- Shop Our Books

- Curricular Resources

- Free Teaching Resources

- Heinemann Blog & Podcasts

- Professional Learning

- Professional Book Events

- The Comprehension Toolkit

- Fountas & Pinnell Literacy ™

- Jennifer Serravallo's Resources

- Saxon Phonics and Spelling

- Units of Study

- Writing@Heinemann

- Explore Literacy Topics:

- – Reading

- – Social Emotional Learning

- – Whole Group Literacy

- – Small Group Literacy

- – Assessment and Intervention

- – Writing

- Professional Books

- – Browse by Author

- Math@Heinemann

- – Do The Math

- – Listening to Learn

- – Math by the Book

- – Math Expressions

- – Math in Practice

- – Matific

- – Transition to Algebra

- Explore Math Topics:

- – Inquiry Based Math

- – K-12 Math

- Fountas & Pinnell Literacy™

- – Results, Efficacy and Case Studies

- – Research

- – Research Data

- – Data Reports

- – Case Studies

- Create Account Log In

- Find My Sales Rep

A Novel Approach

Whole-class novels, student-centered teaching, and choice.

By Kate Roberts

.internal').css('display','block');$('#content_sectionFullDesc > .slider').find('span.rspv-up-arrow').toggleClass('rspv-down-arrow');" href="#fulldesc" >Read Full Description below »

List Price: $38.47

Web/School Price: $28.85

Please note that all discounts and final pricing will be displayed on the Review Order page before you submit your order.

COLLEGE PROFESSORS

Share this resource.

As an English teacher, Kate Roberts has seen the power of whole-class novels to build community in her classroom. But she’s also seen too many kids struggle too much to read them--and consequently, check out of reading altogether. Kate’s had better success getting kids to actually read – and enjoy it—when they choose their own books within a workshop model. “And yet,” she says, “I missed my whole-class novels.”

In A Novel Approach , Kate takes a deep dive into the troubles and triumphs of both whole-class novels and independent reading and arrives at a persuasive conclusion: we can find a student-centered, balanced approach to teaching reading. Kate offers a practical framework for creating units that join both teaching methods together and helps you:

• Identify the skills your students need to learn • Choose whole-class texts that will be most relevant to your kids • Map out the timing of a unit and the strategies you’ll teach • Meet individual needs while teaching whole novels • Guide students to choice books and book clubs that build on the skills being taught.

Above all, Kate’s plan emphasizes teaching reading skills and strategies over the books themselves. “By making sure that our classes are structured in a way that really sees students and strives to meet their needs,” she argues, “we can keep reaching for the dream of a class where no student is unmoved, no reader unchanged by the end of the year.” Video clips of Kate working with students in diverse classrooms bring the content to life throughout the book.

(click any section below to continue reading)

1. You Can Have It Both Ways: Reading Literature Deeply and Fostering Joyful, Independent Reading

2. Start with the Students: Identify the Skills Your Students Need

3. Look Beyond the Usual Suspects: Choose the Book Your Students Need

4. Map Out the Unit: Plan the Timing and the Strategies You'll Teach

5. Delight in the Details: Play Your Daily Instruction: Read-Alouds and Minilessons

6. Reach Everyone: Differentiate with Small Groups and Conferences

7. Keep Students Engaged: Address the Challenges of Teaching a Whole-Class Text

8. Track Growth: Assess Along the Way Through Writing About Reading

9. Launch Readers: Honor Choice to Develop Stronger, Independent Students

10. Celebrate Achievements: Assessing, Writing, and Making as an End to the Unit

Can’t we provide both individualized instruction and challenging reading for our students? This book shows how we can do just that. In a nutshell:

1. We plan a unit in our classroom, naming the skill or skills that will be our primary focus.

2. We choose a whole-class novel that will both interest the kids and do the heavy lifting for the skills we plan to teach.

3. We plan our lessons accordingly.

That’s it. Pretty simple. Of course, like many simple ideas in and out of education, the execution takes some doing. That’s what the rest of the book is for. We’ll begin with a deep dive into the troubles and triumphs of both whole-class novels and readers workshop and think about what we can aim for in our teaching (Chapter 1). Then, we’ll follow the trajectory of a unit: choosing the skills and book you’ll be using (Chapters 2 and 3), teaching with the whole-class novel (Chapters 4 and 5) and meeting individual needs while doing so (Chapters 6 and 7), assessing formatively (Chapter 8), helping students transfer the skills they’ve learned to book-club books (Chapter 9), and assessing summatively (Chapter 10).

— Introduction

- Sample Chapter

Companion Resources

“A Novel Approach dismantles timeworn methods for teaching whole class novels that consume class time, provide little relevance or rigor, and disengage students from reading. Kate Roberts offers an empowering road map for navigating whole class novels with your students while supporting their independent reading lives. A forward-thinking model for progressive literacy education.”—Donalyn Miller, author of The Book Whisperer and Reading in the Wild

“I wish this book was around back when I completely stopped reading in High School. I lost years of my reading life, just as so many students turn away from reading in secondary grades because the assigned books are uninteresting, too confusing, or seem to drag on. Kate's approach shows us that when novel teaching is skills driven, brief, and complimented with book clubs, it can be more engaging to students and more rewarding for teachers.”—Christopher Lehman, coauthor of Falling in Love with Close Reading and author of Energize Research Writing

“Increasing the volume of student reading starts with finding the right balance between independent reading, book club reading, and core work reading. And this is where A Novel Approach proves invaluable. Kate Roberts not only shows secondary teachers why achieving this balance is important, she demonstrates how to do it.”—Kelly Gallagher, coauthor of 180 Days and author of Readicide

“There isn’t a teacher among us who hasn’t wondered, “How do I do all of this?” Reading this book is like having the world’s best instructional coach by your side to help you craft a clear, manageable, and responsive approach to helping your students become better readers, thinkers, and people. Kate reminds us of the tremendous power of our instructional decisions on our students’ reading lives, all the while, handing us resources, instilling in us a necessary confidence, and high-fiving us through pages of this book.” –Allison Marchetti and Rebekah O’Dell, coauthors of Beyond Literary Analysis and Writing With Mentors

“Like any author worth her salt, Kate trusts her readers to bring their own expertise to the text. If you are expecting the definitive answer to the age-old question, “What’s better: giving students opportunities for independent choice, or teaching with a whole class novel?” you won’t get the answer. What you will get is Kate’s straightforward, common sense approach on how to use both. Kate helps teachers weigh their options and make choices about what’s best for their students. She shares her systems and structures and reassures readers that students of all levels can make growth.”—Cris Tovani, coauthor of No More Telling as Teaching and I Read It, But I Don’t Get It

“In A Novel Approach, Kate Roberts offers those of us in the classroom a witty, engaging, and thoughtful examination of a problem we are all grappling with one way or another: How to teach whole-classs novels in ways that challenge and engage not only our students but us! This thoughtful book provides a range of approaches that would work in different classes with different kids. Just as important, though, it shows us that it is still possible to be the sort of English teacher we wanted to be when we entered the profession.”—Jim Burke, author of The English Teacher’s Companion

More resources from Kate Roberts

Customers who liked this also liked

- Open access

- Published: 04 September 2021

Journey mapping as a novel approach to healthcare: a qualitative mixed methods study in palliative care

- Stephanie Ly 1 ,

- Fiona Runacres 1 , 2 , 3 &

- Peter Poon 1 , 2

BMC Health Services Research volume 21 , Article number: 915 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

13k Accesses

22 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

Journey mapping involves the creation of visual narrative timelines depicting the multidimensional relationship between a consumer and a service. The use of journey maps in medical research is a novel and innovative approach to understanding patient healthcare encounters.

To determine possible applications of journey mapping in medical research and the clinical setting. Specialist palliative care services were selected as the model to evaluate this paradigm, as there are numerous evidence gaps and inconsistencies in the delivery of care that may be addressed using this tool.

A purposive convenience sample of specialist palliative care providers from the Supportive and Palliative Care unit of a major Australian tertiary health service were invited to evaluate journey maps illustrating the final year of life of inpatient palliative care patients. Sixteen maps were purposively selected from a sample of 104 consecutive patients. This study utilised a qualitative mixed-methods approach, incorporating a modified Delphi technique and thematic analysis in an online questionnaire.

Our thematic and Delphi analyses were congruent, with consensus findings consistent with emerging themes. Journey maps provided a holistic patient-centred perspective of care that characterised healthcare interactions within a longitudinal trajectory. Through these journey maps, participants were able to identify barriers to effective palliative care and opportunities to improve care delivery by observing patterns of patient function and healthcare encounters over multiple settings.

Conclusions

This unique qualitative study noted many promising applications of the journey mapping suitable for extrapolation outside of the palliative care setting as a review and audit tool, or a mechanism for providing proactive patient-centred care. This is particularly significant as machine learning and big data is increasingly applied to healthcare.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Patterns of healthcare utilisation are evolving in response to the ageing population and increasing burden of chronic disease. There is an urgent need to ensure timely proactive medical care, effective and efficient resource deployment, while averting unnecessary, often distressing, emergency department (ED) presentations, admissions and conveyor belt medicine. A key area of medicine able to address these issues is palliative care.

Central to optimal delivery of palliative care is timely initiation [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. However, differing patient, illness trajectory and clinical factors have resulted in inconsistencies in the degree of care provided [ 4 , 5 ]. This has subsequently translated into significant variability in palliative care research and limitations in applying international evidence to clinical practice [ 6 ]. The utilisation of journey mapping has the potential to address these inconsistencies and to our knowledge, this research is the first of its kind.

Journey mapping is a relatively new approach in medical research that has been adapted from customer service and marketing research [ 7 ]. It is gaining increasing recognition for its ability to organise complex multifaceted data from numerous sources and explore interactions across care settings and over time. Medical journey mapping involves creating narrative timelines, by incorporating markers of the patient experience with healthcare service encounters. Integrating diverse components of the patient healthcare journey provides a holistic perspective of the relationships between the different elements that may guide directions for change and service improvement. As medical journey mapping is still in its infancy, there is an absence of literature exploring implementation. Of the existing literature, journey mapping techniques are described mainly in process papers, outlining their potential utility in observing healthcare delivery and patient outcomes [ 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ]. However journey mapping paradigms have broader significance across healthcare, especially in an environment for which machine learning, big data and artificial intelligence is maturing.

We aimed to determine whether journey mapping could contribute to the improvement of patient-centred medical research in a palliative care setting and provide new insight into possible “pivot-points” or moments of care that could be altered to improve care delivery. Specifically, we sought to determine whether journey maps were able to assist in capturing a holistic, longitudinal and more integrative patient history whilst outlining healthcare provision and identifying gaps in care.

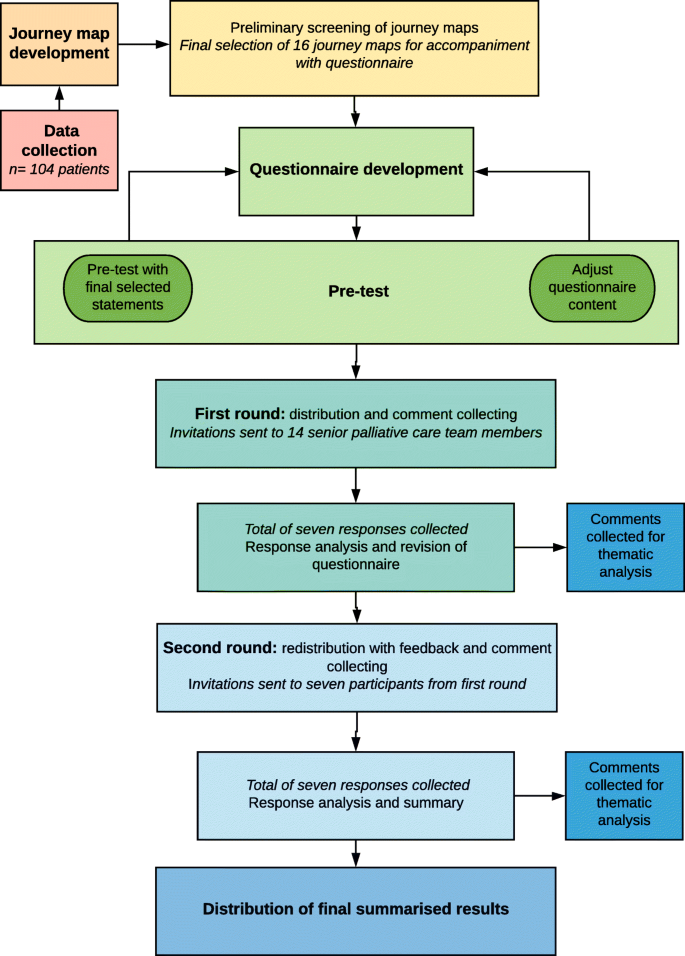

Study design

We performed a qualitative mixed-methods analysis of a journey mapping tool. The tool was purpose-developed and sample journey maps were derived from the scanned medical records of palliative care patients. A panel of specialist palliative care providers were then involved in an online questionnaire combining a modified Delphi approach with inductive thematic analysis. Figure 1 depicts a flow diagram of the methodology.

Flow chart detailing data collection, journey map development and analysis. This figure illustrates the phases and processes of this study. Data was collected from a retrospective cohort of 104 palliative care patients and journey maps were subsequently developed. Preliminary screening of the journey maps was performed to obtain a purposive sample that best highlighted the breadth of information and healthcare encounters captured within the journey maps. A total of 16 maps were selected for further analysis. Following questionnaire development and pre-test, questionnaires were distributed, and responses collected and analysed over two rounds to obtain consensus. Free-text comments from both rounds were collected for thematic analysis

All methods were carried out and reported in accordance with Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) guidelines and Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research (COREQ) criteria for reporting qualitative studies.

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from Monash Health Human Research Ethics Committee Monash Health Ref: RES-29-0000-071Q) and Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project ID: 18,853).

Data was collected from a retrospective cohort of 104 consecutive palliative care patients from a major tertiary hospital network in Melbourne, Australia. Inclusion criteria were patients greater than 18 years of age who had died in hospital between the 1st of August 2018 and 31st of October 2018, had at least one inpatient palliative care admission in their last year of life and scanned medical records data spanning at least three months’ duration. This sample size was considered sufficient to incorporate a varied and representative sample of palliative care patients encountered in the tertiary hospital.

Following data collection, a Python Software-based code was designed to extract de-identified data and create journey map visuals. All 104 journey maps were independently screened by two investigators (PP and FR) and a purposive sample of 16 maps was selected for analysis based on seven criteria for informative value. The criteria that the 104 maps were assessed on included their ability to provide insight into the initiation, triggers, delivery and barriers of palliative care, SPICT scores, pivot points and disease trajectories.

Modified Delphi approach and thematic analysis

A qualitative mixed-methods approach involving thematic analysis and a modified Delphi technique was utilised as an explorative analysis of expert opinion. The consensus agreement was used to reinforce and confirm the patterns of significance identified through thematic analysis. In combining these two approaches, there was greater flexibility in responses and additional structure to support analysis.

The modified Delphi approach used in this study was adapted from the enhanced Delphi method described by Yang et al. [ 13 ] and consisted of a questionnaire pre-test and two rounds of questionnaire distribution. A total of 14 email invitations were sent to a purposive sample of seven senior palliative care physicians and seven palliative care nurse consultants across two palliative care inpatient units within a major tertiary hospital network in Melbourne, Australia. The emails contained an explanatory statement, a questionnaire link and the file containing the 16 de-identified journey maps.

The questionnaires consisted of 16 statements per journey map, covering eight palliative care domains: palliative care triggers, initiation, delivery, outcomes, barriers, pivot-points, needs assessment (using the Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool, SPICT) and the utility of advanced care plans. An additional nine statements assessed the utility of the journey map approach (see Table 2 ). All statements were ranked using Likert scales. A four-point Likert scale including the options: insufficient information, disagree, neither agree nor disagree and agree was used to assess individual journey maps. A five-point Likert scale including options: strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat agree and strongly agree was used to assess the journey mapping approach. For analysis of consensus, the results were categorised to reflect overall agreement by using a three-point scale consisting of disagree, neutral and agree . Consensus was defined as agreement of greater than 70 % of respondents in any one of these three categories. Following the first round, all consensus statements were determined and participants were sent a second questionnaire containing anonymous feedback from the first round and statements which did not reach consensus for re-evaluation using the condensed three-point Likert scale.

Following each palliative care domain, free-text fields were included to collect comments and provide data for inductive thematic analysis. Analysis of the free-text comments from both rounds was guided by Braun and Clarke’s phases of thematic analysis [ 14 ]. The codes and themes were derived from the data using NVivo 12 Plus software to generate nodes, initial codes and preliminary subthemes. Candidate themes were reviewed by two additional investigators (PP and FR) to ensure consistency and the final themes were defined. Providing participants with the opportunity to review de-identified feedback through the Delphi questionnaire enabled discussion, reflection and clarification of comments, thus achieving thematic saturation with a smaller group of participants.

Additional steps were taken to increase trustworthiness of the qualitative data per Lincoln and Guba’s criteria for credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability across all phases of analysis [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Triangulation of the methods, researchers and analysts aimed to increase consistency and accuracy, whilst reducing interpretation errors and the effects of bias. Thorough audit trails and reflexive journaling were maintained. The use of the online questionnaire with free-text fields for thematic data collection limited the role of the researcher and the potential for associated bias.

While this study also produced findings relevant to current issues of palliative care delivery, we will for the purpose of this paper, present results specific to the clinical utility of journey maps.

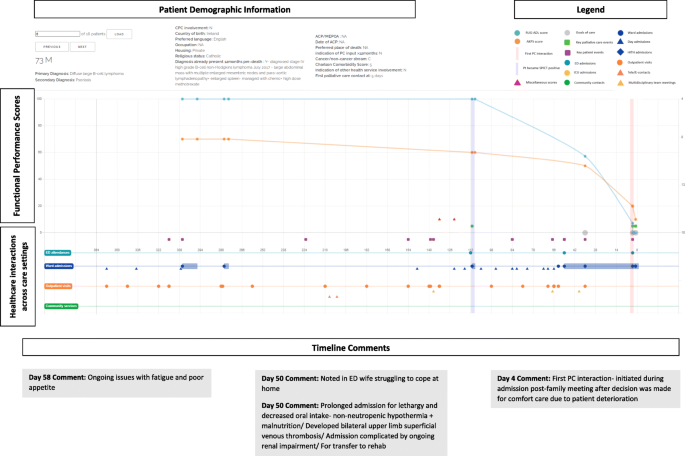

The journey maps

Figure 2 depicts one of the 16-sample journey maps analysed by participants and illustrates the key elements of a map. While journey maps are interactive visualisations with options for providing additional information summarising patient healthcare encounters, we are unable to fully convey the dynamic functions of the mapping tool in this paper. The journey map in Fig. 2 illustrates the final year of life of a 73 year old male patient with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Screen capture of Journey Map 6. A screen capture of one of the 16 interactive journey maps that was analysed by the Delphi panel. The lower segment of the map depicts healthcare interactions that occurred in hospital and in the community. Delphi participants are able to hover over specific health service touch points to obtain more information about the specific interaction that occurred. The upper segment represents functional performance scores using two different tools- the Australian Karnofsky Performance Scale (AKPS) and the Resource Utilisation Groups-Activities of Daily Living (RUG-ADL). The orange vertical line indicates when palliative care needs first presented using the SPICT screening tool. The vertical purple line indicates when specialist palliative care was initiated. Delphi participants were able to analyse the maps and respond to statements on the palliative care provided

The map reveals that at day 112 prior to death, palliative care needs were noted using the SPICT screening tool. It is also at this point that the patient’s functional performance scores began to decline, with patient notes from day admissions and clinic visits also documenting poor tolerance of chemotherapy side effects, fatigue, anorexia and weight loss. In response to this pattern of decline, participants noted that there was an opportunistic role for community palliative care support that was missed and could have potentially negated the need for the final ED admission.

“Onc (sic)(oncology) outpatient notes describing symptoms, deterioration, carer distress… Community pall care (sic)(palliative care) could have been helpful” – Participant 2, Journey Map (JM) 6.

Another major pivot-point occurred during the patient’s admission to ED on day 50 when notes indicated that the patient’s wife was struggling to cope with care at home. Given the nature of the prolonged admission with multiple complications that followed, Delphi participants questioned the suitability of the transfer to the rehabilitation ward.

“Symptoms and functional decline appear to be related to lymphoma and not an acute illness. More appropriate for pall care (sic) than rehab (sic)(rehabilitation).” – Participant 6, JM6.

Additionally, the decision to initiate palliative care only four days prior to death was delayed and there was a role for earlier palliative care involvement.

“Clearly PC (sic)(palliative care) involvement inadequate and was a later referral for terminal care only” – Participant 1, JM6.

“Pt (sic)(patient) would have benefitted from earlier palliative care referral” – Participant 7, JM6.

Through the maps, participants were able to observe patterns of deterioration with a broader view of continuity of care and determine pivot-points, where the involvement of specialist palliative care had the potential to improve the patient experience.

Modified Delphi

The two Delphi rounds were conducted over 31 days with the first round taking 13 days and the second round spanning 18 days. A total of seven responses were collected from the first round of the online Delphi questionnaire. Six members of the medical staff and one member of the nursing team responded, representing a 50 % response rate. All seven participants completed the questionnaire in full. For the second round, all first round participants were re-contacted and invited to participate. All seven participants from the first round agreed to participate, attributing to a 100 % second round response rate and 100 % questionnaire completion rate. Participant characteristics have been described in Table 1 . All participants are senior palliative care team members.

The statements assessing journey map utility are shown in Table 2 . As there was a strong overall consensus following the first round of the Delphi questionnaire, these statements were not rechallenged in a second round. However free-text fields were included to allow participants to provide any further comments.

Thematic analysis

Following analysis of all free-text comments, the following themes were derived regarding the applications of the journey mapping tool: (1) design and information, (2) longitudinal care and the patient trajectory and (3) opportunities for care improvement. These are discussed with supporting quotations listed in Table 3 .

Theme 1: tool design and information

A large determinant of the practicality of the tool relates to its design. Participants provided feedback regarding the design and informational elements of the journey mapping tool used in this study.

Aspects of the interface

Participants found that there were certain elements of the journey maps that limited functionality of the tool, however these were associated with the specific design of the tool interface, rather than the actual components underlying the journey mapping approach. Participants responded well to the concept of a visual representation of patient information and the timeline view of care that was constructed.

Catering information needs

Given the palliative care specific focus on patient care presented in these maps, participants found that at times there was an excess of unnecessary information and insufficient palliative care appropriate information. The absence of objective measures of quality of life also restricted the ability of participants to determine whether outcomes were improved as a result of interventions.

Theme 2: Longitudinal care and the patient trajectory

The benefits of conveying patient information and healthcare encounters in the form of journey maps were also recognised. Journey maps provided a patient-centred focus of care that characterises patient healthcare interactions within a longitudinal trajectory rather than individual care episodes as is standard in conventional medical records. In doing so, patterns of the disease trajectory and also patient decline can be mapped to provide more proactive patient care.

Theme 3: Opportunities for care improvement

The benefits of having the journey mapping tool and its utility if incorporated into patient care were also explored, with participants noting numerous possible applications and opportunities to improve patient care.

Identifying barriers and missed opportunities for care

By framing the patient healthcare experience as a longitudinal and continuous journey, participants were able to recognise missed opportunities to address barriers and initiate more timely palliative care.

Clinical applications

Participants also noted that journey maps were a useful tool for identifying gaps in care provision and underlying barriers to initiation and delivery. This could assist clinicians with recognition of pivot-points and opportunities to enhance care by pre-emptively managing issues. Additionally, journey maps presented possible applications as a review or screening tool to evaluate patient care needs and enable better patient-centred care practices both in the clinical and research setting.

Findings from both the modified Delphi and thematic analysis appeared congruent, with the consensus consistent with emerging themes.

Journey mapping is a novel approach to reviewing patient healthcare interactions over time and across care settings to identify potential pivot points, which in turn can facilitate timely healthcare and promote proactive delivery of patient-centred care. Our research has focused on palliative care as the model to explore this approach, especially given its importance in an ageing population and considering many aspects of care are ubiquitous to this cohort.

Variation and inconsistencies in palliative care initiation and delivery have limited the applicability and role of research in informing evidence-based practice [ 6 ]. A journey map approach may provide one solution to address these challenges. The journey mapping tool used in this study was found to enable a patient-centred focus to the clinician’s perspective, increasing opportunities to pro-actively identify pivot-points and deliver more effective patient care.

In comparison to conventional medical records, journey maps link patient healthcare encounters longitudinally, promoting continuity and a holistic understanding of care across settings and over time. As described in conceptual studies, journey maps offer a perspective that takes into account the more dynamic and multidimensional aspects of healthcare interactions to facilitate enhanced insight into the patient experience within medical research [ 10 , 18 ]. This enables a more integrated interpretation and awareness of individual episodes of care and how these contribute to a patient’s overall health and their interaction with health services. Our participants also noted that journey mapping enabled greater emphasis on particular patient outcomes that may be difficult to observe or measure using conventional research methods. The journey mapping tool was also able to highlight gaps in care and facilitate recognition of patterns of disease progression and deterioration with a greater emphasis on patient needs and experiences.

The use of the journey mapping approach has further enabled identification of barriers and potential biases to providing effective care. This study confirms that journey mapping as a tool is effective at identifying specific barriers and trends in care provision and increase opportunities for care providers to pro-actively and appropriately address these.

Journey maps have traditionally been used in research to review and analyse the consumer experience and provide feedback on avenues for development [ 7 ]. Our panel consensus affirmed that journey mapping had applications as a clinical audit tool to identify gaps in care and opportunities for improvement when used to assess retrospective patient experiences. This is consistent with known utilities of previous journey mapping tools. Other identified benefits included potential to achieve better collaboration between healthcare providers, enabling smoother transitions of care and improving communication between healthcare providers and patients.

Limitations of this study include the design and interface of the journey mapping tool. Following a thorough search, pre-existing journey mapping software and tools were considered inappropriate for this study as they were oversimplified, unable to convey complex information appropriately and not designed for use in a medical setting. Consequently, self-designing a tool was considered the most suitable approach. The technical limitations identified did not reflect the utility of the journey mapping paradigm.

The retrospective nature of this study prohibits direct patient feedback. Consequently, the patient and caregiver perspective, including quality of life and symptom burden experienced were not well represented. Future research utilising a prospective approach with patient and caregiver involvement is needed to address these research gaps.

The response rate to the initial Delphi questionnaire was only 50 % due to time constraints and limited ability to accommodate delayed responses, however the response rate to the second Delphi questionnaire was 100 %. While this does limit the diversity of responses, it suggests good retention and engagement of involved participants with meaningful contributions.

The size of the Delphi panel in this study was seven. Studies have noted that smaller panels are still able to provide effective and reliable results and a minimum panel size of seven is considered suitable in most cases [ 19 , 20 ]. Our modified approach complied with this. Despite being a single institution study, the participants come from a diverse clinical background covering multiple domains of specialty palliative care, henceforth reducing potential bias. This study demonstrates that there is a role for journey mapping in clinical practice, however, considerations must be made for future design. Given the volume of patient data available, the amount of information presented needs to be appropriately moderated to provide clarity and best utilisation of the resources available. With the gradual transition of most health services from paper medical records to electronic medical records, the inclusion of a journey mapping tool into clinical practice is becoming more feasible. As medical technology continues to grow, the potential for incorporation of artificial intelligence, machine learning and big data into journey maps could be the key to providing pro-active, holistic patient-centred care that pre-emptively anticipates patient needs.

This study is one of the first to use a journey mapping tool in clinical practice to explore the healthcare journey and patient experience on a larger scale. The maps were used to depict a more fluid and continuous interpretation of the patient healthcare experience which enabled a more holistic and patient-centred analysis of palliative care provision. Furthermore, this is one of the first medical journey mapping studies to consider and propose potential pivot-points and opportunities for changes in the delivery of care. The use of journey maps can enhance the holistic patient healthcare experience and enable better patient-centred care not only in the palliative care setting, but also more broadly across healthcare from both a research and clinical practice perspective. Further application studies in other contexts are required.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the confidential nature of the patient data, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–42.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, et al. Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(13):1438–45.

Article Google Scholar

King JD, Eickhoff J, Traynor A, Campbell TC. Integrated onco-palliative care associated with prolonged survival compared to standard care for patients with advanced lung cancer: a retrospective review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(6):1027–32.

Hawley P. Barriers to access to palliative care. Palliative Care. 2017;10:1178224216688887.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rodriguez KL, Barnato AE, Arnold RM. Perceptions and utilization of palliative care services in acute care hospitals. J Palliat Med. 2007;10(1):99–110.

Evans CJ, Harding R, Higginson IJ. Morecare. ‘Best practice’ in developing and evaluating palliative and end-of-life care services: a meta-synthesis of research methods for the MORECare project. Palliat Med. 2013;27(10):885–98.

Gibbons S. Journey Mapping 101. 2018; https://www.nngroup.com/articles/journey-mapping-101/ .

Crunkilton DD. Staff and client perspectives on the Journey Mapping online evaluation tool in a drug court program. Eval Program Plan. 2009;32(2):119–28.

Westbrook JI, Coiera EW, Sophie Gosling A, Braithwaite J. Critical incidents and journey mapping as techniques to evaluate the impact of online evidence retrieval systems on health care delivery and patient outcomes. Int J Med Inform. 2007;76(2–3):234–45.

McCarthy S, O’Raghallaigh P, Woodworth S, Lim YL, Kenny LC, Adam F. An integrated patient journey mapping tool for embedding quality in healthcare service reform. J Decision Syst. 2016;25(sup1):354–68.

Hide E, Pickles J, Maher L. Experience based design: a practical method of working with patients to redesign services. Clin Gov. 2008;13(1):51–8.

Trebble TM, Hansi N, Hydes T, Smith MA, Baker M. Process mapping the patient journey: an introduction. BMJ. 2010;341:c4078.

Yang T-H. Case study: application of enhanced Delphi method for software development and evaluation in medical institutes. Kybernetes. 2016;45(4):637–49.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ. Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16(1):1609406917733847.

Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1985.

Book Google Scholar

Cohen D, Crabtree B. Qualitative Research Guidelines Project. 2006; http://www.qualres.org/HomeRefl-3703.html .

Ben-Tovim DI, Dougherty ML, O’Connell TJ, McGrath KM. Patient journeys: the process of clinical redesign. Med J Aust. 2008;188(S6):S14–7.

PubMed Google Scholar

Linstone H. The Delphi technique. Handbook of Futures Research. Westport: Greenwood; 1978.

Google Scholar

Akins RB, Tolson H, Cole BR. Stability of response characteristics of a Delphi panel: application of bootstrap data expansion. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:37–37.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge and extend our thanks to Kevin Shi who contributed to the Python code used for the journey map visuals.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Medicine Nursing and Health Sciences, Monash University, Clayton, VIC, Australia

Stephanie Ly, Fiona Runacres & Peter Poon

Supportive & Palliative Care Department, McCulloch House, Monash Medical Centre, 246 Clayton Road, VIC, 3168, Clayton, Australia

Fiona Runacres & Peter Poon

Calvary Health Care Bethlehem, Parkdale, VIC, Australia

Fiona Runacres

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conceptualisation PP. Methodology: PP, FR, SL. Formal analysis PP, FR, SL. Investigation: PP, FR, SL. Writing –original draft: SL. Writing- Review and Editing: PP, FR. Supervision : PP, FR. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Peter Poon .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from Monash Health Human Research Ethics Committee Monash Health Ref: RES-29-0000-071Q) and Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project ID: 18853). Informed consent from patients was not required as this was a retrospective audit of pre-existing available data which was de-identified prior to analysis. All participants of the Delphi questionnaire were provided with an explanatory statement and by completing and returning the questionnaires, consent was implied.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ly, S., Runacres, F. & Poon, P. Journey mapping as a novel approach to healthcare: a qualitative mixed methods study in palliative care. BMC Health Serv Res 21 , 915 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06934-y

Download citation

Received : 10 April 2021

Accepted : 24 August 2021

Published : 04 September 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06934-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Patient journey mapping

- Health services research

- Palliative care

- Illness trajectory

- Proactive healthcare

- Medical informatics

- Patient-centred care

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Microbiol Biol Educ

- v.19(3); 2018

A Systematic Approach to Teaching Case Studies and Solving Novel Problems †

Carolyn a. meyer.

1 Department of Biomedical Sciences, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523

Heather Hall

Natascha heise, karen kaminski.

2 School of Education, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523

Kenneth R. Ivie

Tod r. clapp, associated data.

Both research and practical experience in education support the use of case studies in the classroom to engage students and develop critical thinking skills. In particular, working through case studies in scientific disciplines encourages students to incorporate knowledge from a variety of backgrounds and apply a breadth of information. While it is recognized that critical thinking is important for student success in professional school and future careers, a specific strategy to tackle a novel problem is lacking in student training. We have developed a four-step systematic approach to solving case studies that improves student confidence and provides them with a definitive road map that is useful when solving any novel problem, both in and out of the classroom. This approach encourages students to define unfamiliar terms, create a timeline, describe the systems involved, and identify any unique features. This method allows students to solve complex problems by organizing and applying information in a logical progression. We have incorporated case studies in anatomy and neuroanatomy courses and are confident that this systematic approach will translate well to courses in various scientific disciplines.

INTRODUCTION

There is increasing emphasis in pedagogical research on encouraging critical thinking in the classroom. The specific mental processes and behaviors involved require the individual to engage in reflective and purposeful thinking. Critical thinking encompasses the ability to examine ideas, make decisions, and solve problems ( 1 , 2 ). The skills necessary to think critically are essential for learners to evaluate multiple perspectives and solve novel problems in the classroom and throughout life. Career success in the 21st century requires a complex set of workforce skills. Current labor market assessments indicate that by the year 2020, the majority of occupations will require workers to display cognitive skills such as active listening, critical thinking, and decision making ( 3 , 4 ). In particular, current studies show that the US economy is impacted by a deficit of skilled workers able to solve problems and transfer learning to any unique situation ( 3 ).

The critical thinking skills necessary to tackle novel problems can best be addressed in higher education institutions ( 5 , 6 ). Throughout education, and specifically in college courses, students tend to be required to regurgitate knowledge through a myriad of multiple-choice exams. Breaking this habit and incorporating critical thinking can be difficult for students. While the ability to recite information is helpful for establishing base knowledge, it does not prepare students to tackle novel problems. Ideally, the objective of any course is to encourage students to move beyond recognition of knowledge into its application ( 7 ). Considering this, the importance of critical thinking is widely accepted; however, there has been some debate in educational research regarding how to teach these skills ( 8 ). Research has demonstrated that students show significant improvements in critical thinking as a result of explicit methods of instruction in related skills ( 9 , 10 ). Explicit instruction provides a protocol on how to approach a problem. By establishing the necessary framework to work through unfamiliar details, we enable students to independently solve complex problems.

These skills, which are important in every facet of the workforce, are vital for students in the sciences ( 10 , 11 ). Here, we discuss a specific process that teaches students a systematic approach to solving case studies in the anatomical sciences. Case studies are a popular method to encourage critical thinking and engage students in the learning process ( 12 ). While the examples described here are specifically designed to be implemented in anatomy and neuroanatomy courses, this platform lends itself to teaching critical thinking skills across scientific disciplines. This four-step approach encourages students to work through four separate facets of a problem:

- Define unfamiliar terms

- Create a timeline associated with the problem

- Describe the (anatomical) systems involved

- Identify any unique features associated with the case

Often, students start by trying to plug in memorized facts to answer a complicated question quickly. With the four-step approach, students learn that before “solving” the case study, they must analyze the information presented in the case. The case studies implemented are anatomically-based case studies that emphasize important structural relationships. The case may include terminology with which the students are not familiar. They therefore begin by identifying and defining unfamiliar terms. They then specify the timeline in which the problem occurred. Establishing a timeline and narrowing the focus can be critical when considering the relevant pathology. Students must then describe the anatomical systems involved (e.g., musculoskeletal or circulatory), and finally list any additional unique features of the case (e.g., lateral leg was struck or patient could not abduct the right eye). By dissecting the details along the lines of these four categories, students create a clear roadmap to approach the problem. Case studies with a clinical focus are complex and can be overwhelming for unpracticed students. However, teaching students to follow this systematic approach gives them the tools to begin to carefully dismantle even the most convoluted problem.

Intended audience

This approach to solving case studies has been applied in undergraduate courses, specifically in the sciences. This curriculum is currently utilized in both human gross anatomy and functional neuroanatomy capstone courses. While it is ideal to implement this process in a course that runs in parallel with a lecture-heavy course, it can also be utilized with case studies in a typical lecture class.

Anatomy-based case studies lend themselves well to this problem-solving approach due to the complexities of clinical problems. However, we believe with an appropriately designed case study, this model of teaching critical thinking can easily be expanded to any discipline. This activity encourages critical thinking and engages students in the learning process, which we believe will better prepare them for professional school and careers in the sciences.

Prerequisite student knowledge

Required previous student knowledge only extends to that which students learn through the related course taken previously or concurrently. Application of this approach in different classroom settings only requires that students have a basic understanding of the material needed to solve the case study. As such, the case study problem and questions should be built around current topics being studied in the classroom.

Using unfamiliar words teaches students to identify important information. This encourages integration of information and terminology, which can be critical for understanding anatomy. Simple terms, like superficial or deep, guide discussions about anatomical relationships. While students may be able to recite the definitions of these concepts, applying that information to a case study requires integrating the basic definition with an understanding of the relevant anatomy. Specific prerequisite knowledge for the sample case study is detailed in Appendix 1 .

Learning time

This process needs to be learned and practiced over the course of a semester to ensure long-term retention. With structured and guided attempts, students will be able to implement this approach to solving case studies in one 50-minute class period ( Table 1 ). The course described in this study is a capstone course that meets once weekly. Each 50-minute class period centers around working through a case study. As some class sessions are reserved for other activities, students complete approximately 10 case studies during the semester. Students begin to show increased confidence with this method within a few weeks and ultimately are able to integrate this approach into their critical thinking skillset by the end of the semester. Presentation of the case study, individual or small group work, and class discussion are all achieved in one standard class session ( Table 1 ). The current model does not require student work prior to the class meeting. However, because this course is taken concurrently with a related, content-heavy lecture component, students are expected to be up to date on relevant material. Presenting the case study in class to their peers encourages students to work through the systematic approach we describe here. Each case study is designed to correlate with current topics from the lecture-based course. Following the class period, students are expected to complete a written summary of the discussed case study. The written summary should include a detailed explanation of the approach they utilized to solve the problem, as well as a definitive solution. Written summaries are to be completed two days after the original class period.

Anticipated in-class time to implement this model.

| Activity | ApproximateTime Anticipated |

|---|---|

| Presentation of the case study | 5 minutes |

| Individual or small group work | 15 minutes |

| Class discussion | 30 minutes |

Learning objectives

This model for teaching a systematic approach to solving case studies provides a framework to teach students how to think critically and how to become engaged learners when given a novel problem. By mastering this technique, students will be able to:

- Recognize words and concepts that need to be defined before solving a novel problem

- Recall, interpret, and apply previous knowledge as it relates to larger anatomical concepts

- Construct questions that guide them through which systems are affected, the timeline of the pathologies, and what is unique about the case

- Formulate and justify a hypothesis both verbally and in writing

As a faculty member, it can be challenging to create appropriate case studies when developing this model for use in a specific classroom. There are resources that provide case studies and examples that can be tailored to specific classroom needs. The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science (University at Buffalo) can be a useful tool. The ultimate goal of this model is to teach an approach to problem solving, and a properly designed case study is crucial to success. To build an effective case study, faculty must include sufficient information to provide students with enough base knowledge to begin to tackle the problem. This model is ideal in a course that pairs with a lecture-heavy component, utilized in either a supplementary course or during a recitation. The case study should be complex and not quickly solved. An example of a simplified case study utilized in Human Gross Anatomy is detailed in Appendix 1 .

This particular case study encourages students to think through the anatomy of the lateral knee, relevant structures in this area, and which muscle compartments may be affected based on movement disabilities within the case. While more complex case studies can certainly be developed for the Neuroanatomy course through Clinical Case Studies, this case study provides a good example of a problem to which students cannot immediately provide the answer. They must think critically through the four-step process to identify the “diagnosis” for this patient.

This approach to solving case studies can be integrated into the classroom with no special materials. However, we use a Power-Point presentation and personal whiteboards (2.5’ × 2’) to both improve delivery of the case study and facilitate small group discussion, respectively. The Power-Point presentation is utilized by faculty to assist in leading the classroom discussion, prompting student responses and projecting relevant images. As the faculty member is presenting the case study during the first five minutes of class ( Table 1 ), the wording of the case study can be displayed on the PowerPoint slide as a reference while students take notes.

Faculty instructions

It is helpful to first present an overview of the approach and to solve a case study together as a class. We recommend giving students a lecture describing the benefits of a systematic approach to case studies and emphasizing the four-step approach outlined in this paper. Following this lecture, it is imperative that faculty walk the students through the first case study. This helps to familiarize students with the approach and lays out expectations on how to break down the individual components of the case. During the initial case study, faculty must heavily moderate the discussion, leading students through each step of the approach using the provided Case Study Handout ( Appendix 2 ). In subsequent weeks, students can be expected to show increasing independence.

Following initial presentation of the case study in class, students begin work that is largely independent or done in small groups. This discussion has no grades assigned. However, following the in-class discussion and small group work, students are asked to detail their approach to solving the case study and their efforts are graded according to a set rubric ( Appendix 3 ). This written report should document each step of their thought process and detail the questions they asked to reach the final answer, providing students with a chance for continual self-evaluation on their mastery of the method.

Implementing this model in the classroom should focus not only on the individual student approach, but also on creating an encouraging classroom environment and promoting student participation. Student questions may prompt other student questions, leading to an engaging discussion-based presentation of the case study, which is crucial to increasing confidence among students, as has been seen with the data represented in this paper. When moderating the discussion, it is important that faculty emphasize to students that the most critical goal of the exercise is to learn how to ask the next most appropriate question. The questions should begin with broad concepts and evolve to discussing specific details. Efforts to quickly arrive at the answer should be discouraged.

Students should be randomly assigned to groups of two to three individuals as faculty members moderate small group discussion during class. Randomly assigning students to different groups each week encourages interaction between all students in the class and promotes a collaborative environment. Within their small groups, students should work through the systematic four-step process for solving a novel problem. Students are not assigned specific roles within the group. However, all group members are expected to contribute equally. During this process, it can be beneficial to provide students with a template to follow ( Appendix 2 ). This template guides their discussion and encourages them to use the four-step process. Additionally, each small group is given a white board that they can use to facilitate their small group discussions. Specifically, asking students to write down details of each of the four facets of the problem (definitions, timeline, systems involved, unique features) and how they arrived at these encourages them to commit to their answers. This also ensures they have concrete evidence to support their “diagnosis” and that they have confidence in presenting it to the class. Two or three small groups are chosen randomly each week to present their hypothesis to the class using their whiteboard.

Suggestions for determining student learning

The cadence of the in-class discussion can provide an informal gauge of how students are progressing with their ability to apply the systematic approach. The discussion for the initial case studies should be largely faculty led. Then, as the semester progresses, faculty should step back into a facilitator role, allowing the dialogue to be carried by the students.

Additionally, requiring students to write a detailed summary of their approach to the problem provides a strong measure of student learning. While it is important for students to document their final “diagnosis” or solution to the problem, the focus of this assignment is primarily on the process and the series of relevant questions the student used to arrive at the answer. These assignments are graded according to a set rubric ( Appendix 3 ).

Sample data

The following excerpt is from a student who showed marked improvement over the course of the semester in implementing this approach to solving case studies. The initial submission for the case study write-up was rudimentary, did not document the thought process through appropriate questions, and lacked an in-depth explanation to demonstrate any critical thinking. By the end of the semester, this student documented a logical thought progression through this four-step approach to solving the case study. This student, additionally, detailed the questions that led each stage of critical thinking until a “diagnosis” was reached (complete sample data are available in Appendix 4 ).

Initial sample

“Given loss of sensory and motor input to left lower limb, right anterior cerebral artery ischemia caused the sensory and motor cortices of the contralateral (left) lower limb to be without blood flow for a short amount of time (last night). The lack of flow led to a fast onset of motor and sensory paresis to limb.”

Final sample

“…the left vestibular nuclei which explains the nystagmus, and the left cerebellar peduncles which carry information that aids in coordinating intention movements. My next question was where in the brainstem are all of these components located together? I narrowed this to the left caudal pons. Finally, I asked which artery supplies the area that was damaged by the lesion? This would be the left anterior inferior cerebellar artery.”

Safety issues

There are no known safety issues associated with implementing this approach to solving case studies.

The primary goal of the model discussed here is to give students a method that uses critical reasoning and helps them incorporate facts into a complete story to solve case studies. We believe that this model addresses the need for teaching the specific skill set necessary to develop critical thinking and engage students in the learning process. By encouraging critical thinking, we begin to redirect the tendency to simply recite a memorized answer. This four-step approach to solving case studies is ideal for the college classroom, as it is easily implemented, requires minimal resources, and is simple enough that students demonstrate mastery within one semester. While it was designed to be used in anatomy and neuroanatomy courses, this platform can be used across scientific disciplines. Outside of the classroom, in professional school and future careers, this approach can help students to break down the details, ask appropriate questions, and ultimately solve any complex, novel problem.

Field testing

This model has been implemented in several courses in both undergraduate and graduate settings. The data and approach detailed here are specific to an undergraduate senior capstone course with approximately 25 students. The lecture-based course, which is required to be taken concurrently or as a prerequisite, provides a strong base of information from which faculty can develop complex case studies.

Evidence of student learning

Student performance on written case study summaries improved over approximately ten weeks of practicing the systematic four-step approach ( Fig. 1 ). As indicated by the data, scores improve and begin to plateau around five weeks, indicating a mastery of the approach. In the spring 2016 semester, a marked drop in scores was observed at week 8. We believe that this reflects a particularly difficult case study that was assigned that week. After observing the overall trend in scores, instructional format was adjusted to provide students with more guidance as they worked through this particular case study.

Grade performance in case study written summaries as measured with the grading rubric throughout the semester. A) Mean (with SD) grade performance in case study write-ups in the spring semester of 2016. B) Mean (with SD) grade performance in case study write-ups in the spring semester of 2017. Overall grade performance in case study written summaries improved throughout the 10 weeks in which this method was implemented in the classroom. Written summaries are graded based on a set rubric ( Appendix 3 ) that assigned a score between 0 and 1 for five different categories. Data represent the mean of students’ scores and the associated standard deviation. Improved student performance throughout the semester indicates progress in successful incorporation of this method to solve a complex novel problem.

After the class session, students were asked to provide a written summary of their findings. A set rubric ( Appendix 3 ) was used to assess students on their ability to apply basic anatomical knowledge as it relates to the timeline, systems involved, and what is unique in each case study. Students were also asked to describe the questions that they had asked in order to reach a diagnosis for the case study. The questions formulated by students indicate their ability to bring together previous knowledge to larger anatomical concepts. In this written summary, students were also required to justify the answer they arrived at in each step of the process. In addition to these four steps, students were assessed on the organization of their paper and whether their diagnosis is well supported.

Although class participation was not formally assessed, the improvements demonstrated in the written assignments were mirrored in student discussions in the classroom. While it is difficult to accurately assess how well students think critically, students demonstrated success in learning this module, which provides the necessary framework for approaching and solving a novel problem.

Student perceptions

Students were asked to answer the open response question, “Describe the process you use to figure out a novel problem or case study.” Responses were anonymized, then coded based on frequency of responses. Responses were collected at the start of the semester, prior to any instruction in the described systematic approach, and again at the end of the semester ( Figs. 2 and and3). 3 ). Overall, student comments indicated that mastering this four-step approach greatly increased their confidence in tackling a novel problem. Below are some sample student responses.

Student responses to a survey regarding their approach to solving a novel problem. Data were collected prior to and following the completion of the spring semester of 2016. A) Student approach to solving a novel problem at the beginning of the semester. B) Student approach to solving a novel problem at the end of the semester. Student responses indicate that following a semester of training in using this method, students prefer to use this four-step systematic approach to solve a novel problem.

Student responses to a survey regarding their approach to solving a novel problem. Data were collected prior to and following the completion of spring semester of 2017. A) Student approach to solving a novel problem at the beginning of the semester. B) Student approach to solving a novel problem at the end of the semester. Student responses indicate that students overwhelmingly utilize this systematic approach when solving a novel problem.

“Rather than being intimidated with a set of symptoms I can’t explain, I’m now able to break them down into simpler questions that will lead me down a path of understanding and accurate explanation.” “I now know how to address an exam question or life problem by considering what is needed to solve it. This knowledge will help me to address each problem efficiently and calmly. As a future nurse, I will benefit from developing a logical and stereotypical approach to solving problems. I have learned to assess my thinking and questioning and modify my approach to problem-solving. While the problems may be different in the future, I am confident that I will be able to efficiently learn from my successes and setbacks and continually improve.” “I’m sure I’ll use this approach when I’m faced with any other novel problem, whether it’s scientific or not. Stepping back and establishing what I know and what I need to find out makes difficult problems a lot more approachable.” “Before, I would look at all the information presented and try to find things that I recognized. Then I would simply ask myself if I knew the answer. Even if I did actually know the answer, I had no formula to make the information understandable, cohesive, or approachable. I now feel far more confident when dealing with novel problems and do not become immediately overwhelmed.”

This approach encourages students to quickly sort through a large amount of information and think critically. Although students can find the novel nature of this method cumbersome in the initial implementation in the classroom, once they become familiar with the approach, it provides a valuable platform for attacking any novel problem in the future. The ability to apply this approach to critical thinking in any discipline was also demonstrated, as is evidenced by the two following student responses.

“When I first thought about this question and when solving case studies I tried to find the answer immediately. I’m good at memorizing information and spitting it back out but not working through an issue and having a method. I definitely have a more successful way to think through complex problems and being patient and coming up with an answer.” “I already use it in many of my other classes and life cases. When I take an exam that is asking a complicated question or is in a long format, I work to break it down like I did in this class and try to find the base question and what the answer may be. It has actually helped significantly.”

Possible modifications

Currently, students are randomly assigned to groups each week. In future semesters, we could improve small group work by utilizing software that helps to identify individual student strengths and assign groups accordingly. Additionally, while students are given flexibility within their small groups, if groups struggle with equality of workload we could assign specific roles and tasks.

We are also using this model in a large class (100 students) and assessing understanding of the case study through instant student response questions (ICLICKER). While this model does not allow for the valuable in-depth classroom discussions, it still presents the approach to students and allows them to begin to implement it in solving complex problems. Preliminary data from these large classes indicate that students initially find the method difficult and cumbersome. Further development and testing of this model in a large classroom will improve its use for future semesters.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIALS

Appendix 1: sample case study, appendix 2: case study handout, appendix 3: case study grading rubric, appendix 4: student writing sample, acknowledgments.

Use of anonymized student data and student responses to surveys was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Colorado State University. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

† Supplemental materials available at http://asmscience.org/jmbe

Advertisement

A novel approach with an extensive case study and experiment for automatic code generation from the XMI schema Of UML models

- Published: 03 January 2022

- Volume 78 , pages 7677–7699, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Anand Deva Durai 1 ,

- Mythily Ganesh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3534-6285 2 ,

- Rincy Merlin Mathew 3 &

- Dinesh Kumar Anguraj 4

610 Accesses

8 Citations

Explore all metrics

Software models at different levels of abstraction and from different perspectives contribute to the creation of compilable code in the implementation phase of the SDLC. Traditionally, the development of the code is a human-intensive act and prone to misinterpretation and defects. The defect elimination process is again an arduous time-consuming task with increased time-to-deliver and cost. Hence, a novel approach is proposed to generate the code with the activity diagram and sequence diagram as the focus. The activity diagram and sequence diagrams and are defined as part of the UML definition to define the object flow of the system and interaction between the objects, respectively. An XMI schema is a text representation of any software model that is exported from a modeling tool. The modeling tool BoUML exports the required schema from the given input models such as sequence diagrams and activity diagrams. The proposed JC_Gen extracts artifacts from the XMI schema of these two models to generate the code automatically. The focus is mainly on class definition, member declaration, methods’ definition, and function call in generated code.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price excludes VAT (USA) Tax calculation will be finalised during checkout.

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

source model

Similar content being viewed by others

Generation of Java Code from UML Sequence and Class Diagrams

Integrating UML and ALF: An Approach to Overcome the Code Generation Dilemma in Model-Driven Software Engineering

Static generation of UML sequence diagrams

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

James B, “System Development Life Cycle (SDLC)—Risk Management Frammework.” https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/risk-management-framework/9781597499958/B9781597499958000053.xhtml Accessed June 03 2021

Zhu ZJ, Zulkernine M (2009) A model-based aspect-oriented framework for building intrusion-aware software systems. Inf Softw Technol 51(5):865–875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2008.05.007

Article Google Scholar

George MLV, Vadakkumcheril T, Mythily M (2013) A simple implementation of UML sequence diagram to java code generation through XMI representation. Int J Comput Theory Eng 3(12):35–41. https://doi.org/10.7763/IJCTE.2009.V1.6

Kong J, Zhang K, Dong J, Xu D (2009) Specifying behavioral semantics of UML diagrams through graph transformations. J Syst Softw 82(2):292–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2008.06.030

Cruz-Lemus JA, Genero M, Caivano D, Abrahão S, Insfrán E, Carsí JA (2010) Assessing the influence of stereotypes on the comprehension of UML sequence diagrams: a family of experiments. Inf Softw Technol 53(12):1391–1403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2011.07.002

Babenko LP (2003) UML-based software engineering. Cybernet Syst Anal 39(1):65–70

Zou Y, Xiao H, Chan B (2007) Weaving business requirements into model transformations. Business, 1–10

de Castro V, Marcos E, Vara JM (2011) Applying CIM-to-PIM model transformations for the service-oriented development of information systems. Inf Softw Technol 53(1):87–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2010.09.002

Asztalos M, Lengyel L (2008) A metamodel-based matching algorithm for model transformations. Computational Cybernetics, 2008. ICCC 2008. IEEE International Conference on, pp 151–155

Sanchez Cuadrado J, Guerra E, de Lara J (2014) A component model for model transformations. IEEE Trans Softw Eng 40(11):1042–1060. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSE.2014.2339852

Czarnecki K, Helsen S (2003) Classification of model transformation approaches. pp 1–17

Bollati VA, Vara JM, Jiménez Á, Marcos E (2013) Applying MDE to the (semi-)automatic development of model transformations. Inf Softw Technol 55(4):699–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2012.11.004

Mythily M, Valarmathi ML, Durai CAD (2018) Model transformation using logical prediction from sequence diagram: an experimental approach. Clust Comput. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10586-017-1618-5

Niaz IA, Tanaka J (2005) An object-oriented approach to generate java code from UML statecharts. Int J Comput Inf Sci 6(2):83–98

Google Scholar

Niaz IA, Tanaka J, Mapping uml statecharts to java code

Niaz IA, Tanaka J Code generation from uml statecharts

Jakimi A, Elkoutbi M (2009) Automatic code generation from UML statechart. Int J Eng Technol 1(2):165–168

Burke PW, Sweany P (2007) Automatic code generation through model-driven design

Usman M, Nadeem A (2009) Automatic generation of java code from UML diagrams using UJECTOR. Int J Softw Eng Appl 3(2):21–37

Parada AG, Siegert E, de Brisolara LB (2011) Generating java code from UML class and sequence diagrams. Int J Comput Inf Sci, 99–101

Engels GW, Hücking R, Sauer S (1999) UML collaboration diagrams and their transformation to Java. In: International Conference on the Unified Modeling Language, pp 473–488. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-46852-8_34

Reinhartz-berger I, Dori D (2004) “Object-process methodology (OPM) vs. UML : a code generation perspective

Stavrou A, Papadopoulos GA (2007) Automatic generation of executable code from software architecture models. In: information system development, Springer, Boston, MA, 2007, pp 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-78578-3_36

Singh S (2012) Effort reduction by automatic code generation. Int J Comput Sci Eng Technol (lJCSET) 3(8):366–369

Rugina A, Thomas D, Olive X, Veran G (2008) Gene-auto : automatic software code generation for real-time embedded systems. In: proceedings of DASIA 2008 data systems in aerospace, no 1

Robbins JE, Redmiles DF (2000) Cognitive support, UML adherence, and XMI interchange in Argo/UML. Inf Softw Technol 42(2):79–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0950-5849(99)00083-X

Chen H (2020) Design and implementation of automatic code generation method based on model driven. J Phys Conf Series. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1634/1/012019

Bruno, “BOUMLtutorial,” 2011. http://www.bouml.fr/tutorial/tutorial.html

Barclay K, Savage AJ (2004) Object-oriented design with UML and java. Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, [Online]. Available: http://digilib.mercubuana.ac.id/manager/n!@file_ebook/Isi1964329425705.pdf

Domínguez E, Lloret J, Pérez B, Rodríguez Á, Rubio ÁL, Zapata MA (2011) Evolution of XML schemas and documents from stereotyped UML class models: a traceable approach. Inf Softw Technol 53(1):34–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2010.08.001

Dimaridou V, Kyprianidis AC, Papamichail M, Diamantopoulos T, Symeonidis A (2019) Towards modeling the user-perceived quality of source code using static analysis metrics. ICSOFT 2017—Proceedings of the 12th International Conference On Software Technologies, no. March 2019, pp 73–84, 2017, https://doi.org/10.5220/0006420000730084

Kosower DA, Lopez-Villarejo JJ (2015) Flowgen: flowchart-based documentation for C++ codes. Comput Phys Commun 196:497–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2015.05.029

Flater D, Martin P, Crane M (2009) Rendering UML Activity Diagrams as Human-Readable Text. Ike , pp 207–213, [Online]. Available: http://dblp.uni-trier.de/db/conf/ike/ike2009.html#FlaterMC09