Why I Think All Schools Should Abolish Homework

H ow long is your child’s workweek? Thirty hours? Forty? Would it surprise you to learn that some elementary school kids have workweeks comparable to adults’ schedules? For most children, mandatory homework assignments push their workweek far beyond the school day and deep into what any other laborers would consider overtime. Even without sports or music or other school-sponsored extracurriculars, the daily homework slog keeps many students on the clock as long as lawyers, teachers, medical residents, truck drivers and other overworked adults. Is it any wonder that,deprived of the labor protections that we provide adults, our kids are suffering an epidemic of disengagement, anxiety and depression ?

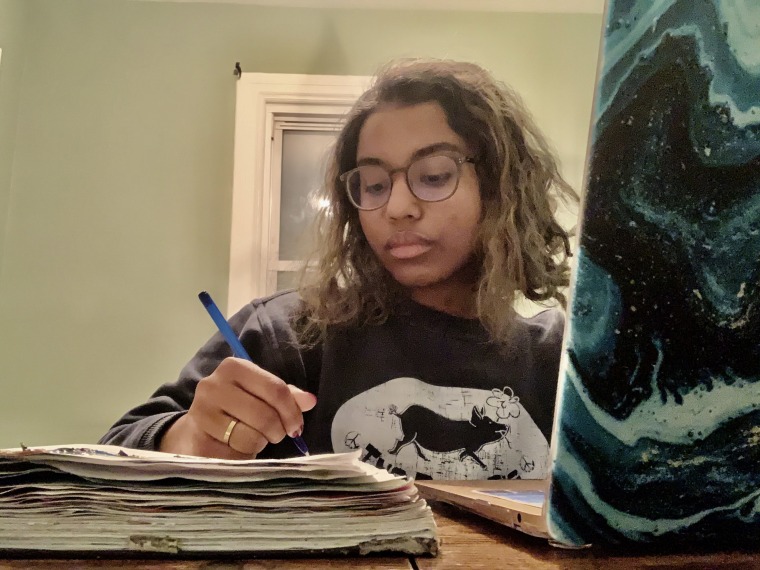

With my youngest child just months away from finishing high school, I’m remembering all the needless misery and missed opportunities all three of my kids suffered because of their endless assignments. When my daughters were in middle school, I would urge them into bed before midnight and then find them clandestinely studying under the covers with a flashlight. We cut back on their activities but still found ourselves stuck in a system on overdrive, returning home from hectic days at 6 p.m. only to face hours more of homework. Now, even as a senior with a moderate course load, my son, Zak, has spent many weekends studying, finding little time for the exercise and fresh air essential to his well-being. Week after week, and without any extracurriculars, Zak logs a lot more than the 40 hours adults traditionally work each week — and with no recognition from his “bosses” that it’s too much. I can’t count the number of shared evenings, weekend outings and dinners that our family has missed and will never get back.

How much after-school time should our schools really own?

In the midst of the madness last fall, Zak said to me, “I feel like I’m working towards my death. The constant demands on my time since 5th grade are just going to continue through graduation, into college, and then into my job. It’s like I’m on an endless treadmill with no time for living.”

My spirit crumbled along with his.

Like Zak, many people are now questioning the point of putting so much demand on children and teens that they become thinly stretched and overworked. Studies have long shown that there is no academic benefit to high school homework that consumes more than a modest number of hours each week. In a study of high schoolers conducted by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), researchers concluded that “after around four hours of homework per week, the additional time invested in homework has a negligible impact on performance.”

In elementary school, where we often assign overtime even to the youngest children, studies have shown there’s no academic benefit to any amount of homework at all.

Our unquestioned acceptance of homework also flies in the face of all we know about human health, brain function and learning. Brain scientists know that rest and exercise are essential to good health and real learning . Even top adult professionals in specialized fields take care to limit their work to concentrated periods of focus. A landmark study of how humans develop expertise found that elite musicians, scientists and athletes do their most productive work only about four hours per day .

Yet we continue to overwork our children, depriving them of the chance to cultivate health and learn deeply, burdening them with an imbalance of sedentary, academic tasks. American high school students , in fact, do more homework each week than their peers in the average country in the OECD, a 2014 report found.

It’s time for an uprising.

Already, small rebellions are starting. High schools in Ridgewood, N.J. , and Fairfax County, Va., among others, have banned homework over school breaks. The entire second grade at Taylor Elementary School in Arlington, Va., abolished homework this academic year. Burton Valley Elementary School in Lafayette, Calif., has eliminated homework in grades K through 4. Henry West Laboratory School , a public K-8 school in Coral Gables, Fla., eliminated mandatory, graded homework for optional assignments. One Lexington, Mass., elementary school is piloting a homework-free year, replacing it with reading for pleasure.

More from TIME

Across the Atlantic, students in Spain launched a national strike against excessive assignments in November. And a second-grade teacher in Texas, made headlines this fall when she quit sending home extra work , instead urging families to “spend your evenings doing things that are proven to correlate with student success. Eat dinner as a family, read together, play outside and get your child to bed early.”

It is time that we call loudly for a clear and simple change: a workweek limit for children, counting time on the clock before and after the final bell. Why should schools extend their authority far beyond the boundaries of campus, dictating activities in our homes in the hours that belong to families? An all-out ban on after-school assignments would be optimal. Short of that, we can at least sensibly agree on a cap limiting kids to a 40-hour workweek — and fewer hours for younger children.

Resistance even to this reasonable limit will be rife. Mike Miller, an English teacher at Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology in Alexandria, Va., found this out firsthand when he spearheaded a homework committee to rethink the usual approach. He had read the education research and found a forgotten policy on the county books limiting homework to two hours a night, total, including all classes. “I thought it would be a slam dunk” to put the two-hour cap firmly in place, Miller said.

But immediately, people started balking. “There was a lot of fear in the community,” Miller said. “It’s like jumping off a high dive with your kids’ future. If we reduce homework to two hours or less, is my kid really going to be okay?” In the end, the committee only agreed to a homework ban over school breaks.

Miller’s response is a great model for us all. He decided to limit assignments in his own class to 20 minutes a night (the most allowed for a student with six classes to hit the two-hour max). His students didn’t suddenly fail. Their test scores remained stable. And they started using their more breathable schedule to do more creative, thoughtful work.

That’s the way we will get to a sane work schedule for kids: by simultaneously pursuing changes big and small. Even as we collaboratively press for policy changes at the district or individual school level, all teachers can act now, as individuals, to ease the strain on overworked kids.

As parents and students, we can also organize to make homework the exception rather than the rule. We can insist that every family, teacher and student be allowed to opt out of assignments without penalty to make room for important activities, and we can seek changes that shift practice exercises and assignments into the actual school day.

We’ll know our work is done only when Zak and every other child can clock out, eat dinner, sleep well and stay healthy — the very things needed to engage and learn deeply. That’s the basic standard the law applies to working adults. Let’s do the same for our kids.

Vicki Abeles is the author of the bestseller Beyond Measure: Rescuing an Overscheduled, Overtested, Underestimated Generation, and director and producer of the documentaries “ Race to Nowhere ” and “ Beyond Measure. ”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People in AI 2024

- Inside the Rise of Bitcoin-Powered Pools and Bathhouses

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What Makes a Friendship Last Forever?

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- Your Questions About Early Voting , Answered

- Column: Your Cynicism Isn’t Helping Anybody

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Contact us at [email protected]

We need your support today

Independent journalism is more important than ever. Vox is here to explain this unprecedented election cycle and help you understand the larger stakes. We will break down where the candidates stand on major issues, from economic policy to immigration, foreign policy, criminal justice, and abortion. We’ll answer your biggest questions, and we’ll explain what matters — and why. This timely and essential task, however, is expensive to produce.

We rely on readers like you to fund our journalism. Will you support our work and become a Vox Member today?

- The Highlight

Nobody knows what the point of homework is

The homework wars are back.

by Jacob Sweet

As the Covid-19 pandemic began and students logged into their remote classrooms, all work, in effect, became homework. But whether or not students could complete it at home varied. For some, schoolwork became public-library work or McDonald’s-parking-lot work.

Luis Torres, the principal of PS 55, a predominantly low-income community elementary school in the south Bronx, told me that his school secured Chromebooks for students early in the pandemic only to learn that some lived in shelters that blocked wifi for security reasons. Others, who lived in housing projects with poor internet reception, did their schoolwork in laundromats.

According to a 2021 Pew survey , 25 percent of lower-income parents said their children, at some point, were unable to complete their schoolwork because they couldn’t access a computer at home; that number for upper-income parents was 2 percent.

The issues with remote learning in March 2020 were new. But they highlighted a divide that had been there all along in another form: homework. And even long after schools have resumed in-person classes, the pandemic’s effects on homework have lingered.

Over the past three years, in response to concerns about equity, schools across the country, including in Sacramento, Los Angeles , San Diego , and Clark County, Nevada , made permanent changes to their homework policies that restricted how much homework could be given and how it could be graded after in-person learning resumed.

Three years into the pandemic, as districts and teachers reckon with Covid-era overhauls of teaching and learning, schools are still reconsidering the purpose and place of homework. Whether relaxing homework expectations helps level the playing field between students or harms them by decreasing rigor is a divisive issue without conclusive evidence on either side, echoing other debates in education like the elimination of standardized test scores from some colleges’ admissions processes.

I first began to wonder if the homework abolition movement made sense after speaking with teachers in some Massachusetts public schools, who argued that rather than help disadvantaged kids, stringent homework restrictions communicated an attitude of low expectations. One, an English teacher, said she felt the school had “just given up” on trying to get the students to do work; another argued that restrictions that prohibit teachers from assigning take-home work that doesn’t begin in class made it difficult to get through the foreign-language curriculum. Teachers in other districts have raised formal concerns about homework abolition’s ability to close gaps among students rather than widening them.

Many education experts share this view. Harris Cooper, a professor emeritus of psychology at Duke who has studied homework efficacy, likened homework abolition to “playing to the lowest common denominator.”

But as I learned after talking to a variety of stakeholders — from homework researchers to policymakers to parents of schoolchildren — whether to abolish homework probably isn’t the right question. More important is what kind of work students are sent home with and where they can complete it. Chances are, if schools think more deeply about giving constructive work, time spent on homework will come down regardless.

There’s no consensus on whether homework works

The rise of the no-homework movement during the Covid-19 pandemic tapped into long-running disagreements over homework’s impact on students. The purpose and effectiveness of homework have been disputed for well over a century. In 1901, for instance, California banned homework for students up to age 15, and limited it for older students, over concerns that it endangered children’s mental and physical health. The newest iteration of the anti-homework argument contends that the current practice punishes students who lack support and rewards those with more resources, reinforcing the “myth of meritocracy.”

But there is still no research consensus on homework’s effectiveness; no one can seem to agree on what the right metrics are. Much of the debate relies on anecdotes, intuition, or speculation.

Researchers disagree even on how much research exists on the value of homework. Kathleen Budge, the co-author of Turning High-Poverty Schools Into High-Performing Schools and a professor at Boise State, told me that homework “has been greatly researched.” Denise Pope, a Stanford lecturer and leader of the education nonprofit Challenge Success, said, “It’s not a highly researched area because of some of the methodological problems.”

Experts who are more sympathetic to take-home assignments generally support the “10-minute rule,” a framework that estimates the ideal amount of homework on any given night by multiplying the student’s grade by 10 minutes. (A ninth grader, for example, would have about 90 minutes of work a night.) Homework proponents argue that while it is difficult to design randomized control studies to test homework’s effectiveness, the vast majority of existing studies show a strong positive correlation between homework and high academic achievement for middle and high school students. Prominent critics of homework argue that these correlational studies are unreliable and point to studies that suggest a neutral or negative effect on student performance. Both agree there is little to no evidence for homework’s effectiveness at an elementary school level, though proponents often argue that it builds constructive habits for the future.

For anyone who remembers homework assignments from both good and bad teachers, this fundamental disagreement might not be surprising. Some homework is pointless and frustrating to complete. Every week during my senior year of high school, I had to analyze a poem for English and decorate it with images found on Google; my most distinct memory from that class is receiving a demoralizing 25-point deduction because I failed to present my analysis on a poster board. Other assignments really do help students learn: After making an adapted version of Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book for a ninth grade history project, I was inspired to check out from the library and read a biography of the Chinese ruler.

For homework opponents, the first example is more likely to resonate. “We’re all familiar with the negative effects of homework: stress, exhaustion, family conflict, less time for other activities, diminished interest in learning,” Alfie Kohn, author of The Homework Myth, which challenges common justifications for homework, told me in an email. “And these effects may be most pronounced among low-income students.” Kohn believes that schools should make permanent any moratoria implemented during the pandemic, arguing that there are no positives at all to outweigh homework’s downsides. Recent studies , he argues , show the benefits may not even materialize during high school.

In the Marlborough Public Schools, a suburban district 45 minutes west of Boston, school policy committee chair Katherine Hennessy described getting kids to complete their homework during remote education as “a challenge, to say the least.” Teachers found that students who spent all day on their computers didn’t want to spend more time online when the day was over. So, for a few months, the school relaxed the usual practice and teachers slashed the quantity of nightly homework.

Online learning made the preexisting divides between students more apparent, she said. Many students, even during normal circumstances, lacked resources to keep them on track and focused on completing take-home assignments. Though Marlborough Schools is more affluent than PS 55, Hennessy said many students had parents whose work schedules left them unable to provide homework help in the evenings. The experience tracked with a common divide in the country between children of different socioeconomic backgrounds.

So in October 2021, months after the homework reduction began, the Marlborough committee made a change to the district’s policy. While teachers could still give homework, the assignments had to begin as classwork. And though teachers could acknowledge homework completion in a student’s participation grade, they couldn’t count homework as its own grading category. “Rigorous learning in the classroom does not mean that that classwork must be assigned every night,” the policy stated . “Extensions of class work is not to be used to teach new content or as a form of punishment.”

Canceling homework might not do anything for the achievement gap

The critiques of homework are valid as far as they go, but at a certain point, arguments against homework can defy the commonsense idea that to retain what they’re learning, students need to practice it.

“Doesn’t a kid become a better reader if he reads more? Doesn’t a kid learn his math facts better if he practices them?” said Cathy Vatterott, an education researcher and professor emeritus at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. After decades of research, she said it’s still hard to isolate the value of homework, but that doesn’t mean it should be abandoned.

Blanket vilification of homework can also conflate the unique challenges facing disadvantaged students as compared to affluent ones, which could have different solutions. “The kids in the low-income schools are being hurt because they’re being graded, unfairly, on time they just don’t have to do this stuff,” Pope told me. “And they’re still being held accountable for turning in assignments, whether they’re meaningful or not.” On the other side, “Palo Alto kids” — students in Silicon Valley’s stereotypically pressure-cooker public schools — “are just bombarded and overloaded and trying to stay above water.”

Merely getting rid of homework doesn’t solve either problem. The United States already has the second-highest disparity among OECD (the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) nations between time spent on homework by students of high and low socioeconomic status — a difference of more than three hours, said Janine Bempechat, clinical professor at Boston University and author of No More Mindless Homework .

When she interviewed teachers in Boston-area schools that had cut homework before the pandemic, Bempechat told me, “What they saw immediately was parents who could afford it immediately enrolled their children in the Russian School of Mathematics,” a math-enrichment program whose tuition ranges from $140 to about $400 a month. Getting rid of homework “does nothing for equity; it increases the opportunity gap between wealthier and less wealthy families,” she said. “That solution troubles me because it’s no solution at all.”

A group of teachers at Wakefield High School in Arlington, Virginia, made the same point after the school district proposed an overhaul of its homework policies, including removing penalties for missing homework deadlines, allowing unlimited retakes, and prohibiting grading of homework.

“Given the emphasis on equity in today’s education systems,” they wrote in a letter to the school board, “we believe that some of the proposed changes will actually have a detrimental impact towards achieving this goal. Families that have means could still provide challenging and engaging academic experiences for their children and will continue to do so, especially if their children are not experiencing expected rigor in the classroom.” At a school where more than a third of students are low-income, the teachers argued, the policies would prompt students “to expect the least of themselves in terms of effort, results, and responsibility.”

Not all homework is created equal

Despite their opposing sides in the homework wars, most of the researchers I spoke to made a lot of the same points. Both Bempechat and Pope were quick to bring up how parents and schools confuse rigor with workload, treating the volume of assignments as a proxy for quality of learning. Bempechat, who is known for defending homework, has written extensively about how plenty of it lacks clear purpose, requires the purchasing of unnecessary supplies, and takes longer than it needs to. Likewise, when Pope instructs graduate-level classes on curriculum, she asks her students to think about the larger purpose they’re trying to achieve with homework: If they can get the job done in the classroom, there’s no point in sending home more work.

At its best, pandemic-era teaching facilitated that last approach. Honolulu-based teacher Christina Torres Cawdery told me that, early in the pandemic, she often had a cohort of kids in her classroom for four hours straight, as her school tried to avoid too much commingling. She couldn’t lecture for four hours, so she gave the students plenty of time to complete independent and project-based work. At the end of most school days, she didn’t feel the need to send them home with more to do.

A similar limited-homework philosophy worked at a public middle school in Chelsea, Massachusetts. A couple of teachers there turned as much class as possible into an opportunity for small-group practice, allowing kids to work on problems that traditionally would be assigned for homework, Jessica Flick, a math coach who leads department meetings at the school, told me. It was inspired by a philosophy pioneered by Simon Fraser University professor Peter Liljedahl, whose influential book Building Thinking Classrooms in Mathematics reframes homework as “check-your-understanding questions” rather than as compulsory work. Last year, Flick found that the two eighth grade classes whose teachers adopted this strategy performed the best on state tests, and this year, she has encouraged other teachers to implement it.

Teachers know that plenty of homework is tedious and unproductive. Jeannemarie Dawson De Quiroz, who has taught for more than 20 years in low-income Boston and Los Angeles pilot and charter schools, says that in her first years on the job she frequently assigned “drill and kill” tasks and questions that she now feels unfairly stumped students. She said designing good homework wasn’t part of her teaching programs, nor was it meaningfully discussed in professional development. With more experience, she turned as much class time as she could into practice time and limited what she sent home.

“The thing about homework that’s sticky is that not all homework is created equal,” says Jill Harrison Berg, a former teacher and the author of Uprooting Instructional Inequity . “Some homework is a genuine waste of time and requires lots of resources for no good reason. And other homework is really useful.”

Cutting homework has to be part of a larger strategy

The takeaways are clear: Schools can make cuts to homework, but those cuts should be part of a strategy to improve the quality of education for all students. If the point of homework was to provide more practice, districts should think about how students can make it up during class — or offer time during or after school for students to seek help from teachers. If it was to move the curriculum along, it’s worth considering whether strategies like Liljedahl’s can get more done in less time.

Some of the best thinking around effective assignments comes from those most critical of the current practice. Denise Pope proposes that, before assigning homework, teachers should consider whether students understand the purpose of the work and whether they can do it without help. If teachers think it’s something that can’t be done in class, they should be mindful of how much time it should take and the feedback they should provide. It’s questions like these that De Quiroz considered before reducing the volume of work she sent home.

More than a year after the new homework policy began in Marlborough, Hennessy still hears from parents who incorrectly “think homework isn’t happening” despite repeated assurances that kids still can receive work. She thinks part of the reason is that education has changed over the years. “I think what we’re trying to do is establish that homework may be an element of educating students,” she told me. “But it may not be what parents think of as what they grew up with. ... It’s going to need to adapt, per the teaching and the curriculum, and how it’s being delivered in each classroom.”

For the policy to work, faculty, parents, and students will all have to buy into a shared vision of what school ought to look like. The district is working on it — in November, it hosted and uploaded to YouTube a round-table discussion on homework between district administrators — but considering the sustained confusion, the path ahead seems difficult.

When I asked Luis Torres about whether he thought homework serves a useful part in PS 55’s curriculum, he said yes, of course it was — despite the effort and money it takes to keep the school open after hours to help them do it. “The children need the opportunity to practice,” he said. “If you don’t give them opportunities to practice what they learn, they’re going to forget.” But Torres doesn’t care if the work is done at home. The school stays open until around 6 pm on weekdays, even during breaks. Tutors through New York City’s Department of Youth and Community Development programs help kids with work after school so they don’t need to take it with them.

As schools weigh the purpose of homework in an unequal world, it’s tempting to dispose of a practice that presents real, practical problems to students across the country. But getting rid of homework is unlikely to do much good on its own. Before cutting it, it’s worth thinking about what good assignments are meant to do in the first place. It’s crucial that students from all socioeconomic backgrounds tackle complex quantitative problems and hone their reading and writing skills. It’s less important that the work comes home with them.

Jacob Sweet is a freelance writer in Somerville, Massachusetts. He is a frequent contributor to the New Yorker, among other publications.

- Mental Health

- Social Policy

Most Popular

- Has The Bachelorette finally gone too far?

- iPad kids speak up

- The real reason Netanyahu won’t end the Gaza war

- Why Nvidia triggered a stock market freakout

- What the polls show about Harris’s chances against Trump

Today, Explained

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

This is the title for the native ad

More in The Highlight

From hot honey to buffalo ranch, we really, really, really love to make our dry foods wet.

How Ethan Mollick uses AI to help him write.

After FDA rejection, the industry is reconsidering its approach to approval.

We don’t need to pit dogs against humans.

Thomas Abt’s Bleeding Out has become foundational in tackling urban violence across the US.

Articles on Homework

Displaying 1 - 20 of 34 articles.

ChatGPT isn’t the death of homework – just an opportunity for schools to do things differently

Andy Phippen , Bournemouth University

How can I make studying a daily habit?

Deborah Reed , University of Tennessee

Debate: ChatGPT offers unseen opportunities to sharpen students’ critical skills

Erika Darics , University of Groningen and Lotte van Poppel , University of Groningen

Education in Kenya’s informal settlements can work better if parents get involved – here’s how

Benta A. Abuya , African Population and Health Research Center

‘There’s only so far I can take them’ – why teachers give up on struggling students who don’t do their homework

Jessica Calarco , Indiana University and Ilana Horn , Vanderbilt University

Talking with your teen about high school helps them open up about big (and little) things in their lives

Lindsey Jaber , University of Windsor

Primary school children get little academic benefit from homework

Paul Hopkins , University of Hull

How much time should you spend studying? Our ‘Goldilocks Day’ tool helps find the best balance of good grades and well-being

Dot Dumuid , University of South Australia and Tim Olds , University of South Australia

What’s the point of homework?

Katina Zammit , Western Sydney University

4 tips for college students to avoid procrastinating with their online work

Kui Xie , The Ohio State University and Shonn Cheng , Sam Houston State University

Online learning will be hard for kids whose schools close – and the digital divide will make it even harder for some of them

Jessica Calarco , Indiana University

How to help your kids with homework (without doing it for them)

Melissa Barnes , Monash University and Katrina Tour , Monash University

6 ways to establish a productive homework routine

Janine L. Nieroda-Madden , Syracuse University

Should parents help their kids with homework?

Daniel Hamlin , University of Oklahoma

Is homework worthwhile?

Robert H. Tai , University of Virginia

Teachers’ expectations help students to work harder, but can also reduce enjoyment and confidence – new research

Lars-Erik Malmberg , University of Oxford and Andrew J. Martin , UNSW Sydney

More primary schools could scrap homework – a former classroom teacher’s view

Lorele Mackie , University of Stirling

Modern life offers children almost everything they need, except daylight

Vybarr Cregan-Reid , University of Kent

Why students need more ‘math talk’

Matthew Campbell , West Virginia University and Johnna Bolyard , West Virginia University

Neuroscience is unlocking mysteries of the teenage brain

Lucy Foulkes, University of York

Related Topics

- K-12 education

Top contributors

Associate Professor of Sociology, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Professor of Educational Administration, Penn State

Associate professor, Pacific Lutheran University

Assistant professor, School of Psychology, L’Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa

Clinical psychologist; visiting fellow, Queensland University of Technology

Director, Learning and Teaching Education Research Centre, CQUniversity Australia

Associate Professor of Mathematics Education, West Virginia University

Associate Professor in Language, Literacy and TESL, University of Canberra

Senior Lecturer, School of Education, Curtin University

Lecturer in Education, University of Stirling

Associate Dean, Director Student Conduct and Conflict Resolution, University of Florida

Vice-Chancellor's Fellow, The University of Melbourne

Associate Professor, Faculty of Education and Social Work, University of Sydney

Assistant Professor of Secondary Mathematics Education, West Virginia University

Professor of Education, University of Florida

- X (Twitter)

- Unfollow topic Follow topic

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Education scholar Denise Pope has found that too much homework has negative effects on student well-being and behavioral engagement. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

A Stanford researcher found that too much homework can negatively affect kids, especially their lives away from school, where family, friends and activities matter.

“Our findings on the effects of homework challenge the traditional assumption that homework is inherently good,” wrote Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education and a co-author of a study published in the Journal of Experimental Education .

The researchers used survey data to examine perceptions about homework, student well-being and behavioral engagement in a sample of 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities. Along with the survey data, Pope and her colleagues used open-ended answers to explore the students’ views on homework.

Median household income exceeded $90,000 in these communities, and 93 percent of the students went on to college, either two-year or four-year.

Students in these schools average about 3.1 hours of homework each night.

“The findings address how current homework practices in privileged, high-performing schools sustain students’ advantage in competitive climates yet hinder learning, full engagement and well-being,” Pope wrote.

Pope and her colleagues found that too much homework can diminish its effectiveness and even be counterproductive. They cite prior research indicating that homework benefits plateau at about two hours per night, and that 90 minutes to two and a half hours is optimal for high school.

Their study found that too much homework is associated with:

* Greater stress: 56 percent of the students considered homework a primary source of stress, according to the survey data. Forty-three percent viewed tests as a primary stressor, while 33 percent put the pressure to get good grades in that category. Less than 1 percent of the students said homework was not a stressor.

* Reductions in health: In their open-ended answers, many students said their homework load led to sleep deprivation and other health problems. The researchers asked students whether they experienced health issues such as headaches, exhaustion, sleep deprivation, weight loss and stomach problems.

* Less time for friends, family and extracurricular pursuits: Both the survey data and student responses indicate that spending too much time on homework meant that students were “not meeting their developmental needs or cultivating other critical life skills,” according to the researchers. Students were more likely to drop activities, not see friends or family, and not pursue hobbies they enjoy.

A balancing act

The results offer empirical evidence that many students struggle to find balance between homework, extracurricular activities and social time, the researchers said. Many students felt forced or obligated to choose homework over developing other talents or skills.

Also, there was no relationship between the time spent on homework and how much the student enjoyed it. The research quoted students as saying they often do homework they see as “pointless” or “mindless” in order to keep their grades up.

“This kind of busy work, by its very nature, discourages learning and instead promotes doing homework simply to get points,” Pope said.

She said the research calls into question the value of assigning large amounts of homework in high-performing schools. Homework should not be simply assigned as a routine practice, she said.

“Rather, any homework assigned should have a purpose and benefit, and it should be designed to cultivate learning and development,” wrote Pope.

High-performing paradox

In places where students attend high-performing schools, too much homework can reduce their time to foster skills in the area of personal responsibility, the researchers concluded. “Young people are spending more time alone,” they wrote, “which means less time for family and fewer opportunities to engage in their communities.”

Student perspectives

The researchers say that while their open-ended or “self-reporting” methodology to gauge student concerns about homework may have limitations – some might regard it as an opportunity for “typical adolescent complaining” – it was important to learn firsthand what the students believe.

The paper was co-authored by Mollie Galloway from Lewis and Clark College and Jerusha Conner from Villanova University.

Media Contacts

Denise Pope, Stanford Graduate School of Education: (650) 725-7412, [email protected] Clifton B. Parker, Stanford News Service: (650) 725-0224, [email protected]

- Subscribe to BBC Science Focus Magazine

- Previous Issues

- Future tech

- Everyday science

- Planet Earth

- Newsletters

© Getty Images

Should homework be banned?

Social media has sparked into life about whether children should be given homework - should students be freed from this daily chore? Dr Gerald Letendre, a professor of education at Pennsylvania State University, investigates.

We’ve all done it: pretended to leave an essay at home, or stayed up until 2am to finish a piece of coursework we’ve been ignoring for weeks. Homework, for some people, is seen as a chore that’s ‘wrecking kids’ or ‘killing parents’, while others think it is an essential part of a well-rounded education. The problem is far from new: public debates about homework have been raging since at least the early-1900s, and recently spilled over into a Twitter feud between Gary Lineker and Piers Morgan.

Ironically, the conversation surrounding homework often ignores the scientific ‘homework’ that researchers have carried out. Many detailed studies have been conducted, and can guide parents, teachers and administrators to make sensible decisions about how much work should be completed by students outside of the classroom.

So why does homework stir up such strong emotions? One reason is that, by its very nature, it is an intrusion of schoolwork into family life. I carried out a study in 2005, and found that the amount of time that children and adolescents spend in school, from nursery right up to the end of compulsory education, has greatly increased over the last century . This means that more of a child’s time is taken up with education, so family time is reduced. This increases pressure on the boundary between the family and the school.

Plus, the amount of homework that students receive appears to be increasing, especially in the early years when parents are keen for their children to play with friends and spend time with the family.

Finally, success in school has become increasingly important to success in life. Parents can use homework to promote, or exercise control over, their child’s academic trajectory, and hopefully ensure their future educational success. But this often leaves parents conflicted – they want their children to be successful in school, but they don’t want them to be stressed or upset because of an unmanageable workload.

However, the issue isn’t simply down to the opinions of parents, children and their teachers – governments also like to get involved. In the autumn of 2012, French president François Hollande hit world headlines after making a comment about banning homework, ostensibly because it promoted inequality. The Chinese government has also toyed with a ban, because of concerns about excessive academic pressure being put on children.

The problem is, some politicians and national administrators regard regulatory policy in education as a solution for a wide array of social, economic and political issues, perhaps without considering the consequences for students and parents.

Does homework work?

Homework seems to generally have a positive effect for high school students, according to an extensive range of empirical literature. For example, Duke University’s Prof Harris Cooper carried out a meta-analysis using data from US schools, covering a period from 1987 to 2003. He found that homework offered a general beneficial impact on test scores and improvements in attitude, with a greater effect seen in older students. But dig deeper into the issue and a complex set of factors quickly emerges, related to how much homework students do, and exactly how they feel about it.

In 2009, Prof Ulrich Trautwein and his team at the University of Tübingen found that in order to establish whether homework is having any effect, researchers must take into account the differences both between and within classes . For example, a teacher may assign a good deal of homework to a lower-level class, producing an association between more homework and lower levels of achievement. Yet, within the same class, individual students may vary significantly in how much homework improves their baseline performance. Plus, there is the fact that some students are simply more efficient at completing their homework than others, and it becomes quite difficult to pinpoint just what type of homework, and how much of it, will affect overall academic performance.

Over the last century, the amount of time that children and adolescents spend in school has greatly increased

Gender is also a major factor. For example, a study of US high school students carried out by Prof Gary Natriello in the 1980s revealed that girls devote more time to homework than boys, while a follow-up study found that US girls tend to spend more time on mathematics homework than boys. Another study, this time of African-American students in the US, found that eighth grade (ages 13-14) girls were more likely to successfully manage both their tasks and emotions around schoolwork, and were more likely to finish homework.

So why do girls seem to respond more positively to homework? One possible answer proposed by Eunsook Hong of the University of Nevada in 2011 is that teachers tend to rate girls’ habits and attitudes towards work more favourably than boys’. This perception could potentially set up a positive feedback loop between teacher expectations and the children’s capacity for academic work based on gender, resulting in girls outperforming boys. All of this makes it particularly difficult to determine the extent to which homework is helping, though it is clear that simply increasing the time spent on assignments does not directly correspond to a universal increase in learning.

Can homework cause damage?

The lack of empirical data supporting homework in the early years of education, along with an emerging trend to assign more work to this age range, appears to be fuelling parental concerns about potential negative effects. But, aside from anecdotes of increased tension in the household, is there any evidence of this? Can doing too much homework actually damage children?

Evidence suggests extreme amounts of homework can indeed have serious effects on students’ health and well-being. A Chinese study carried out in 2010 found a link between excessive homework and sleep disruption: children who had less homework had better routines and more stable sleep schedules. A Canadian study carried out in 2015 by Isabelle Michaud found that high levels of homework were associated with a greater risk of obesity among boys, if they were already feeling stressed about school in general.

For useful revision guides and video clips to assist with learning, visit BBC Bitesize . This is a free online study resource for UK students from early years up to GCSEs and Scottish Highers.

It is also worth noting that too much homework can create negative effects that may undermine any positives. These negative consequences may not only affect the child, but also could also pile on the stress for the whole family, according to a recent study by Robert Pressman of the New England Centre for Pediatric Psychology. Parents were particularly affected when their perception of their own capacity to assist their children decreased.

What then, is the tipping point, and when does homework simply become too much for parents and children? Guidelines typically suggest that children in the first grade (six years old) should have no more that 10 minutes per night, and that this amount should increase by 10 minutes per school year. However, cultural norms may greatly affect what constitutes too much.

A study of children aged between 8 and 10 in Quebec defined high levels of homework as more than 30 minutes a night, but a study in China of children aged 5 to 11 deemed that two or more hours per night was excessive. It is therefore difficult to create a clear standard for what constitutes as too much homework, because cultural differences, school-related stress, and negative emotions within the family all appear to interact with how homework affects children.

Should we stop setting homework?

In my opinion, even though there are potential risks of negative effects, homework should not be banned. Small amounts, assigned with specific learning goals in mind and with proper parental support, can help to improve students’ performance. While some studies have generally found little evidence that homework has a positive effect on young children overall, a 2008 study by Norwegian researcher Marte Rønning found that even some very young children do receive some benefit. So simply banning homework would mean that any particularly gifted or motivated pupils would not be able to benefit from increased study. However, at the earliest ages, very little homework should be assigned. The decisions about how much and what type are best left to teachers and parents.

As a parent, it is important to clarify what goals your child’s teacher has for homework assignments. Teachers can assign work for different reasons – as an academic drill to foster better study habits, and unfortunately, as a punishment. The goals for each assignment should be made clear, and should encourage positive engagement with academic routines.

Parents should inform the teachers of how long the homework is taking, as teachers often incorrectly estimate the amount of time needed to complete an assignment, and how it is affecting household routines. For young children, positive teacher support and feedback is critical in establishing a student’s positive perception of homework and other academic routines. Teachers and parents need to be vigilant and ensure that homework routines do not start to generate patterns of negative interaction that erode students’ motivation.

Likewise, any positive effects of homework are dependent on several complex interactive factors, including the child’s personal motivation, the type of assignment, parental support and teacher goals. Creating an overarching policy to address every single situation is not realistic, and so homework policies tend to be fixated on the time the homework takes to complete. But rather than focusing on this, everyone would be better off if schools worked on fostering stronger communication between parents, teachers and students, allowing them to respond more sensitively to the child’s emotional and academic needs.

- Five brilliant science books for kids

- Will e-learning replace teachers?

Follow Science Focus on Twitter , Facebook , Instagram and Flipboard

Share this article

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy policy

- Cookies policy

- Code of conduct

- Magazine subscriptions

- Manage preferences

Remote students are more stressed than their peers in the classroom, study shows

As debates rage across the country over whether schools should teach online or in person, students like Sean Vargas-Arcia have experienced the pros and cons of both.

“I’m much happier in person,” said Sean, 16, a junior at Yonkers Middle High School in New York. As Covid-19 rates have fluctuated, he has gone back and forth between online classes and attending in person two days per week.

It’s stressful worrying about contracting the coronavirus at school, said Sean, who has health issues including epilepsy and a grandmother who lives with his family. But his online classes wear him down.

“When I’m at home, fully remote, it’s more like a sluggish feeling,” he said. “I’m usually feeling distressed and tired and I just don’t want anything to do with school anymore.”

There’s no question that the pandemic has been hard on children , whether or not their schools have reopened. A flood of research in recent months has found alarming spikes in depression and anxiety among children and their parents. Multiple studies have found that students — especially those with disabilities and from low-income families — are learning less than they should.

But a new study from NBC News and Challenge Success , a nonprofit affiliated with the Stanford Graduate School of Education, is one of the first to shed light on the differences between students whose classes have been exclusively online and those who’ve been able to attend in person at least one day per week.

All this week, watch “NBC Nightly News with Lester Holt” and the "TODAY" show for more on “Kids Under Pressure," a series examining the impact of the pandemic on children

The survey last fall of more than 10,000 students in 12 U.S. high schools, including Yonkers, found that students who’d spent time in the classroom reported lower rates of stress and worry than their online peers.

While just over half of all students surveyed said they were more stressed about school in 2020 than they had been previously, the issue was more pronounced among remote students. Eighty-four percent of remote students reported exhaustion, headaches, insomnia or other stress-related ailments, compared to 82 percent of students who were in the classroom on some days and 78 percent of students who were in the classroom full time.

Remote students were also slightly less likely to say they had an adult they could go to with a personal problem and slightly more likely to fret about grades than their peers in the classroom. And the remote students did more homework, reporting an average of 90 additional minutes per week, the study found.

“Remote learning — and I don’t think this is a surprise to anyone — is just more challenging,” said Sarah Miles, the director of research and programs at Challenge Success and one of the leaders of the study. “It’s harder for kids to feel connected. It’s harder for teachers, for the adults in the school, to connect and that’s a foundational element. In order for kids to learn, they need to feel safe and connected. Everything else rests on top of that.”

Challenge Success, an education research and school support organization, surveys most students in dozens of schools a year to help teachers and administrators better meet their needs. The 12 schools surveyed last fall, in Arizona, Texas, New York and the Midwest, are demographically similar to the nation in terms of student family income, though not necessarily in terms of race, Miles said.

The debate around reopening U.S. schools has become increasingly fraught, with parents and political leaders including President Joe Biden loudly calling for schools to reopen and teachers in some parts of the country threatening to walk off the job over safety concerns . On Friday, the Biden administration released guidelines for how to safely reopen schools, advising precautions including masks, social distancing and contact tracing.

Miles said the new research doesn't mean that schools should rush to reopen before putting safety protocols in place. Instead, she said, it shows the importance of making sure teachers and staff members feel comfortable returning to the classroom.

“If they don’t feel safe and supported, kids won’t feel safe and supported,” she said.

But, at the same time, she said, the study underscores the damage online learning is doing.

“We need to prioritize getting to a place where everyone feels comfortable going back to school,” Miles said, “because it’s urgent.”

‘A bit of magic’ in the classroom

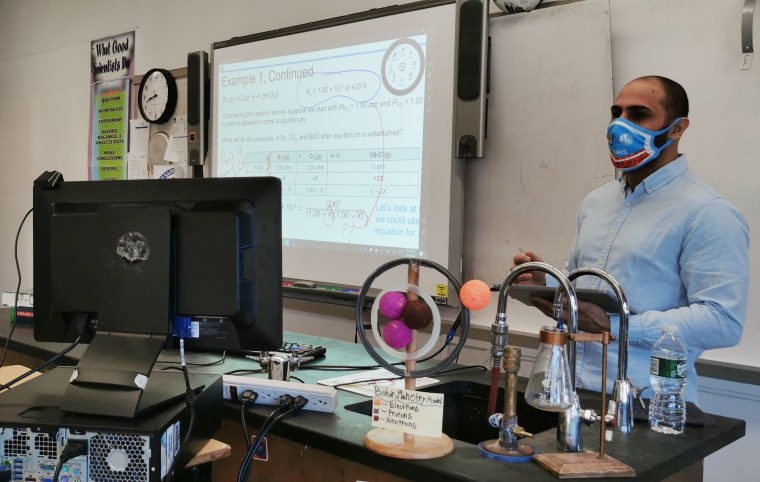

All of Jordan Salhoobi’s chemistry students at Yonkers Middle High School are getting the same lessons at the same time.

The ones wearing masks in his classroom hear the same lectures and see the same demonstrations as students watching the livestream at home. When he writes or draws on his computer tablet, students at home see the same images on their screens that students in the classroom see projected on the wall.

But Salhoobi’s students are not getting the same benefits, he said.

“In the room, you get more eye contact,” he said. “On the screen, oftentimes the kid could be sitting in front of a window. You can’t see them, so it’s hard to make sure they’re attentive.”

While it’s difficult to compare his students’ performance, Salhoobi said his in-person students sometimes stay after class for extra help that online students rarely ask for. Online students seem more reluctant to raise their hands and they often look tired.

“I think that actually coming to school and getting dressed makes kids feel more like they have a purpose in life,” he said.

When Yonkers started offering a hybrid option in October that allows students to attend in person either Monday and Tuesday or Thursday and Friday, most students chose to remain online. Only about a third of students are currently in the hybrid program, a Yonkers district spokeswoman said, leaving many classrooms with just a handful of students.

Full coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

Yonkers principal Jade Sharp said that she hasn’t seen significant differences in grades or test scores between remote and hybrid students, but that she wasn’t surprised to see survey data showing that her remote students are more stressed.

“I feel sorry for our students in this Covid situation,” she said, noting that many of her 1,100 high school students have responsibilities at home such as caring for younger siblings in addition to their schoolwork. Three-quarters come from families the state considers economically disadvantaged, including many from immigrant families. Some have parents who’ve lost jobs. Some lost loved ones to Covid-19. And many are reeling from the social and political tensions of the past year.

The school goes out of its way to support students, Sharp said, limiting instruction to half days on “wellness Wednesdays,” and hosting after-school clubs focused on mental health.

But none of that offers what even a couple of days in the classroom interacting with teachers and peers can do, said Tara O’Sullivan, who teaches U.S. history at Yonkers.

“There’s a bit of magic that can happen in a classroom,” O’Sullivan said. “There’s nothing like the rapport and energy of kids working with each other, the sort of flow of conversation and bouncing off ideas that’s obviously present in person.”

Headaches and eye strain

Tanya Palmer, 16, a Yonkers junior, has managed to keep up her grades this year — but only because she puts in extra time to make up for what she’s missing in class.

“I don't feel like I'm really learning much,” said Tanya, who chose to stay remote to protect her 75-year-old grandfather, who lives with her family. “There’s a lot of teaching myself things.”

Things have gotten better since the beginning of the school year when technical glitches were more common and teachers were still adjusting. But when she finishes her five hours of online classes each day, she’s often staring down hours of extra research and reading to actually learn the material.

“I get a lot of headaches and eye strain,” she said. “My eyes are so dry, and I get back pain, too.”

The NBC News and Challenge Success study found that online-only students in Yonkers reported an average of 31 minutes more homework on the weekend and 70 more minutes during the week than their classmates in the hybrid program. Though most students were not getting anywhere close to the nine hours of sleep recommended for adolescents, reporting just over six hours, the hybrid students reported sleeping an average of about 10 minutes more per night than their online peers.

“It’s 10 o’clock and I see her on the computer,” said Tanya Gonzalez, Tanya’s mother. “I get close to her, thinking maybe she’s watching a video, but no, she’s doing classwork.”

Download the NBC News app for full coverage and alerts about the coronavirus outbreak

Sean Vargas-Arcia had more energy when he was in school two days a week, and more ways to understand his coursework, he said, recalling how he struggled last semester to visualize the molecular structure of fatty acids known as lipids until he saw a 3-D model in his biology classroom.

“I was like, ‘Oh, that helps,’ because I could actually see it,” he said.

These days, however, Sean is back to being fully online. So few students returned when the school reopened last month after closing for a few weeks because of higher infection rates that he was the only student in some of his classes. He decided there wasn’t much point, so now he wakes up, walks across his room and sits down in front of a computer from 7:45 a.m. to 1 p.m. without a break. A quirk in his schedule put his lunch hour at the end of the day.

With college applications looming, Sean worries his grades in online classes will suffer, costing him his shot at his first-choice, Brown University, next year.

“There’s a lot of anxiety that surrounds thinking about my future,” he said.

He’s also struggling with isolation from his friends. He used the quiet hours over the summer for reflection and, in September, came out to family and friends as transgender. He announced his name change on social media, but most of his classmates haven’t seen him in person since then.

Everything has been more difficult this year for students at Yonkers, an academically selective school that draws a diverse mix of students — half Latino, 20 percent white, 15 percent Asian, 13 percent Black — from the city of the same name just north of New York City. Sports and after-school programs are largely gone, and school events, like the gala Yonkers traditionally throws in the spring to celebrate the many cultures in the school, have been canceled.

For some students, it’s a small price to pay to keep their families safe, said Emma Maher, 17, a junior who chose the online option because her sister has asthma and her grandmother has a compromised immune system.

“The sacrifice is worth it,” she said, “because I value the health of my family and loved ones.”

But educators worry about the long-term impact on a generation of children who are stressed out, struggling to learn and missing their friends.

“You took away so much from these kids,” said Salhoobi, the chemistry teacher. “You took away sports. You took away interactions. It’s kind of like kids are in jail now when they’re 100 percent online.”

Erin Einhorn is a national reporter for NBC News, based in Detroit.

By providing an email address. I agree to the Terms of Use and acknowledge that I have read the Privacy Policy .

Too much homework?

Who doesn’t remember seemingly endless afternoons on weekdays, or worse, on weekends, spent tied to one’s desk at home laboring over homework?

Or who doesn’t remember rushing through breakfast on a school day to finish an assignment due that day?

For many a student and adult, memories of school are replete with horror stories of many hours spent laboring over homework—including projects and crafts—while daylight slowly dimmed and the sounds of one’s playmates enjoying themselves outside faded with dusk.

Well, for learners today and in the near future, such memories may soon fade into forgetfulness, if some legislators and lobby groups have their way.

For Tutok to Win party list Rep. Sam Verzosa, Filipino students these days are “overworked,” alleging that a child spends as much as 10 hours in school on weekdays. Some years back, global education assessments placed Italian learners as the most overworked, with nine hours spent on homework a week.

A global review reveals, however, that time spent on school assignments does not translate into better grades for students or better results for educational outcomes nationwide. Italy’s ranking in international assessments was relatively low in a 2014 study. While students in South Korea, whose education system ranked number one in the world in the same review, only spend 2.9 hours on homework weekly.

And of course, we all know the dismal ranking of Filipino students in similar international assessments, with learners landing at the bottom, or very near the bottom, of rankings, even when compared to much poorer countries.

It makes sense, then, for Verzosa to propose a “no homework law” that would prevent teachers from giving homework to elementary and high school students during weekends so that the children could “rest and recharge.”

This isn’t the first time that a cap on assignment loads has been attempted. A 2010 Department of Education (DepEd) memorandum circular advised teachers to limit the giving of homework to public elementary school students to a reasonable quantity on weekdays, while no homework is to be given on weekends. At least three bills were in fact filed to institutionalize this for all elementary and high schools across the country.

But in the intervening years, despite efforts to institute a “no homework” policy on weekends, these have remained pending before the House basic education and culture committee.

“The Filipino youth are overworked and yet the Philippines is trailing behind other countries,” Verzosa said in his privilege speech. He cited reports that the average intelligence quotient of Filipinos was 81.64, while the global average IQ was 100. The Philippines ranked 111th out of 199 countries in average IQ.

In addition, said Verzosa, the country has the highest dropout rate among Southeast Asian countries, with lack of interest in school as one of the reasons cited. “This only shows that school is not fun anymore,” he said.

This plays against a background of the “learning losses” that children worldwide experienced as a result of the school lockdowns enforced in the three years of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Philippines, with one of the longest such lockdowns in the world, certainly felt the toll, with “blended learning” proving to be a dismal failure, especially in areas with bad communications infrastructure.

Our educational crisis also takes place amid a history of failed policies that have resulted in our current crisis. A report by the Philippine Business for Education (PBEd), observes that students are “not truly learning but merely progressing” through the school system. The study linked the “unofficial” policy of mass promotion of students to poor learning outcomes.

PBEd executive director Justine Raagas said that there is an apparent misunderstanding among participants about the concept of “No child left behind” which “led to the literal practice of passing students” or promoting them to the next grade level regardless of their competencies. Teachers, it seems, prefer to pass on the responsibility of ensuring a student’s competency to the next grade teacher.

Subscribe to our daily newsletter

Amid these seemingly insurmountable problems besetting the education system, the DepEd and policymakers should make sense of the many well-meaning proposals to address the learning losses and the poor quality of public education. Bills like the no-homework-on-weekends and that which seeks to revise or abolish the K-12 program must be thoroughly discussed, not only by legislators but by the education sector itself, to see if these will really help improve the education of our children or just become additional distractions. It’s about time the DepEd, Congress, and other education stakeholders get their act together and do their own homework.

Subscribe to our newsletter!

Disclaimer: Comments do not represent the views of INQUIRER.net. We reserve the right to exclude comments which are inconsistent with our editorial standards. FULL DISCLAIMER

© copyright 1997-2024 inquirer.net | all rights reserved.

This is an information message

We use cookies to enhance your experience. By continuing, you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more here.

- Essay Editor

Why Homework Is Good for Students: 20 No-Nonsense Reasons

Is homework beneficial in education? It has long been a cornerstone, often sparking debates about its value. Some argue it creates unnecessary stress, while others assert it’s essential for reinforcing in-class learning. Why is homework important? The reality is, that homework is vital for students' personal and academic growth. It not only improves their grasp of the material but also develops crucial skills that extend well beyond the classroom. This review explores 20 reasons why homework is good and why it continues to be a key element of effective education.

Enhances Study Habits

Does homework help students learn? Establishing strong study habits is essential for long-term success. Home assignment plays a key role in enhancing these habits through regular practice. Here are reasons why students should have homework:

- Routine Building: Independent work creates a consistent study routine, helping learners form daily study habits. This consistency is crucial for maintaining progress and avoiding last-minute cramming.

- Time Management: Managing home assignments teaches students to balance academic duties with other activities and personal time.

- Self-Discipline: Finishing assignments requires resisting distractions and staying focused, fostering the self-discipline needed for success in and out of college or school.

- Organization: Home task involves tracking preps, deadlines, and materials, improving students' organizational skills.

These points underscore why homework is good for boosting study habits that lead to academic success. Regular home assignments help learners manage time, stay organized, and build the discipline necessary for their studies.

Facilitates Goal Setting

Setting and achieving goals is vital for student success. Homework assists in this by providing possibilities for setting both short-term and long-term academic objectives. Here’s why is homework beneficial for goal-setting:

- Short-Term Objectives: Homework encourages immediate targets, like finishing assignments by deadlines, and helping students stay focused and motivated.

- Long-Term Aspirations: Over time, preps contribute to broader accomplishments, such as mastering a subject or improving grades, providing direction in their studies.

- Motivation: Completing home tasks boosts motivation by demonstrating results from their effort. Achieving targets reinforces the importance of perseverance.

- Planning: Homework teaches essential planning and prioritization skills, helping learners approach tasks systematically.

These aspects demonstrate the reasons why homework is good for setting and achieving educational targets. Regular preps help students establish clear objectives, plan effectively, and stay motivated.

Improves Concentration

Attention is vital for mastering any subject. Homework offers an opportunity to develop this ability. Here’s why homework is important for boosting attention:

- Increased Focus: Regular assignments require sustained attention, improving mental engagement over time, benefiting both academic and non-academic tasks.

- Better Task Management: Homework teaches managing multiple tasks, enhancing the ability to concentrate on each without becoming overwhelmed.

- Mental Endurance: Completing home tasks builds stamina for longer study sessions and challenging tasks, crucial for advanced studies and career success.

- Attention to Detail: Home assignments promote careful attention to detail, requiring students to follow instructions and ensure accuracy.

These elements show ‘why is homework good for students’. Homework aids students in improving their focus, leading to better academic outcomes. Regular practice through homework improves mental engagement.

Reinforces Perseverance

Perseverance is key to success. Homework significantly contributes to teaching this skill. Here are reasons homework is good in supporting the development of perseverance:

- Problem-Solving: Homework challenges students to tackle difficult problems, fostering perseverance as they approach challenges with determination.

- Resilience: Regular homework helps build resilience against academic challenges, developing mental toughness.

- Persistence: Homework encourages persistence, teaching students to complete tasks despite difficulties, which is crucial for long-term goals.

- Confidence: Completing assignments boosts confidence, motivating students to tackle new challenges with determination.

These reasons highlight ‘Why is homework good for fostering perseverance?’ Engaging with home tasks consistently helps students overcome obstacles and achieve their goals.

Final Consideration

To recap, the motivating reasons for homework extend well beyond the classroom. From improving study habits and mental engagement to fostering goal-setting and perseverance, the advantages are clear. Preps equip students with skills necessary for personal and academic growth. What do you think are the top 10 reasons why students should have homework among the ones we listed? Discuss with your peers. To refine your homework or essays, consider using tools like the AI Essay Detector and College Essay Generator to boost your academic performance.

Related articles

Top 10 use cases for ai writers.

Writing is changing a lot because of AI. But don't worry — AI won't take human writers' jobs. It's a tool that can make our work easier and help us write better. When we use AI along with our own skills, we can create good content faster and better. AI can help with many parts of writing, from coming up with ideas to fixing the final version. Let's look at the top 10 ways how to use AI for content creation and how it can make your writing better. What Is AI Content Writing? AI content writin ...

Paraphrasing vs Plagiarism: Do They Really Differ?

Academic assignments require much knowledge and skill. One of the most important points is rendering and interpreting material one has ever studied. A person should avoid presenting word-for-word plagiarism but express his or her thoughts and ideas as much as possible. However, every fine research is certain to be based on the previous issues, data given, or concepts suggested. And here it's high time to differentiate plagiarism and paraphrasing, to realize its peculiarities and cases of usage. ...

How to Write a Dialogue in an Essay: Useful Tips

A correct usage of dialogues in essays may seem quite difficult at first sight. Still there are special issues, for instance, narrative or descriptive papers, where this literary technique will be a good helper in depicting anyone's character. How to add dialogues to the work? How to format them correctly? Let's discuss all relevant matters to master putting conversation episodes into academic essays. Essay Dialogue: Definition & Purpose A dialogue is a literary technique for presenting a con ...

How To Write Essays Faster Using AI?

Creating various topical texts is an obligatory assignment during studies. For a majority of students, it seems like a real headache. It is quite difficult to write a smooth and complex work, meeting all the professors' requirements. However, thanks to modern technologies there appeared a good way of getting a decent project – using AI to write essays. We'd like to acquaint you with Aithor, an effective tool of this kind, able to perform fine and elaborated texts, and, of course, inspiration, i ...

Plagiarism: 7 Types in Detail

Your professor says that it is necessary to avoid plagiarism when writing a research paper, essay, or any project based on the works of other people, so to say, any reference source. But what does plagiarism mean? What types of it exist? And how to formulate the material to get rid of potential bad consequences while rendering original texts? Today we try to answer these very questions. Plagiarism: Aspect in Brief Plagiarism is considered to be a serious breach, able to spoil your successful ...

Can Plagiarism Be Detected on PDF?

Plagiarism has been a challenge for a long time in writing. It's easy to find information online, which might make some people use it without saying where it came from. But plagiarism isn't just taking someone else's words. Sometimes, we might do it by accident or even use our own old work without mentioning it. When people plagiarize, they can get into serious trouble. They might lose others' trust or even face legal problems. Luckily, we now have tools to detect plagiarism. But what about PDF ...

What Is Self-Plagiarism & How To Avoid It

Have you ever thought about whether using your own work again could be seen as copying? It might seem strange, but self-plagiarism is a real issue in school and work writing. Let's look at what this means and learn how to avoid self-plagiarism so your work stays original and ethical. What is self-plagiarism? Self-plagiarism, also called auto-plagiarism or duplicate plagiarism, happens when a writer uses parts of their old work without saying where it came from. This isn't just about copying w ...

What is Citation and Why Should You Cite the Sources When Writing Content

When we write something for school, work, or just for fun, we often use ideas and facts from other places. This makes us ask: what is a citation in writing? Let's find out what this means and why it's really important when we write. What is Citation? Citation in research refers to the practice of telling your readers where you got your information, ideas, or exact words from. It's like showing them the path to the original information you used in your writing. When you cite something, you us ...

- Infertility

- Miscarriage & Loss

- Pre-Pregnancy Shopping Guides

- Diapering Essentials

- Bedtime & Bathtime

- Baby Clothing

- Health & Safety

- First Trimester

- Second Trimester

- Third Trimester

- Pregnancy Products

- Baby Names By Month

- Popular Baby Names

- Unique Baby Names

- Labor & Delivery

- Birth Stories

- Fourth Trimester

- Parental Leave

- Postpartum Products

- Infant Care Guide

- Healthy Start

- Sleep Guides & Schedules

- Feeding Guides & Schedules

- Milestone Guides

- Learn & Play

- Memorable Moments

- Beauty & Style Shopping Guides

- Meal Planning & Shopping

- Nourishing Little Minds

- Entertaining

- Personal Essays

- Home Shopping Guides

- Work & Motherhood

- Family Finances & Budgeting

- State of Motherhood

- Viral & Trending

- Celebrity News

- Women’s Health

- Children’s Health

- It’s Science

- Mental Health

- Health & Wellness Shopping Guide

- What To Read

- What To Watch

- Fourth of July

- Back to School

- Breastfeeding Awareness

- Single Parenting

- Blended Families

- Community & Friendship

- Marriage & Partnerships

- Grandparents & Extended Families

- Stretch Mark Cream

- Pregnancy Pillows

- Maternity Pajamas

- Maternity Workout Clothes

- Compression Socks

- All Pregnancy Products

- Pikler Triangles

- Toddler Sleep Sacks

- Toddler Scooters

- Water Tables

- All Toddler Products

- Breastmilk Coolers

- Postpartum Pajamas

- Postpartum Underwear

- Postpartum Shapewear

- All Postpartum Products

- Kid Pajamas

- Play Couches

- Kids’ Backpacks

- Kids’ Bikes

- Kids’ Travel Gear

- All Child Products

- Baby Swaddles

- Eco-Friendly Diapers

- Baby Bathtubs

- All Baby Products

- Pregnancy-safe Skincare

- Diaper Bags

- Maternity Jeans

- Matching Family Swimwear

- Mama Necklaces

- All Beauty and Style Products

- All Classes

- Free Classes By Motherly

- Parenting & Family Topics

- Toddler Topics

- TTC & Pregnancy

- Wellness & Fitness

- Please wait..

This mom’s viral video explains why she’s ‘opting out’ of homework for her child

cayleyxox/TikTok

"The only thing that you should be worried about is learning and what time snack time is."

By Christina Marfice September 4, 2024

When you were in school, don’t you wish you could have had the choice to opt out of homework ? One mom is going viral online for choosing to do just that with her son, and it’s creating a lot of conversation online.

An Arizona mom who posts to TikTok as @cayleyxox created the now-viral video, where she announced, “For any parents that might not know this, and I just recently learned this, is that you can actually opt out of homework for your children.”

That’s a little misleading, as we’ll learn later in her story, but for now, here are the details.

@cayleyxox I hope it inspires more parents to do it for their children ❤️ #momsoftiktok ♬ original sound – cayleyxo

“I didn’t know that until recently, and I just sent my son’s kindergarten teacher a cute little email saying, ‘I’m sorry, based on the stress, mental, physical anxiety it’s causing my kid, we are done. We are done opting out for the rest of the year,'” she said.

She then explained what led to that decision.

Related: In a viral TikTok, a ‘Venmo mom’ defends her decision not to volunteer at school events

“On the first week of school … he got this packet. It’s for August. It doesn’t look like it’s all that bad, but it’s about 15 to 20 pages double-sided. You do the math. We have been working on it and trying to work on it to the best of our abilities, and it is causing him so much mental, physical stress,” she said. “This morning I had him sit down. I felt so guilty for this. We were sitting down, I told him, ‘You can’t even watch a show this morning. You can’t do anything. It’s going to be radio silence until you sit here and eat your breakfast and finish at least one or two pages of this. Because you’re way behind.’ This is so much work for him. I started crying. He started crying. It was an emotional mess.”