Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on June 19, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, history, etc.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organization?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography , action research , phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasize different aims and perspectives.

| Approach | What does it involve? |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | Researchers collect rich data on a topic of interest and develop theories . |

| Researchers immerse themselves in groups or organizations to understand their cultures. | |

| Action research | Researchers and participants collaboratively link theory to practice to drive social change. |

| Phenomenological research | Researchers investigate a phenomenon or event by describing and interpreting participants’ lived experiences. |

| Narrative research | Researchers examine how stories are told to understand how participants perceive and make sense of their experiences. |

Note that qualitative research is at risk for certain research biases including the Hawthorne effect , observer bias , recall bias , and social desirability bias . While not always totally avoidable, awareness of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data can prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

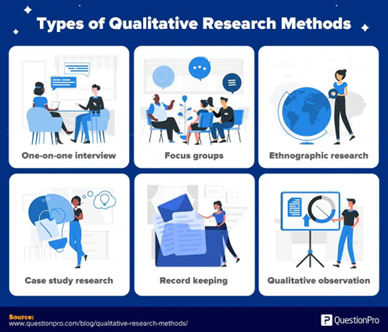

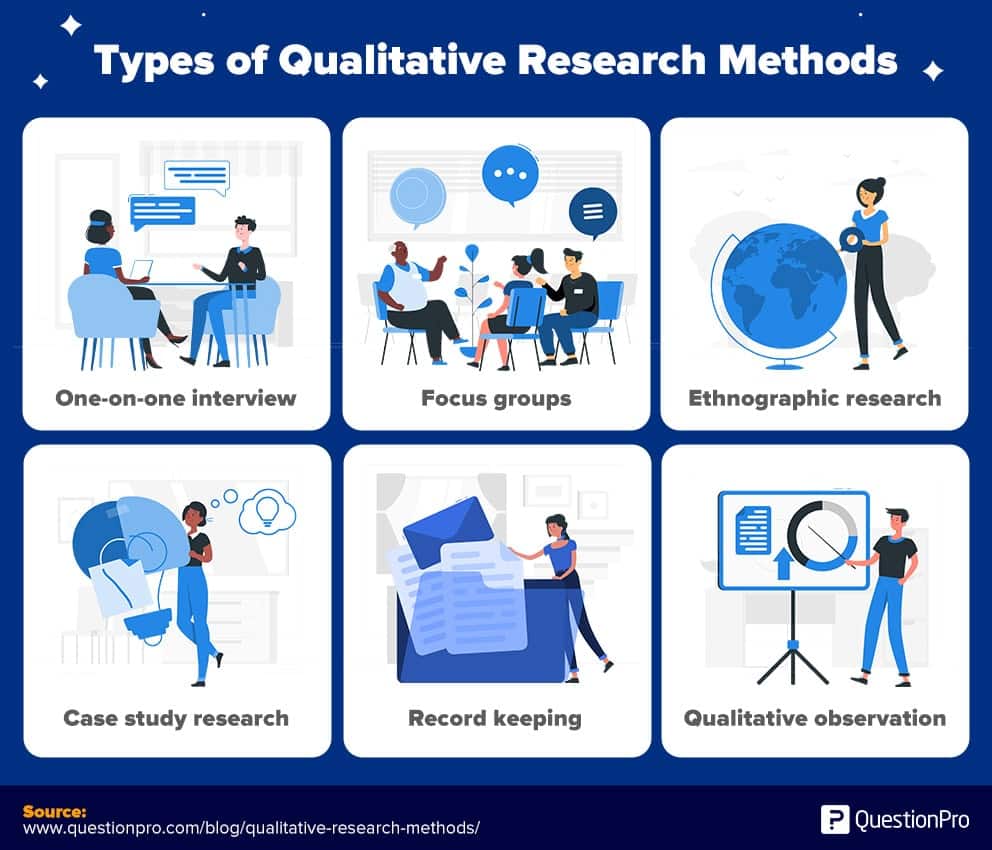

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves “instruments” in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analyzing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organize your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorize your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

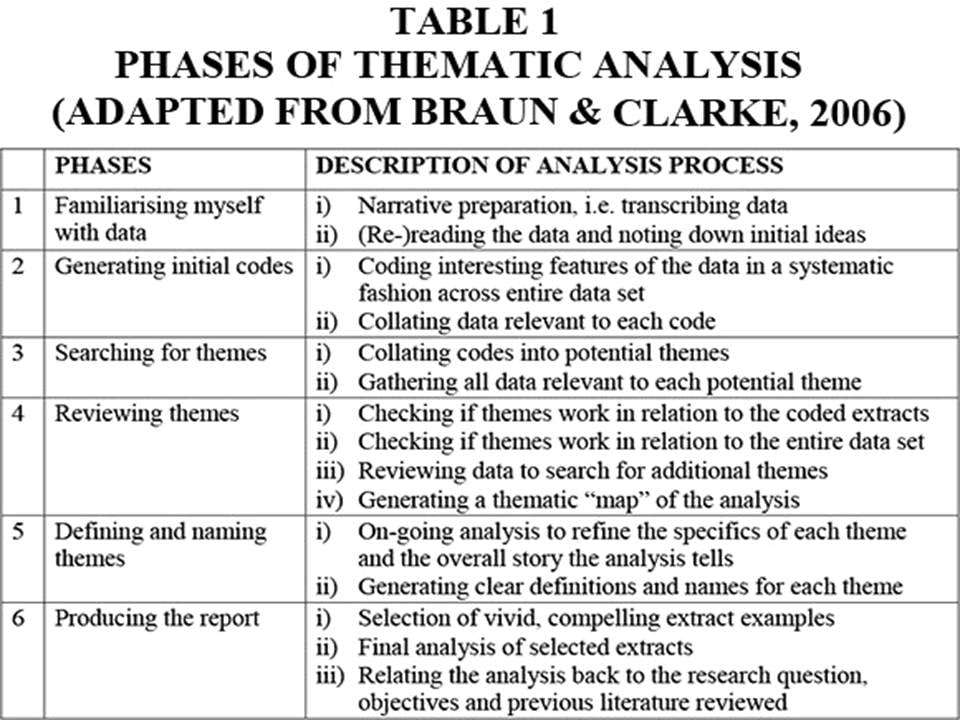

There are several specific approaches to analyzing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasize different concepts.

| Approach | When to use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| To describe and categorize common words, phrases, and ideas in qualitative data. | A market researcher could perform content analysis to find out what kind of language is used in descriptions of therapeutic apps. | |

| To identify and interpret patterns and themes in qualitative data. | A psychologist could apply thematic analysis to travel blogs to explore how tourism shapes self-identity. | |

| To examine the content, structure, and design of texts. | A media researcher could use textual analysis to understand how news coverage of celebrities has changed in the past decade. | |

| To study communication and how language is used to achieve effects in specific contexts. | A political scientist could use discourse analysis to study how politicians generate trust in election campaigns. |

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analyzing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analyzing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalizability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalizable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labor-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organization to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 21, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, how to do thematic analysis | step-by-step guide & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- How to Order

Research Paper Guide

Types Of Qualitative Research

8 Types of Qualitative Research - Overview & Examples

16 min read

People also read

Research Paper Writing - A Step by Step Guide

Research Paper Examples - Free Sample Papers for Different Formats!

Guide to Creating Effective Research Paper Outline

Interesting Research Paper Topics for 2024

Research Proposal Writing - A Step-by-Step Guide

How to Start a Research Paper - 7 Easy Steps

How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper - A Step by Step Guide

Writing a Literature Review For a Research Paper - A Comprehensive Guide

Qualitative Research - Methods, Types, and Examples

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research - Learning the Basics

200+ Engaging Psychology Research Paper Topics for Students in 2024

Learn How to Write a Hypothesis in a Research Paper: Examples and Tips!

20+ Types of Research With Examples - A Detailed Guide

Understanding Quantitative Research - Types & Data Collection Techniques

230+ Sociology Research Topics & Ideas for Students

How to Cite a Research Paper - A Complete Guide

Excellent History Research Paper Topics- 300+ Ideas

A Guide on Writing the Method Section of a Research Paper - Examples & Tips

How To Write an Introduction Paragraph For a Research Paper: Learn with Examples

Crafting a Winning Research Paper Title: A Complete Guide

Writing a Research Paper Conclusion - Step-by-Step Guide

Writing a Thesis For a Research Paper - A Comprehensive Guide

How To Write A Discussion For A Research Paper | Examples & Tips

How To Write The Results Section of A Research Paper | Steps & Examples

Writing a Problem Statement for a Research Paper - A Comprehensive Guide

Finding Sources For a Research Paper: A Complete Guide

A Guide on How to Edit a Research Paper

200+ Ethical Research Paper Topics to Begin With (2024)

300+ Controversial Research Paper Topics & Ideas - 2024 Edition

150+ Argumentative Research Paper Topics For You - 2024

How to Write a Research Methodology for a Research Paper

Are you overwhelmed by the multitude of qualitative research methods available? It's no secret that choosing the right approach can leave you stuck at the starting line of your research.

Selecting an unsuitable method can lead to wasted time, resources, and potentially skewed results. But with so many options to consider, it's easy to feel lost in the complexities of qualitative research.

In this comprehensive guide, we will explain the types of qualitative research, their unique characteristics, advantages, and best use cases for each method.

Let's dive in!

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

- 1. What is Qualitative Research?

- 2. Types of Qualitative Research Methods

- 3. Types of Data Analysis in Qualitative Research

What is Qualitative Research?

Qualitative research is a robust and flexible methodology used to explore and understand complex phenomena in-depth.

Unlike quantitative research , qualitative research dives into the rich and complex aspects of human experiences, behaviors, and perceptions.

At its core, this type of research question seek to answer for:

- Why do people think or behave a certain way?

- What are the underlying motivations and meanings behind actions?

- How do individuals perceive and interpret the world around them?

This approach values context, diversity, and the unique perspectives of participants.

Rather than seeking generalizable findings applicable to a broad population, qualitative research aims for detailed insights, patterns, and themes that come from the people being studied.

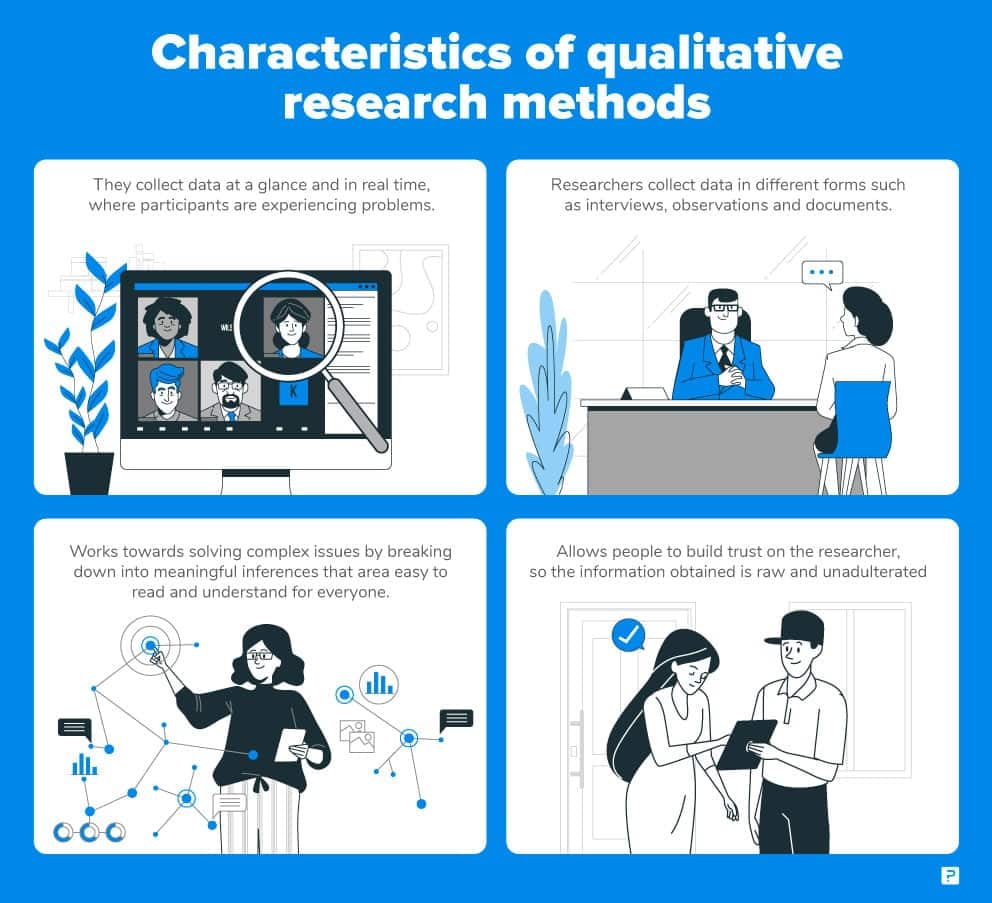

Characteristics of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research possesses the following characteristics:

- Subjective Perspective: Qualitative research explores subjective experiences, emphasizing the uniqueness of human behavior and opinions.

- In-Depth Exploration: It involves deep investigation, allowing a comprehensive understanding of specific phenomena.

- Open-Ended Questions: Qualitative research uses open-ended questions to encourage detailed, descriptive responses.

- Contextual Understanding: It emphasizes the importance of understanding the research context and setting.

- Rich Descriptions: Qualitative research produces rich, descriptive findings that contribute to a nuanced understanding of the topic.

Types of Qualitative Research Methods

Researchers collect data on the targeted population, place, or event by using different types of qualitative research analysis.

Each qualitative research method offers a distinct perspective, enabling researchers to reveal concealed meanings, patterns, and valuable insights.

Below are the most commonly used qualitative research types for writing a paper.

Ethnographic Research Method

| To describe and understand cultural characteristics within human societies. |

| Gathering existing knowledge and insights from academic and historical sources. Immersion in the environment where the target audience resides, living with and interacting with subjects. Data collection through extensive observation and direct engagement. |

| The analysis phase aims to describe the fundamental parameters of the culture under study. |

| Comprehensive descriptions of social norms, values, customs, and practices within the studied culture. |

Ethnography, a subfield of anthropology, provides a scientific approach to examining human societies and cultures. It ranks among the most widely employed qualitative research techniques.

In ethnographic field notes, researchers actively engage with the environment and live alongside the focus group.

This immersive interaction allows researchers to gain insights into the objectives, motivations, challenges, and distinctive cultural attributes of the individuals under study.

Key cultural characteristics that ethnography helps to illustrate encompass:

- Geographical Location

- Religious Practices

- Tribal Systems

- Shared Experiences

Unlike traditional survey and interview-based research methods, ethnographers don't rely on structured questioning.

Instead, they become observers within the community, emphasizing participant observation over an extended period. However, it may also be appropriate to complement observations with interviews of individuals who possess knowledge of the culture.

Ethnographic research can present challenges if the researcher is unfamiliar with the social norms and language of the group being studied.

Furthermore, interpretations made by outsiders may lead to misinterpretations or confusion. Therefore, thorough validation of data is essential before presenting findings.

An effective way to understand customer needs is by observing their daily activities and interactions with a product. This approach doesn't necessitate formulating hypotheses for testing but instead requires immersion in the subjects' social lives. |

Narrative Method

| Collect data in the form of a cohesive story. |

| Examining the sequence of events and conducting interviews to describe the significant influences that have shaped an individual's life. Analyzing various life situations and opportunities that have played a role in the individual's narrative. |

| Presenting a short narrative that includes themes, conflicts, and challenges. |

The narrative research design unfolds over an extended period to compile data, much like crafting a cohesive story. Similar to a narrative structure, it begins with a starting point and progresses through various life situations.

In this method, researchers engage in in-depth interviews and review relevant documents. They explore events that have had a significant impact on an individual's personality and life journey. Interviews may occur over weeks, months, or even years, depending on the depth and scope of the narrative being studied.

The outcome of narrative research is the presentation of a concise story that captures essential themes, conflicts, and challenges. It provides a holistic view of the individual's experiences, both positive and negative, which have shaped their unique narrative.

The narrative method finds practical application in the business world. It can help in understanding the diverse challenges faced by a target audience. Moreover, it can be leveraged to foster innovation and guide the development of products and solutions that resonate with the audience's narrative. |

Phenomenological Method

| To describe experiences, events, or situations from various perspectives. |

| Collecting data through interviews, observations, surveys, and document analysis. Articulating the experiences related to the phenomenon under study. |

| Classifying data and exploring experiences beyond conscious awareness. |

| Creation of a database that presents findings from the subject's viewpoint. |

The term "phenomenological" pertains to the study of phenomena, which can encompass events, situations, or experiences.

This method is ideal for examining a subject from multiple perspectives and contributing to existing knowledge, with a particular focus on subjective experiences.

Researchers employing the phenomenological method use various data collection techniques, including interviews, site visits, observations, surveys, and document reviews.

These methods help gather rich and diverse data about the phenomenon under investigation.

A central aspect of this technique is capturing how participants experience events or activities, delving into their subjective viewpoints. Ultimately, the research results in the creation of a thematic database that validates the findings and offers insights from the subject's perspective.

The phenomenological research method is valuable for understanding why students are increasingly opting for online courses. It allows researchers to explore the reasons behind this trend from the subjective experiences of students, providing valuable insights into their motivations and preferences. |

Grounded Theory Method

| To develop theories, identify social developments, and understand ways to address them. |

| Gathering data through interviews, observations, literature reviews, and document analysis. Developing theories through a systematic process of data collection, coding, and theory formation. |

| The development of theories is supported by relevant examples drawn from the collected data. |

A grounded theory approach differs from a phenomenological study in that it seeks to explain, provide reasons for, or develop theories behind an event or phenomenon.

It serves as a means to construct new theories by systematically collecting and analyzing data related to a specific phenomenon.

Researchers employing the grounded theory method utilize a variety of data collection techniques, including observation, interviews, literature review , and the analysis of relevant documents.

The focus of content analysis is not individual behaviors but a specific phenomenon or incident.

This method typically involves various coding techniques and large sample sizes to identify themes and develop more comprehensive theories.

Businesses can employ this method to conduct surveys and gain insight into why consumers choose their products or services. The data collected through such surveys can aid companies in enhancing and maintaining customer satisfaction and loyalty. |

Case Study Research

| To provide a detailed description of an experience, person, event, or place. |

| Gaining a deep understanding of the subject through firsthand experiences and engagement. |

| Analyzing the experiences and insights gained from the case study. |

| Delivering an in-depth and comprehensive description of the subject under study. |

The case study approach entails a comprehensive examination of a subject over an extended period, with a focus on providing detailed insights into the subject, which can be an event, person, business, or place.

Data for case studies is collected from diverse sources, including interviews, direct observation, historical records, and documentation.

Case studies find applications across various disciplines, including law, education, medicine, and the sciences. They can serve both descriptive and explanatory purposes, making them a versatile research methodology .

Researchers often turn to the case study method when they want to explore:

- 'How' and 'why' research questions

- Behaviors under observation

- Understanding a specific phenomenon

- The contextual factors influencing the phenomena

Businesses can effectively showcase their solutions and problem-solving capabilities through case studies. Let's consider a scenario where Company AB introduces new UX designs in an agile environment. This case study can offer valuable insights for other companies seeking similar enhancements. |

Historical Method

| To describe and examine past events for a better understanding of present patterns and the ability to predict future scenarios. |

| |

| Analyzing the collected data by assessing its credibility and considering conflicting evidence. |

| Presenting the research findings in the form of a biography or scholarly paper. |

The historical method aims to describe and analyze past events, offering insights into present patterns and the potential to predict future scenarios.

Researchers formulate research questions based on a hypothetical idea and then rigorously test this idea using multiple historical resources.

Key steps in the historical method include:

- Developing a research idea

- Identifying appropriate sources such as archives and libraries

- Ensuring the reliability and validity of these sources

- Creating a well-organized research outline

- Systematically collecting research data

The analysis phase involves critically assessing the collected data, accepting or rejecting it based on credibility, and identifying any conflicting evidence.

Ultimately, the outcomes of the historical method are presented in the form of a biography or a scholarly paper that provides a comprehensive account of the research findings.

Businesses can harness the historical method by examining past ad campaigns and the demographics they target. This historical data can inform the creation of new ads and help tailor qualitative market research strategies for better outcomes. |

Action Research

| To improve and address practical issues, problems, or challenges in real-world settings by taking action and conducting research simultaneously. |

| |

| The outcomes of action research include practical solutions, improved practices, and enhanced understanding of the issue. |

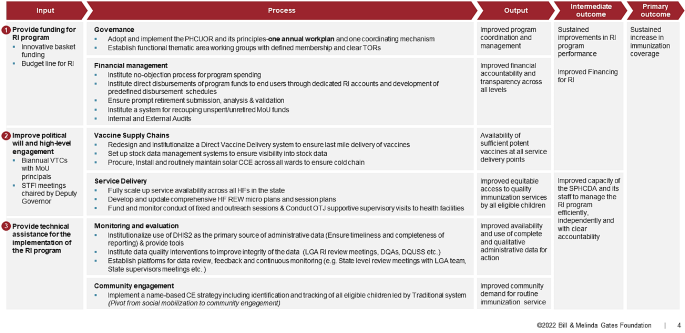

Action research is a dynamic research approach focused on addressing practical challenges in real-world settings while simultaneously conducting research to improve the situation.

It follows a cyclic process, starting with the identification of a specific issue or problem in a particular context.

The key steps in action research include:

- Planning and implementing actions to address the issue

- Collecting data during the action phase to understand its impact

- Reflecting on the data and analyzing it to gain insights

- Adjusting the action plan based on the analysis

This process may be iterative, with multiple cycles of action and reflection.

The outcomes of action research are practical solutions and improved practices that directly benefit the context in which the research is conducted. Additionally, it leads to a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the issue under investigation.

In education, action research can be used by teachers to identify and address classroom challenges. For instance, a teacher may recognize that a particular teaching method is not effectively engaging students. Through action research, the teacher can develop and implement new teaching strategies, collect data on their effectiveness, analyze the results, and refine the teaching approach to enhance student learning outcomes. |

Focus Groups

| To gather qualitative data by engaging a small group of participants in a structured discussion on a specific topic or research question. |

| |

| Analyzing the data collected from the focus group discussion to identify themes, patterns, and insights. |

| The outcomes of focus groups include rich qualitative data that provide a deeper understanding of the research topic or question. |

Focus groups are a qualitative research method used to gather in-depth insights and perspectives on a specific topic or research question.

This approach involves assembling a small group of participants who possess relevant knowledge or experiences related to the research focus.

Key steps in the focus group method include:

- Selecting participants

- Moderating the discussion

- Structuring the conversation around open-ended questions

- Collecting data through audio or video recordings and note-taking

The discussion is dynamic and interactive, encouraging participants to share their thoughts, experiences, and opinions.

The analysis phase involves reviewing the data collected from the focus group discussion to identify common themes, patterns, and valuable insights. Focus groups provide rich qualitative data that offer a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the research topic or question.

In the development of a new mobile app, a focus group can be organized with potential users to gather feedback on user interface design and functionality. Participants in the focus group can share their preferences, concerns, and suggestions, providing valuable input to improve the app's usability and appeal. |

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

Types of Data Analysis in Qualitative Research

Qualitative research employs different data analysis methods, each suited to specific research goals:

- Thematic Analysis: Identifies recurring themes or concepts within data.

- Content Analysis: Systematically categorizes and quantifies text or media content.

- Narrative Analysis: Focuses on storytelling and narrative elements in data.

- Grounded Theory Analysis: Develops or refines theories based on data.

- Discourse Analysis: Examines language and communication patterns.

- Framework Analysis: Organizes data using predefined categories.

- Visual Analysis: Interprets visual data like photos or videos.

- Cross-case Analysis: Compares patterns across multiple cases.

The choice depends on research questions and data type, enhancing understanding and insights.

Benefits of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research offers valuable advantages, including:

- Flexibility: Adaptable to various research questions and settings.

- Holistic Approach: Explores multiple dimensions of phenomena.

- Theory Development: Contributes to theory creation or refinement.

- Participant Engagement: Fosters active participant involvement.

- Complements Quantitative Research: Provides a comprehensive understanding.

All in all, different types of qualitative research methodology can assist in understanding the behavior and motivations of people. Similarly, it will also help in generating original ideas and formulating a better research problem.

However, not everyone can write a good research paper. Thus, if you get stuck at any stage, you can get professional help.

MyPerfectWords.com is the best paper writing service, where you can hire a professional writer for all your ' do my essay ' requests.

We assure you that you will receive high-quality paper at the most reasonable rates.

Contact our team with your " pay for my research paper " queries. We are available 24/7!

Write Essay Within 60 Seconds!

Nova Allison is a Digital Content Strategist with over eight years of experience. Nova has also worked as a technical and scientific writer. She is majorly involved in developing and reviewing online content plans that engage and resonate with audiences. Nova has a passion for writing that engages and informs her readers.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That’s our Job!

Keep reading

Chapter 1. Introduction

“Science is in danger, and for that reason it is becoming dangerous” -Pierre Bourdieu, Science of Science and Reflexivity

Why an Open Access Textbook on Qualitative Research Methods?

I have been teaching qualitative research methods to both undergraduates and graduate students for many years. Although there are some excellent textbooks out there, they are often costly, and none of them, to my mind, properly introduces qualitative research methods to the beginning student (whether undergraduate or graduate student). In contrast, this open-access textbook is designed as a (free) true introduction to the subject, with helpful, practical pointers on how to conduct research and how to access more advanced instruction.

Textbooks are typically arranged in one of two ways: (1) by technique (each chapter covers one method used in qualitative research); or (2) by process (chapters advance from research design through publication). But both of these approaches are necessary for the beginner student. This textbook will have sections dedicated to the process as well as the techniques of qualitative research. This is a true “comprehensive” book for the beginning student. In addition to covering techniques of data collection and data analysis, it provides a road map of how to get started and how to keep going and where to go for advanced instruction. It covers aspects of research design and research communication as well as methods employed. Along the way, it includes examples from many different disciplines in the social sciences.

The primary goal has been to create a useful, accessible, engaging textbook for use across many disciplines. And, let’s face it. Textbooks can be boring. I hope readers find this to be a little different. I have tried to write in a practical and forthright manner, with many lively examples and references to good and intellectually creative qualitative research. Woven throughout the text are short textual asides (in colored textboxes) by professional (academic) qualitative researchers in various disciplines. These short accounts by practitioners should help inspire students. So, let’s begin!

What is Research?

When we use the word research , what exactly do we mean by that? This is one of those words that everyone thinks they understand, but it is worth beginning this textbook with a short explanation. We use the term to refer to “empirical research,” which is actually a historically specific approach to understanding the world around us. Think about how you know things about the world. [1] You might know your mother loves you because she’s told you she does. Or because that is what “mothers” do by tradition. Or you might know because you’ve looked for evidence that she does, like taking care of you when you are sick or reading to you in bed or working two jobs so you can have the things you need to do OK in life. Maybe it seems churlish to look for evidence; you just take it “on faith” that you are loved.

Only one of the above comes close to what we mean by research. Empirical research is research (investigation) based on evidence. Conclusions can then be drawn from observable data. This observable data can also be “tested” or checked. If the data cannot be tested, that is a good indication that we are not doing research. Note that we can never “prove” conclusively, through observable data, that our mothers love us. We might have some “disconfirming evidence” (that time she didn’t show up to your graduation, for example) that could push you to question an original hypothesis , but no amount of “confirming evidence” will ever allow us to say with 100% certainty, “my mother loves me.” Faith and tradition and authority work differently. Our knowledge can be 100% certain using each of those alternative methods of knowledge, but our certainty in those cases will not be based on facts or evidence.

For many periods of history, those in power have been nervous about “science” because it uses evidence and facts as the primary source of understanding the world, and facts can be at odds with what power or authority or tradition want you to believe. That is why I say that scientific empirical research is a historically specific approach to understand the world. You are in college or university now partly to learn how to engage in this historically specific approach.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Europe, there was a newfound respect for empirical research, some of which was seriously challenging to the established church. Using observations and testing them, scientists found that the earth was not at the center of the universe, for example, but rather that it was but one planet of many which circled the sun. [2] For the next two centuries, the science of astronomy, physics, biology, and chemistry emerged and became disciplines taught in universities. All used the scientific method of observation and testing to advance knowledge. Knowledge about people , however, and social institutions, however, was still left to faith, tradition, and authority. Historians and philosophers and poets wrote about the human condition, but none of them used research to do so. [3]

It was not until the nineteenth century that “social science” really emerged, using the scientific method (empirical observation) to understand people and social institutions. New fields of sociology, economics, political science, and anthropology emerged. The first sociologists, people like Auguste Comte and Karl Marx, sought specifically to apply the scientific method of research to understand society, Engels famously claiming that Marx had done for the social world what Darwin did for the natural world, tracings its laws of development. Today we tend to take for granted the naturalness of science here, but it is actually a pretty recent and radical development.

To return to the question, “does your mother love you?” Well, this is actually not really how a researcher would frame the question, as it is too specific to your case. It doesn’t tell us much about the world at large, even if it does tell us something about you and your relationship with your mother. A social science researcher might ask, “do mothers love their children?” Or maybe they would be more interested in how this loving relationship might change over time (e.g., “do mothers love their children more now than they did in the 18th century when so many children died before reaching adulthood?”) or perhaps they might be interested in measuring quality of love across cultures or time periods, or even establishing “what love looks like” using the mother/child relationship as a site of exploration. All of these make good research questions because we can use observable data to answer them.

What is Qualitative Research?

“All we know is how to learn. How to study, how to listen, how to talk, how to tell. If we don’t tell the world, we don’t know the world. We’re lost in it, we die.” -Ursula LeGuin, The Telling

At its simplest, qualitative research is research about the social world that does not use numbers in its analyses. All those who fear statistics can breathe a sigh of relief – there are no mathematical formulae or regression models in this book! But this definition is less about what qualitative research can be and more about what it is not. To be honest, any simple statement will fail to capture the power and depth of qualitative research. One way of contrasting qualitative research to quantitative research is to note that the focus of qualitative research is less about explaining and predicting relationships between variables and more about understanding the social world. To use our mother love example, the question about “what love looks like” is a good question for the qualitative researcher while all questions measuring love or comparing incidences of love (both of which require measurement) are good questions for quantitative researchers. Patton writes,

Qualitative data describe. They take us, as readers, into the time and place of the observation so that we know what it was like to have been there. They capture and communicate someone else’s experience of the world in his or her own words. Qualitative data tell a story. ( Patton 2002:47 )

Qualitative researchers are asking different questions about the world than their quantitative colleagues. Even when researchers are employed in “mixed methods” research ( both quantitative and qualitative), they are using different methods to address different questions of the study. I do a lot of research about first-generation and working-college college students. Where a quantitative researcher might ask, how many first-generation college students graduate from college within four years? Or does first-generation college status predict high student debt loads? A qualitative researcher might ask, how does the college experience differ for first-generation college students? What is it like to carry a lot of debt, and how does this impact the ability to complete college on time? Both sets of questions are important, but they can only be answered using specific tools tailored to those questions. For the former, you need large numbers to make adequate comparisons. For the latter, you need to talk to people, find out what they are thinking and feeling, and try to inhabit their shoes for a little while so you can make sense of their experiences and beliefs.

Examples of Qualitative Research

You have probably seen examples of qualitative research before, but you might not have paid particular attention to how they were produced or realized that the accounts you were reading were the result of hours, months, even years of research “in the field.” A good qualitative researcher will present the product of their hours of work in such a way that it seems natural, even obvious, to the reader. Because we are trying to convey what it is like answers, qualitative research is often presented as stories – stories about how people live their lives, go to work, raise their children, interact with one another. In some ways, this can seem like reading particularly insightful novels. But, unlike novels, there are very specific rules and guidelines that qualitative researchers follow to ensure that the “story” they are telling is accurate , a truthful rendition of what life is like for the people being studied. Most of this textbook will be spent conveying those rules and guidelines. Let’s take a look, first, however, at three examples of what the end product looks like. I have chosen these three examples to showcase very different approaches to qualitative research, and I will return to these five examples throughout the book. They were all published as whole books (not chapters or articles), and they are worth the long read, if you have the time. I will also provide some information on how these books came to be and the length of time it takes to get them into book version. It is important you know about this process, and the rest of this textbook will help explain why it takes so long to conduct good qualitative research!

Example 1 : The End Game (ethnography + interviews)

Corey Abramson is a sociologist who teaches at the University of Arizona. In 2015 he published The End Game: How Inequality Shapes our Final Years ( 2015 ). This book was based on the research he did for his dissertation at the University of California-Berkeley in 2012. Actually, the dissertation was completed in 2012 but the work that was produced that took several years. The dissertation was entitled, “This is How We Live, This is How We Die: Social Stratification, Aging, and Health in Urban America” ( 2012 ). You can see how the book version, which was written for a more general audience, has a more engaging sound to it, but that the dissertation version, which is what academic faculty read and evaluate, has a more descriptive title. You can read the title and know that this is a study about aging and health and that the focus is going to be inequality and that the context (place) is going to be “urban America.” It’s a study about “how” people do something – in this case, how they deal with aging and death. This is the very first sentence of the dissertation, “From our first breath in the hospital to the day we die, we live in a society characterized by unequal opportunities for maintaining health and taking care of ourselves when ill. These disparities reflect persistent racial, socio-economic, and gender-based inequalities and contribute to their persistence over time” ( 1 ). What follows is a truthful account of how that is so.

Cory Abramson spent three years conducting his research in four different urban neighborhoods. We call the type of research he conducted “comparative ethnographic” because he designed his study to compare groups of seniors as they went about their everyday business. It’s comparative because he is comparing different groups (based on race, class, gender) and ethnographic because he is studying the culture/way of life of a group. [4] He had an educated guess, rooted in what previous research had shown and what social theory would suggest, that people’s experiences of aging differ by race, class, and gender. So, he set up a research design that would allow him to observe differences. He chose two primarily middle-class (one was racially diverse and the other was predominantly White) and two primarily poor neighborhoods (one was racially diverse and the other was predominantly African American). He hung out in senior centers and other places seniors congregated, watched them as they took the bus to get prescriptions filled, sat in doctor’s offices with them, and listened to their conversations with each other. He also conducted more formal conversations, what we call in-depth interviews, with sixty seniors from each of the four neighborhoods. As with a lot of fieldwork , as he got closer to the people involved, he both expanded and deepened his reach –

By the end of the project, I expanded my pool of general observations to include various settings frequented by seniors: apartment building common rooms, doctors’ offices, emergency rooms, pharmacies, senior centers, bars, parks, corner stores, shopping centers, pool halls, hair salons, coffee shops, and discount stores. Over the course of the three years of fieldwork, I observed hundreds of elders, and developed close relationships with a number of them. ( 2012:10 )

When Abramson rewrote the dissertation for a general audience and published his book in 2015, it got a lot of attention. It is a beautifully written book and it provided insight into a common human experience that we surprisingly know very little about. It won the Outstanding Publication Award by the American Sociological Association Section on Aging and the Life Course and was featured in the New York Times . The book was about aging, and specifically how inequality shapes the aging process, but it was also about much more than that. It helped show how inequality affects people’s everyday lives. For example, by observing the difficulties the poor had in setting up appointments and getting to them using public transportation and then being made to wait to see a doctor, sometimes in standing-room-only situations, when they are unwell, and then being treated dismissively by hospital staff, Abramson allowed readers to feel the material reality of being poor in the US. Comparing these examples with seniors with adequate supplemental insurance who have the resources to hire car services or have others assist them in arranging care when they need it, jolts the reader to understand and appreciate the difference money makes in the lives and circumstances of us all, and in a way that is different than simply reading a statistic (“80% of the poor do not keep regular doctor’s appointments”) does. Qualitative research can reach into spaces and places that often go unexamined and then reports back to the rest of us what it is like in those spaces and places.

Example 2: Racing for Innocence (Interviews + Content Analysis + Fictional Stories)

Jennifer Pierce is a Professor of American Studies at the University of Minnesota. Trained as a sociologist, she has written a number of books about gender, race, and power. Her very first book, Gender Trials: Emotional Lives in Contemporary Law Firms, published in 1995, is a brilliant look at gender dynamics within two law firms. Pierce was a participant observer, working as a paralegal, and she observed how female lawyers and female paralegals struggled to obtain parity with their male colleagues.

Fifteen years later, she reexamined the context of the law firm to include an examination of racial dynamics, particularly how elite white men working in these spaces created and maintained a culture that made it difficult for both female attorneys and attorneys of color to thrive. Her book, Racing for Innocence: Whiteness, Gender, and the Backlash Against Affirmative Action , published in 2012, is an interesting and creative blending of interviews with attorneys, content analyses of popular films during this period, and fictional accounts of racial discrimination and sexual harassment. The law firm she chose to study had come under an affirmative action order and was in the process of implementing equitable policies and programs. She wanted to understand how recipients of white privilege (the elite white male attorneys) come to deny the role they play in reproducing inequality. Through interviews with attorneys who were present both before and during the affirmative action order, she creates a historical record of the “bad behavior” that necessitated new policies and procedures, but also, and more importantly , probed the participants ’ understanding of this behavior. It should come as no surprise that most (but not all) of the white male attorneys saw little need for change, and that almost everyone else had accounts that were different if not sometimes downright harrowing.

I’ve used Pierce’s book in my qualitative research methods courses as an example of an interesting blend of techniques and presentation styles. My students often have a very difficult time with the fictional accounts she includes. But they serve an important communicative purpose here. They are her attempts at presenting “both sides” to an objective reality – something happens (Pierce writes this something so it is very clear what it is), and the two participants to the thing that happened have very different understandings of what this means. By including these stories, Pierce presents one of her key findings – people remember things differently and these different memories tend to support their own ideological positions. I wonder what Pierce would have written had she studied the murder of George Floyd or the storming of the US Capitol on January 6 or any number of other historic events whose observers and participants record very different happenings.

This is not to say that qualitative researchers write fictional accounts. In fact, the use of fiction in our work remains controversial. When used, it must be clearly identified as a presentation device, as Pierce did. I include Racing for Innocence here as an example of the multiple uses of methods and techniques and the way that these work together to produce better understandings by us, the readers, of what Pierce studied. We readers come away with a better grasp of how and why advantaged people understate their own involvement in situations and structures that advantage them. This is normal human behavior , in other words. This case may have been about elite white men in law firms, but the general insights here can be transposed to other settings. Indeed, Pierce argues that more research needs to be done about the role elites play in the reproduction of inequality in the workplace in general.

Example 3: Amplified Advantage (Mixed Methods: Survey Interviews + Focus Groups + Archives)

The final example comes from my own work with college students, particularly the ways in which class background affects the experience of college and outcomes for graduates. I include it here as an example of mixed methods, and for the use of supplementary archival research. I’ve done a lot of research over the years on first-generation, low-income, and working-class college students. I am curious (and skeptical) about the possibility of social mobility today, particularly with the rising cost of college and growing inequality in general. As one of the few people in my family to go to college, I didn’t grow up with a lot of examples of what college was like or how to make the most of it. And when I entered graduate school, I realized with dismay that there were very few people like me there. I worried about becoming too different from my family and friends back home. And I wasn’t at all sure that I would ever be able to pay back the huge load of debt I was taking on. And so I wrote my dissertation and first two books about working-class college students. These books focused on experiences in college and the difficulties of navigating between family and school ( Hurst 2010a, 2012 ). But even after all that research, I kept coming back to wondering if working-class students who made it through college had an equal chance at finding good jobs and happy lives,

What happens to students after college? Do working-class students fare as well as their peers? I knew from my own experience that barriers continued through graduate school and beyond, and that my debtload was higher than that of my peers, constraining some of the choices I made when I graduated. To answer these questions, I designed a study of students attending small liberal arts colleges, the type of college that tried to equalize the experience of students by requiring all students to live on campus and offering small classes with lots of interaction with faculty. These private colleges tend to have more money and resources so they can provide financial aid to low-income students. They also attract some very wealthy students. Because they enroll students across the class spectrum, I would be able to draw comparisons. I ended up spending about four years collecting data, both a survey of more than 2000 students (which formed the basis for quantitative analyses) and qualitative data collection (interviews, focus groups, archival research, and participant observation). This is what we call a “mixed methods” approach because we use both quantitative and qualitative data. The survey gave me a large enough number of students that I could make comparisons of the how many kind, and to be able to say with some authority that there were in fact significant differences in experience and outcome by class (e.g., wealthier students earned more money and had little debt; working-class students often found jobs that were not in their chosen careers and were very affected by debt, upper-middle-class students were more likely to go to graduate school). But the survey analyses could not explain why these differences existed. For that, I needed to talk to people and ask them about their motivations and aspirations. I needed to understand their perceptions of the world, and it is very hard to do this through a survey.

By interviewing students and recent graduates, I was able to discern particular patterns and pathways through college and beyond. Specifically, I identified three versions of gameplay. Upper-middle-class students, whose parents were themselves professionals (academics, lawyers, managers of non-profits), saw college as the first stage of their education and took classes and declared majors that would prepare them for graduate school. They also spent a lot of time building their resumes, taking advantage of opportunities to help professors with their research, or study abroad. This helped them gain admission to highly-ranked graduate schools and interesting jobs in the public sector. In contrast, upper-class students, whose parents were wealthy and more likely to be engaged in business (as CEOs or other high-level directors), prioritized building social capital. They did this by joining fraternities and sororities and playing club sports. This helped them when they graduated as they called on friends and parents of friends to find them well-paying jobs. Finally, low-income, first-generation, and working-class students were often adrift. They took the classes that were recommended to them but without the knowledge of how to connect them to life beyond college. They spent time working and studying rather than partying or building their resumes. All three sets of students thought they were “doing college” the right way, the way that one was supposed to do college. But these three versions of gameplay led to distinct outcomes that advantaged some students over others. I titled my work “Amplified Advantage” to highlight this process.

These three examples, Cory Abramson’s The End Game , Jennifer Peirce’s Racing for Innocence, and my own Amplified Advantage, demonstrate the range of approaches and tools available to the qualitative researcher. They also help explain why qualitative research is so important. Numbers can tell us some things about the world, but they cannot get at the hearts and minds, motivations and beliefs of the people who make up the social worlds we inhabit. For that, we need tools that allow us to listen and make sense of what people tell us and show us. That is what good qualitative research offers us.

How Is This Book Organized?

This textbook is organized as a comprehensive introduction to the use of qualitative research methods. The first half covers general topics (e.g., approaches to qualitative research, ethics) and research design (necessary steps for building a successful qualitative research study). The second half reviews various data collection and data analysis techniques. Of course, building a successful qualitative research study requires some knowledge of data collection and data analysis so the chapters in the first half and the chapters in the second half should be read in conversation with each other. That said, each chapter can be read on its own for assistance with a particular narrow topic. In addition to the chapters, a helpful glossary can be found in the back of the book. Rummage around in the text as needed.

Chapter Descriptions

Chapter 2 provides an overview of the Research Design Process. How does one begin a study? What is an appropriate research question? How is the study to be done – with what methods ? Involving what people and sites? Although qualitative research studies can and often do change and develop over the course of data collection, it is important to have a good idea of what the aims and goals of your study are at the outset and a good plan of how to achieve those aims and goals. Chapter 2 provides a road map of the process.

Chapter 3 describes and explains various ways of knowing the (social) world. What is it possible for us to know about how other people think or why they behave the way they do? What does it mean to say something is a “fact” or that it is “well-known” and understood? Qualitative researchers are particularly interested in these questions because of the types of research questions we are interested in answering (the how questions rather than the how many questions of quantitative research). Qualitative researchers have adopted various epistemological approaches. Chapter 3 will explore these approaches, highlighting interpretivist approaches that acknowledge the subjective aspect of reality – in other words, reality and knowledge are not objective but rather influenced by (interpreted through) people.

Chapter 4 focuses on the practical matter of developing a research question and finding the right approach to data collection. In any given study (think of Cory Abramson’s study of aging, for example), there may be years of collected data, thousands of observations , hundreds of pages of notes to read and review and make sense of. If all you had was a general interest area (“aging”), it would be very difficult, nearly impossible, to make sense of all of that data. The research question provides a helpful lens to refine and clarify (and simplify) everything you find and collect. For that reason, it is important to pull out that lens (articulate the research question) before you get started. In the case of the aging study, Cory Abramson was interested in how inequalities affected understandings and responses to aging. It is for this reason he designed a study that would allow him to compare different groups of seniors (some middle-class, some poor). Inevitably, he saw much more in the three years in the field than what made it into his book (or dissertation), but he was able to narrow down the complexity of the social world to provide us with this rich account linked to the original research question. Developing a good research question is thus crucial to effective design and a successful outcome. Chapter 4 will provide pointers on how to do this. Chapter 4 also provides an overview of general approaches taken to doing qualitative research and various “traditions of inquiry.”

Chapter 5 explores sampling . After you have developed a research question and have a general idea of how you will collect data (Observations? Interviews?), how do you go about actually finding people and sites to study? Although there is no “correct number” of people to interview , the sample should follow the research question and research design. Unlike quantitative research, qualitative research involves nonprobability sampling. Chapter 5 explains why this is so and what qualities instead make a good sample for qualitative research.

Chapter 6 addresses the importance of reflexivity in qualitative research. Related to epistemological issues of how we know anything about the social world, qualitative researchers understand that we the researchers can never be truly neutral or outside the study we are conducting. As observers, we see things that make sense to us and may entirely miss what is either too obvious to note or too different to comprehend. As interviewers, as much as we would like to ask questions neutrally and remain in the background, interviews are a form of conversation, and the persons we interview are responding to us . Therefore, it is important to reflect upon our social positions and the knowledges and expectations we bring to our work and to work through any blind spots that we may have. Chapter 6 provides some examples of reflexivity in practice and exercises for thinking through one’s own biases.

Chapter 7 is a very important chapter and should not be overlooked. As a practical matter, it should also be read closely with chapters 6 and 8. Because qualitative researchers deal with people and the social world, it is imperative they develop and adhere to a strong ethical code for conducting research in a way that does not harm. There are legal requirements and guidelines for doing so (see chapter 8), but these requirements should not be considered synonymous with the ethical code required of us. Each researcher must constantly interrogate every aspect of their research, from research question to design to sample through analysis and presentation, to ensure that a minimum of harm (ideally, zero harm) is caused. Because each research project is unique, the standards of care for each study are unique. Part of being a professional researcher is carrying this code in one’s heart, being constantly attentive to what is required under particular circumstances. Chapter 7 provides various research scenarios and asks readers to weigh in on the suitability and appropriateness of the research. If done in a class setting, it will become obvious fairly quickly that there are often no absolutely correct answers, as different people find different aspects of the scenarios of greatest importance. Minimizing the harm in one area may require possible harm in another. Being attentive to all the ethical aspects of one’s research and making the best judgments one can, clearly and consciously, is an integral part of being a good researcher.

Chapter 8 , best to be read in conjunction with chapter 7, explains the role and importance of Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) . Under federal guidelines, an IRB is an appropriately constituted group that has been formally designated to review and monitor research involving human subjects . Every institution that receives funding from the federal government has an IRB. IRBs have the authority to approve, require modifications to (to secure approval), or disapprove research. This group review serves an important role in the protection of the rights and welfare of human research subjects. Chapter 8 reviews the history of IRBs and the work they do but also argues that IRBs’ review of qualitative research is often both over-inclusive and under-inclusive. Some aspects of qualitative research are not well understood by IRBs, given that they were developed to prevent abuses in biomedical research. Thus, it is important not to rely on IRBs to identify all the potential ethical issues that emerge in our research (see chapter 7).

Chapter 9 provides help for getting started on formulating a research question based on gaps in the pre-existing literature. Research is conducted as part of a community, even if particular studies are done by single individuals (or small teams). What any of us finds and reports back becomes part of a much larger body of knowledge. Thus, it is important that we look at the larger body of knowledge before we actually start our bit to see how we can best contribute. When I first began interviewing working-class college students, there was only one other similar study I could find, and it hadn’t been published (it was a dissertation of students from poor backgrounds). But there had been a lot published by professors who had grown up working class and made it through college despite the odds. These accounts by “working-class academics” became an important inspiration for my study and helped me frame the questions I asked the students I interviewed. Chapter 9 will provide some pointers on how to search for relevant literature and how to use this to refine your research question.

Chapter 10 serves as a bridge between the two parts of the textbook, by introducing techniques of data collection. Qualitative research is often characterized by the form of data collection – for example, an ethnographic study is one that employs primarily observational data collection for the purpose of documenting and presenting a particular culture or ethnos. Techniques can be effectively combined, depending on the research question and the aims and goals of the study. Chapter 10 provides a general overview of all the various techniques and how they can be combined.

The second part of the textbook moves into the doing part of qualitative research once the research question has been articulated and the study designed. Chapters 11 through 17 cover various data collection techniques and approaches. Chapters 18 and 19 provide a very simple overview of basic data analysis. Chapter 20 covers communication of the data to various audiences, and in various formats.

Chapter 11 begins our overview of data collection techniques with a focus on interviewing , the true heart of qualitative research. This technique can serve as the primary and exclusive form of data collection, or it can be used to supplement other forms (observation, archival). An interview is distinct from a survey, where questions are asked in a specific order and often with a range of predetermined responses available. Interviews can be conversational and unstructured or, more conventionally, semistructured , where a general set of interview questions “guides” the conversation. Chapter 11 covers the basics of interviews: how to create interview guides, how many people to interview, where to conduct the interview, what to watch out for (how to prepare against things going wrong), and how to get the most out of your interviews.

Chapter 12 covers an important variant of interviewing, the focus group. Focus groups are semistructured interviews with a group of people moderated by a facilitator (the researcher or researcher’s assistant). Focus groups explicitly use group interaction to assist in the data collection. They are best used to collect data on a specific topic that is non-personal and shared among the group. For example, asking a group of college students about a common experience such as taking classes by remote delivery during the pandemic year of 2020. Chapter 12 covers the basics of focus groups: when to use them, how to create interview guides for them, and how to run them effectively.

Chapter 13 moves away from interviewing to the second major form of data collection unique to qualitative researchers – observation . Qualitative research that employs observation can best be understood as falling on a continuum of “fly on the wall” observation (e.g., observing how strangers interact in a doctor’s waiting room) to “participant” observation, where the researcher is also an active participant of the activity being observed. For example, an activist in the Black Lives Matter movement might want to study the movement, using her inside position to gain access to observe key meetings and interactions. Chapter 13 covers the basics of participant observation studies: advantages and disadvantages, gaining access, ethical concerns related to insider/outsider status and entanglement, and recording techniques.

Chapter 14 takes a closer look at “deep ethnography” – immersion in the field of a particularly long duration for the purpose of gaining a deeper understanding and appreciation of a particular culture or social world. Clifford Geertz called this “deep hanging out.” Whereas participant observation is often combined with semistructured interview techniques, deep ethnography’s commitment to “living the life” or experiencing the situation as it really is demands more conversational and natural interactions with people. These interactions and conversations may take place over months or even years. As can be expected, there are some costs to this technique, as well as some very large rewards when done competently. Chapter 14 provides some examples of deep ethnographies that will inspire some beginning researchers and intimidate others.

Chapter 15 moves in the opposite direction of deep ethnography, a technique that is the least positivist of all those discussed here, to mixed methods , a set of techniques that is arguably the most positivist . A mixed methods approach combines both qualitative data collection and quantitative data collection, commonly by combining a survey that is analyzed statistically (e.g., cross-tabs or regression analyses of large number probability samples) with semi-structured interviews. Although it is somewhat unconventional to discuss mixed methods in textbooks on qualitative research, I think it is important to recognize this often-employed approach here. There are several advantages and some disadvantages to taking this route. Chapter 16 will describe those advantages and disadvantages and provide some particular guidance on how to design a mixed methods study for maximum effectiveness.

Chapter 16 covers data collection that does not involve live human subjects at all – archival and historical research (chapter 17 will also cover data that does not involve interacting with human subjects). Sometimes people are unavailable to us, either because they do not wish to be interviewed or observed (as is the case with many “elites”) or because they are too far away, in both place and time. Fortunately, humans leave many traces and we can often answer questions we have by examining those traces. Special collections and archives can be goldmines for social science research. This chapter will explain how to access these places, for what purposes, and how to begin to make sense of what you find.

Chapter 17 covers another data collection area that does not involve face-to-face interaction with humans: content analysis . Although content analysis may be understood more properly as a data analysis technique, the term is often used for the entire approach, which will be the case here. Content analysis involves interpreting meaning from a body of text. This body of text might be something found in historical records (see chapter 16) or something collected by the researcher, as in the case of comment posts on a popular blog post. I once used the stories told by student loan debtors on the website studentloanjustice.org as the content I analyzed. Content analysis is particularly useful when attempting to define and understand prevalent stories or communication about a topic of interest. In other words, when we are less interested in what particular people (our defined sample) are doing or believing and more interested in what general narratives exist about a particular topic or issue. This chapter will explore different approaches to content analysis and provide helpful tips on how to collect data, how to turn that data into codes for analysis, and how to go about presenting what is found through analysis.

Where chapter 17 has pushed us towards data analysis, chapters 18 and 19 are all about what to do with the data collected, whether that data be in the form of interview transcripts or fieldnotes from observations. Chapter 18 introduces the basics of coding , the iterative process of assigning meaning to the data in order to both simplify and identify patterns. What is a code and how does it work? What are the different ways of coding data, and when should you use them? What is a codebook, and why do you need one? What does the process of data analysis look like?

Chapter 19 goes further into detail on codes and how to use them, particularly the later stages of coding in which our codes are refined, simplified, combined, and organized. These later rounds of coding are essential to getting the most out of the data we’ve collected. As students are often overwhelmed with the amount of data (a corpus of interview transcripts typically runs into the hundreds of pages; fieldnotes can easily top that), this chapter will also address time management and provide suggestions for dealing with chaos and reminders that feeling overwhelmed at the analysis stage is part of the process. By the end of the chapter, you should understand how “findings” are actually found.

The book concludes with a chapter dedicated to the effective presentation of data results. Chapter 20 covers the many ways that researchers communicate their studies to various audiences (academic, personal, political), what elements must be included in these various publications, and the hallmarks of excellent qualitative research that various audiences will be expecting. Because qualitative researchers are motivated by understanding and conveying meaning , effective communication is not only an essential skill but a fundamental facet of the entire research project. Ethnographers must be able to convey a certain sense of verisimilitude , the appearance of true reality. Those employing interviews must faithfully depict the key meanings of the people they interviewed in a way that rings true to those people, even if the end result surprises them. And all researchers must strive for clarity in their publications so that various audiences can understand what was found and why it is important.

The book concludes with a short chapter ( chapter 21 ) discussing the value of qualitative research. At the very end of this book, you will find a glossary of terms. I recommend you make frequent use of the glossary and add to each entry as you find examples. Although the entries are meant to be simple and clear, you may also want to paraphrase the definition—make it “make sense” to you, in other words. In addition to the standard reference list (all works cited here), you will find various recommendations for further reading at the end of many chapters. Some of these recommendations will be examples of excellent qualitative research, indicated with an asterisk (*) at the end of the entry. As they say, a picture is worth a thousand words. A good example of qualitative research can teach you more about conducting research than any textbook can (this one included). I highly recommend you select one to three examples from these lists and read them along with the textbook.

A final note on the choice of examples – you will note that many of the examples used in the text come from research on college students. This is for two reasons. First, as most of my research falls in this area, I am most familiar with this literature and have contacts with those who do research here and can call upon them to share their stories with you. Second, and more importantly, my hope is that this textbook reaches a wide audience of beginning researchers who study widely and deeply across the range of what can be known about the social world (from marine resources management to public policy to nursing to political science to sexuality studies and beyond). It is sometimes difficult to find examples that speak to all those research interests, however. A focus on college students is something that all readers can understand and, hopefully, appreciate, as we are all now or have been at some point a college student.

Recommended Reading: Other Qualitative Research Textbooks

I’ve included a brief list of some of my favorite qualitative research textbooks and guidebooks if you need more than what you will find in this introductory text. For each, I’ve also indicated if these are for “beginning” or “advanced” (graduate-level) readers. Many of these books have several editions that do not significantly vary; the edition recommended is merely the edition I have used in teaching and to whose page numbers any specific references made in the text agree.

Barbour, Rosaline. 2014. Introducing Qualitative Research: A Student’s Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. A good introduction to qualitative research, with abundant examples (often from the discipline of health care) and clear definitions. Includes quick summaries at the ends of each chapter. However, some US students might find the British context distracting and can be a bit advanced in some places. Beginning .

Bloomberg, Linda Dale, and Marie F. Volpe. 2012. Completing Your Qualitative Dissertation . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Specifically designed to guide graduate students through the research process. Advanced .

Creswell, John W., and Cheryl Poth. 2018 Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Traditions . 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. This is a classic and one of the go-to books I used myself as a graduate student. One of the best things about this text is its clear presentation of five distinct traditions in qualitative research. Despite the title, this reasonably sized book is about more than research design, including both data analysis and how to write about qualitative research. Advanced .