Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Focus Group? | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

What is a Focus Group | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Published on December 10, 2021 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

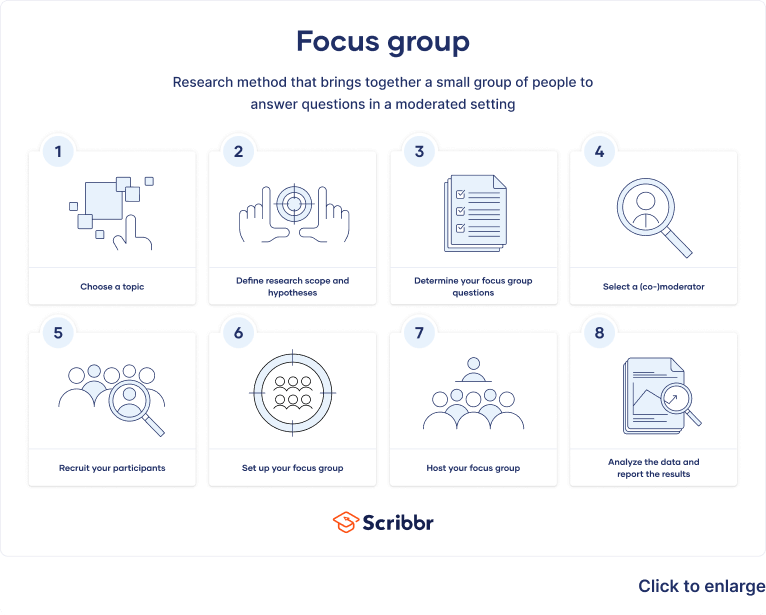

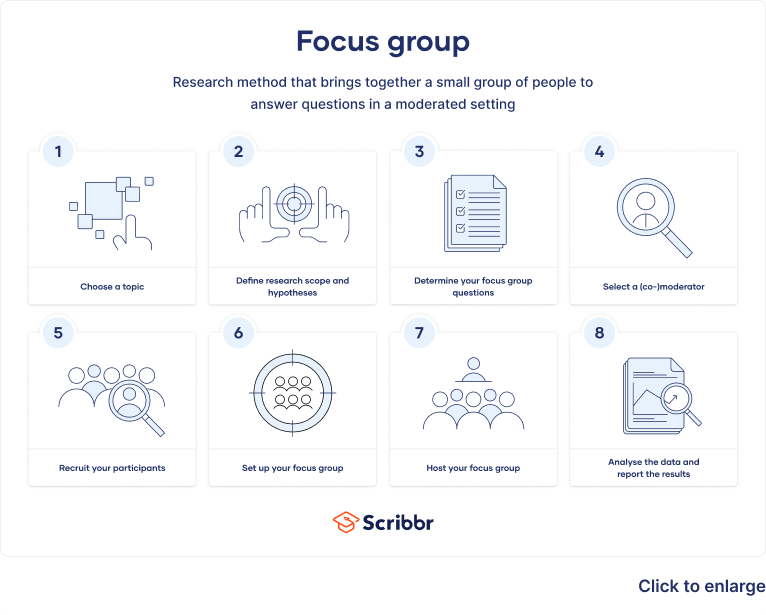

A focus group is a research method that brings together a small group of people to answer questions in a moderated setting. The group is chosen due to predefined demographic traits, and the questions are designed to shed light on a topic of interest.

Table of contents

What is a focus group, step 1: choose your topic of interest, step 2: define your research scope and hypotheses, step 3: determine your focus group questions, step 4: select a moderator or co-moderator, step 5: recruit your participants, step 6: set up your focus group, step 7: host your focus group, step 8: analyze your data and report your results, advantages and disadvantages of focus groups, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about focus groups.

Focus groups are a type of qualitative research . Observations of the group’s dynamic, their answers to focus group questions, and even their body language can guide future research on consumer decisions, products and services, or controversial topics.

Focus groups are often used in marketing, library science, social science, and user research disciplines. They can provide more nuanced and natural feedback than individual interviews and are easier to organize than experiments or large-scale surveys .

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Focus groups are primarily considered a confirmatory research technique . In other words, their discussion-heavy setting is most useful for confirming or refuting preexisting beliefs. For this reason, they are great for conducting explanatory research , where you explore why something occurs when limited information is available.

A focus group may be a good choice for you if:

- You’re interested in real-time, unfiltered responses on a given topic or in the dynamics of a discussion between participants

- Your questions are rooted in feelings or perceptions , and cannot easily be answered with “yes” or “no”

- You’re confident that a relatively small number of responses will answer your question

- You’re seeking directional information that will help you uncover new questions or future research ideas

- Structured interviews : The questions are predetermined in both topic and order.

- Semi-structured interviews : A few questions are predetermined, but other questions aren’t planned.

- Unstructured interviews : None of the questions are predetermined.

Differences between types of interviews

Make sure to choose the type of interview that suits your research best. This table shows the most important differences between the four types.

| Structured interview | Semi-structured interview | Unstructured interview | Focus group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed questions | ||||

| Fixed order of questions | ||||

| Fixed number of questions | ||||

| Option to ask additional questions |

Topics favorable to focus groups

As a rule of thumb, research topics related to thoughts, beliefs, and feelings work well in focus groups. If you are seeking direction, explanation, or in-depth dialogue, a focus group could be a good fit.

However, if your questions are dichotomous or if you need to reach a large audience quickly, a survey may be a better option. If your question hinges upon behavior but you are worried about influencing responses, consider an observational study .

- If you want to determine whether the student body would regularly consume vegan food, a survey would be a great way to gauge student preferences.

However, food is much more than just consumption and nourishment and can have emotional, cultural, and other implications on individuals.

- If you’re interested in something less concrete, such as students’ perceptions of vegan food or the interplay between their choices at the dining hall and their feelings of homesickness or loneliness, perhaps a focus group would be best.

Once you have determined that a focus group is the right choice for your topic, you can start thinking about what you expect the group discussion to yield.

Perhaps literature already exists on your subject or a sufficiently similar topic that you can use as a starting point. If the topic isn’t well studied, use your instincts to determine what you think is most worthy of study.

Setting your scope will help you formulate intriguing hypotheses , set clear questions, and recruit the right participants.

- Are you interested in a particular sector of the population, such as vegans or non-vegans?

- Are you interested in including vegetarians in your analysis?

- Perhaps not all students eat at the dining hall. Will your study exclude those who don’t?

- Are you only interested in students who have strong opinions on the subject?

A benefit of focus groups is that your hypotheses can be open-ended. You can be open to a wide variety of opinions, which can lead to unexpected conclusions.

The questions that you ask your focus group are crucially important to your analysis. Take your time formulating them, paying special attention to phrasing. Be careful to avoid leading questions , which can affect your responses.

Overall, your focus group questions should be:

- Open-ended and flexible

- Impossible to answer with “yes” or “no” (questions that start with “why” or “how” are often best)

- Unambiguous, getting straight to the point while still stimulating discussion

- Unbiased and neutral

If you are discussing a controversial topic, be careful that your questions do not cause social desirability bias . Here, your respondents may lie about their true beliefs to mask any socially unacceptable or unpopular opinions. This and other demand characteristics can hurt your analysis and lead to several types of reseach bias in your results, particularly if your participants react in a different way once knowing they’re being observed. These include self-selection bias , the Hawthorne effect , the Pygmalion effect , and recall bias .

- Engagement questions make your participants feel comfortable and at ease: “What is your favorite food at the dining hall?”

- Exploration questions drill down to the focus of your analysis: “What pros and cons of offering vegan options do you see?”

- Exit questions pick up on anything you may have previously missed in your discussion: “Is there anything you’d like to mention about vegan options in the dining hall that we haven’t discussed?”

It is important to have more than one moderator in the room. If you would like to take the lead asking questions, select a co-moderator who can coordinate the technology, take notes, and observe the behavior of the participants.

If your hypotheses have behavioral aspects, consider asking someone else to be lead moderator so that you are free to take a more observational role.

Depending on your topic, there are a few types of moderator roles that you can choose from.

- The most common is the dual-moderator , introduced above.

- Another common option is the dueling-moderator style . Here, you and your co-moderator take opposing sides on an issue to allow participants to see different perspectives and respond accordingly.

Depending on your research topic, there are a few sampling methods you can choose from to help you recruit and select participants.

- Voluntary response sampling , such as posting a flyer on campus and finding participants based on responses

- Convenience sampling of those who are most readily accessible to you, such as fellow students at your university

- Stratified sampling of a particular age, race, ethnicity, gender identity, or other characteristic of interest to you

- Judgment sampling of a specific set of participants that you already know you want to include

Beware of sampling bias and selection bias , which can occur when some members of the population are more likely to be included than others.

Number of participants

In most cases, one focus group will not be sufficient to answer your research question. It is likely that you will need to schedule three to four groups. A good rule of thumb is to stop when you’ve reached a saturation point (i.e., when you aren’t receiving new responses to your questions).

Most focus groups have 6–10 participants. It’s a good idea to over-recruit just in case someone doesn’t show up. As a rule of thumb, you shouldn’t have fewer than 6 or more than 12 participants, in order to get the most reliable results.

Lastly, it’s preferable for your participants not to know you or each other, as this can bias your results.

A focus group is not just a group of people coming together to discuss their opinions. While well-run focus groups have an enjoyable and relaxed atmosphere, they are backed up by rigorous methods to provide robust observations.

Confirm a time and date

Be sure to confirm a time and date with your participants well in advance. Focus groups usually meet for 45–90 minutes, but some can last longer. However, beware of the possibility of wandering attention spans. If you really think your session needs to last longer than 90 minutes, schedule a few breaks.

Confirm whether it will take place in person or online

You will also need to decide whether the group will meet in person or online. If you are hosting it in person, be sure to pick an appropriate location.

- An uncomfortable or awkward location may affect the mood or level of participation of your group members.

- Online sessions are convenient, as participants can join from home, but they can also lessen the connection between participants.

As a general rule, make sure you are in a noise-free environment that minimizes distractions and interruptions to your participants.

Consent and ethical considerations

It’s important to take into account ethical considerations and informed consent when conducting your research. Informed consent means that participants possess all the information they need to decide whether they want to participate in the research before it starts. This includes information about benefits, risks, funding, and institutional approval.

Participants should also sign a release form that states that they are comfortable with being audio- or video-recorded. While verbal consent may be sufficient, it is best to ask participants to sign a form.

A disadvantage of focus groups is that they are too small to provide true anonymity to participants. Make sure that your participants know this prior to participating.

There are a few things you can do to commit to keeping information private. You can secure confidentiality by removing all identifying information from your report or offer to pseudonymize the data later. Data pseudonymization entails replacing any identifying information about participants with pseudonymous or false identifiers.

Preparation prior to participation

If there is something you would like participants to read, study, or prepare beforehand, be sure to let them know well in advance. It’s also a good idea to call them the day before to ensure they will still be participating.

Consider conducting a tech check prior to the arrival of your participants, and note any environmental or external factors that could affect the mood of the group that day. Be sure that you are organized and ready, as a stressful atmosphere can be distracting and counterproductive.

Starting the focus group

Welcome individuals to the focus group by introducing the topic, yourself, and your co-moderator, and go over any ground rules or suggestions for a successful discussion. It’s important to make your participants feel at ease and forthcoming with their responses.

Consider starting out with an icebreaker, which will allow participants to relax and settle into the space a bit. Your icebreaker can be related to your study topic or not; it’s just an exercise to get participants talking.

Leading the discussion

Once you start asking your questions, try to keep response times equal between participants. Take note of the most and least talkative members of the group, as well as any participants with particularly strong or dominant personalities.

You can ask less talkative members questions directly to encourage them to participate or ask participants questions by name to even the playing field. Feel free to ask participants to elaborate on their answers or to give an example.

As a moderator, strive to remain neutral . Refrain from reacting to responses, and be aware of your body language (e.g., nodding, raising eyebrows) and the possibility for observer bias . Active listening skills, such as parroting back answers or asking for clarification, are good methods to encourage participation and signal that you’re listening.

Many focus groups offer a monetary incentive for participants. Depending on your research budget, this is a nice way to show appreciation for their time and commitment. To keep everyone feeling fresh, consider offering snacks or drinks as well.

After concluding your focus group, you and your co-moderator should debrief, recording initial impressions of the discussion as well as any highlights, issues, or immediate conclusions you’ve drawn.

The next step is to transcribe and clean your data . Assign each participant a number or pseudonym for organizational purposes. Transcribe the recordings and conduct content analysis to look for themes or categories of responses. The categories you choose can then form the basis for reporting your results.

Just like other research methods, focus groups come with advantages and disadvantages.

- They are fairly straightforward to organize and results have strong face validity .

- They are usually inexpensive, even if you compensate participant.

- A focus group is much less time-consuming than a survey or experiment , and you get immediate results.

- Focus group results are often more comprehensible and intuitive than raw data.

Disadvantages

- It can be difficult to assemble a truly representative sample. Focus groups are generally not considered externally valid due to their small sample sizes.

- Due to the small sample size, you cannot ensure the anonymity of respondents, which may influence their desire to speak freely.

- Depth of analysis can be a concern, as it can be challenging to get honest opinions on controversial topics.

- There is a lot of room for error in the data analysis and high potential for observer dependency in drawing conclusions. You have to be careful not to cherry-pick responses to fit a prior conclusion.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

A focus group is a research method that brings together a small group of people to answer questions in a moderated setting. The group is chosen due to predefined demographic traits, and the questions are designed to shed light on a topic of interest. It is one of 4 types of interviews .

As a rule of thumb, questions related to thoughts, beliefs, and feelings work well in focus groups. Take your time formulating strong questions, paying special attention to phrasing. Be careful to avoid leading questions , which can bias your responses.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Every dataset requires different techniques to clean dirty data , but you need to address these issues in a systematic way. You focus on finding and resolving data points that don’t agree or fit with the rest of your dataset.

These data might be missing values, outliers, duplicate values, incorrectly formatted, or irrelevant. You’ll start with screening and diagnosing your data. Then, you’ll often standardize and accept or remove data to make your dataset consistent and valid.

The four most common types of interviews are:

- Structured interviews : The questions are predetermined in both topic and order.

- Focus group interviews : The questions are presented to a group instead of one individual.

It’s impossible to completely avoid observer bias in studies where data collection is done or recorded manually, but you can take steps to reduce this type of bias in your research .

Scope of research is determined at the beginning of your research process , prior to the data collection stage. Sometimes called “scope of study,” your scope delineates what will and will not be covered in your project. It helps you focus your work and your time, ensuring that you’ll be able to achieve your goals and outcomes.

Defining a scope can be very useful in any research project, from a research proposal to a thesis or dissertation . A scope is needed for all types of research: quantitative , qualitative , and mixed methods .

To define your scope of research, consider the following:

- Budget constraints or any specifics of grant funding

- Your proposed timeline and duration

- Specifics about your population of study, your proposed sample size , and the research methodology you’ll pursue

- Any inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Any anticipated control , extraneous , or confounding variables that could bias your research if not accounted for properly.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, June 22). What is a Focus Group | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 23, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/focus-group/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what is qualitative research | methods & examples, explanatory research | definition, guide, & examples, data collection | definition, methods & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Focus Groups – Steps, Examples and Guide

Focus Groups – Steps, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

Focus Group

Definition:

A focus group is a qualitative research method used to gather in-depth insights and opinions from a group of individuals about a particular product, service, concept, or idea.

The focus group typically consists of 6-10 participants who are selected based on shared characteristics such as demographics, interests, or experiences. The discussion is moderated by a trained facilitator who asks open-ended questions to encourage participants to share their thoughts, feelings, and attitudes towards the topic.

Focus groups are an effective way to gather detailed information about consumer behavior, attitudes, and perceptions, and can provide valuable insights to inform decision-making in a range of fields including marketing, product development, and public policy.

Types of Focus Group

The following are some types or methods of Focus Groups:

Traditional Focus Group

This is the most common type of focus group, where a small group of people is brought together to discuss a particular topic. The discussion is typically led by a skilled facilitator who asks open-ended questions to encourage participants to share their thoughts and opinions.

Mini Focus Group

A mini-focus group involves a smaller group of participants, typically 3 to 5 people. This type of focus group is useful when the topic being discussed is particularly sensitive or when the participants are difficult to recruit.

Dual Moderator Focus Group

In a dual-moderator focus group, two facilitators are used to manage the discussion. This can help to ensure that the discussion stays on track and that all participants have an opportunity to share their opinions.

Teleconference or Online Focus Group

Teleconferences or online focus groups are conducted using video conferencing technology or online discussion forums. This allows participants to join the discussion from anywhere in the world, making it easier to recruit participants and reducing the cost of conducting the focus group.

Client-led Focus Group

In a client-led focus group, the client who is commissioning the research takes an active role in the discussion. This type of focus group is useful when the client has specific questions they want to ask or when they want to gain a deeper understanding of their customers.

The following Table can explain Focus Group types more clearly

| Type of Focus Group | Number of Participants | Duration | Types of Questions | Geographical Area | Analysis Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional | 6-12 | 1-2 hours | Open-ended | Local | Thematic Analysis |

| Mini | 3-5 | 1-2 hours | Closed-ended | Local | Content Analysis |

| Dual Moderator | 6-12 | 1-2 hours | Combination of open- and closed-ended | Regional | Discourse Analysis |

| Teleconference/Online | 6-12 | 1-2 hours | Open-ended | National/International | Conversation Analysis |

| Client-Led | 6-12 | 1-2 hours | Combination of open- and closed-ended | Local/Regional | Thematic Analy |

How To Conduct a Focus Group

To conduct a focus group, follow these general steps:

Define the Research Question

Identify the key research question or objective that you want to explore through the focus group. Develop a discussion guide that outlines the topics and questions you want to cover during the session.

Recruit Participants

Identify the target audience for the focus group and recruit participants who meet the eligibility criteria. You can use various recruitment methods such as social media, online panels, or referrals from existing customers.

Select a Venue

Choose a location that is convenient for the participants and has the necessary facilities such as audio-visual equipment, seating, and refreshments.

Conduct the Session

During the focus group session, introduce the topic, and review the objectives of the research. Encourage participants to share their thoughts and opinions by asking open-ended questions and probing deeper into their responses. Ensure that the discussion remains on topic and that all participants have an opportunity to contribute.

Record the Session

Use audio or video recording equipment to capture the discussion. Note-taking is also essential to ensure that you capture all key points and insights.

Analyze the data

Once the focus group is complete, transcribe and analyze the data. Look for common themes, patterns, and insights that emerge from the discussion. Use this information to generate insights and recommendations that can be applied to the research question.

When to use Focus Group Method

The focus group method is typically used in the following situations:

Exploratory Research

When a researcher wants to explore a new or complex topic in-depth, focus groups can be used to generate ideas, opinions, and insights.

Product Development

Focus groups are often used to gather feedback from consumers about new products or product features to help identify potential areas for improvement.

Marketing Research

Focus groups can be used to test marketing concepts, messaging, or advertising campaigns to determine their effectiveness and appeal to different target audiences.

Customer Feedback

Focus groups can be used to gather feedback from customers about their experiences with a particular product or service, helping companies improve customer satisfaction and loyalty.

Public Policy Research

Focus groups can be used to gather public opinions and attitudes on social or political issues, helping policymakers make more informed decisions.

Examples of Focus Group

Here are some real-time examples of focus groups:

- A tech company wants to improve the user experience of their mobile app. They conduct a focus group with a diverse group of users to gather feedback on the app’s design, functionality, and features. The focus group consists of 8 participants who are selected based on their age, gender, ethnicity, and level of experience with the app. During the session, a trained facilitator asks open-ended questions to encourage participants to share their thoughts and opinions on the app. The facilitator also observes the participants’ behavior and reactions to the app’s features. After the focus group, the data is analyzed to identify common themes and issues raised by the participants. The insights gathered from the focus group are used to inform improvements to the app’s design and functionality, with the goal of creating a more user-friendly and engaging experience for all users.

- A car manufacturer wants to develop a new electric vehicle that appeals to a younger demographic. They conduct a focus group with millennials to gather their opinions on the design, features, and pricing of the vehicle.

- A political campaign team wants to develop effective messaging for their candidate’s campaign. They conduct a focus group with voters to gather their opinions on key issues and identify the most persuasive arguments and messages.

- A restaurant chain wants to develop a new menu that appeals to health-conscious customers. They conduct a focus group with fitness enthusiasts to gather their opinions on the types of food and drinks that they would like to see on the menu.

- A healthcare organization wants to develop a new wellness program for their employees. They conduct a focus group with employees to gather their opinions on the types of programs, incentives, and support that would be most effective in promoting healthy behaviors.

- A clothing retailer wants to develop a new line of sustainable and eco-friendly clothing. They conduct a focus group with environmentally conscious consumers to gather their opinions on the design, materials, and pricing of the clothing.

Purpose of Focus Group

The key objectives of a focus group include:

Generating New Ideas and insights

Focus groups are used to explore new or complex topics in-depth, generating new ideas and insights that may not have been previously considered.

Understanding Consumer Behavior

Focus groups can be used to gather information on consumer behavior, attitudes, and perceptions to inform marketing and product development strategies.

Testing Concepts and Ideas

Focus groups can be used to test marketing concepts, messaging, or product prototypes to determine their effectiveness and appeal to different target audiences.

Gathering Customer Feedback

Informing decision-making.

Focus groups can provide valuable insights to inform decision-making in a range of fields including marketing, product development, and public policy.

Advantages of Focus Group

The advantages of using focus groups are:

- In-depth insights: Focus groups provide in-depth insights into the attitudes, opinions, and behaviors of a target audience on a specific topic, allowing researchers to gain a deeper understanding of the issues being explored.

- Group dynamics: The group dynamics of focus groups can provide additional insights, as participants may build on each other’s ideas, share experiences, and debate different perspectives.

- Efficient data collection: Focus groups are an efficient way to collect data from multiple individuals at the same time, making them a cost-effective method of research.

- Flexibility : Focus groups can be adapted to suit a range of research objectives, from exploratory research to concept testing and customer feedback.

- Real-time feedback: Focus groups provide real-time feedback on new products or concepts, allowing researchers to make immediate adjustments and improvements based on participant feedback.

- Participant engagement: Focus groups can be a more engaging and interactive research method than surveys or other quantitative methods, as participants have the opportunity to express their opinions and interact with other participants.

Limitations of Focus Groups

While focus groups can provide valuable insights, there are also some limitations to using them.

- Small sample size: Focus groups typically involve a small number of participants, which may not be representative of the broader population being studied.

- Group dynamics : While group dynamics can be an advantage of focus groups, they can also be a limitation, as dominant personalities may sway the discussion or participants may not feel comfortable expressing their true opinions.

- Limited generalizability : Because focus groups involve a small sample size, the results may not be generalizable to the broader population.

- Limited depth of responses: Because focus groups are time-limited, participants may not have the opportunity to fully explore or elaborate on their opinions or experiences.

- Potential for bias: The facilitator of a focus group may inadvertently influence the discussion or the selection of participants may not be representative, leading to potential bias in the results.

- Difficulty in analysis : The qualitative data collected in focus groups can be difficult to analyze, as it is often subjective and requires a skilled researcher to interpret and identify themes.

Characteristics of Focus Group

- Small group size: Focus groups typically involve a small number of participants, ranging from 6 to 12 people. This allows for a more in-depth and focused discussion.

- Targeted participants: Participants in focus groups are selected based on specific criteria, such as age, gender, or experience with a particular product or service.

- Facilitated discussion: A skilled facilitator leads the discussion, asking open-ended questions and encouraging participants to share their thoughts and experiences.

- I nteractive and conversational: Focus groups are interactive and conversational, with participants building on each other’s ideas and responding to one another’s opinions.

- Qualitative data: The data collected in focus groups is qualitative, providing detailed insights into participants’ attitudes, opinions, and behaviors.

- Non-threatening environment: Participants are encouraged to share their thoughts and experiences in a non-threatening and supportive environment.

- Limited time frame: Focus groups are typically time-limited, lasting between 1 and 2 hours, to ensure that the discussion stays focused and productive.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

Correlational Research – Methods, Types and...

Research Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

Qualitative Research Methods

Applied Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Mixed Methods Research – Types & Analysis

What Is a Focus Group?

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

A focus group is a qualitative research method that involves facilitating a small group discussion with participants who share common characteristics or experiences that are relevant to the research topic. The goal is to gain insights through group conversation and observation of dynamics.

In a focus group:

- A moderator asks questions and leads a group of typically 6 to 12 pre-screened participants through a discussion focused on a particular topic.

- Group members are encouraged to talk with one another, exchange anecdotes, comment on each others’ experiences and points of view, and build on each others’ responses.

- The goal is to create a candid, natural conversation that provides insights into the participants’ perceptions, attitudes, beliefs, and opinions on the topic.

- Focus groups capitalize on group dynamics to elicit multiple perspectives in a social environment as participants are influenced by and influence others through open discussion.

- The interactive responses allow researchers to quickly gather more contextual, nuanced qualitative data compared to surveys or one-on-one interviews.

Focus groups allow researchers to gather perspectives from multiple people at once in an interactive group setting. This group dynamic surfaces richer responses as participants build on each other’s comments, discuss issues in-depth, and voice agreements or disagreements.

It is important that participants feel comfortable expressing diverse viewpoints rather than being pressured into a consensus.

Focus groups emerged as an alternative to questionnaires in the 1930s over concerns that surveys fostered passive responses or failed to capture people’s authentic perspectives.

During World War II, focus groups were used to evaluate military morale-boosting radio programs. By the 1950s focus groups became widely adopted in marketing research to test consumer preferences.

A key benefit K. Merton highlighted in 1956 was grouping participants with shared knowledge of a topic. This common grounding enables people to provide context to their experiences and allows contrasts between viewpoints to emerge across the group.

As a result, focus groups can elicit a wider range of perspectives than one-on-one interviews.

Step 1 : Clarify the Focus Group’s Purpose and Orientation

Clarify the purpose and orientation of the focus group (Tracy, 2013). Carefully consider whether a focus group or individual interviews will provide the type of qualitative data needed to address your research questions.

Determine if the interactive, fast-paced group discussion format is aligned with gathering perspectives vs. in-depth attitudes on a topic.

Consider incorporating special techniques like extended focus groups with pre-surveys, touchstones using creative imagery/metaphors to focus the topic, or bracketing through ongoing conceptual inspection.

For example

A touchstone in a focus group refers to using a shared experience, activity, metaphor, or other creative technique to provide a common reference point and orientation for grounding the discussion.

The purpose of Mulvale et al. (2021) was to understand the hospital experiences of youth after suicide attempts.

The researchers created a touchstone to focus the discussion specifically around the hospital visit. This provided a shared orientation for the vulnerable participants to open up about their emotional journeys.

In the example from Mulvale et al. (2021), the researchers designated the hospital visit following suicide attempts as the touchstone. This means:

- The visit served as a defining shared experience all youth participants could draw upon to guide the focus group discussion, since they unfortunately had this in common.

- Framing questions around recounting and making meaning out of the hospitalization focused the conversation to elicit rich details about interactions, emotions, challenges, supports needed, and more in relation to this watershed event.

- The hospital visit as a touchstone likely resonated profoundly across youth given the intensity and vulnerability surrounding their suicide attempts. This deepened their willingness to open up and established group rapport.

So in this case, the touchstone concentrated the dialogue around a common catalyst experience enabling youth to build understanding, voice difficulties, and potentially find healing through sharing their journey with empathetic peers who had endured the same trauma.

Step 2 : Select a Homogeneous Grouping Characteristic

Select a homogeneous grouping characteristic (Krueger & Casey, 2009) to recruit participants with a commonality, like shared roles, experiences, or demographics, to enable meaningful discussion.

A sample size of between 6 to 10 participants allows for adequate mingling (MacIntosh 1993).

More members may diminish the ability to capture all viewpoints. Fewer risks limited diversity of thought.

Balance recruitment across income, gender, age, and cultural factors to increase heterogeneity in perspectives. Consider screening criteria to qualify relevant participants.

Choosing focus group participants requires balancing homogeneity and diversity – too much variation across gender, class, profession, etc., can inhibit sharing, while over-similarity limits perspectives. Groups should feel mutual comfort and relevance of experience to enable open contributions while still representing a mix of viewpoints on the topic (Morgan 1988).

Mulvale et al. (2021) determined grouping by gender rather than age or ethnicity was more impactful for suicide attempt experiences.

They fostered difficult discussions by bringing together male and female youth separately based on the sensitive nature of topics like societal expectations around distress.

Step 3 : Designate a Moderator

Designate a skilled, neutral moderator (Crowe, 2003; Morgan, 1997) to steer productive dialogue given their expertise in guiding group interactions. Consider cultural insider moderators positioned to foster participant sharing by understanding community norms.

Define moderator responsibilities like directing discussion flow, monitoring air time across members, and capturing observational notes on behaviors/dynamics.

Choose whether the moderator also analyzes data or only facilitates the group.

Mulvale et al. (2021) designated a moderator experienced working with marginalized youth to encourage sharing by establishing an empathetic, non-judgmental environment through trust-building and active listening guidance.

Step 4 : Develop a Focus Group Guide

Develop an extensive focus group guide (Krueger & Casey, 2009). Include an introduction to set a relaxed tone, explain the study rationale, review confidentiality protection procedures, and facilitate a participant introduction activity.

Also include guidelines reiterating respect, listening, and sharing principles both verbally and in writing.

Group confidentiality agreement

The group context introduces distinct ethical demands around informed consent, participant expectations, confidentiality, and data treatment. Establishing guidelines at the outset helps address relevant issues.

Create a group confidentiality agreement (Berg, 2004) specifying that all comments made during the session must remain private, anonymous in data analysis, and not discussed outside the group without permission.

Have it signed, demonstrating a communal commitment to sustaining a safe, secure environment for honest sharing.

Berg (2004) recommends a formal signed agreement prohibiting participants from publicly talking about anything said in the focus group without permission. This reassures members their personal disclosures are safeguarded.

Develop questions starting general then funneling down to 10-12 key questions on critical topics. Integrate think/pair/share activities between question sets to encourage inclusion. Close with a conclusion to summarize key ideas voiced without endorsing consensus.

Krueger and Casey (2009) recommend structuring focus group questions in five stages:

Opening Questions:

- Start with easy, non-threatening questions to make participants comfortable, often related to their background and experience with the topic.

- Get everyone talking and open up initial dialogue.

- Example: “Let’s go around and have each person share how long you’ve lived in this city.”

Introductory Questions:

- Transition to the key focus group objectives and main topics of interest.

- Remain quite general to provide baseline understanding before drilling down.

- Example: “Thinking broadly, how would you describe the arts and cultural offerings in your community?”

Transition Questions:

- Serve as a logical link between introductory and key questions.

- Funnel participants toward critical topics guided by research aims.

- Example: “Specifically related to concerts and theatre performances, what venues in town have you attended events at over the past year?”

Key Questions:

- Drive at the heart of study goals, and issues under investigation.

- Ask 5-10 questions that foster organic, interactive discussion between participants.

- Example: “What enhances or detracts from the concert-going experience at these various venues?”

Ending Questions:

- Provide an opportunity for final thoughts or anything missed.

- Assess the degree of consensus on key topics.

- Example: “If you could improve just one thing about the concert and theatre options here, what would you prioritize?”

It is vital to extensively pilot test draft questions to hone the wording, flow, timing, tone and tackle any gaps to adequately cover research objectives through dynamic group discussion.

Step 5 : Prepare the focus group room

Prepare the focus group room (Krueger & Casey, 2009) attending to details like circular seating for eye contact, centralized recording equipment with backup power, name cards, and refreshments to create a welcoming, affirming environment critical for participants to feel valued, comfortable engaging in genuine dialogue as a collective.

Arrange seating comfortably in a circle to facilitate discussion flow and eye contact among members. Decide if space for breakout conversations or activities like role-playing is needed.

Refreshments

- Coordinate snacks or light refreshments to be available when focus group members arrive, especially for longer sessions. This contributes to a welcoming atmosphere.

- Even if no snacks are provided, consider making bottled water available throughout the session.

- Set out colorful pens and blank name tags for focus group members to write their preferred name or pseudonym when they arrive.

- Attaching name tags to clothing facilitates interaction and expedites learning names.

- If short on preparation time, prepare printed name tags in advance based on RSVPs, but blank name tags enable anonymity if preferred.

Krueger & Casey (2009) suggest welcoming focus group members with comfortable, inclusive seating arrangements in a circle to enable eye contact. Providing snacks and music sets a relaxed tone.

Step 6 : Conduct the focus group

Conduct the focus group utilizing moderation skills like conveying empathy, observing verbal and non-verbal cues, gently redirecting and probing overlooked members, and affirming the usefulness of knowledge sharing.

Use facilitation principles (Krueger & Casey, 2009; Tracy 2013) like ensuring psychological safety, mutual respect, equitable airtime, and eliciting an array of perspectives to expand group knowledge. Gain member buy-in through collaborative review.

Record discussions through detailed note-taking, audio/video recording, and seating charts tracking engaged participation.

The role of moderator

The moderator is critical in facilitating open, interactive discussion in the group. Their main responsibilities are:

- Providing clear explanations of the purpose and helping participants feel comfortable

- Promoting debate by asking open-ended questions

- Drawing out differences of opinion and a range of perspectives by challenging participants

- Probing for more details when needed or moving the conversation forward

- Keeping the discussion focused and on track

- Ensuring all participants get a chance to speak

- Remaining neutral and non-judgmental, without sharing personal opinions

Moderators need strong interpersonal abilities to build participant trust and comfort sharing. The degree of control and input from the moderator depends on the research goals and personal style.

With multiple moderators, roles, and responsibilities should be clear and consistent across groups. Careful preparation is key for effective moderation.

Mulvale et al. (2021) fostered psychological safety for youth to share intense emotions about suicide attempts without judgment. The moderator ensured equitable speaking opportunities within a compassionate climate.

Krueger & Casey (2009) advise moderators to handle displays of distress empathetically by offering a break and emotional support through active listening instead of ignoring reactions. This upholds ethical principles.

Advantages and disadvantages of focus groups

Focus groups efficiently provide interactive qualitative data that can yield useful insights into emerging themes. However, findings may be skewed by group behaviors and still require larger sample validation through added research methods. Careful planning is vital.

- Efficient way to gather a range of perspectives in participants’ own words in a short time

- Group dynamic encourages more complex responses as members build on others’ comments

- Can observe meaningful group interactions, consensus, or disagreements

- Flexibility for moderators to probe unanticipated insights during discussion

- Often feels more comfortable sharing as part of a group rather than one-on-one

- Helps participants recall and reflect by listening to others tell their stories

Disadvantages

- Small sample size makes findings difficult to generalize

- Groupthink: influential members may discourage dissenting views from being shared

- Social desirability bias: reluctance from participants to oppose perceived majority opinions

- Requires highly skilled moderators to foster inclusive participation and contain domineering members

- Confidentiality harder to ensure than with individual interviews

- Transcriptions may have overlapping talk that is difficult to capture accurately

- Group dynamics adds layers of complexity for analysis beyond just the content of responses

Goss, J. D., & Leinbach, T. R. (1996). Focus groups as alternative research practice: experience with transmigrants in Indonesia. Area , 115-123.

Kitzinger, J. (1994). The methodology of focus groups: the importance of interaction between research participants . Sociology of health & illness , 16 (1), 103-121.

Kitzinger J. (1995). Introducing focus groups. British Medical Journal, 311 , 299-302.

Morgan D.L. (1988). Focus groups as qualitative research . London: Sage.

Mulvale, G., Green, J., Miatello, A., Cassidy, A. E., & Martens, T. (2021). Finding harmony within dissonance: engaging patients, family/caregivers and service providers in research to fundamentally restructure relationships through integrative dynamics . Health Expectations , 24 , 147-160.

Powell, R. A., Single, H. M., & Lloyd, K. R. (1996). Focus groups in mental health research: enhancing the validity of user and provider questionnaires . International Journal of Social Psychiatry , 42 (3), 193-206.

Puchta, C., & Potter, J. (2004). Focus group practice . Sage.

Redmond, R. A., & Curtis, E. A. (2009). Focus groups: principles and process. Nurse researcher , 16 (3).

Smith, J. A., Scammon, D. L., & Beck, S. L. (1995). Using patient focus groups for new patient services. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement , 21 (1), 22-31.

Smithson, J. (2008). Focus groups. The Sage handbook of social research methods , 357-370.

White, G. E., & Thomson, A. N. (1995). Anonymized focus groups as a research tool for health professionals. Qualitative Health Research , 5 (2), 256-261.

Download PDF slides of the presentation ‘ Conducting Focus Groups – A Brief Overview ‘

Chapter 12. Focus Groups

Introduction.

Focus groups are a particular and special form of interviewing in which the interview asks focused questions of a group of persons, optimally between five and eight. This group can be close friends, family members, or complete strangers. They can have a lot in common or nothing in common. Unlike one-on-one interviews, which can probe deeply, focus group questions are narrowly tailored (“focused”) to a particular topic and issue and, with notable exceptions, operate at the shallow end of inquiry. For example, market researchers use focus groups to find out why groups of people choose one brand of product over another. Because focus groups are often used for commercial purposes, they sometimes have a bit of a stigma among researchers. This is unfortunate, as the focus group is a helpful addition to the qualitative researcher’s toolkit. Focus groups explicitly use group interaction to assist in the data collection. They are particularly useful as supplements to one-on-one interviews or in data triangulation. They are sometimes used to initiate areas of inquiry for later data collection methods. This chapter describes the main forms of focus groups, lays out some key differences among those forms, and provides guidance on how to manage focus group interviews.

Focus Groups: What Are They and When to Use Them

As interviews, focus groups can be helpfully distinguished from one-on-one interviews. The purpose of conducting a focus group is not to expand the number of people one interviews: the focus group is a different entity entirely. The focus is on the group and its interactions and evaluations rather than on the individuals in that group. If you want to know how individuals understand their lives and their individual experiences, it is best to ask them individually. If you want to find out how a group forms a collective opinion about something (whether a product or an event or an experience), then conducting a focus group is preferable. The power of focus groups resides in their being both focused and oriented to the group . They are best used when you are interested in the shared meanings of a group or how people discuss a topic publicly or when you want to observe the social formation of evaluations. The interaction of the group members is an asset in this method of data collection. If your questions would not benefit from group interaction, this is a good indicator that you should probably use individual interviews (chapter 11). Avoid using focus groups when you are interested in personal information or strive to uncover deeply buried beliefs or personal narratives. In general, you want to avoid using focus groups when the subject matter is polarizing, as people are less likely to be honest in a group setting. There are a few exceptions, such as when you are conducting focus groups with people who are not strangers and/or you are attempting to probe deeply into group beliefs and evaluations. But caution is warranted in these cases. [1]

As with interviewing in general, there are many forms of focus groups. Focus groups are widely used by nonresearchers, so it is important to distinguish these uses from the research focus group. Businesses routinely employ marketing focus groups to test out products or campaigns. Jury consultants employ “mock” jury focus groups, testing out legal case strategies in advance of actual trials. Organizations of various kinds use focus group interviews for program evaluation (e.g., to gauge the effectiveness of a diversity training workshop). The research focus group has many similarities with all these uses but is specifically tailored to a research (rather than applied) interest. The line between application and research use can be blurry, however. To take the case of evaluating the effectiveness of a diversity training workshop, the same interviewer may be conducting focus group interviews both to provide specific actionable feedback for the workshop leaders (this is the application aspect) and to learn more about how people respond to diversity training (an interesting research question with theoretically generalizable results).

When forming a focus group, there are two different strategies for inclusion. Diversity focus groups include people with diverse perspectives and experiences. This helps the researcher identify commonalities across this diversity and/or note interactions across differences. What kind of diversity to capture depends on the research question, but care should be taken to ensure that those participating are not set up for attack from other participants. This is why many warn against diversity focus groups, especially around politically sensitive topics. The other strategy is to build a convergence focus group , which includes people with similar perspectives and experiences. These are particularly helpful for identifying shared patterns and group consensus. The important thing is to closely consider who will be invited to participate and what the composition of the group will be in advance. Some review of sampling techniques (see chapter 5) may be helpful here.

Moderating a focus group can be a challenge (more on this below). For this reason, confining your group to no more than eight participants is recommended. You probably want at least four persons to capture group interaction. Fewer than four participants can also make it more difficult for participants to remain (relatively) anonymous—there is less of a group in which to hide. There are exceptions to these recommendations. You might want to conduct a focus group with a naturally occurring group, as in the case of a family of three, a social club of ten, or a program of fifteen. When the persons know one another, the problems of too few for anonymity don’t apply, and although ten to fifteen can be unwieldy to manage, there are strategies to make this possible. If you really are interested in this group’s dynamic (not just a set of random strangers’ dynamic), then you will want to include all its members or as many as are willing and able to participate.

There are many benefits to conducting focus groups, the first of which is their interactivity. Participants can make comparisons, can elaborate on what has been voiced by another, and can even check one another, leading to real-time reevaluations. This last benefit is one reason they are sometimes employed specifically for consciousness raising or building group cohesion. This form of data collection has an activist application when done carefully and appropriately. It can be fun, especially for the participants. Additionally, what does not come up in a focus group, especially when expected by the researcher, can be very illuminating.

Many of these benefits do incur costs, however. The multiplicity of voices in a good focus group interview can be overwhelming both to moderate and later to transcribe. Because of the focused nature, deep probing is not possible (or desirable). You might only get superficial thinking or what people are willing to put out there publicly. If that is what you are interested in, good. If you want deeper insight, you probably will not get that here. Relatedly, extreme views are often suppressed, and marginal viewpoints are unspoken or, if spoken, derided. You will get the majority group consensus and very little of minority viewpoints. Because people will be engaged with one another, there is the possibility of cut-off sentences, making it even more likely to hear broad brush themes and not detailed specifics. There really is very little opportunity for specific follow-up questions to individuals. Reading over a transcript, you may be frustrated by avenues of inquiry that were foreclosed early.

Some people expect that conducting focus groups is an efficient form of data collection. After all, you get to hear from eight people instead of just one in the same amount of time! But this is a serious misunderstanding. What you hear in a focus group is one single group interview or discussion. It is not the same thing at all as conducting eight single one-hour interviews. Each focus group counts as “one.” Most likely, you will need to conduct several focus groups, and you can design these as comparisons to one another. For example, the American Sociological Association (ASA) Task Force on First-Generation and Working-Class Persons in Sociology began its study of the impact of class in sociology by conducting five separate focus groups with different groups of sociologists: graduate students, faculty (in general), community college faculty, faculty of color, and a racially diverse group of students and faculty. Even though the total number of participants was close to forty, the “number” of cases was five. It is highly recommended that when employing focus groups, you plan on composing more than one and at least three. This allows you to take note of and potentially discount findings from a group with idiosyncratic dynamics, such as where a particularly dominant personality silences all other voices. In other words, putting all your eggs into a single focus group basket is not a good idea.

How to Conduct a Focus Group Interview/Discussion

Advance preparations.

Once you have selected your focus groups and set a date and time, there are a few things you will want to plan out before meeting.

As with interviews, you begin by creating an interview (or discussion) guide. Where a good one-on-one interview guide should include ten to twelve main topics with possible prompts and follow-ups (see the example provided in chapter 11), the focus group guide should be more narrowly tailored to a single focus or topic area. For example, a focus might be “How students coped with online learning during the pandemic,” and a series of possible questions would be drafted that would help prod participants to think about and discuss this topic. These questions or discussion prompts can be creative and may include stimulus materials (watching a video or hearing a story) or posing hypotheticals. For example, Cech ( 2021 ) has a great hypothetical, asking what a fictional character should do: keep his boring job in computers or follow his passion and open a restaurant. You can ask a focus group this question and see what results—how the group comes to define a “good job,” what questions they ask about the hypothetical (How boring is his job really? Does he hate getting up in the morning, or is it more of an everyday tedium? What kind of financial support will he have if he quits? Does he even know how to run a restaurant?), and how they reach a consensus or create clear patterns of disagreement are all interesting findings that can be generated through this technique.

As with the above example (“What should Joe do?”), it is best to keep the questions you ask simple and easily understood by everyone. Thinking about the sequence of the questions/prompts is important, just as it is in conducting any interviews.

Avoid embarrassing questions. Always leave an out for the “I have a friend who X” response rather than pushing people to divulge personal information. Asking “How do you think students coped?” is better than “How did you cope?” Chances are, some participants will begin talking about themselves without you directly asking them to do so, but allowing impersonal responses here is good. The group itself will determine how deep and how personal it wants to go. This is not the time or place to push anyone out of their comfort zone!

Of course, people have different levels of comfort talking publicly about certain topics. You will have provided detailed information to your focus group participants beforehand and secured consent. But even so, the conversation may take a turn that makes someone uncomfortable. Be on the lookout for this, and remind everyone of their ability to opt out—to stay silent or to leave if necessary. Rather than call attention to anyone in this way, you also want to let everyone know they are free to walk around—to get up and get coffee (more on this below) or use the restroom or just step out of the room to take a call. Of course, you don’t really want anyone to do any of these things, and chances are everyone will stay seated during the hour, but you should leave this “out” for those who need it.

Have copies of consent forms and any supplemental questionnaire (e.g., demographic information) you are using prepared in advance. Ask a friend or colleague to assist you on the day of the focus group. They can be responsible for making sure the recording equipment is functioning and may even take some notes on body language while you are moderating the discussion. Order food (coffee or snacks) for the group. This is important! Having refreshments will be appreciated by your participants and really damps down the anxiety level. Bring name tags and pens. Find a quiet welcoming space to convene. Often this is a classroom where you move chairs into a circle, but public libraries often have meeting rooms that are ideal places for community members to meet. Be sure that the space allows for food.

Researcher Note

When I was designing my research plan for studying activist groups, I consulted one of the best qualitative researchers I knew, my late friend Raphael Ezekiel, author of The Racist Mind . He looked at my plan to hand people demographic surveys at the end of the meetings I planned to observe and said, “This methodology is missing one crucial thing.” “What?” I asked breathlessly, anticipating some technical insider tip. “Chocolate!” he answered. “They’ll be tired, ready to leave when you ask them to fill something out. Offer an incentive, and they will stick around.” It worked! As the meetings began to wind down, I would whip some bags of chocolate candies out of my bag. Everyone would stare, and I’d say they were my thank-you gift to anyone who filled out my survey. Once I learned to include some sugar-free candies for diabetics, my typical response rate was 100 percent. (And it gave me an additional class-culture data point by noticing who chose which brand; sure enough, Lindt balls went faster at majority professional-middle-class groups, and Hershey’s minibars went faster at majority working-class groups.)

—Betsy Leondar-Wright, author of Missing Class , coauthor of The Color of Wealth , associate professor of sociology at Lasell University, and coordinator of staffing at the Mission Project for Class Action

During the Focus Group

As people arrive, greet them warmly, and make sure you get a signed consent form (if not in advance). If you are using name tags, ask them to fill one out and wear it. Let them get food and find a seat and do a little chatting, as they might wish. Once seated, many focus group moderators begin with a relevant icebreaker. This could be simple introductions that have some meaning or connection to the focus. In the case of the ASA task force focus groups discussed above, we asked people to introduce themselves and where they were working/studying (“Hi, I’m Allison, and I am a professor at Oregon State University”). You will also want to introduce yourself and the study in simple terms. They’ve already read the consent form, but you would be surprised at how many people ignore the details there or don’t remember them. Briefly talking about the study and then letting people ask any follow-up questions lays a good foundation for a successful discussion, as it reminds everyone what the point of the event is.

Focus groups should convene for between forty-five and ninety minutes. Of course, you must tell the participants the time you have chosen in advance, and you must promptly end at the time allotted. Do not make anyone nervous by extending the time. Let them know at the outset that you will adhere to this timeline. This should reduce the nervous checking of phones and watches and wall clocks as the end time draws near.

Set ground rules and expectations for the group discussion. My preference is to begin with a general question and let whoever wants to answer it do so, but other moderators expect each person to answer most questions. Explain how much cross-talk you will permit (or encourage). Again, my preference is to allow the group to pick up the ball and run with it, so I will sometimes keep my head purposefully down so that they engage with one another rather than me, but I have seen other moderators take a much more engaged position. Just be clear at the outset about what your expectations are. You may or may not want to explain how the group should deal with those who would dominate the conversation. Sometimes, simply stating at the outset that all voices should be heard is enough to create a more egalitarian discourse. Other times, you will have to actively step in to manage (moderate) the exchange to allow more voices to be heard. Finally, let people know they are free to get up to get more coffee or leave the room as they need (if you are OK with this). You may ask people to refrain from using their phones during the duration of the discussion. That is up to you too.

Either before or after the introductions (your call), begin recording the discussion with their collective permission and knowledge . If you have brought a friend or colleague to assist you (as you should), have them attend to the recording. Explain the role of your colleague to the group (e.g., they will monitor the recording and will take short notes throughout to help you when you read the transcript later; they will be a silent observer).

Once the focus group gets going, it may be difficult to keep up. You will need to make a lot of quick decisions during the discussion about whether to intervene or let it go unguided. Only you really care about the research question or topic, so only you will really know when the discussion is truly off topic. However you handle this, keep your “participation” to a minimum. According to Lune and Berg ( 2018:95 ), the moderator’s voice should show up in the transcript no more than 10 percent of the time. By the way, you should also ask your research assistant to take special note of the “intensity” of the conversation, as this may be lost in a transcript. If there are people looking overly excited or tapping their feet with impatience or nodding their heads in unison, you want some record of this for future analysis.

I’m not sure why this stuck with me, but I thought it would be interesting to share. When I was reviewing my plan for conducting focus groups with one of my committee members, he suggested that I give the participants their gift cards first. The incentive for participating in the study was a gift card of their choice, and typical processes dictate that participants must complete the study in order to receive their gift card. However, my committee member (who is Native himself) suggested I give it at the beginning. As a qualitative researcher, you build trust with the people you engage with. You are asking them to share their stories with you, their intimate moments, their vulnerabilities, their time. Not to mention that Native people are familiar with being academia’s subjects of interest with little to no benefit to be returned to them. To show my appreciation, one of the things I could do was to give their gifts at the beginning, regardless of whether or not they completed participating.

—Susanna Y. Park, PhD, mixed-methods researcher in public health and author of “How Native Women Seek Support as Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence: A Mixed-Methods Study”

After the Focus Group

Your “data” will be either fieldnotes taken during the focus group or, more desirably, transcripts of the recorded exchange. If you do not have permission to record the focus group discussion, make sure you take very clear notes during the exchange and then spend a few hours afterward filling them in as much as possible, creating a rich memo to yourself about what you saw and heard and experienced, including any notes about body language and interactions. Ideally, however, you will have recorded the discussion. It is still a good idea to spend some time immediately after the conclusion of the discussion to write a memo to yourself with all the things that may not make it into the written record (e.g., body language and interactions). This is also a good time to journal about or create a memo with your initial researcher reactions to what you saw, noting anything of particular interest that you want to come back to later on (e.g., “It was interesting that no one thought Joe should quit his job, but in the other focus group, half of the group did. I wonder if this has something to do with the fact that all the participants were first-generation college students. I should pay attention to class background here.”).

Please thank each of your participants in a follow-up email or text. Let them know you appreciated their time and invite follow-up questions or comments.

One of the difficult things about focus group transcripts is keeping speakers distinct. Eventually, you are going to be using pseudonyms for any publication, but for now, you probably want to know who said what. You can assign speaker numbers (“Speaker 1,” “Speaker 2”) and connect those identifications with particular demographic information in a separate document. Remember to clearly separate actual identifications (as with consent forms) to prevent breaches of anonymity. If you cannot identify a speaker when transcribing, you can write, “Unidentified Speaker.” Once you have your transcript(s) and memos and fieldnotes, you can begin analyzing the data (chapters 18 and 19).

Advanced: Focus Groups on Sensitive Topics

Throughout this chapter, I have recommended against raising sensitive topics in focus group discussions. As an introvert myself, I find the idea of discussing personal topics in a group disturbing, and I tend to avoid conducting these kinds of focus groups. And yet I have actually participated in focus groups that do discuss personal information and consequently have been of great value to me as a participant (and researcher) because of this. There are even some researchers who believe this is the best use of focus groups ( de Oliveira 2011 ). For example, Jordan et al. ( 2007 ) argue that focus groups should be considered most useful for illuminating locally sanctioned ways of talking about sensitive issues. So although I do not recommend the beginning qualitative researcher dive into deep waters before they can swim, this section will provide some guidelines for conducting focus groups on sensitive topics. To my mind, these are a minimum set of guidelines to follow when dealing with sensitive topics.

First, be transparent about the place of sensitive topics in your focus group. If the whole point of your focus group is to discuss something sensitive, such as how women gain support after traumatic sexual assault events, make this abundantly clear in your consent form and recruiting materials. It is never appropriate to blindside participants with sensitive or threatening topics .

Second, create a confidentiality form (figure 12.2) for each participant to sign. These forms carry no legal weight, but they do create an expectation of confidentiality for group members.

In order to respect the privacy of all participants in [insert name of study here], all parties are asked to read and sign the statement below. If you have any reason not to sign, please discuss this with [insert your name], the researcher of this study, I, ________________________, agree to maintain the confidentiality of the information discussed by all participants and researchers during the focus group discussion.

Signature: _____________________________ Date: _____________________

Researcher’s Signature:___________________ Date:______________________

Figure 12.2 Confidentiality Agreement of Focus Group Participants

Third, provide abundant space for opting out of the discussion. Participants are, of course, always permitted to refrain from answering a question or to ask for the recording to be stopped. It is important that focus group members know they have these rights during the group discussion as well. And if you see a person who is looking uncomfortable or like they want to hide, you need to step in affirmatively and remind everyone of these rights.

Finally, if things go “off the rails,” permit yourself the ability to end the focus group. Debrief with each member as necessary.

Further Readings

Barbour, Rosaline. 2018. Doing Focus Groups . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Written by a medical sociologist based in the UK, this is a good how-to guide for conducting focus groups.

Gibson, Faith. 2007. “Conducting Focus Groups with Children and Young People: Strategies for Success.” Journal of Research in Nursing 12(5):473–483. As the title suggests, this article discusses both methodological and practical concerns when conducting focus groups with children and young people and offers some tips and strategies for doing so effectively.

Hopkins, Peter E. 2007. “Thinking Critically and Creatively about Focus Groups.” Area 39(4):528–535. Written from the perspective of critical/human geography, Hopkins draws on examples from his own work conducting focus groups with Muslim men. Useful for thinking about positionality.

Jordan, Joanne, Una Lynch, Marianne Moutray, Marie-Therese O’Hagan, Jean Orr, Sandra Peake, and John Power. 2007. “Using Focus Groups to Research Sensitive Issues: Insights from Group Interviews on Nursing in the Northern Ireland ‘Troubles.’” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 6(4), 1–19. A great example of using focus groups productively around emotional or sensitive topics. The authors suggest that focus groups should be considered most useful for illuminating locally sanctioned ways of talking about sensitive issues.

Merton, Robert K., Marjorie Fiske, and Patricia L. Kendall. 1956. The Focused Interview: A Manual of Problems and Procedures . New York: Free Press. This is one of the first classic texts on conducting interviews, including an entire chapter devoted to the “group interview” (chapter 6).

Morgan, David L. 1986. “Focus Groups.” Annual Review of Sociology 22:129–152. An excellent sociological review of the use of focus groups, comparing and contrasting to both surveys and interviews, with some suggestions for improving their use and developing greater rigor when utilizing them.

de Oliveira, Dorca Lucia. 2011. “The Use of Focus Groups to Investigate Sensitive Topics: An Example Taken from Research on Adolescent Girls’ Perceptions about Sexual Risks.” Cien Saude Colet 16(7):3093–3102. Another example of discussing sensitive topics in focus groups. Here, the author explores using focus groups with teenage girls to discuss AIDS, risk, and sexuality as a matter of public health interest.

Peek, Lori, and Alice Fothergill. 2009. “Using Focus Groups: Lessons from Studying Daycare Centers, 9/11, and Hurricane Katrina.” Qualitative Research 9(1):31–59. An examination of the efficacy and value of focus groups by comparing three separate projects: a study of teachers, parents, and children at two urban daycare centers; a study of the responses of second-generation Muslim Americans to the events of September 11; and a collaborative project on the experiences of children and youth following Hurricane Katrina. Throughout, the authors stress the strength of focus groups with marginalized, stigmatized, or vulnerable individuals.

Wilson, Valerie. 1997. “Focus Groups: A Useful Qualitative Method for Educational Research?” British Educational Research Journal 23(2):209–224. A basic description of how focus groups work using an example from a study intended to inform initiatives in health education and promotion in Scotland.

- Note that I have included a few examples of conducting focus groups with sensitive issues in the “ Further Readings ” section and have included an “ Advanced: Focus Groups on Sensitive Topics ” section on this area. ↵

A focus group interview is an interview with a small group of people on a specific topic. “The power of focus groups resides in their being focused” (Patton 2002:388). These are sometimes framed as “discussions” rather than interviews, with a discussion “moderator.” Alternatively, the focus group is “a form of data collection whereby the researcher convenes a small group of people having similar attributes, experiences, or ‘focus’ and leads the group in a nondirective manner. The objective is to surface the perspectives of the people in the group with as minimal influence by the researcher as possible” (Yin 2016:336). See also diversity focus group and convergence focus group.

A form of focus group construction in which people with diverse perspectives and experiences are chosen for inclusion. This helps the researcher identify commonalities across this diversity and/or note interactions across differences. Contrast with a convergence focus group

A form of focus group construction in which people with similar perspectives and experiences are included. These are particularly helpful for identifying shared patterns and group consensus. Contrast with a diversity focus group .