Does the Death Penalty Deter Crime?

General reference (not clearly pro or con).

John Gramlich, Senior Writer and Editor at Pew Research Center, in a July 19, 2021 article, “10 Facts about the Death Penalty in the U.S.,” available at pewresearch.org, stated:

“A majority of Americans have concerns about the fairness of the death penalty and whether it serves as a deterrent against serious crime. More than half of U.S. adults (56%) say Black people are more likely than White people to be sentenced to death for committing similar crimes. About six-in-ten (63%) say the death penalty does not deter people from committing serious crimes, and nearly eight-in-ten (78%) say there is some risk that an innocent person will be executed.” July 19, 2021

Charles Stimson, JD, Acting Chief of Staff and Senior Legal Fellow of the Heritage Foundation, in a Dec. 20, 2019 article, “The Death Penalty Is Appropriate,” available at heritage.org, stated:

“That said, the death penalty serves three legitimate penological objectives: general deterrence, specific deterrence, and retribution. The first, general deterrence, is the message that gets sent to people who are thinking about committing heinous crimes that they shouldn’t do it or else they might end up being sentenced to death. The second, specific deterrence, is specific to the defendant. It simply means that the person who is subjected to the death penalty won’t be alive to kill other people. The third penological goal, retribution, is an expression of society’s right to make a moral judgment by imposing a punishment on a wrongdoer befitting the crime he has committed. Twenty-nine states, and the people’s representatives in Congress have spoken loudly; the death penalty should be available for the worst of the worst.” Dec. 20, 2019

Armstrong Williams, Owner and Manager of Howard Stirk Holdings I & II Broadcast Television Stations, in a May, 25, 2021 article, “The Death Penalty Remains the Strongest Deterrent to Violent Crime,” available at thehill.com, stated:

“There must be some form to hold murderers accountable and, historically, the death penalty has been the most effective way of doing so. It could very well be that a firing squad is the most humane way, especially compared to lethal injection, where there have been cases of prisoners experiencing excruciating pain for sometimes over an hour. These examples are certainly worthy of our consideration and discussion. But one thing is clear: We still need the death penalty, if for no other reason, as a deterrent for other potential criminals.” May, 25, 2021

David Muhlhausen, PhD, Research Fellow in Empirical Policy Analysis at the Heritage Foundation, stated the following in his Oct. 4, 2014 article “Capital Punishment Works: It Deters Crime,” available at dailysignal.com:

“Some crimes are so heinous and inherently wrong that they demand strict penalties – up to and including life sentences or even death. Most Americans recognize this principle as just… Studies of the death penalty have reached various conclusions about its effectiveness in deterring crime. But… the majority of studies that track effects over many years and across states or counties find a deterrent effect. Indeed, other recent investigations, using a variety of samples and statistical methods, consistently demonstrate a strong link between executions and reduced murder rates… In short, capital punishment does, in fact, save lives.” Oct. 4, 2014

Michael Summers, PhD, MBA, Professor of Management Science at Pepperdine University, wrote in his Nov. 2, 2007 article “Capital Punishment Works” in the Wall Street Journal :

“[O]ur recent research shows that each execution carried out is correlated with about 74 fewer murders the following year… The study examined the relationship between the number of executions and the number of murders in the U.S. for the 26-year period from 1979 to 2004, using data from publicly available FBI sources… There seems to be an obvious negative correlation in that when executions increase, murders decrease, and when executions decrease, murders increase… In the early 1980s, the return of the death penalty was associated with a drop in the number of murders. In the mid-to-late 1980s, when the number of executions stabilized at about 20 per year, the number of murders increased. Throughout the 1990s, our society increased the number of executions, and the number of murders plummeted. Since 2001, there has been a decline in executions and an increase in murders. It is possible that this correlated relationship could be mere coincidence, so we did a regression analysis on the 26-year relationship. The association was significant at the .00005 level, which meant the odds against the pattern being simply a random happening are about 18,000 to one. Further analysis revealed that each execution seems to be associated with 71 fewer murders in the year the execution took place… We know that, for whatever reason, there is a simple but dramatic relationship between the number of executions carried out and a corresponding reduction in the number of murders.” Nov. 2, 2007

Paul H. Rubin, PhD, Professor of Economics at Emory University, wrote in his Feb. 1, 2006 testimony “Statistical Evidence on Capital Punishment and the Deterrence of Homicide” before the US Senate Judiciary Committee on the Constitution, Civil Rights, and Property Rights, available at judiciary.senate.gov:

“Recent research on the relationship between capital punishment and homicide has created a consensus among most economists who have studied the issue that capital punishment deters murder. Early studies from the 1970s and 1980s reached conflicting results. However, recent studies have exploited better data and more sophisticated statistical techniques. The modern refereed studies have consistently shown that capital punishment has a strong deterrent effect, with each execution deterring between 3 and 18 murders… The literature is easy to summarize: almost all modern studies and all the refereed studies find a significant deterrent effect of capital punishment. Only one study questions these results. To an economist, this is not surprising: we expect criminals and potential criminals to respond to sanctions, and execution is the most severe sanction available.” Feb. 1, 2006

Hashem Dezhbakhsh, PhD, Professor of Economics at Emory University, and Joanna Shepherd, PhD, Associate Professor of Law at Emory University, wrote in their July 2003 study “The Deterrent Effect of Capital Punishment: Evidence from a ‘Judicial Experiment'” in Economic Inquiry :

“[There is] strong evidence for the deterrent effect of capital punishment… Each execution results, on average, in eighteen fewer murders with a margin of error of plus or minus ten. Tests show that results are not driven by tougher sentencing laws and are robust to many alternative specifications… The results are boldly clear: executions deter murders and murder rates increase substantially during moratoriums. The results are consistent across before-and-after comparisons and regressions regardless of the data’s aggregation level, the time period, or the specific variable used to measure executions… [E]xecutions provide a large benefit to society by deterring murders.” July 2003

H. Naci Mocan, PhD, Professor and Chair of Economics at Louisiana State University, wrote in his 2003 study “Getting Off Death Row: Commuted Sentences and the Deterrent Effect of Capital Punishment” in the Journal of Law and Economics :

“Controlling for a variety of state characteristics, we investigate the impact of the execution, commutation, and removal rates, homicide arrest rate, sentencing rate, imprisonment rate, and prison death rate on the rate of homicide. The models are estimated in a number of different forms, controlling for state fixed effects, common time trends, and state-specific time trends. We find a significant relationship among the execution, removal, and commutation rates and the rate of homicide. Each additional execution decreases homicides by about five, and each additional commutation increases homicides by the same amount, while one additional removal from death row generates one additional homicide.” 2003

Cass R. Sunstein, PhD, Professor of Law at the University of Chicago, wrote in his Mar. 2005 paper “Is Capital Punishment Morally Required? The Relevance of Life-Life Tradeoffs” on papers.ssrn.com:

“[C]apital punishment may be morally required not for retributive reasons, but in order to prevent the taking of innocent lives… The foundation for our argument is a large and growing body of evidence that capital punishment may well have a deterrent effect, possibly a quite powerful one. A leading study [The Deterrent Effect of Capital Punishment: Evidence from a ‘Judicial Experiment,’ Hashem Dezhbakhsh and Joanna Shepherd, July 2003] suggests that each execution prevents some eighteen murders, on average… If the current evidence is even roughly correct, then a refusal to impose capital punishment will effectively condemn numerous innocent people to death… Contrary to widely-held beliefs, based on partial information or older studies, a wave of recent evidence suggests the possibility that capital punishment saves lives… Capital punishment may well have strong deterrent effects; there is evidence that few categories of murders are inherently un-deterrable, even so-called crimes of passion; some studies find extremely large deterrent effects; error and arbitrariness undoubtedly occur, but the evidence of deterrence suggests that prospective murderers are receiving a clear signal.” Mar. 2005

George W. Bush, MBA, 43rd President of the United States, in an Oct. 17, 2000 debate with Al Gore at Washington University, said in response to the question “Do both of you believe that the death penalty actually deters crime?”:

“I do, that’s the only reason to be for it. I don’t think you should support the death penalty to seek revenge. I don’t think that’s right. I think the reason to support the death penalty is because it saves other people’s lives.” Oct. 17, 2000

George E. Pataki, JD, 53rd Governor of New York State, in an Aug. 30, 1996 press release titled “Statement on Anniversary of Death Penalty by Governor Pataki,” stated:

“New Yorkers live in safer communities today because we are finally creating a climate that protects our citizens and causes criminals to fear arrest, prosecution and punishment. …This has occurred in part because of the strong signal that the death penalty sent to violent criminals and murderers: we won’t excuse criminals, we will punish them… I sponsored the death penalty laws because of my firm conviction that it would act as a significant deterrent and provide a true measure of justice to murder victims and their loved ones… I have every confidence that it will continue to deter murders, will continue to enhance public safety and will be enforced fairly and justly.” Aug. 30, 1996

Ernest Van Den Haag, PhD, late Professor of Jurisprudence at Fordham University, in an Oct. 17, 1983 New York Times Op-Ed article titled “For the Death Penalty,” wrote the following:

“Common sense, lately bolstered by statistics, tells us that the death penalty will deter murder, if anything can. People fear nothing more than death. Therefore, nothing will deter a criminal more than the fear of death. Death is final. But where there is life there is hope… Wherefore, life in prison is less feared. Murderers clearly prefer it to execution — otherwise, they would not try to be sentenced to life in prison instead of death. (Only an infinitesimal percentage of murderers are suicidal.) Therefore, a life sentence must be less deterrent than a death sentence. And we must execute murderers as long as it is merely possible that their execution protects citizens from future murder.” Oct. 17, 1983

Lewis Franklin Powell, Jr., LLM, late Justice of the US Supreme Court, in a June 29, 1972 Furman v. Georgia dissenting opinion, stated:

“On the basis of the literature and studies currently available, I find myself in agreement with the conclusions drawn by the Royal Commission [Report on Capital Punishment, 1949-1953] following its exhaustive study of this issue: ‘The general conclusion which we reach, after careful review of all the evidence we have been able to obtain as to the deterrent effect of capital punishment, may be stated as follows. Prima facie, the penalty of death is likely to have a stronger effect as a deterrent to normal human beings than any other form of punishment, and there is some evidence (though no convincing statistical evidence) that this is in fact so.'” June 29, 1972

Emmaline Soken-Huberty, freelance author, in an undated article, “5 Reasons Why The Death Penalty is Wrong,” accessed on Sep. 2, 2021 and available at humanrightscareers.com, stated:

“The fact that it doesn’t prevent crime may be the most significant reason why the death penalty is wrong. Many people might believe that while the death penalty isn’t ideal, it’s worth it if it dissuades potential criminals. However, polls show people don’t think capital punishment does that. The facts support that view. The American South has the highest murder rate in the country and oversees 81% of the nation’s executions. In states without the death penalty, the murder rate is much lower. There are other factors at play, but the fact remains that no studies show that capital punishment is a deterrent. If the death penalty is not only inhumane, discriminatory, and arbitrary, but it often claims innocent lives and doesn’t even prevent crime, then why should it still exist? It’s disappearing from legal systems around the world, so it’s time for all nations (like the United States) to end it.” Sep. 2, 2021

Craig Trocino, JD, Director of the Innocence Clinic at the University of Miami School of Law, as quoted by Robert C. Jones Jr. in an Aug. 8, 2019 article, “The Impact of Reviving the Federal Death Penalty,” available at news.miami.edu, stated:

“The death penalty is not a deterrent despite the claims of its proponents. In 2012 the National Research Council concluded that the studies claiming it is a deterrence were fundamentally flawed. Additionally, a 2009 study of criminologists concluded that 88 percent of criminologists did not believe in the death penalties deterrence while only 5 percent did. Perhaps the most consistent and interesting data that the death penalty is not a deterrence is to look at the murder rates of states that do not have the death penalty in comparison to those that do. In states that have recently abolished the death penalty, there has been no increase in murder rates. In fact, since 1990 states without the death penalty have consistently had lower murder rates than states that have it.” Aug. 8, 2019

Nick Petersen, PhD, Assistant Professor of Sociology and Law at the University of Miami, as quoted by Robert C. Jones Jr. in an Aug. 8, 2019 article, “The Impact of Reviving the Federal Death Penalty,” available at news.miami.edu, stated:

“Social science research does not support the contention that the death penalty deters crime. In 1978, the National Research Council, one of the most prestigious scientific institutions in the nation and world, noted that “available studies provide no useful evidence on the deterrent effect of capital punishment.” A 2012 report by the National Research Council reached a similar conclusion. Citing a number of problems with deterrence research, the council reported that “claims that research demonstrates that capital punishment decreases or increases the homicide rate by a specified amount or has no effect on the homicide rate should not influence policy judgments about capital punishment.” Aug. 8, 2019

John J. Donohue III, JD, PhD, Professor of Law at Stanford University, stated the following in his Aug. 8, 2015 article “There’s No Evidence That Death Penalty Is a Deterrent against Crime,” available at theconversation.com:

“[T]here is not the slightest credible statistical evidence that capital punishment reduces the rate of homicide. Whether one compares the similar movements of homicide in Canada and the US when only the latter restored the death penalty, or in American states that have abolished it versus those that retain it, or in Hong Kong and Singapore (the first abolishing the death penalty in the mid-1990s and the second greatly increasing its usage at the same), there is no detectable effect of capital punishment on crime. The best econometric studies reach the same conclusion… [L]ast year roughly 14,000 murders were committed but only 35 executions took place. Since murderers typically expose themselves to far greater immediate risks, the likelihood is incredibly remote that some small chance of execution many years after committing a crime will influence the behaviour of a sociopathic deviant who would otherwise be willing to kill if his only penalty were life imprisonment. Any criminal who actually thought he would be caught would find the prospect of life without parole to be a monumental penalty. Any criminal who didn’t think he would be caught would be untroubled by any sanction.” Aug. 8, 2015

H. Lee Sarokin, LLB, former US District Court and US Court of Appeals Judge, wrote in his Jan. 15, 2011 article “Is It Time to Execute the Death Penalty?” on the Huffington Post website:

“In my view deterrence plays no part whatsoever. Persons contemplating murder do not sit around the kitchen table and say I won’t commit this murder if I face the death penalty, but I will do it if the penalty is life without parole. I do not believe persons contemplating or committing murder plan to get caught or weigh the consequences. Statistics demonstrate that states without the death penalty have consistently lower murder rates than states with it, but frankly I think those statistics are immaterial and coincidental. Fear of the death penalty may cause a few to hesitate, but certainly not enough to keep it in force.” Jan. 15, 2011

Michael L. Radelet, PhD, Sociology Professor and Department Chair at the University of Colorado-Boulder, wrote in his 2009 article “Do Executions Lower Homicide Rates?: The Views of Leading Criminologists” in the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology :

“Our survey indicates that the vast majority of the world’s top criminologists believe that the empirical research has revealed the deterrence hypothesis for a myth… 88.2% of polled criminologists do not believe that the death penalty is a deterrent… 9.2% answered that the statement ‘[t]he death penalty significantly reduces the number of homicides’ was accurate… Overall, it is clear that however measured, fewer than 10% of the polled experts believe the deterrence effect of the death penalty is stronger than that of long-term imprisonment… Recent econometric studies, which posit that the death penalty has a marginal deterrent effect beyond that of long-term imprisonment, are so limited or flawed that they have failed to undermine consensus. In short, the consensus among criminologists is that the death penalty does not add any significant deterrent effect above that of long-term imprisonment.” 2009

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), in its Apr. 9, 2007 website presentation titled “The Death Penalty: Questions and Answers,” offered the following:

“The death penalty has no deterrent effect. Claims that each execution deters a certain number of murders have been thoroughly discredited by social science research. People commit murders largely in the heat of passion, under the influence of alcohol or drugs, or because they are mentally ill, giving little or no thought to the possible consequences of their acts. The few murderers who plan their crimes beforehand — for example, professional executioners — intend and expect to avoid punishment altogether by not getting caught. Some self-destructive individuals may even hope they will be caught and executed.” Apr. 9, 2007

Jimmy Carter, 39th President of the United States, wrote in his Apr. 25, 2012 article “Show Death Penalty the Door” on the website of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution :

“One argument for the death penalty is that it is a strong deterrent to murder and other violent crimes. In fact, evidence shows just the opposite. The homicide rate is at least five times greater in the United States than in any Western European country, all without the death penalty. Southern states carry out more than 80 percent of the executions but have a higher murder rate than any other region. Texas has by far the most executions, but its homicide rate is twice that of Wisconsin, the first state to abolish the death penalty. Look at similar adjacent states: There are more capital crimes in South Dakota, Connecticut and Virginia (with death sentences) than neighboring North Dakota, Massachusetts and West Virginia (without death penalties). Furthermore, there has never been any evidence that the death penalty reduces capital crimes or that crimes increased when executions stopped.” Apr. 25, 2012

John Lamperti, PhD, Professor Emeritus of Mathematics at Dartmouth College, wrote in his Mar. 2010 paper “Does Capital Punishment Deter Murder? A Brief Look at the Evidence,” published at math.dartmouth.edu:

“[I]f there were a substantial net deterrent effect from capital punishment under modern U.S. conditions, the studies we have surveyed should clearly reveal it. They do not… If executions protected innocent lives through deterrence, that would weigh in the balance against capital punishment’s heavy social costs. But despite years of trying, this benefit has not been proven to exist; the only certain effects of capital punishment are its liabilities.” Mar. 2010

Tomislav Kovandzic, PhD, Associate Professor of Economic, Political, and Policy Sciences at the University of Texas at Dallas, wrote in his 2009 paper “Does the Death Penalty Save Lives?” in Criminology and Public Policy :

“Our results provide no empirical support for the argument that the existence or application of the death penalty deters prospective offenders from committing homicide… Although policymakers and the public can continue to base support for use of the death penalty on retribution, religion, or other justifications, defending its use based solely on its deterrent effect is contrary to the evidence presented here. At a minimum, policymakers should refrain from justifying its use by claiming that it is a deterrent to homicide and should consider less costly, more effective ways of addressing crime.” 2009

Jeffrey A. Fagan, PhD, Professor of Law and Epidemiology at Columbia University, said in his Feb. 1, 2006 testimony “Deterrence and the Death Penalty: Risk, Uncertainty, and Public Policy Choices” published on the website of the US Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights and Property Rights:

“Recent studies claiming that executions reduce crime… fall apart under close scrutiny. These new studies are fraught with numerous technical and conceptual errors: inappropriate methods of statistical analysis, failures to consider all the relevant factors that drive crime rates, missing data on key variables in key states, the tyranny of a few outlier states and years, weak to non-existent tests of concurrent effects of incarceration, statistical confounding of murder rates with death sentences, failure to consider the general performance of the criminal justice system… and the absence of any direct test of deterrence. These studies fail to reach the demanding standards of social science to make such strong claims… Social scientists have failed to replicate several of these studies, and in some cases have produced contradictory results with the same data, suggesting that the original findings are unstable, unreliable and perhaps inaccurate. This evidence, together with some simple examples and contrasts… suggest that there is little evidence that the death penalty deters crime.” Feb. 1, 2006

John J. Donahue III, JD, PhD, Professor of Law at Stanford University, wrote in his Dec. 2005 article “Uses and Abuses of Empirical Evidence in the Death Penalty Debate” in the Stanford Law Review :

“Does the death penalty save lives? [T]he death penalty – at least as it has been implemented in the United States – is applied so rarely that the number of homicides that it can plausibly have caused or deterred cannot be reliably disentangled from the large year-to-year changes in the homicide rate caused by other factors. As such, short samples and particular specifications may yield large but spurious correlations. We conclude that existing estimates appear to reflect a small and unrepresentative sample of the estimates that arise from alternative approaches. Sampling from the broader universe of plausible approaches suggests… reasonable doubt about whether there is any deterrent effect of the death penalty… There are serious questions about whether anything useful about the deterrent value of the death penalty can ever be learned from… the data that are likely to be available.” Dec. 2005

People who view this page may also like:

- States with the Death Penalty and States with Death Penalty Bans

- US Executions by Race, Crime, Method, Age, Gender, State, & Year

- Should Euthanasia or Physician-Assisted Suicide Be Legal?

ProCon/Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. 325 N. LaSalle Street, Suite 200 Chicago, Illinois 60654 USA

Natalie Leppard Managing Editor [email protected]

© 2023 Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved

- History of the Death Penalty

- Top Pro & Con Quotes

- Historical Timeline

- Did You Know?

- States with the Death Penalty, Death Penalty Bans, and Death Penalty Moratoriums

- The ESPY List: US Executions 1608-2002

- Federal Capital Offenses

- Death Row Inmates

- Critical Thinking Video Series: Thomas Edison Electrocutes Topsy the Elephant, Jan. 4, 1903

Cite This Page

- Artificial Intelligence

- Private Prisons

- Space Colonization

- Social Media

- Death Penalty

- School Uniforms

- Video Games

- Animal Testing

- Gun Control

- Banned Books

- Teachers’ Corner

ProCon.org is the institutional or organization author for all ProCon.org pages. Proper citation depends on your preferred or required style manual. Below are the proper citations for this page according to four style manuals (in alphabetical order): the Modern Language Association Style Manual (MLA), the Chicago Manual of Style (Chicago), the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (APA), and Kate Turabian's A Manual for Writers of Term Papers, Theses, and Dissertations (Turabian). Here are the proper bibliographic citations for this page according to four style manuals (in alphabetical order):

[Editor's Note: The APA citation style requires double spacing within entries.]

[Editor’s Note: The MLA citation style requires double spacing within entries.]

Capital Punishment and Deterrence of Crime Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Works cited.

Capital punishment can deter crime. Many individuals oppose the death penalty because of moral and aesthetic reasons. The problem with these justifications is that they are susceptible to subjective interpretations. An economic analysis of the deterrence effect of capital punishment provides a rational and objective way of analyzing the effectiveness of such a mechanism. In this paper, it will be argued that offenders are likely to respond to the incentives offered by law enforcers concerning the commissioning of crimes.

Murder is usually committed as a result of some interpersonal conflicts or due to jealousy, hate and pecuniary motives. Sometimes, it may be a product of property crimes (when a criminal tries to eliminate potential witnesses or officers who may hold him accountable for his actions).

The propensity to commit murder (which is usually the main crime that necessitates the use of capital punishment) is indeed influenced by the losses and gains that can come from their commission (Mocan & Gittings 470). Most murders are committed against people who know each other or persons who have a relative degree of familiarity with one another. In economics, a person’s utility is affected by that person’s utility as well as the utility of other persons.

Utility is usually constrained by the resource endowments of the affected parties and also by the transfer functions. It is also affected by the penalties and awards that may result from transfer functions as well as the degrees of uncertainty created by these differences. For the case of murder or crimes that necessitate capital punishment, the incentive to commit murder is directly related to the uncertainties that punishments for the crime will generate.

When a person commits a murder, he/she will have to go through certain direct costs that include the planning and the execution of the crime. The offender will have to bear risks that will emanate from the punishment and conviction of the crime. If it is assumed that the offender behaves in order to maximize his expected utility, then the expected utility from the capital crime should be greater than the one that will come from another alternative course of action.

The probability of committing the crime and getting away with it will be the greatest incentive to commit it. The probability of committing the crime and getting a less severe crime is also another possibility. Alternatively, the offender may get caught and receive the harshest punishment, i.e. the death penalty. A criminal will consider these alternatives prior to commission of the crime.

If a deterrent effect is great, the probability of committing the crime is minimized (Alper and Daryl 44). In other words, the more undesirable the consequences of the crime, the more likely a criminal will avoid doing it, based on his subjective analyses. Thus, the greater the severity of punishment, the lower the expected utility for committing a murder. It means that capital punishment, which meets the threshold for highly severe punishments, will decrease the expected utility and reduce the propensity to commit crime.

There are a lot of evidences to support the findings stated above. First of all, a look at murder rates in states that support capital punishment over the years adds a practical dimension to this component.

It was found that murder rates in states that accept capital punishment have been reducing during the period 1970-1990 (Shepherd 15). This is only true after controlling for factors such as labor market opportunities, race, age and sex composition in those states. It should be noted that if these factors are not included, then it would be incorrectly assumed that capital punishment actually increases crime rates.

Researches carried out by Dezhbakhsh et al. (2003) have revealed that executions do indeed deter crimes. This study was done through a cross sectional analysis of crime data from a number of states following certain executions. It was found that crimes tended to decrease when executions were done and they went up when this was not true.

Department of Justice data were used for the paper. Trends in crime were analyzed in the exact period when the executions occurred. Additionally, the paper considered the effect of commutations on the implementation of crime. Murder arrest rates and death sentence rates were analyzed. It was found that there was a relationship between the two.

This implies that the higher the death sentences, the lower the murder rates. These facts hold true for persons who commit crimes of passion and for premeditated types of crime. However, death row waits have a negative effect on crime because they tend to increase it. Other famous economists, such as Dezhbakhsh, Hashem, Rubin, Paul and Shepherd (370), have also found thorough econometric analysis that for every execution that is done the country will witness eighteen murders less.

A number of other economic arguments have been made against capital punishments. For instance, it has been argued that death sentences may end up punishing an innocent person with very severe actions. However, when one carries out an economic analysis of this assertion, one would realize that the argument remains invalid. A number of people who are convicted for crimes that they did not commit are quite small.

This is especially the case because capital litigations for the crimes are quite lengthy. Most individuals tend to spend in death row approximately ten years. Consequently, the possibilities of catching a false accusation are quite high in those ten years. The execution delay minimizes the possibility of punishing the wrong person for a crime.

This means that arguments made against the ability of capital punishment to deter crimes based on this notion are indeed exaggerated. Furthermore, the country tends to dedicate a lot of resources in the litigation of cases that involve death sentences, as compared to others that involve less severe punishment. This intensity of litigation further minimizes the error rates that may emanate from the sentences that have been passed (Ehrlich 40).

One cannot look at the plausibility of the death penalty without consideration of the costs implications. It is important to compare what such cases entail to determine whether it would be more effective to use other deterrence measures. The next best judgment for capital crimes would be life without parole.

| For 50yrs, 2% annual cost increase (Starts at 34,500/yr for death and 60,000 for life without parole) | 3.01 Million | 1.88 Million |

| For 50 yrs, 3%, annual cost increase | 4.04 Million | 1.89 Million |

| For 50yrs, 4% annual cost increase | 1.91 Million | 5.53 Million |

As it can be seen from the above analysis, life without parole is more costly than capital punishment. However, one must do a long term analysis on the same case. It is accepted that the upfront costs for death sentences are too high.

The figures mentioned above are the average cell costs for keeping a person in maximum security cells; in other words, states spend approximately $24,000 annually to keep a person in prison for a capital crime. However, it has been shown that these are indeed conservative estimates. Other studies show that the average figure should be $34,200 for maximum security cells.

Conversely, death row inmates cost the government approximately 60,000 per year. Most of them will stay incarcerated for six to ten years. Therefore, the differences in costs will be mitigated by their short length of stay for death row inmates. A number of arguments against the effectiveness of capital punishments have focused on the upfront costs. However, there are a lot of problems when one looks at another alternative with life imprisonment without parole.

Since the country spends substantial portions on the alternative to capital punishment, it is not economically feasible to follow such a path. Deterrence effects should be analyzed on the basis of their cost effectiveness because it would not be wise to continue using such a method when it is not economically sustainable. This means that the death penalty is an effective deterrent when financial implications are considered.

Capital punishment is an effective deterrent against crime because of basis economic principles. First, it reduces expected utility of commission of a crime. An offender would reconsider his actions if the incentives given are diminished. The severity of capital punishment substantially reduces expected utility and therefore deters crime.

Furthermore, statistical evidence points to these findings. It has been shown that states that punish criminals using capital punishment have lower murder rates after controlling for age, sex, race and other related factors. Other direct analyses of death sentences versus crime rates have shown a decrease in crimes after death sentences. Some have stated that one death sentence deters 18 murders. Additionally, death penalties are more sustainable financially, so they will have a greater chance of punishing future crimes.

Alper, Neil and Hellman, Daryl. The Economics of Crime: A Reader . NY: Simon and Schuster Custom publishing, 1997. Print.

Dezhbakhsh, Hashem, Rubin, Paul and Shepherd Joanna. “Does Capital Punishment Have a Deterrent Effect: New Evidence from Postmaratorium Panel Data.” American Law Economic Review 5.2 (2003): 344-376. Print.

Ehrlich, Isaac. “The Deterrent Effect of Capital Punishment: A Question of Life and Death.” The American economic review 65.3 (1975): 397-417. Print.

Mocan, Naci & Gittings, Kaj. “Getting off Death Row: Commuted Sentences and the Deterrent Effect of Capital Punishment.” Journal of law and economics 46 (2003): 453-479. Print.

Shepherd, Joanna. Murders of Passion, Execution Delays, and the Deterrence of Capital Punishment. Clemson University Working Paper, 2003. Print.

- Sexual Assaults Against Children: With Adult and Juvenile Offenders

- Immorality Of Human Execution By The State

- Ways of Punishing Offenders

- Parole system in the United States

- Punishment From the Crime Committed Perspective

- Child Abuse: A Case for Imposing Harsher Punishments to Child Abusers

- Avoiding of Capital Punishment

- The Social Downfall of Salinas Gangs

- Sexual Violence Against Women: Rape

- Miranda v. Arizona (Self-incrimination)

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, October 19). Capital Punishment and Deterrence of Crime. https://ivypanda.com/essays/capital-punishment-and-deterrence-of-crime/

"Capital Punishment and Deterrence of Crime." IvyPanda , 19 Oct. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/capital-punishment-and-deterrence-of-crime/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Capital Punishment and Deterrence of Crime'. 19 October.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Capital Punishment and Deterrence of Crime." October 19, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/capital-punishment-and-deterrence-of-crime/.

1. IvyPanda . "Capital Punishment and Deterrence of Crime." October 19, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/capital-punishment-and-deterrence-of-crime/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Capital Punishment and Deterrence of Crime." October 19, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/capital-punishment-and-deterrence-of-crime/.

The Death Penalty: Questions and Answers

Download a PDF version of Death Penalty Questions and Answers >>

Since our nation's founding, the government -- colonial, federal, and state -- has punished a varying percentage of arbitrarily-selected murders with the ultimate sanction: death.

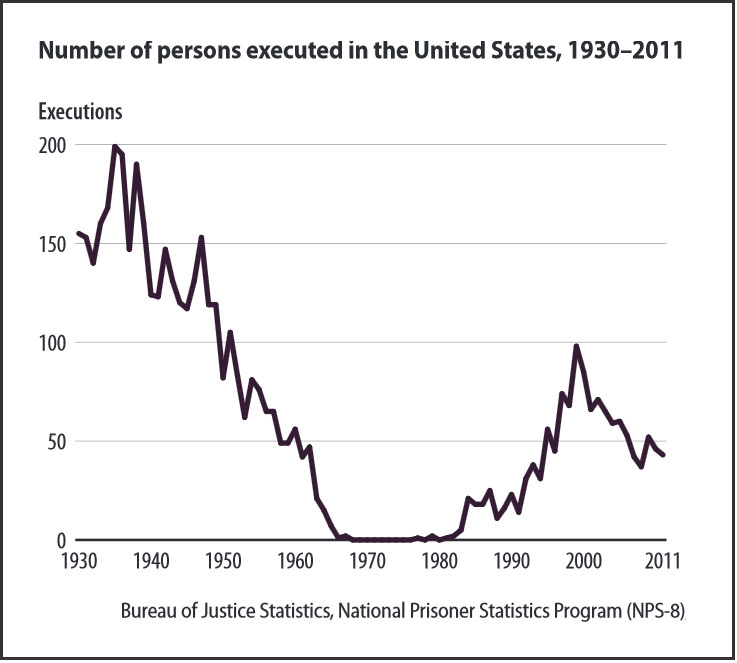

More than 14,000 people have been legally executed since colonial times, most of them in the early 20th Century. By the 1930s, as many as 150 people were executed each year. However, public outrage and legal challenges caused the practice to wane. By 1967, capital punishment had virtually halted in the United States, pending the outcome of several court challenges.

In 1972, in Furman v. Georgia , the Supreme Court invalidated hundreds of death sentences, declaring that then existing state laws were applied in an "arbitrary and capricious" manner and, thus, violated the Eighth Amendment's prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment, and the Fourteenth Amendment's guarantees of equal protection of the laws and due process. But in 1976, in Gregg v. Georgia , the Court resuscitated the death penalty: It ruled that the penalty "does not invariably violate the Constitution" if administered in a manner designed to guard against arbitrariness and discrimination. Several states promptly passed or reenacted capital punishment laws.

Today, states have laws authorizing the death penalty, as does the military and the federal government. Several states in the Midwest and Northeast have abolished capital punishment. Alaska and Hawaii have never had the death penalty. The vast majority of executions have taken place in 10 states from the South and over 35% have occurred in Texas. In 2004, the high courts of Kansas and New York struck down their death penalty statutes as unconstitutional and the legislatures have yet to reinstate them.

Today, about 3,350 people are on "death row." Virtually all are poor, a significant number are mentally disabled, more than 40 percent are African American, and a disproportionate number are Native American, Latino, and Asian.

The ACLU believes that, in all circumstances, the death penalty is unconstitutional under the Eighth Amendment. We also believe that the death penalty continues to be applied in an arbitrary and discriminatory manner in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Frequently Asked Questions raised by the public about Capital Punishment Q : Doesn't the Death Penalty deter crime, especially murder? A : No, there is no credible evidence that the death penalty deters crime more effectively than long terms of imprisonment. States that have death penalty laws do not have lower crime rates or murder rates than states without such laws. And states that have abolished capital punishment show no significant changes in either crime or murder rates.

The death penalty has no deterrent effect. Claims that each execution deters a certain number of murders have been thoroughly discredited by social science research. People commit murders largely in the heat of passion, under the influence of alcohol or drugs, or because they are mentally ill, giving little or no thought to the possible consequences of their acts. The few murderers who plan their crimes beforehand -- for example, professional executioners -- intend and expect to avoid punishment altogether by not getting caught. Some self-destructive individuals may even hope they will be caught and executed.

Death penalty laws falsely convince the public that government has taken effective measures to combat crime and homicide. In reality, such laws do nothing to protect us or our communities from the acts of dangerous criminals.

Q : Don't murderers deserve to die? A : No one deserves to die. When the government metes out vengeance disguised as justice, it becomes complicit with killers in devaluing human life and human dignity. In civilized society, we reject the principle of literally doing to criminals what they do to their victims: The penalty for rape cannot be rape, or for arson, the burning down of the arsonist's house. We should not, therefore, punish the murderer with death.

Q : If execution is unacceptable, what is the alternative? A : INCAPACITATION. Convicted murderers can be sentenced to life imprisonment, as they are in many countries and states that have abolished the death penalty. Most state laws allow life sentences for murder that severely limit or eliminate the possibility of parole. Today, 37 states allow juries to sentence defendants to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole instead of the death penalty.

Several recent studies of public attitudes about crime and punishment found that a majority of Americans support alternatives to capital punishment: When people were presented with the facts about several crimes for which death was a possible punishment, a majority chose life imprisonment without parole as an appropriate alternative to the death penalty (see PA., 2007 ).

Q : Isn't the Death Penalty necessary as just retribution for victims' families? A : No. "Reconciliation means accepting you can't undo the murder; but you can decide how you want to live afterwards" ( Murder Victims' Families for Reconciliation, Inc. )

Q : Have strict procedures eliminated arbitrariness and discrimination in death sentencing? A : No. Poor people are also far more likely to be death sentenced than those who can afford the high costs of private investigators, psychiatrists, and expert criminal lawyers. Indeed, capital punishment is "a privilege of the poor," said Clinton Duffy, former warden at California's San Quentin Prison. Some observers have pointed out that the term "capital punishment" is ironic because "only those without capital get the punishment."

Furthermore, study after study has found serious racial disparities in the charging, sentencing and imposition of the death penalty. People who kill whites are far more likely to receive a death sentence than those whose victims were not white, and blacks who kill whites have the greatest chance of receiving a death sentence.

Minorities are death-sentenced disproportionate to their numbers in the population. This is not primarily because minorities commit more murders, but because they are more often sentenced to death when they do.

Q : Maybe it used to happen that innocent people were mistakenly executed, but hasn't that possibility been eliminated? A : No. Since 1973, 123 people in 25 states have been released from death row because they were not guilty. In addition, seven people have been executed even though they were probably innocent. A study published in the Stanford Law Review documents 350 capital convictions in this century, in which it was later proven that the convict had not committed the crime. Of those, 25 convicts were executed while others spent decades of their lives in prison. Fifty-five of the 350 cases took place in the 1970s, and another 20 of them between l980 and l985.

Our criminal justice system cannot be made fail-safe because it is run by human beings, who are fallible. Executions of innocent persons occur.

Q : Only the worst criminals get sentenced to death, right? A : Wrong. Although it is commonly thought that the death penalty is reserved for those who commit the most heinous crimes, in reality only a small percentage of death-sentenced inmates were convicted of unusually vicious crimes. The vast majority of individuals facing execution were convicted of crimes that are indistinguishable from crimes committed by others who are serving prison sentences, crimes such as murder committed in the course of an armed robbery.

The death penalty is like a lottery, in which fairness always loses. Who gets the death penalty is largely determined, not by the severity of the crime, but by: the race, sex, and economic class of the prisoner and victim; geography -- some states have the death penalty, others do not, within the states that do some counties employ it with great frequency and others do not; the quality of defense counsel and vagaries in the legal process.

Q : "Cruel and unusual punishment" -- those are strong words, but aren't executions relatively swift and painless? A : No execution is painless, whether botched or not, and all executions are certainly cruel. The history of capital punishment is replete with examples of botched executions.

Lethal injection is the latest technique, first used in Texas in l982, and now mandated by law in a large majority of states that retain capital punishment. Although this method is defended as more humane, efficient, and inexpensive than others, one federal judge observed that even "a slight error in dosage or administration can leave a prisoner conscious but paralyzed while dying, a sentient witness of his or her own asphyxiation." In Texas, there have been three botched injection executions since 1985. In other states, dozens of botched executions have occurred, leading to suspensions of executions in Florida, California, and other states.

In 2006, it took the Florida Department of Corrections 34 minutes to execute inmate Angel Nieves Diaz by way of lethal injection, usually a 15 minute procedure. During the execution, Diaz appeared to be in pain and gasped for air for more than 11 minutes. He was given a rare second dose of lethal chemicals after the execution team observed that the first round did not kill him. A medical examiner reported the second dose was needed because the needles were incorrectly inserted through his veins and into the flesh in his arms. Not only did Diaz die a slow and excruciating death because the drugs were not delivered into his veins properly, his autopsy revealed that he suffered 12 inch chemical burns in his arms by the highly concentrated drugs flowing under his skin.

More recently, an Ohio inmate did not die when his injections were incorrectly administered. Minutes into the execution, he raised his head and said, "It don't work, it don't work."

Eyewitness accounts confirm that execution by lethal injection and other means is often an excruciatingly painful, and always degrading, process that ends in death.

Capital punishment is a barbaric remnant of uncivilized society. It is immoral in principle, and unfair and discriminatory in practice. It assures the execution of some innocent people. As a remedy for crime, it has no purpose and no effect. Capital punishment ought to be abolished now.

Related Issues

- Capital Punishment

- Mass Incarceration

- Smart Justice

Stay Informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU’s privacy statement.

- University of Pennsylvania

- School of Arts and Sciences

- Penn Calendar

Search form

Does the Death Penalty Deter Crime?

Richard Berk

There have been claims for decades that in the United States the death penalty serves as a deterrent. When there are executions, violent crime decreases. But there have also been claims that executions “brutalize” society because government agencies diminish respect for life when the death penalty is applied. With brutalization comes an increase in violent crime, and especially homicides. Both sides assert that there is credible research supporting their position. In fact, a committee of the National Research Council has concluded that existing studies are far too methodologically flawed to draw conclusions one way or another. Neither side can maintain that they have empirical support. In most years, most states execute no one, and that pattern seems to be on the rise. One cannot study the impact of executions when they are hardly ever imposed, and it is difficult to separate any impact of the death penalty from the large number of other factors that affect the amount and kinds of crime. The committee’s conclusion about the claim that the death penalty deters is “can’t tell.”

Daniel Nagin and John Pepper (eds.) (2012) Deterrence and the Death Penalty , The National Academies Press ( https://www.nap.edu/catalog/13363/deterrence-and-the-death-penalty )

- Capital Punishment: Our Duty or Our Doom?

- Markkula Center for Applied Ethics

- Focus Areas

- More Focus Areas

Capital Punishment:Our Duty or Our Doom?

But human rights advocates and civil libertarians continue to decry the immorality of state-sanctioned killing in the U.S. Is capital punishment moral?

About 2000 men, women, and teenagers currently wait on America's "death row." Their time grows shorter as federal and state courts increasingly ratify death penalty laws, allowing executions to proceed at an accelerated rate. It's unlikely that any of these executions will make the front page, having become more or less a matter of routine in the last decade. Indeed, recent public opinion polls show a wide margin of support for the death penalty. But human rights advocates and civil libertarians continue to decry the immorality of state-sanctioned killing in the U.S., the only western industrialized country that continues to use the death penalty. Is capital punishment moral?

Capital punishment is often defended on the grounds that society has a moral obligation to protect the safety and welfare of its citizens. Murderers threaten this safety and welfare. Only by putting murderers to death can society ensure that convicted killers do not kill again.

Second, those favoring capital punishment contend that society should support those practices that will bring about the greatest balance of good over evil, and capital punishment is one such practice. Capital punishment benefits society because it may deter violent crime. While it is difficult to produce direct evidence to support this claim since, by definition, those who are deterred by the death penalty do not commit murders, common sense tells us that if people know that they will die if they perform a certain act, they will be unwilling to perform that act.

If the threat of death has, in fact, stayed the hand of many a would be murderer, and we abolish the death penalty, we will sacrifice the lives of many innocent victims whose murders could have been deterred. But if, in fact, the death penalty does not deter, and we continue to impose it, we have only sacrificed the lives of convicted murderers. Surely it's better for society to take a gamble that the death penalty deters in order to protect the lives of innocent people than to take a gamble that it doesn't deter and thereby protect the lives of murderers, while risking the lives of innocents. If grave risks are to be run, it's better that they be run by the guilty, not the innocent.

Finally, defenders of capital punishment argue that justice demands that those convicted of heinous crimes of murder be sentenced to death. Justice is essentially a matter of ensuring that everyone is treated equally. It is unjust when a criminal deliberately and wrongly inflicts greater losses on others than he or she has to bear. If the losses society imposes on criminals are less than those the criminals imposed on their innocent victims, society would be favoring criminals, allowing them to get away with bearing fewer costs than their victims had to bear. Justice requires that society impose on criminals losses equal to those they imposed on innocent persons. By inflicting death on those who deliberately inflict death on others, the death penalty ensures justice for all.

This requirement that justice be served is not weakened by charges that only the black and the poor receive the death penalty. Any unfair application of the death penalty is the basis for extending its application, not abolishing it. If an employer discriminates in hiring workers, do we demand that jobs be taken from the deserving who were hired or that jobs be abolished altogether? Likewise, if our criminal justice system discriminates in applying the death penalty so that some do not get their deserved punishment, it's no reason to give Iesser punishments to murderers who deserved the death penalty and got it. Some justice, however unequal, is better than no justice, however equal. To ensure justice and equality, we must work to improve our system so that everyone who deserves the death penalty gets it.

The case against capital punishment is often made on the basis that society has a moral obligation to protect human life, not take it. The taking of human life is permissible only if it is a necessary condition to achieving the greatest balance of good over evil for everyone involved. Given the value we place on life and our obligation to minimize suffering and pain whenever possible, if a less severe alternative to the death penalty exists which would accomplish the same goal, we are duty-bound to reject the death penalty in favor of the less severe alternative.

There is no evidence to support the claim that the death penalty is a more effective deterrent of violent crime than, say, life imprisonment. In fact, statistical studies that have compared the murder rates of jurisdictions with and without the death penalty have shown that the rate of murder is not related to whether the death penalty is in force: There are as many murders committed in jurisdictions with the death penalty as in those without. Unless it can be demonstrated that the death penalty, and the death penalty alone, does in fact deter crimes of murder, we are obligated to refrain from imposing it when other alternatives exist.

Further, the death penalty is not necessary to achieve the benefit of protecting the public from murderers who may strike again. Locking murderers away for life achieves the same goal without requiring us to take yet another life. Nor is the death penalty necessary to ensure that criminals "get what they deserve." Justice does not require us to punish murder by death. It only requires that the gravest crimes receive the severest punishment that our moral principles would allow us to impose.

While it is clear that the death penalty is by no means necessary to achieve certain social benefits, it does, without a doubt, impose grave costs on society. First, the death penalty wastes lives. Many of those sentenced to death could be rehabilitated to live socially productive lives. Carrying out the death penalty destroys any good such persons might have done for society if they had been allowed to live. Furthermore, juries have been known to make mistakes, inflicting the death penalty on innocent people. Had such innocent parties been allowed to live, the wrong done to them might have been corrected and their lives not wasted.

In addition to wasting lives, the death penalty also wastes money. Contrary to conventional wisdom, it's much more costly to execute a person than to imprison them for life. The finality of punishment by death rightly requires that great procedural precautions be taken throughout all stages of death penalty cases to ensure that the chance of error is minimized. As a result, executing a single capital case costs about three times as much as it costs to keep a person in prison for their remaining life expectancy, which is about 40 years.

Finally, the death penalty harms society by cheapening the value of life. Allowing the state to inflict death on certain of its citizens legitimizes the taking of life. The death of anyone, even a convicted killer, diminishes us all. Society has a duty to end this practice which causes such harm, yet produces little in the way of benefits.

Opponents of capital punishment also argue that the death penalty should be abolished because it is unjust. Justice, they claim, requires that all persons be treated equally. And the requirement that justice bc served is all the more rigorous when life and death are at stake. Of 19,000 people who committed willful homicides in the U.S. in 1987, only 293 were sentenced to death. Who are these few being selected to die? They are nearly always poor and disproportionately black. It is not the nature of the crime that determines who goes to death row and who doesn't. People go to death row simply because they have no money to appeal their case, or they have a poor defense, or they lack the funds to being witnesses to courts, or they are members of a political or racial minority.

The death penalty is also unjust because it is sometimes inflicted on innocent people. Since 1900, 350 people have been wrongly convicted of homicide or capital rape. The death penalty makes it impossible to remedy any such mistakes. If, on the other hand, the death penalty is not in force, convicted persons later found to be innocent can be released and compensated for the time they wrongly served in prison.

The case for and the case against the death penalty appeal, in different ways, to the value we place on life and to the value we place on bringing about the greatest balance of good over evil. Each also appeals to our commitment to"justice": Is justice to be served at all costs? Or is our commitment to justice to be one tempered by our commitment to equality and our reverence for life? Indeed, is capital punishment our duty or our doom?

(Capital punishment) is . . . the most premeditated of murders, to which no criminal's deed, however calculated . . can be compared . . . For there to be an equivalence, the death penalty would have to punish a criminal who had warned his victim of the date at which he would inflict a horrible death on him and who, from that moment onward, had confined him at mercy for months. Such a monster is not encountered in private life. --Albert Camus

If . . . he has committed a murder, he must die. In this case, there is no substitute that will satisfy the requirements of legal justice. There is no sameness of kind between death and remaining alive even under the most miserable conditions, and consequently there is no equality between the crime and the retribution unless the criminal is judicially condemned and put to death. --Immanuel Kant

For further reading:

Hugo Adam Bedau, Death Is Different: Studies in the Morality, Law, and Politics of Capital Punishment (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1987).

Walter Berns, For Capital Punishment (New York: Basic Books, 1979.)

David Bruch, "The Death Penalty: An Exchange," The New Republic , Volume 192 (May 20, 1985), pp. 20-21.

Edward I. Koch, "Death and Justice: How Capital Punishment Affirms Life," The New Republic, Volume 192 (April 15,1985), pp. 13-15.

Ernest van den Haag and John P. Conrad , The Death Penalty: A Debate (New York: Plenum Press, 1983).

This article was originally published in Issues in Ethics - V. 1, N.3 Spring 1988

While free speech is a right that has been embraced in the United States for several centuries, ethical issues about the process and limitations of free speech and protest behavior, like some of those seen on college campuses this Spring, are in question and are debatable.

Stockholders pay the price when executives and directors choose profits over ethics.

On Communications, Creativity, and Generative AI

Our social media posts are being turned into training data for generative AI models.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Does Death Penalty Save Lives? A New Debate

By Adam Liptak

- Nov. 18, 2007

For the first time in a generation, the question of whether the death penalty deters murders has captured the attention of scholars in law and economics, setting off an intense new debate about one of the central justifications for capital punishment.

According to roughly a dozen recent studies, executions save lives. For each inmate put to death, the studies say, 3 to 18 murders are prevented.

The effect is most pronounced, according to some studies, in Texas and other states that execute condemned inmates relatively often and relatively quickly.

The studies, performed by economists in the past decade, compare the number of executions in different jurisdictions with homicide rates over time — while trying to eliminate the effects of crime rates, conviction rates and other factors — and say that murder rates tend to fall as executions rise. One influential study looked at 3,054 counties over two decades.

“I personally am opposed to the death penalty,” said H. Naci Mocan, an economist at Louisiana State University and an author of a study finding that each execution saves five lives. “But my research shows that there is a deterrent effect.”

The studies have been the subject of sharp criticism, much of it from legal scholars who say that the theories of economists do not apply to the violent world of crime and punishment. Critics of the studies say they are based on faulty premises, insufficient data and flawed methodologies.

The death penalty “is applied so rarely that the number of homicides it can plausibly have caused or deterred cannot reliably be disentangled from the large year-to-year changes in the homicide rate caused by other factors,” John J. Donohue III, a law professor at Yale with a doctorate in economics, and Justin Wolfers, an economist at the University of Pennsylvania, wrote in the Stanford Law Review in 2005 . “The existing evidence for deterrence,” they concluded, “is surprisingly fragile.”

Gary Becker, who won the Nobel Prize in economics in 1992 and has followed the debate, said the current empirical evidence was “certainly not decisive” because “we just don’t get enough variation to be confident we have isolated a deterrent effect.”

But, Mr. Becker added, “the evidence of a variety of types — not simply the quantitative evidence — has been enough to convince me that capital punishment does deter and is worth using for the worst sorts of offenses.”

The debate, which first gained significant academic attention two years ago, reprises one from the 1970’s, when early and since largely discredited studies on the deterrent effect of capital punishment were discussed in the Supreme Court’s decision to reinstitute capital punishment in 1976 after a four-year moratorium.

The early studies were inconclusive, Justice Potter Stewart wrote for three justices in the majority in that decision. But he nonetheless concluded that “the death penalty undoubtedly is a significant deterrent.”

The Supreme Court now appears to have once again imposed a moratorium on executions as it considers how to assess the constitutionality of lethal injections. The decision in that case, which is expected next year, will be much narrower than the one in 1976, and the new studies will probably not play any direct role in it.

But the studies have started to reshape the debate over capital punishment and to influence prominent legal scholars.

“The evidence on whether it has a significant deterrent effect seems sufficiently plausible that the moral issue becomes a difficult one,” said Cass R. Sunstein, a law professor at the University of Chicago who has frequently taken liberal positions. “I did shift from being against the death penalty to thinking that if it has a significant deterrent effect it’s probably justified.”

Professor Sunstein and Adrian Vermeule, a law professor at Harvard, wrote in their own Stanford Law Review article that “the recent evidence of a deterrent effect from capital punishment seems impressive, especially in light of its ‘apparent power and unanimity,’ ” quoting a conclusion of a separate overview of the evidence in 2005 by Robert Weisberg, a law professor at Stanford, in the Annual Review of Law and Social Science.

“Capital punishment may well save lives,” the two professors continued. “Those who object to capital punishment, and who do so in the name of protecting life, must come to terms with the possibility that the failure to inflict capital punishment will fail to protect life.”

To a large extent, the participants in the debate talk past one another because they work in different disciplines.

“You have two parallel universes — economists and others,” said Franklin E. Zimring , a law professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and the author of “The Contradictions of American Capital Punishment.” Responding to the new studies, he said, “is like learning to waltz with a cloud.”

To economists, it is obvious that if the cost of an activity rises, the amount of the activity will drop.

“To say anything else is to brand yourself an imbecile,” said Professor Wolfers, an author of the Stanford Law Review article criticizing the death penalty studies.

To many economists, then, it follows inexorably that there will be fewer murders as the likelihood of execution rises.

“I am definitely against the death penalty on lots of different grounds,” said Joanna M. Shepherd, a law professor at Emory with a doctorate in economics who wrote or contributed to several studies . “But I do believe that people respond to incentives.”

But not everyone agrees that potential murderers know enough or can think clearly enough to make rational calculations. And the chances of being caught, convicted, sentenced to death and executed are in any event quite remote. Only about one in 300 homicides results in an execution.

“I honestly think it’s a distraction,” Professor Wolfers said. “The debate here is over whether we kill 60 guys or not. The food stamps program is much more important.”

The studies try to explain changes in the murder rate over time, asking whether the use of the death penalty made a difference. They look at the experiences of states or counties, gauging whether executions at a given time seemed to affect the murder rate that year, the year after or at some other later time. And they try to remove the influence of broader social trends like the crime rate generally, the effectiveness of the criminal justice system, economic conditions and demographic changes.

Critics say the larger factors are impossible to disentangle from whatever effects executions may have. They add that the new studies’ conclusions are skewed by data from a few anomalous jurisdictions, notably Texas, and by a failure to distinguish among various kinds of homicide.

There is also a classic economics question lurking in the background, Professor Wolfers said. “Capital punishment is very expensive,” he said, “so if you choose to spend money on capital punishment you are choosing not to spend it somewhere else, like policing.”

A single capital litigation can cost more than $1 million. It is at least possible that devoting that money to crime prevention would prevent more murders than whatever number, if any, an execution would deter.

The recent studies are, some independent observers say, of good quality, given the limitations of the available data.

“These are sophisticated econometricians who know how to do multiple regression analysis at a pretty high level,” Professor Weisberg of Stanford said.

The economics studies are, moreover, typically published in peer-reviewed journals, while critiques tend to appear in law reviews edited by students.

The available data is nevertheless thin, mostly because there are so few executions.

In 2003, for instance, there were more than 16,000 homicides but only 153 death sentences and 65 executions.

“It seems unlikely,” Professor Donohue and Professor Wolfers concluded in their Stanford article, “that any study based only on recent U.S. data can find a reliable link between homicide and execution rates.”

The two professors offered one particularly compelling comparison. Canada has executed no one since 1962. Yet the murder rates in the United States and Canada have moved in close parallel since then, including before, during and after the four-year death penalty moratorium in the United States in the 1970s.

If criminals do not clearly respond to the slim possibility of an execution, another study suggested, they are affected by the kind of existence they will face in their state prison system.

A 2003 paper by Lawrence Katz, Steven D. Levitt and Ellen Shustorovich published in The American Law and Economics Review found a “a strong and robust negative relationship” between prison conditions, as measured by the number of deaths in prison from any cause, and the crime rate. The effect is, the authors say, “quite large: 30-100 violent crimes and a similar number or property crimes” were deterred per prison death.

On the other hand, the authors found, “there simply does not appear to be enough information in the data on capital punishment to reliably estimate a deterrent effect.”

There is a lesson here, according to some scholars.

“Deterrence cannot be achieved with a half-hearted execution program,” Professor Shepherd of Emory wrote in the Michigan Law Review in 2005. She found a deterrent effect in only those states that executed at least nine people between 1977 and 1996.

Professor Wolfers said the answer to the question of whether the death penalty deterred was “not unknowable in the abstract,” given enough data.

“If I was allowed 1,000 executions and 1,000 exonerations, and I was allowed to do it in a random, focused way,” he said, “I could probably give you an answer.”

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

The research on capital punishment: Recent scholarship and unresolved questions

2014 review of research on capital punishment, including studies that attempt to quantify rates of innocence and the potential deterrence effect on crime.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by Alexandra Raphel and John Wihbey, The Journalist's Resource January 5, 2015

This <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org/criminal-justice/research-capital-punishment-key-recent-studies/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org">The Journalist's Resource</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cropped-jr-favicon-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;">

Over the past year the death penalty has again come into focus as a major public policy and political issue, catalyzed by several high-profile events.

The botched execution of convicted murderer and rapist Clayton Lockett in Oklahoma in 2014 was seen as a potential turning point in the debate, bringing increased attention to the mechanisms by which persons are executed. That was followed by a number of other closely scrutinized cases, and the year ended with few executions relative to years past. On December 31, 2014, Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley commuted the sentences of the remaining four prisoners on death row in that state. In 2013, Maryland became the 18th state to abolish the death penalty after Connecticut in 2012 and New Mexico in 2009.

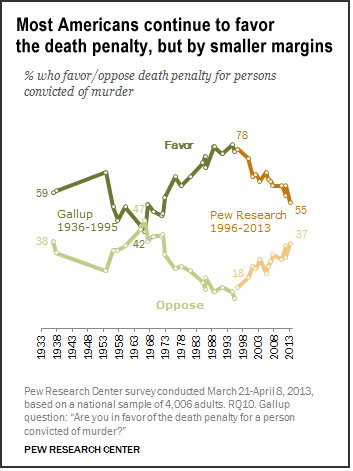

Meanwhile, polling data suggests some softening of public attitudes, though the majority Americans continue to support capital punishment. Gallop noted in October 2014 that the level of public support (60%) is at its lowest in 40 years. A Washington Post -ABC News poll in mid-2014 found that more Americans support life sentences, rather than the death penalty, for convicted murderers. Further, recent polls from the Pew Research Center indicate that only a bare majority of Americans now support capital punishment, 55%, down from 78% in 1996.

Scholarly research sheds light on a number of important aspects of this issue:

False convictions

One key reason for the contentious debate is the concern that states are executing innocent people. How many people are unjustly facing the death penalty? By definition, it is difficult to obtain a reliable answer to this question. Presumably if judges, juries, and law enforcement were always able to conclusively determine who was innocent, those defendants would simply not be convicted in the first place. When capital punishment is the sentence, however, this issue takes on new importance.

Some believe that when it comes to death-penalty cases, this is not a huge cause for concern. In his concurrent opinion in the 2006 Supreme Court case Kansas v. Marsh , Justice Antonin Scalia suggested that the execution error rate was minimal, around 0.027%. However, a 2014 study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests that the figure could be higher. Authors Samuel Gross (University of Michigan Law School), Barbara O’Brien (Michigan State University College of Law), Chen Hu (American College of Radiology) and Edward H. Kennedy (University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine) examine data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics and the Department of Justice relating to exonerations from 1973 to 2004 in an attempt to estimate the rate of false convictions among death row defendants. (Determining innocence with full certainty is an obvious challenge, so as a proxy they use exoneration — “an official determination that a convicted defendant is no longer legally culpable for the crime.”) In short, the researchers ask: If all death row prisoners were to remain under this sentence indefinitely, how many of them would have eventually been found innocent (exonerated)?

Interestingly, the authors also note that advances in DNA identification technology are unlikely to have a large impact on false conviction rates because DNA evidence is most often used in cases of rape rather than homicide. To date, only about 13% of death row exonerations were the result of DNA testing. The Innocence Project , a litigation and public policy organization founded in 1992, has been deeply involved in many such cases.

Death penalty deterrence effects: What do we know?

A chief way proponents of capital punishment defend the practice is the idea that the death penalty deters other people from committing future crimes. For example, research conducted by John J. Donohue III (Yale Law School) and Justin Wolfers (University of Pennsylvania) applies economic theory to the issue: If people act as rational maximizers of their profits or well-being, perhaps there is reason to believe that the most severe of punishments would serve as a deterrent. (The findings of their 2009 study on this issue, “Estimating the Impact of the Death Penalty on Murder,” are inconclusive.) In contrast, one could also imagine a scenario in which capital punishment leads to an increased homicide rate because of a broader perception that the state devalues human life. It could also be possible that the death penalty has no effect at all because information about executions is not diffused in a way that influences future behavior.

In 1978 — two years after the Supreme Court issued its decision reversing a previous ban on the death penalty ( Gregg v. Georgia ) — the National Research Council (NRC) published a comprehensive review of the current research on capital punishment to determine whether one of these hypotheses was more empirically supported than the others. The NRC concluded that “available studies provide no useful evidence on the deterrent effect of capital punishment.”

Researchers have subsequently used a number of methods in an effort to get closer to an accurate estimate of the deterrence effect of the death penalty. Many of the studies have reached conflicting conclusions, however. To conduct an updated review, the NRC formed the Committee on Deterrence and the Death Penalty, comprised of academics from economics departments and public policy schools from institutions around the country, including the Carnegie Mellon University, University of Chicago and Duke University.

In 2012, the Committee published an updated report that concluded that not much had changed in recent decades: “Research conducted in the 30 years since the earlier NRC report has not sufficiently advanced knowledge to allow a conclusion, however qualified, about the effect of the death penalty on homicide rates.” The report goes on to recommend that none of the reviewed reports be used to influence public policy decisions on the death penalty.