- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 16 May 2013

The integration of occupational therapy into primary care: a multiple case study design

- Catherine Donnelly 1 , 2 ,

- Christie Brenchley 3 ,

- Candace Crawford 4 &

- Lori Letts 5

BMC Family Practice volume 14 , Article number: 60 ( 2013 ) Cite this article

30k Accesses

45 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

For over two decades occupational therapists have been encouraged to enhance their roles within primary care and focus on health promotion and prevention activities. While there is a clear fit between occupational therapy and primary care, there have been few practice examples, despite a growing body of evidence to support the role. In 2010, the province of Ontario, Canada provided funding to include occupational therapists as members of Family Health Teams, an interprofessional model of primary care. The integration of occupational therapists into this model of primary care is one of the first large scale initiatives of its kind in North America. The objective of the study was to examine how occupational therapy services are being integrated into primary care teams and understand the structures supporting the integration.

A multiple case study design was used to provide an in-depth description of the integration of occupational therapy. Four Family Health Teams with occupational therapists as part of the team were identified. Data collection included in-depth interviews, document analyses, and questionnaires.

Each Family Health Team had a unique organizational structure that contributed to the integration of occupational therapy. Communication, trust and understanding of occupational therapy were key elements in the integration of occupational therapy into Family Health Teams, and were supported by a number of strategies including co-location, electronic medical records and team meetings. An understanding of occupational therapy was critical for integration into the team and physicians were less likely to understand the occupational therapy role than other health providers.

With an increased emphasis on interprofessional primary care, new professions will be integrated into primary healthcare teams. The study found that explicit strategies and structures are required to facilitate the integration of a new professional group. An understanding of professional roles, trust and communication are foundations for interprofessional collaborative practice.

Peer Review reports

There is a clear fit between occupational therapy (OT) and primary care. Both view health in a holistic manner and seek to support individuals and communities in achieving and maintaining a healthy lifestyle [ 1 , 2 ]. While there is evidence to support the role of occupational therapy in health promotion and prevention, there have been few practice examples of occupational therapy within primary care settings [ 3 , 4 ].

The lack of an occupational therapy presence in primary care can be attributed to a number of factors [ 5 ]. First and foremost, there has not been funding for occupational therapy in primary care, both in Canada and internationally [ 5 ]. Second, primary care has traditionally been delivered in solo practitioner models [ 6 ]. Finally, the occupational therapy profession has traditionally focused on the rehabilitation or remediation of function versus health promotion [ 7 ].

In 2003, the First Ministers of Canada committed to ensuring that half of Canadians would have access to multidisciplinary primary care teams by 2011 [ 8 ]. While this has not yet been achieved, the province of Ontario’s commitment to health reform has resulted in the establishment of Family Health Teams, an innovative model of interprofessional primary care [ 9 ]. There are currently 200 teams that serve approximately 25% of the province’s population.

Each Family Health Team is interprofessional in nature; however there is considerable variability in structure, size and organizational dimensions. A Family Health Team may consist of a single site or may be comprised of multiple offices that have common programs or structures such as an electronic medical record (EMR), programs and management. The complement of interdisciplinary health professionals also varies according to the specific needs of the community.

While the initial list of funded interdisciplinary health providers did not include occupational therapists, in March 2009 the Ontario government committed funds to include occupational therapy services in Family Health Teams [ 10 ]. At the initiation of the study, 20 teams had occupational therapists within their team complement. Ontario’s initiative is one of the first examples of large-scale integration of occupational therapy into primary care teams in North America.

A growing number of national and international studies have documented the structures and processes to support interprofessional primary care teams [ 11 , 12 ]. However, few of these studies have included occupational therapy within the team complement and no study has exclusively examined the implementation of occupational therapy into a new or existing primary care team.

A handful of articles have examined the integration of other professionals into primary care teams [ 13 – 15 ]. While these findings might provide insights for occupational therapy, each profession entering primary care will have unique features and support the team through unique roles. Occupational therapists have a long history in working in team- based environments and therefore the implementation of occupational therapy services may be experienced differently than professions that have been primarily consultative.

Interprofessional teams are poised to play a greater role in the delivery of primary care in Canada and abroad [ 16 , 17 ]. It is anticipated that more disciplines will continue to enter primary care, making it critical to understand how professionals are being introduced into primary care teams. The purpose of the paper is to examine how occupational therapy is being integrated into primary care teams and understand the structures and processes supporting the integration.

The study aimed to explore the primary guiding question: What structures and processes support the integration of occupational therapy in Family Health Teams? A multiple case study design [ 18 ] was conducted that included four Family Health Team sites within the province of Ontario, Canada. Case study research seeks to investigate real life experiences within the context in which it occurs and involves the collection of detailed information using a variety of data collection methods [ 18 – 20 ]. As there are few documented examples of occupational therapists in primary care, a case study design enabled an in-depth exploration of how occupational therapy was being integrated into interprofessional primary care teams. As per case study methodology as outlined by Yin [ 18 ], each case provided an opportunity for the replication of the outlined questions and methods.

Site identification

Four cases (Family Health Teams) were identified from the approximately 20 that employed occupational therapists at the time of the study. The sites were chosen to reflect different dimensions of service provision that may influence the role and integration of occupational therapy. The literature on interprofessional collaborative practice has identified certain elements that support interprofessional collaborative care, including: (1) EMR, (2) team size, and (3) co-location of health professionals [ 6 , 13 ]. Each dimension was considered in the identification of the cases. Two further dimensions were considered in the case selection; academic versus community and rural versus urban. While there is little evidence examining the role of occupational therapist in primary care, the literature has described occupational therapy working with a wide range of client populations and conditions [ 4 ]. Therefore the nature and duration of clinical experience of occupational therapist as well as the full-time equivalency (FTE) were also thought to be important elements to consider in the identification of cases. Purposeful sampling of sites was used with the intent to sample breadth of communities, teams, and occupational therapists.

Participants

Information letters were sent to the Executive Director at each site describing the study and seeking approval for participation. All occupational therapists working at the Family Health Teams were asked to participate. The Executive Director and the lead physician were also invited due to their leadership and decision making roles on the team. In addition, any member of the team that provided collaborative patient care with the occupational therapist was also considered to be eligible for the study. The occupational therapist(s) at each Family Health Team acted as the main contact for liaising and coordinating interviews with the staff.

Ethics approval was provided by Queen’s University Health Sciences Research Ethics Board.

Data collection

Data collection drew on multiple forms of evidence including semi-structured interviews, document analyses and questionnaires. The principal investigator (CD) visited each Family Health Team to retrieve documents for analyses, distribute questionnaires and conduct interviews with key informants. See Table 1 for list of disciplines interviewed at each site. All interviews were conducted between the February-May 2012 using a semi-structured interview guide. Questions were developed by the research team and were informed by the literature on interprofessional collaborative primary care [ 11 , 12 ]. Questions fell under five broad categories including; roles (how would you describe your role, how did you establish your role), physical space (i.e. location of team members and primary care sites), community collaborations, collaborative practice (i.e. nature, processes and structures to support collaborative practice) and processes (i.e. nature and use of electronic medical record). Additional questions regarding funding for occupational therapy were included in the interview guide for the Executive Director and questions related to clinical practice were removed.

Program documents included job descriptions, occupational therapy assessments, team mission and vision. The web pages of each Family Health Team were viewed to obtain further information about team collaboration, and sites were contacted if further questions about the nature of occupational therapy services were identified. Two sites were contacted to clarify demographic information (number of sites and number of physicians) and the occupational therapist(s) at each site was contacted to provide further details on the referral process to occupational therapy. A Family Health Team Profile was completed by each Executive Director to obtain descriptive information about the Family Health Team demographics, including the type of electronic medical record system, number of rostered patients and health professional make-up. An Occupational Therapy Profile was completed by each occupational therapist to obtain information about their educational background and work experiences.

Data analyses

Both within-case and cross-case analyses were conducted [ 18 , 19 ]. Pattern matching was then used as the overall analytic strategy. This approach “compares an empirically based pattern with a predicted one” [18, p 106], where propositions are developed prior to data collection in order to identify a predicted pattern of variables. Propositions for this study were derived from the literature on interprofessional collaborative practice. A number of factors have been found to support interprofesional practice. One of these is the extent to which there is a shared understanding of team members’ roles and scopes of practice [ 12 ]. This was felt to be particularly relevant for the study as occupational therapists were new professionals within the teams. Studies have also identified the nature of team processes and organizational structures to be important influences on collaboration, and the nature of team processes was anticipated to influence the integration of occupational therapy [ 21 ]. The use of electronic medical records (EMR) have become standard in Family Health Teams in Ontario, Canada [ 22 ] and have already been found to support internal communication. Occupational therapists’ access and use of EMRs thus become an important element to consider [ 13 ]. Therefore, the two study propositions were:

Integration of occupational therapy into the Family Health Team will depend on the understanding of the occupational therapy role by team members, and structures to support interprofessional collaborative practice.

The EMR will be pivotal in supporting the integration of occupational therapy.

Each case was first analyzed individually, followed by cross-site analyses to determine common themes [ 19 ]. Data obtained from documents were extracted using apriori document analysis forms. Tables and matrixes were used to visually examine the data for each case and across cases. Qualitative interview data were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim by a research assistant. Atlas ti, a qualitative data analysis and research software program, was used to code data and identify themes both within and across cases. All transcripts were read and re-read by the primary author and preliminary codes were established. A number of strategies were used to establish trustworthiness [ 23 , 24 ]. Four transcripts were read and independently coded by a second investigator (LL) using the preliminary coding structure. Transcripts were selected from four different health professions to ensure the coding structure could be applied across transcripts. Any discrepancies in coding were noted and discussed until consensus was reached. Two revisions to the coding structure were made; the first involved collapsing two codes into one code, the second revision involved renaming a code to better reflect the essence of the statements being captured.

A second strategy to establish trustworthiness involved member checking. Occupational therapists were provided with a preliminary summary of their site and asked to contact the primary author if any errors were noted, or if additional information should be included. None of the participants reported any errors or provided further information.

A third strategy involved triangulation of data methods, sources and investigators. The study included a number of data methods including interviews, questionnaires and document analyses. Each contributed to the understanding of how occupational therapists are integrated into primary care and structures to support the integration. Participants included members from a range of disciplines across four sites in order to provide different perspectives and experiences on the integration of occupational therapists. Finally, the investigation team was made up four occupational therapists; two academics (CD, LL), one administrative (CB) and one clinician working in primary care (CC). The diversity of the team brought unique perspectives to the design, implementation and analyses and grounded the study in both research and practice.

Table 2 provides a description of the four sites. Patient rosters ranged from 7,200 to 42,000 patients and sites were located in both rural and urban centres. Three sites were community sites and one was an academic site. The academic site had a dual mandate to provide both primary care services, and to educate medical students/residents and other health disciplines. Occupational therapists were all relatively new to their positions with a range of 3 to 18 months. Occupational therapists in two sites had less than five years experience, while two sites had occupational therapists with 15 and more years of experience. Each site had a unique complement of health providers, which included: chiropodists, psychologists, social workers, dieticians, physician assistants, pharmacists, patient educators, mental health workers, health promoters, respiratory therapists, case managers, nurses, nurse practitioners, and physicians.

Case 1: Very large rural community family health team

In case one the occupational therapists along with the interdisciplinary health providers and administrative staff were located in two buildings in the largest regional town, while the physicians worked in distributed clinics across the region. Despite the lack of co-location each key informant reported a strong sense of collaboration and connection. The EMR was the key structure for collaboration and integration of occupational therapy into the Family Health Team; face-to-face interaction with physicians is limited.

Case 2: Small urban community family health team

Case two was a small Family Health Team with four separate sites located in a large urban setting with a culturally diverse patient population. The occupational therapist was located with nursing and other interdisciplinary health providers across the street from one of the main physician sites.

Lack of co-location was described as a key barrier in the integration of occupational therapy. The Family Health Team was planning a new building to house all team members.

Case 3: Large rural family health team, one occupational therapist

Case three was a large rural Family Health Team providing primary care to approximately 45% of the local population. Having only been recently approved as a Family Health Team, the team was largely in the development phase. The Family Health Team had four separate sites. The occupational therapists and other interdisciplinary health providers were located at one site along with the administrative staff. Each site had its own EMR that could not communicate between sites. At the time of the study the occupational therapist did not have access to the EMR. The long-term goal was to move to one accessible EMR system.

Case 4: Urban academic family health team

Case four was an urban academic Family Health Team with two sites; each with a full interprofessional complement of professions. Services were organized by interprofessional care teams, where patients were designated to a team of clinicians. Two full-time occupational therapists worked between the two sites. The Family Health Team was part of the university Department of Family Medicine and therefore had a dual objective of providing primary care services and training family medicine residents, along with an expectation of research.

Cross case analysis

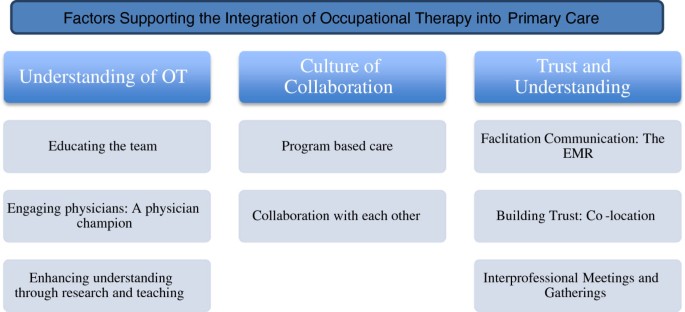

Three main themes and eight subthemes were identified that influenced integration of occupational therapists into the Family Health Teams: understanding of occupational therapy, collaboration, communication and trust. See Figure 1 for visual outline of the themes and subthemes.

Themes and Subthemes.

1. Understanding occupational therapy

Fundamentally, an understanding of occupational therapy was critical and the tipping point for integration into the team. As referrals originated from team members, a basic understanding of the role of occupational therapy and patients who could benefit were required. Interdisciplinary health care providers and nurses described previous and current working relationships with occupational therapists, which in turn led to an understanding of the occupational therapy role within Family Health Teams.

The other integrated health professionals have been amazing. So I think they have a good idea of what OT is and I think a lot of them have worked with OT in the past (Occupational Therapist) 2P11:33:82

An understanding of and experience with occupational therapy in turn created a level of respect and natural integration into the team.

There’s a very healthy respect among our IHPs [interdisciplinary health providers] for the skill sets that they have and there’s a desire to include one another in the initiatives that they take on (Executive Director) 2P1:14:23

However, physicians had less direct day-to-day contact with occupational therapists, and less familiarity with the role of occupational therapy.

I feel that most family doctors didn’t and still don’t have a great understanding of the OT role (Physician) 4P4:1:6

Ultimately respondents felt that when team members had a good understanding of occupational therapy, referrals were made to the service.

That was the basis of our success here… that people really get what we do (Occupational Therapist). 1P1:93:220

Conversely, less familiarity with the role of occupational therapy was felt to result in an underutilization of services.

It’s underused, because I don’t think everyone knows what the OT can do (Nurse Practitioner) 2P5:5:13

Educating the team

Occupational therapists across all sites used a number of strategies to educate physicians and team members about occupational therapy including formal presentations, educational rounds, ‘meet and greets’, information booths, brochures and information letters. Occupational therapists provided information about the profession, particularly, the services they currently offered within the Family Health Team along with examples of potential services that could be provided. All opportunities were seen as positive and contributing to an increased understanding of occupational therapy.

I’m working on trying to educate the team in what OTs can do (Occupational Therapist) 2P5:5:13

Promoting the role of occupational therapy was a particularly important element during the early integration into the team and a role that needed to be consciously adopted by occupational therapists.

Engaging physicians: a physician champion

Physicians were seen as critical to the integration of occupational therapists as they were a key source of referrals. The identification of a physician lead, or physician liaison for occupational therapy was seen as an important strategy to enhance physician understanding and champion the occupational therapy discipline within the Family Health Team. Information from physician to physician was felt to have greater authority and credibility.

The communication was coming from a physician that they trust and he was saying ‘Use these services’ (Occupational Therapist) 1P1:94:221

A lack of physician engagement regarding the occupational therapy role was seen to significantly influence the integration of the role.

My regret about the occupational therapy program is that we haven’t done a good enough job of engaging the physician group in establishing that program … we’re definitely not utilizing her to the fullest extent that we could in her occupational specialization (Executive Director) 2P1:6:11

Enhancing understanding through research and teaching

Team members at the academic Family Health Team had additional requirements to engage in both research and teaching activities. As a result, site four had a number of unique strategies that served to increase the understanding of occupational therapy and support a deeper integration into the team.

There are two absolutely primary mandates of clinical care and education and then obviously scholarly work … you can’t really separate clinical cases from education in this [Family Health Team]. So our nurses are doing so much of the clinical care and we are reviewing our teaching and the allied health group, including the OT’s, are absolutely woven into that. From co-bookings, to horizontal electives, to the more structured learning opportunities with the rounds, to working with different groups of the learners so family medicine residents and allied health workers sharing the case together. Some of the family residents teach the more junior learner and then going to an allied health person for some input. (Physician) 4P4:26:38

Training was a reciprocal and iterative activity; building an understanding of occupational therapy and supporting collaborative patient care.

Occupational therapists were expected to participate in interprofessional teaching rounds, one-on-one resident training, education clinics and occupational therapy student mentorship. Each activity offered an opportunity for the team to be exposed to the role of occupational therapy and work with the discipline.

One of the really helpful things that [the occupational therapists] did is to take some time at our interprofessional rounds and walk us through their vision in 6 months. Here are the types of cases that are getting referred, and here are success stories of why it was helpful to be involved. Here are some priority areas for us to think about. And that was again, a really nice diplomatic way of increasing our understanding. (Physician) 4P4:11:14

None of the other sites had formal structures in which to provide physician education, nor were they involved in any residency training.

A number of team members were involved in research with occupational therapists at the affiliated University and had been previously exposed to the role of occupational therapy in primary care. This research experience was felt to support the integration of the occupational therapist by offering a deeper understanding of the role.

I think we were better positioned already for a level, a deeper level of understanding of the role of OT and PT in primary care. (Physician) 4P4:3:8

Enhancing understanding through research cultivated opportunities to integrate occupational therapy into clinic programs.

I didn’t know much about chronic pain and [the OT] has been working in chronic pain for over 20 years so I was interested in being part of the research project and she has been mentoring me in that role so we have now created a new [pain] group (Social Worker) 4P2:25:43

2. A culture of collaboration

While an understanding of occupational therapy facilitated referrals to occupational therapists, collaboration was seen as a benchmark of occupational therapy’s integration into Family Health Teams. Each site agreed that building team collaboration was a deliberate and intentional process.

We very deliberately, pretty much, do everything as a team with clinical work. (Physician) 4P4:22:36

Strong collaboration among interdisciplinary health providers was seen across all sites. In some cases assessments and interventions were conducted together with other interdisciplinary health providers.

[Occupational therapist] and I have gone to a couple of home visits together; because the person was appropriate for my services and her services . (Social Worker) 3P9:20:74

As many interdisciplinary health providers were also new to primary care they collaborated to support each other in their mutual integration into the team.

[the interdisciplinary health providers] … that’s my biggest source of support … so a lot of my referrals are actually coming from other allied health (Occupational Therapist) 3P11:33:82

Opportunities to collaborate at the point of care supported the integration of occupational therapy. However across sites there was notably less collaboration between the interdisciplinary health providers and physicians.

The physician group is not engaged strongly enough with the other health providers (Executive Director) 2P1:16:23

Less collaboration with physicians was attributed to a number of factors. First and foremost primary care has traditionally been practiced as a solo enterprise.

[The physicians] have always been the general practitioner that has done everything for their patients (Executive Director) 3P7:41:104

There was a sense that interprofessional collaboration may diminish the physicians’ sense of control.

I am sure there are a lot of physicians that do not like the ball being taken from them (Physician) 1P5:16:53

As physicians could see the benefit of occupational therapy services, opportunities for collaboration would be enhanced.

As physicians refer to the occupational therapist and have comfort level in what they’re getting back, that [occupational therapy] will improve [patient care]. More referrals will come and there will be more of an interaction. (Physician) 3P10:55:22

As the shift to interprofessional teams was relatively new, it was also felt that physicians were not used to having access to so many resources and needed to gain comfort with a team based approach

They’re not used to having this type of resources available to them on a daily basis in their clinics (Executive Director) 3P7:49:118

Program based care

Each site offered a number of health promotion and chronic disease management and prevention programs ranging from mental health, falls prevention, chronic pain and diabetes management. Aligning occupational therapy services within current programs of care provided an opportunity to integrate into the team.

There’s a COPD group that’s held here and I provide some consultation to that group and I’m slowly tying to integrate myself into some other groups we’re going to be starting (Occupational Therapist) 1P1:4:9

Integration into programs occurred in a number of ways. In some cases occupational therapists noted a gap in program offerings, which led to the development of a new program. More frequently, occupational therapists or other team members identified programs that had high volume or wait lists that would benefit from an occupational therapy perspective.

Our program is really busy .. it’s great to have that opportunity to put that person with [the occupational therapist] that specializes and might be able to have the time to do it (Social Worker) 3P9:38:86

The program focus also provided new opportunities to collaborate and engage in program development.

One of our ideas is to have a caregiver stress program … that was going to be a collaboration between [occupational therapist] and myself and the mental health therapist (Social Worker) 3P9:31:76

At two of the sites physicians were aligned with specific programs, which provided a formal opportunity to connect with physicians.

Collaborating with each other

As essential as interprofessional collaboration was in supporting the integration of occupational therapy, the ability to collaborate with occupational therapy colleagues both within and outside of the Family Health Team was also important. Occupational therapists shared resources, engaged in clinical consultations, and provided strategies to each other to support integration into the team.

This whole group of occupational therapists [working in FHT’s] are pioneers in the OT role. So any way we can support one another (Occupational Therapist) 1P3:62:225

Having two occupational therapists at one Family Health Team was seen to facilitate the integration of the role in number of ways. Most importantly it provided professional support and confidence to try new roles and share ideas. Simply having two individuals increased exposure to occupational therapy within the Family Health Team and enhanced the professional profile.

To have each other … I can’t imagine doing this role … as one person (Occupational Therapist) 1P1:27:54

3. Communication and trust

Communication and trust were essential components of collaboration and the integration of occupational therapy, and were supported by a number of strategies including co-location, EMR and formal and informal meetings and gatherings.

Facilitating communication: the electronic medical record

A single and accessible EMR was a critical feature in supporting the integration of occupational therapy into Family Health Teams. The EMR enabled both formal and informal communication with physicians and other team members through the messaging system and patient records. The instant messaging function served as an internal communication system.

I think the EMR allows us to communicate effectively. We can instant message and that piece provides opportunity (Social Worker) 1P2:24:65

The EMR provided a means to collaborate when co-location of team members was not possible, supporting virtual interprofessional teams.

The EMR is fabulous because not only can you communicate back and forth, but everyone can see everyone’s charts. It is like one big family medicine chart. (Physician) 1P5:12:41

The EMR was also seen to support efficient and informed clinical practice.

The OT gets a snapshot of that patient and they’re better equipped to do what they need to do. And to get to the point a lot quicker (Physician) 1P3:40:127

Building trust: co-location

While an integrated EMR provided a foundation for communication, the opportunity for team members to connect face-to-face was pivotal in developing relationships and supporting the integration of occupational therapy. The importance of occupational therapy being located with the entire team cannot be underestimated. Only one of the four cases had a full interprofessional team located in the same building, however two of the other cases had plans to consolidate their clinics. Co-location offered opportunities for occupational therapists to engage in informal communication, have ‘hallway consults’ and be visually present; all of which contributed to understanding the OT role and building of trust.

There are other times where you are not sure if [occupational therapy] would be helpful or not. It is much more relevant to have an [informal] case conversation first and then whatever you end up writing in [the EMR] references the conversation, which is obviously much richer. (Physician ) 3P4:15:22

One site created team rooms where all team members worked in a common desk area, along with common lunch rooms and meeting spaces. When co-location occurred only with other interdisciplinary health providers and nurses, the benefits of communication and understanding were also identified; however as physicians were a key source of referrals their physical presence was viewed as a critical.

Physically we don’t see the [physicians] very often. I think that can spark some reminders, or spark some ideas, as well as is great for relationship building. (Social Worker) 4P9:45:110

Interprofessional meetings and gatherings

Formal meetings provided opportunities for team members to interact, most notably in cases where occupational therapists were off-site from physicians.

Just going to the meeting is an opportunity to talk, see what everyone does (Occupational Therapist) 1P1:66:143

Just as important as meetings, social gatherings supported team building and enabled the team to get to know each other as individuals.

We’ve spent some good networking sessions … you get to know that person and all of a sudden “OK, I’ll trust you with my patient” (Executive Director) 1P3:19:73

Ultimately, the integration of occupational therapy into the primary care teams was grounded in three key factors: trust, understanding, and communication. Meetings and gatherings provided opportunities to facilitate connections and team building.

Integration has been described as one end of the continuum that extends from complete autonomy and independence at one extreme to complete integration of professional services at the other [ 25 ]. In this study, the integration of occupational therapists was observed to range along this continuum and varying both between and within the Family Health Teams. In these cases, occupational therapists were more integrated with the other interdisciplinary health providers such as social workers and pharmacists, than with either nurses or physicians. Vertical and horizontal integration have been used to describe the integration of health services. Horizontal integration refers to the grouping of similar organizations or services, while vertical integration “services a network of organizations that provides or arranges to provide a coordinated continuum of services to a defined community” [ 26 ]. Within the Family Health Teams occupational therapists tended to work closely and collaborate with other allied health professionals in the delivery of health services. Allied health professionals had a common goal of supporting the physicians in the delivery of primary care. While each had different disciplinary perspectives, occupational therapists could be described as being horizontally integrated with their allied health counterparts. Each was remunerated in a similar fashion, worked in close physical proximity, had informal communication structures and provided some degree of collaborative patient care.

In contrast, occupational therapists had relatively little direct contact and few interactions with physicians. The occupational therapy role was seen as supporting the continuum of health services within the Family Health Team and integration could be envisioned as being vertical relative to the physicians. This is congruent with the literature reporting that a key barrier in the implementation of interprofessional teams has been the hierarchical structures within primary care [ 27 – 29 ]. Of note, however is a recent study suggesting that younger cohorts of male physicians are more likely to collaborate with occupational therapists, and other health professionals than older counterparts or younger female physicians [ 30 ]. Occupational therapists at the academic site experienced a high level of integration into the team, including with physicians, nurses and other interdisciplinary health providers. Given the focus on collaboration and teamwork in the training of family medicine practitioners, it makes sense that younger physicians who have had experience with interprofessional collaboration enact this as practicing physicians.

This study also found that the extent of occupational therapists integration into Family Health Teams was influenced by the nature of services provided. Integration was more fully realized within chronic and complex disease programs of care, such as a diabetes or seniors program, than one- time referrals to occupational therapy. This study suggests a plausible explanation for this phenomenon. The more structured programs served to identify and formalize a team of providers and offered an opportunity to develop common patient goals and a shared vision of service delivery. This in turn facilitated communication and the implementation of processes to support the programs, such as meetings and common program outcomes. Russell and colleagues [ 31 ] examined chronic disease management programs and found that organizational features had the greatest influence on patient outcomes. In particular, those clinics with the presence of a nurse practitioner had better outcomes and high-quality chronic disease management care was found most commonly in clinics with an interprofessional team. The success of chronic disease management programs in part contributed to the collaborative nature of the care, highlighting the importance and benefit of integrating professionals within programs of care.

At the same time it is recognized that not all care provided by occupational therapists within primary care teams will be program based. Leutz [ 32 ] described five laws for integration, one of which was “you can integrate all of the services for some of the people, some of the services for all of the people, but you can’t integrate all of the services for all of the people” (p. 83). This may hold true for occupational therapists in the sense that certain elements of their work within the teams may be more individual and consultative in nature.

The literature has described a number of factors that support interprofessional teamwork in primary care [ 21 , 28 , 29 ]. Xyrichis and Lowton [ 21 ] identified both team structures and team processes that support collaboration. As was seen in this study, Family Health Teams with a greater number of structures to support teamwork had occupational therapists that were more fully integrated. Processes that were seen to support the integration of occupational therapist included co-location, a common EMR, formal and informal communication structures and team meetings. Each of these processes naturally facilitated the integration of occupational therapy into the team by building trust, understanding and familiarity. It was the processes and structures, more than the personal characteristics of the occupational therapist that appeared to influence integration. However, the two sites with the greatest supports also had occupational therapists with substantial work experience. Further research is required to explore the relationship between personal characteristics and the integration process. A recent study [ 22 ] examined teamwork within twenty-one Family Health Teams in Ontario, Canada. A survey was used to identify organizational factors contributing to the functioning of an interprofessional primary care team. The study found that culture, leadership and EMR functionality predicted team climate. Each of these elements was also seen to support the integration of occupational therapy in this study.

Studies examining the integration of pharmacists reported some lack of understanding of the role of the pharmacist, but not to the extent found in this current study [ 13 – 15 ]. It is not surprising that the lack of understanding about a profession’s role impedes their integration into the team. The current siloed approach to the training of health care practitioners and practice of health care may be a contributor [ 33 ]. For disciplines new to primary care, there will be a natural learning curve about both the roles of other professionals as well as their own role in a new practice setting. Kolodziejak and colleagues [ 15 ] outlined a step-by-step process to support the integration of pharmacists into established primary care teams. Part of the process of integration included defining the role prior to joining a team and determining early credibility. The current study found a number of intentional strategies were used to integrate occupational therapy within the team, however more formal guidelines to Family Health Teams who have new professionals could further support integration.

The study also found that informal and formal support by occupational therapy colleagues was also helpful in supporting integration. Communities of practice have been shown to support knowledge translation [ 34 , 35 ] and this could be another intentional strategy that is enacted.

Interprofessional education occurs “when two or more professions learn with, from and about each other to improve collaboration and the quality of care ” [ 36 ]. In the case of the academic Family Health Team, the educational processes designed to support physician learning provided a natural opportunity and environment to educate team members of their roles. Without such structures, the occupational therapists at the other sites did not have a forum to provide formal physician education. A growing amount of literature on interprofessional education suggests that experiential based learning is an effective strategy to teach health professionals the competencies of collaborative practice [ 37 , 38 ]. While there are only a small number of academic Family Health Teams, there is much to be learned about the research and teaching activities that can support the integration of new team members.

It must be remembered that this study was limited to four sites. Given the influence of structures and processes on collaboration and integration, it is anticipated that additional sites might have provided further insights into the variety of other assets or constraints to interprofessional integration. Occupational therapy is a new profession within Family Health Teams and the paper focuses on the early integration in the team. Therefore the integration of occupational therapy will continue to evolve and be shaped by individual, team and organizational development. The study was exploratory in nature and while it provides insights into the emerging role of occupational therapy within a primary care context, the results cannot be broadly generalized.

This study builds the foundation for further research. A longitudinal study would provide insights into how health professionals are integrated into teams over time. It would also be of value to understand how integration influences health outcomes and more specifically to use a framework of systems integration in which to understand interprofessional primary care teams. Finally, it would be important to explore how professionals within Family Health Teams were integrated into the broader community services.

Conclusions

With an increased emphasis on interprofessional primary care, new professions will continue to be integrated into primary care teams. Based on the current study the following strategies and structures should be considered to support occupational therapists entering primary care teams.

Occupational therapists entering primary care need to formally include the education of team members in their professional role. Education on the role of occupational therapy and services provided needs to be directed to all team members, with specific focus on physicians.

Occupational therapists need to ensure they gain full access to the EMR to support both informal communication, through the internal messaging features, as well as formal patient documentation and referrals.

Occupational therapy fieldwork placements can provide a mechanism to engage the team in learning about other professions. Student occupational therapists should also be involved in the education of team members.

When possible, occupational therapists should actively participate in educating students from other health disciplines, including offering shadowing opportunities, providing handouts, arranging co-bookings or developing inservices.

Occupational therapists need to actively develop their role in existing interprofessional groups and programs offered within the primary care setting. Working within a structured program provides an opportunity to work closely with team members and can facilitate a deeper understanding of the occupational therapy.

Occupational therapists need to attend networking events, meetings, inservices and social functions to build relationships with team members.

The study adds to the growing body of literature that has identified structures and processes to support interprofessional collaboration in primary healthcare. Exploring the integration of an emerging discipline in primary care underscores the necessity of ensuring team members have an understanding of the roles and scope of each team member. The study also highlights the critical role that communication structures, such as formalized meetings and EMR’s, have in supporting the integration of new professions.

Letts LJ: Optimal positioning of occupational therapy. Can J Occup Ther. 2011, 78: 209-219. 10.2182/cjot.2011.78.4.2.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Howey M, Angelucci T, Johnston D, Townsend E: Occupation-based program development in primary health care. OT Now. 2003, 11 (3): 4-7.

Google Scholar

Clark F, Azen SP, Zemke R, Jackson J, Carlson M, Mandel D: Occupational therapy for independent-living older adults: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1997, 278: 1321-1326. 10.1001/jama.1997.03550160041036.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Richardson J, Letts L, Chan D, Stratford P, Hand C, Price D, Hilts L, Coman L, Edwards M, Baptiste S, Law M: Rehabilitation in a primary care setting for persons with chronic illness: A randomized controlled trial. Prim Care Res Devo. 2010, 11: 382-395. 10.1017/S1463423610000113.

Article Google Scholar

Klaiman D: Increasing access to occupational therapy in primary health care. OT Now. 2004, 6 (1): 14-1.

McColl MA, Shortt S, Godwin M, Smith K, Rowe K, O’Brien P, Donnelly C: Models for integrating rehabilitation and primary care: A scoping study. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2009, 90: 523-531.

Tse S, Penman M, Simms F: Literature review: Occupational therapy and primary health care. NZ J Occup Ther. 2003, 50: 17-23.

Health Canada: First Minister’s Meeting on the Future of Health Care 2004: A 10-year plan to strengthen health care. 2004, http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hcs-sss/delivery-prestation/fptcollab/2004-fmm-rpm/index-eng.php ,

Hutchinson B, Levesque JF, Strumpe E, Coyle N: Primary health care in Canada: Systems in motion. MilBank Q. 2011, 89: 256-288. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00628.x.

Ontario Society of Occupational Therapists: Occupational therapy and Family Health Teams. http://www.osot.on.ca/eng/otinont/familyHealthTeams.asp ,

Belle Brown J, Lewis L, Ellis K, Beckhoff C, Stewart M, Freeman T, Kasperski MJ: Sustaining primary health care teams: What is needed. J Interprof Care. 2010, 24: 463-465. 10.3109/13561820903417608.

Sargeant J, Loney E, Murphy G: Effective interprofessional teams: Contact is not enough to build a team. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2008, 28: 228-234. 10.1002/chp.189.

Bradley F, Elvey R, Ashcroft DM, Hassell K, Kendall J, Sibbald B, Noyce P: The challenge of integrating community pharmacists into the primary health care team: A case study of local pharmaceutical services (LPS) pilots and interprofessional collaboration. J Interprof Care. 2008, 22: 387-398. 10.1080/13561820802137005.

Dolovich L, Pottie K, Kaczorowski J, Farrell B, Austin Z, Rodriguez C, Gaebel K, Sellors C: Integrating family medicine and pharmacy to advance primay care therapeutics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008, 83: 913-917. 10.1038/clpt.2008.29.

Kolodziejak L, Remillard A, Neubauer S: Integration of a primary healthcare pharmacist. J Interprof Care. 2010, 24: 274-284. 10.3109/13561820903130149.

Drummond D: Commission on the Reform of Ontario’s Public Services: Public Service for Ontarians: A Path to sustainability and excellence. 2012, Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario

Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology: Time for Transformative Change: A review of the 2004 Health Accord. 2012

Yin RK: Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 2009, Thousand Oaks California: SAGE Publications Inc, 3

Stake R: The Art of Case Study Research. 1995, Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications Inc

Salminen AL, Harra T, Lautama T: Conducting case study research in occupational therapy. Aus Occup Ther J. 2006, 53: 3-8.

Xyrichis A, Lowton K: What fosters or prevents interprofessional teamworking in primary and community care? A literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2008, 45: 140-153. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.01.015.

Howard M, Brazil K, Akhtar-Danesh N, Agarwal G: Self-reported teamwork in family health team practices in Ontario. Can Fam Phys. 2011, 57 (May): e185-e191.

Krefting L: Rigor in qualitative research: The assessment of trusworthiness. Am J Occup Ther. 1991, 43: 214-222.

Golafshani N: Understanding reliability and validity in qualitative research. Qual Report. 2003, 8: 597-607.

Glendinning C: Breaking down barriers: Integrating health and care services for older people in England. Health Policy. 2003, 65: 139-151. 10.1016/S0168-8510(02)00205-1.

Devers KJ, Shortell SM, Gilles RR, Anderson DA, Mitchell , Erickson K: Implementing organized delivery systems: An integration scorecard. Health Care Manage Rev. 1994, 19 (3): 7-30.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Craigie FC, Hobbs RF: Exploring the organizational culture of exemplary community health center practices. Fam Med. 2004, 36: 733-738.

PubMed Google Scholar

Poulton BC, West MA: The determinants of effectiveness in primary health care teams. J Interprof Care. 1999, 13: 7-18. 10.3109/13561829909025531.

Shaw A, De Lusignan S, Rowlands G: Do primary care professionals work as a team: A qualitative study. J of Interprof Care. 2005, 19: 396-405. 10.1080/13561820500053454.

Sarma S, Devlin RA, Thind A, Chu MK: Canadian family physicians’ decision to collaborate: Age, period and cohort effects. Soc Sci Med. 2012, 75: 1811-1819. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.07.028.

Russell GM, Dabrouge S, Hogg W, Geneau R, Muldoon L, Tuna M: Managing chronic pain in Ontario primary care: The impact of organizational factors. Ann Fam Med. 2009, 7: 309-318. 10.1370/afm.982.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Leutz WN: Five laws for integrating medical and social services: Lessons from the United States and the United Kingdom. Milbank Q. 1999, 77: 77-110. 10.1111/1468-0009.00125.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Pecukonis E, Doyle O, Bliss DL: Reducing barriers to interprofessional training: promoting interprofessional cultural competence. J Interprof Care. 2008, 22: 417-428. 10.1080/13561820802190442.

Barwick MA, Peters J, Boydell K: Getting to update: Do communities of practices support the implementation of evidence-based practice?. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psych. 2009, 18: 16-29.

Li LC, Grimshaw JM, Nielsen C, Judd M, Coyte PC Graham ID: Use of communities of practice in business and health care sectors: A systematic review. Implement Sci. 2009, 4: 27-10.1186/1748-5908-4-27. http://www.implementationscience.com/content/4/1/27 ,

CAIPE: Defining IPE. http://www.caipe.org.uk/resources/defining-ipe/ ,

Payler J, Meyer E, Humphris D: Pedagogy for IP education – what do we know and how can we evaluate it?. Learn Health Soc Care. 2008, 7: 64-78. 10.1111/j.1473-6861.2008.00175.x.

Sargeant J: Theories to aid understanding and implementation of IP education. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2009, 29: 178-184. 10.1002/chp.20033.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2296/14/60/prepub

Download references

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the Family Health Teams who participated in the study. We would like to thank Dr. Lyn Shulha for her support and insightful comments on the final drafts of the manuscript. We would also like to thank Kristina Sheridan and Tanya Cerovic for their assistance with transcription and data management. The study was funded by the Primary Healthcare Seed Funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Rehabilitation Therapy, Queen’s University, 31 George Street, Kingston, ON, K7L 3N6, Canada

Catherine Donnelly

Faculty of Education, Queen’s University, 31 George Street, Kingston, ON, K7L 3N6, Canada

Ontario Society of Occupational Therapists, 55 Eglinton Ave. E., Suite 210, Toronto, ON, M4P 1G8, Canada

Christie Brenchley

Wise Elephant Family Health Team, 280 Main Street North, Brampton, ON, L6V 1P6, Canada

Candace Crawford

School of Rehabilitation Science, McMaster University, 1400 Main St. W, Hamilton, ON, L8S 1C7, Canada

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Catherine Donnelly .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Authors’ contributions

CD, LL, CB, CC contributed to the design of the study. CD participated in the coordination and acquisition of data. CD, LL, CB contributed to the analyses and interpretation of data. CD participated in the draft of the manuscript and LL, CB, CC provided feedback and approval of the final draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Authors’ original file for figure 1

Rights and permissions.

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Donnelly, C., Brenchley, C., Crawford, C. et al. The integration of occupational therapy into primary care: a multiple case study design. BMC Fam Pract 14 , 60 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-14-60

Download citation

Received : 06 February 2013

Accepted : 07 May 2013

Published : 16 May 2013

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-14-60

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Inteprofessional primary care

- Collaboration

- Family health teams

- Multiple case study design

- Occupational therapy

- Integration

BMC Primary Care

ISSN: 2731-4553

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The integration of occupational therapy into primary care: a multiple case study design

2013, BMC Family Practice

Related Papers

The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy

Wen-Pin Chang

Primary Health Care Research & Development

Rachelle Ashcroft

Aim: The aim of the study was to describe practices that support collaboration in interprofessional primary health care teams, and identify performance indicators perceived to measure the impact of this collaboration from the perspective of interprofessional health providers. Background: Despite the surge of interprofessional primary health care models implemented across Canada, there is little evidence as to whether or not the intended outcomes of primary health care teams have been achieved. Part of the challenge is determining the most appropriate measures that can demonstrate the value of collaborative care. To date, little remains known about performance measurement from the providers contributing to the collaborative care process in interprofessional primary care teams. Having providers from a range of disciplinary backgrounds assist in the development of performance measures can help identify measures most relevant to demonstrate the value of collaborative care on the intende...

BMC Family Practice

Carola Döpp

Background: Interprofessional primary care (IPC) teams provide comprehensive and coordinated care and are ideally equipped to support those populations most at risk of adverse health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic, including older adults, and patients with chronic physical and mental health conditions. There has been little focus on the experiences of healthcare teams and no studies have examined IPC practice during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. The objective of the study was to describe the state of interprofessional health provider practice within IPC teams during the COVID-19 pandemic. Methods: Observational cross-sectional design. A web-based survey was deployed to IPC providers working in team-based primary care clinics in the province of Ontario, Canada. The survey included 26 close-ended and six open-ended questions. Close-ended questions were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Content analysis was used to analyze the open-ended questions.

Deborah Marshall

Renee Misfeldt

Health and Interprofessional Practice

Karen Slonim

Mary Stoykov

Lori Letts , Ainsley Moore

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Revues modernistes, revues engagées

Douglas B McBride

Journal of multidisciplinary healthcare

Victoria Suen

Syed Aljunid

Scott Reeves

Catriona Kennedy

Mathematica Policy Research Reports

Angela Gerolamo

Implementation Science

Carol Cancelliere

Scott Reeves , Kathleen (Kate) Rice

British Journal of Occupational Therapy

Lynette Mackenzie

Karen Schouten

Pauline O'Brien, RP

Family Practice

Valeria Herskovic , Cecilia Saint-Pierre

Sinead Dufour

Joyce Halliday , Rod Sheaff , Stephen Peckham , Sheena Asthana

International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Marie-pascale Pomey

BMC Health Services Research

Health Informatics Journal

Josephine McMurray

Edel Tierney

Kimberly Poong

BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine

Stacie Salsbury

Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare

dilani nanayakkara

Rural and Remote Health

Helen Brown

Journal of allied health

Mohammed Nadar

Healthcare Quarterly

Siegrid Deutschlander

Joanne Goldman

Marisa Birkmeier

International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders

American Journal of Occupational Therapy

Penelope Cleveland

mukhlis syukur

Maureen Nash

Mona Morsy , Anita Fisher , Tracey Chambers , Laurie Kennedy , Sinead Dufour , Sue Bookey-Bassett , Jenny Ploeg

Occupational Therapy International

Wesam Darawsheh

Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI '15

Lee Sanders

Physical & Occupational Therapy In Pediatrics

Atefeh Esfandiari

Yumna Abdelrahman

Ruta Valaitis

International Congress on Applications of Lasers & Electro-Optics

Ehsan Foroozmehr

Kathleen Mathieson

Irma Ruslina Defi

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Case Studies for Contemporary OT Practice

Already purchased? Please sign in to view.

Do you need to re-use or reproduce this work?

current document all documents

Advanced search

Table of Contents

- Table of Contents v 6

Remember login

Enable two-factor authentication codes.

Forgot password

Please log in to view your account information. Don't have any account? You can register for one now.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Workplace-based rehabilitation with garment workers: A multiple case study

Affiliation.

- 1 Division of Occupational Therapy, Department of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa.

- PMID: 35527606

- DOI: 10.3233/WOR-210540

Background: Garment workers are at risk of developing work-related upper limb disorders (WRULD) due to the highly repetitive nature of their work. Workplace-based rehabilitation (WBR) facilitates improvement in work performance by providing intervention at the worker's place of work.

Objective: This study aims to determine the documented outcomes of workplace-based occupational therapy rehabilitation of garment workers with upper limb conditions.

Methods: A multiple case study design was used through a retrospective record review. All garment workers with upper limb conditions who were treated at a student occupational therapy practice in Cape Town, South Africa, with pre- and post-intervention outcome assessment, were included in the study (n = 7). Data were extracted from occupational therapy and medical files.

Results: 70% of the cases (n = 5) improved after WBR while 30% of cases showed no improvement or deterioration. Participants received 3- 5 individual WBR sessions of approximately 30 minutes each, over a period of 4 to 6 weeks. Interventions included workstation adaptations, job rotation, psychoeducation, work task modification, assistive technology and exercise programmes. Outcome measures most commonly used were the RULA, DASH, Boston Carpal Tunnel Questionnaire and pain intensity using the VAS.

Conclusion: Workplace-based occupational therapy can be effective at improving upper limb function, pain and ergonomic risk amongst garment workers with upper limb conditions.

Keywords: Occupational therapy; return to work; sewing machine operators; textile workers; upper limb.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Differences in ergonomic and workstation factors between computer office workers with and without reported musculoskeletal pain. Rodrigues MS, Leite RDV, Lelis CM, Chaves TC. Rodrigues MS, et al. Work. 2017;57(4):563-572. doi: 10.3233/WOR-172582. Work. 2017. PMID: 28826196

- Workplace management of upper limb disorders: a systematic review. Dick FD, Graveling RA, Munro W, Walker-Bone K; Guideline Development Group. Dick FD, et al. Occup Med (Lond). 2011 Jan;61(1):19-25. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqq174. Epub 2010 Dec 2. Occup Med (Lond). 2011. PMID: 21127200 Review.

- Presentation and response of patients with upper extremity repetitive use syndrome to a multidisciplinary rehabilitation program: a retrospective review of 24 cases. Barthel HR, Miller LS, Deardorff WW, Portenier R. Barthel HR, et al. J Hand Ther. 1998 Jul-Sep;11(3):191-9. doi: 10.1016/s0894-1130(98)80037-9. J Hand Ther. 1998. PMID: 9730095

- Ergonomics and efficient workplace design for hand-sewn footwear artisans in Kolhapur, India. Jadhav GS, Arunachalam M, Salve UR. Jadhav GS, et al. Work. 2020;66(4):849-860. doi: 10.3233/WOR-203230. Work. 2020. PMID: 32831216

- Prevention of low back pain: basic ergonomics in the workplace and the clinic. Halpern M. Halpern M. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1992 Oct;6(3):705-30. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3579(05)80134-7. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1992. PMID: 1477898 Review.

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- MedlinePlus Health Information

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

Analysis of University Students’ Mental Health from the Perspective of Occupational Harmony

- Find this author on Google Scholar

- Find this author on PubMed

- Search for this author on this site

- ORCID record for Yijun Liu

- ORCID record for Jin Xing

- For correspondence: [email protected]

- Info/History

- Supplementary material

- Preview PDF

Background Mental health problems are common among university students. Based on the Model of Occupational Harmony, we investigated the relationship between occupational engagement and mental health among Chinese university students.

Methods A mixed methods approach was adopted. A total of 734 Chinese university students responded to online questionnaires: a socio-demographic questionnaire, the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale, the WHOQOL-BREF, and a self-designed Occupational Harmony Questionnaire. Individual interviews with 11 university students and a focus group of four students provided qualitative data.

Results Anxiety, depression, and stress were reported by 11.9%, 9.4%, and 2.9% of the participants, respectively. The level of occupational harmony was negatively correlated with depression, anxiety, and stress (p<.001). The DASS-21 score was significantly different among students who spent different amounts of time on the following activities: exercise, sleep, rest, reflective and consulting activities, study, work, and leisure and entertainment (P<.05). In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the key occupational factors contributing to university students’ mental health problems included excessive mental engagement and insufficient physical engagement, excessive active engagement and insufficient quiet engagement, insufficient social engagement, excessive or insufficient Gong (productive) engagement, and insufficient De (virtuous) engagement, Zhi (rational) engagement, and Kang (health maintenance) engagement, lack of coherence within the family, school, social systems, as well as inadequate schedule planning and time management.

Conclusions Occupational disharmony is related to university students’ mental health problems. Occupational therapy can promote university students’ mental well-being by enhancing occupational harmony.

Competing Interest Statement

The authors have declared no competing interest.

Funding Statement

National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (Youth Clinical Research Project of Peking University First Hospital)2024YC10

Author Declarations

I confirm all relevant ethical guidelines have been followed, and any necessary IRB and/or ethics committee approvals have been obtained.

The details of the IRB/oversight body that provided approval or exemption for the research described are given below:

Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of Peking University First Hospital

I confirm that all necessary patient/participant consent has been obtained and the appropriate institutional forms have been archived, and that any patient/participant/sample identifiers included were not known to anyone (e.g., hospital staff, patients or participants themselves) outside the research group so cannot be used to identify individuals.

I understand that all clinical trials and any other prospective interventional studies must be registered with an ICMJE-approved registry, such as ClinicalTrials.gov. I confirm that any such study reported in the manuscript has been registered and the trial registration ID is provided (note: if posting a prospective study registered retrospectively, please provide a statement in the trial ID field explaining why the study was not registered in advance).

I have followed all appropriate research reporting guidelines, such as any relevant EQUATOR Network research reporting checklist(s) and other pertinent material, if applicable.

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose. This article is based on the unpublished doctoral dissertation completed by YL. The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article and supporting information files.

YL thanks Dr. Zhen-Su She for his guidance throughout this work; Dr. Zhen Huang and Dr. Rongli Wang for their mentorship; Dr. Shuna Song, Dr. Rong Li, Dr. Lei Zhang, and her parents for their encouragement and support.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

View the discussion thread.

Supplementary Material

Thank you for your interest in spreading the word about medRxiv.

NOTE: Your email address is requested solely to identify you as the sender of this article.

Citation Manager Formats

- EndNote (tagged)

- EndNote 8 (xml)

- RefWorks Tagged

- Ref Manager

- Tweet Widget

- Facebook Like

- Google Plus One

Subject Area

- Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology

- Addiction Medicine (342)

- Allergy and Immunology (665)

- Anesthesia (180)

- Cardiovascular Medicine (2625)

- Dentistry and Oral Medicine (314)

- Dermatology (222)

- Emergency Medicine (397)

- Endocrinology (including Diabetes Mellitus and Metabolic Disease) (930)

- Epidemiology (12175)

- Forensic Medicine (10)

- Gastroenterology (756)

- Genetic and Genomic Medicine (4064)

- Geriatric Medicine (385)

- Health Economics (676)

- Health Informatics (2625)

- Health Policy (997)

- Health Systems and Quality Improvement (979)

- Hematology (360)

- HIV/AIDS (845)

- Infectious Diseases (except HIV/AIDS) (13659)

- Intensive Care and Critical Care Medicine (790)

- Medical Education (398)

- Medical Ethics (109)

- Nephrology (430)

- Neurology (3832)

- Nursing (209)

- Nutrition (570)

- Obstetrics and Gynecology (734)

- Occupational and Environmental Health (690)

- Oncology (2008)

- Ophthalmology (581)

- Orthopedics (238)

- Otolaryngology (304)

- Pain Medicine (250)

- Palliative Medicine (73)

- Pathology (471)

- Pediatrics (1107)

- Pharmacology and Therapeutics (459)

- Primary Care Research (447)

- Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology (3400)

- Public and Global Health (6499)

- Radiology and Imaging (1390)

- Rehabilitation Medicine and Physical Therapy (806)

- Respiratory Medicine (869)

- Rheumatology (400)

- Sexual and Reproductive Health (407)

- Sports Medicine (338)

- Surgery (441)

- Toxicology (52)

- Transplantation (185)

- Urology (165)

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Online First

- Multiple metal exposures associate with higher amyotrophic lateral sclerosis risk and mortality independent of genetic risk and correlate to self-reported exposures: a case-control study

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0009-0009-7966-1322 Dae-Gyu Jang 1 , 2 ,

- John F Dou 3 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6952-3326 Emily J Koubek 1 , 2 ,

- Samuel Teener 1 , 2 ,

- Lili Zhou 4 ,

- Kelly M Bakulski 3 ,

- Bhramar Mukherjee 5 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9894-5325 Stuart A Batterman 6 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9162-2694 Eva L Feldman 1 , 2 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8780-6637 Stephen A Goutman 1 , 2

- 1 Department of Neurology , University of Michigan , Ann Arbor , Michigan , USA

- 2 NeuroNetwork for Emerging Therapies , University of Michigan , Ann Arbor , Michigan , USA

- 3 Department of Epidemiology , University of Michigan , Ann Arbor , Michigan , USA

- 4 Department of Biostatistics , Corewell Health , Royal Oak , Michigan , USA

- 5 Department of Biostatistics , University of Michigan , Ann Arbor , Michigan , USA

- 6 Department of Environmental Health Sciences , University of Michigan , Ann Arbor , Michigan , USA

- Correspondence to Dr Stephen A Goutman; sgoutman{at}med.umich.edu

Background The pathogenesis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) involves both genetic and environmental factors. This study investigates associations between metal measures in plasma and urine, ALS risk and survival and exposure sources.

Methods Participants with and without ALS from Michigan provided plasma and urine samples for metal measurement via inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. ORs and HRs for each metal were computed using risk and survival models. Environmental risk scores (ERS) were created to evaluate the association between exposure mixtures and ALS risk and survival and exposure source. ALS (ALS-PGS) and metal (metal-PGS) polygenic risk scores were constructed from an independent genome-wide association study and relevant literature-selected single-nucleotide polymorphisms.

Results Plasma and urine samples from 454 ALS and 294 control participants were analysed. Elevated levels of individual metals, including copper, selenium and zinc, significantly associated with ALS risk and survival. ERS representing metal mixtures strongly associated with ALS risk (plasma, OR=2.95, CI=2.38–3.62, p<0.001; urine, OR=3.10, CI=2.43–3.97, p<0.001) and poorer ALS survival (plasma, HR=1.37, CI=1.20–1.58, p<0.001; urine, HR=1.44, CI=1.23–1.67, p<0.001). Addition of the ALS-PGS or metal-PGS did not alter the significance of metals with ALS risk and survival. Occupations with high potential of metal exposure associated with elevated ERS. Additionally, occupational and non-occupational metal exposures were associated with measured plasma and urine metals.

Conclusion Metals in plasma and urine associated with increased ALS risk and reduced survival, independent of genetic risk, and correlated with occupational and non-occupational metal exposures. These data underscore the significance of metal exposure in ALS risk and progression.

- EPIDEMIOLOGY

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2024-333978

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Contributors D-GJ, JFD, LZ, KMB, BM, SB, ELF and SAG conceived and designed the study. ST and SAG contributed to the acquisition of the data. D-GJ, JD and KMB performed the statistical analyses. D-GJ, EK and SAG interpreted the data, drafted the text and prepared the figures. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript. SAG is the guarantor of the study.

Funding Funding was provided by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) (R01NS127188); National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) (K23ES027221, R01ES030049); Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (R01TS000344); ALS Association (20-IIA-532, 20-PP-661); NeuroNetwork for Emerging Therapies; Peter R. Clark Fund for ALS Research; Robert and Katherine Jacobs Environmental Health Initiative; Richard Stravitz Foundation; Coleman Therapeutic Discovery Fund; Scott L. Pranger ALS Clinic Fund; the Dr. Randall W. Whitcomb Fund for ALS Genetics; University of Michigan. Metals analysis was carried out at the Dartmouth Trace Element Core Facility, which is supported by Dartmouth Cancer Center with NCI Cancer Center Support Grant 5P30 CA023108.