Grammar , Vocabulary

Useful Chinese Essay Phrases

July 8, 2020

By Ellen

Nowadays, many international students have decided to study abroad, and China has become a highly popular destination. In universities, essay writing is a basic skill and the “Academic Writing” lectures are always attracting many students to attend.

Here we have summarized some “all-purpose” phrases and sentences which hopefully you would find useful.

Chinese Essay Phrases Used in Abstracts

The abstract should explain the purpose, method, results, and conclusion of your research, also highlighting the new ideas that you proposed; and do remember to keep your language concise while writing. The purpose of the abstract is to conclude and summarize the main contents of your essay so that the reader could have a brief understanding without having to read the entire paper. Chinese abstracts are usually around 200 characters.

Research Background, Significance, and Current Situation

Extremely useful/badly needed/affecting people’s lives (1-2 sentences)

| 对…有贡献 | contribute to |

| 主要原因 | major cause |

| 至关重要 | crucial/essential |

| 重要影响 | profound impact |

| 在…中起中心/重要作用 | play central/important roles in |

| X已经被深入研究了其在…中的作用 | X has been intensively studied for its role in… |

| X因其Z性质/特性引起了Y的极大兴趣 | X aroused great interest of Y due to its Z nature/characteristics |

Proposing the Object of Study

Played a very important role (1-2 sentences)

| 本文提出了一种针对…来…的方法。 | This paper proposes a method/approach focusing on…to… |

| 我们提出了一种…,它使我们能够…… | We presented a new…, which enables us to… |

| 本文介绍几种针对…进行改进的…模型。 | This paper introduces several improved…models focused on… |

| X是一种非常有吸引力的方式以/来…… | X is a highly attractive method to/for… |

| 但其在…中的潜在作用却鲜为人知。 | But little is known about their potential role in… |

Purpose of the Study or Study Aim

The role of A in B, perhaps remains to be seen (1 sentence)

| 本文的意图是…… | The intention/purpose of this paper is to… |

| 本文的目的是…… | The purpose/goal/objective/object/aim of this paper is to… |

| 本文/研究/试验的主要目标是…… | The chief aim of this paper/research (study)/experiment is to… |

| 我们的研究重点是…… | Our research focuses on… |

| 该实验旨在回答/解决…的问题 | The experiment aims to answer the question/solve the problem of… |

Research Methods and Results

Through what means/technique/experiment we achieved what result (several sentences)

| 为了实现这一目标,我们研究了…的作用。 | To achieve this aim, we have examined the role of… |

| 通过这一研究,我们发现/证明/观察到…… | Through this study, we found/demonstrated/observed that… |

| 因此,我们的研究使用了X技术/方法/策略来…… | Therefore, our study used X technology/method/strategy to… |

| X技术/方法/策略被用于……检测/识别 | X technology/method/strategy was used to detect/identify… |

| X的效果/作用由Y进行确定/分析/检验 | The effects/roles of X were determined/analyzed/examined by Y |

| 然而由于X以及Y, 因此这一问题仍然有待深入研究… | However, due to X and Y, this issue still requires to be further studied… |

Research Results

The phenomenon of A in B, shows what the function of B is, theoretical and applied value (1-2 sentences)

| 本文的发现/结果表明…… | The findings/results of this paper indicate that… |

| 本研究证明了X的…能力 | This research demonstrates the ability of X to… |

| 本文证明,X能够有效地准确地…… | This paper demonstrates that X could effectively and accurately... |

| X有潜力来/能够…… | X has the potential to... |

via Pixabay

Chinese Essay Phrases: Main Body

The main body includes the introduction and the main text. The introduction section could use similar phrases that we have just listed, focusing on research objects and purposes. The main text should include research methods, research results, and discussion. Writers should keep their sentences to the point and avoid rambling, also avoid using too much subjective perspective discourses, which shouldn’t be used as arguments as well.

Theoretical Basis, Approaches, and Methods

| 这是一项基于…的研究。 | This is a study that is based on… |

| 我们在研究中采用的方法被称为…… | The method used in our study is known as … |

| 我们采用的技术被称为…… | The technique that we applied is known as … |

| 我们所述的问题涉及对…的研究。 | The problem we have outlined deals with the study of … |

| 我们所做的实验旨在获取关于…的结果。 | The experiment we conducted is aimed at obtaining the results of… |

| 实验内容包括…… | The experiments included… |

| 我们开展了大量实验以研究…… | We conducted many experiments to study… |

| 我们进行了针对X的实验,以测量/衡量…… | We conducted experiments focused on X to measure… |

| 我们进行了一系列实验以测试…的有效性。 | We ran a series of experiments to test the validity of… |

| 这个例子体现了…… | This example illustrates… |

| 这个现象说明了…… | This phenomenon shows that… |

| 这个活动表明了…… | This activity makes it clear that… |

To Express Opinions

| 就我/个人而言 | As far as I’m concerned |

| 不可否认的是 | It is undeniable that |

| 一种完全不同的论点/观点/看法是 | A completely different argument/perspective/view is |

| 这是一个有争议性的问题 | This is a controversial issue |

To Emphasis

| 有充分的理由支持 | be supported by sound reasons |

| 发挥着日益重要的作用 | play an increasingly important role in |

| 对……有利/不利的影响 | have a positive/negative influence on... |

| 考虑到诸多因素 | take many factors into consideration |

| 可靠的信息来源 | a reliable source of information |

Transitional Expressions

| 比方说/比如/例如 | For example/For instance |

| 由此可见 | This shows/Thus it can be seen |

| 尽管如此 | In spite of this/even so |

| 但是/不过/然而 | However/but |

| 另外/此外/除此之外 | In addition to/besides |

| 不管怎样/无论如何 | At all events/in any case/anyway |

| 最重要的是 | Above all/most important of all |

Chinese Essay Phrases: Conclusion

At the ending section of the paper, the writer should provide an objective summary, list out the future research objectives and directions, and perhaps look into the future. Keep optimistic even if your experiment results were negative.

| 本文阐述了关于…的…… | This paper illustrates the…regarding… |

| 我们得到了关于…的详细信息/有价值的数据。 | We have obtained detailed information/valuable data regarding… |

| 我们所做的研究揭示/验证了…… | The research that we have done reveals/confirms that… |

| 我们所做的实验表明/证明…… | The experiments that we have done showed/proved that… |

| 通过这项研究/实验,作者认识到…… | Through this study/experiment, the author came to realize that… |

| 这项研究/实验得出的结论是…… | This study/experiment comes to the conclusion that… |

Research Impact and Value

| 我们的发现/研究结果有助于揭示/解释…… | Our findings/research results help to reveal/explain… |

| 这项研究使我们发现…… | This study leads us to the discovery of… |

| 这项研究能够解决由X引起的Y问题。 | This study can solve the Y problem caused by X. |

| 本文的理论/实际价值在于…… | The theoretical/practical value of this paper lies in… |

There you go. We hope this article helps you write amazing essays. Best of luck!

Ellen is a language specialist from China. She grew up in the US and received a master’s degree from the St Andrews University of UK. The multicultural experiences attributes to her understanding of the differences and similarities between the English and Chinese language. She currently works as an editor specialized in Language learning books.

related posts:

Must-Try Authentic Chinese Dishes

15 must-watch chinese movies for language learners, best chinese music playlists on spotify, get in touch.

Improve Chinese Essay Writing- A Complete How to Guide

- Last updated: June 6, 2019

- Learn Chinese

Writing can reflect a writer’s power of thought and language organization skills. It is critical to master Chinese writing if you want to take your Chinese to the next level. How to write good Chinese essays? The following six steps will improve Chinese essay writing:

Before You Learn to Improve Chinese Essay Writing

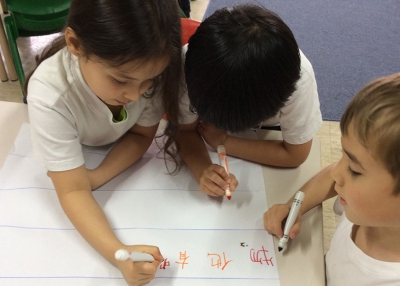

Before you can write a good essay in Chinese, you must first be accustomed with Chinese characters. Unlike English letters, Chinese characters are hieroglyphs, and the individual strokes are different from each other. It is important to be comfortable with writing Chinese characters in order to write essays well in Chinese. Make sure to use Chinese essay writing format properly. After that, you will be ready to improve Chinese essay writing.

Increase Your Chinese Words Vocabulary

With approximately 100,000 words in the Chinese language, you will need to learn several thousand words just to know the most common words used. It is essential to learn as many Chinese words as possible if you wish to be a good writer. How can you enlarge your vocabulary? Try to accumulate words by reading daily and monthly. Memory is also very necessary for expanding vocabulary. We should form a good habit of exercising and reciting as more as we can so that to enlarge vocabulary. Remember to use what you have learned when you write in Chinese so that you will continually be progressing in your language-learning efforts.

Acquire Grammar,Sentence Patterns and Function Words

In order to hone your Chinese writing skills , you must learn the grammar and sentence patterns. Grammar involves words, phrases, and the structure of the sentences you form. There are two different categories of Chinese words: functional and lexical. Chinese phrases can be categorized as subject-predicate phrases (SP), verb-object phrases (VO), and co-ordinate phrases (CO). Regarding sentence structure, each Chinese sentence includes predicate, object, subject, and adverbial attributes. In addition, function words play an important role in Chinese semantic understanding, so try to master the Chinese conjunction, such as conjunction、Adverbs、Preposition as much as you can. If you wish to become proficient at writing in Chinese, you must study all of the aspects of grammar mentioned in this section.

Keep a Diary Regularly to Note Down Chinese Words,Chinese Letters

Another thing that will aid you in becoming a better writer is keeping a journal in Chinese. Even if you are not interested in expanding your writing skills, you will find that it is beneficial for many day-to-day tasks, such as completing work reports or composing an email. Journaling on a regular basis will help you form the habit of writing, which will make it feel less like a chore. You may enjoy expressing yourself in various ways by writing; for instance, you might write poetry in your journal. On a more practical side of things, you might prefer to simply use your journal as a way to purposely build your vocabulary .

Persistence in Reading Everyday

In addition to expanding your view of the world and yourself, reading can help you improve your writing. Reading allows you to learn by example; if you read Chinese daily, you will find that it is easier to write in Chinese because you have a greater scope of what you can do with the vocabulary that you’ve learned. Choose one favorite Chinese reading , Read it for an hour or 2,000 words or so in length each day.

Whenever you come across words or phrases in your reading that you don’t understand, take the time to check them in your dictionary and solidify your understanding of them. In your notebook, write the new word or phrase and create an example sentence using that new addition to your vocabulary. If you are unsure how to use it in a sentence, you can simply copy the sample sentence in your dictionary.

Reviewing the new vocabulary word is a good way to improve your memory of it; do this often to become familiar with these new words. The content of reading can be very broad. It can be from novels, or newspapers, and it can be about subjects like economics or psychology. Remember you should read about things you are interested in. After a certain period of accumulation by reading, you will greatly improve your Chinese writing.

Do Essay Writing Exercise on a Variety of Subjects

As the saying goes, “practice makes perfect.” In order to improve your China Essay Writing , you should engage in a variety of writing exercises. For beginners, you should start with basic topics such as your favorite hobby, future plans, favorite vacation spot, or any other topic that you can write about without difficulty.

For example :《我的一天》( Wǒ de yì tiān, my whole day’s life ),《我喜欢的食物》( Wǒ xǐhuan de shíwù, my favorite food ),《一次难忘的旅行》( yí cì nánwàng de lǚxíng, an unforgettable trip ) etc.

Generally the writing topics can be classified into these categories: a recount of an incident,a description of something/someone, a letter, formulate your own opinion on an issue based on some quote or picture etc.

Takeaway to Improve Chinese Essay Writing

Keep an excel spreadsheet of 口语(Kǒuyǔ, spoken Chinese) –书面语(Shūmiànyǔ, written Chinese) pairs and quotes of sentences that you like. You should also be marking up books and articles that you read looking for new ways of expressing ideas. Using Chinese-Chinese dictionaries is really good for learning how to describe things in Chinese.

Online Chinese Tutors

- 1:1 online tutoring

- 100% native professional tutors

- For all levels

- Flexible schedule

- More effective

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share via Email

Qin Chen focuses on teaching Chinese and language acquisition. She is willing to introduce more about Chinese learning ways and skills. Now, she is working as Mandarin teacher at All Mandarin .

You May Also Like

This Post Has 3 Comments

When I used the service of pro essay reviews, I was expecting to have the work which is completely error free and have best quality. I asked them to show me the working samples they have and also their term and condition. They provided me the best samples and i was ready to hire them for my work then.

This is fascinating article, thank you!

Thank you so much for sharing this type of content. That’s really useful for people who want to start learning chinese language. I hope that you will continue sharing your experience.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

How to Write a Chinese Essay

Dec 16, 2020 | Guest Blogs & Media

The more essays you write, the better you get at communicating with Chinese. To write a good essay, you first have to reach a high language mastery level.

Do you admire the students who write seamless Chinese essay? If you do, then you should know that you too can achieve this level of proficiency. In the meantime, don’t be afraid to pay for your essay if you cannot write it on your own. Online academic writers are a resource each student should take advantage of.

Here are tips to help you get better at writing essays in Chinese.

Learn New Chinese Words

The key to communicating in a new language is learning as many words as you can. Take it upon yourself to learn at least one Chinese word a day. Chinese words are to essay writing what bricks are to a building. The more words you have, the better you get at constructing meaningful sentences.

Case in point, if you’re going to write a Chinese sentence that constitutes ten words, but you don’t know the right way to spell three of those words, your sentence might end up not making sense.

During your Chinese learning experience, words are your arsenal and don’t forget to master the meaning of each word you learn.

Read Chinese Literature

Reading is the most effective way of learning a new language. Remember not to read for the sake of it; find out the meaning of each new word you encounter. When you are an avid reader of Chinese literature, nothing can stop you from writing fluent Chinese.

In the beginning, it might seem like you’re not making any progress, but after a while, you will notice how drastically your writing will change. Receiving information in Chinese helps your brain get accustomed to the language’s sentence patterns, and you can translate this to your essays.

Be extensive in your reading to ensure you get as much as possible out of each article. Remember that it’s not about how fast you finish an article, but rather, how much you gain from the exercise.

Translate Articles from your Native Language to Chinese

Have you ever thought about translating your favorite read to Chinese? This exercise might be tedious, but you will learn a lot from it. The art of translation allows you to seamlessly shift from one language’s sentence pattern into the other. The more you do this, the easier it will be for your brain to convert English sentences into Chinese phrases that people can comprehend.

You can always show your Chinese professor your translations for positive criticism. The more you get corrected, the better you will get at translation. Who knows, you might actually like being a translator once you graduate.

Final Thoughts

by Adrian Lomezzo

Adrian Lomezzo is a freelance writer. Firstly, he has been developing as a content manager and working with different websites, and the main goal of his was to develop the content making it in the first place. Secondly, Adrian had a big desire to help students and adults in self-development in this field and teach them to improve their skills. As a lover of traveling, he did not want to be in one place, and became a writer who could be closer to everyone, and share precious information from the corners of the world.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Submit Comment

Other posts you might like

Congratulations That’s Mandarin Winter 2022 Graduates

Mar 31, 2022 | Beijing , News

We’re so excited and proud to see our students achieve goals and improve their Chinese skills at That’s Mandarin. We know how hardworking and diligent you are and we are happy to go through this incredible and at times difficult process of learning Chinese together...

News: NihaoKids Website Is Live!

Mar 3, 2022 | News , Online

A modern place for your children to learn Mandarin Chinese.

Mahjong Night Recap (Feb 23)

Feb 24, 2022 | Beijing , News , Shanghai

The best moments of Mahjong Night!

Get 2-week FREE Chinese Classes

Original Price: ¥ 600

The Guide to Writing Your First Mandarin Essay

When you want to be able to make writing your first Mandarin essay nice and easy, it pays to put plenty of thought and effort into the preparation. As the old saying goes ‘fail to prepare, prepare to fail.’ To give you plenty of food for thought we’ve put together everything you need to know to get things moving. All you need to do is work through the following steps, and you’ll be submitting your essay in no time at all.

Check you understand the basics

There are so many things you have to think about when writing an essay, particularly when it’s not in your native language. But as with any cognitively demanding task, the process for getting started is always the same. Check you understand the following basics and you’ll be heading in the right direction:

- Do you know what the question means?

- Have you made a note of the final submission date?

- Make sure you read some past examples to get a feel for what’s expected of you

- Do you understand the question that has been set?

- Do you know who you can talk to if you need advice along the way?

- Are there any restrictions on the dialect you should be aware of?

Once you can write the answers to the above down on a single side of the paper, you are ready to tackle the main part of the problem: putting pen to paper.

Set aside time to write

The chances are that you’re not going to be able to pen the entire essay in a single sitting, and that’s okay. It’s nothing to be ashamed of or to worry about, and it’s natural that you need to work across multiple days when writing your first essay.

If you want to be able to make great progress, the most important thing is sticking to a routine. You need to have consistency in your application, and you need to be able to know when you are at your most productive. It’s no good staying up late one night and then carrying on early the next morning. You’d be far better off writing for the same amount of time but on two successive afternoons. Think about how your studies fit in with the rest of your daily life, and then choose the time that seems most appropriate. If you box it off and decide it’s only for writing, you’ll be in a great routine before you even know it.

Clear space so you can focus

As well as having time to write each day, you need a place to write too. The world is full of distractions (most of them are digital and social) so that means you’re going to want to keep yourself to yourself, and your phone in a different room. It might seem a little boring or uncomfortable at first, but you need to practice the habit of deep work. It’s what will allow you to create the most in the shortest time — ideal if you want to have plenty of time leftover to spend doing the other things that matter to you.

Have a daily word count in mind

Telling yourself that you want to write an essay today is one thing, but if you’re really going to push yourself to stick to your goal then you need to get quantitative. If you have a word count in mind that you need to hit, then it will prevent you from giving up and throwing in the towel the minute you start having to think and concentrate more than feels normal. Just like working out in the gym, it’s the temporary moments of extra effort that really drive the big differences. It’s when you’ll see the biggest improvement in your writing ability, and the lessons you teach yourself will stay with you for years to come. Ideal if you want to become a fluent Mandarin writer, as well as an engaging face-to-face speaker.

Read widely to provide context

When you’re immersed in an essay it can be all too easy to become blinkered and fail to pay attention to everything else that’s going on around you. Of course, you want to be focused on the task at hand, but you don’t want to be single-minded to the point of ignoring other great learning resources that are just a click away.

Reading widely is one of the best ways to improve your essay writing because it exposes you to techniques and approaches used by the best of the best. You’re not expected to be able to instantly write like a native speaker after an hour of reading. But what you will be able to do with consistent application is build up confidence and familiarity with written Mandarin. Over time this will reflect on the quality and depth of your writing as you gradually improve and take onboard lessons you’ve learned.

Take a break before you proofread

Last but not least, you need to remember that essay writing is a marathon, not a sprint. It’s all about taking the time to get things written before you hand them in, not racing through to try and finish on time. If you want to get the most out of your writing you need to take a day off between finishing your draft and proofing it. That way your brain will have had plenty of time to reflect on the work you’ve produced, and you’ll be able to spot many more little mistakes and places for improvement than you would if you proofed right away.

Final Thoughts

Writing Mandarin is a challenging task that will test your language skills and make you think hard about how to apply what you’ve learned so far. It might be slow going to begin with, but that’s great as it means you’re pushing your limits and building on your existing skills. If you want to be able to master Mandarin, you need to persevere and stay the course. Once you do, you’ll start to improve a lot faster than you expect.

By Diana Adjadj | A Super Chineasian

You may also like

Learn 5 Chinese Words Related to Ghost Month & Taboos to Avoid

5 Chinese Words for Must-Try Exotic Summer Fruits

4 Rules of Pronouncing “一” in Chinese: Improve Your Accuracy Today

Tell your chineasy stories.

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Copyright © 2024 Chineasy. All rights reserved.

- Be a Member

- English French Chinese

- General Chinese learning tips

How to Write a Good Chinese Essay

Posted by Lilian Li 18424

For any kind of language, the essay is the most difficult thing to do in the exam. Generally speaking, writing articles is just to tell a story, after you make the story clear, the article also is finished. But it also different with speaking. A good article is like a art, is worth for people to appreciate, to taste. But how to accomplish such a good art? I think the most important thing is the three points: attitude, subject matter, emotional.

A good beginning is half done. For writing, material selection and design are not the start. The most important thing still is to adjust their mentality as well. When you decided to write, then dedicated yourself to write, not half-hearted, and your thinking nature won't be upset. Once the train of thought was interrupted, your speed will be slow and the point will be word count. So how can you write down a interesting article with a good quality? All in all, attitude is can decide the success or failure of the articles.

Subject is the biggest problem in our writing. It is from life, but not all people can observe life, experience life. The only point is to write the true things, maybe not so tortuous plots, but can write a really life. Moreover, when you get the subject, there are some tips for students to pay attention:

1. Make the topic request clear: The article should around the topic, pay attention to the demand of genre and number of words, some restrictive conditions and avoid distracting, digression.

2. Determine the center, choose the right material. To conform to the fact that a typical, novel, so it’s easy to attract the attention of people.

3. Make a good outline, determine the general, write enough words.

4. Sentence writing smooth, there is no wrong character, no wrong grammar in article.

Emotion, it is very important. If we compared an article to be a human. So emotion is his soul. Man is not vegetation, when they meet something, there must be personal thoughts and feelings. Sometimes it also tend to have their own original ideas. If you can put your own thoughts, feelings and insights into the article, then this article will be very individual.

Chinese essay is not just meaning some simple Chinese characters and make a simple sentences, it needs the Chinese grammar and sentence structure, if you don't familiar with Chinese grammar, you can learn our Chinese grammar course .

At last, adhere to write diary at ordinary times, it can practicing writing. Try to read some good articles, good words and good paragraphs with a good beginning and end. Learn to accumulate and draw lessons from them.

If you are interested in our Chinese grammar course, you can try our one online free trial , you will enjoy it.

About The Author

Related articles.

Free Trial

Self-test

Concat Us

Chat online

Share Us

Want to receive regular Chinese language tips & trivia?

How to Write a Chinese Essay?

However, this is not an option.

Chinese essay writing is an important part in GCE O level Higher Chinese Language or Chinese Language exam.

Then, what are the students suppose to write in an essay? For GCE O level Chinese exam in May 2017, many parents complained about the essay questions set were too difficult ( link ). However, this is the direction we are heading in O level Chinese and the students need to level up necessarily.

Before we even talk about what to write, we must first know what will be tested.

For GCE O level Chinese exam , essay writing is in section 2 of Paper 1.

In this section, students are expected to choose to write 1 out of 3 questions, and the 3 questions will be in one of the following categories:

- 情景文 (Scenario essay writing)

- 说明文 (Expository)

- 议论文 (Argumentative)

- 材料作文 (Material essay writing)

Each category would need students to write the essay using different skill set. Students need to master the required skill set in order to write essays that meet the criteria.

For 情景文 , students need to use the skills of writing 记叙文 and characters descriptions ; for 说明文 , they need to use the skills of expository essay writing ; 议论文 needs the 3 key elements; as for 材料作文 , depending on the question, students will either need to use the skills for 记叙文 or 议论文 .

When students are clear with all these skills, they will find Chinese essay writing a lot more easier. When equipped with these necessary writing skills , they will be able to focus more on acquiring their language skills.

With our help, we are confident that our students are able to master all these essential Chinese essay writing skills.

Call 97690373 today to register for our class.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Chinese Reading Practice

Fable: 牧师和信徒 – the priest and the disciple.

- Post author By Kendra

- Post date March 27, 2023

- 7 Comments on Fable: 牧师和信徒 – The priest and the disciple

The moral of this short story, of course, is that faith burns more brightly the more people share it with each other.

- Tags Myths & Fables

Essay: 《不死鸟》The Immortal Bird by Sanmao

- Post date March 25, 2023

- 5 Comments on Essay: 《不死鸟》The Immortal Bird by Sanmao

In this tear-jerker essay, famous Taiwanese authoress Sanmao ponders on the value of her own life. It was written as she grieved the drowning of her beloved Spanish husband in 1979, and is all the more tragic in light of her suicide 12 years later.

- Tags Essays

Fable: 洗衣服 – Washing clothes

- Post date July 19, 2020

- 23 Comments on Fable: 洗衣服 – Washing clothes

In this quick lesson about judging others, we learn that those who live in dirty glass houses shouldn’t throw stones. HSK 2-3.

Short Story: 海上和床上 – On the sea and in bed

- Post date June 25, 2020

- 26 Comments on Short Story: 海上和床上 – On the sea and in bed

This dialogue between a man and a sailor drives home a quick life lesson: there’s risk in anything you do, so there’s no point in trying to avoid danger entirely. HSK 2-3.

- Tags Children's Stories

Working to get CRP back online

- Post date June 22, 2020

- 9 Comments on Working to get CRP back online

Hey crew – we’ve had some pretty nasty technical difficulties over here at CRP when moving a server. I’m working to get all these stories back online. Data was corrupted in the middle of a server switch, and the posts are a bit of a mess. Hoping to have it fixed by the end of the week. Sorry for the wait!

Fable:《和尚背女人》Monks carrying a woman

- Post date June 17, 2020

- 4 Comments on Fable:《和尚背女人》Monks carrying a woman

An elder monk gives a younger monk a quick lesson in following the spirit of the law, rather than the letter of the law. HSK 4-5.

Children’s Story:《两条彩虹》Two rainbows

- Post date June 16, 2020

- 1 Comment on Children’s Story:《两条彩虹》Two rainbows

In this cutsey-face story intended for kindergarteners, Grandma Bear (熊奶奶 – xióng nǎi nai) comes down with an illness that can only be cured by seeing a rainbow (彩虹 -cǎi hóng), and Uncle Frog (青蛙大叔 – qīng wā dà shū) jumps in to make it happen. HSK 2-3.

News: Drunk woman breaks airplane window with fist causing emergency landing

- Post date June 15, 2020

- 1 Comment on News: Drunk woman breaks airplane window with fist causing emergency landing

Binge drinking, breakups and air travel don’t mix, people. HSK 6 and up.

Fable: 郑人买履 – A man from the State of Zheng buys shoes

- 3 Comments on Fable: 郑人买履 – A man from the State of Zheng buys shoes

A not-too-bright fellow heads to the market to buy a pair of shoes. Includes a beginner’s introduction to classical Chinese. HSK 3.

Essay:《爱》Love by Zhang Ailing (Eileen Chang)

- Post date June 12, 2020

- 8 Comments on Essay:《爱》Love by Zhang Ailing (Eileen Chang)

A tragic, dreamlike little essay from writer Zhang Ailing (张爱玲, English name Eileen Chang) about love and destiny. This is one of her more well-known works of micro-prose, written in 1944. HSK 5-6.

Children’s Story: 完美的弓 – The perfect (archery) bow

- Post date June 11, 2020

- 5 Comments on Children’s Story: 完美的弓 – The perfect (archery) bow

A man tries to make his treasured hunting bow (弓 gōng) even more perfect than it already is, but learns an obnoxious life lesson instead. HSK 3-4.

Essay:《打人》Hitting Someone by Zhang Ailing (Eileen Chang)

- Post date June 10, 2020

- 3 Comments on Essay:《打人》Hitting Someone by Zhang Ailing (Eileen Chang)

An essay from Chinese lit diva Zhang Ailing about a scene of police brutality she witnessed in Shanghai in the 1940s. HSK 6 and up.

Story behind the idiom: 狐假虎威 – Using powerful connections to intimidate others

- Post date June 5, 2020

- 8 Comments on Story behind the idiom: 狐假虎威 – Using powerful connections to intimidate others

In this HSK 3-4 story, a crafty fox (狐狸 hú li) escapes being eaten by playing a cunning trick on a mighty tiger (老虎 lǎo hǔ).

- Tags Idioms

Mythology: 八仙过海 – The Eight Immortals Cross the Sea

- Post date June 4, 2020

- No Comments on Mythology: 八仙过海 – The Eight Immortals Cross the Sea

I’ve got a good, but challenging, read for HSK 6 readers today: the Eight Immortals mess around in the Dragon King’s domain, almost starting a cataclysm in the process. HSK 5-6.

Story behind the idiom: 邯郸学步 – Making oneself ridiculous by slavishly imitating others

- Post date June 3, 2020

- No Comments on Story behind the idiom: 邯郸学步 – Making oneself ridiculous by slavishly imitating others

A young man tries to copy the way people walk in the city of Handan (邯郸), but only succeeds in making a fool of himself. HSK 3-4.

Novels: Start reading Chinese gangster novel 《一半是火焰,一半是海水》by Wang Shuo

- Post date June 2, 2020

- 2 Comments on Novels: Start reading Chinese gangster novel 《一半是火焰,一半是海水》by Wang Shuo

In my most challenging post yet, you’ll read the first chapter of controversial literary bad boy Wang Shuo’s dark plunge into the criminal underbelly of Beijing. HSK 6+, not suitable for children.

- Tags Novels

Short story: 《卜妻为裤》Buzi’s wife makes a pair of pants

- Post date June 1, 2020

- 3 Comments on Short story: 《卜妻为裤》Buzi’s wife makes a pair of pants

A gentleman named Buzi (卜子) asks his wife (卜妻) to make him a new pair of pants (裤子), but he doesn’t give her very clear instructions. HSK 3-4.

Communist folk tales: 《水缸的秘密》- The secret of the water jug

- Post date May 29, 2020

- 4 Comments on Communist folk tales: 《水缸的秘密》- The secret of the water jug

Our last Communist-themed post for the week: a classic revolutionary-era story about the man himself, Chairman Mao. HSK 4-5.

- Tags Politics & Communism

Communist folk tales: 《朱德的扁担》- Zhu De’s Carrying Pole

- Post date May 28, 2020

- No Comments on Communist folk tales: 《朱德的扁担》- Zhu De’s Carrying Pole

Zhu De (朱德) is an early Communist folk hero, and the founder of the People’s Liberation Army (解放军), also called the Red Army (红军). This popular revolutionary story highlights his willingness to toil alongside the rank and file soldiers. HSK 3-4.

- Tags Biography , Politics & Communism

Political speech: Deng Xiaoping addresses the Hong Kong handover in 1984

- Post date May 27, 2020

- 10 Comments on Political speech: Deng Xiaoping addresses the Hong Kong handover in 1984

In June, 1984, thirteen years before the Hong Kong handover, he gave this speech, addressing critics of the “One Country, Two Systems” (一个国家,两种制度)policy, which determined China’s approach to the handover. The policy maintained that different political systems would concurrently be implemented under one government. In other words, that mainland China would remain socialist, and that Hong Kong would remain capitalist (until 2047, anyway), but both would be ultimately overseen by the CCP. It was a radical notion at the time, and it still is in many ways. His words here are a fascinating look into the past.

- Tags History , Politics & Communism

Stack Exchange Network

Stack Exchange network consists of 183 Q&A communities including Stack Overflow , the largest, most trusted online community for developers to learn, share their knowledge, and build their careers.

Q&A for work

Connect and share knowledge within a single location that is structured and easy to search.

How do native speakers structure their essays?

When analyzing Chinese speeches or essays, I often have difficulty understanding how their the authors organized their ideas.

In North America, for example, a common template for writing an essay is the five-paragraph essay . This organizes the paragraphs and the sentences within each paragraph. Most English-language writing in academia follows a somewhat similar structure to this.

Do Chinese follow any particular structures when planning speeches or essays? Are there any ancient scholars who heavily influenced this structure?

- whoa, nice question. i really hope someone can dig up some information about this. – magnetar Commented Dec 25, 2011 at 21:13

- 1 You might want to provide some examples. It might be that the authors really didn't follow any specific structures, either because they are very good at their job, or because they are utterly incompetent. – Wang Dingwei Commented Dec 30, 2014 at 0:58

- 1 I have never seen a five-paragraph essay in English-speaking media. It's more like training wheels for high school writers. – K Man Commented Nov 16, 2019 at 13:31

- very helpful, i really liked it. thank you. you helped me a lot on my essay – verynicepost Commented Feb 22, 2021 at 13:21

2 Answers 2

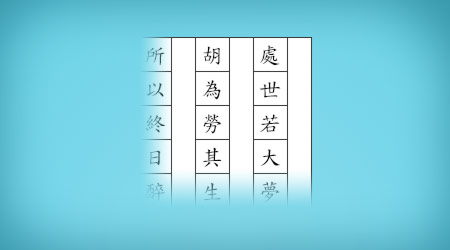

The Chinese have a device called 起承转合 . First you start (起) narrating on some topic. Then you continue (承) to develop the topic with added material. Then you turn (转) the narrative, either by seeking different aspects, or creating conflicts and resolving them. Finally you conclude (合) the topic.

Often it goes like this:

It also work in poems and songs. Here is a modern example, a song by by 张玮玮, titled 《织毛衣》

This idea has its classic roots, so we can see it being used in classical poems as well. For example, 《登高》 by 杜甫, my all time favorite:

It's rather akin to the Hollywood three-act structure , where you plan the plot, develop the plot, reach the climax, then draw the happy ending.

Note that it's just one of the common devices that could be used on any type of writing. As for scientific theses, I think most of them try to follow western standards.

- also interesting to consider possible influence of 八股文 /时文 on this kind of organization... – Master Sparkles Commented Dec 29, 2014 at 22:00

- @MasterSparkles Yeah how can we forget 八股文 ? Though it's almost certainly dead, it did have served its time. – Wang Dingwei Commented Dec 30, 2014 at 0:23

- yup, it has a largely deserved bad rep, but it's hard to imagine that baguwen training didn't strongly influence late Qing reformers' ideas about what to replace the form with. The Wikipedia article weirdly fails to mention Dr Benjamin Elman's "A Cultural History of Civil Examinations in Late Imperial China" - late chapters of which detail baguwen's downfall. I don't know if anyone has gone back and studied if/how that influence played out regarding teaching Chinese composition. – Master Sparkles Commented Dec 30, 2014 at 1:02

In university I had to write quite a few essays in Chinese, they follow the same basic structure of introduction, point 1, point 2, point... conculusion.

I have also spent time correcting thesis and academic writing and it's pretty much identical to in the West.

One point about learning to write better in Chinese that my wife taught me; don't get hung up on how to write something properly in Chinese. Thing about exactly what you want to say in your native tongue (English etc.) and then think about how to translate that into Chinese rather than going for the tricky approach of trying to get your point across in Chinese.

Your Answer

Sign up or log in, post as a guest.

Required, but never shown

By clicking “Post Your Answer”, you agree to our terms of service and acknowledge you have read our privacy policy .

Not the answer you're looking for? Browse other questions tagged writing academic or ask your own question .

- Featured on Meta

- Bringing clarity to status tag usage on meta sites

- We've made changes to our Terms of Service & Privacy Policy - July 2024

- Announcing a change to the data-dump process

Hot Network Questions

- Polar coordinate plot incorrectly plotting with PGF Plots

- Does each unique instance of Nietzsche's superman have the same virtues and values?

- Dial “M” for murder

- What is the meaning of "Exit, pursued by a bear"?

- Age is just a number!

- QGIS selecting multiple features per each feature, based on attribute value of each feature

- Venus’ LIP period starts today, can we save the Venusians?

- Very old fantasy adventure movie where the princess is captured by evil, for evil, and turned evil

- Colorless Higgs

- Does the expansion of space imply anything about the dimensionality of the Universe?

- Unreachable statement wen upgrading APEX class version

- Discrete cops and robbers

- Is “overaction” an Indian English word?

- Stargate "instructional" videos

- Non-linear recurrence for rational sequences with generating function with radicals?

- MOSFETs keep shorting way below rated current

- Did the United States have consent from Texas to cede a piece of land that was part of Texas?

- What majority age is taken into consideration when travelling from country to country?

- Are all simple groups of order coprime to 3 cyclic? If so, why?

- Is a *magnetized* ferrite less ideal as a core?

- Is there a law against biohacking your pet?

- Whats the purpose of slots in wings?

- Garage door not closing when sunlight is bright

- Do temperature variations make trains on Mars impractical?

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

StoryLearning

Learn A Language Through Stories

How to Write in Chinese – A Beginner’s Guide

You probably think learning how to write in Chinese is impossible.

And I get it.

I’m a native English speaker, and I know how complex Chinese characters seem.

But you’re about to learn that it's not impossible .

I’ve teamed up with Kyle Balmer from Sensible Chinese to show you how you can learn the basic building blocks of the Chinese written language, and build your Chinese vocabulary quickly.

First, you’ll learn the basics of how the Chinese written language is constructed. Then, you’ll get a step-by-step guide for how to write Chinese characters sensibly and systematically .

Wondering how it can be so easy?

Then let’s get into it.

Don't have time to read this now? Click here to download a free PDF of the article

By the way, if you want to learn Chinese fast and have fun, my top recommendation is Chinese Uncovered which teaches you through StoryLearning®.

With Chinese Uncovered you’ll use my unique StoryLearning® method to learn Chinese through story… not rules.

It’s as fun as it is effective.

If you’re ready to get started, click here for a 7-day FREE trial.

How To Write In Chinese

Chinese is a complex language with many dialects and varieties.

Before we dive into learning to write Chinese characters, let’s just take a second to be clear exactly what we’ll be talking about.

First, you’ll be learning about Mandarin Chinese , the “standard” dialect. There are 5 main groups of dialects and perhaps 200 individual dialects in China & Taiwan. Mandarin Chinese is the “standard” used in Beijing and spoken or understood, by 2/3 of the population.

Second, there are two types of Chinese characters: Traditional and Simplified . In this article, we’ll be talking about Simplified Chinese characters, which are used in the majority of Mainland China.

There is an ongoing politicised debate about the two kinds of characters, and those asking themselves: “Should I learn traditional or simplified Chinese characters?” can face a difficult choice.

- For more on difference between Simplified and Traditional characters read this article

- To learn more about “the debate” read this excellent Wikipedia article

- If you want to switch Simplified characters into Traditional, you might like the fantastic New Tong Wen Tang browser plugin

First Steps in Learning Chinese Characters

When learning a European language, you have certain reference points that give you a head start.

If you're learning French and see the word l'hotel , for example, you can take a pretty good guess what it means! You have a shared alphabet and shared word roots to fall back on.

In Chinese this is not the case.

When you're just starting out, every sound, character, and word seems new and unique. Learning to read Chinese characters can feel like learning a whole set of completely illogical, unconnected “squiggles”!

The most commonly-taught method for learning to read and write these “squiggles” is rote learning .

Just write them again and again and practise until they stick in your brain and your hand remembers how to write them! This is an outdated approach, much like reciting multiplication tables until they “stick”.

I learnt this way.

Most Chinese learners learnt this way.

It's painful…and sadly discourages a lot of learners.

However, there is a better way.

Even without any common reference points between Chinese and English, the secret is to use the basic building blocks of Chinese, and use those building blocks as reference points from which to grow your knowledge of written Chinese.

This article will:

- Outline the different levels of structure inherent in Chinese characters

- Show you how to build your own reference points from scratch

- Demonstrate how to build up gradually without feeling overwhelmed

The Structure Of Written Chinese

The basic structure of written Chinese is as follows:

I like to think of Chinese like Lego . .. it's very “square”!

The individual bricks are the components (a.k.a radicals ).

We start to snap these components together to get something larger – the characters.

We can then snap characters together in order to make Chinese words.

Here's the really cool part about Chinese: Each of these pieces, at every level, has meaning.

The component, the character, the word… they all have meaning.

This is different to a European language, where the “pieces” used to make up words are letters.

Letters by themselves don't normally have meaning and when we start to clip letters together we are shaping a sound rather than connecting little pieces of meaning. This is a powerful difference that comes into play later when we are learning vocabulary.

Let's look at the diagram again.

Here we start with the component 子. This has the meaning of “child/infant”.

The character 好 (“good”) is the next level. Look on the right of the character and you'll see 子. We would say that 子 is a component of 好.

Now look at the full word 你好 (“Hello”). Notice that the 子 is still there.

- The character 好 is built of the components 女 and 子.

- The character 你 is built from 人 + 尔.

- The word 你好 in turn is constructed out of 你 + 好.

Here's the complete breakdown of that word in an easy-to-read diagram:

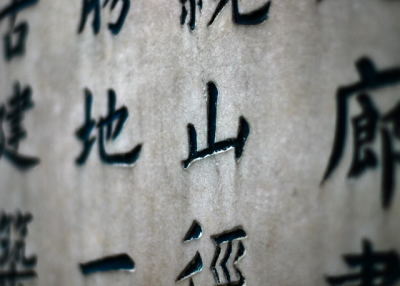

Now look at this photo of this in real life !

Don't worry if you can't understand it. Just look for some shapes that you have seen before.

The font is a little funky, so here are the typed characters: 好孩子

What components have you seen before?

Did you spot them?

This is a big deal.

Here's why…

Why Character Components Are So Important

One of the big “scare stories” around Chinese is that there are 50,000 characters to learn.

Now, this is true. But learning them isn't half as bad as you think.

Firstly, only a few thousand characters are in general everyday use so that number is a lot more manageable.

Second, and more importantly, those 50,000 characters are all made up of the same 214 components .

And you already know one of them: 子 (it's one of those 214 components).

The fact that you can now recognise the 子 in the image above is a huge step forward.

You can already recognise one of the 214 pieces all characters are made up of.

Even better is the fact that of these 214 components it's only the 50-100 most common you'll be running into again and again.

This makes Chinese characters a lot less scary.

Once you get a handle on these basic components, you'll quickly recognise all the smaller pieces and your eyes will stop glazing over!

This doesn't mean you'll necessarily know the meaning or how to pronounce the words yet (we'll get onto this shortly) but suddenly Chinese doesn't seem quite so alien any more.

Memorising The Components Of Chinese Characters

Memorising the pieces is not as important as simply realising that ALL of Chinese is constructed from these 214 pieces.

When I realised this, Chinese became a lot more manageable and I hope I've saved you some heartache by revealing this early in your learning process!

Here are some useful online resources for learning the components of Chinese characters:

- An extensive article about the 214 components of Chinese characters with a free printable PDF poster.

- Downloadable posters of all the components, characters and words.

- If you like flashcards, there's a great Anki deck here and a Memrise course here .

- Wikipedia also has a sweet sortable list here .

TAKEAWAY : Every single Chinese character is composed of just 214 “pieces”. Only 50-100 of these are commonly used. Learn these pieces first to learn how to write in Chinese quickly.

Moving From Components To Chinese Characters

Once you've got a grasp of the basic building blocks of Chinese it's time to start building some characters!

We used the character 好 (“good”) in the above example. 好 is a character composed of the components 女 (“woman”) and 子 (“child”).

Unlike the letters of the alphabet in English, these components have meaning .

(They also have pronunciation, but for the sake of simplicity we'll leave that aside for now!)

- 女 means “woman” and 子 means “child”.

- When they are put together, 女 and 子 become 好 …and the meaning is “good”.

- Therefore “woman” + “child” = “good” in Chinese 🙂

When learning how to write in Chinese characters you can take advantage of the fact that components have their own meanings.

In this case, it is relatively easy to make a mnemonic (memory aid) that links the idea of a woman with her baby as “good”.

Because Chinese is so structured, these kind of mnemonics are an incredibly powerful tool for memorisation.

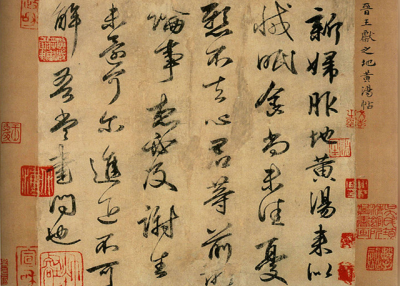

Some characters, including 好, can also be easily represented graphically. ShaoLan's book Chineasy does a fantastic job of this.

Here's the image of 好 for instance – you can see the mother and child.

Visual graphics like these can really help in learning Chinese characters.

Unfortunately, only around 5% of the characters in Chinese are directly “visual” in this way. These characters tend to get the most attention because they look great when illustrated.

However, as you move beyond the concrete in the more abstract it becomes harder and harder to visually represent ideas.

Thankfully, the ancient Chinese had an ingenious solution, a solution that actually makes the language a lot more logical and simple than merely adding endless visual pictures.

Watch Me Write Chinese Characters

In the video below, which is part of a series on learning to write in Chinese , I talk about the process of actually writing out the characters. Not thousands of times like Chinese schoolchildren. But just as a way to reinforce my learning and attack learning Chinese characters from different angles.

My Chinese handwriting leaves a lot to be desired. But it's more about a process of reinforcing my language learning via muscle memory than perfecting my handwriting.

You'll also hear me discuss some related issues such as stroke order and typing in Chinese.

The Pronunciation Of Chinese Characters

The solution was the incredibly unsexy sounding… (wait for it…) “phono-semantic compound character”.

It's an awful name, so I'm going to call them “sound-meaning characters” for now!

This concept is the key to unlocking 95% of the Chinese characters.

A sound-meaning character has a component that tells us two things:

- the meaning

- a clue to how the character is pronounced

So, in simple terms:

95% of Chinese characters have a clue to the meaning of the character AND its pronunciation.

到 means “to arrive”.

This character is made of two components. On the left is 至 and on the right is 刀.

These are two of the 214 components that make up all characters. 至 means “to arrive” and 刀 means “knife”.

Any idea which one gives us the meaning? Yup – it's 至, “to arrive”! (That was an easy one 🙂 )

But how about the 刀? This is where it gets interesting.

到 is pronounced dào.

刀, “knife” is pronounced dāo.

The reason the 刀 is placed next to 至 in the character 到 is just to tell us how to pronounce the character! How cool is that?

Now, did you notice the little lines above the words: dào and dāo?

Those are the tone markers, and in this case they are both slightly different. These two characters have different tones so they are not exactly the same pronunciation.

However, the sound-meaning compound has got us 90% of the way to being able to pronounce the character, all because some awesome ancient Chinese scribe thought there should be a shortcut to help us remember the pronunciation!

Let's look at a few more examples of how 刀 is used in different words to give you an idea of the pronunciation.

Even if sometimes:

- the sound-meaning character gives us the exact sound and meaning

- or it gets us in the ballpark

- or worse it is way off because the character has changed over the last 5,000 years!

Nevertheless, there's a clue about the pronunciation in 95% of all Chinese characters, which is a huge help for learning how to speak Chinese.

TAKEAWAY : Look at the component parts as a way to unlock the meaning and pronunciations of 95% of Chinese characters. In terms of “hacking” the language, this is the key to learning how to write in Chinese quickly.

From Chinese Characters To Chinese Words

First we went from components to characters.

Next, we are going from characters to words.

Although there are a lot of one-character words in Chinese, they tend to either be classically-rooted words like “king” and “horse” or grammatical particles and pronouns.

The vast majority of Chinese words contain two characters.

The step from characters to words is where, dare I say it, Chinese script gets easy!

Come on, you didn't think it would always be hard did you? 🙂

Unlike European languages Chinese's difficulty is very front-loaded.

When you first learn to write Chinese, you'll discover a foreign pronunciation system, a foreign tonal system and a very foreign writing system.

As an English speaker, you can normally have a good shot at pronouncing and reading words in other European languages, thanks to the shared alphabet.

Chinese, on the other hand, sucker-punches you on day one… but gets a little more gentle as you go along.

One you've realised these things:

- there aren't that many components to deal with

- all characters are made up of these basic components

- words are actually characters bolted together

…then it's a matter of just memorising a whole bunch of stuff!

That's not to say there isn't a lot of work involved, only to say that it's not particularly difficult. Time-consuming, yes. Difficult, no.

This is quite different from European languages, which start off easy, but quickly escalate in difficulty as you encounter complicated grammar, tenses, case endings, technical vocabulary and so on.

Making words from Chinese characters you already know is easy and really fun . This is where you get to start snapping the lego blocks together and build that Pirate Island!

The Logic Of Chinese Writing

Here are some wonderful examples of the simplicity and logic of Chinese using the character 车 which roughly translates as “vehicle”.

- Water + Vehicle = Waterwheel = 水 +车

- Wind + Vehicle = Windmill = 风+车

- Electric + Vehicle = Tram/Trolley = 电+车

- Fire + Vehicle = Train = 火+车

- Gas + Vehicle = Car = 汽+车

- Horse + Vehicle = Horse and cart/Trap and Pony = 马+车

- Up + Vehicle = Get into/onto a vehicle =上+车

- Down + Vehicle = Get out/off a vehicle =下+车

- Vehicle + Warehouse = Garage = 车+库

- To Stop + Vehicle = to park = 停+车

Chinese is extremely logical and consistent.

This is a set of building blocks that has evolved over 5,000 years in a relatively linear progression. And you can't exactly say the same about the English language!

Just think of the English words for the Chinese equivalences above:

Train, windmill, millwheel/waterwheel, tram/trolley, car/automobile, horse and cart/trap and pony.

Unlike Chinese where these concepts are all linked by 车 there's very little consistency in our vehicle/wheel related vocabulary, and no way to link these sets of related concepts via the word itself.

English is a diverse and rich language, but that comes with its drawbacks – a case-by-case spelling system that drives learners mad.

Chinese, on the other hand, is precise and logical, once you get over the initial “alienness”.

Making The Complex Simple

This logical way of constructing vocabulary is not limited to everyday words like “car” and “train”. It extends throughout the language.

To take an extreme example let's look at Jurassic Park .

The other day I watched Jurassic Park with my Chinese girlfriend. (OK, re -watched. It's a classic!)

Part of the fun for me (annoyance for her) was asking her the Chinese for various dinosaur species.

Take a second to look through these examples. You'll love the simplicity!

- T Rex 暴龙 = tyrant + dragon

- Tricerotops 三角恐龙 three + horn + dinosaur

- Diplodocus 梁龙 roof-beam + dragon

- Velociraptor 伶盗龙 clever + thief + dragon (or swift stealer dragon)

- Stegosaurus 剑龙 (double-edged) sword + dragon

- Dilophosaurus 双脊龙 double+spined+dragon

Don't try to memorise these characters, just appreciate the underlying logic of how the complex concepts are constructed .

(Unless, of course, you are a palaeontologist…or as the Chinese would say a Ancient + Life + Animal + Scientist!).

I couldn't spell half of these dinosaur names in English for this article. But once I knew how the construction of the Chinese word, typing in the right characters was simple.

Once you know a handful of characters, you can start to put together complete words, and knowing how to write in Chinese suddenly becomes a lot easier.

In a lot of cases you can take educated guesses at concepts and get them right by combining known characters into unknown words.

For more on this, check my series of Chinese character images that I publish on this page . They focus on Chinese words constructed from common characters, and help you understand more of the “building block” logic of Chinese.

TAKEAWAY : Chinese words are constructed extremely logically from the underlying characters. This means that once you've learned a handful of characters vocabulary acquisition speeds up exponentially.

How To Learn Written Chinese Fast

Before diving into learning characters, make sure you have a decent grounding in Chinese pronunciation via the pinyin system.

The reason for this is that taking on pronunciation, tones and characters from day one is really tough.

Don't get me wrong, you can do it. Especially if you're highly motivated. But for most people there's a better way.

Learn a bit of spoken Chinese first.

With some spoken language under your belt, and an understanding of pronunciation and tones, starting to learn how to write in Chinese will seem a whole lot easier.

When you're ready, here's how to use all the information from this article and deal with written Chinese in a sensible way.

I've got a systematic approach to written Chinese which you can find in detail on Sensible Chinese .

Right now, I'm going to get you started with the basics.

The Sensible Character System

The four stages for learning Chinese characters are:

Sounds technical huh? Don't worry, it's not really.

This part of the process is about choosing what you put into your character learning system.

If you're working on the wrong material then you're wasting your efforts. Instead choose to learn Chinese characters that you are like to want to use in the future.

My list in order of priority contains:

- daily life: characters/words I've encountered through daily life

- textbooks: characters/words I've learnt from textbooks

- frequency lists: characters/words I've found in frequency lists of the most common characters and words

2. Processing

This is the “learning” part of the system.

You take a new word or character and break it down into its component parts. You can then use these components to create memory aids.

Hanzicraft.com or Pleco's built-in character decomposition tool are fantastic for breaking down new characters. These will be helpful until you learn to recognise the character components by sight. These tools will also show you if there are sound-meaning component clues in the character.

Use the individual components of a character to build a “story” around the character. Personal, sexy and violent stories tend to stick in the mind best! 🙂 I also like to add colours into my stories to represent the tones (1st tone Green, 2nd tone Blue etc.)

After the “input” and the “process”… it's time to review it all!

The simplest review system is paper flashcards which you periodically use to refresh your memory.

A more efficient method can be found in software or apps that use a Spaced Repetition System, like Anki or Pleco .

An important point: Review is not learning .

It's tempting to rely on software like Anki to drill in the vocabulary through brute-force repetition. But don't skip the first two parts – processing the character and creating a mnemonic are key parts of the process.

It isn't enough to just learn and review your words… you also need to put them into use !

Thankfully, technology has made this easier than ever. Finding a language exchange partner or a lesson with a cost-effective teacher is super simple nowadays, so there's no excuse for not putting your new vocabulary into action!

The resources I personally use are:

- Spoken – iTalki

- Written – Lang-8

- Short form written – WeChat / HelloTalk

Importantly, whilst you are using your current vocabulary in these forms of communication, you'll be picking up new content all the time, which you can add back into your system.

The four steps above are a cycle that you will continue to rotate through – all the corrections and new words you receive during usage should become material to add to the system.

To recap, the four steps of systematically learning Chinese characters are:

By building these steps into your regular study schedule you can steadily work through the thousands of Chinese characters and words you'll need to achieve literacy.

This is a long-haul process! So having a basic system in place is very important for consistency.

You can find out a lot more about The Sensible Chinese Character Learning System and how to write in Chinese here .

Top Chinese Learning Links And Resources

- Chinese Language Learning Resource List – a curated list of tools and content available online and in print to help your Chinese learning, all categorised by usage type.

- Sensible Character Learning System – the full system outlined in a series of blog articles for those who want more detail and tips on how to refine their character learning.

- 111 Mandarin Chinese resources you wish you knew – Olly’s huge list of the best resources on the web for learning Chinese

I hope you enjoyed this epic guide to learning how to write in Chinese!

Please share this post with any friends who are learning Chinese, then leave us a comment below!

Language Courses

- Language Blog

- Testimonials

- Meet Our Team

- Media & Press

Steal My Method?

I’ve written some simple emails explaining the techniques I’ve used to learn 8 languages…

Which language are you learning?

What is your current level in

Where shall I send them?

We will protect your data in accordance with our data policy.

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective tips…

Download Your Free StoryLearning® Kit!

Discover the world famous story-based method that 1,023,037 people have used to learn a language quickly…

What is your current level in

WAIT! Don't skip this next step…

Welcome aboard!

You're about to discover the StoryLearning secrets thousands of my students have used to master Arabic!

But first, we need to make sure my emails arrive safely!

It will take less than 30 seconds. Here's what you need to do:

1) Go to your inbox & look for the email I just sent (Gmail users click here)

2) Mark the email as “important” & add me to your contact list

3) Send me a quick reply and say hi!

I'll see you on the other side

4) Start learning Spanish through story now with a FREE 7-day trial of Spanish Uncovered

What is your current level in [language]?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] [language] tips…

Where shall I send them?

Download this article as a FREE PDF ?

What is your current level in Latin?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Latin tips…

Where shall I send the tips and your PDF?

What is your current level in Norwegian?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Norwegian tips…

What is your current level in Swedish?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Swedish tips…

What is your current level in Danish?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Danish tips…

NOT INTERESTED?

What can we do better? If I could make something to help you right now, w hat would it be?

What is your current level in [language] ?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] [language] tips, PLUS your free StoryLearning Kit…

Download this article as a FREE PDF?

Great! Where shall I send my best online teaching tips and your PDF?

Download this article as a FREE PDF ?

What is your current level in Arabic?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Arabic tips…

FREE StoryLearning Kit!

Join my email newsletter and get FREE access to your StoryLearning Kit — discover how to learn languages through the power of story!

Download a FREE Story in Japanese!

Enter your email address below to get a FREE short story in Japanese and start learning Japanese quickly and naturally with my StoryLearning® method!

What is your current level in Japanese?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Japanese StoryLearning® Pack …

Where shall I send your download link?

Download Your FREE Natural Japanese Grammar Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Natural Japanese Grammar Pack and learn to internalise Japanese grammar quickly and naturally through stories.

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Natural Japanese Grammar Pack …

What is your current level in Portuguese?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Natural Portuguese Grammar Pack …

What is your current level in German?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Natural German Grammar Pack …

Train as an Online Language Teacher and Earn from Home

The next cohort of my Certificate of Online Language Teaching will open soon. Join the waiting list, and we’ll notify you as soon as enrolment is open!

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Portuguese tips…

What is your current level in Turkish?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Turkish tips…

What is your current level in French?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the French Vocab Power Pack …

What is your current level in Italian?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Italian Vocab Power Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the German Vocab Power Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Japanese Vocab Power Pack …

Download Your FREE Japanese Vocab Power Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Japanese Vocab Power Pack and learn essential Japanese words and phrases quickly and naturally. (ALL levels!)

Download Your FREE German Vocab Power Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my German Vocab Power Pack and learn essential German words and phrases quickly and naturally. (ALL levels!)

Download Your FREE Italian Vocab Power Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Italian Vocab Power Pack and learn essential Italian words and phrases quickly and naturally. (ALL levels!)

Download Your FREE French Vocab Power Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my French Vocab Power Pack and learn essential French words and phrases quickly and naturally. (ALL levels!)

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Portuguese StoryLearning® Pack …

What is your current level in Russian?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Natural Russian Grammar Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Russian StoryLearning® Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Italian StoryLearning® Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Natural Italian Grammar Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the French StoryLearning® Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Natural French Grammar Pack …

What is your current level in Spanish?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Spanish Vocab Power Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Natural Spanish Grammar Pack …

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the Spanish StoryLearning® Pack …

Where shall I send them?

What is your current level in Korean?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Korean tips…

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Russian tips…

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Japanese tips…

What is your current level in Chinese?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Chinese tips…

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Spanish tips…

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Italian tips…

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] French tips…

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] German tips…

Download Your FREE Natural Portuguese Grammar Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Natural Portuguese Grammar Pack and learn to internalise Portuguese grammar quickly and naturally through stories.

Download Your FREE Natural Russian Grammar Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Natural Russian Grammar Pack and learn to internalise Russian grammar quickly and naturally through stories.

Download Your FREE Natural German Grammar Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Natural German Grammar Pack and learn to internalise German grammar quickly and naturally through stories.

Download Your FREE Natural French Grammar Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Natural French Grammar Pack and learn to internalise French grammar quickly and naturally through stories.

Download Your FREE Natural Italian Grammar Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Natural Italian Grammar Pack and learn to internalise Italian grammar quickly and naturally through stories.

Download a FREE Story in Portuguese!

Enter your email address below to get a FREE short story in Brazilian Portuguese and start learning Portuguese quickly and naturally with my StoryLearning® method!

Download a FREE Story in Russian!

Enter your email address below to get a FREE short story in Russian and start learning Russian quickly and naturally with my StoryLearning® method!

Download a FREE Story in German!

Enter your email address below to get a FREE short story in German and start learning German quickly and naturally with my StoryLearning® method!

Perfect! You’ve now got access to the German StoryLearning® Pack …

Download a FREE Story in Italian!

Enter your email address below to get a FREE short story in Italian and start learning Italian quickly and naturally with my StoryLearning® method!

Download a FREE Story in French!

Enter your email address below to get a FREE short story in French and start learning French quickly and naturally with my StoryLearning® method!

Download a FREE Story in Spanish!

Enter your email address below to get a FREE short story in Spanish and start learning Spanish quickly and naturally with my StoryLearning® method!

FREE Download:

The rules of language learning.

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Rules of Language Learning and discover 25 “rules” to learn a new language quickly and naturally through stories.

What can we do better ? If I could make something to help you right now, w hat would it be?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] [language] tips…

Download Your FREE Spanish Vocab Power Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Spanish Vocab Power Pack and learn essential Spanish words and phrases quickly and naturally. (ALL levels!)

Download Your FREE Natural Spanish Grammar Pack

Enter your email address below to get free access to my Natural Spanish Grammar Pack and learn to internalise Spanish grammar quickly and naturally through stories.

Free Step-By-Step Guide:

How to generate a full-time income from home with your English… even with ZERO previous teaching experience.

What is your current level in Thai?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Thai tips…

What is your current level in Cantonese?

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] Cantonese tips…

I want to be skipped!

I’m the lead capture, man!

Join 84,574 other language learners getting StoryLearning tips by email…

“After I started to use your ideas, I learn better, for longer, with more passion. Thanks for the life-change!” – Dallas Nesbit

Perfect! You’ve now got access to my most effective [level] [language] tips…

Find The Perfect Language Course For You!

Looking for world-class training material to help you make a breakthrough in your language learning?

Click ‘start now’ and complete this short survey to find the perfect course for you!

Do you like the idea of learning through story?

Do you want…?

OPEN CLASSES

💻 Learn Chinese Online

Private Online Classes

Small-Group Online Classes

Private HSK Preparation

- Online Course for Corporate Clients

🎓 Learn Chinese in Beijing

Group Intensive

Group Part-Time

Group Part-Time HSK

Group Corporate Classes

Cultural Events & Trips

🎓 Learn Chinese in Shanghai

Summer Immersion

- Chinese Visa Program

Private Intensive

Private Small Group

Private Corporate Classes

- Accommodation in Shanghai

- Homestay in Shanghai

- CEIBS MBA Program

Group Intensive HSK

Visa Program

- Group Course for Corporate Clients

- 1-on-1 Private Course for Corporate Clients

🎓 Learn Chinese in Chengdu

Group Part-time

Private Classes

Private classes

🎓Learn Chinese in Beijing

Private Classes for Kids

Chinese Winter Camp

China School Trip

- Accommodation in Beijing

Parents’ Guide

Educators’ Guide

- Homestay in Beijing

Chinese Summer Camp in Shanghai

Chinese Winter Camp in Shanghai

🎓 Learn Chinese in Suzhou

PRIVATE COURSES

Online Private Classes for Kids

FOR PARENTS

FOR EDUCATORS

- Open Classes

- Learning Methodology

- Level System

- Upcoming Events

- Our Partners

- Students’ Reviews

- Intensive Group Course

- Part-time Small Group Course

- Intensive Group HSK Preparation Course

- Part-time Group HSK Preparation Course

- 1-on-1 Private Course

- Intensive 1-on-1 Private Course

- Private 1-on-2,3,4 Classes

- 1-on-1 Private HSK Preparation Course

- Summer Immersion Program

- Beijing Campus

- Cultural Events & Trips

- Intensive Group Programs

- Part-time Group Programs

- 1-on-1 Private Programs

- HSK Programs

- Summer Chinese Programs

- Chinese Visa Programs

- Accommodation

- Shanghai Campus

- Hangzhou Campus

- Chengdu Campus

- Suzhou Campus

- Part-Time Group Course

- Milan Campus

- Melbourne Campus

- 1-on-1 Private Online Course