More teens than ever are overdosing. Psychologists are leading new approaches to combat youth substance misuse

“Just Say No” didn’t work , but experts are employing new holistic programs to help steer kids away—or at least keep them from dying—from illicit substances.

Vol. 55 No. 2 Print version: page 48

- Substance Use, Abuse, and Addiction

For years, students in middle and high schools across the country were urged to “just say no” to drugs and alcohol. But it’s no secret that the Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E.) program, which was typically delivered by police officers who urged total abstinence, didn’t work. A meta-analysis found the program largely ineffective and one study even showed that kids who completed D.A.R.E. were more likely than their peers to take drugs ( Ennett, S. T., et al., American Journal of Public Health , Vol. 84, No. 9, 1994 ; Rosenbaum, D. P., & Hanson, G. S., Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency , Vol. 35, No. 4, 1998 ).

“We know that the ‘Just Say No’ campaign doesn’t work. It’s based in pure risks, and that doesn’t resonate with teens,” said developmental psychologist Bonnie Halpern-Felsher, PhD, a professor of pediatrics and founder and executive director of several substance use prevention and intervention curriculums at Stanford University. “There are real and perceived benefits to using drugs, as well as risks, such as coping with stress or liking the ‘high.’ If we only talk about the negatives, we lose our credibility.”

Partially because of the lessons learned from D.A.R.E., many communities are taking a different approach to addressing youth substance use. They’re also responding to very real changes in the drug landscape. Aside from vaping, adolescent use of illicit substances has dropped substantially over the past few decades, but more teens are overdosing than ever—largely because of contamination of the drug supply with fentanyl, as well as the availability of stronger substances ( Most reported substance use among adolescents held steady in 2022, National Institute on Drug Abuse ).

“The goal is to impress upon youth that far and away the healthiest choice is not to put these substances in your body, while at the same time acknowledging that some kids are still going to try them,” said Aaron Weiner, PhD, ABPP, a licensed clinical psychologist based in Lake Forest, Illinois, and immediate past-president of APA’s Division 50 (Society of Addiction Psychology). “If that’s the case, we want to help them avoid the worst consequences.”

While that approach, which incorporates principles of harm reduction, is not universally accepted, evidence is growing for its ability to protect youth from accidental overdoses and other consequences of substance use, including addiction, justice involvement, and problems at school. Psychologists have been a key part of the effort to create, test, and administer developmentally appropriate, evidence-based programs that approach prevention in a holistic, nonstigmatizing way.

“Drugs cannot be this taboo thing that young people can’t ask about anymore,” said Nina Christie, PhD, a postdoctoral research fellow in the Center on Alcohol, Substance Use, and Addictions at the University of New Mexico. “That’s just a recipe for young people dying, and we can’t continue to allow that.”

Changes in drug use

In 2022, about 1 in 3 high school seniors, 1 in 5 sophomores, and 1 in 10 eighth graders reported using an illicit substance in the past year, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse’s (NIDA) annual survey ( Monitoring the Future: National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2022: Secondary School Students , NIDA, 2023 [PDF, 7.78MB] ). Those numbers were down significantly from prepandemic levels and essentially at their lowest point in decades.

Substance use during adolescence is particularly dangerous because psychoactive substances, including nicotine, cannabis, and alcohol, can interfere with healthy brain development ( Winters, K. C., & Arria, A., Prevention Research , Vol. 18, No. 2, 2011 ). Young people who use substances early and frequently also face a higher risk of developing a substance use disorder in adulthood ( McCabe, S. E., et al., JAMA Network Open , Vol. 5, No. 4, 2022 ). Kids who avoid regular substance use are more likely to succeed in school and to avoid problems with the juvenile justice system ( Public policy statement on prevention, American Society of Addiction Medicine, 2023 ).

“The longer we can get kids to go without using substances regularly, the better their chances of having an optimal life trajectory,” Weiner said.

The drugs young people are using—and the way they’re using them—have also changed, and psychologists say this needs to inform educational efforts around substance use. Alcohol and cocaine are less popular than they were in the 1990s; use of cannabis and hallucinogens, which are now more salient and easier to obtain, were higher than ever among young adults in 2021 ( Marijuana and hallucinogen use among young adults reached all-time high in 2021, NIDA ).

“Gen Z is drinking less alcohol than previous generations, but they seem to be increasingly interested in psychedelics and cannabis,” Christie said. “Those substances have kind of replaced alcohol as the cool thing to be doing.”

Young people are also seeing and sharing content about substance use on social media, with a rise in posts and influencers promoting vaping on TikTok and other platforms ( Vassey, J., et al., Nicotine & Tobacco Research , 2023 ). Research suggests that adolescents and young adults who see tobacco or nicotine content on social media are more likely to later start using it ( Donaldson, S. I., et al., JAMA Pediatrics , Vol. 176, No. 9, 2022 ).

A more holistic view

Concern for youth well-being is what drove the well-intentioned, but ultimately ineffective, “mad rush for abstinence,” as Robert Schwebel, PhD, calls it. Though that approach has been unsuccessful in many settings, a large number of communities still employ it, said Schwebel, a clinical psychologist who created the Seven Challenges Program for treating substance use in youth.

But increasingly, those working to prevent and treat youth substance use are taking a different approach—one that aligns with principles Schwebel helped popularize through Seven Challenges.

A key tenet of modern prevention and treatment programs is empowering youth to make their own decisions around substance use in a developmentally appropriate way. Adolescents are exploring their identities (including how they personally relate to drugs), learning how to weigh the consequences of their actions, and preparing for adulthood, which involves making choices about their future. The Seven Challenges Program, for example, uses supportive journaling exercises, combined with counseling, to help young people practice informed decision-making around substance use with those processes in mind.

“You can insist until you’re blue in the face, but that’s not going to make people abstinent. They ultimately have to make their own decisions,” Schwebel said.

Today’s prevention efforts also tend to be more holistic than their predecessors, accounting for the ways drug use relates to other addictive behaviors, such as gaming and gambling, or risky choices, such as fighting, drag racing, and having unprotected sex. Risk factors for substance use—which include trauma, adverse childhood experiences, parental history of substance misuse, and personality factors such as impulsivity and sensation seeking—overlap with many of those behaviors, so it often makes sense to address them collectively.

[ Related: Psychologists are innovating to tackle substance use ]

“We’ve become more sophisticated in understanding the biopsychosocial determinants of alcohol and drug use and moving beyond this idea that it’s a disease and the only solution is medication,” said James Murphy, PhD, a professor of psychology at the University of Memphis who studies addictive behaviors and how to intervene.

Modern prevention programs also acknowledge that young people use substances to serve a purpose—typically either social or emotional in nature—and if adults expect them not to use, they should help teens learn to fulfill those needs in a different way, Weiner said.

“Youth are generally using substances to gain friends, avoid losing them, or to cope with emotional problems that they’re having,” he said. “Effective prevention efforts need to offer healthy alternatives for achieving those goals.”

Just say “know”

At times, the tenets of harm reduction and substance use prevention seem inherently misaligned. Harm reduction, born out of a response to the AIDS crisis, prioritizes bodily autonomy and meeting people where they are without judgment. For some harm reductionists, actively encouraging teens against using drugs could violate the principle of respecting autonomy, Weiner said.

On the other hand, traditional prevention advocates may feel that teaching adolescents how to use fentanyl test strips or encouraging them not to use drugs alone undermines the idea that they can choose not to use substances. But Weiner says both approaches can be part of the solution.

“It doesn’t have to be either prevention or harm reduction, and we lose really important tools when we say it has to be one or the other,” he said.

In adults, harm reduction approaches save lives, prevent disease transmission, and help people connect with substance use treatment ( Harm Reduction, NIDA, 2022 ). Early evidence shows similar interventions can help adolescents improve their knowledge and decision-making around drug use ( Fischer, N. R., Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy , Vol. 17, 2022 ). Teens are enthusiastic about these programs, which experts often call “Just Say Know” to contrast them with the traditional “Just Say No” approach. In one pilot study, 94% of students said a “Just Say Know” program provided helpful information and 92% said it might influence their approach to substance use ( Meredith, L. R., et al., The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse , Vol. 47, No. 1, 2021 ).

“Obviously, it’s the healthiest thing if we remove substance use from kids’ lives while their brains are developing. At the same time, my preference is that we do something that will have a positive impact on these kids’ health and behaviors,” said Nora Charles, PhD, an associate professor and head of the Youth Substance Use and Risky Behavior Lab at the University of Southern Mississippi. “If the way to do that is to encourage more sensible and careful engagement with illicit substances, that is still better than not addressing the problem.”

One thing not to do is to overly normalize drug use or to imply that it is widespread, Weiner said. Data show that it’s not accurate to say that most teens have used drugs in the past year or that drugs are “just a part of high school life.” In fact, students tend to overestimate how many of their peers use substances ( Dumas, T. M., et al., Addictive Behaviors , Vol. 90, 2019 ; Helms, S. W., et al., Developmental Psychology , Vol. 50, No. 12, 2014 ).

A way to incorporate both harm reduction and traditional prevention is to customize solutions to the needs of various communities. For example, in 2022, five Alabama high school students overdosed on a substance laced with fentanyl, suggesting that harm reduction strategies could save lives in that community. Other schools with less reported substance use might benefit more from a primary prevention-style program.

At Stanford, Halpern-Felsher’s Research and Education to Empower Adolescents and Young Adults to Choose Health (REACH) Lab has developed a series of free, evidence-based programs through community-based participatory research that can help populations with different needs. The REACH Lab offers activity-based prevention, intervention, and cessation programs for elementary, middle, and high school students, including curricula on alcohol, vaping, cannabis, fentanyl, and other drugs ( Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care , Vol. 52, No. 6, 2022 ). They’re also working on custom curricula for high-risk groups, including sexual and gender minorities.

The REACH Lab programs, including the comprehensive Safety First curriculum , incorporate honest discussion about the risks and benefits of using substances. For example: Drugs are one way to cope with stress, but exercise, sleep, and eating well can also help. Because many young people care about the environment, one lesson explores how cannabis and tobacco production causes environmental harm.

The programs also dispel myths about how many adolescents are using substances and help them practice skills, such as how to decline an offer to use drugs in a way that resonates with them. They learn about the developing brain in a positive way—whereas teens were long told they can’t make good decisions, Safety First empowers them to choose to protect their brains and bodies by making healthy choices across the board.

“Teens can make good decisions,” Halpern-Felsher said. “The equation is just different because they care more about certain things—peers, relationships—compared to adults.”

Motivating young people

Because substance use and mental health are so intertwined, some programs can do prevention successfully with very little drug-focused content. In one of the PreVenture Program’s workshops for teens, only half a page in a 35-page workbook explicitly mentions substances.

“That’s what’s fascinating about the evidence base for PreVenture,” said clinical psychologist Patricia Conrod, PhD, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Montreal who developed the program. “You can have quite a dramatic effect on young people’s substance use without even talking about it.”

PreVenture offers a series of 90-minute workshops that apply cognitive behavioral insights upstream (addressing the root causes of a potential issue rather than waiting for symptoms to emerge) to help young people explore their personality traits and develop healthy coping strategies to achieve their long-term goals.

Adolescents high in impulsivity, hopelessness, thrill-seeking, or anxiety sensitivity face higher risks of mental health difficulties and substance use, so the personalized material helps them practice healthy coping based on their personality type. For example, the PreVenture workshop that targets anxiety sensitivity helps young people learn to challenge cognitive distortions that can cause stress, then ties that skill back to their own goals.

The intervention can be customized to the needs of a given community (in one trial, drag racing outstripped substance use as the most problematic thrill-seeking behavior). In several randomized controlled trials of PreVenture, adolescents who completed the program started using substances later than peers who did not receive the intervention and faced fewer alcohol-related harms ( Newton, N. C., et al., JAMA Network Open , Vol. 5, No. 11, 2022 ). The program has also been shown to reduce the likelihood that adolescents will experiment with illicit substances, which relates to the current overdose crisis in North America, Conrod said ( Archives of General Psychiatry , Vol. 67, No. 1, 2010 ).

“People shouldn’t shy away from a targeted approach like this,” Conrod said. “Young people report that having the words and skills to manage their traits is actually helpful, and the research shows that at behavioral level, it really does protect them.”

As young people leave secondary school and enter college or adult life, about 30% will binge drink, 8% will engage in heavy alcohol use, and 20% will use illicit drugs ( Alcohol and Young Adults Ages 18 to 24, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2023 ; SAMHSA announces national survey on drug use and health (NSDUH) results detailing mental illness and substance use levels in 2021 ). But young people are very unlikely to seek help, even if those activities cause them distress, Murphy said. For that reason, brief interventions that leverage motivational interviewing and can be delivered in a school, work, or medical setting can make a big difference.

In an intervention Murphy and his colleagues are testing, young adults complete a questionnaire about how often they drink or use drugs, how much money they spend on substances, and negative things that have happened as a result of those choices (getting into an argument or having a hangover, for example).

In an hour-long counseling session, they then have a nonjudgmental conversation about their substance use, where the counselor gently amplifies any statements the young person makes about negative outcomes or a desire to change their behavior. Participants also see charts that quantify how much money and time they spend on substances, including recovering from being intoxicated, and how that stacks up against other things they value, such as exercise, family time, and hobbies.

“For many young people, when they look at what they allocate to drinking and drug use, relative to these other things that they view as much more important, it’s often very motivating,” Murphy said.

A meta-analysis of brief alcohol interventions shows that they can reduce the average amount participants drink for at least 6 months ( Mun, E.Y., et al., Prevention Science , Vol. 24, No. 8, 2023 ). Even a small reduction in alcohol use can be life-altering, Murphy said. The fourth or fifth drink on a night out, for example, could be the one that leads to negative consequences—so reducing intake to just three drinks may make a big difference for young people.

Conrod and her colleagues have also adapted the PreVenture Program for university students; they are currently testing its efficacy in a randomized trial across multiple institutions.

Christie is also focused on the young adult population. As a policy intern with Students for Sensible Drug Policy, she created a handbook of evidence-based policies that college campuses can use to reduce harm among students but still remain compliant with federal law. For example, the Drug Free Schools and Communities Act mandates that higher education institutions formally state that illegal drug use is not allowed on campus but does not bar universities from taking an educational or harm reduction-based approach if students violate that policy.

“One low-hanging fruit is for universities to implement a Good Samaritan policy, where students can call for help during a medical emergency and won’t get in trouble, even if illegal substance use is underway,” she said.

Ultimately, taking a step back to keep the larger goals in focus—as well as staying dedicated to prevention and intervention approaches backed by science—is what will help keep young people healthy and safe, Weiner said.

“What everyone can agree on is that we want kids to have the best life they can,” he said. “If we can start there, what tools do we have available to help?”

Further reading

Public Policy Statement on Prevention American Society of Addiction Medicine, 2023

Listen to young people: How to implement harm reduction in the collegiate setting Christie, N. C., 2023

Brief alcohol interventions for young adults: Strengthening effects and disentangling mechanisms to build personalized interventions for widespread uptake Special issue of Psychology of Addictive Behaviors , 2022

Addressing adolescent substance use with a public health prevention framework: The case for harm reduction Winer, J. M., et al., Annals of Medicine , 2022

A breath of knowledge: Overview of current adolescent e-cigarette prevention and cessation programs Liu, J., et al., Current Addiction Reports , 2020

Recommended Reading

Six things psychologists are talking about.

The APA Monitor on Psychology ® sister e-newsletter offers fresh articles on psychology trends, new research, and more.

Welcome! Thank you for subscribing.

Speaking of Psychology

Subscribe to APA’s audio podcast series highlighting some of the most important and relevant psychological research being conducted today.

Subscribe to Speaking of Psychology and download via:

Contact APA

You may also like.

Teenage Drug Abuse in the United States Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Social and health issues that take part during the formation of human identity have negative consequences on the individual’s further development. Thus, teenage drug abuse presents a severe danger to an individual’s health in adulthood. The problem of teenage drug abuse inflicts a threat to the future society and health state of the overall population in the United States. This essay will discuss the core reasons and consequences of teenage drug abuse and propose a possible solution based on the collected information.

There are several reasons for teenage drug abuse in the United States. As teenagers are influenced by high concertation of hormones, some of the core reasons for teenage drug abuse are specific to the age category, implying that those reasons are not connected to adult drug abuse. Moreover, teenagers are more influenced by external factors such as social connections and media. One of the core reasons for teenage drug abuse is the willingness to be accepted and validated in a social circle of individuals who already use drugs. In teenagers’ perception, drugs are often used in media as an attribute of cool characters, so they frequently try to fit in with the cool image, unaware of the consequences of drug use. In addition, current teenagers often experience depression and helplessness from being unable to control their lives or social rejection from excessive social media involvement and resort to drug abuse to feel better.

The consequences of teenage drug abuse include development and widespread poor morals, increased danger from sexual activity-related problems, such as STDs and unplanned pregnancy, dangerous driving, and poor performance in school. Even though some minor consequences of episodic drug abuse could be solved, threats like impaired driving present a significant danger to the population. Development and widespread of poor morals will also negatively affect the development of society as poor morals suggest an increased number of crime commitments among adolescents. With the current issues in the prison system, such as difficulties in offenders’ re-entry into the society, the teenagers’ future will be negatively affected in cases of crime commission.

Despite the complex character of the issues imposed by teenage drug abuse, one primary measure could solve the issue or partially improve the current state. The significant difference between teenage drug abuse and drug abuse among adults is parental participation in teenagers’ lives. Increasing the level of parental awareness on the issue of teenage drug abuse and providing them with necessary information could positively influence the situation. Providing parents with helpful information such as red flags in teenager’s behavior, and current state of drug involvement in the local area/school would help the parents establish connection with the teenager. The connection will provide an opportunity for a dialogue on the topic of drug use and its consequences. Moreover, active parental participation in teenagers’ activities would help prevent other issues, such as dangerous and harmful connections or violent tendencies.

In conclusion, this essay explored the issue of teenage drug abuse in the United States through the aspects of core reasons and consequences. Based on the collected information, teenagers are more subjected to drug abuse due to their social interactions and the high risk of depression tendencies. The increased parental participation in teenagers’ lives is the primary solution to the problem. Parents should express concerns about the child’s social circle and activities outside the home. Increasing parental awareness on the problem and providing opportunities for parent-teenager dialogue on the issue of drug abuse will positively influence the current state of teenage drug abuse in the United States.

- Healthy People 2020 and Tobacco Use

- History and Social Side of Drug Addiction

- Teenage Pregnancy in the Modern World

- Drug and Alcohol Abuse Among Teenagers

- Teenage Suicide: Statistics Data, Reasons and Prevention

- Explaining Drug Use: Social Scientific Theories

- Drug and Substance Addiction

- My Personal Beliefs About People With Addictions

- Alcoholics Anonymous Program Evaluation

- Drug-Related Individual Situation and Treatment Method

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, November 25). Teenage Drug Abuse in the United States. https://ivypanda.com/essays/teenage-drug-abuse-in-the-united-states/

"Teenage Drug Abuse in the United States." IvyPanda , 25 Nov. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/teenage-drug-abuse-in-the-united-states/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Teenage Drug Abuse in the United States'. 25 November.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Teenage Drug Abuse in the United States." November 25, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/teenage-drug-abuse-in-the-united-states/.

1. IvyPanda . "Teenage Drug Abuse in the United States." November 25, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/teenage-drug-abuse-in-the-united-states/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Teenage Drug Abuse in the United States." November 25, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/teenage-drug-abuse-in-the-united-states/.

Appointments at Mayo Clinic

- Tween and teen health

Teen drug abuse: Help your teen avoid drugs

Teen drug abuse can have a major impact on your child's life. Find out how to help your teen make healthy choices and avoid using drugs.

The teen brain is in the process of maturing. In general, it's more focused on rewards and taking risks than the adult brain. At the same time, teenagers push parents for greater freedom as teens begin to explore their personality.

That can be a challenging tightrope for parents.

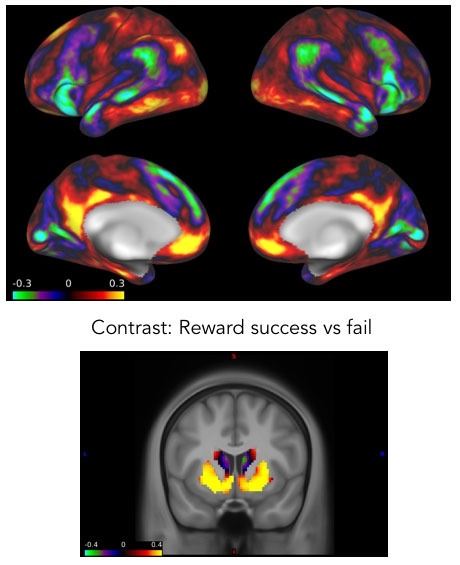

Teens who experiment with drugs and other substances put their health and safety at risk. The teen brain is particularly vulnerable to being rewired by substances that overload the reward circuits in the brain.

Help prevent teen drug abuse by talking to your teen about the consequences of using drugs and the importance of making healthy choices.

Why teens use or misuse drugs

Many factors can feed into teen drug use and misuse. Your teen's personality, your family's interactions and your teen's comfort with peers are some factors linked to teen drug use.

Common risk factors for teen drug abuse include:

- A family history of substance abuse.

- A mental or behavioral health condition, such as depression, anxiety or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

- Impulsive or risk-taking behavior.

- A history of traumatic events, such as seeing or being in a car accident or experiencing abuse.

- Low self-esteem or feelings of social rejection.

Teens may be more likely to try substances for the first time when hanging out in a social setting.

Alcohol and nicotine or tobacco may be some of the first, easier-to-get substances for teens. Because alcohol and nicotine or tobacco are legal for adults, these can seem safer to try even though they aren't safe for teens.

Teens generally want to fit in with peers. So if their friends use substances, your teen might feel like they need to as well. Teens also may also use substances to feel more confident with peers.

If those friends are older, teens can find themselves in situations that are riskier than they're used to. For example, they may not have adults present or younger teens may be relying on peers for transportation.

And if they are lonely or dealing with stress, teens may use substances to distract from these feelings.

Also, teens may try substances because they are curious. They may try a substance as a way to rebel or challenge family rules.

Some teens may feel like nothing bad could happen to them, and may not be able to understand the consequences of their actions.

Consequences of teen drug abuse

Negative consequences of teen drug abuse might include:

- Drug dependence. Some teens who misuse drugs are at increased risk of substance use disorder.

- Poor judgment. Teenage drug use is associated with poor judgment in social and personal interactions.

- Sexual activity. Drug use is associated with high-risk sexual activity, unsafe sex and unplanned pregnancy.

- Mental health disorders. Drug use can complicate or increase the risk of mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety.

- Impaired driving. Driving under the influence of any drug affects driving skills. It puts the driver, passengers and others on the road at risk.

- Changes in school performance. Substance use can result in worse grades, attendance or experience in school.

Health effects of drugs

Substances that teens may use include those that are legal for adults, such as alcohol or tobacco. They may also use medicines prescribed to other people, such as opioids.

Or teens may order substances online that promise to help in sports competition, or promote weight loss.

In some cases products common in homes and that have certain chemicals are inhaled for intoxication. And teens may also use illicit drugs such as cocaine or methamphetamine.

Drug use can result in drug addiction, serious impairment, illness and death. Health risks of commonly used drugs include the following:

- Cocaine. Risk of heart attack, stroke and seizures.

- Ecstasy. Risk of liver failure and heart failure.

- Inhalants. Risk of damage to the heart, lungs, liver and kidneys from long-term use.

- Marijuana. Risk of impairment in memory, learning, problem-solving and concentration; risk of psychosis, such as schizophrenia, hallucination or paranoia, later in life associated with early and frequent use. For teens who use marijuana and have a psychiatric disorder, there is a risk of depression and a higher risk of suicide.

- Methamphetamine. Risk of psychotic behaviors from long-term use or high doses.

- Opioids. Risk of respiratory distress or death from overdose.

- Electronic cigarettes (vaping). Higher risk of smoking or marijuana use. Exposure to harmful substances similar to cigarette smoking; risk of nicotine dependence. Vaping may allow particles deep into the lungs, or flavorings may include damaging chemicals or heavy metals.

Talking about teen drug use

You'll likely have many talks with your teen about drug and alcohol use. If you are starting a conversation about substance use, choose a place where you and your teen are both comfortable. And choose a time when you're unlikely to be interrupted. That means you both will need to set aside phones.

It's also important to know when not to have a conversation.

When parents are angry or when teens are frustrated, it's best to delay the talk. If you aren't prepared to answer questions, parents might let teens know that you'll talk about the topic at a later time.

And if a teen is intoxicated, wait until the teen is sober.

To talk to your teen about drugs:

- Ask your teen's views. Avoid lectures. Instead, listen to your teen's opinions and questions about drugs. Parents can assure teens that they can be honest and have a discussion without getting in trouble.

- Discuss reasons not to use drugs. Avoid scare tactics. Emphasize how drug use can affect the things that are important to your teen. Some examples might be sports performance, driving, health or appearance.

- Consider media messages. Social media, television programs, movies and songs can make drug use seem normal or glamorous. Talk about what your teen sees and hears.

- Discuss ways to resist peer pressure. Brainstorm with your teen about how to turn down offers of drugs.

- Be ready to discuss your own drug use. Think about how you'll respond if your teen asks about your own drug use, including alcohol. If you chose not to use drugs, explain why. If you did use drugs, share what the experience taught you.

Other preventive strategies

Consider other strategies to prevent teen drug abuse:

- Know your teen's activities. Pay attention to your teen's whereabouts. Find out what adult-supervised activities your teen is interested in and encourage your teen to get involved.

- Establish rules and consequences. Explain your family rules, such as leaving a party where drug use occurs and not riding in a car with a driver who's been using drugs. Work with your teen to figure out a plan to get home safely if the person who drove is using substances. If your teen breaks the rules, consistently enforce consequences.

- Know your teen's friends. If your teen's friends use drugs, your teen might feel pressure to experiment, too.

- Keep track of prescription drugs. Take an inventory of all prescription and over-the-counter medications in your home.

- Provide support. Offer praise and encouragement when your teen succeeds. A strong bond between you and your teen might help prevent your teen from using drugs.

- Set a good example. If you drink, do so in moderation. Use prescription drugs as directed. Don't use illicit drugs.

Recognizing the warning signs of teen drug abuse

Be aware of possible red flags, such as:

- Sudden or extreme change in friends, eating habits, sleeping patterns, physical appearance, requests for money, coordination or school performance.

- Irresponsible behavior, poor judgment and general lack of interest.

- Breaking rules or withdrawing from the family.

- The presence of medicine containers, despite a lack of illness, or drug paraphernalia in your teen's room.

Seeking help for teen drug abuse

If you suspect or know that your teen is experimenting with or misusing drugs:

- Plan your action. Finding out your teen is using drugs or suspecting it can bring up strong emotions. Before talking to your teen, make sure you and anyone who shares caregiving responsibility for the teen is ready. It can help to have a goal for the conversation. It can also help to figure out how you'll respond to the different ways your teen might react.

- Talk to your teen. You can never step in too early. Casual drug use can turn into too much use or addiction. This can lead to accidents, legal trouble and health problems.

- Encourage honesty. Speak calmly and express that you are coming from a place of concern. Share specific details to back up your suspicion. Verify any claims your child makes.

- Focus on the behavior, not the person. Emphasize that drug use is dangerous but that doesn't mean your teen is a bad person.

- Check in regularly. Spend more time with your teen. Know your teen's whereabouts and ask questions about the outing when your teen returns home.

- Get professional help. If you think your teen is involved in drug use, contact a health care provider or counselor for help.

It's never too soon to start talking to your teen about drug abuse. The conversations you have today can help your teen make healthy choices in the future.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

Children’s health information and parenting tips to your inbox.

Sign-up to get Mayo Clinic’s trusted health content sent to your email. Receive a bonus guide on ways to manage your child’s health just for subscribing. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing

Our e-newsletter will keep you up-to-date on the latest health information.

Something went wrong with your subscription.

Please try again in a couple of minutes

- Dulcan MK, ed. Substance use disorders and addictions. In: Dulcan's Textbook of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2021. https://psychiatryonline.org. Accessed Jan. 24, 2023.

- 6 parenting practices: Help reduce the chances your child will develop a drug or alcohol problem. Partnership to End Addiction. https://drugfree.org/addiction-education/. Accessed Jan. 24, 2023.

- Why do teens drink and use substances and is it normal? Partnership to End Addiction. https://drugfree.org/article/why-do-teens-drink-and-use-substances/. Accessed Jan. 24, 2023.

- Teens: Alcohol and other drugs. American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. https://www.aacap.org/aacap/families_and_youth/facts_for_families/fff-guide/Teens-Alcohol-And-Other-Drugs-003.aspx. Accessed Dec. 27, 2018.

- Drugged driving. National Institute on Drug Abuse. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/drugged-driving. Accessed Jan. 24, 2023.

- Marijuana talk kit. Partnership for Drug-Free Kids. https://drugfree.org/drugs/marijuana-what-you-need-to-know/. Accessed Jan. 24, 2023.

- Drug guide for parents: Learn the facts to keep your teen safe. Partnership for Drug-Free Kids. https://www.drugfree.org/resources/. Accessed Dec. 12, 2018.

- Vaping: What you need to know and how to talk with your kids about vaping. Partnership to End Addiction. https://drugfree.org/addiction-education/. Accessed Jan. 24, 2023.

- How to listen. Partnership for Drug-Free Kids. https://www.drugfree.org/resources/. Accessed Dec. 12, 2018.

- Drug abuse prevention starts with parents. American Academy of Pediatrics. https://publications.aap.org/patiented/article/doi/10.1542/peo_document352/81984/Drug-Abuse-Prevention-Starts-With-Parents. Accessed Jan. 24, 2023.

- How to talk to your kids about drugs if you did drugs. Partnership for Drug-Free Kids. https://www.drugfree.org/resources/. Accessed Dec. 12, 2018.

- My child tried drugs, what should I do? Partnership to End Addiction. https://drugfree.org/article/my-child-tried-drugs-what-should-i-do/. Accessed Jan. 24, 2023.

- Gage SH, et al. Association between cannabis and psychosis: Epidemiologic evidence. Biological Psychiatry. 2016;79:549.

- Quick facts on the risks of e-cigarettes for kids, teens and young adults. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/e-cigarettes/Quick-Facts-on-the-Risks-of-E-cigarettes-for-Kids-Teens-and-Young-Adults.html. Accessed Jan. 30, 2023.

- Distracted Driving

- Piercings: How to prevent complications

- Talking to your teen about sex

- Teen suicide

- Teens and social media use

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Weight loss surgery for kids

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Healthy Lifestyle

- Teen drug abuse Help your teen avoid drugs

Help transform healthcare

Your donation can make a difference in the future of healthcare. Give now to support Mayo Clinic's research.

Home — Essay Samples — Nursing & Health — Substance Abuse — Teenage Drug Abuse In The United States

Teenage Drug Abuse in The United States

- Categories: Drug Addiction Substance Abuse Teenagers

About this sample

Words: 1000 |

Published: Sep 1, 2020

Words: 1000 | Pages: 2 | 5 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, the physiological impact of teenage drug abuse, the psychological toll of teenage drug abuse, societal implications of teenage drug abuse, works cited.

- Center on Addiction. (n.d.). Teen Drug Abuse: Get the Facts. Retrieved from https://www.centeronaddiction.org/addiction-prevention/teenage-addiction/teen-drug-abuse-facts

- Foundation for a Drug-Free World. (n.d.). The Truth About Drugs: Real People, Real Stories.

- Lubman, D. I., & Yücel, M. (2016). Substance use and the adolescent brain: A toxic combination? Journal of Psychopharmacology, 30(2), 118-120.

- National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence. (n.d.). Facts About Alcohol.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2018). Drugs, Brains, and Behavior: The Science of Addiction. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugs-brains-behavior-science-addiction/drug-use-in-adolescence

- New York Times. (2019). D.A.R.E. Program Teaches the Skills to Say No to Drugs but Not to Use. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/25/us/dare-program-lessons.html

- Office of National Drug Control Policy. (2018). Teen Substance Use & Risks.

- Paglia-Boak, A., Adlaf, E. M., & Mann, R. E. (2011). Drug Use Among Ontario Students, 1977–2011: Detailed OSDUHS Findings (CAMH Research Document Series No. 35). Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

- Slavit, W. I., & Mooney, A. (2017). Adolescent Substance Use. Pediatric Clinics, 64(1), 231-244.

- Yap, M. B. H., Cheong, T. W. K., Zaravinos-Tsakos, F., Lubman, D. I., & Jorm, A. F. (2017). Modifiable parenting factors associated with adolescent alcohol misuse: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Addiction, 112(7), 1142-1162.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof Ernest (PhD)

Verified writer

- Expert in: Nursing & Health Sociology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 657 words

2 pages / 1066 words

1 pages / 661 words

1 pages / 435 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Substance Abuse

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018). The Importance of Mental Health: Parity for Mental Health and Substance Use.

Drug courts play a pivotal role in the criminal justice system, offering individuals grappling with substance abuse disorders an alternative to incarceration. These programs are structured with distinct phases that participants [...]

The issue of substance abuse presents a pervasive and multifaceted challenge, impacting individuals, families, and communities globally. Its consequences extend far beyond individual suffering, posing significant threats to [...]

Pleasure Unwoven is a documentary film produced by Dr. Kevin McCauley that explores the complex nature of addiction and the underlying neurobiology behind it. The film delves into the concept of pleasure and how it relates to [...]

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a counseling technique which assists the interviewee in identifying the internal motivation to change the client’s behavior by resolving ambivalence and insecurities. The term holds similar [...]

The Beatles’ were no doubt the most influential British band in the 1960’s, with their music bringing and becoming a revolution to the face of rock and roll. Their use of drugs through their music changed the way and the [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Essay on Impact of Drugs on Youth

Students are often asked to write an essay on Impact of Drugs on Youth in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Impact of Drugs on Youth

Introduction.

Drugs have a significant impact on youth, affecting their health, education, and social relationships.

Health Consequences

Drugs can damage a young person’s physical and mental health. They can lead to addiction, organ damage, and mental disorders.

Educational Impact

Drugs can impair a youth’s ability to concentrate and learn, leading to poor academic performance.

Social Effects

Drug use can lead to isolation from friends and family, and involvement in illegal activities.

250 Words Essay on Impact of Drugs on Youth

The impact of drugs on youth is a topic of significant concern, affecting individuals, families, and communities worldwide. The youth, being the most vulnerable demographic, are particularly susceptible to the harmful effects of drug use.

The Allure of Drugs

The allure of drugs for young people often stems from a desire to fit in, escape reality, or experiment. Peer pressure, social media influence, and the thrill of rebellion can all contribute to the initiation of drug use. This early exposure can lead to addiction, impacting their physical, mental, and social health.

Physical Impact

Drugs can have devastating physical effects on young bodies. They can hinder growth, affect brain development, and lead to long-term health problems like heart disease and cancer. Moreover, drug use can lead to risky behaviors, increasing the likelihood of accidents, violence, and sexually transmitted diseases.

Mental Impact

On the mental front, drug use can exacerbate or trigger mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety, and psychosis. It can also impair cognitive abilities, memory, and academic performance, limiting a young person’s potential for success.

Social Impact

Socially, drug use can lead to isolation, strained relationships, and a loss of interest in previously enjoyed activities. It can also lead to legal issues, reducing opportunities for future employment and education.

500 Words Essay on Impact of Drugs on Youth

The global landscape of drug abuse and addiction is a complex issue that has significant implications on the youth. The impact of drugs on youth is far-reaching, affecting not just their physical health, but also their mental well-being, academic performance, and future prospects.

The Physical Consequences

The first and most apparent impact of drugs on youth is the physical damage. Substance abuse can lead to a host of health problems, ranging from liver damage, cardiovascular diseases, to neurological issues. Furthermore, drugs can interfere with the normal growth and development processes, particularly during the critical adolescent years when the body undergoes significant changes.

Mental Health Implications

The social implications of drug use among youth are equally significant. Substance abuse can strain relationships with family and friends, leading to isolation and loneliness. It can also lead to delinquency, crime, and a general disregard for societal norms and values. This damage to their social fabric can have long-term consequences, affecting their ability to form meaningful relationships and contribute positively to society.

Educational and Career Impact

Substance abuse can severely impact a young person’s educational attainment and future career prospects. The cognitive impairments caused by drug use can lead to poor academic performance, lower grades, and increased likelihood of dropping out. This, in turn, can limit their career opportunities and earning potential, trapping them in a cycle of poverty and substance abuse.

Prevention and Intervention

In conclusion, the impact of drugs on youth is a multifaceted issue that extends beyond the individual to families, schools, and communities. It is a pressing problem that requires collective effort and commitment to address. By understanding the depth of its impact, we can better equip ourselves to combat this issue and pave the way for a healthier, more productive future for our youth.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

Happy studying!

please help me with problems faced by drugs addicted people essay note

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Drugs, Brains, and Behavior: The Science of Addiction Preventing Drug Misuse and Addiction: The Best Strategy

Why is adolescence a critical time for preventing drug addiction.

As noted previously, early use of drugs increases a person's chances of becoming addicted. Remember, drugs change the brain—and this can lead to addiction and other serious problems. So, preventing early use of drugs or alcohol may go a long way in reducing these risks.

Risk of drug use increases greatly during times of transition. For an adult, a divorce or loss of a job may increase the risk of drug use. For a teenager, risky times include moving, family divorce, or changing schools. 35 When children advance from elementary through middle school, they face new and challenging social, family, and academic situations. Often during this period, children are exposed to substances such as cigarettes and alcohol for the first time. When they enter high school, teens may encounter greater availability of drugs, drug use by older teens, and social activities where drugs are used. When individuals leave high school and live more independently, either in college or as an employed adult, they may find themselves exposed to drug use while separated from the protective structure provided by family and school.

A certain amount of risk-taking is a normal part of adolescent development. The desire to try new things and become more independent is healthy, but it may also increase teens’ tendencies to experiment with drugs. The parts of the brain that control judgment and decision-making do not fully develop until people are in their early or mid-20s. This limits a teen’s ability to accurately assess the risks of drug experimentation and makes young people more vulnerable to peer pressure. 36

Because the brain is still developing, using drugs at this age has more potential to disrupt brain function in areas critical to motivation, memory, learning, judgment, and behavior control. 12

Can research-based programs prevent drug addiction in youth?

Yes. The term research-based or evidence-based means that these programs have been designed based on current scientific evidence, thoroughly tested, and shown to produce positive results. Scientists have developed a broad range of programs that positively alter the balance between risk and protective factors for drug use in families, schools, and communities. Studies have shown that research-based programs, such as described in NIDA’s Principles of Substance Abuse Prevention for Early Childhood: A Research-Based Guide and Preventing Drug Use among Children and Adolescents: A Research-Based Guide for Parents, Educators, and Community Leaders , can significantly reduce early use of tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs. 37 Also, while many social and cultural factors affect drug use trends, when young people perceive drug use as harmful, they often reduce their level of use. 38

How do research-based prevention programs work?

These prevention programs work to boost protective factors and eliminate or reduce risk factors for drug use. The programs are designed for various ages and can be used in individual or group settings, such as the school and home. There are three types of programs:

- Universal programs address risk and protective factors common to all children in a given setting, such as a school or community.

- Selective programs are for groups of children and teens who have specific factors that put them at increased risk of drug use.

- Indicated programs are designed for youth who have already started using drugs.

Young Brains Under Study

Using cutting-edge imaging technology, scientists from the NIDA’s Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study will look at how childhood experiences, including use of any drugs, interact with each other and with a child’s changing biology to affect brain development and social, behavioral, academic, health, and other outcomes. As the only study of its kind, the ABCD study will yield critical insights into the foundational aspects of adolescence that shape a person’s future.

Economics of Prevention

Evidence-based interventions for substance use can save society money in medical costs and help individuals remain productive members of society. Such programs can return anywhere from very little to $65 per every dollar invested in prevention. 39

Adolescent Drug Abuse

According to Nawi et al. (2021), in 2016, 5.6% of the world’s population of age range fifteen to sixty-five at least utilized drugs. Drugs are supplements for good health if used in reasonable quantities while following qualified doctors’ guidelines. However, there are instances that drug use is bizarre. The bizarre drug use is known as drug abuse and is high among younger generations (Nawi et al., 2021). The effects of drug abuse are threats to socio-economic and collective development. Therefore, it is paramount to identify the cause-root of drug abuse, especially among teenage, to curb such a health problem. Consequently, various literature has been developed to postulate the risk factors leading to teenagers’ drug abuse. Several risk factors are identified across a spectrum of literature; some risk factors overlap. According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2022), the risk factors for drug abuse by adolescents can be effectively managed by prioritizing the most prevalent risk factors as follows: substance abuse history in the family, parental view of the behavior is standard, poor parental guidelines, parent (s) abusing drugs, and absence of support towards teenager gender identity, or sexual orientation.

Drug abuse is a health issue that eminent itself in a person after exposure to various stimuli. In my opinion and from lived experience, I believe drug abuse among youths is triggered by the environment (availability of drugs and peers) and parental neglect. Through such keen observations, I have realized that in my neighborhood, the number of individuals with retarded growth or multiple symptoms of drug abuse is decreasing, especially among youths. The cause of the reduction could be strict government policies, increased social security benefits to needy families, and the use of evidence-based policing in curbing illicit drug businesses. As a child, drug corners and stores were easy to locate, but as I grew, drug outlets were decreasing in number, reducing the availability of drugs to youths. Generally, I have identified trends in the decrease in teenage drug abuse. Through research, I could extract statistical data from two sources that, on analysis, prove my observation to be valid. Statistical data from SAMHSA (2014) indicates that the rate of drug use prevalence among youths in the age bracket of twelve to seventeen was 8.8%. However, recent statistics show that the prevalence is 8.33% (NCDAS, 2023). The two sets of data show that there has been a reduction in drug use prevalence among teenagers in the past decade, concurring with my lived experience.

Nevertheless, drug abuse is still a health issue that needs sound policies, social practices, and strategies to be controlled. Drug abuse is rampant, but the degree varies with drug type. The major contributor to a drug being frequently abused is its ease of acquisition. Therefore, drugs that can easily be acquired, such as illicit drugs, are frequently abused. Considerately, I rank Cocaine and Marijuana as the illicit drugs that are being abused. Prescribed drugs are less abused as their circulations are significantly controlled by the government and medical practitioners.

The fight against drugs will have a positive outcome if the strategies employed are proactive. Prevention mechanisms are of utmost importance in this scenario because drug abuse is accompanied by addictive nature, making it an uphill and resourceful undertaking to cure. As youths’ active hours are primarily spent in schools, prevention measures or programs must be school-based. Therefore, preventing teenage drug abuse includes implementing school-based programs such as Fast Track (RHIhub, 2020), targeted programs, and universal programs (National Crime Prevention Centre, 2022).

Fast Track is an evidence-based approach directed towards children enrolling in kindergarten to protect them from indulging in drug abuse activities through grade ten. The program incorporates various interventions as the child grows through the grades. The major interventions associated with the program are child tutoring, teacher-led sessions, home visits, and parent training groups. The program concept has been used in a particular scenario leading to positive results. Evidence shows that the program reduced the development of substance abuse disorders among youths, binge drinking, and alcohol consumption (RHIhub, 2020).

The targeted program comprises the Schools Using Coordinated Community Efforts to Strengthen Students project and Project Toward No Drug Abuse (TND). Targeted programs are considerately designed for specific youth groups, for instance, youth at high risk of indulging in drug abuse activities or of a particular age range. The programs offer varied interventions, ranging from parent programs, prevention education series, social skill training, and role-playing exercises. Both the programs under the targeted program have been tested to be efficient. For instance, the TND program proved to facilitate a reduction in alcohol use and hard drug use among teenagers (National Crime Prevention Centre, 2022).

Universal programs consist of two categorical programs. The two programs are Project ALERT and project life skills training. About Project ALERT, it is a drug abuse prevention mechanism that is popular among middle-class schools. The program focuses on high-risk youths and curbing three drugs (alcohol, marijuana, and cigarettes) abused. The intervention scheme of the program workout in eleven classroom sessions with three subsequent booster sessions in the following year. The program intervention scheme is designed to aid students in drug abuse awareness and enable them to create sound emotional and social decisions to overcome peer pressure on drug abuse. Generally, the program aims to impart students with the strength of knowledge in resistance behavior to withstand any pressures of drug abuse temptations. Project ALERT program has proven successful in ensuring youths are not engaging in risky drinking. Evidence shows that projects ALERT students’ alcohol consumption reduced by twenty-four percent after an 18-month evaluation (National Crime Prevention Centre, 2022).

Teenagers are a fragile population as they are more impulsive, and any treatment that is not suitable will facilitate their antisocial behavior instead of curing them. Therefore, any means to treat a teenager should consider that they are still developing and can adequately change. Thus, I would propose treatment interventions such as medical therapies and subjection to the criminal justice system. Therapies are the most benign mechanisms in treating a drug abuse effect such as SUD development in youths in that youths have the mental characteristics to continue learning and unlearn the unwanted knowledge through gaining an insight into reality. Therefore, I highly recommend cognitive-behavioral therapy as the primary treatment approach to drug abuse effects in youth. I would recommend subjecting the youth drug abuser to the criminal justice system. Juvenile jails, in most cases, are fitted with rehabs. When a child is exposed to difficulty and solitude plus rehab services, there is evidence that they constantly reshape their behavior more than those who have not been subjected to juvenile rehab. The primary reason I would prefer the approaches in treating juveniles is that both tend to redefine the youth victims’ lives and expose them to a transformation path in the most salient way.

Rural Health Information Hub. (2020). Prevention Programs for Youth and Families. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/substance-abuse/2/prevention/youth-and-families

National Crime Prevention Centre (Canada). (2022). School-based drug abuse prevention: promising and successful programs . Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada. https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/sclbsd-drgbs/index-en.aspx

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (September 4, 2014). The NSDUH Report: Substance Use and Mental Health Estimates from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Overview of Findings . Rockville, MD. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-SR200-RecoveryMonth-2014/NSDUH-SR200-RecoveryMonth-2014.htm

National Center for Drug Abuse Statistics (NCDAS). (2023). Drug Use Among Youth: Facts & Statistics. https://drugabusestatistics.org/teen-drug-use/

Nawi, A. M., Ismail, R., Ibrahim, F., Hassan, M. R., Manaf, M. R. A., Amit, N., … & Shafurdin, N. S. (2021). Risk and protective factors of drug abuse among adolescents: a systematic review. BMC public health , 21 (1), 1–15.

Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2022). High-Risk Substance Use Among Youth. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services . https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/substance-use/index.htm#:~:text=Risk%20Factors%20for%20High%2DRisk%20Substance%20Use&text=Poor%20parental%20monitoring,delinquent%20or%20substance%20using%20peers

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Related Essays

Black women’s club movement, early childhood education program review, marginalized group career counseling, the first stages of self-expression, abusive wilderness therapy: a violation of human rights, reducing gambling addiction in australia, popular essay topics.

- American Dream

- Artificial Intelligence

- Black Lives Matter

- Bullying Essay

- Career Goals Essay

- Causes of the Civil War

- Child Abusing

- Civil Rights Movement

- Community Service

- Cultural Identity

- Cyber Bullying

- Death Penalty

- Depression Essay

- Domestic Violence

- Freedom of Speech

- Global Warming

- Gun Control

- Human Trafficking

- I Believe Essay

- Immigration

- Importance of Education

- Israel and Palestine Conflict

- Leadership Essay

- Legalizing Marijuanas

- Mental Health

- National Honor Society

- Police Brutality

- Pollution Essay

- Racism Essay

- Romeo and Juliet

- Same Sex Marriages

- Social Media

- The Great Gatsby

- The Yellow Wallpaper

- Time Management

- To Kill a Mockingbird

- Violent Video Games

- What Makes You Unique

- Why I Want to Be a Nurse

- Send us an e-mail

- Open access

- Published: 13 November 2021

Risk and protective factors of drug abuse among adolescents: a systematic review

- Azmawati Mohammed Nawi 1 ,

- Rozmi Ismail 2 ,

- Fauziah Ibrahim 2 ,

- Mohd Rohaizat Hassan 1 ,

- Mohd Rizal Abdul Manaf 1 ,

- Noh Amit 3 ,

- Norhayati Ibrahim 3 &

- Nurul Shafini Shafurdin 2

BMC Public Health volume 21 , Article number: 2088 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

147k Accesses

111 Citations

20 Altmetric

Metrics details

Drug abuse is detrimental, and excessive drug usage is a worldwide problem. Drug usage typically begins during adolescence. Factors for drug abuse include a variety of protective and risk factors. Hence, this systematic review aimed to determine the risk and protective factors of drug abuse among adolescents worldwide.

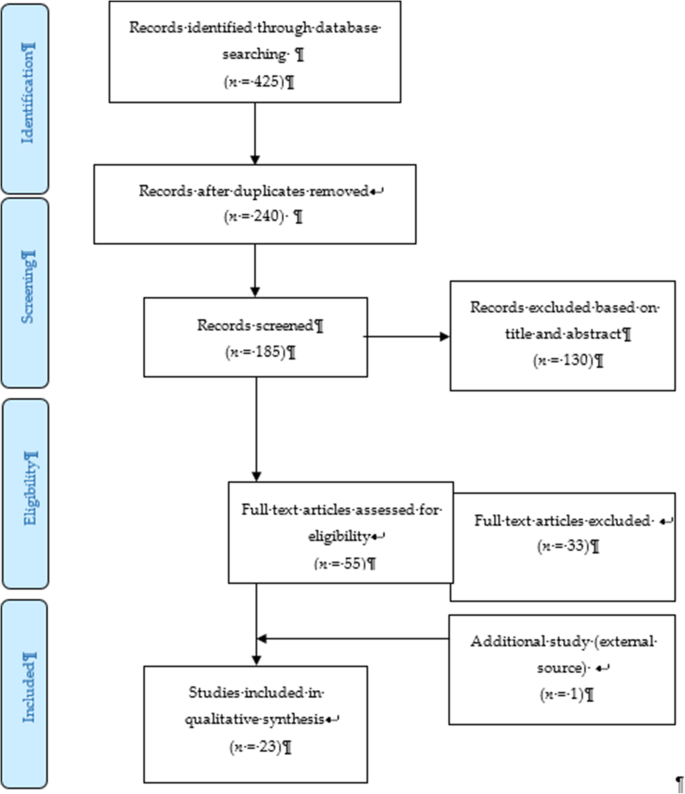

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) was adopted for the review which utilized three main journal databases, namely PubMed, EBSCOhost, and Web of Science. Tobacco addiction and alcohol abuse were excluded in this review. Retrieved citations were screened, and the data were extracted based on strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria include the article being full text, published from the year 2016 until 2020 and provided via open access resource or subscribed to by the institution. Quality assessment was done using Mixed Methods Appraisal Tools (MMAT) version 2018 to assess the methodological quality of the included studies. Given the heterogeneity of the included studies, a descriptive synthesis of the included studies was undertaken.

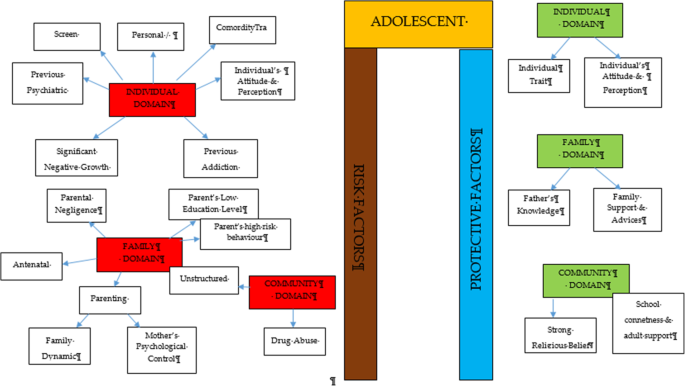

Out of 425 articles identified, 22 quantitative articles and one qualitative article were included in the final review. Both the risk and protective factors obtained were categorized into three main domains: individual, family, and community factors. The individual risk factors identified were traits of high impulsivity; rebelliousness; emotional regulation impairment, low religious, pain catastrophic, homework completeness, total screen time and alexithymia; the experience of maltreatment or a negative upbringing; having psychiatric disorders such as conduct problems and major depressive disorder; previous e-cigarette exposure; behavioral addiction; low-perceived risk; high-perceived drug accessibility; and high-attitude to use synthetic drugs. The familial risk factors were prenatal maternal smoking; poor maternal psychological control; low parental education; negligence; poor supervision; uncontrolled pocket money; and the presence of substance-using family members. One community risk factor reported was having peers who abuse drugs. The protective factors determined were individual traits of optimism; a high level of mindfulness; having social phobia; having strong beliefs against substance abuse; the desire to maintain one’s health; high paternal awareness of drug abuse; school connectedness; structured activity and having strong religious beliefs.

The outcomes of this review suggest a complex interaction between a multitude of factors influencing adolescent drug abuse. Therefore, successful adolescent drug abuse prevention programs will require extensive work at all levels of domains.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Drug abuse is a global problem; 5.6% of the global population aged 15–64 years used drugs at least once during 2016 [ 1 ]. The usage of drugs among younger people has been shown to be higher than that among older people for most drugs. Drug abuse is also on the rise in many ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) countries, especially among young males between 15 and 30 years of age. The increased burden due to drug abuse among adolescents and young adults was shown by the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study in 2013 [ 2 ]. About 14% of the total health burden in young men is caused by alcohol and drug abuse. Younger people are also more likely to die from substance use disorders [ 3 ], and cannabis is the drug of choice among such users [ 4 ].

Adolescents are the group of people most prone to addiction [ 5 ]. The critical age of initiation of drug use begins during the adolescent period, and the maximum usage of drugs occurs among young people aged 18–25 years old [ 1 ]. During this period, adolescents have a strong inclination toward experimentation, curiosity, susceptibility to peer pressure, rebellion against authority, and poor self-worth, which makes such individuals vulnerable to drug abuse [ 2 ]. During adolescence, the basic development process generally involves changing relations between the individual and the multiple levels of the context within which the young person is accustomed. Variation in the substance and timing of these relations promotes diversity in adolescence and represents sources of risk or protective factors across this life period [ 6 ]. All these factors are crucial to helping young people develop their full potential and attain the best health in the transition to adulthood. Abusing drugs impairs the successful transition to adulthood by impairing the development of critical thinking and the learning of crucial cognitive skills [ 7 ]. Adolescents who abuse drugs are also reported to have higher rates of physical and mental illness and reduced overall health and well-being [ 8 ].

The absence of protective factors and the presence of risk factors predispose adolescents to drug abuse. Some of the risk factors are the presence of early mental and behavioral health problems, peer pressure, poorly equipped schools, poverty, poor parental supervision and relationships, a poor family structure, a lack of opportunities, isolation, gender, and accessibility to drugs [ 9 ]. The protective factors include high self-esteem, religiosity, grit, peer factors, self-control, parental monitoring, academic competence, anti-drug use policies, and strong neighborhood attachment [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ].

The majority of previous systematic reviews done worldwide on drug usage focused on the mental, psychological, or social consequences of substance abuse [ 16 , 17 , 18 ], while some focused only on risk and protective factors for the non-medical use of prescription drugs among youths [ 19 ]. A few studies focused only on the risk factors of single drug usage among adolescents [ 20 ]. Therefore, the development of the current systematic review is based on the main research question: What is the current risk and protective factors among adolescent on the involvement with drug abuse? To the best of our knowledge, there is limited evidence from systematic reviews that explores the risk and protective factors among the adolescent population involved in drug abuse. Especially among developing countries, such as those in South East Asia, such research on the risk and protective factors for drug abuse is scarce. Furthermore, this review will shed light on the recent trends of risk and protective factors and provide insight into the main focus factors for prevention and control activities program. Additionally, this review will provide information on how these risk and protective factors change throughout various developmental stages. Therefore, the objective of this systematic review was to determine the risk and protective factors of drug abuse among adolescents worldwide. This paper thus fills in the gaps of previous studies and adds to the existing body of knowledge. In addition, this review may benefit certain parties in developing countries like Malaysia, where the national response to drugs is developing in terms of harm reduction, prison sentences, drug treatments, law enforcement responses, and civil society participation.

This systematic review was conducted using three databases, PubMed, EBSCOhost, and Web of Science, considering the easy access and wide coverage of reliable journals, focusing on the risk and protective factors of drug abuse among adolescents from 2016 until December 2020. The search was limited to the last 5 years to focus only on the most recent findings related to risk and protective factors. The search strategy employed was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) checklist.

A preliminary search was conducted to identify appropriate keywords and determine whether this review was feasible. Subsequently, the related keywords were searched using online thesauruses, online dictionaries, and online encyclopedias. These keywords were verified and validated by an academic professor at the National University of Malaysia. The keywords used as shown in Table 1 .

Selection criteria

The systematic review process for searching the articles was carried out via the steps shown in Fig. 1 . Firstly, screening was done to remove duplicate articles from the selected search engines. A total of 240 articles were removed in this stage. Titles and abstracts were screened based on the relevancy of the titles to the inclusion and exclusion criteria and the objectives. The inclusion criteria were full text original articles, open access articles or articles subscribed to by the institution, observation and intervention study design and English language articles. The exclusion criteria in this search were (a) case study articles, (b) systematic and narrative review paper articles, (c) non-adolescent-based analyses, (d) non-English articles, and (e) articles focusing on smoking (nicotine) and alcohol-related issues only. A total of 130 articles were excluded after title and abstract screening, leaving 55 articles to be assessed for eligibility. The full text of each article was obtained, and each full article was checked thoroughly to determine if it would fulfil the inclusion criteria and objectives of this study. Each of the authors compared their list of potentially relevant articles and discussed their selections until a final agreement was obtained. A total of 22 articles were accepted to be included in this review. Most of the excluded articles were excluded because the population was not of the target age range—i.e., featuring subjects with an age > 18 years, a cohort born in 1965–1975, or undergraduate college students; the subject matter was not related to the study objective—i.e., assessing the effects on premature mortality, violent behavior, psychiatric illness, individual traits, and personality; type of article such as narrative review and neuropsychiatry review; and because of our inability to obtain the full article—e.g., forthcoming work in 2021. One qualitative article was added to explain the domain related to risk and the protective factors among the adolescents.

PRISMA flow diagram showing the selection of studies on risk and protective factors for drug abuse among adolescents.2.2. Operational Definition

Drug-related substances in this context refer to narcotics, opioids, psychoactive substances, amphetamines, cannabis, ecstasy, heroin, cocaine, hallucinogens, depressants, and stimulants. Drugs of abuse can be either off-label drugs or drugs that are medically prescribed. The two most commonly abused substances not included in this review are nicotine (tobacco) and alcohol. Accordingly, e-cigarettes and nicotine vape were also not included. Further, “adolescence” in this study refers to members of the population aged between 10 to 18 years [ 21 ].

Data extraction tool

All researchers independently extracted information for each article into an Excel spreadsheet. The data were then customized based on their (a) number; (b) year; (c) author and country; (d) titles; (e) study design; (f) type of substance abuse; (g) results—risks and protective factors; and (h) conclusions. A second reviewer crossed-checked the articles assigned to them and provided comments in the table.

Quality assessment tool

By using the Mixed Method Assessment Tool (MMAT version 2018), all articles were critically appraised for their quality by two independent reviewers. This tool has been shown to be useful in systematic reviews encompassing different study designs [ 22 ]. Articles were only selected if both reviewers agreed upon the articles’ quality. Any disagreement between the assigned reviewers was managed by employing a third independent reviewer. All included studies received a rating of “yes” for the questions in the respective domains of the MMAT checklists. Therefore, none of the articles were removed from this review due to poor quality. The Cohen’s kappa (agreement) between the two reviewers was 0.77, indicating moderate agreement [ 23 ].