Advertisement

Trends in insomnia research for the next decade: a narrative review

- Review Article

- Published: 06 April 2020

- Volume 18 , pages 199–207, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Daniel Ruivo Marques 1 , 2 ,

- Ana Allen Gomes 2 , 3 ,

- Vanda Clemente 2 , 4 ,

- José Moutinho dos Santos 4 ,

- Joana Serra 4 &

- Maria Helena Pinto de Azevedo 5

707 Accesses

11 Citations

Explore all metrics

Insomnia disorder has known striking developments over the last few years. Partly due to advances in neuroimaging techniques and brain sciences, our understanding of insomnia disorder has become more fine-tuned. Besides, developments within psychological and psychiatric fields have contributed to improve conceptualization, assessment, and treatment of insomnia. In this paper, we present a list of promising 10 key “hot-topics” that we think in the next 10 years will continue to stimulate researchers in insomnia’s domain: increasing of systematic reviews and meta-analyses; improvement of existing self-report measures; increasing of genetic and epigenetic investigation; research on new pharmacological agents; advances in neuroimaging studies and methods; new psychological clinical approaches; effectiveness studies of e-treatments and greater dissemination of evidence-based therapies for insomnia; call for integrative models; network approach using in insomnia; and assessment of insomnia phenotypes. The breadth of all these topics demands the collaboration of researchers from different scientific fields within sleep medicine. In summarizing, in the next decade, it is predictable that insomnia’s research still benefit from different scientific disciplines.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Pain-Insomnia-Depression Syndrome: Triangular Relationships, Pathobiological Correlations, Current Treatment Modalities, and Future Direction

Genome-wide analysis of insomnia in 1,331,010 individuals identifies new risk loci and functional pathways

American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International classification of sleep disorders: diagnostic and coding manual. 3rd ed. Westchester: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014.

Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-5. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Book Google Scholar

Baglioni C, Regen W, Teghen A, Spiegelhalder K, Feige B, Nissen C, Riemann D. Sleep changes in the disorder of insomnia: a meta-analysis of polysomnographic studies. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18(3):195–21313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2013.04.001 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2(4):297–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1389-9457(00)00065-4 .

Berman M, Jonides J, Nee D. Studying mind and brain with fMRI. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2006;1(2):158–61. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsl019 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bheemsain T, Kar S. An overview of insomnia management. Delphi Psychiatry J. 2012;15(2):294–301.

Blanken T, Benjamins J, Borsboom D, Vermunt J, Paquola C, Ramautar J, Van Someren E. Insomnia disorder subtypes derived from life history and traits of affect and personality. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(2):151–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30464-4 .

Borsboom D, Cramer A. Network analysis: an integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9(1):91–121. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185608 .

Borsboom D. A network theory of mental disorders. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(1):5–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20375 .

Bragantini D, Sivertsen B, Gehrman P, Lydersen S, Güzey IC. Genetic polymorphisms associated with sleep-related phenotypes; relationships with individual nocturnal symptoms of insomnia in the HUNT study. BMC Med Genet. 2019;20(1):179. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12881-019-0916 .

Broomfield N, Espie C. Towards a valid, reliable measure of sleep effort. J Sleep Res. 2005;14(4):401–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2869.2005.00481.x .

Busto U, Sykora K, Sellers E. A clinical scale to assess benzodiazepine withdrawal. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1989;9(6):412–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004714-198912000-00005 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Buysse D, Ancoli-Israel S, Edinger J, Lichstein K, Morin C. Recommendations for a standard research assessment of insomnia. Sleep. 2006;29(9):1155–73. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/29.9.1155 .

Buysse D, Germain A, Hall M, Monk T, Nofzinger E. A neurobiological model of insomnia. Drug Discov Today Dis Models. 2011;8(4):129–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ddmod.2011.07.002 .

Buysse D, Harvey A. Insomnia: recent developments and future directions. In: Kryger M, Roth T, Dement W, editors. Principles and practices of sleep medicine. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017. p. 757–760.

Chapter Google Scholar

Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–21313. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 .

Cassano GB, Petracca A, Cesana BM. A new scale for the evaluation of benzodiazepine withdrawal symptoms: sessb. Curr Therapeutic Res. 1994;55(3):275–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0011-393x(05)80171-7 .

Article Google Scholar

Dekker K, Blanken T, Van Someren E. Insomnia and personality: a network approach. Brain Sci. 2017;7(3):28. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci7030028 .

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Edinger J, Leggett M, Carney C, Manber R. Psychological and behavioral treatments for insomnia II: implementation and specific populations. In: Kryger M, Roth T, Dement W, editors. Principles and practices of sleep medicine. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017. p. 814–831.

Eisai Global. U.S. FDA approves Eisai’s Dayvigo TM (Lemborexant) for treatment of insomnia in adult patients. 2019. https://www.eisai.com/news/2019/news201993.html . Accessed 31 Jan 2020.

Espie C, Kyle S, Williams C, Ong J, Douglas N, Hames P, Brown J. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of online cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia disorder delivered via an automated media-rich web application. Sleep. 2012;35(6):769–81. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.1872 .

Fernandez-Mendoza J. The insomnia with short sleep duration phenotype: an update on it’s importance for health and prevention. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2017;30(1):56–63. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000292 .

Field A, Gillett R. How to do a meta-analysis. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 2010;63:665–94. https://doi.org/10.1348/000711010X502733 .

Gehrman P, Pfeiffenberger C, Byrne E. The role of genes in the insomnia phenotype. Sleep Med Clin. 2013;8(3):323–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsmc.2013.04.005 .

Gilbert P. The origins and nature of compassion focused therapy. Br J Clin Psychol. 2014;53(1):6–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12043 .

Gregory AM, Rijsdijk FV, Eley TC, Buysse DJ, Schneider MN, Parsons M, Barclay NL. A longitudinal twin and sibling study of associations between insomnia and depression symptoms in young adults. Sleep. 2016;39(11):1985–92. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.6228 .

Hadian S, Jabalameli S. The effectiveness of compassion-focused therapy (CFT) on rumination in students with sleep disorders: a quasi-experimental research, before and after. J Urmia Univ Med Sci. 2019;30(2):86–96.

Hein M, Lanquart J-P, Loas G, Hubain P, Linkowski P. Similar polysomnographic pattern in primary insomnia and major depression with objective insomnia: a sign of common pathophysiology?. BMC Psychiatry. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1438-4

Hertenstein E, Feige B, Gmeiner T, Kienzler C, Spiegelhalder K, Johann A, Baglioni C. Insomnia as a predictor of mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2019;43:96–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2018.10.006 .

Jansen P, Watanabe K, Stringer S, Skene N, Bryois J, Posthuma D. Genome-wide analysis of insomnia in 1,331,010 individuals identifies new risk loci and functional pathways. Nat Genet. 2019;51:394–403. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0333-3 .

Jones S, van Hees V, Mazzotti D, Marques-Vidal P, Sabia S, van der Spek A, Wood A. Genetic studies of accelerometer-based sleep measures in 85,670 individuals yield new insights into human sleep behaviour. Nat Commun. 2018;10(1):1585. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09576-1 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Kobayashi M, Okajima I, Narisawa H, Kikuchi T, Matsui K, Inada K, Inoue Y. Development of a new benzodiazepine hypnotics withdrawal symptom scale. Sleep Biol Rhythm. 2018;16(3):263–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41105-018-0151-0 .

Lane J, Jones S, Dashti H, Wood A, Aragam K, Saxena R. Biological and clinical insights from genetics of insomnia symptoms. Nat Genet. 2019;51:387–93. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-019-0361-7 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lilenfeld S. What is “evidence” in psychotherapies? World Psychiatry. 2019;18(3):245–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20654 .

Lind MJ, Gehrman PR. Genetic pathways to insomnia. Brain Sci. 2016;6(4):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci6040064 .

Article CAS PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ma Z-R, Shi L-J, Deng M-H. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy in children and adolescents with insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2018;51(6):e7070. https://doi.org/10.1590/1414-431X20187070 .

Marques D. Do we need neuroimaging to treat insomnia effectively? Sleep Med. 2019;53:205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2017.08.005 .

Marques D. “Time to relax”: considerations on relaxation training for insomnia disorder. Sleep Biol Rhythm. 2019;17(2):263–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41105-018-00203-y .

Marques D. Self-report measures as complementary exams in the diagnosis of insomnia. Revista Portuguesa de Investigação Comportamental e Social. 2020. [Accepted for publication] .

Marques D, Azevedo MH. Potentialities of network analysis for sleep medicine. J Psychosom Res. 2018;111:89–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.05.019 .

Marques D, Clemente V, Gomes A, Azevedo MH. Profiling insomnia using subjective measures: where are we and where are we going. Sleep Med. 2018;43:103–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2017.12.006 .

Marques D, Gomes A, Azevedo MH. Utility of studies in community-based populations. 2019. [Manuscript submitted for publication] .

Marques D, Gomes A, Caetano G, Castelo-Branco M. Insomnia disorder and brain’s default-mode network. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2018;18(8):45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-018-0861-3 .

Marques D, Gomes A, Clemente V, Santos J, Castelo-Branco M. Default-mode network activity and its role in comprehension and management of psychophysiological insomnia: a new perspective. New Ideas Psychol. 2015;36:30–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2014.08.001 .

Marques D, Gomes A, Clemente V, Santos J, Duarte I, Caetano G, Castelo-Branco M. Unbalanced resting-state networks activity in psychophysiological insomnia. Sleep Biol Rhythm. 2017;15(2):167–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41105-017-0096-8 .

Marques D, Gomes AA, Clemente V, Moutinho J, Caetano G, Castelo-Branco M. An overview regarding insomnia disorder: conceptualization, assessment and treatment. In: Columbus AM, editor. Advances in psychology research. New York: Nova Science Publishers Inc; 2016. p. 81–116.

Marques D, Gomes A, Clemente V, Santos J, Caetano G, Castelo-Branco M. Neurobiological correlates of psychological treatments for insomnia: a review. Eur Psychol. 2016;21(3):195–205. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000264 .

McNally R. Can network analysis transform psychopathology? Behav Res Ther. 2016;86:95–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.06.006 .

Morales-Lara D, De-la-Peña C, Murillo-Rodríguez E. Dad’s snoring may have left molecular scars in your DNA: the emerging role of epigenetics in sleep disorders. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55(4):2713–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-017-0409-6 .

Morin C. Contributions of cognitive-behavioral approaches to the clinical management of insomnia. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;4(1):21–6.

Morin C, Vallières A, Ivers H. Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep (DBAS): validation of a brief version (DBAS-16). Sleep. 2007;30(11):1547–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/30.11.1547 .

Ong J, Manber R, Segal Z, Xia Y, Shapiro S, Wyatt J. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for chronic insomnia. Sleep. 2014;37(9):1553–63. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.4010 .

Owen M, Cardno A, O’Donovan M. Psychiatric genetics: back to the future. Mol Psychiatry. 2000;5(1):22–31. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.mp.4000702 .

Päivi L, Sitwat L, Harri O-K, Joona M, Raimo L. ACT for sleep—internet-delivered self-help ACT for sub-clinical and clinical insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. J Context Behav Sci. 2019;12:119–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.04.001 .

Palagini L, Biber K, Riemann D. The genetics of insomnia–evidence for epigenetic mechanisms? Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18(3):225–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2013.05.002 .

Perlis M, Ellis J, Kloss J, Riemann D. Etiology and pathophysiology of insomnia. In: Kryger M, Roth T, Dement W, editors. Principles and practices of sleep medicine. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017. p. 769–784.

Perlis M, Shaw P, Cano G, Espie C. Models of insomnia. In: Kryger M, Roth T, Dement W, editors. Principles and practice of sleep medicine. 5th ed. Missouri: Elsevier Saunders; 2011. p. 850–865.

Qureshi I, Mehler M. Epigenetics of sleep and chronobiology. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2014;14(3):432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-013-0432-6 .

Riemann D, Baglioni C, Bassetti C, Bjorvatn B, Dolenc Groselj L, Ellis J, Spiegelhalder K. European guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of insomnia. J Sleep Res. 2017;26(6):675–700. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.12594 .

Riemann D, Spiegelhalder K, Feige B, Voderholzer U, Berger M, Perlis M, Nissen C. The hyperarousal model of insomnia: a review of the concept and its evidence. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14(1):19–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2009.04.002 .

Riemann D, Spiegelhalder K, Nissen C, Hirscher V, Baglioni C, Feige B. REM sleep instability: a new pathway for insomnia? Pharmacopsychiatry. 2012;45(5):167–76. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1299721 .

Rodriguez M, Maeda Y. Meta-analysis of coefficient alpha. Psychol Methods. 2006;11(3):306–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.11.3.306 .

Schulz H, Salzarulo P. The development of sleep medicine: a historical sketch. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(7):1041–52. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.5946 .

Siddaway A, Wood A, Hedges L. How to do a systematic review: a best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses. Annu Rev Psychol. 2019;70:747–70. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803 .

Sirois F, Nauts S, Molnar D. Self-compassion and bedtime procrastination: an emotion regulation perspective. Mindfulness. 2019;10(3):434–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0983-3 .

Spiegelhalder K, Regen W, Baglioni C, Nissen C, Riemann D, Kyle S. Neuroimaging insights into insomnia. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2015;15(3):9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-015-0527-3 .

Stein M, McCarthy M, Chen C, Jain S, Gelernter J, He F, Ursano R. Genome-wide analysis of insomnia disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(11):2238–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0033-5 .

Stepanski E. Behavioral sleep medicine: a historical perspective. Behav Sleep Med. 2003;1(1):4–21. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15402010BSM0101_3 .

Tam V, Patel N, Turcotte M, Bossé Y, Paré G, Meyre D. Benefits and limitations of genome-wide association studies. Nat Rev Genet. 2019;20(8):467–84. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-019-0127 .

Tolin D, McKay D, Forman E, Klonsky E, Thombs B. Empirically supported treatment: recommendations for a new model. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2015;22(4):317–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12122 .

Trauer J, Qian M, Doyle J, Rajaratnam S, Cunnington D. Cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(3):191–204. https://doi.org/10.7326/M14-2841 .

van Dalfsen J, Markus C. The involvement of sleep in the relationship between the serotonin transporter gene-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) and depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2019;256:205–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.05.047 .

van Straten A, van der Zweerde T, Kleiboer A, Cuijpers P, Morin C, Lancee J. Cognitive and behavioral therapies in the treatment of insomnia: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;38:3–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2017.02.001 .

Walsh J, Roth T. Pharmacologic treatment of insomnia: benzodiazepine receptor agonists. In: Kryger M, Roth T, Dement W, editors. Principles and practices of sleep medicine. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2017. p. 832–841.

Wang Y, Wang F, Zheng W, Zhang L, Ng C, Unqvari G, Xiang Y. Mindfulness-based interventions for insomnia: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Behav Sleep Med. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1080/15402002.2018.1518228 [Epub ahead of print] .

Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Ford J. Default mode network activity and connectivity in psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8:49–76. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143049 .

Wilson B. Cutting edge developments in neuropsychological rehabilitation and possible future directions. Brain Impair. 2011;12(1):33–42. https://doi.org/10.1375/brim.12.1.33 .

Wilson B. Neuropsychological rehabilitation: state of the science. S Afr J Psychol. 2013;43(3):267–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246313494156 .

Winkler A, Rief W. Effect of placebo conditions on polysomnographic parameters in primary insomnia: a meta-analysis. Sleep. 2015;38(6):925–31. https://doi.org/10.5665/sleep.4742 .

Wittchen H, Jacobi F, Rehm J, Gustavsson A, Svensson M, Jönsson B, Steinhausen H. The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21(9):655–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.018 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the reviewers for their important comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Education and Psychology, University of Aveiro, Campus Universitário de Santiago, 3810-193, Aveiro, Portugal

Daniel Ruivo Marques

Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, CINEICC-Center for Research in Neuropsychology and Cognitive Behavioral Intervention, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal

Daniel Ruivo Marques, Ana Allen Gomes & Vanda Clemente

Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, University of Coimbra, Rua Do Colégio Novo, 3000-115, Coimbra, Portugal

Ana Allen Gomes

Sleep Medicine Centre, Coimbra University Hospital Centre (CHUC), Coimbra, Portugal

Vanda Clemente, José Moutinho dos Santos & Joana Serra

Faculty of Medicine, University of Coimbra, Rua Larga, 3004-504, Coimbra, Portugal

Maria Helena Pinto de Azevedo

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Daniel Ruivo Marques .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Marques, D.R., Gomes, A.A., Clemente, V. et al. Trends in insomnia research for the next decade: a narrative review. Sleep Biol. Rhythms 18 , 199–207 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41105-020-00269-7

Download citation

Received : 20 August 2019

Accepted : 28 March 2020

Published : 06 April 2020

Issue Date : July 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s41105-020-00269-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Sleep disorder

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

A Narrative Review of the Literature on Insufficient Sleep, Insomnia, and Health Correlates in American Indian/Alaska Native Populations

Affiliations.

- 1 University of Alaska Anchorage, Anchorage, AK, USA.

- 2 Waianae Coast Comprehensive Health Center, Waianae, HI, USA.

- 3 University of Montana, Missoula, MT, USA.

- 4 New Mexico VA Health Care System, Albuquerque, NM, USA.

- PMID: 31360174

- PMCID: PMC6644264

- DOI: 10.1155/2019/4306463

Insufficient sleep and insomnia promote chronic disease in the general population and may combine with social and economic factors to increase rates of chronic health conditions among AI/AN people. Given that insufficient sleep and insomnia can be addressed via behavioral interventions, it is critical to understand the prevalence and correlates of these disorders among AI/AN individuals in order to elucidate the mechanisms associated with health disparities and provide guidance for subsequent treatment research and practice. We reviewed the available literature on insufficient sleep and insomnia in the AI/AN population. PubMed, PsycINFO, Google Scholar, and ProQuest were searched between June 12 th and October 28 th of 2018. Prevalence of insufficient sleep ranged from 15% to 40%; insomnia prevalence ranged from 25% to 33%. Insufficient sleep was associated with unhealthy diet, low physical activity levels, higher BMI, worse self-reported health, increased risk for diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, frequent mental distress, smoking, binge drinking, depression, and chronic pain. Insomnia was associated with depression, childhood abuse, PTSD, anxiety, alcohol use, low social support, and low trait-resilience levels. Research on evidence-based treatment and implementation practices targeting insufficient sleep and insomnia was lacking, and only one study described the development/validation of a measure of insufficient sleep among AI/AN people. There is a need for rigorous sleep research including testing and implementation of evidence-based treatment for insufficient sleep and insomnia in this population in an effort to help eliminate health disparities. We present recommendations for research and clinical practice based on the current review.

PubMed Disclaimer

Resource identification and screening process.

Similar articles

- Excess frequent insufficient sleep in American Indians/Alaska natives. Chapman DP, Croft JB, Liu Y, Perry GS, Presley-Cantrell LR, Ford ES. Chapman DP, et al. J Environ Public Health. 2013;2013:259645. doi: 10.1155/2013/259645. Epub 2013 Feb 21. J Environ Public Health. 2013. PMID: 23509471 Free PMC article.

- A Systematic Review of Environmental Health Outcomes in Selected American Indian and Alaska Native Populations. Meltzer GY, Watkins BX, Vieira D, Zelikoff JT, Boden-Albala B. Meltzer GY, et al. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020 Aug;7(4):698-739. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00700-2. Epub 2020 Jan 23. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020. PMID: 31974734

- Sleep Problems and Health Outcomes Among Urban American Indian and Alaska Native Adolescents. Troxel WM, Klein DJ, Dong L, Mousavi Z, Dickerson DL, Johnson CL, Palimaru AI, Brown RA, Rodriguez A, Parker J, Schweigman K, D'Amico EJ. Troxel WM, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Jun 3;7(6):e2414735. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.14735. JAMA Netw Open. 2024. PMID: 38833247 Free PMC article.

- Emotional and Behavioral Aspects of Diabetes in American Indians/Alaska Natives. Scarton LJ, de Groot M. Scarton LJ, et al. Health Educ Behav. 2017 Feb;44(1):70-82. doi: 10.1177/1090198116639289. Epub 2016 Jul 9. Health Educ Behav. 2017. PMID: 27179289 Review.

- Resilience and health in American Indians and Alaska Natives: A scoping review of the literature. John-Henderson NA, White EJ, Crowder TL. John-Henderson NA, et al. Dev Psychopathol. 2023 Dec;35(5):2241-2252. doi: 10.1017/S0954579423000640. Epub 2023 Jun 22. Dev Psychopathol. 2023. PMID: 37345444 Free PMC article. Review.

- Effect of Centella asiatica ethanol extract on zebrafish larvae ( Danio rerio ) insomnia model through inhibition of Orexin, ERK, Akt and p38. Afif Z, Eddy Santoso MI, Nurdiana, Khotimah H, Satriotomo I, Kurniawan SN, Sujuti H, Iskandar DS, Hakimah A. Afif Z, et al. F1000Res. 2024 Jul 18;13:107. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.141064.1. eCollection 2024. F1000Res. 2024. PMID: 38812527 Free PMC article.

- Association between poor sleep and mental health issues in Indigenous communities across the globe: a systematic review. Fernandez DR, Lee R, Tran N, Jabran DS, King S, McDaid L. Fernandez DR, et al. Sleep Adv. 2024 May 2;5(1):zpae028. doi: 10.1093/sleepadvances/zpae028. eCollection 2024. Sleep Adv. 2024. PMID: 38721053 Free PMC article.

- Effect of physical activity on sleep problems in sedentary adults: a scoping systematic review. Rai A, Aldabbas M, Veqar Z. Rai A, et al. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2023 Oct 28;22(1):13-31. doi: 10.1007/s41105-023-00494-w. eCollection 2024 Jan. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2023. PMID: 38476845 Review.

- Poor self-reported sleep quality associated with suicide risk in a community sample of American Indian adults. Ehlers CL, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Bernert R. Ehlers CL, et al. Sleep Adv. 2023 May 19;4(1):zpad024. doi: 10.1093/sleepadvances/zpad024. eCollection 2023. Sleep Adv. 2023. PMID: 37293513 Free PMC article.

- Relationship between sleep duration and quality and glycated hemoglobin, body mass index, and self-reported health in Marshallese adults. McElfish PA, Andersen JA, Felix HC, Purvis RS, Rowland B, Scott AJ, Chatrathi M, Long CR. McElfish PA, et al. Sleep Health. 2021 Jun;7(3):332-338. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2021.01.007. Epub 2021 Mar 8. Sleep Health. 2021. PMID: 33707104 Free PMC article.

- Sivertsen B., Krokstad S., Overland S., Mykletun A. The epidemiology of insomnia: associations with physical and mental health: the HUNT-2 study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2009;67(2):103–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.05.001. - DOI - PubMed

- Biddle D. J., Kelly P. J., Hermens D. F., Glozier N. The association of insomnia with future mental illness: is it just residual symptoms? Sleep Health. 2018;4(4):352–359. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2018.05.008. - DOI - PubMed

- Tang W., Lu Y., Xu J. Post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety and depression symptoms among adolescent earthquake victims: comorbidity and associated sleep-disturbing factors. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2018;53(11):1241–1251. doi: 10.1007/s00127-018-1576-0. - DOI - PubMed

- Smith M. T., Haythornthwaite J. A. How do sleep disturbance and chronic pain inter-relate? Insights from the longitudinal and cognitive-behavioral clinical trials literature. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2004;8(2):119–132. doi: 10.1016/s1087-0792(03)00044-3. - DOI - PubMed

- Roberts M. B., Drummond P. D. Sleep problems are associated with chronic pain over and above mutual associations with depression and catastrophizing. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2016;32(9):792–799. doi: 10.1097/ajp.0000000000000329. - DOI - PubMed

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

Related information

- Cited in Books

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Europe PubMed Central

- Hindawi Limited

- PubMed Central

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

The different faces of insomnia.

- 1 Department of Internal Medicine and Dermatology, Interdisciplinary Center of Sleep Medicine, Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany

- 2 Department of Behavioral Therapy and Psychosomatic Medicine, Rehabilitation Center Seehof, Federal German Pension Agency, Seehof, Germany

- 3 Department of Biology, Saratov State University, Saratov, Russia

Objectives: The identification of clinically relevant subtypes of insomnia is important. Including a comprehensive literature review, this study also introduces new phenotypical relevant parameters by describing a specific insomnia cohort.

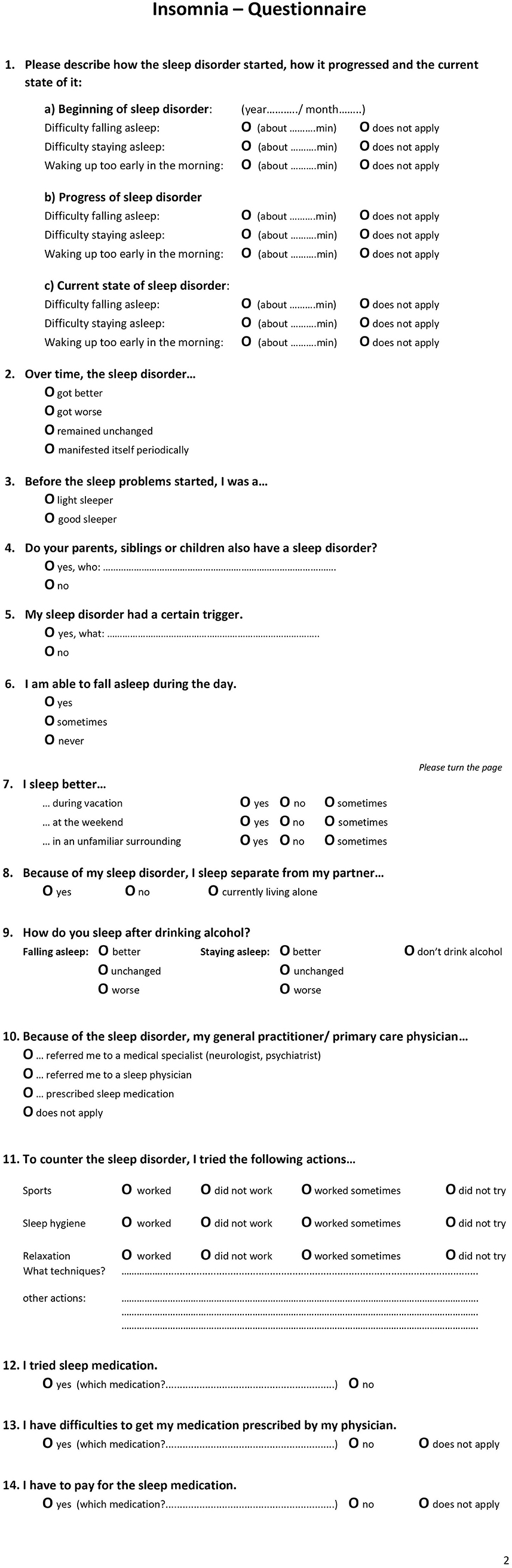

Methods: Patients visiting the sleep center and indicating self-reported signs of insomnia were examined by a sleep specialist who confirmed an insomnia diagnosis. A 14-item insomnia questionnaire on symptoms, progression, sleep history and treatment, was part of the clinical routine.

Results: A cohort of 456 insomnia patients was described (56% women, mean age 52 ± 16 years). They had suffered from symptoms for about 12 ± 11 years before seeing a sleep specialist. About 40–50% mentioned a trigger (most frequently psychological triggers), a history of being bad sleepers to begin with, a family history of sleep problems, and a negative progression of insomnia. Over one third were not able to fall asleep during the day. SMI (sleep maintenance insomnia) symptoms were most frequent, but only prevalence of EMA (early morning awakening) symptoms significantly increased from 40 to 45% over time. Alternative non-medical treatments were effective in fewer than 10% of cases.

Conclusion: Our specific cohort displayed a long history of suffering and the sleep specialist is usually not the first point of contact. We aimed to describe specific characteristics of insomnia with a simple questionnaire, containing questions (e.g., ability to fall asleep during the day, effects of non-medical therapy methods, symptom stability) not yet commonly asked and of unknown clinical relevance as yet. We suggest adding them to anamnesis to help differentiate the severity of insomnia and initiate further research, leading to a better understanding of the severity of insomnia and individualized therapy. This study is part of a specific Research Topic introduced by Frontiers on the heterogeneity of insomnia and its comorbidity and will hopefully inspire more research in this area.

Introduction

Insomnia is one of the most frequent sleep disorders with continuously increasing prevalence. About 30–50% of the US adult population exhibit insomnia symptoms, 15–20% display a short-term insomnia of <3 months, and 5–15% display a chronic insomnia of >3 months ( 1 – 3 ). Common diagnostic manuals include the ICSD-3 (International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3 rd Edition, American Academy of Sleep Medicine 2014) and the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5 th Edition, American Psychiatric Association 2013) ( 4 , 5 ). Main characteristics of insomnia include dissatisfaction with sleep quantity and quality with one or more of the following symptoms: difficulties initiating sleep, difficulties maintaining sleep (frequent or prolonged awakenings with problems returning to sleep again), and early morning awakening (occurring earlier than desired after a total sleep time of only 3–5 h with the inability to return to sleep). The disturbed sleep is associated with stress, psychological strain and suffering, as well as impairment in social, occupational, and other important areas of functioning. Complaints include fatigue, exhaustion, lack of energy, daytime sleepiness, cognitive impairment (e.g., attention, concentration, and memory), mood swings (e.g., irritability, dysphoria), impaired occupational functioning and impaired social functioning. The symptoms occur for at least 3 nights per week for at least 3 months and occur despite an adequate sleep environment.

Previous dichotomization of insomnia in primary and secondary (or comorbid) insomnia has been abandoned with the new editions of the DSM-5 and ICSD-3. Currently, insomnia is mostly characterized by the common phenotypes of sleep onset insomnia (SOI insomnia, difficulty falling asleep), sleep maintenance insomnia (SMI insomnia, difficulty staying asleep), early morning awakenings insomnia (EMA insomnia), and a combination of those. Another categorization follows the timeframe of being an acute (<1 month), subacute (1–3 months), and chronic insomnia (>3 months) ( 4 , 5 ). While other sleep disorders (e.g., sleep apnea) are categorized by severity into mild, moderate, or severe, which has important implications for the choice of therapy, insomnia still lacks such a classification. The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) is the only instrument currently in use that allows for severity classification: no insomnia (score 0–7), subclinical insomnia (score 8–14), or moderate to severe insomnia (score 15–28) ( 6 ).

The characterization of different phenotypes is important to establish clinically relevant subtypes of insomnia. It may help to reduce the heterogeneity of insomnia and facilitate cause identification and personalized treatments. Yet there are not many standardized instruments of insomnia diagnosis allowing for phenotyping. However, there has been evidence that insomniacs with a total sleep time of <6 h suffer a more severe insomnia than insomniacs with a total sleep time of 6 h or more ( 7 ). They display mental and psychological impairment compared to patients with average or longer than average sleep. However, mortality is increased for insomniacs with longer total sleep time ( 8 ). The sleep duration with the 6-h distinction also influences the therapy outcome, success of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and the relation to comorbid bipolar disorder ( 9 , 10 ). Recently, a study investigated subtypes of insomnia according to psychological stress ( 11 ). Questioning 2,224 volunteers with an ISI score of at least 10 and a control group of 2,098 volunteers with an ISI score below 10, five insomnia subtypes were identified: highly distressed, moderately distressed but sensitive to positive reinforcement (accepting of positive emotions), moderately distressed insensitive to positive reinforcement, slightly distressed with a high reactivity to their environment and life circumstances, and slightly distressed with low reactivity. The results showed a high stability of the classification over the 5-year investigation. The psychological categorization is clinically relevant as there were clear differences identified between the subtypes regarding development, therapy success, presence of electroencephalogram (EEG) biomarker, and the risk for depression. This was a first approach to subtyping insomnia patients according to psychological health. The exact effect of psychological health, family history, comorbidity, personality, environment and sleep quality on insomnia is still unclear. Similar symptom clusters have been discussed for other disorders including depression ( 12 ).

Our study is part of the specific Research Topic introduced by Frontiers on the heterogeneity of insomnia and its comorbidity. We aim to encourage and further the discussion on insomnia heterogeneity and the need for possible phenotyping, we do not intend to provide a complete list of phenotypes or possible clusters. The study picked up the approach of subtyping insomnia by collecting a short questionnaire during anamnesis on possible related symptoms, onset and course of insomnia. We described phenotypical traits of insomniacs with a cohort of sleep disturbed patients from a specialized outpatient clinic for sleep disorders.

Participants and Recruitment

Since 2018, a specialized 14-item insomnia questionnaire has formed part of the clinical routine at the outpatient clinic of the Interdisciplinary Center of Sleep Medicine, Charité—Universitätsmedizin Berlin ( Figure 1 ). The questionnaire is the result of literature research, clinical experience, and consensus of psychologists, neurologist, psychiatrists, and sleep physicians within the sleep center. Patients who visited the outpatient clinic between 01/2019 and 02/2020 and indicated self-reported symptoms presenting a suspicion of insomnia (e.g., difficulties initiating sleep, maintaining sleep, or early morning awakening) according to ICSD-3 criteria were recruited and completed the questionnaire. In total, 486 patients were examined by a physician specializing in sleep disorders and insomnia who confirmed an insomnia diagnosis. The questionnaire did not contain any identifying information. As the questionnaire is part of the clinical routine and the de-identified data has been analyzed retrospectively, ethical review and approval was not required in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. As part of the clinical routine, patients signed informed consent forms allowing de-identified data of their patient file, including the insomnia questionnaire, to be used for research purposes.

Figure 1 . The English translation of the 14-item Insomnia Questionnaire with page 1 and page 2.

Questionnaire

The insomnia questionnaire consisted of 14 items ( Figure 1 presents an English translation of the questionnaire). These included questions related to (1) type of insomnia (SOI—sleep onset insomnia, SMI—sleep maintenance insomnia, EMA—early awakening insomnia, multiple answers possible) at three points in time (start of disorder, progression, current state), (2) progression of insomnia, (3) sleep history of being a light or good sleeper, (4) relatives with sleep disorder, (5) triggers, (6) daytime sleep, (7) sleeping in different environments, (8) sleeping arrangement with partner, (9) alcohol as a sleep aid, (10) referral/ recommendation of general practitioner (multiple answer options), (11) alternative sleep treatments, and (12–14) sleep medication.

Procedure of the examination was standardized and performed by the same physician: On arrival, patients received several sleep questionnaires including the 14-item insomnia questionnaire. They were asked to complete these questionnaires before seeing the physician. During the following in-person consultation, the physician completed a full anamnesis (a patient-reported medical history) and confirmed a diagnosis of a primary insomnia according to ICSD-3 criteria. Next, the questions of the insomnia questionnaire were evaluated. Certain questions were clarified, and missing information added. For example, for question 3, light sleeper was defined. Light sleeper includes patients with a regular bedtime but whose sleep is sensitive to light, temperature, and noise. They need a specific degree of sleep comfort and sleep worse in an unfamiliar environment. These patients can nap during the day and sleep better during vacation and time off (e.g., weekends). They perceive their sleep as non-restorative. They also do not meet the diagnostic criteria of insomnia. The question refers to the time before the insomnia started, mostly referring to childhood / adolescence. For question 6, it was clarified that daytime napping included a daytime situation that explicitly allows for napping. For question 7, it was explained that “weekend” also included the days off work.

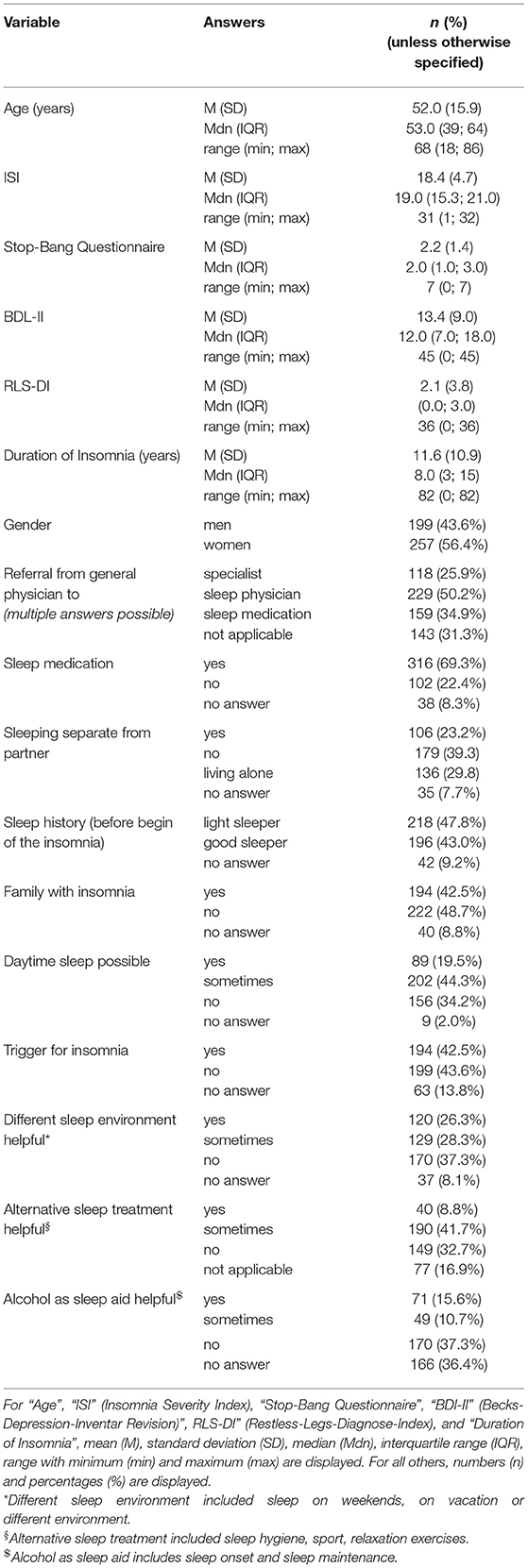

Sample size was calculated based on prevalence data and the estimated number of insomnia patients: ca. 30–50% of 328.2 million people (US population estimate 2019) result in about 98.5–164.1 million patients ( 13 ). With an accepted error rate of maximum 5% and a confidence interval of 95%, the sample size was set to at least 400 questionnaires in order to detect sufficiently powerful effects. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 20). The patient cohort was described using a descriptive analysis with numbers and percentages ( Table 1 ). In order to investigate possible insomnia subgroups based on phenotypes/characteristics, we compared items with dichotomous answers. Item 7 (sleeping in different environments), item 9 (alcohol as a sleep aid), and item 11 (alternative sleep treatments) each had several subcategories which were consolidated into one overall category. For the text answer of item 5 (trigger) we performed a qualitative data analysis by subjectively grouping the text data and visually presenting the categories. A t-test was used for group comparisons of continuous variables (e.g., age), the chi-square test for dichotomous variables. Significance level was set at 0.05.

Table 1 . Sample description ( n = 456 patients).

Patient Description

Due to missing information that could also not be completed during the in-person consultation with the physician, 30 questionnaires were removed from analysis. The remaining 456 questionnaires were de-identified and analyzed. The patient cohort ( Table 1 ) reported having sleep problems for an average of 11.6 ± 10.9 years (range: 0–82 years, where 0 means the symptoms just started within the past month). The cohort consisted of slightly more female insomniacs (56%) and had an average age of 52.0 ± 15.9 years (range: 18–86 years). More than half of the patients reported having a partner and not living alone (63%), and of those 37% slept in a separate room due to the sleep disorder. If the patient went to a general physician first, 50% were referred to a sleep specialist and 26% to another specialist (neurologist, psychiatrist etc.). In 35% of those cases, the general physician initiated a therapy with sleep medication. In general, 69% of the patients reported having used sleep medication, 23% indicated that they had not. Only 9% mentioned that it was difficult to get sleep medication. While 26% stated they had to pay for sleep medication, 37% said they did not. In Germany, sleep medication for primary insomnia covered by insurance only includes melatonin (only for patients over 55 years) and z-drugs (only for the acute therapy of 4 weeks).

Sleep Characteristics

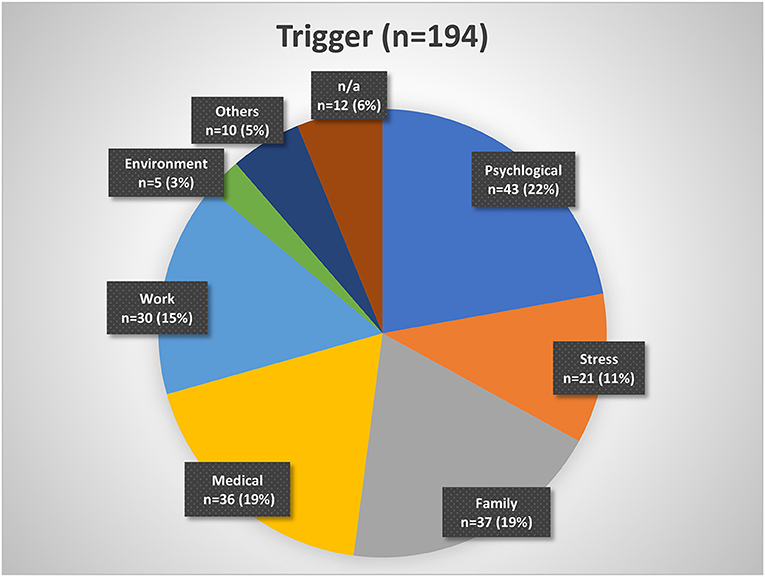

About 43% of the patients indicated that they had a history of being good sleepers before the insomnia onset, while 48% mentioned that they have always been light sleepers. Forty-three percent reported having a family member with sleep problems. Despite insomnia symptoms, 20% of patients indicated that they were able to fall asleep during the day and 44% sometimes. While 43% of patients reported a trigger for the sleep problems, 42% reported no trigger ( Table 1 ). Figure 2 presents a categorization of the reported triggers. The most frequent triggers were of psychological nature (22%) including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, death of a family member, trauma, rape, psychotherapy etc. Stress was listed as a separate category but is to be considered as a subcategory of psychological triggers (additional 11%). Work related triggers including change or loss of job, freelance work, work problems, shift work, long work hours, workload, mobbing/ bulling etc. accounted for 15%.

Figure 2 . Insomnia triggers organized by categories. Psychological triggers include depression, fear, trauma, etc. Stress may be considered a subgroup of psychological triggers. Family triggers include birth, children, marriage, divorce, etc. Medical triggers include sickness, operations, etc. Work triggers include mobbing, loss of job, change of job, workload, etc. Environment triggers include noise, lighting, neighborhood, etc. Other triggers include smoking, attitude, etc. n/a, not available.

The question about sleep in a different environment (item 7 of the questionnaire) included three subcategories: sleep during vacation, sleep at weekends, and sleep in unfamiliar surroundings. Sleep during vacation was perceived as better by 21% ( n = 84), sometimes better by 30% ( n = 121), and not at all better by 49% ( n = 198). Sleep at the weekend was perceived as better by 18% ( n = 70), sometimes better by 26% ( n = 103), and not at all better by 56% ( n = 224). Sleep in unfamiliar surroundings was perceived as better by 5% ( n = 19), sometimes better by 17% ( n = 68), and not at all better by 78% ( n = 304). We consolidated the subcategories in one general environment variable. First, sleep in a different environment (in general) was considered better if a patient answered “yes (sleep better)” to at least one of the subgroups. The remaining patients were categorized into the sometimes group if they answered “sometimes” to at least one of the subcategories. Then, the remaining patients were categorized into the “no (do not sleep better)” or “no answer” category. In general, 26% indicated that they sleep better in different environments, 28% sometimes, and 37% not at all ( Table 1 ).

The question for alternative non-medical treatments (item 11) also included three subcategories: sport, sleep hygiene, and relaxation techniques. Sport only helped in 7% ( n = 26), helped sometimes in 32% ( n = 130), and did not help in 46% ( n = 185). Sleep hygiene helped in 5% ( n = 18), helped sometimes in 29% ( n = 103), and did not help in 43% ( n = 154). Relaxation techniques helped in 5% ( n = 19), helped sometimes in 32% ( n = 117), and did not help in 38% ( n = 142). We combined the subcategories into one overall variable of non-medical treatment in the same way as for item 7. In general, 9% of the patients indicated that an alternative treatment helps, 42% mentioned it helped sometimes, and 33% reported it did not help at all ( Table 1 ).

Alcohol as a sleep aid (item 9) included two subcategories: alcohol as a sleep aid for sleep onset and alcohol as a sleep aid for sleep maintenance. While 40% ( n = 112) indicated alcohol helps with SOI symptoms, it did not change sleep onset in 41% ( n = 116) and symptoms got worse in 19% ( n = 54). Alcohol helped with SMI symptoms in 11% ( n = 31), did nothing in 46% ( n = 123), and got worse in 43% ( n = 116). We also consolidated this variable. Alcohol as a sleep aid in general helped, if a patient answered “sleep got better” to at least one of the two subcategories (without a “sleep got worse” for the other category). Alcohol worsened sleep if a patient answered at least once “got worse” (without a “got better” for the other category). We added the answer option “alcohol helps sometimes” for patients that answered “got better” to one of the categories and “got worse” to the other. The remaining patients were categorized as “no change” or “no answer.” In general, alcohol helped in 16%, helped sometimes in 11%, and did not help (or even got worse) in 37% ( Table 1 ).

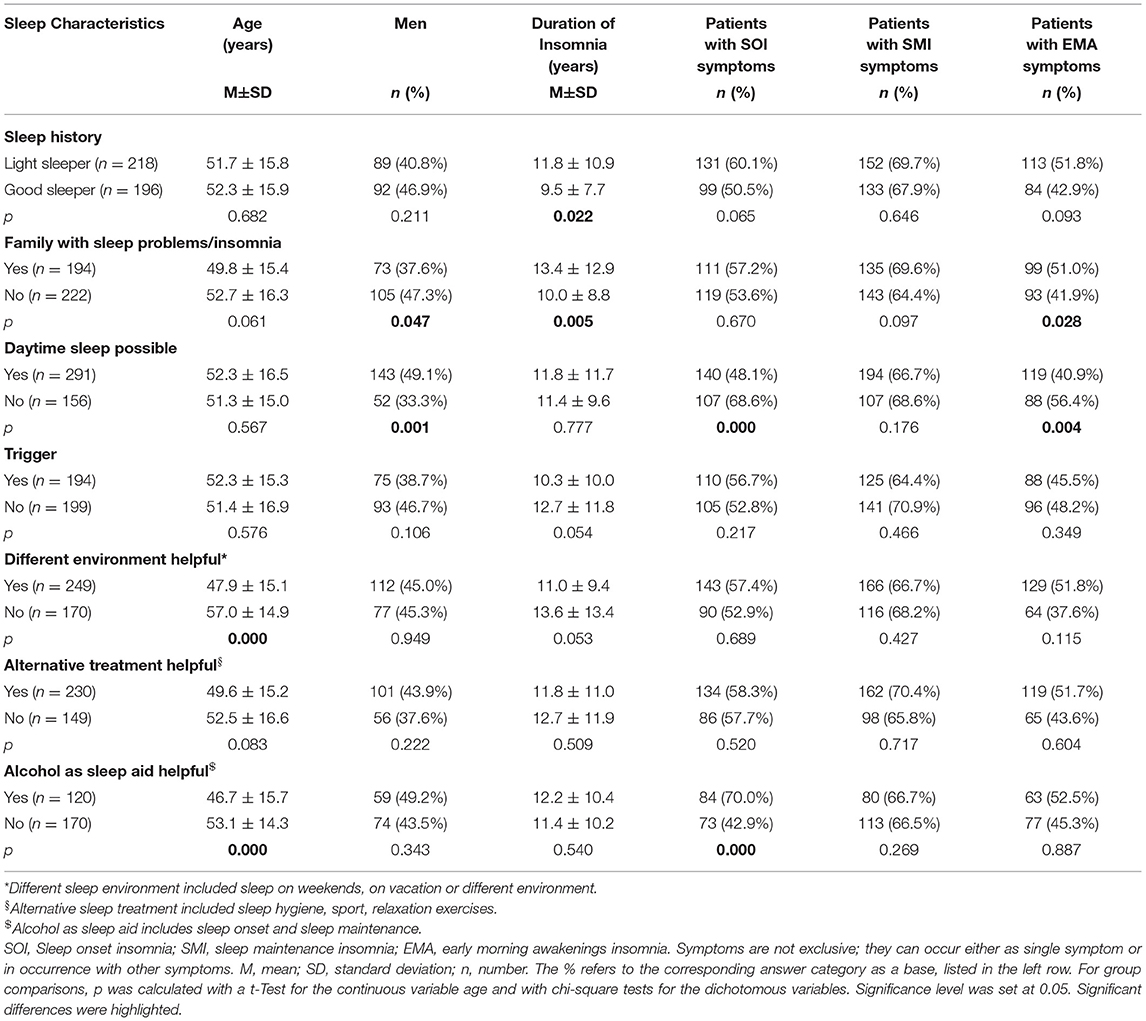

Table 2 presents a further description of insomnia subtypes based on these sleep characteristics. We dichotomized the answers into yes/no in order to create a more equal group distribution for comparison. Patients with a sleep history of being light sleepers even before insomnia onset, had significantly longer insomnia symptoms than patients with a sleep history of being good sleepers ( p < 0.05). Patients with a family history of sleep problems were significantly more frequently female ( p < 0.05), had suffered from insomnia symptoms significantly longer ( p < 0.01), and presented significantly more EMA symptoms ( p < 0.05) than patients without a family history of sleep problems. Patients who were able to sleep during the day were significantly more frequently male ( p = 0.001) and displayed fewer SOI ( p < 0.001) and fewer EMA symptoms ( p < 0.01) than patients who could not sleep during the day. Patients with no trigger displayed a tendency to having a longer insomnia duration than patients with a trigger ( p = 0.05). Patients who were able to sleep better in different environments were significantly younger ( p < 0.001) and showed a tendency to shorter insomnia duration ( p = 0.05) than patients who did not sleep better in another environment. Patients for whom alcohol helped as a sleep aid were significantly younger ( p < 0.001) and presented significantly more SOI symptoms ( p < 0.001).

Table 2 . Description of possible insomnia phenotype subgroups based on sleep characteristics.

Insomnia Symptom Subtypes and Progression

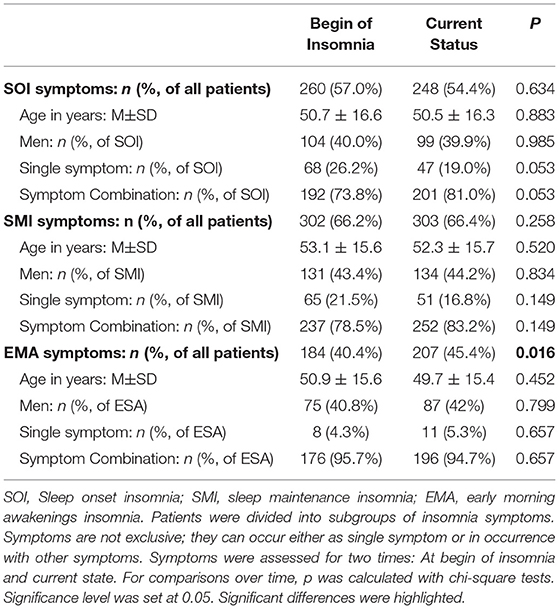

At time of visit, 54% of patients presented SOI symptoms, 66% SMI symptoms, and 45% EMA symptoms ( Table 3 ). In 57% of the patients, there was a combination of those symptoms. Patients with SOI symptoms reported on average that they needed 85.6 ± 55.0 min to fall asleep. Patients with SMI symptoms reported waking up for about 79.0 ± 58.2 min after sleep onset. And patients with EMA symptoms reported that they woke up on average 79.0 ± 56.5 min too early in the morning. Patients with EMA symptoms (not exclusively, combination of symptoms possible) had the shortest history of sleep problems (10.2 ± 9.1 years, range: 0–44 years) compared to patients with SOI symptoms (12.0 ± 9.8 years, range: 0–82 years) and patients with SMI symptoms (11.5 ± 10.6 years, range: 0–82 years). Differences were not significant.

Table 3 . Patient description by insomnia subgroups based on symptoms over time.

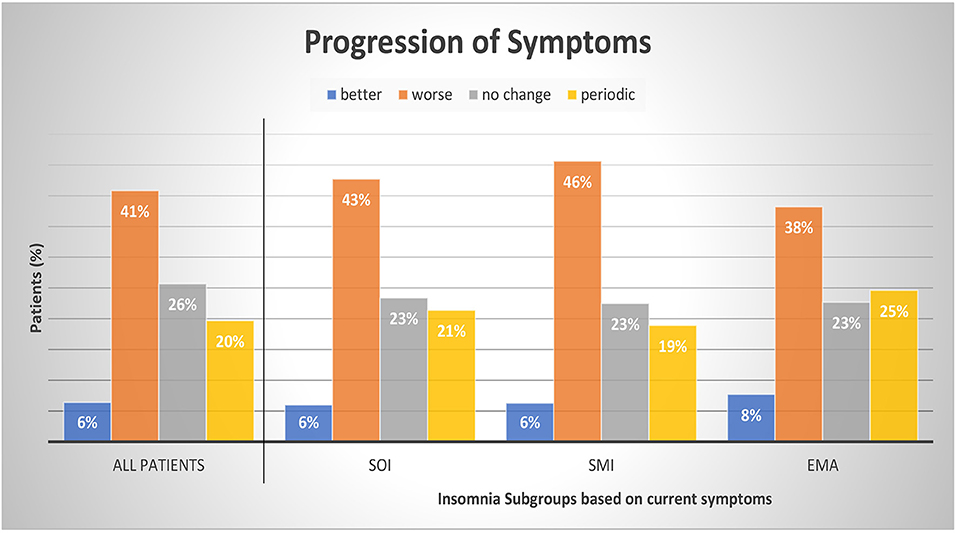

Table 3 presents the possible change of sleep symptoms over time by type of sleep symptoms. There was no significant change in SOI or SMI symptoms. Only EMA symptoms significantly increased over time ( p = 0.016). Figure 3 presents the progression in severity of the sleep disorder. Fewer than 10% reported an improvement of symptoms, while in 41% the sleep disorder got worse. In 20% the symptoms showed a periodic pattern. The progression was independent of current symptoms.

Figure 3 . Progression of symptoms by insomnia subgroups. Patients were divided into subgroups of current insomnia symptom. Symptoms are not exclusive, they can occur either as single symptom or in occurrence with other symptoms. SOI, Sleep onset insomnia; SMI, sleep maintenance insomnia; EMA, early morning awakenings insomnia. A patient with a periodic pattern of insomnia experiences weeks or months long periods with insomnia symptoms alternating with symptom free periods. For comparisons between symptom groups, p was calculated with chi-square tests. Results were not significant at a 0.05 level. The sum of the subcategories does not add up to 100% as we refrained from displaying the category “missing data and multiple answers” (7% All patients, 7% SOI, 6% SMI, and 7% EMA).

A distinct cohort of insomnia patients that reported to a special outpatient clinic for sleep disorders revealed that about 40–50% of the patients mentioned a trigger for the sleep problems, were not good sleepers to begin with (light sleepers), had a family history of sleep problems, and had a progressive course of insomnia. Over one third were not able to fall asleep during the day. Insomnia with SMI symptoms was most frequent, as well as a psychological trigger. Over time, EMA symptoms increased. Alternative non-medical treatments were only lastingly effective in fewer than 10%. Over two thirds of the patients (69%) had tried sleep medication. One of the unique traits of our cohort is the duration of the sleep problem before the visit to a specialist (over 11 years). For most, the sleep specialist/clinic is not the first point of contact. Thus, our patient cohort is not comparable to one from a general physician or population-based cohort.

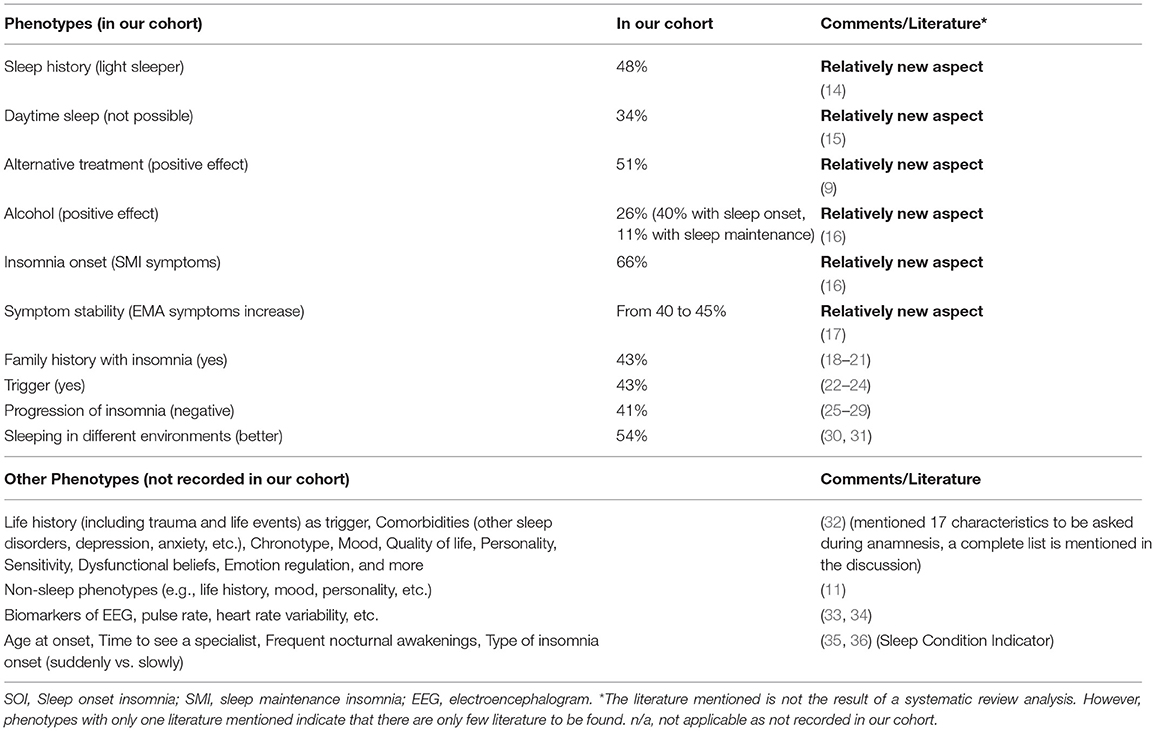

Our results emphasize the insomnia heterogeneity and the need for phenotyping. Following, we will first discuss the characteristics assessed with our questionnaire starting with some new aspects that are currently not commonly asked (history of being a light sleeper, daytime sleep, effects of alternative treatments, alcohol, temporal stability/change of insomnia symptoms). Then, we will review the current literature for further possible phenotypes. Table 4 presents an overview.

Table 4 . Overview of discussed phenotypes.

Phenotypes—Based on Our Cohort

Sleep history.

Almost half of our cohort (48%) presented a bad sleep history, indicative of an idiopathic insomnia.

There are no clear biomarkers or diagnostic criteria to distinguish between psychophysiological and idiopathic (chronic) insomnia ( 14 ). In order to identify idiopathic insomnia, we ask the patient for their sleep history, specifically before insomnia onset. Did the patient always experience poor (light) sleep, or were they a fairly good sleeper? We assume that light sleep is the pre-stage of insomnia, but not every light sleeper needs to develop insomnia, indicating that these variables are not predictors for differentiating between psychophysiological and idiopathic insomnia. Whether this distinction of good and bad sleep before developing insomnia influences therapy will need to be further investigated. Also, the term “light (bad)” sleep needs to be clearly defined and standardized.

Daytime Sleep

Using our questionnaire, we found in our cohort that 34% of patients reported not being able to take a nap during the daytime despite being tired and despite having the explicit opportunity of taking a nap. Those patients were predominantly women with more SOI and more EMA symptoms compared to patients who were able to fall asleep during the day. They did not differ regarding the duration of their insomnia symptoms.

Currently, it is not common during insomnia diagnosis to ask whether a patient is able to fall asleep during the day or to conduct a Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) for objective assessment. Our own experience with insomnia patients, however, showed how important this question is. We experienced that patients who sleep poorly at night and are tired during the day, but cannot sleep in the day either, usually have a higher degree of insomnia. They tend to suffer for more nights a week and are more resistant to therapy. In contrast, the possibility of falling asleep during the day, in front of the television, in the car, on public transport, in a meeting, or in other quiet surroundings, seems to be a sign of a lower degree of insomnia.

The ability to nap during the day has also been a criterion for other indications in the literature. The Hyperarousal Scale by Regestein et al. ( 37 ) provides indirectly a reference to the degree of alertness during the day and thus to the inability to fall asleep. Khassawneh et al. ( 38 ) used the scale together with the patient's subjective statement that they cannot nap during the day and found that patients with hyperarousal and short sleep duration have more cognitive deficits in memory tests. Li et al. ( 39 ) used the MSLT with a threshold value of 14 min to define hyperarousal. Drake et al. ( 40 ) also used the MSLT and investigated sleep disturbances due to commonly experienced stressful situations to identify factors representing the construct of “stress-related” vulnerability to sleep disturbance. Subjects with a high Ford Insomnia Response to Stress Test (FIRST) score had poorer sleep quality at night and higher latencies of sleep in the MSLT. Roehrs et al. ( 15 ) performed the MSLT in 95 patients with primary insomnia (32–64 years) and in 55 healthy sleepers and found a higher sleep latency in insomniacs (13.2 ± 4.65 min vs. 11.0 ± 4.93 min). However, the difference is small and the variability among insomniacs is high (between 2 and 20 min). The MSLT is still a questionable method for diagnosing insomnia, but it may be a possible tool for subtyping insomnia with regard to the ability to fall asleep during daytime. Espie et al. ( 41 ) examined daytime symptoms of 11,129 participants with ( n = 5,083) and without insomnia, coming from different backgrounds. Of the analyzed items (energy, concentration, relationships, ability to stay awake, mood, and ability to get through work), the items “energy” and “mood” turned out to be the two most important parameters for insomniacs, but not the item “ability to stay awake.” The importance of the criterion daytime sleepiness and/or ability to stay awake seems therefore recognized, but not yet uniformly defined and requires further research.

Alternative Treatment (Behavioral Therapy)

In our cohort, about 83% of the patients have tried at least one of these alternative non-medical behavioral treatments: sport, sleep hygiene, and/or relaxation techniques. In one third of the patients (33%) these techniques did not help. There were no significant age, gender, or symptom differences between patients with effective alternative treatments and patients where it was not effective. However, we did not investigate the severity of insomnia and it may be possible that patients where the alternative treatments did not show a positive effect may be patients with more severe insomnia.

Therapy recommendations for insomnia include a multi-modal behavioral therapy including psychological elements (e.g., CBT) as the first therapeutic step which many patients do complete, most commonly even before they arrange a visit to a specialist ( 42 ). This is also what we found in our cohort. Most of our patients have tried to educate themselves on their sleep problems, have tried to improve their sleep hygiene, have tried alternative non-medical treatments (e.g., sport, relaxation, etc.), and already went to either a natural health practitioner, homeopath, psychologist or psychotherapist. Currently, CBT is not yet good enough established in Germany as a definite treatment for insomnia. Studies have shown that CBT had less of an effect on insomniacs with short sleep duration ( 9 ). We assume that this also applies to patients with a more severe insomnia. However, severity has yet to been clearly defined. Patients will most likely show a similar reaction to phytopharmacology or alternative “smart” therapy (e.g., acoustic or electrical stimulation). A future quality check and standardization of CBT methods may be helpful in order to use the success of alternative treatment/behavioral therapy as a phenotypical criterion. We hypothesize that successful CBT is mainly linked to mild insomnia. For moderate to severe insomnia, CBT should be a necessary concomitant therapy.

In our cohort, only about 26% mentioned that alcohol helps with sleep problems in general. Patients for whom alcohol helped were significantly younger and presented more SOI symptoms. A more detailed analysis showed that alcohol helped especially with sleep onset (40%), less with sleep maintenance (only 11%). In 43% of our patients, alcohol even worsened sleep maintenance, which other studies confirmed ( 16 ). However, in almost half of our patients, alcohol showed no change.

Alcohol is a widely used sleep aid. Asking for the soporific effect of alcohol should become standard during insomnia anamnesis, as well as asking for the soporific effect of drugs (CBD, cannabis, etc.) which have become more and more a topic of sleep research ( 43 ). It is surprising that in our cohort many patients reported a lack of positive effect of alcohol as a sleep aid. It may be that the alcohol amount consumed was not high enough, as we did not ask for specifics.

Symptoms at Time of Insomnia Onset

In our cohort, 57% had SOI symptoms when the insomnia started (in 74% as a combination with other symptoms), 66% had SMI symptoms at the beginning (in 79% as a combination of symptoms), and 40% started with EMA symptoms (in 96% with other symptoms). The majority had a combination of several symptoms. Hence, in most cases of insomnia the sleep disorder started with SMI symptoms (either as single symptom or in combination). We found that patients with single SOI or single EMA were significantly younger than patients with a SOI combination (single: age 47 ± 17 years, combination: age 52 ± 16 years; p < 0.01) or EMA combination (single: age 39 ± 13 years, combination: age 51 ± 15 years; p < 0.01), respectively.

Bjorøy et al. ( 16 ) also investigated subtypes of insomnia in an extensive web-based survey with 64,503 patients who had displayed insomnia for >6 months. Here, 60% of the younger insomniacs (on average 37 years) showed SOI symptoms, either as a combination with SMI and/or EMA symptoms or as a single symptom. Confirming our own results, Bjorøy et al. ( 44 ) also found that SOI as a single symptom was more frequent in younger insomniacs, a SOI symptom combination more frequent in older insomniacs. They revealed further predictors for a symptom combination including female gender, evening chronotype, less education, and being single. While we do not assess aspects such as chronotype, they are important. Literature has shown that there is a higher insomnia prevalence in general in people with an evening chronotype. Insomniacs with a symptom combination also showed a higher comorbidity with depression, anxiety, and a higher use of alcohol and sleeping pills ( 16 ).

Symptom Stability Over Time

Not just the severity, but also the symptoms can change over time. In our cohort, prevalence of SOI and SMI symptoms did not change; EMA symptoms, however, significantly increased from 40 to 45% from first noticing those symptoms to the present (visit to a sleep specialist). Patients with SOI symptoms showed a tendency of an increase of SOI in symptom combination instead of as a single symptom (from 74 to 81%).

An early study of Hohagen et al. ( 17 ) also investigated the progression of insomnia symptoms and possible temporal stability of different patterns in 328 patients (18–65 years). In only 4 months, they discovered a >50% change in SOI, SMI, and EMA symptoms. Only in rare cases did a specific and single symptom insomnia (either SOI, SMI, or EMA) change from one to another single symptom. However, in many single symptom insomnia cases another symptom occurred over time while the first symptom stayed dominant. This tendency was also seen in our cohort regarding the SOI symptoms.

Family History

Almost half of our patient cohort (43%) reported a family history of disturbed sleep/insomnia. These patients were foremost female and presented more EMA symptoms than patients without a family history present.

A specific gene for insomnia is not known but a genetic predisposition cannot be completely ruled out ( 18 , 19 ). A twin study of children revealed a moderate inheritability of insomnia, and another study reported 35% inheritability ( 20 , 21 ).

In our cohort, almost every second patient (43%) reported a trigger. Patients with or without a trigger in our cohort did not differ regarding age, gender, and insomnia symptoms. However, those patients with no triggers showed a tendency to longer insomnia duration then the ones with a trigger. Here, it may be possible that the start of the trigger (whether sudden or slowly, unconsciously developing) may have an impact on the perception of insomnia as a chronic condition. Within our cohort, most frequently named were psychological triggers (e.g., depression, anxiety, trauma, burnout), family triggers (e.g., birth, divorce, custody battles), and medical/biological triggers including surgery and other illnesses. Work triggers (e.g., mobbing/ bulling, job loss) and stress as a separate psychological trigger came next.

Triggers are part of Spielman's theoretical model (1987) of factors causing chronic insomnia. The 3Ps consist of predisposing factors, precipitating factors which trigger acute insomnia, and perpetuating factors ( 22 , 23 ). Triggers would belong to the precipitating factors and may lead to a chronic insomnia. For a working patient, work related stress and job strain may play a bigger role as a trigger and moderator of the insomnia than for those patients that are not working ( 24 ). However, whether the existence of a trigger influences the progression or therapy of insomnia still needs to be further investigated.

Progression of Insomnia

Our patients reported most frequently a negative progression of insomnia (41%); in 26% there were no changes, and only in 7% was there an improvement. On average, the patients suffered from insomnia symptoms for about 11.6 years (range 0–82 years) before seeing a sleep specialist. Patients with predominantly EMA symptoms showed the shortest sleep problem history with 10.2 years (range 0–44 years) compared to patients with SOI or SMI symptoms. About 20% of our patients reported a periodic pattern of symptom severity.

The periodic pattern may be indicative of a non-24 h disorder ( 25 ). A patient with a periodic pattern of insomnia experiences weeks or months long periods with insomnia symptoms alternating with symptom free periods. Green et al. ( 26 ) also investigated the progression of insomnia for over 20 years in 5-year intervals. Patterns included: healthy pattern, episodic pattern, chronic pattern, and a pattern with the development of symptoms in the follow-up period. Chronic insomnia was linked to older women and the working class. It showed that social factors do affect the progression of a sleep disorder, a fact also indicated by Patel et al. ( 27 ) and Arber et al. ( 28 ). There is another distinction of insomnia subtypes by progression introduced by Wu et al. ( 29 ): persistent insomnia, remission, or relapse.

Sleep in Different Environments

Over half of our patients (54%) reported sleeping better in a different environment, including weekends/days with time off from work (51%), vacation (44%), and unfamiliar surroundings in general (22%). The category “unfamiliar surroundings” received the lowest number. Patients may have included job related hotel stays and therefore increased stress level, which may account for the lower number. Patients stating they slept better in a different environment were predominantly younger members of our cohort.

If patients reported sleeping better at weekends or on vacation, this may be an indication that the sleep disorder was caused by work stress or daily routine. In the literature, this is called behavioral induced insufficient sleep ( 30 , 31 ). As only few insomniacs are able to quit their job or family, this category may represent a specific insomnia phenotype. For those, specific interventions are possible including the end of shift work, change to home office work, change from full-time to part-time work, etc.

Further Discussion of Phenotypes

Studies suggest that insomnia is a heterogenic disorder and the identification of different phenotypes or comorbidities is important for personalized treatments ( 45 ). In our study, we presented some new aspects on what insomniacs should be asked during anamnesis and what should be considered during phenotyping. Benjamin et al. ( 32 ) already proposed the following characteristics: (1) life history including demographics, mental and physical health, trauma and life events. This study showed that more women than men and more older people than younger people suffer from insomnia and life events are usually triggers. Such triggers are mostly to be found at home, in health or at work/school, as could also be confirmed with our patients. But who reacts to such a negative trigger with insomnia and why, when, at what age, is not yet known and may possibly have a genetic reason. Further characteristics included (2) subjective sleep quality, (3) fatigue, sleepiness, hyperarousal in the daytime, (4) other sleep disorders, (5) lifetime sleep history, (6) chronotype, (7) depression, anxiety, mood, (8) quality of life, (9) personality, (10) worry, rumination, self-consciousness, sensitivity, (11) dysfunctional beliefs, (12) self-conscious emotion regulation and coping, (13) nocturnal mentation, (14) wake resting state mentation, (15) lifestyle including physical activity and food intake, (16) body temperature, and (17) hedonic evaluation. Other possible non-sleep phenotypes included: MRI, cognition, mood, traits, history of life events, family history, PSG, sleep microstructure, genetics. Blanken et al. ( 11 ) distinguished insomnia subtypes according to the so-called non-sleep categories of life history, mood perception, and personality. Miller et al. ( 33 ) presented an insomnia cluster analysis based on neurocognitive performance, sleep-onset measures of qualitative EEG, and heart rate variability (HRV). They identified two main clusters, depending on duration of sleep (<6 h vs. >6 h). The HRV changes during falling asleep may also play a role, as may the spectral power of the sleep EEG, and parameters from the sleep hypnogram such as sleep onset latency and wake after sleep onset. In one of our own studies, we were able to demonstrate that the increased nocturnal pulse rate and vascular stiffness in insomniacs with low sleep efficiency (<80%) represented an early sign of elevated cardiovascular risk, and thus presented a useful tool for phenotyping insomnia ( 34 ). In the future, other objective characteristics may include biomarkers or radiological features ( 46 , 47 ).

Further characteristics that may play a role but have not yet been mentioned or investigated are the age of the patient during insomnia onset, frequent nocturnal awakenings, the time it takes to see a specialist, and the kind of insomnia onset, slowly progressing or suddenly unexpected. There is no defined age at which the likelihood of insomnia increases, but we know that menopause is a major trigger for women. Grandner et al. ( 35 ) were able to show that getting older alone is not a predictor of insomnia, it rather includes multifactorial events. The question of how long it takes to see a specialist is also part of the Sleep Condition Indicator (SCI) by Espie et al. ( 36 ). They asked whether the insomnia had lasted longer than a year, 1–2, 3–6, or 7–12 months. We can easily agree with such a classification in terms of content. Many patients who wake up frequently at night consider this an insomnia with SMI symptoms. Frequent nocturnal awakenings, but with the ability to fall asleep again straight away, are according to the definition not considered a SMI insomnia. We did not address this in the present study, which presents a limitation. While it is mentioned in the DSM-5 as an independent sign of insomnia, patients affected by frequent nocturnal but subjectively normal sleep lengths and still restful sleep do not (yet) have insomnia. Whether it is an independent phenotype or a preliminary stage of a SMI insomnia should be further examined and defined. It also needs to be clarified whether devices for sleep registration help us with phenotyping. Polysomnography is certainly a very strong phenotypic feature when sleep time is very short, wake times after sleep onset is high and deep and/or dream sleep and sleep efficiency are not optimal. However, the current status is such that it is not suitable for diagnosis ( 48 ). In the near future, technical advances will help to provide objective, long-term sleep data, which are important for diagnosis, subtyping, and therapy for different types of insomnia.

Currently, questionnaires have been used to assess insomnia. The most known questionnaires include the ISI and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI). These are valid instruments ( 6 , 49 ). However, there are a number of other questionnaires used for insomnia such as the Amsterdam Resting-State Questionnaire (ARSQ), Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes About Sleep Scale (DBAS), Sleep-Related Behaviors Questionnaire (SRBQ), Sleep Functional Impact Scale (SFIS), Leeds Sleep Evaluation Questionnaire (LSEQ), Glasgow Sleep Effort Scale (GSES) ( 50 – 55 ). In 2014, Espie et al. ( 36 ) introduced the SCI which presented a good instrument for identifying the presence of insomnia and also allowed for time differentiation. Also, the short version with only 2 questions seems valid, where questions are asked about the number of nights in the past month with poor sleep and about the trouble in general caused by sleep ( 56 ). Kalmbach et al. ( 57 ) presented a differentiation between good and bad sleepers based on the Presleep Arousal Scale—Cognitive (PSAS-C) and—Somatic (PSAS-S). People with a high PSAS-C have higher sleep latency and wake times after sleep onset, as well as higher MSLT latency and lower sleep efficiency and total sleep time. The PSAS-C in particular seems to be a good measure of the hyperarousal state. Research and official expert recommendations will show which questionnaires should be favored in clinical practice.

Limitations

Our study intended to encourage and further the discussion on insomnia heterogeneity and the need for possible phenotyping. While we introduced some new aspects of phenotyping, we neither provided a complete list of possible phenotypes nor defined specific clusters. Limitations of our study include the fact that further important aspects (e.g., comorbidity, employment, having children, chronotype, employment etc.) may need consideration. Also, some aspects of the questionnaire will need a more precise definition (e.g., light sleeper, daytime napping, weekend/vacation, alternative treatment, alcohol use), patients were not differentiated regarding sleep duration (<6 h vs. >6 h), and the progression of insomnia was observed retrospectively and not investigated prospectively. While our study was performed with patients of a sleep center, there is also need for phenotyping and thorough assessment of those phenotype characteristics in patients of a primary care setting.

As part of a specific Research Topic introduced by Frontiers on the heterogeneity of insomnia, our study provides further ideas on the already existing approaches to phenotyping insomnia patients. The aim of our study was not to examine all conceivable phenotypic features of insomnia, but to help document specific characteristics with simple questions about the onset and course of insomnia during anamnesis. While the clinical relevance of some of those possible phenotypes is not yet clear (e.g., sleep history, trigger, daytime sleep, sleep in a different environment, alternative treatment, insomnia progression/symptom stability etc.), they should play a role in future research and medical care of insomnia patients. We would like to give an impulse for further research in this area, in order to better differentiate insomnia, thus leading to more effective individualized therapy.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

IF, TP, and VK had the role of supervision and conceptualized the study. IF was responsible for data collection. NL performed data analysis. All authors were involved in visualization and writing including data interpretation, result discussion, and drafting and reviewing the manuscript.

This was not an industry supported study. The study was initiated and funded by the Charité—Universitätsmedizin Berlin owned funding.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the patients that participated, and Hendrik Straße and Sandra Zimmermann involved in data entry and processing.

1. Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev. (2002) 6:97–111. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2002.0186

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Daley M, Gregoire JP, Merette C. Epidemiology of insomnia: prevalence, self-help treatments, consultations, and determinants of help-seeking behaviors. Sleep Med. (2006) 7:123–30. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2005.08.008

3. Krystal AD, Prather AA, Ashbrook LH. The assessment and management of insomnia: an update. World Psychiatry. (2019) 18:337–52. doi: 10.1002/wps.20674

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

4. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders . 3rd ed. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine (2014).

Google Scholar

5. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Section II: Diagnostic Criteria and Codes: Sleep-Wake Disorders . 5th ed. Arlingten, VA: American Psychiatric Association (2013).

6. Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the nsomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. (2001) 2:297–307. doi: 10.1016/S1389-9457(00)00065-4

7. Vgontzas AN, Fernandez-Mendoza J, Liao D, Bixler EO. Insomnia with objective short sleep duration: the most biologically severe phenotype of the disorder. Sleep Med Rev. (2013) 17:241–54. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.09.005

8. Wallace ML, Lee S, Hall MH, Stone KL, Langsetmo L, Redline S, et al. Heightened sleep propensity: a novel and high-risk sleep health phenotype in older adults. Sleep Health. (2019) 5:630–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2019.08.001

9. Bathgate CJ, Edinger JD, Krystal AD. Insomnia patients with objective short sleep duration have a blunted response to cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Sleep. (2017) 40: zsw012. doi: 10.1093/sleepj/zsx050.334