Study vs. Research — What's the Difference?

Difference Between Study and Research

Table of contents, key differences, comparison chart, methodology, compare with definitions, common curiosities, what is the main difference between study and research, is study less rigorous than research, can you research without studying, what's the goal of research, is research always scientific, can you study and research at the same time, what's the goal of study, is study always academic, who typically conducts research, can you study by yourself, who typically studies, is research always formal, do research findings affect general populations, is research always published, can study be informal, share your discovery.

Author Spotlight

Popular Comparisons

Trending Comparisons

New Comparisons

Trending Terms

- Richard G. Trefry Library

Q. What's the difference between a research article (or research study) and a review article?

- Course-Specific

- Textbooks & Course Materials

- Tutoring & Classroom Help

- Writing & Citing

- 44 Articles & Journals

- 5 Artificial Intelligence

- 11 Capstone/Thesis/Dissertation Research

- 37 Databases

- 56 Information Literacy

- 9 Interlibrary Loan

- 9 Need help getting started?

- 22 Technical Help

Answered By: Priscilla Coulter Last Updated: Jul 26, 2024 Views: 234445

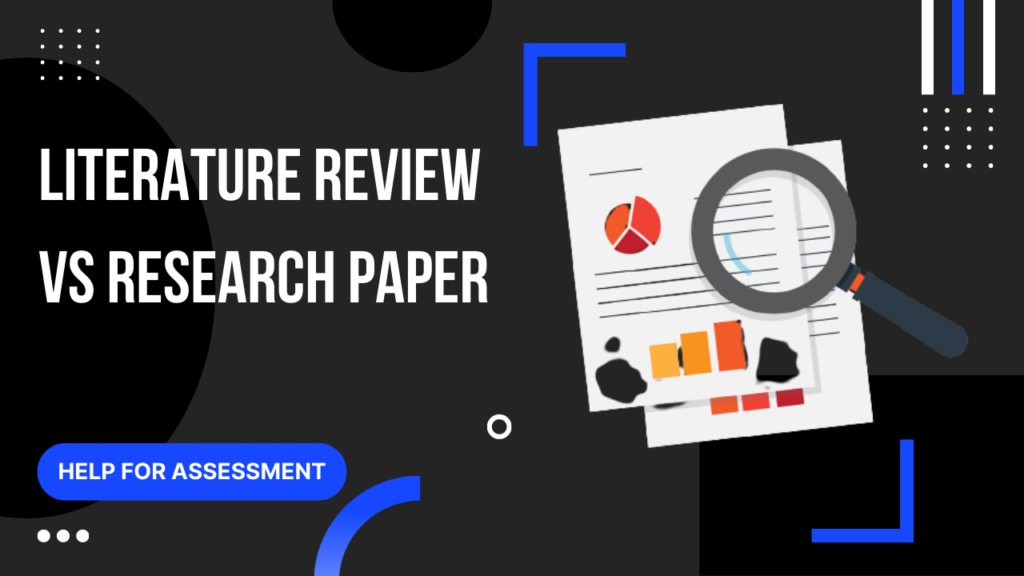

A research paper is a primary source ...that is, it reports the methods and results of an original study performed by the authors . The kind of study may vary (it could have been an experiment, survey, interview, etc.), but in all cases, raw data have been collected and analyzed by the authors , and conclusions drawn from the results of that analysis.

Research papers follow a particular format. Look for:

- A brief introduction will often include a review of the existing literature on the topic studied, and explain the rationale of the author's study. This is important because it demonstrates that the authors are aware of existing studies, and are planning to contribute to this existing body of research in a meaningful way (that is, they're not just doing what others have already done).

- A methods section, where authors describe how they collected and analyzed data. Statistical analyses are included. This section is quite detailed, as it's important that other researchers be able to verify and/or replicate these methods.

- A results section describes the outcomes of the data analysis. Charts and graphs illustrating the results are typically included.

- In the discussion , authors will explain their interpretation of their results and theorize on their importance to existing and future research.

- References or works cited are always included. These are the articles and books that the authors drew upon to plan their study and to support their discussion.

You can use the library's databases to search for research articles:

- A research article will nearly always be published in a peer-reviewed journal; click here for instructions on limiting your searches to peer-reviewed articles .

- If you have a particular type of study in mind, you can include keywords to describe it in your search . For instance, if you would like to see studies that used surveys to collect data, you can add "survey" to your topic in the database's search box. See this example search in our EBSCO databases: " bullying and survey ".

- Several of our databases have special limiting options that allow you to select specific methodologies. See, for instance, the " Methodology " box in ProQuest's PsycARTICLES Advanced Search (scroll down a bit to see it). It includes options like "Empirical Study" and "Qualitative Study", among many others.

A review article is a secondary source ...it is written about other articles, and does not report original research of its own. Review articles are very important, as they draw upon the articles that they review to suggest new research directions, to strengthen support for existing theories and/or identify patterns among exising research studies. For student researchers, review articles provide a great overview of the existing literature on a topic. If you find a literature review that fits your topic, take a look at its references/works cited list for leads on other relevant articles and books!

You can use the library's article databases to find literature reviews as well! Click here for tips.

- Share on Facebook

Was this helpful? Yes 8 No 1

Related Topics

- Articles & Journals

- Information Literacy

Need personalized help? Librarians are available 365 days/nights per year! See our schedule.

Learn more about how librarians can help you succeed.

Reference management. Clean and simple.

Types of research papers

Analytical research paper

Argumentative or persuasive paper, definition paper, compare and contrast paper, cause and effect paper, interpretative paper, experimental research paper, survey research paper, frequently asked questions about the different types of research papers, related articles.

There are multiple different types of research papers. It is important to know which type of research paper is required for your assignment, as each type of research paper requires different preparation. Below is a list of the most common types of research papers.

➡️ Read more: What is a research paper?

In an analytical research paper you:

- pose a question

- collect relevant data from other researchers

- analyze their different viewpoints

You focus on the findings and conclusions of other researchers and then make a personal conclusion about the topic. It is important to stay neutral and not show your own negative or positive position on the matter.

The argumentative paper presents two sides of a controversial issue in one paper. It is aimed at getting the reader on the side of your point of view.

You should include and cite findings and arguments of different researchers on both sides of the issue, but then favor one side over the other and try to persuade the reader of your side. Your arguments should not be too emotional though, they still need to be supported with logical facts and statistical data.

Tip: Avoid expressing too much emotion in a persuasive paper.

The definition paper solely describes facts or objective arguments without using any personal emotion or opinion of the author. Its only purpose is to provide information. You should include facts from a variety of sources, but leave those facts unanalyzed.

Compare and contrast papers are used to analyze the difference between two:

Make sure to sufficiently describe both sides in the paper, and then move on to comparing and contrasting both thesis and supporting one.

Cause and effect papers are usually the first types of research papers that high school and college students write. They trace probable or expected results from a specific action and answer the main questions "Why?" and "What?", which reflect effects and causes.

In business and education fields, cause and effect papers will help trace a range of results that could arise from a particular action or situation.

An interpretative paper requires you to use knowledge that you have gained from a particular case study, for example a legal situation in law studies. You need to write the paper based on an established theoretical framework and use valid supporting data to back up your statement and conclusion.

This type of research paper basically describes a particular experiment in detail. It is common in fields like:

Experiments are aimed to explain a certain outcome or phenomenon with certain actions. You need to describe your experiment with supporting data and then analyze it sufficiently.

This research paper demands the conduction of a survey that includes asking questions to respondents. The conductor of the survey then collects all the information from the survey and analyzes it to present it in the research paper.

➡️ Ready to start your research paper? Take a look at our guide on how to start a research paper .

In an analytical research paper, you pose a question and then collect relevant data from other researchers to analyze their different viewpoints. You focus on the findings and conclusions of other researchers and then make a personal conclusion about the topic.

The definition paper solely describes facts or objective arguments without using any personal emotion or opinion of the author. Its only purpose is to provide information.

Cause and effect papers are usually the first types of research papers that high school and college students are confronted with. The answer questions like "Why?" and "What?", which reflect effects and causes. In business and education fields, cause and effect papers will help trace a range of results that could arise from a particular action or situation.

This type of research paper describes a particular experiment in detail. It is common in fields like biology, chemistry or physics. Experiments are aimed to explain a certain outcome or phenomenon with certain actions.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Paper

Definition:

Research Paper is a written document that presents the author’s original research, analysis, and interpretation of a specific topic or issue.

It is typically based on Empirical Evidence, and may involve qualitative or quantitative research methods, or a combination of both. The purpose of a research paper is to contribute new knowledge or insights to a particular field of study, and to demonstrate the author’s understanding of the existing literature and theories related to the topic.

Structure of Research Paper

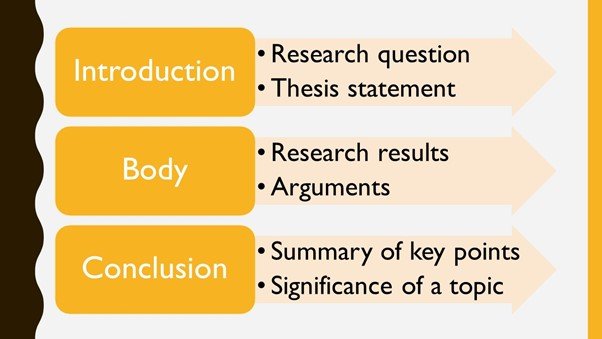

The structure of a research paper typically follows a standard format, consisting of several sections that convey specific information about the research study. The following is a detailed explanation of the structure of a research paper:

The title page contains the title of the paper, the name(s) of the author(s), and the affiliation(s) of the author(s). It also includes the date of submission and possibly, the name of the journal or conference where the paper is to be published.

The abstract is a brief summary of the research paper, typically ranging from 100 to 250 words. It should include the research question, the methods used, the key findings, and the implications of the results. The abstract should be written in a concise and clear manner to allow readers to quickly grasp the essence of the research.

Introduction

The introduction section of a research paper provides background information about the research problem, the research question, and the research objectives. It also outlines the significance of the research, the research gap that it aims to fill, and the approach taken to address the research question. Finally, the introduction section ends with a clear statement of the research hypothesis or research question.

Literature Review

The literature review section of a research paper provides an overview of the existing literature on the topic of study. It includes a critical analysis and synthesis of the literature, highlighting the key concepts, themes, and debates. The literature review should also demonstrate the research gap and how the current study seeks to address it.

The methods section of a research paper describes the research design, the sample selection, the data collection and analysis procedures, and the statistical methods used to analyze the data. This section should provide sufficient detail for other researchers to replicate the study.

The results section presents the findings of the research, using tables, graphs, and figures to illustrate the data. The findings should be presented in a clear and concise manner, with reference to the research question and hypothesis.

The discussion section of a research paper interprets the findings and discusses their implications for the research question, the literature review, and the field of study. It should also address the limitations of the study and suggest future research directions.

The conclusion section summarizes the main findings of the study, restates the research question and hypothesis, and provides a final reflection on the significance of the research.

The references section provides a list of all the sources cited in the paper, following a specific citation style such as APA, MLA or Chicago.

How to Write Research Paper

You can write Research Paper by the following guide:

- Choose a Topic: The first step is to select a topic that interests you and is relevant to your field of study. Brainstorm ideas and narrow down to a research question that is specific and researchable.

- Conduct a Literature Review: The literature review helps you identify the gap in the existing research and provides a basis for your research question. It also helps you to develop a theoretical framework and research hypothesis.

- Develop a Thesis Statement : The thesis statement is the main argument of your research paper. It should be clear, concise and specific to your research question.

- Plan your Research: Develop a research plan that outlines the methods, data sources, and data analysis procedures. This will help you to collect and analyze data effectively.

- Collect and Analyze Data: Collect data using various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments. Analyze data using statistical tools or other qualitative methods.

- Organize your Paper : Organize your paper into sections such as Introduction, Literature Review, Methods, Results, Discussion, and Conclusion. Ensure that each section is coherent and follows a logical flow.

- Write your Paper : Start by writing the introduction, followed by the literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. Ensure that your writing is clear, concise, and follows the required formatting and citation styles.

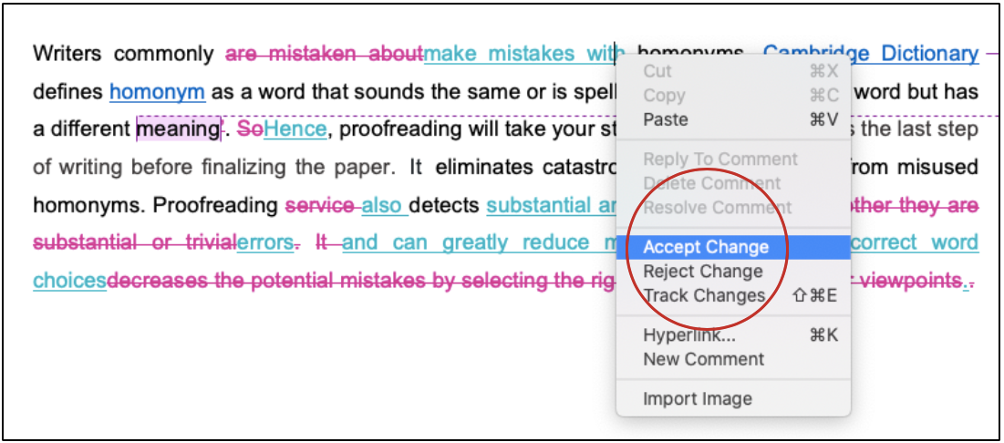

- Edit and Proofread your Paper: Review your paper for grammar and spelling errors, and ensure that it is well-structured and easy to read. Ask someone else to review your paper to get feedback and suggestions for improvement.

- Cite your Sources: Ensure that you properly cite all sources used in your research paper. This is essential for giving credit to the original authors and avoiding plagiarism.

Research Paper Example

Note : The below example research paper is for illustrative purposes only and is not an actual research paper. Actual research papers may have different structures, contents, and formats depending on the field of study, research question, data collection and analysis methods, and other factors. Students should always consult with their professors or supervisors for specific guidelines and expectations for their research papers.

Research Paper Example sample for Students:

Title: The Impact of Social Media on Mental Health among Young Adults

Abstract: This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults. A literature review was conducted to examine the existing research on the topic. A survey was then administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Introduction: Social media has become an integral part of modern life, particularly among young adults. While social media has many benefits, including increased communication and social connectivity, it has also been associated with negative outcomes, such as addiction, cyberbullying, and mental health problems. This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults.

Literature Review: The literature review highlights the existing research on the impact of social media use on mental health. The review shows that social media use is associated with depression, anxiety, stress, and other mental health problems. The review also identifies the factors that contribute to the negative impact of social media, including social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Methods : A survey was administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The survey included questions on social media use, mental health status (measured using the DASS-21), and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and regression analysis.

Results : The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Discussion : The study’s findings suggest that social media use has a negative impact on the mental health of young adults. The study highlights the need for interventions that address the factors contributing to the negative impact of social media, such as social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Conclusion : In conclusion, social media use has a significant impact on the mental health of young adults. The study’s findings underscore the need for interventions that promote healthy social media use and address the negative outcomes associated with social media use. Future research can explore the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health. Additionally, longitudinal studies can investigate the long-term effects of social media use on mental health.

Limitations : The study has some limitations, including the use of self-report measures and a cross-sectional design. The use of self-report measures may result in biased responses, and a cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causality.

Implications: The study’s findings have implications for mental health professionals, educators, and policymakers. Mental health professionals can use the findings to develop interventions that address the negative impact of social media use on mental health. Educators can incorporate social media literacy into their curriculum to promote healthy social media use among young adults. Policymakers can use the findings to develop policies that protect young adults from the negative outcomes associated with social media use.

References :

- Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2019). Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Preventive medicine reports, 15, 100918.

- Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Barrett, E. L., Sidani, J. E., Colditz, J. B., … & James, A. E. (2017). Use of multiple social media platforms and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A nationally-representative study among US young adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 1-9.

- Van der Meer, T. G., & Verhoeven, J. W. (2017). Social media and its impact on academic performance of students. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 16, 383-398.

Appendix : The survey used in this study is provided below.

Social Media and Mental Health Survey

- How often do you use social media per day?

- Less than 30 minutes

- 30 minutes to 1 hour

- 1 to 2 hours

- 2 to 4 hours

- More than 4 hours

- Which social media platforms do you use?

- Others (Please specify)

- How often do you experience the following on social media?

- Social comparison (comparing yourself to others)

- Cyberbullying

- Fear of Missing Out (FOMO)

- Have you ever experienced any of the following mental health problems in the past month?

- Do you think social media use has a positive or negative impact on your mental health?

- Very positive

- Somewhat positive

- Somewhat negative

- Very negative

- In your opinion, which factors contribute to the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Social comparison

- In your opinion, what interventions could be effective in reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Education on healthy social media use

- Counseling for mental health problems caused by social media

- Social media detox programs

- Regulation of social media use

Thank you for your participation!

Applications of Research Paper

Research papers have several applications in various fields, including:

- Advancing knowledge: Research papers contribute to the advancement of knowledge by generating new insights, theories, and findings that can inform future research and practice. They help to answer important questions, clarify existing knowledge, and identify areas that require further investigation.

- Informing policy: Research papers can inform policy decisions by providing evidence-based recommendations for policymakers. They can help to identify gaps in current policies, evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, and inform the development of new policies and regulations.

- Improving practice: Research papers can improve practice by providing evidence-based guidance for professionals in various fields, including medicine, education, business, and psychology. They can inform the development of best practices, guidelines, and standards of care that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- Educating students : Research papers are often used as teaching tools in universities and colleges to educate students about research methods, data analysis, and academic writing. They help students to develop critical thinking skills, research skills, and communication skills that are essential for success in many careers.

- Fostering collaboration: Research papers can foster collaboration among researchers, practitioners, and policymakers by providing a platform for sharing knowledge and ideas. They can facilitate interdisciplinary collaborations and partnerships that can lead to innovative solutions to complex problems.

When to Write Research Paper

Research papers are typically written when a person has completed a research project or when they have conducted a study and have obtained data or findings that they want to share with the academic or professional community. Research papers are usually written in academic settings, such as universities, but they can also be written in professional settings, such as research organizations, government agencies, or private companies.

Here are some common situations where a person might need to write a research paper:

- For academic purposes: Students in universities and colleges are often required to write research papers as part of their coursework, particularly in the social sciences, natural sciences, and humanities. Writing research papers helps students to develop research skills, critical thinking skills, and academic writing skills.

- For publication: Researchers often write research papers to publish their findings in academic journals or to present their work at academic conferences. Publishing research papers is an important way to disseminate research findings to the academic community and to establish oneself as an expert in a particular field.

- To inform policy or practice : Researchers may write research papers to inform policy decisions or to improve practice in various fields. Research findings can be used to inform the development of policies, guidelines, and best practices that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- To share new insights or ideas: Researchers may write research papers to share new insights or ideas with the academic or professional community. They may present new theories, propose new research methods, or challenge existing paradigms in their field.

Purpose of Research Paper

The purpose of a research paper is to present the results of a study or investigation in a clear, concise, and structured manner. Research papers are written to communicate new knowledge, ideas, or findings to a specific audience, such as researchers, scholars, practitioners, or policymakers. The primary purposes of a research paper are:

- To contribute to the body of knowledge : Research papers aim to add new knowledge or insights to a particular field or discipline. They do this by reporting the results of empirical studies, reviewing and synthesizing existing literature, proposing new theories, or providing new perspectives on a topic.

- To inform or persuade: Research papers are written to inform or persuade the reader about a particular issue, topic, or phenomenon. They present evidence and arguments to support their claims and seek to persuade the reader of the validity of their findings or recommendations.

- To advance the field: Research papers seek to advance the field or discipline by identifying gaps in knowledge, proposing new research questions or approaches, or challenging existing assumptions or paradigms. They aim to contribute to ongoing debates and discussions within a field and to stimulate further research and inquiry.

- To demonstrate research skills: Research papers demonstrate the author’s research skills, including their ability to design and conduct a study, collect and analyze data, and interpret and communicate findings. They also demonstrate the author’s ability to critically evaluate existing literature, synthesize information from multiple sources, and write in a clear and structured manner.

Characteristics of Research Paper

Research papers have several characteristics that distinguish them from other forms of academic or professional writing. Here are some common characteristics of research papers:

- Evidence-based: Research papers are based on empirical evidence, which is collected through rigorous research methods such as experiments, surveys, observations, or interviews. They rely on objective data and facts to support their claims and conclusions.

- Structured and organized: Research papers have a clear and logical structure, with sections such as introduction, literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. They are organized in a way that helps the reader to follow the argument and understand the findings.

- Formal and objective: Research papers are written in a formal and objective tone, with an emphasis on clarity, precision, and accuracy. They avoid subjective language or personal opinions and instead rely on objective data and analysis to support their arguments.

- Citations and references: Research papers include citations and references to acknowledge the sources of information and ideas used in the paper. They use a specific citation style, such as APA, MLA, or Chicago, to ensure consistency and accuracy.

- Peer-reviewed: Research papers are often peer-reviewed, which means they are evaluated by other experts in the field before they are published. Peer-review ensures that the research is of high quality, meets ethical standards, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

- Objective and unbiased: Research papers strive to be objective and unbiased in their presentation of the findings. They avoid personal biases or preconceptions and instead rely on the data and analysis to draw conclusions.

Advantages of Research Paper

Research papers have many advantages, both for the individual researcher and for the broader academic and professional community. Here are some advantages of research papers:

- Contribution to knowledge: Research papers contribute to the body of knowledge in a particular field or discipline. They add new information, insights, and perspectives to existing literature and help advance the understanding of a particular phenomenon or issue.

- Opportunity for intellectual growth: Research papers provide an opportunity for intellectual growth for the researcher. They require critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity, which can help develop the researcher’s skills and knowledge.

- Career advancement: Research papers can help advance the researcher’s career by demonstrating their expertise and contributions to the field. They can also lead to new research opportunities, collaborations, and funding.

- Academic recognition: Research papers can lead to academic recognition in the form of awards, grants, or invitations to speak at conferences or events. They can also contribute to the researcher’s reputation and standing in the field.

- Impact on policy and practice: Research papers can have a significant impact on policy and practice. They can inform policy decisions, guide practice, and lead to changes in laws, regulations, or procedures.

- Advancement of society: Research papers can contribute to the advancement of society by addressing important issues, identifying solutions to problems, and promoting social justice and equality.

Limitations of Research Paper

Research papers also have some limitations that should be considered when interpreting their findings or implications. Here are some common limitations of research papers:

- Limited generalizability: Research findings may not be generalizable to other populations, settings, or contexts. Studies often use specific samples or conditions that may not reflect the broader population or real-world situations.

- Potential for bias : Research papers may be biased due to factors such as sample selection, measurement errors, or researcher biases. It is important to evaluate the quality of the research design and methods used to ensure that the findings are valid and reliable.

- Ethical concerns: Research papers may raise ethical concerns, such as the use of vulnerable populations or invasive procedures. Researchers must adhere to ethical guidelines and obtain informed consent from participants to ensure that the research is conducted in a responsible and respectful manner.

- Limitations of methodology: Research papers may be limited by the methodology used to collect and analyze data. For example, certain research methods may not capture the complexity or nuance of a particular phenomenon, or may not be appropriate for certain research questions.

- Publication bias: Research papers may be subject to publication bias, where positive or significant findings are more likely to be published than negative or non-significant findings. This can skew the overall findings of a particular area of research.

- Time and resource constraints: Research papers may be limited by time and resource constraints, which can affect the quality and scope of the research. Researchers may not have access to certain data or resources, or may be unable to conduct long-term studies due to practical limitations.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Significance of the Study – Examples and Writing...

What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and...

How to Publish a Research Paper – Step by Step...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Report – Example, Writing Guide and...

Scope of the Research – Writing Guide and...

Maxwell Library | Bridgewater State University

Today's Hours:

- Maxwell Library

- Scholarly Journals and Popular Magazines

- Differences in Research, Review, and Opinion Articles

Scholarly Journals and Popular Magazines: Differences in Research, Review, and Opinion Articles

- Where Do I Start?

- How Do I Find Peer-Reviewed Articles?

- How Do I Compare Periodical Types?

- Where Can I find More Information?

Research Articles, Reviews, and Opinion Pieces

Scholarly or research articles are written for experts in their fields. They are often peer-reviewed or reviewed by other experts in the field prior to publication. They often have terminology or jargon that is field specific. They are generally lengthy articles. Social science and science scholarly articles have similar structures as do arts and humanities scholarly articles. Not all items in a scholarly journal are peer reviewed. For example, an editorial opinion items can be published in a scholarly journal but the article itself is not scholarly. Scholarly journals may include book reviews or other content that have not been peer reviewed.

Empirical Study: (Original or Primary) based on observation, experimentation, or study. Clinical trials, clinical case studies, and most meta-analyses are empirical studies.

Review Article: (Secondary Sources) Article that summarizes the research in a particular subject, area, or topic. They often include a summary, an literature reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses.

Clinical case study (Primary or Original sources): These articles provide real cases from medical or clinical practice. They often include symptoms and diagnosis.

Clinical trials ( Health Research): Th ese articles are often based on large groups of people. They often include methods and control studies. They tend to be lengthy articles.

Opinion Piece: An opinion piece often includes personal thoughts, beliefs, or feelings or a judgement or conclusion based on facts. The goal may be to persuade or influence the reader that their position on this topic is the best.

Book review: Recent review of books in the field. They may be several pages but tend to be fairly short.

Social Science and Science Research Articles

The majority of social science and physical science articles include

- Journal Title and Author

- Abstract

- Introduction with a hypothesis or thesis

- Literature Review

- Methods/Methodology

- Results/Findings

Arts and Humanities Research Articles

In the Arts and Humanities, scholarly articles tend to be less formatted than in the social sciences and sciences. In the humanities, scholars are not conducting the same kinds of research experiments, but they are still using evidence to draw logical conclusions. Common sections of these articles include:

- an Introduction

- Discussion/Conclusion

- works cited/References/Bibliography

Research versus Review Articles

- 6 Article types that journals publish: A guide for early career researchers

- INFOGRAPHIC: 5 Differences between a research paper and a review paper

- Michigan State University. Empirical vs Review Articles

- UC Merced Library. Empirical & Review Articles

- << Previous: Where Do I Start?

- Next: How Do I Find Peer-Reviewed Articles? >>

- Last Updated: Jan 24, 2024 10:48 AM

- URL: https://library.bridgew.edu/scholarly

Phone: 508.531.1392 Text: 508.425.4096 Email: [email protected]

Feedback/Comments

Privacy Policy

Website Accessibility

Follow us on Facebook Follow us on Twitter

Stack Exchange Network

Stack Exchange network consists of 183 Q&A communities including Stack Overflow , the largest, most trusted online community for developers to learn, share their knowledge, and build their careers.

Q&A for work

Connect and share knowledge within a single location that is structured and easy to search.

Difference between research paper and scientific paper

What is the difference between a research paper and a scientific paper? Does the research paper also mean a term paper at the end of your Masters?

I need to present a research paper. So does it mean I need to present a solution to an existing problem or does it mean a summary of various solutions already existing?

- terminology

2 Answers 2

A research paper is a paper containing original research. That is, if you do some work to add (or try to add) new knowledge to a field of study, and then present the details of your approach and findings in a paper, that paper can be called a research paper.

Not all academic papers contain original research; other kinds of academic papers that are not research papers are

- review papers, (see What is the difference between a review paper and a research paper? )

- position papers (which present an opinion without original research to support it)

- tutorial papers (which contain a tutorial introduction a topic or area, without contributing new results).

A scientific paper is any paper on a scientific subject.

Does the research paper also mean a term paper at the end of your Masters? I need to present a research paper. So does it mean I need to present a solution to an existing problem or does it mean a summary of various solutions already existing?

If the term paper at the end of your masters contains original research, then it's a research paper.

Depending on the policies of your department, you may or may not be required to attempt original research during your masters. In some departments, a review of existing literature may be fine. If you're not sure exactly what's required from you, you need to ask the relevant faculty or staff members in your department.

- Related: What is a "white paper"? . – E.P. Commented Jan 20, 2015 at 18:15

- It also bears mention that "a summary of various solutions already existing" does not usually qualify as a research paper. – E.P. Commented Jan 20, 2015 at 18:16

Research means that you add something new. Something you didn't know before, and ideally something no-one knew before (although at BSc. and MSc. levels the novelty requirement is generally relaxed). This can be a new investigation, or simply an analysis of a number existing papers. It must however not be a summary of existing solutions. It should go beyond that.

An important thing to remember is that in terms of assignment you are expected to demonstrate insight and understanding. To demonstrate this you need to engage with the topics, not merely summarise (which requires less understanding).

You must log in to answer this question.

Not the answer you're looking for browse other questions tagged terminology ..

- Featured on Meta

- User activation: Learnings and opportunities

- Join Stack Overflow’s CEO and me for the first Stack IRL Community Event in...

Hot Network Questions

- HTA w/ VBScript to open and copy links

- A thought experiment regarding elliptical orbits

- how does the US justice system combat rights violations that happen when bad practices are given a new name to avoid old rulings?

- Cartoon Network (Pakistan or India) show around 2007 or 2009 featuring a brother and sister who fight but later become allies

- Use the lower of two voltages when one is active

- How to get on to the roof?

- Can All Truths Be Scientifically Verified?

- On Concordant Readings in Titrations

- What can I do to limit damage to a ceiling below bathroom after faucet leak?

- Why does fdisk create a 512B partition when I enter +256K?

- How can I assign a heredoc to a variable in a way that's portable across Unix and Mac?

- Would a scientific theory of everything be falsifiable?

- How can I calculate derivative of eigenstates numerically?

- "00000000000000"

- Are these colored sets closed under multiplication?

- Grothendieck topoi as a constructive property

- Where is this citation in the Vana Parva of the Mahabharata?

- Class and macro with same name from different libraries

- What's the strongest material known to humanity that we could use to make Powered Armor Plates?

- Grid-based pathfinding for a lot of agents: how to implement "Tight-Following"?

- Count squares in my pi approximation

- What is an apologetic to confront Schellenberg's non-resistant divine hiddenness argument?

- Can I use a machine washing to clean neoprene wetsuits/socks/hoods/gloves if I use cold water, no spinning, no bleach and a gentle detergent?

- Are There U.S. Laws or Presidential Actions That Cannot Be Overturned by Successive Presidents?

Case Study vs. Research

What's the difference.

Case study and research are both methods used in academic and professional settings to gather information and gain insights. However, they differ in their approach and purpose. A case study is an in-depth analysis of a specific individual, group, or situation, aiming to understand the unique characteristics and dynamics involved. It often involves qualitative data collection methods such as interviews, observations, and document analysis. On the other hand, research is a systematic investigation conducted to generate new knowledge or validate existing theories. It typically involves a larger sample size and employs quantitative data collection methods such as surveys, experiments, or statistical analysis. While case studies provide detailed and context-specific information, research aims to generalize findings to a broader population.

| Attribute | Case Study | Research |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A detailed examination of a particular subject or situation over a period of time. | A systematic investigation to establish facts, principles, or to collect information on a subject. |

| Purpose | To gain in-depth understanding of a specific case or phenomenon. | To contribute to existing knowledge and generate new insights. |

| Scope | Usually focuses on a single case or a small number of cases. | Can cover a wide range of cases or subjects. |

| Data Collection | Relies on various sources such as interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts. | Uses methods like surveys, experiments, observations, and interviews to collect data. |

| Data Analysis | Often involves qualitative analysis, thematic coding, and pattern recognition. | Can involve both qualitative and quantitative analysis techniques. |

| Generalizability | Findings may not be easily generalized due to the specific nature of the case. | Strives for generalizability to larger populations or contexts. |

| Timeframe | Can be conducted over a relatively short or long period of time. | Can span from short-term studies to long-term longitudinal studies. |

| Application | Often used in fields such as social sciences, business, and psychology. | Applied in various disciplines including natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities. |

Further Detail

Introduction.

When it comes to conducting studies and gathering information, researchers have various methods at their disposal. Two commonly used approaches are case study and research. While both methods aim to explore and understand a particular subject, they differ in their approach, scope, and the type of data they collect. In this article, we will delve into the attributes of case study and research, highlighting their similarities and differences.

A case study is an in-depth analysis of a specific individual, group, event, or phenomenon. It involves a detailed examination of a particular case to gain insights into its unique characteristics, context, and dynamics. Case studies often employ multiple sources of data, such as interviews, observations, and documents, to provide a comprehensive understanding of the subject under investigation.

One of the key attributes of a case study is its focus on a specific case, which allows researchers to explore complex and nuanced aspects of the subject. By examining a single case in detail, researchers can uncover rich and detailed information that may not be possible with broader research methods. Case studies are particularly useful when studying rare or unique phenomena, as they provide an opportunity to deeply analyze and understand them.

Furthermore, case studies often employ qualitative research methods, emphasizing the collection of non-numerical data. This qualitative approach allows researchers to capture the subjective experiences, perspectives, and motivations of the individuals or groups involved in the case. By using open-ended interviews and observations, researchers can gather rich and detailed data that provides a holistic view of the subject.

However, it is important to note that case studies have limitations. Due to their focus on a specific case, the findings may not be easily generalized to a larger population or context. The small sample size and unique characteristics of the case may limit the generalizability of the results. Additionally, the subjective nature of qualitative data collection in case studies may introduce bias or interpretation challenges.

Research, on the other hand, is a systematic investigation aimed at discovering new knowledge or validating existing theories. It involves the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data to answer research questions or test hypotheses. Research can be conducted using various methods, including surveys, experiments, and statistical analysis, depending on the nature of the study.

One of the primary attributes of research is its emphasis on generating generalizable knowledge. By using representative samples and statistical techniques, researchers aim to draw conclusions that can be applied to a larger population or context. This allows for the identification of patterns, trends, and relationships that can inform theories, policies, or practices.

Research often employs quantitative methods, focusing on the collection of numerical data that can be analyzed using statistical techniques. Surveys, experiments, and statistical analysis allow researchers to measure variables, establish correlations, and test hypotheses. This objective approach provides a level of objectivity and replicability that is crucial for scientific inquiry.

However, research also has its limitations. The focus on generalizability may sometimes sacrifice the depth and richness of understanding that case studies offer. The reliance on quantitative data may overlook important qualitative aspects of the subject, such as individual experiences or contextual factors. Additionally, the controlled nature of research settings may not fully capture the complexity and dynamics of real-world situations.

Similarities

Despite their differences, case studies and research share some common attributes. Both methods aim to gather information and generate knowledge about a particular subject. They require careful planning, data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Both case studies and research contribute to the advancement of knowledge in their respective fields.

Furthermore, both case studies and research can be used in various disciplines, including social sciences, psychology, business, and healthcare. They provide valuable insights and contribute to evidence-based decision-making. Whether it is understanding the impact of a new treatment, exploring consumer behavior, or investigating social phenomena, both case studies and research play a crucial role in expanding our understanding of the world.

In conclusion, case study and research are two distinct yet valuable approaches to studying and understanding a subject. Case studies offer an in-depth analysis of a specific case, providing rich and detailed information that may not be possible with broader research methods. On the other hand, research aims to generate generalizable knowledge by using representative samples and quantitative methods. While case studies emphasize qualitative data collection, research focuses on quantitative analysis. Both methods have their strengths and limitations, and their choice depends on the research objectives, scope, and context. By utilizing the appropriate method, researchers can gain valuable insights and contribute to the advancement of knowledge in their respective fields.

Comparisons may contain inaccurate information about people, places, or facts. Please report any issues.

[email protected]

- English English Spanish German French Turkish

Thesis vs. Research Paper: Know the Differences

It is not uncommon for individuals, academic and nonacademic to use “thesis” and “research paper” interchangeably. However, while the thesis vs. research paper puzzle might seem amusing to some, for graduate, postgraduate and doctoral students, knowing the differences between the two is crucial. Not only does a clear demarcation of the two terms help you acquire a precise approach toward writing each of them, but it also helps you keep in mind the subtle nuances that go into creating the two documents. This brief guide discusses the main difference between a thesis and a research paper.

This article discusses the main difference between a thesis and a research paper. To give you an opportunity to practice proofreading, we have left a few spelling, punctuation, or grammatical errors in the text. See if you can spot them! If you spot the errors correctly, you will be entitled to a 10% discount.

It is not uncommon for individuals, academic and nonacademic to use “thesis” and “research paper” interchangeably. After all, both terms share the same domain, academic writing . Moreover, characteristics like the writing style, tone, and structure of a thesis and research paper are also homogenous to a certain degree. Hence, it is not surprising that many people mistake one for the other.

However, while the thesis vs. research paper puzzle might seem amusing to some, for graduate, postgraduate and doctoral students, knowing the differences between the two is crucial. Not only does a clear demarcation of the two terms help you acquire a precise approach toward writing each of them, but it also helps you keep in mind the subtle nuances that go into creating the two documents.

Defining the two terms: thesis vs. research paper

The first step to discerning between a thesis and research paper is to know what they signify.

Thesis: A thesis or a dissertation is an academic document that a candidate writes to acquire a university degree or similar qualification. Students typically submit a thesis at the end of their final academic term. It generally consists of putting forward an argument and backing it up with individual research and existing data.

How to Write a Perfect Ph.D. Thesis

How to Choose a Thesis or Dissertation Topic: 6 Tips

5 Common Mistakes When Writing a Thesis or Dissertation

How to Structure a Dissertation: A Brief Guide

A Step-by-Step Guide on Writing and Structuring Your Dissertation

Research Paper: A research paper is also an academic document, albeit shorter compared to a thesis. It consists of conducting independent and extensive research on a topic and compiling the data in a structured and comprehensible form. A research paper demonstrates a student's academic prowess in their field of study along with strong analytical skills.

7 Tips to Write an Effective Research Paper

7 Steps to Publishing in a Scientific Journal

Publishing Articles in Peer-Reviewed Journals: A Comprehensive Guide

10 Free Online Journal and Research Databases for Researchers

How to Formulate Research Questions

Now that we have a fundamental understanding of a thesis and a research paper, it is time to dig deeper. To the untrained eye, a research paper and a thesis might seem similar. However, there are some differences, concrete and subtle, that set the two apart.

1. Writing objectives

The objective behind writing a thesis is to obtain a master's degree or doctorate and the ilk. Hence, it needs to exemplify the scope of your knowledge in your study field. That is why choosing an intriguing thesis topic and putting forward your arguments convincingly in favor of it is crucial.

A research paper is written as a part of a course's curriculum or written for publication in a peer-review journal. Its purpose is to contribute something new to the knowledge base of its topic.

2. Structure

Although both documents share quite a few similarities in their structures, the framework of a thesis is more rigid. Also, almost every university has its proprietary guidelines set out for thesis writing.

Comparatively, a research paper only needs to keep the IMRAD format consistent throughout its length. When planning to publish your research paper in a peer-review journal, you also must follow your target journal guidelines.

3. Time Taken

A thesis is an extensive document encompassing the entire duration of a master's or doctoral course and as such, it takes months and even years to write.

A research paper, being less lengthy, typically takes a few weeks or a few months to complete.

4. Supervision

Writing a thesis entails working with a faculty supervisor to ensure that you are on the right track. However, a research paper is more of a solo project and rarely needs a dedicated supervisor to oversee.

5. Finalization

The final stage of thesis completion is a viva voce examination and a thesis defense. It includes proffering your thesis to the examination board or a thesis committee for a questionnaire and related discussions. Whether or not you will receive a degree depends on the result of this examination and the defense.

A research paper is said to be complete when you finalize a draft, check it for plagiarism, and proofread for any language and contextual errors . Now all that's left is to submit it to the assigned authority.

What is Plagiarism | How to Avoid It

How to Choose the Right Plagiarism Checker for Your Academic Works

5 Practical Ways to Avoid Plagiarism

10 Common Grammar Mistakes in Academic Writing

Guide to Avoid Common Mistakes in Sentence Structuring

In the context of academic writing, a thesis and a research paper might appear the same. But, there are some fundamental differences that set apart the two writing formats. However, since both the documents come under the scope of academic writing, they also share some similarities. Both require formal language, formal tone, factually correct information & proper citations. Also, editing and proofreading are a must for both. Editing and Proofreading ensure that your document is properly formatted and devoid of all grammatical & contextual errors. So, the next time when you come across a thesis vs. research paper argument, keep these differences in mind.

Editing or Proofreading? Which Service Should I Choose?

Thesis Proofreading and Editing Services

8 Benefits of Using Professional Proofreading and Editing Services

Achieve What You Want with Academic Editing and Proofreading

How Much Do Proofreading and Editing Cost?

If you need us to make your thesis or dissertation, contact us unhesitatingly!

Best Edit & Proof expert editors and proofreaders focus on offering papers with proper tone, content, and style of academic writing, and also provide an upscale editing and proofreading service for you. If you consider our pieces of advice, you will witness a notable increase in the chance for your research manuscript to be accepted by the publishers. We work together as an academic writing style guide by bestowing subject-area editing and proofreading around several categorized writing styles. With the group of our expert editors, you will always find us all set to help you identify the tone and style that your manuscript needs to get a nod from the publishers.

English formatting service

You can also avail of our assistance if you are looking for editors who can format your manuscript, or just check on the particular styles for the formatting task as per the guidelines provided to you, e.g., APA, MLA, or Chicago/Turabian styles. Best Edit & Proof editors and proofreaders provide all sorts of academic writing help, including editing and proofreading services, using our user-friendly website, and a streamlined ordering process.

Get a free quote for editing and proofreading now!

Visit our order page if you want our subject-area editors or language experts to work on your manuscript to improve its tone and style and give it a perfect academic tone and style through proper editing and proofreading. The process of submitting a paper is very easy and quick. Click here to find out how it works.

Our pricing is based on the type of service you avail of here, be it editing or proofreading. We charge on the basis of the word count of your manuscript that you submit for editing and proofreading and the turnaround time it takes to get it done. If you want to get an instant price quote for your project, copy and paste your document or enter your word count into our pricing calculator.

24/7 customer support | Live support

Contact us to get support with academic editing and proofreading. We have a 24/7 active live chat mode to offer you direct support along with qualified editors to refine and furbish your manuscript.

Stay tuned for updated information about editing and proofreading services!

Follow us on Twitter, LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram, and Medium .

For more posts, click here.

- Editing & Proofreading

- Citation Styles

- Grammar Rules

- Academic Writing

- Proofreading

- Microsoft Tools

- Academic Publishing

- Dissertation & Thesis

- Researching

- Job & Research Application

Similar Posts

How to Determine Variability in a Dataset

How to Determine Central Tendency

How to Specify Study Variables in Research Papers?

Population vs Sample | Sampling Methods for a Dissertation

7 Issues to Avoid That may Dent the Quality of Thesis Writing

How to Ensure the Quality of Academic Writing in a Thesis and Dissertation?

How to Define Population and Sample in a Dissertation?

Recent Posts

ANOVA vs MANOVA: Which Method to Use in Dissertations?

They Also Read

Writing assignments is not like any other homework you’ve ever done or will do in your academic life. Writing assignments demands unrestrained dedication and plenty of willpower. You cannot just open a book and copy-paste its contents with some rephrasing. To write a better assignment, you need to work hard, you need to research, plan, draft, and edit carefully. Writing an assignment paper is one thing and writing an impactful assignment paper that instills a positive impression of you in your professor’s books and elicits good grades out of him/her is another one. The following tips will help you write a perfect assignment paper.

As a college student in the USA, the UK, Canada, or anywhere else, you may have a wealth of opportunities for freelance work due to your connections. Freelancing can be an excellent way to create an income stream and expand your writing portfolio. Take early advantage of your education while you're still in school and start a freelancing career. This handout provides an easy guide for freelance opportunities for college students.

Maintaining parallel structure prevents writers from making grammatically incorrect sentences and helps them to improve their writing styles. Although lack of parallelism is not always strictly incorrect, sentences with the parallel structure are easier to read and add a sense of balance to your academic writing. In this article, we will focus on what is parallel structure and how to use parallel structure in academic writing.

Briefly, research objectives are all about what you intend to achieve in your project. Therefore, they are expected to list every stage of the research and cover which methods they have used to gather data, establish their focal point, and advance their conclusions.

When you deal with experiments, you investigate the causal relationship between variables. What you fundamentally do is manipulate one or more than one independent variable (x) to determine their effect on dependent variables (y).

International Journal of Research (IJR)

IJR Journal is Multidisciplinary, high impact and indexed journal for research publication. IJR is a monthly journal for research publication.

DIFFERENCE BETWEEN RESEARCH PAPER AND JOURNAL ARTICLE

Difference between research paper and journal article.

Research Paper

Argumentative Research Paper

Analytical research paper, journal article, the differences, research paper:, journal article:.

- Share on Tumblr

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- KCES's Institute of Management & Research, Jalgaon

What is the difference between Research Paper, Research Article, Review Paper & Review Article?

Most recent answer.

Popular answers (1)

Top contributors to discussions in this field

- National Polytechnic School of Algiers

- Shenzhen University

- Technical College Požarevac

- SEAMEO RECSAM

- Dav Institute of Engineering and Technology

Get help with your research

Join ResearchGate to ask questions, get input, and advance your work.

All Answers (80)

- A research paper is based on original research.

- The kind of research may vary, depending on your field or the topic, (experiments, survey, interview, questionnaire, etc.), but authors need to collect and analyze raw data and conduct an original study.

- The research paper will be based on the analysis and interpretation of this data.

- Research articles will usually contain:

- a summary or “abstract”

- a description of the research

- the results they got

- the significance of the results.

- A narrative review explains the existing knowledge on a topic based on all the published research available on the topic.

- A systematic review searches for the answer to a particular question in the existing scientific literature on a topic.

- A meta-analysis compares and combines the findings of previously published studies, usually to assess the effectiveness of an intervention or mode of treatment.

- http://www.editage.com/insights/what-is-the-difference-between-a-research-paper-and-a-review-paper

- https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=919157084787290&id=906562632713402

Similar questions and discussions

- Asked 9 January 2019

- Asked 7 November 2019

- Asked 29 February 2024

- Asked 4 February 2022

- Asked 30 October 2013

- Asked 15 July 2023

- Asked 8 July 2023

- Asked 4 July 2023

Related Publications

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

- How to find Psychology Articles

- Using APA Thesaurus

Empirical Articles

- How to Limit to Empirical Articles

- What are they?

- How to Read them?

- Main Sections

Empirical articles are those in which authors report on their own study. The authors will have collected data to answer a research question. Empirical research contains observed and measured examples that inform or answer the research question. The data can be collected in a variety of ways such as interviews, surveys, questionnaires, observations, and various other quantitative and qualitative research methods.

Empirical research is based on observed and measured phenomena and derives knowledge from actual experience rather than from theory or belief.

How do you know if a study is empirical? Read the subheadings within the article, book, or report and look for a description of the research "methodology." Ask yourself: Could I recreate this study and test these results?

Key characteristics to look for:

- Specific research questions to be answered

- Definition of the population, behavior, or phenomena being studied

- Description of the process used to study this population or phenomena, including selection criteria, controls, and testing instruments (such as surveys)

Another hint: some scholarly journals use a specific layout, called the "IMRaD" format, to communicate empirical research findings. Such articles typically have 4 components:

- Introduction : sometimes called "literature review" -- what is currently known about the topic -- usually includes a theoretical framework and/or discussion of previous studies

- Methodology: sometimes called "research design" -- how to recreate the study -- usually describes the population, research process, and analytical tools

- Results : sometimes called "findings" -- what was learned through the study -- usually appears as statistical data or as substantial quotations from research participants

- Discussion : sometimes called "conclusion" or "implications" -- why the study is important -- usually describes how the research results influence professional practices or future studies

General Advice

- Plan to read the article more than once

- Don't read it all the way through in one sitting, read strategically first.

- Identify relevant conclusions and limitations of study

Abstract: Get a sense of the article’s purpose and findings. Use it to assess if the article is useful for your research.

Skim: Review headings to understand the structure and label parts if needed.

Introduction/Literature Review: Identify the main argument, problem, previous work, proposed next steps, and hypothesis.

Methodology: Understand data collection methods, data sources, and variables.

Findings/Results: Examine tables and figures to see if they support the hypothesis without relying on captions.

Discussion/Conclusion: Determine if the findings support the argument/hypothesis and if the authors acknowledge any limitations.

Anatomy of a Research Paper by Richard D. Branson published in Respir Care. 2004 October; 49(10): 1222–1228.

How to Read a Scholarly Chemistry Artricle - Rider tutorial.

How to read and understand a scientific paper - a guide for non-scientists - Violent Metaphors (blog post).

Compare your article to this table to help determine you have located an empirical study/research report.

Look for the following words in the title/abstract: empirical, experiment, research, or study.

|

|

|

| Abstract | A short synopsis of the article’s content |

| Introduction | Need and rational of this particular research project with research question, statement, and hypothesis. |

| Literature Review (sometimes included in the Introduction) | Supporting their ideas with other scholarly research |

| Methods | Describes the methodology including a description of the participants, and a description of the research method, measure, research design, or approach to data analysis. |

| Results or Findings | Uses narrative, charts, tables, graphs, or other graphics to describe the findings of the paper |

| Discussion/Conclusion/Implications | Provides a discussion, summary, or conclusion, bringing together the research question, statement, |

| References | References all the articlesdiscussed and cited in the paper- mostly in the literature or results sections |

- << Previous: Using APA Thesaurus

- Next: How to Limit to Empirical Articles >>

- Last Updated: Sep 16, 2024 2:30 PM

- URL: https://guides.rider.edu/psy

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Korean Med Sci

- v.37(16); 2022 Apr 25

A Practical Guide to Writing Quantitative and Qualitative Research Questions and Hypotheses in Scholarly Articles

Edward barroga.

1 Department of General Education, Graduate School of Nursing Science, St. Luke’s International University, Tokyo, Japan.

Glafera Janet Matanguihan

2 Department of Biological Sciences, Messiah University, Mechanicsburg, PA, USA.

The development of research questions and the subsequent hypotheses are prerequisites to defining the main research purpose and specific objectives of a study. Consequently, these objectives determine the study design and research outcome. The development of research questions is a process based on knowledge of current trends, cutting-edge studies, and technological advances in the research field. Excellent research questions are focused and require a comprehensive literature search and in-depth understanding of the problem being investigated. Initially, research questions may be written as descriptive questions which could be developed into inferential questions. These questions must be specific and concise to provide a clear foundation for developing hypotheses. Hypotheses are more formal predictions about the research outcomes. These specify the possible results that may or may not be expected regarding the relationship between groups. Thus, research questions and hypotheses clarify the main purpose and specific objectives of the study, which in turn dictate the design of the study, its direction, and outcome. Studies developed from good research questions and hypotheses will have trustworthy outcomes with wide-ranging social and health implications.

INTRODUCTION

Scientific research is usually initiated by posing evidenced-based research questions which are then explicitly restated as hypotheses. 1 , 2 The hypotheses provide directions to guide the study, solutions, explanations, and expected results. 3 , 4 Both research questions and hypotheses are essentially formulated based on conventional theories and real-world processes, which allow the inception of novel studies and the ethical testing of ideas. 5 , 6

It is crucial to have knowledge of both quantitative and qualitative research 2 as both types of research involve writing research questions and hypotheses. 7 However, these crucial elements of research are sometimes overlooked; if not overlooked, then framed without the forethought and meticulous attention it needs. Planning and careful consideration are needed when developing quantitative or qualitative research, particularly when conceptualizing research questions and hypotheses. 4

There is a continuing need to support researchers in the creation of innovative research questions and hypotheses, as well as for journal articles that carefully review these elements. 1 When research questions and hypotheses are not carefully thought of, unethical studies and poor outcomes usually ensue. Carefully formulated research questions and hypotheses define well-founded objectives, which in turn determine the appropriate design, course, and outcome of the study. This article then aims to discuss in detail the various aspects of crafting research questions and hypotheses, with the goal of guiding researchers as they develop their own. Examples from the authors and peer-reviewed scientific articles in the healthcare field are provided to illustrate key points.

DEFINITIONS AND RELATIONSHIP OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

A research question is what a study aims to answer after data analysis and interpretation. The answer is written in length in the discussion section of the paper. Thus, the research question gives a preview of the different parts and variables of the study meant to address the problem posed in the research question. 1 An excellent research question clarifies the research writing while facilitating understanding of the research topic, objective, scope, and limitations of the study. 5

On the other hand, a research hypothesis is an educated statement of an expected outcome. This statement is based on background research and current knowledge. 8 , 9 The research hypothesis makes a specific prediction about a new phenomenon 10 or a formal statement on the expected relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable. 3 , 11 It provides a tentative answer to the research question to be tested or explored. 4

Hypotheses employ reasoning to predict a theory-based outcome. 10 These can also be developed from theories by focusing on components of theories that have not yet been observed. 10 The validity of hypotheses is often based on the testability of the prediction made in a reproducible experiment. 8

Conversely, hypotheses can also be rephrased as research questions. Several hypotheses based on existing theories and knowledge may be needed to answer a research question. Developing ethical research questions and hypotheses creates a research design that has logical relationships among variables. These relationships serve as a solid foundation for the conduct of the study. 4 , 11 Haphazardly constructed research questions can result in poorly formulated hypotheses and improper study designs, leading to unreliable results. Thus, the formulations of relevant research questions and verifiable hypotheses are crucial when beginning research. 12

CHARACTERISTICS OF GOOD RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Excellent research questions are specific and focused. These integrate collective data and observations to confirm or refute the subsequent hypotheses. Well-constructed hypotheses are based on previous reports and verify the research context. These are realistic, in-depth, sufficiently complex, and reproducible. More importantly, these hypotheses can be addressed and tested. 13

There are several characteristics of well-developed hypotheses. Good hypotheses are 1) empirically testable 7 , 10 , 11 , 13 ; 2) backed by preliminary evidence 9 ; 3) testable by ethical research 7 , 9 ; 4) based on original ideas 9 ; 5) have evidenced-based logical reasoning 10 ; and 6) can be predicted. 11 Good hypotheses can infer ethical and positive implications, indicating the presence of a relationship or effect relevant to the research theme. 7 , 11 These are initially developed from a general theory and branch into specific hypotheses by deductive reasoning. In the absence of a theory to base the hypotheses, inductive reasoning based on specific observations or findings form more general hypotheses. 10

TYPES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Research questions and hypotheses are developed according to the type of research, which can be broadly classified into quantitative and qualitative research. We provide a summary of the types of research questions and hypotheses under quantitative and qualitative research categories in Table 1 .

| Quantitative research questions | Quantitative research hypotheses |

|---|---|

| Descriptive research questions | Simple hypothesis |

| Comparative research questions | Complex hypothesis |

| Relationship research questions | Directional hypothesis |

| Non-directional hypothesis | |

| Associative hypothesis | |

| Causal hypothesis | |

| Null hypothesis | |

| Alternative hypothesis | |

| Working hypothesis | |

| Statistical hypothesis | |

| Logical hypothesis | |

| Hypothesis-testing | |

| Qualitative research questions | Qualitative research hypotheses |

| Contextual research questions | Hypothesis-generating |

| Descriptive research questions | |

| Evaluation research questions | |

| Explanatory research questions | |

| Exploratory research questions | |

| Generative research questions | |

| Ideological research questions | |

| Ethnographic research questions | |

| Phenomenological research questions | |

| Grounded theory questions | |

| Qualitative case study questions |

Research questions in quantitative research

In quantitative research, research questions inquire about the relationships among variables being investigated and are usually framed at the start of the study. These are precise and typically linked to the subject population, dependent and independent variables, and research design. 1 Research questions may also attempt to describe the behavior of a population in relation to one or more variables, or describe the characteristics of variables to be measured ( descriptive research questions ). 1 , 5 , 14 These questions may also aim to discover differences between groups within the context of an outcome variable ( comparative research questions ), 1 , 5 , 14 or elucidate trends and interactions among variables ( relationship research questions ). 1 , 5 We provide examples of descriptive, comparative, and relationship research questions in quantitative research in Table 2 .

| Quantitative research questions | |

|---|---|

| Descriptive research question | |

| - Measures responses of subjects to variables | |

| - Presents variables to measure, analyze, or assess | |

| What is the proportion of resident doctors in the hospital who have mastered ultrasonography (response of subjects to a variable) as a diagnostic technique in their clinical training? | |

| Comparative research question | |

| - Clarifies difference between one group with outcome variable and another group without outcome variable | |

| Is there a difference in the reduction of lung metastasis in osteosarcoma patients who received the vitamin D adjunctive therapy (group with outcome variable) compared with osteosarcoma patients who did not receive the vitamin D adjunctive therapy (group without outcome variable)? | |

| - Compares the effects of variables | |

| How does the vitamin D analogue 22-Oxacalcitriol (variable 1) mimic the antiproliferative activity of 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D (variable 2) in osteosarcoma cells? | |