- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Life in ancient Egypt

- The king and ideology: administration, art, and writing

- Sources, calendars, and chronology

- The recovery and study of ancient Egypt

- Predynastic Egypt

- The 1st dynasty (c. 2900–c. 2730 bce )

- The 2nd dynasty (c. 2730–c. 2590 bce )

- The 3rd dynasty (c. 2592–c. 2544 bce )

- The 4th dynasty (c. 2543–c. 2436 bce )

- The 5th dynasty (c. 2435–c. 2306 bce )

- The 6th dynasty (c. 2305–c. 2118 bce )

- The 7th and 8th dynasties (c. 2150–c. 2118 bce )

- The 9th dynasty (c. 2118–c. 2080 bce )

- The 10th (c. 2080–c. 1980 bce ) and 11th (c. 2080–c. 1940 bce ) dynasties

- The 12th dynasty (c. 1939–c. 1760 bce )

- The 13th dynasty (c. 1759–c. 1630 bce ) and 14th dynasty (c. 1759–c. 1530 bce )

- The 15th (c. 1630–c. 1530 bce ) through 17th (c. 1630–c. 1540 bce ) dynasties

- The end of the Second Intermediate Period

- Amenhotep I

- Thutmose I and Thutmose II

- Hatshepsut and Thutmose III

- Amenhotep II

- Thutmose IV

- Foreign influences during the early 18th dynasty

- Amenhotep III

- Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten)

- The aftermath of Amarna

- Ay and Horemheb

- Ramses I and Seti I

- Last years of the 19th dynasty

- The early 20th dynasty: Setnakht and Ramses III

- The later Ramesside kings

- The 21st dynasty

- Libyan rule: the 22nd and 23rd dynasties

- The 24th and 25th dynasties

- The Late period (664–332 bce )

- The 27th dynasty

- The 28th, 29th, and 30th dynasties

- The second Persian period

- The Macedonian conquest

- The Ptolemaic dynasty

- The Ptolemies (305–145 bce )

- Dynastic strife and decline (145–30 bce )

- Administration

- Egypt as a province of Rome

- Administration and economy under Rome

- Society, religion, and culture

- Egypt’s role in the Byzantine Empire

- Byzantine government of Egypt

- The advance of Christianity

By what other term are the kings of Egypt called?

- Why is Tutankhamun significant?

- How old was Tutankhamun when he ascended to the throne?

- What did Tutankhamun accomplish during his reign?

- How did Tutankhamun die?

ancient Egypt

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Australian Museum - Ancient Egyptian Timeline

- The History Files - Ancient Egypt

- USHistory.org - Ancient Egypt

- Ancient Origins - Top 15 Interesting Facts About Ancient Egypt That You May Not Know

- Khan Academy - Ancient Egypt, an introduction

- Humanities LibreTexts - Ancient Egypt

- Smarthistory - The world of ancient Egypt

- PBS LearningMedia - How the Ancient Egyptian Pyramids Were Built

- World History Encyclopedia - Ancient Egypt

- Livescience - Ancient Egypt: History, dynasties, religion and writing

- ancient Egypt - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- ancient Egypt - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Egyptian kings are commonly called pharaohs, following the usage of the Bible. The term pharaoh is derived from the Egyptian per ʿaa (“great estate”) and to the designation of the royal palace as an institution. This term was used increasingly from about 1400 BCE as a way of referring to the living king.

What were the two types of writing in ancient Egypt?

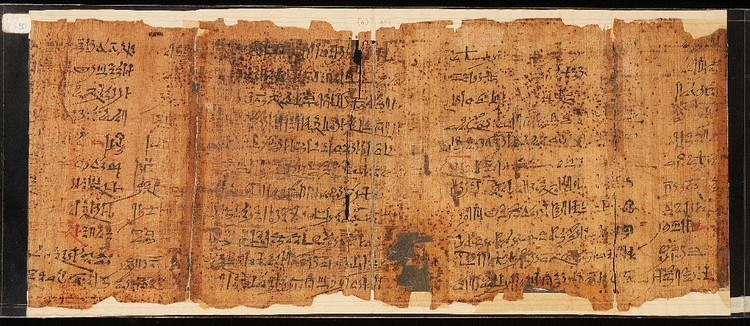

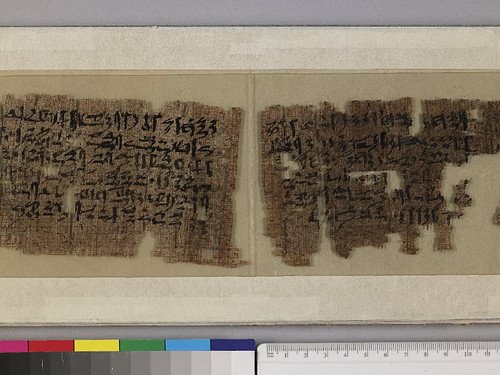

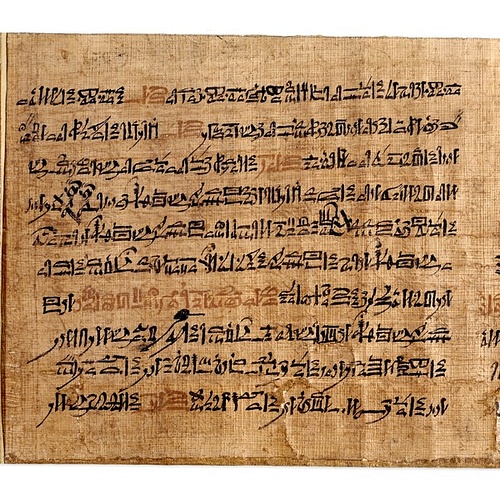

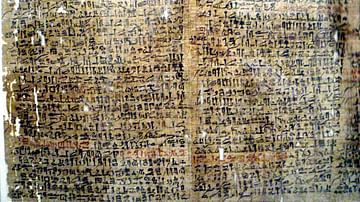

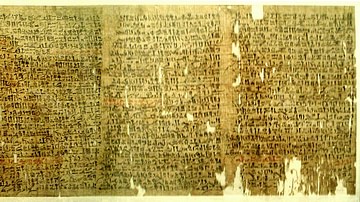

The two basic types of writing in ancient Egypt were hieroglyphs, which were used for monuments and display, and the cursive form known as hieratic, invented at much the same time in late predynastic Egypt (c. 3000 BCE).

Which pharaoh probably built the first true pyramid?

Snefru was the first king of ancient Egypt of the 4th dynasty (c. 2575–c. 2465 BCE). He probably built the step pyramid of Maydūm and then modified it to form the first true pyramid.

Who was the first king to unify Upper and Lower Egypt?

Menes was the legendary first king of unified Egypt. According to tradition, he joined Upper and Lower Egypt in a single centralized monarchy and established ancient Egypt’s first dynasty. Menes is also credited with irrigation works and with founding the capital, Memphis.

Who discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun?

The tomb of Tutankhamun was discovered by Howard Carter in 1922.

Recent News

ancient Egypt , civilization in northeastern Africa that dates from the 4th millennium bce . Its many achievements, preserved in its art and monuments, hold a fascination that continues to grow as archaeological finds expose its secrets. This article focuses on Egypt from its prehistory through its unification under Menes (Narmer) in the 3rd millennium bce —sometimes used as a reference point for Egypt’s origin—and up to the Islamic conquest in the 7th century ce . For subsequent history through the contemporary period, see Egypt . For a list of ancient Egyptian dynasties , see list of dynasties of ancient Egypt . For a list of Egyptian kings from the Predynastic through Ptolemaic periods, see list of pharaohs of ancient Egypt .

Introduction to ancient Egyptian civilization

Ancient Egypt can be thought of as an oasis in the desert of northeastern Africa, dependent on the annual inundation of the Nile River to support its agricultural population. The country’s chief wealth came from the fertile floodplain of the Nile valley, where the river flows between bands of limestone hills, and the Nile delta , in which it fans into several branches north of present-day Cairo . Between the floodplain and the hills is a variable band of low desert that supported a certain amount of game. The Nile was Egypt’s sole transportation artery.

The First Cataract at Aswān , where the riverbed is turned into rapids by a belt of granite , was the country’s only well-defined boundary within a populated area. To the south lay the far less hospitable area of Nubia , in which the river flowed through low sandstone hills that in most regions left only a very narrow strip of cultivable land. Nubia was significant for Egypt’s periodic southward expansion and for access to products from farther south. West of the Nile was the arid Sahara , broken by a chain of oases some 125 to 185 miles (200 to 300 km) from the river and lacking in all other resources except for a few minerals. The eastern desert , between the Nile and the Red Sea, was more important, for it supported a small nomadic population and desert game, contained numerous mineral deposits, including gold , and was the route to the Red Sea .

To the northeast was the Isthmus of Suez . It offered the principal route for contact with Sinai , from which came turquoise and possibly copper , and with southwestern Asia , Egypt’s most important area of cultural interaction, from which were received stimuli for technical development and cultivars for crops. Immigrants and ultimately invaders crossed the isthmus into Egypt, attracted by the country’s stability and prosperity. From the late 2nd millennium bce onward, numerous attacks were made by land and sea along the eastern Mediterranean coast.

At first, relatively little cultural contact came by way of the Mediterranean Sea , but from an early date Egypt maintained trading relations with the Lebanese port of Byblos (present-day Jbail). Egypt needed few imports to maintain basic standards of living, but good timber was essential and not available within the country, so it usually was obtained from Lebanon . Minerals such as obsidian and lapis lazuli were imported from as far afield as Anatolia and Afghanistan .

Agriculture centered on the cultivation of cereal crops, chiefly emmer wheat ( Triticum dicoccum ) and barley ( Hordeum vulgare ). The fertility of the land and general predictability of the inundation ensured very high productivity from a single annual crop. This productivity made it possible to store large surpluses against crop failures and also formed the chief basis of Egyptian wealth, which was, until the creation of the large empires of the 1st millennium bce , the greatest of any state in the ancient Middle East .

Basin irrigation was achieved by simple means, and multiple cropping was not feasible until much later times, except perhaps in the lakeside area of Al-Fayyūm . As the river deposited alluvial silt , raising the level of the floodplain, and land was reclaimed from marsh, the area available for cultivation in the Nile valley and delta increased, while pastoralism declined slowly. In addition to grain crops, fruit and vegetables were important, the latter being irrigated year-round in small plots. Fish was also vital to the diet. Papyrus , which grew abundantly in marshes, was gathered wild and in later times was cultivated . It may have been used as a food crop, and it certainly was used to make rope, matting, and sandals. Above all, it provided the characteristic Egyptian writing material, which, with cereals, was the country’s chief export in Late period Egyptian and then Greco-Roman times.

Cattle may have been domesticated in northeastern Africa. The Egyptians kept many as draft animals and for their various products, showing some of the interest in breeds and individuals that is found to this day in the Sudan and eastern Africa . The donkey , which was the principal transport animal (the camel did not become common until Roman times), was probably domesticated in the region. The native Egyptian breed of sheep became extinct in the 2nd millennium bce and was replaced by an Asiatic breed. Sheep were primarily a source of meat; their wool was rarely used. Goats were more numerous than sheep. Pigs were also raised and eaten. Ducks and geese were kept for food, and many of the vast numbers of wild and migratory birds found in Egypt were hunted and trapped. Desert game, principally various species of antelope and ibex , were hunted by the elite; it was a royal privilege to hunt lions and wild cattle. Pets included dogs , which were also used for hunting, cats , and monkeys . In addition, the Egyptians had a great interest in, and knowledge of, most species of mammals, birds, reptiles, and fish in their environment .

Most Egyptians were probably descended from settlers who moved to the Nile valley in prehistoric times, with population increase coming through natural fertility. In various periods there were immigrants from Nubia , Libya , and especially the Middle East . They were historically significant and also may have contributed to population growth , but their numbers are unknown. Most people lived in villages and towns in the Nile valley and delta. Dwellings were normally built of mud brick and have long since disappeared beneath the rising water table or beneath modern town sites, thereby obliterating evidence for settlement patterns. In antiquity, as now, the most favored location of settlements was on slightly raised ground near the riverbank, where transport and water were easily available and flooding was unlikely. Until the 1st millennium bce , Egypt was not urbanized to the same extent as Mesopotamia. Instead, a few centers, notably Memphis and Thebes , attracted population and particularly the elite, while the rest of the people were relatively evenly spread over the land. The size of the population has been estimated as having risen from 1 to 1.5 million in the 3rd millennium bce to perhaps twice that number in the late 2nd millennium and 1st millennium bce . (Much higher levels of population were reached in Greco-Roman times.)

Nearly all of the people were engaged in agriculture and were probably tied to the land. In theory all the land belonged to the king, although in practice those living on it could not easily be removed and some categories of land could be bought and sold. Land was assigned to high officials to provide them with an income, and most tracts required payment of substantial dues to the state, which had a strong interest in keeping the land in agricultural use. Abandoned land was taken back into state ownership and reassigned for cultivation. The people who lived on and worked the land were not free to leave and were obliged to work it, but they were not enslaved; most paid a proportion of their produce to major officials. Free citizens who worked the land on their own behalf did emerge; terms applied to them tended originally to refer to poor people, but these agriculturalists were probably not poor. Slavery was never common, being restricted to captives and foreigners or to people who were forced by poverty or debt to sell themselves into service. Enslaved persons sometimes even married members of their owners’ families, so that in the long term those belonging to households tended to be assimilated into free society. In the New Kingdom (from about 1539 to 1077 bce ), large numbers of captives were enslaved and acquired by major state institutions or incorporated into the army. Punitive treatment of enslaved foreigners or of native fugitives from their obligations included forced labor, exile (in, for example, the oases of the western desert), or compulsory enlistment in dangerous mining expeditions. Even nonpunitive employment such as quarrying in the desert was hazardous. The official record of one expedition shows a mortality rate of more than 10 percent.

Just as the Egyptians optimized agricultural production with simple means, their crafts and techniques, many of which originally came from Asia, were raised to extraordinary levels of perfection. The Egyptians’ most striking technical achievement, massive stone building, also exploited the potential of a centralized state to mobilize a huge labor force, which was made available by efficient agricultural practices. Some of the technical and organizational skills involved were remarkable. The construction of the great pyramids of the 4th dynasty (c. 2543–c. 2436 bce ) has yet to be fully explained and would be a major challenge to this day. This expenditure of skill contrasts with sparse evidence of an essentially neolithic way of living for the rural population of the time, while the use of flint tools persisted even in urban environments at least until the late 2nd millennium bce . Metal was correspondingly scarce, much of it being used for prestige rather than everyday purposes.

In urban and elite contexts , the Egyptian ideal was the nuclear family , but, on the land and even within the central ruling group, there is evidence for extended families . Egyptians were monogamous, and the choice of partners in marriage, for which no formal ceremony or legal sanction is known, did not follow a set pattern. Consanguineous marriage was not practiced during the Dynastic period, except for the occasional marriage of a brother and sister within the royal family, and that practice may have been open only to kings or heirs to the throne. Divorce was in theory easy, but it was costly. Women had a legal status only marginally inferior to that of men. They could own and dispose of property in their own right, and they could initiate divorce and other legal proceedings. They hardly ever held administrative office but increasingly were involved in religious cults as priestesses or “chantresses.” Married women held the title “mistress of the house,” the precise significance of which is unknown. Lower down the social scale, they probably worked on the land as well as in the house.

The uneven distribution of wealth, labor, and technology was related to the only partly urban character of society, especially in the 3rd millennium bce . The country’s resources were not fed into numerous provincial towns but instead were concentrated to great effect around the capital—itself a dispersed string of settlements rather than a city—and focused on the central figure in society, the king. In the 3rd and early 2nd millennia, the elite ideal, expressed in the decoration of private tombs, was manorial and rural. Not until much later did Egyptians develop a more pronouncedly urban character.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Ancient Egypt

By: History.com Editors

Updated: April 24, 2023 | Original: October 14, 2009

Ancient Egypt was the preeminent civilization in the Mediterranean world for almost 30 centuries—from its unification around 3100 B.C. to its conquest by Alexander the Great in 332 B.C. From the great pyramids of the Old Kingdom through the military conquests of the New Kingdom, Egypt’s majesty has long entranced archaeologists and historians and created a vibrant field of study all its own: Egyptology. The main sources of information about ancient Egypt are the many monuments, objects and artifacts that have been recovered from archaeological sites, covered with hieroglyphs that have only recently been deciphered. The picture that emerges is of a culture with few equals in the beauty of its art, the accomplishment of its architecture or the richness of its religious traditions.

Predynastic Period (c. 5000-3100 B.C.)

Few written records or artifacts have been found from the Predynastic Period, which encompassed at least 2,000 years of gradual development of the Egyptian civilization.

Did you know? During the rule of Akhenaton, his wife Nefertiti played an important political and religious role in the monotheistic cult of the sun god Aton. Images and sculptures of Nefertiti depict her famous beauty and role as a living goddess of fertility.

Neolithic (late Stone Age ) communities in northeastern Africa exchanged hunting for agriculture and made early advances that paved the way for the later development of Egyptian arts and crafts, technology, politics and religion (including a great reverence for the dead and possibly a belief in life after death).

Around 3400 B.C., two separate kingdoms were established near the Fertile Crescent , an area home to some of the world’s oldest civilizations: the Red Land to the north, based in the Nile River Delta and extending along the Nile perhaps to Atfih; and the White Land in the south, stretching from Atfih to Gebel es-Silsila. A southern king, Scorpion, made the first attempts to conquer the northern kingdom around 3200 B.C. A century later, King Menes would subdue the north and unify the country, becoming the first king of the first dynasty.

Archaic (Early Dynastic) Period (c. 3100-2686 B.C.)

King Menes founded the capital of ancient Egypt at White Walls (later known as Memphis), in the north, near the apex of the Nile River delta. The capital would grow into a great metropolis that dominated Egyptian society during the Old Kingdom period. The Archaic Period saw the development of the foundations of Egyptian society, including the all-important ideology of kingship. To the ancient Egyptians, the king was a godlike being, closely identified with the all-powerful god Horus. The earliest known hieroglyphic writing also dates to this period.

In the Archaic Period, as in all other periods, most ancient Egyptians were farmers living in small villages, and agriculture (largely wheat and barley) formed the economic base of the Egyptian state. The annual flooding of the great Nile River provided the necessary irrigation and fertilization each year; farmers sowed the wheat after the flooding receded and harvested it before the season of high temperatures and drought returned.

Old Kingdom: Age of the Pyramid Builders (c. 2686-2181 B.C.)

The Great Sphinx

The Great Sphinx is an engineering marvel even by today’s standards.

Massive Stones Moved to Build Monuments

In this Lost Worlds video, brought to you by the History Channel, learn about man’s ability to come up with creative solutions to move stone throughout history. Watch as this video takes us from Egypt to Greece to Jerusalem showing us different solutions throughout history for constructing giant structures like obelisks and temples.

The Old Kingdom began with the third dynasty of pharaohs. Around 2630 B.C., the third dynasty’s King Djoser asked Imhotep, an architect, priest and healer, to design a funerary monument for him; the result was the world’s first major stone building, the Step-Pyramid at Saqqara, near Memphis. Egyptian pyramid -building reached its zenith with the construction of the Great Pyramid at Giza, on the outskirts of Cairo. Built for Khufu (or Cheops, in Greek), who ruled from 2589 to 2566 B.C., the pyramid was later named by classical historians as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World . The ancient Greek historian Herodotus estimated that it took 100,000 men 20 years to build it. Two other pyramids were built at Giza for Khufu’s successors Khafra (2558-2532 B.C) and Menkaura (2532-2503 B.C.).

During the third and fourth dynasties, Egypt enjoyed a golden age of peace and prosperity. The pharaohs held absolute power and provided a stable central government; the kingdom faced no serious threats from abroad; and successful military campaigns in foreign countries like Nubia and Libya added to its considerable economic prosperity. Over the course of the fifth and sixth dynasties, the king’s wealth was steadily depleted, partially due to the huge expense of pyramid-building, and his absolute power faltered in the face of the growing influence of the nobility and the priesthood that grew up around the sun god Ra (Re). After the death of the sixth dynasty’s King Pepy II, who ruled for some 94 years, the Old Kingdom period ended in chaos.

First Intermediate Period (c. 2181-2055 B.C.)

On the heels of the Old Kingdom’s collapse, the seventh and eighth dynasties consisted of a rapid succession of Memphis-based rulers until about 2160 B.C., when the central authority completely dissolved, leading to civil war between provincial governors. This chaotic situation was intensified by Bedouin invasions and accompanied by famine and disease.

From this era of conflict emerged two different kingdoms: A line of 17 rulers (dynasties nine and 10) based in Heracleopolis ruled Middle Egypt between Memphis and Thebes, while another family of rulers arose in Thebes to challenge Heracleopolitan power. Around 2055 B.C., the Theban prince Mentuhotep managed to topple Heracleopolis and reunited Egypt, beginning the 11th dynasty and ending the First Intermediate Period.

Middle Kingdom: 12th Dynasty (c. 2055-1786 B.C.)

After the last ruler of the 11th dynasty, Mentuhotep IV, was assassinated, the throne passed to his vizier, or chief minister, who became King Amenemhet I, founder of dynasty 12. A new capital was established at It-towy, south of Memphis, while Thebes remained a great religious center. During the Middle Kingdom, Egypt once again flourished, as it had during the Old Kingdom. The 12th dynasty kings ensured the smooth succession of their line by making each successor co-regent, a custom that began with Amenemhet I.

Middle-Kingdom Egypt pursued an aggressive foreign policy, colonizing Nubia (with its rich supply of gold, ebony, ivory and other resources) and repelling the Bedouins who had infiltrated Egypt during the First Intermediate Period. The kingdom also built diplomatic and trade relations with Syria , Palestine and other countries; undertook building projects including military fortresses and mining quarries; and returned to pyramid-building in the tradition of the Old Kingdom. The Middle Kingdom reached its peak under Amenemhet III (1842-1797 B.C.); its decline began under Amenenhet IV (1798-1790 B.C.) and continued under his sister and regent, Queen Sobekneferu (1789-1786 B.C.), who was the first confirmed female ruler of Egypt and the last ruler of the 12th dynasty.

Second Intermediate Period (c. 1786-1567 B.C.)

The 13th dynasty marked the beginning of another unsettled period in Egyptian history, during which a rapid succession of kings failed to consolidate power. As a consequence, during the Second Intermediate Period Egypt was divided into several spheres of influence. The official royal court and seat of government was relocated to Thebes, while a rival dynasty (the 14th), centered on the city of Xois in the Nile delta, seems to have existed at the same time as the 13th.

Around 1650 B.C., a line of foreign rulers known as the Hyksos took advantage of Egypt’s instability to take control. The Hyksos rulers of the 15th dynasty adopted and continued many of the existing Egyptian traditions in government as well as culture. They ruled concurrently with the line of native Theban rulers of the 17th dynasty, who retained control over most of southern Egypt despite having to pay taxes to the Hyksos. (The 16th dynasty is variously believed to be Theban or Hyksos rulers.) Conflict eventually flared between the two groups, and the Thebans launched a war against the Hyksos around 1570 B.C., driving them out of Egypt.

Ramses’ Temple at Abu Simbel

Ramses built the Temple at Abu Simbel in Egypt to intimidate his enemies and seat himself amongst the gods.

Building the Great Obelisks at Luxor

Workers carved the 700‑ton Obelisks of Luxor from a single piece of red granite.

History of the Mummy

A step by step process of how a body was prepared for mummification. The brain was removed along with all other major organs except the heart.

New Kingdom (c. 1567-1085 B.C.)

Under Ahmose I, the first king of the 18th dynasty, Egypt was once again reunited. During the 18th dynasty, Egypt restored its control over Nubia and began military campaigns in Palestine , clashing with other powers in the area such as the Mitannians and the Hittites. The country went on to establish the world’s first great empire, stretching from Nubia to the Euphrates River in Asia. In addition to powerful kings such as Amenhotep I (1546-1526 B.C.), Thutmose I (1525-1512 B.C.) and Amenhotep III (1417-1379 B.C.), the New Kingdom was notable for the role of royal women such as Queen Hatshepsut (1503-1482 B.C.), who began ruling as a regent for her young stepson (he later became Thutmose III, Egypt’s greatest military hero), but rose to wield all the powers of a pharaoh.

The controversial Amenhotep IV (c. 1379-1362), of the late 18th dynasty, undertook a religious revolution, disbanding the priesthoods dedicated to Amon-Re (a combination of the local Theban god Amon and the sun god Re) and forcing the exclusive worship of another sun-god, Aton. Renaming himself Akhenaton (“servant of the Aton”), he built a new capital in Middle Egypt called Akhetaton, known later as Amarna. Upon Akhenaton’s death, the capital returned to Thebes and Egyptians returned to worshiping a multitude of gods. The 19th and 20th dynasties, known as the Ramesside period (for the line of kings named Ramses) saw the restoration of the weakened Egyptian empire and an impressive amount of building, including great temples and cities. According to biblical chronology, the exodus of Moses and the Israelites from Egypt possibly occurred during the reign of Ramses II (1304-1237 B.C.).

All of the New Kingdom rulers (with the exception of Akhenaton) were laid to rest in deep, rock-cut tombs (not pyramids) in the Valley of the Kings, a burial site on the west bank of the Nile opposite Thebes. Most of them were raided and destroyed, with the exception of the tomb and treasure of Tutankhamen (c.1361-1352 B.C.), discovered largely intact in A.D. 1922. The splendid mortuary temple of the last great king of the 20th dynasty, Ramses III (c. 1187-1156 B.C.), was also relatively well preserved, and indicated the prosperity Egypt still enjoyed during his reign. The kings who followed Ramses III were less successful: Egypt lost its provinces in Palestine and Syria for good and suffered from foreign invasions (notably by the Libyans), while its wealth was being steadily but inevitably depleted.

Third Intermediate Period (c. 1085-664 B.C.)

The next 400 years–known as the Third Intermediate Period–saw important changes in Egyptian politics, society and culture. Centralized government under the 21st dynasty pharaohs gave way to the resurgence of local officials, while foreigners from Libya and Nubia grabbed power for themselves and left a lasting imprint on Egypt’s population. The 22nd dynasty began around 945 B.C. with King Sheshonq, a descendant of Libyans who had invaded Egypt during the late 20th dynasty and settled there. Many local rulers were virtually autonomous during this period and dynasties 23-24 are poorly documented.

In the eighth century B.C., Nubian pharaohs beginning with Shabako, ruler of the Nubian kingdom of Kush, established their own dynasty–the 25th–at Thebes. Under Kushite rule, Egypt clashed with the growing Assyrian empire. In 671 B.C., the Assyrian ruler Esarhaddon drove the Kushite king Taharka out of Memphis and destroyed the city; he then appointed his own rulers out of local governors and officials loyal to the Assyrians. One of them, Necho of Sais, ruled briefly as the first king of the 26th dynasty before being killed by the Kushite leader Tanuatamun, in a final, unsuccessful grab for power.

9 Fascinating Finds From King Tut’s Tomb

A dagger crafted from meteorite and the remains of King Tut's stillborn daughters are among the stunning artifacts found in the tomb.

10 Little‑Known Facts About Cleopatra

Check out 10 surprising facts about the fabled Queen of the Nile.

What Caused Ancient Egypt’s Decline?

The once‑great empire on the Nile was slowly brought to its knees by a centuries‑long drought, economic crises and opportunistic foreign invaders.

From the Late Period to Alexander’s Conquest (c.664-332 B.C.)

Beginning with Necho’s son, Psammetichus, the Saite dynasty ruled a reunified Egypt for less than two centuries. In 525 B.C., Cambyses, king of Persia, defeated Psammetichus III, the last Saite king, at the Battle of Pelusium, and Egypt became part of the Persian Empire . Persian rulers such as Darius (522-485 B.C.) ruled the country largely under the same terms as native Egyptian kings: Darius supported Egypt’s religious cults and undertook the building and restoration of its temples. The tyrannical rule of Xerxes (486-465 B.C.) sparked increased uprisings under him and his successors. One of these rebellions triumphed in 404 B.C., beginning one last period of Egyptian independence under native rulers (dynasties 28-30).

In the mid-fourth century B.C., the Persians again attacked Egypt, reviving their empire under Ataxerxes III in 343 B.C. Barely a decade later, in 332 B.C., Alexander the Great of Macedonia defeated the armies of the Persian Empire and conquered Egypt. After Alexander’s death, Egypt was ruled by a line of Macedonian kings, beginning with Alexander’s general Ptolemy and continuing with his descendants. The last ruler of Ptolemaic Egypt–the legendary Cleopatra VII–surrendered Egypt to the armies of Octavian (later Augustus ) in 31 B.C. Six centuries of Roman rule followed, during which Christianity became the official religion of Rome and the Roman Empire’s provinces (including Egypt). The conquest of Egypt by the Arabs in the seventh century A.D. and the introduction of Islam would do away with the last outward aspects of ancient Egyptian culture and propel the country towards its modern incarnation.

Photo Galleries

HISTORY Vault: Ancient History

From Egypt to Greece, explore fascinating documentaries about the ancient world.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

115 Ancient Egypt Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

Ancient Egypt is one of the most fascinating civilizations in history, with a rich culture, impressive architecture, and numerous achievements that still amaze us today. If you're studying this ancient civilization or simply have a keen interest in it, you may find yourself needing essay topic ideas. To help you out, here are 115 Ancient Egypt essay topic ideas and examples that cover various aspects of this captivating civilization:

- The significance of the Nile River in Ancient Egypt's development.

- The role of pharaohs in Ancient Egypt's political structure.

- Comparing and contrasting the roles of men and women in Ancient Egyptian society.

- The construction and purpose of the pyramids.

- The religious beliefs and practices of Ancient Egyptians.

- The process of mummification and its importance in Ancient Egypt.

- The significance of hieroglyphics in Ancient Egyptian communication.

- The influence of Ancient Egyptian art on other civilizations.

- The impact of trade and commerce on Ancient Egypt's economy.

- Exploring the social hierarchy in Ancient Egyptian society.

- The role of priests and temples in Ancient Egyptian religious life.

- The importance of the afterlife in Ancient Egyptian beliefs.

- The contributions of Ancient Egyptian mathematics and astronomy.

- The role of women in religion and worship in Ancient Egypt.

- The influence of Ancient Egyptian medicine on modern practices.

- The cultural significance of Ancient Egyptian jewelry.

- The process of deciphering hieroglyphics and its impact on our understanding of Ancient Egypt.

- The role of animals in Ancient Egyptian religion and symbolism.

- The impact of the annual flooding of the Nile on Ancient Egyptian agriculture.

- The evolution of Ancient Egyptian architecture over time.

- The use of magic and amulets in Ancient Egyptian society.

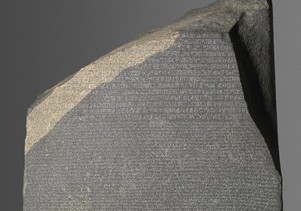

- The significance of the Rosetta Stone in decoding Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics.

- The role of music and dance in Ancient Egyptian culture.

- The impact of foreign invasions on Ancient Egypt's decline.

- The portrayal of Ancient Egypt in popular culture and media.

- The importance of Ancient Egyptian literature and storytelling.

- The influence of Ancient Egyptian fashion on later civilizations.

- The role of scribes in Ancient Egyptian society.

- The impact of climate change on Ancient Egypt's civilization.

- The significance of obelisks in Ancient Egyptian architecture.

- The role of Nubia in Ancient Egypt's trade and cultural exchange.

- The importance of Ancient Egyptian festivals and celebrations.

- The influence of Ancient Egyptian beliefs and practices on modern spirituality.

- The significance of the Book of the Dead in Ancient Egyptian funerary rituals.

- The role of women as rulers in Ancient Egypt.

- The impact of Ancient Egyptian inventions on later civilizations.

- The process of creating papyrus and its importance in Ancient Egyptian writing.

- The role of Ancient Egyptian gods and goddesses in everyday life.

- The impact of the Hittite-Egyptian peace treaty on Ancient Egypt's foreign relations.

- The significance of Ancient Egyptian tombs and burial rituals.

- The role of Ancient Egyptian education and learning.

- The impact of natural resources on Ancient Egypt's economy.

- The development of Ancient Egyptian military strategies and weapons.

- The significance of the Valley of the Kings in Ancient Egyptian history.

- The role of Ancient Egyptian queens in the royal family.

- The impact of Ancient Egyptian agriculture on food production.

- The significance of the Sphinx in Ancient Egyptian mythology.

- The role of magic and spells in Ancient Egyptian daily life.

- The influence of Ancient Egyptian architecture on Greek and Roman structures.

- The significance of the Amarna Period in Ancient Egyptian history.

- The impact of Ancient Egyptian trade routes on cultural exchange.

- The role of Ancient Egyptian priests in maintaining social order.

- The significance of the Great Sphinx in relation to pharaohs.

- The influence of Ancient Egyptian hairstyles and cosmetics on fashion trends.

- The impact of Ancient Egyptian astronomy on navigation.

- The significance of Ancient Egyptian chariots in warfare.

- The role of Ancient Egyptian priests in healing and medicine.

- The impact of Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics on writing systems.

- The significance of the Temple of Luxor in Ancient Egyptian religion.

- The role of Ancient Egyptian queens as regents.

- The influence of Ancient Egyptian architecture on modern-day buildings.

- The significance of Ancient Egyptian amulets in protection and symbolism.

- The impact of Ancient Egyptian textiles on fashion and design.

- The role of Ancient Egyptian pharaohs as divine rulers.

- The significance of Ancient Egyptian animal mummies in religious rituals.

- The influence of Ancient Egyptian musical instruments on later civilizations.

- The impact of Ancient Egyptian irrigation systems on agriculture.

- The role of Ancient Egyptian artisans in creating beautiful artwork.

- The significance of Ancient Egyptian boats in trade and transportation.

- The importance of Ancient Egyptian mirrors and cosmetics in daily life.

- The impact of Ancient Egyptian temples on tourism today.

- The role of Ancient Egyptian priests in performing rituals and ceremonies.

- The significance of Ancient Egyptian board games in leisure activities.

- The influence of Ancient Egyptian hairstyles on beauty standards.

- The impact of Ancient Egyptian jewelry on fashion trends.

- The role of Ancient Egyptian scribes in record-keeping and administration.

- The significance of Ancient Egyptian canopic jars in mummification.

- The influence of Ancient Egyptian perfume on the fragrance industry.

- The impact of Ancient Egyptian courtship and marriage rituals.

- The role of Ancient Egyptian dancers in religious ceremonies.

- The significance of Ancient Egyptian wall paintings in tombs.

- The importance of Ancient Egyptian ophthalmology in eye treatments.

- The impact of Ancient Egyptian boats on maritime navigation.

- The role of Ancient Egyptian musicians in entertainment.

- The significance of Ancient Egyptian love poetry in literature.

- The influence of Ancient Egyptian hairstyles on modern hairdressing.

- The impact of Ancient Egyptian pottery on ceramics.

- The role of Ancient Egyptian embalmers in the mummification process.

- The significance of Ancient Egyptian scarab beetles in symbolism.

- The importance of Ancient Egyptian tattoos in body art.

- The impact of Ancient Egyptian agricultural practices on sustainable farming.

- The role of Ancient Egyptian architects in city planning.

- The significance of Ancient Egyptian animal worship in religion.

- The influence of Ancient Egyptian fashion on costume design.

- The impact of Ancient Egyptian musical notation on music composition.

- The role of Ancient Egyptian dancers in storytelling.

- The significance of Ancient Egyptian magical spells in daily life.

- The importance of Ancient Egyptian mirrors in personal grooming.

- The impact of Ancient Egyptian naval warfare on maritime history.

- The role of Ancient Egyptian queens as political advisors.

- The significance of Ancient Egyptian funeral processions in honoring the deceased.

- The influence of Ancient Egyptian hairstyles on modern hair accessories.

- The impact of Ancient Egyptian pottery on trade and cultural exchange.

- The role of Ancient Egyptian embalmers in preserving the dead.

- The significance of Ancient Egyptian scarab amulets in protection.

- The importance of Ancient Egyptian tattoos in social status.

- The influence of Ancient Egyptian agricultural techniques on modern farming.

- The impact of Ancient Egyptian architecture on urban planning.

- The role of Ancient Egyptian priests in animal worship.

- The significance of Ancient Egyptian fashion in expressing identity.

- The role of Ancient Egyptian musicians in religious ceremonies.

- The impact of Ancient Egyptian magical spells on daily life.

- The significance of Ancient Egyptian mirrors in reflecting beauty ideals.

- The importance of Ancient Egyptian naval technology in maritime exploration.

- The influence of Ancient Egyptian queens on political decision-making.

These essay topic ideas provide a broad range of choices for exploring various aspects of Ancient Egypt. Whether you're interested in its art, religion, social structure, or technological advancements, there's a topic here to suit your interests. Dive into the enchanting world of Ancient Egypt and discover the wonders of this ancient civilization through your essays.

Want to research companies faster?

Instantly access industry insights

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Leverage powerful AI research capabilities

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2024 Pitchgrade

Home — Essay Samples — History — Ancient Egypt — Egypt Civilization

Egypt Civilization

- Categories: Ancient Egypt

About this sample

Words: 800 |

Published: Mar 19, 2024

Words: 800 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Table of contents

I. introduction, ii. social structure in ancient egypt, iii. religious beliefs of ancient egypt, iv. artistic achievements in ancient egypt, v. legacy of ancient egypt civilization, vi. conclusion.

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: History

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

5 pages / 2258 words

2 pages / 746 words

2 pages / 740 words

3 pages / 1223 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Ancient Egypt

Ramses II, also known as Ramses the Great, was one of the most powerful and influential pharaohs in ancient Egypt. His reign, which lasted for over six decades, was marked by numerous accomplishments that solidified his legacy [...]

In conclusion, specialized workers in ancient Egypt, particularly artisans and craftsmen, played a crucial role in shaping the civilization's cultural and economic landscape. Their skills and expertise were essential for the [...]

During the 18th dynasty of ancient Egypt, Nefertiti and her husband Pharaoh Akhenaten were influential figures who left a lasting impact on the history and culture of Egypt. Their reign was marked by significant changes in [...]

The ancient civilizations of Sumer and Egypt have always fascinated researchers and historians due to their remarkable achievements in various fields. One particular aspect that contributed to the development and prosperity of [...]

In both ancient Egypt and ancient Mesopotamia, we can find many similarities and differences between their cultures. The laws of the two varied quite a bit, their literature was relatively similar, and the way women were [...]

According to our text, The Humanities, “King Tutankhamun was just a teenager when he died. For an ancient Egyptian pharaoh, presumably well-fed and fiercely protected, this was a premature demise. It was also momentous, for his [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

The world of ancient Egypt

Few civilizations have enjoyed the longevity and global cultural reach of ancient Egypt. Their distinct visual expressions, writing system, and imposing monuments are instantly recognizable by viewers all around the world even today—put simply, their branding was on point.

Pyramid of Khafre, Egypt (photo: MusikAnimal, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Despite portraying significant stability over a vast period of time, their civilization was not as static as it may appear at first glance, particularly if viewed through our modern eyes and cultural perspectives . Instead, the culture was dynamic even as it revolved around a stable core of imagery and concepts. The ancient Egyptians adjusted to new experiences, constantly adding to their complex beliefs about the divine and terrestrial realms, and how they interact. This flexibility, wrapped around a base of consistency, was part of the reason ancient Egypt survived for millennia and continues to fascinate.

Read an introductory essay about ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt: an introduction

/ 1 Completed

The Natural World of Egypt

View of the Nile River, Egypt (photo: Badics, CC BY-SA 3.0)

With the blazing sun above, flanked by vast seas of shifting sand, and fed by the life-giving Nile River (which hid frightening creatures beneath its dark waters), the natural world of Egypt was inherently beautiful but also potentially deadly. Outside the lush river valley, there was little protection from the ever-dominant sun, whose intensity was both feared and revered. The deserts were home not only to many dangerous creatures, but the sands themselves were also unpredictable and constantly shifting. The clear night skies dazzled with millions of stars, some of which seemed to move of their own accord while others rose and fell at trackable intervals. The Nile, with its annual floods, brought fertility and renewal to the land, but could also overflow and wreak havoc on the villages that lined its banks. Careful observers of their environment, the Egyptians perceived divine forces in these phenomena and many of their deities, such as the powerful sun god Ra, were connected with elements from the natural world.

Hieroglyphs, detail from the White Chapel, Karnak (photo: Dr. Amy Calvert)

The perception of divine powers existing in the natural world was particularly true in connection with the animals that inhabited the region. There was an array of creatures that the Egyptians would have observed or interacted with on a regular basis and they feature heavily in the culture. One of the most distinctive visual attributes of Egyptian imagery is the myriad deities that were portrayed in hybrid form, with a human body and animal head. In addition, a wide range of birds, fishes, mammals, reptiles, and other creatures appear prominently in the hieroglyphic script —there are dozens of different birds alone.

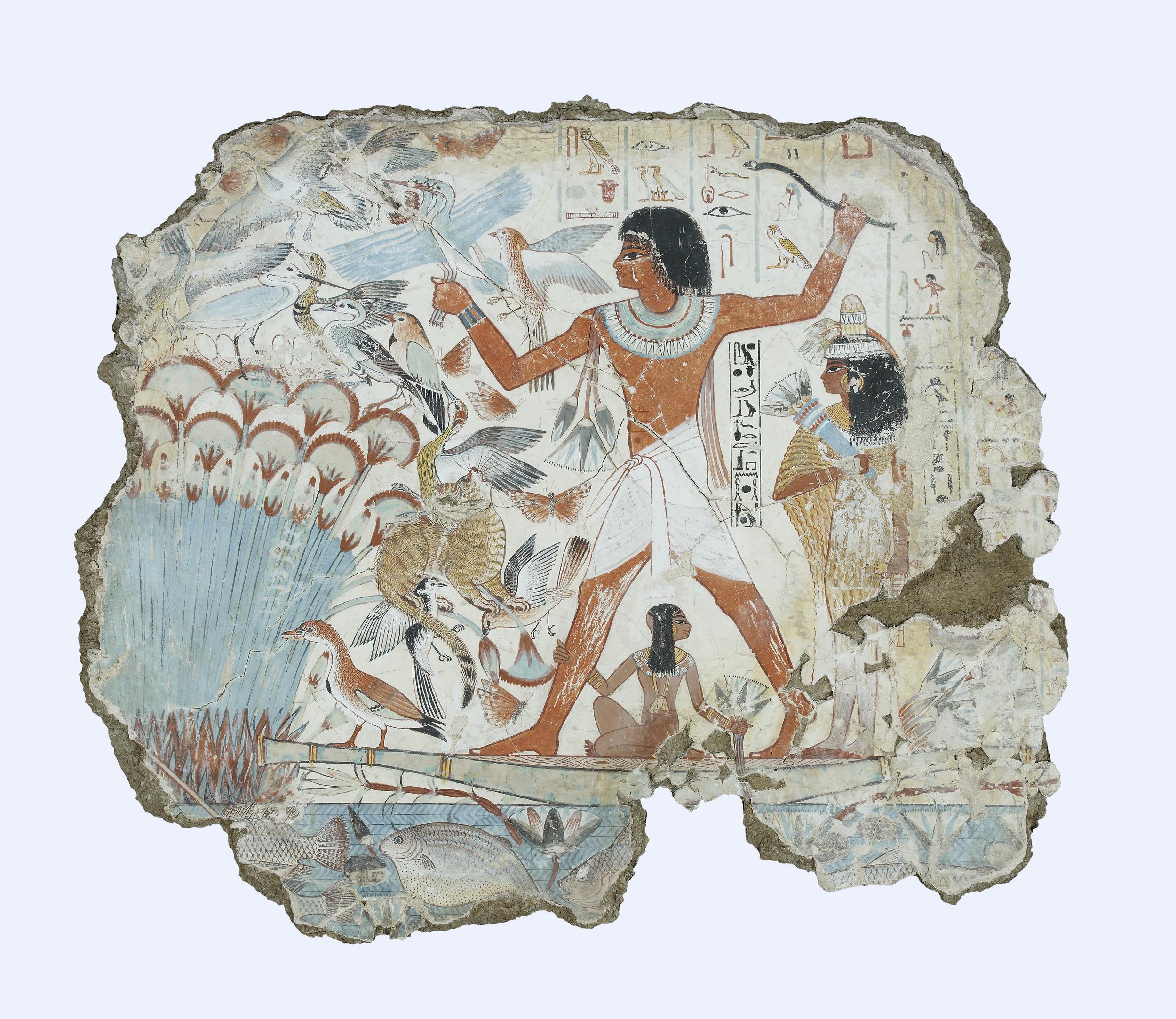

Nebamun fowling in the marshes, Tomb-chapel of Nebamun, c. 1350 B.C.E., 18th Dynasty, paint on plaster, 83 x 98 cm, Thebes (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The Nile was packed with numerous types of fish, which were recorded in great detail in fishing scenes that became a fixture in non-royal tombs. Most relief and painting throughout Egypt’s history was created for divine or mortuary settings and they were primarily intended to be functional. Many tomb scenes included the life-giving Nile and all it’s abundance with the goal of making that bounty available for the deceased in the afterlife. In addition to the array of fish, the river also teemed with far more dangerous animals, like crocodiles and hippopotami. Protective spells and magical gestures were used from early on to aid the Egyptians in avoiding those watery perils as they went about their daily lives.

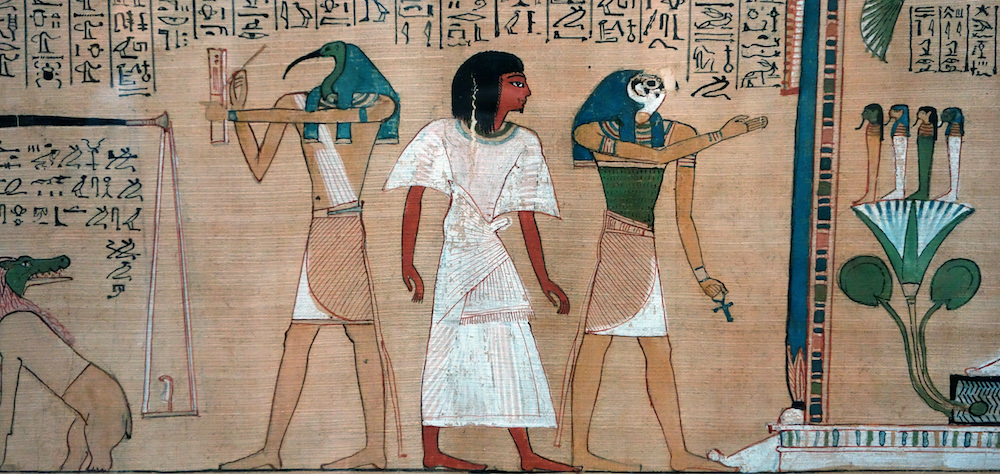

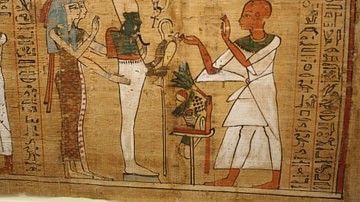

Hunefer (center) flanked by two deities: the ibis-headed Thoth (left) and the falcon-headed Horus (right), from Hunefer’s Judgement in the presence of Osiris, Book of the Dead of Hunefer, 19th Dynasty, New Kingdom, c. 1275 B.C.E., papyrus, Thebes, Egypt (British Museum)

The desert, likewise, was full of potentially dangerous creatures. Lions, leopards, jackals, cobras, and scorpions were all revered for their attributes and feared for their ferocity. Soaring above were birds of prey, like falcons who were sharp-eyed hunters, and massive vultures that consumed decaying flesh and fed it to their young. Scarab beetles also seemingly brought new life from decay and the sacred ibis with their curved beaks found sustenance hidden in the muddy banks of the Nile. All of these creatures (and many others) became closely associated with different deities very early in Egyptian history. The Egyptians did not worship animals; instead, certain animals were revered because it was believed that they were related to particular gods and thus served as earthly manifestations of those deities.

Model scene of workers ploughing a field, Middle Kingdom, late Dynasty 11, 2010–1961 B.C.E., wood, 54 cm (MFA Boston)

Even domesticated animals, such as cows, bulls, rams, and geese, became associated with deities and were viewed as vitally important. Cattle were probably the first animals to be domesticated in Egypt and domesticated cattle, donkeys, and rams appear along with wild animals on Predynastic and Early Dynastic votive objects , showing massive herds that were controlled by early rulers, demonstrating their wealth and prestige. Pastoral scenes of animal husbandry appear in numerous private tomb chapels and wooden models, providing detailed evidence of their daily practices. Herdsmen appear caring for their animals in depictions that include milking, calving, protecting the cattle as they cross the river, feeding, herding, and many other aspects of their day-to-day care.

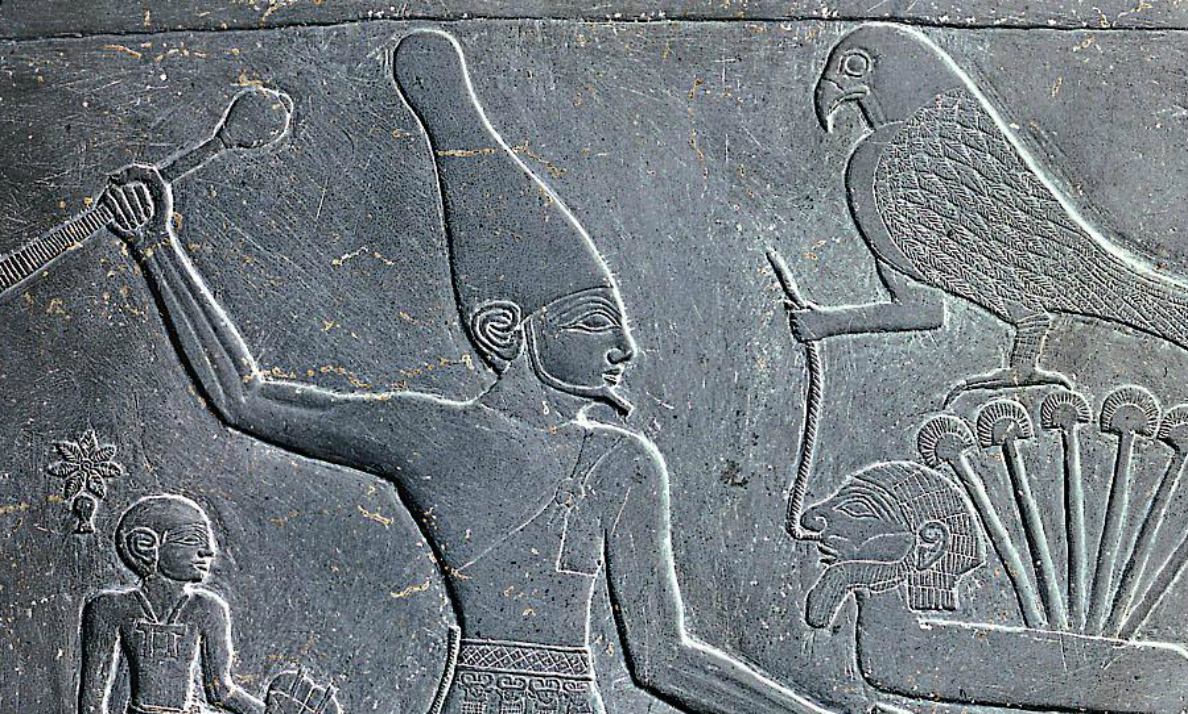

The Battlefield Palette , c. 3100 B.C.E., mudstone, found at el-Amarna, Egypt, 19.6 x 32.8 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Already in the Predynastic period the king was linked with the virile wild bull, an association that continues throughout Egyptian history—one of the primary items of royal regalia was a bull tail, which appears on a huge number of pharaonic images. An early connection between the king and lions is also apparent. One scene on a Predynastic ceremonial palette ( The Battlefield Palette), shows the triumphant king as a massive lion devouring his defeated foes. First Dynasty kings appear to have kept lion cubs as pets.

The Great Sphinx (photo: superblinkymac, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

In addition, lions (among other animals) were associated with the burials of some early rulers. One of the most iconic images from ancient Egypt is the massive Great Sphinx at Giza, which was sculpted from the living rock of the plateau. This fused form, with the body of a lion and the head of the king, became a common visual expression of royal power.

Historical Setting

While many of the religious and cultural characteristics of ancient Egypt were evident from very early on and continued all the way through the Roman era (contributing to overall cultural stability), sweeping conceptual developments and adoptions of external elements are also evident. Throughout ancient Egypt’s long history, periods of unified control were interspersed with moments of instability where parts of the country were controlled by different authorities. These repeated waves of political and cultural development create a decidedly complex history that spans thousands of years.

Read essays to understand the historical setting and basic characteristics of each era

Ancient Egyptian chronology and historical framework: an introduction

Predynastic and Early Dynastic: an introduction

Old Kingdom and First Intermediate Period: an introduction

Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period: an introduction

New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Period: an introduction

Late Period and the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods: an introduction

/ 6 Completed

Social Organization

Conceptually, the Egyptian state was an absolute monarchy where the office of pharaoh itself was considered divine. The pharaoh (king) was viewed as the earthly manifestation of the god Horus, and was responsible as the supreme commander for making all decisions affecting the nation. In reality, the king stood at the head of a hierarchical administrative structure with layers of civil officials that oversaw various systems and were responsible to the king for their success.

Seated Scribe , c. 2500 B.C.E., c. 4th Dynasty, Old Kingdom, painted limestone with rock crystal, magnesite, and copper/arsenic inlay for the eyes and wood for the nipples, found in Saqqara (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Most Egyptians followed the careers of their fathers and were taught by apprenticeship. Only the children of the higher classes, destined to become officials, were taught in schools and learned to read and write. Money in the modern sense did not exist in Egypt until the mid-fourth century B.C.E., so wages were usually paid in grain that could then be exchanged for copper or silver. Agriculture was the basis of the Egyptian economy and the foundation of the state, and produce was delivered to central storehouses to be administered and distributed.

Read essays about the various social strata in Egyptian society

Egyptian Social Organization: The Pharaoh

Egyptian Social Organization: Administrative officials, priests, ranks of the military, and the general population

/ 2 Completed

Art and Function

Large Kneeling Statue of Hatshepsut , c. 1479–1458 B.C.E., Dynasty 18, New Kingdom (Deir el-Bahri, Upper Egypt), granite, 261.5 x 80 x 137 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Egyptian art is sometimes viewed as static and abstract when compared with the more naturalistic depictions of other cultures (ancient Greece for example). Much of Egyptian imagery—especially royal imagery—was governed by decorum (a sense of what was appropriate), and remained extraordinarily consistent throughout its long history. This is why their art may appear unchanging—and this was intentional. For the ancient Egyptians, consistency was a virtue and an expression of political stability, divine balance, and clear evidence of ma’at and the correctness of their culture. The Egyptians even had a tendency, especially after periods of disunion, towards archaism where the artistic style would revert to that of the earlier Old Kingdom which was perceived as a “golden age.”

Read essays about art and function

Ancient Egyptian art: an introduction its function and basic characteristics

Materials and techniques in ancient Egyptian art: an introduction

Consistency and balance

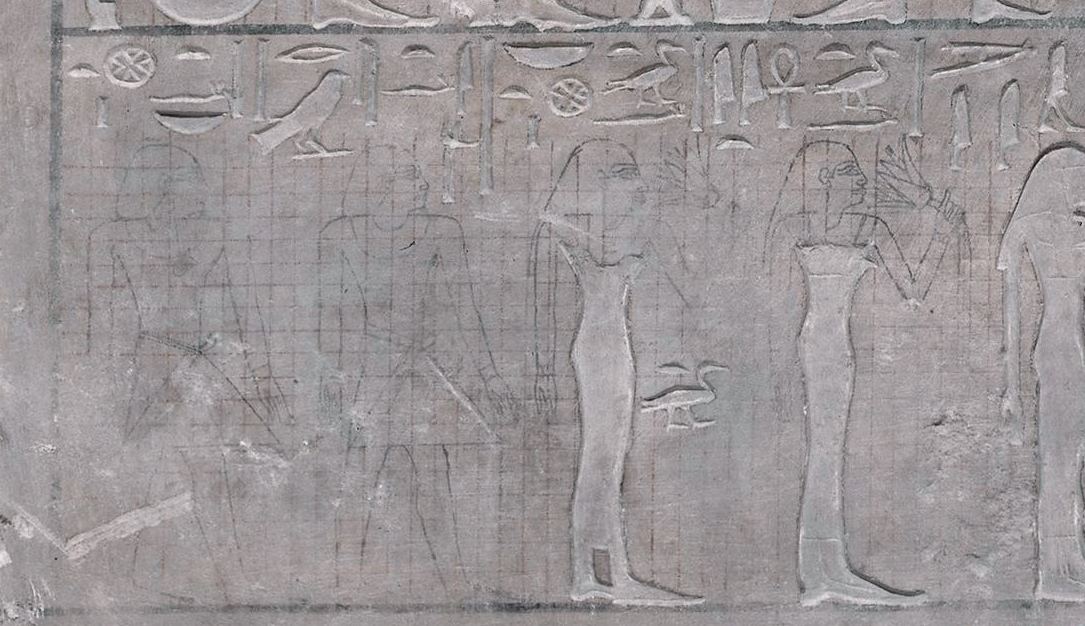

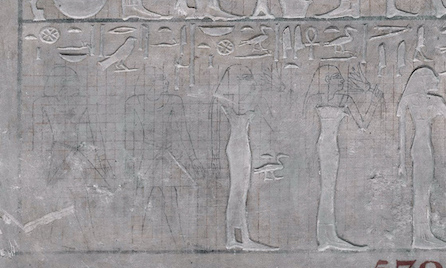

The canon of proportions grid is clearly visible in the lower, unfinished register of the Stela of Userwer, and the use of hieratic scale (where the most important figures are largest) is evident the second register that shows Userwer, his wife and his parents seated and at a larger scale than the figures offering before them. Detail of the stela of the sculptor Userwer, 12th dynasty, limestone, from Egypt, 52 x 48 cm wide (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Consistency in representation was closely related to a fundamental belief that depictions had an impact beyond the image itself. This belief led to an active resistance to changes in codified depictions. Even the way that figures were planned and laid out by the artists was codified. During the Old Kingdom, the Egyptians developed a grid system, referred to as the canon of proportions, for creating systematic figures with the same proportions. Grid lines aligned with the top of the head, top of the shoulder, waist, hips, knees, and bottom of the foot (among other body joints).

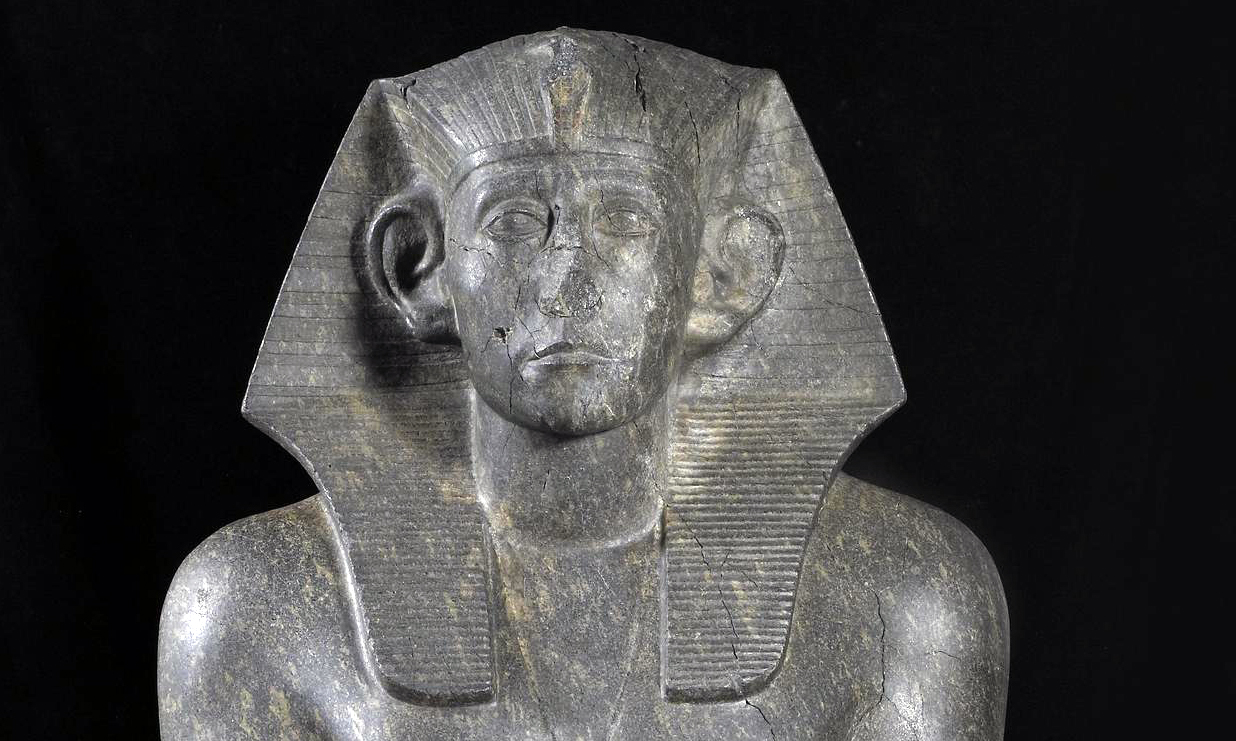

King Menkaura (Mycerinus) and Queen, 2490–2472 B.C.E., Old Kingdom, Dynasty 4, greywacke, Menkaura Valley Temple, Giza, Egypt, 142.2 x 57.1 x 55.2 cm, 676.8 kg (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The grid aided the artist in ensuring that the proportions of their figures were correct, but those proportions shifted over time. For example, although 18 squares was the standard used for much of Egypt’s history, in the Amarna period 20 squares were used, resulting in figures with more elongated proportions.

Thutmose, Model Bust of Queen Nefertiti , c. 1340 BCE, limestone and plaster, New Kingdom, 18th dynasty, Amarna Period (Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection/Neues Museum, Berlin)

Below are several examples of Egyptian art that demonstrate their primary stylistic characteristics. These include:

- the use of hierarchical scale

- the use of registers

- use of the canon of proportions (described above)

- a preference for balance

- the integration of perspectives.

Read essays and watch videos about consistency and balance

Stela of the sculptor Userwer: The lower part is still covered with the grid used for ensuring that the proportions of the figures were correct.

King Menkaure (Mycerinus) and queen: They both look beyond the present and into timeless eternity, their otherworldly visage displaying no human emotion whatsoever.

Thutmose, Model Bust of Queen Nefertiti : This stunning bust exemplifies a change in style.

The Seated Scribe: This painted statue differs from the ideal statues of pharaohs.

/ 4 Completed

Creative details

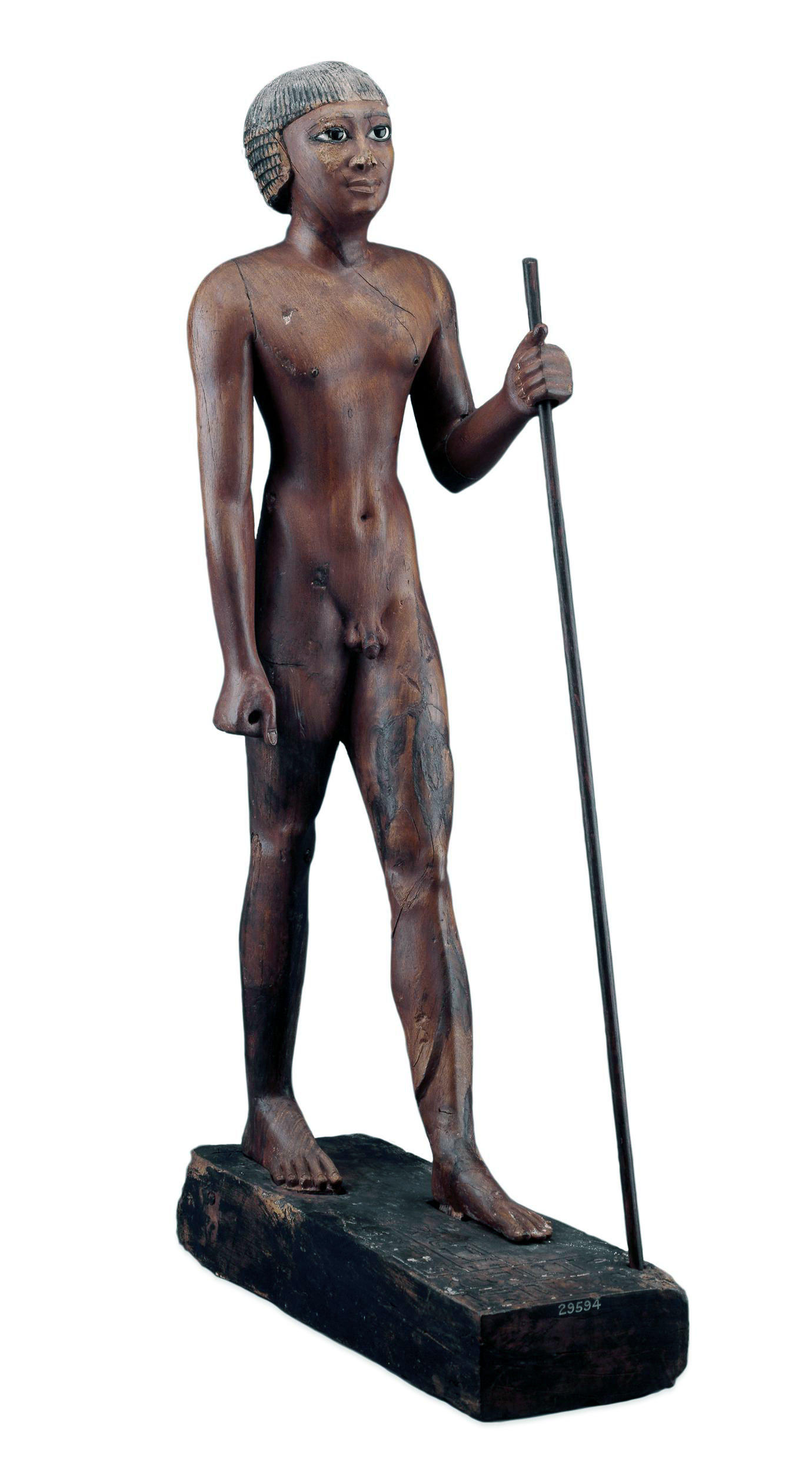

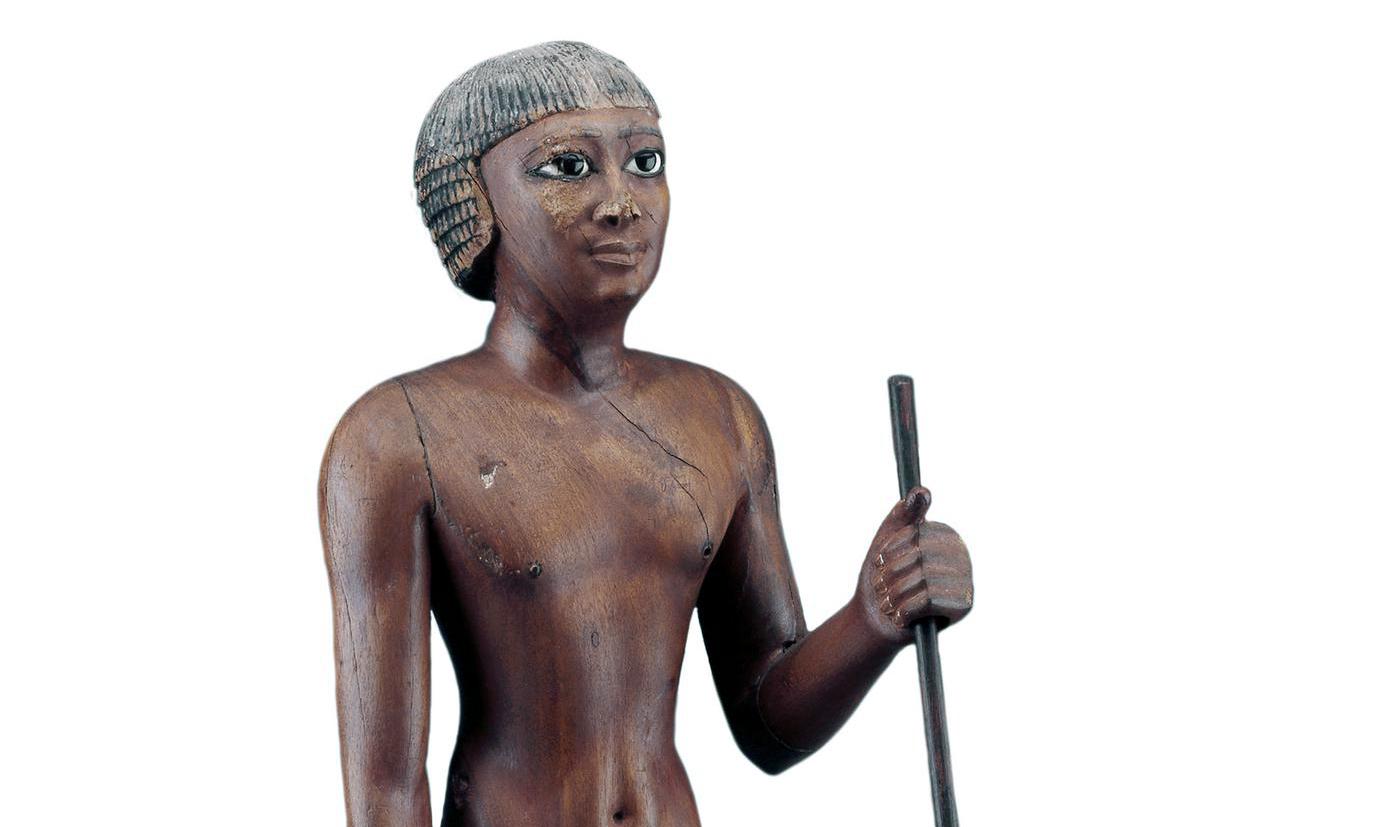

Nude figure of the Seal Bearer Tjetji, 2321 B.C.E.–2184 B.C.E. (6th Dynasty), from Akhmim, Upper Egypt, wood, obsidian, limestone, and copper, 75 cm high (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Although much Egyptian art is formal, many surviving examples of highly expressive depictions full of creative details prove that the ancient Egyptian artists were fully capable of naturalistic representations. Note, for example, the sensitive modeling of the musculature and close attention paid to realistic physical detail evident in a wood statue of a high official (the Seal Bearer Tjetji) from a Late Old Kingdom tomb. These very unusual and enigmatic statuettes of nude high officials, which are depicted in a standard pose of striding forward with left leg advanced and holding a long staff, were often painted and had eyes of inlaid stone set in copper.

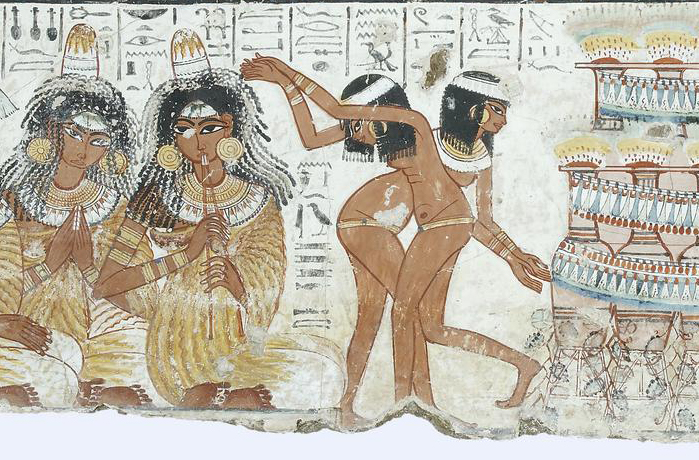

Musicians and dancers (detail), A feast for Nebamun, Tomb-chapel of Nebamun, c. 1350 B.C.E., 18th Dynasty, paint on plaster, whole fragment: 88 x 119 cm, Thebes © Trustees of the British Museum

Nebamun’s tomb, with its spectacular paintings, includes several examples that demonstrate a careful observation of the natural world—especially notable in the energetic hunting cat and the sinuous dancing of the entertainers at the banquet. A marvelous wooden head of Queen Tiye presents a woman of strong personality with details that hint at her formidable character.

Portrait Head of Queen Tiye with a Crown of Two Feathers , c. 1355 B.C.E., Amarna Period, Dynasty 18, New Kingdom, Egypt, yew wood, lapis lazuli, silver, gold, faience, 22.5 cm high (Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection at the Neues Museum, Berlin)

Read essays about creative details

Wooden tomb statue of Tjeti: T he sculptor of this example has carefully modeled the muscles on the torso and legs, and paid close attention to the detail of the face.

Paintings from the Tomb-chapel of Nebamun: He is shown hunting birds from a small boat in the marshes of the Nile with his wife Hatshepsut and their young daughter.

Portrait Head of Queen Tiye: She was a powerful figure, but her royal life was complicated, as demonstrated through this changing statue.

/ 3 Completed

Metalworking Traditions

Scene showing the manufacture of valuable items, such as jewelry. Wall-painting, probably from the tomb of Sobekhotep, Thebes, c. 1400 B.C.E., New Kingdom, reign of Thutmose IV, painted stucco, 60 x 58.5 (© Trustees of the British Museum)

Egyptian artisans were highly skilled metalworkers from early times; although few metal sculptures have survived, those that are preserved show an incredible level of technical achievement. As with other types of craft, like woodworking, preserved images of artisans in their workshops found in private tombs provide information about the processes of production For instance, we can see a group of jewelers at work in a painting from the tomb of Sebekhotep.

Pectoral and Necklace of Sithathoryunet with the Name of Senwosret II, Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12, reign of Senwosret II, c. 1887–1878 B.C.E., Egypt, Fayum Entrance Area, el-Lahun (Illahun, Kahun; Ptolemais Hormos), Tomb of Sithathoryunet (BSA Tomb 8), EES 1914, Gold, carnelian, feldspar, garnet, turquoise, lapis lazuli

The most beautifully crafted pieces of jewelry display elegant designs, incredible intricacy, and astonishingly precise stone-cutting and inlay, reaching a level that modern jewelers would be hard-pressed to achieve. The jewelry of a Middle Kingdom princess, found in her tomb at el-Lahun in the Fayum region is one spectacular example.

Statuette of Thutmose IV, 1400–1390 B.C.E., 19th Dynasty, ancient Egypt, bronze, silver, calcite, 14.7 x 6.4 cm (© Trustees of the British Museum)

The metal statues that survive demonstrate a high level of skill in both sheet working/metal forming and casting in copper and bronze. This marvelous hollow-cast bronze statuette of a kneeling Thutmosis IV, presenting an offering of wine, provides a peek into the abilities of Egypt’s craftsmen. Note that the arms were created separately and joined to the body on tenons and the eyes were originally inlaid.

Read essays and watch a video about metalworking traditions

Paintings from the tomb of Sebekhotep: Images show jewelers at work.

Pectoral and necklace of Sithathoryunet: Fashioned delicately in gold, carnelian, feldspar, garnet, turquoise, and lapis lazuli.

Bronze statuette of Thutmose IV: Very few metal statues survive that date from before the Late Period, though the Egyptians did have the technology to make large copper statues as early as the Old Kingdom.

This brief glimpse at the world of ancient Egypt is just a springboard for gaining an understanding of this compelling and complex culture.

A final note

The wonder of the internet is the astonishing access to information; one of the big problems with the internet is that anyone, regardless of knowledge or training, can post whatever they like and that information is presented at the same level as content put out by the experienced and trained. Information about ancient Egypt should always come from a well-vetted source, as there is a great deal of misinformation. The culture is astonishing enough on its own. Egypt remains highly influential across different areas of culture and vast swaths of time and space—Egyptian glass beads have been excavated in Viking tombs and revivals of Egyptian style still happen on an almost cyclical basis, even millenia later. We are surrounded by Egyptian imagery and concepts even if we don’t realize it; those emojis we use with such abandon are decidedly hieroglyphic. The more we know about what came before, the better we can grasp everything that has happened since. Only by understanding the past can we really envision the possibilities of the present and plan for the future.

Key questions to guide your reading

How did the annual flooding of the nile help form the egyptian view of the world, how might the regular behavior of certain animals—like falcons, vultures, snakes, and scarab beetles— suggest "heavenly wisdom" to the careful observer, how would you want to be depicted for eternity what identifying symbols would you want to include, terms to know and use.

canon of proportions

hierarchical scale

Need teaching images? Here is a Google Slideshow with many of the primary images in this chapter

Read a chapter about Ancient Egyptian religious life and afterlife

Collaborators

Dr. Amy Calvert

Dr. Beth Harris

Dr. Steven Zucker

The British Museum

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences