Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Despite an increase in voter turnout during the 2018 U.S midterm election, about half of all eligible voters didn’t cast their ballot on election day.

Political scientist Emilee Chapman says compulsory voting conveys the message that each citizen’s voice is expected and valued. (Image credit: Courtesy Emilee Chapman)

To increase voter turnout in elections, some scholars – including Stanford political scientist Emilee Chapman – have suggested making voting compulsory in the United States. The U.S. would then join countries such as Australia, Belgium and Brazil, which all require universal participation in national elections.

In an article published in the American Journal of Political Science , Chapman builds on existing scholarship to make the case for mandatory voting. Chapman sees voting as a special occasion for all citizens to show to elected officials they are all equal when it comes to government decision-making.

“The idea of compulsory voting is that it conveys the idea that each person’s voice is expected and valued,” said Chapman, an assistant professor of political science in Stanford’s School of Humanities and Sciences . “It really offers this society-wide message: There is no such thing as a political class in a democracy. Voting is something that is for everybody, including and especially people at the margins of society.”

If everyone votes, it reminds public officials they are accountable to all citizens – not just the most vocal and active, said Chapman, who is also on the advisory board of the McCoy Family Center for Ethics in Society .

There are many opportunities other than voting for civic engagement: Citizens can petition representatives, donate money to a campaign or even stand for office themselves, Chapman said. But mandatory voting is the simplest way to ensure everyone engages in political decisions, she said.

“When you have these moments where people know that they will be called upon to participate as citizens, it helps reduce the friction that comes with trying to figure out how to navigate what their role as a citizen is – especially given how complicated government is and the many ways to influence policy,” said Chapman. “I think it’s often very hard for people to figure out how to make their voice heard effectively.”

The case against mandatory voting

With such tight midterm races across the U.S., the motivation to vote was high and a sense of civic duty was strong. But if voting was required, some skeptics worry that citizens would no longer vote for these intrinsic reasons but instead vote out of a fear of being punished.

To address this concern, Chapman pointed to Australia, a country that has had compulsory voting in their national elections since 1924. According to one survey Chapman referenced in the paper, 87 percent of Australians said they would “probably” or “definitely” still vote if it was not required.

What explains Australians’ desire to still vote, with or without the law? Chapman said the government is able to offset any fear of retribution by taking a soft approach to disciplining nonvoters. This she said, maintains a positive perception to voting.

“Australia is one of the most effectively enforced compulsory voting systems in the world, but even there, excuses for nonvoting are readily granted and many cases of unexcused abstention are not pursued,” said Chapman in the paper, noting that only about one in four Australian nonvoters actually pay a fine. “Given the low enforcement rate, it seems likely that Australia has achieved its high participation rates because people in Australia see the law as reflecting a moral duty to vote. People are not obeying just because they fear they will be punished,” she said.

An uninformed electorate

Some critics of mandatory voting argue that it would introduce uninformed voters into the electorate, which they say would result in election outcomes not representative of public opinion. But according to Chapman, the evidence supporting this claim is ambiguous.

In addition, there are other challenges that may arise when only people who are interested in politics vote, said Chapman.

“If you allow the electorate to restrict itself to only people who are already interested in politics on its own and ask them for their input, then you are only going to have people who already have a lot of power in society and are familiar with what using that power can do for them,” Chapman said. Officials have an incentive to prioritize the concerns of likely voters over non-voters, she said. “And as a result, you are going to see a real difference in what interests are represented in public.”

A right not to vote?

Others critics have also argued that forcing citizens to vote restricts civil liberties: People should decide for themselves how they want to exercise their citizenship rights. In other words, the right to vote is also the right not to vote.

“The right to vote is based on the idea that we need to make public decisions together,” said Chapman. “I think there is a tendency to construe voting as a form of expression as opposed to participation in a collective decision. Those are very different acts.”

Once those two ideas are disentangled, Chapman said there are ways to structure a system that would not violate civil liberties raised by critics. For example, there could be religious exemptions, formal abstentions or an option to simply select “none of the above” for voters who do not like any of the candidates.

But as Chapman cautions, compulsory voting should not be seen as a one-stop solution to solving problems in democracy. And she is realistic about hurdles to any implementation. For example, there would need to be a secure system that would keep voter rolls up-to-date and registration would need to be streamlined. There are also material barriers that prevent certain populations from voting; for example, the homeless often cannot meet residency requirements needed to vote. These obstacles exist whether voting is mandatory or not, said Chapman.

“Democratic reform is something we should really maintain as an important value for democracy and not just think that opportunity alone is enough when it comes to voting,” she said.

Media Contacts

Melissa De Witte, News Service: (650) 725-9281, [email protected]

- Wednesday, August 28, 2024

- Get Involved

The Student Newspaper of Washington College since 1930

Should voting be made mandatory in the United States?

By Alaina Perdon

Elm Staff Writer

As Americans, we are privileged to live in a society in which we have the right to decide our country’s political course by casting our vote. Yet, our nation continually faces the issue of low voter turnout, meaning not every community’s voice is well-represented. Mandating voter participation could solve this disparity, ensuring equal opportunities for representation.

The 2020 presidential election saw record-breaking voter turnout; the United States Elections Project reports that almost 150 million people cast a ballot. But this election was a historical outlier.

During the 2014 midterm elections, national voter turnout rates were at their lowest levels since 1942, with less than 37% of the eligible population making it to the polls, according to U.S. Elections Project reports. More striking, voter turnout can be as low as 4% when municipalities hold special elections.

To ensure an effective democracy in which politicians represent the interests of all citizens, it is essential that as much of the population votes as possible. When there is low voter turnout, a small percentage of the population can end up controlling major political decisions. U.S. Censusing data shows these fortunate individuals most often reside in predominantly white, wealthy communities.

“Voting access is the key to equality in our democracy,” former U.S. house representative John Lewis said. “The size of your wallet, the number on your zip code shouldn’t matter. The action of government affects every American so every citizen should have an equal voice.”

Poor voter turnout cannot simply be attributed to inaction on the part of the individual. While the poll taxes and literacy tests of early-1900s America are behind us, voter suppression is still a reality plaguing minority communities.

A joint investigation by Public Religion Research Institute and The Atlantic found twice as many Black and Hispanic individuals were incorrectly told they were not listed on voter rolls at the polls during the 2016 presidential election compared to their white counterparts. Similarly, twice as many minority voters reported difficulty finding a polling place in reasonable distance from their homes, a statistic further supported from research by NBC indicating that frequent changes to polling-site locations hurt minority voters more than white voters.

“It would be transformative if everybody voted,” former President Barack Obama said in a March 2015 public address. “The people who tend not to vote are young, they’re lower income, they’re skewed more heavily toward immigrant groups and minorities.”

It should already be the responsibility of the federal government to ensure all citizens have reasonable access to a polling location, an efficient voter registration process, and other election resources; however, the U.S. has clearly failed its citizens in these respects. The barriers placed to curb minority votes are an obstruction of democracy, benefitting only the fortunate few while marginalized communities continue to go underrepresented.

Mandatory voting, or civic duty voting, would eliminate some of these barriers, allowing fair representation of currently marginalized communities.

“Casting a ballot in countries with civic duty voting is often easier than it is in the United States. Registering to vote is a straightforward and accessible process, if not automatic; requesting a ballot or finding your polling place typically does not require calls to your local supervisor of elections or constantly checking online resources to ensure that your polling location has not changed,” Brookings Institute research analyst Amber Herrle said in a proposal for a nationwide voting mandate.

Civic duty voting shifts responsibility from the voter to the state, forcing the government to provide these necessary resources to its citizens. After adopting a civic duty approach to voting, Australia began using mobile polling facilities in hospitals, nursing homes, prisons, and remote Aboriginal communities to ensure that those who are unable to get to a polling location can still vote, according to a 2015 report by FairVote researcher Nina Jaffe-Geffner.

Prior to Australia’s implementation of mandatory voting, the voter rate had reached a low of 47% of registered voters, according to Jaffe-Geffner. Once voting was legally mandated, turnout rates increased, with over 80% of the eligible population participating in the last election.

One of the major arguments given by those against compulsory voting is that it leads to a greater number of uninformed voters. Roll Call columnist and stringent advocate for mandatory voting Norman Ornstein notes that, “those who choose not to vote are generally less educated on political issues.”

While uninformed voting is a valid concern, Ornstein argues this would incentivize federally regulated political outreach and education, making all citizens more politically informed.

Implementing mandatory voting may not be a feasible change for the U.S. without years of planning, but facing in that direction, even on a municipality level, would begin a positive shift in U.S. voter turnout.

To uphold our democracy, the U.S. should consider changing policies to make voting easier and more accessible for everyone. More voters at the polls means fair representation of every demographic, guaranteeing actual liberty and justice for all.

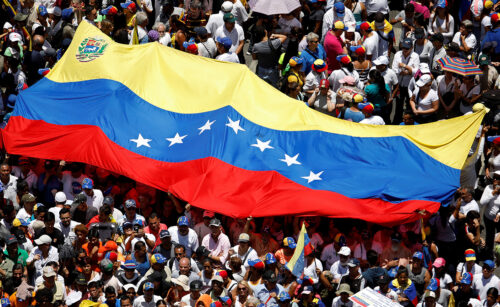

Featured Photo caption: With countries like Australia enforcing mandatory voting laws, many wonder if similar policies should be enforced in the United States. Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Compulsory Voting’s American History

- February 2024

- See full issue

Voter turnout was higher in the 2020 U.S. presidential election than it had been in 120 years. 1 Nearly sixty-seven percent of citizens over eighteen voted that November, exceeding rates that hovered around sixty percent in the twenty-first century and never broke sixty percent from 1972 to 2000. 2 Some pundits have read this recent record as a triumph. 3 But it can also be seen as a travesty: even with the best turnout since 1900, nearly eighty million eligible voters stayed home. 4

Slim turnout has long prompted reform efforts. 5 Yet the United States has always shied from one direct solution: requiring everyone to vote. “Compulsory voting” — where legislatures require attendance at the polls, often enforced by fines or penalties — exists in around two dozen countries, but nowhere in America, 6 relegating the idea to “goo-goo reformers” 7 and law review notes. 8

Recently, however, compulsory voting has entered mainstream debate. President Obama floated the idea in 2015 to fight money in politics and diversify the electorate. 9 A 2018 New York Times article piqued interest in Australia’s mandatory voting system. 10 And in 2022, E.J. Dionne Jr. and Miles Rapoport published a popular book arguing that “universal civic duty voting” will end voter suppression, improve representation, and boost belief in government. 11 Their work has inspired legislators in Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Washington to introduce compulsory voting bills. 12

This nascent debate marks an exciting effort to make the actual electorate more representative of the eligible electorate and potentially shift political power. 13 Yet modern debates have so far largely overlooked one angle of analysis: history. Though nearly no writers since the 1950s seem to have devoted more than two paragraphs to the history of compulsory voting efforts in the United States, 14 the idea has a rich American tradition. Policies first emerged before the Founding. And debates especially picked up beginning in the 1880s and through the Progressive Era, when twelve states considered the policy, including two — Massachusetts and North Dakota — that passed amendments letting their legislatures enact it. 15

This Note begins to excavate that history. In doing so, the Note illustrates the importance of the fact that these debates happened, highlights Progressives’ competing visions of democracy, and seeks to inform how advocates consider the policy today. Taking seriously the issue some contemporaries called the “most important” the Progressives faced 16 can help us better understand their democracy — and ours.

The Note proceeds as follows. Part I traces the history of attempts to institute compulsory voting in the United States, focusing primarily on the Progressive Era. Part II canvasses the main arguments at Progressive Era conventions for and against compulsory voting. And Part III considers what these debates illustrate about Progressive democracy and policy debates today.

I. Compulsory Voting Proposals in the United States

A 2007 note claimed that “there has been no real attempt to institute compulsory voting in the United States.” 17 Yet this Note — building on then-student Henry Abraham’s 1952 dissertation, which marks the fullest account of compulsory voting 18 but has never before been cited in a law review — unearths repeated American attempts to require voting. 19

This Part traces that history. It first recounts a handful of Colonial Era statutes imposing fines for non-voting. It then focuses on legislative and academic efforts from 1880 to 1920 to institute compulsory voting. And it ends by recounting sporadic proposals from the 1930s to the present. While the only place to mandate voting since the Founding is Kansas City, Missouri, the depth of these debates shows a history of democratic creativity often overlooked today.

A. Preconstitutional Policies

The American colonies had a highly restricted franchise. 20 Still, within this limited suffrage (often only propertied white males could vote), multiple colonies (and later one state) seemed to require eligible residents to attend elections. 21 This section briefly describes those laws.

In 1636, the Plymouth colony adopted a proto-compulsory voting law, fining “each delinquent” three shillings for “default in case of appearance at the election without due excuse.” 22 Virginia followed in 1649, charging 100 pounds of tobacco to voters who evaded the “lawful summons” to elections. 23 Maryland enacted a similar tobacco penalty in 1715, 24 while Delaware in 1734 charged twenty shillings, 25 and North Carolina in 1764 required voting for parish elections. 26 The one colony to constitutionalize compulsory voting was Georgia in 1777, imposing a maximum penalty of five pounds, but the provision was little used and was dropped in the state’s 1789 constitution. 27 No state then attempted to pass compulsory voting for nearly a century after the Founding. 28 While the motives for these laws are not clear, and they may not have been enforced, 29 these provisions suggest a longstanding aim of full participation, at least within the eligible electorate.

B. Pre-Progressive and Progressive Era Proposals

Compulsory voting debates took off a century later, first in spurts in the 1880s and ’90s, and then more robustly in the Progressive Era from 1900 to 1920. 30 This period saw major changes to election rules: Some expanded participation, like national amendments on women’s suffrage 31 and the direct election of senators, 32 along with “direct democracy” policies such as the initiative and referendum in many states. 33 Others were more technocratic, like building the bureaucracy or instituting city-manager local governments and off-cycle elections. 34 But a group of Progressives (and predecessors) also pushed a proposal missing from standard accounts of their agenda: compulsory voting. 35

This section charts that advocacy. From the 1880s to the 1920s, eleven states and one city introduced compulsory voting laws; six states considered constitutional amendments, including at four state constitutional conventions; and dozens of academics and advocates debated the idea. Successes were, admittedly, slim: one Kansas City ordinance and two enabling amendments in Massachusetts and North Dakota. But the range of these debates illustrates that compulsory voting was a serious proposal at the time — one that raised profound questions about the goals of democracy. This section catalogs these efforts; the next Part explores reformers’ arguments.

1. Legislative Efforts. — Massachusetts Governor Benjamin Butler gave the first big pitch for compulsory voting with a speech in 1883. 36 His legislature then heard petitions for the policy in 1883, 1885, and 1888. 37 Maryland was next, debating in 1888 a criminal “summons” for non-voters, and imposing fines of $5–$100 to support schools. 38 New York joined when Governor David Hill gave an 1889 address calling for fines or imprisonment for non-voters — citing some pre-Revolutionary examples — leading a legislator to introduce bills the next two years, which failed despite bipartisan backing. 39

The only law passed before 1900 was an 1889 Kansas City, Missouri, ordinance taxing each eligible voter $2.50 but “extinguish[ing]” the tax for all who voted. 40 The law, intended to “stimulate action” among those “‘above’ voting at common elections,” was rarely enforced and short-lived 41 : in 1896, in Kansas City v. Whipple , 42 the Missouri Supreme Court struck it down as a nonuniform tax that violated the state constitutional “free exercise of the right of suffrage.” 43

Beginning in 1900, momentum grew as the Progressive movement rose. In 1904, a New York legislator copied the 1888 Maryland bill, illustrating the spread of the idea. 44 Then Massachusetts saw a “veritable barrage” of proposals, considering (but rejecting) more than a dozen attempts from 1909 to 1918, with schemes ranging from poll taxes to disfranchisement to posting lists of non-voters. 45 Wisconsin rivaled this effort: six bills were introduced from 1903 to 1915, all exempting voters from a poll tax. 46 All died, 47 as did Connecticut’s 48 and Rhode Island’s. 49 The closest bill to passing came in Indiana in 1911, where a bill to make non-voting a misdemeanor passed the Senate twenty-nine to eighteen with no debate, but died in the House. 50 In 1926, a federal proposal surfaced when Senator Arthur Capper proposed that non-voters pay a one-percent tax on their income, aiming to add “millions” of new voters and encourage the “duty” of voting. 51 Politicians often resist changing the rules that elected them, 52 so this lack of uptake makes sense, but these persistent proposals suggest popular support.

2. State Constitutional Amendments. — The years before and during the Progressive Era saw sweeping revisions to state constitutions. Remaking their charters to address a changing political economy, states held fifteen constitutional conventions from 1889 to 1899, and nineteen more from 1900 to 1920. 53 Beyond standard proposals like the initiative and referendum, 54 among the bolder ideas was compulsory voting: six states considered — and two passed — constitutional amendments to allow the practice.

New York’s 1894 convention was the first to consider compulsory voting. After local Republican lawyer Frederick Holls wrote an extended tract pushing the idea in 1891, 55 he was elected as a convention delegate, where he raised an amendment “requiring” eligible voters to “exercise such right,” with penalties including losing the right to vote. 56 Debate spanned forty-two pages of the record, though the amendment was ultimately tabled. 57

North Dakota moved next. In 1898, the legislature passed and the people approved by a four-to-one majority 58 the country’s first statewide compulsory voting rule. This amendment allowed the legislature to “prescribe penalties for failing, neglecting or refusing to vote at any general election.” 59 The legislature, however, never used this permission, and in 1978 the voters repealed a sweep of election provisions at once, including the compulsory voting article. 60

After fourteen years, Ohio took up compulsory voting at its 1912 convention. 61 The delegates debated a proposal requiring the legislature to “compel the attendance of all qualified electors, at all elections held by authority of law.” 62 Not the convention’s top priority, the proposal failed to reach a full vote. 63

In 1918, the Massachusetts convention gave compulsory voting its biggest win. The initial proposal, giving the legislature “authority to provide for compulsory voting,” was rejected without debate on July 10. 64 Then, after the proposal won reconsideration, 65 delegates debated it on multiple occasions, spanning more than sixty pages of the record, 66 and drawing on a data-rich “bulletin” on the subject prepared for the convention. 67 Ultimately, after agreeing on an amendment ensuring the secret ballot, the proposal was put to the people, where, boosted by bipartisan appeal, 68 it won with a fifty-one-percent margin. 69 While the legislature has never used its permissive authority to pass a compulsory voting law, it considered numerous bills between 1919 and 1939. 70

Two more states considered compulsory voting amendments. First, Oregon’s legislature passed a 1919 amendment allowing the legislature to require voting, but sixty-eight percent of voters rejected it. 71 Last came Nebraska. In 1919, its constitutional convention debated letting the legislature “prescribe penalties” for not voting, but after three pages’ worth of debate, the amendment failed to pass. 72 Ultimately, these Progressive debates show that compulsory voting was a live political and legal issue with organized advocates on all sides.

3. Academic and Popular Commentary. — Compulsory voting was first popularized by British theorist John Stuart Mill, who in 1861 framed suffrage as a social “trust” that the state could mandate. 73 His thought traversed the Atlantic in 1888, when an obscure reform magazine devoted thirteen pages of its second volume to pitching compulsory voting. 74 Four years later, New York lawyer Frederick Holls’s essay drew on Mill’s theory of “duty,” 75 while Professor Albert Hart called compulsory voting “very much discussed” and compared the proposals to pre-Revolutionary policies (though he still rejected the idea as impracticable and unnecessary). 76

By the 1900s, with Progressivism spreading, compulsory voting went mainstream. By 1912, Special Libraries found so much compulsory voting commentary that it publicized a bibliography with fourteen news articles, fifty essays, and many proposed bills. 77 And leading law reviews considered if state power extended to mandating the franchise. 78 By 1914, the policy was so known that the Ohio Legislative Reference Department compiled work on the “live topic[],” one “sure to come up soon for legislative consideration.” 79

The debate resurfaced with creative arguments in the 1920s. A 1922 Harper’s essay advocated what amounted to a “poll-tax-in-reverse,” 80 a women’s group in 1924 proposed a $100 non-voting fine specifically to prod female voters, 81 and New York Republicans briefly pitched disfranchisement for non-voters (until they realized their party won). 82 With poor turnout in 1924 proving these pleas prescient, “non-voting” and “vote-slacking” became frequent sources of academic 83 and political consternation, inspiring proposals to reduce a state’s electoral college vote based on its past presidential election turnout 84 or impose a “tax” on vote slackers. 85 Progressives had created new opportunities for voting; now they wondered how to make people use it.

C. Post-Progressive Revivals

As the Progressive Era faded into the Great Depression and New Deal, compulsory voting lost its energy. 86 In 1930, Professor J. Allen Smith represented this trend, arguing the “unintelligent vote” encouraged by compulsory voting “will always be a menace to popular government.” 87 Legislatures apparently agreed: Just a few states introduced bills in the 1930s and 1940s. 88 Two states’ efforts to pass amendments failed in 1949. 89 And a federal effort to “investigate” 90 compulsory voting gained bipartisan support but petered out. 91 By 1952, Professor Abraham’s masterwork on compulsory voting concluded that the practice was undesirable and undemocratic. 92

A few proposals surfaced in the 1970s, but the idea was “not popular in America,” 93 and scholars were nearly “universal[ly] reluctan[t]” to it. 94 Commentary remained scant until the twenty-first century. 95 Then, however, the contested 2000 election brought a resurgence of commentary, 96 which accelerated with a New York Times debate series in 2011 97 and President Obama’s quasi endorsement in 2015. 98 By 2020, amid multiplying democratic crises, compulsory voting was again gaining adherents in academia, the press, and state legislatures. 99 Today, there is more momentum for compulsory voting than there has been since the Progressive Era.

II. Pros and Cons at Progressive Era Conventions

Part I illustrated that compulsory voting has a long American history. Its most prominent debates occurred from 1890 to 1920, mostly within the Progressive Era. This Part mines these discussions to understand the ideas and interests driving compulsory voting advocates. Drawing largely on records of the state constitutional conventions in New York (1894), Ohio (1912), Massachusetts (1917–1919), and Nebraska (1919–1920) 100 — which form the most sustained record of debate — the Part identifies the pros and cons raised in three common categories of argument: whether (A) the right to vote is a privilege or a duty; (B) higher voter turnout is desirable; and (C) the state could enforce compulsory voting.

A. Is the Vote a Privilege or a Duty?

Delegates at Progressive Era conventions often disagreed about the nature of suffrage. One fight proved core to the debate over compulsory voting: Is the vote a “privilege” (or “right” 101 ), or a “duty” (or “trust”)? 102 If voting is a privilege, the choice of whether to exercise it might seem personal; but if voting is a duty, it might be required. In other words, the “real question . . . goes down to the roots of the theory of the electoral process.” 103 This section traces these competing conceptions.

1. Pro: The Vote Is a Duty. — Many advocates viewed voting as a duty, echoing Mill’s argument. One delegate argued that “[t]his vote is not a thing in which [a person] has an option; . . . [i]t is strictly a matter of duty.” 104 On this view, the “real nature of the vote” is “entirely outside” any individual voter; far from “personal property” one could dispose at will, the vote conferred a “trust” which voters had an obligation to use “for the benefit of every person.” 105

This duty/privilege distinction was core to the case for compulsory voting: if voting is a “mere privilege,” it cannot be compelled, but if it is a “trust or obligation,” then neglecting it can “seriously affect the whole course and progress of a state” — justifying state compulsion. 106 The privilege to vote thus required using it well: those who “accept the blessings of democracy” should “assume the burdens of democracy.” 107 This argument was supported by limitations on suffrage at the time: since all of “we the people” were sovereign, yet only some could vote, that “delegated portion” must use the vote on behalf of the “rest.” 108 Only then would the “best men” be elected and the full electorate democratically represented. 109

2. Con: The Vote Is a Privilege (or Is Not a Legal Duty). — Opponents of compulsory voting saw voting as a “privilege” (or, relatedly, a “right”). This privilege “to be allowed to vote” 110 was a “priceless gift” 111 not to be exercised by rote requirement. 112 Some cited the fact that suffrage was not universal to show it could not be a duty for all. 113 More broadly, opponents believed compelling the vote violated the “general spirit of our laws” 114 and the nature of the right to vote, which included a right not to vote: “[I]f suffrage is a sovereign right of the citizen, he must be as free . . . not to exercise it as to exercise it . . . .” 115 Because the “whole theory of a democracy . . . exists by virtue of the consent of the governed,” 116 voters must get to choose how they exercise consent, not be forced “to the polls like cattle to the slaughter.” 117

Other opponents conceded that voting was a duty but one that could not be compelled. Even if the vote is a “trust,” voters retain a separate “duty” and “right” of “discriminating as to when [they] shall” vote. 118 And, even if voting “ should be performed,” that did not mean it must be performed. 119 It was especially important to protect the right not to vote to protest a lack of candidates “entitled to our suffrage.” 120 This view of the vote emphasized that voting was a personal act, not a public one.

B. Should We Seek Higher Voter Turnout?

Compulsory voting most directly addresses low voter turnout: to ensure everyone votes, make it illegal not to. The difficulty has been disagreement over the desirability of full turnout. For many, the “spectre of non-voting” 121 threatened democratic legitimacy. 122 But for others, the quantity of votes mattered less than the quality of the voter. This section explores these divergent views of turnout.

1. Pro: Non-voters Should Be Made to Vote. — Many supporters lamented low voter turnout. 123 To them, this “apathy of the electorate” formed a “peril to our republican institutions” 124 and was “detrimental to the best interests of the community.” 125 Non-voters were often derided as “slackers” (like those refusing to fight in World War I 126 ). 127 These slackers, along with other non-voting “holier-than-thou citizens,” needed a push to the polls. 128

For these slacker haters, compulsory voting was the ideal solution, as it aimed to “bring out practically the entire vote.” 129 Only then would all the “latent force of discernment and knowledge” bear on the “decision of vital political issues” 130 — making the electorate better resemble the community. They also believed that some non-voters needed to be heard. Drawing on debatable data, 131 many thought non-voters were workmen, farmers, and professionals 132 — the “educated vote of the community” 133 — and they needed to vote to counteract the “disgrace brought upon self-government, when the ignorant and worthless voters — the men who regard a vote as property . . . — are in a majority.” 134 Moreover, even if not all non-voters were virtuous, compulsory voting could create civic virtue. Since the policy would clarify that voting is a “civic duty,” 135 people would “become the most enthusiastic” voters, 136 as those who know they “must vote” will develop a “desire of doing so intelligently.” 137

Many Progressives also supported compulsory voting as a complement to other democracy reforms. One reform idea was “corrupt practices acts,” designed to reduce the influence of money in politics, 138 as candidates could often get “hired men” 139 to the polls or win because they had “means to hire the automobiles.” 140 With compulsory voting, there would be no “excuse for the use of money at election time under the pretence and guise of securing the attendance of voters,” since everyone had to attend. 141 Other major reforms were the direct democracy devices of the initiative and referendum (I&R). 142 Compulsory voting advocates believed the policies had to go together, since I&R backers meant to “leave the questions” not to “ part of the voters” but to “all of the voters.” 143 If I&R elections had low turnout, they would empower minority rule 144 and special interests. 145 A final connection was that if voters rejected the “short ballot” (reducing the number of elected positions), 146 compulsory voting was needed to add a “spur behind” overtired voters.” 147

2. Con: Non-voters Should Stay at Home. — Opponents saw less value in full participation. These opponents emphasized that the “many reasons for refraining from voting,” like long work hours or distance to the polls, made it wrong to penalize non-voting. 148 Others explicitly sought to protect non-voting as a means to signal dissatisfaction with politics. 149 What mattered was not the “ number of voters . . . but the number of informed voters. 150

These opponents denied that non-voters possessed special civic capacity. They described the idea that the best men do not vote as “per se an absurdity.” 151 To the contrary, “[f]ailure to vote . . . is abundant proof of a man’s unfitness to vote,” 152 and those “idle rich” who think it “beneath their dignity to go to the polls” are not just delinquent, but “not fit to be called an American.” 153 From this vantage, compelling the vote was nonsensical. There was “nothing gained” by requiring citizens to vote on issues of which they “have no understanding.” 154 And no one was “desirous” that those with “no political opinions should be forced” to claim them, since the “less of the unintelligent opinion we get the better.” 155 Here, the goal was not to make the electorate representative, but to reach the right outcomes. Those who believe they are too ill-informed to vote should be accepted “at their own valuation.” 156

Moreover, some Progressives saw conflict between compulsory voting and other reforms. A few believed compulsory voting might increase corruption, since those who vote only because they are forced to may be the easiest to buy off. 157 In this world, voters may sit around the polls until “some one appears with a bag full of silver dollars and . . . in a little while they all are voting.” 158 Others feared that mandating voting could undermine the referendum, since the “tremendous slacker potential vote” might all just vote negative or abstain. 159 And still others thought it a worse solution than the short ballot or less frequent elections: voters should be encouraged to participate by making politics simpler, not forced to show up or face punishment. 160

C. Can Compulsory Voting Be Enforced?

Any effort to compel voting needs state enforcement. Progressives were unsure how government could mandate voting — and whether it was legal. This section addresses debates over how compulsory voting could work.

1. Pro: Compulsory Voting Is Practical, Enforceable, and Legal. — A few supporters drew on domestic and foreign experience to frame their policy as practical. One referred to the practice as “in no sense . . . novel or untried,” citing Georgia’s early constitutional provision and Virginia’s colonial laws for historical support, along with Kansas City’s recent ordinance, as evidence it was still possible. 161 Others more often referenced other countries’ successes. The Massachusetts convention bulletin, for example, cited six countries’ examples. 162 If “[e]very Nation of progress has adopted” compulsory voting, then surely so could America. 163

Proponents were adamant that “ some proviso can be made” to enforce poll attendance. 164 They were also sure the policy would “accomplish the purpose of reducing the number of non-voters.” 165 The real question was how to enforce it. A commonly suggested idea was to impose a fine on non-voters. 166 Other options were to “cancel[]” voter registration 167 or “ridicule” non-voters. 168 More drastic penalties were imprisonment or disfranchisement, which would make non-voters lose their right to participate if they failed to use it. 169 While these penalties may have seemed draconian, supporters believed they would be rarely needed, since with the law “known,” citizens would “recognize their civic duty” and vote. 170 Supporters also sought to shore up the policy’s legality by analogy. Like compulsory jury service, court testimony, or military service, compulsory voting was just another way the state could enforce public duties. 171

2. Con: Compulsory Voting Is Impractical, Unenforceable, and Illegal. — Foes painted the policy as radical and untested. Some emphasized that the policy “does not exist anywhere in the United States” 172 and that “no precedent for such legislation can be found in the history of the government.” 173 Foreign countries’ experiences were similarly dismissed. What little “facts and reports” available showed no “special benefit” and instead depicted “rank failure” in “nearly every instance.” 174 Even if the policies worked elsewhere, skeptics wondered if “Tasmania” was relevant to American debate. 175 With little precedent, compulsory voting seemed an “un-American,” “[u]topian dream.” 176

Opponents further claimed there would be “no way of enforcing” it. 177 They first argued it would not raise turnout: some voters would cast a “blank ballot in protest”; 178 others would still stay home since their obstacles were “restricted naturalization laws” or “industrial exigencies,” not a lack of interest. 179

Moreover, every proposal raised for enforcement faced “practical objections.” 180 For example, tracking down each non-voter could involve a “great expense” or raise the specter of voters “herded to the polls by the police.” 181 Building a “complete system of registration” would similarly burden budding bureaucracies. 182 Disfranchisement as a penalty drew particular pushback. In an age of expanding suffrage, why should we countenance “limitation of the franchise,” especially given the many good reasons for non-voting? 183 Even if “excuse[s]” let citizens evade punishment, leaving the right to vote up to “three or four inspectors” felt despotic. 184 And, if the legislature “could disfranchise a large proportion of the citizens contrary to the desire of the people themselves,” the right to vote could vanish. 185

Beyond believing it a bad and impractical idea, opponents thought it was illegal. Here, many cited the Missouri Supreme Court’s ruling as a “leading authority” for the idea that the government may not compel all duties and compulsory voting violated the “free” exercise of suffrage. 186 Moreover, opponents thought analogies to taxation and military service were weak, as these were dubiously legal and addressed different kinds of rights. 187 Even those who supported the policy had legal doubts, fearing the “grave constitutional question” of imposing penalties “without a constitutional provision.” 188 Politics was the main barrier, but law loomed large.

These debates reflect how seriously delegates considered compulsory voting. Even if most proposals failed, compulsory voting was on the agenda, raising questions about the meaning of democracy, the importance of turnout, and the limits of government.

III. Lessons from Compulsory Voting’s History

Parts I and II illustrate that debates over compulsory voting have a long American tradition. Far from just a niche, radical idea, compulsory voting proposals have emerged in multiple historical periods, with particular intensity in the Progressive Era. This Part reflects on what this history can teach us — about both Progressive democracy and compulsory voting’s present-day revival.

A. Reflections on the Progressives

Compulsory voting’s main American momentum largely overlapped with the Progressive Era’s democracy reform movements. Yet these wide-ranging debates have almost entirely been left out of Progressive Era historiography. Reckoning with them offers three insights into the democracy Progressives pushed for.

First, the primary significance of the compulsory voting debates was that they happened at all. The Progressive Era has long been known as a time when electoral rules were transformed, home to both an explosion of direct democracy initiatives and a host of technocratic innovations. 189 But nowhere on that list is compulsory voting. True, the policy never gained wide acceptance. Yet the fact that the policy spawned six constitutional proposals, dozens of legislative efforts, and scores of articles suggests that some Progressives’ agendas spanned more than just those practices familiar today. 190 By looking beyond victorious reforms to those that fell short, we can see that Progressives’ quest to reimagine government was more varied than many historical accounts credit. 191

Second, delving into compulsory voting debates shows Progressives grappling with the meaning of democracy. Scholars have long noted that “Progressivism” encompassed widely varying visions of democracy, with some favoring mass participation and others seeking enlightened elite rule. 192 The debates over compulsory voting can help illuminate these contradictions, as the policy forced Progressives to grapple with questions of democratic legitimacy, how much voters could be trusted, and how far the state could intrude in citizens’ lives. As the institutions of democracy were changing, so too were the justifications needed about how and how much the people should participate.

Third, Progressives’ preoccupation with “non-voting” 193 showed that many saw popular participation as crucial to their agenda, aside from its democratic merits. Their vision of robust social welfare legislation required divesting power from existing elites — a goal which low turnout complicated and which mandatory voting might solve. Repeated efforts to link compulsory voting with Progressive staples like the I&R and anti-corruption laws connect policy with a broader effort to build Progressive power. This lens could explain the confusing debates over whether non-voters were slackers or virtuous citizens: Progressives believed the masses would support their anti-oligarchy agenda, 194 so they needed palatable ways to bring them into the electorate. Many Progressives may well have supported compulsory voting purely for ideas of fair representation. But viewing these advocates in political context can clarify how Progressives tried to achieve policy goals.

B. Reflections on the Present

Compulsory voting has regained traction today as a way to align the actual and eligible electorates, advance racial justice, and reduce elite political influence. 195 The debate so far has largely drawn on democratic theory and comparative data. 196 Both are key for showing the policy is worthwhile and workable. But this Note suggests that supporters should situate their proposals in American history to show that the policy is a real possibility and should not be overlooked as a way to solve our many crises of democracy. This section offers two ways that history can inform today’s debate and two places where modern advocates must go beyond Progressive arguments.

First, advocates can point to our long history to deflect charges that compulsory voting is radical, unconstitutional, or un-American. Multiple colonies and Revolutionary-era Georgia adopted the policy, two states constitutionalized the policy, and dozens more debated it. 197 This history does not answer whether we should mandate voting today. But it does — along with the breadth of experience with the policy abroad — suggest that we should take the policy seriously, just as Progressive Era delegates and their predecessors did.

Second, supporters can draw on America’s history to show the persistence of questions around low turnout and the meaning of democracy. Like in the Progressive Era, today many are seeking to reimagine democracy to respond to current crises. 198 Opponents today often dismiss compulsory voting as a Democratic Party power grab. 199 But stepping back from the partisanship of the moment (and the fact the opposite might be true 200 ), compulsory voting has had a far more bipartisan history; 201 and even if the parties then were less polarized, this history is at least a reminder that good-government elements across partisan lines can unite for pro-democracy reforms. 202 And, while compulsory voting may have political effects — as the mass populace supports more redistributive policies than political elites do 203 — the impact is unclear given that turnout may lack a partisan skew. 204 Yet the reason we keep debating compulsory voting is because too few people keep voting; 205 aligning this mismatch between the populace and represented electorate is not partisan but pro-democracy. Invoking the arguments that Progressive advocates raised can thus situate these proposals not as ad hoc partisan schemes but as longstanding efforts to make government more representative.

We also should learn from what these historical debates left out and consider how advocates can use new arguments to build a more successful coalition today. For one, the legal context has changed, with compelled speech doctrine, for example, presenting a doctrinal framework that early twentieth-century advocates would not have had to contend with. 206 We also know far more about how the policy might work: rather than speculate based on bad bulletins or shoddy statistics, we can draw on robust empirical work around turnout and governance. 207 Further, while proposals often bubble up at times of declining turnout, 208 the fact that today’s momentum came despite an uptick in 2020 participation suggests it is possible to build a less outcome-contingent coalition. Historical facts can give mandatory voting legitimacy; present ones are needed to confirm its value.

More crucially, we must better emphasize how compulsory voting might create a more diverse electorate. Here, the Progressive Era debates have little to offer. Nearly every advocate this Note identified was a white man, every state that considered the policy had vanishingly small non-white populations, and just two states (Nebraska and Oregon) let women vote at the time of debating compulsory voting. 209 Promisingly, however, advocates today pitch compulsory voting as a way to address racial turnout gaps and make the electorate reflect the diversity — along all possible dimensions — of the country. 210 Some respond that the policy might harm minority voters, especially if voter suppression policies persist. 211 Yet making this question central is a key update needed for assessing the merits of compulsory voting. Progressives failed to pitch the policy as inclusive, instead resting on their restricted ideas of delegated representation. Supporters today can draw on the pro-democracy arguments Progressives made about full participation, but must do more to build cross-racial coalitions to translate their vision into law.

These differences suggest that the arguments supporters pursue today will not and should not precisely track the Progressives’. They also suggest that our moment is different — and perhaps more ripe to finally make voting a universal duty. Drawing on the untapped history of compulsory voting while building on twenty-first-century ideals of inclusive democracy just might push us toward a just way to solve the perennial “non-voting” dilemma.

Compulsory voting may not yet be on the horizon. But the recent wave of advocacy has given the issue a greater spotlight than it has had in a century. Amid this momentum, we have much to learn from exploring compulsory voting’s overlooked American history. From the colonies to the Progressive Era to the twenty-first century, Americans have seriously considered making voting a duty of citizenship. That history helps illuminate the depth of democratic creativity in our Progressive past. And, given our crises of democracy today, that past should push us to keep reviving this powerful policy today.

^ National Turnout Rates 1789–Present , US Elections Project , https://www.electproject.org/national-1789-present [https://perma.cc/6V32-F6XV].

^ See, e.g. , Chris Cillizza, Turnout Really Was Historically Bonkers in 2020 , CNN (Jan. 29, 2021, 6:31 PM), https://www.cnn.com/2021/01/29/politics/turnout-2020-record-voting/index.html [https://perma.cc/2WXF-BT78].

^ See Domenico Montanaro, Poll: Despite Record Turnout, 80 Million Americans Didn’t Vote. Here’s Why, NPR (Dec. 15, 2020, 5:00 AM), https://www.npr.org/2020/12/15/945031391/poll-despite-record-turnout-80-million-americans-didnt-vote-heres-why [https://perma.cc/U4C5-7GSF].

^ For worries about “non-voting” dating back to the 1920s, see, for example , Charles Edward Merriam & Harold Foote Gosnell, Non-voting : Causes and Methods of Control 241–43 (1924).

^ See E.J. Dionne Jr. & Miles Rapoport, 100% Democracy: The Case for Universal Voting 53 (2022). The exact number varies based on how one defines the practice.

^ Nicholas Stephanopoulos, A Feasible Roadmap to Compulsory Voting , The Atlantic (Nov. 2, 2015), https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2015/11/a-feasible-roadmap-to-compulsory-voting/413422 [https://perma.cc/9GXV-EJBP].

^ See, e.g. , Sean Matsler, Note, Compulsory Voting in America , 76 S. Cal. L. Rev. 953, 955 (2003); Note, The Case for Compulsory Voting in the United States , 121 Harv. L. Rev . 591, 592 (2007) [hereinafter The Case for Compulsory Voting ].

^ Stephanie Condon, Obama Suggests Mandatory Voting Might Be a Good Idea , CBS News (Mar. 18, 2015, 5:50 PM), https://www.cbsnews.com/news/obama-suggests-mandatory-voting-might-be-a-good-idea [https://perma.cc/ZW4A-9Q85].

^ See Tacey Rychter, How Compulsory Voting Works: Australians Explain , N.Y. Times (Nov. 5, 2018), https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/22/world/australia/compulsory-voting.html [https://perma.cc/QX2F-DU6U].

^ Dionne & Rapoport, supra note 6, at xv–xxiv; see also Miles Rapoport & Alex Keyssar, Opinion, How to Boost Voter Turnout to Nearly 100 Percent , Bos. Globe (Jan. 8, 2022, 8:00 AM), https://www.bostonglobe.com/2022/01/08/opinion/how-boost-voter-turnout-nearly-100-percent [https://perma.cc/GLD3-J33J].

^ See H.B. 5704, 2023 Gen. Assemb., Jan. Sess. (Conn. 2023); H.B. 653, 191st Gen. Ct., Reg. Sess. (Mass. 2019); S.B. 5209, 68th Leg., 2023 Reg. Sess. (Wash. 2023).

^ Based on experience abroad, compulsory voting is no democratic panacea, but it can increase turnout. See, e.g. , Dionne & Rapoport , supra note 6, at 53–57. With an electorate that thus looks more like America, support for liberal or redistributive policies might increase. Cf. Benjamin I. Page & Martin Gilens, Democracy in America?: What Has Gone Wrong and What We Can Do About It 66–72 (2017) (describing how policy tracks the influence of the wealthy, not the people). But cf. Bertrall L. Ross II, Addressing Inequality in the Age of Citizens United, 93 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1120, 1187–88 (2018) (arguing compulsory voting would not lead to redistributive policies).

^ To the author’s knowledge, only one law review article in the past 107 years has devoted more than a footnote to past attempts at compulsory voting. See Nate Ela, The Duty to Vote in an American City , 66 How. L.J. 247, 256–95 (2022) (describing Kansas City’s brief compulsory voting experiment in detail); compare also, e.g. , Richard L. Hasen, Voting Without Law? , 144 U. Pa. L. Rev. 2135, 2173–74, 2174 n.154 (1996) (one footnote), with Note, Civil Conscription in the United States , 30 Harv. L. Rev. 265, 267 & n.15 (1917) (two footnoted paragraphs). One political science treatise on state constitutionalism notes four state debates, see John J. Dinan, The American State Constitutional Tradition 66, 315 n.11 (2006), and Dionne and Rapoport delve into Massachusetts’s history and a few other examples, see Dionne & Rapoport, supra note 6, at 54–55. But the only comprehensive history of compulsory voting is a 1952 dissertation by Professor Henry Abraham that gives eighty-three pages to American efforts yet is only available in a few archives and is not digitized. See Henry Julian Abraham, Compulsory Voting: Its Practice and Theory (1952) (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania) (on file with the University of Pennsylvania Library) [hereinafter Abraham dissertation]. This Note is deeply indebted to Abraham’s work. However, illustrating how little-known and dated this lone historical account is, Professor Alexander Keyssar’s masterful history of the right to vote does not cite it, noting that “compulsory voting awaits its historian.” See Alexander Keyssar, The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States 128, 231, 424 n.19 (2000).

^ See Abraham dissertation, supra note 14, at 116–55 (referencing California, Connecticut, Indiana, Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, North Dakota, Oregon, Rhode Island, and Wisconsin).

^ See 2 Proceedings and Debates of the Constitutional Convention of the State of Ohio , at 1192 (1913) [hereinafter Ohio Debates] (statement of Del. Frank Taggart); see also 3 Debates in the Massachusetts Constitutional Convention, 1917–1918, at 23 (1920) [hereinafter Massachusetts Debates] ( statement of Del. Allan G. Buttrick) (calling the question of compulsory voting “one of the most important matters that has been brought before this Convention”); 1 Journal of the Nebraska Constitutional Convention , at 537 (1921) [hereinafter Nebraska Debates] (statement of Del. Jerry Howard) (“[E]verybody who reads this proposal can see how important it is.”); 1 Revised Record of the Constitutional Convention of the State of New York , at 1059 (1900) [hereinafter New York Debates] (statement of Del. Frederick Holls) (calling the policy “a matter of very great and far-reaching importance,” though “not the most important one before the Convention”).

^ The Case for Compulsory Voting , supra note 8, at 598 n.45 (noting Georgia and Virginia pre-revolutionary statutes, Massachusetts and North Dakota amendments, and a local ordinance).

^ See generally Abraham dissertation, supra note 14.

^ As Abraham noted, “there has been an astonishingly extensive amount of toying with the idea in the United States.” See id. at 103.

^ See, e.g. , Keyssar , supra note 14, at 4–8.

^ Professor Albert Hart suggests that some of these laws are irrelevant because they were about deliberative town meetings, not traditional elections. See Albert Bushnell Hart, The Exercise of the Suffrage. , 7 Pol. Sci. Q. 307, 317–22 (1892).

^ Abraham dissertation, supra note 14, at 106–07 (quoting The Compact with the Charter and Laws of the Colony of New Plymouth 41 ( William Brigham ed., Boston, Dutton & Wentworth 1836)). The fine later grew to ten shillings, see id. , suggesting the law was not a dead letter. As early as 1636, other localities seemed to compel voting. Massachusetts codified that voters “shall have liberty to be silent and not pressed to a determinate vote,” while New Haven, Portsmouth, and Providence each fined voters who arrived to the voting site late. 3 Cortlandt F. Bishop, History of Elections in the American Colonies 192 (1893) (quoting The Charters and General Laws of the Colony and Province of Massachusetts Bay 201 (1814)). Southampton, New York, in 1654 and Lancaster, Massachusetts, in 1669, also seemed to mandate attendance at town meetings. See Hart, supra note 21, at 319–20.

^ Abraham dissertation, supra note 14, at 107 (quoting 1 The Statutes at Large; Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia 334 (William W. Hening ed., Richmond, Samuel Pleasants, Jr., 1809)). Virginia reenacted this scheme four times from 1662 to 1785, twice increasing the fine. Id. at 108.

^ Id. at 108. Maryland also appeared to fine “freemen” twenty pounds of tobacco as late as 1642 if they did not attend the election of the burgess or send a proxy. See Bishop , supra note 22, at 33–34.

^ See Abraham dissertation, supra note 14, at 108–09.

^ Id. at 109. A “[d]isability” could remove someone from the obligation of voting. Id. (quoting A Complete Revisal of All the Acts of Assembly, Of the Province of North-Carolina 305 (Newbern, James Davis 1773)).

^ Id. at 111; see Hasen, supra note 14, at 2174 n.154.

^ See Abraham dissertation, supra note 14, at 110–12. One major 1918 voting rights history does not mention compulsory voting. See Kirk H. Porter, A History of Suffrage in the United States (1918). The one mention of compulsory voting this Note finds in the interim is an 1860 speech by New York’s governor. See Governor Edwin D. Morgan, Annual Message to the 83rd Session of the N.Y. Legislature (Jan. 3, 1860), in 5 State of New York: Messages from the Governors 151, 196 (Charles Z. Lincoln ed., 1909) (“Every effort should be made to encourage, and, perhaps, compel the legal voters to exercise the right of voting . . . .”).

^ See Hasen, supra note 14, at 2174 n.154 (noting that Georgia and Virginia seemed to infrequently enforce their provisions).

^ While historians debate when the Progressive Era began, standard accounts situate it around 1900, preceded by the Populist and People’s Party uprisings of the 1880s and 1890s. See, e.g. , Arthur S. Link & Richard L. McCormick, Progressivism 11–20 (1983).

^ U.S. Const. amend. XIX.

^ Id. amend. XVII.

^ For direct democracy efforts, see generally Thomas Goebel, A Government by the People: Direct Democracy in America, 1890–1940 (2002) .

^ For examples of less democratic changes and these tensions within Progressivism, see generally Robert H. Wiebe, The Search for Order, 1877–1920 , at 167–77 (1967).

^ For the idea that the Progressive agenda coalesced into a standard series of reforms, see Sarah M. Henry, Progressivism and Democracy: Electoral Reform in the United States, 1888–1919, at 13 (1995) (Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University) (noting the “emergence of a consensus among self-defined progressives on a package of electoral reforms that they believed would promote ‘the people’s rule’”).

^ See Abraham dissertation, supra note 14, at 118 & n.2.

^ Id. at 119–20.

^ Id. at 142.

^ Id. at 143–46; see also Governor David B. Hill, Annual Message to the 112th Session of the N.Y. Legislature (Jan. 1, 1889), in 8 State of New York: Messages from the Governors , supra note 28, at 674–76; New York Debates, supra note 16, at 1064–65 (statement of Del. Frederick Holls).

^ Kansas City v. Whipple, 38 S.W. 295, 295 (Mo. 1896) (describing the charter provision).

^ See The Obligation of Suffrage , Kan. City Star , Dec. 24, 1896, at 4.

^ 38 S.W. 295.

^ Id. at 295–97 (quoting Mo. Const. of 1875, art. II, § 9).

^ Abraham dissertation, supra note 14, at 142, 146. Earlier, the Maryland legislator who had pushed the compulsory voting bill there also tried to introduce it in Pennsylvania, though apparently without success. See id. at 142–43.

^ Id. at 120–22.

^ Id. at 149.

^ Id. at 149–51.

^ Id. at 148.

^ Id. at 151.

^ Id. at 147–48.

^ Id. at 156–57. The House rejected the amendment. Id.

^ Cf. John Hart Ely, Democracy and Distrust 103 (1980) (noting politicians often try to ensure “they will stay in and the outs will stay out”).

^ See Dinan, supra note 14, at 8–9 (charting the history of state conventions).

^ See id. at 49–50.

^ Frederick William Holls, Compulsory Voting: An Essay (1891).

^ See New York Debates, supra note 16, at 1058 (proposed amendment to section 4 of article 2 of the constitution) (statement of Del. Frederick Holls).

^ Id. at 1058–100.

^ Abraham dissertation, supra note 14, at 117.

^ N.D. Const. art. II, § 127, repealed by N.D. Const. art. CIV, § 2.

^ Id. art. CIV, § 2 (“Article V, consisting of sections 121 through 129, and articles 36 and 40 of the amendments, of the Constitution of the State of North Dakota are hereby repealed.”). It makes sense that the 1970s amendments did not include compulsory voting, which had little traction then.

^ See Ohio Debates, supra note 16, at 1192–95. Ohio’s convention was a Progressive hub attended by former President Theodore Roosevelt and William Jennings Bryan; there, they debated classic Progressive policies such as the initiative, which Bryan called the “most effective means yet proposed for giving the people absolute control over their government.” See Dinan , supra note 14, at 60.

^ Ohio Constitutional Convention 1912: Proposals for Amendments as Introduced (1912) (Proposal No. 211).

^ Ohio Debates, supra note 16, at 1195.

^ Massachusetts Debates, supra note 16, at 20 (Resolution No. 282).

^ See id. at 20–83.

^ See 2 Bulletins for the Constitutional Convention 1917–1918, at 227 (1919) (Bulletin No. 24) [hereinafter Massachusetts Bulletin ].

^ See Abraham dissertation, supra note 14, at 128.

^ Massachusetts Debates, supra note 16, at 21.

^ Abraham dissertation, supra note 14, at 132–35.

^ See James D. Barnett, Compulsory Voting in Oregon , 15 Am. Pol. Sci. Rev. 265, 265–66 (1921); Oregon Secretary of State , Initiative, Referendum and Recall , in Oregon Blue Book 7, https://sos.oregon.gov/blue-book/Documents/elections/initiative.pdf [https://perma.cc/28XP-CEN2].

^ Nebraska Debates, supra note 16, at 537, 540. Only two states have since tried (and failed) to constitutionalize compulsory voting. See Abraham dissertation, supra note 14, at 151, 153 (citing examples in Maine and Rhode Island).

^ See John Stuart Mill, Considerations on Representative Government 205–06 (New York, Henry Holt & Co. 1873) (1861).

^ James Clement Ambrose, Compulsory Voting , 2 Our Day 276, 276–88 (1888).

^ Holls claimed that based on “extracts from hundreds of newspapers,” there was ninety-percent support for compulsory voting among editorials; though those numbers seem inflated, the presence of articles suggests widespread debate. See New York Debates, supra note 16, at 1074 (statement of Del. Frederick Holls).

^ Hart, supra note 21, at 308; see also id. at 319–22, 327. But see John M. Broomall, Compulsory Voting , 3 Annals Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. & Sci. 93, 95–97 (1893) (supporting compulsory voting and believing it enforceable via fine). Popular commentary also continued in the 1890s. See generally, e.g. , Morris S. Wise, Should Voting Be Compulsory? , Soc. Economist , Sept. 1892, at 143; James Bryce, The Teaching of Civic Duty , Forum , July 1893, at 552, 566.

^ See Special Librs. Ass’n, Select List of References on Compulsory Voting , 3 Special Librs. 32, 32–36 (1912).

^ See, e.g. , Note, Regulation and Limitation of the Right to Vote , 11 Colum. L. Rev. 278, 278–79 (1911); Note, supra note 14, at 267.

^ W.T. Donaldson, Compulsory Voting and Absent Voting with Bibliographies 3 (1914).

^ Samuel Spring, The Voter Who Will Not Vote , 145 Harper’s Monthly Mag. 744, 748–50 (1922); Abraham dissertation, supra note 14, at 173, 174 & n.1.

^ Abraham dissertation, supra note 14, at 175.

^ Id. at 176–77.

^ See Merriam & Gosnell , supra note 5, at 241–43; Charles H. Sherrill, Voting and Vote-Slacking , 221 N. Am. Rev. 401, 403–04 (1925) .

^ See Sherrill, supra note 83, at 403–04.

^ Arthur Capper, “ Let Us Tax the Vote Slacker , ” N.Y. Times Mag., Dec. 19, 1926, at 1.

^ In the first fifty results of a Harvard library search of “compulsory voting” (with the date range set from 1930 to 2000), just four focus on the United States.

^ See J. Allen Smith, The Growth and Decadence of Constitutional Government 52–55 (1930) .

^ See Abraham dissertation, supra note 14, at 149–53 (referencing California, Maine, and Wisconsin).

^ Id. at 151–53 (referencing Maine and Rhode Island).

^ Id. at 159 (quoting H.R. 641, 81st Cong. (1950)).

^ Id. at 163–65.

^ Id. at 244–51. As referenced earlier, though this Note disagrees with Abraham’s conclusions, it would not have been possible without his comprehensive study.

^ Kevin P. Phillips & Paul H. Blackman, Electoral Reform and Voter Participation: Federal Registration: A False Remedy for Voter Apathy 69 (1975).

^ Alan Wertheimer, In Defense of Compulsory Voting , in Participation in Politics 276–77 (J. Roland Pennock & John W. Chapman eds., 1975).

^ But see Hasen, supra note 14, at 2173–74 & n.154 (briefly describing the American history in a 1996 article); Ross Parish, For Compulsory Voting , Policy, Autumn 1992, at 15, 17 (supporting the policy).

^ See, e.g. , Martin P. Wattenberg, Where Have All the Voters Gone? 165 (2002).

^ See Should Voting in the U.S. Be Mandatory? , N.Y. Times (Nov. 7, 2011), https://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2011/11/07/should-voting-in-the-us-be-mandatory-14 [https://perma.cc/CJM2-QVFR].

^ See Condon, supra note 9. For one supportive response to President Obama’s proposal, see S tephanopoulos, supra note 7. For one conservative critique, see Jonah Goldberg, Progressives Think that Mandatory Voting Would Help Them at the Polls , Nat’l Rev . (Nov. 13, 2015, 5:00 PM), https://www.nationalreview.com/2015/11/mandatory-voting-progressive-bad-idea [https://perma.cc/G6CA-G3XZ].

^ See, e.g. , sources cited supra notes 11–13. See generally Tavi Unger, Mandatory Voting in Constitutional Context , 57 Harv. C.R.-C.L. L. Rev. 271 (2022).

^ This Note refers to these four as “Progressive Era conventions,” though New York’s 1894 convention precedes the core of the Progressive Era as defined in this Note, see supra note 30.

^ Though “privileges” and “rights” are distinct — what may be bestowed discretionarily versus what one is entitled to — both contrast with “duty,” something one is obliged to perform. In this sense, rights and privileges are about who is allowed to vote, while duties are about who must vote. For one definition of these distinctions, see Wesley Newcomb Hohfeld, Some Fundamental Legal Conceptions as Applied in Judicial Reasoning , 23 Yale L.J. 16, 55 (1913).

^ See Henry J. Abraham, What Cure for Voter Apathy? , 41 Nat’l Mun. Rev. 346, 347–48 (1952) (contrasting voting as “not a privilege but a duty, a public trust,” with voting as “not an inalienable right . . . [but] a privilege” that can be “deni[ed] to certain classes”); see also Donaldson , supra note 79, at 8–9 (comparing “duty imposed upon each elector” with “privilege”).

^ Merriam & Gosnell , supra note 5, at 242–43.

^ New York Debates, supra note 16, at 1062 (statement of Del. Frederick Holls).

^ Id. at 1061.

^ Ohio Debates, supra note 16, at 1193 (statement of Del. Frank Taggart).

^ Massachusetts Debates, supra note 16, at 31 (statement of Del. J. Franklin Knotts).

^ Ohio Debates, supra note 16, at 1192–93 (statement of Del. Frank Taggart). This argument reads today as paternalistic (at best), entrusting (near-exclusively) white men to speak for women and other residents denied the vote. For background on this exclusion, see Lloyd L. Sponholtz, Harry Smith, Negro Suffrage and the Ohio Constitutional Convention: Black Frustration in the Progressive Era , 35 Phylon 165, 165–67 (1974).

^ Massachusetts Debates, supra note 16, at 42 (statement of Del. John D.W. Bodfish).

^ New York Debates, supra note 16, at 1079 (statement of Del. David H. McClure).

^ Massachusetts Debates, supra note 16, at 66 (statement of Del. Patrick S. Broderick).

^ Id. at 25 (statement of Del. George P. Webster).

^ E.g. , id. (referencing the exclusion of people convicted of crimes).

^ Donaldson , supra note 79, at 18 (citing Hart, supra note 21, at 317, 319); see also New York Debates, supra note 16, at 1089 (statement of Del. Jerome S. Smith) (worrying about the “spirit of coercion” that is “everywhere rampant” in these proposals).

^ Kansas City v. Whipple, 38 S.W. 295, 297 (Mo. 1896).

^ New York Debates, supra note 16, at 1094 (statement of Del. Stephen S. Blake).

^ Id. at 1095 (statement of Del. Stephen S. Blake). These arguments around the “invasion of personal liberty” that came from forcing voting were seen to defeat the compulsory voting amendment in Oregon. See Barnett, supra note 71, at 266.

^ New York Debates, supra note 16, at 1077 (statement of Del. David H. McClure).

^ Id. at 1097 (statement of Del. William P. Goodelle) (emphasis added).

^ Id. at 1078 (statement of Del. David H. McClure).

^ Henry J. Abraham, Compulsory Voting 23 (1955).

^ See generally Donaldson , supra note 79; Merriam & Gosnell , supra note 5.

^ See, e.g. , Ohio Debates, supra note 16, at 1192 (statement of Del. Frank Taggart) (decrying that “but one-fourth of the entire people” had ever “exercised this privilege” of voting).

^ See Rapoport & Keyssar, supra note 11 (quoting Massachusetts Debates, supra note 16, at 42 (statement of Del. John D.W. Bodfish)). Another delegate chided the “vast number of stay-at-homes” at elections. Massachusetts Debates, supra note 16, at 30 (statement of Del. J. Franklin Knotts); see also Barnett, supra note 71, at 265 (noting that “waning interest in elections” caused “lamentation” in Oregon).

^ See generally, e.g. , Take Slackers into Army , N.Y. Times, Sept. 10, 1918, at 6.

^ E.g. , Nebraska Debates, supra note 16, at 539 (statement of Del. Jerry Howard); see also Massachusetts Debates, supra note 16, at 21 (statement of Del. Jerome S. Smith) (“Are they satisfied to . . . let the slackers remain at home?”).

^ New York Debates, supra note 16, at 1092 (statement of Del. De Lancey Nicoll).

^ Id. at 1070 (statement of Del. Frederick Holls).

^ Id. at 1063.

^ For an example of the not-too-detailed information that delegates had, see Massachusetts Bulletin , supra note 67, at 232–39.

^ Ohio Debates, supra note 16, at 1193 (statement of Del. Frank Taggart); see also Nebraska Debates, supra note 16, at 539–40 (statement of Del. Jerry Howard) (describing some non-voters as “merchant princes,” id. at 540).

^ New York Debates, supra note 16, at 1068 (statement of Del. Frederick Holls).

^ Id. at 1068–69; see also Nebraska Debates, supra note 16, at 539 (statement of Del. Jerry Howard) (lamenting that 25,000 “not illiterate but educated men, graduates of colleges and professional men” stayed home).

^ Ohio Debates, supra note 16, at 1194 (statement of Del. Frank Taggart); see also New York Debates, supra note 16, at 1075 (statement of Del. Frederick Holls).

^ Massachusetts Debates, supra note 16, at 29 (statement of Del. Jerome S. Smith).

^ New York Debates, supra note 16, at 1070 (statement of Del. Frederick Holls). New York Delegate Frederick Holls believed that compulsory voting would “tend to increase” the “intelligent and educated vote” by the “impetus which it would give to political education.” Id.

^ See Tabatha Abu El-Haj, Changing the People: Legal Regulation and American Democracy , 86 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1, 37, 38 n.221 (2011). For context on corruption worries, see Hill , supra note 39, at 675 (“Corruption, and not partisanship, is the great danger of the times.”).

^ New York Debates, supra note 16, at 1071–72 (statement of Del. Frederick Holls).

^ Massachusetts Debates, supra note 16, at 26 (statement of Del. Allan G. Buttrick).

^ Ohio Debates, supra note 16, at 1193 (statement of Del. Frank Taggart); see also Massachusetts Debates, supra note 16, at 28–30 (statement of Del. Jerome S. Smith) (arguing compulsory voting “will reduce corrupt practices to the minimum,” id. at 29).

^ See generally Goebel , supra note 33.

^ Massachusetts Debates, supra note 16, at 21 (statement of Del. Jerome S. Smith) (emphasis added).

^ Delegate Holls, for example, feared that initiative votes might “comprise[] practically only a moiety of the electoral body,” rendering the election a “mere farce.” See New York Debates, supra note 16, at 1069 (statement of Del. Frederick Holls).

^ Massachusetts Debates, supra note 16, at 62 (statement of Del. John W. McAnarney).

^ See Wiebe , supra note 34, at 167–77 (describing the short ballot).

^ Ohio Debates, supra note 16, at 1195 (statement of Del. Edward W. Doty).

^ E.g. , Massachusetts Debates, supra note 16, at 50 (statement of Del. Albert Bushnell Hart).

^ E.g. , id .

^ Abraham, supra note 102, at 348 (emphases added).

^ Massachusetts Debates, supra note 16, at 45 (statement of Del. George P. Webster).

^ Id. at 33 (statement of Del. James T. Barrett).

^ Barnett, supra note 71, at 266.

^ Massachusetts Debates, supra note 16, at 27 (statement of Del. Charles H. Morrill).

^ Id. at 45 (statement of Del. George P. Webster).

^ See id. at 46.

^ Ohio Debates, supra note 16, at 1194 (statement of Del. H.M. Brown).

^ Massachusetts Debates, supra note 16, at 65 (statement of Del. George P. Webster).

^ Id. at 51 (statement of Del. Albert Bushnell Hart); see also Nebraska Debates, supra note 16, at 539 (statement of Del. O.B. Spillman).

^ New York Debates, supra note 16, at 1064–66 (statement of Del. Frederick Holls).

^ Massachusetts Bulletin, supra note 67, at 232–39 (citing Austria, Belgium, New Zealand, Spain, Switzerland, and Tasmania). Other contemporary commentators similarly commented on other countries’ practices. See Note, supra note 14, at 267 n.14 (“It would appear that compulsory voting is quite generally established in civil law countries.”); William E. Hannan, Data Relating to Compulsory Voting 3–8 (1926) (citing experiences of Argentina, Australia, Austria, Spain, and other countries).

^ Massachusetts Debates, supra note 16, at 59 (statement of Del. James T. Barrett).

^ Nebraska Debates, supra note 16, at 539 (statement of Del. Jerry Howard) (emphasis added). If the “will of the people” favors compulsory voting, then the legislature will not be “so lacking in practical common sense” that it becomes “impossible” to execute. Massachusetts Debates, supra note 16, at 70 (statement of Del. J. Franklin Knotts).

^ Hannan , supra note 162, at 15 (citing Merriam & Gosnell , supra note 5, at 241).

^ E.g., supra notes 38–39 and accompanying text.

^ Massachusetts Bulletin , supra note 67, at 231.

^ Nebraska Debates, supra note 16, at 539 (statement of Del. Jerry Howard).

^ See Abraham dissertation, supra note 14, at 120–22; Ohio Debates, supra note 16, at 1193 (statement of Del. Frank Taggart); New York Debates, supra note 16, at 1079 (statement of Del. David H. McClure) (considering a proposal to disfranchise citizens after five years of consecutive non-voting). Disfranchisement is an odd penalty for those seemingly seeking to ensure that everyone votes. However, these debates took place in a context where the franchise was still restricted both formally and informally; even the policy’s supporters meant to mandate voting for eligible voters — not for every American.

^ Ohio Debates, supra note 16, at 1194 (statement of Del. Frank Taggart); see also New York Debates, supra note 16, at 1068 (statement of Del. Frederick Holls) (“When disfranchisement has lost its deterrent power, the ballot itself, and with it, all free institutions, will be doomed.”).

^ New York Debates, supra note 16, at 1073 (statement of Del. Frederick Holls) (calling compulsory voting “as important” as the Civil War draft); Massachusetts Debates, supra note 16, at 74 (statement of Del. George W. Anderson) (arguing if we can “draft men into the military service,” we can “draft men to the performance of their duty at the polls”).

^ Massachusetts Bulletin , supra note 67, at 231–32.

^ Kansas City v. Whipple, 38 S.W. 295, 297 (Mo. 1896); see also New York Debates, supra note 16, at 1089 (statement of Del. Jerome S. Smith) (“There is not a State in this Union where a system of compulsory voting has been introduced since the Declaration of Independence; not one.”).

^ Nebraska Debates, supra note 16, at 538 (statement of Del. O.B. Spillman).

^ Massachusetts Debates, supra note 16, at 71 (statement of Del. Lincoln Bryant); see also Nebraska Debates, supra note 16, at 539 (statement of Del. Jerry Howard) (“I am not going into Spain or Belgium . . . . I am remaining here at home in Nebraska.”).

^ New York Debates, supra note 16, at 1095 (statement of Del. Stephen S. Blake).

^ Nebraska Debates, supra note 16, at 539 (statement of Del. R.A. Matteson); see also id. at 538 (statement of Del. O.B. Spillman) (noting compulsory voting would “not be practical in its operation in this state”).