Get 25% OFF new yearly plans in our Storyteller's Sale

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Critique Report

- Writing Reports

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

How to Write Dialogue: 7 Great Tips for Writers (With Examples)

By Hannah Yang

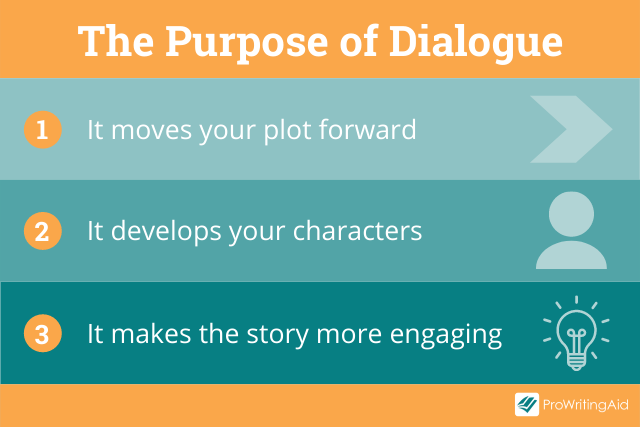

Great dialogue serves multiple purposes. It moves your plot forward. It develops your characters and it makes the story more engaging.

It’s not easy to do all these things at once, but when you master the art of writing dialogue, readers won’t be able to put your book down.

In this article, we will teach you the rules for writing dialogue and share our top dialogue tips that will make your story sing.

Dialogue Rules

How to format dialogue, 7 tips for writing dialogue in a story or book, dialogue examples.

Before we look at tips for writing powerful dialogue , let’s start with an overview of basic dialogue rules.

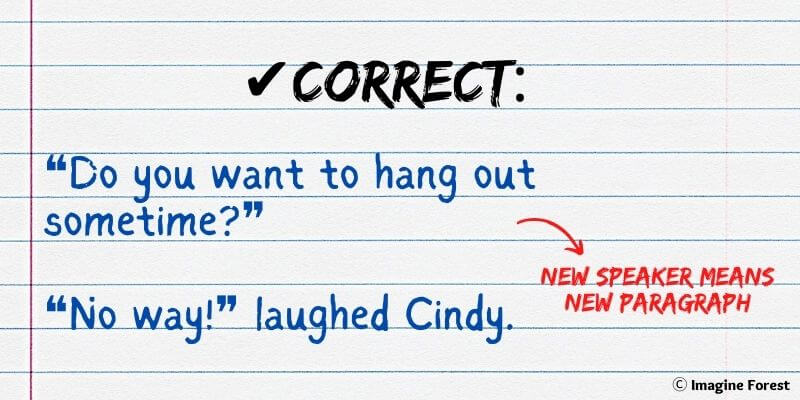

- Start a new paragraph each time there’s a new speaker. Whenever a new character begins to speak, you should give them their own paragraph. This rule makes it easier for the reader to follow the conversation.

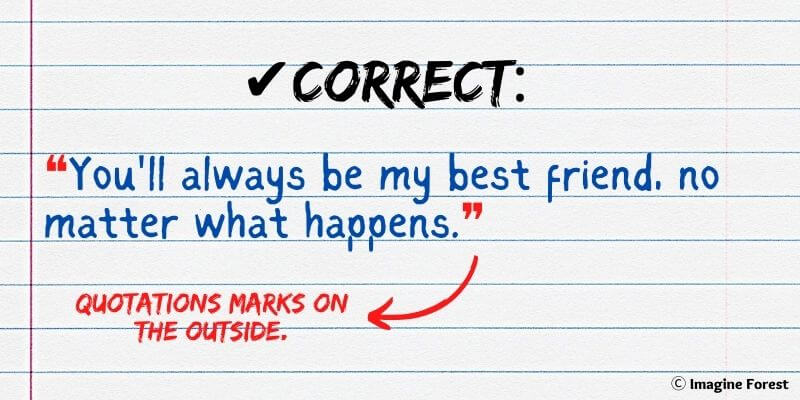

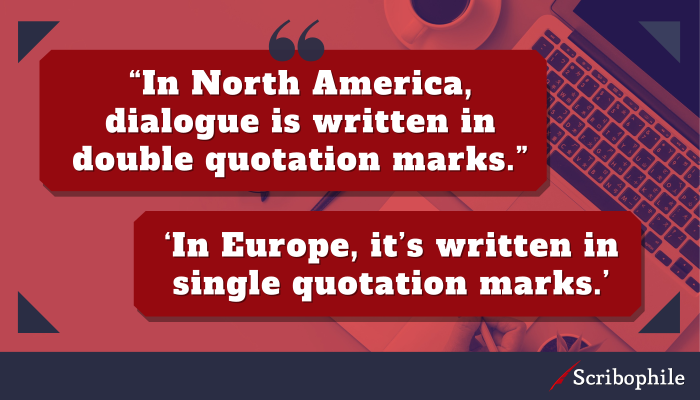

- Keep all speech between quotation marks . Everything that a character says should go between quotation marks, including the final punctuation marks. For example, periods and commas should always come before the final quotation mark, not after.

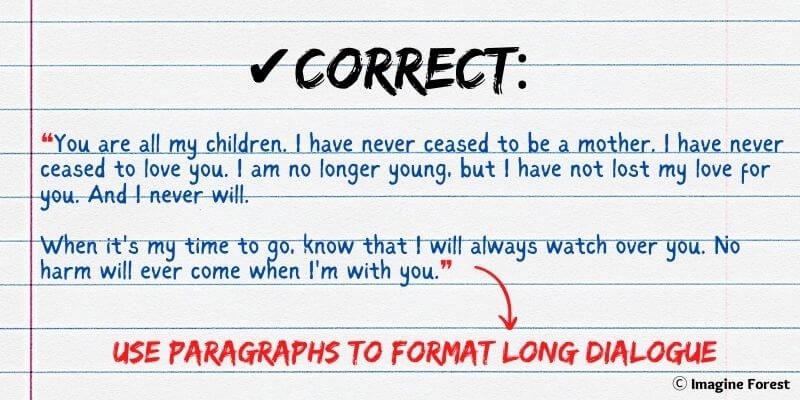

- Don’t use end quotations for paragraphs within long speeches. If a single character speaks for such a long time that you break their speech up into multiple paragraphs, you should omit the quotation marks at the end of each paragraph until they stop talking. The final quotation mark indicates that their speech is over.

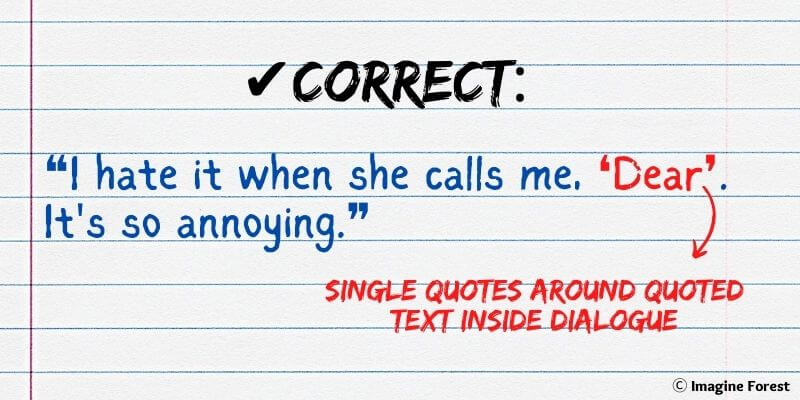

- Use single quotes when a character quotes someone else. Whenever you have a quote within a quote, you should use single quotation marks (e.g. She said, “He had me at ‘hello.’”)

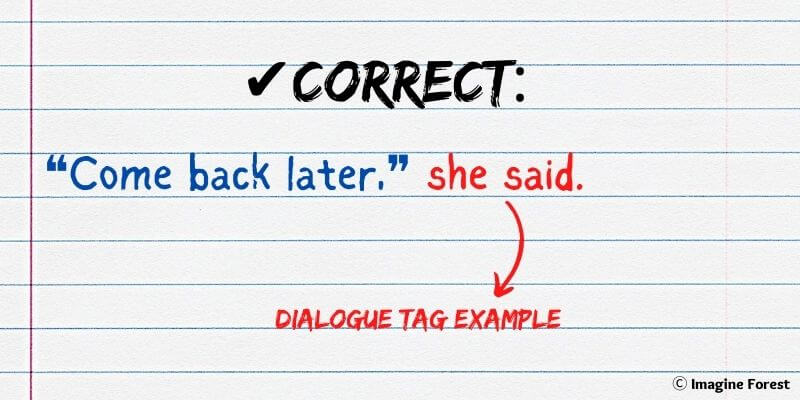

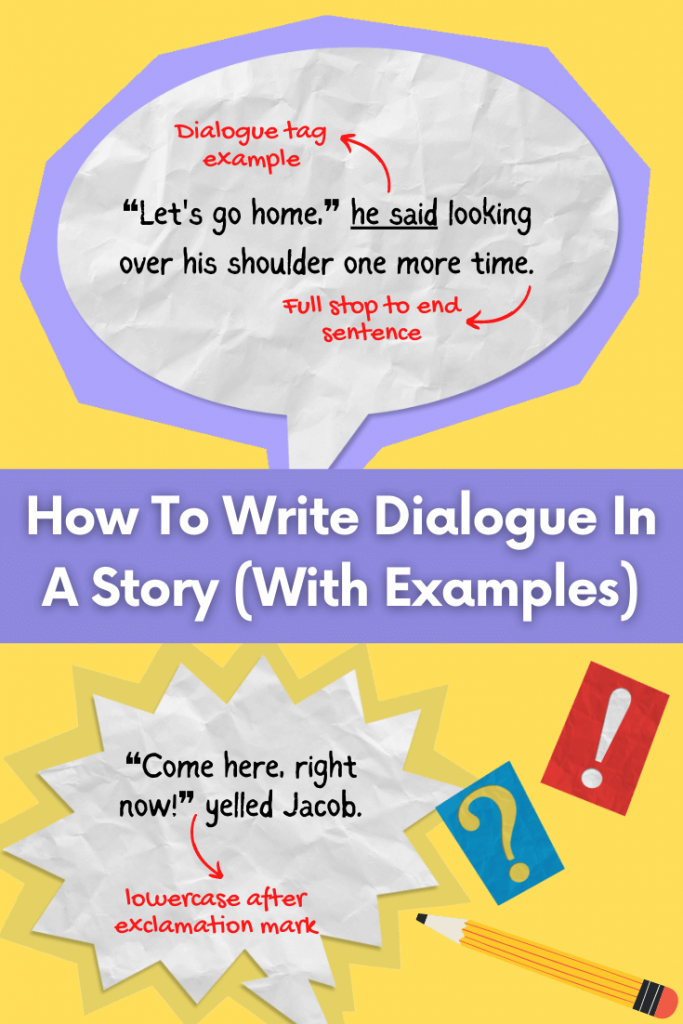

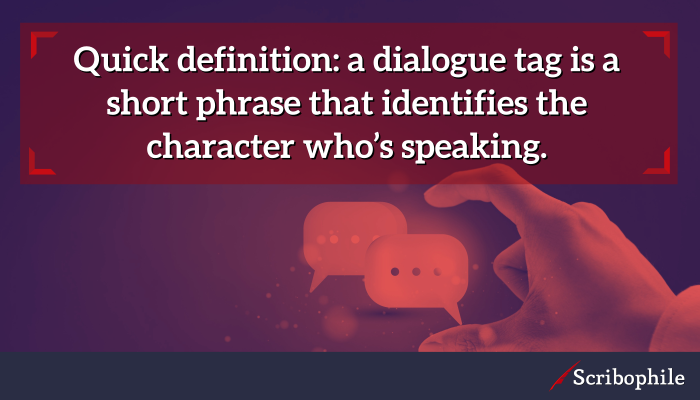

- Dialogue tags are optional. A dialogue tag is anything that indicates which character is speaking and how, such as “she said,” “he whispered,” or “I shouted.” You can use dialogue tags if you want to give the reader more information about who’s speaking, but you can also choose to omit them if you want the dialogue to flow more naturally. We’ll be discussing more about this rule in our tips below.

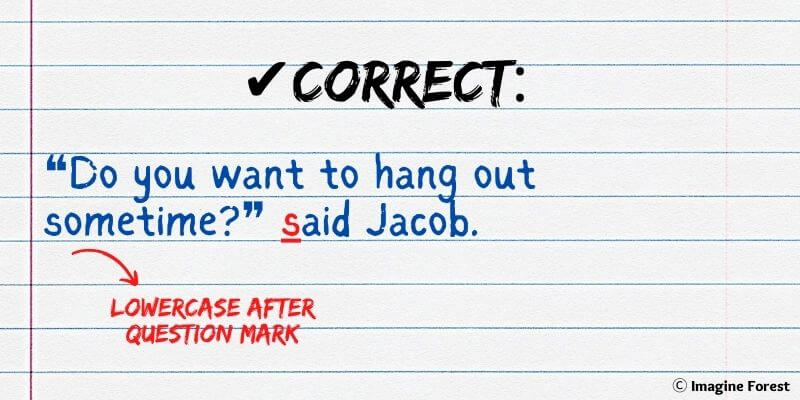

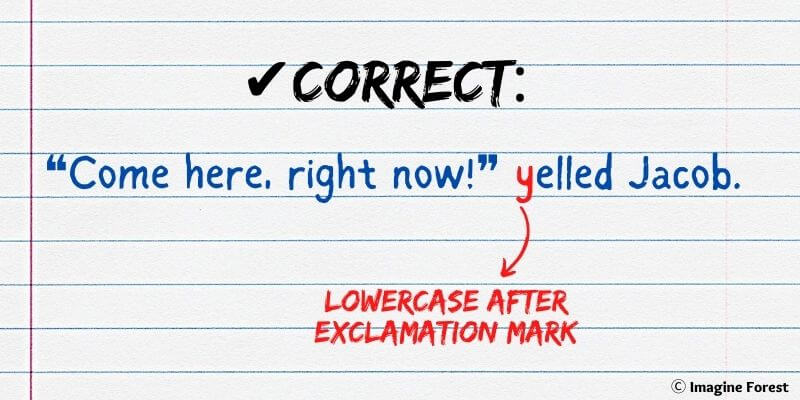

Let’s walk through some examples of how to format dialogue .

The simplest formatting option is to write a line of speech without a dialogue tag. In this case, the entire line of speech goes within the quotation marks, including the period at the end.

- Example: “I think I need a nap.”

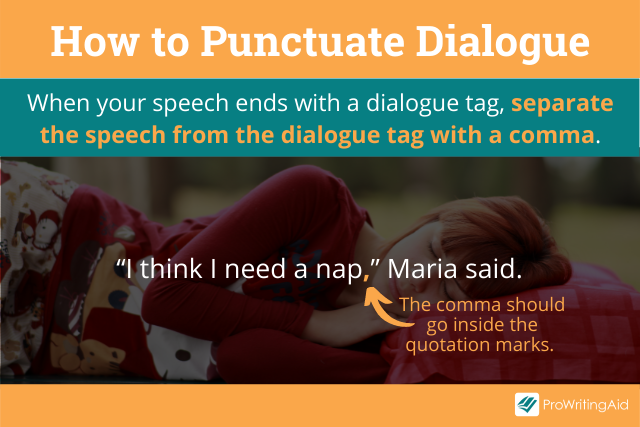

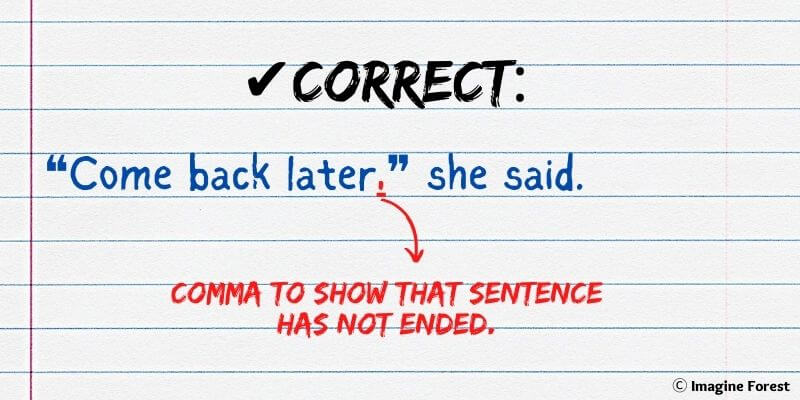

Another common formatting option is to write a single line of speech that ends with a dialogue tag.

Here, you should separate the speech from the dialogue tag with a comma, which should go inside the quotation marks.

- Example: “I think I need a nap,” Maria said.

You can also write a line of speech that starts with a dialogue tag. Again, you separate the dialogue tag with a comma, but this time, the comma goes outside the quotation marks.

- Example: Maria said, “I think I need a nap.”

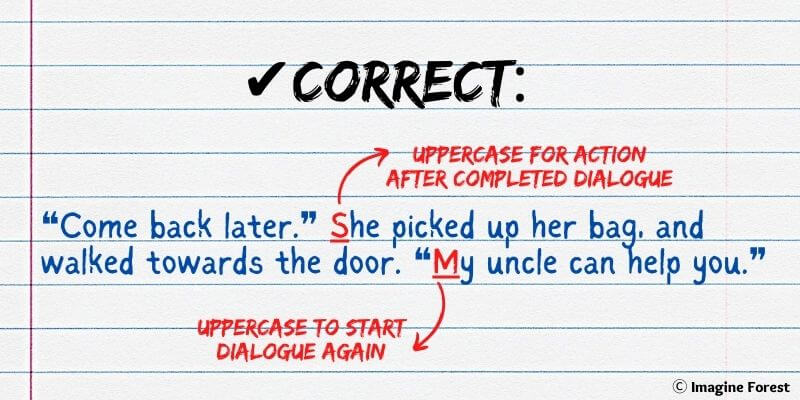

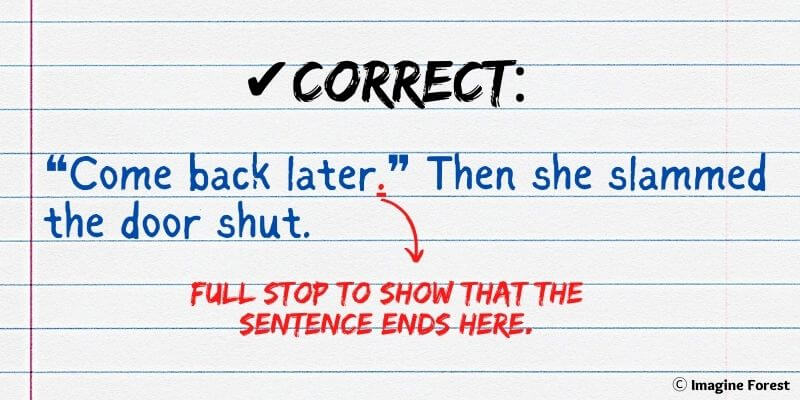

As an alternative to a simple dialogue tag, you can write a line of speech accompanied by an action beat. In this case, you should use a period rather than a comma, because the action beat is a full sentence.

- Example: Maria sat down on the bed. “I think I need a nap.”

Finally, you can choose to include an action beat while the character is talking.

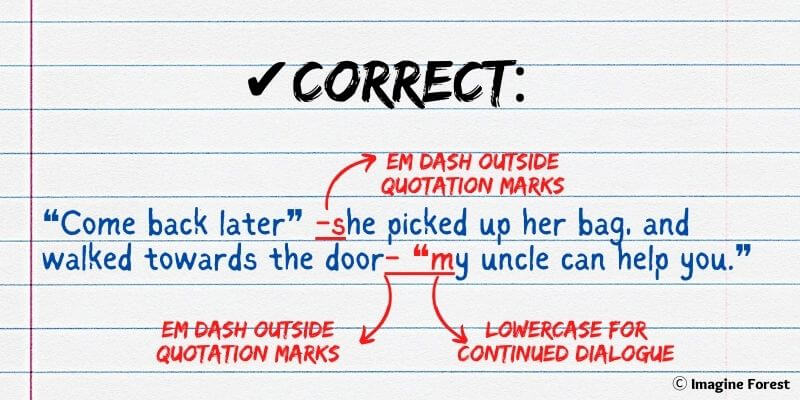

In this case, you would use em-dashes to separate the action from the dialogue, to indicate that the action happens without a pause in the speech.

- Example: “I think I need”—Maria sat down on the bed—“a nap.”

Now that we’ve covered the basics, we can move on to the more nuanced aspects of writing dialogue.

Here are our seven favorite tips for writing strong, powerful dialogue that will keep your readers engaged.

Tip #1: Create Character Voices

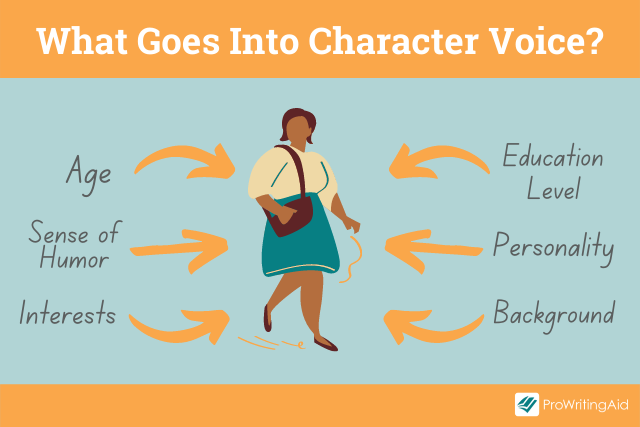

Dialogue is a great way to reveal your characters. What your characters say, and how they say it, can tell us so much about what kind of people they are.

Some characters are witty and gregarious. Others are timid and unobtrusive.

Speech patterns vary drastically from person to person.

To make someone stop talking to them, one character might say “I would rather not talk about this right now,” while another might say, “Shut your mouth before I shut it for you.”

When you’re writing dialogue, think about your character’s education level, personality, and interests.

- What kind of slang do they use?

- Do they prefer long or short sentences?

- Do they ask questions or make assertions?

Each character should have their own voice.

Ideally, you want to write dialogue that lets your reader identify the person speaking at any point in your story just by looking at what’s between the quotation marks.

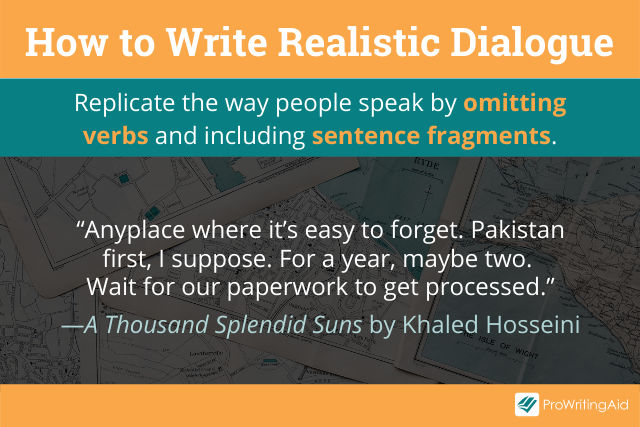

Tip #2: Write Realistic Dialogue

Good dialogue should sound natural. Listen to how people talk in real life and try to replicate it on the page when you write dialogue.

Don’t be afraid to break the rules of grammar, or to use an occasional exclamation point to punctuate dialogue.

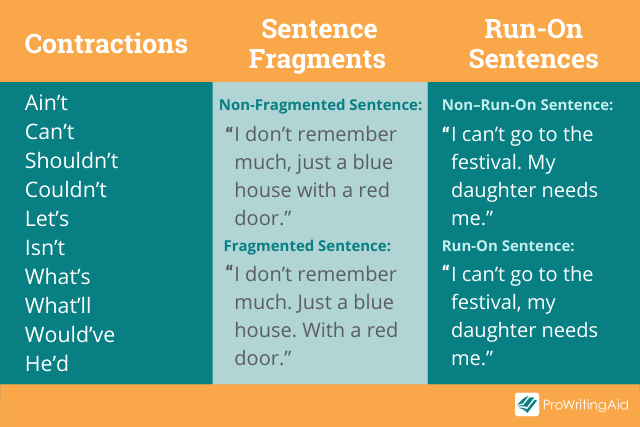

It’s okay to use contractions , sentence fragments , and run-on sentences , even if you wouldn’t use them in other parts of the story.

This doesn’t mean that realistic dialogue should sound exactly like the way people speak in the real world.

If you’ve ever read a court transcript, you know that real-life speech is riddled with “ums” and “ahs” and repeated words and phrases. A few paragraphs of this might put your readers to sleep.

Compelling dialogue should sound like a real conversation, while still being wittier, smoother, and better worded than real speech.

Tip #3: Simplify Your Dialogue Tags

A dialogue tag is anything that tells the reader which character is talking within that same paragraph, such as “she said” or “I asked.”

When you’re writing dialogue, remember that simple dialogue tags are the most effective .

Often, you can omit dialogue tags after the conversation has started flowing, especially if only two characters are participating.

The reader will be able to keep up with who’s speaking as long as you start a new paragraph each time the speaker changes.

When you do need to use a dialogue tag, a simple “he said” or “she said” will do the trick.

Our brains generally skip over the word “said” when we’re reading, while other dialogue tags are a distraction.

A common mistake beginner writers make is to avoid using the word “said.”

Characters in amateur novels tend to mutter, whisper, declare, or chuckle at every line of dialogue. This feels overblown and distracts from the actual story.

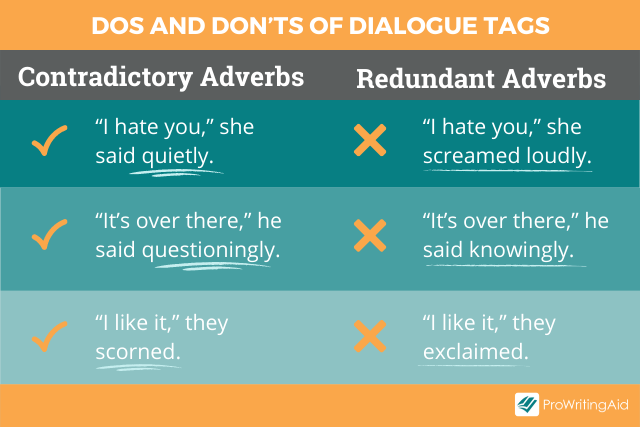

Another common mistake is to attach an adverb to the word “said.” Characters in amateur novels rarely just say things—they have to say things loudly, quietly, cheerfully, or angrily.

If you’re writing great dialogue, readers should be able to figure out whether your character is cheerful or angry from what’s within the quotation marks.

The only exception to this rule is if the dialogue tag contradicts the dialogue itself. For example, consider this sentence:

- “You’ve ruined my life,” she said angrily.

The word “angrily” is redundant here because the words inside the quotation marks already imply that the character is speaking angrily.

In contrast, consider this sentence:

- “You’ve ruined my life,” she said thoughtfully.

Here, the word “thoughtfully” is well-placed because it contrasts with what we might otherwise assume. It adds an additional nuance to the sentence inside the quotation marks.

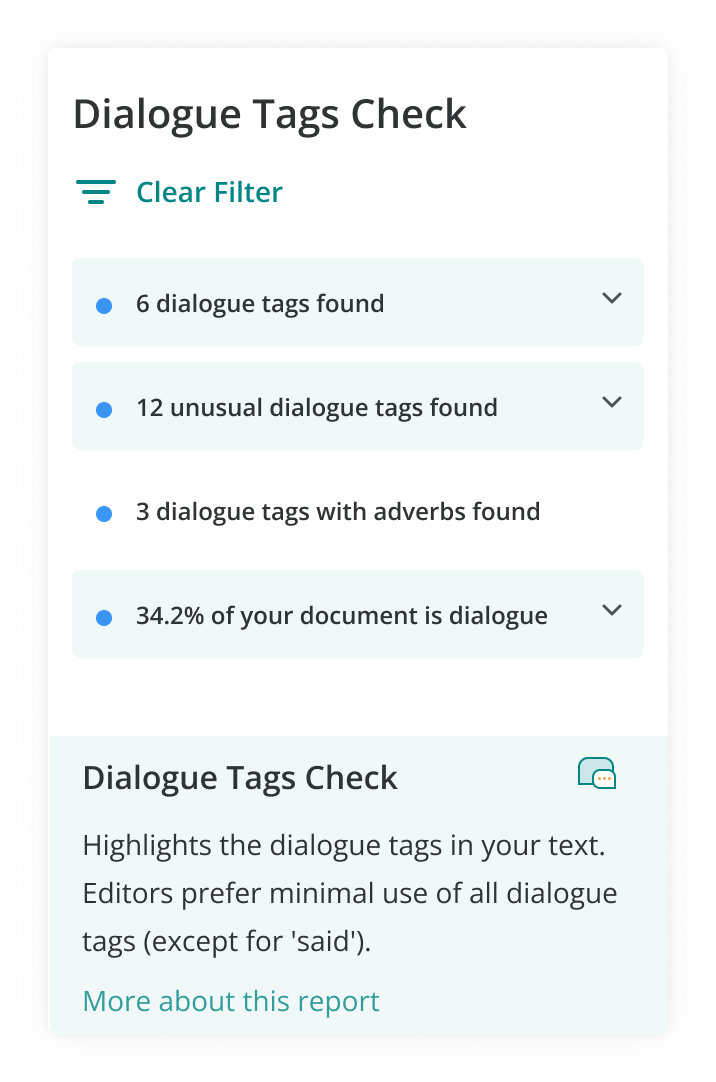

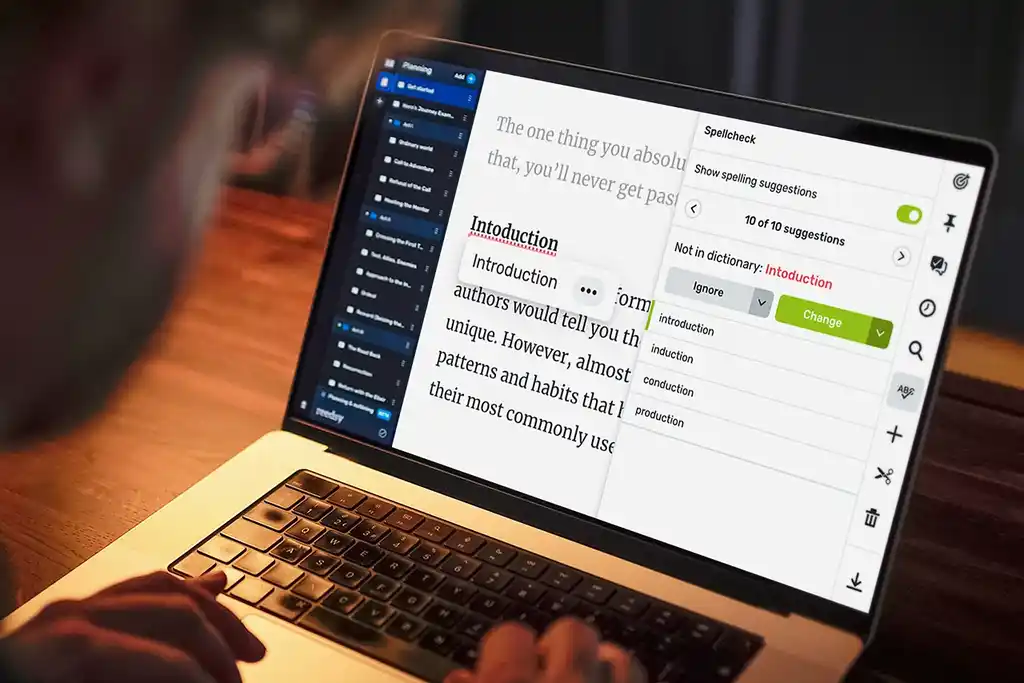

You can use the ProWritingAid dialogue check when you write dialogue to make sure your dialogue tags are pulling their weight and aren’t distracting readers from the main storyline.

Sign up for your free ProWritingAid account to check your dialogue tags today.

Tip #4: Balance Speech with Action

When you’re writing dialogue, you can use action beats —descriptions of body language or physical action—to show what each character is doing throughout the conversation.

Learning how to write action beats is an important component of learning how to write dialogue.

Good dialogue becomes even more interesting when the characters are doing something active at the same time.

You can watch people in real life, or even characters in movies, to see what kinds of body language they have. Some pick at their fingernails. Some pace the room. Some tap their feet on the floor.

Including physical action when writing dialogue can have multiple benefits:

- It changes the pace of your dialogue and makes the rhythm more interesting

- It prevents “white room syndrome,” which is when a scene feels like it’s happening in a white room because it’s all dialogue and no description

- It shows the reader who’s speaking without using speaker tags

You can decide how often to include physical descriptions in each scene. All dialogue has an ebb and flow to it, and you can use beats to control the pace of your dialogue scenes.

If you want a lot of tension in your scene, you can use fewer action beats to let the dialogue ping-pong back and forth.

If you want a slower scene, you can write dialogue that includes long, detailed action beats to help the reader relax.

You should start a separate sentence, or even a new paragraph, for each of these longer beats.

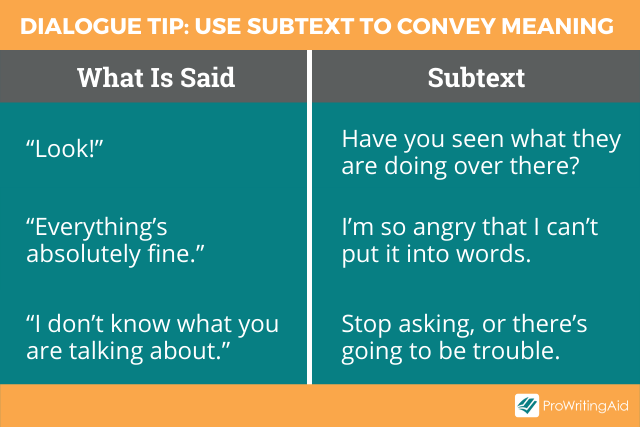

Tip #5: Write Conversations with Subtext

Every conversation has subtext , because we rarely say exactly what we mean. The best dialogue should include both what is said and what is not said.

I once had a roommate who cared a lot about the tidiness of our apartment, but would never say it outright. We soon figured out that whenever she said something like “I might bring some friends over tonight,” what she meant was “Please wash your dishes, because there are no clean plates left for my friends to use.”

When you’re writing dialogue, it’s important to think about what’s not being said. Even pleasant conversations can hide a lot beneath the surface.

Is one character secretly mad at the other?

Is one secretly in love with the other?

Is one thinking about tomorrow’s math test and only pretending to pay attention to what the other person is saying?

Personally, I find it really hard to use subtext when I write dialogue from scratch.

In my first drafts I let my characters say what they really mean. Then, when I’m editing, I go back and figure out how to convey the same information through subtext instead.

Tip #6: Show, Don’t Tell

When I was in high school, I once wrote a story in which the protagonist’s mother tells her: “As you know, Susan, your dad left us when you were five.”

I’ve learned a lot about the writing craft since high school, but it doesn’t take a brilliant writer to figure out that this is not something any mother would say to her daughter in real life.

The reason I wrote that line of dialogue was because I wanted to tell the reader when Susan last saw her father, but I didn’t do it in a realistic way.

Don’t shoehorn information into your characters’ conversations if they’re not likely to say it to each other.

One useful trick is to have your characters get into an argument.

You can convey a lot of information about a topic through their conflicting opinions, without making it sound like either of the characters is saying things for the reader’s benefit.

Here’s one way my high school self could have conveyed the same information in a more realistic way in just a few lines:

Susan: “Why didn’t you tell me Dad was leaving? Why didn’t you let me say goodbye?”

Mom: “You were only five. I wanted to protect you.”

Tip #7: Keep Your Dialogue Concise

Dialogue tends to flow out easily when you’re drafting your story, so in the editing process, you’ll need to be ruthless. Cut anything that doesn’t move the story forward.

Try not to write dialogue that feels like small talk.

You can eliminate most hellos and goodbyes, or summarize them instead of showing them. Readers don’t want to waste their time reading dialogue that they hear every day.

In addition, try not to write dialogue with too many trigger phrases, which are questions that trigger the next line of dialogue, such as:

- “And then what?”

- “What do you mean?”

It’s tempting to slip these in when you’re writing dialogue because they keep the conversation flowing. I still catch myself doing this from time to time.

Remember that you don’t need three lines of dialogue when one line could accomplish the same thing.

Let’s look at some dialogue examples from successful novels that follow each of our seven tips.

Dialogue Example #1: How to Create Character Voice

Let’s start with an example of a character with a distinct voice from Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets by J.K. Rowling.

“What happened, Harry? What happened? Is he ill? But you can cure him, can’t you?” Colin had run down from his seat and was now dancing alongside them as they left the field. Ron gave a huge heave and more slugs dribbled down his front. “Oooh,” said Colin, fascinated and raising his camera. “Can you hold him still, Harry?”

Most readers could figure out that this was Colin Creevey speaking, even if his name hadn’t been mentioned in the passage.

This is because Colin Creevey is the only character who speaks with such extreme enthusiasm, even at a time when Ron is belching slugs.

This snippet of written dialogue does a great job of showing us Colin’s personality and how much he worships his hero Harry.

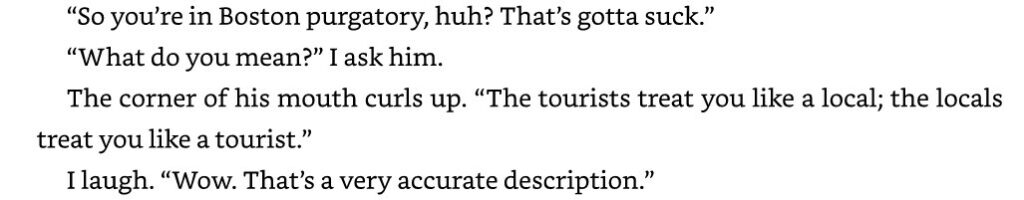

Dialogue Example #2: How to Write Realistic Dialogue

Here’s an example of how to write dialogue that feels realistic from A Thousand Splendid Suns by Khaled Hosseini.

“As much as I love this land, some days I think about leaving it,” Babi said. “Where to?” “Anyplace where it’s easy to forget. Pakistan first, I suppose. For a year, maybe two. Wait for our paperwork to get processed.” “And then?” “And then, well, it is a big world. Maybe America. Somewhere near the sea. Like California.”

Notice the punctuation and grammar that these two characters use when they speak.

There are many sentence fragments in this conversation like, “Anyplace where it’s easy to forget.” and “Somewhere near the sea.”

Babi often omits the verbs from his sentences, just like people do in real life. He speaks in short fragments instead of long, flowing paragraphs.

This dialogue shows who Babi is and feels similar to the way a real person would talk, while still remaining concise.

Dialogue Example #3: How to Simplify Your Dialogue Tags

Here’s an example of effective dialogue tags in Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier.

In this passage, the narrator’s been caught exploring the forbidden west wing of her new husband’s house, and she’s trying to make excuses for being there.

“I lost my way,” I said, “I was trying to find my room.” “You have come to the opposite side of the house,” she said; “this is the west wing.” “Yes, I know,” I said. “Did you go into any of the rooms?” she asked me. “No,” I said. “No, I just opened a door, I did not go in. Everything was dark, covered up in dust sheets. I’m sorry. I did not mean to disturb anything. I expect you like to keep all this shut up.” “If you wish to open up the rooms I will have it done,” she said; “you have only to tell me. The rooms are all furnished, and can be used.” “Oh, no,” I said. “No. I did not mean you to think that.”

In this passage, the only dialogue tags Du Maurier uses are “I said,” “she said,” and “she asked.”

Even so, you can feel the narrator’s dread and nervousness. Her emotions are conveyed through what she actually says, rather than through the dialogue tags.

This is a splendid example of evocative speech that doesn’t need fancy dialogue tags to make it come to life.

Dialogue Example #4: How to Balance Speech with Action

Let’s look at a passage from The Princess Bride by William Goldman, where dialogue is melded with physical action.

With a smile the hunchback pushed the knife harder against Buttercup’s throat. It was about to bring blood. “If you wish her dead, by all means keep moving," Vizzini said. The man in black froze. “Better,” Vizzini nodded. No sound now beneath the moonlight. “I understand completely what you are trying to do,” the Sicilian said finally, “and I want it quite clear that I resent your behavior. You are trying to kidnap what I have rightfully stolen, and I think it quite ungentlemanly.” “Let me explain,” the man in black began, starting to edge forward. “You’re killing her!” the Sicilian screamed, shoving harder with the knife. A drop of blood appeared now at Buttercup’s throat, red against white.

In this passage, William Goldman brings our attention seamlessly from the action to the dialogue and back again.

This makes the scene twice as interesting, because we’re paying attention not just to what Vizzini and the man in black are saying, but also to what they’re doing.

This is a great way to keep tension high and move the plot forward.

Dialogue Example #5: How to Write Conversations with Subtext

This example from Ender’s Game by Orson Scott Card shows how to write dialogue with subtext.

Here is the scene when Ender and his sister Valentine are reunited for the first time, after Ender’s spent most of his childhood away from home training to be a soldier.

Ender didn’t wave when she walked down the hill toward him, didn’t smile when she stepped onto the floating boat slip. But she knew that he was glad to see her, knew it because of the way his eyes never left her face. “You’re bigger than I remembered,” she said stupidly. “You too,” he said. “I also remembered that you were beautiful.” “Memory does play tricks on us.” “No. Your face is the same, but I don’t remember what beautiful means anymore. Come on. Let’s go out into the lake.”

In this scene, we can tell that Valentine missed her brother terribly, and that Ender went through a lot of trauma at Battle School, without either of them saying it outright.

The conversation could have started with Valentine saying “I missed you,” but instead, she goes for a subtler opening: “You’re bigger than I remembered.”

Similarly, Ender could say “You have no idea what I’ve been through,” but instead he says, “I don’t remember what beautiful means anymore.”

We can deduce what each of these characters is thinking and feeling from what they say and from what they leave unsaid.

Dialogue Example #6: How to Show, Not Tell

Let’s look at an example from The Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss. This scene is the story’s first introduction of the ancient creatures called the Chandrian.

“I didn’t know the Chandrian were demons,” the boy said. “I’d heard—” “They ain’t demons,” Jake said firmly. “They were the first six people to refuse Tehlu’s choice of the path, and he cursed them to wander the corners—” “Are you telling this story, Jacob Walker?” Cob said sharply. “Cause if you are, I’ll just let you get on with it.” The two men glared at each other for a long moment. Eventually Jake looked away, muttering something that could, conceivably, have been an apology. Cob turned back to the boy. “That’s the mystery of the Chandrian,” he explained. “Where do they come from? Where do they go after they’ve done their bloody deeds? Are they men who sold their souls? Demons? Spirits? No one knows.” Cob shot Jake a profoundly disdainful look. “Though every half-wit claims he knows...”

The three characters taking part in this conversation all know what the Chandrian are.

Imagine if Cob had said “As we all know, the Chandrian are mysterious demon-spirits.” We would feel like he was talking to us, not to the two other characters.

Instead, Rothfuss has all three characters try to explain their own understanding of what the Chandrian are, and then shoot each other’s explanations down.

When Cob reprimands Jake for interrupting him and then calls him a half-wit for claiming to know what he’s talking about, it feels like a realistic interaction.

This is a clever way for Rothfuss to introduce the Chandrian in a believable way.

Dialogue Example #7: How to Keep Your Dialogue Concise

Here’s an example of concise dialogue from The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger.

“Do you blame me for flunking you, boy?” he said. “No, sir! I certainly don’t,” I said. I wished to hell he’d stop calling me “boy” all the time. He tried chucking my exam paper on the bed when he was through with it. Only, he missed again, naturally. I had to get up again and pick it up and put it on top of the Atlantic Monthly. It’s boring to do that every two minutes. “What would you have done in my place?” he said. “Tell the truth, boy.” Well, you could see he really felt pretty lousy about flunking me. So I shot the bull for a while. I told him I was a real moron, and all that stuff. I told him how I would’ve done exactly the same thing if I’d been in his place, and how most people didn’t appreciate how tough it is being a teacher. That kind of stuff. The old bull.

Here, the last paragraph diverges from the prior ones. After the teacher says “Tell the truth, boy,” the rest of the conversation is summarized, rather than shown.

The summary of what the narrator says in the last paragraph—“I told him I was a real moron, and all that stuff”—serves to hammer home that this is the type of “old bull” that the narrator has fed to his teachers over and over before.

It doesn’t need to be shown because it’s not important to the narrator—it’s just “all that stuff.”

Salinger could have written out the entire conversation in dialogue, but instead he kept the dialogue concise.

Final Words

Now you know how to write clear, effective dialogue! Start with the basic rules for dialogue and try implementing the more advanced tips as you go.

What are your favorite dialogue tips? Let us know in the comments below.

Do you know how to craft memorable, compelling characters? Download this free book now:

Creating Legends: How to Craft Characters Readers Adore… or Despise!

This guide is for all the writers out there who want to create compelling, engaging, relatable characters that readers will adore… or despise., learn how to invent characters based on actions, motives, and their past..

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Hannah Yang

Hannah Yang is a speculative fiction writer who writes about all things strange and surreal. Her work has appeared in Analog Science Fiction, Apex Magazine, The Dark, and elsewhere, and two of her stories have been finalists for the Locus Award. Her favorite hobbies include watercolor painting, playing guitar, and rock climbing. You can follow her work on hannahyang.com, or subscribe to her newsletter for publication updates.

Get started with ProWritingAid

It's A Steal

Bring your story to life for less. Get 25% off yearly plans in our Storyteller's Sale. Grab the discount while it lasts.

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Writing dialogue: Complete guide to storied speech

Writing dialogue is an important skill to develop so that characters’ speech is imbued with voice and advances the story. Learn more in this complete guide to dialogue writing and formatting, with examples.

- Post author By Jordan

- 37 Comments on Writing dialogue: Complete guide to storied speech

This guide to writing dialogue is all about using speech and conversation in storytelling to make your characters’ voices drive plot, tension and drama. Use the links to jump to the dialogue-writing topic you want to learn more about right now.

What is dialogue? Key terms

Dialogue in writing is conversation between two or more people/animated voices (animated voices because it could be speech between a person and an inanimate object they personify, for example, an imaginary or supernatural voice, and so forth).

Dialogue can be compared to:

- A tennis or fencing match: Speakers may spar, score points, volley arguments or statements (and rebuttals to them) back and forth

- A dance: One speaker says one line, the other replies, and sometimes one person may lead, at other times, the other leads

- Pieces in a puzzle coming together: What different characters say may build up a gradual picture, for example an idea of the persona of a character who has not yet appeared in a story scene but has been spoken about by others

- Music: sometimes there is harmony (working together), other times discord (strife, heated conversation or disagreement)

Key terms in writing dialogue

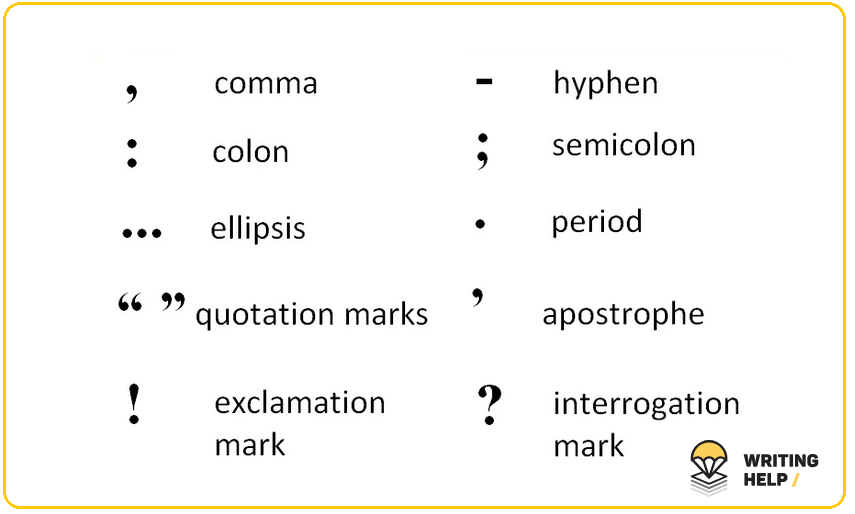

There are several terms in dialogue worth knowing as they crop up often in discussing this element of writing craft:

Active listening: Dialogue is (usually) responsive

When somebody is engaged in ‘active listening’, they aren’t just waiting for their turn to speak. In a true conversation, people hear one another, respond.

There may be instances where your dialogue’s subtext or context (more on these below) calls for characters not to actively listen to one another, of course. There may be cause for them to interrupt, speak over, speak at cross purposes.

In these cases, it should be contextually or otherwise clear why characters aren’t properly responding to each other’s speech (the dialogue should not read or sound like random non sequiturs, each person’s utterances totally disconnected for no clear reason).

Context for dialogue

Effective dialogue involves its context. For example, in a frenzied car chase, the squeal of tires may drown out the exchange here or there. Speech and action in this context may reflect rapid decision-making, keeping pace.

In the middle of a bank heist, people may be curt, decisive (of course, inept thieves could wax lyrical and by talking too much make rookie mistakes).

Either way, context will inform how readers make sense of your dialogue, and helps to fill dialogue with tone and mood . Nobody whispers to each other standing next to Niagara falls (if they want to be heard).

Subtext and dialogue

Subtext in dialogue is the underlying meaning, motivation or feeling behind the words characters speak.

For example, a boss starts a casual conversation with a new employee but the subtext is that they’re having regrets at hiring the person and trying to come to a decision on whether to terminate in the trial period. The subtext will inform what language they will use (and this language would be different to someone ecstatic with their employee’s performance).

Subtext adds depth and complexity to dialogue, strata of the said and unsaid.

Purpose in dialogue

Why is the information you are writing in a scene given as dialogue? Knowing the purpose of dialogue (and writing dialogue that feels purpose-driven) is useful to ensure that every spoken line counts. In a stage play, dialogue and action are the two drivers of story.

In narrative fiction, you also get to use narration to convey meaning. A story where all character information is conveyed through narration may read oddly voiceless, impersonal. Dialogue makes your characters pause, take a breath, like real flesh and blood.

Recommended reading

Learn more about writing conversations that feel real and draw on cause and effect, call and response:

- Context and subtext in dialogue: Creating layered speech

- How to make dialogue in writing carry your story

- 7 dialogue rules for writing fantastic conversations

To the top ↑

I write plays because writing dialogue is the only respectable way of contradicting yourself. I put a position, rebut it, refute the rebuttal, and rebut the refutation. Tom Stoppard

GET YOUR FREE GUIDE TO SCENE STRUCTURE

Read a guide to writing scenes with purpose that move your story forward.

Why dialogue matters

Why do most stories benefit from liberal use of dialogue?

1. Dialogue brings characters and their differences to life

In dialogue, you could show a character’s personality in a handful of words. Here, for example, Dostoyevsky creates the sense of a decisive doctor, used to dealing with uncertain, anxious patients in The Double :

‘Krestyan Ivanovich … I …’ ‘Hm,’ interrupted the doctor, ‘what I’m telling you is that you need to radically change your whole lifestyle and in a sense you must completely transform your character.’ (Krestyan Ivanovich particularly emphasized the word ‘transform’ and paused for a moment with an extremely significant look.) Fyodor Dostoyevsky, The Double , trans. Ronald Wilks (1846, 2009), p. 11

There is an immediate sense of power dynamic (and differential) – the hesitating patient and his decisive doctor.

2. Dialogue splits up exposition into varied parts

If all the revelation of your characters and world is in long, wall-of-text narration, it becomes slightly draining to read.

Dialogue lifts us out of a ‘this happened, then that’ sense of explanation and throws us into the immediate – sound striking the eardrum. Tweet This

3. Dialogue advances a story

Characters may tell each other things that reveal – or shift – goals, motivations, conflicts. ‘But first, I must tell you Mr Bond…’ A villain may say too much, a lover, too little (or vice versa).

4. Conversation builds relationships

Some of the most beautiful relationships (or the most ugly) emerge through what people say to one another.

Ed’s note: As an undergraduate in English Literature, I attended a lecture on Pride and Prejudice where the lecturer illustrated how Lizzie and Darcy’s love is established through the grammar of their language and how it shifts. At one point, Darcy says, ‘You are loved by me’ – a different structure to the standard ‘I love you’ that places the subject first, in a way that reads as full of care.

We detect attraction and resentment in the language people use with one another. A conversation about the weather may imply feelings – it comes down to tone, address, mood, agreement and disagreement.

5. Dialogue brings humor, levity and persona to stories

Dialogue is often a vehicle for comedy. It’s a crucial part of how to write a funny story .

You can narrate that a character has grown wealthy and fallen out of touch with their humble origins. But in Dickens’ Great Expectations, when a character named ‘Trabb’s boy’, the tailor’s son, follows the main character Pip down the street mimicking him and saying, ‘Don’t know ya!’ after Pip is left wealth, it’s a brilliant and funny illustration of how people change (and perceive and react to changes in others).

Pip seems ‘too good for’ others now that he has wealth, and three words convey Trabb’s boy’s contempt with sly humor. Three words (paired with action, the following and mimicking) convey complex social dynamics and feelings.

Why else do you think dialogue matters? Tell us in the comments.

Learn more about writing dialogue that drives stories:

10 dialogue tips to hook readers

Hook readers into your story with dialogue that catches their attention.

- Writing movement and action in dialogue: 6 tips

How can movement and action make your dialogue more immersive? Find out.

Dialogue is the place that books are most alive and forge the most direct connection with readers. It is also where we as writers discover our characters and allow them to become real. Laini Taylor

How to format dialogue

Speech marks or quotation marks, and where do the line breaks go? Read on for how to format dialogue, common differences between UK and US formatting styles, and more:

Why do we format dialogue? Clarity, ease and flow

Try to write an exchange in dialogue all as block paragraph text and it becomes a nightmare trying to keep track of who says what:

“You’re late,” she said. “But I didn’t say what time I was coming.” “I don’t care, I’ve been waiting half an hour.” There was an awkward silence for a few seconds. “Well don’t say anything, whatever.”

It’s not clear from the above dialogue without line breaks and with no attribution for the last spoken sentence who says what at all times.

This is much easier to read because line breaks signal when the speaker changes:

It’s much easier to follow the back and forth (and because only two characters are present, the dialogue does not need excess attribution of who says what thanks to the line breaks clarifying this).

How to format dialogue in stories: 8 tips

To make sure it’s clear who’s speaking, when it changes, and when speech begins and ends (and narration or description interrupts):

1. Use quotation or speech marks to show when speech starts and stops

If a character is still speaking, don’t close speech marks prematurely.

2. Start a new line each time the speaker changes

Although it is common practice to use an indent for each change of speaker, make sure to use paragraph formatting in your word processor rather than the tab button as this can make indentation too large or wonky (using paragraph-wide settings is most precise).

3. Decide how you’ll format dialogue (and stick with it)

Speech marks with double quotations like the example from Colleen Hoover above (“) are more commonly used in the US, single quotation marks (‘) in books published in the UK.

Some contemporary novels don’t use speech marks at all, using an em dash at the start of a line or presenting dialogue another way. Whichever approach you use, consistency is key.

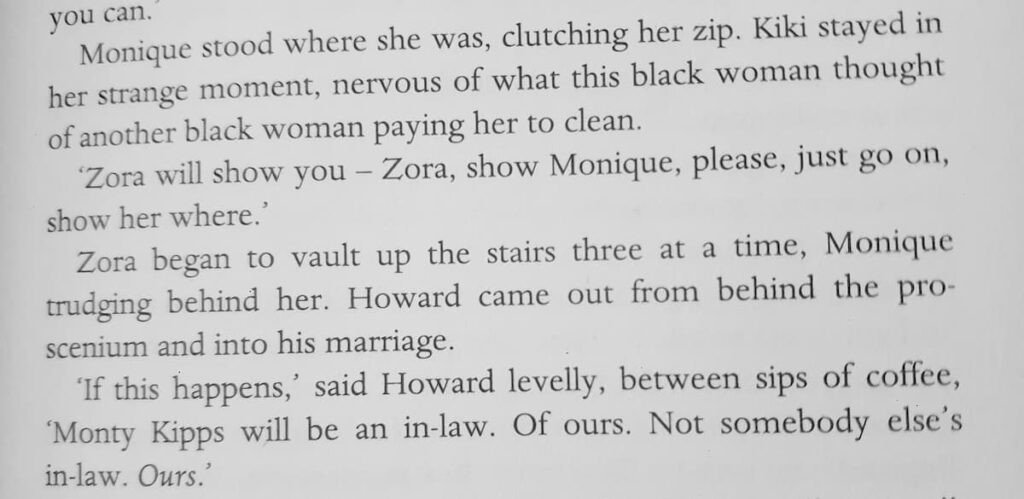

Example: Using single quotation marks to indicate speech

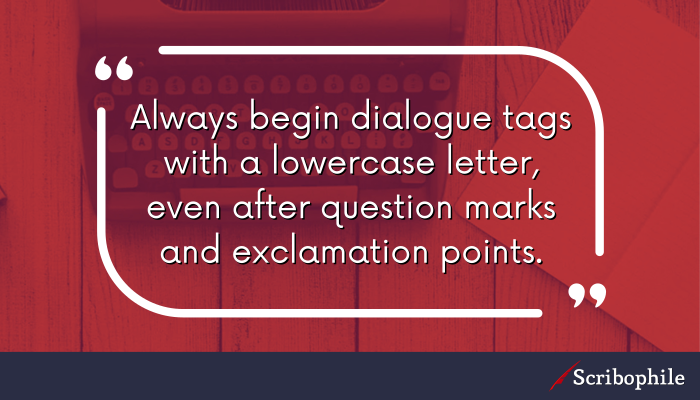

4. Always use a comma if there is an attributing tag

If dialogue is attributed using a tag such as ‘she said’ (read more on dialogue tags below), use a comma and not a period/full stop. For example:

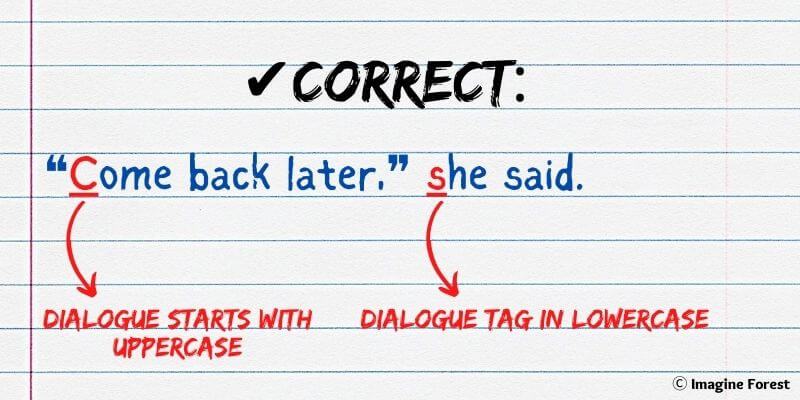

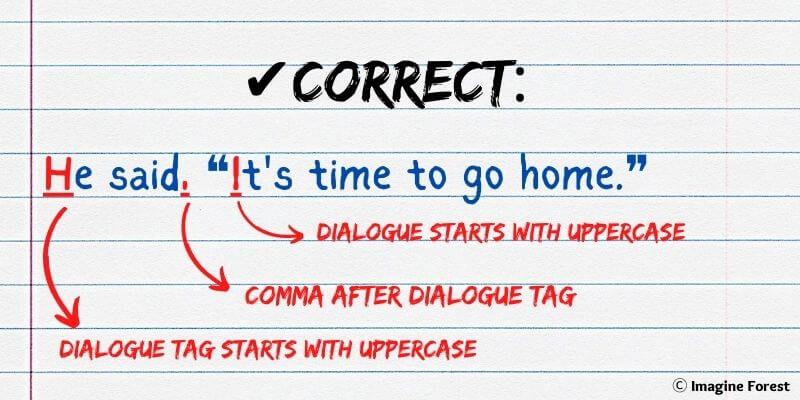

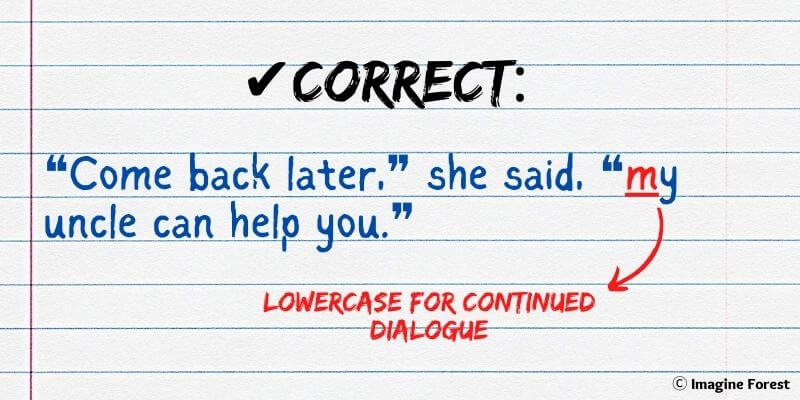

“Writing dialogue is harder than I thought.” She said. ❌ “Writing dialogue is harder than I thought,” she said. ✔️

Remember: the tag continues the sentence.

5. Split long monologue over multiple paragraphs

What if the same character is speaking for a long time in dialogue?

To format this, the convention is to open speech marks for each new paragraph without closing speech marks for the previous one, until the speaker is finished talking.

Example: Dialogue where one speaker continues over paragraphs

“First I want to thank you all for being here on our special day. It does take a village (but you can put down the pitchforks, take off the creepy masks, and relax a little, guys, it’s not that kind of village) … Er eheh… OK I’m firing my joke writers.

“But in all seriousness, I couldn’t have chosen a better bride…zilla.”

6. Use the appropriate dialogue punctuation

If a speaker pauses, put it in with a comma or something longer such as a semicolon. This is where it helps to read dialogue out loud as you will hear where there is a natural pause that needs punctuating. Colons have an announcing effect. Example: “OK, here’s the kicker: The guard changes every forty-five minutes.”

If there is a question or exclamation, use the appropriate speech mark (that includes the occasional special effect, such as an interrobang (!?).

7. Write interruption or other changes in dialogue’s flow clearly

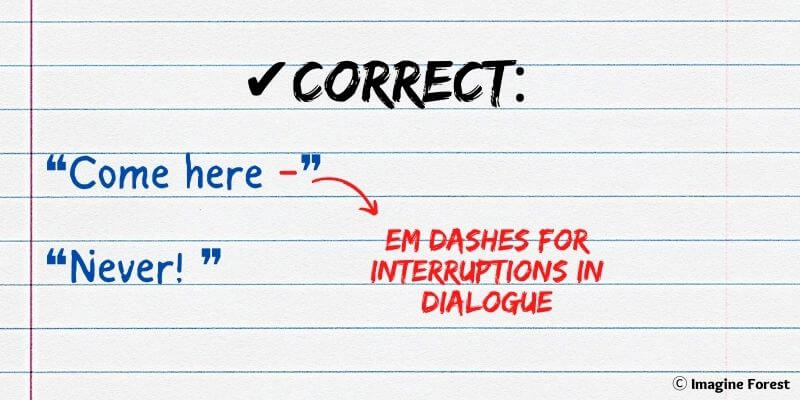

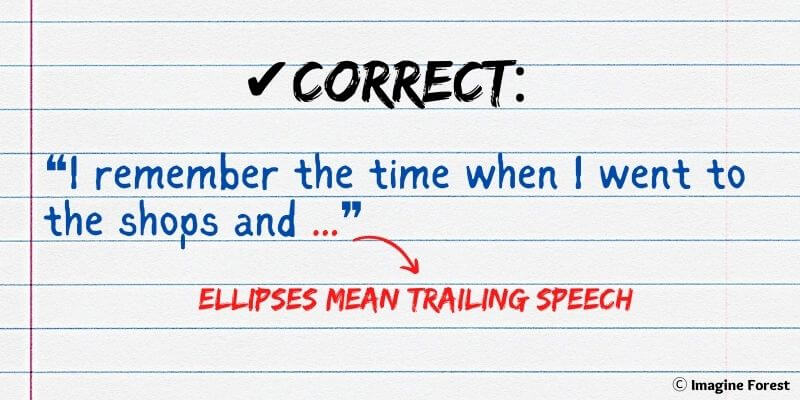

Ellipses are effective in showing a character trailing off or pausing to think for longer, mid-dialogue.

“Oh yes, I remember, it was … whatshername.”

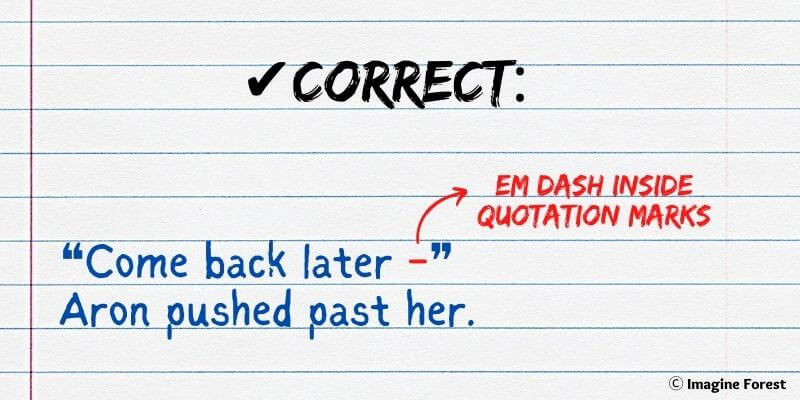

There are several ways to show interruption. You could:

- Use an em-dash just after cut-off speech. Example: “If you’d just let me fini—”

- Use parentheses to show self-interruption. Example: “If you’d just let me finish what I was (actually, it’s fine, carry on).”

8. Format narration interrupting dialogue clearly

If you want to describe a character’s manner, movement, expression mid-dialogue, remember to use a comma before and resume dialogue without capitalization (unless the word is a proper noun):

“I can’t believe you said that,” John said, shaking his head, “and with absolutely zero remorse, too.”

Read more on how to ensure your dialogue reads clearly, including how to write ensemble dialogue with multiple characters present:

- Writing dialogue between multiple characters

Nothing teaches you as much about dialogue as listening to it. Judy Blume

Effective vs weak dialogue

Why does some dialogue scintillate, stir interest, while other dialogue reads like talking heads saying nothing of great impact in an inky void? There are several hallmarks of effective and less effective dialogue:

What makes dialogue effective:

- An authentic sense of voice. Do characters sound like cipher’s for an author’s pretension (this may be true to a specific stylistic choice, though) or like real people talking?

- Purpose-driven dialogue. Each line of dialogue should have identifiable purpose, whether it’s establishing character, advancing the story, building tone and mood, or dialogue serves another purpose.

- Aptness for type (or explicable ‘against type’ voice). Avoid confusing your reader by having a five-year old speak like a fifty-year-old (unless there’s a plot-given or other explicable reason for this anomaly).

- Varied structure. If every sentence is clipped or brusque, or every sentence is long and meandering, the eye (and ear) may tire. Switch it up if possible.

- Natural language. Contractions (e.g. ‘it’s’ for ‘it is’) and other ways people naturally speak (colloquial language or slang) lend further authenticity to voice.

- Conflict and tension . ‘As you know, Bob’ info dumps and happy people in happy land don’t make dialogue exciting (but tension, disagreement, doubt – sparks of contradiction – do).

- Movement and gesture. A gesture may change the entire meaning of a spoken phrase (a shrug, turn, sitting down, standing up, waving arms, and so on).

- Subtext and inference. What a character is truly thinking or feeling might not match up perfectly with what they’re saying. People lie, omit, embellish, and so forth.

What can weaken dialogue in fiction?

Dialogue in stories may feel bland or confusing (or too over the top and melodramatic) when:

- It’s all one note. If every utterance is an exclamation (with an exclamation mark), that gets old fast. Use special effects like salt – just enough to enhance the conversation.

- Connection is absent. Your reader may be confused if what characters reply to each other seems as though they’re having two different conversations (unless there is contextual explanation, e.g. both are hard of hearing).

- The scenery stays outside. If your characters are having an argument in the kitchen, does someone bang a pot, slam a drawer? Bring in surrounds.

- There is no differentiation. If everyone has the exact same vocabulary, mannerisms, and pattern of speech, characters start to become clone-like, like so many Agent Smiths.

- Excessive or bizarre tags. Characters shouldn’t honk or trumpet speech too often. Favor tags that you can say or express (no, “What!” she flabbergasted’). Leave out tags entirely if context tells your reader who speaks (and content of speech gives tone/mood).

- Excessive dialect or accent. At best excessive dialect or accent may read distracting, at worst, like hurtful stereotype or caricature.

- Adverbs clutter speech. Instead of overusing ‘she says softly’, leave space for the silence to come through.

- Dialogue dumps information. ‘As you know, Bob’ is a phrase used for dialogue where characters tell each other things both already know solely for the reader’s benefit. Find ways to make the retelling new/fresh, find what Bob doesn’t yet know and needs to be told.

Keep reading about ways to make dialogue characterful and engaging:

- Dialogue words: Other words for ‘said’ (and what to avoid)

- How to write accents and dialects: 6 tips

- Realistic dialogue: Creating characters’ speech patterns

Pay $0 for writing insights and how to’s

Be first to know whenever we publish and get bonus videos and the latest Now Novel news.

Dialogue devices for characterful speech

There are several dialogue devices that help to advance stories and create a sense of movement, tension and change:

Dialogue tags and action tags

What are dialogue tags and action tags?

Dialogue tag: The words added after dialogue that attribute who has spoken (and often the mood, emotion, or volume of speech).

“You might want that tattoo, but I know all your secrets and your twenty-first is coming up and don’t think for a second I’m above making an awkward speech,” mom warned.

“Shh!” he hissed in a half-whisper. “This freaking place is haunted.”

Action tag: Indicates the speaker’s movements or gestures in dialogue. This can be used to attribute speech and make dialogue livelier.

“You might want that tattoo, but …” Mom leaned over theatrically as though to confide something important. “I know all your secrets and […]’

Movement and gesture

Movement and gesture may punctuate dialogue, immersing the reader in a scene further.

‘Then go,’ said Mrs Williams, handing him the buckets and the coil of rope. ‘Swim,’ she said maliciously. She knew he was afraid of the sea. He carried his fear coiled and tangled in him like other boys carry twine and string in their crumb-filled pockets. Peter Carey, Oscar and Lucinda (1988), p. 16

Interruption

Interruption is a useful device in dialogue for argument, dramatic scenes with high stakes where characters are speaking over one another, and so forth.

“I could have killed you.” “Or I could have killed you,” Percy said. Jason shrugged. “If there’d been an ocean in Kansas, maybe.” “I don’t need an ocean—” “Boys,” Annabeth interrupted, “I’m sure you both would’ve been wonderful at killing each other. But right now, you need some rest.” Rick Riordan, The Mark of Athena (2012).

Conflict and suspense

Conflict and suspense in dialogue keep the reader intrigued. Characters may argue, refuse to speak, tell a fib the reader may know to be untrue, or otherwise stir tension.

“What’s this for?” Tessie asked suspiciously. “What do you mean, what is it for?” “It’s not my birthday. It’s not our anniversary. So why are you giving me a present?” “Do I have to have a reason to give you a present? Go on, open it.” Tessie crumpled up one corner of her mouth, unconvinced. Jeffrey Eugenides, Middlesex (2002), p. 10.

Read more on devices in dialogue, including dialogue tags vs action tags and how to create tension:

- 421 ways to say said? Simplify dialogue instead

- Dialogue 101: Using dialogue tags vs action tags

- Writing tense dialogue: 5 ways to add arresting tension

I never say ‘She says softly.’ If it’s not already soft, you know, I have to leave a lot of space around it so a reader can hear that it’s soft. Toni Morrison

Dialogue examples that work

Read examples of dialogue that works from a cross-selection of genres including fantasy, romance, science fiction, thriller, historical, contemporary and more:

1. Fantasy dialogue example ( A Game of Thrones )

Note how George R. R. Martin weaves in setting to create mood between utterances in this exchange from the prologue to A Game of Thrones :

“We should start back,” Gared urged as the woods began to grow dark around them. “The wildlings are dead.” “Do the dead frighten you?” Ser Waymar Royce asked with just the hint of a smile. Gared did not rise to the bait. He was an old man, past fifty, and he had seen the lordlings come and go. “Dead is dead,” he said. “We have no business with the dead.” George R. R. Martin, A Game of Thrones (1996).

2. Historical romance dialogue example ( The Duke and I )

Julia Quinn begins the first chapter in the first of her popular Regency-set romance novels with a typical Regency setting – a drawing room (and drama in letters):

“Oooooooooohhhhhhhhhh!” Violet Bridgerton crumped the single-page newspaper into a ball and hurled it across the elegant drawing room. Her daughter Daphne wisely made no comment and pretended to be engrossed in her embroidery. “Did you read what she said?” Violet demanded. “Did you?” Julia Quinn, The Duke and I (2000).

3. Mystery dialogue example ( The Murder of Roger Ackroyd )

Dame Agatha Christie’s The Murder of Roger Ackroyd is often voted one of her best detective novels. In the first chapter already, conversation turns to death and the topic of who knows what about whom (and how):

My sister’s nose, which is long and thin, quivered a little at the tip, as it always does when she is interested or excited over anything. “Well?” she demanded. “A bad business. Nothing to be done. Must have died in her sleep.” “I know, said my sister again. This time I was annoyed. “You can’t know,” I snapped. “I didn’t know myself until I got there and I haven’t mentioned it to a soul yet. If that girl Annie knows, she must be a clairvoyant.” Agatha Christie, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926)

4. Science fiction dialogue example ( Hyperion )

Dan Simmons’ Hyperion which won a Hugo Award was hailed as ‘The book that reinvented Space Opera’. Note the weaving in of dialogue between human and machine in the prologue:

‘We need your help,’ said Meina Gladstone. ‘It is essential that the secrets of the Time Tombs and Shrike be uncovered. This pilgrimage may be our last chance. If the Ousters conquer Hyperion, their agent must be eliminated and the Time Tombs sealed at all cost. The fate of the Hegemony may depend upon it.’ The transmission ended except for the pulse of rendezvous coordinates. ‘Response?’ asked the ship’s computer. Dan Simmons, Hyperion (1989).

5. Psychological thriller dialogue example ( Sharp Objects )

Notice how in Gillian Flynn’s debut Sharp Objects how even a simple conversation between reporter Camille Preaker and her editor at the St. Louis Chronicle who sends her back to her hometown on assignment is laced with a sense of tension and avoidance:

“Tell me about Wind Gap.” Curry held the tip of a ballpoint pen at his grizzled chin. I could picture the tiny prick of blue it would leave among the stubble. “It’s at the very bottom of Missouri, in the boot heel. Spitting distance from Tennessee and Arkansas,” I said, hustling for my facts. Curry loved to drill reporters on any topics he deemed pertinent – the number of murders in Chicago last year, the demographics for Cook County, or, for some reason, the story of my hometown, a topic I preferred to avoid. Gillian Flynn, Sharp Objects (2006).

6. Humor dialogue example ( Lessons in Chemistry )

See here how Bonnie Garmus weaves together humorous dialogue and character description to create the portrait of a man who does not have much luck in love:

“I can’t believe you’re having trouble,” his Cambridge teammates would tell him. “Girls love rowers.” Which wasn’t true. “And even though you’re an American, you’re not bad looking.” Which was also not true. Part of the problem was Calvin’s posture. He was six feet four inches tall, lanky and long, but he slouched to the right – probably a by-product of always rowing stroke side. Bonnie Garmus, Lessons in Chemistry (2022).

7. Historical/fantasy dialogue example ( The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue )

V.E. Schwab creates a sense of early, 17th Century times in this conversation about prayer and witches’ fates in her historical fantasy novel that involves immortality and contemporary romance:

“How do you talk to them?” she asks. “The old gods. Do you call them by name?” Estele straightens, joints cracking like dry sticks. If she’s surprised by the question, it doesn’t show. “They have no names.” “Is there a spell?” Estele gives her a pointed look. “Spells are for witches, and witches are too often burned.” V.E. Schwab, The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue (2020).

8. Literary fiction dialogue example ( Home )

Toni Morrison is a master of capturing the authentic ring of a real human voice. See the difference between the Reverend and his wife who dismisses his jaundiced view of the world as ‘foolishness’ in this dialogue example:

“You from down the street? At that hospital?” Frank nodded while stamping his feet and trying to rub life back into his fingers. Reverend Locke grunted. “Have a seat,” he said, then, shaking his head, added, “You lucky, Mr. Money. They sell a lot of bodies out of there.” “Bodies?” Frank sank down on the sofa, only vaguely caring or wondering what the man was talking about. “Uh-huh. To the medical school.” “They sell dead bodies? What for?” “Well, you know, doctors need to work on the dead poor so they can help the live rich.” “John, stop.” Jean Locke came down the stairs, tightening the belt of her robe. “That’s just foolishness.” Toni Morrison, Home (2012).

What is a favorite section of dialogue from a book in your favorite genre? Share in the comments below.

Join The Process for weekly feedback on dialogue and other writing, webinars on dialogue writing and other writing craft topic, and structured writing tools to brainstorm and develop your story.

Now Novel has been invaluable in helping me learn about the craft of novel writing. The feedback has been encouraging, insightful and useful. I’m sure I wouldn’t have got as far as I have without the support of Jordan and the writers in the groups. Highly recommend to anyone seeking help, support or encouragement with their first or next novel. – Oliver

Recommended Reading

Read further examples of effective dialogue:

- Dialogue writing examples from top books vs AI (2023)

- Writing conversations using setting (examples)

- 5 types of dialogue your novel needs

Related Posts:

- Realistic dialogue: Creating characters' speech patterns

- Writing process: From discovery to done (complete guide)

- Tags dialogue examples , dialogue tags , how to write dialogue

Jordan is a writer, editor, community manager and product developer. He received his BA Honours in English Literature and his undergraduate in English Literature and Music from the University of Cape Town.

37 replies on “Writing dialogue: Complete guide to storied speech”

Thank you for this! I notice these are all first person narratives; could you do something also with stories told in third person?

It’s a pleasure! Happily. While not on dialogue specifically, you might find this post on starting a story in third person helpful: https://www.nownovel.com/blog/how-to-start-a-novel-in-third-person/

“Very illuminating,” I said.

Thanks, Rob!

thanks this really helped

I’m thrilled to hear that, Randolyn. Thank you for the feedback.

As Rob said, very illuminating!

Do you have any recommendations on books with similar dialogue? Or should I give Tartt’s whole bibliography a go?

Thanks for the insight! Dialogue is one of my worker points in writing and I aim to correct that.

Hi Marco! It’s a pleasure. Tartt’s writing is very punchy, but there are many authors who write fantastic dialogue. Another great one is Toni Morrison – she’s a great master of every element of story, from exposition to dialogue to description and more.

Good luck, with focus I’m sure it’ll improve to the level you want it to be quickly.

This was immensely helpful. I’ve always handed dialogue fairly well, I think, but these tips will help me clean it up and use it to move the story forward, rather than just using it as page filler.

That’s great to hear, Brianna. I hope your current WIP is coming along well 🙂

yes helpfull

Hi Umer, thank you for the feedback. Good luck with your story!

Hello this is a nice example…….

Thanks, Joel!

This is truly helpful. Thanks!

I’m glad to hear that, April. It’s a pleasure! I hope you’re writing great dialogue.

I am doing a class project on figurative language and i need examples but short ones do you have any i could use

This was surprisingly helpful. I’m so glad I came across this website. Writing dialogue has always been something I’ve had difficulty doing, but these tips have significantly improved my dialogue writing. Thank you so much.

We’re glad to hear that, Prakhar! Keep writing 🙂

it is really usefull to me madam thank u so much

I’m glad to hear that, Manjunatha. Have a great weekend!

Thanks, Nathan, I’m glad to hear that.

kinda helpful to me 😀

I got my 18,5 mark from this Amazing ?

Fantastic, Chihab – do give yourself some of the credit! Well done.

Very useful to me… Thanks !!☺☺

It’s a pleasure, thank you for reading our articles and taking the time to share your feedback ?

[…] some dialogue writing tips at the following blog and evaluate them with some fellow […]

I want to know about the rule of using open quotation mark at the end of the dialogue 1 ‘We are not allowed to-‘

Hi Jagadishkk, thank you for sharing your question. From the example you’ve written, do you mean using interruption at the end of a line of dialogue? The way you’ve written that example is correct, you would usually use a dash with the interrupting person’s dialogue appearing immediately below on a new line (with indentation if indenting changes of speaker as is a common formatting style choice).

Hi I want you to help me with dialogue first draft

Hi Peggy, you can get constructive feedback from our community in our writing groups, they’re free to join. You can sign up here .

What is a favorite section of dialogue from a book in your favorite genre? Here is one of mine from “Bring up the bodies” by H. Mantel.

“Majesty, the Muscovites has taken three hundred miles of Polish territory. They say fifty thousand men are dead.” “Oh,” Henry says. “I hope they spare the libraries. The scholars. There are very fine scholars in Poland.” “Mm? Hope so too.”

Tells us something about Henry VIII — he “doesn’t give a hoot” about libraries and scholars in Poland or dead men.

Hi Nara, thanks so much for sharing that dialogue example. I like that Henry VIII seems preoccupied or disinterested in his responses, the simplicity of monosyllabic words and even how Mantel has him drop the subject ‘I’ to make it read more cursory, saying the bare minimum. He was probably too busy marrying and remarrying (and beheading) 🙂

Hey Jordan,

fantastic article, thank you very much – it helped me a lot, especially because i am translating my German Novel into English right now! However there is still an open question to me:

Here is an example/ little excerpt of my novel, which I already translated but kept the original German Formatting. I am asking myself if the colon can stay like this ( Then she said: ) or do I have to replace it with a comma ( Then she said, ) and begin with the dialogue in the next line. Here is the example ->>

After my mother echoed Michael’s exact words, she looked at me with a fixed gaze for several seconds. Then she said: “Do you understand now, Jordan, why I opened my eyes so wide just now?” “Yes… I feel as if he is here right now, Mother. I know him, but I don‘t know where…” “But now I really want to ask you, were you aware of his words, Jordan?”

I really hope you can help me with this little question. Thank you in advance 🙂

Greetings from Germany Yannic

Hi Yannic, thank you for your kind feedback, I’m glad you found this guide to dialogue helpful. One can use a colon or a comma to precede quoted speech. Technically, it is usual to only use a colon if the introductory words form an independent clause or the quotation is a complete sentence. Because the mother’s words fit this rule, a colon is totally acceptable in this case.

Good luck with your translation, that is quite the undertaking.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Pin It on Pinterest

Writing dialogue in a story requires us to step into the minds of our characters. When our characters speak, they should speak as fully developed human beings, complete with their own linguistic quirks and unique pronunciations.

Indeed, dialogue writing is essential to the art of storytelling . In real life, we learn about other people through their ideas and the words they use to express them. It is much the same for dialogue in fiction. Knowing how to write dialogue in a story will transform your character development , your prose style , and your story as a whole.

We’ve packed this article with dialogue writing tips and good examples of dialogue in a story. These tools will help your characters speak with their full uniqueness and complexity, while also helping you fully inhabit the people that populate your stories.

Let’s get into how to write dialogue effectively. First, what is dialogue in a story?

Inner Dialogue Definition

Indirect dialogue definition.

- How to Write Dialogue: Elements of Good Dialogue Writing

How to Write Dialogue in a Story: 4 DOs of Dialogue Writing

- How to Write Dialogue in a Story: 4 DON’Ts of Dialogue Writing

9 Devices for Writing Dialogue in a Story

Dialogue writing exercises, how to format dialogue, what is dialogue in a story.

Dialogue refers to any direct communication from one or more characters in the text. This communication is almost always verbal, except for instances of inner dialogue, where the character is speaking to themselves.

Dialogue definition: Direct communication from one or more characters in the text.

In works of Fantasy or Science Fiction, characters might communicate with each other telepathically or through non-human means. This would also count as dialogue in a story.

The importance of dialogue in a story cannot be overstated. The words that characters speak act as windows into their psyches: we can learn lots about people by what they say, as well as what they omit.

Additionally, dialogue allows for the exchange of information, which will advance the story’s plot. Any story that involves conflict between two or more people must involve dialogue, or else the story will never reach its climax and resolution.

Inner dialogue is a form of communication in which a character speaks with themselves. This is, essentially, a form of monologue or soliloquy . Inner dialogue allows the reader to view the character’s thoughts as they happen, transcribing their doubts, ideas, and emotions onto the page.

Inner dialogue definition: a form of communication in which a character speaks with themselves.

Inner dialogue can also be a memory or reminiscence, even if the character is not consciously speaking to themselves. If the narrator shows us a memory that the character is currently thinking about, then that character is still offering something to the narrative by means of unspoken conversation.

It is not necessary for any story to have inner dialogue. However, if you plan to use dynamic characters in your writing, then it probably makes sense to show the reader what that character’s inner world looks like. Developing complex, three dimensional characters is essential to telling a good story, which requires us to have some sort of window into those characters’ minds.

Indirect dialogue is dialogue, summarized. It is not put in quotes or italics; rather, it neatly sums up what a character said, without going into detail.

Indirect dialogue definition: dialogued, summarized.

In other words, we don’t get to see how the character said something , we are only told what they said. This is useful for when the information is better summarized than told in excruciating details, because the narrator wants to get to the important dialogue, the dialogue that introduces new information or reveals important aspects of the character’s personality.

Haruki Murakami gives us a great example in Kafka on the Shore :

I tell her that I’m actually fifteen, in junior high, that I stole my father’s money and ran away from my home in Nakano Ward in Tokyo. That I’m staying in a hotel in Takamatsu and spending my days reading at a library. That all of a sudden I found myself collapsed outside a shrine, covered in blood. Everything. Well, almost everything. Not the important stuff I can’t talk about.

How to Write Dialogue: The Elements of Good Dialogue Writing

Every story needs dialogue. Unless you’re writing highly experimental fiction , your story will have main characters, and those characters will interact with the world and its other people.

That said, there’s no “correct” way to write dialogue. It all depends on who your characters are, the decisions they make, and how they interact with one another.

Nonetheless, good dialogue writing should do the following:

Develop Your Characters

A close study in how to write dialogue requires a close study in characterization. Your characters reveal who they are through dialogue: by paying close attention to your characters’ word choice , you can clue your reader into their personality traits and hidden psyches.

Your characters will often reveal key aspects of their personality through dialogue.

One character who can’t stop characterizing himself is Holden Caulfield from The Catcher in the Rye . J. D. Salinger’s anti-hero could be psychoanalyzed for hours. Take, for example, this excerpt from Holden’s inner dialogue:

“Grand. There’s a word I really hate. It’s a phony. I could puke every time I hear it.”

What do we learn about Holden through this line? For starters, we learn that Holden is the type of person who analyzes and scrutinizes each word – just like writers do, perhaps. We also learn that Holden hates anything positive. Always a downer, Holden despises words of praise or grandeur, thinking the whole world is irresolvably flat, boring, and monotonous. He hates grandness almost as much as he hates phoniness, and both concepts are sure to make him sick.

Holden is a character who puts his entire personality on the page, and as readers, we can’t help but understand him – no matter how much we like him or hate him.

Set the Scene

Dialogue is a great way to explore the setting of your story. When the setting is explored through dialogue writing, both the characters and the reader experience the world of the story at the same time, making the writing feel more intimate and immediate.

When the setting is explored through dialogue writing, the writing feels more intimate and immediate.

You might have your character wander through the streets of New York, as Theo does in The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt. Here’s an excerpt of inner dialogue:

“It was rainy, trees leafing out, spring deepening into summer; and the forlorn cry of horns on the street, the dank smell of the wet pavement had an electricity about it, a sense of crowds and static, lonely secretaries and fat guys with bags of carry-out, everywhere the ungainly sadness of creatures pushing and struggling to live.”

Notice Theo’s attention to detail, and the vibrant imagery he uses to capture the city’s energy. Of course, you might set the scene more simply, as Dorothy does when she says:

“Toto, I’ve a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore.”

In only a few words, this line of dialogue advances not only the setting but also Dorothy’s characterization. She is innocent and operating from a limited frame of reference, and the setting could not be more different from her homely Kansas background.

Both methods of scene setting help advance the world that the reader is exploring. However, don’t explore the setting exclusively through dialogue. Characters are not objective observers of their world, so some information is better explained through narration since the narrator is (often) a more reliable voice.

Advance the Plot

Dialogue doesn’t just tell us about the story and the people inside it; good dialogue writing also advances the plot . We often need dialogue to reveal important details to the protagonist , and sometimes, an emotionally tense conversation will lead to the next event in the story.

At times, dialogue will advance the plot by offering a twist or revealing sudden information. We can all agree that the following lines of dialogue advanced the plot of Star Wars :

“Obi-Wan never told you what happened to your father.”

“He told me enough! He told me you killed him!”

“No. I am your father.”

And the following bit of dialogue catalyzed the plot of the entire Harry Potter series:

“You’re a wizard, Harry.”

The exchange of information is often what accelerates (0r resolves) a story’s conflict. Paying attention to word choice and the strategic revelation of information is key to using dialogue in a story.

Just like in real life, your characters don’t always say what they mean. Characters can lie, hint, suggest, confuse, conceal, and deceive. But one of the most powerful uses of dialogue writing is to foreshadow future events.

In Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet , Romeo foreshadows the death of both lovers when he exclaims to Juliet:

“Life were better ended by their hate, / Than death prorogued, wanting of thy love.”

In saying he would rather die lovers than live in longing, Romeo unknowingly predicts what will soon happen in the play.

Foreshadowing is an important literary device that many fiction stories should utilize. Foreshadowing helps build suspense in the story, and it also underlines the important events that make your story worth reading. Don’t try to trick your readers, but definitely use foreshadowing to keep them reading.

Learn more about foreshadowing here:

Foreshadowing Definition: How to Use Foreshadowing in Your Fiction

We’ve talked about what dialogue writing should accomplish, but that doesn’t answer the question of how to write dialogue in a story. Let’s answer that question now—with some more dialogue writing examples in the mix.

1. How to Write Dialogue in a Story: Differentiate Each Character

Each character will have their own style of speaking, and will emphasize different things when they talk.

Your characters’ dialogue should be like thumbprints, because no two people are alike. Each character will have their own style of speaking, and will emphasize different things when they talk. You can make each character unique by altering the following elements of dialogue style:

- Sentence length: Some people are verbose and loquacious, others terse and stoic.

- Dialogue Punctuation: Do your characters let their sentences linger… or do they ask a lot of questions? Are they really excited all the time?! Or do they interrupt themselves frequently—always remembering something they forgot to mention—struggling to put their complex thoughts into words?

- Adjectives/adverbs: Characters that are expressive and verbose tend to use a lot of adjectives and adverbs, whereas characters that are quiet or less expressive might stick to their nouns and verbs.

- Spellings and pronunciation: Do your characters omit certain vowels? Do they lisp? The way you write a line of dialogue might reveal a character’s dialect, and adding consistent quirks to a character’s speech will certainly make them more memorable.

- Repetitions and emphasis: Do your characters have any catchphrases? Do they use any words or phrases as crutches? Maybe they emphasize words periodically, or have a strange cadence as they speak. We tend to repeat certain words and phrases in our own everyday vocabularies; repetition is also a useful device for writing dialogue in a story.

You’ve already seen character differentiation from the previous quotes in this article. In this scene from The Catcher in the Rye , notice how differently Holden Caulfield speaks from the young woman he’s talking to—and just how much characterization is implied in their divergent voices:

“You don’t come from New York, do you?” I said finally. That’s all I could think of.

“Hollywood,” she said. Then she got up and went over to where she’d put her dress down, on the bed. “Ya got a hanger? I don’t want to get my dress all wrinkly. It’s brand-clean.”

“Sure,” I said right away. I was only too glad to get up and do something.

Aside from these two characters being different from one another, Holden speak differently than characters in other works of fiction. Can you imagine Holden Caulfield being Romeo in R&J ? He’d say something stupid, like “Juliet’s family are all phonies, but the funny thing is you can’t help but fall half in love with her.”

A more contemporary example comes from White Teeth by Zadie Smith. Every character in this novel is exceptionally well differentiated, even the minor characters—like Brother Ibrahim ad-Din Shukrallah, who appears only briefly towards the novel’s end. Here’s an excerpt:

“Look around you. And what do you see? What is the result of this so-called democracy, this so-called freedom, this so-called liberty ? Oppression, persecution, slaughter . Brothers, you can see it on national television every day, every evening, every night ! Chaos, disorder, confusion . They are not ashamed or embarrassed or self-conscious ! They don’t try to hide, to conceal, to disguise . They know as we know: the entire world is in a turmoil!”

Pay attention to the dialogue. What do you notice? What’s odd about the way he speaks? If you don’t notice it, the novel’s narrator gives us a hint:

“No one in the hall was going to admit it, but Brother Ibrahim ad-Din Shukrallah was no great speaker, when you got down to it. Even if you overlooked his habit of using three words where one would do, of emphasizing the last word of such triplets with his see-saw Caribbean inflections, even if you ignored these as everybody tried to, he was still physically disappointing.”

For more advice on characterization, check out our article on character development.

https://writers.com/character-development-definition

2. How to Write Dialogue in a Story: Consider the Context

A common mistake writers often make when writing dialogue in a story: they use the same speaking style for that character throughout the entire story.

For example, if you have a character that tends to speak in wordy, roundabout sentences, you might think that every sentence of dialogue should be wordy and roundabout.

However, your character’s dialogue needs to take context into consideration. A wordy character probably won’t be so wordy if they’re being held at gunpoint, and their words might stammer or falter when talking to a crush. Or, in the case of Jane Eyre , the context might make your statement more powerful. Jane proclaims:

“Do you think, because I am poor, obscure, plain and little, I am soulless and heartless? You think wrong! I have as much soul as you—and full as much heart!”

As she lives in a society with strict gender roles, Jane’s statement—to a man, no less—is thrillingly bold and controversial for its time.

Your characters aren’t monotonous, they’re dynamic and fluid, so let them speak according to their surroundings.

3. How to Write Dialogue in a Story: Space Out Moments of Dialogue

If your characters just had a lengthy conversation, give them a page or two before they start speaking again. Dialogue is an important part of storytelling, but equally important is narration and description.

The following excerpt from Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy has a great balance of dialogue (underlined) and narration.

“Are there any papers from the office?” asked Stepan Arkadyevitch, taking the telegram and seating himself at the looking-glass.

“On the table,” replied Matvey, glancing with inquiring sympathy at his master; and, after a short pause, he added with a sly smile, “ They’ve sent from the carriage-jobbers.”

Stepan Arkadyevitch made no reply, he merely glanced at Matvey in the looking-glass. In the glance, in which their eyes met in the looking-glass, it was clear that they understood one another. Stepan Arkadyevitch’s eyes asked: “Why do you tell me that? don’t you know?”

Matvey put his hands in his jacket pockets, thrust out one leg, and gazed silently, good-humoredly, with a faint smile, at his master.

“I told them to come on Sunday, and till then not to trouble you or themselves for nothing,” he said. He had obviously prepared the sentence beforehand.

You can see, in the above text, that about 1/3 of the writing is dialogue. This allows the reader to see the full scene while still viewing the conversation, making this an excellent balance of narration and dialogue writing.

Simply put: balance dialogue with your narrator’s voice, or else the reader might lose their attention, or else miss out on key information.

4. How to Write Dialogue in a Story: Use Consistent Formatting

There are several different ways to format your dialogue, which we explain later in this article. For now, make sure you’re consistent with how you format your dialogue. If you choose to indent your characters’ speech, make sure every new exchange is indented. Inconsistent formatting will throw the reader out of the story, and it could also prevent your story from being published.

How to Write Dialogue in a Story: 4 DON’Ts of Dialogue Writing

Just as important as the DOs, the DON’Ts of dialogue writing are just as important to crafting an effective story. Let’s further our discussion of how to write dialogue in a story: we’ll dive into what you shouldn’t do when writing dialogue, alongside some more dialogue examples.

1. DON’T Include Every Verbal Interjection

When people talk, they don’t always talk linearly. People interrupt themselves, they change direction, they forget what they were talking about, they use pauses and “ums” and “ohs” and “ehs.” You can include a few of these verbal interjections from time to time, but don’t make your dialogue too true-to-life. Otherwise, the dialogue becomes hard to read, and the reader loses interest.

Let’s take a famous line from The Catcher in the Rye and fill it in with verbal interjections.

“I have a feeling that you are riding for some kind of a terrible, terrible fall. But I don’t honestly know what kind.”

With interjections:

Oh, man—I have a feeling, like, that you are riding for some kind of… a terrible, terrible fall. But, uh, I don’t honestly know what kind?

What do you think of the edited quote? The interjections make it much harder to read, much less personable, and honestly, they become kind of annoying. However, the quote with interjections is much more “true to life” than the original quote. Your characters don’t need to speak perfectly, but the dialogue needs to be enjoyable to read.

2. DON’T Overwrite Dialogue Tags

Dialogue tags are how your character expresses what they say. In the quote “‘You’re all phonies,’ Holden said,” the dialogue tag is “Holden said.”

Unique dialogue tags are fine to use on occasion. Your characters might yell, stammer, whisper, or even explode with words! However, don’t use these tags too frequently—the tag “said” is often perfectly fine. Notice how overused dialogue tags ruin the following conversation:

“How are you?” I stammered.

“Great! How are you?” she inquired.

“I’m hungry,” I announced.

“We should get lunch,” she blurted.

“I’m on a diet,” I cried.

“You poor thing,” she rejoined.

Sure, the conversation isn’t interesting to begin with, but the dialogue tags make this writing cringe-worthy. All of this dialogue can be described with “said” or “replied,” and many of these quotes don’t even need dialogue tags, because it’s clear who’s speaking each time.

This is doubly serious when dialogue tags are combined with adverbs : adjectives that modify the verbs themselves. Our intent with these adverbs is to intensify our writing, but what results is a strong case of diminishing returns. Let’s see an example:

“I don’t love you anymore,” she said.

“I don’t love you anymore,” she spat contemptuously.

Yikes! If your dialogue tags start distracting the reader, then your dialogue isn’t doing enough work on its own. The reader’s focus should be on the character’s statement, not on the way they delivered that statement. If she spoke those words with contempt, show the reader this in the dialogue itself, or even in the character’s body language.

Lastly: if you’re going to use a dialogue tag other than “said,” make sure the verb you use actually corresponds to dialogue. In other words, there needs to be a speaking verb before you describe some other sort of action.

Here’s an example of what NOT to do:

“I don’t love you anymore,” she stomped.

She might have stomped while saying that line, but “to stomp” is not a kind of communication.

The dialogue tag “said” is perfectly fine for most situations.

3. DON’T Stereotype

Everybody’s speech has a myriad of influences. Your characters’ way of speaking will be influenced by their parents, upbringing, schooling, socioeconomic status, race, gender, sexual orientation, and their own unique personality traits.

Of course, these personal backgrounds will influence your character’s dialogue. However, you shouldn’t let those traits overpower the character’s dialogue—otherwise, you’ll end up stereotyping.

Stereotyped characters are both glaringly obvious and embarrassing for the author. For example, J. K. Rowling didn’t do herself any favors by naming a character Cho Chang—both of which are Korean last names. Similarly, if all of your male characters are strong, charismatic, and loud, while all of your female characters are meek, helpless, and insecure, your writing will be both offensive and inaccurate to life.

Let’s explore this with two ways of writing a policeman.

“Don’t stand here,” said the policeman in front of the caution tape. “We need to keep this street clear.”

And here is lazy writing that takes no real interest in the character beyond one-dimensional surface traits:

“Move it along, folks, move it along,” said the policeman in front of the caution tape. “Nothing to see here.”

Neither policeman is going to win a dialogue award, but the second policeman doesn’t even seem like a real person . He’s written in unconsidered cliché: phrases we’ve all heard a thousand times, general ideas of what policemen tend to say.