- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 15 February 2022

Determining intention, fast food consumption and their related factors among university students by using a behavior change theory

- Alireza Didarloo 1 ,

- Surur Khalili 2 ,

- Ahmad Ali Aghapour 2 ,

- Fatemeh Moghaddam-Tabrizi 3 &

- Seyed Mortaza Mousavi 4 , 5

BMC Public Health volume 22 , Article number: 314 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

21k Accesses

6 Citations

Metrics details

Today, with the advancement of science, technology and industry, people’s lifestyles such as the pattern of people’s food, have changed from traditional foods to fast foods. The aim of this survey was to examine and identify factors influencing intent to use fast foods and behavior of fast food intake among students based on the theory of planned behavior (TPB).

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 229 university students. The study sample was selected and entered to the study using stratified random sampling method. Data were collected using a four-part questionnaire including Participants’ characteristics, knowledge, the TPB variables, and fast food consumption behavior. The study data were analyzed in SPSS software (version 16.0) using descriptive statistics (frequencies, Means, and Standard Deviation) and inferential statistics (t-test, Chi-square, correlation coefficient and multiple regressions).

The monthly frequency of fast food consumption among students was reported 2.7 times. The TPB explained 35, 23% variance of intent to use fast food and behavior of fast food intake, respectively. Among the TPB variables, knowledge ( r = .340, p < 0.001) and subjective norm ( r = .318, p < 0.001) were known as important predictors of intention to consume fast foods - In addition, based on regression analyses, intention ( r = .215, p < 0.05), perceived behavioral control ( r = .205, p < 0.05), and knowledge ( r = .127, p < 0.05) were related to fast food consumption, and these relationships were statistically significant.

Conclusions

The current study showed that the TPB is a good theory in predicting intent to use fast food and the actual behavior. It is supposed that health educators use from the present study results in designing appropriate interventions to improve nutritional status of students.

Peer Review reports

Over the past few decades, non-communicable diseases such as eczema, asthma, cancer, type 2 diabetes, obesity, etc. have increased in developed countries [ 1 , 2 ]. Also, these diseases are more prevalent with increasing urbanization in developing countries [ 3 , 4 , 5 ]. The occurrence of many non-communicable diseases is related to diet [ 6 ]. Food habits are rooted from cultural, environmental, economic, social and religious factors. An effective factor in the development of chronic diseases is lifestyle, dietary patterns and habits. Inappropriate food habits and unhealthy environments have increased the incidence of non-communicable diseases in the world [ 7 , 8 ].

Many developing countries with a tendency towards Western dietary culture go away from traditional and local diets [ 6 ]. Healthy foods with nutrients have been replaced by new foods called fast foods [ 9 ]. Fast food is the food prepared and consumed outside and often in fast food restaurants [ 10 ]. Fast food is often highly processed and prepared in an industrial fashion, i.e., with standard ingredients and methodical and standardized cooking and production methods [ 10 ]. In fast food, vitamins, minerals, fiber and amino acids are low or absent but energy is high [ 9 ]. Fast food consumption has increased dramatically in the last 30 years in European and American countries [ 11 ].

Previous studies reported patterns of inappropriate and harmful food consumption in Iranian children and adolescents [ 12 , 13 ]. Most fast food customers are adolescents and youth, as these products are quickly and easily produced and relatively inexpensive [ 14 ]. One Iranian study shows that 51% of children eat inappropriate snacks and drinks over a week [ 15 ]. It is also reported that adults today consume fast food more than previous generations [ 16 ]. Faqih and Anousheh reported that 20% of adolescents and 10% of adults consumed sandwiches 3 or more times a week [ 17 ].

According to two studies, children and adolescents who consume fast food have received more energy, saturated fat, sodium, carbohydrates and more sugar than their peers, but they have less fiber, vitamin A and C, and less fruit and vegetables [ 18 , 19 ]. Also, because of the use of oils to fry these foods at high temperatures, these types of foods may contain toxic and inappropriate substances that threaten the health of consumers [ 20 ].

In a study in the United States on young people between 13 and 17 years old, it was found that there is a significant relationship between weight gain and obesity with pre-prepared foods [ 21 ]. According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2007–2008), 17% of children aged 2 to 19 years and 34% of those aged 20 years and older were obese [ 22 ]. Many Health problems were caused by human health behavior(e.g. exercising regularly, eating a balanced diet, and obtaining necessary inoculations, etc.) and studying behavior change theories/models provides a good insight into the causes and ways of preventing these problems [ 23 ]. One of these theories is the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), which is a developed form of the Theory of reasoned action (TRA), and describes a healthy behavior that is not fully under the control of a person [ 24 ]. This theory can successfully predict eating habits and behaviors, and recently this theory has received considerable attention from researchers in identifying norms and beliefs related to the use of fast food [ 25 ].

Based on the TPB, intention to conduct a behavior with following three concepts is controlled: 1. Attitudes (positive and negative evaluation of a behavior), 2. Subjective norms (social pressure received from peers, family, health care providers for doing or not doing a given health behavior), 3. Perceived behavior control (This refers to a person’s perception of the ease or difficulty of performing the behavior of interest.) [ 26 , 27 , 28 ].

The TPB has been tested on different behaviors such as healthy food choice [ 24 ], physical activity [ 29 ], and fast food consumption [ 30 ]. For instance, the study conducted by Seo et al. showed that fast food consumption behavior was significantly associated with behavioral intention and perceived behavioral control. In addition, their findings highlighted that behavioral intention was significantly related to subjective norm and perceived behavioral control [ 28 ].

Given that our study population has cultural diversity and nutritional behaviors different from the societies of other countries and According to the mentioned materials, the researchers decided to test the study with the aim of investigating and explaining the intention and behavior of fast food consumption and their related factors based on the TPB among Urmia University of Medical Sciences students. The results of this study will increase the awareness and knowledge about fast food and, in addition, its results can be used in research, hospitals and healthcare settings.

This cross-sectional study was performed on students of Urmia University of Medical Sciences located in northwest Iran in academic year of 2018–2019. The inclusion criteria for the study are females and males who studied at Urmia University of Medical Sciences, and students’ voluntary participation in the study and obtaining written consent from the students and University principals for the students’ participation in the study. The lack of willingness to continue participating in the study and not signing the informed consent form were considered as exclusion criteria.

According to the results of the study of Yar Mohammadi and et al. [ 31 ], with a 95% confidence interval and an error of 0.05, using the formula for estimating the proportion in society, taking into account the 10% drop rate, sample size was estimated 330students. A randomized stratified sampling method was used to select the study samples. The study sample was randomly selected from each of the strata based on the share of the total sample.

Questionnaire

The data gathering tool in this study was a self-reported questionnaire (Additional file 1 ), which was designed according to the existing measures in scientific literature [ 32 , 33 , 34 ]. The study instrument was translated from English to Persian using a standard forward-backward translation technique [ 35 ]. The original instrument was translated by a bilingual specialist. The Persian version was then retranslated into English by two independent bilingual professionals to assess retention of the original meaning in the source language. Subsequently, translators worked separately in the translation process and then prepared the final version of the Persian translation. Content validity of The Persian version of questionnaire was evaluated by a panel of experts such as 3 nutrition specialists, 3 health education specialists, and 2 instrument designers. After receiving their comments, crucial revisions were conducted in the study tool. Finally, validity of the study instrument was confirmed. The present questionnaire including four following sections:

General characteristics

The first part contains personal information such as age, gender, weight, height, field of study, student education, father’s education, mother’s education, father job, mother’s job, ethnicity, marital status, participating in nutrition educational classes, students’ monthly income, family’s monthly income, housing status, information resource for healthy nutrition.

Constructs of the TPB

The second part contains questions about the constructs of the theory of planned behavior (attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control and behavioral intention). In general, attitudes, subjective norm and perceived behavioral control of students were measured using indirect items. The internal reliability of all subscales of the TPB variables was good, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.852.

Attitude toward fast food use

The attitude of the people was evaluated using 28 indirect items (14 items of behavioral beliefs, 14 items of expectations evaluation) based on five-point the Likert scale (from strongly agree to strongly disagree) or (from very important to not at all important), and the score of each item varied from 1 to 5. The minimum and maximum score for the attitude subscale was 14 and 350, respectively. The internal reliability of attitude subscale was good, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.778.

Subjective norm

Subjective norms of students were measured by 10 indirect items (5 items of normative beliefs, 5 items of motivation to comply) based on five-point the Likert scale (from strongly agree to strongly disagree) or (from very important to not at all important), and the score of each item varied from 1 to 5. The minimum and maximum score for the subjective norm subscale was 5 and 125, respectively. The internal reliability of subjective norm subscale was good, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.726.

Perceived behavioral control

Perceived behavioral control were measured by 18 indirect items (9 items of control beliefs, 9 items of perceive power) based on five-point the Likert scale (from strongly agree to strongly disagree) or (from extremely difficult to extremely easy), and the score of each item varied from 1 to 5. The minimum and maximum score for the perceived behavioral control subscale was 9 and 225, respectively. The internal reliability of subscale of perceived behavioral control was good, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.815.

Behavioral intention

Behavioral intention was evaluated by 8 items based on five-point the Likert scale (from strongly agree to strongly disagree), and the score of each item varied from 1 to 5. The minimum and maximum score for the Behavioral intention subscale was 8 and 40, respectively. The internal reliability of behavioral intention subscale was good, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.821.

Knowledge of participants

And the third and fourth parts are items related to food knowledge and fast food behavior. Students’ knowledge of fast food was evaluated by 14 items, and the score of each item varied from 0 to 2. The minimum and maximum score for the knowledge subscale was 0 and 28, respectively. The internal reliability of students’ knowledge was good, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.783.

Fast food use

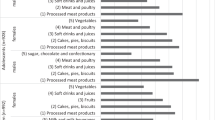

Students’ fast food consumption was assessed by frequency of use in a past month. The term “Fast food” was defined as hamburgers, doughnuts, hot dog, snack, pizza, fried chicken and fried potatoes. The frequency of fast food use was analyzed for each food category.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyzes were performed using SPSS 16.0 software. Descriptive statistics methods such as frequencies, means and standard deviations were used along with independent t and χ2 tests. Pearson correlation test was used to investigate the relationship between TPB variables with intent to use fast food and the real use of fast food. Multiple regressions were used for further analysis.

Descriptives

A total of 330 students were selected and recruited to the study, but some subjects (31 samples) were excluded from the study due to incomplete questionnaires (21cases), and no return of questionnaires (10 cases). Statistical analyses were performed on 229 students. Of these, 28.4% of the students were males and 71.6% were females. The results of the study showed that the average age for all the students was 22.10 ± 3.30 (the average age for male and female sexes were 22.66 ± 4.47 and 21.84 ± 2.50, respectively). The two sexes differed in terms of BMI, so that the mean of BMI was higher in boy students than in girls, and this difference was statistically significant. Almost more than 72% of the students had normal weight, and 28% of subjects were in other weights. Approximately 20.51, 54.50, 79.77% of the students reported the professional doctoral degree, Azeri ethnicity and single.

In addition, findings revealed that 64.90% of the participants lived in the dormitory, and 35.10% of them lived in personal or rental housing. The most common level of education for father (37.10%) and mother (44.10%) of students was diploma. Nearly, 46.50% of students gained food information (especially fast food) from health care providers, while 53.50% of them received their food information from other sources. Most students had zero monthly income, but 61.61% of the students reported their family’s monthly income more than 50 million Rials and 38.39% of their family had income lower than the mentioned amount. Table 1 provides detailed information on students’ characteristics.

Main analysis

Table 2 presents the mean score of knowledge and variables of the study-related theoretical framework. As the mean score of subjective norm, perceived behavioral control and behavioral intention in male students compared to female students was high, but those were not significant statistically( p > 0.05).

Some variables of the TPB were significantly correlated with each other ( P < 0.01, Table 3 ). In particular, fast food consumption behavior was highly ( r = 0.382) correlated with behavioral intention. Multiple regression analyses were conducted to determine the relative importance of the variables of the TPB to behavioral intention and fast food consumption behavior (Tables 4 and 5 ). In these analyzes, when the attitude toward behavior, subjective norms, and perceived control was regressed to behavioral intention, the model was very significant ( P = 0.000) and explained 0.347 of variance of behavioral intention. While attitude and perceived behavioral control were not significant, the subjective norms and students’ knowledge were significantly related to the intention to eat fast food. It seems that subjective norms and students’ knowledge to be the most important predictors of behavioral intent. Table 4 shows more information about predictors of behavioral intention.

The second model, using fast food consumption as a dependent variable, was also very significant ( P = 0.000), and explained nearly a quarter of the variance (0.231) of fast food consumption. Both behavioral intention and perceived behavioral control were significantly associated with fast food consumption, of which behavioral intention appeared to be more important. Table 5 presents more information about predictors of fast food consumption.

This investigation was conducted on a sample of university students to assess the status of their fast-food consumption. It also examined the factors affecting behavioral intent and fast food consumption by applying the TPB. The results of the present study showed that students consumed fast food at an average of 2.7 times a month. Fast food in male students was often reported more than female students. A study on fast food consumption among students at Daejeon School reported monthly frequencies of fast food types: 2.7 for burgers, 2.1 for French fries, 1.8 for chicken [ 24 ]. Results of Kim study and other similar researches [ 31 , 36 ] approximately were in line with findings of the present study.

Given that most men do not have the time and skill to make traditional foods, and because of a lot of work, they prefer to turn to fast-foods, and so they are more likely to use fast foods. Meanwhile, the results of some studies indicate that most women are not very happy from high weight and are more likely to reduce their weight [ 37 ]. Therefore women do not have a positive attitude toward obesogenic foods compared to men [ 38 ], which can be a reason for consuming less fast food among women. Instead, the results of a study done by Seo et al. In Korea indicated that fast food consumption among high school students was 4.05 times a month and this consumption was reported among boys more than girls [ 28 ]. The results of the Korean study were contrary to the results of the study, meaning that fast food in Korean samples was more than Iranian. The reason for this difference can be traced to factors such as sample size, cultural, social, and economic characteristics of the samples.

Performing and not performing the behavior by a person is a function of several factors based on the theory of planned behavior. One of these factors is the person’s intention and desire to do the behavior. Behavioral intention itself is also affected by factors such as attitude, students’ knowledge, social pressure, and perceived behavioral control. In the present study, based on linear regression analysis, students’ knowledge and social pressure were both related to their intention and consume fast foods. That is, students who had the necessary information about nutrition, especially fast foods, had a high intent to choose and consume foods.

Several studies have examined the relationship between knowledge of foods and their contents and attitudes toward fast foods and processed foods or relationship between attitudes toward food additives and food choice behavior [ 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 ]. Aoki et al. [ 39 ] found that information about food and its contents positively or negatively affects attitudes and intentions towards food. They pointed out that food information was important for consumers in choosing food. Back and Lee [ 43 ] found that consumers had inadequate and incorrect information about foods, which could affect their attitudes or intent. These studies suggest that providing more information about foods and their compounds can help them to improve their attitude towards foods. Therefore, training on the performance, benefits and safety of foods, including positive and negative sides, should prevent misunderstandings about food supplements and reduce food safety concerns.

The findings of the present investigation showed that subjective norms of students were effective on intent to use fast foods. Friends had the most impact on the plan to eat fast foods, as expected. In addition, the normative beliefs of students were also more positive for friends than family and teachers. This conclusion suggests that most training programs should focus on their friends as a critical group that may affect intent to use fast foods.

Results of some previous studies were similar to findings of the current study. One study conducted by Mirkarimi et al. highlighted that subjective norms had the main role on students’ intent to use fast foods [ 44 ]. In the other words, they found that behavioral intention was affected by subjective norms. In addition, the study of Yarmohammadi and et al. showed that subjective norms predict intention and behavior [ 31 ].

In this study, TPB demonstrated to be a sound conceptual framework for explaining closely35% of the variance in students’ behavioral intention to consume fast-food. Among the TPB variables, subjective norm and knowledge of students were the most important predictors of intention to use fast foods. These findings are consistent with other results that identify that subjective norms have a significant effect on consuming fruits and vegetables [ 45 ]. In study of Lynn Fudge, Path analysis highlighted that TPB explained adolescent fast-food behavioral intention to consume fast food. The model identified subjective norms had the strongest relationship with adolescent behavioral intention to consume fast food [ 46 ].

The results of this study showed that the attitude toward fast food behavior did not predict intent and the behavior. However, some studies have reported contradictory findings with the study. For example, the findings of Stefanie and Chery’s study showed that attitude was a predictor for intent to use healthy nutrition [ 47 ]. Yarmohammadi and colleagues stated in their study that attitude was the most important predictor of behavioral intent [ 31 ]. In the study of determinants of fast food intake, Dunn et al. has identified attitude as a predictor of the intent of fast food consumption [ 32 ]. The results of studies by Seo et al., Ebadi et al., along with the findings of this study, showed that attitude toward fast food consumption is not significantly related to behavioral intention [ 28 , 48 ]. Based on the findings of the current study, fast-food consumption of students was also influenced by some the TPB variables. Multiple linear regression analyses revealed that the constructs of the TPB explained fast food use behaviors with R-squared (R 2 ) of 0.23. In these analyses, intention, perceived behavioral control, and knowledge were known as effective factors on fast-food consumption. Among the TPB constructs, behavioral intention was the most important predictor of fast-food consumption. The intention plays a fundamental role in the theory of planned behavior. The intentions include motivational factors that influence behavior and show how much people want to behave and how hard they try to do the behavior [ 49 ]. In study Ebadi et al., regression analysis showed the intention as a predictor of fast food consumption behavior [ 48 ]. In studies of Stefanie et al. and Seo et al., has reported intention as correlate of the behavior [ 28 , 47 ]. All these studies confirmed and supported this part of our study findings. In addition, the results indicated that perceived behavioral control directly influenced the behavior of fast-food consumption. Some investigations confirmed this portion of our results. For instance, the results of Dunn et al. showed that perceived behavioral control (PBC) and intent predicted the behavior of fast food consumption [ 32 ]. Also, in the study of Seo et al., regression analysis showed that fast food consumption behavior was correlated with perceived behavioral control [ 28 ]. Yarmohammadi et al. found that in predicting behavior, perceived behavioral control along with intention could predict 6% of behavior [ 31 ]. Although this study provides valuable knowledge regarding the relationships between behavioral intent and TPB variables, this study, like other studies, has a number of limitations. First, a cross-sectional study was used to examine the relationship between the variables. Due to the fact that in cross-sectional studies, all data are collected in a period of time, as a result, these studies do not have the necessary ability to examine the cause-and-effect relationships between variables. Second, the results of this type of study can only be generalized to populations with similar characteristics and have no generalizability beyond that. Third, since the data of this study were collected using the self-report questionnaire, the respondents may have errors and bias in completing the questionnaire and this can affect the results of the study.

In sum, this study was conducted to identify factors influencing intention and behavior of fast-food consumption among students by using the theory of planned behavior. The findings revealed that changeability of students’ intention to use fast food and their real behavior is dependent on the TPB variables. As this theoretical framework explained 35, 23% of intent to consume fast-foods and fast-food consumption, respectively. Among the TPB constructs, knowledge and subjective norm were known as the most important predictors of intention to use fast foods. In addition, the results indicated that intention and perceived behavioral control were the most important factors influencing consumption of fast foods among participants. It is imperative that health educators and promoters use these results in designing suitable educational interventions to improve people’s nutritional behavior.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to confidentiality of data and subsequent research, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Theory of Planned Behavior

Theory of Reasoned Action

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

Body Mass Index

ISAAC Steering Committee. Worldwide variation in prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhino conjunctivitis, and atopic eczema: ISAAC. Lancet. 1998;351:1225–32.

Google Scholar

Anonymous. Variations in the prevalence of respiratory symptoms, self-reported asthma attacks, and use of asthma medication in the European Community respiratory health survey (ECRHS). Eur Respir J. 1996;9:687–95.

Hijazi N, Abalkhail B, Seaton A. Diet and childhood asthma in a society in transition: a study in urban and rural Saudi Arabia. Thorax. 2000;55:775–9.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Asher MI, Montefort S, Björkstén B, et al. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC phases one and three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet. 2006;368:733–43.

PubMed Google Scholar

Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Horton R, et al. Priority actions for the non-communicable disease crisis. Lancet. 2011;377:1438–47.

Devereux G. The increase in the prevalence of asthma and allergy: food for thought. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:869–74.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Nazari B, Asgari S, Sarrafzadegan N, et al. Evaluation and types of fatty acids in some of the most consumed foods in Iran. J Isfahan Med School. 2010;27(99):526–34.

Word Health Organization (WHO). Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases report of a joint WHO/FAO expert consultation. Geneva: WHO.2003. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/9241590416.pdf . [Accessed Jun 21, 2011].

Ashakiran S, Deepthi R. Fast foods and their impact on health. JKIMSU. 2012;1(2):7–15.

Vaida N. Prevalence of fast food intake among urban adolescent students. IJES. 2013;2(1):353–9.

Bowman SA, Vinyard BT. Fast food consumption of US adults: impact on energy and nutrient intakes and overweight status. J Am Coll Nutr. 2004;23(2):163–8.

Abdollahi M, Amini M, Kianfar H, et al. Qualitative study on nutritional knowledge of primary-school children and mothers in Tehran. EMHJ-Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2008;14(1):82–9.

Shahanjarini A, Shojaezadeh D, Majdzadeh R, et al. Application of an integrative approach to identify determinants of junk food consumption among female adolescents. Iran J Nutr Sci Food Technol. 2009;4(2):61–70.

Lee JS. A comparative study on fast food consumption patterns classified by age in Busan. Korean J Commun Nutr. 2007;12(5):534–44.

Dehdari T, Mergen T. A survey of factors associated with soft drink consumption among secondary school students in Farooj city, 2010. J Jahrom Univ Med Sci. 2012;9(4):33–9.

Brownell KD. Does a" toxic" environment make obesity inevitable? Obssity Manage. 2005;1(2):52–5.

Faghih A, Anousheh M. Evaluating some of the feeding behaviors in obese patients visiting affiliating health centers. Hormozgan Med J. 2008;12(1):53–60.

Paeratakul S, Ferdinand DP, Champagne CM, et al. Fast-food consumption among US adults and children: dietary and nutrient intake profile. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103(10):1332–8.

Timperio AF, Ball K, Roberts R, et al. Children’s takeaway and fast-food intakes: associations with the neighbourhood food environment. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(10):1960–4.

Pour Mahmoudi A, Akbar TabarTuri M, Pour Samad A, et al. Determination of peroxide in the oil consumed in restaurants and snack bar Yasuj. J Knowledge. 2008;13(1):116–23 [In Persian].

SadrizadehYeganeh H, AlaviNaein A, DorostiMotlagh A, et al. Obesity is associated with certain feeding behaviors in high school girls in Kerman. Payesh Quarterly Summer. 2007;6(3):193–9 [In Persian].

Greger N, Edwin CM. Obesity: a pediatric epidemic. Pediatr Ann. 2001;30(11):694–700.

Ghaffari M, Gharghani ZG, Mehrabi Y, et al. Premarital sexual intercourse-related individual factors among Iranian adolescents: a qualitative study. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2016;18(2):e21220.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kim KW, Ahn Y, Kim HM. Fast food consumption and related factors among university students in Daejeon. Korean J Commun Nutr. 2004;9(1):47–57.

Harris KM, Gordon-Larsen P, Chantala K, et al. Longitudinal trends in race/ethnic disparities in leading health indicators from adolescence to young adulthood. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(1):74–81.

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211.

Branscum P, Sharma M. Using the theory of planned behavior to predict two types of snack food consumption among Midwestern upper elementary children: implications for practice. Int Quarterly Commun Health Educ. 2011;32(1):41–55.

Seo H-s, Lee S-K, Nam S. Factors influencing fast food consumption behaviors of middle-school students in Seoul: an application of theory of planned behaviors. Nutr Res Pract. 2011;5(2):169–78.

Hewitt AM, Stephens C. Healthy eating among 10-13-year-old New Zealand children: understanding choice using the theory of planned behavior and the role of parental influence. Psychol Health Med. 2007;12:526–35.

Didarloo A, Shojaeizadeh D, EftekharArdebili H, et al. Factors influencing physical activity behavior among Iranian women with type 2 diabetes using the extended theory of reasoned action. Diabetes Metab J. 2011;35(5):513–22.

Yarmohammai P, Sharirad GH, Azadbakht L, et al. Assessing predictors of behavior of high school students in Isfahan on fast food consumption using theory of planned behavior. Journal of Health Syst Res. 2011;7(4):449–59.

Dunn K, Mohr P, Wilson C, et al. Determinants of fast food consumption: an application of the theory of planned behavior. Appetite. 2011;23(57):349–57.

Dunn KI, Mohr PB, Wilson CJ, Wittert GA. Beliefs about fast food in Australia: a qualitative analysis. Appetite. 2008;51(2):331–4.

Denney-Wilson E, Crawford D, Dobbins T, Hardy L, Okely AD. Influences on consumption of soft drinks and fast foods in adolescents. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2009;18(3):447–52.

Brisling RW. The wording and translation of research instruments. In: Loner WJ, Berry JW, editors. Field Methods in Cross-cultural Research. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1986. p. 134–64.

Sanaye S, Azarghashb A, Derisi M, et al. A survey on knowledge and attitude of students of ShahidBeheshti University of medical sciences toward fast food. Scientific J Med Council Islamic Republic Iran. 2016;34(1):23–30.

Driskell JA, Meckna BR, Scales NE. Differences exist in the eating habits of university men and women at fast-food restaurants. J Nutr. 2006;26(10):524–30.

CAS Google Scholar

Morse KL, Driskell JA. Observed sex differences in fast-food consumption and nutrition self-assessments and beliefs of college students. Sci Direct J Nutr Res. 2009;29(3):173–9.

Aoki K, Shen J, Saijo T. Consumer reaction to information on food additives: evidence from an eating experiment and a field survey. J Econ Behav Organ. 2010;73:433–8.

Stern T, Haas R, Meixner O. Consumer acceptance of wood-based food additives. Br Food J. 2009;11:179–95.

Kim H, Kim M. Consumers' awareness of the risk elements associated with foods and information search behavior regarding food safety. J East Asian Soc Diet Life. 2009;19:116–29.

Seo S, Kim OY, Shim S. Using the theory of planned behavior to determine factors influencing processed foods consumption behavior. Nutr Res Pract. 2014;8(3):327–35.

Back BS, Lee YH. Consumer's awareness and policies directions on food additives-focusing on consumer information. J Consum Stud. 2006;17:133–50.

Mirkarimi K, Mansourian M, Kabir MJ, et al. Fast food consumption behaviors in high-school students based on the theory of planned behavior (TPB). Int J Pediatr. 2016;4(7):2131–42.

Murnaghan DA, Blanchard CM, Rodgers WM, et al. Predictors of physical activity, healthy eating and being smoke-free in teens: a theory of planned behavior approach. Psychol Health. 2010;25:925–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440902866894 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Julie Lynn Fudge. Explaining adolescent behavior intention to consume fast food using the theory of planned behavior. Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty Of the North Dakota State University Of Agriculture and Applied Science. lib.ndsu.nodak.edu. 2013.

Stefanie A, Chery S. Applying the theory of planned behavior to healthy eating behaviors in urban native American youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006;30(3):1–10.

Ebadi L, Rakhshanderou S, Ghaffari M. Determinants of fast food consumption among students of Tehran: application of planned behavior theory. Int J Pediatr. 2018;6(10):8307–16.

Pender NJ, Murdaugh C, Parsons MA. Health promotion in nursing practice. 4th edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall Health Inc; 2002. p. 250–5.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The article authors hereby express their gratitude to Vice Chancellors for Research of Urmia University of Medical Sciences and Education Department for supporting this study.

This study is supported by Urmia University of Medical Science, grant number(No: 2017–2323) .

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Clinical Research Institute, Urmia University of Medical Sciences, The Province of Western Azarbaijan, Urmia, 5756115198, Iran

Alireza Didarloo

Faculty of Health, Urmia University of Medical Sciences, the Province of Western Azarbaijan, Urmia, 5756115198, Iran

Surur Khalili & Ahmad Ali Aghapour

Reproductive Health Research Center, Urmia University of Medical Sciences, the Province of Western Azarbaijan, Urmia, 5756115198, Iran

Fatemeh Moghaddam-Tabrizi

Faculty of Paramedical Sciences, Urmia University of Medical Sciences, the Province of Western Azarbaijan, Urmia, 5756115198, Iran

Seyed Mortaza Mousavi

Department of Paramedical Science, School of Paramedical Sciences, Urmia University of Medical Sciences, Urmia, Iran

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contribute in conceive, design of this study. A.D, S.K, A.A,FTM and S.M contributed to the design and implementation of the research, to the analysis of the results and to the writing of the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Seyed Mortaza Mousavi .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Research has been presented in the ethics committee of Urmia University of Medical Sciences and has received the code of ethics (IR. UMSU.REC.1397.43). written informed consent was obtained from all participants in this study, and all provisions of the Helsinki Statement on Research Ethics were considered.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1..

The questionnire used in the study to collect the data. The first part of the questionnaire included General characteristics. The second part of the questionnaire consisted of the Constructs of TPB. The third part consisted of knowledge of participants. The fourth part consisted of Fast food use.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Didarloo, A., Khalili, S., Aghapour, A.A. et al. Determining intention, fast food consumption and their related factors among university students by using a behavior change theory. BMC Public Health 22 , 314 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12696-x

Download citation

Received : 07 December 2020

Accepted : 02 February 2022

Published : 15 February 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12696-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Theory of planned behavior

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 27 October 2020

Food and Health

Trends in the healthiness of U.S. fast food meals, 2008–2017

- Eleanore Alexander ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8998-4186 1 ,

- Lainie Rutkow 1 ,

- Kimberly A. Gudzune 2 , 3 ,

- Joanna E. Cohen 4 , 5 &

- Emma E. McGinty 1

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition volume 75 , pages 775–781 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

808 Accesses

6 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cardiovascular diseases

- Risk factors

This study aimed to examine trends in the healthiness of U.S. fast food restaurant meals from 2008 to 2017, using the American Heart Association’s Heart-Check meal certification criteria.

Data were obtained from MenuStat, an online database of the leading 100 U.S. restaurant chains menu items, for the years 2008 and 2012 through 2017. All possible meal combinations (entrées + sides) were created at the 20 fast food restaurants that reported entrée and side calories, total fat, saturated fat, trans fat, cholesterol, sodium, protein, and fiber. Chi-square tests compared the percent of meals meeting each American Heart Association (AHA) nutrient criterion; and the number of AHA criteria met for each year, by menu focus type.

Compared with 2008, significantly fewer fast food meals met the AHA calorie criterion in 2015, 2016, and 2017, and significantly fewer met the AHA total fat criterion in 2015 and 2016. Significantly more meals met the AHA trans fat criterion from 2012 to 2017, compared to 2008. There were no significant changes over time in the percent of meals meeting AHA criteria for saturated fat, cholesterol, or sodium.

Conclusions

Efforts to improve the healthiness of fast food meals should focus on reducing calories, total fat, saturated fat, and sodium.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

251,40 € per year

only 20,95 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Are Asian foods as “fattening” as western-styled fast foods?

Food cost and adherence to guidelines for healthy diets: evidence from Belgium

Energy intake and energy contributions of macronutrients and major food sources among Chinese adults: CHNS 2015 and CNTCS 2015

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adult Obesity Facts 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html .

CDC. FastStats - Leading Causes of Death 2018 [updated 2018-09-11. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm .

CDC. Salt 2018 [updated 2018-10-05. https://www.cdc.gov/salt/index.htm .

Rosenheck R. Fast food consumption and increased caloric intake: a systematic review of a trajectory towards weight gain and obesity risk. Obes Rev. 2008;9:535–47.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Todd JE. Changes in consumption of food away from home and intakes of energy and other nutrients among US working-age adults, 2005–2014. Public Health Nutr. 2017;20:3238–46.

Article Google Scholar

Duffey KJ, Gordon-Larsen P, Jacobs DR Jr, Williams OD, Popkin BM. Differential associations of fast food and restaurant food consumption with 3-y change in body mass index: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:201–8.

Bowman SA, Vinyard BT. Fast food consumption of U.S. adults: impact on energy and nutrient intakes and overweight status. J Am Coll Nutr. 2004;23:163–8.

Pereira MA, Kartashov AI, Ebbeling CB, Van Horn L, Slattery ML, Jacobs DR Jr, et al. Fast-food habits, weight gain, and insulin resistance (the CARDIA study): 15-year prospective analysis. Lancet. 2005;365:36–42.

An R. Fast-food and full-service restaurant consumption and daily energy and nutrient intakes in US adults. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:97–103.

Fryar CD, Hughes JP, Herrick KA, Ahluwalia N. Fast food consumption among adults in the United States, 2013–2016. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2018. Contract No.: 322

Google Scholar

Andrews C The most iconic fast food items in America: USA Today; 2020. https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2019/08/06/most-iconic-items-america-biggest-fast-food-chains/39885515/ .

Jacobson MF, Havas S, McCarter R. Changes in sodium levels in processed and restaurant foods, 2005 to 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1285–91.

Bauer KW, Hearst MO, Earnest AA, French SA, Oakes JM, Harnack LJ. Energy content of US fast-food restaurant offerings: 14-year trends. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:490–7.

Urban LE, Roberts SB, Fierstein JL, Gary CE, Lichtenstein AH. Temporal trends in fast-food restaurant energy, sodium, saturated fat, and trans fat content, United States, 1996–2013. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E229.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Jarlenski MP, Wolfson JA, Bleich SN. Macronutrient composition of menu offerings in fast food restaurants in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51:e91–7.

Rudelt A, French S, Harnack L. Fourteen-year trends in sodium content of menu offerings at eight leading fast-food restaurants in the USA. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17:1682–8.

Eyles H, Jiang Y, Blakely T, Neal B, Crowley J, Cleghorn C, et al. Five year trends in the serve size, energy, and sodium contents of New Zealand fast foods: 2012 to 2016. Nutr J. 2018;17:65.

Wolfson JA, Moran AJ, Jarlenski MP, Bleich SN. Trends in sodium content of menu items in large chain restaurants in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54:28–36.

Hearst MO, Harnack LJ, Bauer KW, Earnest AA, French SA, Oakes JM. Nutritional quality at eight US fast-food chains: 14-year trends. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44:589–94.

United States Department of Agriculture. Healthy Eating Index 2019. Available from: https://www.cnpp.usda.gov/healthyeatingindex .

Bruemmer B, Krieger J, Saelens BE, Chan N. Energy, saturated fat, and sodium were lower in entrees at chain restaurants at 18 months compared with 6 months following the implementation of mandatory menu labeling regulation in King County, Washington. J Acad Nutr Dietetics. 2012;112:1169–76.

Schoffman DE, Davidson CR, Hales SB, Crimarco AE, Dahl AA, Turner-McGrievy GM. The fast-casual conundrum: fast-casual restaurant entrees are higher in calories than fast food. J Acad Nutr Dietetics. 2016;116:1606–12.

Wu HW, Sturm R. Changes in the energy and sodium content of main entrees in US chain restaurants from 2010 to 2011. J Acad Nutr Dietetics. 2014;114:209–19.

Auchincloss AH, Leonberg BL, Glanz K, Bellitz S, Ricchezza A, Jervis A. Nutritional value of meals at full-service restaurant chains. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2014;46:75–81.

Scourboutakos MJ, Semnani-Azad Z, L’Abbe MR. Restaurant meals: almost a full day’s worth of calories, fats, and sodium. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1373–4.

Dumanovsky T, Huang CY, Nonas CA, Matte TD, Bassett MT, Silver LD. Changes in energy content of lunchtime purchases from fast food restaurants after introduction of calorie labelling: cross sectional customer surveys. BMJ (Clin Res ed). 2011;343:d4464.

Nation’s Restaurant News. 2017 Top 100: Chain Performance Nation’s Restaurant News, 2017. https://www.nrn.com/top-100-restaurants/2017-top-100-chain-performance .

Bleich SN, Wolfson JA, Jarlenski MP, Block JP. Restaurants with calories displayed on menus had lower calorie counts compared to restaurants without such labels. Health Aff (Proj Hope). 2015;34:1877–84.

MenuStat. MenuStat Methods. 2019. http://menustat.org/Content/assets/pdfFile/MenuStat%20Data%20Completeness%20Documentation.pdf .

American Heart Association. Heart-Check Meal Certification Program Nutrition Requirements. 2018. https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/company-collaboration/heart-check-certification/heart-check-meal-certification-program-foodservice/heart-check-meal-certification-program-nutrition-requirements .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). What We Eat in America, NHANES 2015–2016. 2017.

US Department of Health and Human Services. US Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8th ed. Washington, DC: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2015.

Appel LJ, Frohlich ED, Hall JE, Pearson TA, Sacco RL, Seals DR, et al. The importance of population-wide sodium reduction as a means to prevent cardiovascular disease and stroke: a call to action from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2011;123:1138–43.

World Health Organization. Sodium intake for adults and children. 2020.

European Commission Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Knowlege Gateway. Dietary salt/sodium. 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/health-knowledge-gateway/promotion-prevention/nutrition/salt .

Quader ZS, Zhao L, Gillespie C, Cogswell ME, Terry AL, Moshfegh A, et al. Sodium intake among persons aged >/=2 years - United States, 2013–2014. MMWR Morbidity Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:324–238.

Moran AJ, Ramirez M, Block JP. Consumer underestimation of sodium in fast food restaurant meals: Results from a cross-sectional observational study. Appetite. 2017;113:155–61.

New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygeine. New Sodium (Salt) Warning Rule: What Food Service Establishments Need to Know. 2016. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/cardio/sodium-warning-rule.pdf .

Byrd K, Almanza B, Ghiselli RF, Behnke C, Eicher-Miller HA. Adding sodium information to casual dining restaurant menus: Beneficial or detrimental for consumers? Appetite. 2018;125:474–85.

New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygeine. The Regulation to Phase Out Artificial Trans Fat In New York City Food Service Establishments

AB-97 Food facilities: trans fats., California Legislature (2008).

FDA. Food Additives & Ingredients - Final Determination Regarding Partially Hydrogenated Oils (Removing Trans Fat) [WebContent]. Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition; 2019. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/Food/IngredientsPackagingLabeling/FoodAdditivesIngredients/ucm449162.htm .

Angell SY, Cobb LK, Curtis CJ, Konty KJ, Silver LD. Change in trans fatty acid content of fast-food purchases associated with New York City’s restaurant regulation: a pre-post study. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:81–6.

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (2010).

Food and Drug Administration. Food Labeling; Nutrition Labeling of Standard Menu Items in Restaurants and Similar Retail Food Establishments. 2014. https://www.federalregister.gov/d/2014-27833 .

Krieger JW, Chan NL, Saelens BE, Ta ML, Solet D, Fleming DW. Menu labeling regulations and calories purchased at chain restaurants. Am J Prevent Med. 2013;44:595–604.

Finkelstein EA, Strombotne KL, Chan NL, Krieger J. Mandatory menu labeling in one fast-food chain in King County, Washington. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:122–7.

Namba A, Auchincloss A, Leonberg BL, Wootan MG. Exploratory analysis of fast-food chain restaurant menus before and after implementation of local calorie-labeling policies, 2005-2011. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E101.

Tandon PS, Zhou C, Chan NL, Lozano P, Couch SC, Glanz K, et al. The impact of menu labeling on fast-food purchases for children and parents. Am J Prevent Med. 2011;41:434–8.

Elbel B, Kersh R, Brescoll VL, Dixon LB. Calorie labeling and food choices: a first look at the effects on low-income people in New York City. Health Aff (Proj Hope). 2009;28:w1110–21.

Wellard-Cole L, Goldsbury D, Havill M, Hughes C, Watson WL, Dunford EK, et al. Monitoring the changes to the nutrient composition of fast foods following the introduction of menu labelling in New South Wales, Australia: an observational study. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21:1194–9.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene for the MenuStat data.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Health Policy & Management, Department of Health & Public Policy, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 624 N Broadway, Baltimore, MD, USA

Eleanore Alexander, Lainie Rutkow & Emma E. McGinty

Division of General Internal Medicine, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, 733 N Broadway, Baltimore, MD, 21205, USA

Kimberly A. Gudzune

Welch Center for Prevention, Epidemiology, and Clinical Research, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, 2024 E Monument St, Baltimore, MD, 21205, USA

Department of Health, Behavior and Society, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 624 N Broadway, Baltimore, MD, 21205, USA

Joanna E. Cohen

Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, 733 N Broadway, Baltimore, MD, 21205, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to the design of the study. EA led secondary data analysis and manuscript writing. EEM, LR, KG, and JEC contributed revisions to the manuscript and approved the final manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Eleanore Alexander .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This study was deemed Exempt by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Online appendix, rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Alexander, E., Rutkow, L., Gudzune, K.A. et al. Trends in the healthiness of U.S. fast food meals, 2008–2017. Eur J Clin Nutr 75 , 775–781 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-020-00788-z

Download citation

Received : 30 December 2019

Revised : 08 September 2020

Accepted : 13 October 2020

Published : 27 October 2020

Issue Date : May 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-020-00788-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

The Effect of Fast Food Restaurants on Obesity and Weight Gain

We investigate the health consequences of changes in the supply of fast food using the exact geographical location of fast food restaurants. Specifically, we ask how the supply of fast food affects the obesity rates of 3 million school children and the weight gain of over 3 million pregnant women. We find that among 9th grade children, a fast food restaurant within a tenth of a mile of a school is associated with at least a 5.2 percent increase in obesity rates. There is no discernable effect at .25 miles and at .5 miles. Among pregnant women, models with mother fixed effects indicate that a fast food restaurant within a half mile of her residence results in a 1.6 percent increase in the probability of gaining over 20 kilos, with a larger effect at .1 miles. The effect is significantly larger for African-American and less educated women. For both school children and mothers, the presence of non-fast food restaurants is uncorrelated with weight outcomes. Moreover, proximity to future fast food restaurants is uncorrelated with current obesity and weight gain, conditional on current proximity to fast food. The implied effects of fast-food on caloric intake are at least one order of magnitude larger for students than for mothers, consistent with smaller travel cost for adults.

The authors thank John Cawley, the editor, two anonymous referees and participants in seminars at the NBER Summer Institute, the 2009 AEA Meetings, the ASSA 2009 Meetings, the Federal Reserve Banks of New York and Chicago, the FTC, the New School, the Tinbergen Institute, UC Davis, the Rady School at UCSD, and Williams College for helpful comments. We thank Joshua Goodman, Cecilia Machado, Emilia Simeonova, Johannes Schmeider, and Xiaoyu Xia for excellent research assistance. We thank Glenn Copeland of the Michigan Dept. of Community Health, Katherine Hempstead and Matthew Weinberg of the New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services, and Rachelle Moore of the Texas Dept. of State Health Services for their help in accessing the data. The authors are solely responsible for the use that has been made of the data and for the contents of this article. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

MARC RIS BibTeΧ

Download Citation Data

- February 10, 2009

Non-Technical Summaries

- Do Fast Food Restaurants Contribute to Obesity? Author(s): Janet Currie Stefano DellaVigna Enrico Moretti Vikram Pathania Over the past thirty years, the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases in the U.S. has risen sharply. Since the early 1970s,...

Published Versions

Mentioned in the news, more from nber.

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Fast-food, everyday life and health: A qualitative study of 'chicken shops' in East London

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Social and Environmental Health Research, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, 15-17 Tavistock Place, WC1H 9SH, London, UK. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Department of Social and Environmental Health Research, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, 15-17 Tavistock Place, WC1H 9SH, London, UK. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 3 Department of Social and Environmental Health Research, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, 15-17 Tavistock Place, WC1H 9SH, London, UK. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 4 Department of Social and Environmental Health Research, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, 15-17 Tavistock Place, WC1H 9SH, London, UK. Electronic address: [email protected].

- PMID: 29807123

- PMCID: PMC6059357

- DOI: 10.1016/j.appet.2018.05.136

The higher prevalence of fast food outlets in deprived areas has been associated with the production and maintenance of geographical inequalities in diet. In the UK one type of fast food outlet - the 'chicken shop' - has been the focus of intense public health and media interest. Despite ongoing concerns and initiatives around regulating these establishments, the 'chicken shop' is both a commercially successful and ubiquitous feature of disadvantaged urban neighbourhoods. However, little is known about how they are perceived by local residents. We report data from a qualitative study of neighbourhood perceptions in a low SES urban setting. Narrative family interviews, go-along interviews and school video focus group workshops with 66 residents of East London were conducted over two waves. The topic of chicken shops was a prolific theme and a narrative analysis of these accounts revealed that local perceptions of chicken shops are complex and contradictory. Chicken shops were depicted as both potentially damaging for the health of local residents and, at the same time, as valued community spaces. This contradiction was discursively addressed in narrative via a series of rhetorical rebuttals that negated their potential to damage health on the grounds of concepts such as trust, choice, balance, food hygiene and compensatory physical activity. In some instances, chicken shops were described as 'healthy' and patronising them constructed as part of a healthy lifestyle. Chicken shops are embedded in the social fabric of neighbourhoods. Successful strategies to improve diet therefore requires context-sensitive environmental interventions.

Keywords: Chicken shops; East London; Fast food; Food environment; Health; Newham; Qualitative.

Copyright © 2018 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

PubMed Disclaimer

- Yonder: Chicken shops, bronchiectasis, fertility, and regrets. Rashid A. Rashid A. Br J Gen Pract. 2018 Sep;68(674):431. doi: 10.3399/bjgp18X698669. Br J Gen Pract. 2018. PMID: 30166386 Free PMC article. No abstract available.

Similar articles

- Associations between home and school neighbourhood food environments and adolescents' fast-food and sugar-sweetened beverage intakes: findings from the Olympic Regeneration in East London (ORiEL) Study. Shareck M, Lewis D, Smith NR, Clary C, Cummins S. Shareck M, et al. Public Health Nutr. 2018 Oct;21(15):2842-2851. doi: 10.1017/S1368980018001477. Epub 2018 Jul 2. Public Health Nutr. 2018. PMID: 29962364 Free PMC article.

- A qualitative study of independent fast food vendors near secondary schools in disadvantaged Scottish neighbourhoods. Estrade M, Dick S, Crawford F, Jepson R, Ellaway A, McNeill G. Estrade M, et al. BMC Public Health. 2014 Aug 4;14:793. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-793. BMC Public Health. 2014. PMID: 25092257 Free PMC article.

- Urban environment and dietary behaviours as perceived by residents living in socioeconomically diverse neighbourhoods: A qualitative study in a Mediterranean context. Rivera-Navarro J, Conde P, Díez J, Gutiérrez-Sastre M, González-Salgado I, Sandín M, Gittelsohn J, Franco M. Rivera-Navarro J, et al. Appetite. 2021 Feb 1;157:104983. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2020.104983. Epub 2020 Oct 9. Appetite. 2021. PMID: 33045303

- Correlates of English local government use of the planning system to regulate hot food takeaway outlets: a cross-sectional analysis. Keeble M, Adams J, White M, Summerbell C, Cummins S, Burgoine T. Keeble M, et al. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2019 Dec 9;16(1):127. doi: 10.1186/s12966-019-0884-4. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2019. PMID: 31818307 Free PMC article. Review.

- System resilience and neighbourhood action on social determinants of health inequalities: an English Case Study. Popay J, Kaloudis H, Heaton L, Barr B, Halliday E, Holt V, Khan K, Porroche-Escudero A, Ring A, Sadler G, Simpson G, Ward F, Wheeler P. Popay J, et al. Perspect Public Health. 2022 Jul;142(4):213-223. doi: 10.1177/17579139221106899. Epub 2022 Jul 8. Perspect Public Health. 2022. PMID: 35801904 Free PMC article. Review.

- Young people's views and experience of diet-related inequalities in England (UK): a qualitative study. Er V, Crowder M, Holding E, Woodrow N, Griffin N, Summerbell C, Egan M, Fairbrother H. Er V, et al. Health Promot Int. 2024 Aug 1;39(4):daae107. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daae107. Health Promot Int. 2024. PMID: 39175414 Free PMC article.

- Beyond individual responsibility: Exploring lay understandings of the contribution of environments on personal trajectories of obesity. Serrano-Fuentes N, Rogers A, Portillo MC. Serrano-Fuentes N, et al. PLoS One. 2024 May 8;19(5):e0302927. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0302927. eCollection 2024. PLoS One. 2024. PMID: 38718062 Free PMC article.

- A critical exploration of the diets of UK disadvantaged communities to inform food systems transformation: a scoping review of qualitative literature using a social practice theory lens. Hunt L, Pettinger C, Wagstaff C. Hunt L, et al. BMC Public Health. 2023 Oct 11;23(1):1970. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-16804-3. BMC Public Health. 2023. PMID: 37821837 Free PMC article. Review.

- The interplay between social and food environments on UK adolescents' food choices: implications for policy. Shaw S, Muir S, Strömmer S, Crozier S, Cooper C, Smith D, Barker M, Vogel C. Shaw S, et al. Health Promot Int. 2023 Aug 1;38(4):daad097. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daad097. Health Promot Int. 2023. PMID: 37647523 Free PMC article.

- Spatial Aspects of Health-Developing a Conceptual Framework. Augustin J, Andrees V, Walsh D, Reintjes R, Koller D. Augustin J, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Jan 19;20(3):1817. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20031817. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023. PMID: 36767185 Free PMC article.

- Birch L, Ventura A. Preventing childhood obesity: what works? International Journal of Obesity. 2009;33:S74–S81. - PubMed

- Boseley S. The chicken shop mile and how Britain got fat. The Guardian; London: 2016.

- Burgoine T, Forouhi NG, Griffin SJ, Brage S, Wareham NJ, Monsivais P. Does neighborhood fast-food outlet exposure amplify inequalities in diet and obesity? A cross-sectional study. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2016;103:1540–1547. - PMC - PubMed

- Cadwalladr C. The fried food joint that’s trying to tackle teenage obesity. The Guardian; London: 2015.

- Caraher M, Lloyd S, Mansfield M, Alp C, Brewster Z, Gresham J. Secondary school pupils’ food choices around schools in a London borough: Fast food and walls of crisps. Appetite. 2016;103:208–220. - PubMed

- Search in MeSH

Grants and funding

- WT_/Wellcome Trust/United Kingdom

- 09/3005/09/DH_/Department of Health/United Kingdom

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Elsevier Science

- Europe PubMed Central

- PubMed Central

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Home

- Article citations

- Biomedical & Life Sci.

- Business & Economics

- Chemistry & Materials Sci.

- Computer Sci. & Commun.

- Earth & Environmental Sci.

- Engineering

- Medicine & Healthcare

- Physics & Mathematics

- Social Sci. & Humanities

Journals by Subject

- Biomedical & Life Sciences

- Chemistry & Materials Science

- Computer Science & Communications

- Earth & Environmental Sciences

- Social Sciences & Humanities

- Paper Submission

- Information for Authors

- Peer-Review Resources

- Open Special Issues

- Open Access Statement

- Frequently Asked Questions

Publish with us

| +1 323-425-8868 | |

| +86 18163351462(WhatsApp) | |

| Paper Publishing WeChat |

About SCIRP

- Publication Fees

- For Authors

- Peer-Review Issues

- Special Issues

- Manuscript Tracking System

- Subscription

- Translation & Proofreading

- Volume & Issue

- Open Access

- Publication Ethics

- Preservation

- Privacy Policy

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.5(5); 2019 May

Fast food consumption and its associations with heart rate, blood pressure, cognitive function and quality of life. Pilot study

Mohammad alsabieh.

a College of Medicine, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Mohammad Alqahtani

Abdulaziz altamimi, abdullah albasha, alwaleed alsulaiman, abdullah alkhamshi, syed shahid habib, shahid bashir.

b Neuroscience Center, King Fahad Specialist Hospital Dammam, Dammam, Saudi Arabia

To investigate the relationship of fast food consumption with cognitive and metabolic function of adults (18–25 years old) in Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Materials and Method

This cross-sectional study was conducted at the College of Medicine at King Khalid University Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The conventionally recruited subjects underwent an evaluation that included demographic data, quality of life (wellness, stress, sleepiness, and physical activity), mini-mental status examination, and the frequency of fast food consumption. To investigate metabolic function, blood was drawn to evaluate serum HDL, LDL, cholesterol, and triglyceride levels. Cognitive function was assessed by the Cambridge neuropsychological test automated battery. The participants were divided into 2 groups based on fast food consumption: those who consumed fast food 3 times per week or less (Group 1) and those who consumed fast food more than 3 times per week (Group 2).

The mean diastolic blood pressure in Group 1 and Group 2 was 72 mmHg and 77 mmHg, respectively, a significant difference (p = 0.04). There was no significant difference for cognitive function and quality of life between the two groups. There was significant correlation of HDL with AST correct mean latency and the AST correct mean latency congruent (p = 0.02, p = 0.01, respectively) and TC with diastolic blood pressure (p = 0.003).

Conclusions

We concluded that fast food consumption has an effect on blood pressure but has no direct effect on cognition or quality of life.

1. Introduction

Fast food consumption has increased significantly worldwide. Fast food typically refers to food that is quickly prepared, rich in saturated fat, purchased from restaurants using precooked ingredients, and served in a packaged form [1] . Previous studies have shown that a high intake of sweetened beverages increases cardio-metabolic risk factors, obesity [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ], DM2 [ 6 , 7 , 8 ], hypertension [9] , and metabolic syndrome [ 8 , 10 ]. The rise in obesity rates in American adults (68.8%) currently classified as overweight or obese [11] link to increased intake of sugar-containing beverages [2] . The prevalence of DM2 in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is also increasing; among 6024 participants, diabetes mellitus was present in 1792 (30%) patients [12] . Studies have shown impaired cognitive functioning in DM2, and obesity [13] . Cognitive impairment in older age is neuropsychological marker of dementia [ 14 , 15 ]. It is worth mentioning that fast food consumptions is increasing among Saudis in different age groups for both genders [16] , as expected (Collison et al., 2010) found that the average fast food intake was 4.47 meal/week in different age groups, although girls consumed more fast food than boys [17] . Different populations based study showed different rate of food consumption/week [ 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ].

Fast food has many unpleasant health consequences. It negatively affects brain health by damaging regions relevant to memory tasks and by diminishing brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels [25] . This amplifies the risk of developing dementia and Alzheimer's disease later in life [26] . A high intake of Western food, characterized by high levels of saturated fat, was associated with increased serum total cholesterol (TC) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), with an 8% increase in the likelihood of having sustained high LDL-C [27] . In combination with a sedentary lifestyle, an increased prevalence has been noted of chronic non-communicable diseases, such as diabetes, heart disease, and cancer, which are estimated to account for 78% of all deaths (WHO, 2014). Thus, this diet is detrimental to the health and will aggravate existing lifestyle diseases [ 26 , 28 ]. The most common risk factor for developing coronary heart disease in Saudi patients is the consumption of a high-fat diet which contains high levels of LDL-C [ 29 , 30 ].

Several cross-sectional studies have found significant associations between poor nutritional status and behavioral disturbances [ 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ], worse cognitive status [31] , and more impaired functioning in adult daily living activities [ 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 ]. While these studies have demonstrated an association between nutritional status and aged population, very limited have examined the association of cognitive function with food addiction in young population and the majority of the studies have been conducted in clinical samples. Considering the lack of studies conducted in Saudi Arabia or in the Middle East regarding fast food consumption and its effects on cognitive function, we hypothesized that increased consumption of fast food would impair cognitive function, metabolic functions, and quality of life in young adults.

2. Materials & methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in the Department of Physiology, King Khalid University Hospital (KKUH), Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The conventionally recruited subjects underwent evaluation of demographic data, quality of life, mini-mental status examination, and the frequency of fast food consumption. Subjects also completed the Cambridge neuropsychological test automated battery (CANTAB).

2.1. Participants

A non-probability convenience sampling technique was used to recruit subjects. Our inclusion and exclusion criteria were designed to isolate the effect of fast food consumption and to exclude other possible causes of cognitive impairment. All subjects were healthy with no neurological or psychiatric disorders and were taking no medications. We included 60 healthy Saudi young adults ranging in age from 19 to 23 years old (mean age: 20.8 years). Judging by the average fast food consumption of young Saudi adults which is estimated to be 4.47 meal per weak we thought to categorize our subjects into two groups below and above average [17] . The sample was divided into two groups according to their fast food consumption. Group 1 included those who consumed fast food 3 times per week or less (n = 35; men = 30, women = 5), and the participants' mean age was 21.23 years. Group 2 included those who consumed fast food more than 3 times per week (n = 25; men = 21, women = 4). Demographic data are presented in Table 1 . This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures were approved by the institutional review board of KKUH. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Demographic table for two groups.

| Group 1 n=35 | Group 2 n=25 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | % | No | % | |

| 30 | 85.7% | 21 | 84% | |

| 5 | 4.3% | 4 | 16% | |

| 4 | 11.42% | 2 | 8% | |

| 31 | 88.58% | 23 | 92% | |

| 3 | 8.57% | 1 | 4% | |

| 32 | 91.43% | 24 | 96% | |

| 11 | 31.4% | 12 | 48% | |

| 16 | 45.73% | 6 | 24% | |

| 8 | 22.87% | 7 | 28% | |

2.2. Procedure and assessment

2.2.1. demographic.

Data questionnaire was designed to assess the socioeconomic and lifestyle characteristics including smoking history, living situation, marital status, and medical history.

2.2.2. Body composition

Body composition analysis was obtained via bioelectrical impedance analysis with a commercially available body analyzer (TANITA, USA). The subjects were asked to wipe the soles of their feet with a wet tissue and then to stand on the electrodes of the machine. Data was then recorded.

2.3. Cognitive function

Cognitive function was evaluated using the MMSE and CANTAB tests. The MMSE is one of the most widely used tools for quantitative assessment of cognitive function. The test consists of 11 questions assessing various cognitive functions, including 2 questions on orientation, 1 on registration, 1 on memory, 5 on language, 1 on attention and calculation, and 1 on visual construction. The test has a maximum score of 30, with scores below 23 being indicative of cognitive impairment.

2.3.1. Delayed matching sample test

The delayed matching to sample simultaneously assesses visual matching ability and short-term visual recognition memory of patterns. The participant was shown a complex, abstract, visual pattern followed by four similar patterns after a brief delay. The participant selected the pattern that exactly matched the original pattern.

2.3.2. Attention switch task (AST) test

The AST tests the participant's ability to switch attention between the location of the arrow on the screen and its direction. This test was designed to measure top-down cognitive control processes involving the prefrontal cortex. The test shows an arrow that can point to either the right or left side of the screen and may appear on either the right or left side of the screen. Some trials displayed congruent stimuli (e.g., an arrow on the left side of the screen pointing to the left), whereas other trials displayed incongruent stimuli that required a greater cognitive demand (e.g., an arrow on the left side of the screen pointing to the right). The detail description of the task can be assessed from the website ( www.cantab.org ).

2.3.3. Intra-extra dimensional set shift test