Infectious diseases

On this page, when to see a doctor, risk factors, complications, infectious diseases care at mayo clinic.

Our caring teams of professionals offer expert care to people with infectious diseases, injuries and illnesses.

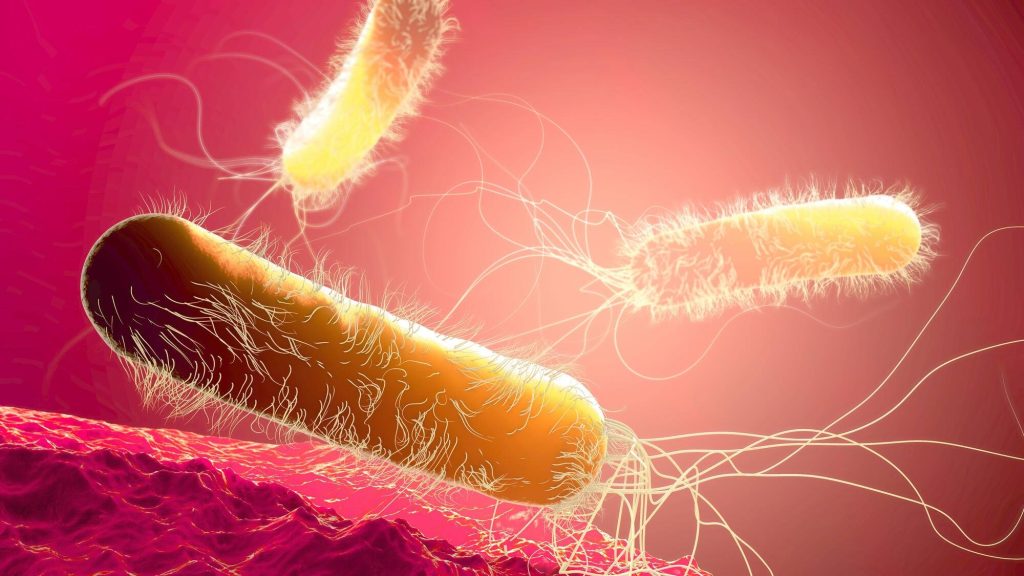

Infectious diseases are disorders caused by organisms — such as bacteria, viruses, fungi or parasites. Many organisms live in and on our bodies. They're normally harmless or even helpful. But under certain conditions, some organisms may cause disease.

Some infectious diseases can be passed from person to person. Some are transmitted by insects or other animals. And you may get others by consuming contaminated food or water or being exposed to organisms in the environment.

Signs and symptoms vary depending on the organism causing the infection, but often include fever and fatigue. Mild infections may respond to rest and home remedies, while some life-threatening infections may need hospitalization.

Many infectious diseases, such as measles and chickenpox, can be prevented by vaccines. Frequent and thorough hand-washing also helps protect you from most infectious diseases.

Products & Services

- A Book: Endemic - A Post-Pandemic Playbook

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Each infectious disease has its own specific signs and symptoms. General signs and symptoms common to a number of infectious diseases include:

- Muscle aches

Seek medical attention if you:

- Have been bitten by an animal

- Are having trouble breathing

- Have been coughing for more than a week

- Have severe headache with fever

- Experience a rash or swelling

- Have unexplained or prolonged fever

- Have sudden vision problems

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Infectious diseases can be caused by:

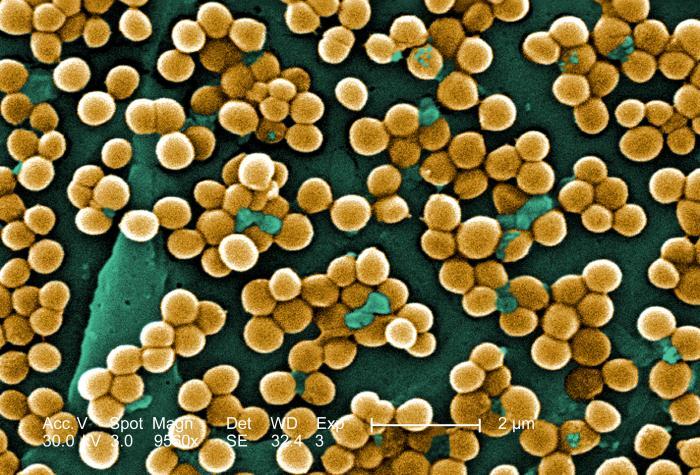

- Bacteria. These one-cell organisms are responsible for illnesses such as strep throat, urinary tract infections and tuberculosis.

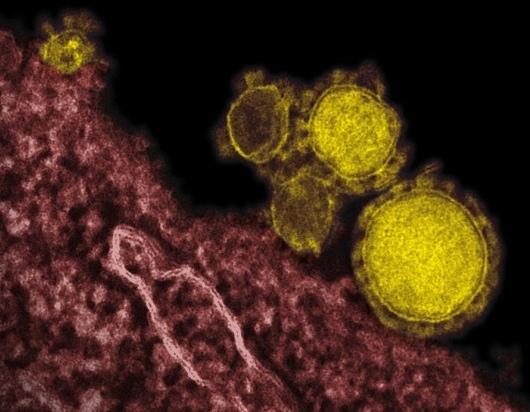

- Viruses. Even smaller than bacteria, viruses cause a multitude of diseases ranging from the common cold to AIDS.

- Fungi. Many skin diseases, such as ringworm and athlete's foot, are caused by fungi. Other types of fungi can infect your lungs or nervous system.

- Parasites. Malaria is caused by a tiny parasite that is transmitted by a mosquito bite. Other parasites may be transmitted to humans from animal feces.

Direct contact

An easy way to catch most infectious diseases is by coming in contact with a person or an animal with the infection. Infectious diseases can be spread through direct contact such as:

Person to person. Infectious diseases commonly spread through the direct transfer of bacteria, viruses or other germs from one person to another. This can happen when an individual with the bacterium or virus touches, kisses, or coughs or sneezes on someone who isn't infected.

These germs can also spread through the exchange of body fluids from sexual contact. The person who passes the germ may have no symptoms of the disease, but may simply be a carrier.

- Animal to person. Being bitten or scratched by an infected animal — even a pet — can make you sick and, in extreme circumstances, can be fatal. Handling animal waste can be hazardous, too. For example, you can get a toxoplasmosis infection by scooping your cat's litter box.

- Mother to unborn child. A pregnant woman may pass germs that cause infectious diseases to her unborn baby. Some germs can pass through the placenta or through breast milk. Germs in the vagina can also be transmitted to the baby during birth.

Indirect contact

Disease-causing organisms also can be passed by indirect contact. Many germs can linger on an inanimate object, such as a tabletop, doorknob or faucet handle.

When you touch a doorknob handled by someone ill with the flu or a cold, for example, you can pick up the germs he or she left behind. If you then touch your eyes, mouth or nose before washing your hands, you may become infected.

Insect bites

Some germs rely on insect carriers — such as mosquitoes, fleas, lice or ticks — to move from host to host. These carriers are known as vectors. Mosquitoes can carry the malaria parasite or West Nile virus. Deer ticks may carry the bacterium that causes Lyme disease.

Food contamination

Disease-causing germs can also infect you through contaminated food and water. This mechanism of transmission allows germs to be spread to many people through a single source. Escherichia coli (E. coli), for example, is a bacterium present in or on certain foods — such as undercooked hamburger or unpasteurized fruit juice.

More Information

- Ebola transmission: Can Ebola spread through the air?

- Mayo Clinic Minute: What is the Asian longhorned tick?

While anyone can catch infectious diseases, you may be more likely to get sick if your immune system isn't working properly. This may occur if:

- You're taking steroids or other medications that suppress your immune system, such as anti-rejection drugs for a transplanted organ

- You have HIV or AIDS

- You have certain types of cancer or other disorders that affect your immune system

In addition, certain other medical conditions may predispose you to infection, including implanted medical devices, malnutrition and extremes of age, among others.

Most infectious diseases have only minor complications. But some infections — such as pneumonia, AIDS and meningitis — can become life-threatening. A few types of infections have been linked to a long-term increased risk of cancer:

- Human papillomavirus is linked to cervical cancer

- Helicobacter pylori is linked to stomach cancer and peptic ulcers

- Hepatitis B and C have been linked to liver cancer

In addition, some infectious diseases may become silent, only to appear again in the future — sometimes even decades later. For example, someone who's had chickenpox may develop shingles much later in life.

Follow these tips to decrease the risk of infection:

- Wash your hands. This is especially important before and after preparing food, before eating, and after using the toilet. And try not to touch your eyes, nose or mouth with your hands, as that's a common way germs enter the body.

- Get vaccinated. Vaccination can drastically reduce your chances of contracting many diseases. Make sure to keep up to date on your recommended vaccinations, as well as your children's.

- Stay home when ill. Don't go to work if you are vomiting, have diarrhea or have a fever. Don't send your child to school if he or she has these signs, either.

Prepare food safely. Keep counters and other kitchen surfaces clean when preparing meals. Cook foods to the proper temperature, using a food thermometer to check for doneness. For ground meats, that means at least 160 F (71 C); for poultry, 165 F (74 C); and for most other meats, at least 145 F (63 C).

Also promptly refrigerate leftovers — don't let cooked foods remain at room temperature for long periods of time.

- Practice safe sex. Always use condoms if you or your partner has a history of sexually transmitted infections or high-risk behavior.

- Don't share personal items. Use your own toothbrush, comb and razor. Avoid sharing drinking glasses or dining utensils.

- Travel wisely. If you're traveling out of the country, talk to your doctor about any special vaccinations — such as yellow fever, cholera, hepatitis A or B, or typhoid fever — you may need.

- Vaccine guidance from Mayo Clinic

- Enterovirus D68 and parechovirus: How can I protect my child?

- What are superbugs and how can I protect myself from infection?

Feb 18, 2022

- Facts about infectious disease. Infectious Disease Society of America. https://www.idsociety.org/public-health/facts-about-id/. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- Jameson JL, et al., eds. Approach to the patient with an infectious disease. In: Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 20th ed. New York, N.Y.: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2018. https://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- Clean hands count for safe health care. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/features/handhygiene/index.html. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- Kumar P, et al., eds. Infectious diseases and tropical medicine. In: Kumar and Clark's Clinical Medicine. 11th ed. Philadelphia, Pa.: Elsevier; 2017. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- LaRocque R, et al. Causes of infectious diarrhea and other foodborne illnesses in resource-rich settings. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- Ryan KJ, ed. Infectious diseases: Syndromes and etiologies. In: Sherris Medical Microbiology. 7th ed. New York, N.Y.: McGraw-Hill Education; 2018. https://accessmedicine.mhmedical.com. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- File TM, et al. Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and microbiology of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 29. 2019.

- DeClerq E, et al. Approved antiviral drugs over the past 50 years. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2016;29:695.

- Mousa HAL. Prevention and treatment of influenza, influenza-like illness and common cold by herbal, complementary, and natural therapies. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine. 2017;22:166.

- Caring for someone sick. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/treatment/caring-for-someone.htm. Accessed May 29, 2019.

- Diseases & Conditions

- Infectious diseases symptoms & causes

News from Mayo Clinic

- Antibiotic use in agriculture

- Infection: Bacterial or viral?

- Monkeypox: What is it and how can it be prevented?

- Types of infectious agents

- What is chikungunya fever, and should I be worried?

CON-XXXXXXXX

Help transform healthcare

Your donation can make a difference in the future of healthcare. Give now to support Mayo Clinic's research.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Principles of Infectious Diseases: Transmission, Diagnosis, Prevention, and Control

Infectious disease control and prevention relies on a thorough understanding of the factors determining transmission. This article summarizes the fundamental principles of infectious disease transmission while highlighting many of the agent, host, and environmental determinants of these diseases that are of particular import to public health professionals. Basic principles of infectious disease diagnosis, control, and prevention are also reviewed.

Introduction

An infectious disease can be defined as an illness due to a pathogen or its toxic product, which arises through transmission from an infected person, an infected animal, or a contaminated inanimate object to a susceptible host. Infectious diseases are responsible for an immense global burden of disease that impacts public health systems and economies worldwide, disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations. In 2013, infectious diseases resulted in over 45 million years lost due to disability and over 9 million deaths ( Naghavi et al., 2015 ). Lower respiratory tract infections, diarrheal diseases, HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis (TB) are among the top causes of overall global mortality ( Vos et al., 2015 ). Infectious diseases also include emerging infectious diseases ; diseases that have newly appeared (e.g., Middle East Respiratory Syndrome) or have existed but are rapidly increasing in incidence or geographic range (e.g., extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR TB) and Zika virus ( Morse, 1995 ). Infectious disease control and prevention relies on a thorough understanding of the factors determining transmission. This article summarizes some of the fundamental principles of infectious disease transmission while highlighting many of the agent, host, and environmental determinants of these diseases that are of particular import to public health professionals.

The Epidemiological Triad: Agent–Host–Environment

A classic model of infectious disease causation, the epidemiological triad ( Snieszko, 1974 ), envisions that an infectious disease results from a combination of agent (pathogen), host, and environmental factors ( Figure 1 ). Infectious agents may be living parasites (helminths or protozoa), fungi, or bacteria, or nonliving viruses or prions. Environmental factors determine if a host will become exposed to one of these agents, and subsequent interactions between the agent and host will determine the exposure outcome. Agent and host interactions occur in a cascade of stages that include infection, disease, and recovery or death ( Figure 2(a) ). Following exposure, the first step is often colonization , the adherence and initial multiplication of a disease agent at a portal of entry such as the skin or the mucous membranes of the respiratory, digestive, or urogenital tract. Colonization, for example, with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the nasal mucosa, does not cause disease in itself. For disease to occur, a pathogen must infect (invade and establish within) host tissues. Infection will always cause some disruption within a host, but it does not always result in disease. Disease indicates a level of disruption and damage to a host that results in subjective symptoms and objective signs of illness. For example, latent TB infection is only infection – evidenced by a positive tuberculin skin test or interferon gamma release assay – but with a lack of symptoms (e.g., cough or night sweats) or signs (e.g., rales on auscultation of the chest) of disease. This is in contrast to active pulmonary TB (disease), which is accompanied by disease symptoms and signs.

The epidemiological triad model of infectious disease causation. The triad consists of an agent (pathogen), a susceptible host, and an environment (physical, social, behavioral, cultural, political, and economic factors) that brings the agent and host together, causing infection and disease to occur in the host.

Potential outcomes of host exposure to an infectious agent. (a) Following an exposure, the agent and host interact in a cascade of stages the can result in infection, disease, and recovery or death. (b) Progression from one stage to the next is dependent upon both agent properties of infectivity, pathogenicity, and virulence, and host susceptibility to infection and disease, which is in large part due to both protective and adverse effects of the host immune response.

Recovery from infection can be either complete (elimination of the agent) or incomplete. Incomplete recovery can result in both chronic infections and latent infections . Chronic infections are characterized by the continued detectable presence of an infectious agent. In contrast, latent infections are distinguished by an agent which can remain quiescent in host cells and can later undergo reactivation . For example, varicella zoster virus, the agent causing chicken pox, may reactivate many years after a primary infection to cause shingles. From a public health standpoint, latent infections are significant in that they represent silent reservoirs of infectious agent for future transmission.

Determinants of Infectious Disease

When a potential host is exposed to an infectious agent, the outcome of that exposure is dependent upon the dynamic relationship between agent determinants of infectivity , pathogenicity , and virulence , and intrinsic host determinants of susceptibility to infection and to disease ( Figure 2(b) ). Environmental factors, both physical and social behavioral, are extrinsic determinants of host vulnerability to exposure.

Agent Factors

Infectivity is the likelihood that an agent will infect a host, given that the host is exposed to the agent. Pathogenicity refers to the ability of an agent to cause disease, given infection, and virulence is the likelihood of causing severe disease among those with disease. Virulence reflects structural and/or biochemical properties of an infectious agent. Notably, the virulence of some infectious agents is due to the production of toxins ( endotoxins and/or exotoxins ) such as the cholera toxin that induces a profuse watery diarrhea. Some exotoxins cause disease independent of infection, as for example, the staphylococcal enterotoxins that can cause foodborne diseases. Agent characteristics can be measured in various ways. Infectivity is often quantified in terms of the infectious dose 50 ( ID 50 ), the amount of agent required to infect 50% of a specified host population. ID 50 varies widely, from 10 organisms for Shigella dysenteriae to 10 6 –10 11 for Vibrio cholerae ( Gama et al., 2012 ; FDA, 2012 ). Infectivity and pathogenicity can be measured by the attack rate , the number of exposed individuals who develop disease (as it may be difficult to determine if someone has been infected if they do not have outward manifestations of disease). Virulence is often measured by the case fatality rate or proportion of diseased individuals who die from the disease.

Host Factors

The outcome of exposure to an infectious agent depends, in part, upon multiple host factors that determine individual susceptibility to infection and disease. Susceptibility refers to the ability of an exposed individual (or group of individuals) to resist infection or limit disease as a result of their biological makeup. Factors influencing susceptibility include both innate, genetic factors and acquired factors such as the specific immunity that develops following exposure or vaccination. The malaria resistance afforded carriers of the sickle cell trait exemplifies how genetics can influence susceptibility to infectious disease ( Aidoo et al., 2002 ). Susceptibility is also affected by extremes of age, stress, pregnancy, nutritional status, and underlying diseases. These latter factors can impact immunity to infection, as illustrated by immunologically naïve infant populations, aging populations experiencing immune senescence, and immunocompromised HIV/AIDS patients.

Mechanical and chemical surface barriers such as the skin, the flushing action of tears, and the trapping action of mucus are the first host obstacles to infection. For example, wound infection and secondary sepsis are serious complications of severe burns which remove the skin barrier to microbial entry. Lysozyme, secreted in saliva, tears, milk, sweat, and mucus, and gastric acid have bactericidal properties, and vaginal acid is microbicidal for many agents of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Microbiome-resident bacteria (a.k.a. commensal bacteria, normal flora ) can also confer host protection by using available nutrients and space to prevent pathogenic bacteria from taking up residence.

The innate and adaptive immune responses are critical components of the host response to infectious agents ( Table 1 ). Each of these responses is carried out by cells of a distinct hematopoietic stem cell lineage: the myeloid lineage gives rise to innate immune cells (e.g., neutrophils, macrophages, dendritic cells) and the lymphoid lineage gives rise to adaptive immune cells (e.g., T cells, B cells). The innate immune response is an immediate, nonspecific response to broad groups of pathogens. By contrast, the adaptive immune response is initially generated over a period of 3–4 days, it recognizes specific pathogens, and it consists of two main branches: (1) T cell-mediated immunity (a.k.a. cell-mediated immunity) and (2) B cell-mediated immunity (a.k.a. humoral or antibody-mediated immunity). The innate and adaptive responses also differ in that the latter has memory, whereas the former does not. As a consequence of adaptive immune memory , if an infectious agent makes a second attempt to infect a host, pathogen-specific memory T cells, memory B cells, and antibodies will mount a secondary immune response that is much more rapid and intense than the initial, primary response and, thus, better able to inhibit infection and disease. Immune memory is the basis for the use of vaccines that are given in an attempt to stimulate an individual's adaptive immune system to generate pathogen-specific immune memory. Of note, in some cases the response of the immune system to an infectious agent can contribute to disease progress. For example, immunopathology is thought to be responsible for the severe acute disease that can occur following infection with a dengue virus that is serotypically distinct from that causing initial dengue infection ( Screaton et al., 2015 ).

Table 1

Comparison of innate and adaptive immunity

| Innate Immune Response | Adaptive Immune Response |

|---|---|

| Immediate response; initiated within seconds | Gradual response; initially generated over 3–4 days (primary response) |

| Targets groups of pathogens | Targets-specific pathogens |

| No memory | Memory |

An immune host is someone protected against a specific pathogen (because of previous infection or vaccination) such that subsequent infection will not take place or, if infection does occur, the severity of disease is diminished. The duration and efficacy of immunity following immunization by natural infection or vaccination varies depending upon the infecting agent, quality of the vaccine, type of vaccine (i.e., live or inactivated virus, subunit, etc.), and ability of the host to generate an immune response. For example, a single yellow fever vaccination appears to confer lifelong immunity, whereas immune protection against tetanus requires repeat vaccination every 10 years ( Staples et al., 2015 ; Broder et al., 2006 ). In malaria-endemic areas, natural immunity to malaria usually develops by 5 years of age and, while protective from severe disease and death, it is incomplete and short-lived ( Langhorne et al., 2008 ).

Functionally, there are two basic types of immunization, active and passive. Active immunization refers to the generation of immune protection by a host's own immune response. In contrast, passive immunization is conferred by transfer of immune effectors, most commonly antibody (a.k.a. immunoglobulin, antisera ), from a donor animal or human. For example, after exposure to a dog bite, an individual who seeks medical care will receive both active and passive postexposure immune prophylaxis consisting of rabies vaccine (to induce the host immune response) and rabies immune globulin (to provide immediate passive protection against rabies). An example of natural passive immunization is the transfer of immunity from mother to infant during breastfeeding.

Vaccination does not always result in active immunization; failure of vaccination can be due to either host or vaccine issues. Individuals who are immunosuppressed as, for example, a result of HIV infection, malnutrition, immunosuppressive therapy, or immune senescence might not mount a sufficient response after vaccination so as to be adequately immunized (protected). Similarly, vaccination with an inadequate amount of vaccine or a vaccine of poor quality (e.g., due to break in cold chain delivery) might prevent even a healthy individual from becoming immunized.

Environmental Factors

Environmental determinants of vulnerability to infectious diseases include physical, social, behavioral, cultural, political, and economic factors. In some cases, environmental influences increase risk of exposure to an infectious agent. For example, following an earthquake, environmental disruption can increase the risk of exposure to Clostridium tetani and result in host traumatic injuries that provide portals of entry for the bacterium. Environmental factors promoting vulnerability can also lead to an increase in susceptibility to infection by inducing physiological changes in an individual. For example, a child living in a resource-poor setting and vulnerable to malnutrition may be at increased risk of infection due to malnutrition-induced immunosuppression. Table 2 provides examples of some of the many environmental factors that can facilitate the emergence and/or spread of specific infectious diseases.

Table 2

Environmental factors facilitating emergence and/or spread of specific infectious diseases

| Environmental factor facilitating transmission | Mechanism | Disease | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate/weather | EI Niño- persistent, above-normal rainfall EI Niño-persistent, above-normal rainfall Flooding | Increased vegetation promoting increase in rodent reservoir Expansion of vertically infected mosquitoes and secondary vectors Promotes exposure to contaminated rat urine and water | Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome Rift Valley fever Leptospirosis, cholera | |

| Natural disaster | Tsunami, earthquake Tornado | Environmental disruption promoting exposure Environmental disruption promoting exposure | Tetanus Cutaneous mucormycosis | |

| Infrastructure | Engineering infrastructure Water treatment plant Engineered water systems | Defective plumbing promoting viral dispersal Inadequate microbial barriers Reservoir and distribution | SARS Cryptosporidiosis Legionellosis | |

| Development/change in land use | Water resource development and management Water resource development and management Water resource development and management Forest fragmentation Deforestation Deforestation | Dams, irrigation schemes, mining expanding intermediate host habitat Dams, irrigation schemes expanding vector habitat Expansion of irrigated rice farming creating vector breeding sites Loss of biodiversity expanding natural reservoir Creation of vector breeding sites Driving contact with reservoir host | Schistosomiasis Malaria Japanese encephalitis Lyme Malaria Hendra | |

| Technology and industry | Medical technology Medical technology Food processing Globilization of food industry Food storage Crop introduction Animal husbandry | Inappropriate use of antibiotics driving genetic change Transfusion of contaminated blood Undercooked hamburger Transport contaminated seed from Egypt to Germany and France Improper storage of maize Maize cultivation promoting vector abundance Small-scale poultry farming facilitating animal-to-human virus transfer | Antibiotic-resistant infections Chagas O157:H7 outbreak O104:H4 outbreak Acute aflatoxicosis Malaria H5N1 avian influenza | |

| Travel and commerce | Visiting friends and family Recreational Commercial Commercial | Import of virus Exposure while rafting, kayaking Import of infected animals Contamination ice cream premix during tanker trailer transport | Chikungunya Schistosomiasis Monkeypox Salmonellosis | |

| Politics | Government response | Denial of viral etiology epidemic | HIV/AIDS | |

| Economics | Low income Resource-poor environment Poor urban environment | Lack of protection against vector Inadequate WASH promoting transmission Poor WASH promoting vector expansion | Dengue Trachoma Lymphatic filariasis | |

| War and conflict | Displaced persons camps Displaced persons camps | Inadequate WASH Inadequate WASH | Cholera Cutaneous leishmaniasis | |

| Social/behavioral | Injection drug use Sexual practices Cultural practices Consumptive behaviors Forest encroachment, bushmeat hunting Live-animal markets | Sharing contaminated injection equipment High-risk sexual behavior among truckers Unsafe burial practices Consumption of raw or undercooked marine fish or squid Exposure to infected bush animals Close contact facilitating animal virus jumping species to humans | Hepatitis C HIV-1 infection Ebola Anisakidosis Ebola SARS | |

WASH, water, sanitation, and hygiene; E. coli , Escherichia coli ; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome.

Transmission Basics

A unique characteristic of many infectious diseases is that exposure to certain infectious agents can have consequences for other individuals, because an infected person can act as a source of exposure. Some pathogens (e.g., STI agents) are directly transmitted to other people, while others (e.g., vectorborne disease (VBD) agents) are transmitted indirectly.

From a public health standpoint, it is useful to define stages of an infectious disease with respect to both clinical disease and potential for transmission ( Figure 3 ). With respect to disease, the incubation period is defined as the time from exposure to an infectious agent until the time of first signs or symptoms of disease. The incubation period is followed by the period of clinical illness which is the duration between first and last disease signs or symptoms. With respect to transmission of an infectious agent, the latent (preinfectious) period is the duration of time between exposure to an agent and the onset of infectiousness. It is followed by the infectious period (a.k.a. period of communicability ) which is the time period when an infected person can transmit an infectious agent to other individuals. In parasitic infections, the latent and infectious periods are commonly referred to as the prepatent period and patent period , respectively.

Stages of infectious disease. The stages of an infectious disease can be identified with relation to signs and symptoms of illness in the host (incubating and clinically ill), and the host's ability to transmit the infectious agent (latent and infectious). The red bar indicates when an individual is infectious but asymptomatic. The relationship between stages is an important determinant of carrier states and, thus, the ease of spread of an infectious disease through a population. (a) Patients infected with Ebola virus do not become infectious until they show signs of disease. (b) In some cases, varicella (chicken pox)-infected individuals can act as incubatory carriers and become infectious before the onset of symptoms (e.g., rash). (c) Some patients with Vibrio cholerae infection remain infectious as convalescent carriers after recovery. (d) Salmonella Typhi infection can result in an apparently healthy carrier that never shows signs or symptoms of disease.

The duration of disease stages is unique for each type of infection and it can vary widely for a given type of infection depending upon agent, host, and environmental factors that affect, for example, dose of the inoculated agent, route of exposure, host susceptibility, and agent infectivity and virulence. Knowledge of the timing of disease stages is of key importance in the design of appropriate control and prevention strategies to prevent the spread of an infectious disease. For example, efforts to control the recent Ebola West Africa outbreak through contact tracing and quarantine were based on knowledge that the infectious period for Ebola does not begin until the start of the period of clinical illness, which occurs up to 21 days following exposure ( Figure 3(a) ; Pandey et al., 2014 ).

A carrier is, by definition, an infectious individual who is not showing clinical evidence of disease and, thus, might unknowingly facilitate the spread of an infectious agent through a population. Incubatory carriers exist when the incubation period overlaps with the infectious period, as can occur in some cases of chicken pox ( Figure 3(b) ). Convalescent carriers occur when the period of infectiousness extends beyond the period of clinical illness ( Figure 3(c) ). Carriers of this type can be a significant issue in promoting the spread of certain enteric infections, such as those caused by the bacterium, V. cholerae . Healthy carriers , infected individuals that remain asymptomatic but are capable of transmitting an infectious agent, occur commonly with many infectious diseases (e.g., meningococcal meningitis and typhoid fever) and are also significant challenges to disease control ( Figure 3(d) ).

Dynamics of Infectious Diseases within Populations

A variety of terms are used to describe the occurrence of an infectious disease within a specific geographic area or population. Sporadic diseases occur occasionally and unpredictably, while endemic diseases occur with predictable regularity. Levels of endemicity can be classified as holoendemic , hyperendemic , mesoendemic , or hypoendemic depending upon whether a disease occurs with, respectively, extreme, high, moderate, or low frequency. For some infectious diseases, such as malaria, levels of endemicity are well defined and used as parameters for identifying disease risk and implementing control activities. Malaria endemicity is quantified based upon rates of palpable enlarged spleens in a defined (usually pediatric) age group: holoendemic >75%, hyperendemic 51–75%, mesoendemic 11–50%, and hypoendemic <10% ( Hay et al., 2008 ). An epidemic refers to an, often acute, increase in disease cases above the baseline level. An epidemic may reflect an escalation in the occurrence of an endemic disease or the appearance of a disease that did not previously exist in a population. The term outbreak is often used synonymously with epidemic but can occasionally refer to an epidemic occurring in a more limited geographical area; for example, a foodborne illness associated with a group gathering. By contrast, a pandemic is an epidemic that has spread over a large geographic region, encompassing multiple countries or continents, or extending worldwide. Influenza commonly occurs as a seasonal epidemic, but periodically it gives rise to a global pandemic, as was the case with 2009 H1N1 influenza.

Two fundamental measures of disease frequency are prevalence and incidence . Prevalence is an indicator of the number of existing cases in a population as it describes the proportion of individuals who have a particular disease, measured either at a given point in time (point prevalence) or during a specified time period (period prevalence). In contrast, incidence (a.k.a. incidence rate ) is a measurement of the rate at which new cases of a disease occur (or are detected) in a population over a given time period. Usually measured as a proportion (number infected/number exposed), attack rates are often calculated during an outbreak. In some circumstances, a secondary attack rate is calculated to quantify the spread of disease to susceptible exposed persons from an index case (the case first introducing an agent into a setting) in a circumscribed population, such as in a household or hospital. During the 2003 SARS epidemic, secondary attack rates in Toronto hospitals were high but varied from 25% to 40% depending upon the hospital ward ( CDC, 2003b ).

The basic reproductive number ( basic reproductive ratio; R 0 ) is a measure of the potential for an infectious disease to spread through an immunologically naïve population. It is defined as the average number of secondary cases generated by a single, infectious case in a completely susceptible population. In reality, for most infectious diseases entering into a community, some proportion of the population is usually immune (and nonsusceptible) due to previous infection and/or immunization. Thus, a more accurate reflection of the potential for community disease spread is the effective reproductive number ( R ) which measures the average number of new infections due to a single infection. In general, for an epidemic to occur in a population, R must be >1 so that the number of cases continues to increase.

Herd immunity (a.k.a. community immunity) refers to population-level resistance to an infectious disease that occurs when there are enough immune individuals to block the chain of infection/transmission . As a result of herd immunity, susceptible individuals who are not immune themselves are indirectly protected from infection ( Figure 4 ). Vaccine hesitancy, the choice of individuals or their caregivers to delay or decline vaccination, can lead to overall lower levels of herd immunity. Outbreaks of measles in the United States, including a large 2014 measles outbreak at an amusement park in California, highlight the phenomena of vaccine refusal and associated increased risk for vaccine-preventable diseases among both nonvaccinated and fully vaccinated (but not fully protected) individuals ( Phadke et al., 2016 ).

Herd immunity occurs when one is protected from infection by immunization occurring in the community. Using influenza as an example, the top box shows a population with a few infected individuals (shown in red) and the rest healthy but unimmunized (shown in blue); influenza spreads easily through the population. The middle box depicts the same population but with a small number who are immunized (shown in yellow); those who are immunized do not become infected, but a large proportion of the population becomes infected. In the bottom box, a large proportion of the population is immunized; this prevents significant transmission, including to those who are unimmunized.

An important public health consequence of herd immunity is that immunization coverage does not need to be 100% for immunization programs to be successful. The equation R = R 0 (1 − x) (where x equals the immune portion of the population) indicates the level of immunization required to prevent the spread of an infectious disease through a population. The proportion that needs to be immunized depends on the pathogen ( Table 3 ). When the proportion immunized (x) reaches a level such that R < 1, a chain of infection cannot be sustained. Thus, Ro and R can be used to calculate the target immunization coverage needed for the success of vaccination programs.

Table 3

Herd immunity thresholds for selected infectious diseases

| Disease | Ro | Herd immunity threshold (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Diphtheria | 6–7 | 83–86 |

| Ebola (West Africa) | 1.5–2.5 | 33–60 |

| Measles | 12–18 | 92–94 |

| Mumps | 4–7 | 75–86 |

| Polio | 5–7 | 80–86 |

| Rubella | 6–7 | 83–85 |

| Smallpox | 5–7 | 80–85 |

Infectious Disease Diagnosis

Proper diagnosis of infectious illnesses is essential for both appropriate treatment of patients and carrying out prevention and control surveillance activities. Two important properties that should be considered for any diagnostic test utilized are sensitivity and specificity. Sensitivity refers to the ability of the test to correctly identify individuals infected with an agent (‘positive in disease’). A test that is very sensitive is more likely to pick up individuals with the disease (and possibly some without the disease); a very sensitive test will have few false negatives . Specificity is the ability of the test to correctly identify individuals not infected by a particular agent (‘negative in health’); high specificity implies few false positives . Often, screening tests are highly sensitive (to capture any possible cases), and confirmatory tests are more specific (to rule out false-positive screening tests).

Broadly, laboratory diagnosis of infectious diseases is based on tests that either directly identify an infectious agent or provide evidence that infection has occurred by documenting agent-specific immunity in the host ( Figure 5 ). Identification of an infecting agent involves either direct examination of host specimens (e.g., blood, tissue, urine) or environmental specimens, or examination following agent culture and isolation from such specimens. The main categories of analyses used in pathogen identification can be classified as phenotypic , revealing properties of the intact agent, nucleic acid-based , determining agent nucleic acid (DNA or RNA) characteristics and composition, and immunologic , detecting microbial antigen or evidence of immune response to an agent ( Figure 5 ). Direct phenotypic analyses include both macroscopic and/or microscopic examination of specimens to determine agent morphology and staining properties. Cultured material containing large quantities of agent can undergo analyses to determine characteristics, such as biochemical enzymatic activity (enzymatic profile) and antimicrobial sensitivity , and to perform phage typing , a technique which differentiates bacterial strains according to the infectivity of strain-specific bacterial viruses (a.k.a. bacteriophages). Nucleic acid–based tests often make use of the polymerase chain reaction ( PCR ) to amplify agent DNA or complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesized from messenger RNA (mRNA). The ability of pathogen-specific PCR primers to generate an amplification product can confirm or rule out involvement of a specific pathogen. Sequencing of amplified DNA fragments can also assist with pathogen identification. Restriction fragment analysis , as by pulse-field gel electrophoresis of restriction enzyme-digested genomic DNA isolated from cultured material, can yield distinct ‘DNA fingerprints’ that can be used for comparing the identities of bacteria. The CDC PulseNet surveillance program uses DNA fingerprinting as the basis for detecting and defining foodborne disease outbreaks that can sometimes be quite widely dispersed ( CDC, 2013 ). Most recently, next-generation sequencing technologies have made whole-genome sequencing a realistic subtyping method for use in foodborne outbreak investigation and surveillance ( Deng et al., 2016 ). The objective of immunologic analysis of specimens is to reveal evidence of an agent through detection of its antigenic components with agent-specific antibodies. Serotyping refers to the grouping of variants of species of bacteria or viruses based on shared surface antigens that are identified using immunologic methodologies such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay ( ELISA ) and Western blotting .

Methods of infectious disease diagnosis. Laboratory methods for infectious disease diagnosis focus on either analyzing host specimens or environmental samples for an agent (upper section), or analyzing the host for evidence of immunity to an agent (lower section). Closed solid bullets, category of test; open bullets, examples of tests. PCR, polymerase chain reaction; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; PFGE, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis.

Immunologic assays are also used to look for evidence that an agent-specific immune response has occurred in an exposed or potentially exposed individual. Serologic tests detect pathogen-specific B cell–secreted antibodies in serum or other body fluids. Some serologic assays simply detect the ability of host antibodies to bind to killed pathogen or components of pathogen (e.g., ELISA). Others rely on the ability of antibodies to actually neutralize the activity of live microbes; as, for example, the plaque reduction neutralization test which determines the ability of serum antibodies to neutralize virus. Antibody titer measures the amount of a specific antibody present in serum or other fluid, expressed as the greatest dilution of serum that still gives a positive test in whatever assay is being employed. Intradermal tests for identification of T cell–mediated immediate type (Type I) hypersensitivity or delayed type (Type IV) hypersensitivity responses to microbial antigen can be used to diagnose or support the diagnosis of some bacterial, fungal, and parasitic infections, such as, the Mantoux (tuberculin) test for TB.

Infectious Disease Control and Prevention

Based on the classic model of Leavell and Clark (1965) , infectious disease prevention activities can be categorized as primary, secondary, or tertiary. Primary prevention occurs at the predisease phase and aims to protect populations, so that infection and disease never occur. For example, measles immunization campaigns aim to decrease susceptibility following exposure. The goal of secondary prevention is to halt the progress of an infection during its early, often asymptomatic stages so as to prevent disease development or limit its severity; steps important for not only improving the prognosis of individual cases but also preventing infectious agent transmission. For example, interventions for secondary prevention of hepatitis C in injection drug user populations include early diagnosis and treatment by active surveillance and screening ( Miller and Dillon, 2015 ). Tertiary prevention focuses on diseased individuals with the objective of limiting impact through, for example, interventions that decrease disease progression, increase functionality, and maximize quality of life. Broadly, public health efforts to control infectious diseases focus on primary and secondary prevention activities that reduce the potential for exposure to an infectious agent and increase host resistance to infection. The objective of these activities can extend beyond disease control , as defined by the 1997 Dahlem Workshop on the Eradication of Infectious Diseases, to reach objectives of elimination and eradication ( Dowdle, 1998 ; Box 1 ).

Box 1

Hierarchy of public health efforts targeting infectious diseases.

The 1997 Dahlem Workshop on the Eradication of Infectious Diseases defined a continuum of outcomes due to public health interventions targeting infectious diseases: “1) control , the reduction of disease incidence, prevalence, morbidity or mortality to a locally acceptable level as a result of deliberate efforts; continued intervention measures are required to maintain the reduction (e.g. diarrheal diseases), 2) elimination of disease , reduction to zero of the incidence of a specified disease in a defined geographical area as a result of deliberate efforts; continued intervention measures are required (e.g. neonatal tetanus), 3) elimination of infections , reduction to zero of the incidence of infection caused by a specific agent in a defined geographical area as a result of deliberate efforts; continued measures to prevent re-establishment of transmission are required (e.g. measles, poliomyelitis),4) eradication , permanent reduction to zero of the worldwide incidence of infection caused by a specific agent as a result of deliberate efforts; intervention measures are no longer needed (e.g. smallpox), and 5) extinction, the specific infectious agent no longer exists in nature or in the laboratory (e.g. none)” ( Dowdle, 1998 ).

As noted earlier, the causation and spread of an infectious disease is determined by the interplay between agent, host, and environmental factors. For any infectious disease, this interplay requires a specific linked sequence of events termed the chain of infection or chain of transmission ( Figure 6 ). The chain starts with the infectious agent residing and multiplying in some natural reservoir ; a human, animal, or part of the environment such as soil or water that supports the existence of the infectious agent in nature. The infectious agent leaves the reservoir via a portal of exit and, using some mode of transmission , moves to reach a portal of entry into a susceptible host . A thorough understanding of the chain of infection is crucial for the prevention and control of any infectious disease, as breaking a link anywhere along the chain will stop transmission of the infectious agent. Often more than one intervention can be effective in controlling a disease, and the approach selected will depend on multiple factors such as economics and ease with which an intervention can be executed in a given setting. It is important to realize that the potential for rapid and far-reaching movement of infectious agents that has accompanied globalization means that coordination of intervention activities within and between nations is required for optimal prevention and control of certain diseases.

The chain of infection (a.k.a. chain of transmission). One way to visualize the transmission of an infectious agent though a population is through the interconnectedness of six elements linked in a chain. Public health control and prevention efforts focus on breaking one or more links of the chain in order to stop disease spread.

The Infectious Agent and Its Reservoir

The cause of any infectious disease is the infectious agent . As discussed earlier, many types of agents exist, and each can be characterized by its traits of infectivity, pathogenicity, and virulence. A reservoir is often, but not always, the source from which the agent is transferred to a susceptible host. For example, bats are both the reservoir for Marburg virus and a source of infection for humans and bush animals including African gorillas. However, because morbidity and mortality due to Marburg infection is significant among these bush animals, they cannot act as a reservoir to sustain the virus in nature (they die too quickly), although they can act as a source to transmit Marburg to humans.

Infectious agents can exist in more than one type of reservoir . The number and types of reservoirs are important determinants of how easily an infectious disease can be prevented, controlled, and, in some cases, eliminated or eradicated. Animal, particularly wild animal, reservoirs, and environmental reservoirs in nature can be difficult to manage and, thus, can pose significant challenges to public health control efforts. In contrast, infectious agents that only occur in human reservoirs are among those most easily targeted, as illustrated by the success of smallpox eradication.

Humans are the reservoir for many common infectious diseases including STIs (e.g., HIV, syphilis) and respiratory diseases (e.g., influenza). Humans also serve as a reservoir, although not always a primary reservoir, for many neglected tropical diseases ( NTDs ) as, for example, dracunculiasis (a.k.a. Guinea worm). From a public health standpoint, an important feature of human reservoirs is that they might not show signs of illness and, thus, can potentially act as unrecognized carriers of disease within communities. The classic example of a human reservoir is the cook Mary Mallon (Typhoid Mary); an asymptomatic chronic carrier of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi who was linked to at least 53 cases of typhoid fever ( Soper, 1939 ).

Animals are a reservoir for many human infectious diseases. Zoonosis is the term used to describe any infectious disease that is naturally transmissible from animals to humans. These diseases make up approximately 60% of all infectious diseases, and an estimated 75% of recently emerging infectious diseases ( Burke et al., 2012 ). Zoonotic reservoirs and sources of human disease agents include both domestic (companion and production) animals (e.g., dogs and cows) and wildlife. Control and prevention of zoonotic diseases requires the concerted efforts of professionals of multiple disciplines and is the basis for what has become known as the One Health approach ( Gibbs, 2014 ). This approach emphasizes the interconnectedness of human health, animal health, and the environment and recognizes the necessity of multidisciplinary collaboration in order to prevent and respond to public health threats.

Inanimate matter in the environment, such as soil and water, can also act as a reservoir of human infectious disease agents. The causative agents of tetanus and botulism ( Clostridium tetani and C. botulinum ) are examples of environmental pathogens that can survive for years within soil and still remain infectious to humans. Legionella pneumophila , the etiologic agent of Legionnaires' disease, is part of the natural flora of freshwater rivers, streams, and other bodies. However, the pathogen particularly thrives in engineered aquatic reservoirs such as cooling towers, fountains, and central air conditioning systems, which provide conditions that promote bacterial multiplication and are frequently linked to outbreaks. Soil and water are also sources of infection for several protozoa and helminth species which, when excreted by a human reservoir host, can often survive for weeks to months. Outbreaks of both cryptosporidiosis and giardiasis commonly occur during summer months as a result of contact with contaminated recreational water. Soil containing roundworm ( Ascaris lumbricoides ) eggs is an important source of soil-transmitted helminth infections in children.

Targeting the Agent and Reservoir

Early steps in preventing exposure to an infectious agent include interventions to control or eliminate the agent within its reservoir, to neutralize or destroy the reservoir, and/or to stop the agent from exiting its reservoir. Central to these interventions are surveillance activities that routinely identify disease agents within reservoirs. When humans are the reservoir, or source, of an infectious agent, early and rapid diagnosis and treatment are key to decreasing the duration of infection and risk of transmission. Both active surveillance and passive surveillance are used to detect infected cases and carriers. Some readily communicable diseases, such as Ebola, can require isolation of infected individuals to minimize the risk of transmission. As part of the global effort to eradicate dracunculiasis, several endemic countries have established case containment centers to provide treatment and support to patients with emerging Guinea worms to keep them from contaminating water sources and, thereby, exposing others ( Hochberg et al., 2008 ). Contact tracing and quarantine are other activities employed in the control of infections originating from a human reservoir or source. During the West Africa Ebola outbreak, key control efforts focused on the tracing and daily follow-up of healthy individuals who had come in contact with Ebola patients and were potentially infected with the virus ( Pandey et al., 2014 ).

One Health emphasizes the importance of surveillance and monitoring for zoonotic pathogens in animal populations. For some diseases (e.g., Rift Valley fever) epizootics (analogous to epidemics, but in animal populations) can actually serve as sentinel events for forecasting impending human epidemics. Once animal reservoirs (and sources) of infection are identified, approaches to prevention and control include reservoir elimination and prevention of reservoir infection. Zoonotic diseases exist in nature in predictably regular, enzootic cycles and/or epizootic cycles and are transmitted to humans via distinct pathways. The focus of prevention and control activities for these diseases reflects the extent to which a zoonotic pathogen has evolved to become established in human populations ( Wolfe et al., 2007 ). For some zoonotic diseases (e.g. anthrax, Nipah, rabies), primary transmission always occurs from animals, with humans acting as incidental (dead end) hosts; control of these diseases thus concentrates on preventing animal-to-animal and, ultimately, animal-to-human transmission. Currently, most human cases of avian influenza are the result of human infection from birds; human-to-human transmission is extremely rare. Thus, reservoir elimination by culling infected poultry flocks is a recommended measure for controlling avian influenza in birds and preventing sporadic infection of humans ( CDC, 2015 ). Other zoonotic diseases demonstrate varying degrees of secondary human-to-human transmission following primary transmission (a.k.a. spillover) from animals. Both rates of spillover and the ability to sustain human-to-human transmission can vary widely between zoonoses and, in consequence, control strategies can also be quite different. For example, outbreaks of Ebola arise following an initial bush animal-to-human transmission event, and subsequent human-to-human transmission is often limited ( Feldmann and Geisbert, 2011 ). In contrast, the four dengue viruses originally emerged from a sylvatic cycle between non-human primates and mosquitoes, and are now sustained by a continuous human-mosquito-human cycle of transmission with outbreaks occurring as a result of infected individuals entering into naïve populations ( Vasilakis et al., 2011 ). Thus, while Ebola outbreak prevention efforts would include limiting contact with bush animals, such efforts would not be useful for prevention of dengue outbreaks. HIV is an example of a virus that emerged from an ancestral animal virus, simian immunodeficiency virus, but has evolved so that it is now HIV is an example of a virus that emerged from an ancestral animal virus, simian immunodeficiency virus, but has evolved so that it is now only transmitted human to human ( Faria et al., 2014 ).

Portal of Exit

Infectious agents exit human and animal reservoirs and sources via one of several routes which often reflect the primary location of disease; respiratory disease agents (e.g., influenza virus) usually exit within respiratory secretions, whereas gastrointestinal disease agents (e.g., rotavirus, Cryptosporidium spp.) commonly exit in feces. Other portals of exits include sites from which urine, blood, breast milk, and semen leave the host.

For some infectious diseases, infection can naturally occur as a result of contact with more than one type of bodily fluid, each of which uses a different portal of exit. While infection with the SARS virus most frequently occurred via contact with respiratory secretions, a large community outbreak was caused by the spread of virus in a plume of diarrhea ( Yu et al., 2004 ). Control interventions targeting portals of exit and entry are discussed below.

Modes of Transmission

There are a variety of ways in which infectious agents move from a natural reservoir to a susceptible host, and several different classification schemes are used. The scheme below categorizes transmission as direct transmission , if the infective form of the agent is transferred directly from a reservoir to an infected host, and indirect transmission , if transfer takes place via a live or inanimate intermediary ( Box 2 ).

Box 2

Modes of transmission of infectious agents.

Modes of Direct Transmission (infective form of agent transferred directly from reservoir or host):

- 1. Direct contact

- 2. Direct spread of droplets

- 3. Direct exposure to an infectious agent in the environment

- 5. Transplacental/perinatal

Modes of Indirect Transmission (infective form of agent transferred indirectly from reservoir or infected host):

- • Biological vector

- • Intermediate host

- • Mechanical vector

- • Vehicle

- 3. Airborne

Modes of Direct Transmission

Direct physical contact between the skin or mucosa of an infected person and that of a susceptible individual allows direct transfer of infectious agents. This is a mode of transmission for most STIs and many other infectious agents, such as bacterial and viral conjunctivitis (a.k.a. pink eye) and Ebola virus disease.

Direct droplet transmission occurs after sneezing, coughing, or talking projects a spray of agent-containing droplets that are too large to remain airborne over large distances or for prolonged periods of time. The infectious droplets traverse a space of generally less than 1 m to come in contact with the skin or mucosa of a susceptible host. Many febrile childhood diseases, including the common cold, are transferred this way.

Diseases spread by direct contact and droplet transmission require close proximity of infected and susceptible individuals and, thus, commonly occur in settings such as households, schools, institutions of incarceration, and refugee/displaced person camps. Infectious agents spread exclusively in this manner are often unable to survive for long periods outside of a host; direct transmission helps to ensure transfer of a large infective dose.

Direct contact to an agent in the environment is a means of exposure to infectious agents maintained in environmental reservoirs. Diseases commonly transmitted in this manner include those in which the infectious agent enters a susceptible host via inhalation (e.g., histoplasmosis) or through breaks in the skin following a traumatic event (e.g., tetanus).

Animal bites are another way in which some infectious agents are directly transferred, through broken skin. This is the most common means of infection with rabies virus.

Transplacental (a.k.a. congenital, vertical ) and perinatal transmissions occur during pregnancy and delivery or breastfeeding, respectively. Classic examples include mother-to-child transmission of the protozoa Toxoplasma gondii during pregnancy, HIV during pregnancy, delivery, or breastfeeding, and Zika virus during pregnancy ( Rasmussen et al., 2016 ).

Targeting Directly Transmitted Infectious Diseases

Case finding and contact tracing are public health prevention and control activities aimed at stopping the spread of infectious diseases transmitted by either direct contact or direct spread of droplets. Once identified, further activities to limit transmission to susceptible individuals can involve definitive diagnosis, treatment, and, possibly, isolation of active cases and carriers, and observation, possible quarantine, or prophylactic vaccination or treatment of contacts. Patient education is an important feature of any communicable infectious disease control effort. Environmental changes, such as decreasing overcrowded areas and increasing ventilation, can also contribute to limiting the spread of some infectious diseases, particularly respiratory diseases.

Central to prevention of transplacental and perinatal infectious disease transmission is avoidance of maternal infection and provision of early diagnosis and treatment of infected women prior to or during pregnancy. For example, public health efforts targeting congenital toxoplasmosis focus on preventing pregnant women from consuming undercooked meat or contacting cat feces that may be contaminated. Current WHO guidelines for prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission recommend that HIV-infected pregnant and breastfeeding women should be maintained on antiretrovirals ( WHO, 2013 ).

Modes of Indirect Transmission

There are three main categories of indirect transmission: biological, mechanical, and airborne. Box 3 provides definitions of the different types of hosts, vectors, and vehicles involved in the life cycle of agents that are transmitted indirectly.

Box 3

Hosts, vectors, and vehicles involved in the life cycle of infectious agents transmitted indirectly.

Definitive host : A host in which a parasite reproduces sexually. Humans are definitive hosts for roundworms. By strict definition, mosquitoes are the definitive host of malaria as they are the organism in which sexual reproduction of the agent protozoa, Plasmodium spp., occurs.

Reservoir host : A host that serves to sustain an infectious pathogen as a potential source of infection for transmission to humans. Note that a reservoir host will not succumb to infection. Lowland gorillas and chimpanzees can be infected by Ebola virus, but they are not a reservoir host as they suffer devastating losses from infection. Bats are a suspected reservoir for Ebola virus.

Intermediate host : A host in which larval or intermediate stages of an infectious agent develop but sexual reproduction does not take place. An intermediate host does not directly transfer an agent to the definitive host. Snails are an intermediate host in the lifecycle of Schistosoma spp.

Dead-end host : A host from which infectious agents cannot be transmitted to other susceptible hosts. Humans are a dead-end host for West Nile virus which normally circulates between mosquitoes and certain avian species.

Vector : A generic term for a living organism (e.g., biological vector or intermediate host) involved in the indirect transmission of an infectious agent from a reservoir or infected host to a susceptible host.

Biological vector : A vector (often arthropod) in which an infectious organism must develop or multiply before the vector can transmit the organism to a susceptible host. Aedes spp. mosquitoes are a biological vector for dengue, chikungunya, and Zika.

Mechanical vector : A vector (often arthropod) that transmits an infectious organism from one host to another but is not essential to the life cycle of the organism. The house fly is a mechanical vector in the diarrheal disease shigellosis as it carries feces contaminated with the Shigella spp. bacterium to a susceptible person.

Vehicles : Inanimate objects that serve as an intermediate in the indirect transmission of a pathogen from a reservoir or infected host to a susceptible host. These include food, water, and fomites such as doorknobs, surgical instruments, and used needles.

Biological transmission occurs when multiplication and/or development of a pathogenic agent within a vector (e.g., biological vector or intermediate host ) is required for the agent to become infectious to humans. The time that is necessary for these events to occur is known as the extrinsic incubation period ; in contrast to the intrinsic incubation period which is the time required for an exposed human host to become infectious. Indirect transmission by mosquito vectors is the primary mode of transmission of a large number of viruses (arthropod-borne viruses or arboviruses) of public health concern (e.g., West Nile, Zika). A number of NTDs are also transmitted by biological vectors including lymphatic filariasis (a.k.a. elephantiasis) by mosquitoes. Ticks are biological vectors for many bacterial etiological agents (e.g., Lyme disease and ehrlichiosis), and the parasitic agent causing babesiosis. The infectious agent of the helminthic NTDs, schistosomiasis, and dracunculiasis are transmitted indirectly via intermediate freshwater snail and copepod hosts, respectively.

Mechanical transmission does not require pathogen multiplication or development within a living organism. It occurs when an infectious agent is physically transferred by a live entity ( mechanical vector ) or inanimate object ( vehicle ) to a susceptible host. Classic examples of diseases spread by mechanical vector transmission are shigellosis (transmission of Shigella spp. on the appendages of flies) and plague (transmission of Yersinia pestis by fleas). Many diarrheal diseases are transmitted by the fecal-oral route with food and water often acting as vehicles ( Figure 7 ). Other types of vehicles for infectious disease agents are biologic products (e.g., blood, organs for transplant) and fomites (inanimate objects such as needles, surgical instruments, door handles, and bedding). Transfusion-related protozoal infection resulting in Chagas disease has been of increasing concern to the US blood banks that have instituted screening measures ( CDC, 2007 ).

The ‘F-diagram’ illustrates major direct and indirect pathways of fecal–oral pathogen transmission and depicts the roles of water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions in providing barriers to transmission. Primary barriers prevent contact with feces, and secondary barriers prevent ingestion of feces.

Airborne transmission involves aerosolized suspensions of residue (less than five microns in size, from evaporated aerosol droplets) or particles containing agents that can be transported over time and long distance and still remain infective. TB is a classic example of an infectious disease often spread by airborne transmission.

Targeting Indirectly Transmitted Infectious Diseases

VBDs comprise approximately 17% of the global burden of infectious diseases ( Townson et al., 2005 ). For some diseases (e.g., dengue, Zika, Chagas), chemoprophylaxis and immunoprophylaxis are not prevention and control options, leaving vector control as the primary means of preventing disease transmission. Integrated vector management is defined by the WHO as, “a rational decision-making process to optimize the use of resources for vector control” ( WHO, 2012 ). There are four major categories of IVM vector control strategies: biological, chemical, environmental, and mechanical. IVM interventions are chosen from these categories based upon available resources, local patterns of disease transmission, and ecology of local disease vectors. Two key elements of IVM are collaboration within the health sector and with other sectors (e.g., agriculture, engineering) to plan and carry out vector control activities, and community engagement to promote program sustainability. Another core element is the integrated approach which often permits concurrent targeting of multiple VBDs, as some diseases are transmitted by a single, common vector, and some vector control interventions can target several different vectors. In addition, combining interventions serves not only to reduce reliance on any single intervention, but also to reduce the selection pressure for insecticide and drug resistance. Table 4 , adapted from the 2012 WHO Handbook for IVM, illustrates some of the many types of IVM activities and provides examples of VBDs that might be controlled by such interventions ( WHO, 2012 ).

Table 4

Methods used to control vectorborne diseases examples of various types of IVM activities and some of the VBDs they might control and prevent

| Category | Method | Chagas disease | Dengue | Trypanosomiasis | Japanese encephalitis | Leishmaniasis | Lymphatic filariasis | Malaria | Onchocerciasis | Schistosomiasis | Trachoma |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | Source reduction | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| Habitat manipulation | + | + | + | ||||||||

| Irrigation management and design | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| Proximity of livestock | + | + | + | ||||||||

| Waste management | + | + | |||||||||

| Mechanical | House improvement | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| Removal trapping | + | + | + | ||||||||

| Polystyrene beads | + | ||||||||||

| Biological | Natural enemy conservation | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| Biological larvicides | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| Fungi | |||||||||||

| Botanicals | + | + | |||||||||

| Chemical | Insecticide-treated bednets | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| Indoor residual spraying | + | + | + | ||||||||

| Insecticidal treatment of habitat | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| Insecticide-treated targets | + | ||||||||||

| Biorational methods | + | + | |||||||||

| Chemical repellants | + | + | + |

Diarrheal diseases primarily result from oral contact with water, food, or other vehicles contaminated with pathogenic agents originating from human or animal feces. Most (∼88%) of diarrhea-associated deaths are attributable to unsafe drinking water, inadequate sanitation, and insufficient hygiene ( Black et al., 2003 ; Prüss-Üstün et al., 2008 ). Interruption of fecal–oral transmission through provision of safe water and adequate sanitation, and promotion of personal and domestic hygiene are fundamental to diarrhea prevention and control. Fecal–oral transmission of a diarrheal agent can occur via one of several routes. In 1958, Wagner and Lanoix developed a model of major transmission depicted in what has become known as the ‘F-diagram,’ based on steps within the fecal–oral flow of transmission starting with the letter ‘F’: fluids (drinking water), fingers , flies , fields (crops and soil), floods (representative of surface water in general), and food ( Wagner and Lanoix, 1958 ; Figure 7 ). Other F's that can be considered include facilities (e.g., settings where transmission is likely to occur such as daycare centers) and fornication. The F-diagram is useful for depicting where water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) interventions act as barriers in the fecal–oral flow of diarrheal pathogens. Safe excreta disposal and handling act as primary barriers to transmission by preventing fecal pathogens from entering the environment. Once the environment has become contaminated with pathogen-containing feces, secondary and tertiary barriers to transmission include water treatment, safe transport and storage of water, provision of sewage systems to control flooding, fly control, and good personal and domestic hygiene (e.g., food hygiene) practices (requiring adequate water quantity) ( Figure 7 ). As with IVM, the control of diarrheal diseases increases with integration of control measures to achieve multiple barriers to fecal–oral transmission.

The basic approach to preventing transmission of an infectious agent from a contaminated vehicle is to prevent contamination of, decontaminate, or eliminate the vehicle. Food is a common vehicle for infectious agents, and it can potentially become contaminated at any step along the food production chain of production, processing, distribution, and preparation. Production refers to the growing of plants for harvest and raising animals for food. An example of contamination at this step includes the use of fecally contaminated water for crop irrigation. Processing refers to steps such as the chopping, grinding, or pasteurizing of food to convert it into a consumer product; if the external surface of a melon is contaminated, chopping it into pieces for sale can result in contamination of the fruit. Distribution, in which food is transferred from the place where it was produced and/or processed to the consumer, can result in contamination if, for example, the transportation vehicle is not clean. Finally, preparation is the step in which food is made ready to eat; not cleaning a cutting board after cutting raw chicken can result in microbial pathogen cross-contamination of other food items. Food hygiene is the term used to describe the conditions and activities employed to prevent or limit microbial contamination of food in order to ensure food safety. Decontamination includes sterilization , the destruction of all microbial agents, and disinfection , the destruction of specific agents.

Control of airborne diseases focuses on regulating environmental airflow and air quality to minimize contact with infectious droplet nuclei. In health-care settings, negative pressure isolation rooms and exhaust vents can be used to manipulate airflow. Recirculating, potentially infectious air can undergo high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filtration and/or be mixed with ‘clean’ (noncontaminated) air to remove or dilute the concentration of infectious particle to below the infectious dose. Health-care workers should use N95 masks. On commercial aircraft, airborne pathogen transmission is minimized by methods including regulating airflow to prevent widespread dispersal of airborne microbes throughout the cabin, HEPA filtering recirculating air, and mixing recirculating air with fresh air (considered sterile) ( Dowdall et al., 2010 ).

Portal of Entry

The portal of entry refers to the site at which the infectious agent enters a susceptible host and gains access to host tissues. Many portals of entry are the same as portals of exit and include the gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and respiratory tracts, as well as compromised skin and mucous membrane surfaces. Some infectious agents can naturally enter a susceptible host by more than one portal. For example, the three forms of human anthrax can be distinguished according to the route of agent entry: cutaneous anthrax due to entry through the skin, gastrointestinal anthrax resulting from ingestion of spores, and pulmonary anthrax following inhalation of spores.

Targeting Portals of Exit and Entry

Standard infection control practices target portals of exit (and entry) of infectious agents from human reservoirs and sources. CDC guidelines suggest two levels of precautions to stop transmission of infectious agents: Standard Precautions and transmission-based precautions ( Siegel et al., 2007 ). Standard Precautions prevent transmission of infectious agents that can be acquired by contact with blood, body fluids, nonintact skin, and mucous membranes. They can be used to prevent transmission in both health-care and non-health-care settings, regardless of whether infection is suspected or confirmed. Hand hygiene is a major component of these precautions, along with use of personal protective equipment (PPE). Common PPE include gloves, gowns, face protection (e.g., eye-protecting face shields), and respiratory protection using N95 masks to prevent inhalation of airborne infectious particles (e.g., from Mycobacterium tuberculosis ). Of note, depending on the circumstance, PPE can be used to prevent dispersal of infectious agents from their source by providing a barrier to the portal of exit, or to protect a susceptible individual by placing a barrier to a portal of entry. Respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette is used to prevent spread of infection by respiratory droplets. Main elements of respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette include covering the nose and mouth area with one's elbow during coughing or sneezing or using a surgical mask to limit dissemination of infectious respiratory secretions, and hand hygiene after contact with respiratory secretions. Other components of standard precautions include needle stick and sharp injury prevention, safe injection practices, cleaning and disinfection of potentially contaminated equipment and other objects, and safe waste management.

The Susceptible Host

A susceptible host is an individual who is at risk of infection and disease following exposure to an infectious agent. As discussed previously, there are many determinants of host susceptibility, including both innate factors determined by the genetic makeup of the host and, acquired factors such as agent-specific immunity and malnutrition.

Targeting the Susceptible Host

Important prevention and control interventions that target the susceptible host include both those that address determinants of susceptibility in the host (e.g., immunoprophylaxis, provision of adequate nutrition, treatment of underlying diseases) and those that target an infecting agent (e.g., chemoprophylaxis). Immunoprophylaxis encompasses both active immunization by vaccination and passive immunization through provision of pathogen-specific immunoglobulin.

Malnutrition is a strong risk factor for morbidity and mortality due to diarrheal disease, and a vicious cycle exists between infectious diarrheal disease leading to malnutrition and impaired immune function which, in turn, promotes increased susceptibility to infection ( Keusch et al., 2006 ). Consequently, breastfeeding and safe complementary feeding play crucial roles in protecting infants and young children from infectious diseases, particularly in resource-poor settings. Micronutrients are required for normal immune function, and vitamin A and zinc supplementations have been shown to decrease some types of infections in children deficient in these micronutrients ( Mayo-Wilson et al., 2014 ; Imdad et al., 2010 ).