"Freud and the Literary Imagination"

I. General Structure of the Essay

II. Definition of the Uncanny

-- Freud will take issue with both of these propositions. -- Study of the German words, heimlich and unheimlich (canny/homey; uncanny/unhomey). heimlich , first definition = I, a: belonging to the house; friendly; familiar; I, b: tame (as in animals); I, c: intimate, comfortable; i.e: secure, domestic(ated), hospitable. heimlich , second definition = concealed, secret, withheld from sight and from others; secretive, deceitful = private . -- Note the dialectic of these meanings, summarized on p. 200: what from the perspective of the one who is "at home" is familiar, is to the outsider, the stranger, the very definition of the unfamiliar, the secretive, the impenetrable. -- The term heimlich embodies the dialectic of "privacy" and "intimacy" that is inherent in bourgeois ideology. Therefore Freud can associate it with the "private parts," the parts of the body that are the most "intimate" and that are simultaneously those parts subject to the most concealment (see p. 200). However, in Freud's understanding the "heimlich" will also be something that is concealed from the self . unheimlich : as the negation of heimlich , this word usually only applies to the first set of meanings listed above: unheimlich I = unhomey, unfamiliar, untame, uncomfortable = eerie, weird, etc. unheimlich II (the less common variant) = unconcealed, unsecret; what is made known; what is supposed to be kept secret but is inadvertently revealed . -- Note the implicit connection of this notion of the unheimlich to Freud�s concept of "parapraxis," the inadvertent slip of the tongue that reveals a hidden truth. Schelling�s definition (p. 199): "Unheimlich is the name for everything that ought to have remained secret and hidden but has come to light." Unheimlich thus becomes a kind of unwilling, mistaken self-exposure. In psychoanalytic terms, it provides a surprising and unexpected self-revelation . Freud concentrates on the unusual semantics of these 2 terms: heimlich I = known, familiar; unheimlich I = unknown, unfamiliar heimlich II = secret, unknown; unheimlich II = revealed, uncovered For a diagram of the complex semantic dynamics and oppositions Freud associates with these terms, click here . The word heimlich thus has a meaning that overlaps with its opposite, unheimlich ; the semantics of this word come full circle. -- Freud's thesis: unheimlich , the uncanny = revelation of what is private and concealed, of what is hidden; hidden not only from others, but also from the self . In Freudian terminology: the uncanny is the mark of the return of the repressed . (See "Uncanny" 217)

III. E.T.A. Hoffmann's "The Sandman" and the Psychoanalytic Elements of the Uncanny.

1) Freud stresses the uncertainty of whether the events the narrator relates to us are real or imaginary; for uncanny fiction, this ambivalence will become decisive. (This is Freud's version of Jentsch's "intellectual uncertainty.") 2) For Freud the source of the uncanny is tied to the idea of being robbed of one's eyes. Why? Here Freud turns to the experience of the psychoanalyst: In dreams, myths, neurotic fantasies, etc. loss of the eyes = fear of castration. In "The Sandman" Coppelius, the "bad" father, interferes with all love relationships. He is the powerful, castrating father who supplants (kills) the good father who first protects Nathaniel's "eyes." 3) The uncanny thus marks the return of the familiar in the sense of our psychic economy (in which nothing is ever lost or wholly forgotten). It is the castration complex as part of our infantile sexuality (genital phase) that is re-invoked by the fear of loss of the eyes in this story. What is uncanny here is thus the return of something in our psychosexual history that has been overcome and forgotten. -- Freud's first thesis: The uncanny arises due to the return of repressed infantile material. 4) Other examples of this: The double ( doppelganger ); its source is the primary narcissism of the child, its self-love. In early childhood this produces projections of multiple selves. By doing this the child insures his/her immortality. But when it is encountered later in life, after childhood narcissism has been overcome, the double invokes a sensation of the uncanny = a return to a primitive state. 5) But Freud also relates the double to the formation of the super-ego. The super-ego projects all the things it represses onto this primitive image of the double. Hence the double in later life is experienced as something uncanny because it calls forth all this repressed content: -- Alternative meanings for this form of the double: a. it represents everything that is unacceptable to the ego , all its negative traits that have been suppressed; or b. it embodies all those utopian dreams, wishes, hopes that are suppressed by the reality principle, by the encounter with society . (See "Uncanny" 211-212) This aspect of Freud's theory will become important for our interpretation of Hofmannsthal's "A Tale of the Cavalry." WHY IS THE DOPPELGANGER THE PARADIGM OF THE UNCANNY? -- It represents a psychic �nodal point� with multiple implications, meanings, sources, etc. AMBIVALENCE: The Double Doubled �The fact that an agency of this kind [the super-ego] exists, which is able to treat the rest of the ego like an object--the fact, that is, that man is capable of self-observation --renders it possible to invest the old idea of a �double� with a new meaning and to ascribe many things to it --above all, those things which seem to self-criticism to belong to the old surmounted narcissism of earlier times. But it is not only this latter material, offensive as it is to the criticism of the ego, which may be incorporated in the idea of a double. There are also all the unfulfilled but possible futures to which we still like to cling in phantasy, all the strivings of the ego which adverse circumstances have crushed [. . .].� �The Uncanny� (211-12; emphasis added) (This aspect of Freud�s theory will become important for our interpretation of Hofmannsthal�s �A Tale of the Cavalry.�) Freud's general thesis: The uncanny is anything we experience in adulthood that reminds us of earlier psychic stages, of aspects of our unconscious life, or of the primitive experience of the human species. a. castration b. double c. involuntary repetition; the compulsion to repeat ( Wiederholungszwang ) as a structure of the unconscious. d. animistic conceptions of the universe = the power of the psyche. It sees itself as stronger than reality; e.g. telepathy, mind over matter. These are common conceptions of primitive life. The uncanny arises as the recurrence of something long forgotten and repressed, something superceded in our psychic life = a reminder of our psychic past.

IV. The Uncanny in Literature, in Narrative Fiction.

A. Freud is not entirely satisfied with his own conclusion. Not everything that returns from repression is uncanny. Return of the repressed is a necessary condition for the uncanny, but not a sufficient one. Something else must also be at play here in order to create the experience of the uncanny. B. To understand this, Freud returns to the study of fiction for help. Here we find the 2 sources of the uncanny, its relation to the psychic past, confirmed: 1) uncanny = revival of repressed infantile material = part of individual psychic reality; 2) uncanny = confirmation or return of surmounted primitive beliefs of the human species , such as animism, etc. C. But Freud asks why our experience of the uncanny in our real-life experiences and in fiction are different. His answer (we know it already!) = fantasy is different from reality because it does not undergo reality-testing. -- Therefore, events that would be uncanny if experienced in real life are not experienced as such in fiction. Fairy tales, for example, give many instances of uncanny events that are not experienced by the reader as uncanny. Why? The readers adjust their sensibility to the fictional world . (See "Uncanny" 227) In other words, since uncanny events seem "normal" in the fairy-tale world, and we adjust our expectations to the "normal" state of this fictional reality, we as readers do not gain a sense of the uncanny. Or, we might say: since the characters in the fictional world of fairy tales do not see fantastic events as unusual or uncanny, but take them as a matter of course, the reader also is not led to find these things out of the "ordinary" (for the depicted world). -- Fiction only creates an uncanny effect if the author makes a pretense to realism ; if we as readers believe that real, actual conditions are being narrated. -- The experience of the uncanny in literature depends on the discrepancy between real events and fantastic occurrences in the fictional world. The author promises truth and verisimilitude, but then breaks this promise . (See "Uncanny" 227) -- We, as readers of the fiction, must share the perspective of the character who experiences the uncanny event in the fictional world . See "Uncanny" 229, the example of the severed hand. -- In Hoffmann's "The Sandman," the narrator makes us look through the spy-glass Nathaniel buys from Coppola/Coppelius, the demon optician. (See "Uncanny" 205-206).

V. Summary of the Qualities of Uncanny Fiction

A. Focus is on one central character = the anchor character ; events, people, etc. in the fictional world only have significance in relation to this character. It forms the hub, or center of all events. B. External events are seen through the perspective of the anchor character and colored by his or her psyche; they are projections of the psyche of this fictional character. C. The text thus takes on the quality of a dream text, with manifest and latent content. The real and the fantastic (Freud's required ambivalence) form a unity in the consciousness of the anchor character. This lends some of the events the shimmer of the symbolic because it is undecidable whether they are real or imagined. D. Stylistically, uncanny fiction requires a fusion of objective and subjective narrative styles . We commonly find a realistic frame, which reads like a report or a newspaper article, which is suddenly ruptured by fantastic events. But this rupture is also related with the accuracy and detail of objective narration. E. The reader's perspective must be that of the anchor character ; events must be perceived through his/her eyes, filtered through the psyche of this character. Only when all of these conditions are met is the experience of the uncanny transferred from the domain of the fictional world to the receptive experience of the reader.

The Uncanny

45 pages • 1 hour read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Chapter Summaries & Analyses

“Screen Memories”

“The Creative Writer and Daydreaming”

“Family Romances”

Part 1, “Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of His Childhood”

Part 2, “Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of His Childhood”

Part 3, “Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of His Childhood”

Part 4, “Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of His Childhood”

Part 5, “Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of His Childhood”

Part 6, “Leonardo da Vinci and a Memory of His Childhood”

Part 1, “The Uncanny”

Part 2, “The Uncanny”

Part 3, “The Uncanny”

Key Figures

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Summary and Study Guide

The Uncanny , published in 1919, is one of the most famous of Sigmund Freud’s essays. This is not only because many of his most foundational ideas had their genesis here but because the essay pertains to aesthetics and popular culture, making it both accessible and gripping for a broad readership. The Uncanny is a good example of Freud’s predilection for drawing on aesthetics to support his arguments, and thus a useful introduction to the ideas of this vastly influential thinker. It is also in The Uncanny that Freud sets out some of the most radical tenets of his thought: the primacy of the unconscious and the recurrence of repressed material from childhood.

The Uncanny is also a seminal text in the canon of literary criticism, and an extremely useful codex for any student of literature. Freud’s ideas about literature strongly inform almost any example of contemporary literary criticism that one reads. Although he claims at the beginning of the title essay that he “rarely” dabbles in aesthetics, literature is foundational to Freud’s theories of the structure of the human psyche. There are few texts that so compellingly make the case for literature as a route into the deepest parts of the self. Freud’s basic premise in the essay is to define the uncanny as any experience that reminds us of earlier moments in our psychic development, both individually and as a species.

The Uncanny is a collection of essays that culminates in Freud’s essay of the same name. The first three essays in the collection, “Screen Memories,” “The Creative Writer and Daydreaming,” and “Family Romances,” are brief, and develop Freud’s theories about the connection between infantile development and creative ability. “Screen Memories” establishes the idea that many childhood memories are fictions. “The Creative Writer and Daydreaming” finds a synergy between children’s play, adult imagination, and creative writing. Finally, “Family Romances” elucidates the psychosexual fantasies constructed in the mind of the developing infant.

Freud builds on these brief essays in his essay “Leonardo Da Vinci and a Memory of this Childhood.” The essay is broken into six sections. It opens with Freud claiming that Da Vinci is exemplary not only for his achievements, but for his capacity to sublimate rather than repress his libidinal drives. Parts 2-4 explicate a bizarre childhood memory Da Vinci recorded in his notebooks of being hit on the mouth by the tail of a vulture as a baby. The fifth section focuses on Leonardo’s relationship with his father and its impact on Da Vinci’s work and spiritual beliefs. Freud closes the essay by claiming that Da Vinci was an obsessional neurotic whose capacity to sublimate was inexplicable via psychoanalysis. Freud argues that psychoanalysis can clarify the character but not the origin of Da Vinci’s genius.

Freud’s essay, “The Uncanny,” is divided into three parts. In the opening section, Freud defines his central concept of the uncanny through an examination of the etymology of the term’s German translation, unheimlich . The second section considers Jensch’s reading of E.T.A. Hoffman’s short story “The Sandman,” which is foundational to Jensch’s definition of the uncanny, and Freud’s elaboration of it. The final section of Freud’s essay works through the effect of the uncanny in both literature and real-life case studies.

The first part of “The Uncanny” opens with the declaration that the psychoanalytic paper will concern itself with aesthetics. Freud has investigated the underdiscussed realm of literature’s unpleasurable effects, which include the uncanny. He proceeds with an analysis of the semantics of the terms heimlich (or “familiar), and unheimlich . Freud then takes up the only previous examination of the uncanny, Ernst Jentsch’s 1906 publication On the Psychology of the Uncanny. Jentsch’s definition of the uncanny involves a fear of the unfamiliar, and the experience of intellectual uncertainty. Freud will critique both aspects of Jentsch’s definition.

In the second section of “The Uncanny,” Freud reviews an example of uncanniness in the story “The Sandman,” by E.T.A. Hoffmann , which was originally drawn by Jentsch. Whereas Jentsch considers the most uncanny element of the story to be Olympia, the lifelike doll, Freud argues that the source of the uncanny is the eponymous Sandman, a bogeyman said to tear out children’s eyes. Freud claims that the protagonist’s recurrent fear is traceable to this childhood fantasy, behind which lies an unresolved castration complex. The castration complex is the early childhood fear of retribution from the same-sex parent for unconsciously desiring the opposite-sex parent.

In this section, Freud also examines the theories of Otto Rank and Schelling, as they pertain to the concept of the uncanny. Rank’s notion is that the double is created to preserve the ego from the threat of death. Schelling’s notion is that the uncanny is the appearance of something that should have remained hidden. Freud claims that latent in both theories is the fear of death, which was resolved by what he calls “primitive” societies by animistic beliefs in the power of the mind to manipulate matter. At the close of the section, Freud links this fear induced and inducing doubling to the return of repressed psychic material. The uncanny is about remembering what we would prefer not to recall. For example, being buried alive is uncanny because it recalls the familiar, or “the phantasy of […] intra-uterine existence” (15).

In the final section of the essay, Freud promises to allay the reader’s doubts through clinical examples. For the remainder of the essay, Freud offers examples of the uncanny that involve a repetition of the same thing, linking repetition compulsion as represented in literature to the symptoms displayed by his patients. Fairytales and instances of the dead coming back to life in Snow White and the Bible are not uncanny. Thus, Freud concludes, there is more to the definition. An uncanny effect is produced, he asserts, when repressed infantile complexes are revived by some experience in the adult’s life. Infantile complexes are intimately connected with animistic beliefs.

Finally, Freud returns to a discussion of the uncanny in literature. Storytellers “take advantage” of their readers’ “superstitiousness” to “control the current of their feelings” (19).Silence, solitude, and darkness are trademarks of the uncanny that relate to the infantile morbid anxiety “from which the majority of human beings have never become quite free” (20).

Related Titles

By Sigmund Freud

Civilization And Its Discontents

Moses and Monotheism

The Freud Reader

The Future of an Illusion

The Interpretation of Dreams

Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality

Featured Collections

Essays & Speeches

View Collection

The Uncanny

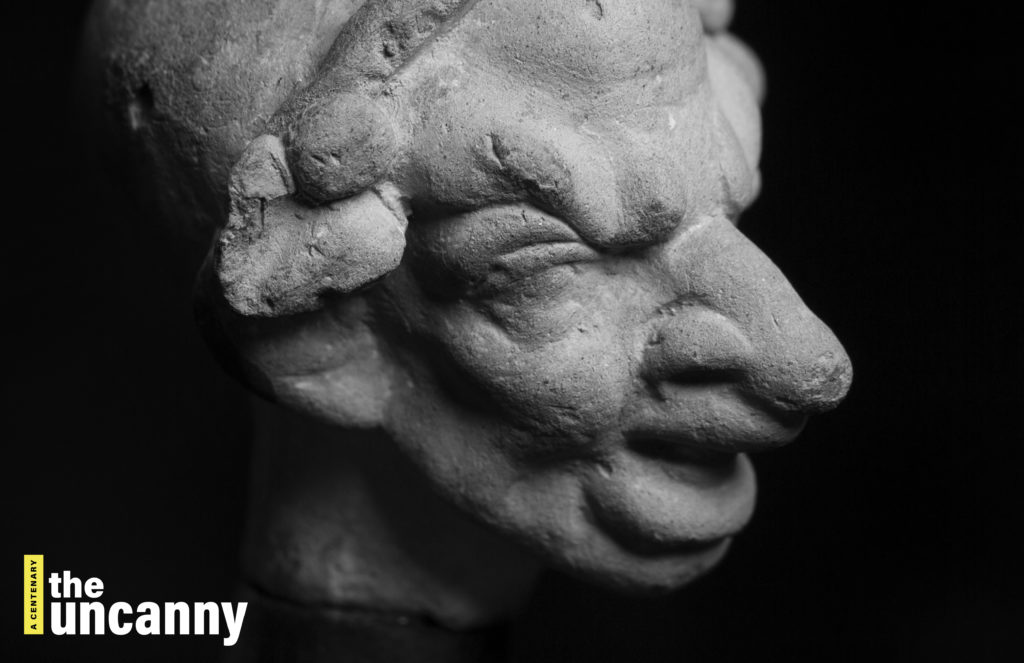

One hundred years ago, sigmund freud wrote his paper on ‘the uncanny’ (das unheimliche). by jamie ruers, one hundred years ago, sigmund freud wrote his paper on ‘ the uncanny ’ (das unheimliche). his theory was rooted in everyday experiences and the aesthetics of popular culture, related to what is frightening, repulsive and distressing..

The paper tackles the horrific concepts of inanimate figures coming to life, severed limbs, ghosts, the image of the double figure (doppelgaengers) and lends itself to art, literature and cinema.

Essay In Two Parts

Freud’s essay is written in two parts. The first part explores the etymology of the words ‘heimlich’ and ‘unheimlich’ (or ‘homely’ and ‘unhomely’, as it directly translates into English), their uses in the German dictionary and how these words are used in other languages. This must have been an unimaginable challenge for the translator!

In the second part, Freud begins to tackle people, things, self-expressions, experiences and situations that best represent the uncanny feeling.

Freud’s paradigm example is the short story of E.T.A. Hoffmann’s ‘The Sandman’ , a tale that parents would tell their children to encourage them to go to sleep. The story goes that the child must be asleep for the Sandman to put sand in the child’s eyes – if they are not asleep, the Sandman will take out their eyes. The protagonist is a boy named Nathaniel whose fate eventually does fall to the Sandman, losing not only his sight but his sanity, then his life. Freud asserts that the removal of the eyes alludes to an infantile fear of castration, but the castration complex is masked by a fear of losing a different sensitive organ: the eyes. This same theme is present in the tragedy of Oedipus.

Doppelgaenger

Freud also touches upon the notion of ‘the double’ or, as it is better known, the doppelgaenger, first explored in the psychoanalytic literature by Otto Rank in 1914. Freud writes that doppelgaengers can be found in:

Mirrors, shadows, guardian spirits, with the belief in the soul and the fear of death. The idea of the eternal soul allows us an energetic denial of the power of death. This was the first double of the body. From having been an assurance of immortality, it becomes the uncanny harbinger of death. (p. 235)

“Uncanny is in reality nothing new or alien, but something which is familiar and old-established in the mind and which has become alienated from it only through the process of repression.” Sigmund Freud

Freud writes:

We can understand why linguistic usage has extended das Heimliche into its opposite, das Unheimliche; for this uncanny is in reality nothing new or alien, but something which is familiar and old-established in the mind and which has become alienated from it only through the process of repression. (p. 241, SE XVII)

Through this process, we can see that the nature of the uncanny is entirely subjective, based upon our own experiences but haunts each of us to varying degrees.

By Jamie Ruers, Freud Museum Researcher

Buy The Uncanny by Sigmund Freud from the museum shop now.

Examples of the Uncanny

The Uncanny in Art

Waxwork dolls, automata, doubles, ghosts, mirrors, the home and its secrets, madness and severed limbs are mentioned throughout The Uncanny, influencing painters and sculptors to explore these themes and blur the boundaries between animate and inanimate, human and non-human, life and death.

Podcast: Freud in Focus 2

Posted in Museum Blog by Jamie Ruers on September 18th, 2019. Tags: The Uncanny

Subscribe to comments | Leave a Comment | Trackback

what is the title of the first piece in the photograph in the blog on the uncanny in your website? (i.e. the sculpture of the life-size man lying down, death). thank you !

It is the Death Mask of the Wolf Man, Sergei Pankejeff.

Hi! Fascinating post! Hoffmann’s ‘The Sandman’ has proven in my experience to be especially good for analysing the familiar yet somewhat unknown presences we might encounter in our lives. What in your opinion are good examples of the Uncanny in literature?

Thanks for your message! My favourite example is The Double by Dostoyevsky. The story begins with the protagonist who finds himself compelled to confront a familiar figure he sees in the distance, who turns out to be himself. This is an unbearable experience and the whole story continues with many twists and turns (I won’t ruin it!). I think it’s not only a good example of doppelgaengers but this is a familiar scene for most people in dreams. This then becomes a nice example of the uncanny nature of dream scenes and nightmares. Do you have any other recommendations yourself, Isabelle?

Does anyone else have a favourite example of the uncanny in literature? Please join in the discussion!

Very interesting subject! Do you have examples of the use of The Uncanny in television shows?

Almost all, if not all, episodes of “The Twilight Zone”. One I would suggest is “The Living Doll”, it features a talking, sentient doll named Talky Tina. I won’t spoil the ending though.

Hi, I’m currently looking at examples of the uncanny in gothic literature, for example its occurrence in the iconography of the haunted house – looking specifically at The Haunting of Hill House. I was wondering, what translation of Freud’s Das Unheimliche do you quote in this article?

Hi Lucy! We use the Standard Editions for quoting Freud. For the full reference: Freud, S., Standard Edition XVII (1917-1919), “On Infantile Neurosis and Other Works” (trans. Strachey, J) You can find the full citation and details here. Hope this helps!

Hi! I am currently writing my dissertation on the psychodynamics of Jacobean Revenge drama and am due to start an MA in Victorian Studies so I have some literary suggestions. Middleton’s Changeling is a great example of ‘doubling’ and the castration anxiety described in the article, especially in reference to eyesight. The Duchess of Malfi by Webster features some very interesting uses of wax work limbs and its very very creepy! The uncanniness of automatons is also used in Decadent literature a lot, especially Rachilde’s Monsieur Venus.

Fascinating information!! To my mind, an excellent example of the uncanny appears in F. Scott Fitzgerald’ s story, “One Trip Abroad.” This story has been particularly admired for Fitzgerald’s effective adaptation of the Doppelgänger device. Obviously, I highly recommend this story. Laura Rinaldi

Hi! This is the most understandable passage about the idea of the uncanny. I’m still reading Freud’s article about the uncanny though, and now i’m on the ‘double’ section. So, i’m writing my undergraduate thesis using the uncanny theory by Freud and taking H.P Lovecraft short stories as the main source for the analysis. Btw, i use 2 of Lovecraft short stories, Whisperer In The Darkness and At The Mountain of Madness which i think it would be good using this theory since the whole idea of the uncanny is ‘all that is terrible, arouses dread and creeping horror, whatever excites dread.’ So, do you think that most of Lovecraft works (especially those two short stories) are suitable for “the characteristics” of the uncanny? And if you were me, how would you analyze a literary work using the uncanny theory?

Thanks in advance!

What about the story of ‘the Nutcracker’ then? That is about toys and other objects coming alive!

Hi Gerda. That is a great question! The modern popularised versions of the Nutcracker (Tchaikovsky’s ballet or TV/Films adaptations) are in fact watered down versions of the original tale! Interestingly, the original ‘Nutcracker’ was written by E.T.A. Hoffmann, who also wrote ‘The Sandman’ which Freud analyses in his Uncanny essay. The original story was actually rather uncanny full of references to death and castration; mice have their tails chopped off and the dolls come alive when the protagonist, a little girl named Marie, cuts her arm and begins to have fever dreams from the blood loss (perhaps this is an allegory for the loss of her childhood…?). Throughout, Marie finds it difficult to differentiate between her fever dreams and reality. The story ends with one paragraph – sorry, a spoiler here – as Marie falls in love with the Nutcracker and goes to live with him in the Marzipan Kingdom forever. I’m sure wonderful papers have been written about why Marie stayed in the fantasy world 🙂

This is a welcome set of posts and comments. It seems to me that we are about to engage with the uncanny in the way the Freud would have hoped – facing the call to all embrace the reality of the all the things our “developed” judeo-christian-informed academic circles have rendered superstition and unscientific. Some hypotheses and questions arise for me. This could be a time of awakening for organisations, individuals and society at large, as we turn and face the emergence of the unconscious in the age of AI. The Chthonic turn, the hermetic gaze and the masonic philosophical position will have to find a new home side by side with the Judeo-Christian world view. It may also be seen as an ancestral healing of the legacy of the various Inquisitions led by the Vatican in centuries past that wiped out epistemologies rooted to the earth and non-human ways of Being. May open a new perspective on climate peril, collapsing democracies and a host of other discontents of our (un)civilisation. Lots of questions…..

Leave a Comment

Your email is never published nor shared. Required fields are marked *

Latest Posts

- Freud and his soul-searching antiquities

- What is Your 'Acropolis'?

- Freudian Wisdom for the Times of Turmoil

- The Body Image Project

- Psychoanalysis with Children: a Brief Journey

Sigmund Freud Library Conservation Appeal

Please help preserve the library that shaped the creation of the ‘talking cure’.

Current exhibition

Freud and Latin America

An exciting exploration of the impact that Freud had on culture, society, art, and psychoanalysis in Latin America.

What’s On

Online. On Demand. Events, courses and conferences. All available worldwide.

Plan your visit

Plan your visit to the Freud Museum: opening times, directions and admission fees.

Newsletter Signup

Be the first to hear about our events, exhibitions and other activities.

Oxford University Press's Academic Insights for the Thinking World

Explaining Freud’s concept of the uncanny

British Journal of Aesthetics

Founded in 1960, the British Journal of Aesthetics is highly regarded as an international forum for debate in philosophical aesthetics and the philosophy of art. The Journal is published to promote the study and discussion of philosophical questions about aesthetic experience and the arts.

- By Mark Windsor

- April 17 th 2019

According to his friend and biographer Ernest Jones, Sigmund Freud was fond regaling him with “strange or uncanny experiences with patients.” Freud had a “particular relish” for such stories.

2019 marks the centenary of the publication of Freud’s essay, “The ‘Uncanny”. Although much has been written on the essay during that time, Freud’s concept of the uncanny is often not well understood. Typically, Freud’s theory of the uncanny is referred to under the heading of “the return of the repressed.” But Freud also offered another, more often overlooked, explanation for why we experience certain phenomena as uncanny. This has to do with the apparent confirmation of “surmounted primitive beliefs.”

According to this theory, we all inherit, both from our individual and collective pasts, certain beliefs in animistic and magical phenomena—such as belief in the existence of spirits—which most of us, Freud thought, have largely, but not totally, surmounted. “As soon as something actually happens in our lives,” Freud wrote, which seems to confirm a surmounted primitive belief, we get a feeling of the uncanny. Not only must the phenomenon be experienced as taking place in reality, however, it must also bring about uncertainty about what is real. As Freud put it, the phenomenon must bring about “a conflict of judgement as to whether things which been ‘surmounted’ and are regarded as incredible may not, after all, be possible.”

Consider some examples. Apparent acts of telepathy and precognition can appear to confirm belief in the omnipotence of thoughts. Waxworks and other highly lifelike human figures can appear to affirm belief in animism—the doctrine that everything is imbued with a living soul.

A remarkable illustration of Freud’s theory can be found in Carl Jung’s autobiography . In 1909, during a meeting between Jung and Freud, Jung “had a curious sensation,” as if his “diaphragm were made of iron and were becoming red-hot—a glowing vault.” “And at that moment,” Jung wrote, there was such a “loud report” that came from the bookcase that was standing next to them that he and Freud “started up in alarm, fearing the thing was going to topple over.” Jung said to Freud: “There, that is an example of a so-called catalytic exteriorization phenomenon.” “Oh come,’” Freud replied. “That is sheer bosh.” “You are mistaken, Herr Professor,” said Jung. “And to prove my point, I now predict that in a moment there will be another such loud report!” Jung wrote that no sooner had said these words “than the same detonation went off in the bookcase.”

“To this day I do not know what gave me this certainty.” Jung wrote. “But I knew beyond all doubt that the report would come again. Freud only stared aghast at me.”

Following the incident, Freud wrote a letter to Jung advising him to keep a “cool head.” Freud was first inclined “to ascribe some meaning” to the noise. But he subsequently made some investigations, and numerous times had observed the same noise coming from the bookcase, yet never in connection with his thoughts. “My credulity,” Freud wrote, “or at least my readiness to believe, vanished along with the spell of your personal presence.”

Freud’s theory of surmounted primitive beliefs provides an explanation for why Freud experienced the sounding bookcase uncanny. It also provides an explanation for why the event had a different effect on Jung. For Freud causal connection between Jung’s thoughts and the noise was impossible. For Jung, it merely affirmed his belief in the reality of the “catalytic exteriorization phenomenon.”

Can this theory of Freud’s be used to explain all uncanny phenomena? This does not seem likely. For a start, one may have qualms about Freud’s characterisation of primitive beliefs. It also does not seem plausible that in order to experience something as uncanny one must first have held and then surmounted a belief in its reality. What if I had never believed in the existence of ghosts, does that mean I cannot experience a ghost-like apparition as uncanny?

Can these problems with Freud’s theory be overcome? That is a task for another occasion.

Featured image credit: “Early morning in NZ” by Tobias Tullius. Public domain via Unsplash .

Mark Windsor holds a PhD in history and philosophy of art from the University of Kent, and is currently employed as a lecturer in aesthetics at the New College of the Humanities. He has articles published or forthcoming in the British Journal of Aesthetics , Philosophy and Literature , Estetika , and Tate Papers .

His article, ' What is the Uncanny? ', was included in the 2018 Best of Philosophy collection .

- Arts & Humanities

- Psychology & Neuroscience

Our Privacy Policy sets out how Oxford University Press handles your personal information, and your rights to object to your personal information being used for marketing to you or being processed as part of our business activities.

We will only use your personal information to register you for OUPblog articles.

Or subscribe to articles in the subject area by email or RSS

Related posts:

Recent Comments

So what is your main argument? Like what are you trying to say?

Comments are closed.

School of Writing, Literature, and Film

- BA in English

- BA in Creative Writing

- About Film Studies

- Film Faculty

- Minor in Film Studies

- Film Studies at Work

- Minor in English

- Minor in Writing

- Minor in Applied Journalism

- Scientific, Technical, and Professional Communication Certificate

- Academic Advising

- Student Resources

- Scholarships

- MA in English

- MFA in Creative Writing

- Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies (MAIS)

- Low Residency MFA in Creative Writing

- Undergraduate Course Descriptions

- Graduate Course Descriptions

- Faculty & Staff Directory

- Faculty by Fields of Focus

- Promoting Your Research

- 2024 Spring Newsletter

- Commitment to DEI

- Twitter News Feed

- 2022 Spring Newsletter

- OSU - University of Warsaw Faculty Exchange Program

- SWLF Media Channel

- Student Work

- View All Events

- The Stone Award

- Conference for Antiracist Teaching, Language and Assessment

- Continuing Education

- Alumni Notes

- Featured Alumni

- Donor Information

- Support SWLF

The CLA websites are currently under construction and may not reflect the most current information until the end of the Fall Term.

What is the Uncanny? || Definition & Examples

"what is the uncanny": a literary guide for english students and teachers.

View the full series: The Oregon State Guide to English Literary Terms

- Guide to Literary Terms

- BA in English Degree

- BA in Creative Writing Degree

- Oregon State Admissions Info

What is the Uncanny? Transcript (Spanish and English Subtitles Available in Video. Click HERE for the Spanish Transcript)

By Ray Malewitz , Oregon State University Associate Professor of American Literature

4 August 2020

What scares us? What keeps us up at night after we watch a horror movie or has us rushing to lock our doors after reading a scary novel? If we run through a catalog of stock horror characters, we might come up with an easy and obvious answer to this question: we are afraid of things and people we don’t understand.

We all can probably agree that the creatures in the Ridley Scott movie Alien are terrifying, and this is largely due to the fact that they don’t look or act like us (they pop out of our stomachs, after all!)

This tendency to view “alien” others as evil or frightening is, of course, often itself evil and frightening, as countless stories from history and literature remind us. But this depressing tendency isn’t what I want to get into today.

Instead, I want to discuss a different (and, to my mind, more interesting) kind of fear, one that is generated by things that are NOT unfamiliar to us. I’m thinking here of things that have been with us since our childhoods, like dolls, for example, or clowns, or televisions. What is it about these old familiar things that, under certain circumstances, raises the hair on the backs of our necks?

uncanny_image_clowns.jpg

Sigmund Freud takes up this question in a 1919 essay “The Uncanny,” and his thoughts on the subject are still useful 100 years later. In this lesson, I want to sketch out his definition of this special kind of fear and then show you how you might apply it to your own readings of literature.

Freud begins his essay with a strange observation. The word for uncanny in Freud’s native language of German is “unheimlich,” which means not from the home. In other words, not familiar. This definition seems to repeat what I just said about alien others—we fear that which is not from the home. But Freud also notes that unheimlich (or uncanny) has, in certain situations, been used to mean something hidden inside the home that was never meant to come to light.

This is very strange, as it suggests that the meaning of unheimlich and heimlich, or uncanny and canny, overlap. Like the word buckle, which can mean to break apart or to come together, uncanny thus means itself and its opposite at the same time. Weird, right?

To resolve this paradox, Freud turns to his general theory of the self and asks what might be hidden within us that suddenly comes to light and frightens us. As you may already know, Freud was absolutely obsessed with changes that take place in our minds as we move from childhood to adulthood. When we are children, Freud suggests, we are fiercely devoted to our mothers, because they nurture and protect us. Anything or anyone who gets in the way of this devotional love becomes, in our irrational baby minds, a threat that should be eliminated—even if that threat happens to be our father.

What I’ve just described is a version of Freud’s famous Oedipus complex, in which a male child, echoing the actions of the tragic Greek king Oedipus, wants to kill his father and marry his mother. Freud isn’t suggesting that our adult rational selves want to carry out these actions—Oedipus, after all, is so horrified by his actions that he blinds himself when he discovers what he has done. Instead Freud is suggesting that the self we once were as a child still remains within us, hidden underneath our new rational, adult self.

And sometimes, like the alien in Scott’s movies, that hidden self pops out. As he writes, “Nowadays we no longer believe [in childish fantasies], we have surmounted such ways of thought; but we do not feel quite sure of our new set of beliefs, and the old ones still exist within us ready to seize upon any confirmation” (241).

So now we’re getting somewhere! The uncanny seems to be related to beliefs we once held when we were children that we’ve repressed or covered over or hidden away to become adults. We cover over these beliefs because, of course, those beliefs are wrong and we don’t want to be wrong. We want to be grown up. We want to be rational people with proper attitudes about the world. (Clowns aren’t scary, Ray, stop behaving like a child!)

And this process of maturation, of giving up our childish things, takes a lot of time and effort on our part. It would be absolutely horrifying to imagine, as adults, that our child-self had a better understanding of the world than we do. This, for Freud, is the uncanny—it is the dread we feel in situations in which our childish fantasies and fears appear more real and more true than our adult worldviews.

If we have this idea in mind, the difference between familiar things that delight us and familiar things that terrify us start to make sense. In the movie Toy Story, the talking dolls on screen are funny and sympathetic characters because they are written within a genre that makes it ok for them to come to life. I don’t go to a Pixar movie and expect reality. In the realist setting of horror, however, those same dolls become terrifying to adult audiences.

uncanny_dora.jpg

Along similar lines, if I were a child, I might imagine, say, Dora the Explorer as someone who is actually inside of my tv asking me for advice on her travels. As an adult, well, that would also be pure terror (right? You—right there, yes, I’m talking to you!)

uncanny_the_ring.jpg

Both of these examples suggest one final necessary property of the uncanny—realism. Fairy tales and children’s cartoons cannot be uncanny, because those genres never ask us to believe that what we are watching relates in any way to our reality. “The situation is altered,” Freud writes, “as soon as the writer pretends to move in the world of common reality… He takes advantage, as it were, of our supposedly surmounted [or overcome] superstitious-ness; he deceives us into thinking that he is giving us the sober truth, and then after all oversteps the bounds of possibility.”

Freud’s phrasing might sound confusing, so let’s clear it up with a simple example. Here’s one from the opening to Edgar Allan Poe’s famous poem, “The Raven.”

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore,

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.

”’Tis some visitor,” I muttered, “tapping at my chamber door—

Only this, and nothing more.”

It is, of course, terrifying to hear an unexpected knock at your door at midnight. It would be even more terrifying and uncanny if your significant other, Lenore, had just died and you were saddled with immense grief, as we later discover is the case with Poe’s speaker. The knocking might remind you of strange noises you heard at night when you were a child that you thought were ghosts or demons. Or it might encourage you to imagine that Lenore could return from the dead, even though your rational self knows that is impossible.

The speaker considers both uncanny scenarios after a mysterious talking raven appears, which leads the speaker to descend into madness. But before any of this happens, (and before the uncanny can therefore operate), Poe’s poem must “pretend to move in the world of common reality.” Poe does this by having his speaker insist that there is a rational explanation for the tapping. It is a visitor, he mutters to himself, “Only this, and nothing more.” In other words, Poe and his speaker here are insisting that he (and the readers along for the ride) have no cause for concern—there is a perfectly rational explanation for the strange noise at his door.

Even after the raven appears and starts squawking “Nevermore,” the speaker still maintains his faith in his rationality:

“Doubtless,” said I, “what it utters is its only stock and store

Caught from some unhappy master whom unmerciful Disaster

Followed fast and followed faster till his songs one burden bore—

Till the dirges of his Hopes that melancholy burden bore

Of ‘Never—nevermore.”

I won’t go any further into an interpretation of this poem, other than to say that Freud’s model works quite well within it. If you have any thoughts on how the analysis could proceed, I hope you’ll share them in the comments section in the video. You could also, incidentally, consider how the uncanny might work in the first example I mentioned at the start of this video—the Alien movie—in which what appears on the surface to be wholly unfamiliar phenomena—aliens bursting out of bodies, for example—might actually, with a bit of thought, be understood as events our child selves were quite familiar with. And our mothers, too.

Freudian readings of literature are obviously old and problematic in a variety of ways, and they need to be reworked for the 21 st century. But as his theory of the uncanny itself suggests, leaving Freud’s ideas behind or covering them over carries its own risks, too. Reading his theory and making it relevant for our very different times can help us to gain a better insight into what we fear and, more importantly, what that fear can tell us about who we are.

Want to cite this?

MLA Citation: Malewitz, Raymond. "What is the Uncanny?" Oregon State Guide to English Literary Terms, 4 Aug. 2020, Oregon State University, https://liberalarts.oregonstate.edu/wlf/what-uncanny. Accessed [insert date].

Further Resources for Teachers

The uncanny can contribute to a variety of discussions of popular Gothic short stories, including Poe's "Ligeia" and "Fall of the House of Usher" and Henry James's novella The Turn of the Screw.

Interested in more video lessons? View the full series:

The oregon state guide to english literary terms, contact info.

Email: [email protected]

College of Liberal Arts Student Services 214 Bexell Hall 541-737-0561

Deans Office 200 Bexell Hall 541-737-4582

Corvallis, OR 97331-8600

liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu liberalartsosu CLA LinkedIn

- Dean's Office

- Faculty & Staff Resources

- Research Support

- Featured Stories

- Undergraduate Students

- Transfer Students

- Graduate Students

- Career Services

- Internships

- Financial Aid

- Honors Student Profiles

- Degrees and Programs

- Centers and Initiatives

- School of Communication

- School of History, Philosophy and Religion

- School of Language, Culture and Society

- School of Psychological Science

- School of Public Policy

- School of Visual, Performing and Design Arts

- School of Writing, Literature and Film

- Give to CLA

The Uncanny

Cite this chapter.

- Allan Gardner Lloyd-Smith 2

99 Accesses

Freud’s exploration of the uncanny in his essay of 1919, ‘Das Unheimliche’, remains the single most influential source of thought about this elusive topic. His starting point is an examination of the etymology of the German word unheimlich , which shows that the uncanny is ‘that class of the frightening which leads back to what is known of old and long familiar’ (p. 220). 1 Heimlich means belonging to the house, not strange, familiar, tame, intimate, friendly, etc. It also, however, can mean concealed, kept from sight, or withheld from others. The implication of secrecy within an apparently open and friendly term is intensified by the addition of ‘un’ to produce a term for the eerie and frightening, which finally leads Freud to Schelling’s definition of the uncanny: ‘ “Unheimlich” is the name for everything that ought to have remained … secret and hidden but has come to light ’ (Freud’s italics). Similarly in English, the Oxford English Dictionary shows canny to mean not only ‘cosy’ but also ‘endowed with occult or magical powers’.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Sigmund Freud, ‘Das Unheimliche [The Uncanny]’ (1919), Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works 24 vols, ed. and trans. James Strachey (London: The Hogarth Press, 1953) vol. 17, pp. 217–52.

Google Scholar

David I. Grossvogel, Mystery and its Fictions (Baltimore, Md, and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979).

Hélène Cixous, ‘Fiction and its Phantoms’, New Literary History , 7 (1975) pp. 525–48.

Georges Poulet, ‘Phenomenology of Reading’, New Literary History , 1 (1969) pp. 53–68.

Article Google Scholar

Wolfgang Iser, ‘The Reality of Fiction: a Functionalist Approach to Literature’, New Literary History , 7 (1975) p. 20

Tzvetan Todorov, The Poetics of Prose , trans. Richard Howard (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1977) p. 145.

Pierre Macherey, A Theory of Literary Production , trans. Geoffrey Wall (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978) p. 19.

Wolfgang Iser, The Act of Reading (1976; London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978) pp. 228, 229.

Tzvetan Todorov, The Fantastic (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1975) p. 168.

Henry James Sr, Substance and Shadow , in F. O. Matthiessen (ed.), The James Family (New York: Knopf, 1961) p. 165.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of East Anglia, UK

Allan Gardner Lloyd-Smith ( Lecturer in American Literature )

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Copyright information

© 1989 Allan Gardner Lloyd-Smith

About this chapter

Lloyd-Smith, A.G. (1989). The Uncanny. In: Uncanny American Fiction. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-19754-5_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-19754-5_1

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN : 978-1-349-19756-9

Online ISBN : 978-1-349-19754-5

eBook Packages : Palgrave Literature & Performing Arts Collection Literature, Cultural and Media Studies (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Freud The Uncanny Summary

Summary & analysis of the uncanny by sigmund freud.

In Sigmund Freud’s seminal essay “The Uncanny,” he delves into the enigmatic concept of the uncanny and its profound impact on human psychology and literature. Freud’s exploration revolves around the uncanny as a state of simultaneous familiarity and unfamiliarity, which engenders a sense of discomfort and unease within individuals.

The Uncanny | Summary

Within each section, Freud provides a comprehensive analysis of the theme at hand. He draws on psychoanalytic concepts, case studies, literary examples, and his own observations to support his arguments. Freud’s writing style is characterized by a precise and analytical approach , employing intricate vocabulary and theoretical frameworks to elucidate his points.

Throughout the essay, Freud demonstrates a logical progression from one argument to the next, showing the interconnectedness of the various themes. He links the fear of death to the presence of doubles, highlighting how the uncanny emerges from the disruption of identity boundaries. He also connects the uncanny to the workings of the unconscious, emphasizing how repressed desires can resurface and contribute to the uncanny experience.

Towards the end of the essay, Freud concludes his exploration of the uncanny by summarizing the key points made and reflecting on the broader implications of his findings. He offers insights into the psychological and artistic significance of the uncanny and its impact on human experience.

Freud also explores the concept of the double or doppelgänger as a manifestation of the uncanny. The presence of a doppelgänger, a replica of oneself, disrupts the distinction between self and other. This blurring of identity engenders a feeling of eeriness and unease. The uncanny nature of the double arises from its ability to evoke anxieties related to identity dissolution and the disintegration of the self .

The Uncanny, Section 1 | Analysis

In the opening section of Freud’s essay, he provides a succinct overview of his hypothesis , which centers on the existence of a distinct psychological phenomenon known as the “uncanny.” Freud posits that this uncanny feeling is characterized by a sense of unease and discomfort, differentiating it from conventional fear. It arises when something once familiar reemerges unexpectedly and imposes itself upon us in an unwelcome manner.

Implicitly assuming the reader’s familiarity with key psychoanalytic concepts, Freud’s initial exposition can be initially daunting for novices to his work. Nevertheless, this section offers valuable insights into Freud’s assumptions and methodological approach , particularly regarding the application of psychoanalysis to cultural and artistic phenomena.

This perspective on art aligns with Freud’s utilization of language and linguistics as a means to elucidate shared cultural beliefs. Freud contends that seemingly innocuous phrases often harbor meanings and connections between ideas or emotions that once resided in our minds but now lie dormant—latent and yet undeniably present. Here, a linguistic analysis unveils the intricate interplay between the word “unheimlich,” meaning uncanny, and its antithesis, “heimlich,” denoting familiarity, relatedness to the home, and simultaneously, secrecy and danger. German speakers employ these words instinctively, without pondering their connection, as they intuitively grasp the emotional resonance and interconnectedness between them.

This rhetorical strategy mirrors Freud’s psychoanalytic writings, which frequently blur the demarcation between “neurotic” cases and the human condition at large, as well as the line between health and illness. Freud adeptly veils whether his observations exclusively pertain to the “ morbidly anxious ” or “neurotic” individuals, or if they encompass psychic processes experienced universally by all human beings. In a similar vein, Freud coyly claims immunity to the uncanny while relying on his own experiences as evidential support.

The Uncanny, Section 2 | Analysis

Freud demonstrates his mastery of psychoanalysis by weaving together elements from existing theories while offering his unique insights. While borrowing Jentsch’s concept of the uncanny and embracing Schelling’s notion of the return of the hidden, Freud goes beyond these perspectives to delve into the depths of his own psychoanalytic practice. He reveals that the roots of the uncanny lie in the recesses of our memories, desires, and fears —traces from infancy or earlier stages of human existence that have been repressed or overcome.

As Freud’s argument unfolds, readers may initially find his conclusions challenging to accept. However, it is worth noting that his analysis of E.T.A. Hoffmann’s “The Sand-Man” has been widely regarded as definitive. Freud perceptively dissects the intricate interplay between the story’s familial dynamics and the unsettling Olympia episode, elucidating how Nathaniel’s narcissistic love for a character devoid of personality encapsulates the traumatic experiences of his past. He suggests that Hoffmann may have been driven by personal experiences to craft a chilling tale or to intentionally employ the uncanny as a narrative device.

The Uncanny, Section 3 | Analysis

Freud proposes that the primary source of the uncanny in literature is the presence of repressed desires and fears within the reader’s own unconscious. He argues that works of fiction serve as powerful stimuli that awaken these latent emotions, thereby eliciting a response that is both unsettling and captivating. By unraveling the underlying psychological mechanisms at play, Freud provides valuable insights into the intricate dynamics between the artist, the work, and the audience. He highlights the motif of the “double,” where characters encounter their doppelgängers or encounter mirrored versions of themselves. The concept of the double triggers an unsettling sensation, as it challenges the stability of identity and blurs the boundaries between the self and the other.

Freud’s analysis underscores the transformative potential of art . He argues that literature, through its evocation of the uncanny, provides a means for individuals to confront their deepest fears and desires in a controlled and symbolic manner. In this way, the uncanny becomes a vehicle for catharsis and self-discovery , allowing individuals to grapple with their innermost conflicts and anxieties.

The uncanny

A concept in art associated with psychologist Sigmund Freud which describes a strange and anxious feeling sometimes created by familiar objects in unfamilar contexts

The term was first used by German psychiatrist Ernst Jentsch in his essay On the Psychology of the Uncanny , 1906. Jentsch describes the uncanny – in German ‘unheimlich’ (unhomely) – as something new and unknown that can often be seen as negative at first.

Sigmund Freud's essay The Uncanny (1919) however repositioned the idea as the instance when something can be familiar and yet alien at the same time. He suggested that ‘unheimlich’ was specifically in opposition to ‘heimlich’, which can mean homely and familiar but also secret and concealed or private. ‘Unheimlich’ therefore was not just unknown, but also, he argued, bringing out something that was hidden or repressed. He called it 'that class of frightening which leads back to what is known of old and long familiar.'

Artists, including some associated with the surrealist movement drew on this description and made artworks that combined familiar things in unexpected ways to create uncanny feelings.

Now, the term 'uncanny valley' is also applied to artworks and animation or video games that that reproduce places and people so closely that they create a similar eerie feeling.

Does this text contain inaccurate information or language that you feel we should improve or change? We would like to hear from you.

RELATED TERMS AND CONCEPTS

A twentieth-century literary, philosophical and artistic movement that explored the workings of the mind, championing the irrational, the poetic and the revolutionary

Abject art is used to describe artworks which explore themes that transgress and threaten our sense of cleanliness and propriety particularly referencing the body and bodily functions

EXPLORE THIS TERM

I've got this strange feeling....

Mike Kelley and Jeffrey Sconce

Following Mike Kelley’s exhibition The Uncanny at Tate Liverpool, the artist and Jeffrey Sconce talk about Freud, the power of hidden memory and techno-shamanism

Mike Nelson in conversation

Clarrie Wallis

To coincide with Mike Nelson representing Britain at the 54th Venice Biennale of Art, Tate curator Clarrie Wallis talks to the artist about his extraordinary installation The Coral Reef , currently on display at Tate Britain

Biopolitical Effigies: The Volatile Life-Cast in the Work of Paul Thek and Lynn Hershman Leeson

Milena Tomic

In the late 1960s and early 1970s American artists Paul Thek and Lynn Hershman Leeson independently created wax effigies and situated them within immersive or performative contexts that transformed the visual language of sovereignty and dignified the socially marginal body. This paper explores lost installations by both artists, where the effigy’s connotations of volatility challenged biopolitical systems of control as well as the reduction of individuals to stereotypes.

Selected artworks in the collection

Lobster telephone, beverly edmier 1967, the uncanny at tate, mike kelley: the uncanny.

Mike Kelley: The Uncanny, Tate Modern

PhotoBook Journal

The Contemporary Photobook Magazine

Leonard Pongo – The Uncanny

Review by Steve Harp •

… pictures have an uncanny ability of suggesting that there is another world…They represent a sense of otherness. The figures in photographs have been muted, and they stare out at you as if they are asking for a chance to say something. – W.G. Sebald

The concept of the “uncanny,” which Sigmund Freud investigates in his 1919 essay of the same name, can, at its simplest, be described as that which is seemingly most familiar yet, upon closer consideration, is revealed as actually the most unfamiliar . The example Freud gives and structures the first third of his essay around is the concept of home and the homely ( heimlich ). Tracing various definitions and uses of the term heimlich , he concludes this opening section by stating:

Thus, heimlich is a word the meaning of which develops in the direction of ambivalence until it finally coincides with its opposite, unheimlich .

In other words, in order to experience something as uncanny, it must be simultaneously familiar, “homelike,” yet at the same time unfamiliar and unsettlingly strange. The term “uncanny” is one of a litany of words which in general usage, often bear only a fleeting or tangential connection to the original concept or meaning (see: surreal )…

So it was with great interest that I began my encounter with Leonard Pongo’s 2023 monograph, The Uncanny. My review copy is a softcover, 6.5” x 8.5.” The wrap-around cover depicts what looks to be a field of weeds against a night sky. We don’t see the ground the weeds spring from. In fact, the plants themselves don’t seem to be illuminated so much as…strangely glistening or shimmering silver objects. The only text, along the spine, is also in silver. Opening the book, the front and back cover flaps extend the mysterious field into a true panorama, 24” x 8.5.” Moving into the book, we’re initially confronted by four photographs of black Africans, residents of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (these specifics we learn only later) before the title page, which is white text on black background.

The images seem to meld together in an ambiguous and opaque darkness. This motif continues throughout the 111 images in the book, the photographs mostly being presented as either double page full bleeds or single page full bleeds. Where there are borders, they are in black. The photographs – almost all shot in dark interior spaces or at night – seem to run together to create a cryptic “dream world” of scenes and situations familiar to the participants but irrevocably strange to the viewer.

Pongo’s visual description or representation of this place is unrelenting. Mysterious spaces, often presented with enigmatic choices of focus are juxtaposed with – and often contain – moments of great emotion, sometimes between subjects and sometimes displayed by the sole figure within the frame. The images in The Uncanny are visually gripping and compelling, scenes from a narrative that seems not simply understood, but entirely strange, foreign, unheimlich . This foreignness stems partly (as mentioned above) from the darkness and opacity of the images and their presentation, but also from the resolute lack of textual information given to orient the viewer. Until we reach the critical essay by Nadia Yala Kisukidi at the end of the volume, the only language given us (other than the title) is the language displayed within the images themselves. Words on clothes, signs, banners, product wrappers, graffiti; words in French, English and, in the case of the graffiti, an unidentifiable vernacular or patois.

A consideration of the biographical information found on Pongo’s website and the publisher’s home site for this book illuminates to a certain extent the uncanniness of these photographs and this project. We find that Pongo (of Congolese heritage) was born and grew up in Belgium. The photographs herein, then, might be seen as an attempt to “return” to a place not previously lived in, a place thought of in some sense as “home,” yet anything but “homelike.” No essentialist “return” depicted here, but instead, as Freud noted, the notion of home or homelike “develops in the direction of ambivalence until it finally coincides with its opposite.” In considering the fact of Pongo, a black man of Congolese heritage being born in and growing up in Europe, specifically Belgium, I was reminded of the history and horrors of Belgian colonialism in Africa (so shatteringly described in in Sven Lindqvist’s travelog/history, Exterminate All the Brutes [1997]). And was then reminded as well of the complex and always multifaceted aspects of identity. As Edward Said writes at the conclusion of Culture and Imperialism (1994):

No one today is purely one thing. Labels like Indian, or woman, or Muslim, or American are not more than starting points, which if followed into actual experience for only a moment are quickly left behind.

While The Uncanny speaks powerfully as a political and geographic visual exploration and depiction of the Democratic Republic of the Congo in the early 21 st century, it speaks even more forcefully – and movingly – as a psychological journey. The complexities of what is seen and what is understood is reflected on eloquently – indeed poetically – in the concluding essay, “There are no roads. Not even a body. Nor even a glance.” writes the French philosopher Nadia Yala Kisukidi. Here, in her brief discussion of Pongo’s work, Kisukidi remarks on how these “pictures stubbornly refuse to show,” how the “photographs produce ‘something else.’ “She sees Pongo’s images as presenting the “uncanny strangeness of an intimate, familiar world which, by refusing to be named escapes…each of the images unveils its possibility as a secret.”

I find this haunting book to be one of the most powerful and challenging collections of photographs I’ve encountered in a long time. Demanding, unsettling, unrelentingly strange , we might conclude by returning (since the notion of returns is, after all, so central here) to Freud’s essay. At the conclusion of his essay, Freud suggests three factors as at the heart of the uncanny: silence, solitude and darkness. No three words better describe Pongo’s singularly powerful photographs and book.

Steve Harp is a Contributing Editor and Associate Professor The Art School, DePaul University

The Uncanny, Leonard Pongo.

Photographer: Leonard Pongo ; born in Liege, Belgium and currently resides in Belgium and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Publisher: Gost Books , London, copyright 2023

Text by Nadia Yala Kisukidi.

Text: English and French.

Book description: Hardcover with clothbound cover. Printed in Italy by EBS.

Book designed and edited by GOST: Rossella Castello, Katie Clifford, Gemma Gerhard, Justine Hucker, Allon Kaye, Eleanor Macnair, Claudia Paladini, Ana Rocha.

Articles & photographs published on PhotoBook Journal may not be reproduced without the permission of the PhotoBook Journal staff sand the photographer(s).

Share this:

Leave a comment cancel reply.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Artist Books

- Book Publications

- Book Reviews

- exhibitions

- Photo Book Discussions

- Photo Book NEWS

- Photo Book Stores

- Photo Books

- Photographers

- Uncategorized

Website Powered by WordPress.com .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

The Uncanny

By sigmund freud, the uncanny essay questions.

In what ways is Freud's The Uncanny a typical artistic study, and in what ways is it atypical?

Freud's Uncanny is a typical study in that it contains a close reading of a well-known work of art, in this case, Hoffmann's "Sand-Man," and offers an interpretation of it, parsing the author's intentions, and examining how it achieves its effects. It takes these conclusions and makes some hypotheses about art and how art functions. Freud's reading suggests that art serves as a repository for the fears and wishes of infancy and of human pre-history, which, because they have been repressed or overcome, cannot be directly expressed and find symbolic expression in art. Freud's study is atypical in several ways, however. First, Freud does not come to literature as a student of art, but rather with a pre-made methodology and anthropology—that of psychoanalysis—which he wants to extend to art. Second, Freud does not focus on art's positive aspects, like beauty or grandeur, but rather on a single negative effect, that of anxiety or discomfort, that is usually used by artworks looked down upon as "popular," e.g., horror. And finally, Freud is less concerned with art itself than the structures of the mind that allow artistic effects to be possible.

Reconstruct Freud's linguistic analysis of the word unheimlich , or "uncanny." In light of the literary analysis, why do you think Freud relies on this dictionary definition?

Freud demonstrates that the word unheimlich is actually one of the meanings of its antonym, heimlich . Heimlich can be used to refer to anything that is familiar or cozy. It also refers to anything of or relating to the home, as in a family friend, or, in politics, a privy councilor, someone who advises a monarch on domestic affairs. It can mean something that is tame, in the sense of a domestic plant or animal. It also refers to the sense of safety that comes with being concealed or tucked away. From this latter meaning, Freud is able to extract a range of meanings that contradict the previous ones. Heimlich can mean "secret," or mysterious, and from there it also has a range of usages that connote the unknown, or danger, like "hidden" knowledge. Freud concludes that the word unheimlich contains in itself two opposite meanings: that of the familiar and the frightening. Freud's treatment of language runs parallel to his treatment of literature. He sees language as a repository for common cultural assumptions that all people find intuitively and emotionally familiar. By exploring linguistic usage, Freud believes that we can get to the origin of these assumptions.

Summarize Freud's reading of E.T.A. Hoffmann's "The Sand-Man." Consider the pros and cons of his reading.

In Freud's reading of "The Sand-Man," Nathaniel suffers from an un-worked-through castration complex. As a child, he has ambivalent feelings towards his father, as a possible castrator who interferes with his capacity for pleasure, and also as his defender and a source of love. Nathaniel splits these ambivalent feelings into two father figures: the Sand-Man/Coppola and his actual father. He believes the Sand-Man murdered his father because he transfers his own wish to kill his father onto the menacing figure. The fear of castration is attached to his obsession with the loss of his eyes. As an adult, he falls in love with the doll Olympia because she is the ideal screen for his infant narcissism, which he has not worked through as a result of his trauma. His narcissism causes him to recognize in her his own feminine stance towards his father. Once again, the Sand-Man returns as a castrating figure who separates him from Olympia, in the guise of the eye-glass merchant Coppola.

Freud's reading of "The Sand-Man" has the advantage of linking the childhood episode and the Olympia-automaton episode. Though Freud acknowledges the satirical tone with which Hoffmann treats the Olympia episode, Freud doesn't address whether this substantively changes the "uncanny" aspect of it. Freud also overlooks the role played by technology in Hoffmann. Freud does not address the role of optical media and scientific measurements, and the frightening technological progress that allows Professor Spalanzani to create Olympia.

Choose three instances of the uncanny and summarize Freud's explanation for them.

Freud believes that the fear of loss of one's eyes, or of damage done to one's eyes, has its roots in the childhood fear of castration. When male infants develop a sexuality they soon begin believing that their father will castrate them to eliminate sexual competition for their mother. Freud believes that the fear of losing one's eyes is a manifestation of this fear, which has been repressed as the ego develops. Freud believes that the uncanny feeling generated by two doubles—people who look exactly alike—comes from infant narcissism, and the narcissism of primitive humanity. Primitive people, like the Ancient Egyptians, believed that the double was insurance against death, and preserved the individual. Later, the double came to embody the conscience, or a critical faculty of self-reflection. Both of these earlier beliefs have been repressed. Freud believes that fear of living dolls is a recurrence of the belief that inanimate objects can be brought to life with one's thoughts, which infants and primitive peoples have. All of these thoughts have been repressed, which is why they are forbidding and yet familiar.

Explain Freud's argument about uncanny effects in the third section. Why are potentially uncanny phenomena sometimes not uncanny?

Freud believes that one key decisive factor is whether the uncanny effect takes place in real life, or an artwork supposed to take place in real life or not. The uncanny must take place in a context we believe to be real, perceived by someone who believes themselves to be in the real world. If we consciously know that the phenomena are taking place in a make-believe world, as for example in a fairy tale, the effect won't be uncanny. Freud makes a further distinction. On the one hand are those uncanny phenomena that have their roots in earlier phases of human consciousness, like worry about whether dolls will come to life. These kinds of uncanny effects are more likely to occur in real life. On the other hand are those uncanny phenomena rooted in childhood, like limbs coming to life on their own. These effects are more likely to occur in art, since for children these kinds of fantasies are rooted completely in the mind—they never had anything to do with real experiences. Freud believes that the uncanny effect of the former is in the clash between two modes of experiencing reality, whereas in the latter, the clash is between two phases of ego development.

The Uncanny Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for The Uncanny is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

Study Guide for The Uncanny

The Uncanny study guide contains a biography of Sigmund Freud, literature essays, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About The Uncanny

- The Uncanny Summary

- Character List

Essays for The Uncanny

The Uncanny essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of The Uncanny by Sigmund Freud.

- Racial Identity and the Uncanny in Season of Migration to the North

- “Handling Shakespeare and Psychiatry With Equal Facility”: On the Notion of the “Uncanny” in Satyajit Ray’s Nayak (1966) and Bergman's Wild Strawberries (1957)

- The Uncanny Village: How Freud Illuminates "Young Goodman Brown"

COMMENTS

The "Uncanny"1 (1919) SIGMUND FREUD I It is only rarely that a psychoanalyst feels impelled to in-vestigate the subject of aesthetics even when aesthetics is understood to mean not merely the theory of beauty, but the theory of the qualities of feeling. He works in other planes of mental life and has little to do with those sub-

Freud's essay makes a contribution to this supplement to the aesthetics of the "beautiful" by examining what we might call the aesthetics of the "fearful," the aesthetics of anxiety.-- Freud will wed psychoanalytic and aesthetic modes of thought to develop his theory of the uncanny; the theory remains incomplete if it fails to regard both of these.

The Uncanny, published in 1919, is one of the most famous of Sigmund Freud's essays. This is not only because many of his most foundational ideas had their genesis here but because the essay pertains to aesthetics and popular culture, making it both accessible and gripping for a broad readership. The Uncanny is a good example of Freud's ...

THE UNCANNYSigmund FreudIIt is only rarely that a psycho-analyst feels impelled to investigate the subject of aesthetics, even when aesthetics is understood to mean not merely the theory of beauty but the theory. f the qualities of feeling. He works in other strata of mental life and has little to do with the subdued emotional impulses which ...

The Uncanny. One hundred years ago, Sigmund Freud wrote his paper on ' The Uncanny ' (Das Unheimliche). His theory was rooted in everyday experiences and the aesthetics of popular culture, related to what is frightening, repulsive and distressing. The paper tackles the horrific concepts of inanimate figures coming to life, severed limbs ...

The "Uncanny" Bookreader Item Preview ... The "Uncanny" by Sigmund Freud. Topics psychology, history Collection opensource Language English Item Size 42127964. found at the university of texas at austin. Addeddate 2017-05-08 17:43:26 Identifier freud-uncanny_001 Identifier-ark ark:/13960/t1tf5610t Ocr ABBYY FineReader 11.0 Pages 19 Ppi ...

According to his friend and biographer Ernest Jones Sigmund Freud was fond regaling him with "strange or uncanny experiences with patients." Freud had a "particular relish" for such stories. 2019 marks the centenary of the publication of Freud's essay, "The 'Uncanny.'" Although much has been written on the essay during that time, Freud's concept of the uncanny is often not ...