- Login / Register

- You are here: Reputations

Etienne Louis Boullée (1728-1799)

21 November 2016 By Anthony Vidler Reputations

No amount of careful philology will ever fully explain Boulleé’s extraordinary dream or evocative influence

Boullelarge

Throughout the 20th century, numerous architects whose careers were cut short by the French Revolution have been re-entered one by one into history, their works studied and their reputations restored. But few have had the fortune of Etienne-Louis Boullée, a reluctant architect, with almost no surviving built works and with only drawings to support his claim to fame. Without the notoriety of his younger colleague Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, whose ostentatious tollgates surrounding the Parisian tax-wall were the object of Revolutionary fury, his death in 1799 passed almost unnoticed. And while Ledoux had managed to publish the first volume of his L’Architecture before he died, Boullée’s essay on architecture remained unpublished, and his drawings largely unremarked on by scholars for nearly a century-and-a-half. And yet, since the 1950s his reputation as one of the major and most original figures of the late 18th century has been firmly established as the elder statesman of the radical Enlightenment in architecture, if not of the Modern Movement itself.

‘If he had any reputation in the last years of the Ancien Régime it was as a teacher, supportive of his students ‘like a father’ wrote a biographer at his death’

During his lifetime, his contemporaries agreed, he was, unlike many of his peers, reluctant to promote his career or fame. Indeed, he was a reluctant architect, having been forced to abandon his love of painting by a practical father, and building few domestic commissions before settling for a career in academic administration and teaching. If he had any reputation in the last years of the Ancien Régime it was as a teacher, supportive of his students ‘like a father’ wrote a biographer at his death. He practised architecture with paper projects, beautifully rendered in pencil and wash, and only at the very end of his life, retiring to his country estate from the events of the Revolution, did he prepare them for publication with a text that even then insisted in its epigraph taken from his hero Correggio: ‘I too am a painter.’

Boulledrawings

Source: Bottom left: Photos 12 / Alamy. All others: Bibliothéque Nationale de France

Clockwise from bottom left: project for the chapel of the dead; Tombeau des Spartiates; cenotaph for Sir Isaac Newton

Spanning the years 1784 to 1799, that is, through the last years of the Ancien Régime, the Revolution, the Terror, the Convention, to the rise of Napoleon and his expedition to Egypt, Boullée’s drawn projects display no direct political affiliations with any of the reigning doctrines or parties; rather they espoused a belief in scientific progress symbolised in monumental forms, a generalised Rousseauism derived from the Social Contract , a dedication to celebrate the grandeur of a ‘nation’, and, more often than not, a meditation on the sublime sobriety of death. Yet taken as a collection, as an almost encyclopaedic representation of the necessary institutions for an ideal state, and joined to the preface he wrote at the end of his life, Boullée’s late works may be interpreted as contributing to his underlying vision of an ‘ideal city’.

Like with Ledoux, this vision emerged gradually, and was the direct outcome of an active practice. Eight years older than Ledoux, Boullée left the Ecole des Arts of Jacques-François Blondel in 1746. He was immediately appointed a professor of architecture at the newly established Ecole des Ponts et Chaussées, under its director, the civil engineer Jean-Rodolphe Perronet, a position that, again like Ledoux, gave him access to public commissions, but more importantly, to a new vision of the role of building in the social and economic progress of a state and its territory. While his private commissions included religious buildings, and grands hôtels for a largely philosophic circle, his public works ranged from the construction of the Prison de la Grande Force (later to house Ledoux himself under the Terror), and, beginning in 1781 on his election to the Académie, projects for a new opera house, as well as a series of designs linked to real projects, but set as exercises for his students in the school of the Académie Royale d’Architecture.

In quick succession he produced elaborate schemes for a metropolitan church, or ‘basilica’ (1781-82); a coliseum (1782); a museum (1783); a cenotaph for Newton (1784); a palace (1785); a new reading room for the Royal Library (1784-85); and a project for a new bridge over the Seine (1787). In the late 1780s forced by severe illness – or political acumen during the Terror – to retire to his country house outside Paris, his last designs were accomplished after the Revolution: projects for a monument in celebration of one of the most popular of Revolutionary festivals, that of the ‘Fête-Dieu’, or Supreme Being; a monument to ‘public recognition’; a palace of justice, a national palace (1792) and a municipal palace (1792).

Étienne-Louis Boullée

Hôtel Alexandre or Hôtel Soult, rue de la Ville l’Évêque, Paris, 1763-66, Hôtel de Brunoy, 1774-79, Metropolitan cathedral, Paris (unbuilt), 1782 Cenotaph for Isaac Newton (unbuilt), 1784

‘Yes, I believe that our buildings, above all our public buildings, should be in some sense poems. The images they offer our senses should arouse in us sentiments corresponding to the purpose for which these buildings are intended’

Life lessons

He shunned frivolous ornamentation, favouring the orders of Greek and Roman precedent, combining classic elements at a monumental scale for heightened dramatic effect. Regularity, symmetry and variety together were paramount, resulting in proportion, which he saw as ‘one of the chief beauties of architecture’

During the excesses of the Terror he expanded his oeuvre with designs for domestic architecture, ‘private architecture’, as opposed to the ‘grand genre’ of public architecture. He was open in his hatred of Robespierre’s Committee of Public Safety, calling the agents of the Terror, ‘perverse beings, tigers lusting for blood’ who wanted nothing but to destroy the ‘arts, sciences, and everything that honours the human spirit’. In silent protest, his ‘reconstruction’ of the Tower of Babel, based on Athanasius Kircher’s Turris Babel , took the form of a pure cone on a cubic base, with a trail of figures winding in a spiral, hand in hand to the top, a symbol of hope for the restitution of a common language and a unified people.

Finally, undated, but no doubt implicitly condemning similar excesses, were a series of extraordinary designs for funerary monuments, cenotaphs and cemeteries, in the form of pyramids, cones and temples, experiments in what he named as new genres of architecture: ‘buried’ architecture and an ‘architecture of shadows’ to be formed out of deep recesses cut in a stone that reflected no light.

Forgotten for most of the 19th century, he was rediscovered by the art historian Emil Kaufmann in the late 1920s. For Kaufmann, Boullée represented the fulfilment of the French and German Enlightenment in architecture. The pure geometries displayed in his projects for national institutions (cubes), monuments dedicated to Newton and Nature (spheres), funerary temples (pyramids) and lighthouses (cones), resonated with Kaufmann’s vision of a movement dedicated to abstract reasoning and individual autonomy. It was left to Helen Rosenau, another exile, to publish the first transcription and translation of his Architecture. Essay on Art in 1953.

Boullecathedral

Source: RIBA collections

Project for a metropolitan cathedral in the form of a Greek cross with a domed centre

It was this message of an ‘autonomous architecture that architects seized on in the postwar period: Philip Johnson cited his Von Ledoux as a source for his house at New Canaan; Aldo Rossi held him up as an example of a new typology. In the field of popular culture, Boullée was rapidly assimilated into the general excitement over ‘utopian’ architecture in the ’60s and ’70s as his Cenotaph for Newton became the ubiquitous poster-image for the Whole Earth and Spaceship Earth movements – a fitting destiny for an architect who had drawn up his spherical design after witnessing the first manned balloon flight over Paris.

That more recent historians have tried to demolish his claim to originality, prescient ‘modernity’ and theoretical radicalism is less an indictment of Kaufmann, and more a result of the shift to a historiography that refuses grand claims. But no amount of careful philology will ever fully explain his extraordinary dream world nor deny his evocative influence over generations of late-20th-century architects.

Illustration by Josephin Ritschel

November 2016

Since 1896, The Architectural Review has scoured the globe for architecture that challenges and inspires. Buildings old and new are chosen as prisms through which arguments and broader narratives are constructed. In their fearless storytelling, independent critical voices explore the forces that shape the homes, cities and places we inhabit.

Join the conversation online

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- What is the weather like in Paris?

- What is the landscape of Paris?

- What was education like in ancient Athens?

- How does social class affect education attainment?

- When did education become compulsory?

Étienne-Louis Boullée

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- The J. Paul Getty Museum - Etienne-Louis Boullée

Étienne-Louis Boullée (born February 12, 1728, Paris , France—died February 6, 1799, Paris) was a French visionary architect, theorist, and teacher.

Boullée wanted originally to be a painter, but, following the wishes of his father, he turned to architecture . He studied with J.-F. Blondel and Germain Boffrand and with J.-L. Legeay and had opened his own studio by the age of 19. He designed several Parisian city mansions in the 1760s and ’70s, notably the Hôtel de Brunoy (1774–79). Despite the innovative Neoclassicism of his executed works, Boullée achieved a truly lasting influence as a teacher and theorist. Through his atelier passed such masters as Alexandre-Théodore Brongniart, Jean-Franƈois-Thérèse Chalgrin , Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand, and Louis-Michel Thibault. In all, he taught for more than 50 years.

In his important theoretical designs for public monuments, Boullée sought to inspire lofty sentiments in the viewer by architectural forms suggesting the sublimity, immensity, and awesomeness of the natural world, as well as the divine intelligence underlying its creation. At the same time, he was strongly influenced by the indiscriminate enthusiasm for antiquity, and especially Egyptian monuments, felt by his contemporaries.

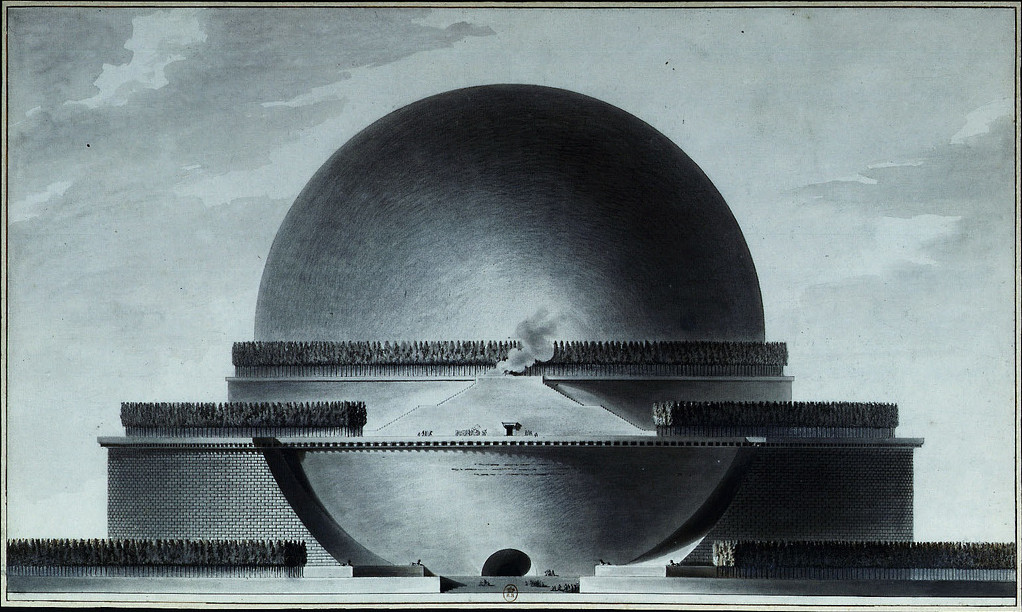

The distinguishing aspect of Boullée’s mature work is his abstraction of the geometric forms suggested by ancient works into a new concept of monumental building that would possess the calm, ideal beauty of classical architecture while also having considerable expressive power. In his famous essay La Théorie des corps, Boullée investigated the properties of geometric forms and their effect on the senses, attributing “innate” symbolic qualities to the cube, pyramid, cylinder, and sphere, the last regarded as an ideal form. In a series of projects for public monuments, culminating in the design (1784) for an immense sphere that would serve as a cenotaph honouring the British physicist Isaac Newton, Boullée gave imaginary form to his theories. The interior of the cenotaph was to be a hollow globe representing the universe.

To bring geometric forms to life, Boullée depended on striking and original effects of light and shadow. He also emphasized the potential for mystery in building, often burying part of a structure. This “poetic” approach to architecture, in some ways prefiguring the 19th-century Romantic movement , may also be seen in Boullée’s extensive use of symbolism. For example, his Palais Municipal rests on four pedestal-like guardhouses, demonstrating that society is supported by law.

Boullée’s emphasis on the psychology of the viewer is a principal theme of his Architecture, essai sur l’art, not published until the 20th century. He has been criticized as a megalomaniac, because of his tendency toward grandiose proposals, but these should be regarded simply as visionary schemes rather than as practical projects. In his desire to create a unique, original architecture appropriate to an ideal new social order, Boullée anticipated similar concerns in 20th-century architecture.

- Hispanoamérica

- Work at ArchDaily

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Memorial Center

AD Classics: Cenotaph for Newton / Etienne-Louis Boullée

- Written by Michelle Miller

This article was originally published on September 10, 2014. To read the stories behind other celebrated architecture projects, visit our AD Classics section. Minuscule clusters of visitors ascend a monumental stairway at the base of a spherical monument rising higher than the Great Pyramid of Giza. An arc of waning sunlight catches a small portion of the sphere, leaving the excavated entry portal and much of the mass in deep shadow. Bringing together the emotional affects of romanticism, the severe rationality of neoclassicism and grandeur of antiquity, Etienne-Louis Boullée’s sublime vision for a cenotaph honoring Sir Isaac Newton is both emblematic of the particular historical precipice and an artistic feat that foreshadowed the modern conception of architectural design. Rendered through a series of ink and wash drawings, the memorial was one of numerous provocative designs he created at the end of the eighteenth century and included in his treatise, Architecture, essai sur l’art . The cenotaph is a poetic homage to scientist Sir Isaac Newton who 150 years after his death had become a revered symbol of Enlightenment ideals.

Beyond representing his individual creative genius, Boullée’s approach to design signaled the schism of architecture as a pure art from the science of building. He rejected the Vitruvian notion of architecture as the art of building, writing “In order to execute, it is first necessary to conceive… It is this product of the mind, this process of creation, that constitutes architecture…” (1). The purpose of design is to envision, to inspire, to make manifest a conceptual idea though spatial forms. Boullee’s search was for an immutable and totalizing architecture.

Paris during Boullée’s lifetime (1728-1799) was the cultural center of the world as well as a nexus great transformation. Pre-Haussmanization streets were the breeding ground of class strife as poor crops and costly wars led to financial crisis. Enlightenment ideals, particularly notions of popular sovereignty and inalienable rights, influenced the rise of malcontent and eventual revolution (2).

Although Boullée completed a number of small-scale built commissions for private and religious patrons, he was most influential during his lifetime in academic roles at the École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées and the Académie Royale d'Architecture. Boullée rejected the perceived frivolity of sumptuous Rococo design in favor of the rigid orders of the Greeks and Romans. Driven by his search for pure forms derived from nature, he looked back into history to the monumental forms of cultures that predated the Greeks. Transcending mere adulation of historical precedents, Boullée remixed classic elements at a scale and level of drama previously unachieved.

For Boullée the sphere represented perfection and majesty, creating soft gradations of light across its curved surface and having an “immeasurable hold over our senses” (3). For Newton’s cenotaph a 500 ft diameter sphere is embedded within a three-tiered cylindrical base, giving the impression of a buried volume. Boullée smartly completes the figure of the sphere with a flanking pair of curved ramps.

A single grand staircase leads up to a round plinth. The drawings privilege impact and atmosphere over legibility of the layout, for example showing a small exterior door on the second level above a band of crenellation yet illustrating no means of access. Narrow flanking stairs provide an exterior connection between the second and uppermost terrace. Closely spaced cypress trees, associated with mourning in Greek and Roman cultures, circumscribe each level. The spherical entry portal at the lower level gives way to a dark, long tunnel that runs below the central volume. Rising up as it approaches the center, a final run of stairs brings visitors into a cavernous void. Here at the center of gravity lies a sarcophagus for Newton, the sole indication of human scale in the interior.

Boullée creates an interior world that inverts exterior lighting conditions. At night, light radiates from an oversize luminaire suspended at the center point of the sphere. Vaguely celestial in form, its light spills through the long the entry tunnels. During the day, a black starlit night blankets the interior. Points of light penetrate the thick shell through narrow punctures whose arrangement corresponds with locations of planets and constellations. A seemingly inaccessible corridor with a quarter-circle section rings the perimeter.

The sections begin to suggest a negotiation of forces, as the dome appears to attenuate or hollow out at the top and thicken towards the supports. The bare walls and lack of ornament create a sombre impression. Changes in tone and fog-like elements bolster the sense of mystery.

Although unbuilt, Boullée’s drawings were engraved and widely circulated. His treatise, bequeathed to the Bibliotèque National de France, was not published until the twentieth century. In The Art of Architectural Drawing: Imagination and Technique , Thomas Wells Schaller calls the cenotaph an “astounding piece” that is “perfectly symptomatic of the age as much as it is of the man” (4). Considered along with Claude Nicholas Ledoux and Jean-Jaques Lequeu the work of Boullée and his contemporaries influenced the work at the École des Beaux-Arts during the mid and latter nineteenth century. His works still inspire designers. For example, in 1980 Lebbeus Woods designed a cenotaph for Einstein, inspired by the Cenotaph for Newton.

Check out an English language translation of Boullee’s thoughts on the architect as artist, nature, and additional projects here .

- Etienne-Louis Boullée. Architecture, Essay on Art. Edited and annotated by Helen Rosenau. Translated by Sheila da Vallée. 82.

- http://www.history.com/topics/french-revolution

- Boullée, 86

- Schaller, 160

Main Sources

Kaufmann, Emil. “Three Revolutionary Architects, Boullée, Ledoux, and Lequeu,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, New Series, 42 No. 3 (1952), 431-564

Rosenau, Helen. Boullée’s Treatise on Architecture. London: Alec Tiranti Ltd., 1953.

Pérouse de Montclos, Jean-Marie. Etienne-Louis Boullée (1728-1799): Theoretician of Revolutionary Architecture. New York: George Braziller, 1974.

Boullée, Etienne-Louis. Architecture, Essay on Art. Edited and annotated by Helen Rosenau. Translated by Sheila da Vallée. Accessed at http://designspeculum.com/Historyweb/boulleetreatise.pdf

Schaller, Thomas Wells. The Art of Architectural Drawing: Imagination and Technique. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1997.

- Sustainability

想阅读文章的中文版本吗?

AD 经典:牛顿纪念堂 / Etienne-Louis Boullée

You've started following your first account, did you know.

You'll now receive updates based on what you follow! Personalize your stream and start following your favorite authors, offices and users.

A Cenotaph for Newton: The Poetry of Public Spaces, the Architecture of Shadow, and How Trees Inspired the World’s First Planetarium Design

By maria popova.

Nineteen years after the publication of Isaac Newton’s epoch-making Principia — in England, in Latin — the prodigy mathematician Émilie du Châtelet set out to translate his ideas into her native French, making them more comprehensible in the process. Her more-than-translation — which includes several of her mathematical corrections and clarifications of Newton’s imprecisions, and which remains the only comprehensive edition in French to this day — popularized his ideas in France and, from this epicenter of the Enlightenment, spread them centripetally throughout the rest of the Continent, rendering Newton himself an emblem of the Enlightenment the sweep of which he never lived to see.

Not long after Du Châtelet’s untimely death, her legacy reached one of her most gifted compatriots — the visionary architect Étienne-Louis Boullée (February 12, 1728–February 4, 1799), who fell under Newton’s spell. Determined to honor Newton with a worthy cenotaph — a memorial tomb for a person buried elsewhere — he designed a sphere 500 feet in diameter, taller than the Pyramids of Giza, nested into a colossal pedestal and encircled by hundreds of cypress trees, giving it the transfixing illusion of being both half-buried into the Earth and hovering unmoored from gravity. It was also, in essence, the world’s first domed planetarium design.

The cenotaph was a touching gesture in the first place — a Frenchman honoring a genius born of and interred in England, a nation with which Boullée’s own had been in near-ceaseless war for centuries, with those tensions at an all-time high at the time of his design, thanks to the American Revolutionary War. Doubly touching was his choice of a sphere: One of Newton’s most revolutionary contributions — the mathematical inference that because gravity is weaker at the equator, the shape of the Earth must be spherical — had defied France’s greatest son, René Descartes, who maintained that the Earth was egg-shaped. When Boullée was still a boy, a young Frenchman — Émilie du Châtelet’s mathematics tutor — had joined a perilous Arctic expedition to prove Newton correct. Two centuries later, in the wake of the world’s grimmest war yet, a queer Quaker Englishman would do the same , risking his life to defend the epoch-making theory of a German Jew — the theory of relativity that ultimately subverted Newton. Another world war later, Einstein himself would appeal to what he called “the common language of science” — that truth-seeking contact with nature and reality that transcends all borders and all nationalisms, the impulse that animated Boullée’s bold homage to Newton.

While governed by the credo that “our buildings — and our public buildings in particular — should be to some extent poems,” Boullée also believed that science could magnify the poetry of public spaces, which must at bottom reflect the principles of the grand designer: Nature. A century before the teenage Virginia Woolf wrote that “all the Arts… imitate as far as they can the one great truth that all can see,” Boullée insisted:

No idea exists that does not derive from nature… It is impossible to create architectural imagery without a profound knowledge of nature: the Poetry of architecture lies in natural effects. That is what makes architecture an art and that art sublime.

Architecture in the modern sense was then a young art, because the art-science of perspective was so novel . Newton’s optics, derived directly from the laws of nature, had revolutionized it all. Boullée came to define architecture as “the art of creating perspectives by the arrangement of volumes,” but a highly poetic art:

The real talent of an architect lies in incorporating in his work the sublime attraction of Poetry.

The poetry of architecture, he argued, resides in using perspective and light in such a way that “our senses are reminded of nature.” He interpreted the laws of nature, as clarified by Newton’s optics and mathematics, to intimate that no shape embodies this serenade to the senses with greater power and precision than the sphere:

A sphere is, in all respects, the image of perfection. It combines strict symmetry with the most perfect regularity and the greatest possible variety; its form is developed to the fullest extent and is the simplest that exists; its shape is outlined by the most agreeable contour and, finally, the light effects that it produces are so beautifully graduated that they could not possibly be softer, more agreeable or more varied. These unique advantages, which the sphere derives from nature, have an immeasurable hold over our senses.

And so Boullée predicated his cenotaph for Newton on an enormous sphere that would convey his ultimate intent for the temple — to arouse in the visitor’s soul “feelings in keeping with religious ceremonies,” a sense of grandeur leaving them “moved by such an excess of sensibility… that all the faculties of our soul are disturbed to such an extent that we feel it is departing from our body” — an effect always best achieved not by an enormity of sheer size and space but by a considered contrast of scales. No building, he observed, “calls for the Poetry of architecture” more than a memorial to the dead. Believing that architecture, like all art, should ultimately serve to enlarge our sense of aliveness, and that we are never more alive than when we are rooted in our creaturely senses, Boullée insisted that the key to this sense of grandeur lies in applying the principles of nature’s mathematics with poetic subtlety — the principles laid bare in the Principia , the principles that “derive from order, the symbol of wisdom.” He wrote:

Symmetry… is what results from the order that extends in every direction and multiplies them at our glance until we can no longer count them. By extending the sweep of an avenue so that its end is out of sight, the laws of optics and the effects of perspective given an impression of immensity; at each step, the objects appear in a new guise and our pleasure is renewed by a succession of different vistas. Finally, by some miracle which in fact is the result of our own movement but which we attribute to the objects around us, the latter seem to move with us, as if we had imparted Life to them.

But my favorite part of the story is that Boullée found his formative inspiration, not only for the Newton cenotaph and but for his entire creative philosophy, in an unusual encounter with trees — those profoundest of teachers .

One evening, heavy with grief, Boullée went for a walk along the edge of a forest. Under the moonlight, he noticed his shadow. He had seen his shadow a thousand times before, but the peculiar lens of his psychic state rendered it entirely new — a living artwork of “extreme melancholy.” Looking around, he saw the shadows of the trees in this new light, too, etching onto the ground the profound drama of life. The entire scene was suddenly awash in “all that is sombre in nature.” He had seen the state of his soul mirrored back by the natural world, as we so often do in those rawest moments when we are stripped to the base of our being, grounded into our creaturely senses.

This was the moment of Boullée’s artistic awakening — that moment of revelation when, as Virginia Woolf wrote in her exquisite account of her own artistic awakening , something lifts “the cotton wool of daily life” and we see the familiar world afresh. Boullée recounted:

The mass of objects stood out in black against the extreme wanness of the light. Nature offered itself to my gaze in mourning. I was struck by the sensations I was experiencing and immediately began to wonder how to apply this, especially to architecture. I tried to find a composition made up of the effect of shadows. To achieve this, I imagined the light (as I had observed it in nature) giving back to me all that my imagination could think of. That was how I proceeded when I was seeking to discover this new type of architecture.

He called this new architecture “the architecture of shadow.” His vision for Newton’s cenotaph was its grand testament:

I attempted to create the greatest of all effects, that of immensity; for that is what gives us lofty thoughts as we contemplate the Creator and give us celestial sensations.

He attempted, more than that, to honor Newton on his own terms, by the essence of his genius:

O Newton! With the range of your intelligence and the sublime nature of your Genius, you have defined the shape of the earth; I have conceived the idea of enveloping you with your discovery… your own self. How can I find outside you anything worthy of you?

In a further homage to Newton’s legacy, with Boullée regarded as a “divine system” of laws, he chose to suspend a sole spherical lamp over the tomb as the only decoration in the entire monument — anything else, he felt, would be “committing sacrilege.” The contrast of scales — the smaller sphere of the lamp inside the enormous sphere of the building — would dramatize the contrast of light and shadow, just as the moonlight had done that fateful night of artistic revelation by the trees. This would give the visitor the sense that they are “as if by magic floating in the air, borne in the wake of images in the immensity of space.” Boullée considered the play of light the vital element in this enchantment:

It is light that produces impressions which arouse in us various contradictory sensations depending on whether they are brilliant or sombre. If I could manage to diffuse in my temple magnificent light effects I would fill the onlooker with joy; but if, on the contrary, my temple had only sombre effects, I would fill him with sadness. If I could avoid direct light and arrange for its presence without the onlooker being aware of its source, the ensuing effect of mysterious daylight would produce inconceivable impression and, in a sense, a truly enchanting magic quality.

At a time long before readily available electric light and light-projection, he leaned on Newton’s optics to envision something that was part Stonehenge and part Hayden Planetarium. A century and a half before the first modern planetarium dome, Boullée dotted the black interior of his dome with an intricate arrangement of tiny holes reflecting the positions of the constellations and the planets, streaming in daylight to create an enchanting nightscape inside. But unlike the modern counterpart, Boullée’s was a reversible planetarium — at night, the sole spherical light would irradiate the tiny holes from the other direction, making the dome appear as a self-contained universe if viewed from above. This, lest we forget, was the golden age of aeronautics, when hot-air balloons first defied gravity to lift the human animal into the sky.

Too visionary for its era, the cenotaph was never built, but Boullée’s ink-and-wash drawings circulated widely in the final decade of his life, eliciting both gasping admiration and merciless derision — the fate of the true visionary. With the publication of his impassioned and insightful writings nearly two centuries after his death, translated by Helen Rosenau, his vision went on to inspire generations of modern artists and architects with a new way of thinking about the poetry of public spaces and the relationship between nature and human creativity.

In a sentiment evocative of another pioneer’s lamentation — Harriet Hosmer’s astute remark that “if one knew but one-half the difficulties an artist has to surmount… the public would be less ready to censure him for his shortcomings or slow advancement” — Boullée wrote of his critics:

No one is more exacting than a man who is not conversant with a given art for he is unable to imagine all the difficulties the artist has to overcome.

His ultimate satisfaction was not the reception or execution of his designs, but the inexhaustible source of their inspiration — the elemental wellspring of the creative impulse behind all art and all science, that richest and readiest reward of our aliveness:

The artist… is always making discoveries and spends his life observing nature.

— Published March 18, 2021 — https://www.themarginalian.org/2021/03/18/etienne-louis-boullee-newton-cenotaph/ —

www.themarginalian.org

PRINT ARTICLE

Email article, filed under, architecture art culture isaac newton science, view full site.

The Marginalian participates in the Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate programs, designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to books. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book from a link here, I receive a small percentage of its price, which goes straight back into my own colossal biblioexpenses. Privacy policy . (TLDR: You're safe — there are no nefarious "third parties" lurking on my watch or shedding crumbs of the "cookies" the rest of the internet uses.)

(Stanford users can avoid this Captcha by logging in.)

- Send to text email RefWorks EndNote printer

Boullee & visionary architecture : including Boulee's Architecture, essay on art

Available online, at the library.

Art & Architecture Library (Bowes)

| Call number | Note | Status |

|---|---|---|

| NA1053.B69.R6 F | Unknown |

More options

- Find it at other libraries via WorldCat

- Contributors

Description

Creators/contributors, contents/summary, bibliographic information, browse related items.

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

- Facebook Icon

- Twitter Icon

The Search for a Revolutionary Architecture

- Back Issues

“Town & Country,” our summer issue, is out now. Subscribe to our print edition today.

After the French Revolution, the architect Étienne-Louis Boullée produced wildly ambitious building designs that were never realized. His ideas influenced both the Right and the Left — and raised the question of whether a revolutionary architecture is possible.

A sketch of architect Étienne-Louis Boullée's plans for Cenotaph for Isaac Newton, 1784. (Wikimedia Commons)

Étienne-Louis Boullée, born in Paris in 1728, is remembered as one of the greatest architects of all time, even though the majority of his most iconic designs were never actually constructed. Steeped in the neoclassical style, which emerged in Rome but matured in France in the years leading up to the French Revolution, he began teaching at the prestigious École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées when he was only nineteen years old. His income secured through teaching, Boullée was able to devote himself to theoretical questions about the nature and purpose of architecture, questions working architects — bound by spatial and financial limitations, not to mention the tastes of their clients — could seldom afford to ask.

Grand Designs

Boullée grew up in a time that saw extensive debate over the relationship between architecture and other art forms, with some wondering if it ought to be considered an art at all. In his 1746 treatise The Fine Arts Reduced to a Single Principle ( Les Beaux-Arts réduits à un même principe ), the philosopher Charles Batteux argued that the imitation of “la belle nature” was the object of all artists except the architect. The primary function of a building, Batteaux argued, was not to evoke an emotion or convey an idea but to provide a service. Functionally, architecture was more akin to a bed or a couch than a painting or a poem.

Boullée disagreed. In his essay Architecture, Essay on Art ( Essai sur l’art ), which remained unpublished until 1953, he imagines what the art of architecture could accomplish if its practitioners consider not only the function of a building but its cultural significance. “To give a building character,” his essay reads, “is to make judicial use of every means of producing no other sensation than those related to the subject.” Funerary monuments, in addition to housing the dead, should induce feelings of “extreme sorrow,” something Boullée’s designs achieve via their use of light-absorbent materials, shadows, and bare walls, creating “an architectural skeleton” similar to the skeleton of a tree in midwinter. His source of inspiration was the Egyptian pyramids, which “conjure up the melancholy image of arid mountains and immutability.”

Tombs of noteworthy individuals Boullée burdened with an additional task: to inspire respect for and celebrate the achievements of those buried inside them. His hypothetical Cenotaph for Isaac Newton, who died a year before Boullée’s own birth, is shaped like an enormous sphere because the late mathematician’s law of gravity “defined the shape of the earth.” Inside, holes in the ceiling would, in broad light, create the illusion of a night sky.

Although images of Boullée’s architecture frequently surface online, the theory behind his fantastical designs — and its relevance to the French Revolution — remains unexplored. This is puzzling, as many of the designs discussed in Essay on Art are dedicated to revolutionary ideas and institutions. Take, for example, his thoughts on the Cult of the Supreme Being. Established by the lawyer-cum-revolutionary Maximilian de Robespierre in 1794, the cult, revolving around an unnamed god of rationality, was once intended to replace Roman Catholicism as the official religion of the French Republic.

Like Newton’s Cenotaph, Boullée felt that temples built for the divinity had to inspire “astonishment and wonder.” This could be accomplished with size, which “has such power over our senses” that even a deadly volcano possesses a subliminal beauty. Complementing size was light, which, when originating from a source unknown to the onlooker, would emulate the grace of the godhead itself.

Of the numerous palaces mentioned in Boullée’s essay, only one was intended for a sovereign. The others are dedicated to republican ideals such as justice, the nation, and the municipality. He designed each palace to inspire reverence for its subject. The Palace of Justice, containing the parliamentary courts, excise boards, and audit offices, rests atop a small prison — a “metaphorical image of Vice overwhelmed by the weight of Justice.”

The National Palace, more of a symbol of the strength and unity of the French Republic than a functional administrative building, would have used giant tablets of the constitutional laws as walls along with, at their base, rows of figures representing the number of republican provinces.

The Municipal Palace contained the magistrates of Paris’s districts. Designed in 1792, when Boullée was sixty-four, it would have featured large entrances and connections between galleries to signal its accessibility to all. Notably, each of these palace designs was endowed with a sense of majesty hitherto reserved for monarchs.

Boullée’s architectural style matches what Victor Hugo defined as the French Revolution’s own artistic style in his 1874 novel Ninety-Three , with “hard rectilinear angles, cold and cutting as steel . . . something like Boucher guillotined by David.” Boullée’s designs certainly match the tone of French painting and architecture produced in Year II (roughly 1793, according to the French Republican calendar), which Anthony Vidler, a professor of architecture at Cooper Union in New York, describes as a “stern, stripped, almost abstracted form of neo-Classicism.”

More recent assessments situate Boullée in the framework of the French Enlightenment as a whole rather than the French Revolution in particular, arguing that he wasn’t influenced by the latter so much as he was an influence on it. The shift from decorative baroque and rococo to austere neoclassicism far predated the storming of the Bastille, even if both processes originated from the same socioeconomic discontents. Boullée’s revolutionary aura derived not from political action but creative introspection, from the perceived importance of connecting form to function.

Architects of Revolution

Scholars have speculated that Boullée’s designs were never constructed due to doubts over his loyalty following the Revolution. In this case, his promise that the concept for the Palace of the Sovereign, created before Louis XVI’s execution in 1793, “could be adapted to other monuments not destined to be a Sovereign’s residence,” failed to convince his fellow citoyens that he was on their side and not — as some claimed — that of the royalists. Still, even if Boullée himself was indeed ostracized during this time, his architectural vision — which adapted the visual language of the ancien régime for the young republic — survived.

While aestheticians argued about the artistic merit of architecture, revolutionaries questioned its political relevance. On the eve of the French Revolution, public perception of architects and architecture — their place in the old world as well as the new one — was largely negative. Architecture, specifically in the form of large, intimidating buildings, was a physical manifestation of monarchic order. By this reasoning, dismantling the latter necessarily involved destroying the former, as evidenced by the storming and subsequent demolition of the Bastille, as well as the destruction or partial destruction of other structures in and around Paris.

Not all revolutionaries participated in this iconoclasm, however. Henri Jean-Baptiste Grégoire, a priest, campaigned for the protection of architecture dated to the “epoch of feudalism” — not because of its artistic or historic value but because, if left intact in “a kind of perpetual pillory,” it would preserve the face of tyranny as a warning for future generations.

Through his Essay on Art , Boullée helped shape a new, democratic architecture to replace its aristocratic predecessor. This democratic architecture did more than glorify the revolutionary cause; it envisioned what a civilization organized along the lines of Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité could look like. Boullée’s Coliseum, a venue for national holidays and festivals based on its ancient Roman counterpart, would have been able to seat three hundred thousand people — half of the capital’s population at the time.

Under the monarchy, celebrations were often held at the Hôtel de Ville, a space “so restricted that there could hardly have been room for the carriages of the King and all his retinue.” For Boullée, public events only made sense if they took place in a venue large enough to accommodate everyone. His design includes covers sheltering people from both rain and sun, and a large number of broad staircases to ensure everyone could escape in case of an emergency.

Boullée showed similar concern for safety when designing theaters, which in his time habitually caught fire, causing countless deaths and injuries. Noting audiences could not enjoy themselves if part of them feared for their lives, Boullée designed his theaters using stone. The only flammable element, a podium made from wood, would be constructed above a water tank and submerged if set ablaze. Like the Coliseum, Boullée’s theaters had numerous spacious exits to allow for speedy evacuation.

Boullée’s impact on revolutionary architecture extends far beyond France. The scale and scope of his designs are echoed in the unrealized structures of other modernist revolutions on both the Left and the fascist far-right: the Monument to the Third International (also known as Tatlin’s Tower) and the Palace of the Soviets in Russia, but also in the Volkshalle of Nazi Germany. Conceived when the regimes they venerated were in their early years — Vladimir Tatlin’s design for Tatlin’s Tower was first unveiled in 1920, while Adolf Hitler sketched the Volkshalle sometime after his visit to Rome in 1938 — these overly ambitious construction projects are a reflection of a modernist zeal that was capable of taking protean forms.

But this same ambition also heralds the inevitable downfall of such movements, and today the impossibly large size typifying the work of Boullée and his devotees — a size that renders the individual human insect-like — is more often interpreted as dystopian than revolutionary.

Boullée’s influence on the visual culture of twentieth-century totalitarian regimes does not complicate his legacy as a revolutionary architect. On the contrary, the interest and resources both communist and fascist regimes have devoted to their respective architectural projects only reaffirms his at the time ridiculed belief that architecture’s power extended beyond functionality, illustrating ideas, evoking powerful emotions, and channeling those emotions into a political cause — reactionary or progressive. Boullée’s force cannot be stopped, only shifted in different directions.

If the French Republic had decided to build Boullée’s Cenotaph or Coliseum, it would have not only broken the architectural records of its time but those of our own as well. This, above any other reason, explains why they were not built and, in all likelihood, never will be. As historian Jules Michelet, born the year after Boullée’s death in 1799, put it, “while the Empire had its columns and Royalty had the Louvre, the Revolution had for its monument . . . only the void. Its monument was the sand, as flat as that of Arabia. . . . A tumulus to the right and a tumulus to the left, like those erected by the Gauls, dark and doubtful witnesses to the memory of heroes.”

Étienne-Louis Boullée

Étienne-Louis Boullée (February 12, 1728 – February 4, 1799) was a visionary French neoclassical architect whose work is still influential today.

"Boullée, Claude-Nicolas Ledoux and Jean-Jacques Lequeu were each architects and thinkers whose ideas reflected some of the most radical strains of liberal bourgeois philosophy, with its cult of reason and devotion to the triplicate ideals of liberté, égalité , and fraternité . The structures they imagined and city plans they proposed were undeniably some of the most ambitious and revolutionary of their time. At their most fantastic, the buildings they envisioned were absolutely unbuildable — either according to the technical standards of their day or arguably even of our own." [1]

- 1 Proposals

- 3 Literature

Proposals [ edit ]

Cénotaphe à Newton [Newton Memorial], 1784

National Library, interior, 1785

Pyramidal cenotaph of the Sepulchral Chapel, c1786

Conical cenotaph of the Sepulchral Chapel, c1786

Conical cenotaph of the Sepulchral Chapel, interior, c1786

Metropolitan church at Corpus Christi

Museum, plan, 1789

neoclassical cutaway, 1790s

Writings [ edit ]

- Considérations sur l'importance et l'utilité de l'architecture, suivies de vues tendant au progrès des beaux-arts , manuscript, Bibliothèque nationale de France. (French)

- Boullée's Treatise on Architecture , ed. Helen Rosenau, London: Alec Tiranti, 1953. (English)

- Architettura. Saggio sull'arte , trans. & intro. Aldo Rossi, Padova: Marsillio, 1967. (Italian)

- "Architecture, Essay on Art" , trans. Sheila de Vallée, in Boullée & Visionary Architecture , ed. Helen Rosenau, London: Academy Editions & New York: Harmony Books, 1976, pp 81-116. (English)

- Arquitectura: Ensayo sobre el arte , trans. Carlos Manuel Fuentes, Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 1985. (Spanish)

- Architektur. Abhandlung über die Kunst , ed. Beat Wyss, Zürich/Munich, 1987. (German)

- Mémoire sur les moyens de procurer à la Bibliothèque du roi les avantages que ce monument exige , manuscript, Bibliothèque nationale de France. (French)

Literature [ edit ]

- Emil Kaufmann, "Étienne-Louis Boullée" , The Art Bulletin 21:3 (September 1939), pp 213-227.

- Trois architectes révolutionnaires, Boullée, Ledoux, Lequeu , Paris, 1978. (French)

- Emil Kaufmann, Architecture in the Age of Reason , Cambridge, 1955.

- Jean-Claude Lemagny (ed.), Visionary Architects: Boullée, Ledoux, Lequeu , New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1968. Catalogue. New edition: Hennessey & Ingalls, 2002.

- Jean-Marie Pérouse de Montclos, Étienne-Louis Boullée (1728-1799: Theoretician of Revolutionary Architecture) , George Braziller, 1974, 128 pp.

- Helen Rosenau (ed.), Boullée & Visionary Architecture , London: Academy Editions & New York: Harmony Books, 1976.

- Adolf Max Vogt, Radka Donnell, Kenneth Bendiner, "Orwell's 'Nineteen Eighty-Four' and Etienne-Louis Boullee's Drafts of 1784" , The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 43:1 (March 1984), pp 60-64.

- Annie Jacques, Jean-Pierre Mouilleseaux, Les Architectes de la Liberté , Paris: Gallimard, 1988, 196 pp. (French)

- Les Architectes de la liberté, 1789-1799 , Paris: École nationale des beaux-arts, 1989, 396 pp. Catalogue. (French)

- Jean-Marie Pérouse de Montclos, Boullée, architecte visionnaire , Hermann, 1993. (French)

- Jean-Marie Pérouse de Montclos, Étienne-Louis Boullée , Paris: Flammarion, 1994, 287 pp. (French)

- Jean-Claude Lemagny, Visionary Architects: Boullée, Ledoux, Lequeu , Hennessey & Ingalls, 2002.

- Ross Wolfe, "Revolutionary precursors: Radical bourgeois architects in the age of reason and revolution" , The Charnel-House blog, 25 June 2011.

Film [ edit ]

- The Belly of an Architect , dir. Peter Greenaway, 1987.

Links [ edit ]

- Boullée at French National Library (French)

- Boullée at BnF's Gallica

- Boullée at Wikipedia

- Architecture

- Featured articles

Navigation menu

Personal tools.

- Not logged in

- Contributions

- Create account

- Recent changes

- Recent files

- Batch upload

- What links here

- Related changes

- Special pages

- Printable version

- Permanent link

- Page information

- Browse bases

- This page was last edited on 25 May 2022, at 23:50.

- Privacy policy

- About Monoskop

- Disclaimers

The best free cultural &

educational media on the web

- Online Courses

- Certificates

- Degrees & Mini-Degrees

- Audio Books

The Futurist Architectural Designs Created by Étienne-Louis Boullée in the 18th Century

in Architecture , Art , History | February 15th, 2023 Leave a Comment

If a painter is ahead of his time, his work won’t sell particularly well while he’s alive. If an architect is ahead of his time, his work probably won’t exist at all — not in built form, at least. Such was the case with Étienne-Louis Boullée , who constructed few projects in the eighteenth century in which he lived, almost none of which remain standing today. The best Boullée devotees can do for a site of pilgrimage is the Hôtel Alexandre in Paris’ eighth arrondissement, which, though handsome enough, doesn’t quite offer a sense of why he would have devotees in the first place. To understand that, one must look to Boullée’s unbuilt works, the most notable of which are introduced in the video from Kings and Things above .

“Paper architect” identifies a member of the profession who may design structures prolifically but seldom, if ever, builds them. It is not a desirable label, especially in its implication of willful impracticality (even by architectural standards). But as practiced by Boullée, paper architecture became an art form unto itself: he left behind not just an extensive essay on his art , but voluminous drawings that envision a host of neoclassical buildings as ambitious in his time as they were unfashionable — and often, due to their sheer size, unbuildable.

These included an updated colosseum, a spherical cenotaph for Isaac Newton taller than the Great Pyramids of Giza, a basilica meant to give its beholders an impression of the universe itself, a royal library of near-Borgesian proportions, and even an actual Tower of Babel.

For Boullée, bigger was better, an idea that would sweep global architecture a century and a half after his death. By the mid-twentieth century, the world had also come to accept a Boullée-like preference for minimal ornamentation as well as his conception of what his contemporaries jokingly termed architecture parlante : that is, buildings that “speak” about their purpose visually, and in no uncertain terms. (You can hear more about it in the video below , a segment by professor Erika Naginski from Harvard’s online course “The Architectual Imagination.” ) When Boullée designed a Palace of Justice, he placed a courthouse directly over a jailhouse, articulating “one enormous metaphor for crime overwhelmed by the weight of justice.” This may have been a bit much even for the new French Republic, but for those who appreciated Boullée’s work, it pointed the way to the architecture of the future — a future we would later call modern.

Related content:

The World According to Le Corbusier: An Animated Introduction to the Most Modern of All Architects

The Unrealized Projects of Frank Lloyd Wright Get Brought to Life with 3D Digital Reconstructions

What Makes Paris Look Like Paris? A Creative Use of Google Street View

The Creation & Restoration of Notre-Dame Cathedral, Animated

Why Do People Hate Modern Architecture?: A Video Essay

How to Draw Like an Architect: An Introduction in Six Videos

Based in Seoul, Colin M arshall writes and broadcas ts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities , the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema . Follow him on Twitter at @colinma rshall or on Facebook .

by Colin Marshall | Permalink | Comments (0) |

Related posts:

Comments (0).

Be the first to comment.

Add a comment

Leave a reply.

Name (required)

Email (required)

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Click here to cancel reply.

- 1,700 Free Online Courses

- 200 Online Certificate Programs

- 100+ Online Degree & Mini-Degree Programs

- 1,150 Free Movies

- 1,000 Free Audio Books

- 150+ Best Podcasts

- 800 Free eBooks

- 200 Free Textbooks

- 300 Free Language Lessons

- 150 Free Business Courses

- Free K-12 Education

- Get Our Daily Email

Free Courses

- Art & Art History

- Classics/Ancient World

- Computer Science

- Data Science

- Engineering

- Environment

- Political Science

- Writing & Journalism

- All 1700 Free Courses

Receive our Daily Email

Free updates, get our daily email.

Get the best cultural and educational resources on the web curated for you in a daily email. We never spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

FOLLOW ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Free Movies

- 1150 Free Movies Online

- Free Film Noir

- Silent Films

- Documentaries

- Martial Arts/Kung Fu

- Free Hitchcock Films

- Free Charlie Chaplin

- Free John Wayne Movies

- Free Tarkovsky Films

- Free Dziga Vertov

- Free Oscar Winners

- Free Language Lessons

- All Languages

Free eBooks

- 700 Free eBooks

- Free Philosophy eBooks

- The Harvard Classics

- Philip K. Dick Stories

- Neil Gaiman Stories

- David Foster Wallace Stories & Essays

- Hemingway Stories

- Great Gatsby & Other Fitzgerald Novels

- HP Lovecraft

- Edgar Allan Poe

- Free Alice Munro Stories

- Jennifer Egan Stories

- George Saunders Stories

- Hunter S. Thompson Essays

- Joan Didion Essays

- Gabriel Garcia Marquez Stories

- David Sedaris Stories

- Stephen King

- Golden Age Comics

- Free Books by UC Press

- Life Changing Books

Free Audio Books

- 700 Free Audio Books

- Free Audio Books: Fiction

- Free Audio Books: Poetry

- Free Audio Books: Non-Fiction

Free Textbooks

- Free Physics Textbooks

- Free Computer Science Textbooks

- Free Math Textbooks

K-12 Resources

- Free Video Lessons

- Web Resources by Subject

- Quality YouTube Channels

- Teacher Resources

- All Free Kids Resources

Free Art & Images

- All Art Images & Books

- The Rijksmuseum

- Smithsonian

- The Guggenheim

- The National Gallery

- The Whitney

- LA County Museum

- Stanford University

- British Library

- Google Art Project

- French Revolution

- Getty Images

- Guggenheim Art Books

- Met Art Books

- Getty Art Books

- New York Public Library Maps

- Museum of New Zealand

- Smarthistory

- Coloring Books

- All Bach Organ Works

- All of Bach

- 80,000 Classical Music Scores

- Free Classical Music

- Live Classical Music

- 9,000 Grateful Dead Concerts

- Alan Lomax Blues & Folk Archive

Writing Tips

- William Zinsser

- Kurt Vonnegut

- Toni Morrison

- Margaret Atwood

- David Ogilvy

- Billy Wilder

- All posts by date

Personal Finance

- Open Personal Finance

- Amazon Kindle

- Architecture

- Artificial Intelligence

- Comics/Cartoons

- Current Affairs

- English Language

- Entrepreneurship

- Food & Drink

- Graduation Speech

- How to Learn for Free

- Internet Archive

- Language Lessons

- Most Popular

- Neuroscience

- Photography

- Pretty Much Pop

- Productivity

- UC Berkeley

- Uncategorized

- Video - Arts & Culture

- Video - Politics/Society

- Video - Science

- Video Games

Great Lectures

- Michel Foucault

- Sun Ra at UC Berkeley

- Richard Feynman

- Joseph Campbell

- Jorge Luis Borges

- Leonard Bernstein

- Richard Dawkins

- Buckminster Fuller

- Walter Kaufmann on Existentialism

- Jacques Lacan

- Roland Barthes

- Nobel Lectures by Writers

- Bertrand Russell

- Oxford Philosophy Lectures

Sign up for Newsletter

Open Culture scours the web for the best educational media. We find the free courses and audio books you need, the language lessons & educational videos you want, and plenty of enlightenment in between.

Great Recordings

- T.S. Eliot Reads Waste Land

- Sylvia Plath - Ariel

- Joyce Reads Ulysses

- Joyce - Finnegans Wake

- Patti Smith Reads Virginia Woolf

- Albert Einstein

- Charles Bukowski

- Bill Murray

- Fitzgerald Reads Shakespeare

- William Faulkner

- Flannery O'Connor

- Tolkien - The Hobbit

- Allen Ginsberg - Howl

- Dylan Thomas

- Anne Sexton

- John Cheever

- David Foster Wallace

Book Lists By

- Neil deGrasse Tyson

- Ernest Hemingway

- F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Allen Ginsberg

- Patti Smith

- Henry Miller

- Christopher Hitchens

- Joseph Brodsky

- Donald Barthelme

- David Bowie

- Samuel Beckett

- Art Garfunkel

- Marilyn Monroe

- Picks by Female Creatives

- Zadie Smith & Gary Shteyngart

- Lynda Barry

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Étienne-Louis Boullée (1728-1799) ; theoretician of revolutionary architecture

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

24 Previews

5 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station04.cebu on October 12, 2023

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Etienne-Louis Boullee & Neoclassical architecture

Related Papers

madalina staicu

Christina Contandriopoulos

Monalee Thakare

Juliette Eiffel

Procedia CPI

The rise of modern architecture led to a big change in Western and global architectural history. Instead of sticking to old ways, architects focused on new ideas and progress. They wanted to use science in their designs, which created a style of architecture that was used all over the world and based on logic and efficient materials. This kind of architecture is known for being useful and simple, without a lot of decorations. It changed over time, from making cities more friendly to people to connecting with local cultures. Later, postmodern architecture came about as a reaction to the limits of modernism. It wanted to make designs with more meaning, cultural identity, and history. Postmodern architecture is creative and diverse, not the same all the time. It cares about people and how they communicate. It looks different too, with curved lines and decorations. Modern and postmodern architectures are both special and unique. They show different styles and ideas because of when and why they were made.

jean-Philippe Garric

YUSUF CİVELEK

Although architects before the time of the French Enlightenment often made use of historical forms in their designs, this practice radically changed between the years 1750 and 1850. The fragment itself changed, as did the ways it was used. The transformation of the fragment followed three stages: it changed from the antique, to the elemental, to the historical fragment. Through the course of this transformation, design also changed, it came to be understood as composition. This dissertation describes the history of this transformation in consideration of writings by French author-architects, as well as their designs. It also shows how the new conception of the fragment gave birth to the next stage of architectural history: eclecticism. Mid eighteenth-century changes in European architecture were prompted by growing familiarity with recent archaeological work especially in Italy, the country of ancient ruins. In France, antique fragments were adopted initially as formal and spatial motifs that enriched architectural design by means of picturesque effects, inspired by paintings and Piranesian etchings. Later, these fragments gradually became regular elements of architectural composition. Charles Percier and Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand, two disciples of Boullée, took over his imagery and technique of composing with antique fragments, but relied less than he did on the building's picturesque and sensationalist aspects. Composition in elementary antique fragments underlay the neo-classical architectural education at both the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and the Ecole Polytechnique in the beginning of the nineteenth-century. In the 1830s, a group of pensionnaires argued for freer assembly of architectural elements that would allow diachronic reading of historical fragments as opposed to synchronic antique-looking motifs. Architects like Henri Labrouste, Léon Vaudoyer, and Félix Duban preferred imitating the historical progress of architecture over Greco-Roman elements and compositions. Eclecticism taught them that mixture of antithetical things gave birth to something new after a transitory phase. While neo-classical architecture imitated the mature architectural representation of a distant past, eclectic architecture of the romantic-rationalists imitated the immature expressions of the architecture in transition. The buildings of the second group revealed a new problem of representation in architecture, a problem that had begun to emerge already in the architecture of the eighteenth-century: the problem of style, expressed most famously if pathetically in the early nineteenth-century as a question: "in what style shall we build?"

Ziyad Akhtar

hugues henri

In Theories and History of Architecture (1968) and in Project and Utopia (1973), the Italian historian Manfredo Tafuri identifies two cuts that establish modernity: 1st Brunelleschi's work in Florence in the 15th century. 2nd In architecture in the Age of Enlightenment and more particularly in the engravings of the Carceri of Piranesi, in which he agrees with Scully's interpretation. Tafuri's Marxist analysis sheds new light on the origins of modernity. Chicago at the end of the 19th century has a value as a testimony to the situation of architecture faced with capitalist urban modernity. Methodologically, however, Tafuri's approach is underpinned by the desire to show the gradual disappearance of architecture as an autonomous instance of intervention in urban space. By privileging the determination of architectural work through economic infrastructures, Tafuri comes to consider architecture as a pure ideological instance whose effectiveness is considerably reduced by the dominant context of new production relationships. Ultimately, it is around the postulate of the erasure of the architectural object in the modern era that a critical study of Tafuri's work can be made: is this trend inevitable? Is architecture condemned to immerse itself in the city in a fragmentary, neutral and reproducible form? What is meant by architecture of the pure sign? Tafuri's Marxist analysis sheds new light on the origins of modernity. Chicago at the end of the 19th century has a value as a testimony to the situation of architecture faced with capitalist urban modernity. Methodologically, however, Tafuri's approach is underpinned by the desire to show the gradual disappearance of architecture as an autonomous instance of intervention in urban space. By privileging the determination of architectural work through economic infrastructures, Tafuri comes to consider architecture as a pure ideological instance whose effectiveness is considerably reduced by the dominant context of new production relationships. Ultimately, it is around the postulate of the erasure of the architectural object in the modern era that a critical study of Tafuri's work can be made: is this trend inevitable? Is architecture condemned to immerse itself in the city in a fragmentary, neutral and reproducible form? What is meant by architecture of the pure sign? Tafuri's Marxist analysis sheds new light on the origins of modernity. Chicago at the end of the 19th century has a value as a testimony to the situation of architecture faced with capitalist urban modernity. Methodologically, however, Tafuri's approach is underpinned by the desire to show the gradual disappearance of architecture as an autonomous instance of intervention in urban space. By privileging the determination of architectural work through economic infrastructures, Tafuri comes to consider architecture as a pure ideological instance whose effectiveness is considerably reduced by the dominant context of new production relationships. Ultimately, it is around the postulate of the erasure of the architectural object in the modern era that a critical study of Tafuri's work can be made: is this trend inevitable? Is architecture condemned to immerse itself in the city in a fragmentary, neutral and reproducible form? What is meant by architecture of the pure sign? Historically, the fascination that America exerted on Europeans from the beginning of the 19th century can be explained by the fact that it is an ideology in itself, embodying the conjunction of the two scenes, that of the future and that of modernity. The current paradox, in the postmodern context, is the American rejection of modernity, as a whole, without an inventory having been made to restore to modernity as the "stage of the future" its archaic American part, which has little to do with European modernity. Thus, revisionist postmodernist historians and architect-theorists of architecture favor eclecticism in restored architecture as a positive value based on attributing commonly recognized meanings to architectural forms. They celebrate the period 1893-1938, which corresponds to the eclipse of modernity in the USA, between the two schools of Chicago, that of Sullivan and that of Mies van der Rohe. Revisionist history not only relativizes the contribution of the Chicago school, but the entire modernist scheme is called into question, starting with the discredit that all modernist historians cast on the Colombian Exhibition of 1893. For Giedion, for example, it appeared to be an aberration of history. According to Stuart Cohen, the architectural neo-classicism that was revived in 1893 was perfectly adapted to the American historical context of the time. In the reactionary rejection of modernity in its entirety by the revisionists, there is an iconoclastic will towards the glories of modernity, like Gropius but especially Mies van der Rohe.In conclusion, the idea of modernity appeared to some historians and theorists as an ideological one.

Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences

William Brumfield

After 1905 a reaction against the modernist movement in architecture appeared in the work of architects and critics who supported a revival of Neoclassicism in Russian architecture. Although the new classicism provided the means to apply technological and design innovations within an established tectonic system, it was also widely interpreted as a rejection of the unstable values of individualism and the bourgeois ethos. Neoclassical architecture became the last hope for a reconciliation of contemporary architecture with cultural values derived from an idealization of imperial Russian grandeur. Yet the revival of Neoclassicism ultimately manifested the same lack of aesthetic unity and theoretical direction as had the style moderne, thus leading certain critics and architects to question the social order within which architecture functioned in the decades before the 1917 revolution. This debate would have lasting repercussions for Soviet architecture.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

dhiana rose sengco

International Academic Studies in Architecture, Planning and Design

Sara Galletti

Review of applied socio-economic research

Sidonia Teodorescu

From Ornament to Object. Genealogies of Architectural Modernism

Alina Payne

BRAU4 Biennial of Architectural and Urban Restoration

Thanos Balafoutis , Stelios Zerefos

History Compass

Bauhaus Culture

Wallis Miller

Common Knowledge

Anthony Vidler

ANYANWU BLESSING CHIKA

juliette Pommier

SURYAKANT DAKSH

Jose Hernandez

Companion to Architecture in the Age of Enlightenment

Christopher Drew Armstrong

Building Knowledge, Constructing Histories

Pedro P Palazzo

mohamad yehya

Anthony Zonaga

YiBing Wang

Interstices: Journal of Architecture and Related Arts

Milica Madjanovic

Michael McMordie

The Characteristics of Classical Architecture in Corbusier's Modernism

Coleen Harewood

Athens Journal of Architecture

Simone Solinas

Theoretical Perspectives, Centre for Research on Politics; University of Dhaka

Zebun Nasreen Ahmed

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Aeon Video has a monthly newsletter!

Get curated editors’ picks, peeks behind the scenes, film recommendations and more.

The radically impractical 18th-century architect whose ideas on beauty endure

Today, the ideas of the 18th-century French architect Étienne-Louis Boullée influence building designs around the world. However, during his life, Boullée was more interested in the poetic potential of architecture than concocting practical plans, and built very few structures that remain standing today. Instead, his lasting impact derives from his bold proposals for buildings that reflected the beauty he found in geometric simplicity and symmetry, presented on exceptionally grand scales. Working through drawings of some of Boullée’s proposed and never-realised buildings – from a stadium with a capacity of 300,000, to a real-life Tower of Babel and a fantastical monument to Isaac Newton – this video essay from the YouTube channel Kings and Things explores how he borrowed from and expanded upon classical architecture for inspiration, as well as how his ideas had a resurgence upon the publication of his writings in 1953, some 250 years after his death.

Video by Kings and Things

Sex and sexuality

From secret crushes to self-acceptance – a joyful chronicle of ‘old lesbian’ stories

Forging a cello from pieces of wood demands its own form of virtuosity

Scenes from a school year paint a refreshingly nuanced portrait of rural America

The rhythms of a star system inspire a pianist’s transfixing performance

Is it ethical to have a second child so that your first might live?

Watch as Japan’s surplus trees are transformed into forest-tinted crayons

Meaning and the good life

‘Everydayness is the enemy’ – excerpts from the existentialist novel ‘The Moviegoer’

Pleasure and pain

The volunteer musicians who perform in the aftermath of violence and tragedy

Food and drink

Local tensions simmer amid a potato salad contest at the Czech-Polish border

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Since 1896, The Architectural Review has scoured the globe for architecture that challenges and inspires. Buildings old and new are chosen as prisms through which arguments and broader narratives are constructed. In their fearless storytelling, independent critical voices explore the forces that shape the homes, cities and places we inhabit.

Boullee Etienne-Louis Architecture Essay on Art - Free download as PDF File (.pdf) or read online for free. Scribd is the world's largest social reading and publishing site.

Some of his work only saw the light of day in the 20th century; his book Architecture, essai sur l'art ("Essay on the Art of Architecture), arguing for an emotionally committed Neoclassicism, was only published in 1953. The volume contained his work from 1778 to 1788, which mostly comprised designs for public buildings on a wholly impractical ...

Architecture, Essay on Art. Etienne Louis Boullée. Academy Editions, 1976 - Architecture - 158 pages.

Includes "Architecture, essai sur l'art", and its translation "Architecture, essay on art" Bibliography: p. 156 Includes index Access-restricted-item true ... Associated-names Boullée, Etienne Louis, 1728-1799. Architecture Autocrop_version ..14_books-20220331-.2 Boxid IA40753924 Camera USB PTP Class Camera

Boullee Etienne-Louis Architecture Essay on Art - Free download as PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or read online for free. In addition to anew translation ofBoullee'sEssai, itsfirstappearance in english, theoriginalFrench texthas been included in thisbook. Frompage40topage 65in theMSisfound thedraftoftheEssal, which begins on page 69.

Étienne-Louis Boullée (born February 12, 1728, Paris, France—died February 6, 1799, Paris) was a French visionary architect, theorist, and teacher.. Boullée wanted originally to be a painter, but, following the wishes of his father, he turned to architecture.He studied with J.-F. Blondel and Germain Boffrand and with J.-L. Legeay and had opened his own studio by the age of 19.