Essay on Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research

Both qualitative and quantitative researches are valued in the research world and are often used together under a single project. This is despite the fact that they have significant differences in terms of their theoretical, epistemological, and methodological formations. Qualitative research is usually in form of words while quantitative research takes the numerical approach. This paper discusses the similarities, differences, advantages, and disadvantages of qualitative and quantitative research and provides a personal stand.

Similarities

Both qualitative and quantitative research approaches begin with a problem on which scholars seek to find answers. Without a research problem or question, there would be no reason for carrying out the study. Once a problem is formulated, researchers at their own discretion and depending on the nature of the question choose the appropriate type of research to employ. Just like in qualitative research, data obtained from quantitative analysis need to be analyzed (Miles & Huberman, 1994). This step is crucial for helping researchers to gain a deeper understanding of the issue under investigation. The findings of any research enjoy confirmability after undergoing a thorough examination and auditing process (Miles & Huberman, 1994).

Both types of research approaches require a concise plan before they are carried out. Once researchers formulate the study question, they must come up with a plan for investigating the matter (Yilmaz, 2013). Such plans include deciding the appropriate research technique to implement, estimating budgets, and deciding on the study areas. Failure to plan before embarking on the research project may compromise the research findings. In addition, both qualitative and quantitative research are dependent on each other and can be used for a single research project (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Quantitative data helps the qualitative research in finding a representative study sample and obtaining the background data. In the same way, qualitative research provides the quantitative side with the conceptual development and instrumentation (Miles & Huberman, 1994).

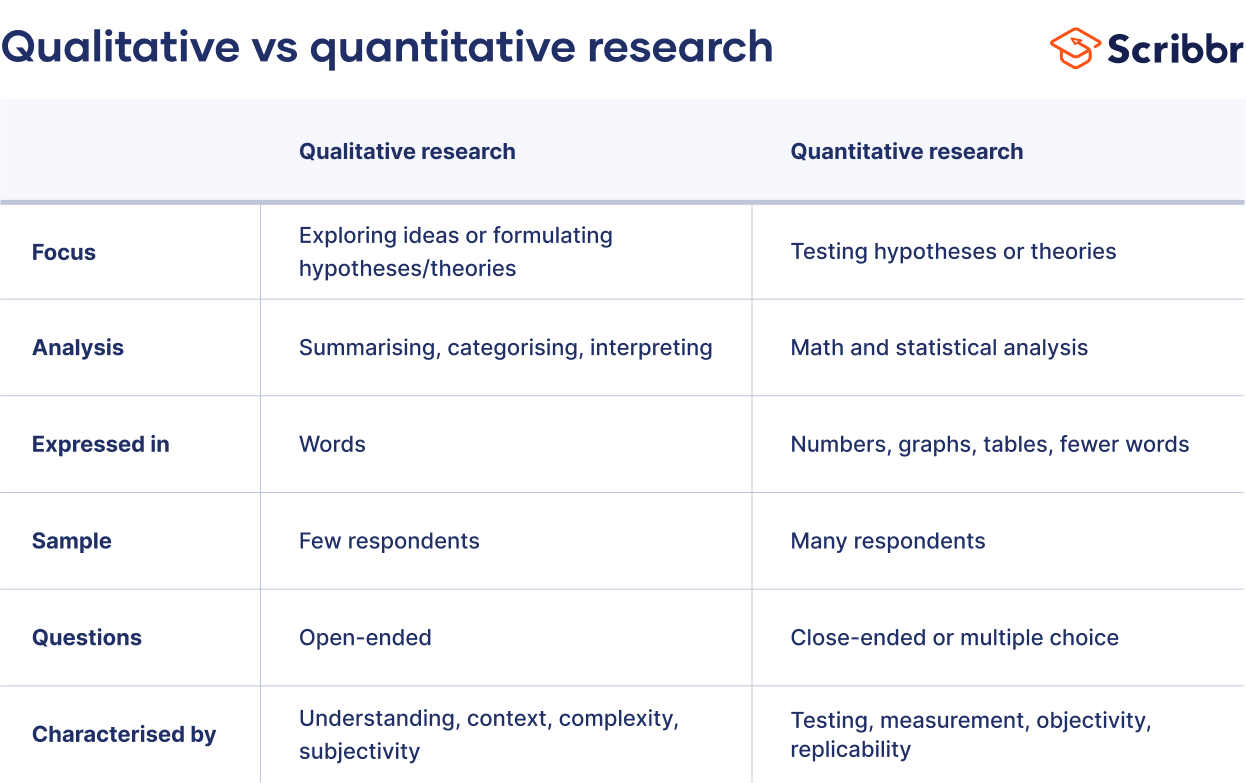

Differences

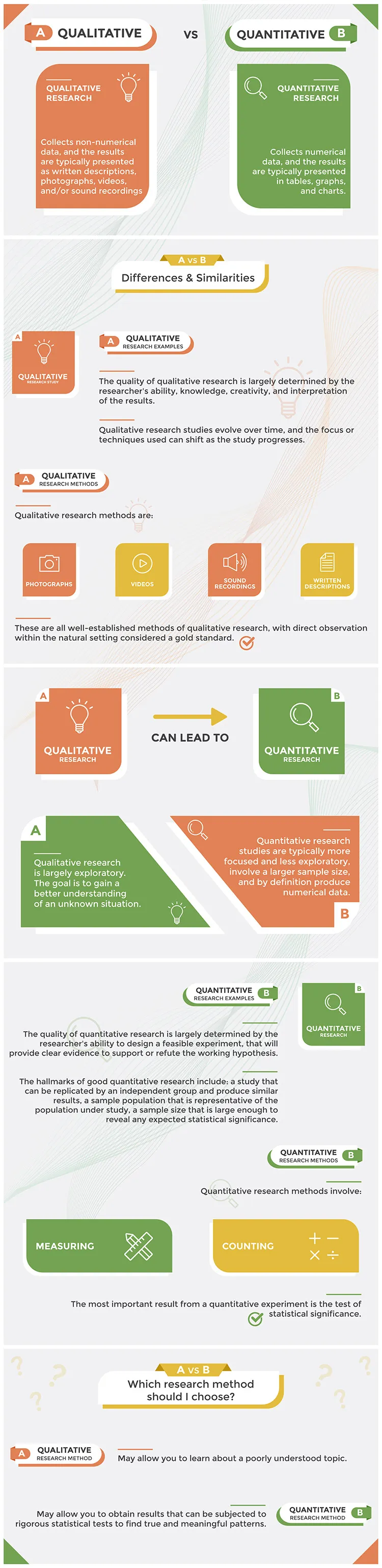

Qualitative research seeks to explain why things are the way they seem to be. It provides well-grounded descriptions and explanations of processes in identifiable local contexts (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Researchers use qualitative research to dig deeper into the problem and develop a relevant hypothesis for potential quantitative research. On the other hand, Quantitative research uses numerical data to state and quantify the problem (Yilmaz, 2013). Researchers in quantitative research use measurable data in formulating facts and uncovering the research pattern.

Quantitative research approach involves a larger number of participants for the purpose of gathering as much information as possible to summarize characteristics across large groups. This makes it a very expensive research approach. On the contrary, qualitative research approach describes a phenomenon in a more comprehensive manner. A relatively small number of participants take part in this type of research. This makes the overall process cheaper and time friendly.

Data collection methods differ significantly in the two research approaches. In quantitative research, scholars use surveys, questionnaires, and systematic measurements that involve numbers (Yilmaz, 2013). Moreover, they report their findings in impersonal third person prose by using numbers. This is different from the qualitative approach where only the participants’ observation and deep document analysis is necessary for conclusions to be drawn. Findings are disseminated in the first person’s narrative with sufficient quotations from the participants.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Qualitative Research

Qualitative data is based on human observations. Respondent’s observations connect the researcher to the most basic human experiences (Rahman, 2016). It gives a detailed production of participants’ opinions and feelings and helps in efficient interpretation of their actions (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Moreover, this research approach is interdisciplinary and entails a wide range of research techniques and epistemological viewpoints. Data collection methods in qualitative approach are both detailed and subjective (Rahman, 2016). Direct observations, unstructured interviews, and participant observation are the most common techniques employed in this type of research. Researchers have the opportunity to mingle directly with the respondents and obtain first-hand information.

On the negative side, the smaller population sample used in qualitative research raises credibility concerns (Rahman, 2016). The views of a small group of respondents may not necessarily reflect those of the entire population. Moreover, conducting this type of research on certain aspects such as the performance of students may be more challenging. In such instances, researchers prefer to use the quantitative approach instead (Rahman, 2016). Data analysis and interpretation in qualitative research is a more complex process. It is long, has elusive data, and has very stringent requirements for analysis (Rahman, 2016). In addition, developing a research question in this approach is a challenging task as the refining question mostly becomes continuous throughout the research process.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Quantitative Research

The findings of a quantitative research can be generalized to a whole population as it involves larger samples that are randomly selected by researchers (Rahman, 2016). Moreover, the methods used allows for use of statistical software in test taking (Rahman, 2016). This makes the approach time effective and efficient for tackling complex research questions. Quantitative research allows for objectivity and accuracy of the study results. This approach is well designed to provide essential information that supports generalization of a phenomenon under study. It involves few variables and many cases that guarantee the validity and credibility of the study results.

This research approach, however, has some limitations. There is a limited direct connection between the researcher and respondents. Scholars who adopt this approach measure variables at specific moments in time and disregards the past experiences of the respondents (Rahman, 2016). As a result, deep information is often ignored and only the overall picture of the variables is represented. The quantitative approach uses standard questions set and administered by researchers (Rahman, 2016). This might lead to structural bias by respondents and false representation. In some instances, data may only reflect the views of the sample under study instead of revealing the real situation. Moreover, preset questions and answers limit the freedom of expression by the respondents.

Preferred Method

I would prefer quantitative research method over the qualitative approach. Data management in this technique is much familiar and more accessible to researchers’ contexts (Miles & Huberman, 1994). It is a more scientific process that involves the collection, analysis, and interpretation of large amounts of data. Researchers have more control of the manner in which data is collected. Unlike qualitative data that requires descriptions, quantitative approach majors on numerical data (Yilmaz, 2013). With this type of data, I can use the various available software for classification and analyzes. Moreover, researchers are more flexible and free to interact with respondents. This gives an opportunity for obtaining first-hand information and learning more about other behavioral aspects of the population under study.

As highlighted above, qualitative and quantitative techniques are the two research approaches. Both seek to dig deeper into a particular problem, analyze the responses of a selected sample and make viable conclusions. However, qualitative research is much concerned with the description of peoples’ opinions, motivations, and reasons for a particular phenomenon. On the other hand, Quantitative research uses numerical data to state and explain research findings. Use of numerical data allows for objectivity and accuracy of the research results. However structural biases are common in this approach. Data collection and sampling in qualitative research is more detailed and subjective. Considering the different advantages and disadvantages of the two research approaches, I would go for the quantitative over qualitative research.

Miles, M., & Huberman, A. (1994). Qualitative data analysis (2nd Ed.). Beverly Hills: Sage.

Rahman, M. (2016). The Advantages and Disadvantages of Using Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches and Methods in Language “Testing and Assessment” Research: A Literature Review. Journal of Education and Learning , 6(1), 102.

Yilmaz, K. (2013). Comparison of Quantitative and Qualitative Research Traditions: epistemological, theoretical, and methodological differences. European Journal of Education , 48(2), 311-325.

Cite this page

Similar essay samples.

- Civil and political rights have traditionally been considered negative...

- Essay on Sleep Deprivation and College Students

- Organisational culture – Organisational structure and substructu...

- Essay on Transportation Management

- Essay on the Key Features of Equality as a Political Concept

- Shipman’s Book Review

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research Methods & Data Analysis

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

The main difference between quantitative and qualitative research is the type of data they collect and analyze.

Quantitative data is information about quantities, and therefore numbers, and qualitative data is descriptive, and regards phenomenon which can be observed but not measured, such as language.

- Quantitative research collects numerical data and analyzes it using statistical methods. The aim is to produce objective, empirical data that can be measured and expressed numerically. Quantitative research is often used to test hypotheses, identify patterns, and make predictions.

- Qualitative research gathers non-numerical data (words, images, sounds) to explore subjective experiences and attitudes, often via observation and interviews. It aims to produce detailed descriptions and uncover new insights about the studied phenomenon.

On This Page:

What Is Qualitative Research?

Qualitative research is the process of collecting, analyzing, and interpreting non-numerical data, such as language. Qualitative research can be used to understand how an individual subjectively perceives and gives meaning to their social reality.

Qualitative data is non-numerical data, such as text, video, photographs, or audio recordings. This type of data can be collected using diary accounts or in-depth interviews and analyzed using grounded theory or thematic analysis.

Qualitative research is multimethod in focus, involving an interpretive, naturalistic approach to its subject matter. This means that qualitative researchers study things in their natural settings, attempting to make sense of, or interpret, phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them. Denzin and Lincoln (1994, p. 2)

Interest in qualitative data came about as the result of the dissatisfaction of some psychologists (e.g., Carl Rogers) with the scientific study of psychologists such as behaviorists (e.g., Skinner ).

Since psychologists study people, the traditional approach to science is not seen as an appropriate way of carrying out research since it fails to capture the totality of human experience and the essence of being human. Exploring participants’ experiences is known as a phenomenological approach (re: Humanism ).

Qualitative research is primarily concerned with meaning, subjectivity, and lived experience. The goal is to understand the quality and texture of people’s experiences, how they make sense of them, and the implications for their lives.

Qualitative research aims to understand the social reality of individuals, groups, and cultures as nearly as possible as participants feel or live it. Thus, people and groups are studied in their natural setting.

Some examples of qualitative research questions are provided, such as what an experience feels like, how people talk about something, how they make sense of an experience, and how events unfold for people.

Research following a qualitative approach is exploratory and seeks to explain ‘how’ and ‘why’ a particular phenomenon, or behavior, operates as it does in a particular context. It can be used to generate hypotheses and theories from the data.

Qualitative Methods

There are different types of qualitative research methods, including diary accounts, in-depth interviews , documents, focus groups , case study research , and ethnography .

The results of qualitative methods provide a deep understanding of how people perceive their social realities and in consequence, how they act within the social world.

The researcher has several methods for collecting empirical materials, ranging from the interview to direct observation, to the analysis of artifacts, documents, and cultural records, to the use of visual materials or personal experience. Denzin and Lincoln (1994, p. 14)

Here are some examples of qualitative data:

Interview transcripts : Verbatim records of what participants said during an interview or focus group. They allow researchers to identify common themes and patterns, and draw conclusions based on the data. Interview transcripts can also be useful in providing direct quotes and examples to support research findings.

Observations : The researcher typically takes detailed notes on what they observe, including any contextual information, nonverbal cues, or other relevant details. The resulting observational data can be analyzed to gain insights into social phenomena, such as human behavior, social interactions, and cultural practices.

Unstructured interviews : generate qualitative data through the use of open questions. This allows the respondent to talk in some depth, choosing their own words. This helps the researcher develop a real sense of a person’s understanding of a situation.

Diaries or journals : Written accounts of personal experiences or reflections.

Notice that qualitative data could be much more than just words or text. Photographs, videos, sound recordings, and so on, can be considered qualitative data. Visual data can be used to understand behaviors, environments, and social interactions.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Qualitative research is endlessly creative and interpretive. The researcher does not just leave the field with mountains of empirical data and then easily write up his or her findings.

Qualitative interpretations are constructed, and various techniques can be used to make sense of the data, such as content analysis, grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006), or discourse analysis .

For example, thematic analysis is a qualitative approach that involves identifying implicit or explicit ideas within the data. Themes will often emerge once the data has been coded .

Key Features

- Events can be understood adequately only if they are seen in context. Therefore, a qualitative researcher immerses her/himself in the field, in natural surroundings. The contexts of inquiry are not contrived; they are natural. Nothing is predefined or taken for granted.

- Qualitative researchers want those who are studied to speak for themselves, to provide their perspectives in words and other actions. Therefore, qualitative research is an interactive process in which the persons studied teach the researcher about their lives.

- The qualitative researcher is an integral part of the data; without the active participation of the researcher, no data exists.

- The study’s design evolves during the research and can be adjusted or changed as it progresses. For the qualitative researcher, there is no single reality. It is subjective and exists only in reference to the observer.

- The theory is data-driven and emerges as part of the research process, evolving from the data as they are collected.

Limitations of Qualitative Research

- Because of the time and costs involved, qualitative designs do not generally draw samples from large-scale data sets.

- The problem of adequate validity or reliability is a major criticism. Because of the subjective nature of qualitative data and its origin in single contexts, it is difficult to apply conventional standards of reliability and validity. For example, because of the central role played by the researcher in the generation of data, it is not possible to replicate qualitative studies.

- Also, contexts, situations, events, conditions, and interactions cannot be replicated to any extent, nor can generalizations be made to a wider context than the one studied with confidence.

- The time required for data collection, analysis, and interpretation is lengthy. Analysis of qualitative data is difficult, and expert knowledge of an area is necessary to interpret qualitative data. Great care must be taken when doing so, for example, looking for mental illness symptoms.

Advantages of Qualitative Research

- Because of close researcher involvement, the researcher gains an insider’s view of the field. This allows the researcher to find issues that are often missed (such as subtleties and complexities) by the scientific, more positivistic inquiries.

- Qualitative descriptions can be important in suggesting possible relationships, causes, effects, and dynamic processes.

- Qualitative analysis allows for ambiguities/contradictions in the data, which reflect social reality (Denscombe, 2010).

- Qualitative research uses a descriptive, narrative style; this research might be of particular benefit to the practitioner as she or he could turn to qualitative reports to examine forms of knowledge that might otherwise be unavailable, thereby gaining new insight.

What Is Quantitative Research?

Quantitative research involves the process of objectively collecting and analyzing numerical data to describe, predict, or control variables of interest.

The goals of quantitative research are to test causal relationships between variables , make predictions, and generalize results to wider populations.

Quantitative researchers aim to establish general laws of behavior and phenomenon across different settings/contexts. Research is used to test a theory and ultimately support or reject it.

Quantitative Methods

Experiments typically yield quantitative data, as they are concerned with measuring things. However, other research methods, such as controlled observations and questionnaires , can produce both quantitative information.

For example, a rating scale or closed questions on a questionnaire would generate quantitative data as these produce either numerical data or data that can be put into categories (e.g., “yes,” “no” answers).

Experimental methods limit how research participants react to and express appropriate social behavior.

Findings are, therefore, likely to be context-bound and simply a reflection of the assumptions that the researcher brings to the investigation.

There are numerous examples of quantitative data in psychological research, including mental health. Here are a few examples:

Another example is the Experience in Close Relationships Scale (ECR), a self-report questionnaire widely used to assess adult attachment styles .

The ECR provides quantitative data that can be used to assess attachment styles and predict relationship outcomes.

Neuroimaging data : Neuroimaging techniques, such as MRI and fMRI, provide quantitative data on brain structure and function.

This data can be analyzed to identify brain regions involved in specific mental processes or disorders.

For example, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a clinician-administered questionnaire widely used to assess the severity of depressive symptoms in individuals.

The BDI consists of 21 questions, each scored on a scale of 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms.

Quantitative Data Analysis

Statistics help us turn quantitative data into useful information to help with decision-making. We can use statistics to summarize our data, describing patterns, relationships, and connections. Statistics can be descriptive or inferential.

Descriptive statistics help us to summarize our data. In contrast, inferential statistics are used to identify statistically significant differences between groups of data (such as intervention and control groups in a randomized control study).

- Quantitative researchers try to control extraneous variables by conducting their studies in the lab.

- The research aims for objectivity (i.e., without bias) and is separated from the data.

- The design of the study is determined before it begins.

- For the quantitative researcher, the reality is objective, exists separately from the researcher, and can be seen by anyone.

- Research is used to test a theory and ultimately support or reject it.

Limitations of Quantitative Research

- Context: Quantitative experiments do not take place in natural settings. In addition, they do not allow participants to explain their choices or the meaning of the questions they may have for those participants (Carr, 1994).

- Researcher expertise: Poor knowledge of the application of statistical analysis may negatively affect analysis and subsequent interpretation (Black, 1999).

- Variability of data quantity: Large sample sizes are needed for more accurate analysis. Small-scale quantitative studies may be less reliable because of the low quantity of data (Denscombe, 2010). This also affects the ability to generalize study findings to wider populations.

- Confirmation bias: The researcher might miss observing phenomena because of focus on theory or hypothesis testing rather than on the theory of hypothesis generation.

Advantages of Quantitative Research

- Scientific objectivity: Quantitative data can be interpreted with statistical analysis, and since statistics are based on the principles of mathematics, the quantitative approach is viewed as scientifically objective and rational (Carr, 1994; Denscombe, 2010).

- Useful for testing and validating already constructed theories.

- Rapid analysis: Sophisticated software removes much of the need for prolonged data analysis, especially with large volumes of data involved (Antonius, 2003).

- Replication: Quantitative data is based on measured values and can be checked by others because numerical data is less open to ambiguities of interpretation.

- Hypotheses can also be tested because of statistical analysis (Antonius, 2003).

Antonius, R. (2003). Interpreting quantitative data with SPSS . Sage.

Black, T. R. (1999). Doing quantitative research in the social sciences: An integrated approach to research design, measurement and statistics . Sage.

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology . Qualitative Research in Psychology , 3, 77–101.

Carr, L. T. (1994). The strengths and weaknesses of quantitative and qualitative research : what method for nursing? Journal of advanced nursing, 20(4) , 716-721.

Denscombe, M. (2010). The Good Research Guide: for small-scale social research. McGraw Hill.

Denzin, N., & Lincoln. Y. (1994). Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications Inc.

Glaser, B. G., Strauss, A. L., & Strutzel, E. (1968). The discovery of grounded theory; strategies for qualitative research. Nursing research, 17(4) , 364.

Minichiello, V. (1990). In-Depth Interviewing: Researching People. Longman Cheshire.

Punch, K. (1998). Introduction to Social Research: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. London: Sage

Further Information

- Mixed methods research

- Designing qualitative research

- Methods of data collection and analysis

- Introduction to quantitative and qualitative research

- Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: a case of the tail wagging the dog?

- Qualitative research in health care: Analysing qualitative data

- Qualitative data analysis: the framework approach

- Using the framework method for the analysis of

- Qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research

- Content Analysis

- Grounded Theory

- Thematic Analysis

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Quantitative vs. Qualitative Research in Psychology

- Key Differences

Quantitative Research Methods

Qualitative research methods.

- How They Relate

In psychology and other social sciences, researchers are faced with an unresolved question: Can we measure concepts like love or racism the same way we can measure temperature or the weight of a star? Social phenomena—things that happen because of and through human behavior—are especially difficult to grasp with typical scientific models.

At a Glance

Psychologists rely on quantitative and quantitative research to better understand human thought and behavior.

- Qualitative research involves collecting and evaluating non-numerical data in order to understand concepts or subjective opinions.

- Quantitative research involves collecting and evaluating numerical data.

This article discusses what qualitative and quantitative research are, how they are different, and how they are used in psychology research.

Qualitative Research vs. Quantitative Research

In order to understand qualitative and quantitative psychology research, it can be helpful to look at the methods that are used and when each type is most appropriate.

Psychologists rely on a few methods to measure behavior, attitudes, and feelings. These include:

- Self-reports , like surveys or questionnaires

- Observation (often used in experiments or fieldwork)

- Implicit attitude tests that measure timing in responding to prompts

Most of these are quantitative methods. The result is a number that can be used to assess differences between groups.

However, most of these methods are static, inflexible (you can't change a question because a participant doesn't understand it), and provide a "what" answer rather than a "why" answer.

Sometimes, researchers are more interested in the "why" and the "how." That's where qualitative methods come in.

Qualitative research is about speaking to people directly and hearing their words. It is grounded in the philosophy that the social world is ultimately unmeasurable, that no measure is truly ever "objective," and that how humans make meaning is just as important as how much they score on a standardized test.

Used to develop theories

Takes a broad, complex approach

Answers "why" and "how" questions

Explores patterns and themes

Used to test theories

Takes a narrow, specific approach

Answers "what" questions

Explores statistical relationships

Quantitative methods have existed ever since people have been able to count things. But it is only with the positivist philosophy of Auguste Comte (which maintains that factual knowledge obtained by observation is trustworthy) that it became a "scientific method."

The scientific method follows this general process. A researcher must:

- Generate a theory or hypothesis (i.e., predict what might happen in an experiment) and determine the variables needed to answer their question

- Develop instruments to measure the phenomenon (such as a survey, a thermometer, etc.)

- Develop experiments to manipulate the variables

- Collect empirical (measured) data

- Analyze data

Quantitative methods are about measuring phenomena, not explaining them.

Quantitative research compares two groups of people. There are all sorts of variables you could measure, and many kinds of experiments to run using quantitative methods.

These comparisons are generally explained using graphs, pie charts, and other visual representations that give the researcher a sense of how the various data points relate to one another.

Basic Assumptions

Quantitative methods assume:

- That the world is measurable

- That humans can observe objectively

- That we can know things for certain about the world from observation

In some fields, these assumptions hold true. Whether you measure the size of the sun 2000 years ago or now, it will always be the same. But when it comes to human behavior, it is not so simple.

As decades of cultural and social research have shown, people behave differently (and even think differently) based on historical context, cultural context, social context, and even identity-based contexts like gender , social class, or sexual orientation .

Therefore, quantitative methods applied to human behavior (as used in psychology and some areas of sociology) should always be rooted in their particular context. In other words: there are no, or very few, human universals.

Statistical information is the primary form of quantitative data used in human and social quantitative research. Statistics provide lots of information about tendencies across large groups of people, but they can never describe every case or every experience. In other words, there are always outliers.

Correlation and Causation

A basic principle of statistics is that correlation is not causation. Researchers can only claim a cause-and-effect relationship under certain conditions:

- The study was a true experiment.

- The independent variable can be manipulated (for example, researchers cannot manipulate gender, but they can change the primer a study subject sees, such as a picture of nature or of a building).

- The dependent variable can be measured through a ratio or a scale.

So when you read a report that "gender was linked to" something (like a behavior or an attitude), remember that gender is NOT a cause of the behavior or attitude. There is an apparent relationship, but the true cause of the difference is hidden.

Pitfalls of Quantitative Research

Quantitative methods are one way to approach the measurement and understanding of human and social phenomena. But what's missing from this picture?

As noted above, statistics do not tell us about personal, individual experiences and meanings. While surveys can give a general idea, respondents have to choose between only a few responses. This can make it difficult to understand the subtleties of different experiences.

Quantitative methods can be helpful when making objective comparisons between groups or when looking for relationships between variables. They can be analyzed statistically, which can be helpful when looking for patterns and relationships.

Qualitative data are not made out of numbers but rather of descriptions, metaphors, symbols, quotes, analysis, concepts, and characteristics. This approach uses interviews, written texts, art, photos, and other materials to make sense of human experiences and to understand what these experiences mean to people.

While quantitative methods ask "what" and "how much," qualitative methods ask "why" and "how."

Qualitative methods are about describing and analyzing phenomena from a human perspective. There are many different philosophical views on qualitative methods, but in general, they agree that some questions are too complex or impossible to answer with standardized instruments.

These methods also accept that it is impossible to be completely objective in observing phenomena. Researchers have their own thoughts, attitudes, experiences, and beliefs, and these always color how people interpret results.

Qualitative Approaches

There are many different approaches to qualitative research, with their own philosophical bases. Different approaches are best for different kinds of projects. For example:

- Case studies and narrative studies are best for single individuals. These involve studying every aspect of a person's life in great depth.

- Phenomenology aims to explain experiences. This type of work aims to describe and explore different events as they are consciously and subjectively experienced.

- Grounded theory develops models and describes processes. This approach allows researchers to construct a theory based on data that is collected, analyzed, and compared to reach new discoveries.

- Ethnography describes cultural groups. In this approach, researchers immerse themselves in a community or group in order to observe behavior.

Qualitative researchers must be aware of several different methods and know each thoroughly enough to produce valuable research.

Some researchers specialize in a single method, but others specialize in a topic or content area and use many different methods to explore the topic, providing different information and a variety of points of view.

There is not a single model or method that can be used for every qualitative project. Depending on the research question, the people participating, and the kind of information they want to produce, researchers will choose the appropriate approach.

Interpretation

Qualitative research does not look into causal relationships between variables, but rather into themes, values, interpretations, and meanings. As a rule, then, qualitative research is not generalizable (cannot be applied to people outside the research participants).

The insights gained from qualitative research can extend to other groups with proper attention to specific historical and social contexts.

Relationship Between Qualitative and Quantitative Research

It might sound like quantitative and qualitative research do not play well together. They have different philosophies, different data, and different outputs. However, this could not be further from the truth.

These two general methods complement each other. By using both, researchers can gain a fuller, more comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon.

For example, a psychologist wanting to develop a new survey instrument about sexuality might and ask a few dozen people questions about their sexual experiences (this is qualitative research). This gives the researcher some information to begin developing questions for their survey (which is a quantitative method).

After the survey, the same or other researchers might want to dig deeper into issues brought up by its data. Follow-up questions like "how does it feel when...?" or "what does this mean to you?" or "how did you experience this?" can only be answered by qualitative research.

By using both quantitative and qualitative data, researchers have a more holistic, well-rounded understanding of a particular topic or phenomenon.

Qualitative and quantitative methods both play an important role in psychology. Where quantitative methods can help answer questions about what is happening in a group and to what degree, qualitative methods can dig deeper into the reasons behind why it is happening. By using both strategies, psychology researchers can learn more about human thought and behavior.

Gough B, Madill A. Subjectivity in psychological science: From problem to prospect . Psychol Methods . 2012;17(3):374-384. doi:10.1037/a0029313

Pearce T. “Science organized”: Positivism and the metaphysical club, 1865–1875 . J Hist Ideas . 2015;76(3):441-465.

Adams G. Context in person, person in context: A cultural psychology approach to social-personality psychology . In: Deaux K, Snyder M, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology . Oxford University Press; 2012:182-208.

Brady HE. Causation and explanation in social science . In: Goodin RE, ed. The Oxford Handbook of Political Science. Oxford University Press; 2011. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199604456.013.0049

Chun Tie Y, Birks M, Francis K. Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers . SAGE Open Med . 2019;7:2050312118822927. doi:10.1177/2050312118822927

Reeves S, Peller J, Goldman J, Kitto S. Ethnography in qualitative educational research: AMEE Guide No. 80 . Medical Teacher . 2013;35(8):e1365-e1379. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2013.804977

Salkind NJ, ed. Encyclopedia of Research Design . Sage Publishing.

Shaughnessy JJ, Zechmeister EB, Zechmeister JS. Research Methods in Psychology . McGraw Hill Education.

By Anabelle Bernard Fournier Anabelle Bernard Fournier is a researcher of sexual and reproductive health at the University of Victoria as well as a freelance writer on various health topics.

Reference management. Clean and simple.

Qualitative vs. quantitative research - what’s the difference?

What is quantitative research?

What is quantitative research used for, how to collect data for quantitative research, what is qualitative research, what is qualitative research used for, how to collect data for qualitative research, when to use which approach, how to analyze qualitative and quantitative research, analyzing quantitative data, analyzing qualitative data, differences between qualitative and quantitative research, frequently asked questions about qualitative vs. quantitative research, related articles.

Both qualitative and quantitative research are valid and effective approaches to study a particular subject. However, it is important to know that these research approaches serve different purposes and provide different results. This guide will help illustrate quantitative and qualitative research, what they are used for, and the difference between them.

Quantitative research focuses on collecting numerical data and using it to measure variables. As such, quantitative research and data are typically expressed in numbers and graphs. Moreover, this type of research is structured and statistical and the returned results are objective.

The simplest way to describe quantitative research is that it answers the questions " what " or " how much ".

To illustrate what quantitative research is used for, let’s look at a simple example. Let’s assume you want to research the reading habits of a specific part of a population.

With this research, you would like to establish what they read. In other words, do they read fiction, non-fiction, magazines, blogs, and so on? Also, you want to establish what they read about. For example, if they read fiction, is it thrillers, romance novels, or period dramas?

With quantitative research, you can gather concrete data about these reading habits. Your research will then, for example, show that 40% of the audience reads fiction and, of that 40%, 60% prefer romance novels.

In other studies and research projects, quantitative research will work in much the same way. That is, you use it to quantify variables, opinions, behaviors, and more.

Now that we've seen what quantitative research is and what it's used for, let's look at how you'll collect data for it. Because quantitative research is structured and statistical, its data collection methods focus on collecting numerical data.

Some methods to collect this data include:

- Surveys . Surveys are one of the most popular and easiest ways to collect quantitative data. These can include anything from online surveys to paper surveys. It’s important to remember that, to collect quantitative data, you won’t be able to ask open-ended questions.

- Interviews . As is the case with qualitative data, you’ll be able to use interviews to collect quantitative data with the proviso that the data will not be based on open-ended questions.

- Observations . You’ll also be able to use observations to collect quantitative data. However, here you’ll need to make observations in an environment where variables can’t be controlled.

- Website interceptors . With website interceptors, you’ll be able to get real-time insights into a specific product, service, or subject. In most cases, these interceptors take the form of surveys displayed on websites or invitations on the website to complete the survey.

- Longitudinal studies . With these studies, you’ll gather data on the same variables over specified time periods. Longitudinal studies are often used in medical sciences and include, for instance, diet studies. It’s important to remember that, for the results to be reliable, you’ll have to collect data from the same subjects.

- Online polls . Similar to website interceptors, online polls allow you to gather data from websites or social media platforms. These polls are short with only a few options and can give you valuable insights into a very specific question or topic.

- Experiments . With experiments, you’ll manipulate some variables (your independent variables) and gather data on causal relationships between others (your dependent variables). You’ll then measure what effect the manipulation of the independent variables has on the dependent variables.

Qualitative research focuses on collecting and analyzing non-numerical data. As such, it's typically unstructured and non-statistical. The main aim of qualitative research is to get a better understanding and insights into concepts, topics, and subjects.

The easiest way to describe qualitative research is that it answers the question " why ".

Considering that qualitative research aims to provide more profound insights and understanding into specific subjects, we’ll use our example mentioned earlier to explain what qualitative research is used for.

Based on this example, you’ve now established that 40% of the population reads fiction. You’ve probably also discovered in what proportion the population consumes other reading materials.

Qualitative research will now enable you to learn the reasons for these reading habits. For example, it will show you why 40% of the readers prefer fiction, while, for instance, only 10% prefer thrillers. It thus gives you an understanding of your participants’ behaviors and actions.

We've now recapped what qualitative research is and what it's used for. Let's now consider some methods to collect data for this type of research.

Some of these data collection methods include:

- Interviews . These include one-on-one interviews with respondents where you ask open-ended questions. You’ll then record the answers from every respondent and analyze these answers later.

- Open-ended survey questions . Open-ended survey questions give you insights into why respondents feel the way they do about a particular aspect.

- Focus groups . Focus groups allow you to have conversations with small groups of people and record their opinions and views about a specific topic.

- Observations . Observations like ethnography require that you participate in a specific organization or group in order to record their routines and interactions. This will, for instance, be the case where you want to establish how customers use a product in real-life scenarios.

- Literature reviews . With literature reviews, you’ll analyze the published works of other authors to analyze the prevailing view regarding a specific subject.

- Diary studies . Diary studies allow you to collect data about peoples’ habits, activities, and experiences over time. This will, for example, show you how customers use a product, when they use it, and what motivates them.

Now, the immediate question is: When should you use qualitative research, and when should you use quantitative research? As mentioned earlier, in its simplest form:

- Quantitative research allows you to confirm or test a hypothesis or theory or quantify a specific problem or quality.

- Qualitative research allows you to understand concepts or experiences.

Let's look at how you'll use these approaches in a research project a bit closer:

- Formulating a hypothesis . As mentioned earlier, qualitative research gives you a deeper understanding of a topic. Apart from learning more profound insights about your research findings, you can also use it to formulate a hypothesis when you start your research.

- Confirming a hypothesis . Once you’ve formulated a hypothesis, you can test it with quantitative research. As mentioned, you can also use it to quantify trends and behavior.

- Finding general answers . Quantitative research can help you answer broad questions. This is because it uses a larger sample size and thus makes it easier to gather simple binary or numeric data on a specific subject.

- Getting a deeper understanding . Once you have the broad answers mentioned above, qualitative research will help you find reasons for these answers. In other words, quantitative research shows you the motives behind actions or behaviors.

Considering the above, why not consider a mixed approach ? You certainly can because these approaches are not mutually exclusive. In other words, using one does not necessarily exclude the other. Moreover, both these approaches are useful for different reasons.

This means you could use both approaches in one project to achieve different goals. For example, you could use qualitative to formulate a hypothesis. Once formulated, quantitative research will allow you to confirm the hypothesis.

So, to answer the initial question, the approach you use is up to you. However, when deciding on the right approach, you should consider the specific research project, the data you'll gather, and what you want to achieve.

No matter what approach you choose, you should design your research in such a way that it delivers results that are objective, reliable, and valid.

Both these research approaches are based on data. Once you have this data, however, you need to analyze it to answer your research questions. The method to do this depends on the research approach you use.

To analyze quantitative data, you'll need to use mathematical or statistical analysis. This can involve anything from calculating simple averages to applying complex and advanced methods to calculate the statistical significance of the results. No matter what analysis methods you use, it will enable you to spot trends and patterns in your data.

Considering the above, you can use tools, applications, and programming languages like R to calculate:

- The average of a set of numbers . This could, for instance, be the case where you calculate the average scores students obtained in a test or the average time people spend on a website.

- The frequency of a specific response . This will be the case where you, for example, use open-ended survey questions during qualitative analysis. You could then calculate the frequency of a specific response for deeper insights.

- Any correlation between different variables . Through mathematical analysis, you can calculate whether two or more variables are directly or indirectly correlated. In turn, this could help you identify trends in the data.

- The statistical significance of your results . By analyzing the data and calculating the statistical significance of the results, you'll be able to see whether certain occurrences happen randomly or because of specific factors.

Analyzing qualitative data is more complex than quantitative data. This is simply because it's not based on numerical values but rather text, images, video, and the like. As such, you won't be able to use mathematical analysis to analyze and interpret your results.

Because of this, it relies on a more interpretive analysis style and a strict analytical framework to analyze data and extract insights from it.

Some of the most common ways to analyze qualitative data include:

- Qualitative content analysis . In a content analysis, you'll analyze the language used in a specific piece of text. This allows you to understand the intentions of the author, who the audience is, and find patterns and correlations in how different concepts are communicated. A major benefit of this approach is that it follows a systematic and transparent process that other researchers will be able to replicate. As such, your research will produce highly reliable results. Keep in mind, however, that content analysis can be time-intensive and difficult to automate. ➡️ Learn how to do a content analysis in the guide.

- Thematic analysis . In a thematic analysis, you'll analyze data with a view of extracting themes, topics, and patterns in the data. Although thematic analysis can encompass a range of diverse approaches, it's usually used to analyze a collection of texts like survey responses, focus group discussions, or transcriptions of interviews. One of the main benefits of thematic analysis is that it's flexible in its approach. However, in some cases, thematic analysis can be highly subjective, which, in turn, impacts the reliability of the results. ➡️ Learn how to do a thematic analysis in this guide.

- Discourse analysis . In a discourse analysis, you'll analyze written or spoken language to understand how language is used in real-life social situations. As such, you'll be able to determine how meaning is given to language in different contexts. This is an especially effective approach if you want to gain a deeper understanding of different social groups and how they communicate with each other. As such, it's commonly used in humanities and social science disciplines.

We’ve now given a broad overview of both qualitative and quantitative research. Based on this, we can summarize the differences between these two approaches as follows:

| Focuses on testing hypotheses. Can also be used to determine general facts about a topic. | Focuses on developing an idea or hypotheses. Can also be used to gain a deeper understanding into specific topics. |

| Analysis is mainly done through mathematical or statistical analytics. | Analysis is more interpretive and involves summarizing and categorizing topics or themes and interpreting data. |

| Data is typically expressed in numbers, graphs, tables, or other numerical formats. | Data is generally expressed in words or text. |

| Requires a reasonably large sample size to be reliable. | Requires smaller sample sizes with only a few respondents. |

| Data collection is focused on closed-ended questions. | Data collection is focused on open-ended questions to extract the opinions and views on a particular subject. |

Qualitative research focuses on collecting and analyzing non-numerical data. As such, it's typically unstructured and non-statistical. The main aim of qualitative research is to get a better understanding and insights into concepts, topics, and subjects. Quantitative research focuses on collecting numerical data and using it to measure variables. As such, quantitative research and data are typically expressed in numbers and graphs. Moreover, this type of research is structured and statistical and the returned results are objective.

3 examples of qualitative research would be:

- Interviews . These include one-on-one interviews with respondents with open-ended questions. You’ll then record the answers and analyze them later.

- Observations . Observations require that you participate in a specific organization or group in order to record their routines and interactions.

3 examples of quantitative research include:

- Surveys . Surveys are one of the most popular and easiest ways to collect quantitative data. To collect quantitative data, you won’t be able to ask open-ended questions.

- Longitudinal studies . With these studies, you’ll gather data on the same variables over specified time periods. Longitudinal studies are often used in medical sciences.

The main purpose of qualitative research is to get a better understanding and insights into concepts, topics, and subjects. The easiest way to describe qualitative research is that it answers the question " why ".

The purpose of quantitative research is to collect numerical data and use it to measure variables. As such, quantitative research and data are typically expressed in numbers and graphs. The simplest way to describe quantitative research is that it answers the questions " what " or " how much ".

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

Qualitative and Quantitative Research — Explore the differences

In the research arena, there are two main approaches that researchers can take — qualitative and quantitative research. Understanding the fundamentals of these two methods is crucial for conducting effective research and obtaining accurate results.

This article provides insights into the differences between qualitative and quantitative research and we also discuss how to develop research questions for qualitative and quantitative studies, and how to gather and analyze data using these research approaches. Furthermore, we will examine how to interpret findings from qualitative and quantitative research, as well as identify ethical considerations.

By the end of this comprehensive article, readers will be equipped with the knowledge and tools to apply qualitative and quantitative research to advance knowledge in their respective fields.

What is Qualitative and Quantitative Research?

Qualitative research aims to understand complex phenomena by exploring the subjective experiences and perspectives of individuals. It focuses on gathering in-depth data through techniques such as interviews, observations, and open-ended surveys. This approach allows researchers to delve into the intricacies of the topic, uncovering unique insights that may not be captured through quantitative methods alone.

For example, imagine a study on the impact of social media on mental health. Qualitative research would involve conducting interviews with individuals who have experienced negative effects from excessive social media use. Through these interviews, researchers can gain a deep understanding of the participants' experiences, emotions, and thoughts. They can explore the nuances of how social media affects different aspects of mental health, such as self-esteem, body image, and social comparison.

Conversely, quantitative research involves collecting numerical data and analyzing it using statistical methods to identify patterns, trends, and relationships. This approach allows researchers to generalize their findings to a larger population and calculate statistically significant results. It relies on structured surveys, experiments, and other data collection methods that provide standardized data for analysis.

Continuing with the example of social media and mental health, quantitative research would involve administering surveys to a large sample of individuals. The surveys would include questions that measure various aspects of mental health, such as anxiety, depression, and life satisfaction. By collecting numerical data from a large and diverse sample, researchers can identify trends and relationships between social media use and mental health outcomes.

Both qualitative and quantitative research have their strengths and weaknesses. Qualitative research allows for a deep understanding of the topic, providing rich insights and capturing the context of the participants' experiences. It allows researchers to uncover unique perspectives and shed light on subjective experiences.

On the other hand, quantitative research entails a structured and systematic approach to data collection and analysis, allowing for comparisons and generalizations across different groups and contexts.

However, it is crucial to emphasize that qualitative and quantitative research are not mutually exclusive. They frequently serve as a complement to one another within the realm of research studies. Researchers may use qualitative methods to explore a topic in-depth and generate hypotheses, which can then be tested using quantitative methods. This combination of approaches, known as mixed methods research, allows for a more comprehensive understanding of complex phenomena.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Each Research Method

Qualitative research offers the advantage of generating detailed and nuanced data. It allows researchers to explore complex issues and gain a deeper understanding of participants' thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. However, qualitative research can be time-consuming, and data analysis may be subjective.

In contrast, quantitative research provides objective and quantifiable data, making it easier to draw conclusions and establish causation. It enables researchers to collect data from large samples, increasing the generalizability of findings. Nevertheless, quantitative research may overlook important contextual information and fail to capture the complexities of human experiences. Additionally, it requires a solid understanding of statistical techniques for accurate analysis.

When to Use Qualitative or Quantitative Research?

The choice between qualitative and quantitative research depends on the research questions and objectives. Qualitative research is appropriate when exploring new or complex phenomena, seeking in-depth insights, or generating hypotheses for further investigation. It is particularly useful in social sciences and humanities. On the other hand, quantitative research is suitable when aiming to establish causal relationships, generalize findings to a larger population, or measure phenomena systematically and objectively. It is commonly employed in sciences such as psychology, economics, and medicine.

By considering the nature of the research question, the available resources, and the desired outcomes, researchers can make an informed decision on the appropriate research approach.

How to develop research Questions for Qualitative and Quantitative Studies?

A well-defined research question is essential for conducting meaningful research. In qualitative studies, research questions are exploratory and aim to understand the experiences, perceptions, and meanings of participants. These questions should be open-ended and allow for in-depth exploration of the phenomenon under investigation.

In quantitative research, research questions are often formulated to test hypotheses or examine relationships between variables. These questions should be clear, specific, and measurable to guide data collection and analysis.

Regardless of the research approach, it is crucial to develop research questions that align with the research objectives, is feasible to investigate and contribute to existing knowledge in the field.

Gathering and Analyzing Data

Qualitative research involves collecting data through various techniques, such as interviews, focus groups, and observations. Researchers must establish rapport with participants to encourage open and honest responses. The data collected is then analyzed using methods like thematic analysis and constant comparison to identify patterns, themes, and categories. In quantitative research, data is collected using surveys, experiments, or other structured methods. Researchers aim to obtain a representative sample and ensure the reliability and validity of the data. Statistical analysis techniques, such as descriptive statistics, correlation, and regression, are then applied to conclude.

Regardless of the research approach, it is essential to document the data collection and analysis process thoroughly to ensure transparency and reproducibility.

Interpreting Findings

Interpreting findings from qualitative research involves carefully analyzing the patterns, themes, and categories identified during data analysis. Researchers aim to understand the overarching meaning of the data and draw conclusions based on the participants' experiences and perspectives. The findings are often supported by direct quotes or examples from the data. In quantitative research, findings are interpreted by analyzing statistical results and examining the significance of relationships or differences. Researchers must carefully consider the limitations of the study and the generalizability of the findings. The results are often presented using tables, charts, and graphs for clarity.

Irrespective of the research approach, it is crucial to avoid generalizing beyond the scope of the data and to consider alternative interpretations.

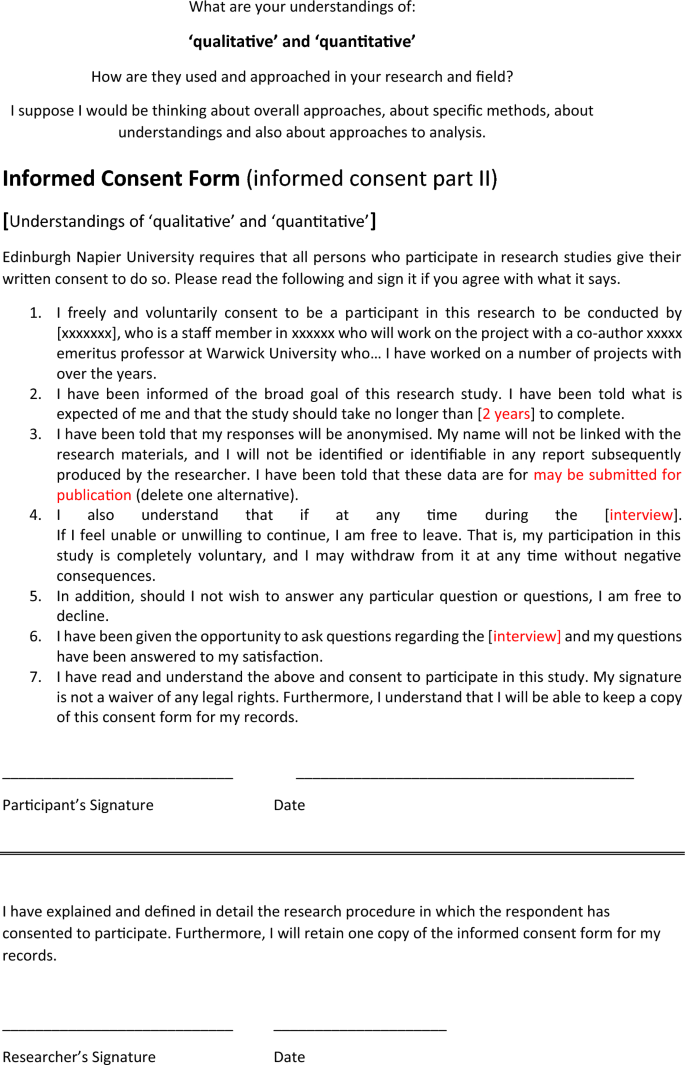

Identifying Ethical Considerations in Qualitative and Quantitative Research

Both qualitative and quantitative research must adhere to ethical guidelines to protect the rights and well-being of participants. Researchers should obtain informed consent, ensure confidentiality, and prevent harm. In qualitative research, building trust and maintaining participant anonymity is crucial. In quantitative research, privacy and data protection are paramount.

Additionally, researchers must consider the potential biases, power dynamics, and conflicts of interest that may influence the research process and findings. Being aware of these ethical considerations helps ensure the integrity and reliability of the research.

How to Write a Research Report Based on Qualitative or Quantitative Data

When writing a research report, it is essential to structure it clearly and concisely. In qualitative research, the report typically includes an introduction, literature review, methodology, findings, discussion, and conclusion. The findings section focuses on the themes and patterns identified during analysis and is supported by quotes or examples from the data.

In quantitative research, the report generally consists of an introduction, literature review, methodology, results, discussion, and conclusion. The results section presents the statistical analysis and findings in a clear and organized manner, often using tables, charts, and graphs.

The report should be written in a scholarly tone, provide sufficient details, and communicate the research findings and implications.

Assessing Reliability and Validity of Qualitative and Quantitative Results

Reliability and validity are crucial considerations in research. In qualitative research, researchers can enhance reliability by using multiple researchers to analyze the data and compare their interpretations. Validity can be strengthened by employing rigorous data collection methods, establishing trustworthiness, and including participant validation.

In quantitative research, reliability can be assessed through test-retest reliability or inter-rater reliability. Validity can be evaluated by examining internal validity, external validity, and construct validity. Additionally, researchers should carefully consider potential confounding variables and ensure proper control measures are in place.

By assessing reliability and validity, researchers can enhance the credibility and trustworthiness of their research findings.

Qualitative and quantitative research are distinct yet complementary approaches to conducting research. Understanding when to use each method, developing appropriate research questions, gathering and analyzing data, interpreting findings, and addressing ethical considerations are all critical aspects of conducting valuable research. By embracing these methodologies and applying them appropriately, researchers can contribute to the advancement of knowledge and make meaningful contributions to their respective fields.

You might also like

ChatPDF Showdown: SciSpace Chat PDF vs. Adobe PDF Reader

Boosting Citations: A Comparative Analysis of Graphical Abstract vs. Video Abstract

The Impact of Visual Abstracts on Boosting Citations

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research: Differences, Examples, and Methods

There are two broad kinds of research approaches: qualitative and quantitative research that are used to study and analyze phenomena in various fields such as natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities. Whether you have realized it or not, your research must have followed either or both research types. In this article we will discuss what qualitative vs quantitative research is, their applications, pros and cons, and when to use qualitative vs quantitative research . Before we get into the details, it is important to understand the differences between the qualitative and quantitative research.

Table of Contents

Qualitative v s Quantitative Research

Quantitative research deals with quantity, hence, this research type is concerned with numbers and statistics to prove or disapprove theories or hypothesis. In contrast, qualitative research is all about quality – characteristics, unquantifiable features, and meanings to seek deeper understanding of behavior and phenomenon. These two methodologies serve complementary roles in the research process, each offering unique insights and methods suited to different research questions and objectives.

Qualitative and quantitative research approaches have their own unique characteristics, drawbacks, advantages, and uses. Where quantitative research is mostly employed to validate theories or assumptions with the goal of generalizing facts to the larger population, qualitative research is used to study concepts, thoughts, or experiences for the purpose of gaining the underlying reasons, motivations, and meanings behind human behavior .

What Are the Differences Between Qualitative and Quantitative Research

Qualitative and quantitative research differs in terms of the methods they employ to conduct, collect, and analyze data. For example, qualitative research usually relies on interviews, observations, and textual analysis to explore subjective experiences and diverse perspectives. While quantitative data collection methods include surveys, experiments, and statistical analysis to gather and analyze numerical data. The differences between the two research approaches across various aspects are listed in the table below.

| Understanding meanings, exploring ideas, behaviors, and contexts, and formulating theories | Generating and analyzing numerical data, quantifying variables by using logical, statistical, and mathematical techniques to test or prove hypothesis | |

| Limited sample size, typically not representative | Large sample size to draw conclusions about the population | |

| Expressed using words. Non-numeric, textual, and visual narrative | Expressed using numerical data in the form of graphs or values. Statistical, measurable, and numerical | |

| Interviews, focus groups, observations, ethnography, literature review, and surveys | Surveys, experiments, and structured observations | |

| Inductive, thematic, and narrative in nature | Deductive, statistical, and numerical in nature | |

| Subjective | Objective | |

| Open-ended questions | Close-ended (Yes or No) or multiple-choice questions | |

| Descriptive and contextual | Quantifiable and generalizable | |

| Limited, only context-dependent findings | High, results applicable to a larger population | |

| Exploratory research method | Conclusive research method | |

| To delve deeper into the topic to understand the underlying theme, patterns, and concepts | To analyze the cause-and-effect relation between the variables to understand a complex phenomenon | |

| Case studies, ethnography, and content analysis | Surveys, experiments, and correlation studies |

Data Collection Methods

There are differences between qualitative and quantitative research when it comes to data collection as they deal with different types of data. Qualitative research is concerned with personal or descriptive accounts to understand human behavior within society. Quantitative research deals with numerical or measurable data to delineate relations among variables. Hence, the qualitative data collection methods differ significantly from quantitative data collection methods due to the nature of data being collected and the research objectives. Below is the list of data collection methods for each research approach:

Qualitative Research Data Collection

- Interviews

- Focus g roups

- Content a nalysis

- Literature review

- Observation

- Ethnography

Qualitative research data collection can involve one-on-one group interviews to capture in-depth perspectives of participants using open-ended questions. These interviews could be structured, semi-structured or unstructured depending upon the nature of the study. Focus groups can be used to explore specific topics and generate rich data through discussions among participants. Another qualitative data collection method is content analysis, which involves systematically analyzing text documents, audio, and video files or visual content to uncover patterns, themes, and meanings. This can be done through coding and categorization of raw data to draw meaningful insights. Data can be collected through observation studies where the goal is to simply observe and document behaviors, interaction, and phenomena in natural settings without interference. Lastly, ethnography allows one to immerse themselves in the culture or environment under study for a prolonged period to gain a deep understanding of the social phenomena.

Quantitative Research Data Collection

- Surveys/ q uestionnaires

- Experiments

- Secondary data analysis

- Structured o bservations

- Case studies

- Tests and a ssessments

Quantitative research data collection approaches comprise of fundamental methods for generating numerical data that can be analyzed using statistical or mathematical tools. The most common quantitative data collection approach is the usage of structured surveys with close-ended questions to collect quantifiable data from a large sample of participants. These can be conducted online, over the phone, or in person.

Performing experiments is another important data collection approach, in which variables are manipulated under controlled conditions to observe their effects on dependent variables. This often involves random assignment of participants to different conditions or groups. Such experimental settings are employed to gauge cause-and-effect relationships and understand a complex phenomenon. At times, instead of acquiring original data, researchers may deal with secondary data, which is the dataset curated by others, such as government agencies, research organizations, or academic institute. With structured observations, subjects in a natural environment can be studied by controlling the variables which aids in understanding the relationship among various variables. The secondary data is then analyzed to identify patterns and relationships among variables. Observational studies provide a means to systematically observe and record behaviors or phenomena as they occur in controlled environments. Case studies form an interesting study methodology in which a researcher studies a single entity or a small number of entities (individuals or organizations) in detail to understand complex phenomena within a specific context.

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research Outcomes

Qualitative research and quantitative research lead to varied research outcomes, each with its own strengths and limitations. For example, qualitative research outcomes provide deep descriptive accounts of human experiences, motivations, and perspectives that allow us to identify themes or narratives and context in which behavior, attitudes, or phenomena occurs. Quantitative research outcomes on the other hand produce numerical data that is analyzed statistically to establish patterns and relationships objectively, to form generalizations about the larger population and make predictions. This numerical data can be presented in the form of graphs, tables, or charts. Both approaches offer valuable perspectives on complex phenomena, with qualitative research focusing on depth and interpretation, while quantitative research emphasizes numerical analysis and objectivity.

When to Use Qualitative vs Quantitative Research Approach

The decision to choose between qualitative and quantitative research depends on various factors, such as the research question, objectives, whether you are taking an inductive or deductive approach, available resources, practical considerations such as time and money, and the nature of the phenomenon under investigation. To simplify, quantitative research can be used if the aim of the research is to prove or test a hypothesis, while qualitative research should be used if the research question is more exploratory and an in-depth understanding of the concepts, behavior, or experiences is needed.

Qualitative research approach

Qualitative research approach is used under following scenarios:

- To study complex phenomena: When the research requires understanding the depth, complexity, and context of a phenomenon.

- Collecting participant perspectives: When the goal is to understand the why behind a certain behavior, and a need to capture subjective experiences and perceptions of participants.

- Generating hypotheses or theories: When generating hypotheses, theories, or conceptual frameworks based on exploratory research.

Example: If you have a research question “What obstacles do expatriate students encounter when acquiring a new language in their host country?”

This research question can be addressed using the qualitative research approach by conducting in-depth interviews with 15-25 expatriate university students. Ask open-ended questions such as “What are the major challenges you face while attempting to learn the new language?”, “Do you find it difficult to learn the language as an adult?”, and “Do you feel practicing with a native friend or colleague helps the learning process”?

Based on the findings of these answers, a follow-up questionnaire can be planned to clarify things. Next step will be to transcribe all interviews using transcription software and identify themes and patterns.

Quantitative research approach

Quantitative research approach is used under following scenarios:

- Testing hypotheses or proving theories: When aiming to test hypotheses, establish relationships, or examine cause-and-effect relationships.

- Generalizability: When needing findings that can be generalized to broader populations using large, representative samples.

- Statistical analysis: When requiring rigorous statistical analysis to quantify relationships, patterns, or trends in data.

Example : Considering the above example, you can conduct a survey of 200-300 expatriate university students and ask them specific questions such as: “On a scale of 1-10 how difficult is it to learn a new language?”

Next, statistical analysis can be performed on the responses to draw conclusions like, on an average expatriate students rated the difficulty of learning a language 6.5 on the scale of 10.

Mixed methods approach

In many cases, researchers may opt for a mixed methods approach , combining qualitative and quantitative methods to leverage the strengths of both approaches. Researchers may use qualitative data to explore phenomena in-depth and generate hypotheses, while quantitative data can be used to test these hypotheses and generalize findings to broader populations.

Example: Both qualitative and quantitative research methods can be used in combination to address the above research question. Through open-ended questions you can gain insights about different perspectives and experiences while quantitative research allows you to test that knowledge and prove/disprove your hypothesis.

How to Analyze Qualitative and Quantitative Data

When it comes to analyzing qualitative and quantitative data, the focus is on identifying patterns in the data to highlight the relationship between elements. The best research method for any given study should be chosen based on the study aim. A few methods to analyze qualitative and quantitative data are listed below.

Analyzing qualitative data

Qualitative data analysis is challenging as it is not expressed in numbers and consists majorly of texts, images, or videos. Hence, care must be taken while using any analytical approach. Some common approaches to analyze qualitative data include:

- Organization: The first step is data (transcripts or notes) organization into different categories with similar concepts, themes, and patterns to find inter-relationships.

- Coding: Data can be arranged in categories based on themes/concepts using coding.

- Theme development: Utilize higher-level organization to group related codes into broader themes.

- Interpretation: Explore the meaning behind different emerging themes to understand connections. Use different perspectives like culture, environment, and status to evaluate emerging themes.

- Reporting: Present findings with quotes or excerpts to illustrate key themes.

Analyzing quantitative data