A quick note about our cookies

We use cookies so we can give you the best website experience possible and to provide us with anonymous data so we can improve our marketing efforts. Read our cookie policy and privacy policy.

Login to your account

New here? Sign up in seconds!

Use social account

Or login with an email

Create an account

Already have an account? Login here

Or sign up with an email

We’re uploading new templates every week

We’d like to send you infrequent emails with brief updates to let you know of the latest free templates. Is that okay?

Reset your Password

Please enter the email you registered with and we will send you a link to reset your password!

Check your email!

We’ve just sent you a link to . Please follow instructions from our email.

- Most Popular Templates

- Corporate & Business Models

- Data (Tables, Graphs & Charts)

- Organization & Planning

- Text Slides

- Our Presentation Services

Get your own design team

Tailored packages for corporates & teams

Parenting PowerPoint Presentation

Number of slides: 10

Parenting doesn’t come with a manual. There are many questions parents have about raising children, and while it is true that they learn how to be better parents on the go, as a qualified expert you can give them a hand. The Parents & Kids Presentation Template is ideal for psychologists, counselors, educators, and pediatricians who are looking to give parents and families professional advice on how to raise happy kids in a modern world.

- About this template

- How to edit

- Custom Design Services

Free Parenting PowerPoint Presentation Template

Understanding kids .

Kids grow up fast and each stage of childhood comes with different needs and challenges. How do parents cope with all these changes in such a short amount of time? In this slide, you will be able to show the phases every child goes through and give the parents tools to understand their children better.

Kids and The Environment

It’s important to teach the next generation how to take care of the environment. Schools everywhere are implementing programs and including lessons to teach children more about this topic but the first step must be taken at home. Use this slide to explain good environmental practices parents can do with their kids at home.

Kids Behavior Slides

When kids are little, it is difficult for them to express their feelings. Because of that, many kids scream, cry or act rude when there is not an apparent reason. Part of understanding children's behavior is paying attention to these attitudes, even the slightest change communicates something. With this slide, you can teach parents how to keep a record of the behavior of their little kids and identify when it’s time to go with a specialist.

Kids hobbies

It is important to support the interests of kids. They are exploring the world and finding out what they like and dislike.

Illustrations

The Parents & Kids Presentation Template comes with amazing vector illustrations of families spending time together. These are the best visuals you will find to talk about parenting.

Is your company celebrating family day? Organize a workshop where employees who have kids can share their experiences as parents.

FIND OUT MORE ABOUT OUR CUSTOM DESIGN SERVICES

Todd Speranzo

VP of Marketing at Avella

"24Slides helps us get PowerPoints on-brand, and improve overall design in a timeframe that is often “overnight”. Leveraging the time zone change and their deep understanding of PowerPoint, our Marketing team has a partner in 24Slides that allows us to focus purely on slide content, leaving all of the design work to 24Slides."

Gretchen Ponts

Strata Research

"The key to the success with working with 24Slides has been the designers’ ability to revamp basic information on a slide into a dynamic yet clean and clear visual presentation coupled with the speed in which they do so. We do not work in an environment where time is on our side and the visual presentation is everything. In those regards, 24Slides has been invaluable."

"After training and testing, 24Slides quickly learnt how to implement our CVI, deliver at a high quality and provide a dedicated design team that always tries to accommodate our wishes in terms of design and deadlines."

What's included in Keynote Template?

I want this template customized class="mobile-none"for my needs!

69 beautifully designed slides 67 icons included PowerPoint and Keynote ready 16:9 full HD class="mobile-none"resolution

Check out other similar templates

Science Icon Template Pack

General PowerPoint Icons Template

Dark themed 30 Slide Template Pack

Generic Mobile Pack Templates

Got any suggestions?

We want to hear from you! Send us a message and help improve Slidesgo

Top searches

Trending searches

35 templates

biochemistry

38 templates

hispanic heritage month

21 templates

travel itinerary

46 templates

mid autumn festival

18 templates

63 templates

Positive Parenting Infographics

It seems that you like this template, free google slides theme, powerpoint template, and canva presentation template.

Being a parent of a kid should be defined in the dictionaries as "regarding work, the hardest in the world". How you raise your kids will have an influence on them as they later become adults. Talk about positive parenting and unravel the secrets behind being a great parent! Our infographics, which are totally editable, will add value to your slideshows, as they help you represent data that otherwise would need a lot of verbal explaining. They come with illustrations (from Storyset!) of parents with their kids.

Features of these infographics

- 100% editable and easy to modify

- 31 different infographics to boost your presentations

- Include icons and Flaticon’s extension for further customization

- Designed to be used in Google Slides, Canva, and Microsoft PowerPoint and Keynote

- 16:9 widescreen format suitable for all types of screens

- Include information about how to edit and customize your infographics

How can I use the infographics?

Am I free to use the templates?

How to attribute the infographics?

Attribution required If you are a free user, you must attribute Slidesgo by keeping the slide where the credits appear. How to attribute?

Register for free and start downloading now

Related posts on our blog.

How to Add, Duplicate, Move, Delete or Hide Slides in Google Slides

How to Change Layouts in PowerPoint

How to Change the Slide Size in Google Slides

Related presentations.

Premium template

Unlock this template and gain unlimited access

What is Positive Parenting? 33 Examples and Benefits

And while most of us strive to be great parents, we may also find ourselves confused and frustrated by the seemingly endless challenges of parenthood.

As both parents of toddlers and teenagers can attest, such challenges are evident across all developmental stages.

But there is good news— numerous research-supported tools and strategies are now available for parents. These resources provide a wealth of information for common parenting challenges (i.e., bedtime issues, picky eating, tantrums, behavior problems, risk-taking, etc.); as well as the various learning lessons that are simply part of growing up (i.e., starting school, being respectful, making friends, being responsible, making good choices, etc.).

With its focus on happiness, resilience and positive youth development ; the field of positive psychology is particularly pertinent to discussions of effective parenting. Thus, whether you are a parent who’s trying to dodge potential problems; or you are already pulling your hair out— you’ve come to the right place.

This article provides a highly comprehensive compilation of evidence-based positive parenting techniques. These ideas and strategies will cover a range of developmental periods, challenges, and situations. More specifically, drawing from a rich and robust collection of research, we will address exactly what positive parenting means; its many benefits; when and how to use it; and its usefulness for specific issues and age-groups.

This article also contains many useful examples, positive parenting tips, activities, programs, videos, books , podcasts – and so much more. By learning from and applying these positive parenting resources; parents will become the kind of parents they’ve always wanted to be: Confident, Optimistic, and even Joyful.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Parenting Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients identify opportunities to implement positive parenting practices and support healthy child development.

This Article Contains:

What is positive parenting, a look at the research, how can it encourage personal development and self growth in a child, how old must the child be, what are the benefits, 12 examples of positive parenting in action, positive parenting styles, a look at positive discipline, positive parenting with toddlers and preschoolers, how to best address sibling rivalry, positive parenting with teenagers, positive parenting through divorce, a take-home message.

Before providing a definition of positive parenting, let’s take a step back and consider what we mean by “parents.” While a great deal of parenting research has focused on the role of mothers; children’s psychosocial well-being is influenced by all individuals involved in their upbringing.

Such caregivers might include biological and adoptive parents, foster parents, single parents, step-parents, older siblings, and other relatives and non-relatives who play a meaningful role in a child’s life. In other words, the term “parent” applies to an array of individuals whose presence impacts the health and well-being of children (Juffer, Bakermans-Kranenburg & van Ijzendoorn, 2008).

Thus, any time the terms “parent” or “caregiver” are used herein; they apply to any individuals who share a consistent relationship with a child, as well as an interest in his/her well-being (Seay, Freysteinson & McFarlane, 2014).

Fortunately, parenting research has moved away from a deficit or risk factor model towards a more positive focus on predictors of positive outcomes (e.g., protective factors ). Positive parenting exemplifies this approach by seeking to promote the parenting behaviors that are most essential for fostering positive youth development (Rodrigo, Almeida, Spiel, & Koops, 2012).

Several researchers have proposed definitions of positive parenting, such as Seay and colleagues (2014), who reviewed 120 pertinent articles. They came up with the following universal definition:

Positive parenting is the continual relationship of a parent(s) and a child or children that includes caring, teaching, leading, communicating, and providing for the needs of a child consistently and unconditionally.

(Seay et al., 2014, p. 207).

The Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe (2006) similarly defined positive parenting as “ … nurturing, empowering, nonviolent… ” and which “ provides recognition and guidance which involves setting of boundaries to enable the full development of the child ’’ (in Rodrigo et al., 2012, p. 4). These definitions, combined with the positive parenting literature, suggest the following about positive parenting:

- It involves Guiding

- It involves Leading

- It involves Teaching

- It is Caring

- It is Empowering

- It is Nurturing

- It is Sensitive to the Child’s Needs

- It is Consistent

- It is Always Non-violent

- It provides Regular Open Communication

- It provides Affection

- It provides Emotional Security

- It provides Emotional Warmth

- It provides Unconditional Love

- It recognizes the Positive

- It respects the Child’s Developmental Stage

- It rewards Accomplishments

- It sets Boundaries

- It shows Empathy for the Child’s Feelings

- It supports the Child’s Best Interests

Along with these qualities, Godfrey (2019) proposes that the underlying assumption of positive parenting is that “… all children are born good, are altruistic and desire to do the right thing …” (positiveparenting.com).

Godfrey further adds that the objective of positive parenting is to teach discipline in a way that builds a child’s self-esteem and supports a mutually respectful parent-child relationship without breaking the child’s spirit (2019). These authors reveal an overall picture of positive parenting as warm, thoughtful and loving— but not permissive.

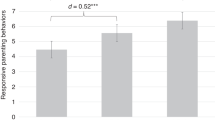

There is plenty of research supporting the short- and long-term effects of positive parenting on adaptive child outcomes. To begin with, work by the Positive Parenting Research Team ( PPRT ) from the University of Southern Mississippi (Nicholson, 2019) is involved in various studies aimed at examining the impact of positive parenting.

- The following are included among the team’s research topics:

- Relationships between positive parenting and academic success;

- Positive parenting as a predictor of protective behavioral strategies;

- Parenting style and emotional health; maternal hardiness, coping and social support in parents of chronically ill children, etc.

The PPRT ultimately seeks to promote positive parenting behaviors within families.

In their seven-year longitudinal study; Pettit, Bates and Dodge (1997) examined the influence of supportive parenting among parents of pre-kindergartners. Supportive parenting was defined as involving mother‐to‐child warmth, proactive teaching, inductive discipline, and positive involvement. Researchers contrasted this parenting approach with a less supportive, more harsh parenting style.

Supportive parenting was associated with more positive school adjustment and fewer behavior problems when the children were in sixth grade. Moreover, supportive parenting actually mitigated the negative impact of familial risk factors (i.e., socioeconomic disadvantage, family stress, and single parenthood) on children’s subsequent behavioral problems (Pettit et al., 2006).

Researchers at the Gottman Institute also investigated the impact of positive parenting by developing a 5-step ‘emotion coaching’ program designed to build children’s confidence and to promote healthy intellectual and psychosocial growth.

Gottman’s five steps for parents include:

- awareness of emotions;

- connecting with your child;

- listening to your child;

- naming emotions; and

- finding solutions (Gottman, 2019).

Gottman has reported that children of “emotional coaches” benefit from a more a positive developmental trajectory relative to kids without emotional coaches. Moreover, an evaluation of emotional coaching by Bath Spa University found several positive outcomes for families trained in emotional coachings, such as parental reports of a 79% improvement in children’s positive behaviors and well-being (Bath Spa University, 2016).

Overall, research has indicated that positive parenting is related to various aspects of healthy child development (many more examples of evidence supporting the benefits are positive parenting are described further in this article). Such outcomes are neither fleeting nor temporary; and will continue well beyond childhood.

Another way of thinking about the role of positive parenting is in terms of resilience. When children—including those who begin life with significant disadvantages— experience positive and supportive parenting, they are far more likely to thrive.

It is in this way that positive parenting minimizes health and opportunity disparities by armoring children with large stores of emotional resilience (Brooks, 2005; Brooks & Goldstein, 2001). And since we know positive parenting works; what parent wouldn’t want to learn how to use it and thereby give his/her child the best shot at a healthy and happy life?

Download 3 Free Positive Parenting Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients with tools to improve parenting styles and support healthy child development.

Download 3 Free Positive Parenting Exercises Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

There are various mechanisms through which positive parenting promotes a child’s prosocial development.

For example, Eisenberg, Zhou, and Spinrad et al. (2005) suggest that positive parenting impacts children’s temperament by enhancing emotion regulation (e.g., “effortful control” enabling children to focus attention in a way that promotes emotion modulation and expression).

The authors reported a significant link between parental warmth and positive expressivity on children’s long-term emotion regulation. This ability to use effortful control was found to predict reduced externalizing problems years later when children were adolescents (Eisenbert et al., 2005).

Along with emotion regulation, there are many other ways in which positive parenting encourages a child’s positive development and self-growth.

Here are some examples:

- Teaching and leading promote children’s confidence and provides them with the tools needed to make good choices.

- Positive communication promotes children’s social and problem-solving skills while enhancing relationship quality with caregivers and peers.

- Warm and democratic parenting enhances children’s self-esteem and confidence.

- Parental supervision promotes prosocial peer bonding and positive youth outcomes.

- Autonomy-promoting parenting supports creativity, empowerment, and self-determination.

- Supportive and optimistic parenting fosters children’s belief in themselves and the future.

- Providing recognition for desirable behaviors increases children’s self-efficacy and the likelihood of engaging in prosocial, healthy behaviors.

- Providing boundaries and consequences teaches children accountability and responsibility.

Generally speaking, there are many aspects of positive parenting that nurture children’s self-esteem; creativity; belief in the future; ability to get along with others; and sense of mastery over their environment.

Warm, loving and supportive parents feed a child’s inner spirit while empowering him/her with the knowledge and tools necessary to approach life as a fully capable individual.

5 Expert tips no parent should miss – Goalcast

The need for positive parenting begins – well, at the beginning. The attachment literature has consistently indicated that babies under one year of age benefit from positive parenting. More specifically, a secure attachment between infants and mothers is related to numerous positive developmental outcomes (i.e., self-esteem, trust, social competence, etc.; Juffer, Bakermans-Kranenburg & van Ijzendoorn, 2008).

The quality of the mother-child attachment is believed to be a function of parental sensitivity (e.g., mothers who accurately perceive and quickly respond to their babies’ needs; Juffer et al., 2008)— which is certainly a key indicator of positive parenting practices in their earliest form.

Not only is a secure mother-child attachment related to early positive developmental outcomes, but more recent attachment research also indicates long-term increases in social self-efficacy among girls with secure attachments to their fathers (Coleman, 2003).

There are even ways in which positive parenting benefits a child or family as soon as the parents learn of a pregnancy or adoption (i.e., see the subsequent ‘sibling rivalry’ section). Therefore, it cannot be stressed enough: Positive parenting begins as early as possible.

There is empirical evidence for numerous benefits of positive parenting, which cover all developmental stages from infancy to late adolescence. The following table provides a list of many such examples:

| Positive Parenting Style, Behavior, or Intervention | Benefit | Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Autonomy-supportive Parenting | Better school adjustment among children Increased motivation among infants Higher internalization among toddlers Better psychosocial functioning among adolescents | Joussemet, Landry & Koestner, 2008 |

| Reduced depressive symptoms among adolescents Increased self-esteem among adolescents | Duineveld, Parker, Ryan, Ciarrochi, & Salmela-Aro, 2017 | |

| Increased optimism among children | Hasan & Power, 2002 | |

| Sensitive/Responsive Parenting that Promotes a Secure Parent-Child Attachment | Increased self-esteem among older adolescents | Liable-Gustavo & Roesch, 2004 |

| Increased social self-efficacy among adolescents | Coleman, 2003 | |

| Multiple positive outcomes among children, such as secure parental attachments, and better cognitive and social development | Juffer, Bakermans-Kranenburg & van Ijzendoorn, 2008 | |

| Interventions that Enhance Positive Parenting Practices | Improved attachment security among toddlers Improved school adjustment among children | Forgatch & DeGarmo, 1999 |

| Increased cognitive and social outcomes among preschoolers | Smith, Landry, & Swank, 2000 | |

| Numerous reductions in problem behaviors and increases in competences among children and adolescents— such as self-esteem, coping efficacy, educational goals, and job aspirations | Sandler, Wolchik, Tein, & Winslow, 2015 | |

| Reduced behavior problems among children Lower dysfunctional parenting styles Higher sense of parenting competence | Sanders, Calam, Durand, Liversidge, & Carmont, 2008 | |

| Long-term reductions in behavior problems among children | de Graaf, Speetjens, Smit, Wolff, & Tavecchio, 2008 | |

| Decreased family conflict and stress; decreased behavioral problems and conduct disorders among children; improved family cohesion, communication, and organization; improved resilience among children and parents | Kumpfer & Alvarado, 1998 | |

| Reduced problem behaviors and increased positive development among children | Knox, Burkhard, & Cromly, 2013 | |

| Responsive Parenting (i.e., involves tolerating and working through emotions) | Increased emotion regulation associated with various positive outcomes among children and adolescents | See studies cited in Bornstein 2002 |

| Involved Parenting (i.e., uses rules and guidelines, and involves kids in decision-making) | Increased compliance and self-regulation among children | See studies cited in Bornstein 2002 |

| Developmental Parenting as Characterized by Parental Affection, Teaching & Encouragement | Numerous positive outcomes among children and adolescents; such as increased compliance, greater cognitive abilities, more school readiness, less negativity, more willingness to try new things, better cognitive and social development, better language development, better conversational skills, and less antisocial behavior | See studies cited in Roggman, Boyce, & Innocenti, 2008 |

| Supportive Families | Increased resilience among children and adolescents | Newman & Blackburn, 2002 |

| Parental Attachment, Positive Family Climate & Other Positive Parenting Factors | Increased social skills among adolescents | Engels, Deković, & Meeus, 2002 |

| Warm, Democratic, and Firm Parenting Style (e.g., Authoritative) | Increased school achievement among adolescents | Steinberg, Elmen, & Mounts, 1989 |

| General positive youth development (i.e., less risky behaviors, improved school success, better job prospects, etc.) among adolescents | Sandler, Ingram, & Wolchik, et al., 2015 | |

| Family Supervision and Monitoring; Effective Communication of Expectations and Family Values/Norms; and Regular Positive Family Time | Improved ability to resist negative peer influences among adolescents | Lochman, 2000 |

The evidence clearly supports a relationship between positive parenting approaches and a large variety of prosocial parent and child outcomes. Therefore, practitioners have developed and implemented a range of programs aimed at promoting positive parenting practices.

Here are some noteworthy examples; including those which target specific risk factors, as well as those with a more preventative focus:

- Parent’s Circle program (Pearson & Anderson, 2001): Recognizing that positive parenting begins EARLY, this program helped parents of infants in the neonatal intensive care unit to enhance their parenting skills in order to better parent their fragile newborns.

- The Home Visiting Program (Ammaniti, Speranza, & Tambelli, et al., 2006): Also focused on babies, this program aimed to increase parental sensitivity in order to improve secure mother-infant attachments. In doing so, psychologists visited high-risk mothers at their homes in order to improve parental sensitivity to their infants’ signals.

- The Early Head Start Home-based Program (Roggman, Boyce, & Cook, 2009): This home-based program also focused on promoting parent-child attachment. Parents in semirural areas received weekly home-based visits from a family educator who taught them positive strategies aimed at promoting healthy parent-child interactions and engagement in children’s activities.

- American Psychological Association’s ACT Raising Safe Kids (RSK) program (Knox, Burkhard, & Cromly, 2013): The goal of this program was to improve parents’ positive parenting knowledge and skills by teaching nonviolent discipline, anger management, social problem‐solving skills, and other techniques intended to protect children from aggression and violence.

- New Beginnings Program (Wolchik, Sandler, Weiss, & Winslow, 2007): This empirically-based 10-session program was designed to teach positive parenting skills to families experiencing divorce or separation. Parents learned how to nurture positive and warm relationships with kids, use effective discipline, and protect their children from divorce-related conflict. The underlying goal of the New Beginnings Program was to promote child resilience during this difficult time.

- Family Bereavement Program (Sandler, Wolchik, Ayers, Tein, & Luecken, 2013): This intervention was aimed at promoting resilience in parents and children experiencing extreme adversity: The death of a parent. This 10-meeting supportive group environment helped bereaved parents learn a number of resilience-promoting parenting skills (i.e., active listening, using effective rules, supporting children’s coping, strengthening family bonds, and using adequate self-care).

- The Positive Parent (Suárez, Rodríguez, & López, 2016): This Spanish online program was aimed at enhancing positive parenting by helping parents to learn about child development and alternative child-rearing techniques; to become more aware, creative and independent in terms of parenting practices; to establish supportive connections with other parents; and to feel more competent and satisfied with their parenting.

- Healthy Families Alaska Programs (Calderaa, Burrellb, & Rodriguez, 2007): The objective of this home visiting program was to promote positive parenting and healthy child development outcomes in Alaska. Paraprofessionals worked with parents to improve positive parenting attitudes, parent-child interactions, child development knowledge, and home environment quality.

- The Strengthening Families Program (Kumpfer & Alvarado, 1998): This primary prevention program has been widely used to teach parents a large array of positive parenting practices. Following family systems and cognitive-behavioral philosophies, the program has taught parenting skills such as engagement in positive interactions with children, positive communication, effective discipline, rewarding positive behaviors, and the use of family meetings to promote organization. The program’s overall goal was to enhance child and family protective factors; to promote children’s resilience, and to improve children’s social and life skills.

- Incredible Years Program (Webster-Stratton& Reid, 2013): This program refers to a widely implemented and evaluated group-based intervention designed to reduce emotional problems and aggression among children, and to improve their social and emotional competence. Parent groups received 12-20 weekly group sessions focused on nurturing relationships, using positive discipline, promoting school readiness and academic skills, reducing conduct problems, and increasing other aspects of children’s healthy psychosocial development. This program has also been used for children with ADHD.

- Evidence-based Positive Parenting Programs Implemented in Spain (Ministers of the Council of Europe, in Rodrigo et al., 2012): In a special issue of Psychosocial Intervention, multiple evaluation studies of positive parenting programs delivered across Spain are presented. Among the programs included are those delivered in groups, at home, and online; each of which is aimed at positive parenting support services. This issue provides an informative resource for understanding which parents most benefited from various types of evidence-based programs aimed at promoting positive parenting among parents attending family support services.

- Triple P Positive Parenting Program (Sanders, 2008): This program, which will be described in more detail in a subsequent post, is a highly comprehensive parenting program with the objective of providing parents of high-risk children with the knowledge, confidence, and skills needed to promote healthy psychological health and adjustment in their children. While these programs are multifaceted, an overarching focus of the Triple P programs is to improve children’s self-regulation.

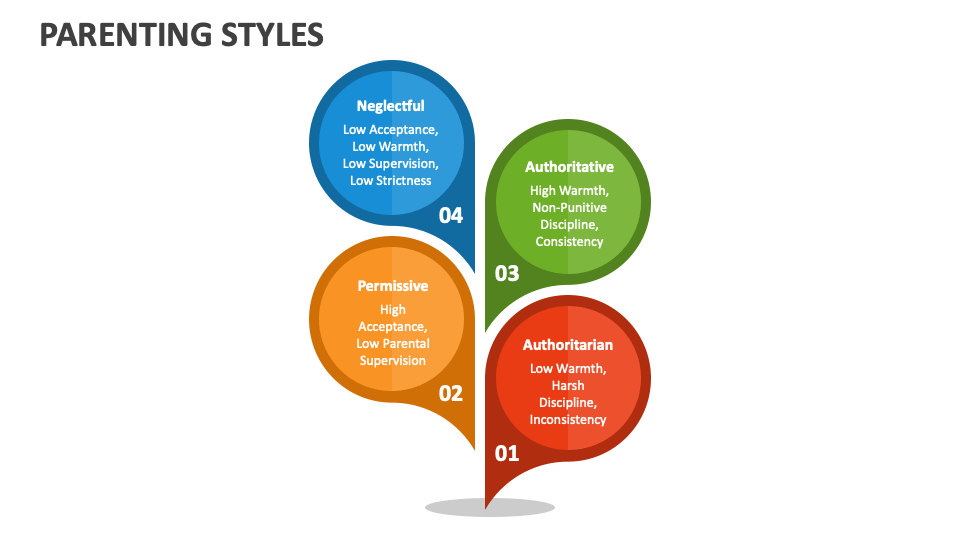

A reoccurring theme in the positive parenting literature is that a warm, yet firm parenting style is linked to numerous positive youth outcomes. This style is termed ‘authoritative’ and it is conceptualized as a parenting approach that includes a good balance of the following parenting qualities: assertive, but not intrusive; demanding, but responsive; supportive in terms of discipline, but not punitive (Baumrind, 1991).

Along with an authoritative parenting style, a developmental parenting style is also believed to support positive child outcomes (Roggman et al., 2008).

Developmental parenting is a positive parenting style that promotes positive child development by providing affection (i.e., through positive expressions of warmth toward the child); responsiveness (i.e., by attending to a child’s cues); encouragement (i.e., by supporting a child’s capabilities and interests); and teaching (i.e., by using play and conversation to support a child’s cognitive development (Roggman & Innocenti, 2009).

Developmental parenting clearly shares several commonalities with authoritative parenting, and both represent positive parenting approaches.

Overall, by taking a good look at positive parenting strategies that work for raising healthy, happy kids; it is evident that positive parenting styles encourage a child’s autonomy by:

- Supporting exploration and involvement in decision-making

- Paying attention and responding to a child’s needs

- Using effective communication

- Attending to a child’s emotional expression and control

- Rewarding and encouraging positive behaviors

- Providing clear rules and expectations

- Applying consistent consequences for behaviors

- Providing adequate supervision and monitoring

- Acting as a positive role model

- Making positive family experiences a priority

In a nutshell, positive parents support a child’s healthy growth and inner spirit by being loving, supportive, firm, consistent, and involved. Such parents go beyond communicating their expectations, but practice what they preach by being positive role models for their children to emulate.

4 Things you must say to your kids daily – Live on Purpose TV

The term ‘discipline’ often has a negative, purely punitive connotation. However, ‘discipline’ is actually defined as “training that corrects, molds, or perfects the mental faculties or moral character” (Merriam-Webster, 2019).

This definition is instructive, as it reminds us that as parents, we are not disciplinarians, but rather teachers. And as our children’s teachers, our goal is to respectfully show them choices for behaviors and to positively reinforce adaptive behaviors.

Positive discipline again harkens back to authoritative parenting because it should be administered in a way that is firm and loving at the same time. Importantly, positive discipline is never violent, aggressive or critical; it is not punitive.

Relevant: Examples of Positive Punishment & Negative Reinforcement

Physical punishment (i.e., spanking) is ineffective for changing behaviors in the long-term and has a number of detrimental consequences on children (Gershoff, 2013). Indeed, the objective of positive discipline is to “teach and train. Punishment (inflicting pain/purposeful injury) is unnecessary and counter-productive” (Kersey, 2006, p. 1).

Nelsen (2006) describes a sense of belonging as a primary goal of all people; a goal that is not achieved through punishment. In fact, she describes the four negative consequences of punishment on children (e.g., “the four R’s”) as resentment toward parents; revenge that may be plotted in order to get back at parents; rebellion against parents, such as through even more excessive behaviors; and retreat, that may involve becoming sneaky and/or experiencing a loss of self-esteem (Nelsen, 2006).

She provides the following five criteria for positive discipline (which are available on her positive discipline website ):

- Is both kind and firm

- Promotes a child’s sense of belonging and significance

- Works long-term (note: punishment may have an immediate impact, but this is short-lived)

- Teaches valuable social and life skills (i.e., problem-solving, social skills, self-soothing, etc.)

- Helps children develop a sense that they are capable individuals

In her comprehensive and helpful book for parents: Positive Discipline , Nelsen (2006) also describes a number of key aspects of positive discipline, such as being non-violent, respectful, and grounded in developmental principles; teaching children self-respect, empathy, and self-efficacy; and promoting a positive relationship between parent and child.

Stated another way, “ respecting children teaches them that even the smallest, most powerless, most vulnerable person deserves respect, and that is a lesson our world desperately needs to learn ” (LR Knost, lovelivegrow.com).

Since we know that positive discipline does not involve the use of punishment; the next obvious questions become “Just what exactly does it involve?”

This question is undoubtedly urgent for parents who feel like their child is working diligently toward driving them mad. While we will discuss some of the more typical frustrations that parents regularly encounter later in the article, Kersey (2006) provides parents with a wonderful and comprehensive resource in her publication entitled “101 positive principles of discipline.”

Here are her top ten principles:

- Demonstrate Respect Principle : Treat the child in the same respectful way you would like to be treated.

- Make a Big Deal Principle : Use positive reinforcement in meaningful ways for desired behaviors. Reward such behaviors with praise, affection, appreciation, privileges, etc.

- Incompatible Alternative Principle : Provide the child with a behavior to substitute for the undesirable one, such as playing a game rather than watching tv.

- Choice Principle : Provide the child with two choices for positive behaviors so that he/she feels a sense of empowerment. For example, you might say “would you rather take your bath before or after your brush your teeth?”

- When/Then – Abuse it/Lose it Principle : Ensure that rewards are lost when rules are broken. For example, you might say “After you clean your room, you can play outside” (which means that a child who does not clean his/her room, will not get to play outside. Period.)

- Connect Before You Correct Principle : Ensure that the child feels loved and cared for before behavioral problems are attended to.

- Validation Principle : Validate the child’s feelings. For example, you might say “I know you are sad about losing your sleepover tonight and I understand”.

- Good Head on Your Shoulders Principle : Ensure that the child hears the equivalent of “you have a good head on your shoulders” in order to feel capable, empowered and responsible for his/her choices. This is especially important for teenagers.

- Belonging and Significance Principle : Ensure that your child feels important and as if he/she belongs. For example, remind your child that he/she is really good at helping in the kitchen and that the family needs this help in order to have dinner.

- Timer Says it’s Time Principle : Set a timer to help children make transitions. This helps kids to know what’s expected of them and may also involve giving them a choice in terms of the amount of time. For example, you might say “Do you need 15 or 20 minutes to get dressed?” Make sure to let the child know that the time is set.

The reader is encouraged to check-out Kersey’s 101 positive discipline principles, as they contain an enormous amount of useful and effective approaches for parents; along with principles that reflect many everyday examples (e.g., Babysitter Principle; Apology Principle; Have Fun Together Principle; Talk About Them Positively to Others Principle; Whisper Principle; Write a Contract Principle; and so much more).

This section has provided many helpful positive discipline ideas for a myriad of parenting situations and challenges. Positive discipline (which will be expounded on later sections of in the article: i.e., ‘positive parenting with toddlers and preschoolers,’ ‘temper tantrums,’ ‘techniques to use at bedtime,’ etc.) is an effective discipline approach that promotes loving parent-child relationships, as well as producing productive, respectful, and happy children.

The notion of parenting a toddler can frighten even the most tough-minded among us. This probably isn’t helped by terms such as ‘terrible two’s,’ and jokes like “ Having a two-year-old is kind of like having a blender, but you don’t have a top for it ” (Jerry Seinfeld, goodreads.com).

Sure, toddlers and preschoolers get a bad rap; but they do sometimes seem like tiny drunken creatures who topple everything in their path. Not to mention their tremendous noise and energy, mood swings, and growing need for independence.

While their lack of coordination and communication skills can be endearing and often hilarious; they are also quite capable of leaving their parents in a frenzied state of frustration. For example, let’s consider the situation below.

The Grocery Store Blow-out

In this relatable example, a dad and his cranky 3-year-old find themselves in a long line at a grocery store. The child decides she’s had enough shopping and proceeds to throw each item out of the cart while emitting a blood-curdling scream.

The father, who may really need to get the shopping done, is likely to shrivel and turn crimson as his fellow shoppers glare and whisper about his “obnoxious child” or “bad parenting.” He, of course, tells her to stop; perhaps by asking her nicely, or trying to reason with her.

When this doesn’t’ work, he might switch his method to commanding, pleading, threatening, negotiating, or anything else he can think of in his desperation. But she is out of control and beyond reason. The father wants an immediate end to the humiliation; but he may not realize that some quick fixes intended to placate his child, will only make his life worse in the long run.

So, what is he to do?

Before going into specific solutions for this situation, it is essential that parents understand this developmental stage. There are reasons for the child’s aggravating behaviors; reasons that are biologically programmed to ensure survival.

For example, kids aged two-to-three are beginning to understand that there are a lot of things that seem scary in the world. As such, they may become anxious about a variety of situations; like strangers, bad dreams, extreme weather, creepy images, doctor and dentist offices, monsters, certain animals, slivers or other minor medical issues, etc.

While these childhood fears make life more difficult for parents (i.e., when a child won’t stay in his/her room at night due to monsters and darkness, or when a child makes an enormous fuss when left with a babysitter), they are actually an indicator of maturity (Durant, 2016).

The child is reacting in a way that supports positive development by fearing and avoiding perceived dangers. While fear of monsters does not reflect a truly dangerous situation, avoidance of individuals who appear mean or aggressive is certainly in the child’s best interest.

Similarly, fear of strangers is an innate protective mechanism that prompts children to stay close to those adults who keep them healthy and safe. And some strangers indeed should be feared. Although a challenge for parents, young children who overestimate dangers with consistent false-positives are employing their survival instincts.

In her book Positive Discipline (which is free online and includes worksheets for parents), Durant (2016) notes the importance of respecting a child’s fears and not punishing her/him for them, as well as talking to the child in a way that shows empathy and helps him/her to verbalize feelings. Durant proposes that one of the keys of effective discipline is “… to see short-term challenges as opportunities to work toward your long-term goals” (2016, p. 21).

With this objective in mind, any steps a parent takes when dealing with a frightened or misbehaving child should always be taken with consideration of their potential long-term impact. Long-term goals, which Durant describes as “the heart of parenting” may be hard to think about when a child is challenging and a frustrated parent simply wants the behavior to stop.

However, punishing types of behaviors such as yelling, are not likely to be in-line with long-term parenting goals. By visualizing their preschooler as a high school student or even an adult, it can help parents to ensure that their immediate responses are in-line with the kind, peaceful and responsible person they wish to see in 15 years or so. Durant (2016) provides several examples of long-term parenting goals, such as:

- Maintaining a quality relationship with the parent

- Taking responsibility for actions

- Being respectful of others

- Knowing right from wrong

- Making wise decisions

- Being honest, loyal and trustworthy

Related: Examples of Positive Reinforcement in the Classroom

Grocery Store Blow-out Solutions

Long-term parenting goals are highly relevant to the maddening grocery store example. If the dad only thinks about the short-term goal of making his daughter’s behavior stop embarrassing him at the store, he might decide to tell her she can have a candy bar if she is quiet and stops throwing items from the cart.

This way, he might reason, he can finish his shopping quickly and without humiliation. Sure, this might work as far as getting the child to behave on that day— at that moment; BUT here are some likely consequences:

- Next time they go shopping, she will do this again in order to receive the candy reward.

- Pretty much every time they go shopping, she will do the same thing; and the value of the reward is likely to escalate as she gets tired of the candy.

- She will learn that this behavior can get her rewards in all sorts of places beyond the grocery store, thus making her exhausted parents afraid to take her anywhere.

Moreover, the message she receives from the candy tactic will not reinforce the qualities the father likely wants to see in his daughter over time, such as:

- Being respectful of her parents

- Being respectful of others around her

- Being respectful of others’ property

- Being responsible for her behavior

- Being courteous and considerate

- Being helpful

- Having good manners

- Having good social skills

Therefore, the father might instead deal with this situation by calmly telling her that she needs to stop or she will get a time-out. The time-out can take place somewhere in the store that is not reinforcing for her, such as a quiet corner with no people around (e.g., no audience). Or they can go sit in the car.

If the store is especially crowded, the dad might also ask the clerk to place his cart in a safe place and/or save his place in line until he returns (which he/she will likely be inclined to do if it will get the child to be quiet). After a brief time-out, he should give his daughter a hug and let her know the rules for the remainder of the shopping trip, as well as the consequences of not following them.

In some cases, it might be better for the parent to simply leave the store without the groceries and go home. He won’t have completed his shopping, but that will be a small price for having a child who learns a good lesson on how to behave.

Very importantly, however; if he does take her home, this absolutely cannot be done in a way that is rewarding (i.e., she gets to go home and play, watch tv, or anything else she enjoys). She will need a time-out immediately upon arriving home, as well as perhaps the message that dinner won’t be her favorite tonight since the shopping was not done.

This is not meant to be punitive or sarcastic, more of a natural consequence for her to learn from (e.g., “If I act-out at the store, we won’t have my favorite foods in the house”). In fact, even though he may not feel like it, the father needs to speak to his daughter in a kind and loving way.

Regardless of whether the consequence is in the store or at home, the dad absolutely must follow-through consistently. If he doesn’t, he will teach her that sometimes she can misbehave and still get what she wants; this is a pattern of reinforcement that is really difficult to break.

Of course, the father cannot leave the store each time she misbehaves, as he won’t get anything done and he’s also giving her too much control. Thus, he should prepare in advance for future shopping trips by making her aware of the shopping rules, expectations for her behavior, and the consequences if she breaks them.

The father should be specific about such things, as “I expect you to be good at the store” is not clear. Saying something more like “The rules for shopping are that you need to talk in your quiet voice, listen to daddy, sit still in the cart, help daddy give the items to the clerk, etc.” The dad is also encouraged to only take her shopping when she is most likely to behave (i.e., when well-rested, well-fed, not upset about something else, etc.).

He might also give her something to do while shopping, such as by bringing her favorite book or helping to put items in the cart. Giving his daughter choices will also help her feel a sense of control (i.e., “You can either help put the items in the cart or you can help give them to the clerk”).

And, finally, the little girl should be rewarded for her polite shopping behavior with a great deal of praise (i.e., “You were a very good girl at the store today. You really helped Daddy and I enjoyed spending time with you”).

He might also reward her with a special experience (i.e., “You were so helpful at the store, that we saved enough time to go the park later” or “You were such a great helper today; can you also help daddy make dinner?”). Of course, the reward should not consist of food, since that can lead to various other problems.

There are many more positive parenting tips for this and other difficult parenting scenarios throughout this article, as well as numerous helpful learning resources. In the meantime, it is always wise to remember that your toddler or preschooler does not act the way he/she does in order to torture you— it’s not personal.

There are always underlying reasons for these behaviors. Just keep your cool, plan-ahead, think about your long-term goals, and remember that your adorable little monster will only be this age for a brief time.

Related: Parenting Children with Positive Reinforcement (Examples + Charts)

World’s Largest Positive Psychology Resource

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises , activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!” — Emiliya Zhivotovskaya , Flourishing Center CEO

Siblings, whether biological; adopted; full or half stepsiblings; often pick at each other endlessly. Arguments between siblings are a normal part of life. However, sometimes the degree of animosity between siblings (e.g., sibling rivalry) can get out of control and interfere with the quality of the relationship. Not to mention creating misery for parents. Plus, there are negative long-term consequences of problematic sibling relationships, such as deviant behavior among older children and teens (Moser & Jacob, 2002).

Sibling rivalry is often complicated, as it is affected by a range of family variables, such as family size, parent-child interactions, parental relationships, children’s genders, birth order, and personality—among others. And it starts really early. Sometimes, as soon as a child realizes a baby brother or sister is on the way, emotions begin to run high. Fortunately, parents have a great opportunity to prepare their children from the start.

For example, the parent can foster a healthy sibling relationship by engaging in open communication about becoming a big brother or sister early on. This should be done in a way that is exciting and supports the child’s new role as the older sibling. Parents can support bonding by allowing the child to feel the baby kick or view ultrasound pictures. They can solicit their child’s help in decorating the baby’s room.

For some families, their newborn baby may be premature or have other medical problems that require time in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). In this situation, which can be quite stressful for siblings, parents should talk to the older child about what’s happening. Parents might also provide the child with updates on the baby’s progress, prepare the child for visits to the NICU, have the child draw a picture to leave with the baby, make a scrapbook for the baby, and set aside plenty of time with the older child (Beavis, 2007).

If the new child is going to be adopted, it is also important to encourage a connection. For example, along with explaining how the adoption will work, the child can be involved in the exciting aspects of the process once it is confirmed. In the case of an older child or international adoption, there are special things parents can do as well.

For example, if a child is in an orphanage, the sibling can help pick-out little gifts to send ahead of time (i.e., a stuffed animal, soft blanket or clothing). Having the child draw a picture and/or write a letter to the new sibling is another way to enhance the relationship. Adopting an older child will require particular preparation; as the new sibling will arrive with his/her own fears, traits, memories, and experiences that will certainly come into play.

There are a number of children’s books designed to help parents prepare their children for a new sibling, such as You Were the First (MacLachlan, 2013), My Sister Is a Monster : Funny Story on Big Brother and New Baby Sister How He Sees Her (Green, 2018), and Look-Look : The New Baby (Mayer, 2001).

There are also children’s books that help prepare children for adopted siblings, with some that are even more focused on the type of adoption. Here are a few examples: Seeds of Love : For Brothers and Sisters of International Adoption (Ebejer Petertyl & Chambers, 1997), A Sister for Matthew : A Story About Adoption (Kennedy, 2006), and Emma’s Yucky Brother (Little, 2002).

Along with the above tips, Amy McCready (2019) provides some excellent suggestions for ending sibling rivalry, these include:

- Avoid Labeling Children: by labeling children in ways such as “the social one,” “the great student,” “the athlete,” “the baby” etc., parents intensify comparisons, as well as one child’s belief that he/she does not possess the same positive qualities as the other one (i.e., “if he’s the ‘brainy one,’ I must be the ‘dumb one,’”).

- Arrange for Attention: Make sure each child has plenty of regular intentional attention so that they will be less inclined to fight for it.

- Prepare for Peace: McCready describes several ways to teach conflict resolution skills that help to avoid further issues between siblings.

- Stay out of Squabbles: Unless absolutely necessary (i.e., during a physical fight), it is best to stay out of squabbles. In doing so, the parent is not reinforcing the disagreement, while also enabling the children to work out solutions together.

- Calm the Conflict: If you must intervene, it is best to help the children problem-solve the situation without judgment or taking sides.

- Put them All in the Same Boat: McCready suggests that all children involved in the conflict receive the same consequence, which teaches them that they each will benefit from getting along.

These and other useful tips and resources are available on McCready’s Positive Parenting Solutions website . Luckily, by being thoughtful and preparing ahead of time, parents can avoid excessive competition between children and promote meaningful lifelong sibling bonds.

Before discussing positive parenting with teenagers, it is important to remember one key fact: Teens still need and want their parents’ support, affection, and guidance— even if it doesn’t seem like it. Just as with younger kids, parental figures are essential for helping adolescents overcome difficult struggles (Wolin, Desetta & Hefner, 2016).

Indeed, by fostering a sense of mastery and internal locus of control, adults help to empower a teen’s sense of personal responsibility and control over the future (Blaustein & Kinniburgh, 2018). In fact, the presence of nurturing adults who truly listen has been reported among emotionally resilient teens (Wolin et al., 2016).

Positive parenting practices such as quality communication, parental monitoring, and authoritative parenting style also have been found to predict fewer risky behaviors among adolescents (DeVore & Ginsburg, 2005).

As parents of teens know, there are many challenges involved in parenting during this developmental period. Adolescents often find themselves confused about where they fit in the area between adulthood and childhood. They may desire independence, yet lack the maturity and knowledge to execute it safely. They are often frustrated by their bodily changes, acne and mood swings.

Teens may be overwhelmed by school, as well as pressures from parents and peers. Teens may feel bad about themselves and even become anxious or depressed as they try to navigate the various stressors they face.

Many of these difficulties, which certainly need attention from parents, may also make conversations difficult. Parents may feel confused as to how much freedom versus protectiveness is appropriate. The Love and Logic approach (Cline & Faye, 2006) provides some terrific ways for parents to raise responsible, well-adjusted teens.

The authors’ approach for parents involves two fundamental concepts: “Love [which] means giving your teens opportunities to be responsible and empowering them to make their own decisions.” And “Logic [which] means allowing them to live with the natural consequences of their mistakes-and showing empathy for the pain, disappointment, and frustration they’ll experience” (Foster, Cline, & Faye, 2019, hopelbc.com, p. 1).

Just as with young children, the Love and Logic method is a warm and loving way to prepare teens for the future while maintaining a quality relationship with parents.

Another positive parenting approach that is particularly applicable to adolescents is the Teen Triple P Program (Ralph & Sanders, 2004). Triple P (which will be described in a subsequent post) is tailored toward teens and involves teaching parents a variety of skills aimed at increasing their own knowledge and confidence.

The program also promotes various prosocial qualities in teens such as social competence, health, and resourcefulness; such that they will be able to avoid engaging in problem behaviors (e.g., substance use, risky sex, delinquency, Bulimia, etc.). This approach enables parents to replace harsh discipline styles for those that are more nurturing, without being permissive. It aims to minimize parent-teen conflict while providing teens with the tools and ability to make healthy choices (Ralph & Sanders, 2004).

Parents of teens (or future teens) often shudder when considering the dangers and temptations to which their children may be exposed. With a focus specifically on substance use, the Partnership for Drug-free Kids website offers a great deal of information for parents who are either dealing with teen drug use or are doing their best to prevent it.

For example, several suggestions for lowering the probability that a teen will use substances include:

- knowing your teen’s friends;

- being a positive role model in terms of your own coping mechanisms and use of alcohol and medication;

- being aware of your child’s level of risk for substance use;

- providing your teen with substance use information;

- supervising and monitoring your teen;

- setting boundaries;

- communicating openly about substance use; and

- building a supportive and warm relationship with your teen (Partnership for Drug-free Kids; PDK, 2014).

These suggestions are discussed in more detail on the following PDF : Parenting Practices: Help Reduce the Chances Your Child will Develop a Drug or Alcohol Problem (PDK, 2014). By employing these and other positive parenting techniques, you are helping your teenager to become a respectful, well-adjusted and productive member of society.

Divorce has become so common that dealing with it in the best possible way for kids is of vital importance to parents everywhere.

Parental divorce/separation represents a highly stressful experience for children that can have both immediate and long-term negative consequences.

Children of divorce are at increased risk for mental health, emotional, behavioral, and relationship problems (Department of Justice, Government of Canada, 2015).

There is, however, variability in how divorce affects children; with some adverse consequences being temporary, and others continuing well into adulthood. Since we know that divorce does not impact all children equally, the key question becomes: What are the qualities that are most effective for helping children to cope with parental divorce?

There are differences in children’s temperament and other aspects of personality, as well as family demographics, that affect their ability to cope with divorce. But, for present purposes, let’s focus on the aspects of the divorce itself since this is the area parents have the most power to change.

Importantly, the detrimental impact of divorce on kids typically begins well before the actual divorce (Amato, 2000). Thus, it may not be the divorce per se that represents the child risk factor; but rather, the parents’ relationship conflicts and how they are handled. For divorced/divorcing parents, this information is encouraging—as there are things you can do to help your children (and you) remain resilient despite this difficult experience.

Parental Conflict and Alienation

There are several divorce-related qualities that make it more difficult for children to adapt to divorce, such as parental hostility and poor cooperation between parents (Amato, 2000); and interpersonal conflict between parents along with continued litigation (Goodman, Bonds, & Sandler, et al., 2005).

Parents dealing with divorce need to make a special effort not to expose their children to conflicts between parents, legal and money related issues, and general animosity. The latter point merits further discussion, as parents often have a difficult time not badmouthing each other in front of (or even directly to) their kids. It is this act of turning a child against a parent that ultimately serves to turn a child against himself (Baker & Ben-Ami, 2011).

Badmouthing the other divorced parent is an alienation strategy, given its aim to alienate the other parent from the child. Such alienation involves any number of criticisms of the other parent in front of the child. This may even include qualities that aren’t necessarily negative, but which can be depicted as such for the sake of enhancing alienation (Baker & Ben-Ami, 2011).

Baker and Ben-Ami (2011) note that parental alienation tactics hurt children by sending the message that the badmouthed parent does not love the child. Also, the child may feel that, because their badmouthed parent is flawed; that he/she is similarly damaged. When a child receives a message of being unlovable or flawed, this negatively affects his/her self-esteem, mood, relationships, and other areas of life ( Baker & Ben-Ami, 2011 ).

An excellent resource for preventing parental alienation is Divorce Poison : How to Protect Your Family from Bad-mouthing and Brainwashing (Warshak, 2010).

Warshak describes how one parent’s criticism of the other may have a highly detrimental impact on the targeted parent’s relationship with his/her child. And such badmouthing absolutely hurts the child. Badmouthed parents who fail to deal with the situation appropriately are at risk of losing the respect of their kids and even contact altogether. Warshak provides effective solutions for bad-mouthed parents to use during difficult situations, such as:

- How to react when you find out about the badmouthing

- What to do if your kids refuse to see you

- How to respond to false accusations

- How to insulate kids from bad-mouthing effects

Reasons that parents attempt to manipulate children, as well as behaviors often exhibited by children who have become alienated from one parent, are also described (Warshak, 2010). This book, as well as additional resources subsequently listed, provides hope and solutions for parents who are dealing with the pain of divorce.

Importantly, there are ways to support children in emerging from divorce without long-term negative consequences (i.e., by protecting them from parental animosity). It is in this way that parents can “enable their children to maintain love and respect for two parents who no longer love, and may not respect, each other” (Warshak, 2004-2013, warshak.com).

Positive parenting is an effective style of raising kids that is suitable for pretty much all types of parents and children. This article contains a rich and extensive collection of positive parenting research and resources; with the goal of arming caregivers with the tools to prevent or tackle a multitude of potential challenges. And, of course, to foster wellness and healthy development in children.

Here are the article’s key takeaways:

- Parents are never alone. Whatever the problem or degree of frustration, there is a whole community of parents who have faced the same issues. Not to mention a ton of positive parenting experts with effective solutions.

- Positive parenting begins early. Positive parenting truly starts the moment a person realizes he/she is going to become a parent since even the planning that goes into preparing for a child’s arrival will have an impact.

- Positive parenting applies to all developmental periods. With a positive parenting approach, raising toddlers and teenagers need not be terrible nor terrifying. Positive parenting promotes effective, joyful parenting of kids of all ages.

- Positive parents raise their children in a way that empowers them to reach their full potential as resilient and fulfilled individuals. Positive parents are warm, caring, loving and nurturing— and so much more: They are teachers, leaders, and positive role models. They are consistent and clear about expectations. They know what their kids and teens are doing. They encourage and reinforce positive behaviors. They make family experiences a priority. They support their children’s autonomy and individuality. They love their children unconditionally. They engage in regular, open dialogues with their children. They are affectionate, empathetic, and supportive. They understand that their teenagers still need them.

- Positive discipline is an effective, evidence-based approach that is neither punitive nor permissive. Positive discipline is performed in a loving way without anger, threats, yelling, or punishment. It involves clear rules, expectations, and consequences for behavior; and consistent follow-through. It is in alignment with parents’ long-term parenting goals.

- Positive parenting is backed by empirical evidence supporting its many benefits. Positive parenting promotes children’s self-esteem, emotional expression, self-efficacy, sense of belonging, social and decision-making skills, and belief in themselves. Positive parenting fosters secure attachments and quality relationships with parents; school adjustment and achievement; reduced behavior problems, depressive symptoms, and risk behaviors; and positive youth development in general. The outcomes associated with positive parenting are long-term and often permanent.

- Positive parenting is applicable to a vast array of challenges. Positive parenting applies to everyday challenges, as well as more frustrating and even severe issues. Positive parenting has been effectively used for dealing with temper tantrums, bedtime and eating issues, and sibling rivalry; as well as difficulties associated with divorce, ADHD, family stressors, teen pressures, and risk-taking—and much more.

- Positive parenting solutions are both abundant and accessible. Because positive parenting experts have tackled so many parenting issues, available resources are plentiful. Along with the many tips and suggestions contained in this article; there is a whole online library of positive parenting-related activities, workbooks, books, videos, courses, articles, and podcasts that cover a broad range of parenting topics.

Considering the many positive parenting solutions and resources currently available, parents can approach their role as teachers, leaders, and positive role models with confidence and optimism. And, ultimately, by consistently applying positive parenting strategies; parents will experience a deep and meaningful connection with their children that will last a lifetime. ?

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Parenting Exercises for free .

- Alshugairi, N., & Lekovic Ezzeldine, M. (2017). Positive parenting in the Muslim home . Irvine, CA: Izza Publishing.

- Altiero, J. (2006). No more stinking thinking: A workbook for teaching children positive thinking . London, United Kingdome: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Amato, P. (2000). The consequences of divorce for adults and children. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62 (4), 1269-1287.

- Amit Ray. Goodreads (2019). Retrieved from https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/tag/girl-child

- Ammaniti M., Speranza A., Tambelli R., Muscetta, S., Lucarelli, L., Vismara, L., Odorisio, E., Cimino, S. (2006). A prevention and promotion intervention program in the field of mother-infant relationship. Infant Mental Health Journal, 27 :70-90.

- Asa Don Brown. Goodreads (2019). Retrieved from https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/tag/girl-child

- Author Unknown. The Quote Garden (1998-2019). Retrieved from http://quotegarden.com/

- Baker, A. & Ben-Ami, N. (2011). To turn a child against a parent is to turn a child against himself: The direct and indirect effects of exposure to parental alienation strategies on self-esteem and well-being. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 52 (7), 472–489.

- Bath Spa University (2016). Somerset Emotion Coaching Project. Retrieved from https://www.ehcap.co.uk/content/sites/ehcap/uploads/NewsDocuments/302/Emotion-Coaching-Full-Report-May-2016-FINAL.PDF

- Baumrind, D. (1991). The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. Journal of Early Adolescence, 11 (1), 56-95.

- Beavis, A. (2007). What about brothers and sisters? Helping siblings cope with a new baby brother or sister in the NICU. Infant, 3 (6), 239-242.

- Benjamin Spock. Goodreads (2019). Retrieved from https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/tag/girl-child

- Bill Ayers. Goodreads (2019). Retrieved from https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/tag/girl-child

- Bornstein, M. (2002). Emotion regulation: Handbook of parenting . Mahwah, New Jersey London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

- Brooks R.B. (2005) The power of parenting. In: Goldstein S., Brooks R.B. (eds) Handbook of resilience in children . Springer, Boston, MA.

- Brooks, R., & Goldstein, S. (2001). Raising resilient children: Fostering strength, hope, and optimism in your child . New York: Contemporary Books.

- Bruni, O., Violani, C., Luchetti, A., Miano, S. Verrillo, E., Di Brina, O., Valente, D. (2004). The sleep knowledge of pediatricians and child neuropsychiatrists. Sleep and Hypnosis, 6 (3):130-138.

- Calderaa, D., Burrellb, L., Rodriguezb, K., Shea Crowneb, S., Rohdec, C., Dugganc, A. (2007). Impact of a statewide home visiting program on parenting and on child health and development. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31 (8), 829-852.

- Carter, C. (2017). Positive discipline: 2-in-1 guide on positive parenting and toddler discipline . North Charleston, SC: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- Centers for Disease Control (2014). Positive parenting tips. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/childdevelopment/positiveparenting/

- Cline, F. & Fay, J. (2006). Parenting with love and logic: Teaching children responsibility . Colorado Springs, CO: NavPress.

- Cline, F., Fay, J., & Cline, F. (2006). Parenting teens with love and logic: Preparing adolescents for responsible adulthood . Colorado Springs, CO: Piñon Press.

- Cline, F., Fay, J., & Cline, F. (2019). Parenting Teens with Love & Logic . Retrieved from http://hopelbc.com/parenting%20teens%20with%20love%20and%20logic.pdf

- Coleman, P. (2003). Perceptions of parent‐child attachment, social self‐efficacy, and peer relationships in middle childhood. Infant and Child Development, 12 (4), 351-356.

- David, O. & DiGiuseppe, R. (2016). The Rational Positive Parenting Program . Cham, Heidelberg, New York, Dordrecht, London: Springer.

- de Graaf, I., Speetjens, P., & Smit, F., de Wolff, M., & Tavecchio, L. (2008). Effectiveness of The Triple P Positive Parenting Program on behavioral problems in children: A meta-analysis. Behavior Modification, 32 (5), 714–735.

- Department of Justice, Government of Canada (2015). The effects of divorce on children: a selected literature review. Retrieved from https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/fl-lf/divorce/wd98_2-dt98_2/toc-tdm.html

- DeVore, E. & Ginsburg, K. (2005). The protective effects of good parenting on adolescents. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 17 (4), 460-465.

- Duineveld, J., Parker, P., Ryan, R., Ciarrochi, J., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2017). The link between perceived maternal and paternal autonomy support and adolescent well-being across three major educational transitions. Developmental Psychology, 53 (10), 1978-1994.

- Durand, M. & Hieneman, M. (2008). Helping parents with challenging children: Positive family intervention parent workbook (programs that work). Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

- Durant, J. (2016). Positive discipline in everyday parenting. Retrieved from http://www.cheo.on.ca/uploads/advocacy/JS_Positive_Discipline_English_4th_edition.pdf

- Eanes, R. (2015). The newbie’s guide to positive parenting: Second edition. SC: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- Eanes, R. (2016). Positive parenting: an essential guide (the positive parent series). New York, NY: Penguin Random House, LLC.

- Eanes, R. (2018). The positive parenting workbook: An interactive guide for strengthening emotional connection (The Positive Parent Series). New York, NY: Random House, LLC.

- Eanes, R. (2019). The gift of a happy mother: Letting go of perfection and embracing everyday joy. Los Angeles, CA: TarcherPerigee.

- Ebejer Petertyl, M., & Chambers, J. (1997). Seeds of love: For brothers and sisters of international adoption . Grand Rapids, MI: Folio One Pub.

- Eisenberg, N., Zhou, Q., Spinrad, T. L., Valiente, C., Fabes, R. A., & Liew, J. (2005). Relations among positive parenting, children’s effortful control, and externalizing problems: A three-wave longitudinal study. Child Development, 76 (5), 1055–1071.

- Engels, R., Dekovic, M., & Meeus, W. (2002). Parenting practices, social skills and peer relationships in adolescence. Social Behavior and Personality, 30 (1), 3-17.

- Fay, J. (2019). What Is Parenting with Love and Logic? Retrieved from http://www.hopelbc.com/parenting%20with%20love%20and%20logic.pdf

- Ferber, R. (2006). Solve your child’s sleep problems: New, revised, and expanded edition . New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, Inc.

- Forgatch, M., & DeGarmo, D. (1999). Parenting through change: An effective prevention program for single mothers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67 (5), 711-724.

- Franklin D. Roosevelt. Goodreads (2019). Retrieved from https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/tag/girl-child

- Gary Smalley. Azquotes (2019). Retrieved from https://www.azquotes.com/

- Gershoff, E. (2013). Spanking and child development: We know enough now to stop hitting our children. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/cdep.12038

- Godfrey, D. (2019). Retrieved from https://positiveparenting.com/

- Goodman, M., Bonds, D., Sandler, I., & Braver, S. (2005). Parent psychoeducational programs and reducing the negative effects of interparental conflict following divorce. Family Court Review, 42 (2), 263–279.

- Gottman, J. (2019). The Gottman Institute: A research-based approach to relationships. Retrieved from https://www.gottman.com/parents/

- Green, A. (2018). My sister is a monster: Funny story on big brother and new baby sister how he sees her; sibling book for children. New York, NY: Schwartz & Wade.

- Halloran, J. (2016). Coping skills for kids workbook: Over 75 coping strategies to help kids deal with stress, anxiety and anger workbook. Retrieved from https://copingskillsforkids.com/workbook

- Hasan, N., & Power, T. G. (2002). Optimism and pessimism in children: A study of parenting correlates. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 26 (2), 185–191.

- Janet Lansbury. Love Live Grow (2018). Retrieved from https://lovelivegrow.com/

- Jesse Jackson. The Quote Garden (1998-2019). Retrieved from http://quotegarden.com/

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Azquotes (2019). Retrieved from https://www.azquotes.com/

- Johnson, M. (2009). Positive parenting with a plan paperback . Anchorage, AK: Publications Consultants.

- Joseph, G. (2019). Nine guided mindfulness meditations to help children go to sleep. Mindfulness Habits Team. Retrieved from https://www.audible.com/pd/Bedtime-Meditations-for-Kids-Audiobook/B07MGKHPWP

- Joussemet, M., Landry, R., & Koestner, R. (2008). A self-determination theory perspective on parenting. Canadian Psychology, 49 (3),194-200.

- Juffer F., Bakermans-Kranenburg M. & Van IJzendoorn M. (2008). Promoting positive parenting: An attachment-based intervention . New York: U.S.A.: Lawrence Erlbaum/Taylor & Francis.

- Karapetian, M., & McGrath, A. (2017). Conquer negative thinking for teens: A workbook to break the nine thought habits that are holding you back . Oakland, CA: Instant Help Books.

- Kennedy, P. (2006). A Sister for Matthew: A story about adoption . Nashville, TN: Ideals Publications.

- Kersey, K. (2006). The 101 Positive Principles of Discipline . Retrieved from https://ww2.odu.edu/~kkersey/101s/101principles.shtml

- Knox, M., Burkhard, K., & Cromly, A. (2013). Supporting positive parenting in community health centers: The Act Raising Safe Kids Program. Journal of Community Psychology, 41 (4), 395-407.

- Kumpfer, K. L., and Alvarado, R. (1998). Effective family strengthening interventions . Juvenile Justice Bulletin. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.strengtheningfamiliesprogram.org/about.html

- Liable, D., Gustavo, C., & Roesch, S. (2004). Pathways to self-esteem in late adolescence: The role of parent and peer attachment, empathy, and social behaviors. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1314&context=psychfacpub

- Little J. (2002). Emma’s yucky brother. New York, NY: Harper Trophy.

- LR Knost. Love Live Grow (2018). Retrieved from https://lovelivegrow.com/

- MacLachlan, P. (2013). You were the first. Boston. MA: Little, Brown Books for Young Readers.

- Markham, L. (2018). Peaceful parent, happy kids workbook: Using mindfulness and connection to raise resilient, joyful children and rediscover your love of parenting . Eau Claire, WI: PESI, Inc.

- Mathew L Jacobson. Love Live Grow (2018). Retrieved from https://lovelivegrow.com/

- Maya Angelou. Goodreads (2019). Retrieved from https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/tag/girl-child

- Mayer, M. (2001). Look-look: The new baby. New York, NY: Random House Books for Young Readers.