Home » Validity – Types, Examples and Guide

Validity – Types, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

Validity is a fundamental concept in research, referring to the extent to which a test, measurement, or study accurately reflects or assesses the specific concept that the researcher is attempting to measure. Ensuring validity is crucial as it determines the trustworthiness and credibility of the research findings.

Research Validity

Research validity pertains to the accuracy and truthfulness of the research. It examines whether the research truly measures what it claims to measure. Without validity, research results can be misleading or erroneous, leading to incorrect conclusions and potentially flawed applications.

How to Ensure Validity in Research

Ensuring validity in research involves several strategies:

- Clear Operational Definitions : Define variables clearly and precisely.

- Use of Reliable Instruments : Employ measurement tools that have been tested for reliability.

- Pilot Testing : Conduct preliminary studies to refine the research design and instruments.

- Triangulation : Use multiple methods or sources to cross-verify results.

- Control Variables : Control extraneous variables that might influence the outcomes.

Types of Validity

Validity is categorized into several types, each addressing different aspects of measurement accuracy.

Internal Validity

Internal validity refers to the degree to which the results of a study can be attributed to the treatments or interventions rather than other factors. It is about ensuring that the study is free from confounding variables that could affect the outcome.

External Validity

External validity concerns the extent to which the research findings can be generalized to other settings, populations, or times. High external validity means the results are applicable beyond the specific context of the study.

Construct Validity

Construct validity evaluates whether a test or instrument measures the theoretical construct it is intended to measure. It involves ensuring that the test is truly assessing the concept it claims to represent.

Content Validity

Content validity examines whether a test covers the entire range of the concept being measured. It ensures that the test items represent all facets of the concept.

Criterion Validity

Criterion validity assesses how well one measure predicts an outcome based on another measure. It is divided into two types:

- Predictive Validity : How well a test predicts future performance.

- Concurrent Validity : How well a test correlates with a currently existing measure.

Face Validity

Face validity refers to the extent to which a test appears to measure what it is supposed to measure, based on superficial inspection. While it is the least scientific measure of validity, it is important for ensuring that stakeholders believe in the test’s relevance.

Importance of Validity

Validity is crucial because it directly affects the credibility of research findings. Valid results ensure that conclusions drawn from research are accurate and can be trusted. This, in turn, influences the decisions and policies based on the research.

Examples of Validity

- Internal Validity : A randomized controlled trial (RCT) where the random assignment of participants helps eliminate biases.

- External Validity : A study on educational interventions that can be applied to different schools across various regions.

- Construct Validity : A psychological test that accurately measures depression levels.

- Content Validity : An exam that covers all topics taught in a course.

- Criterion Validity : A job performance test that predicts future job success.

Where to Write About Validity in A Thesis

In a thesis, the methodology section should include discussions about validity. Here, you explain how you ensured the validity of your research instruments and design. Additionally, you may discuss validity in the results section, interpreting how the validity of your measurements affects your findings.

Applications of Validity

Validity has wide applications across various fields:

- Education : Ensuring assessments accurately measure student learning.

- Psychology : Developing tests that correctly diagnose mental health conditions.

- Market Research : Creating surveys that accurately capture consumer preferences.

Limitations of Validity

While ensuring validity is essential, it has its limitations:

- Complexity : Achieving high validity can be complex and resource-intensive.

- Context-Specific : Some validity types may not be universally applicable across all contexts.

- Subjectivity : Certain types of validity, like face validity, involve subjective judgments.

By understanding and addressing these aspects of validity, researchers can enhance the quality and impact of their studies, leading to more reliable and actionable results.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

External Validity – Threats, Examples and Types

Construct Validity – Types, Threats and Examples

Reliability Vs Validity

Internal Consistency Reliability – Methods...

Alternate Forms Reliability – Methods, Examples...

Parallel Forms Reliability – Methods, Example...

Validity in research: a guide to measuring the right things

Last updated

27 February 2023

Reviewed by

Cathy Heath

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

Validity is necessary for all types of studies ranging from market validation of a business or product idea to the effectiveness of medical trials and procedures. So, how can you determine whether your research is valid? This guide can help you understand what validity is, the types of validity in research, and the factors that affect research validity.

Make research less tedious

Dovetail streamlines research to help you uncover and share actionable insights

In the most basic sense, validity is the quality of being based on truth or reason. Valid research strives to eliminate the effects of unrelated information and the circumstances under which evidence is collected.

Validity in research is the ability to conduct an accurate study with the right tools and conditions to yield acceptable and reliable data that can be reproduced. Researchers rely on carefully calibrated tools for precise measurements. However, collecting accurate information can be more of a challenge.

Studies must be conducted in environments that don't sway the results to achieve and maintain validity. They can be compromised by asking the wrong questions or relying on limited data.

Why is validity important in research?

Research is used to improve life for humans. Every product and discovery, from innovative medical breakthroughs to advanced new products, depends on accurate research to be dependable. Without it, the results couldn't be trusted, and products would likely fail. Businesses would lose money, and patients couldn't rely on medical treatments.

While wasting money on a lousy product is a concern, lack of validity paints a much grimmer picture in the medical field or producing automobiles and airplanes, for example. Whether you're launching an exciting new product or conducting scientific research, validity can determine success and failure.

Reliability is the ability of a method to yield consistency. If the same result can be consistently achieved by using the same method to measure something, the measurement method is said to be reliable. For example, a thermometer that shows the same temperatures each time in a controlled environment is reliable.

While high reliability is a part of measuring validity, it's only part of the puzzle. If the reliable thermometer hasn't been properly calibrated and reliably measures temperatures two degrees too high, it doesn't provide a valid (accurate) measure of temperature.

Similarly, if a researcher uses a thermometer to measure weight, the results won't be accurate because it's the wrong tool for the job.

- How are reliability and validity assessed?

While measuring reliability is a part of measuring validity, there are distinct ways to assess both measurements for accuracy.

How is reliability measured?

These measures of consistency and stability help assess reliability, including:

Consistency and stability of the same measure when repeated multiple times and conditions

Consistency and stability of the measure across different test subjects

Consistency and stability of results from different parts of a test designed to measure the same thing

How is validity measured?

Since validity refers to how accurately a method measures what it is intended to measure, it can be difficult to assess the accuracy. Validity can be estimated by comparing research results to other relevant data or theories.

The adherence of a measure to existing knowledge of how the concept is measured

The ability to cover all aspects of the concept being measured

The relation of the result in comparison with other valid measures of the same concept

- What are the types of validity in a research design?

Research validity is broadly gathered into two groups: internal and external. Yet, this grouping doesn't clearly define the different types of validity. Research validity can be divided into seven distinct groups.

Face validity : A test that appears valid simply because of the appropriateness or relativity of the testing method, included information, or tools used.

Content validity : The determination that the measure used in research covers the full domain of the content.

Construct validity : The assessment of the suitability of the measurement tool to measure the activity being studied.

Internal validity : The assessment of how your research environment affects measurement results. This is where other factors can’t explain the extent of an observed cause-and-effect response.

External validity : The extent to which the study will be accurate beyond the sample and the level to which it can be generalized in other settings, populations, and measures.

Statistical conclusion validity: The determination of whether a relationship exists between procedures and outcomes (appropriate sampling and measuring procedures along with appropriate statistical tests).

Criterion-related validity : A measurement of the quality of your testing methods against a criterion measure (like a “gold standard” test) that is measured at the same time.

Like different types of research and the various ways to measure validity, examples of validity can vary widely. These include:

A questionnaire may be considered valid because each question addresses specific and relevant aspects of the study subject.

In a brand assessment study, researchers can use comparison testing to verify the results of an initial study. For example, the results from a focus group response about brand perception are considered more valid when the results match that of a questionnaire answered by current and potential customers.

A test to measure a class of students' understanding of the English language contains reading, writing, listening, and speaking components to cover the full scope of how language is used.

- Factors that affect research validity

Certain factors can affect research validity in both positive and negative ways. By understanding the factors that improve validity and those that threaten it, you can enhance the validity of your study. These include:

Random selection of participants vs. the selection of participants that are representative of your study criteria

Blinding with interventions the participants are unaware of (like the use of placebos)

Manipulating the experiment by inserting a variable that will change the results

Randomly assigning participants to treatment and control groups to avoid bias

Following specific procedures during the study to avoid unintended effects

Conducting a study in the field instead of a laboratory for more accurate results

Replicating the study with different factors or settings to compare results

Using statistical methods to adjust for inconclusive data

What are the common validity threats in research, and how can their effects be minimized or nullified?

Research validity can be difficult to achieve because of internal and external threats that produce inaccurate results. These factors can jeopardize validity.

History: Events that occur between an early and later measurement

Maturation: The passage of time in a study can include data on actions that would have naturally occurred outside of the settings of the study

Repeated testing: The outcome of repeated tests can change the outcome of followed tests

Selection of subjects: Unconscious bias which can result in the selection of uniform comparison groups

Statistical regression: Choosing subjects based on extremes doesn't yield an accurate outcome for the majority of individuals

Attrition: When the sample group is diminished significantly during the course of the study

Maturation: When subjects mature during the study, and natural maturation is awarded to the effects of the study

While some validity threats can be minimized or wholly nullified, removing all threats from a study is impossible. For example, random selection can remove unconscious bias and statistical regression.

Researchers can even hope to avoid attrition by using smaller study groups. Yet, smaller study groups could potentially affect the research in other ways. The best practice for researchers to prevent validity threats is through careful environmental planning and t reliable data-gathering methods.

- How to ensure validity in your research

Researchers should be mindful of the importance of validity in the early planning stages of any study to avoid inaccurate results. Researchers must take the time to consider tools and methods as well as how the testing environment matches closely with the natural environment in which results will be used.

The following steps can be used to ensure validity in research:

Choose appropriate methods of measurement

Use appropriate sampling to choose test subjects

Create an accurate testing environment

How do you maintain validity in research?

Accurate research is usually conducted over a period of time with different test subjects. To maintain validity across an entire study, you must take specific steps to ensure that gathered data has the same levels of accuracy.

Consistency is crucial for maintaining validity in research. When researchers apply methods consistently and standardize the circumstances under which data is collected, validity can be maintained across the entire study.

Is there a need for validation of the research instrument before its implementation?

An essential part of validity is choosing the right research instrument or method for accurate results. Consider the thermometer that is reliable but still produces inaccurate results. You're unlikely to achieve research validity without activities like calibration, content, and construct validity.

- Understanding research validity for more accurate results

Without validity, research can't provide the accuracy necessary to deliver a useful study. By getting a clear understanding of validity in research, you can take steps to improve your research skills and achieve more accurate results.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 22 August 2024

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 August 2024

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 18, Issue 3

- Validity and reliability in quantitative studies

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Roberta Heale 1 ,

- Alison Twycross 2

- 1 School of Nursing, Laurentian University , Sudbury, Ontario , Canada

- 2 Faculty of Health and Social Care , London South Bank University , London , UK

- Correspondence to : Dr Roberta Heale, School of Nursing, Laurentian University, Ramsey Lake Road, Sudbury, Ontario, Canada P3E2C6; rheale{at}laurentian.ca

https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2015-102129

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Evidence-based practice includes, in part, implementation of the findings of well-conducted quality research studies. So being able to critique quantitative research is an important skill for nurses. Consideration must be given not only to the results of the study but also the rigour of the research. Rigour refers to the extent to which the researchers worked to enhance the quality of the studies. In quantitative research, this is achieved through measurement of the validity and reliability. 1

Types of validity

The first category is content validity . This category looks at whether the instrument adequately covers all the content that it should with respect to the variable. In other words, does the instrument cover the entire domain related to the variable, or construct it was designed to measure? In an undergraduate nursing course with instruction about public health, an examination with content validity would cover all the content in the course with greater emphasis on the topics that had received greater coverage or more depth. A subset of content validity is face validity , where experts are asked their opinion about whether an instrument measures the concept intended.

Construct validity refers to whether you can draw inferences about test scores related to the concept being studied. For example, if a person has a high score on a survey that measures anxiety, does this person truly have a high degree of anxiety? In another example, a test of knowledge of medications that requires dosage calculations may instead be testing maths knowledge.

There are three types of evidence that can be used to demonstrate a research instrument has construct validity:

Homogeneity—meaning that the instrument measures one construct.

Convergence—this occurs when the instrument measures concepts similar to that of other instruments. Although if there are no similar instruments available this will not be possible to do.

Theory evidence—this is evident when behaviour is similar to theoretical propositions of the construct measured in the instrument. For example, when an instrument measures anxiety, one would expect to see that participants who score high on the instrument for anxiety also demonstrate symptoms of anxiety in their day-to-day lives. 2

The final measure of validity is criterion validity . A criterion is any other instrument that measures the same variable. Correlations can be conducted to determine the extent to which the different instruments measure the same variable. Criterion validity is measured in three ways:

Convergent validity—shows that an instrument is highly correlated with instruments measuring similar variables.

Divergent validity—shows that an instrument is poorly correlated to instruments that measure different variables. In this case, for example, there should be a low correlation between an instrument that measures motivation and one that measures self-efficacy.

Predictive validity—means that the instrument should have high correlations with future criterions. 2 For example, a score of high self-efficacy related to performing a task should predict the likelihood a participant completing the task.

Reliability

Reliability relates to the consistency of a measure. A participant completing an instrument meant to measure motivation should have approximately the same responses each time the test is completed. Although it is not possible to give an exact calculation of reliability, an estimate of reliability can be achieved through different measures. The three attributes of reliability are outlined in table 2 . How each attribute is tested for is described below.

Attributes of reliability

Homogeneity (internal consistency) is assessed using item-to-total correlation, split-half reliability, Kuder-Richardson coefficient and Cronbach's α. In split-half reliability, the results of a test, or instrument, are divided in half. Correlations are calculated comparing both halves. Strong correlations indicate high reliability, while weak correlations indicate the instrument may not be reliable. The Kuder-Richardson test is a more complicated version of the split-half test. In this process the average of all possible split half combinations is determined and a correlation between 0–1 is generated. This test is more accurate than the split-half test, but can only be completed on questions with two answers (eg, yes or no, 0 or 1). 3

Cronbach's α is the most commonly used test to determine the internal consistency of an instrument. In this test, the average of all correlations in every combination of split-halves is determined. Instruments with questions that have more than two responses can be used in this test. The Cronbach's α result is a number between 0 and 1. An acceptable reliability score is one that is 0.7 and higher. 1 , 3

Stability is tested using test–retest and parallel or alternate-form reliability testing. Test–retest reliability is assessed when an instrument is given to the same participants more than once under similar circumstances. A statistical comparison is made between participant's test scores for each of the times they have completed it. This provides an indication of the reliability of the instrument. Parallel-form reliability (or alternate-form reliability) is similar to test–retest reliability except that a different form of the original instrument is given to participants in subsequent tests. The domain, or concepts being tested are the same in both versions of the instrument but the wording of items is different. 2 For an instrument to demonstrate stability there should be a high correlation between the scores each time a participant completes the test. Generally speaking, a correlation coefficient of less than 0.3 signifies a weak correlation, 0.3–0.5 is moderate and greater than 0.5 is strong. 4

Equivalence is assessed through inter-rater reliability. This test includes a process for qualitatively determining the level of agreement between two or more observers. A good example of the process used in assessing inter-rater reliability is the scores of judges for a skating competition. The level of consistency across all judges in the scores given to skating participants is the measure of inter-rater reliability. An example in research is when researchers are asked to give a score for the relevancy of each item on an instrument. Consistency in their scores relates to the level of inter-rater reliability of the instrument.

Determining how rigorously the issues of reliability and validity have been addressed in a study is an essential component in the critique of research as well as influencing the decision about whether to implement of the study findings into nursing practice. In quantitative studies, rigour is determined through an evaluation of the validity and reliability of the tools or instruments utilised in the study. A good quality research study will provide evidence of how all these factors have been addressed. This will help you to assess the validity and reliability of the research and help you decide whether or not you should apply the findings in your area of clinical practice.

- Lobiondo-Wood G ,

- Shuttleworth M

- ↵ Laerd Statistics . Determining the correlation coefficient . 2013 . https://statistics.laerd.com/premium/pc/pearson-correlation-in-spss-8.php

Twitter Follow Roberta Heale at @robertaheale and Alison Twycross at @alitwy

Competing interests None declared.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Validity & Reliability In Research

A Plain-Language Explanation (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Kerryn Warren (PhD) | September 2023

Validity and reliability are two related but distinctly different concepts within research. Understanding what they are and how to achieve them is critically important to any research project. In this post, we’ll unpack these two concepts as simply as possible.

This post is based on our popular online course, Research Methodology Bootcamp . In the course, we unpack the basics of methodology using straightfoward language and loads of examples. If you’re new to academic research, you definitely want to use this link to get 50% off the course (limited-time offer).

Overview: Validity & Reliability

- The big picture

- Validity 101

- Reliability 101

- Key takeaways

First, The Basics…

First, let’s start with a big-picture view and then we can zoom in to the finer details.

Validity and reliability are two incredibly important concepts in research, especially within the social sciences. Both validity and reliability have to do with the measurement of variables and/or constructs – for example, job satisfaction, intelligence, productivity, etc. When undertaking research, you’ll often want to measure these types of constructs and variables and, at the simplest level, validity and reliability are about ensuring the quality and accuracy of those measurements .

As you can probably imagine, if your measurements aren’t accurate or there are quality issues at play when you’re collecting your data, your entire study will be at risk. Therefore, validity and reliability are very important concepts to understand (and to get right). So, let’s unpack each of them.

What Is Validity?

In simple terms, validity (also called “construct validity”) is all about whether a research instrument accurately measures what it’s supposed to measure .

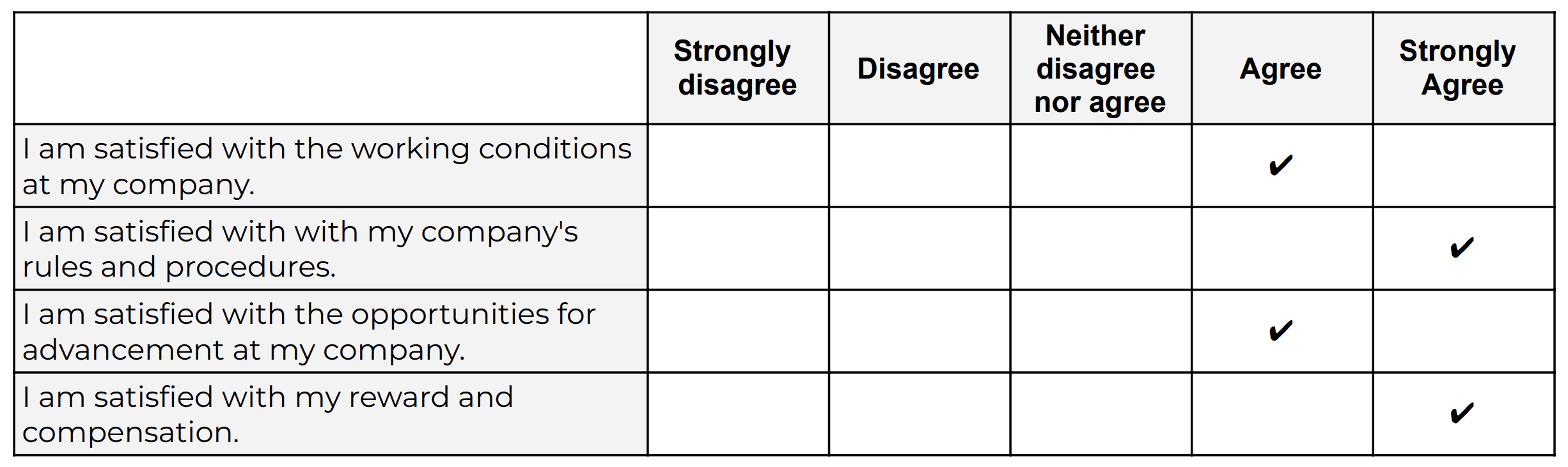

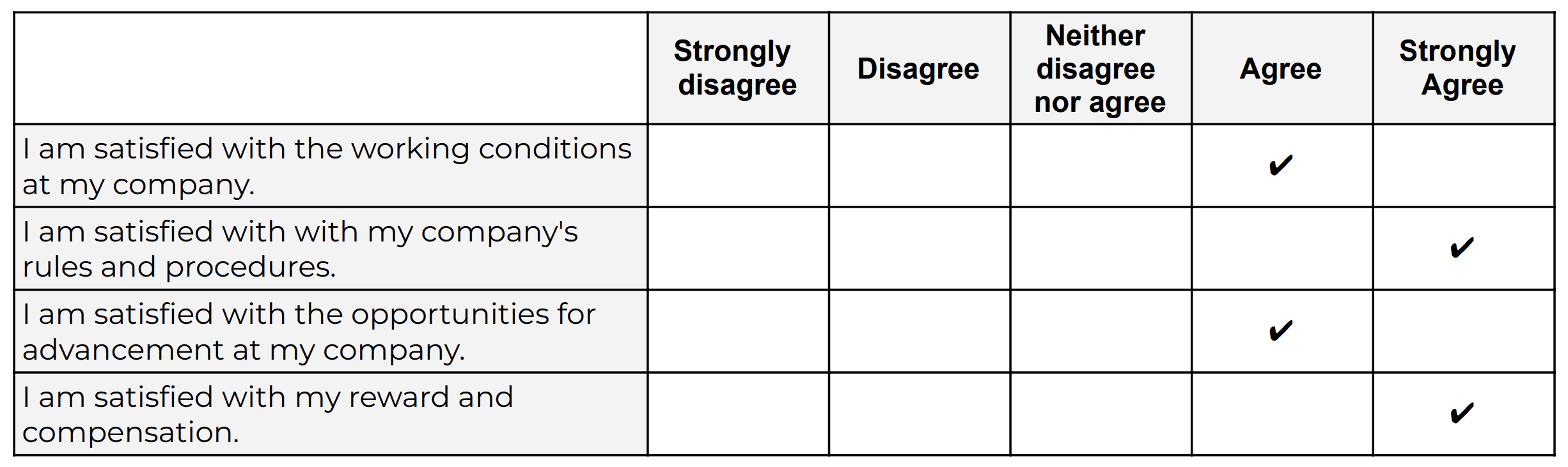

For example, let’s say you have a set of Likert scales that are supposed to quantify someone’s level of overall job satisfaction. If this set of scales focused purely on only one dimension of job satisfaction, say pay satisfaction, this would not be a valid measurement, as it only captures one aspect of the multidimensional construct. In other words, pay satisfaction alone is only one contributing factor toward overall job satisfaction, and therefore it’s not a valid way to measure someone’s job satisfaction.

Oftentimes in quantitative studies, the way in which the researcher or survey designer interprets a question or statement can differ from how the study participants interpret it . Given that respondents don’t have the opportunity to ask clarifying questions when taking a survey, it’s easy for these sorts of misunderstandings to crop up. Naturally, if the respondents are interpreting the question in the wrong way, the data they provide will be pretty useless . Therefore, ensuring that a study’s measurement instruments are valid – in other words, that they are measuring what they intend to measure – is incredibly important.

There are various types of validity and we’re not going to go down that rabbit hole in this post, but it’s worth quickly highlighting the importance of making sure that your research instrument is tightly aligned with the theoretical construct you’re trying to measure . In other words, you need to pay careful attention to how the key theories within your study define the thing you’re trying to measure – and then make sure that your survey presents it in the same way.

For example, sticking with the “job satisfaction” construct we looked at earlier, you’d need to clearly define what you mean by job satisfaction within your study (and this definition would of course need to be underpinned by the relevant theory). You’d then need to make sure that your chosen definition is reflected in the types of questions or scales you’re using in your survey . Simply put, you need to make sure that your survey respondents are perceiving your key constructs in the same way you are. Or, even if they’re not, that your measurement instrument is capturing the necessary information that reflects your definition of the construct at hand.

If all of this talk about constructs sounds a bit fluffy, be sure to check out Research Methodology Bootcamp , which will provide you with a rock-solid foundational understanding of all things methodology-related. Remember, you can take advantage of our 60% discount offer using this link.

Need a helping hand?

What Is Reliability?

As with validity, reliability is an attribute of a measurement instrument – for example, a survey, a weight scale or even a blood pressure monitor. But while validity is concerned with whether the instrument is measuring the “thing” it’s supposed to be measuring, reliability is concerned with consistency and stability . In other words, reliability reflects the degree to which a measurement instrument produces consistent results when applied repeatedly to the same phenomenon , under the same conditions .

As you can probably imagine, a measurement instrument that achieves a high level of consistency is naturally more dependable (or reliable) than one that doesn’t – in other words, it can be trusted to provide consistent measurements . And that, of course, is what you want when undertaking empirical research. If you think about it within a more domestic context, just imagine if you found that your bathroom scale gave you a different number every time you hopped on and off of it – you wouldn’t feel too confident in its ability to measure the variable that is your body weight 🙂

It’s worth mentioning that reliability also extends to the person using the measurement instrument . For example, if two researchers use the same instrument (let’s say a measuring tape) and they get different measurements, there’s likely an issue in terms of how one (or both) of them are using the measuring tape. So, when you think about reliability, consider both the instrument and the researcher as part of the equation.

As with validity, there are various types of reliability and various tests that can be used to assess the reliability of an instrument. A popular one that you’ll likely come across for survey instruments is Cronbach’s alpha , which is a statistical measure that quantifies the degree to which items within an instrument (for example, a set of Likert scales) measure the same underlying construct . In other words, Cronbach’s alpha indicates how closely related the items are and whether they consistently capture the same concept .

Recap: Key Takeaways

Alright, let’s quickly recap to cement your understanding of validity and reliability:

- Validity is concerned with whether an instrument (e.g., a set of Likert scales) is measuring what it’s supposed to measure

- Reliability is concerned with whether that measurement is consistent and stable when measuring the same phenomenon under the same conditions.

In short, validity and reliability are both essential to ensuring that your data collection efforts deliver high-quality, accurate data that help you answer your research questions . So, be sure to always pay careful attention to the validity and reliability of your measurement instruments when collecting and analysing data. As the adage goes, “rubbish in, rubbish out” – make sure that your data inputs are rock-solid.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Methodology Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

THE MATERIAL IS WONDERFUL AND BENEFICIAL TO ALL STUDENTS.

THE MATERIAL IS WONDERFUL AND BENEFICIAL TO ALL STUDENTS AND I HAVE GREATLY BENEFITED FROM THE CONTENT.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Statistics By Jim

Making statistics intuitive

Validity in Research and Psychology: Types & Examples

By Jim Frost 3 Comments

What is Validity in Psychology, Research, and Statistics?

Validity in research, statistics , psychology, and testing evaluates how well test scores reflect what they’re supposed to measure. Does the instrument measure what it claims to measure? Do the measurements reflect the underlying reality? Or do they quantify something else?

For example, does an intelligence test assess intelligence or another characteristic, such as education or the ability to recall facts?

Researchers need to consider whether they’re measuring what they think they’re measuring. Validity addresses the appropriateness of the data rather than whether measurements are repeatable ( reliability ). However, for a test to be valid, it must first be reliable (consistent).

Evaluating validity is crucial because it helps establish which tests to use and which to avoid. If researchers use the wrong instruments, their results can be meaningless!

Validity is usually less of a concern for tangible measurements like height and weight. You might have a cheap bathroom scale that tends to read too high or too low—but it still measures weight. For those types of measurements, you’re more interested in accuracy and precision . However, other types of measurements are not as straightforward.

Validity is often a more significant concern in psychology and the social sciences, where you measure intangible constructs such as self-esteem and positive outlook. If you’re assessing the psychological construct of conscientiousness, you need to ensure that the measurement instrument asks questions that evaluate this characteristic rather than, say, obedience.

Psychological assessments of unobservable latent constructs (e.g., intelligence, traits, abilities, proclivities, etc.) have a specific application known as test validity, which is the extent that theory and data support the interpretations of test scores. Consequently, it is a critical issue because it relates to understanding the test results.

Related post : Reliability vs Validity

Evaluating Validity

Researchers validate tests using different lines of evidence. An instrument can be strong for one type of validity but weaker for another. Consequently, it is not a black or white issue—it can have degrees.

In this vein, there are many different types of validity and ways of thinking about it. Let’s take a look at several of the more common types. Each kind is a line of evidence that can help support or refute a test’s overall validity. In this post, learn about face, content, criterion, discriminant, concurrent, predictive, and construct validity.

If you want to learn about experimental validity, read my post about internal and external validity . Those types relate to experimental design and methods.

Types of Validity

In this post, I cover the following seven types of validity:

- Face Validity : On its face, does the instrument measure the intended characteristic?

- Content Validity : Do the test items adequately evaluate the target topic?

- Criterion Validity : Do measures correlate with other measures in a pattern that fits theory?

- Discriminant Validity : Is there no correlation between measures that should not have a relationship?

- Concurrent Validity : Do simultaneous measures of the same construct correlate?

- Predictive Validity : Does the measure accurately predict outcomes?

- Construct Validity : Does the instrument measure the correct attribute?

Let’s look at these types of validity in more detail!

Face Validity

Face validity is the simplest and weakest type. Does the measurement instrument appear “on its face” to measure the intended construct? For a survey that assesses thrill-seeking behavior, you’d expect it to include questions about seeking excitement, getting bored quickly, and risky behaviors. If the survey contains these questions, then “on its face,” it seems like the instrument measures the construct that the researchers intend.

While this is a low bar, it’s an important issue to consider. Never overlook the obvious. Ensure that you understand the nature of the instrument and how it assesses a construct. Look at the questions. After all, if a test can’t clear this fundamental requirement, the other types of validity are a moot point. However, when a measure satisfies face validity, understand it is an intuition or a hunch that it feels correct. It’s not a statistical assessment. If your instrument passes this low bar, you still have more validation work ahead of you.

Content Validity

Content validity is similar to face validity—but it’s a more rigorous form. The process often involves assessing individual questions on a test and asking experts whether each item appraises the characteristics that the instrument is designed to cover. This process compares the test against the researcher’s goals and the theoretical properties of the construct. Researchers systematically determine whether each question contributes, and that no aspect is overlooked.

For example, if researchers are designing a survey to measure the attitudes and activities of thrill-seekers, they need to determine whether the questions sufficiently cover both of those aspects.

Learn more about Content Validity .

Criterion Validity

Criterion validity relates to the relationships between the variables in your dataset. If your data are valid, you’d expect to observe a particular correlation pattern between the variables. Researchers typically assess criterion validity by correlating different types of data. For whatever you’re measuring, you expect it to have particular relationships with other variables.

For example, measures of anxiety should correlate positively with the number of negative thoughts. Anxiety scores might also correlate positively with depression and eating disorders. If we see this pattern of relationships, it supports criterion validity. Our measure for anxiety correlates with other variables as expected.

This type is also known as convergent validity because scores for different measures converge or correspond as theory suggests. You should observe high correlations (either positive or negative).

Related posts : Criterion Validity: Definition, Assessing, and Examples and Interpreting Correlation Coefficients

Discriminant Validity

This type is the opposite of criterion validity. If you have valid data, you expect particular pairs of variables to correlate positively or negatively. However, for other pairs of variables, you expect no relationship.

For example, if self-esteem and locus of control are not related in reality, their measures should not correlate. You should observe a low correlation between scores.

It is also known as divergent validity because it relates to how different constructs are differentiated. Low correlations (close to zero) indicate that the values of one variable do not relate to the values of the other variables—the measures distinguish between different constructs.

Concurrent Validity

Concurrent validity evaluates the degree to which a measure of a construct correlates with other simultaneous measures of that construct. For example, if you administer two different intelligence tests to the same group, there should be a strong, positive correlation between their scores.

Learn more about Concurrent Validity: Definition, Assessing and Examples .

Predictive Validity

Predictive validity evaluates how well a construct predicts an outcome. For example, standardized tests such as the SAT and ACT are intended to predict how high school students will perform in college. If these tests have high predictive ability, test scores will have a strong, positive correlation with college achievement. Testing this type of validity requires administering the assessment and then measuring the actual outcomes.

Learn more about Predictive Validity: Definition, Assessing and Examples .

Construct Validity

A test with high construct validity correctly fits into the big picture with other constructs. Consequently, this type incorporates aspects of criterion, discriminant, concurrent, and predictive validity. A construct must correlate positively and negatively with the theoretically appropriate constructs, have no correlation with the correct constructs, correlate with other measures of the same construct, etc.

Construct validity combines the theoretical relationships between constructs with empirical relationships to see how closely they align. It evaluates the full range of characteristics for the construct you’re measuring and determines whether they all correlate correctly with other constructs, behaviors, and events.

As you can see, validity is a complex issue, particularly when you’re measuring abstract characteristics. To properly validate a test, you need to incorporate a wide range of subject-area knowledge and determine whether the measurements from your instrument fit in with the bigger picture! Researchers often use factor analysis to assess construct validity. Learn more about Factor Analysis .

For more in-depth information, read my article about Construct Validity .

Learn more about Experimental Design: Definition, Types, and Examples .

Nevo, Baruch (1985), Face Validity Revisited , Journal of Educational Measurement.

Share this:

Reader Interactions

April 21, 2022 at 12:05 am

Thank you for the examples and easy-to-understand information about the various types of statistics used in psychology. As a current Ph.D. student, I have struggled in this area and finally, understand how to research using Inter-Rater Reliability and Predictive Validity. I greatly appreciate the information you are sharing and hope you continue to share information and examples that allows anyone, regardless of degree or not, an easy way to grasp the material.

April 21, 2022 at 1:38 am

Thanks so much! I really appreciate your kind words and I’m so glad my content has been helpful. I’m going to keep sharing! 🙂

March 14, 2023 at 1:27 am

Indeed! I think I’m grasping the concept reading your contents. Thanks!

Comments and Questions Cancel reply

17.4.1 Validity of instruments

Validity has to do with whether the instrument is measuring what it is intended to measure. Empirical evidence that PROs measure the domains of interest allows strong inferences regarding validity. To provide such evidence, investigators have borrowed validation strategies from psychologists who for many years have struggled with determining whether questionnaires assessing intelligence and attitudes really measure what is intended.

Validation strategies include:

content-related: evidence that the items and domains of an instrument are appropriate and comprehensive relative to its intended measurement concept(s), population and use;

construct-related: evidence that relationships among items, domains, and concepts conform to a priori hypotheses concerning logical relationships that should exist with other measures or characteristics of patients and patient groups; and

criterion-related (for a PRO instrument used as diagnostic tool): the extent to which the scores of a PRO instrument are related to a criterion measure.

Establishing validity involves examining the logical relationships that should exist between assessment measures. For example, we would expect that patients with lower treadmill exercise capacity generally will have more shortness of breath in daily life than those with higher exercise capacity, and we would expect to see substantial correlations between a new measure of emotional function and existing emotional function questionnaires.

When we are interested in evaluating change over time, we examine correlations of change scores. For example, patients who deteriorate in their treadmill exercise capacity should, in general, show increases in dyspnoea, whereas those whose exercise capacity improves should experience less dyspnoea. Similarly, a new emotional function measure should show improvement in patients who improve on existing measures of emotional function. The technical term for this process is testing an instrument’s construct validity.

Review authors should look for, and evaluate the evidence of, the validity of PROs used in their included studies. Unfortunately, reports of randomized trials and other studies using PROs seldom review evidence of the validity of the instruments they use, but review authors can gain some reassurance from statements (backed by citations) that the questionnaires have been validated previously.

A final concern about validity arises if the measurement instrument is used with a different population, or in a culturally and linguistically different environment, than the one in which it was developed (typically, use of a non-English version of an English-language questionnaire). Ideally, one would have evidence of validity in the population enrolled in the randomized trial. Ideally PRO measures should be re-validated in each study using whatever data are available for the validation, for instance, other endpoints measured. Authors should note, in evaluating evidence of validity, when the population assessed in the trial is different from that used in validation studies.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 5: Psychological Measurement

Reliability and Validity of Measurement

Learning Objectives

- Define reliability, including the different types and how they are assessed.

- Define validity, including the different types and how they are assessed.

- Describe the kinds of evidence that would be relevant to assessing the reliability and validity of a particular measure.

Again, measurement involves assigning scores to individuals so that they represent some characteristic of the individuals. But how do researchers know that the scores actually represent the characteristic, especially when it is a construct like intelligence, self-esteem, depression, or working memory capacity? The answer is that they conduct research using the measure to confirm that the scores make sense based on their understanding of the construct being measured. This is an extremely important point. Psychologists do not simply assume that their measures work. Instead, they collect data to demonstrate that they work. If their research does not demonstrate that a measure works, they stop using it.

As an informal example, imagine that you have been dieting for a month. Your clothes seem to be fitting more loosely, and several friends have asked if you have lost weight. If at this point your bathroom scale indicated that you had lost 10 pounds, this would make sense and you would continue to use the scale. But if it indicated that you had gained 10 pounds, you would rightly conclude that it was broken and either fix it or get rid of it. In evaluating a measurement method, psychologists consider two general dimensions: reliability and validity.

Reliability

Reliability refers to the consistency of a measure. Psychologists consider three types of consistency: over time (test-retest reliability), across items (internal consistency), and across different researchers (inter-rater reliability).

Test-Retest Reliability

When researchers measure a construct that they assume to be consistent across time, then the scores they obtain should also be consistent across time. Test-retest reliability is the extent to which this is actually the case. For example, intelligence is generally thought to be consistent across time. A person who is highly intelligent today will be highly intelligent next week. This means that any good measure of intelligence should produce roughly the same scores for this individual next week as it does today. Clearly, a measure that produces highly inconsistent scores over time cannot be a very good measure of a construct that is supposed to be consistent.

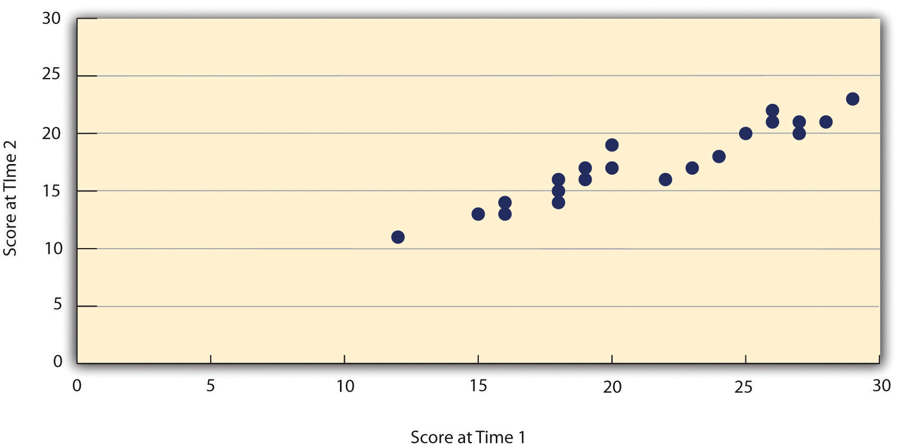

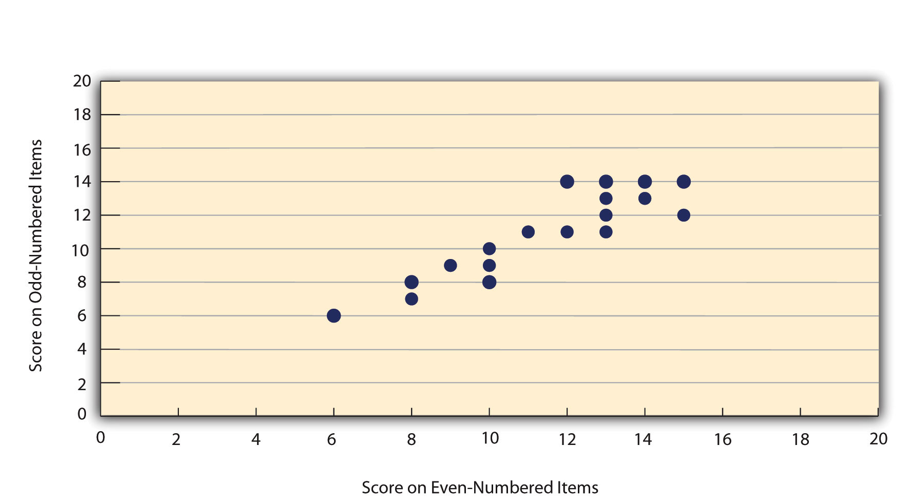

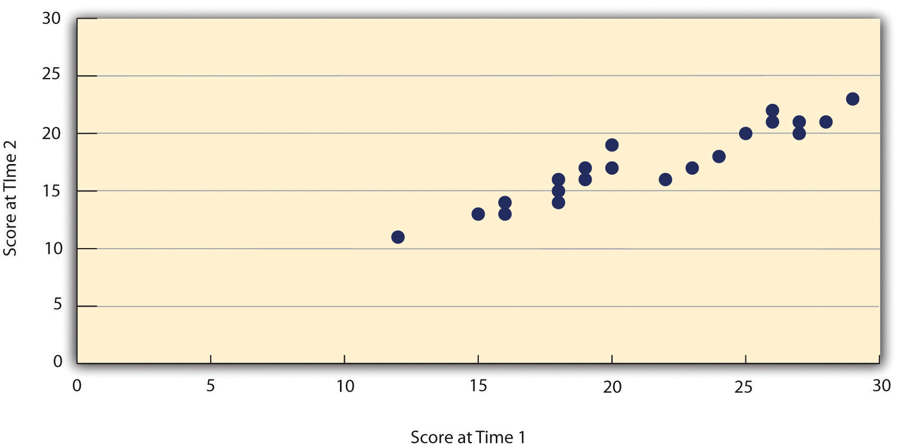

Assessing test-retest reliability requires using the measure on a group of people at one time, using it again on the same group of people at a later time, and then looking at test-retest correlation between the two sets of scores. This is typically done by graphing the data in a scatterplot and computing Pearson’s r . Figure 5.2 shows the correlation between two sets of scores of several university students on the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, administered two times, a week apart. Pearson’s r for these data is +.95. In general, a test-retest correlation of +.80 or greater is considered to indicate good reliability.

Again, high test-retest correlations make sense when the construct being measured is assumed to be consistent over time, which is the case for intelligence, self-esteem, and the Big Five personality dimensions. But other constructs are not assumed to be stable over time. The very nature of mood, for example, is that it changes. So a measure of mood that produced a low test-retest correlation over a period of a month would not be a cause for concern.

Internal Consistency

A second kind of reliability is internal consistency , which is the consistency of people’s responses across the items on a multiple-item measure. In general, all the items on such measures are supposed to reflect the same underlying construct, so people’s scores on those items should be correlated with each other. On the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, people who agree that they are a person of worth should tend to agree that that they have a number of good qualities. If people’s responses to the different items are not correlated with each other, then it would no longer make sense to claim that they are all measuring the same underlying construct. This is as true for behavioural and physiological measures as for self-report measures. For example, people might make a series of bets in a simulated game of roulette as a measure of their level of risk seeking. This measure would be internally consistent to the extent that individual participants’ bets were consistently high or low across trials.

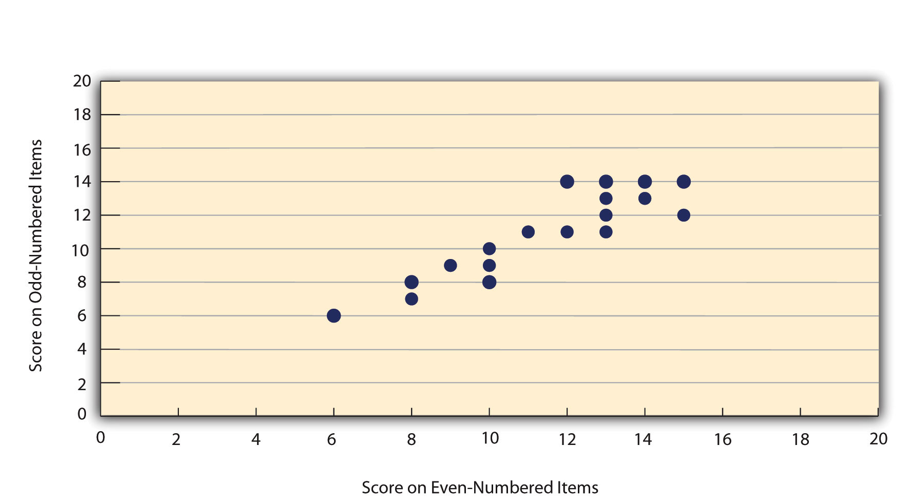

Like test-retest reliability, internal consistency can only be assessed by collecting and analyzing data. One approach is to look at a split-half correlation . This involves splitting the items into two sets, such as the first and second halves of the items or the even- and odd-numbered items. Then a score is computed for each set of items, and the relationship between the two sets of scores is examined. For example, Figure 5.3 shows the split-half correlation between several university students’ scores on the even-numbered items and their scores on the odd-numbered items of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Pearson’s r for these data is +.88. A split-half correlation of +.80 or greater is generally considered good internal consistency.

Perhaps the most common measure of internal consistency used by researchers in psychology is a statistic called Cronbach’s α (the Greek letter alpha). Conceptually, α is the mean of all possible split-half correlations for a set of items. For example, there are 252 ways to split a set of 10 items into two sets of five. Cronbach’s α would be the mean of the 252 split-half correlations. Note that this is not how α is actually computed, but it is a correct way of interpreting the meaning of this statistic. Again, a value of +.80 or greater is generally taken to indicate good internal consistency.

Interrater Reliability

Many behavioural measures involve significant judgment on the part of an observer or a rater. Inter-rater reliability is the extent to which different observers are consistent in their judgments. For example, if you were interested in measuring university students’ social skills, you could make video recordings of them as they interacted with another student whom they are meeting for the first time. Then you could have two or more observers watch the videos and rate each student’s level of social skills. To the extent that each participant does in fact have some level of social skills that can be detected by an attentive observer, different observers’ ratings should be highly correlated with each other. Inter-rater reliability would also have been measured in Bandura’s Bobo doll study. In this case, the observers’ ratings of how many acts of aggression a particular child committed while playing with the Bobo doll should have been highly positively correlated. Interrater reliability is often assessed using Cronbach’s α when the judgments are quantitative or an analogous statistic called Cohen’s κ (the Greek letter kappa) when they are categorical.

Validity is the extent to which the scores from a measure represent the variable they are intended to. But how do researchers make this judgment? We have already considered one factor that they take into account—reliability. When a measure has good test-retest reliability and internal consistency, researchers should be more confident that the scores represent what they are supposed to. There has to be more to it, however, because a measure can be extremely reliable but have no validity whatsoever. As an absurd example, imagine someone who believes that people’s index finger length reflects their self-esteem and therefore tries to measure self-esteem by holding a ruler up to people’s index fingers. Although this measure would have extremely good test-retest reliability, it would have absolutely no validity. The fact that one person’s index finger is a centimetre longer than another’s would indicate nothing about which one had higher self-esteem.

Discussions of validity usually divide it into several distinct “types.” But a good way to interpret these types is that they are other kinds of evidence—in addition to reliability—that should be taken into account when judging the validity of a measure. Here we consider three basic kinds: face validity, content validity, and criterion validity.

Face Validity

Face validity is the extent to which a measurement method appears “on its face” to measure the construct of interest. Most people would expect a self-esteem questionnaire to include items about whether they see themselves as a person of worth and whether they think they have good qualities. So a questionnaire that included these kinds of items would have good face validity. The finger-length method of measuring self-esteem, on the other hand, seems to have nothing to do with self-esteem and therefore has poor face validity. Although face validity can be assessed quantitatively—for example, by having a large sample of people rate a measure in terms of whether it appears to measure what it is intended to—it is usually assessed informally.

Face validity is at best a very weak kind of evidence that a measurement method is measuring what it is supposed to. One reason is that it is based on people’s intuitions about human behaviour, which are frequently wrong. It is also the case that many established measures in psychology work quite well despite lacking face validity. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2) measures many personality characteristics and disorders by having people decide whether each of over 567 different statements applies to them—where many of the statements do not have any obvious relationship to the construct that they measure. For example, the items “I enjoy detective or mystery stories” and “The sight of blood doesn’t frighten me or make me sick” both measure the suppression of aggression. In this case, it is not the participants’ literal answers to these questions that are of interest, but rather whether the pattern of the participants’ responses to a series of questions matches those of individuals who tend to suppress their aggression.

Content Validity

Content validity is the extent to which a measure “covers” the construct of interest. For example, if a researcher conceptually defines test anxiety as involving both sympathetic nervous system activation (leading to nervous feelings) and negative thoughts, then his measure of test anxiety should include items about both nervous feelings and negative thoughts. Or consider that attitudes are usually defined as involving thoughts, feelings, and actions toward something. By this conceptual definition, a person has a positive attitude toward exercise to the extent that he or she thinks positive thoughts about exercising, feels good about exercising, and actually exercises. So to have good content validity, a measure of people’s attitudes toward exercise would have to reflect all three of these aspects. Like face validity, content validity is not usually assessed quantitatively. Instead, it is assessed by carefully checking the measurement method against the conceptual definition of the construct.

Criterion Validity

Criterion validity is the extent to which people’s scores on a measure are correlated with other variables (known as criteria ) that one would expect them to be correlated with. For example, people’s scores on a new measure of test anxiety should be negatively correlated with their performance on an important school exam. If it were found that people’s scores were in fact negatively correlated with their exam performance, then this would be a piece of evidence that these scores really represent people’s test anxiety. But if it were found that people scored equally well on the exam regardless of their test anxiety scores, then this would cast doubt on the validity of the measure.

A criterion can be any variable that one has reason to think should be correlated with the construct being measured, and there will usually be many of them. For example, one would expect test anxiety scores to be negatively correlated with exam performance and course grades and positively correlated with general anxiety and with blood pressure during an exam. Or imagine that a researcher develops a new measure of physical risk taking. People’s scores on this measure should be correlated with their participation in “extreme” activities such as snowboarding and rock climbing, the number of speeding tickets they have received, and even the number of broken bones they have had over the years. When the criterion is measured at the same time as the construct, criterion validity is referred to as concurrent validity ; however, when the criterion is measured at some point in the future (after the construct has been measured), it is referred to as predictive validity (because scores on the measure have “predicted” a future outcome).

Criteria can also include other measures of the same construct. For example, one would expect new measures of test anxiety or physical risk taking to be positively correlated with existing measures of the same constructs. This is known as convergent validity .

Assessing convergent validity requires collecting data using the measure. Researchers John Cacioppo and Richard Petty did this when they created their self-report Need for Cognition Scale to measure how much people value and engage in thinking (Cacioppo & Petty, 1982) [1] . In a series of studies, they showed that people’s scores were positively correlated with their scores on a standardized academic achievement test, and that their scores were negatively correlated with their scores on a measure of dogmatism (which represents a tendency toward obedience). In the years since it was created, the Need for Cognition Scale has been used in literally hundreds of studies and has been shown to be correlated with a wide variety of other variables, including the effectiveness of an advertisement, interest in politics, and juror decisions (Petty, Briñol, Loersch, & McCaslin, 2009) [2] .

Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity , on the other hand, is the extent to which scores on a measure are not correlated with measures of variables that are conceptually distinct. For example, self-esteem is a general attitude toward the self that is fairly stable over time. It is not the same as mood, which is how good or bad one happens to be feeling right now. So people’s scores on a new measure of self-esteem should not be very highly correlated with their moods. If the new measure of self-esteem were highly correlated with a measure of mood, it could be argued that the new measure is not really measuring self-esteem; it is measuring mood instead.

When they created the Need for Cognition Scale, Cacioppo and Petty also provided evidence of discriminant validity by showing that people’s scores were not correlated with certain other variables. For example, they found only a weak correlation between people’s need for cognition and a measure of their cognitive style—the extent to which they tend to think analytically by breaking ideas into smaller parts or holistically in terms of “the big picture.” They also found no correlation between people’s need for cognition and measures of their test anxiety and their tendency to respond in socially desirable ways. All these low correlations provide evidence that the measure is reflecting a conceptually distinct construct.

Key Takeaways

- Psychological researchers do not simply assume that their measures work. Instead, they conduct research to show that they work. If they cannot show that they work, they stop using them.

- There are two distinct criteria by which researchers evaluate their measures: reliability and validity. Reliability is consistency across time (test-retest reliability), across items (internal consistency), and across researchers (interrater reliability). Validity is the extent to which the scores actually represent the variable they are intended to.

- Validity is a judgment based on various types of evidence. The relevant evidence includes the measure’s reliability, whether it covers the construct of interest, and whether the scores it produces are correlated with other variables they are expected to be correlated with and not correlated with variables that are conceptually distinct.

- The reliability and validity of a measure is not established by any single study but by the pattern of results across multiple studies. The assessment of reliability and validity is an ongoing process.

- Practice: Ask several friends to complete the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Then assess its internal consistency by making a scatterplot to show the split-half correlation (even- vs. odd-numbered items). Compute Pearson’s r too if you know how.

- Discussion: Think back to the last college exam you took and think of the exam as a psychological measure. What construct do you think it was intended to measure? Comment on its face and content validity. What data could you collect to assess its reliability and criterion validity?

- Cacioppo, J. T., & Petty, R. E. (1982). The need for cognition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42 , 116–131. ↵

- Petty, R. E, Briñol, P., Loersch, C., & McCaslin, M. J. (2009). The need for cognition. In M. R. Leary & R. H. Hoyle (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behaviour (pp. 318–329). New York, NY: Guilford Press. ↵

The consistency of a measure.

The consistency of a measure over time.

The consistency of a measure on the same group of people at different times.

Consistency of people’s responses across the items on a multiple-item measure.

Method of assessing internal consistency through splitting the items into two sets and examining the relationship between them.

A statistic in which α is the mean of all possible split-half correlations for a set of items.

The extent to which different observers are consistent in their judgments.

The extent to which the scores from a measure represent the variable they are intended to.

The extent to which a measurement method appears to measure the construct of interest.

The extent to which a measure “covers” the construct of interest.

The extent to which people’s scores on a measure are correlated with other variables that one would expect them to be correlated with.

In reference to criterion validity, variables that one would expect to be correlated with the measure.

When the criterion is measured at the same time as the construct.

when the criterion is measured at some point in the future (after the construct has been measured).

When new measures positively correlate with existing measures of the same constructs.

The extent to which scores on a measure are not correlated with measures of variables that are conceptually distinct.

Research Methods in Psychology - 2nd Canadian Edition Copyright © 2015 by Paul C. Price, Rajiv Jhangiani, & I-Chant A. Chiang is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Validity and Reliability of the Research Instrument; How to Test the Validation of a Questionnaire/Survey in a Research

9 Pages Posted: 31 Jul 2018

Hamed Taherdoost

Hamta Group

Date Written: August 10, 2016

Questionnaire is one of the most widely used tools to collect data in especially social science research. The main objective of questionnaire in research is to obtain relevant information in most reliable and valid manner. Thus the accuracy and consistency of survey/questionnaire forms a significant aspect of research methodology which are known as validity and reliability. Often new researchers are confused with selection and conducting of proper validity type to test their research instrument (questionnaire/survey). This review article explores and describes the validity and reliability of a questionnaire/survey and also discusses various forms of validity and reliability tests.

Keywords: Research Instrument, Questionnaire, Survey, Survey Validity, Questionnaire Reliability, Content Validity, Face Validity, Construct Validity, Criterion Validity

Suggested Citation: Suggested Citation

Hamed Taherdoost (Contact Author)

Hamta group ( email ).

Vancouver Canada

Do you have a job opening that you would like to promote on SSRN?

Paper statistics, related ejournals, social sciences education ejournal.

Subscribe to this fee journal for more curated articles on this topic

Political Behavior: Voting & Public Opinion eJournal

Political methods: experiments & experimental design ejournal.

Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

Neag School of Education

Educational Research Basics by Del Siegle

Instrument validity.

Validity (a concept map shows the various types of validity) A instrument is valid only to the extent that it’s scores permits appropriate inferences to be made about 1) a specific group of people for 2) specific purposes.

An instrument that is a valid measure of third grader’s math skills probably is not a valid measure of high school calculus student’s math skills. An instrument that is a valid predictor of how well students might do in school, may not be a valid measure of how well they will do once they complete school. So we never say that an instrument is valid or not valid…we say it is valid for a specific purpose with a specific group of people. Validity is specific to the appropriateness of the interpretations we wish to make with the scores.

In the reliability section , we discussed a scale that consistently reported a weight of 15 pounds for someone. While it may be a reliable instrument, it is not a valid instrument to determine someone’s weight in pounds. Just as a measuring tape is a valid instrument to determine people’s height, it is not a valid instrument to determine their weight.

There are three general categories of instrument validity. Content-Related Evidence (also known as Face Validity) Specialists in the content measured by the instrument are asked to judge the appropriateness of the items on the instrument. Do they cover the breath of the content area (does the instrument contain a representative sample of the content being assessed)? Are they in a format that is appropriate for those using the instrument? A test that is intended to measure the quality of science instruction in fifth grade, should cover material covered in the fifth grade science course in a manner appropriate for fifth graders. A national science test might not be a valid measure of local science instruction, although it might be a valid measure of national science standards.

Criterion-Related Evidence Criterion-related evidence is collected by comparing the instrument with some future or current criteria, thus the name criterion-related. The purpose of an instrument dictates whether predictive or concurrent validity is warranted.

– Predictive Validity If an instrument is purported to measure some future performance, predictive validity should be investigated. A comparison must be made between the instrument and some later behavior that it predicts. Suppose a screening test for 5-year-olds is purported to predict success in kindergarten. To investigate predictive validity, one would give the prescreening instrument to 5-year-olds prior to their entry into kindergarten. The children’s kindergarten performance would be assessed at the end of kindergarten and a correlation would be calculated between the screening instrument scores and the kindergarten performance scores.

– Concurrent Validity Concurrent validity compares scores on an instrument with current performance on some other measure. Unlike predictive validity, where the second measurement occurs later, concurrent validity requires a second measure at about the same time. Concurrent validity for a science test could be investigated by correlating scores for the test with scores from another established science test taken about the same time. Another way is to administer the instrument to two groups who are known to differ on the trait being measured by the instrument. One would have support for concurrent validity if the scores for the two groups were very different. An instrument that measures altruism should be able to discriminate those who possess it (nuns) from those who don’t (homicidal maniacs). One would expect the nuns to score significantly higher on the instrument.

Construct-Related Evidence Construct validity is an on-going process. Please refer to pages 174-176 for more information. Construct validity will not be on the test.

– Discriminant Validity An instrument does not correlate significantly with variables from which it should differ.

– Convergent Validity An instrument correlates highly with other variables with which it should theoretically correlate.

Del Siegle, Ph.D. Neag School of Education – University of Connecticut [email protected] www.delsiegle.info

Reliability and Validity – Definitions, Types & Examples

Published by Alvin Nicolas at August 16th, 2021 , Revised On October 26, 2023

A researcher must test the collected data before making any conclusion. Every research design needs to be concerned with reliability and validity to measure the quality of the research.

What is Reliability?

Reliability refers to the consistency of the measurement. Reliability shows how trustworthy is the score of the test. If the collected data shows the same results after being tested using various methods and sample groups, the information is reliable. If your method has reliability, the results will be valid.

Example: If you weigh yourself on a weighing scale throughout the day, you’ll get the same results. These are considered reliable results obtained through repeated measures.

Example: If a teacher conducts the same math test of students and repeats it next week with the same questions. If she gets the same score, then the reliability of the test is high.

What is the Validity?

Validity refers to the accuracy of the measurement. Validity shows how a specific test is suitable for a particular situation. If the results are accurate according to the researcher’s situation, explanation, and prediction, then the research is valid.

If the method of measuring is accurate, then it’ll produce accurate results. If a method is reliable, then it’s valid. In contrast, if a method is not reliable, it’s not valid.

Example: Your weighing scale shows different results each time you weigh yourself within a day even after handling it carefully, and weighing before and after meals. Your weighing machine might be malfunctioning. It means your method had low reliability. Hence you are getting inaccurate or inconsistent results that are not valid.

Example: Suppose a questionnaire is distributed among a group of people to check the quality of a skincare product and repeated the same questionnaire with many groups. If you get the same response from various participants, it means the validity of the questionnaire and product is high as it has high reliability.

Most of the time, validity is difficult to measure even though the process of measurement is reliable. It isn’t easy to interpret the real situation.

Example: If the weighing scale shows the same result, let’s say 70 kg each time, even if your actual weight is 55 kg, then it means the weighing scale is malfunctioning. However, it was showing consistent results, but it cannot be considered as reliable. It means the method has low reliability.

Internal Vs. External Validity

One of the key features of randomised designs is that they have significantly high internal and external validity.

Internal validity is the ability to draw a causal link between your treatment and the dependent variable of interest. It means the observed changes should be due to the experiment conducted, and any external factor should not influence the variables .

Example: age, level, height, and grade.

External validity is the ability to identify and generalise your study outcomes to the population at large. The relationship between the study’s situation and the situations outside the study is considered external validity.

Also, read about Inductive vs Deductive reasoning in this article.

Looking for reliable dissertation support?

We hear you.

- Whether you want a full dissertation written or need help forming a dissertation proposal, we can help you with both.

- Get different dissertation services at ResearchProspect and score amazing grades!

Threats to Interval Validity

| Threat | Definition | Example |

| Confounding factors | Unexpected events during the experiment that are not a part of treatment. | If you feel the increased weight of your experiment participants is due to lack of physical activity, but it was actually due to the consumption of coffee with sugar. |

| Maturation | The influence on the independent variable due to passage of time. | During a long-term experiment, subjects may feel tired, bored, and hungry. |

| Testing | The results of one test affect the results of another test. | Participants of the first experiment may react differently during the second experiment. |

| Instrumentation | Changes in the instrument’s collaboration | Change in the may give different results instead of the expected results. |

| Statistical regression | Groups selected depending on the extreme scores are not as extreme on subsequent testing. | Students who failed in the pre-final exam are likely to get passed in the final exams; they might be more confident and conscious than earlier. |

| Selection bias | Choosing comparison groups without randomisation. | A group of trained and efficient teachers is selected to teach children communication skills instead of randomly selecting them. |

| Experimental mortality | Due to the extension of the time of the experiment, participants may leave the experiment. | Due to multi-tasking and various competition levels, the participants may leave the competition because they are dissatisfied with the time-extension even if they were doing well. |

Threats of External Validity

| Threat | Definition | Example |