Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

How to Make a Successful Research Presentation

Turning a research paper into a visual presentation is difficult; there are pitfalls, and navigating the path to a brief, informative presentation takes time and practice. As a TA for GEO/WRI 201: Methods in Data Analysis & Scientific Writing this past fall, I saw how this process works from an instructor’s standpoint. I’ve presented my own research before, but helping others present theirs taught me a bit more about the process. Here are some tips I learned that may help you with your next research presentation:

More is more

In general, your presentation will always benefit from more practice, more feedback, and more revision. By practicing in front of friends, you can get comfortable with presenting your work while receiving feedback. It is hard to know how to revise your presentation if you never practice. If you are presenting to a general audience, getting feedback from someone outside of your discipline is crucial. Terms and ideas that seem intuitive to you may be completely foreign to someone else, and your well-crafted presentation could fall flat.

Less is more

Limit the scope of your presentation, the number of slides, and the text on each slide. In my experience, text works well for organizing slides, orienting the audience to key terms, and annotating important figures–not for explaining complex ideas. Having fewer slides is usually better as well. In general, about one slide per minute of presentation is an appropriate budget. Too many slides is usually a sign that your topic is too broad.

Limit the scope of your presentation

Don’t present your paper. Presentations are usually around 10 min long. You will not have time to explain all of the research you did in a semester (or a year!) in such a short span of time. Instead, focus on the highlight(s). Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

You will not have time to explain all of the research you did. Instead, focus on the highlights. Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

Craft a compelling research narrative

After identifying the focused research question, walk your audience through your research as if it were a story. Presentations with strong narrative arcs are clear, captivating, and compelling.

- Introduction (exposition — rising action)

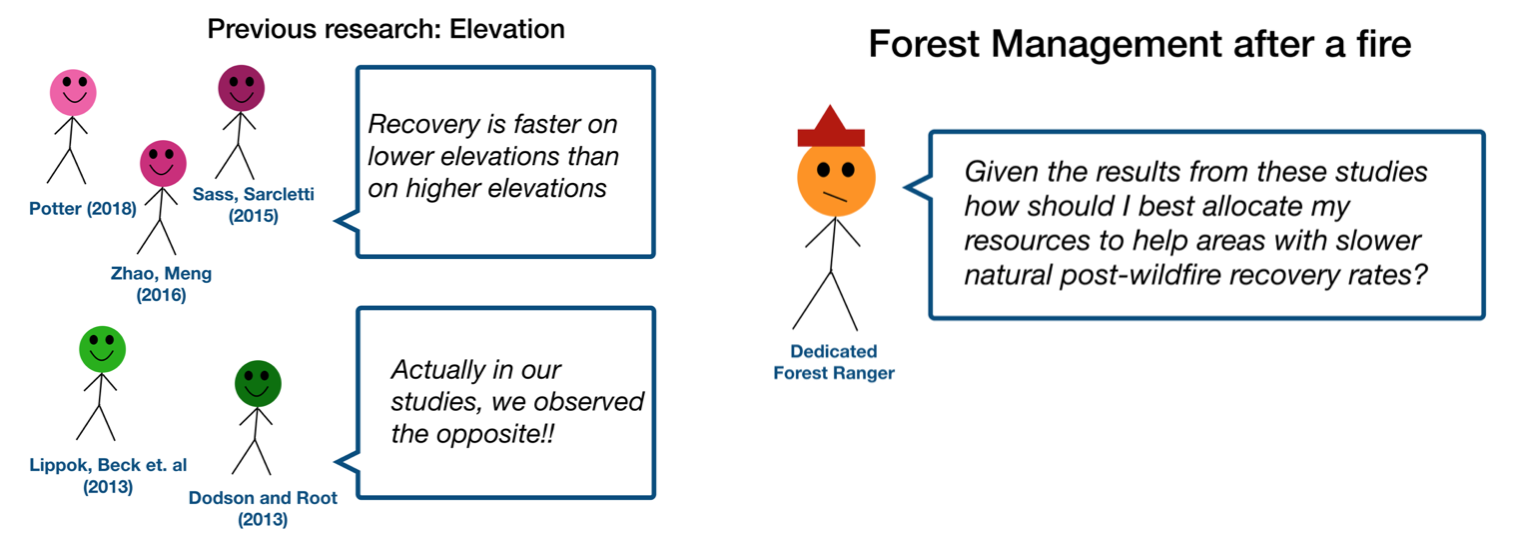

Orient the audience and draw them in by demonstrating the relevance and importance of your research story with strong global motive. Provide them with the necessary vocabulary and background knowledge to understand the plot of your story. Introduce the key studies (characters) relevant in your story and build tension and conflict with scholarly and data motive. By the end of your introduction, your audience should clearly understand your research question and be dying to know how you resolve the tension built through motive.

- Methods (rising action)

The methods section should transition smoothly and logically from the introduction. Beware of presenting your methods in a boring, arc-killing, ‘this is what I did.’ Focus on the details that set your story apart from the stories other people have already told. Keep the audience interested by clearly motivating your decisions based on your original research question or the tension built in your introduction.

- Results (climax)

Less is usually more here. Only present results which are clearly related to the focused research question you are presenting. Make sure you explain the results clearly so that your audience understands what your research found. This is the peak of tension in your narrative arc, so don’t undercut it by quickly clicking through to your discussion.

- Discussion (falling action)

By now your audience should be dying for a satisfying resolution. Here is where you contextualize your results and begin resolving the tension between past research. Be thorough. If you have too many conflicts left unresolved, or you don’t have enough time to present all of the resolutions, you probably need to further narrow the scope of your presentation.

- Conclusion (denouement)

Return back to your initial research question and motive, resolving any final conflicts and tying up loose ends. Leave the audience with a clear resolution of your focus research question, and use unresolved tension to set up potential sequels (i.e. further research).

Use your medium to enhance the narrative

Visual presentations should be dominated by clear, intentional graphics. Subtle animation in key moments (usually during the results or discussion) can add drama to the narrative arc and make conflict resolutions more satisfying. You are narrating a story written in images, videos, cartoons, and graphs. While your paper is mostly text, with graphics to highlight crucial points, your slides should be the opposite. Adapting to the new medium may require you to create or acquire far more graphics than you included in your paper, but it is necessary to create an engaging presentation.

The most important thing you can do for your presentation is to practice and revise. Bother your friends, your roommates, TAs–anybody who will sit down and listen to your work. Beyond that, think about presentations you have found compelling and try to incorporate some of those elements into your own. Remember you want your work to be comprehensible; you aren’t creating experts in 10 minutes. Above all, try to stay passionate about what you did and why. You put the time in, so show your audience that it’s worth it.

For more insight into research presentations, check out these past PCUR posts written by Emma and Ellie .

— Alec Getraer, Natural Sciences Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

- APPLICATIONS

- LEARN & SUPPORT

CST BLOG: Lab Expectations

The official blog of Cell Signaling Technology (CST), where we discuss what to expect from your time at the bench, share tips, tricks, and information.

- Career Development

How to Prepare and Deliver a Great Research Presentation

After months of running experiments, pouring over data late into the evening, and surviving on whatever snacks drift within arm’s reach, you’re about to present your research for the first time. You’ve memorized every detail, but the thought of facing a live audience still makes your palms sweaty and your knees shake.

Don’t worry, you’re not alone. Plenty of researchers would rather be knee-deep in experimental troubleshooting than face the unpredictability of a Q&A. In the lab, you know how to gear up when handling formaldehyde or BL-2 samples—if only there was PPE for the pointed questions from that one professor in the front row!

All jokes aside, whether you’re preparing your first presentation for a departmental seminar or giving a research talk at a conference, the prospect can be a daunting one. But with the right preparation, you can turn your hard-earned findings into a compelling narrative. Many CST scientists regularly present at conferences, so we sat down with a couple to get practical advice on everything from preparing slides to managing anxiety.

Step One: Understand Your Audience and Tailor Your Narrative

|

|

Before you start, take a step back and think about who will be listening to your presentation. “Consider your audience before you make any slides—or even write your presentation title,” advises Richard Cho, PhD, Associate Director of Neuroscience at CST. “After you’ve spent so much time on a topic, it’s easy to forget that what’s second nature to you might be completely new to your audience and could require a quick introduction.”

This may involve adapting field-specific jargon or adding slides to explain unfamiliar concepts. For example, the presentation you’d prepare for a smaller, departmental seminar or a focused conference in your sub-field may look very different than what you would put together for a large international event.

Understanding your audience’s familiarity with your topic, along with their background, interests, and level of technical knowledge, will help you tailor your message so that it’s relevant and easily digestible.

Step Two: Craft Compelling Slides

|

|

Slides serve as visual aids to support and enhance your verbal presentation. A well-crafted slide distills your content into key points and provides your audience with attention-grabbing visuals. “Use as few words as possible in your slides,” recommends Virginia (Ginny) Bain, PhD, Group Leader of Immunofluorescence at CST. “Images and graphs are easier for an audience to digest than text-heavy slides. Then, when you do include words, they will be more impactful.”

When designing slides, consider the size of the presentation space and ensure images are large enough to be seen by all audience members. A common stumbling block is trying to cram too much data onto a single slide.

“I’ve found nothing turns off an audience faster than feeling like they need to break out a magnifying glass to understand what they're looking at,” says Ginny. “Likewise, if you can, practice with the projector you’ll use during your talk to make sure it displays colors accurately—especially reds. Sometimes, you must add contrast to your images to ensure features aren’t lost.”

Finally, choose fonts and colors that make sense and carry the same elements throughout all slides. “Many organizations have slide templates that presenters can use,” adds Richard. “It’s worth asking if such a resource exists before you get too far along in assembling your presentation.”

The benefits of a well-crafted presentation are two-fold; first, it can act as a cue card to jog your memory as you are speaking, and second, the audience can glance at your slide if they fail to immediately catch your meaning. However, avoid the trap of simply reading full sentences or paragraphs directly from your slides. This is a surefire way to lose your audience, as they could simply read the information themselves.

Step Three: Engage Your Audience

In addition to producing slides that guide listeners through your talk, there are several techniques for keeping an audience captivated.

Storytelling

People think in stories, so one key to giving a great research talk is to tell a compelling story with your data.

“Before I start making slides, I like to come up with an overarching narrative in my head,” explains Ginny. “Of course, it always sounds amazing when I’m thinking about it, and then I write it down and realize where the holes are. However, this exercise helps me think through the whole story to identify areas that need improvement.”

It can be helpful to reflect on what excited you most about your research when you first started. What problem could your research ultimately help to solve? Why is it important? Weaving your research findings into the bigger picture can help capture your audience’s attention and make your presentation more memorable.

“One pitfall I’ve seen early researchers fall for is a desire to share their findings in sequential order. Instead, it may make more sense to organize findings in a way that illustrates a story for your audience,” explains Ginny. “As I’m crafting my narrative, I organize my data in order in a PowerPoint or on a whiteboard to help identify the bigger picture before I decide what I want to show and when.”

Storytelling provides context for your research, making complex concepts more accessible and understandable to a diverse audience.

As you weave your research into a story, consider how it might challenge the audience's expectations and whether you can use the element of surprise as a hook.

“In any good story, you’re going to have surprises,” explains Richard. “Surprises can be unexpected findings, counterintuitive results, or intriguing anecdotes that challenge conventional wisdom.” If there’s a way to do so, including surprises in your presentation can add intrigue and excitement to your talk and can spark lively discussion and debate.

“One tactic I’ve seen used successfully is to pose a question near the start of your presentation and imply to the audience that the answer might surprise them—but don’t give them the answer right away,” says Richard. “Then, later in the presentation, circle back to that question.”

Step Four: Practice, Practice, Practice

To enhance your presentation skills, it's essential to embrace practice as a critical component of preparation. Before you start, consider the format of the event and your time allotment and tailor the length of your presentation accordingly. For example, at large conferences, a moderator will often be responsible for keeping speakers on schedule, and questions are usually held until the end. In other settings, you may have more time to spend on storytelling and engaging with the audience. In those cases, it may make sense to build in extra time for questions. As you prepare, timing your practice sessions can help you pace your delivery to account for different formats.

Blog: Networking at Conferences: Five Tips for the Introverted Scientist

“Practicing your presentation is so important,” stresses Ginny. “I start intensive practice a week before my talk, which for me means giving the presentation a few times each day. Finding time to do this can be challenging, so I also rehearse while doing other things such as commuting or cooking dinner. Practicing like this has the added benefit of helping me learn how to recover when I get distracted or slip up.”

The number of practice sessions you’ll want to conduct can vary depending on a number of factors, including the length of your talk and the amount of time you have to prepare. Practicing at least three times is generally a good goal, with at least one of those practice sessions in front of a live audience. This allows you to familiarize yourself with your content, refine your delivery, and identify areas for improvement.

As you practice, get feedback on your presentation and delivery. “Opinions from your lab mates or colleagues are invaluable,” highlights Ginny. “In my experience, they often have great insights. I usually start this process early so I’m not trying to force last-minute changes that could throw me off.”

“It’s also important to get feedback from different audiences,” adds Richard. In addition to experts in your field, consider inviting peers from outside your lab, or possibly from a different research speciality, to learn to articulate messages in different ways.

When your presentation is refined, “print out thumbnails of your slides or make a PDF for your phone,” advises Ginny. “Having your slides handy for reference makes it easier to carve out moments to practice while you’re doing other things.”

Staying Focused on the Big Day

Throughout the process, remember that mastery is a journey, not a destination. Trite as it may sound, mistake-making is central to the improvement of any skill. Even well-established speakers get nervous and make mistakes.

“When you feel anxiety creeping in, ‘square breathing’ is a powerful tool for self-regulation and has helped me,” remarks Ginny. “Focus on breathing in for a count of four, holding your breath for a count of four, exhaling for a count of four, and holding again for another count of four.”

Be flexible and recognize you might not get to every point you want to cover. “It's very common to get excited and gloss over something you planned to talk about in detail,” says Ginny. “Try not to let this distract you when it happens!”

Finally, Richard suggests remembering “that we’re our own worst critics. But the truth is, the people who are watching are there to help and want to learn your story. Excitement is contagious. More often than not, if you bring your enthusiasm to your talk, your audience will be excited and supportive as well.”

So, as you step out onto the stage, trust in your preparation, try to relax, and enjoy the rewarding experience of sharing your research with the world.

Additional Resources

Check out some of the other blog posts for more career development insights:

- How to Perfect Your Elevator Pitch

- A Guide to Successful Research Collaboration

- Navigating the Many Forms of Scientific Writing in Academia

Alexandra Foley

Topics: Career Development

Automated IHC ChIP ELISA Flow IF-IC IHC Western Blot Workflow mIHC

Autophagy Cancer Immunology Cancer Research Cell Biology Developmental Biology Epigenetics Immunology Immunotherapy Medicine Metabolism Neurodegeneration Neuroscience Post Translational Modification Proteomics

Antibody Performance Antibody Validation Companion Reagents Fixation PTMScan Primary Antibodies Protocols Q&A Reproducibility Tech Tips Techniques

Corporate Social Responsibility

CST Newsletter

Popular posts, recent posts, cst dominates citeab's top cited research antibodies list—again, a most amazing molecule: validating a monoclonal antibody for the adp-ribosylation ptm.

- Our Company

- Our Approach

- Antibody Guarantee

- Social Responsibility

Help & Support

- Technical Support

- Order Information

- Scientific Resources

- Conferences & Events

- Publications & Posters

- Protein Modification Resource

- Videos & Webinars

- Trademark Info

- Privacy Policy

- Privacy Shield

- Cookie Policy

- Terms & Conditions

For Research Use Only. Not for Use in Diagnostic Procedures. © 2024 Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

- 2018/03/18/Making-a-presentation-from-your-research-proposal

Making a presentation from your research proposal

In theory, it couldn’t be easier to take your written research proposal and turn it into a presentation. Many people find presenting ideas easier than writing about them as writing is inherently difficult. On the other hand, standing up in front of a room of strangers, or worse those you know, is also a bewildering task. Essentially, you have a story to tell, but does not mean you are story telling. It means that your presentation will require you to talk continuously for your alloted period of time, and that the sentences must follow on from each other in a logical narative; i.e. a story.

So where do you start?

Here are some simple rules to help guide you to build your presentation:

- One slide per minute: However many minutes you have to present, that’s your total number of slides. Don’t be tempted to slip in more.

- Keep the format clear: There are lots of templates available to use, but you’d do best to keep your presentation very clean and simple.

- Be careful with animations: You can build your slide with animations (by adding images, words or graphics). But do not flash, bounce, rotate or roll. No animated little clipart characters. No goofy cartoons – they’ll be too small for the audience to read. No sounds (unless you are talking about sounds). Your audience has seen it all before, and that’s not what they’ve come for. They have come to hear about your research proposal.

- Don’t be a comedian: Everyone appreciates that occasional light-hearted comment, but it is not stand-up. If you feel that you must make a joke, make only one and be ready to push on when no-one reacts. Sarcasm simply won’t be understood by the majority of your audience, so don’t bother: unless you’re a witless Brit who can’t string three or more sentences together without.

Keep to your written proposal formula

- You need a title slide (with your name, that of your advisor & institution)

- that put your study into the big picture

- explain variables in the context of existing literature

- explain the relevance of your study organisms

- give the context of your own study

- Your aims & hypotheses

- Images of apparatus or diagrams of how apparatus are supposed to work. If you can’t find anything, draw it simply yourself.

- Your methods can be abbreviated. For example, you can tell the audience that you will measure your organism, but you don’t need to provide a slide of the callipers or balance (unless these are the major measurements you need).

- Analyses are important. Make sure that you understand how they work, otherwise you won’t be able to present them to others. Importantly, explain where each of the variables that you introduced, and explained how to measure, fit into the analyses. There shouldn’t be anything new or unexpected that pops up here.

- I like to see what the results might look like, even if you have to draw graphs with your own lines on it. Use arrows to show predictions under different assumptions.

Slide layout

- Your aim is to have your audience listen to you, and only look at the slides when you indicate their relevance.

- You’d be better off having a presentation without words, then your audience will listen instead of trying to read. As long as they are reading, they aren't listening. Really try to limit the words you have on any single slide (<30). Don’t have full sentences, but write just enough to remind you of what to say and so that your audience can follow when you are moving from point to point.

- Use bullet pointed lists if you have several points to make (Font 28 pt)

- If you only have words on a slide, then add a picture that will help illustrate your point. This is especially useful to illustrate your organism. At the same time, don’t have anything on a slide that has no meaning or relevance. Make sure that any illustration is large enough for your audience to see and understand what it is that you are trying to show.

- Everything on your slide must be mentioned in your presentation, so remove anything that becomes irrelevant to your story when you practice.

- Tables: you are unlikely to have large complex tables in a presentation, but presenting raw data or small words in a table is a way to lose your audience. Make your point in another way.

- Use citations (these can go in smaller font 20 pt). I like to cut out the title & authors of the paper from the pdf and show it on the slide.

- If you can, have some banner that states where you are in your presentation (e.g. Methods, or 5 of 13). It helps members of the audience who might have been daydreaming.

Practice, practice, practice

- It can’t be said enough that you must practice your presentation. Do it in front of a mirror in your bathroom. In front of your friends. It's the best way of making sure you'll do a good job.

- If you can't remember what you need to say, write flash cards with prompts. Include the text on your slide and expand. When you learn what’s on the cards, relate it to what’s on the slide so that you can look at the slides and get enough hints on what to say. Don’t bring flashcards with you to your talk. Instead be confident enough that you know them front to back and back to front.

- Practice with a pointer and slide advancer (or whatever you will use in the presentation). You should be pointing out to your audience what you have on your slides; use the pointer to do this.

- Avoid taking anything with you that you might fiddle with.

Maybe I've got it all wrong?

There are some things that I still need to learn about presentations. Have a look at the following video and see what you think. There are some really good points made here, and I think I should update my example slides to reflect these ideas. I especially like the use of contrast to focus attention.

- Presentations

- Most Recent

- Infographics

- Data Visualizations

- Forms and Surveys

- Video & Animation

- Case Studies

- Design for Business

- Digital Marketing

- Design Inspiration

- Visual Thinking

- Product Updates

- Visme Webinars

- Artificial Intelligence

How to Create a Powerful Research Presentation

Written by: Raja Mandal

Have you ever had to create a research presentation?

If yes, you know how difficult it is to prepare an effective presentation that perfectly explains your research.

Since it's a visual representation of your papers, a large chunk of its preparation goes into designing.

No one knows your research paper better than you. So, only you can create the presentation to communicate the core message perfectly.

We've developed a practical, step-by-step guide to help you prepare a stellar research presentation.

Let's get started!

Table of Contents

What is a research presentation, purpose of a research presentation, how to prepare an effective research presentation, research presentation design best practices, research presentation faqs.

- A research presentation visually showcases systematic investigation findings and allows presenters to get feedback. It's commonly used in academic settings, such as Higher Degree Research students presenting their papers.

- The purpose of a research presentation is to explain the significance of your research, clearly state your findings and methodology, get valuable feedback and make the audience learn more about your work or read your research paper.

- To prepare an effective research presentation, decide on your presentation’s goal, know your audience, create an outline, limit the amount of text on your slides, and spend more time explaining your research than summarizing old work.

- Some research presentation design tips include using an attractive background, utilizing a variety of layouts, using colors wisely, using font hierarchy and including high-quality images.

- Visme can help you create all kinds of research, corporate and creative presentations. Browse thousands of presentation templates , import a PowerPoint , whip up a custom presentation design using our AI presentation maker or create a slide deck from scratch using our drag-and-drop presentation software .

A research presentation is a visual representation of an individual's or organization's systematic investigation of a subject. It helps the presenter obtain feedback on their proposed research. For example, educational establishments require Higher Degree Research (HDR) students to present their research papers in a research presentation.

The purpose of a research presentation is to share the findings with the world. When done well, it helps achieve significant levels of impact in front of groups of people. Delivering the research paper as a presentation also communicates the subject matter in powerful ways.

A beautifully designed research presentation should:

- Explain the significance of your research.

- Clearly state your findings and the method of analysis.

- Get valuable feedback from others in your community to strengthen your research.

- Make the audience learn more about your work or read your research paper.

Create a stunning presentation in less time

- Hundreds of premade slides available

- Add animation and interactivity to your slides

- Choose from various presentation options

Sign up. It’s free.

Most research presentations can be boring, especially if your data is not presented in an engaging way. You should prepare your presentation in a way that attracts and persuades your audience while drawing attention to the main points.

Follow the steps below to do that.

Decide on Your Presentation’s Purpose

Beginning the design process without deciding on the purpose of your presentation is like crawling in the dark without knowing the destination. You should first know the purpose of your presentation before creating it.

The purpose of a research presentation can be defending a dissertation, an academic job interview, a conference, asking for funding, and various others. The rest of the process will depend on the purpose of your presentation.

Look at these 25 different presentation examples to get inspiration and find the one that best fits your needs.

Know Your Audience

You probably wouldn't speak to your lecturer like you talk to your friends. Creating a presentation is the same—you need to tailor your presentation's design, tone and content to make it appropriate for your audience.

To do that, you need to establish who your audience is. Your audience could be:

- Scientists/scholars in your field

- Graduate and undergraduate students

- Community members

Your target audience might be a mix of all of the above. In that case, it's better to have something for everyone. Once you know who your target audience is, ask yourself the following questions:

- Why are they here?

- What do they expect from your presentations?

- Are they willing to participate?

- What will keep them engaged?

- What do you want them to do and what's their part in your presentation?

- How do they prefer to receive information?

The answers to these questions will help you know your audience better and prepare your research presentation accordingly. Once you define your target audience, use these five traits of a highly engaging presentation to capture your audience's attention.

Create a Research Presentation Outline

Before crafting your presentation, it's crucial to create a presentation outline . Your outline will act as your guide to put your information in order and ensure you touch on all your major points.

Like other forms of academic writing, research presentations can be divided into several parts to make them more effective.

A research outline will:

- Guide you as you prepare your presentation

- Enable you to organize your ideas

- Present your research in a logical format

- Show the relationships among slides in your presentation

- Construct an order overview of your presentation

- Group ideas into main points

Though there is no universal formula for a research presentation outline, here's an example of what the outline should look like:

- Introduction and purpose

- Background and context

- Data and methodology

- Descriptive data

- Quantitative and qualitative analysis

- Future Research

Pro Tip: If your presentation needs to go through several rounds of edits or approvals, such as in the outline stage, streamline the process using Visme’s workflows . Instead of sending files back and forth, you can simply assign tasks and set up reviews or approvals.

Learn more about presentation structure to keep your audience engaged. Watch the video below for a better understanding.

Limit the Amount of Text on Your Slides

One of the most important things people often overlook is the amount of text on their presentation slides . Since the audience will be listening and watching, putting up a slide with lots of words will make them focus on reading instead of listening. As a result, they'll miss out on any critical points you are making.

The simpler you make your slides, the more your audience will grasp the meaning and retain the critical information. Here are a few ways to limit the amount of text on your slides.

1. Use Only Crucial Text on the Slides

Without making your point clear immediately, you will struggle to keep your audience's attention. Too much text can make your slides look cluttered and overwhelm the audience. Cut out waffle words, limiting content to the essentials.

If you’re struggling with summarizing your content or articulating your idea succinctly, use Visme’s AI Writer to create or shorten text into concise bullet points.

To avoid cognitive overload, combine text and images . Add animated graphics , icons , characters and gestures to bring your research presentation to life and capture your audience's attention.

2. Split up the Content Onto Multiple Slides

We recommend using one piece of information on a single slide. If you're talking about two or more topics, divide the topics into different slides to make your slides easily digestible and less daunting. The less information on each slide, the more your audience is likely to read.

3. Put Key Message Into the Heading

Use the slide headings of your presentation as a summary message. Think about the one key point you want the audience to take from each slide. And make the header short and impactful. This will ensure that your audience gets the main points immediately.

For example, you may have a statistic you want to really get across to your audience. Include that number in your heading so that it's the first point your audience reads.

But what if that statistic changes? Having to manually go back and update the number throughout your research presentation can be time-consuming.

With Visme's Dynamic Fields feature , updating important information throughout your presentation is a breeze. Take advantage of Dynamic Fields to ensure your data and research information is always up to date and accurate.

4. Visualize Data Instead of Writing Them

When adding facts and figures to your research presentation, harness the power of data visualization . Add charts and graphs to take out most of the text. You can also animate your charts and transform your slide deck into an interactive presentation .

Text with visuals causes a faster and stronger reaction than words alone, making your presentation more memorable. However, your data visualization should be straightforward to help create a narrative that further builds connections between information.

Have a look at these data visualization examples for inspiration. And here's an infographic explaining data visualization best practices.

Visme comes with a wide variety of charts and graphs templates you can use in your presentation.

5. Use Presenter Notes

Visme's Presenter Studio comes with a presenter notes feature that can help you keep your slides succinct. Use it to pull out any additional text that the audience needs to understand the content.

View your notes for each slide in the left sidebar of the presentation software to help you stay focused and on message throughout your presentation.

Explain Your Research

Some people spend nearly all of the presentation going over the existing research and giving background information on the particular case. Since you're preparing a research presentation, use more slides to explain the research papers you directly contributed to. This is also helpful to do when creating a grant proposal .

Your audience is there to learn about your new and exciting research, not to hear a summary of old work. So, if you create 20 slides for the presentation, spend at least 15 slides explaining your research, findings, and the key takeaways or recommendations.

Use Visme’s collaboration tools to work on your research presentation together with your team. This will help you create a well-rounded presentation that includes all the necessary points, even those that you did not work on directly.

Learn more about how to give a good presentation . This will help you explain your research more effectively.

A study shows that 91% of presenters feel more confident when presenting a well-designed slide deck. So, let's move on to the design part of your research presentation to boost your confidence.

1. Use an Attractive Background

The background of each presentation slide is a crucial design element for your presentation. So choose the background carefully. Try not to use backgrounds that are distracting or make the text difficult to read.

Use simple and relevant backgrounds to make the slide aesthetically appealing. Always use the same background for the slides throughout the presentation. Look at these presentation background templates and examples to get inspired.

2. Use a Variety of Layouts

Slide after slide of the same layout makes your presentation repetitive and boring. Mixing up the layout of your slides can help you avoid this issue and keep your audience engaged.

The presentation template below has a wide variety of images, texts, icons and other elements to create an interesting layout for your presentation slides.

Have a look at these 29 best presentation templates for inspiration.

3. Use Colors Wisely

Colors play an essential role in designing your presentation slides, regardless of the type of presentation you're working with. However, if you're a non-designer, you might be unsure about about how to use colors in a presentation . So, here are some tips for you:

- Use complementary colors to stay on the safe side.

- Use a text color that contrasts with the background to make the text pop.

- Use colors to emphasize a text or design element.

- Keep colors simple — less is more.

Don't be discouraged if you still find it difficult to choose colors for your presentation. All the presentation templates in Visme come with perfect color combinations to get the job done for you.

Below is an example of a research project presentation.

4. Use Fonts Hierarchy

Fonts are another design element that can make or break the design of your research presentation. If you struggle a lot while choosing fonts for a presentation , you aren't alone. Here are some tips that you can follow:

- Try not to use smaller fonts that make your text difficult to read.

- Use different font sizes for headings and body text. For example, you can use 20 points for the body text, 24 for the subheadings and 40 for the title.

- Learn about font pairing and use it in your design. For example, use sans-serif with serif fonts as they always go well together.

- Use two or three fonts max—ideally two. One should be for the headlines and the other for the body text. Anything more than that can make your slides cluttered.

- Handwritten fonts and script fonts may look tempting, but they are a big no. They could negatively affect the readability and legibility of your research presentation.

Here's a research presentation template from Visme designed with the points mentioned above in mind.

5. Include High-Resolution Images

Are there any images you can use in your research presentation slides to introduce or explain a topic? As the saying goes, "A picture tells a thousand words." Use pictures to help your audience listen to you more efficiently while viewing the slides.

Pictures can also help you reduce the text clutter in the presentation, as long as they prompt you to make the points you need to make. Upload your own photos or browse through Visme's high-resolution stock photo library . It features over 1,000,000 free stock photos.

If you can’t find the perfect image, don’t worry. Use Visme’s AI Image Generator to whip one up for you based on prompts. You can also use our AI Image Editing tools to unblur, upscale and remove unwanted backgrounds from your photos.

Have a look at the presentation template below. It includes only high-resolution images, like all the presentation templates in Visme.

Below is a video of 13 presentation design tips to help you design a research presentation that your audience will love.

How to do a 5 minute research presentation?

Here are some tips to wrap up a research presentation in 5 minutes:

- Focus on key points: Get to the meat of it quickly. Briefly introduce the topic, explain your methodology, present main findings and then conclude your presentation.

- Less is more: Keep your presentation to 3-5 slides max, and use bullet points and visuals over walls of text.

- Rehearse and refine: Practice delivering your presentation within the time limit before the big day. Trim content if you consistently run over, and aim to finish at 4:30 to allow for any unexpected pauses.

How long should a research presentation be?

According to Guy Kawaski’s 10/20/30 rule , your research presentation should be no more than 10 slides and take no longer than 20 minutes to present.

How do you introduce yourself in a research presentation?

Introduce yourself by clearly stating your name, institute and research focus. For example: "I'm Jane Doe from XYZ University. My research examines the impact of climate change on coral reefs."

How many slides should a research presentation have?

As a general rule, you should spend 1-2 minutes on each slide. This means you should aim for around 5-10 slides for a 10-minute research presentation.

Prepare Your Research Presentation Using Visme

Designing presentation slides from scratch isn't easy, especially if you have no experience. Fortunately, Visme comes with hundreds of professional presentation templates crafted by expert designers that make the job easy for you.

You don't need any design experience to create effective research presentations, corporate presentations and even creative presentations .

Choose from hundreds of beautifully designed presentation templates and customize them according to your needs using Visme's all-in-one presentation software . Anyone can use our powerful software to create stunning presentations in minutes.

Create a free account in Visme today and start creating your research presentation like an expert.

Put together powerful research presentations in minutes with Visme.

Trusted by leading brands

Recommended content for you:

Create Stunning Content!

Design visual brand experiences for your business whether you are a seasoned designer or a total novice.

About the Author

Raja Antony Mandal is a Content Writer at Visme. He can quickly adapt to different writing styles, possess strong research skills, and know SEO fundamentals. Raja wants to share valuable information with his audience by telling captivating stories in his articles. He wants to travel and party a lot on the weekends, but his guitar, drum set, and volleyball court don’t let him.

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

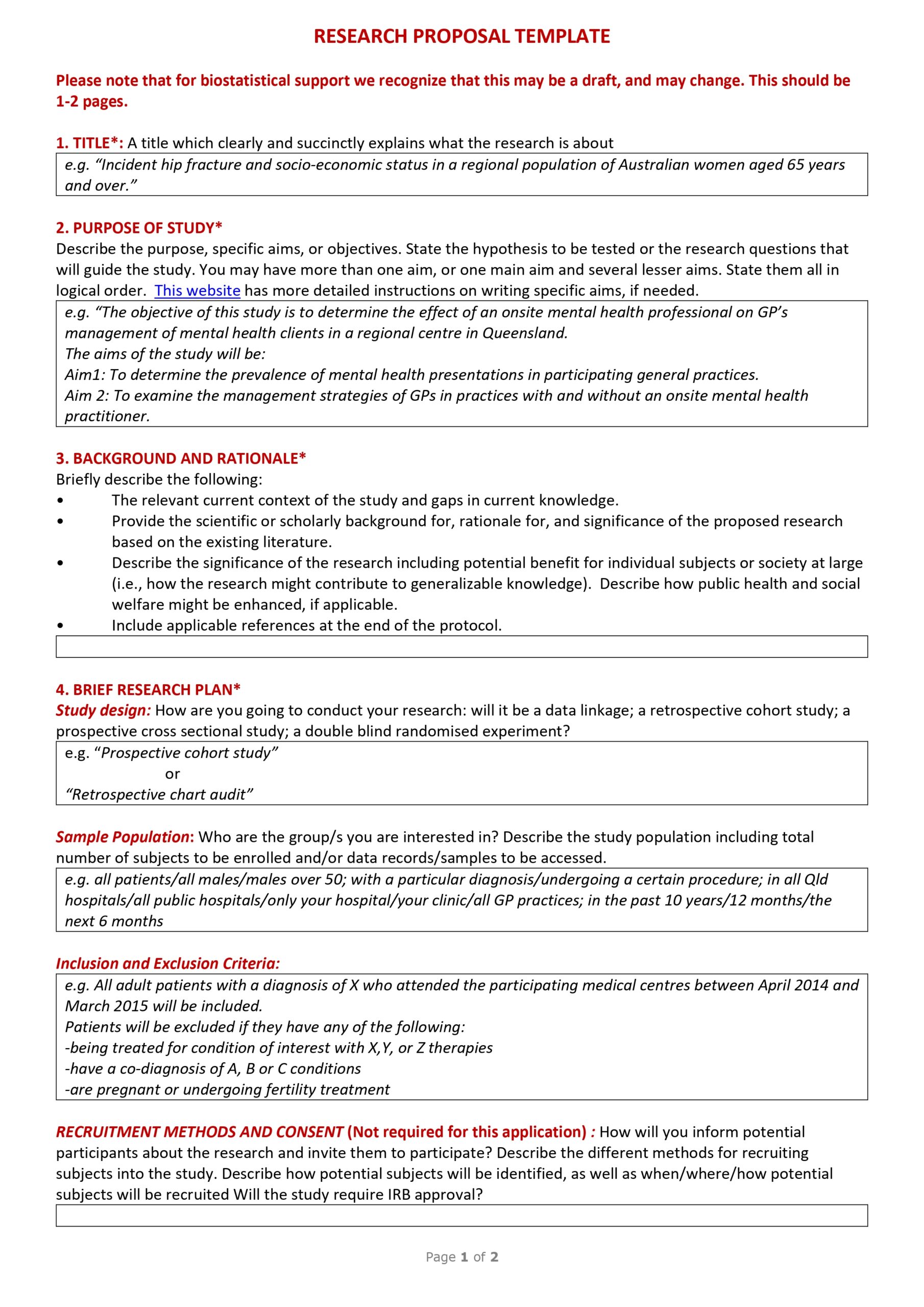

The goal of a research proposal is twofold: to present and justify the need to study a research problem and to present the practical ways in which the proposed study should be conducted. The design elements and procedures for conducting research are governed by standards of the predominant discipline in which the problem resides, therefore, the guidelines for research proposals are more exacting and less formal than a general project proposal. Research proposals contain extensive literature reviews. They must provide persuasive evidence that a need exists for the proposed study. In addition to providing a rationale, a proposal describes detailed methodology for conducting the research consistent with requirements of the professional or academic field and a statement on anticipated outcomes and benefits derived from the study's completion.

Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005.

How to Approach Writing a Research Proposal

Your professor may assign the task of writing a research proposal for the following reasons:

- Develop your skills in thinking about and designing a comprehensive research study;

- Learn how to conduct a comprehensive review of the literature to determine that the research problem has not been adequately addressed or has been answered ineffectively and, in so doing, become better at locating pertinent scholarship related to your topic;

- Improve your general research and writing skills;

- Practice identifying the logical steps that must be taken to accomplish one's research goals;

- Critically review, examine, and consider the use of different methods for gathering and analyzing data related to the research problem; and,

- Nurture a sense of inquisitiveness within yourself and to help see yourself as an active participant in the process of conducting scholarly research.

A proposal should contain all the key elements involved in designing a completed research study, with sufficient information that allows readers to assess the validity and usefulness of your proposed study. The only elements missing from a research proposal are the findings of the study and your analysis of those findings. Finally, an effective proposal is judged on the quality of your writing and, therefore, it is important that your proposal is coherent, clear, and compelling.

Regardless of the research problem you are investigating and the methodology you choose, all research proposals must address the following questions:

- What do you plan to accomplish? Be clear and succinct in defining the research problem and what it is you are proposing to investigate.

- Why do you want to do the research? In addition to detailing your research design, you also must conduct a thorough review of the literature and provide convincing evidence that it is a topic worthy of in-depth study. A successful research proposal must answer the "So What?" question.

- How are you going to conduct the research? Be sure that what you propose is doable. If you're having difficulty formulating a research problem to propose investigating, go here for strategies in developing a problem to study.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Failure to be concise . A research proposal must be focused and not be "all over the map" or diverge into unrelated tangents without a clear sense of purpose.

- Failure to cite landmark works in your literature review . Proposals should be grounded in foundational research that lays a foundation for understanding the development and scope of the the topic and its relevance.

- Failure to delimit the contextual scope of your research [e.g., time, place, people, etc.]. As with any research paper, your proposed study must inform the reader how and in what ways the study will frame the problem.

- Failure to develop a coherent and persuasive argument for the proposed research . This is critical. In many workplace settings, the research proposal is a formal document intended to argue for why a study should be funded.

- Sloppy or imprecise writing, or poor grammar . Although a research proposal does not represent a completed research study, there is still an expectation that it is well-written and follows the style and rules of good academic writing.

- Too much detail on minor issues, but not enough detail on major issues . Your proposal should focus on only a few key research questions in order to support the argument that the research needs to be conducted. Minor issues, even if valid, can be mentioned but they should not dominate the overall narrative.

Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Sanford, Keith. Information for Students: Writing a Research Proposal. Baylor University; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences, Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Structure and Writing Style

Beginning the Proposal Process

As with writing most college-level academic papers, research proposals are generally organized the same way throughout most social science disciplines. The text of proposals generally vary in length between ten and thirty-five pages, followed by the list of references. However, before you begin, read the assignment carefully and, if anything seems unclear, ask your professor whether there are any specific requirements for organizing and writing the proposal.

A good place to begin is to ask yourself a series of questions:

- What do I want to study?

- Why is the topic important?

- How is it significant within the subject areas covered in my class?

- What problems will it help solve?

- How does it build upon [and hopefully go beyond] research already conducted on the topic?

- What exactly should I plan to do, and can I get it done in the time available?

In general, a compelling research proposal should document your knowledge of the topic and demonstrate your enthusiasm for conducting the study. Approach it with the intention of leaving your readers feeling like, "Wow, that's an exciting idea and I can’t wait to see how it turns out!"

Most proposals should include the following sections:

I. Introduction

In the real world of higher education, a research proposal is most often written by scholars seeking grant funding for a research project or it's the first step in getting approval to write a doctoral dissertation. Even if this is just a course assignment, treat your introduction as the initial pitch of an idea based on a thorough examination of the significance of a research problem. After reading the introduction, your readers should not only have an understanding of what you want to do, but they should also be able to gain a sense of your passion for the topic and to be excited about the study's possible outcomes. Note that most proposals do not include an abstract [summary] before the introduction.

Think about your introduction as a narrative written in two to four paragraphs that succinctly answers the following four questions :

- What is the central research problem?

- What is the topic of study related to that research problem?

- What methods should be used to analyze the research problem?

- Answer the "So What?" question by explaining why this is important research, what is its significance, and why should someone reading the proposal care about the outcomes of the proposed study?

II. Background and Significance

This is where you explain the scope and context of your proposal and describe in detail why it's important. It can be melded into your introduction or you can create a separate section to help with the organization and narrative flow of your proposal. Approach writing this section with the thought that you can’t assume your readers will know as much about the research problem as you do. Note that this section is not an essay going over everything you have learned about the topic; instead, you must choose what is most relevant in explaining the aims of your research.

To that end, while there are no prescribed rules for establishing the significance of your proposed study, you should attempt to address some or all of the following:

- State the research problem and give a more detailed explanation about the purpose of the study than what you stated in the introduction. This is particularly important if the problem is complex or multifaceted .

- Present the rationale of your proposed study and clearly indicate why it is worth doing; be sure to answer the "So What? question [i.e., why should anyone care?].

- Describe the major issues or problems examined by your research. This can be in the form of questions to be addressed. Be sure to note how your proposed study builds on previous assumptions about the research problem.

- Explain the methods you plan to use for conducting your research. Clearly identify the key sources you intend to use and explain how they will contribute to your analysis of the topic.

- Describe the boundaries of your proposed research in order to provide a clear focus. Where appropriate, state not only what you plan to study, but what aspects of the research problem will be excluded from the study.

- If necessary, provide definitions of key concepts, theories, or terms.

III. Literature Review

Connected to the background and significance of your study is a section of your proposal devoted to a more deliberate review and synthesis of prior studies related to the research problem under investigation . The purpose here is to place your project within the larger whole of what is currently being explored, while at the same time, demonstrating to your readers that your work is original and innovative. Think about what questions other researchers have asked, what methodological approaches they have used, and what is your understanding of their findings and, when stated, their recommendations. Also pay attention to any suggestions for further research.

Since a literature review is information dense, it is crucial that this section is intelligently structured to enable a reader to grasp the key arguments underpinning your proposed study in relation to the arguments put forth by other researchers. A good strategy is to break the literature into "conceptual categories" [themes] rather than systematically or chronologically describing groups of materials one at a time. Note that conceptual categories generally reveal themselves after you have read most of the pertinent literature on your topic so adding new categories is an on-going process of discovery as you review more studies. How do you know you've covered the key conceptual categories underlying the research literature? Generally, you can have confidence that all of the significant conceptual categories have been identified if you start to see repetition in the conclusions or recommendations that are being made.

NOTE: Do not shy away from challenging the conclusions made in prior research as a basis for supporting the need for your proposal. Assess what you believe is missing and state how previous research has failed to adequately examine the issue that your study addresses. Highlighting the problematic conclusions strengthens your proposal. For more information on writing literature reviews, GO HERE .

To help frame your proposal's review of prior research, consider the "five C’s" of writing a literature review:

- Cite , so as to keep the primary focus on the literature pertinent to your research problem.

- Compare the various arguments, theories, methodologies, and findings expressed in the literature: what do the authors agree on? Who applies similar approaches to analyzing the research problem?

- Contrast the various arguments, themes, methodologies, approaches, and controversies expressed in the literature: describe what are the major areas of disagreement, controversy, or debate among scholars?

- Critique the literature: Which arguments are more persuasive, and why? Which approaches, findings, and methodologies seem most reliable, valid, or appropriate, and why? Pay attention to the verbs you use to describe what an author says/does [e.g., asserts, demonstrates, argues, etc.].

- Connect the literature to your own area of research and investigation: how does your own work draw upon, depart from, synthesize, or add a new perspective to what has been said in the literature?

IV. Research Design and Methods

This section must be well-written and logically organized because you are not actually doing the research, yet, your reader must have confidence that you have a plan worth pursuing . The reader will never have a study outcome from which to evaluate whether your methodological choices were the correct ones. Thus, the objective here is to convince the reader that your overall research design and proposed methods of analysis will correctly address the problem and that the methods will provide the means to effectively interpret the potential results. Your design and methods should be unmistakably tied to the specific aims of your study.

Describe the overall research design by building upon and drawing examples from your review of the literature. Consider not only methods that other researchers have used, but methods of data gathering that have not been used but perhaps could be. Be specific about the methodological approaches you plan to undertake to obtain information, the techniques you would use to analyze the data, and the tests of external validity to which you commit yourself [i.e., the trustworthiness by which you can generalize from your study to other people, places, events, and/or periods of time].

When describing the methods you will use, be sure to cover the following:

- Specify the research process you will undertake and the way you will interpret the results obtained in relation to the research problem. Don't just describe what you intend to achieve from applying the methods you choose, but state how you will spend your time while applying these methods [e.g., coding text from interviews to find statements about the need to change school curriculum; running a regression to determine if there is a relationship between campaign advertising on social media sites and election outcomes in Europe ].

- Keep in mind that the methodology is not just a list of tasks; it is a deliberate argument as to why techniques for gathering information add up to the best way to investigate the research problem. This is an important point because the mere listing of tasks to be performed does not demonstrate that, collectively, they effectively address the research problem. Be sure you clearly explain this.

- Anticipate and acknowledge any potential barriers and pitfalls in carrying out your research design and explain how you plan to address them. No method applied to research in the social and behavioral sciences is perfect, so you need to describe where you believe challenges may exist in obtaining data or accessing information. It's always better to acknowledge this than to have it brought up by your professor!

V. Preliminary Suppositions and Implications

Just because you don't have to actually conduct the study and analyze the results, doesn't mean you can skip talking about the analytical process and potential implications . The purpose of this section is to argue how and in what ways you believe your research will refine, revise, or extend existing knowledge in the subject area under investigation. Depending on the aims and objectives of your study, describe how the anticipated results will impact future scholarly research, theory, practice, forms of interventions, or policy making. Note that such discussions may have either substantive [a potential new policy], theoretical [a potential new understanding], or methodological [a potential new way of analyzing] significance. When thinking about the potential implications of your study, ask the following questions:

- What might the results mean in regards to challenging the theoretical framework and underlying assumptions that support the study?

- What suggestions for subsequent research could arise from the potential outcomes of the study?

- What will the results mean to practitioners in the natural settings of their workplace, organization, or community?

- Will the results influence programs, methods, and/or forms of intervention?

- How might the results contribute to the solution of social, economic, or other types of problems?

- Will the results influence policy decisions?

- In what way do individuals or groups benefit should your study be pursued?

- What will be improved or changed as a result of the proposed research?

- How will the results of the study be implemented and what innovations or transformative insights could emerge from the process of implementation?

NOTE: This section should not delve into idle speculation, opinion, or be formulated on the basis of unclear evidence . The purpose is to reflect upon gaps or understudied areas of the current literature and describe how your proposed research contributes to a new understanding of the research problem should the study be implemented as designed.

ANOTHER NOTE : This section is also where you describe any potential limitations to your proposed study. While it is impossible to highlight all potential limitations because the study has yet to be conducted, you still must tell the reader where and in what form impediments may arise and how you plan to address them.

VI. Conclusion

The conclusion reiterates the importance or significance of your proposal and provides a brief summary of the entire study . This section should be only one or two paragraphs long, emphasizing why the research problem is worth investigating, why your research study is unique, and how it should advance existing knowledge.

Someone reading this section should come away with an understanding of:

- Why the study should be done;

- The specific purpose of the study and the research questions it attempts to answer;

- The decision for why the research design and methods used where chosen over other options;

- The potential implications emerging from your proposed study of the research problem; and

- A sense of how your study fits within the broader scholarship about the research problem.

VII. Citations

As with any scholarly research paper, you must cite the sources you used . In a standard research proposal, this section can take two forms, so consult with your professor about which one is preferred.

- References -- a list of only the sources you actually used in creating your proposal.

- Bibliography -- a list of everything you used in creating your proposal, along with additional citations to any key sources relevant to understanding the research problem.

In either case, this section should testify to the fact that you did enough preparatory work to ensure the project will complement and not just duplicate the efforts of other researchers. It demonstrates to the reader that you have a thorough understanding of prior research on the topic.

Most proposal formats have you start a new page and use the heading "References" or "Bibliography" centered at the top of the page. Cited works should always use a standard format that follows the writing style advised by the discipline of your course [e.g., education=APA; history=Chicago] or that is preferred by your professor. This section normally does not count towards the total page length of your research proposal.

Develop a Research Proposal: Writing the Proposal. Office of Library Information Services. Baltimore County Public Schools; Heath, M. Teresa Pereira and Caroline Tynan. “Crafting a Research Proposal.” The Marketing Review 10 (Summer 2010): 147-168; Jones, Mark. “Writing a Research Proposal.” In MasterClass in Geography Education: Transforming Teaching and Learning . Graham Butt, editor. (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015), pp. 113-127; Juni, Muhamad Hanafiah. “Writing a Research Proposal.” International Journal of Public Health and Clinical Sciences 1 (September/October 2014): 229-240; Krathwohl, David R. How to Prepare a Dissertation Proposal: Suggestions for Students in Education and the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2005; Procter, Margaret. The Academic Proposal. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Punch, Keith and Wayne McGowan. "Developing and Writing a Research Proposal." In From Postgraduate to Social Scientist: A Guide to Key Skills . Nigel Gilbert, ed. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2006), 59-81; Wong, Paul T. P. How to Write a Research Proposal. International Network on Personal Meaning. Trinity Western University; Writing Academic Proposals: Conferences , Articles, and Books. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing a Research Proposal. University Library. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- << Previous: Writing a Reflective Paper

- Next: Generative AI and Writing >>

- Last Updated: Jun 3, 2024 9:44 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

Published on October 12, 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on September 5, 2024.

A research proposal describes what you will investigate, why it’s important, and how you will conduct your research.

The format of a research proposal varies between fields, but most proposals will contain at least these elements:

Introduction

Literature review.

- Research design

Reference list

While the sections may vary, the overall objective is always the same. A research proposal serves as a blueprint and guide for your research plan, helping you get organized and feel confident in the path forward you choose to take.

Table of contents

Research proposal purpose, research proposal examples, research design and methods, contribution to knowledge, research schedule, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research proposals.

Academics often have to write research proposals to get funding for their projects. As a student, you might have to write a research proposal as part of a grad school application , or prior to starting your thesis or dissertation .

In addition to helping you figure out what your research can look like, a proposal can also serve to demonstrate why your project is worth pursuing to a funder, educational institution, or supervisor.

| Show your reader why your project is interesting, original, and important. | |

| Demonstrate your comfort and familiarity with your field. Show that you understand the current state of research on your topic. | |

| Make a case for your . Demonstrate that you have carefully thought about the data, tools, and procedures necessary to conduct your research. | |

| Confirm that your project is feasible within the timeline of your program or funding deadline. |

Research proposal length

The length of a research proposal can vary quite a bit. A bachelor’s or master’s thesis proposal can be just a few pages, while proposals for PhD dissertations or research funding are usually much longer and more detailed. Your supervisor can help you determine the best length for your work.

One trick to get started is to think of your proposal’s structure as a shorter version of your thesis or dissertation , only without the results , conclusion and discussion sections.

Download our research proposal template

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing a research proposal can be quite challenging, but a good starting point could be to look at some examples. We’ve included a few for you below.

- Example research proposal #1: “A Conceptual Framework for Scheduling Constraint Management”

- Example research proposal #2: “Medical Students as Mediators of Change in Tobacco Use”

Like your dissertation or thesis, the proposal will usually have a title page that includes:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- Your institution and department

The first part of your proposal is the initial pitch for your project. Make sure it succinctly explains what you want to do and why.

Your introduction should:

- Introduce your topic

- Give necessary background and context

- Outline your problem statement and research questions

To guide your introduction , include information about:

- Who could have an interest in the topic (e.g., scientists, policymakers)

- How much is already known about the topic

- What is missing from this current knowledge

- What new insights your research will contribute

- Why you believe this research is worth doing

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

As you get started, it’s important to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the most important research on your topic. A strong literature review shows your reader that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge or theory. It also shows that you’re not simply repeating what other people have already done or said, but rather using existing research as a jumping-off point for your own.

In this section, share exactly how your project will contribute to ongoing conversations in the field by:

- Comparing and contrasting the main theories, methods, and debates

- Examining the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches

- Explaining how will you build on, challenge, or synthesize prior scholarship

Following the literature review, restate your main objectives . This brings the focus back to your own project. Next, your research design or methodology section will describe your overall approach, and the practical steps you will take to answer your research questions.

| ? or ? , , or research design? | |

| , )? ? | |

| , , , )? | |

| ? |

To finish your proposal on a strong note, explore the potential implications of your research for your field. Emphasize again what you aim to contribute and why it matters.

For example, your results might have implications for:

- Improving best practices

- Informing policymaking decisions

- Strengthening a theory or model

- Challenging popular or scientific beliefs

- Creating a basis for future research

Last but not least, your research proposal must include correct citations for every source you have used, compiled in a reference list . To create citations quickly and easily, you can use our free APA citation generator .

Some institutions or funders require a detailed timeline of the project, asking you to forecast what you will do at each stage and how long it may take. While not always required, be sure to check the requirements of your project.

Here’s an example schedule to help you get started. You can also download a template at the button below.

Download our research schedule template

| Research phase | Objectives | Deadline |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Background research and literature review | 20th January | |

| 2. Research design planning | and data analysis methods | 13th February |

| 3. Data collection and preparation | with selected participants and code interviews | 24th March |

| 4. Data analysis | of interview transcripts | 22nd April |

| 5. Writing | 17th June | |

| 6. Revision | final work | 28th July |

If you are applying for research funding, chances are you will have to include a detailed budget. This shows your estimates of how much each part of your project will cost.

Make sure to check what type of costs the funding body will agree to cover. For each item, include:

- Cost : exactly how much money do you need?

- Justification : why is this cost necessary to complete the research?

- Source : how did you calculate the amount?

To determine your budget, think about:

- Travel costs : do you need to go somewhere to collect your data? How will you get there, and how much time will you need? What will you do there (e.g., interviews, archival research)?

- Materials : do you need access to any tools or technologies?

- Help : do you need to hire any research assistants for the project? What will they do, and how much will you pay them?

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Once you’ve decided on your research objectives , you need to explain them in your paper, at the end of your problem statement .

Keep your research objectives clear and concise, and use appropriate verbs to accurately convey the work that you will carry out for each one.

I will compare …

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

A PhD, which is short for philosophiae doctor (doctor of philosophy in Latin), is the highest university degree that can be obtained. In a PhD, students spend 3–5 years writing a dissertation , which aims to make a significant, original contribution to current knowledge.

A PhD is intended to prepare students for a career as a researcher, whether that be in academia, the public sector, or the private sector.

A master’s is a 1- or 2-year graduate degree that can prepare you for a variety of careers.

All master’s involve graduate-level coursework. Some are research-intensive and intend to prepare students for further study in a PhD; these usually require their students to write a master’s thesis . Others focus on professional training for a specific career.

Critical thinking refers to the ability to evaluate information and to be aware of biases or assumptions, including your own.

Like information literacy , it involves evaluating arguments, identifying and solving problems in an objective and systematic way, and clearly communicating your ideas.

The best way to remember the difference between a research plan and a research proposal is that they have fundamentally different audiences. A research plan helps you, the researcher, organize your thoughts. On the other hand, a dissertation proposal or research proposal aims to convince others (e.g., a supervisor, a funding body, or a dissertation committee) that your research topic is relevant and worthy of being conducted.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. & George, T. (2024, September 05). How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved September 18, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-proposal/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- Thesis Action Plan New

- Academic Project Planner

Literature Navigator

Thesis dialogue blueprint, writing wizard's template, research proposal compass.

- Why students love us

- Rebels Blog

- Why we are different

- All Products

- Coming Soon

How to Create an Effective Research Proposal PPT for Your Next Presentation

Creating an effective research proposal PPT can make a big difference in how your ideas are received. Whether you're a student or a professional, presenting your research clearly and engagingly is key to success. This guide will help you craft a presentation that stands out and communicates your message effectively.

Key Takeaways

- Understand the purpose and importance of a research proposal PPT.

- Structure your presentation with essential sections and a logical flow.

- Use design principles to create visually appealing slides.

- Craft clear and concise content to highlight key messages.

- Engage your audience with storytelling and interactive elements.

Understanding the Purpose of a Research Proposal PPT

A research proposal PPT serves as a visual tool to present your research plan effectively. It helps in outlining your research question , objectives, and methodology in a clear and concise manner. Crafting an effective PPT can significantly enhance your ability to communicate complex ideas to your audience.

Structuring Your Research Proposal PPT

Creating a well-structured research proposal PPT is crucial for effectively communicating your ideas. A clear structure ensures your audience can follow your argument easily.

Design Principles for an Effective Research Proposal PPT

Creating a visually appealing and effective research proposal PPT requires a keen understanding of design principles. Choosing the right template is crucial as it sets the tone for your presentation. Opt for a template that complements your research topic and is not overly distracting. When it comes to color schemes and fonts, consistency is key. Stick to a limited color palette and use readable fonts to ensure your audience can easily follow along. Incorporating visual aids, such as charts and graphs, can help illustrate your points more clearly. Remember, visuals should enhance your message, not overshadow it.

Crafting Compelling Content for Your Research Proposal PPT

Creating engaging content for your research proposal PPT is crucial for capturing your audience's attention. Clear and concise text is essential. Avoid jargon and keep your sentences short and to the point. Highlight the main ideas to ensure they stand out.

When emphasizing key messages, use bullet points or numbered lists. This makes your content easier to follow and digest. For instance, if you're explaining how to find good literature , break it down into simple steps:

- Identify your research question.

- Use academic databases.

- Evaluate sources for credibility.

Supporting your points with data is another effective strategy. Use tables to present structured information clearly. For example: