5 Current Issues in the Field of Early Childhood Education

Learning Objectives

Objective 1: Identify current issues that impact stakeholders in early childhood care and education.

Objective 2: Describe strategies for understanding current issues as a professional in early childhood care and education.

Objective 3: Create an informed response to a current issue as a professional in early childhood care and education.

Current Issues in the Field—Part 1

There’s one thing you can be sure of in the field of early childhood: the fact that the field is always changing. We make plans for our classrooms based on the reality we and the children in our care are living in, and then, something happens in that external world, the place where “life happens,” and our reality changes. Or sometimes it’s a slow shift: you go to a training and hear about new research, you think it over, read a few articles, and over time you realize the activities you carefully planned are no longer truly relevant to the lives children are living today, or that you know new things that make you rethink whether your practice is really meeting the needs of every child.

This is guaranteed to happen at some point. Natural events might occur that affect your community, like forest fires or tornadoes, or like COVID-19, which closed far too many child care programs and left many other early educators struggling to figure out how to work with children online. Cultural and political changes happen, which affect your children’s lives, or perhaps your understanding of their lives, like the Black Lives Matter demonstrations that brought to light how much disparity and tension exist and persist in the United States. New information may come to light through research that allows us to understand human development very differently, like the advancements in neuroscience that help us understand how trauma affects children’s brains, and how we as early educators can counteract those affects and build resilience.

And guess what—all this change is a good thing! Read this paragraph slowly—it’s important! Change is good because we as providers of early childhood care and education are working with much more than a set of academic skills that need to be imparted to children; we are working with the whole child, and preparing the child to live successfully in the world. So when history sticks its foot into our nice calm stream of practice, the waters get muddied. But the good news is that mud acts as a fertilizer so that we as educators and leaders in the field have the chance to learn and grow, to bloom into better educators for every child, and, let’s face it, to become better human beings!

The work of early childhood care and education is so full, so complex, so packed with details to track and respond to, from where Caiden left his socks, to whether Amelia’s parents are going to be receptive to considering evaluation for speech supports, and how to adapt the curriculum for the child who has never yet come to circle time. It might make you feel a little uneasy—or, let’s face it, even overwhelmed—to also consider how the course of history may cause you to deeply rethink what you do over time.

That’s normal. Thinking about the complexity of human history while pushing Keisha on the swings makes you completely normal! As leaders in the field, we must learn to expect that we will be called upon to change, maybe even dramatically, over time.

Let me share a personal story with you: I had just become director of an established small center, and was working to sort out all the details that directing encompassed: scheduling, billing policies, and most of all, staffing frustrations about who got planning time, etc. But I was also called upon to substitute teach on an almost daily basis, so there was a lot of disruption to my carefully made daily plans to address the business end, or to work with teachers to seek collaborative solutions to long-standing conflict. I was frustrated by not having time to do the work I felt I needed to do, and felt there were new small crises each day. I couldn’t get comfortable with my new position, nor with the way my days were constantly shifting away from my plans. It was then that a co-worker shared a quote with me from Thomas F. Crum, who writes about how to thrive in difficult working conditions: “Instead of seeing the rug being pulled from under us, we can learn to dance on a shifting carpet”.

Wow! That gave me a new vision, one where I wasn’t failing and flailing, but could become graceful in learning to be responsive to change big and small. I felt relieved to have a different way of looking at my progress through my days: I wasn’t flailing at all—I was dancing! Okay, it might be a clumsy dance, and I might bruise my knees, but that idea helped me respond to each day’s needs with courage and hope.

I especially like this image for those of us who work with young children. I imagine a child hopping around in the middle of a parachute, while the other children joyfully whip their corners up and down. The child in the center feels disoriented, exhilarated, surrounded by shifting color, sensation, and laughter. When I feel like there’s too much change happening, I try to see the world through that child’s eyes. It’s possible to find joy and possibility in the disorientation, and the swirl of thoughts and feelings, and new ways of seeing and being that come from change.

Key Takeaways

Our practices in the classroom and as leaders must constantly adapt to changes in our communities and our understanding of the world around us, which gives us the opportunity to continue to grow and develop.

You are a leader, and change is happening, and you are making decisions about how to move forward, and how to adapt thoughtfully. The good news is that when this change happens, our field has really amazing tools for adapting. We can develop a toolkit of trusted sources that we can turn to to provide us with information and strategies for ethical decision making.

If You’re Afraid of Falling…

One of the most important of these is the NAEYC Code of Ethical Conduct, which expresses a commitment to core values for the field, and a set of principles for determining ethical behavior and decision-making. As we commit to the code, we commit to:

- Appreciate childhood as a unique and valuable stage of the human life cycle

- Base our work on knowledge of how children develop and learn

- Appreciate and support the bond between the child and family

- Recognize that children are best understood and supported in the context of family, culture,* community, and society

- Respect the dignity, worth, and uniqueness of each individual (child, family member, and colleague)

- Respect diversity in children, families, and colleagues

- Recognize that children and adults achieve their full potential in the context of relationships that are based on trust and respect.

If someone asked us to make a list of beliefs we have about children and families, we might not have been able to come up with a list that looked just like this, but, most of us in the field are here because we share these values and show up every day with them in our hearts.

The Code of Ethical Conduct can help bring what’s in your heart into your head. It’s a complete tool to help you think carefully about a dilemma, a decision, or a plan, based on these values. Sometimes we don’t make the “right” decision and need to change our minds, but as long as we make a decision based on values about the importance of the well-being of all children and families, we won’t be making a decision that we will regret.

An Awfully Big Current Issue—Let’s Not Dance Around It

In the field of early childhood, issues of prejudice have long been important to research, and in this country, Head Start was developed more than 50 years ago with an eye toward dismantling disparity based on ethnicity or skin color (among other things). However, research shows that this gap has not closed. Particularly striking, in recent years, is research addressing perceptions of the behavior of children of color and the numbers of children who are asked to leave programs.

In fact, studies of expulsion from preschool showed that black children were twice as likely to be expelled as white preschoolers, and 3.6 times as likely to receive one or more suspensions. This is deeply concerning in and of itself, but the fact that preschool expulsion is predictive of later difficulties is even more so:

Starting as young as infancy and toddlerhood, children of color are at highest risk for being expelled from early childhood care and education programs. Early expulsions and suspensions lead to greater gaps in access to resources for young children and thus create increasing gaps in later achievement and well-being… Research indicates that early expulsions and suspensions predict later expulsions and suspensions, academic failure, school dropout, and an increased likelihood of later incarceration.

Why does this happen? It’s complicated. Studies on the K-12 system show that some of the reasons include:

- uneven or biased implementation of disciplinary policies

- discriminatory discipline practices

- school racial climate

- under resourced programs

- inadequate education and training for teachers on bias

In other words, educators need more support and help in reflecting on their own practices, but there are also policies and systems in place that contribute to unfair treatment of some groups of children.

Key Takeaway

So…we have a lot of research that continues to be eye opening and cause us to rethink our practices over time, plus a cultural event—in the form of the Black Lives Matter movement—that push the issue of disparity based on skin color directly in front of us. We are called to respond. You are called to respond.

How Will I Ever Learn the Steps?

Woah—how do I respond to something so big and so complex and so sensitive to so many different groups of people?

As someone drawn to early childhood care and education, you probably bring certain gifts and abilities to this work.

- You probably already feel compassion for every child and want every child to have opportunities to grow into happy, responsible adults who achieve their goals. Remember the statement above about respecting the dignity and worth of every individual? That in itself is a huge start to becoming a leader working as an advocate for social justice.

- You may have been to trainings that focus on anti-bias and being culturally responsive.

- You may have some great activities to promote respect for diversity, and be actively looking for more.

- You may be very intentional about including materials that reflect people with different racial identities, genders, family structures.

- You may make sure that each family is supported in their home language and that multilingualism is valued in your program.

- You may even have spent some time diving into your own internalized biases.

This list could become very long! These are extremely important aspects of addressing injustice in early education which you can do to alter your individual practice with children.

As a leader in the field, you are called to think beyond your own practice. As a leader you have the opportunity—the responsibility!—to look beyond your own practices and become an advocate for change. Two important recommendations (of many) from the NAEYC Advancing Equity in Early Childhood Education Position Statement, another important tool:

Speak out against unfair policies or practices and challenge biased perspectives. Work to embed fair and equitable approaches in all aspects of early childhood program delivery, including standards, assessments, curriculum, and personnel practices.

Look for ways to work collectively with others who are committed to equity. Consider it a professional responsibility to help challenge and change policies, laws, systems, and institutional practices that keep social inequities in place.

One take away I want you to grab from those last sentences: You are not alone. This work can be, and must be, collective.

As a leader, your sphere of influence is bigger than just you. You can influence the practices of others in your program and outside of it. You can influence policies, rules, choices about the tools you use, and ultimately, you can even challenge laws that are not fair to every child.

Who’s on your team? I want you to think for a moment about the people who help you in times where you are facing change. These are the people you can turn to for an honest conversation, where you can show your confusion and fear, and they will be supportive and think alongside you. This might include your friends, your partner, some or all of your coworkers, a former teacher of your own, a counselor, a pastor. Make a quick list of people you can turn to when you need to do some deep digging and ground yourself in your values.

And now, your workplace team: who are your fellow advocates in your workplace? Who can you reach out to when you realize something might need to change within your program?

Wonderful. You’ve got other people to lean on in times of change. More can be accomplished together than alone. Let’s consider what you can do:

What is your sphere of influence? What are some small ways you can create room for growth within your sphere of influence? What about that workplace team? Do their spheres of influence add to your own?

Try drawing your sphere of influence: Draw yourself in the middle of the page, and put another circle around yourself, another circle around that, and another around that. Fill your circles in:

- Consider the first circle your personal sphere. Brainstorm family and friends who you can talk to about issues that are part of your professional life. You can put down their names, draw them, or otherwise indicate who they might be!

- Next, those you influence in your daily work, such as the children in your care, their families, maybe your co-workers land here.

- Next, those who make decisions about the system you are in—maybe this is your director or board, or even a PTA.

- Next, think about the early childhood care and education community you work within. What kind of influence could you have on this community? Do you have friends who work at other programs you can have important conversations with to spread ideas? Are you part of a local Association for the Education of Young Children (AEYC)? Could you speak to the organizers of a local conference about including certain topics for sessions?

- And finally, how about state (and even national) policies? Check out The Children’s Institute to learn about state bills that impact childcare. Do you know your local representatives? Could you write a letter to your senator? Maybe you have been frustrated with the slow reimbursement and low rates for Employment Related Day Care subsidies and can find a place to share your story. You can call your local Child Care Resource and Referral, your local or state AEYC chapter, or visit childinst.org to find out how you can increase your reach! It’s probably a lot farther than you think!

Break It Down: Systemic Racism

When you think about injustice and the kind of change you want to make, there’s an important distinction to understand in the ways injustice happens in education (or anywhere else). First, there’s personal bias and racism, and of course it’s crucial as an educator to examine ourselves and our practices and responses. We all have bias and addressing it is an act of courage that you can model for your colleagues.

In addition, there’s another kind of bias and racism, and it doesn’t live inside of individual people, but inside of the systems we have built. Systemic racism exists in the structures and processes that have come into place over time, which allow one group of people a greater chance of succeeding than other specific groups of people.

Key Takeaways (Sidebar)

Systemic racism is also called institutional racism, because it exists – sometimes unquestioned – within institutions themselves.

In early childhood care and education, there are many elements that were built with middle class white children in mind. Many of our standardized tests were made with middle class white children in mind. The curriculum we use, the assessments we use, the standards of behavior we have been taught; they may have all been developed with middle class white children in mind.

Therefore it is important to consider whether they adequately and fairly work for all of the children in your program community. Do they have relevance to all children’s lived experience, development, and abilities? Who is being left out?

Imagine a vocabulary assessment in which children are shown common household items including a lawn mower…common if you live in a house; they might well be unfamiliar to a three-year-old who lives in an apartment building, however. The child may end up receiving a lower score, though their vocabulary could be rich, full of words that do reflect the objects in their lived experience.

The test is at fault, not the child’s experience. Yet the results of that test can impact the way educators, parents, and the child see their ability and likelihood to succeed.

You Don’t Have to Invent the Steps: Using an Equity Lens

In addition to the NAEYC Code of Ethical Conduct and Equity Statement, another tool for addressing decision-making is an equity lens. To explain what an equity lens is, we first need to talk about equity. It’s a term you may have heard before, but sometimes people confuse it with equality. It’s a little different – equity is having the resources needed to be successful.

There’s a wonderful graphic of children looking over a fence at a baseball game. In one frame, each child stands at the fence; one is tall enough to see over the top; another stands tip-toe, straining to see; and another is simply too short. This is equality—everyone has the same chance, but not everyone is equally prepared. In the frame titled equity, each child stands on a stool just high enough so that they may all see over the fence. The stools are the supports they need to have an equitable outcome—being able to experience the same thing as their friend.

Seeking equity means considering who might not be able to see over the fence and figuring out how to build them a stool so that they have the same opportunity.

An equity lens, then, is a tool to help you look at decisions through a framework of equity. It’s a series of questions to ask yourself when making decisions. An equity lens is a process of asking a series of questions to better help you understand if something (a project, a curriculum, a parent meeting, a set of behavioral guidelines) is unfair to specific individuals or groups whose needs have been overlooked in the past. This lens might help you to identify the impact of your decisions on students of color, and you can also use the lens to consider the impact on students experiencing poverty, students in nontraditional families, students with differing abilities, students who are geographically isolated, students whose home language is other than English, etc.) The lens then helps you determine how to move past this unfairness by overcoming barriers and providing equitable opportunities to all children.

Some states have adopted a version of the equity lens for use in their early learning systems. Questions that are part of an equity lens might include:

- What decision is being made, and what kind of values or assumptions are affecting how we make the decision?

- Who is helping make the decision? Are there representatives of the affected group who get to have a voice in the process?

- Does the new activity, rule, etc. have the potential to make disparities worse? For instance, could it mean that families who don’t have a car miss out on a family night? Or will it make those disparities better?

- Who might be left out? How can we make sure they are included?

- Are there any potential unforeseen consequences of the decision that will impact specific groups? How can we try to make sure the impact will be positive?

You can use this lens for all kinds of decisions, in formal settings, like staff meetings, and you can also work to make them part of your everyday thinking. I have a sticky note on my desk that asks “Who am I leaving out”? This is an especially important question if the answer points to children who are people of color, or another group that is historically disadvantaged. If that’s the answer, you don’t have to scrap your idea entirely. Celebrate your awareness, and brainstorm about how you can do better for everyone—and then do it!

Embracing our Bruised Knees: Accepting Discomfort as We Grow

Inspirational author Brene Brown, who writes books, among other things, about being an ethical leader, said something that really walloped me: if we avoid the hard work of addressing unfairness (like talking about skin color at a time when our country is divided over it) we are prioritizing our discomfort over the pain of others.

Imagine a parent who doesn’t think it’s appropriate to talk about skin color with young children, who tells you so with some anger in their voice. That’s uncomfortable, maybe even a little scary. But as you prioritize upholding the dignity, worth, and uniqueness of every individual, you can see that this is more important than trying to avoid discomfort. Changing your practice to avoid conflict with this parent means prioritizing your own momentary discomfort over the pain children of color in your program may experience over time.

We might feel vulnerable when we think about skin color, and we don’t want to have to have the difficult conversation. But if keeping ourselves safe from discomfort means that we might not be keeping children safe from very real and life-impacting racial disparity, we’re not making a choice that is based in our values.

Change is uncomfortable. It leaves us feeling vulnerable as we reexamine the ideas, strategies, even the deeply held beliefs that have served us so far. But as a leader, and with the call to support every child as they deserve, we can develop a sort of super power vision, where we can look unflinchingly around us and understand the hidden impacts of the structures we work within.

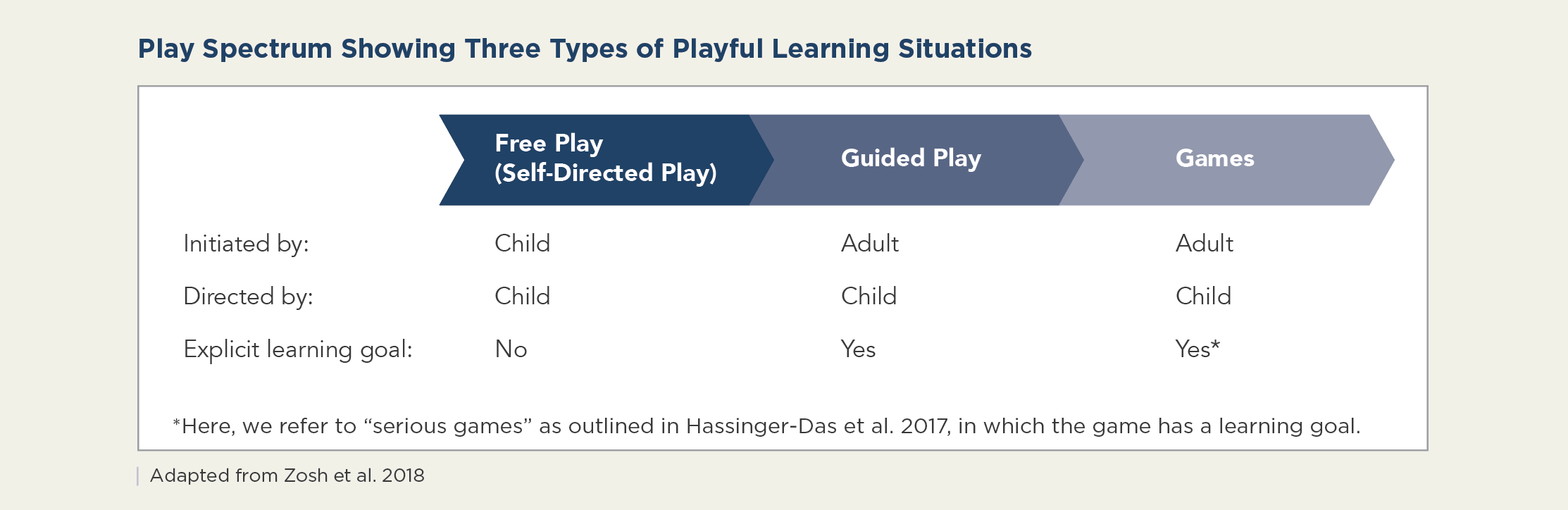

A Few Recent Dance Steps of My Own

You’re definitely not alone—researchers and thinkers in the field are doing this work alongside you, examining even our most cherished and important ideas about childhood and early education. For instance, a key phrase that we often use to underpin our decisions is developmentally appropriate practice, which NAEYC defines as “methods that promote each child’s optimal development and learning through a strengths-based, play-based approach to joyful, engaged learning.” The phrase is sometimes used to contrast against practices that might not be developmentally appropriate, like expecting three-year-olds to write their names or sit quietly in a 30 minute story time.

Let me tell you a story about how professional development is still causing me to stare change in the face! At the NAEYC conference in 2020, during a session in which Dr. Jie-Qi Chen presented on different perspectives on developmentally appropriate practice among early educators in China and the United States. She showed a video from a classroom in China to educators in both the US and in China. The video was of a circle time in which a child was retelling a story that the class knew well, and then the children were encouraged to offer feedback and rate how well the child had done. The children listened attentively, and then told the storytelling child how they had felt about his retelling, including identifying parts that had been left out, inaccuracies in the telling, and advice for speaking more clearly and loudly.

The educators were asked what the impact of the activity would be on the children and whether it was developmentally appropriate. The educators in the United States had deep concerns that the activity would be damaging to a child’s self esteem, and was therefore not developmentally appropriate. They also expressed concerns about the children being asked to sit for this amount of time. The educators in the classroom in China felt that it was developmentally appropriate and the children were learning not only storytelling skills but how to give and receive constructive criticism.

As I watched the video, I had the same thoughts as the educators from the US—I’m not used to children being encouraged to offer criticism rather than praise. But I also saw that the child in question had self-confidence and received the feedback positively. The children were very engaged and seemed to feel their feedback mattered.

What was most interesting to me here was the idea of self-esteem, and how important it is to us here in the United States, or rather, how much protecting we feel it needs. I realized that what educators were responding to weren’t questions of whether retelling a story was developmentally appropriate, or whether the critical thinking skills the children were being asked to display were developmentally appropriate, but rather whether the social scenario in which one child receives potentially negative feedback in front of their peers was developmentally appropriate, and that the responses were based in the different cultural ideas of self-esteem and individual vision versus collective success.

My point here is that even our big ideas, like developmentally appropriate practice, have an element of vulnerability to them. As courageous leaders, we need to turn our eyes even there to make sure that our cultural assumptions and biases aren’t affecting our ability to see clearly, that the reality of every child is honored within them, and that no one is being left out. And that’s okay. It doesn’t mean we should scrap them. It’s not wrong to advocate for and use developmentally appropriate practice as a framework for our work—not at all! It just means we need to remember that it’s built from values that may be specific to our culture—and not everyone may have equal access to that culture. It means we should return to our big ideas with respect and bravery and sit with them and make sure they are still the ones that serve us best in the world we are living in right now, with the best knowledge we have right now.

You, Dancing With Courage

So…As a leader is early childhood, you will be called upon to be nimble, to make new decisions and reframe your practice when current events or new understanding disrupt your plans. When this happens, professional tools are available to you to help you make choices based on your ethical commitment to children.

Change makes us feel uncomfortable but we can embrace it to do the best by the children and families we work with. We can learn to develop our critical thinking skills so that we can examine our own beliefs and assumptions, both as individuals and as a leader.

Remember that person dancing on the shifting carpet? That child in the middle of the parachute? They might be a little dizzy, but with possibility. They might lose their footing, but in that uncertainty, in the middle of the billowing parachute, there is the sensation that the very instability provides the possibility of rising up like the fabric. And besides—there are hands to hold if they lose their balance—or if you do! And so can you rise when you allow yourself to accept change and adapt to all the new possibility of growth that it opens up!

Current Issues in the Field Part 2—Dance Lessons

Okay, sure—things are gonna change, and this change is going to affect the lives of the children and families you work with, and affect you, professionally and personally. So—you’re sold, in theory, that to do the best by each one of those children, you’re just going to have to do some fancy footwork, embrace the change, and think through how to best adapt to it.

But…how? Before we talk about the kind of change that’s about rethinking your program on a broad level, let’s talk about those times we face when change happens in the spur of the moment, and impacts the lives of the children in your program—those times when your job becomes helping children process their feelings and adapt to change. Sometimes this is a really big deal, like a natural disaster. Sometimes it’s something smaller like the personal story I share below…something small, cuddly, and very important to the children.

Learning the Steps: How do I help children respond to change?

I have a sad story to share. For many years, I was the lead teacher in a classroom in which we had a pet rabbit named Flopsy. Flopsy was litter-trained and so our licensing specialist allowed us to let him hop freely around the classroom. Flopsy was very social, and liked to interact with children. He liked to be held and petted and was also playful, suddenly zooming around the classroom, hopping over toys and nudging children. Flopsy was a big part of our community and of children’s experience in our classroom.

One day, I arrived at school to be told by my distraught director that Flopsy had died in the night and she had removed his body. I had about 15 minutes before children would be arriving, and I had to figure out how to address Flopsy’s loss.

I took a few minutes to collect myself, and considered the following questions:

Yes, absolutely. The children would notice immediately that Flopsy was missing and would comment on it. It was important that I not evade their questions.

Flopsy had died. His body had stopped working. His brain had stopped working. He would not ever come back to life. We would never see Flopsy again. I wrote these sentences on a sticky note. They were short but utterly important.

I would give children the opportunity to share their feelings, and talk about my own feelings. I would read children’s books that would express feelings they might not have words for yet. I would pay extra attention to children reaching out to me and offer opportunities to affirm children’s responses by writing them down.

Human beings encounter death. Children lose pets, grandparents, and sometimes parents or siblings. I wanted these children to experience death in a way that would give them a template when they experienced more intense loss. I wanted them to know it’s okay to be sad, and that the sadness grows less acute over time. That it’s okay to feel angry or scared, and that these feelings, too, though they might be really big, will become less immediate. And that it’s okay to feel happy as you remember the one you lost.

I knew it was important not to give children mistaken impressions about death. I was careful not to compare it to sleep, because I didn’t want them to think that maybe Flopsy would wake up again. I also didn’t want them to fear that when mama fell asleep it was the same thing as death. I also wanted to be factual but leave room for families to share their religious beliefs with their children.

I didn’t have time to do research. But I mentally gathered up some wisdom from a training I’d been to, where the trainer talked about how important it is that we don’t shy away from addressing death with children. Her words gave me courage. I also gathered up some children’s books about pet death from our library.

The first thing I did was text my husband. I was really sad. I had cared for this bunny for years and I loved him too. I didn’t have time for a phone call, but that text was an important way for me to acknowledge my own feelings of grief.

Then I talked to the other teachers. I asked for their quick advice, and shared my plan, since the news would travel to other classrooms as well.

During my prep time that day, I wrote a letter to families, letting them know Flopsy had died and some basic information about how we had spoken to children about it, some resources about talking to children about death, and some titles of books about the death of pets. I knew that news of Flopsy’s death would be carried home to many families, and that parents might want to share their own belief systems about death. I also knew many parents were uncomfortable discussing death with young children and that it might be helpful to see the way we had done so.

I had curriculum planned for that day which I partially scrapped. At our first gathering time I shared the news with the whole group: I shared my sticky note of information about death. I told the children I was sad. I asked if they had questions and I answered them honestly. I listened when they shared their own feelings. I also told them I had happy memories of FLopsy and we talked about our memories.

During the course of the day, and the next few days, I gave the children invitations (but not assignments) to reflect on Flopsy and their feelings. I sat on the floor with a notebook and the invitation for children to write a “story” about Flopsy. Almost every child wanted their words recorded. Responses ranged from “Goodbye bunny” to imagined stories about Flopsy’s adventures, to a description of feelings of sadness and loss. Writing down these words helped acknowledge the children’s feelings. Some of them hung their stories on the wall, and some asked them to be read aloud, or shared them themselves, at circle time.

I also made sure there were plenty of other opportunities in the classroom for children who didn’t want to engage in these ways, or who didn’t need to.

We read “Saying Goodbye to Lulu” and “The Tenth Good Thing About Barney” in small groups; and while these books were a little bit above the developmental level of some children in the class, many children wanted to hear and discuss the books. When I became teary reading them, I didn’t try to hide it, but just said “I’m feeling sad, and it makes me cry a little bit. Everyone cries sometimes.”

This would be a good set of steps to address an event like a hurricane, wildfires, or an earthquake as well. First and foremost of course, make sure your children are safe and have their physical needs met! Remember your role as educator and caretaker; address their emotional needs, consider what you hope they will learn, gather the resources and your team, and make decisions that affirm the dignity of each child in your care.

- Does the issue affect children’s lived experiences?

- How much and what kind of information is appropriate for their age?

- How can I best affirm their emotions?

- What do I hope they will learn?

- Could I accidentally be doing harm through my response?

- Which resources do I need and can I gather in a timely manner?

- How do I gather my team?

- How can I involve families?

- Now, I create and enact my plan…

Did your plan look any different for having used these questions? And did the process of making decisions as a leader look or feel different? How so?

You might not always walk yourself through a set of questions–but using an intentional tool is like counting out dance steps—there’s a lot of thinking it through at first, and maybe forgetting a step, and stumbling, and so forth. And then…somehow, you just know how to dance. And then you can learn to improvise. In other words, it is through practice that you will become adept at and confident in responding to change, and learn to move with grace on the shifting carpet of life.

Feeling the Rhythm: How do I help myself respond to change

—and grow through it.

Now, let’s address what it might look like to respond to a different kind of change, the kind in which you learn something new and realize you need to make some changes in who you are as an educator. This is hard, but there are steps you can take to make sure you keep moving forward:

- Work to understand your own feelings. Write about them. Talk them through with your teams—personal and/or professional.

- Take a look in the mirror, strive to see where you are at, and then be kind to yourself!

- Gather your tools! Get out that dog eared copy of the NAEYC Code of Ethical Conduct, and look for other tools that are relevant to your situation. Root yourself in the values of early childhood care and education.

- Examine your own practices in light of this change.

- Examine the policies, structures, or systems that affect your program in light of this change.

- Ask yourself, where could change happen? Remember your spheres of influence.

- Who can you collaborate with? Who is on your team?

- How can you make sure the people being affected by this change help inform your response? Sometimes people use the phrase “Nothing for us without us” to help remember that we don’t want to make decisions that affect a group of people (even if we think we’re helping) without learning more from individuals in that group about what real support looks like).

- Make a plan, including a big vision and small steps, and start taking those small steps. Remember that when you are ready to bring others in, they will need to go through some of this process too, and you may need to be on their team as they look for a safe sounding board to explore their discomfort or fear.

- Realize that you are a courageous advocate for children. Give yourself a hug!

- Work to understand your own feelings. Write about them. Talk them through with your teams—personal and/or professional.

This might be a good time to freewrite about your feelings—just put your pencil to paper and start writing. Maybe you feel guilty because you’re afraid that too many children of color have been asked to leave your program. Maybe you feel angry about the injustice. Maybe you feel scared that this topic is politicized and people aren’t going to want to hear about it. Maybe you feel scared to even face the idea that bias could have affected children while in your care. All these feelings are okay! Maybe you talk to your partner or your friends about your fears before you’re ready to get started even thinking about taking action.

- Take a look in the mirror, strive to see where you are at, and then be kind to yourself! Tell that person looking back at you: “I did then what I knew how to do. Now that I know better, I do better.”

Yep. You love children and you did what you believed was best for the children in your program. Maybe now you can do even better by them! You are being really really brave by investigating!

- Gather your tools! Get out that dog-eared copy of the NAEYC Code of Ethical Conduct, and look for other tools that are relevant to your situation.

Okay! This would be an excellent time to bring out the equity lens and your other tools. Read them over. Use them.

Do your practices affirm the dignity of every child and family? Ask yourself these hard questions while focusing on, in this case, how you look at behavior of children of color. Do the choices you make affirm the dignity of each unique child? Use your tools—you can pull out the equity lens here! Are you acknowledging the home realities of each child when you are having conversations that are meant to build social-emotional skills? Are you considering the needs of each child during difficult transitions? Do you provide alternative ways for children to engage if they have difficulty sitting in circle times?

And…Do your policies and structures affirm the dignity of every child and family? Use those tools! Look at your behavioral guidance policies—are you expecting children to come into your program with certain skills that may not be valued by certain cultures? What about your policies on sending children home or asking a family to leave your program? Could these policies be unfair to certain groups? In fact—given that you now know how extremely impactful expulsion is for preschoolers, could you take it off the table entirely?

Let’s say you’re a teacher, and you can look back and see that over the years you’ve been at your center, a disproportionately high number of children of color have been excluded from the program. Your director makes policy decisions—can you bring this information to him or her? Could you talk to your coworkers about how to bring it up? Maybe your sphere of influence could get even wider—could you share this information with other early educators in your community? Maybe even write a letter to your local representatives!

- Who can you collaborate with? Who is on your team?

Maybe other educators? Maybe parents? Maybe your director? Maybe an old teacher of your own? Can you bring this up at a staff meeting? Or in informal conversations?

- How can you make sure the people being affected by this change help inform your response?

Let’s say your director is convinced that your policies need to change in light of this new information. You want to make sure that parent voice—and especially that of parents of color—is heard! You could suggest a parent meeting on the topic; or maybe do “listening sessions” with parents of color, where you ask them open-ended questions and listen and record their responses—without adding much of your own response; maybe you could invite parents to be part of a group who looks over and works on the policies. This can feel a little scary to people in charge (see decentered leadership?)

Maybe this plan is made along with your director and includes those parent meetings, and a timeline for having revised policies, and some training for the staff. Or—let’s back it up—maybe you’re not quite to that point yet, and your plan is how you are going to approach your director, especially since they might feel criticized. Then your plan might be sharing information, communicating enthusiasm about moving forward and making positive change, and clearly stating your thoughts on where change is needed! (Also some chocolate to reward yourself for being a courageous advocate for every child.)

And, as I may have mentioned, some chocolate. You are a leader and an advocate, and a person whose action mirrors their values. You are worth admiring!

Maybe you haven’t had your mind blown with new information lately, but I’ll bet there’s something you’ve thought about that you haven’t quite acted on yet…maybe it’s about individualizing lesson plans for children with differing abilities. Maybe it’s about addressing diversity of gender in the classroom. Maybe it’s about celebrating linguistic diversity, inviting children and parents to share their home languages in the classroom, and finding authentic ways to include print in these languages.

Whatever it is—we all have room to grow.

Make a Plan!

Dancing Your Dance: Rocking Leadership in Times of Change

There will never be a time when we as educators are not having to examine and respond to “Current Issues in the Field.” Working with children means working with children in a dynamic and ever-evolving landscape of community, knowledge, and personal experience. It’s really cool that we get to do this, walk beside small human beings as they learn to traverse the big wacky world with all its potholes…and it means we get to keep getting better and better at circling around, leaping over, and, yep, dancing around or even through those very potholes.

In conclusion, all dancers feel unsteady sometimes. All dancers bruise their knees along the way. All educators make mistakes and experience discomfort. All dancers wonder if this dance just isn’t for them. All dancers think that maybe this one is just too hard and want to quit sometimes. All educators second guess their career choices. But all dancers also discover their own innate grace and their inborn ability to both learn and to change; our very muscles are made to stretch, our cells replace themselves, and we quite simply cannot stand still. All educators have the capacity to grow into compassionate, courageous leaders!

Your heart, your brain, and your antsy feet have led you to become a professional in early childhood care and education, and they will all demand that you jump into the uncertainty of leadership in times of change, and learn to dance for the sake of the children in your care. This, truly, is your call to action, and your pressing invitation to join the dance!

Brown, B. (2018). Dare to lead . Vermilion.

Broughton, A., Castro, D. and Chen, J. (2020). Three International Perspectives on Culturally Embraced Pedagogical Approaches to Early Teaching and Learning. [Conference presentation]. NAEYC Annual Conference.

Crum, T. (1987). The Magic of Conflict: Turning a Life of Work into a Work of Art. Touchstone.

Meek, S. and Gilliam, W. (2016). Expulsion and Suspension in Early Education as Matters of Social Justice and Health Equity. Perspectives: Expert Voices in Health & Health Care.

Scott, K., Looby, A., Hipp, J. and Frost, N. (2017). “Applying an Equity Lens to the Child Care Setting.” The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 45 (S1), 77-81.

Online Resources for Current Issues in the Field

Resources for opening yourself to personal growth, change, and courageous leadership:

- Brown, Brenee. Daring Classrooms. https://brenebrown.com/daringclassrooms

- Chang, R. (March 25, 2019). What Growth Mindset Means for Kids [Video] . TED Conferences. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=66yaYmUNOx4

Resources for Thinking About Responding to Current Issues in Education

- Flanagan, N. (July 31, 2020). How School Should Respond to Covid-19 [Video] . TED Conferences. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cSkUHHH4nb8

- Harris, N.B.. (February 217, 015). How Childhood Trauma Affects Health Across a Lifetime [Video] . TED Conferences. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=95ovIJ3dsNk

- Simmons, D. (August 28, 2020). 6 Ways to be an Anti Racist Educator [Video] . Edutopia. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UM3Lfk751cg&t=3s

Leadership in Early Care and Education Copyright © 2022 by Dr. Tammy Marino; Dr. Maidie Rosengarden; Dr. Sally Gunyon; and Taya Noland is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

A top researcher says it's time to rethink our entire approach to preschool

Anya Kamenetz

Dale Farran has been studying early childhood education for half a century. Yet her most recent scientific publication has made her question everything she thought she knew.

"It really has required a lot of soul-searching, a lot of reading of the literature to try to think of what were plausible reasons that might account for this."

And by "this," she means the outcome of a study that lasted more than a decade. It included 2,990 low-income children in Tennessee who applied to free, public prekindergarten programs. Some were admitted by lottery, and the others were rejected, creating the closest thing you can get in the real world to a randomized, controlled trial — the gold standard in showing causality in science.

The Tennessee Pre-K Debate: Spinach Vs. Easter Grass

Farran and her co-authors at Vanderbilt University followed both groups of children all the way through sixth grade. At the end of their first year, the kids who went to pre-K scored higher on school readiness — as expected.

But after third grade, they were doing worse than the control group. And at the end of sixth grade, they were doing even worse. They had lower test scores, were more likely to be in special education, and were more likely to get into trouble in school, including serious trouble like suspensions.

"Whereas in third grade we saw negative effects on one of the three state achievement tests, in sixth grade we saw it on all three — math, science and reading," says Farran. "In third grade, where we had seen effects on one type of suspension, which is minor violations, by sixth grade we're seeing it on both types of suspensions, both major and minor."

That's right. A statewide public pre-K program, taught by licensed teachers, housed in public schools, had a measurable and statistically significant negative effect on the children in this study.

Farran hadn't expected it. She didn't like it. But her study design was unusually strong, so she couldn't easily explain it away.

"This is still the only randomized controlled trial of a statewide pre-K, and I know that people get upset about this and don't want it to be true."

Why it's a bad time for bad news

It's a bad time for early childhood advocates to get bad news about public pre-K. Federally funded universal prekindergarten for 3- and 4-year-olds has been a cornerstone of President Biden's social agenda, and there are talks about resurrecting it from the stalled-out "Build Back Better" plan. Preschool has been expanding in recent years and is currently publicly funded to some extent in 46 states. About 7 in 10 4-year-olds now attend some kind of academic program.

This enthusiasm has rested in part on research going back to the 1970s. Nobel Prize-winning economist James Heckman, among others, showed substantial long-term returns on investment for specially designed and carefully implemented programs.

To put it crudely, policymakers and experts have touted for decades now that if you give a 4-year-old who is growing up in poverty a good dose of story time and block play, they'll be more likely to grow up to become a high-earning, productive citizen.

What went wrong in Tennessee

No study is the last word. The research on pre-K continues to be mixed. In May 2021, a working paper (not yet peer reviewed) came out that looked at Boston's pre-K program. The study was a similar size to Farran's, used a similar quasi-experimental design based on random assignment, and also followed up with students for years. This study found that the preschool kids had better disciplinary records and were much more likely to graduate from high school, take the SATs and go to college, though their test scores didn't show a difference.

Farran believes that, with a citywide program, there's more opportunity for quality control than in her statewide study. Boston's program spent more per student, and it also was mixed-income, whereas Tennessee's program is for low-income kids only.

So what went wrong in Tennessee? Farran has some ideas — and they challenge almost everything about how we do school. How teachers are prepared, how programs are funded and where they are located. Even something as simple as where the bathrooms are.

In short, Farran is rethinking her own preconceptions, which are an entire field's preconceptions, about what constitutes quality pre-K.

Do kids in poverty deserve the same teaching as rich kids?

"One of the biases that I hadn't examined in myself is the idea that poor children need a different sort of preparation from children of higher-income families."

She's talking about drilling kids on basic skills. Worksheets for tracing letters and numbers. A teacher giving 10-minute lectures to a whole class of 25 kids who are expected to sit on their hands and listen, only five of whom may be paying any attention.

A Harsh Critique Of Federally Funded Pre-K

"Higher-income families are not choosing this kind of preparation," she explains. "And why would we assume that we need to train children of lower-income families earlier?"

Farran points out that families of means tend to choose play-based preschool programs with art, movement, music and nature. Children are asked open-ended questions, and they are listened to.

5 Proven Benefits Of Play

This is not what Farran is seeing in classrooms full of kids in poverty, where "teachers talk a lot, but they seldom listen to children." She thinks that part of the problem is that teachers in many states are certified for teaching students in prekindergarten through grade 5, or sometimes even pre-K-8. Very little of their training focuses on the youngest learners.

So another major bias that she's challenging is the idea that teacher certification equals quality. "There have been three very large studies, the latest one in 2018, which are not showing any relationship between quality and licensure."

Putting a bubble in your mouth

In 2016, Farran published a study based on her observations of publicly funded Tennessee pre-K classrooms similar to those included in this paper. She found then that the largest chunk of the day was spent in transition time. This means simply moving kids around the building.

Partly this is an architectural problem. Private preschools, even home-based day cares, tend to be laid out with little bodies in mind. There are bathrooms just off the classrooms. Children eat in, or very near, the classroom, too. And there is outdoor play space nearby with equipment suitable for short people.

Putting these same programs in public schools can make the whole day more inconvenient.

"So if you're in an older elementary school, the bathroom is going to be down the hall. You've got to take your children out, line them up and then they wait," Farran says. "And then, if you have to use the cafeteria, it's the same thing. You have to walk through the halls, you know: 'Don't touch your neighbor, don't touch the wall, put a bubble in your mouth because you have to be quiet.' "

One of Farran's most intriguing conjectures is that this need for control could explain the extra discipline problems seen later on in her most recent study.

"I think children are not learning internal control. And if anything, they're learning sort of an almost allergic reaction to the amount of external control that they're having, that they're having to experience in school."

In other words, regularly reprimanding kids for doing normal kid stuff at 4 years old, even suspending them, could backfire down the road as children experience school as a place of unreasonable expectations.

We know from other research that the control of children's bodies at school can have disparate racial impact. Other studies have suggested that Black children are disciplined more often in preschool, as they are in later grades. Farran's study, where 70% of the kids were white, found interactions between race, gender, and discipline problems, but no extra effect of attending preschool was detected.

Preschool Suspensions Really Happen And That's Not OK With Connecticut

Where to go from here.

The United States has a child care crisis that COVID-19 both intensified and highlighted. Progressive policymakers and advocates have tried for years to expand public support for child care by "pushing it down" from the existing public school system, using the teachers and the buildings.

Farran praises the direction that New York City, for one, has taken instead: a "mixed-delivery" program with slots for 3- and 4-year-olds. Some kids attend free public preschool in existing nonprofit day care centers, some in Head Start programs and some in traditional schools.

But the biggest lesson Farran has drawn from her research is that we've simply asked too much of pre-K, based on early results from what were essentially showcase pilot programs. "We tend to want a magic bullet," she says.

"Whoever thought that you could provide a 4-year-old from an impoverished family with 5 1/2 hours a day, nine months a year of preschool, and close the achievement gap, and send them to college at a higher rate?" she asks. "I mean, why? Why do we put so much pressure on our pre-K programs?"

We might actually get better results, she says, from simply letting little children play.

Early Childhood

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

The Effects of COVID-19 on Early Childhood Education and Care: Research and Resources for Children, Families, Teachers, and Teacher Educators

Mary renck jalongo.

Emerita, Indiana University of Pennsylvania, 654 College Lodge Road, Indiana, PA 15701 USA

The COVID-19 world health crisis has profound implications for the care and education of young children in homes and schools, the lives of preservice and inservice teachers, and the work of college/university faculty. This article begins by discussing the implications of a world health pandemic for education and the challenges of conducting a literature review on such a rapidly evolving topic. The next four sections categorize the COVID-19 literature into themes: (1) threats to quality of life (QoL) and wellness, (2) pressure on families and intensification of inequities, (3) changes in teaching methods and reliance on technology, and (4) restructuring of higher education and scholarship interrupted. Each of the four themes is introduced with a narrative that highlights the current context, followed by the literature review. Next is a compilation of high-quality, online resources developed by leading professional organizations to support children, families, and educators dealing with the COVID crisis. The article concludes with changes that hold the greatest potential to advance the field of early childhood education and care.

Implications of a World Health Pandemic for Education

As of April 6, 2020, officials in all 50 states of the United States issued orders for school closures through the month in response to COVID-19. As I passed by our university campus on an errand to pick up essential items, I noticed a parking lot that ordinarily would have been jammed with faculty, staff, and students frantically searching for an empty space. With the exodus of the college students and the governor’s stay-at-home order in effect, our college town’s population had dropped by almost half. The situation was very different from what we were seeing in the media coverage of China, Italy, or New York City. Here in our small town, a group of volunteers with masks and gloves unloaded bag after bag of nonperishable groceries and other essential items from the back of three large trucks. The bags would be distributed to people in need, no questions asked. The town was quiet, yet underneath that illusion of calm, educational programs were in turmoil. All in-person class gatherings at all levels of education had ceased. Early childhood programs were in suspended animation and the Head Start building stood dark and empty. Parents with children in public schools were suddenly expected to home school. University faculty quickly converted courses to online formats, puzzled over how to provide practicum experiences, and worried about how future caregivers and teachers would meet professional standards and licensure criteria.

Education plays a particularly significant role in children and adolescents’ health and well-being and has a lasting impact on their lives as adults (Hamad et al., 2018 ). There is little question that the global health pandemic has caused unprecedented disruption to all spheres of human life and to education worldwide (d’ Orville, 2020 ; Zhu & Liu, 2020 ). UNESCO, ( 2020a ) estimates that 1.2 billion school children had their education put on hold due to COVID-related school closures and, between late March through April of 2020, more than 90% of the total enrolled learners worldwide experienced nationwide school closures and were confined at home. In many ways, adapting to COVID-19 has become a huge, international social experiment that not only has caused loss of learning throughout lockdown but also can be expected to diminish educational opportunities in the long term (Jandric`, 2020 ).

Between March 12 and 27, 2020 a survey of educators from 89 countries identified the following priorities: ensuring academic learning for students, supporting students who lack skills for independent study, providing support for teachers (medical, mental health, professional development), revising graduation policies, ensuring integrity of the assessment process, defining new curricular priorities, and providing social services and food to students (Reimers & Schleicher, 2020 ). Among the concerns identified by this same international group of educators were:

- reduced opportunities for social interaction with extended family, peers, and community members

- threats to the health and safety of students, families, and educators

- financial decisions about education and program viability

- disruptions to the continuity of learning

- limited access to social services and other forms of support for families

- negative effects on students’ perception of the value of study

- drastic reductions in face-to-face teaching and instructional time

- implementation of measures to continue students’ learning during school closure

- teachers’ preparedness to support digital learning

- when and how to reopen schools

- reductions in class size

- mobility of students and legal status of international students

- ways to provide practica, field experiences, and apprenticeships for professionals in training (Reimers & Schleicher, 2020 )

Challenges with Conducting a Literature Review on COVID-19

Reviewing the literature on COVID-19 is, in many ways, atypical. Unlike most other topics, practically every source has been published in 2020 or 2021. Many publications about coronavirus are posted online first; that is why some quotations in this article are designated as “unpaged”—they have been edited, but not yet assigned to a print version of a publication. A second distinguishing feature of the literature about the current pandemic is that it is exceptionally multidisciplinary.

Preparation for this article required searching the COVID-19 literature more expansively to include quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods research; policy documents from respected global and national organizations; literature reviews conducted by professionals representing diverse fields, and resources prepared by prominent professional associations. New and valuable information has increased exponentially. To illustrate, in early 2020, a search using “COVID-19” plus “early childhood education” yielded very little, but, by mid-February of 2021, nearly 20,000 hits were produced by those search terms on Google Scholar alone. The World Organization for Early Childhood, for example, introduced their position paper with the following caveat: “COVID-19 is an emerging, rapidly evolving situation” (OMEP Executive Committee, 2020 ).

What follows are four themes synthesized from the literature review. Each begins with a personal narrative that puts a face on the statistics and highlights important issues in the published scholarly literature. These themes are: (1) threats to quality of life and wellness; (2) intensification of pressure on families and inequities, (3) modifications to teaching and reliance on technology, and (4) restructuring of higher education and scholarship interrupted.

Theme One: Threats to Quality of Life and Human Wellness

In late spring of 2020, the mother and father of two young children tested positive for the virus. Both parents work in the health care field; the mother is a nurse’s aide at a hospital, the father works in a nursing home. Although the couple became very ill, they managed to remain at home and used telehealth video calls to their family physician to get treatment. One of their young children got cold-like symptoms, but they decided not to get her tested because she recovered quickly. Throughout this time, troubling questions surfaced for the parents. How and when did they contract the virus? Would COVID-19 compromise the health of any family members over the long term? Is it inevitable that their son will succumb to the virus, given that they are living in the same house? Did the staff members at the parents’ places of employment quarantine quickly enough to avert an uptick of cases in the community? What will the parents do about home schooling expectations when they are so still so fatigued? How long can the family manage without income from either parent?

This family’s situation highlights two key concepts from positive psychology that are foundational to this discussion of the short- and long-term effects of a world health pandemic: quality of life (QoL) and wellness. Quality of life (QoL) has been the focus of study in psychology since the 1980s. It attempts to answer the question, “What makes it possible, not just to survive and exist, but to thrive and flourish in life?” QoL includes physical and mental health, cognitive functioning, social support, competence in work, and positive emotions such as optimism, wisdom, resilience, and so forth (Efklides & Moraitou, 2013 )—all things that are important to coping with COVID-19 (Burke & Arslan, 2020 ).

Likewise, contemporary concepts of wellness have broadened beyond physical health (i.e., absence of disease or injury). Wellness may be defined as “a way of life oriented toward optimal health and well-being in which mind, body, and spirit are integrated by the individual to live more fully within the human and natural community” (Myers et al., 2000 , p. 252). Anderson’s ( 2016 ) model, for example, categorizes wellness into five broad areas: (1) emotional, (2) social, (3) intellectual, (4) physical, and (5) spiritual. Without a doubt, QoL and wellness worldwide have been impacted by the sweeping changes that children, families, and educators were forced to make within the context of the COVID-19 crisis.

Xafis, 2020 identifies six major influences on the physical and mental health and wellbeing of individuals and groups across time and generations: (1) income and wealth, (2) employment and access to health services, (3) housing, (4) food environment, (5) education, and (6) safety. Clearly, all these things have been affected dramatically by a world pandemic and coping with it on a daily basis over an extended period of time can compromise physical and mental health. As the World Health Organization ( 2020 ) notes, “Fear, worry, and stress are normal responses to perceived or real threats, and at times when we are faced with uncertainty or the unknown. So, it is normal and understandable that people are experiencing fear in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic” (unpaged). Four types of fear that characterize experiences with COVID-19 are: (1) ravages to the body, (2) worries about significant others, (3) intolerance of uncertainty, and (4) agonizing over action/inaction (Schimmenti et al., 2020 ). It is important to understand that anxiety and fear are associated with grief, which is normal and expected following any significant loss or change (Fegert et al., 2020 ). Worldwide, human beings are not only mourning the loss of life as they knew it but also are experiencing anticipatory loss, defined as the expectation that additional, future losses will occur.

Although the COVID-19 global health crisis is unique in some ways, research on the effects of previous quarantines and pandemics—such as the 1918 influenza epidemic–suggest a lasting, negative effect on QoL and wellness (Almond & Mazumder, 2005 ). Another way to glimpse the effects of COVID-19 on early childhood education is to examine scholarly literature, particularly studies that have been completed in countries with more prior experience in managing the disease. A compilation from several reviews of the research literature in different fields (e.g., psychiatry, nursing, forensics) and the documents published by global organizations identified the following problems associated with pandemics, both historical and current:

- Stigmatization of infected children/families and bias against residents in areas of high infection

- Illness, hospitalization, separation, loss of loved ones and caregivers, and bereavement

- Massive re-organization of family life

- Disconnection of children from their peers at school, informal play activities, organized sports, and visits to one another’s homes

- Grief and mourning that may go unrecognized and remain unresolved

- Widespread loss of employment and economic hardship leading to lost housing, further migration, increased displacement, and more family separations

- Escalation of the number of children living in extreme poverty and in food insecure households

- Inability of families to provide consistent care, safe environments, and support education at home

- Increases in the incidence of domestic violence, intimate partner violence, sexual exploitation, and online predatory behavior

- Disruptions to child protective services and delayed recognition of/intervention in rising cases of abuse and neglect

- Higher rates of fear, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicide

- Higher pregnancy rates, poorer prenatal care, and increases in maternal and child mortality and morbidity

- Postponement of health care visits, disruptions to medical treatment, suspension of vaccination programs, and medical supply shortages

- Overconsumption of food and/or unhealthy eating, infrequent vigorous physical activity, excessive screen time, and escalating obesity

- Higher rate of school dropouts resulting in lower educational attainment and possible negative effects on lifelong earnings

- Prolonged periods of isolation that can lead to feelings of loneliness or depression

- Continued avoidance of crowds, enclosed spaces, and physical contact long after quarantine is lifted (Araújo et al., 2020 ; Campbell, 2020 ; Fegert et al. 2020 ; Fisher & Wilder-Smith, 2020 ; Out et al., 2020 ; Peters et al., 2020 ; Rundle et al., 2020 ; United Nations, 2020 ; Usher et al., 2020 ; Van Lancker & Parolin, 2020 ; Witt et al., 2020 ; Yoshikawa et al., 2020 ).

Theme Two: Pressure on Families and Intensification of Inequities

A young family emigrated to the United States from Myanmar several years ago. Both parents work at a Thai restaurant that was closed for months and, even after it reopened, indoor dining was discontinued. As a result, the mother lost her job as a waitress and the father’s work as a cook was limited to weekends only. The couple was proud of the business they had started–a sushi bar on campus—but it failed when the university converted most courses to online delivery. The parents were immediately thrust into home schooling and did not always understand the elementary school teachers’ instructions. Given their tenuous financial situation, the couple started working outdoors—cleaning, pulling weeds, cutting grass, and raking leaves—throughout the summer and fall. Although their children needed supervision to complete school assignments, the parents had to work to meet the family’s most basic needs. They had to rely on neighbors and friends for help and lived in constant fear that they would contract the disease and transmit it to their children.

Contrast them with a young mother whose job consists of providing supplies for events and social gatherings such as weddings, banquets, and so forth. She was unemployed, but her husband’s income was sufficient to sustain the household, his job remained secure, and he was working from home. Everyone in this family had access to their own technological devices, indoor spaces where they could complete their work relatively undisturbed, and a large outdoor area where the family could convene for rest and relaxation. Neither parent had to be exposed to the virus because they could order whatever they needed and pick it up or have it delivered. Although there were some supply chain disruptions, the second family did not experience any food insecurity. They also had family members who were teachers to help. For the first family, the COVID-19 pandemic has been a disaster, made manageable only by the major efforts of their friends and church; for the financially secure family, it was an inconvenience.

The COVID-19 crisis challenges the popular notion of, “We’re all in the same boat.” First of all, the “boats” available to weather that adversity differ dramatically. Some families are cruising in luxury yachts, others are safely harbored in well-equipped houseboats, and still others are in danger of sinking at any moment on makeshift rafts. Secondly, the nature of the “storm” itself is quite different, depending upon the family’s circumstances. Where workers are concerned, first responders and health care workers are living in a tsunami, other essential workers are being buffeted about by stormy seas, and many who can continue fulfil their work duties at a distance from their places of employment have comparatively smooth sailing.

Responsibilities for keeping households disinfected, doing laundry, preparing food, and doing other household chores escalated during lockdown, particularly for women (Action Aid, 2020 ). A study conducted in Italy found that mothers with children in the 0–5 age group found it especially difficult to balance the demands of home and work (Del Boca et al., 2020 ). Parents and families have been thrust into the role of teacher under some of the worst conditions. If the family is home to more than one child, home schooling responsibilities multiply quickly because every day, Monday through Friday, new assignments related to each subject area from various teachers representing different programs keep coming in. Family members often have little or no training in supporting young children’s learning and few resources, but even these limitations are not the hardest part. The most daunting task, according to a study conducted in Italy with parents whose children were on the autism spectrum, is motivating children to learn and to complete assigned tasks (Degli Espinosa et al., 2020 ). Even the things that could be used as rewards for children were suddenly off limits, such as playing with friends or going on an outing. Thus, parents during lockdown described having difficulties with balancing responsibilities, motivating their children, accessing online materials, and producing satisfactory learning outcomes (Garbe et al., 2020 ; Waddoups et al., 2019 ). To further compound learning losses, many young children have been deprived of a year or more of regular interactions with groups of peers that promote social and emotional development.

All the COVID-related challenges are exacerbated among the vulnerable (Ambrose, 2020 ), defined as “those individuals and groups routinely disadvantaged by the social injustice created by the misdistribution of power, money, and resources” (Xafis, 2020 , p. 224). They include, but are not limited to indigenous peoples, those living in poverty, residents of rural/remote communities; those experiencing job and housing insecurity; people experiencing chronic mental illness, disabilities, or dependence on substances; prisoners; newly arrived migrants; refugees as well as displaced populations, stateless people, and migrant workers (Xafis et al., 2020 ). The suspension of childcare services due to isolation measures exacted the highest toll on families who were already struggling, and these families are most likely to experience severe, long-term deleterious effects.

Even the steps taken to protect the family–such as frequent hand washing, maintaining physical distance, and wearing personal protective equipment–were out of reach for some. Such issues were not limited to countries that lack an infrastructure for water, energy, finances, and health and education services. Wealthy countries, such as the United States, are home to young children living in extreme vulnerability, including those who are hungry, neglected, and abused. Many of the services that these children depended upon, such as healthful meals, social services, and educational interventions came to a halt with quarantine, lockdown, and physical distancing measures. Sadly, for children living in extreme adversity, early childhood programs frequently were their only respite and children lost their safe havens. Even among children whose basic needs are routinely met, educational vulnerability persists: “Preschool and children in early primary grades are most vulnerable as they often do not respond to online learning and are at a critical time of social, cognitive, and intellectual development” (Silverman et al., 2020 , p. 463). Not all parents accepted the switch to online learning; a study in China found that parents resisted or even rejected it because they felt it was ineffective, that their young children were not sufficiently independent as learners to benefit from it, and that the parents themselves had neither the time nor expertise to accept a teaching role (Dong et al., 2020 ). Social-emotional vulnerability is another concern for young children. Early childhood is a critical period for learning how to deal with powerful emotions and to build skills that support positive interactions with others.

Vulnerable too are the childcare workers, who are underpaid, without health insurance, have no paid leave, became unemployed during the shutdown, and may see the programs that they worked for close, particularly if those programs depended on tuition support from families for their existence (Ali et al., 2020 ).

Theme 3: Modifications to Teaching and Reliance on Technology

A graduate level course was converted to online Zoom meetings during the lockdown. After several class meetings, one student asked another gently, “Could I ask you a question? You don’t have to answer if you don’t want to. Why are you in the garage with your phone when we meet online for class?” The student smiled and replied, “No problem—that is easy to answer. Our internet service in this rural area is not that great. The garage gets the best reception. Besides, I have younger siblings who are doing home schooling and they are using the desktop computer. They are a big distraction!