- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

green revolution

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Humanities LibreTexts - Green Revolution

- National Library of Medicine - Green Revolution: Impacts, limits, and the path ahead

- DigitalCommons at University of Nebraska - Lincoln - The Green Revolution of the 1960's and Its Impact on Small Farmers in IndiaFarmers in India

- Frontiers - Lessons From the Aftermaths of Green Revolution on Food System and Health

- Minnesota Libraries Publishing Project - Green Revolution

- Academia - Green Revolution

- UC Berkeley’s College of Natural Resources - Lessons from the Green Revolution

- PBS - American Experience - The Green Revolution: Norman Borlaug and the Race to Fight Global Hunger

- Green Revolution - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- Green Revolution - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

Recent News

green revolution , great increase in production of food grains (especially wheat and rice ) that resulted in large part from the introduction into developing countries of new, high-yielding varieties, beginning in the mid-20th century. Its early dramatic successes were in Mexico and the Indian subcontinent . The new varieties require large amounts of chemical fertilizers and pesticides to produce their high yields , raising concerns about cost and potentially harmful environmental effects. Poor farmers, unable to afford the fertilizers and pesticides, have often reaped even lower yields with these grains than with the older strains, which were better adapted to local conditions and had some resistance to pests and diseases. See also Norman Borlaug .

- New Visions Social Studies Curriculum

- Curriculum Development Team

- Content Contributors

- Getting Started: Baseline Assessments

- Getting Started: Resources to Enhance Instruction

- Getting Started: Instructional Routines

- Unit 9.1: Global 1 Introduction

- Unit 9.2: The First Civilizations

- Unit 9.3: Classical Civilizations

- Unit 9.4: Political Powers and Achievements

- Unit 9.5: Social and Cultural Growth and Conflict

- Unit 9.6: Ottoman and Ming Pre-1600

- Unit 9.7: Transformations in Europe

- Unit 9.8: Africa and the Americas Pre-1600

- Unit 9.9: Interactions and Disruptions

- 10.0: Global 2 Introduction

- 10.01: The World in 1750 C.E.

- 10.02: Enlightenment, Revolution, & Nationalism

- 10.03: Industrial Revolution

- 10.04: Imperialism & Colonization

- 10.05: World Wars

- 10.06: Cold War

- 10.07: Decolonization & Nationalism

- 10.08: Cultural Traditions & Modernization

- 10.09: Globalization & Changing Environment

- 10.10: Human Rights Violations

- Unit 11.0: US History Introduction

- Unit 11.1: Colonial Foundations

- Unit 11.2: American Revolution

- Unit 11.3A: Building a Nation

- Unit 11.03B: Sectionalism & Civil War

- Unit 11.4: Reconstruction

- Unit 11.5: Gilded Age and Progressive Era

- Unit 11.6: Rise of American Power

- Unit 11.7: Prosperity and Depression

- Unit 11.8: World War II

- Unit 11.9: Cold War

- Unit 11.10: Domestic Change

- Resources: Regents Prep: Global 2 Exam

- Regents Prep: Framework USH Exam: Regents Prep: US Exam

- Find Resources

Global History II

10.09: Globalization & Changing Environment

Causes and Effects of Population Growth and Globalization: SQ 7. What was the Green Revolution? What effect has it had? What lessons can we learn from it to address global needs in the 21st century?

Describe what the Green Revolution was. Explain the effects of the Green Revolution. Identify lessons learned from the Green Revolution that can help address 21st century issues.

CONCEPTUAL UNDERSTANDING: Population pressures, industrialization, and urbanization have increased demands for limited natural resources and food resources, often straining the environment.

CONTENT SPECIFICATION: Students will examine how the world’s population is growing exponentially for numerous reasons and how it is not evenly distributed.

CONTENT SPECIFICATION: Students will explore efforts to increase and intensify food production through industrial agriculture (e.g., Green Revolutions, use of fertilizers and pesticides, irrigation, and genetic modifications).

CONTENT SPECIFICATION: Students will examine strains on the environment, such as threats to wildlife and degradation of the physical environment (i.e., desertification, deforestation and pollution) due to population growth, industrialization, and urbanization.

Teacher Feedback

Please comment below with questions, feedback, suggestions, or descriptions of your experience using this resource with students.

If you found an error in the resource, please let us know so we can correct it by filling out this form .

Globalization & Changing Environment

Advertisement

From Green Revolution to Green Evolution: A Critique of the Political Myth of Averted Famine

- Published: 26 March 2019

- Volume 57 , pages 265–291, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

- Roger Pielke Jr. ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9617-8764 1 &

- Björn-Ola Linnér 2

2409 Accesses

10 Citations

56 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This paper critiques the so-called “Green Revolution” as a political myth of averted famine. A “political myth,” among other functions, reflects a narrative structure that characterizes understandings of causality between policy action and outcome. As such, the details of a particular political myth elevate certain policy options (and families of policy options) over others. One important narrative strand of the political myths of the Green Revolution is a story of averted famine: in the 1950s and 1960s, scientists predicted a global crisis to emerge in the 1970s and beyond, created by a rapidly growing global population that would cause global famine as food supplies would not keep up with demand. The narrative posits that an intense period of technological innovation in agricultural productivity led to increasing crop yields which led to more food being produced, and the predicted crisis thus being averted. The fact that the world did not experience a global famine in the 1970s is cited as evidence in support of the narrative. Political myths need not necessarily be supported by evidence, but to the extent that they shape understandings of cause and effect in policymaking, political myths which are not grounded in evidence risk misleading policymakers and the public. We argue a political myth of the Green Revolution focused on averted famine is not well grounded in evidence and thus has potential to mislead to the extent it guides thinking and action related to technological innovation. We recommend an alternative narrative: The Green Evolution, in which sustainable improvements in agricultural productivity did not necessarily avert a global famine, but nonetheless profoundly shaped the modern world. More broadly, we argue that one of the key functions of the practice of technology assessment is to critique and to help create the political myths that preserve an evidence-grounded basis for connecting the cause and effect of policy action and practical outcomes.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

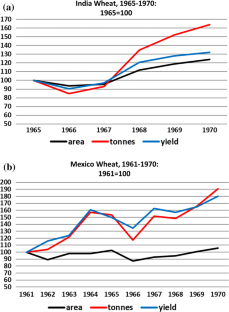

Source : FAOSTAT

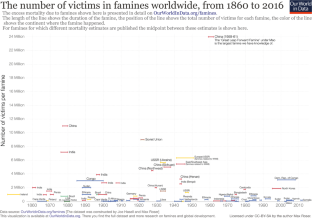

Source : Hasell and Roser ( 2017 ), figure used with permission

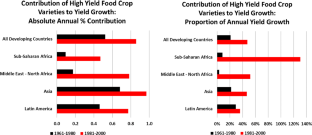

Data from Evenson and Gollin ( 2003 ). (Color figure online)

Similar content being viewed by others

A green theory of technological change: Ecologism and the case for technological scepticism

The green economy transition: the challenges of technological change for sustainability.

Games for Change

Explore related subjects.

- Medical Ethics

See for example: https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=second+green+revolution%2C+new+green+revolution&year_start=1960&year_end=2008&corpus=15&smoothing=5&share=&direct_url=t1%3B%2Csecond%20green%20revolution%3B%2Cc0%3B.t1%3B%2Cnew%20green%20revolution%3B%2Cc0 .

www.google.com , search terms “new Green Revolution” and “second Green Revolution”, 13 March 2019.

http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/patna/Modi-presses-for-second-green-revolution-in-Bihar/articleshow/7612745.cms .

http://www.wsj.com/articles/growing-a-second-green-revolution-1416613158 .

http://www.thehindu.com/business/budget/aim-a-second-green-revolution/article6198871.ece .

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/men/thinking-man/11216988/Population-growth-is-clearly-our-planets-number-one-problem.html .

www.google.com , search terms “Green Revolution in Mexico” and “Green Revolution in India,” 2016.08.29.

https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C6&q=%22green+revolution%22&btnG=(2018.12.15) .

http://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21601815-another-green-revolution-stirring-worlds-paddy-fields-bigger-rice-bowl .

For comparison, FAO estimated that about 10% of the world’s population was malnourished in 2017: http://www.fao.org/3/I9553EN/i9553en.pdf#page=22 .

Mexico wheat data: http://repository.cimmyt.org/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10883/1215/62178.pdf .

http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/1970/borlaug-lecture.html .

http://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v25/d308 .

www.nobel.se/peace/laureates/1970/press.html .

See Google Ngrams: https://books.google.com/ngrams .

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/14/business/energy-environment/14borlaug.html .

This analysis was inspired by Falcon ( 1970 , footnote 9).

https://ourworldindata.org/famine .

We are far from the first to recommend this characterization. Falcon ( 1970 ), the earliest reference that we have found, attributes the notion of “green evolution” to Morton Grossman. That symbolization did not catch on, but we nevertheless recommend it here.

Again, severe and wide spread malnutrition in many areas of the world in the 1960s (and before and since) is well substantiated. But evidence points to multiple sources of food insecurity, such as inadequate transport and storage, conflicts, and lack of purchasing power (Drèze and Sen 1990 ; FAO and WFP 2018 ).

Ahlberg, Kristin L. 2008. Transplanting the Great Society: Lyndon Johnson and Food for Peace . Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press.

Google Scholar

Bottici, Chiara, and Benoit Challand. 2006. Rethinking political myth: The clash of civilizations as a self-fulfilling prophecy. European Journal of Social Theory 9: 315–336.

Article Google Scholar

Brunner, Ronald D. 1987. Key political symbols: the dissociation process. Policy Sciences 20: 53–76.

Brunner, Ronald D. 1994. Myth and American politics. Policy Sciences 27: 1–18.

Burnier, Delysa. 1994. Constructing political reality: Language, symbols, and meaning in politics: A review essay. Political Research Quarterly 47: 239–253.

Clark, Tim W. 2002. The policy process: A practical guide for natural resources professionals . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Connelly, Matthew James. 2008. Fatal misconception: the struggle to control world population . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Conway, Gordon. 1997. The Double Green Revolution: Food for All in the Twenty-First Century . London: Penguin.

Cullather, Nick. 2010. The Hungry World: America’s Cold War Battle against Poverty in Asia . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Daly, Herman E. 1991. Steady State Economics . Washington, DC: Island Press.

Dorward, Andrew, Shenggen Fan, Jonathan Kydd, Hans Lofgren, Jamie Morrison, Colin Poulton, et al. 2004. Institutions and policies for pro-poor agricultural growth. Development Policy Review 2: 611–622.

Dreze, Jean, and Amartya Sen. 1989. Hunger and public action . Oxford: Oxford University Press on Demand.

Drèze, Jean, and Amartya Sen (eds.). 1990. The Political Economy of Hunger I–III . Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Ehrlich, Paul. 1968. The population bomb . New York: Nallentine.

Elder, Charles D., and Roger W. Cobb. 1983. The political uses of symbols . New York: Longman Publishing.

Evenson, Robert E., and Douglas Gollin. 2003. Assessing the impact of the Green Revolution, 1960 to 2000. Science 300: 758–762.

Falcon, Walter P. 1970. The green revolution: Generations of problems. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 52: 698–710.

FAO. 1946. World Food Survey . Washington DC: UN Food and Agricultural Organization.

Fitzgerald, Deborah. 1986. Exporting American Agriculture: The Rockefeller Foundation in Mexico, 1943–53. Social Studies of Sciences 16: 457–483.

Flood, Christopher. 2002. Political Myth . London: Routledge.

Friedrichs, Jörg. 2014. Who’s Afraid of Thomas Malthus? In Understanding Society and Natural Resources , eds. Michael Manfredo et al., 67–92. Dordrecht: Springer.

Gaud, William. S. 1968. The Green Revolution: Accomplishments and Apprehensions . The Society for International Development, Washington, DC March 8, 1968. http://www.agbioworld.org/biotech-info/topics/borlaug/borlaug-green.html . Accessed 1 Nov 2013.

FAO and WFP (2018). Monitoring food security in countries with conflict situations. A joint FAO/WFP update for the United Nations Security Council . United Nations Agricultural Programme and the World Food Programme. Issue 3. http://www.fao.org/3/I8386EN/i8386en.pdf . Accessed 15 Dec 2018.

Geertz, Clifford. 1993. Religion as a cultural system. The interpretation of culture: selected essays . London: Fontana Press.

Gollin, Douglas. 2006. Impacts of international research on intertemporal yield stability in wheat and maize: An economic assessment . Mexico, DF: CIMMYT.

Gunnell, John G. 1968. Social science and political reality: The problem of explanation. Social Research 35: 159–201.

Hardin, G. 1968. The tragedy of the commons. Science 162: 1243–1248.

Harwood, Jonathan. 2009. Peasant Friendly Plant Breeding and the Early Years of the Green Revolution in Mexico. Agricultural History 83: 384–410.

Huxley, J. 1964. Essays of a Humanist . London: Chatto and Windus.

Kumar, Kanikicharla Krishna, Kolli Rupa Kumar, Raghavendra Ashrit, Nayana Deshpand, and James William Hansen. 2004. Climate impacts on Indian agriculture. International Journal of Climatology 24(11): 1375–1393.

Harré, Rom, Jens Brockmeier, and Peter Mühlhäusler. 1999. Greenspeak. A study of environmental discourse . Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Hasell, Joe, and Max Roser. 2017. Famines. Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: https://ourworldindata.org/famines/ . Accessed 15 Jan 2018.

Holdren, John. 1974. Testimony, “Domestic Supply Information Act” held by the Committee on Commerce and Committee on Government Operations (Serial No. 93-107).

Hulme, Mike. 2009. Why we disagree about climate change: Understanding controversy, inaction and opportunity . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Lasswell, Harold, and A. Kaplan. 1950. Power and society . New York: Routledge.

Lasswell, Harold D., Daniel Lerner, and Ithiel Sola de Pool. 1952. Comparative study of symbols: An introduction . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Leffler, Melvyn P. 1992. A Preponderance of Power: National Security, the Truman Administration and the Cold War . Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Levenstein, Harvey. 2003. Paradox of plenty: A social history of eating in modern America , vol. 8. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Linnér, Björn-Ola. 2003. The return of Malthus: Environmentalism and post-war population-resource crises . Cambridge: White Horse Press.

Maharatna, Arup. 1992. The demography of Indian famines: A historical perspective (Doctoral dissertation) . London: London School of Economics and Political Science.

McCoullough, David. 1992. Truman . New York: Simon & Schuster.

McNeill, John R. 2000. Something new under the sun: An environmental history of the twentieth-century world . New York: W.W. Norton & Company.

New York Times . 1948. Population Outgrows Food, Scientists Warn the World. 15 September, p. 1.

Otero, Gerardo, and Gabriella Pechlaner. 2008. Latin American agriculture, food, and biotechnology: Temperate dietary pattern adoption and unsustainability . Austin: University of Texas Press.

Parthasarathy, B., A.A. Munot, and D.R. Kothawale. 1988. Regression model for estimation of Indian foodgrain production from summer monsoon rainfall. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 42: 167–182.

Patel, Raj. 2013. The long green revolution. The Journal of Peasant Studies 40: 1–63.

Perkins, John H. 1997. Geopolitics and the green revolution: Wheat, genes, and the Cold War . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pielke Jr., Roger. 2007. The honest broker: Making sense of science in policy and politics . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pielke Jr., Roger A. 2012. Basic Research as a Political Symbol. Minerva 50(3): 339–361.

Pinstrup-Andersen, Per, and Peter B. Hazell. 1985. The impact of the Green Revolution and prospects for the future. Food Reviews International 1: 1–25.

Poleman, T. 1975. World food: A perspective. Science 188: 561–568.

Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States. 1964. Harry S. Truman: Containing the Public Messages, Speeches, and Statements of the President, 1949 . Washington: United States Printing Office.

Rosset, Peter, Joseph Collins, and Frances Lappé. 2000. Lessons from the Green Revolution. Third World Resurgence 15: 11–14.

Sapir, E. 1934. Symbolism. In Encyclopaedia of the social sciences , 492–495. New York: Macmillan.

Shenker, Israel. 1970. ‘Green Revolution’ has sharply increased grain yields but may cause problems. New York Times .

Shiva, Vandana. 2016. The violence of the green revolution: Third world agriculture, ecology, and politics . Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

Smith, Harrison. 1948. The saturday review of literature, August 21, p. 20.

Stilgoe, Jack. 2018. Machine learning, social learning and the governance of self-driving cars. Social Studies of Science 48: 25–56.

Sullivan, Walter. 1966. Scientists warn on famine peril. New York Times , April 26, 1966, p. 13.

Thakur, Baleshwar, V.N.P. Sinha, M. Prasad, M. Sharma, R. Pratap, R.B. Mandal, and R.B.P. Singh (eds.). 2005. Urban and Regional Development in India . New Delhi: Concept Publishing.

USDA. 1961. The World Food Budget, 1962 and 1966 . Washington DC: USDA Economic Research Service, Foreign Regional Analysis Division.

Wagar, Warren W. 1982. Terminal Visions: The Literature of Last Things . Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Woods, Randall Bennett, and Howard Jones. 1991. Dawning of the Cold War: The United States’ Quest for Order . Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

Zachary, G. Pascal. 2018. Endless frontier: Vannevar Bush, engineer of the American century . New York: Simon & Schuster.

Download references

Acknowledgments

This paper had an usually long gestation period and we are thankful to many for patience in its completion. We are very grateful to Linköping University for supporting an extended faculty visit of RP and to CIRES at the University of Colorado for supporting an extended faculty visit of B-OL. No other funding supported this work. The paper has been improved by the comments of numerous colleagues over the past years. An earlier version of this analysis was presented as a keynote lecture at the 2015 PACITA conference in Berlin. The paper is also a deliverable within the Mistra Geopolitics Research Programme: Sustainable development in a changing geopolitical era (Mistra DIA 2016/11 #5). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Center for Science and Technology Policy Research, Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, University of Colorado, 1333 Grandview Ave, Campus Box 488, Boulder, CO, 80309-0488, USA

Roger Pielke Jr.

Department of Thematic Studies (TEMA), Environmental Change (TEMAM), Linköping University, TEMA-huset, Ingång 37, Campus Valla, Linköping, Sweden

Björn-Ola Linnér

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Roger Pielke Jr. .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Pielke, R., Linnér, BO. From Green Revolution to Green Evolution: A Critique of the Political Myth of Averted Famine. Minerva 57 , 265–291 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-019-09372-7

Download citation

Published : 26 March 2019

Issue Date : 15 September 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-019-09372-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Green revolution

- Political myth

- Technology assessment

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

History and Overview of the Green Revolution

How agricultural practices changed in the 20th century

- Understanding Your Forecast

- Storms & Other Phenomena

- M.A., Geography, California State University - East Bay

- B.A., English and Geography, California State University - Sacramento

The term Green Revolution refers to the renovation of agricultural practices beginning in Mexico in the 1940s. Because of its success in producing more agricultural products there, Green Revolution technologies spread worldwide in the 1950s and 1960s, significantly increasing the number of calories produced per acre of agriculture.

History and Development of the Green Revolution

The beginnings of the Green Revolution are often attributed to Norman Borlaug, an American scientist interested in agriculture. In the 1940s, he began conducting research in Mexico and developed new disease resistance high-yield varieties of wheat . By combining Borlaug's wheat varieties with new mechanized agricultural technologies, Mexico was able to produce more wheat than was needed by its own citizens, leading to them becoming an exporter of wheat by the 1960s. Prior to the use of these varieties, the country was importing almost half of its wheat supply.

Due to the success of the Green Revolution in Mexico, its technologies spread worldwide in the 1950s and 1960s. The United States, for instance, imported about half of its wheat in the 1940s but after using Green Revolution technologies, it became self-sufficient in the 1950s and became an exporter by the 1960s.

In order to continue using Green Revolution technologies to produce more food for a growing population worldwide , the Rockefeller Foundation and the Ford Foundation , as well as many government agencies around the world funded increased research. In 1963 with the help of this funding, Mexico formed an international research institution called The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center .

Countries all over the world, in turn, benefited from the Green Revolution work conducted by Borlaug and this research institution. India, for example, was on the brink of mass famine in the early 1960s because of its rapidly growing population . Borlaug and the Ford Foundation then implemented research there and they developed a new variety of rice, IR8, that produced more grain per plant when grown with irrigation and fertilizers. Today, India is one of the world's leading rice producers and IR8 rice usage spread throughout Asia in the decades following the rice's development in India.

Plant Technologies of the Green Revolution

The crops developed during the Green Revolution were high yield varieties - meaning they were domesticated plants bred specifically to respond to fertilizers and produce an increased amount of grain per acre planted.

The terms often used with these plants that make them successful are harvest index, photosynthate allocation, and insensitivity to day length. The harvest index refers to the above-ground weight of the plant. During the Green Revolution, plants that had the largest seeds were selected to create the most production possible. After selectively breeding these plants, they evolved to all have the characteristic of larger seeds. These larger seeds then created more grain yield and a heavier above ground weight.

This larger above ground weight then led to an increased photosynthate allocation. By maximizing the seed or food portion of the plant, it was able to use photosynthesis more efficiently because the energy produced during this process went directly to the food portion of the plant.

Finally, by selectively breeding plants that were not sensitive to day length, researchers like Borlaug were able to double a crop’s production because the plants were not limited to certain areas of the globe based solely on the amount of light available to them.

Impacts of the Green Revolution

Since fertilizers are largely what made the Green Revolution possible, they forever changed agricultural practices because the high yield varieties developed during this time cannot grow successfully without the help of fertilizers.

Irrigation also played a large role in the Green Revolution and this forever changed the areas where various crops can be grown. For instance, before the Green Revolution, agriculture was severely limited to areas with a significant amount of rainfall, but by using irrigation, water can be stored and sent to drier areas, putting more land into agricultural production - thus increasing nationwide crop yields.

In addition, the development of high yield varieties meant that only a few species of say, rice started being grown. In India, for example, there were about 30,000 rice varieties prior to the Green Revolution, today there are around ten - all the most productive types. By having this increased crop homogeneity though the types were more prone to disease and pests because there were not enough varieties to fight them off. In order to protect these few varieties then, pesticide use grew as well.

Finally, the use of Green Revolution technologies exponentially increased the amount of food production worldwide. Places like India and China that once feared famine have not experienced it since implementing the use of IR8 rice and other food varieties.

Criticism of the Green Revolution

Along with the benefits gained from the Green Revolution, there have been several criticisms. The first is that the increased amount of food production has led to overpopulation worldwide .

The second major criticism is that places like Africa have not significantly benefited from the Green Revolution. The major problems surrounding the use of these technologies here though are a lack of infrastructure , governmental corruption, and insecurity in nations.

Despite these criticisms though, the Green Revolution has forever changed the way agriculture is conducted worldwide, benefiting the people of many nations in need of increased food production.

- What You Need to Know About Acid Rain

- To the Right, To the Right (The Coriolis Effect)

- An Overview of the Last Global Glaciation

- Milankovitch Cycles: How the Earth and Sun Interact

- The Jet Stream

- An Overview of Municipal Waste and Landfills

- What Is Environmental Determinism?

- An Overview of El Nino and La Nina

- Drought Causes, Stages, and Problems

- Pluvial Lakes

- 8 Halloween Costumes to Keep You Bone-Dry

- Autumn Leaf Color: What's Elevation Got to Do with It?

- Why Is the Sky Blue?

- Woolly Worms: The Original Winter Weather Outlooks

- How Weather Affects Fall Colors

- Nitrogen: Gases in the Atmosphere

- International Network

- Policy Papers

- Opinion Articles

- Historians' Books

- History of Government Blog

- Editorial Guidelines

- Case Studies

- Consultations

- Hindsight Perspectives for a Safer World Project

- Global Economics and History Forum

- Trade Union and Employment Forum

- Parenting Forum

Development policy and history: lessons from the Green Revolution

Jonathan harwood | 14 june 2013.

Executive Summary

- Despite its success in increasing agricultural production, the Green Revolution largely failed to alleviate rural poverty.

- Major development agencies agree that the key to ameliorating poverty is technical assistance targeted at smallholders and establishment of institutions capable of delivering agricultural development programmes

- State-funded 'peasant-friendly' plant breeding in Central Europe and Japan around 1900 was very effective in assisting small farmers. Key to this success was strong support from regional governments, and knowledgeable staff at plant breeding stations who understood small farmers' concerns.

- Unfortunately, however, the European episode is virtually unknown in today's development community, and what was once known as 'the Japanese model' largely disappeared from the development literature after about 1980.

- By insisting upon sharp cutbacks in public expenditure since the 1980s, therefore, the 'Washington Consensus' has ignored the historic success of publically funded agricultural research in general and plant breeding in particular.

Introduction

In recent years the economist, Ha-Joon Chang, has argued that development policy needs to pay far more attention to history. For the policies promoted by donor agencies since the 1980s are diametrically opposed to those which were successful in Europe a century or so ago. While the general features of that argument are undoubtedly correct, in respect of agriculture Chang's focus has been upon state policies concerning credit, price supports, input subsidies, tariffs, provision of infrastructure, and land tenure. Almost nothing is said about the role of state-funded agricultural research. This is surprising given widespread agreement that such research was absolutely crucial for the successes of the 'Green Revolution' (GR).

GR refers to a series of agricultural development programmes in the global South introduced by Western agencies from the 1940s. Established initially by the Rockefeller Foundation, in Mexico, they spread during the 1950s and 1960s elsewhere in Latin America and to South Asia, attracting additional support from the US government and the Ford Foundation. The principal aim was to increase the productivity of maize, rice and wheat cultivation using the methods which had proved so successful in North America and Europe: improved seed, fertiliser and pesticide. Although the GR succeeded in boosting cereals production substantially, however, many farmers gained very little, and rural poverty persisted largely unchanged. The main reason, now widely recognised, was that the GR's technology was more appropriate for large commercial farmers than for small resource-poor ones. Over the last decade reports from several major development agencies - for example, the World Bank, the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), the Food and Agricultural Organisation of the UN (FAO) - agree that the key to alleviating rural poverty in the global South lies in providing technical assistance and institutions suited to the needs of small farmers. Since the GR was unable to do this during the 1950s and 1960s, however, the question remains: is this possible now and if so, how?

In this policy paper I draw upon my recent study of major agricultural transformations around 1900 in Europe and elsewhere in order to demonstrate that strong state support for agricultural research and extension, as well as policy and institutions tailored to the needs of peasant farmers, were highly effective. The first section outlines the problems which the GR encountered. The second describes the character of 'peasant-friendly' research and institutions in Central Europe and Japan around. 1900.

In the final section I discuss the implications of this history for current development policy.

The Green Revolution and its limitations

In aiming to boost agricultural production, the GR programmes of the 1950s and 1960s were undoubtedly successful. By contrast, planners gave little thought to the social impact of their interventions, with the result that rural poverty and malnutrition declined very little in most regions and worsened in some areas. Since the GR had been sold to Western politicians and taxpayers as a 'war against hunger', as Nick Cullather has recently shown, this disappointing outcome prompted a wave of criticism from the late 1960s.

Reacting to the criticism, many experts associated with the GR began to reflect upon the characteristics of past programmes in order to understand which features had contributed to failure (and occasionally to success). In this 'diagnostic' literature from the 1970s to the 1990s there are three recurring themes. First that programmes needed to be properly organised. Because both the ecological and economic conditions of farms in many areas of the developing world are so diverse, for example, it was deemed important that research and development activity be decentralised. Equally important was that the intended beneficiaries of programmes should be organised. Unlike large commercial farmers, peasant farmers were rarely well organised, thus less able to voice their needs and lobby government for resources or demand better terms from commodity distributors and processors.

Second, the degree of impact of programmes was seen to hinge upon the knowledge and attitudes of those experts who dealt with farmers day to day. Arrogance - i.e., a boundless confidence in Western science and an inclination to dismiss local knowledge, whether from scientists or farmers - was not uncommon and had often hampered programmes. In addition, sometimes it appeared that experts were ignorant of the problems faced by small farmers. Where experts came from abroad, intending to return home after a project's completion, their decisions upon which technology to use were sometimes affected more by their desire to impress future employers than by the needs of their resource-poor clients. Where experts running projects were locals, they often came from relatively well-off urban backgrounds and thus had neither first-hand experience of agriculture nor much sympathy with the needs of peasants

Third, a few commentators drew attention to a more fundamental weakness: the failure of many programmes to take into account the political dimensions of development. They argued that the most serious limitation of most development programmes in the 1970s was their failure to consider what was politically feasible. For example, since it was known that projects aimed at resource-poor farmers were typically captured by local elites, planners should have paid more attention to how existing administrative arrangements or political institutions could be changed (or outflanked) if GR programmes were to have any chance of succeeding.

This literature was rich in insights, revealing where the early GR programmes had gone wrong. But the odd thing about it is that for the most part it did not uncover anything new. Virtually all the problems which this literature identified in early development programmes had already been encountered (and solved) in Central Europe and Japan around 1900.

Peasant-friendly development in Europe & Japan around 1900

Had the GR planners of the 1950s and 1960s paid more attention to history, what might they have found? From the late nineteenth century, governments in several Central European countries systematically promoted programmes of what was then often called agricultural 'modernisation' but which can be seen, in many respects, as 'green revolutions'. Unlike the GR after 1945, however, the European programmes aimed not just to increase production overall but specifically to help peasant farmers become more productive. Various regions - in Switzerland, lower Austria, Alsace-Lorraine, and Germany - did so by establishing state agricultural experiment stations whose mission was to bring the advantages of modern plant breeding to the small farms which predominated in these regions. The stations sought to do this in several ways. Considerable effort was devoted to testing available plant varieties in order to advise the region's small farmers which of these were suitable for the prevailing growing conditions, both ecological and economic. Many stations also undertook the development of new varieties, taking as their starting material local farmers' varieties because these were well-adapted to local conditions. The new improved varieties were then distributed to local farmers at little or no cost. Several stations also offered courses in plant breeding so that interested local farmers could learn how to carry out basic procedures. And at least one station spent considerable time helping small farmers organise themselves into local crop improvement associations so that they could strengthen their position in the marketplace as well as vis a vis the state. By the 1920s some of these stations were making a substantial impact upon their regional economies, producing varieties which were so popular with smallholders that commercial breeders began to complain that the stations constituted 'unfair competition'.

Significantly, some of these stations had nearly all the hallmarks of success which the diagnostic literature of the 1970s was later to identify. In south Germany, for example, the stations' breeding and varietal-testing work was decentralised. Most of the staff were neither ignorant of peasant agriculture nor arrogant in their dealings with smallholders because they had usually grown up in the region in question and often were the sons of peasants. Moreover, unlike so many GR projects, the south German stations enjoyed strong political support from their regional governments. Indeed, they owed their very existence to decisions by state governments to set up institutions that would invigorate peasant agriculture. And since large farms were quite rare in south Germany, the stations' work could not be subverted by estate owners as has so often occurred in the global South since 1945.

Another context from which lessons might have been learned was the remarkable agricultural development of Japan from about 1880 to 1920 as outlined by Penelope Francks among others. At the start of the Meiji Era (1868-1911) Japan sent agricultural experts abroad who brought back the technology used on large American and British farms, but most of this - including imported high-yielding plant varieties - failed. From the 1880s, therefore, the government decided to develop new technologies which would be better adapted to Japanese growing conditions. Since Japanese farms were very small, there was no point in investing large sums in machinery; draft power was instead supplied by animals. When it came to choosing which varieties to plant, the state encouraged local farmers' organisations to test a range of native varieties, the best of which were then distributed throughout the relevant region. After 1900 the breeding of rice and wheat was taken over by state experiment stations. As in Germany, Japanese breeders took the best of the improved native varieties as their starting material, and the breeding process was organised in a decentralised manner. Unlike the GR after 1945, breeders took into account the circumstances in which farming actually took place, aiming not just to increase yield under the most favourable growing conditions but also to develop rice varieties suited to marginal conditions, including regions previously thought to be unsuitable for rice cultivation. Some of these varieties were very successful and soon became known abroad. Japanese dwarf wheat varieties, for example, were used by breeders in the Mexican Agricultural Program, the first of the GR programmes.

As the designers of GR programmes eventually recognised, a successful programme required not only high-yielding crop varieties but also institutions and policies which would promote the use of these varieties. Interestingly, the Japanese did just this. In addition to a wide-ranging irrigation system inherited from the nineteenth century, the government introduced state subsidies for fertiliser purchase, built an extension service (whose task was to show farmers how to use the new technology correctly) and promoted a network of local cooperatives with which extension agents could work. The result was substantially increased productivity using methods which did not require expensive imported technology and which absorbed large amounts of rural labour. The agricultural economy grew rapidly, generated the capital necessary for industrialisation, supplied raw materials for some industrial sectors and met the growing urban demand for food.

Despite their relevance to agricultural problems in the global South today, however, both these episodes still appear to be largely unknown within the development community. Indeed, if one looks at recent reports from the World Bank, IFAD or FAO on the problems of agricultural development in the global South, one finds them recommending a variety of approaches to assisting small farms which were already well-known a century ago.

The implications for development policy

What can one conclude from this history? From one point of view, it merely confirms what has often been said by agricultural economists: that public expenditure on agricultural research - in both the global North and South - has proved an extraordinarily good investment, yielding annual returns through increased production of at least 20-30 per cent and often much more. And this is true not just for agricultural research in general but for plant breeding in particular. Moreover, there is substantial agreement that (publicly funded) national agricultural research systems (NARS) in the developing world have been and are likely to be important in addressing the needs of smallholders. Where properly organised and funded, they can be more responsive to small farmers' needs than the private sector, and they are also essential for adapting international agricultural research to local conditions, both ecological and economic.

Nowhere is the necessity of state-funded research clearer than in the recent debate over whether agricultural biotechnology is the key to alleviating rural poverty in the South. Most informed observers agree that solving this problem is going to require public funding since the giant multinational seed companies - unsurprisingly - see no profit to be made from selling to poor farmers.

For the last thirty years, however, development policy seems to have turned a blind eye to this evidence. In parts of Europe and North America, for example, public-sector breeding has come under heavy pressure - from giant corporations as well as governments - to leave the development of new varieties to the private sector and concentrate instead on fundamental research in plant sciences (which seed companies want to see done but do not wish to pay for). The most striking instance of this kind took place in the UK when the Thatcher Government decided that state-funded research institutions such as the Plant Breeding Institute (PBI) at Cambridge should be sold off. Within a few years one prominent British plant-breeder had concluded that this process would eventually be seen as a disastrous error. He may well have been right. More recently the British plant biotechnologist, Denis Murphy, has argued that this policy is seriously hindering the development of important new plant varieties. Moreover, in 1996 an interim assessment of the impact of privatisation suggested that the sell-off of the PBI had not saved the government very much money, nor have the corporations which bought it made much money from it since. By 2006, accordingly, several research councils and advisory bodies were voicing concern at the undesirable impact of privatisation upon British plant breeding.

A comparable process has taken place in the developing world over the same period as major donors, embracing the market-based approach of the 'Washington Consensus', insisted upon cutbacks in public expenditure as a condition for countries receiving aid. The effects of this policy upon agriculture in many countries have been serious. National agricultural research systems were particularly hard hit because they lost funding not only from national governments whose budgets were much reduced but also from donors such as the World Bank and the US Agency for International Development (USAID), upon which many had come to rely between the 1950s and the 1970s. Inevitably, this has had a severe impact upon plant breeding; in some African countries between 1985 and 2001 funding for public-sector breeding was slashed more than tenfold. Many observers agree that extension systems are also in poor condition, and most countries in the global South cannot afford to fix them.

A year ago, the administator of USAID, Rajiv Shah, told The New York Times:

We are never going to end hunger in Africa without private investment. There are things that only companies can do, like building silos for storage and developing seeds and fertilizers.

He could not be more mistaken. For the historical record is clear: state-funded plant breeding, supported by appropriate institutions and policy, has been highly effective in assisting the productivity of small farms in Central Europe and Japan. More generally, the payoff from publically funded agricultural research in many countries has been huge. One can only wonder, therefore, why major development agencies have elected to run down the state sector since the 1980s. This hardly qualifies as 'evidence-based policy'.

How, then, might development policy be reformed? History, to be sure, cannot provide a recipe since conditions in the global South today are not replicas of those in Europe or Japan around 1900. But historical experience does provide a vantage point from which current problems can be reconsidered and available solutions reassessed. The most obvious lesson one might extract from the history of peasant-friendly plant breeding is that Western development agencies would do well to focus upon repairing the damage suffered by NARS in the global South since the 1980s. That would mean increasing research budgets, strengthening extension systems, and supporting staff training. And to judge from historical experience, this will only be worthwhile in countries whose governments are fully committed to alleviating rural poverty.

- Harwood, Jonathan

- Farming and food

Further Reading

Chang, H.-J. Kicking Away the Ladder: Development Strategy in Historical Perspective . London: Anthem, 2002.

Chang, H.-J. 'Rethinking Public Policy in Agriculture: Lessons from History, Distant and Recent.' Journal of Peasant Studies 36, no. 3 (2009): 477-515.

Cullather, Nick. The Hungry World: America's Cold War Battle against Poverty in Asia . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010.

Francks, Penelope. Technology and Agricultural Development in Pre-War Japan . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1984.

Harwood, Jonathan. Europe's Green Revolution and Others Since: The Rise and Fall of Peasant-Friendly Plant-Breeding . London: Routledge, 2012.

Murphy, Denis J. Plant Breeding and Biotechnology: Societal Context and the Future of Agriculture . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Strom, S. 'Firms to invest in food production for world's poor', New York Times , 17 May 2012.

About the author

Jonathan Harwood is Emeritus Professor of History of Science & Technology at the University of Manchester. His latest book is Europe's Green Revolution and Others Since: the Rise and Fall of Peasant-Friendly Plant Breeding (Routledge 2012). He continues to work on the history of agricultural sciences with reference to development. Email: [email protected]

Related Policy Papers

Addressing food poverty in ireland: historical perspectives, ian miller | 01 september 2013, papers by author, papers by theme, digital download.

Download and read with you anywhere!

- Download Kindle Version

- Visit Apple iBooks Store

Popular Papers

- 1 Why Thames Water is Top of Sue Gray’s Risk Register

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER!

Sign up to receive announcements on events, the latest research and more!

To complete the subscription process, please click the link in the email we just sent you.

We will never send spam and you can unsubscribe any time.

H&P is based at the Institute of Historical Research, Senate House, University of London.

We are the only project in the UK providing access to an international network of more than 500 historians with a broad range of expertise. H&P offers a range of resources for historians, policy makers and journalists.

Publications

Policy engagement, news & events.

Keep up-to-date via our social networks

- Follow on Twitter

- Like Us on FaceBook

- Watch Us on Youtube

- Listen to us on SoundCloud

- See us on flickr

- Listen to us on Apple iTunes

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Green Revolution in India : A Case Study

Related Papers

Shreya Sethi

TATuP - Zeitschrift für Technikfolgenabschätzung in Theorie und Praxis

Dr. Somidh Saha

Partition of British India in 1947 triggered a huge refugee crisis in India. In addition, low agricultural yield and high population growth fueled food insecurity. The fear of the Bengal Famine of 1943 was still fresh and the Indian Government wanted to prevent further famines. The philanthropic organizations of the USA (Rockefeller and Ford Foundation) collaborated with Indian policymakers and scientists that helped in the groundwork of the Green Revolution. Jack Loveridge explains how technology and international cooperation contributed to India's Green Revolution and what lessons can be learned for the future. The challenges related population control, environment, social and economic inequality in the Green Revolution were highlighted. Interview by Somidh Saha (ITAS-KIT).

International Journal of Health Sciences (IJHS)

Emil Stepha

Arunav Chetia

Journal of Ethnic Foods

Kavitha Ravichandran

The Green Revolution in India was initiated in the 1960s by introducing high-yielding varieties of rice and wheat to increase food production in order to alleviate hunger and poverty. Post-Green Revolution, the production of wheat and rice doubled due to initiatives of the government, but the production of other food crops such as indigenous rice varieties and millets declined. This led to the loss of distinct indigenous crops from cultivation and also caused extinction. This review deals with the impacts the Green Revolution had on the production of indigenous crops, its effects on society, environment, nutrition intake, and per capita availability of foods, and also the methods that can be implemented to revive the indigenous crops back into cultivation and carry the knowledge to the future generation forward.

isara solutions

International Research Journal Commerce arts science

Agriculture has always been the backbone of the Indian economy and despite concerted industrialization in the last six decades, agriculture still occupies a place of pride. It provides employment to around 60per cent of the total work force in the country. That’s why taken all steps for development of agriculture are important….like green revolution…

Irrigation and Drainage

Avinash Tyagi

International Res Jour Managt Socio Human

Food security will remain a concern for the next 20 years and beyond, globally. There has been no significant increase in crop yield in many areas, despite of HYV of seeds and chemical fertilizers stressing the need for higher investments in research and infrastructure, as well as addressing the issue of water scarcity. Climate change is a crucial factor affecting food security in many regions including India.

Sachin Shirnath

Agrarian Change and Development Planning in South Asia

Robert Chambers

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Adam B. Lerner

SWAYAM PRAKASH

American Journal of Agricultural Economics

Peter Hazell , Ramasamy Chinnachamy

Peter Hazell

Kamran Khan Niazi

Agricultural Growth With Sustainability: An Indian Perspective

Ananya Kulkarni

Joan Mencher

Md. Shojib Bhuiyan

Social Change

Dr Swarup Dutta

Open Access Journal of Environmental and Soil Sciences

Najib Umer Hussen

Madhumita Saha

Michelguglielmo Torri

International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability

Jonathan Harwood

Sanjib Mukhopadhyay

Agricultural History

Nicole Sackley

International journal of research in science and technology

Riya Chhikara

Clement Tisdell

Digvijay Negi

Stephen Parente

Adil Hasan Khan

Favour Simon

International journal of research in social sciences

sk tibul Hoque

IOSR Journals

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Annual Reports

- The BA Program

- Joint Degrees & Certificates

MA Thesis Archive

- PhD Fields of Study

- North-East Regional Consortium of Programs in African Languages

- Lindsay Fellowship for Research in Africa

- Spring 2024

- Spring 2023

- Yale Africa Film Festival 2021

- Religious Freedom and Society in Africa Scholar Database

- Research and Media

- TTES Working committee members

- Events and Opportunities

- TTES fellows

- Publications

2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 | 2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003

Akua Agyei-Boateng African Studies in the United States: A Divided Tradition

Gerardo Manrique de Lara Ruiz Pre-colonial and colonial legacies in the Houses of Chiefs of Botswana and Ghana

Leslie Rose Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons: Planting the Roots for a New Era of Museum Work

Connor Compton Black Star Soccer: Football and the Political Ideology of Kwame Nkrumah

Jonathan Doernhofer Spatial Considerations of Rural Economic Development: Assessing the Determinants of Rural Service Access in South Africa’s Riemland

Harry Green Threatening Exit: Democratic Disillusionment in South Africa After Zuma

Papa Yoofi Nketsiah The University as a site for the Efflorescence of Musical Culture:A Case Study of the Development of Folk Music in the University of Ghana

Ethan Timmins-Schiffman The Kankan-Kissidougou Road Is Not Paved

Sam Weber Church and State: On the role of the Catholic Church in the 2018 Presidential Election in the DR Congo

Lolade Siyonbola Black Migrant: Nigerian Identity Formation in New York, Tokyo and Mumbai

Catherine Labiran Literature, Human Rights and National Identity in Nigeria

Otis Illert The 1964 Zanzibar Revolution and the German Democratic Republic: Military Aid in Exchange for International Recognition

Mairead MacRae “We Intend To Cause Havoc”: Making Music and Meaning in a Zambian Rock Scene

Garret Nash Kongosa: The Anthropology of Rumor, Gossip, and Conflict in Cameroon

Ayalew Helinna Identity On The Margins – Constructing National Identity In Ethiopia

Erdong Chen Achievements and Challenges of China’s Special Economic Zones in Africa – A Case Study of the China-Nigeria Lekki Free Trade Zone

Lila Ann M. Dodge Professionally Oriented Contemporary Dance Training in Burkina Faso: Social and Somatic Foundations for a Transnational Career

Denise L. Lim What is African Literature?

Catherine Nelson The Role of Minerals in Economic Development in Ethiopia

Scott Ross Radio’s Role in Reducing LRA Violence and the Effects of Humanitarian Intervention

Kevin Winn The Effects of Short-Term Volunteers On Host Communities

Camille Raquel Davidson Africans on Exhibit: Investigating Poverty Tourism in South African Townships

Justin Scott “NOTHING IS RIGHT”: Fuel Subsidies, Popular Sentiment, and the Legacy of #OccupyNigeria

Klara Wojtkowska Crisis of Imagination in Mugabe’s Zimbabwe

Alexander Bowles Careers, Stigma and Mental Health Care: Community Psychiatric Nursing in Ghana

Zachary Obinna Enumah From Ujamaa to Usalama: A Changing Tolerance Towards Refugees in Post-Ujamaa Tanzania

Oluwadamilola Oladeru Evaluation of the Abiye Program, A safe Motherhood Initiative in Ondo State, Nigeria

Nyasha Karimakwenda Terrains of Struggle: Black Women’s Bodies As Sites of Violence During Apartheid

Michael Baca Millenarian Violence in Northern Nigeria: 1804-1985

David Bargueno Humanitarianism for Africa in the Age of Empire, The Congo Free State & German South West Africa, Then and Now

Katie Gualtieri “For he who does not die, poverty dies”: The Intersection of State Power and Survival Struggles of Young Rwandans

Andrew Iliff A Seed That Can Carry: Tradition, Authority and Power in Grassroots Transitional Justice

Rachel Mandel The Potential and Limitations of Health-Based Organizations for Minority Sexual Rights

Eva Namusoke Pulpits and Politicians: The Relationship Between Church And State In Uganda

Philip Bonney The Politics of US Africa Command: The Effects and Limitations

Seraphine Hamilton The New “Other” in Post-Apartheid South African Literature

Mohamed Rafiq Colonial Memories, Contemporary Health: How Tanzanian Muslims Utilize the Past in Therapeutic Decisions

Jason Warner Sovereignty, Peace, and Pan-Africanism: The Construction of a Decolonized Theory of African International Relations

Sarah Beckham Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapies in Resource-Poor Settings: A Mixed-Methods Case Study in Rural Tanzania

Carol Gallo Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration of Former Combatants: A Critical Nexus Between Human Rights and Development

Nomcebesi Ndlovu Constructions of Customary Law: A Legal Historical Perspective of Women in KwaZulu-Natal

Kimberly Roosenburg Partners in Protection? Sport Hunting as a Means to Wildlife Conservation

Rachel Silver Power, Voice, and Censorship: Exploring Discourse on Female Circumcision and its Implications for Transnational Feminist Engagement

Chimamanda Adichie The Myth of “Culture”: Sketching the History of Igbo Women in Precolonial and Colonial Nigeria

Matthew Kustenbauder Legio Maria: The History of a Messianic Movement in Africa

Andrew Offenburger Decentralized History: The Xhosa Cattle-Killing and Post-Apartheid South Africa

Jenny Kline Rainbow Nation in Search of a History: The Evolution of the South African History Curriculum

Heather McGorman Creating Alternative Centers of Power: An Examination of the Peace-Building Process in Uganda Under the NRM

Singto Saro-Wiwa The Development of the Tourism Industry in Nigeria

Nancy Steedle Western Interaction and Development in Africa: Evidence of Extraversion

Feyisetan Adunbi The New Battleground: Women, Sexual Violence and the War in Darfur

Elizabeth Ashamu The History of Lebanese Immigration to Guinea

Abigail Koch From Hamba Kahle to Umkhonto: The African National Congress Between 1949 and 1961

Beverly Lwenya New Developments, Newer Discourse: The Emergence of Contemporary Kenyan Cinema and its Challenges

Lucy Moore National Identification in Contemporary Nigeria and South Africa

Reynolds Richter Food Rationing, Labor, and Citizenship in Kenya During World War II

Laura Smalligan Untangling the Serpent: State Fetishism and the Art of Dahomey

Nora Staal Peace in Sudan: The Comprehensive Peace Agreement and Prospects for Long Term Stability

Henry Kwan Hired Guns, Pinstripe Suits and CEOs: The Modern Corporate Mercenary and the Privatization of Warfare in Sub-Saharan Africa

Ashley Lynn Early Written Kiswahili: History and Translation of Kiswahili in Arabic Script

Jeffrey Meserve Narrating the African “Other”: (Re)Reading Camões, Os Lusíadas, and Portuguese Encounters with Africa, 1492-1572

Omolade Adunbi Nigeria: Democratization, Economic Growth, and the Politics of Truth and Reconciliation

Robera Battal Relocating the Periphery: Amharization and the Politics of Ethiopia’s Resettlement Scheme

Judd Devermont Refining Racial Identities on the South African Sugar Belt, 1851 – 1913

Kristen Gilmore Is Qadafi Rational?

Amanda Whiddon Blood on the Altar: The Role of the Catholic Church in the Rwandan Genocide

Sharon Jackson Empowerment, Women, and HIV/AIDS in Kilimanjaro, Tanzania: Quantitative and Qualitative Exploration

Larissa Leclair Historical Images and Contemporary Analysis: Reclaiming the Archive and Re-looking at History

Mukhtar Mohamed Armed Conflict and HIV/AIDS: The Impact on Children in Sub-Saharan Africa

Kwesi Snsculotte-Greenidge Decentralization Versus Democratization: An Analysis of Ethiopia’s Experiment with Ethnic Federalism

Amelia Shaw Interactive Communication Strategies for Anemia Reduction in Chole, Tanzania

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

A detailed retrospective of the Green Revolution, its achievement and limits in terms of agricultural productivity improvement, and its broader impact at social, environmental, and economic levels is provided. Lessons learned and the strategic insights are reviewed as the world is preparing a "redux" version of the Green Revolution with ...

Learn how the Long Green Revolution shapes the global agrarian change and challenges the conventional narratives of development and modernization.

Abstract. The Green Revolution refers to a series of research, development, and technology transfer initiatives, occurring between 1943 and the late 1970s in Mexico, which increased industrialized ...

The Green Revolution has won a temporary success in man's war against hunger and deprivation; it has given man a breathing space. If fully implemented, the revolution can provide sufficient food for sustenance during the next three decades.

Unit 9: The Green Revolution. Note: This activity was adapted from the 2011 AP World History exam DBQ created by the College Board. PROMPT: Evaluate the causes and consequences of the Green Revolution in the period from 1945 to the present. Instructions: Read the following documents and determine if they address causes or consequences of the ...

Green revolution, great increase in production of food grains (especially wheat and rice) that resulted in large part from the introduction into developing countries of new, high-yielding varieties, beginning in the mid-20th century. Learn more about the green revolution in this article.

Describe what the Green Revolution was. Explain the effects of the Green Revolution. Identify lessons learned from the Green Revolution that can help address 21st century issues.

We find it useful to distinguish between an "early Green Revolution" period (1961 to 1980) and a "late Green Revolution" period from 1981 to 2000. Table 1 shows that in the early Green Revolution, MVs contributed substantially to growth in Asia and Latin America, but relatively little in other areas.

This paper critiques the so-called "Green Revolution" as a political myth of averted famine. A "political myth," among other functions, reflects a narrative structure that characterizes understandings of causality between policy action and outcome. As such, the details of a particular political myth elevate certain policy options (and families of policy options) over others. One ...

The Green Revolution, or the Third Agricultural Revolution, was a period of technology transfer initiatives that saw greatly increased crop yields. [ 1][ 2] These changes in agriculture began in developed countries in the early 20th century and spread globally until the late 1980s. [ 3] In the late 1960s, farmers began incorporating new technologies such as high-yielding varieties of cereals ...

The term Green Revolution refers to the renovation of agricultural practices beginning in Mexico in the 1940s. Because of its success in producing more agricultural products there, Green Revolution technologies spread worldwide in the 1950s and 1960s, significantly increasing the number of calories produced per acre of agriculture.

Abstract The Green Revolution refers to a series of research, development, and technology transfer initiatives, occurring between 1943 and the late 1970s in Mexico, which increased industrialized ...

Despite its success in increasing agricultural production, the Green Revolution largely failed to alleviate rural poverty. State-funded 'peasant-friendly' plant breeding in Central Europe and Japan around 1900 was very effective in assisting small farmers. Key to this success was strong support from regional governments, and knowledgeable staff ...

For the most part, students attempted a thesis for this year's question. Because the vast majority of students identified the origin of the Green Revolution as monocausal, the thesis needed to specifically state only one cause and two consequences.

Uneven distribution among small and large farmers is apparent in three ways: small. farmers' lack of funds to take advantage of Green Revolution technology; insufficient. information and resources available to small farmers to effectively apply the technology; and the. absence of government support for small farmers.

The paper deals with the effects of the green revolution (GR) technology on poverty both conceptually and empirically. It provides a brief overview of…

Chapter 33 presents a history of the Green Revolution, the most significant improvement in agricultural production in the twentieth century. After reviewing the Green Revolution's origins in Italy and the USSR, it describes the wheat and rice high-yielding varieties produced at CIMMYT and IRRI in the 1950s and 1960s and their spread to India ...

The term "Green Revolution" was introduced to contrast America's foreign policy with the violence associated with Red guerilla movements. 4 "Green", as opposed to "Red", was the color of peace. Peaceful scientific progress was presented as the capitalist alternative to combat hunger, poverty and inequality [28].

YOU SAY YOU WANT A GREEN REVOLUTION, BUT ARE ITS COSTS GREATER THAN ITS BENEFITS? A Thesis by Joseph William George Livaich

The Green Revolution in India was initiated in the 1960s by introducing high-yielding varieties of rice and wheat to increase food production in order to alleviate hunger and poverty. Post-Green Revolution, the production of wheat and rice doubled due to initiatives of the government, but the production of other food crops such as indigenous rice varieties and millets declined. This led to the ...

the 'green revolution'. To summarise of less a continuous area with a lar ge. degree of ecological and agro-climatic while the new technology has expanded employment in the short run, in the long run, with further advance in me- chanisation, there is a serious risk of a. negative employment effect from it.

The 1964 Zanzibar Revolution and the German Democratic Republic: Military Aid in Exchange for International Recognition. Mairead MacRae "We Intend To Cause Havoc": Making Music and Meaning in a Zambian Rock Scene. Garret Nash Kongosa: The Anthropology of Rumor, Gossip, and Conflict in Cameroon. 2014. Ayalew Helinna