- Get new issue alerts Get alerts

- Submit a Manuscript

Secondary Logo

Journal logo.

Colleague's E-mail is Invalid

Your message has been successfully sent to your colleague.

Save my selection

Conceptual Models and Theories

Developing a research framework.

Premkumar, Beulah M.Sc (N)., M.Phil * ; David, Shirley M.Sc (N)., Ph.D (N) ** ; Ravindran, Vinitha M.Sc (N)., Ph.D (N) ***

* Professor, College of Nursing, CMC, Vettore

** Professor, College of Nursing, CMC, Vettore

*** Professor, College of Nursing, CMC, Vettore

Conceptual models and theories provide structure for research. Research without a theoretical base provides isolated information which may not be used or applied effectively. The challenge for nurse researchers is to identify a model or theory that would a best fit for their area of study interest. In this research series article the authors unravel the simple steps that can be followed in identifying, choosing, and applying the constructs and concepts in the models or theories to develop a research framework. A research framework guides the researcher in developing research questions, refining their hypotheses, selecting interventions, defining and measuring variables. Roy's adaptation model and a study intending to assess the effectiveness of grief counseling on adaptation to spousal loss are used as an example in this article to depict the theory- research congruence.

Introduction

The history of professional Nursing started with Florence Nightingale who envisioned nurses as a knowledgeable force who can bring positive changes in health care delivery (Alligood, 2014). It was 100 years later, during 1950s, a need to develop nursing knowledge apart from medical knowledge was felt to guide nursing practice. This beginning led to the awareness of the need to develop nursing theories (Alligood, 2010). Until then, nursing practice was based on principles and traditions that were handed down through apprenticeship model of education and individual hospital procedure manuals. It reflected the vocational heritage more than a professional vision. This transition from vocation to profession involves successive eras of history in nursing: the curriculum era, research emphasis era, research era, graduate education era, and the theory era (Alligood, 2014).

The theory era was a natural outcome of research era and graduate education era, where an understanding oí research and knowledge development increased. It became obvious that research without conceptual and theoretical framework produced isolated information. This awareness and acceptance paved way to another era, the theory utilization era, which placed emphasis on theory application in nursing practice, education, administration, and research (Alligood, 2014). Conceptual models and theories are structures that provide nurses with a perspective of the patient and the professional practice. Conceptual models provide structure for a phenomenon, direct thinking, observations, and interpretations and further provide direction for actions (Fawcett & Desanto-Madeya, 2005). In research, a framework is the underpinning of the study and if a framework is based on a theory it is called as theoretica framework and if it represents a conceptual model then it is generally called the conceptual framework. More often it is known as a research framework. However the terms conceptual framework, conceptual model theoretica framework, and research framework are often usee interchangeably (Polit & Beck, 2014).

Definitions of Terminologies

When nurse researchers are making decisions about theories and models for their study, it is important to understand the definitions of different related terminology. According Grove, Burns and Gray (2013) conceptual models are examples of grand theories and are highly abstract with related constructs. “A conceptual model broadly explains phenomenon of interest, expresses assumption, and reflects a philosophical stance” (Grove et al., 2013). A conceptual model is an image of a phenomenon. A theory in contrast represents a set of defined concepts that offers a systematic explanation about how two or more concepts are interrelated. Theories can be used to describe, explain, predict, or control the phenomenon that is of interest to a researcher (Grove et al., 2013).

Constructs are abstract descriptions of a phenomenon or the experiences or the contextual factors. Concepts are the terms or names given to a phenomena or idea or an object and are often considered as the building blocks of a theory (Grove et al., 2013). Many conceptual models are made of constructs. Concepts are derived from constructs or vice versa. For example, in the Transactional model of Stress and Coping by Lazarus and Folkman (1984) the constructs included are stressors, mediating processes, moderators and the outcomes. The examples of related concepts to these constructs are shown in Figure 1 .

Conceptual Framework in Research

Conceptual models and theories serve as the foundation on which a study can be developed or as a map to aid in the design of the study (Fawcett, 1989). When concepts related to the study are integrated and formulated into a workable model for the specific study it is generally known as a research framework (Grove, Gray & Burns, 2015). When concepts or constructs in the models or theory are converted into measurable terms they are known as variables (Grove et al., 2013). According to the purposes explicated by Sharma (2014) and Polit and Beck (2014) the use of conceptual/research framework m research can be summarized as follows:

- - It provides a structure for the study which helps the researcher to organize the process of investigation

- - It helps in formulating hypothesis, developing a research question and defining the variables

- - It guides development, use, and testing of interventions and selection of data collection instruments

- - It provides direction for explaining the study results and situate the findings in the gaps identified in the literature

Nurse researchers regularly select and use conceptual frameworks for carrying out their studies. Conceptual models and theories explicitly or implicitly guide research (Radwin & Fawcett, 2002). Researchers use both nursing and non- nursing models to provide a framework for their studies. There are however, two challenges for researchers and students in relation to using conceptual frameworks in their investigations. The first is to identify the conceptual model or a theory that will be the best fit and will be useful in guiding their research and the second is to incorporate and clearly articulate the model in relation to their study variables, interventions and the outcomes to convert it into their research framework (Radwin & Fawcett, 2002). A few essential steps need to be followed to choose a conceptual model and to incorporate it into the individual studies. Let us consider the steps with an example of a study intending “ to assess the effectiveness of grief counseling intervention in helping individuals cope and adapt after the loss of their spouse”.

1. The Purpose of the Study

The choice of conceptual model to guide the research first and foremost depends on the purpose of one's research. It can be educating staff/patient/families, improving academic and clinical teaching, changing practice by translating research evidence into practice, implementing a quality improvement strategy, encouraging behavior change, supporting individuals during crisis, assisting to cope etc. The researcher should look for a model or a theory that addresses similar purpose. It would be useful to identify and select the key concept in which the researcher is interested in at this stage (Sharma, 2014). In the example mentioned above the key concept of interest is ‘adaptation’ after a loss which is a traumatic life event.

2. Study Variables

The second step is to identify general variables that are included or may be included in the study. The variables are related to the constructs/concepts of interest in the study. The concepts and variables may be based on previous research findings, experiential knowledge or hunches and intuitions (Sharma, 2014). In the adaptation to spousal loss study in addition to the main concept of adaptation, other variables such as grief, coping, quality of life, and demographic and social factors that may influence adaptation may be included in the objectives.

3. Gathering Relevant Information

Once the researcher has identified the concepts and variables of interest, the next step involves in-depth study of existing models and theories to gather information about the relevant concepts and variables. The researcher can quickly skim through the literature to seek a few models that relate to the concepts and variables of interest in the study. The researcher must then read about them from primary sources to obtain comprehensive evidence about each model or theory (Sharma, 2014). When choosing a model for the study the researcher needs to analyze and evaluate the models she /he considers to understand its most important features (Fawcett, 1989). Some questions that need to be asked are: What is the historical evolution of the model? What methods are indicated for nursing knowledge development? What are the assumptions listed? How are the concepts person, environment, health, and nursing defined? How are these metaparadigm concepts linked and how is nursing process described? What is the major area of concern in the care identified in the model?

The researcher's previous experience and knowledge about theories and models greatly assist in quick decisions on choosing a model that would best fit their study purpose. Nurse researchers who have an interdisciplinary knowledge and experience may choose an overarching model or theory to develop their research framework for their study. It is the novice researchers who often find it difficult to decide on a model and have confusions regarding explicating their research framework. The above listed questions, if carefully considered will help them in choosing an appropriate model. Once a theory or conceptual model is identified the researcher need to studv it in-depth to understand each concent and propositions so that it can appropriately be integrated into the study (Sharma, 2014).

In the study example in this paper the researcher intends to assess how people adjust after the death of their spouse and how grief counseling will help in their adjustment to life after their loss. As the process of interest, as indicated already, is adaptation to traumatic life event, adaptation model that is purported by Sr. Callista Roy (1976) is chosen as the best fit as Roy's adaptation model focuses on how individuals cope after a stimuli and manifest adaptive behaviors (see Figure 2 ).

4. Understanding the Premises and Principles of the Selected Model: Roy's Conceptual Model

Once a model that is relevant to the study is selected the underlying premises and philosophy of the model or theory have to be explicated. The definitions of the concepts in the model have to be understood to enable the researcher to formulate her/his study framework which can be integrated with the chosen model (Mock et al., 2007). An in-depth review of literature on how the conceptual model was developed and refined, background information about the theorist or author, and the definitions of concepts included in the model is mandatory to examine how the researcher's study can be designed and executed. In Roy's adaptation model (Fawcett, 1989), Roy considers human being as an open system who is in constant interaction with the environment. She explains health as a process of being or becoming an integrated whole person. The goal of nursing is to assist individuals in positively adapting to environmental changes or what she terms ‘stimuli’. Three types of stimuli are explained in the model: 1. ‘Focal’ which is the life event itself, 2. ‘contextual’ which are the factors associated and contributing to or opposing the stimuli and 3.‘residual’ which are present innately which may not be altered, explained, or reasoned. The adaptation occurs through coping process at the regulator and cognator subsystem levels. The regulator subsystem refers to the automatic response that occurs naturally in the chemical, neural, and endocrine systems. The cognator subsystem respond through four cognitive emotional channels: perceptual and information processing, learning, judgment, and emotion. Adaptation in Roy's model is explained as conscious choice of individuals to create successful human and environmental integration which can be manifested as integrated adaptation in four adaptive behavioural modes. The four adaptive modes are the physical/physiological, self-concept, role functioning, and interdependence. If integrated adaptation did not happen it can result in compensatory or compromised adaptation.

5. Finalizing the Study Design, Variables, Tool, and Intervention

In a nursing theory or a conceptual model how a theorist defines nursing action and what is expected as outcomes helps the researcher to choose the research design and intervention (Mock et al., 2007). Further the concepts in the model guides the researcher to choose variables that would be of interest to nursing. In Roy's adaptation theory, nursing assessment and interventions that promote adaption is purported. On the basis of this premise the investigator can choose a specific intervention that would enhance integrated adaptation of an individual after a crisis (stimuli). The investigator then can measure whether the intervention has been effective in promoting adaptation by looking at the four modes of adaptive behavior (physical/physiological, self- concept, role functioning, and interdependence). The congruence of the constructs of Roy's adaptation model and the study variables is depicted in Figure 3 .

In the example being discussed the focal stimuli is the death of a spouse. The contextual stimuli are the grief reaction, social and spiritual support systems available for the person who has experienced loss and her or his economic status. The residual stimuli include variables such as the age, gender, years spent with spouse, race, or ethnic background. The researcher has chosen grief counseling as the intervention in the study. This is based on Roy's model which explains that when interventions are aimed at how contextual stimuli can be addressed it will result in better coping process and this will facilitate adaptation (Fawcett, 1989). When choosing the intervention it is vital to know that there is established evidence for the intervention (Mock et al., 2007). In this study grief counseling is chosen because of its established evidence on the effect on person's adjustment (Neimeyer & Currier, 2009). Other variables which relate to the adaptation model include coping with grief and the outcome variables as adaptive behaviours in physiological, interpersonal, role functioning, and self-concept domains (see Figure 3 ).

Once there is clarity about the variables of interest and the intervention, it becomes relatively simpler to decide on the study design and the instruments/tools which can be used to measure the variables. As shown in Figure 4 , the contextual variables can be measured using a socio-demographic data profile. Grief which is another contextual stimuli will be measured by the grief scale (Fireman, 2010). The grief scale measures the thoughts, feelings, and behaviours of people who are in the grieving process after a loss. A part of the demographic profile will measure the influence of the residual variables. The intervention which is the grief counseling will be administered by the researcher who has had special training in this method of counseling. How individuals cope to loss can be measured by the Ways of Coping Scale (Folkman & Lazarus, 1988). This scale consists of coping in eight domains namely problem focused coping, wishful thinking, distancing, seeking social support emphasizing the positive, self-blame, tension reduction, and self-isolation. The coping and the adaptation behaviors may be measured using the “Coping and Adaptation Processing Scale” (CAPS Short form, 2015) which is developed by Roy herself. CAPS is a tool which can be used to measure coping and adaptation in people suffering with chronic or acute health issues and can be used when the stimuli is an acute loss.

As the researcher intends to use grief counseling as an intervention, the research design will be an experimental design and the coping and adaptation process can be measured prior to and after the counseling sessions using both ways of coping and CAPS scales. As there may not be adequate number of samples available to represent the phenomenon of interest the study can be designed as a one group pretest posttest quasi experimental design instead a true experimental design with a control group. The research framework that is developed from the adaptation model may be modified as follows based on the research design (see Figure 4 ).

6. Using the Research Framework for Analysis and Interpretation of the Results

The framework that is developed for the study can guidi the analysis and will also help in interpretation of the finding The research report can easily incorporate the concepts in th(original model and also the developed framework and can b< discussed in relation to current study findings. As th(researcher's background knowledge that is gained in th(framework development process is elaborate, the concepts o: the model can guide the researcher to situate the findings wit! in the theoretical literature (Mock et al., 2007).

Choosing and applying a conceptual model or theory to develop a research frame work is a challenging but an educative process. It also involves an iterative process of moving back and forth between what is the phenomenon and variables of interest to the researcher and what and how the theorists explain and define concepts in their models. The first and foremost step to be remembered is to identify the core concept that the researcher is interested in which will pave way for searching the literature on the model that will match the researcher's interest. The researcher must understand that all variables in a given model may not be of interest to him or her or variables from more than one model may apply to the areas of interest to be studied. Both are acceptable. Researchers need to be creative in developing the research framework based on the model/models that is/are of interest. The nursing conceptual models serve as guides for articulating, reporting and recording nursing thought anc action in research. Further, the models also ultimately assist researchers in applying findings in clinical practice.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

- View Full Text | PubMed | CrossRef

conceptual model; theory; research framework; Roy's adaptation model; spousal loss; grief

- + Favorites

- View in Gallery

Readers Of this Article Also Read

Non-pharmacological intervention approaches for common symptoms in advanced..., exploring issues in theory development in nursing: insights from literature.

Designing conceptual articles: four approaches

- Theory/Conceptual

- Open access

- Published: 09 March 2020

- Volume 10 , pages 18–26, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Elina Jaakkola ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4654-7573 1

168k Accesses

546 Citations

43 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

As a powerful means of theory building, conceptual articles are increasingly called for in marketing academia. However, researchers struggle to design and write non-empirical articles because of the lack of commonly accepted templates to guide their development. The aim of this paper is to highlight methodological considerations for conceptual papers: it is argued that such papers must be grounded in a clear research design, and that the choice of theories and their role in the analysis must be explicated and justified. The paper discusses four potential templates for conceptual papers – Theory Synthesis, Theory Adaptation, Typology, and Model – and their respective aims, approach for using theories, and contribution potential. Supported by illustrative examples, these templates codify some of the tacit knowledge that underpins the design of non-empirical papers and will be of use to anyone undertaking, supervising, or reviewing conceptual research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Conceptual review papers: revisiting existing research to develop and refine theory

A Framework for Undertaking Conceptual and Empirical Research

Advancing marketing theory and practice: guidelines for crafting research propositions

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The major academic journals in the field of marketing acknowledge the need for good conceptual papers that can “bridge existing theories in interesting ways, link work across disciplines, provide multi-level insights, and broaden the scope of our thinking” (Gilson and Goldberg 2015 , p. 128). Indeed, many of the most impactful marketing papers of recent decades are conceptual as this type of research enables theory building unrestricted by the demands of empirical generalization (e.g., Vargo and Lusch 2004 ). Authors crafting conceptual papers can find valuable advice on problematizing (Alvesson and Sandberg 2011 ), theorizing and theory building (Corley and Gioia 2011 ; Cornelissen 2017 ; Shepherd and Suddaby 2017 ), and the types of conceptual contribution that warrant publication (Corley and Gioia 2011 ; MacInnis 2011 ). However, a lack of commonly accepted templates or “recipes” for building the paper means that writing a conceptual piece can be a struggle (Cornelissen 2017 ). As a result, reviewers often face conceptual papers that offer little more than a descriptive literature review or interesting but disjointed ideas.

In empirical papers, the recipe typically is the research design that provides the paper structure and logic, guiding the process of developing new knowledge and offering conventions for reporting the key elements of the research (Flick 2018 , p. 102). The research design explains how the ingredients of the study were selected, acquired, and analyzed to effectively address the research problem, and reviewers can evaluate the robustness of this process by reference to established conventions in the existing literature. As conceptual papers generally do not fit the mold of empirical research, authors and reviewers lack any such recipe book, making the critical issue of analytical rigor more challenging.

This paper addresses issues of methodology and research design for conceptual papers. The discussion is built on previous “how to” guides to conceptual research, and on examples from high quality journals to identify and illustrate different options for conceptual research design. This paper discusses four templates—Theory Synthesis, Theory Adaptation, Typology, and Model—and explicates their aims, their approach to theory use, and their contribution potential. The paper does not focus on theory building itself but supports it, as analytical rigor is a prerequisite for high quality theorizing. Nor is the focus on literature reviews or meta-analyses; while these are important non-empirical forms of research, there are well articulated existing guidelines for such articles (see for example Webster and Watson 2002 ; Palmatier et al. 2018 ).

The ultimate goal of this paper is to direct scholarly attention to the importance of a systematic approach to developing a conceptual paper. Experienced editors and reviewers have noted that researchers sometimes underestimate how difficult it is to write a rigorous conceptual paper and consider this an easy route to publishing—an essay devoid of deeper scholarship (Hirschheim 2008 ). In reality, developing a cogent argument and building a supporting theoretical explanation requires tacit knowledge and skills that doctoral programs seldom teach (Yadav 2010 ; King and Lepak 2011 ). As Fulmer puts it, “in a theoretical paper the author is faced with a mixed blessing: greater freedom and page length within which to develop theory but also more editorial rope with which to hang him/herself” ( 2012 , p. 330).

The paper is organized as follows. The next section outlines key methodological requirements for conceptual studies. Four common types of research design are then identified and discussed with supporting examples. The article ends with conclusions and recommendations for marketing scholars undertaking, supervising, or reviewing conceptual research.

Conceptual papers: some methodological requirements

The term “research design” refers to decisions about how to achieve research goals, linking theories, questions, and goals to appropriate resources and methods (Flick 2018 , p. 102). In short, the research design is a plan for collecting and analyzing evidence that helps to answer the question posed (Ragin 1994 , p. 191). Like any design, the research design should improve usability ; a good research design is the optimal tool for addressing the research problem, and it communicates the logic of the study in a transparent way. In principle, any piece of research should be designed to deliver trustworthy answers to the question posed in a credible and justified manner.

An empirical research design typically involves decisions about the underlying theoretical framing of the study as well as issues of data collection and analysis (e.g. Miller and Salkind 2002 ). Imagine, for example, an empirical paper where the authors did not argue for their sampling criteria or choice of informants, or failed to define the measures used or to show how the results were derived from the data. It can be argued that conceptual papers entail similar considerations (Table 1 ), as the omission of equivalent elements would create similar confusion. In other words, a well-designed conceptual paper must explicitly justify and explicate decisions about key elements of the study. The following sections elaborate more specifically on designing and communicating these “methodological” aspects of conceptual papers.

Explicating and justifying the choice of theories and concepts

Empirical and conceptual papers ultimately share a common goal: to create new knowledge by building on carefully selected sources of information combined according to a set of norms. In the case of conceptual papers, arguments are not derived from data in the traditional sense but involve the assimilation and combination of evidence in the form of previously developed concepts and theories (Hirschheim 2008 ). In that sense, conceptual papers are not without empirical insights but rather build on theories and concepts that are developed and tested through empirical research.

In an empirical study, the researcher determines what data are needed to address the research questions and specifies sampling criteria and research instruments accordingly. In similar fashion, a conceptual paper should explain how and why the theories and concepts on which it is grounded were selected. In simple terms, there are two possible points of departure. The first option is to start from a focal phenomenon that is observable but not adequately addressed in the existing research. The authors may inductively identify differing conceptualizations of that phenomenon, and then argue that the aspect of interest is best addressed in terms of particular concepts or theories. That is, the choice of concepts is based on their fit to the focal phenomenon and their complementary value in conceptualizing it. One key issue here is how the researcher conceptualizes the empirical phenomenon; in selecting particular concepts and theories, the researcher is de facto making an argument about the conceptual ingredients of the empirical phenomenon in question.

A second and perhaps more common approach is to start from a focal theory by arguing that a particular concept, theory, or research domain is internally incoherent or incomplete in some important respect and then introducing other theories to bridge the observed gaps. In this case, the choice of theories or concepts is based on their ability to address the observed shortcoming in the existing literature, i.e. their supplementary value. This simplified account raises a critical underlying question: what is the value that each selected concept, literature stream, or theory brings to the study, and why are they selected in preference to something else?

Explicating the role of different theories and concepts in the analysis

Conceptual papers typically draw on multiple concepts, literature streams, and theories that play differing roles. It is difficult to imagine a (published) empirical paper where the reader could not distinguish empirical data from the literature review. In a conceptual paper, however, it is sometimes difficult to tell which theories provide the “data” and which are framing the analysis. In this regard, Lukka and Vinnari ( 2014 ) drew a useful distinction between domain theory and method theory. A domain theory is “a particular set of knowledge on a substantive topic area situated in a field or domain” (ibid, p. 1309)—that is, an area of study characterized by a particular set of constructs, theories, and assumptions (MacInnis 2011 ). A method theory, on the other hand, is “a meta-level conceptual system for studying the substantive issue(s) of the domain theory at hand” (Lukka and Vinnari 2014 , p. 1309). For example, Brodie et al. ( 2019 ) sought to advance engagement research (domain theory) by drawing new perspectives from service-dominant logic (method theory). The distinction is relative rather than absolute; whether a particular theory is domain or method theory depends on its role in the study in question (Lukka and Vinnari 2014 ). Indeed, a single study can accommodate multiple domain and method theories.

In a conceptual paper, one crucial function of the research design is to explicate the role of each element in the paper; failure to explain this is likely to render the logic of “generating findings” practically invisible to the reader. Defining the roles of different theories also helps to indicate the paper’s positioning, and how its contribution should be evaluated. Typically, the role of the method theory is to provide some new insight into the domain theory—for example, to expand, organize, or offer a new or alternative explanation of concepts and relationships. This means that contribution usually centers on the domain theory, not the method theory (Lukka and Vinnari 2014 ). For example, marketing scholars often use established theories such as resource-based theory, institutional theory, or practice theory as method theories, but any suitable framework (even from other disciplines) can play this role. Footnote 1

Making the chain of evidence visible and easy to grasp

Conceptual papers typically focus on proposing new relationships among constructs; the purpose is thus to develop logical and complete arguments about these associations rather than testing them empirically (Gilson and Goldberg 2015 ). The issue of how to develop logical arguments is hence pivotal. As well as arguing that concepts are linked, authors must provide a theoretical explanation for that link. As that explanation demonstrates the logic of connections between concepts, it is critical for theory building (King and Lepak 2011 ).

In attempting to analyze what constitutes a good argument, Hirschheim ( 2008 ) adopted a framework first advanced by the British philosopher Toulmin ( 1958 ), according to which an argument has three necessary components: claims, grounds, and warrants. Claims refer to the explicit statement or thesis that the reader is being asked to accept as true—the outcome of the research. Grounds are the evidence and reasoning used to support the claim and to persuade the reader. In a conceptual paper, this evidence is drawn from previous studies rather than from primary data. Finally, warrants are the underlying assumptions or presuppositions that link grounds to claims. Warrants are often beliefs implicitly accepted within the given research domain—for example the assumption that organizations strive to satisfy their customers. In a robust piece of research, claims should be substantiated by sufficient grounds, and should be of sufficient significance to make a worthwhile contribution to knowledge (Hirschheim 2008 ).

In practice, the chain of evidence in a conceptual paper is made visible to the reader by explicating the key steps in the argument. How is the studied phenomenon conceptualized? What are the study’s implicit assumptions, stemming from its theoretical underpinnings? Are the premises and axioms used to ground the arguments sufficiently explicit to enable another researcher to arrive at similar analytical conclusions? Conceptual clarity, parsimony, simplicity, and logical coherence are important qualities of any academic study but are arguably all the more critical when developing arguments without empirical data.

A paper’s structure is a strong determinant of how easy it is to follow the chain of argumentation. While there is no single best way to structure a conceptual paper, what successful papers have in common is a careful matching of form and structure to theoretical purpose of the paper (Fulmer 2012 ). The structure should therefore reflect both the aims of the research and the role of the various lenses deployed to achieve those aims—in other words, the structure highlights what the authors seek to explain. A clear structure also contributes to conceptual clarity by making the hierarchy of concepts and their elements intuitively available to the reader, eliminating any noise that might distort the underlying message. As Hirschheim ( 2008 ) noted, a clear structure ensures a place for everything—omitting nothing of importance—and puts everything in its place, avoiding redundancies.

Common types of research design in conceptual papers

In marked contrast to empirical research, there is no widely shared understanding of basic types of research design in respect to conceptual papers, with the exception of literature reviews and meta-analyses. To address this issue, the present study considers four such types: Theory Synthesis, Theory Adaptation, Typology , and Model (see Table 2 ). These types serve to clarify differences of methodological approach—that is, how the argument is structured and developed—rather than the types of conceptual contributions that are the main consideration of MacInnis ( 2011 ). The four types discussed here derive from an analysis of goal setting, structuring, and logic of argumentation in multiple articles published in high quality journals. It should be said that the list is not exhaustive, and other researchers would no doubt have formulated differing perspectives. Nevertheless, the presented scheme can inspire researchers to explore and explicate one’s approach to conceptual research, and perhaps to formulate an alternative approach. It should also be noted that the goals of a conceptual article can be as varied as in any other form of academic research. Table 2 identifies some possible or likely goals for each suggested type; these are not mutually exclusive and are often combined.

Theory synthesis

A theory synthesis paper seeks to achieve conceptual integration across multiple theories or literature streams. Such papers offer a new or enhanced view of a concept or phenomenon by linking previously unconnected or incompatible pieces in a novel way. Papers of this type contribute by summarizing and integrating extant knowledge of a concept or phenomenon. According to MacInnis ( 2011 ), summarizing helps researchers see the forest for the trees by encapsulating, digesting, and reducing what is known to a manageable whole. Integration enables researchers to see a concept or phenomenon in a new way by transforming previous findings and theory into a novel higher-order perspective that links phenomena previously considered distinct (MacInnis 2011 ). For example, a synthesis paper might chart a new or unstructured phenomenon that has previously been addressed in piecemeal fashion across diverse domains or disciplines. Such papers may also explore the conceptual underpinnings of an emerging theory or explain conflicting research findings by providing a more parsimonious explanation that pulls disparate elements into a more coherent whole.

This kind of systematization is especially helpful when research on a given topic is fragmented across different literatures, helping to identify and underscore commonalities that build coherence (Cropanzano 2009 ). For example, in their review of conceptualizations of customer experience across multiple literature fields, Becker and Jaakkola’s ( 2020 ) analysis of the compatibility of various elements and assumptions provided a new integrative view that could be generalized across settings and contexts. In more mature fields, synthesis can help to identify gaps in the extant research, which is often the goal of systematic literature reviews. However, gap spotting is seldom a sufficient source of contribution as the main aim of a conceptual paper should be to enhance existing theoretical understanding on the studied phenomenon or concept. The synthesis paper represents a form of theorizing that emphasizes narrative reasoning that seeks to unveil “big picture” patterns and connections rather than specific causal mechanisms (Delbridge and Fiss 2013 ).

Although there is sometimes a fine line between theory synthesis and literature review, there remains a clear distinction between the two. While a well-crafted literature review takes stock of the field and can provide valuable insights into its development, scope, or future prospects, it remains within the existing conceptual or theoretical boundaries, describing extant knowledge rather than looking beyond it. In the case of a conceptual paper, the literature review is a necessary tool but not the ultimate objective. Moreover, in a theory synthesis paper, the role of the literature review is to unravel the components of a concept or phenomenon and it must sometimes reduce or exclude incommensurable elements. A lack of elegance occurs when authors attempt to hammer together separate research ideas in a series of “minireviews” instead of attending to a single conceptual theme (Cropanzano 2009 ). For example, a literature review that seeks to integrate multiple research perspectives may instead merely summarize in separate chapters what each has to say about the concept. Typically, different research perspectives employ differing terms and structure, or categorize conceptual elements in distinct ways. Integration and synthesis requires that the researcher explicates and unravels the conceptual underpinnings and building blocks that different perspectives use to conceptualize a phenomenon, and the looks for common ground on which to build a new and enhanced conceptualization.

A theory synthesis paper may seek to increase understanding of a relatively narrow concept or empirical phenomenon. For example, Lemon and Verhoef ( 2016 ) summarized the conceptual background and extant conceptualizations of customer journeys to produce a new integrative view. They framed the journey phenomenon in terms of the consumer purchasing process and organized the extant research within this big picture. Similarly, arguing that the knowledge base of relationship marketing and business networks perspectives was unduly fragmented, Möller ( 2013 ) deployed a metatheoretical lens to construct an articulated theory map that accommodated various domain theories, leading to the development of two novel middle-range theories.

Ultimately, a theory synthesis paper can integrate an extensive set of theories and phenomena under a novel theoretical umbrella. One good example is Vargo and Lusch’s ( 2004 ) seminal article, which pulled together key ingredients from diverse fields such as market orientation, relationship marketing, network management, and value management into a novel integrative narrative to formulate the more parsimonious framework of service-dominant logic. In so doing, they drew on resource based theory, structuration theory, and institutional theory as method theories to organize and synthesize concepts and themes from middle-range literature fields (e.g., Vargo and Lusch 2004 , 2016 ). While extant research provided the basis for a novel framework, existing concepts were decomposed into such fine-grained ingredients that the resulting integration was a new theoretical view in its own right rather than a summary of existing concepts.

Theory adaptation

Papers that focus on theory adaptation seek to amend an existing theory by using other theories. While empirical research may gradually extend some element of theory within a given context, theory-based adaptation attempts a more immediate shift of perspective. Theory adaptation papers develop contribution by revising extant knowledge—that is, by introducing alternative frames of reference to propose a novel perspective on an extant conceptualization (MacInnis 2011 ). The point of departure for such papers, then, is the problematization of a particular theory or concept. For example, the authors might argue that certain empirical developments or insights from other streams of literature render an existing conceptualization insufficient or conflicted, and that some reconfiguration or shift of perspective or scope is needed to better align the concept or theory to its purpose or to reconcile certain inconsistencies. Typically, the researcher draws from another theory that is equipped to guide this shift. The contribution of this type of a paper is often positioned to the domain where the focal concept is situated.

The starting point for the theory adaptation paper is the theory or concept of interest (domain theory). Other theories are used as tools, or method theories (Lukka and Vinnari 2014 ) to provide an alternative frame of reference to adjust or expand its conceptual scope. One “method” of adaptation is to switch the level of analysis; for example, Alexander et al. ( 2018 ) provided new insights into the influence of institutions on customer engagement by shifting from a micro level analysis of customer relationships—the prevailing view in the field—to meso and macro level views, adapting Chandler and Vargo’s ( 2011 ) process of oscillating foci. Another option is to use an established theory to explore new aspects of the domain theory (Yadav 2010 ). As one example of this type of design, Brodie et al. ( 2019 ) argued for the practical and theoretical importance of expanding the scope of engagement research in two ways: from a focus on consumers to a broad range of actors, and from dyadic firm-customer relationships to networks. As well as justifying why a particular extension or change of focus is needed, a theory adaptation paper must also show that the selected method theory is the best available option. For example, Brodie et al. ( 2019 ) explained that they employed service-dominant logic to broaden the conceptual scope of engagement research because it offered a lens for understanding actor-to-actor interactions in networks. Similarly, Hillebrand et al. ( 2015 ) used multiplicity theory to revise existing perspectives on stakeholder marketing by viewing stakeholder networks as continuous rather than discrete. They argued that this provides a more accurate understanding of markets characterized by complex value exchange and dispersed control.

A typology paper classifies conceptual variants as distinct types. The aim is to develop a categorization that “explains the fuzzy nature of many subjects by logically and causally combining different constructs into a coherent and explanatory set of types” (Cornelissen 2017 ). A typology paper provides a more precise and nuanced understanding of a phenomenon or concept, pinpointing and justifying key dimensions that distinguish the variants.

Typology papers contribute through differentiation— distinguishing, dimensionalizing, or categorizing extant knowledge of the phenomenon, construct, or theory in question (MacInnis 2011 ). Typologies reduce complexity (Fiss 2011 ). They demonstrate how variants of an entity differ, and hence organize complex networks of concepts and relationships, and may help by recognizing their differing antecedents, manifestations, or effects (MacInnis 2011 ). Typologies also offer a multidimensional view of the target phenomenon by categorizing theoretical features or dimensions as distinct profiles that offer coordinates for empirical research (Cornelissen 2017 ). For example, the classic typologies elaborated by Mills and Margulies ( 1980 ) and Lovelock ( 1983 ) assigned services to categories reflecting different aspects of the relationship between customers and the service organization, facilitating prediction of organizational behavior and marketing action. These theory-based typologies have informed numerous empirical applications.

The starting point for a typology paper is typically recognition of an important but fragmented research domain characterized by differing manifestations of a concept or inconsistent findings regarding drivers or outcomes. The researcher accumulates knowledge of the focal topic and then organizes it to capture the variability of particular characteristics of the concept or phenomenon. For example, after exploring different approaches to service innovation, Helkkula et al. ( 2018 ) proposed a typology of four archetypes. They suggested that variance within the extant research could be explained by differences of theoretical perspective and argued that each type had distinct implications for value creation.

The dimensions of a typology can also be differentiated by applying another theory (i.e. methods theory) that provides a logical explanation of why differences exist and why they are relevant. For example, to examine the boundaries of resource integration, Dong and Sivakumar ( 2017 ) developed a typology of customer participation, using dimensions drawn from resource-based theory, to address the fundamental resource deployment questions of whether there is a choice in terms of who performs a task and what task is performed (Kozlenkova et al. 2014 ).

Snow and Ketchen Jr. ( 2014 ) argued that well-developed typologies are more than just classification systems; rather, a typology articulates relationships among constructs and facilitates testable predictions (cf. Doty and Glick 1994 ). In this way, a typology can propose multiple causal relationships in a given setting (Fiss 2011 ). While a typology paper enhances understanding of a phenomenon by delineating its key variants, it can be seen to differ from a synthesis or adaptation paper by virtue of its explanatory character. This is the typology’s raison d’etre; types always explain something, and the dimensions that distinguish types account for the different drivers, outcomes, or contingencies of particular variants of the phenomenon. By accommodating asymmetric causal relations, typologies facilitate the development of configurational arguments beyond simple correlations (Fiss 2011 ).

The model paper seeks to build a theoretical framework that predicts relationships between concepts. A conceptual model describes an entity and identifies issues that should be considered in its study: it can describe an event, an object, or a process, and explain how it works by disclosing antecedents, outcomes, and contingencies related to the focal construct (Meredith 1993 ; MacInnis 2011 ). This typically involves a form of theorizing that seeks to create a nomological network around the focal concept, employing a formal analytical approach to examine and detail the causal linkages and mechanisms at play (Delbridge and Fiss 2013 ). A model paper identifies previously unexplored connections between constructs, introduces new constructs, or explains why elements of a process lead to a particular outcome (Cornelissen 2017 ; Fulmer 2012 ).

The model paper contributes to extant knowledge by delineating an entity: its goal is “to detail, chart, describe, or depict an entity and its relationship to other entities” (MacInnis 2011 ). In a conceptual article, creative scope is unfettered by data-related limitations, allowing the researcher to explore and model emerging phenomena where few empirical data are available (Yadav 2010 ). The model paper typically contributes by providing a roadmap for understanding the entity in question by delineating the focal concept, how it changes, the processes by which it operates, or the moderating conditions that may affect it (MacInnis 2011 ).

A model paper typically begins from a focal phenomenon or construct that warrants further explanation. For example, Huang and Rust ( 2018 ) sought to explain the process and mechanism by which artificial intelligence (AI) will replace humans in service jobs. They employed literature that tackles key variables associated with the target phenomenon: service research illuminates the focal phenomenon, technology-enabled services, and research across multiple disciplines discusses the likely impact of AI on human labor. By synthesizing this literature pool, they identified four types of intelligence and then built a theory that could predict the impact of AI on human service labor. This involved a particular kind of formal reasoning, supported by research from multiple disciplines and real-world applications (Huang and Rust 2018 ). In other words, the authors use method theories and deductive reasoning to explain relationships between key variables, facilitated by theories in use (MacInnis 2011 ).

Model papers typically summarize arguments in the form of a figure that depicts the salient constructs and their relationships, or as a set of formal propositions that are logical statements derived from the conceptual framework (Meredith 1993 ). For example, Payne et al. ( 2017 ) used resource-based theory to develop a conceptual model of the antecedents and outcomes of customer value propositions. While figures and propositions of this kind help the reader by condensing the paper’s main message, Delbridge and Fiss ( 2013 ) noted that they are also a double-edged sword. At their best, propositions distill the essence of an argument into a parsimonious and precise form, but by virtue of this very ability, they also put a spotlight on the weaknesses in the argument chain. According to Cornelissen ( 2017 ), the researcher should therefore be clear about the “causal agent” in any proposed relationship between constructs when developing propositions—in other words, the trigger or force that drives a particular outcome or effect. Careful consideration and justification of the choice of theories and the manner in which they are integrated to produce the arguments is hence pivotal in sharpening and clarifying the argumentation to convince reviewers and readers.

Conclusions

This paper highlights the role of methodological considerations in conceptual papers by discussing alternative types of research design, in the hope of encouraging researchers to critically assess and develop conceptual papers accordingly. Authors of conceptual papers should readily answer the following questions: What is the logic of creating new knowledge? Why are particular information sources selected, and how are they analyzed? What role does each theory play? For reviewers, assessing conceptual papers can be difficult not least because the generally accepted and readily available guidelines for evaluating empirical research seldom apply directly to non-empirical work. By asking these questions, reviewers and supervisors can evaluate whether the research design of a paper or thesis is carefully crafted and clearly communicated to the reader.

The paper identifies four types of conceptual papers—Theory Synthesis, Theory Adaptation, Typology, and Model—and discusses their aims, methods of theory use, and potential contributions. Although this list is not exhaustive, these types offer basic templates for designing conceptual research and determining its intended contribution (cf. MacInnis 2011 ). Careful consideration of these alternative types can facilitate more conscious selection of approach and structure for a conceptual paper. Researchers can also consider opportunities for combining types. In many cases, mixing two types can be an attractive option. For example, after distinguishing types of service innovation in terms of their conceptual underpinnings, Helkkula et al. ( 2018 ) synthesized a novel conceptualization of service innovation that exploited the strengths of each type and mitigated their limitations. Typologies can also provide the basis for models, and synthesis can lead to theory adaptation.

This paper highlights the many alternative routes along which conceptual papers can advance extant knowledge. We should consider conceptual papers not just as a means to take stock, but to break new ground. Empirical research takes time to accumulate, and the scope for generalization is relatively narrow. In contrast, conceptual papers can strive to advance understanding of a concept or phenomenon in big leaps rather than incremental steps. To be taken seriously, any such leap must be grounded in thorough consideration and justification of an appropriate research design.

A discussion of how different theoretical lenses can be integrated is beyond the scope of this paper, but see for example Okhuysen and Bonardi ( 2011 ) and Gioia and Pitre ( 1990 ).

Alexander, M. J., Jaakkola, E., & Hollebeek, L. D. (2018). Zooming out: Actor engagement beyond the dyadic. Journal of Service Management, 29 (3), 333–351.

Article Google Scholar

Alvesson, M., & Sandberg, J. (2011). Generating research questions through problematization. Academy of Management Review, 36 (2), 247–271.

Google Scholar

Becker, L., & Jaakkola, E. (2020). Customer experience: Fundamental premises and implications for research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-019-00718-x .

Brodie, R. J., Fehrer, J. A., Jaakkola, E., & Conduit, J. (2019). Actor engagement in networks: Defining the conceptual domain. Journal of Service Research, 22 (2), 173–188.

Chandler, J. D., & Vargo, S. L. (2011). Contextualization and value-in-context: How context frames exchange. Marketing Theory, 11 (1), 35–49.

Corley, K. G., & Gioia, D. A. (2011). Building theory about theory building: What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review, 36 (1), 12–32.

Cornelissen, J. (2017). Editor’s comments: Developing propositions, a process model, or a typology? Addressing the challenges of writing theory without a boilerplate. Academy of Management Review, 42 (1), 1–9.

Cropanzano, R. (2009). Writing nonempirical articles for Journal of Management: General thoughts and suggestions. Journal of Management, 35 (6), 1304–1311.

De Brentani, U., & Reid, S. E. (2012). The fuzzy front-end of discontinuous innovation: Insights for research and management. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 29 (1), 70–87.

Delbridge, R., & Fiss, P. C. (2013). Editors’ comments: Styles of theorizing and the social organization of knowledge. Academy of Management Review, 38 (3), 325–331.

Dong, B., & Sivakumar, K. (2017). Customer participation in services: Domain, scope, and boundaries. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45 (6), 944–965.

Doty, D. H., & Glick, W. H. (1994). Typologies as a unique form of theory building: Toward improved understanding and modeling. Academy of Management Review, 19 (2), 230–251.

Eckhardt, G. M., Houston, M. B., Jiang, B., Lamberton, C., Rindfleisch, A., & Zervas, G. (2019). Marketing in the sharing economy. Journal of Marketing, 83 (5), 5–27.

Edvardsson, B., Kristensson, P., Magnusson, P., & Sundström, E. (2012). Customer integration within service development—A review of methods and an analysis of insitu and exsitu contributions. Technovation, 32 (7–8), 419–429.

Fiss, P. C. (2011). Building better causal theories: A fuzzy set approach to typologies in organizational research. Academy of Management Journal, 54 , 393–420.

Flick, U. (2018). An introduction to qualitative research . London: Sage Publications.

Fulmer, I. S. (2012). Editor's comments: The craft of writing theory articles—Variety and similarity in AMR. Academy of Management Review, 37 , 327–331.

Gilson, L. L., & Goldberg, C. B. (2015). Editors’ comment: So, what is a conceptual paper? Group & Organization Management, 40 (2), 127–130.

Gioia, D., & Pitre, E. (1990). Multiparadigm perspectives on theory building. Academy of Management Review, 15 (4), 584–602.

Hartmann, N. N., Wieland, H., & Vargo, S. L. (2018). Converging on a new theoretical foundation for selling. Journal of Marketing, 82 (2), 1–18.

Helkkula, A., Kowalkowski, C., & Tronvoll, B. (2018). Archetypes of service innovation: Implications for value cocreation. Journal of Service Research, 21 (3), 284–301.

Hillebrand, B., Driessen, P. H., & Koll, O. (2015). Stakeholder marketing: Theoretical foundations and required capabilities. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43 (4), 411–428.

Hirschheim, R. (2008). Some guidelines for the critical reviewing of conceptual papers. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 9 (8), 432–441.

Huang, M. H., & Rust, R. T. (2018). Artificial intelligence in service. Journal of Service Research, 21 (2), 155–172.

King, A. W., & Lepak, D. (2011). Editors’ comments: Myth busting—What we hear and what we’ve learned about AMR. Academy of Management Review, 36 (2), 207–214.

Kozlenkova, I. V., Samaha, S. A., & Palmatier, R. W. (2014). Resource-based theory in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 42 (1), 1–21.

Lemon, K. N., & Verhoef, P. C. (2016). Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. Journal of Marketing, 80 , 69–96.

Lovelock, C. H. (1983). Classifying services to gain strategic marketing insights. Journal of Marketing, 47 (3), 9–20.

Lukka, K., & Vinnari, E. (2014). Domain theory and method theory in management accounting research. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 27 (8), 1308–1338.

MacInnis, D. J. (2011). A framework for conceptual contributions in marketing. Journal of Marketing, 75 (4), 136–154.

MacInnis, D. J., & De Mello, G. E. (2005). The concept of hope and its relevance to product evaluation and choice. Journal of Marketing, 69 (1), 1–14.

Meredith, J. (1993). Theory building through conceptual methods. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 13 (5), 3–11.

Miller, D. C., & Salkind, N. J. (2002). Elements of research design. In Handbook of research design & social measurement, ed. by Miller D.C. & Salkind, J.J. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

Mills, P. K., & Margulies, N. (1980). Toward a core typology of service organizations. Academy of Management Review, 5 (2), 255–266.

Möller, K. (2013). Theory map of business marketing: Relationships and networks perspectives. Industrial Marketing Management, 42 (3), 324–335.

Okhuysen, G., & Bonardi, J. (2011). The challenges of building theory by combining lenses. Academy of Management Review, 36 (1), 6–11.

Palmatier, R. W., Houston, M. B., & Hulland, J. (2018). Review articles: Purpose, process, and structure. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46 (1), 1–5.

Payne, A., Frow, P., & Eggert, A. (2017). The customer value proposition: Evolution, development, and application in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45 (4), 467–489.

Ragin, C. C. (1994). Constructing social research . Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press.

Shepherd, D. A., & Suddaby, R. (2017). Theory building: A review and integration. Journal of Management, 43 (1), 59–86.

Snow, C. C., & Ketchen Jr., D. J. (2014). Typology-driven theorizing: A response to Delbridge and Fiss. Academy of Management Review, 39 (2), 231–233.

Toulmin, S. (1958). The uses of argument . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68 , 1–17.

Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2016). Institutions and axioms: An extension and update of service-dominant logic. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44 (1), 5–23.

Webster, J., & Watson, R. T. (2002). Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: Writing a literature review. MIS Quarterly , xiii–xxiii.

White, K., Habib, R., & Hardisty, D. J. (2019). How to SHIFT consumer behaviors to be more sustainable: A literature review and guiding framework. Journal of Marketing, 83 (3), 22–49.

Yadav, M. S. (2010). The decline of conceptual articles and implications for knowledge development. Journal of Marketing, 74 (1), 1–19.

Download references

Open access funding provided by University of Turku (UTU) including Turku University Central Hospital.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Turku School of Economics, University of Turku, FIN-20014, Turku, Finland

Elina Jaakkola

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Elina Jaakkola .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Jaakkola, E. Designing conceptual articles: four approaches. AMS Rev 10 , 18–26 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13162-020-00161-0

Download citation

Received : 12 November 2019

Accepted : 04 February 2020

Published : 09 March 2020

Issue Date : June 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13162-020-00161-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Conceptual research

- Theoretical article

- Methodology

- Research design

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples

What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples

Published on August 2, 2022 by Bas Swaen and Tegan George. Revised on March 18, 2024.

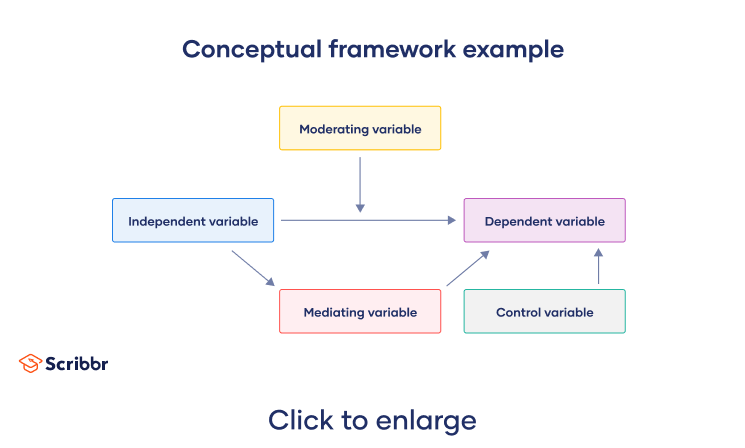

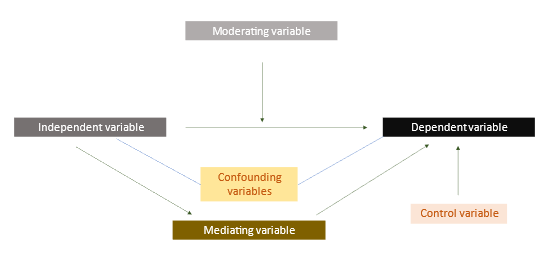

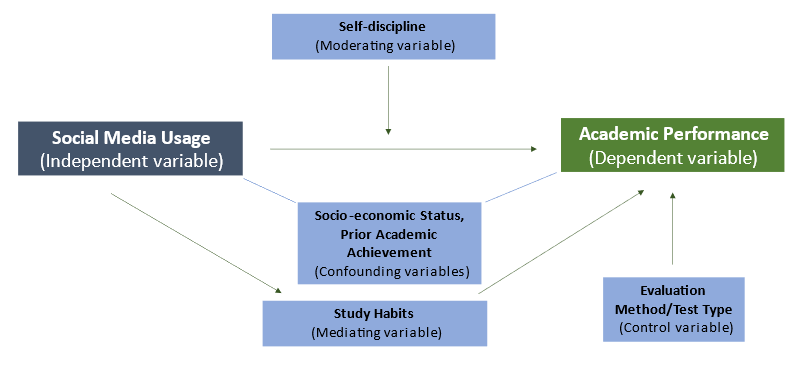

A conceptual framework illustrates the expected relationship between your variables. It defines the relevant objectives for your research process and maps out how they come together to draw coherent conclusions.

Keep reading for a step-by-step guide to help you construct your own conceptual framework.

Table of contents

Developing a conceptual framework in research, step 1: choose your research question, step 2: select your independent and dependent variables, step 3: visualize your cause-and-effect relationship, step 4: identify other influencing variables, frequently asked questions about conceptual models.

A conceptual framework is a representation of the relationship you expect to see between your variables, or the characteristics or properties that you want to study.

Conceptual frameworks can be written or visual and are generally developed based on a literature review of existing studies about your topic.

Your research question guides your work by determining exactly what you want to find out, giving your research process a clear focus.

However, before you start collecting your data, consider constructing a conceptual framework. This will help you map out which variables you will measure and how you expect them to relate to one another.

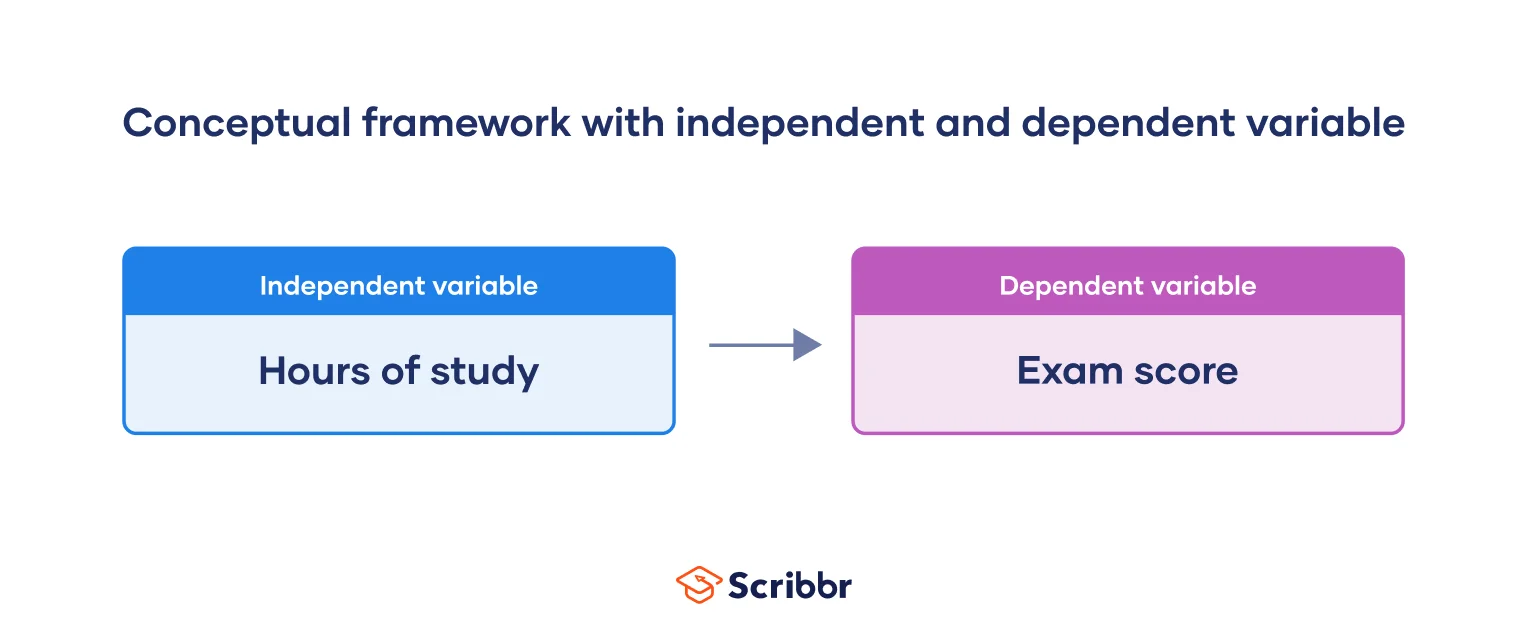

In order to move forward with your research question and test a cause-and-effect relationship, you must first identify at least two key variables: your independent and dependent variables .

- The expected cause, “hours of study,” is the independent variable (the predictor, or explanatory variable)

- The expected effect, “exam score,” is the dependent variable (the response, or outcome variable).

Note that causal relationships often involve several independent variables that affect the dependent variable. For the purpose of this example, we’ll work with just one independent variable (“hours of study”).

Now that you’ve figured out your research question and variables, the first step in designing your conceptual framework is visualizing your expected cause-and-effect relationship.

We demonstrate this using basic design components of boxes and arrows. Here, each variable appears in a box. To indicate a causal relationship, each arrow should start from the independent variable (the cause) and point to the dependent variable (the effect).

It’s crucial to identify other variables that can influence the relationship between your independent and dependent variables early in your research process.

Some common variables to include are moderating, mediating, and control variables.

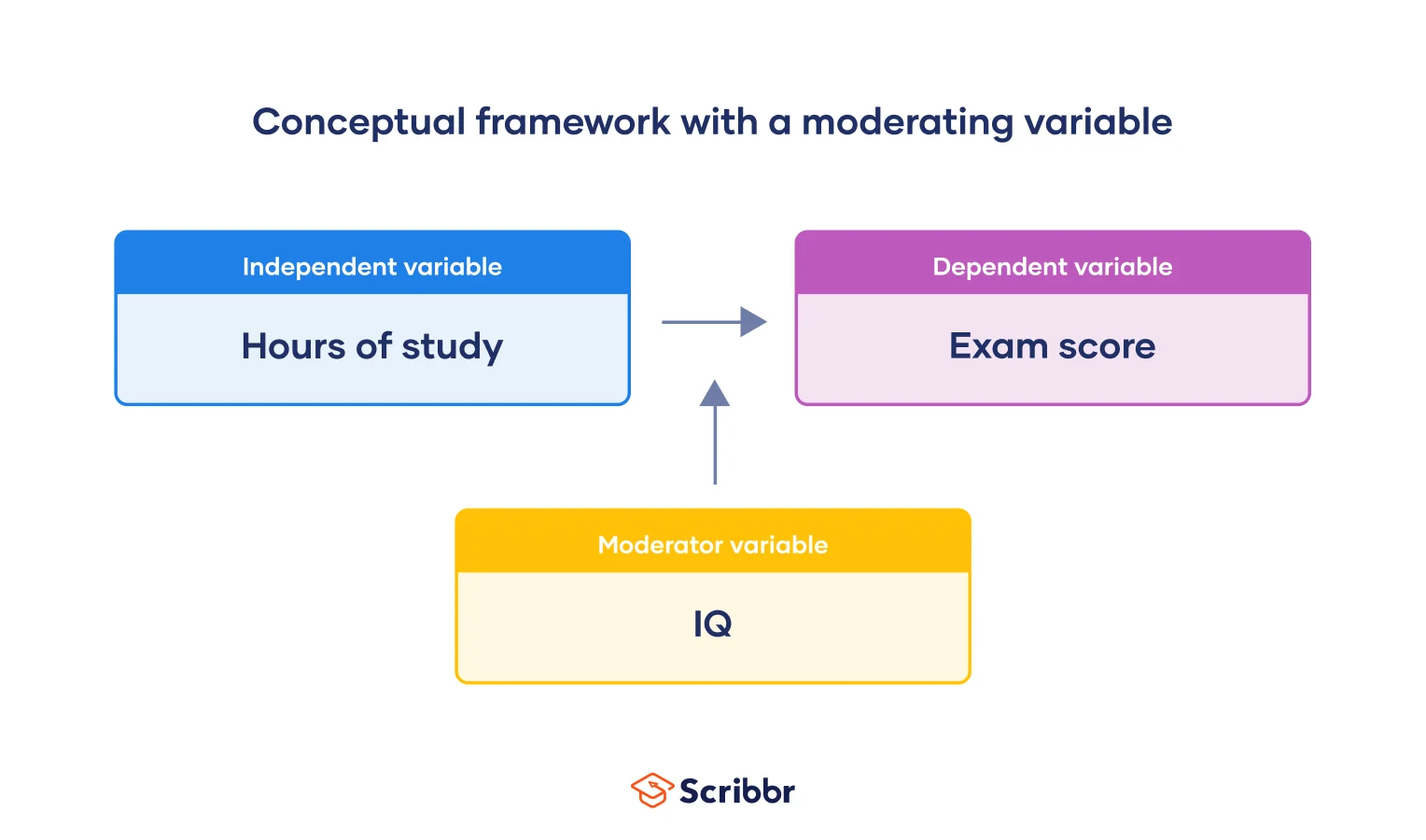

Moderating variables

Moderating variable (or moderators) alter the effect that an independent variable has on a dependent variable. In other words, moderators change the “effect” component of the cause-and-effect relationship.

Let’s add the moderator “IQ.” Here, a student’s IQ level can change the effect that the variable “hours of study” has on the exam score. The higher the IQ, the fewer hours of study are needed to do well on the exam.

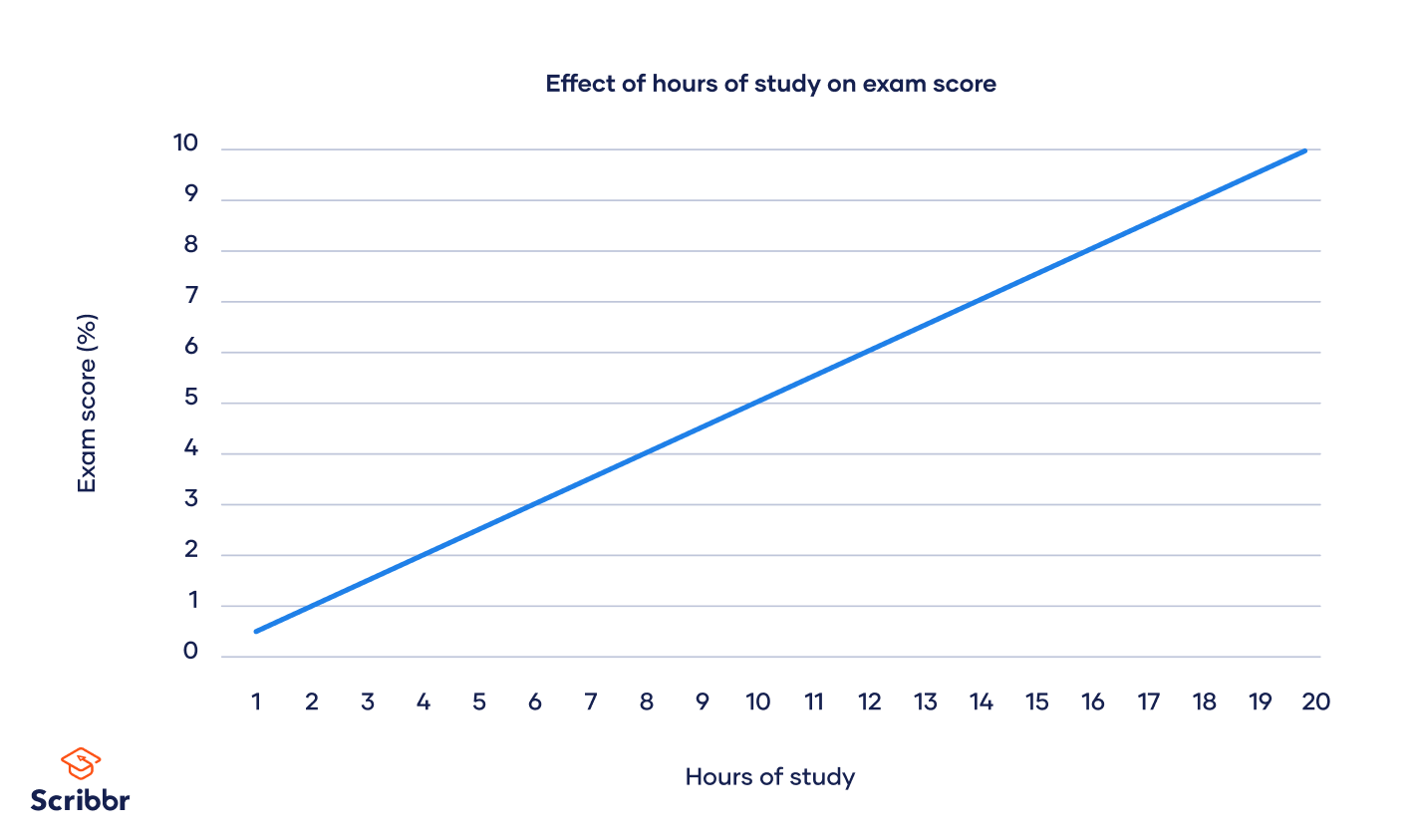

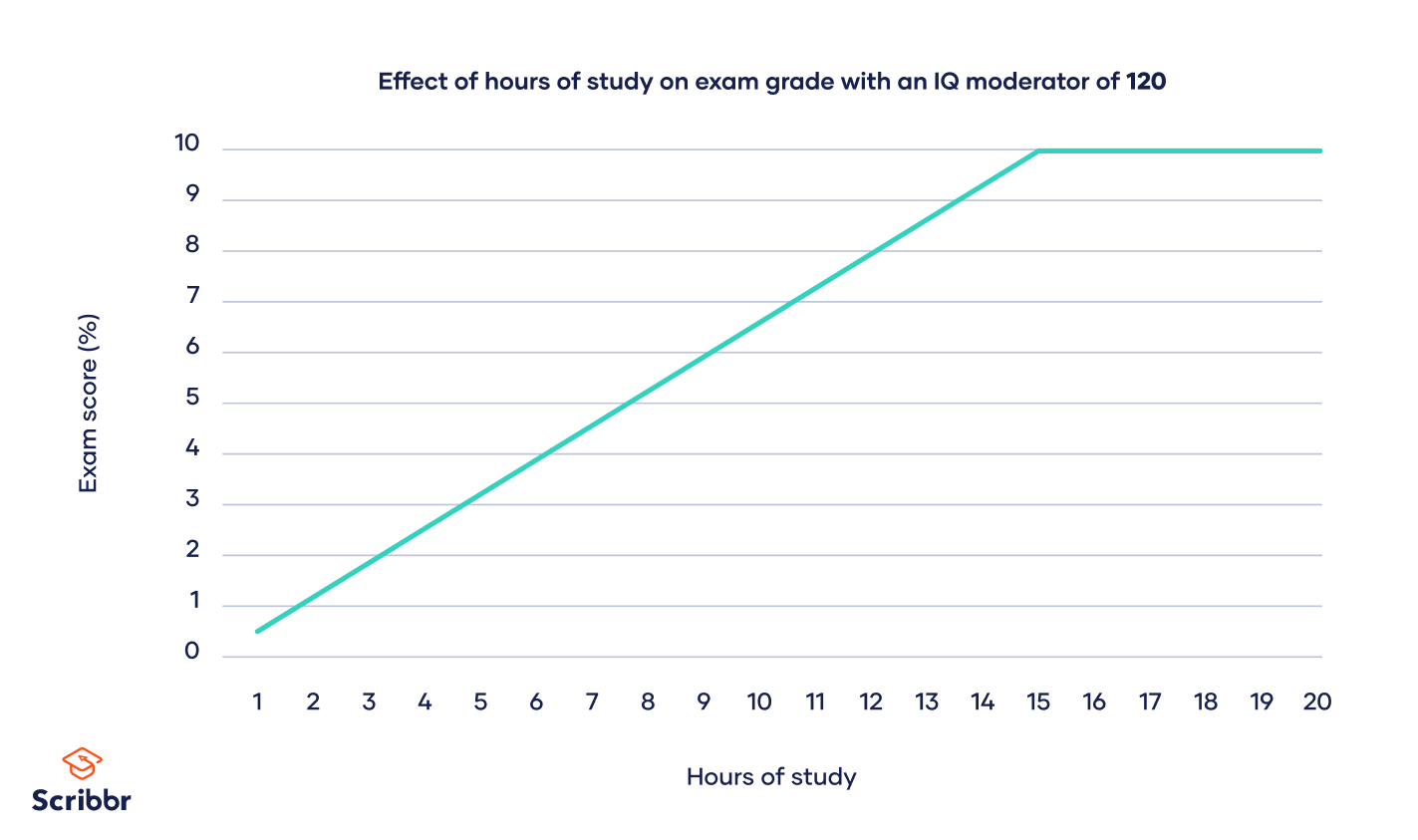

Let’s take a look at how this might work. The graph below shows how the number of hours spent studying affects exam score. As expected, the more hours you study, the better your results. Here, a student who studies for 20 hours will get a perfect score.

But the graph looks different when we add our “IQ” moderator of 120. A student with this IQ will achieve a perfect score after just 15 hours of study.

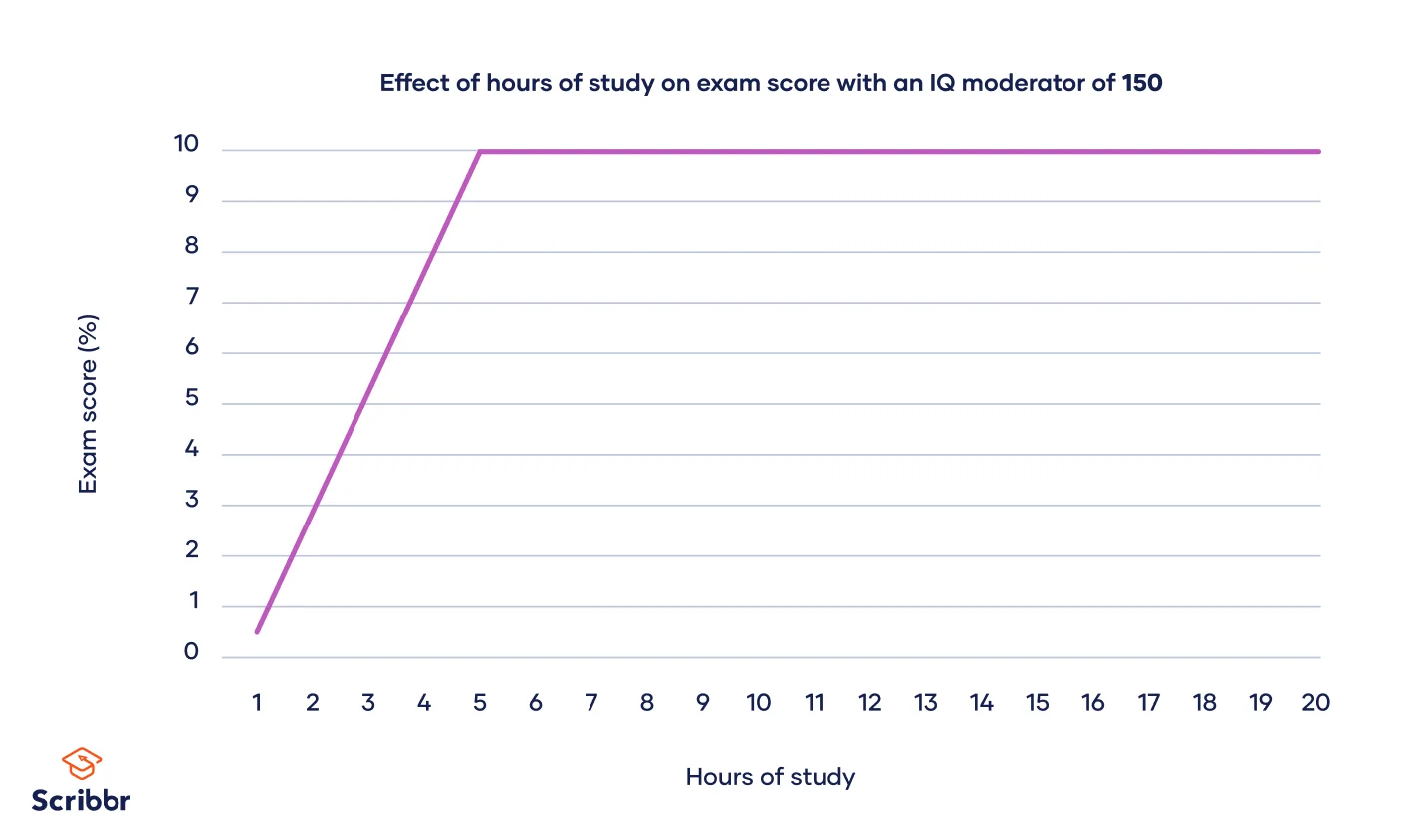

Below, the value of the “IQ” moderator has been increased to 150. A student with this IQ will only need to invest five hours of study in order to get a perfect score.

Here, we see that a moderating variable does indeed change the cause-and-effect relationship between two variables.

Mediating variables

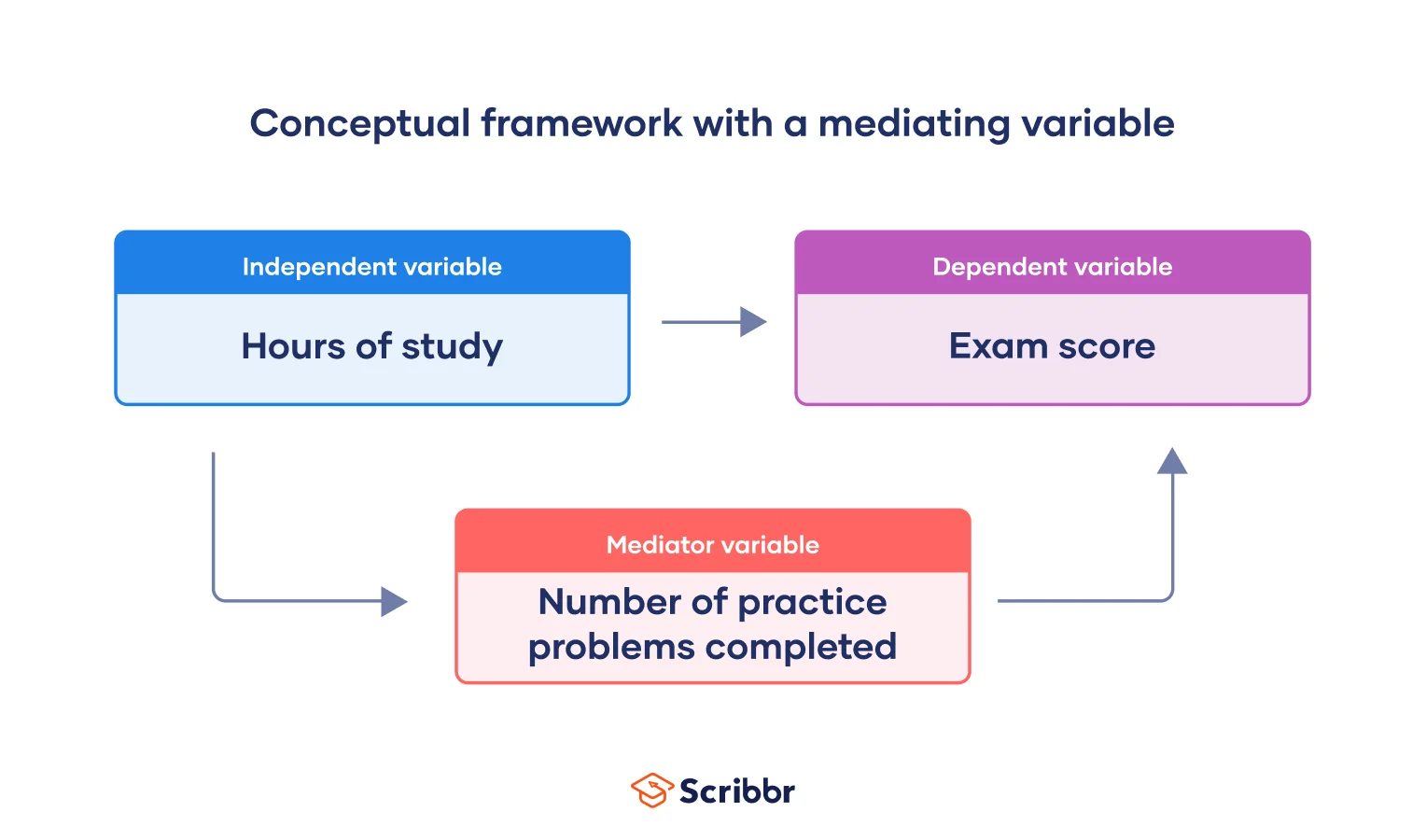

Now we’ll expand the framework by adding a mediating variable . Mediating variables link the independent and dependent variables, allowing the relationship between them to be better explained.

Here’s how the conceptual framework might look if a mediator variable were involved:

In this case, the mediator helps explain why studying more hours leads to a higher exam score. The more hours a student studies, the more practice problems they will complete; the more practice problems completed, the higher the student’s exam score will be.

Moderator vs. mediator

It’s important not to confuse moderating and mediating variables. To remember the difference, you can think of them in relation to the independent variable:

- A moderating variable is not affected by the independent variable, even though it affects the dependent variable. For example, no matter how many hours you study (the independent variable), your IQ will not get higher.

- A mediating variable is affected by the independent variable. In turn, it also affects the dependent variable. Therefore, it links the two variables and helps explain the relationship between them.

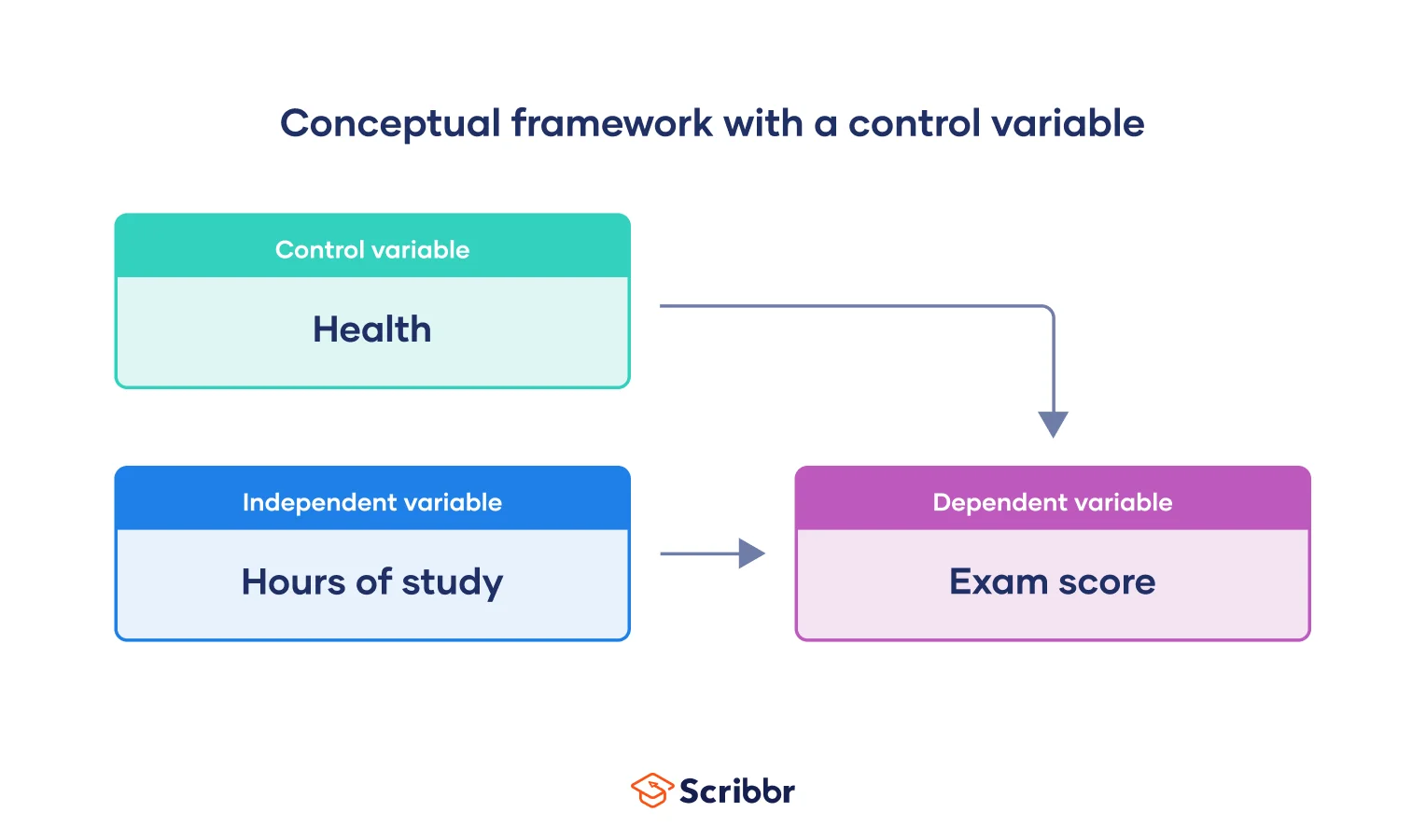

Control variables

Lastly, control variables must also be taken into account. These are variables that are held constant so that they don’t interfere with the results. Even though you aren’t interested in measuring them for your study, it’s crucial to be aware of as many of them as you can be.

A mediator variable explains the process through which two variables are related, while a moderator variable affects the strength and direction of that relationship.

A confounding variable is closely related to both the independent and dependent variables in a study. An independent variable represents the supposed cause , while the dependent variable is the supposed effect . A confounding variable is a third variable that influences both the independent and dependent variables.

Failing to account for confounding variables can cause you to wrongly estimate the relationship between your independent and dependent variables.

Yes, but including more than one of either type requires multiple research questions .

For example, if you are interested in the effect of a diet on health, you can use multiple measures of health: blood sugar, blood pressure, weight, pulse, and many more. Each of these is its own dependent variable with its own research question.

You could also choose to look at the effect of exercise levels as well as diet, or even the additional effect of the two combined. Each of these is a separate independent variable .

To ensure the internal validity of an experiment , you should only change one independent variable at a time.

A control variable is any variable that’s held constant in a research study. It’s not a variable of interest in the study, but it’s controlled because it could influence the outcomes.

A confounding variable , also called a confounder or confounding factor, is a third variable in a study examining a potential cause-and-effect relationship.

A confounding variable is related to both the supposed cause and the supposed effect of the study. It can be difficult to separate the true effect of the independent variable from the effect of the confounding variable.

In your research design , it’s important to identify potential confounding variables and plan how you will reduce their impact.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Swaen, B. & George, T. (2024, March 18). What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 21, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/conceptual-framework/

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked

Independent vs. dependent variables | definition & examples, mediator vs. moderator variables | differences & examples, control variables | what are they & why do they matter, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Conceptual models for health education and practice

- Health Education Research 6(2):163-71

- 6(2):163-71

- University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Sex Res Soc Pol

- SWISS MED WKLY

- Stefan Mitterer

- Günther Fink

- Eva Bergstraesser

- Gustavo Cabrera A

- Jorge Tascón G

- Diego Lucumí C

- Kazuhiko Mori

- Shigeo Nakano

- Health Psychol Rev

- Haimanot Hailu

- R. Kathryn McHugh

- Harsha Vijayakumar

- Deborah E. Dickerson

- PSYCHOTHERAPY

- Health Educ Q

- Allan Steckler

- John Cassel

- J Health Hum Behav

- Edward A. Suchman

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What is a Conceptual Framework and How to Make It (with Examples)

A strong conceptual framework underpins good research. A conceptual framework in research is used to understand a research problem and guide the development and analysis of the research. It serves as a roadmap to conceptualize and structure the work by providing an outline that connects different ideas, concepts, and theories within the field of study. A conceptual framework pictorially or verbally depicts presumed relationships among the study variables.

The purpose of a conceptual framework is to serve as a scheme for organizing and categorizing knowledge and thereby help researchers in developing theories and hypotheses and conducting empirical studies.

In this post, we explain what is a conceptual framework, and provide expert advice on how to make a conceptual framework, along with conceptual framework examples.

Table of Contents

What is a Conceptual Framework in Research

Definition of a conceptual framework.

A conceptual framework includes key concepts, variables, relationships, and assumptions that guide the academic inquiry. It establishes the theoretical underpinnings and provides a lens through which researchers can analyze and interpret data. A conceptual framework draws upon existing theories, models, or established bodies of knowledge to provide a structure for understanding the research problem. It defines the scope of research, identifying relevant variables, establishing research questions, and guiding the selection of appropriate methodologies and data analysis techniques.

Conceptual frameworks can be written or visual. Other types of conceptual framework representations might be taxonomic (verbal description categorizing phenomena into classes without showing relationships between classes) or mathematical descriptions (expression of phenomena in the form of mathematical equations).

Figure 1: Definition of a conceptual framework explained diagrammatically

Conceptual Framework Origin

The term conceptual framework appears to have originated in philosophy and systems theory, being used for the first time in the 1930s by the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead. He bridged the theological, social, and physical sciences by providing a common conceptual framework. The use of the conceptual framework began early in accountancy and can be traced back to publications by William A. Paton and John B. Canning in the first quarter of the 20 th century. Thus, in the original framework, financial issues were addressed, such as useful features, basic elements, and variables needed to prepare financial statements. Nevertheless, a conceptual framework approach should be considered when starting your research journey in any field, from finance to social sciences to applied sciences.

Purpose and Importance of a Conceptual Framework in Research

The importance of a conceptual framework in research cannot be understated, irrespective of the field of study. It is important for the following reasons:

- It clarifies the context of the study.

- It justifies the study to the reader.

- It helps you check your own understanding of the problem and the need for the study.

- It illustrates the expected relationship between the variables and defines the objectives for the research.

- It helps further refine the study objectives and choose the methods appropriate to meet them.

What to Include in a Conceptual Framework

Essential elements that a conceptual framework should include are as follows:

- Overarching research question(s)

- Study parameters

- Study variables

- Potential relationships between those variables.

The sources for these elements of a conceptual framework are literature, theory, and experience or prior knowledge.

How to Make a Conceptual Framework

Now that you know the essential elements, your next question will be how to make a conceptual framework.

For this, start by identifying the most suitable set of questions that your research aims to answer. Next, categorize the various variables. Finally, perform a rigorous analysis of the collected data and compile the final results to establish connections between the variables.

In short, the steps are as follows:

- Choose appropriate research questions.

- Define the different types of variables involved.

- Determine the cause-and-effect relationships.

Be sure to make use of arrows and lines to depict the presence or absence of correlational linkages among the variables.

Developing a Conceptual Framework

Researchers should be adept at developing a conceptual framework. Here are the steps for developing a conceptual framework:

1. Identify a research question

Your research question guides your entire study, making it imperative to invest time and effort in formulating a question that aligns with your research goals and contributes to the existing body of knowledge. This step involves the following:

- Choose a broad topic of interest

- Conduct background research

- Narrow down the focus

- Define your goals

- Make it specific and answerable

- Consider significance and novelty

- Seek feedback.

2. Choose independent and dependent variables