duplicitous and cunning fox, even in the eyes of Lord Bertilak, who knows how the fox runs into a trap. Sir Gawain is quarry, pursued by the hunt.

We have a few complaints about this title. First, the comic has been put together as a ‘zine. A production of this calibre deserves a better physical format than folded A3 paper bound with two staples. The creators vastly undersell themselves. Second, in this rendition, Sir Gawain was clearly seduced by Lady Bertilak, not merely “kissed”, evidenced by her hand hovering over his exposed lower stomach. The traditional tension within the tale between honour (being a guest of his host) and knightly duties (obeying a damsel) seems trampled by that panel. Sir Gawain here seems to have consummated his desire – he did not show resistance to temptation, but outright lied to Lord Bertilak de Hautdesert and certainly deserved more than a nick of the axe. Perhaps we are too churlish, but the burly Lord Bertilak might have taken from Sir Gawain exactly what Lady Bertilak gave to Sir Gawain. The knight would have been somewhat less pious by the end of that version of the tale.

What is it at the moment with knights? This is not the only comic book adaption of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight in recent times. Emily Cheeseman released her own version https://www.emilycheeseman.com/greenknight/ in 2017, with art inspired by Alphonse Mucha rather than Caxton. Our colleague Terry Hammond also recently reviewed Once & Future https://worldcomicbookreview.com/2022/01/20/once-future-review-the-night-reawakens/ and Quick the Clockwork Knight https://worldcomicbookreview.com/2022/01/14/quick-the-clockwork-knight-the-haunted-tower-review/ . Culture augury is an excuse for doom-scrolling, the compulsive consumption of magazines and comics, and for MMORPGs, but we nonetheless do not like the way the bones are rolling in respect of the quiet resurgence of the Western knightly adventure. In between these comics and the commercial success of The Witcher , the rise of pop consumption of heraldry to us suggests the desire for a noble war where the combatants are easily recognised by their pennants. We were bothered by the tarot-esque insight that Sir Gawain here carries a red shield embossed with a star on his long journey, and is compelled to a showdown by honour. (Thank goodness Game of Thrones has ended.)

The creators of this interpretation have a very quiet Patreon site: patreon.com/penmanreppion . They launched the title at the UK Thought Bubble comic book festival last year.

Top Posts and Pages

DC Comics to Retire Flash Titles

Edge of Venomverse: War Stories #1 (Review)

AdventureMan Volume 1 (review)

Scratcher #3 (Review)

The French, lovers of wine and comics

Heroines #1-4 (review)

Happy 40th birthday, American Flagg!

Shaolin Grandmaster Killer #1 (Review)

Prodigy # 1 (Review)

Heroes in Crisis #7 (review)

Operation: Boom! #1-3 v. Detective Comics #443 – “Gotterdammerung!” (comparative review)

It’s Cold in the River at Night (Review)

Goodbye to the Good War: a slow decline of comic books based in World War Two?

Mrs. Vengeance: The Broken Pavement: Part One (Review)

Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur #27 (Review)

Tomb Raider: Survivor’s Crusade #1 (Review)

Nonnonba (review)

Sony in legal challenge with DC Comics over ‘Zero Hour’ Trademark

Mirror’s Edge: Exordium – Free Running with the Plot

Drawn Onward. A Back to Front to Back Tale of Hopelessness and Hope (review)

Revisiting FASHION BEAST (review)—“Earth Day 51”

Infinity Countdown: Adam Warlock (Review)

Technofreak #1-4 (review) – “Are you freakin’ kidding me?”

Tragedies and Redemptions: Batman and Catwoman Are Getting Married

Kingdom Come, Twenty One Years Later

Night Cage #1 (review): You Cannot Cage the Night

Moonshine Volume One (Review)

Warhausen (Review)

Switchblade Stories #1-3 (review)

Un/Sacred Volume 2 (review) —“My sweet wings need your hot spices right now”

From iconic superheroes to underground indie sensations, the World Comic Book Review offers expert analysis and thoughtful reviews to guide you through the dynamic landscape of sequential art.

Do you have comic book projects that you want us to review? Do you want to write for the WCBR? Contact us directly.

Advertisement

Supported by

critic’s pick

‘The Green Knight’ Review: Monty Python and the Seventh Seal

Dev Patel plays a medieval hero on a mysterious quest in David Lowery’s adaptation of the 14th-century Arthurian romance.

- Share full article

‘The Green Knight’ | Anatomy of a Scene

David lowery narrates a sequence from “the green knight” featuring dev patel and erin kellyman..