11 Skills and Traits You Need to Be a Successful Qualitative Researcher

Essential skills and traits for successful qualitative researchers: insights, empathy, analysis, communication.

Reshu Rathi

June 30, 2023

In this Article

Are you new to research or looking to switch careers and move to research? Or you are a pro at research but still want to know the qualities of an excellent qualitative researcher that you already possess. If you belong to any of the above three categories, you have landed at the right place.

Every profession demands certain qualities from its practitioners, and market research is no exception; to succeed in it, every qualitative researcher needs the qualities we cover in this article.

When we say qualities, we are talking about the ‘must haves’ – the key characteristics and attributes of a good researcher. The ones that help them fly high and far - not the generic qualities like hard work, determination to succeed, etc. These are a necessity for any job in the world.

The qualities we will discuss are absolutely inevitable for qualitative researchers - the ones that will upgrade your status from researcher to a great qualitative researcher.

Now let’s get to it - shall we?

The Key Skills Required to Be a Great Qualitative Researcher

Here are some of the skills every qualitative researcher should have. Consider how you can incorporate more of these skills into your research efforts to become better at conducting market research.

How to be a Good Qualitative Researcher

There is no quick way to become an excellent researcher, but the skills mentioned below can put you on the path to success sooner rather than later, especially if you are a qualitative researcher.

Success Trait #1: Good Communicator

The key to understanding your customers is asking good questions. Good communication skills can greatly help you in this information elicitation phase. Clear and concise questions can help you know your customers better.

To kickstart your communication skills into high gear, always start by getting clear on the goal behind each question you are crafting. With awareness of what you are trying to accomplish by asking these questions, it will be easier to focus on the details that matter most- which in turn help you drive a meaningful outcome.

Also, great communicators are usually not just good speakers, but they also know how to read others' body language. Wondering how it can help you in your research process? Well, people can say anything they want; but their body language often reveals their true intentions or meaning. Good researchers know how to read body language, which helps them anticipate the direction a conversation is heading.

Success Trait #2: Active Listening

Good listening involves paying close and keen attention to what your consumers say. Basically, doing active and perspective listening - now we know it is not easy.

In fact, perspective listening is one of the most complex skills because it requires you to be totally focused, completely mindful, and well perceptive of what is happening. And, yes, you cannot acquire this skill or quality in a day, but you can start learning it today.

Most researchers fail to understand their consumers deeply because of the 'consumer communication barrier.' They fail to get into their consumer's minds and understand them inside out.

The only way to get to understand your consumers and know what they want is by listening to what they are saying. Successful qualitative researchers know good listening and its role in understanding consumers.

Success Trait #3: Well-Prepared

It is no secret that customer interviews, when done effectively, can help you build a better business. But do you know a successful interview is more than a simple Q&A session; it is a conversation?

Conducting successful consumer interviews requires a tremendous amount of research, confidence, and flawless execution. There are too many ways to get it wrong, and only one sure-fire way to get it right — be prepared.

Highly successful researchers use every resource at their disposal to research and prepare for every interview. They know exactly what they will ask before they start the discussion. They prepare their questions in advance - they conduct mock interviews to better tune their questions to maximize the effect.

They do not hesitate to ask again if something is not clear. They talk less and focus more on listening. They are not afraid of pauses and moments of silence, and they do not rush to fill those silent moments as they know participants may just be thinking over the question. They tailor every question based on consumer responses to better understand the consumer they are interviewing.

In short, a lot goes into planning and conducting an effective remote user interview. But such meticulous preparation always pays off in the form of deep, actionable insights that can help you design better products, improve customer experiences, etc. So, there is no excuse for conducting bad customer interviews. It simply boils down to one simple thing — doing the work by preparing in advance.

{{cta-button}}

Success Trait #4: Open to New Technologies

The fourth trait that all successful researchers must possess is they are tech-savvy - they are open to exploring new technologies.

As consumer behavior evolves rapidly, technology plays a vital role in increasing business agility. Technology democratizes market research while providing high-quality intelligence, allowing brands to move quickly and confidently.

Qualitative market research is now in the technology-driven era. Data is everywhere, and we have more access to it than ever before - because we now have so much data about consumers, it is vital to use technology to get value from it.

An excellent qualitative researcher is open to exploring and leveraging these new technologies. As they know, research tools powered by AI and emotion AI can make fast work of this data.

These tools can deliver deep consumer insights into what consumers feel. For example, if you are using Decode, an emotion AI-powered qualitative research platform, you can even track human emotions at a granular level using emotion AI and other technologies. This gives researchers a peek into their consumer's mindset, which was previously difficult to get.

Also Read: Automate or Deteriorate: Why Consumer Researchers Must Adopt Tech

Success Trait #5: Analytical Thinker/Understand Data and Metrics

Being a researcher, you are not expected to conduct just research. You need to collect and understand the data - you need to analyze and interpret it to get value from it.

Now, I know qualitative data can be challenging and time-consuming to analyze and interpret. At the end of your research phase, you may have a lot of audio or video-based data to work through. And making sense of all this data is no small task. You need to have good analytical skills to make sense of this data.

Also, you need a conversation analytics platform to unlock this data. One that lets you tap into your customers’ emotions and comprehend the subtle human elements, behavioral nuances, and context of these virtual conversations using technologies like facial coding, voice tonality, and text-based sentiment analytics.

Success Trait #6: Comfortable with Silence

Well, this may surprise you, but believe me, it is one of the most important traits a researcher should have. Most researchers are too uncomfortable with silence. When they ask a question, and the customer gets quiet, they immediately try to fill the silence by asking another question or a follow-up question or clarifying their ask. This is a mistake - sometimes, customers need time to collect their thoughts before answering the question.

So, pause for around four-to-five seconds before speaking. This way, you can ensure that you are not interrupting a critical thought your customer might be having. Also, this way, you can set the precedent that silence is welcome in your conversations.

Success Trait #7: Do Not Believe in Making Assumptions

A good researcher never assumes anything. But this is one of the qualities most researchers tend to lose as they gain more experience. Most researchers tend to develop the habit of taking things for granted - they start assuming things.

If you have been a qualitative researcher for a while, you can easily fall into a routine. But just because the ten consumers you interviewed had the same problems does not mean the 11th one will have the same one too.

Never make assumptions about your consumers or their situation. It only takes a few seconds to ask a question and a follow-up question. Making assumptions can hurt your research results.

As a qualitative researcher, you should never assume anything because bad ideas are often the result of guesswork. So instead of assuming things, you should ask questions and focus on listening. Simply listening to your customers and focusing on their experience, you are less likely to get pulled in the wrong direction.

Success Trait #8: Being Empathetic Towards Customer

According to me, one of the most valued skills a researcher must possess is empathy with the customer or the consumer. By empathy, I mean the researcher should put himself in the consumers' shoes.

Empathy drives connection and incorporating empathy into your research process allows you to transcend your assumptions to get insight into the audience. And when the audience senses the researchers' empathy, they are more likely to be open with them.

Also, empathy for customers will help you connect with them on a deeper level, enabling you to get deep consumer insights. And yet empathy is a skill we rarely talk about. Why? Because we just assume we have empathy. Well, most researchers do not, or if they do, it is not enough. Empathy is a journey; it is a skill you need to cultivate - all it takes is a little focused attention.

Success Trait #9: Curiosity

Another vital quality of a good qualitative researcher is curiosity. Though we have all heard the common idiom "Curiosity killed the cat," a little curiosity or interest will only make a qualitative researcher better at doing the research.

How? Basically, curiosity is the desire to always learn something. Being curious about why consumers say what they are saying is only the start.

Successful researchers are also curious about the latest market trends, what is happening in the industry, and how it impacts their consumers' preferences.

This, in turn, pushes them to become the best at what they do. However, this requires a lot of time, dedication, and market and sales process research. But success with a little effort is worth it.

Success Trait #10: A Clear Sense of Direction

The final trait that all successful researchers must possess is a clear sense of direction. Because of the turbulence and rapid change in today's marketplace and constantly evolving consumer expectations, most researchers lack clarity. They are not clear about the direction they want to go in. They are preoccupied with short-term problems and want to deliver quick results.

Though the existing model of market research is broken, it is too slow, too expensive, and not sufficiently useful. But that does not mean market research is going anywhere. In fact, it is essential to the success of every organization.

Did you know that the global revenue of the market research industry exceeded 76.4 billion U.S. dollars in 2021, growing more than twofold since 2008?

So, market research and researchers are not going anywhere. It is just that you need the right tools to conduct market research, and you need some skills to conduct it successfully. And one such skill is you need to set clear targets and directions for yourself to succeed in these turbulent times.

Success Trait #11: Genuine Interest in Consumers and Studying the Market

You should have a fascination with figuring consumers out—what are they interested in? What makes them tick? What do they want from your product or service? Why do they do what they do? Identify what they need, then focus on fulfilling their expectations.

Ultimately, market research is all about knowing your consumers, their pain point, wants, or needs, and studying your market, product, and company. To do it well, you need to have a genuine interest in knowing your consumers and digging for information.

The researchers who know how to connect with consumers and where to dig for information, understand, collect, and analyze the

Over to You

These are the 11 qualities that make you an excellent qualitative researcher. So, whether you are already a qualitative researcher or considering research as a career, I hope this list helps you evaluate yourself and decide if this field is a good fit for you.

Without these qualities, you will never excel in the qualitative research field. So, try to imbibe these qualities as every good researcher only becomes one after cultivating these qualities.

Remember, these skills and qualities are learnable, and even if you do not possess them right now, you can cultivate them as long as you are willing to do the work.

Frequently Asked Questions

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.

With lots of unique blocks, you can easily build a page without coding.

Click on Study templates

Start from scratch

Add blocks to the content

Saving the Template

Publish the Template

Reshu Rathi is an online marketing and conversion rate enthusiast. She specializes in content marketing, lead generation, and engagement strategy. Her byline can be found all over the web

Product Marketing Specialist

Related Articles

Top AI Events You Do Not Want to Miss in 2024

Here are all the top AI events for 2024, curated in one convenient place just for you.

Top Insights Events You Do Not Want to Miss in 2024

Here are all the top Insights events for 2024, curated in one convenient place just for you.

Top CX Events You Do Not Want to Miss in 2024

Here are all the top CX events for 2024, curated in one convenient place just for you.

How to Build an Experience Map: A Complete Guide

An experience map is essential for businesses, as it highlights the customer journey, uncovering insights to improve user experiences and address pain points. Read to find more!

Everything You Need to Know about Intelligent Scoring

Are you curious about Intelligent Scoring and how it differs from regular scoring? Discover its applications and benefits. Read on to learn more!

Qualitative Research Methods and Its Advantages In Modern User Research

Discover how to leverage qualitative research methods, including moderated sessions, to gain deep user insights and enhance your product and UX decisions.

The 10 Best Customer Experience Platforms to Transform Your CX

Explore the top 10 CX platforms to revolutionize customer interactions, enhance satisfaction, and drive business growth.

TAM SAM SOM: What It Means and How to Calculate It?

Understanding TAM, SAM, SOM helps businesses gauge market potential. Learn their definitions and how to calculate them for better business decisions and strategy.

Understanding Likert Scales: Advantages, Limitations, and Questions

Using Likert scales can help you understand how your customers view and rate your product. Here's how you can use them to get the feedback you need.

Mastering the 80/20 Rule to Transform User Research

Find out how the Pareto Principle can optimize your user research processes and lead to more impactful results with the help of AI.

Understanding Consumer Psychology: The Science Behind What Makes Us Buy

Gain a comprehensive understanding of consumer psychology and learn how to apply these insights to inform your research and strategies.

A Guide to Website Footers: Best Design Practices & Examples

Explore the importance of website footers, design best practices, and how to optimize them using UX research for enhanced user engagement and navigation.

Customer Effort Score: Definition, Examples, Tips

A great customer score can lead to dedicated, engaged customers who can end up being loyal advocates of your brand. Here's what you need to know about it.

How to Detect and Address User Pain Points for Better Engagement

Understanding user pain points can help you provide a seamless user experiences that makes your users come back for more. Here's what you need to know about it.

What is Quota Sampling? Definition, Types, Examples, and How to Use It?

Discover Quota Sampling: Learn its process, types, and benefits for accurate consumer insights and informed marketing decisions. Perfect for researchers and brand marketers!

What Is Accessibility Testing? A Comprehensive Guide

Ensure inclusivity and compliance with accessibility standards through thorough testing. Improve user experience and mitigate legal risks. Learn more.

Maximizing Your Research Efficiency with AI Transcriptions

Explore how AI transcription can transform your market research by delivering precise and rapid insights from audio and video recordings.

Understanding the False Consensus Effect: How to Manage it

The false consensus effect can cause incorrect assumptions and ultimately, the wrong conclusions. Here's how you can overcome it.

5 Banking Customer Experience Trends to Watch Out for in 2024

Discover the top 5 banking customer experience trends to watch out for in 2024. Stay ahead in the evolving financial landscape.

The Ultimate Guide to Regression Analysis: Definition, Types, Usage & Advantages

Master Regression Analysis: Learn types, uses & benefits in consumer research for precise insights & strategic decisions.

EyeQuant Alternative

Meet Qatalyst, your best eyequant alternative to improve user experience and an AI-powered solution for all your user research needs.

EyeSee Alternative

Embrace the Insights AI revolution: Meet Decode, your innovative solution for consumer insights, offering a compelling alternative to EyeSee.

Skeuomorphism in UX Design: Is It Dead?

Skeuomorphism in UX design creates intuitive interfaces using familiar real-world visuals to help users easily understand digital products. Do you know how?

Top 6 Wireframe Tools and Ways to Test Your Designs

Wireframe tools assist designers in planning and visualizing the layout of their websites. Look through this list of wireframing tools to find the one that suits you best.

Revolutionizing Customer Interaction: The Power of Conversational AI

Conversational AI enhances customer service across various industries, offering intelligent, context-aware interactions that drive efficiency and satisfaction. Here's how.

User Story Mapping: A Powerful Tool for User-Centered Product Development

Learn about user story mapping and how it can be used for successful product development with this blog.

What is Research Hypothesis: Definition, Types, and How to Develop

Read the blog to learn how a research hypothesis provides a clear and focused direction for a study and helps formulate research questions.

Understanding Customer Retention: How to Keep Your Customers Coming Back

Understanding customer retention is key to building a successful brand that has repeat, loyal customers. Here's what you need to know about it.

Demographic Segmentation: How Brands Can Use it to Improve Marketing Strategies

Read this blog to learn what demographic segmentation means, its importance, and how it can be used by brands.

Mastering Product Positioning: A UX Researcher's Guide

Read this blog to understand why brands should have a well-defined product positioning and how it affects the overall business.

Discrete Vs. Continuous Data: Everything You Need To Know

Explore the differences between discrete and continuous data and their impact on business decisions and customer insights.

50+ Employee Engagement Survey Questions

Understand how an employee engagement survey provides insights into employee satisfaction and motivation, directly impacting productivity and retention.

What is Experimental Research: Definition, Types & Examples

Understand how experimental research enables researchers to confidently identify causal relationships between variables and validate findings, enhancing credibility.

A Guide to Interaction Design

Interaction design can help you create engaging and intuitive user experiences, improving usability and satisfaction through effective design principles. Here's how.

Exploring the Benefits of Stratified Sampling

Understanding stratified sampling can improve research accuracy by ensuring diverse representation across key subgroups. Here's how.

A Guide to Voice Recognition in Enhancing UX Research

Learn the importance of using voice recognition technology in user research for enhanced user feedback and insights.

The Ultimate Figma Design Handbook: Design Creation and Testing

The Ultimate Figma Design Handbook covers setting up Figma, creating designs, advanced features, prototyping, and testing designs with real users.

The Power of Organization: Mastering Information Architectures

Understanding the art of information architectures can enhance user experiences by organizing and structuring digital content effectively, making information easy to find and navigate. Here's how.

Convenience Sampling: Examples, Benefits, and When To Use It

Read the blog to understand how convenience sampling allows for quick and easy data collection with minimal cost and effort.

What is Critical Thinking, and How Can it be Used in Consumer Research?

Learn how critical thinking enhances consumer research and discover how Decode's AI-driven platform revolutionizes data analysis and insights.

How Business Intelligence Tools Transform User Research & Product Management

This blog explains how Business Intelligence (BI) tools can transform user research and product management by providing data-driven insights for better decision-making.

What is Face Validity? Definition, Guide and Examples

Read this blog to explore face validity, its importance, and the advantages of using it in market research.

What is Customer Lifetime Value, and How To Calculate It?

Read this blog to understand how Customer Lifetime Value (CLV) can help your business optimize marketing efforts, improve customer retention, and increase profitability.

Systematic Sampling: Definition, Examples, and Types

Explore how systematic sampling helps researchers by providing a structured method to select representative samples from larger populations, ensuring efficiency and reducing bias.

Understanding Selection Bias: A Guide

Selection bias can affect the type of respondents you choose for the study and ultimately the quality of responses you receive. Here’s all you need to know about it.

A Guide to Designing an Effective Product Strategy

Read this blog to explore why a well-defined product strategy is required for brands while developing or refining a product.

A Guide to Minimum Viable Product (MVP) in UX: Definition, Strategies, and Examples

Discover what an MVP is, why it's crucial in UX, strategies for creating one, and real-world examples from top companies like Dropbox and Airbnb.

Asking Close Ended Questions: A Guide

Asking the right close ended questions is they key to getting quantitiative data from your users. Her's how you should do it.

Creating Website Mockups: Your Ultimate Guide to Effective Design

Read this blog to learn website mockups- tools, examples and how to create an impactful website design.

Understanding Your Target Market And Its Importance In Consumer Research

Read this blog to learn about the importance of creating products and services to suit the needs of your target audience.

What Is a Go-To-Market Strategy And How to Create One?

Check out this blog to learn how a go-to-market strategy helps businesses enter markets smoothly, attract more customers, and stand out from competitors.

What is Confirmation Bias in Consumer Research?

Learn how confirmation bias affects consumer research, its types, impacts, and practical tips to avoid it for more accurate and reliable insights.

Market Penetration: The Key to Business Success

Understanding market penetration is key to cracking the code to sustained business growth and competitive advantage in any industry. Here's all you need to know about it.

How to Create an Effective User Interface

Having a simple, clear user interface helps your users find what they really want, improving the user experience. Here's how you can achieve it.

Product Differentiation and What It Means for Your Business

Discover how product differentiation helps businesses stand out with unique features, innovative designs, and exceptional customer experiences.

What is Ethnographic Research? Definition, Types & Examples

Read this blog to understand Ethnographic research, its relevance in today’s business landscape and how you can leverage it for your business.

Product Roadmap: The 2024 Guide [with Examples]

Read this blog to understand how a product roadmap can align stakeholders by providing a clear product development and delivery plan.

Product Market Fit: Making Your Products Stand Out in a Crowded Market

Delve into the concept of product-market fit, explore its significance, and equip yourself with practical insights to achieve it effectively.

Consumer Behavior in Online Shopping: A Comprehensive Guide

Ever wondered how online shopping behavior can influence successful business decisions? Read on to learn more.

How to Conduct a First Click Test?

Why are users leaving your site so fast? Learn how First Click Testing can help. Discover quick fixes for frustration and boost engagement.

What is Market Intelligence? Methods, Types, and Examples

Read the blog to understand how marketing intelligence helps you understand consumer behavior and market trends to inform strategic decision-making.

What is a Longitudinal Study? Definition, Types, and Examples

Is your long-term research strategy unclear? Learn how longitudinal studies decode complexity. Read on for insights.

What Is the Impact of Customer Churn on Your Business?

Understanding and reducing customer churn is the key to building a healthy business that keeps customers satisfied. Here's all you need to know about it.

The Ultimate Design Thinking Guide

Discover the power of design thinking in UX design for your business. Learn the process and key principles in our comprehensive guide.

100+ Yes Or No Survey Questions Examples

Yes or no survey questions simplify responses, aiding efficiency, clarity, standardization, quantifiability, and binary decision-making. Read some examples!

What is Customer Segmentation? The ULTIMATE Guide

Explore how customer segmentation targets diverse consumer groups by tailoring products, marketing, and experiences to their preferred needs.

Crafting User-Centric Websites Through Responsive Web Design

Find yourself reaching for your phone instead of a laptop for regular web browsing? Read on to find out what that means & how you can leverage it for business.

How Does Product Placement Work? Examples and Benefits

Read the blog to understand how product placement helps advertisers seek subtle and integrated ways to promote their products within entertainment content.

The Importance of Reputation Management, and How it Can Make or Break Your Brand

A good reputation management strategy is crucial for any brand that wants to keep its customers loyal. Here's how brands can focus on it.

A Comprehensive Guide to Human-Centered Design

Are you putting the human element at the center of your design process? Read this blog to understand why brands must do so.

How to Leverage Customer Insights to Grow Your Business

Genuine insights are becoming increasingly difficult to collect. Read on to understand the challenges and what the future holds for customer insights.

The Complete Guide to Behavioral Segmentation

Struggling to reach your target audience effectively? Discover how behavioral segmentation can transform your marketing approach. Read more in our blog!

Creating a Unique Brand Identity: How to Make Your Brand Stand Out

Creating a great brand identity goes beyond creating a memorable logo - it's all about creating a consistent and unique brand experience for your cosnumers. Here's everything you need to know about building one.

Understanding the Product Life Cycle: A Comprehensive Guide

Understanding the product life cycle, or the stages a product goes through from its launch to its sunset can help you understand how to market it at every stage to create the most optimal marketing strategies.

Empathy vs. Sympathy in UX Research

Are you conducting UX research and seeking guidance on conducting user interviews with empathy or sympathy? Keep reading to discover the best approach.

What is Exploratory Research, and How To Conduct It?

Read this blog to understand how exploratory research can help you uncover new insights, patterns, and hypotheses in a subject area.

First Impressions & Why They Matter in User Research

Ever wonder if first impressions matter in user research? The answer might surprise you. Read on to learn more!

Cluster Sampling: Definition, Types & Examples

Read this blog to understand how cluster sampling tackles the challenge of efficiently collecting data from large, spread-out populations.

Top Six Market Research Trends

Curious about where market research is headed? Read on to learn about the changes surrounding this field in 2024 and beyond.

Lyssna Alternative

Meet Qatalyst, your best lyssna alternative to usability testing, to create a solution for all your user research needs.

What is Feedback Loop? Definition, Importance, Types, and Best Practices

Struggling to connect with your customers? Read the blog to learn how feedback loops can solve your problem!

UI vs. UX Design: What’s The Difference?

Learn how UI solves the problem of creating an intuitive and visually appealing interface and how UX addresses broader issues related to user satisfaction and overall experience with the product or service.

The Impact of Conversion Rate Optimization on Your Business

Understanding conversion rate optimization can help you boost your online business. Read more to learn all about it.

Insurance Questionnaire: Tips, Questions and Significance

Leverage this pre-built customizable questionnaire template for insurance to get deep insights from your audience.

UX Research Plan Template

Read on to understand why you need a UX Research Plan and how you can use a fully customizable template to get deep insights from your users!

Brand Experience: What it Means & Why It Matters

Have you ever wondered how users navigate the travel industry for your research insights? Read on to understand user experience in the travel sector.

Validity in Research: Definitions, Types, Significance, and Its Relationship with Reliability

Is validity ensured in your research process? Read more to explore the importance and types of validity in research.

The Role of UI Designers in Creating Delightful User Interfaces

UI designers help to create aesthetic and functional experiences for users. Here's all you need to know about them.

Top Usability Testing Tools to Try

Using usability testing tools can help you understand user preferences and behaviors and ultimately, build a better digital product. Here are the top tools you should be aware of.

Understanding User Experience in Travel Market Research

Ever wondered how users navigate the travel industry for your research insights? Read on to understand user experience in the travel sector.

Top 10 Customer Feedback Tools You’d Want to Try

Explore the top 10 customer feedback tools for analyzing feedback, empowering businesses to enhance customer experience.

10 Best UX Communities on LinkedIn & Slack for Networking & Collaboration

Discover the significance of online communities in UX, the benefits of joining communities on LinkedIn and Slack, and insights into UX career advancement.

The Role of Customer Experience Manager in Consumer Research

This blog explores the role of Customer Experience Managers, their skills, their comparison with CRMs, their key metrics, and why they should use a consumer research platform.

Product Review Template

Learn how to conduct a product review and get insights with this template on the Qatalyst platform.

What Is the Role of a Product Designer in UX?

Product designers help to create user-centric digital experiences that cater to users' needs and preferences. Here's what you need to know about them.

Top 10 Customer Journey Mapping Tools For Market Research in 2024

Explore the top 10 tools in 2024 to understand customer journeys while conducting market research.

Generative AI and its Use in Consumer Research

Ever wondered how Generative AI fits in within the research space? Read on to find its potential in the consumer research industry.

All You Need to Know About Interval Data: Examples, Variables, & Analysis

Understand how interval data provides precise numerical measurements, enabling quantitative analysis and statistical comparison in research.

How to Use Narrative Analysis in Research

Find the advantages of using narrative analysis and how this method can help you enrich your research insights.

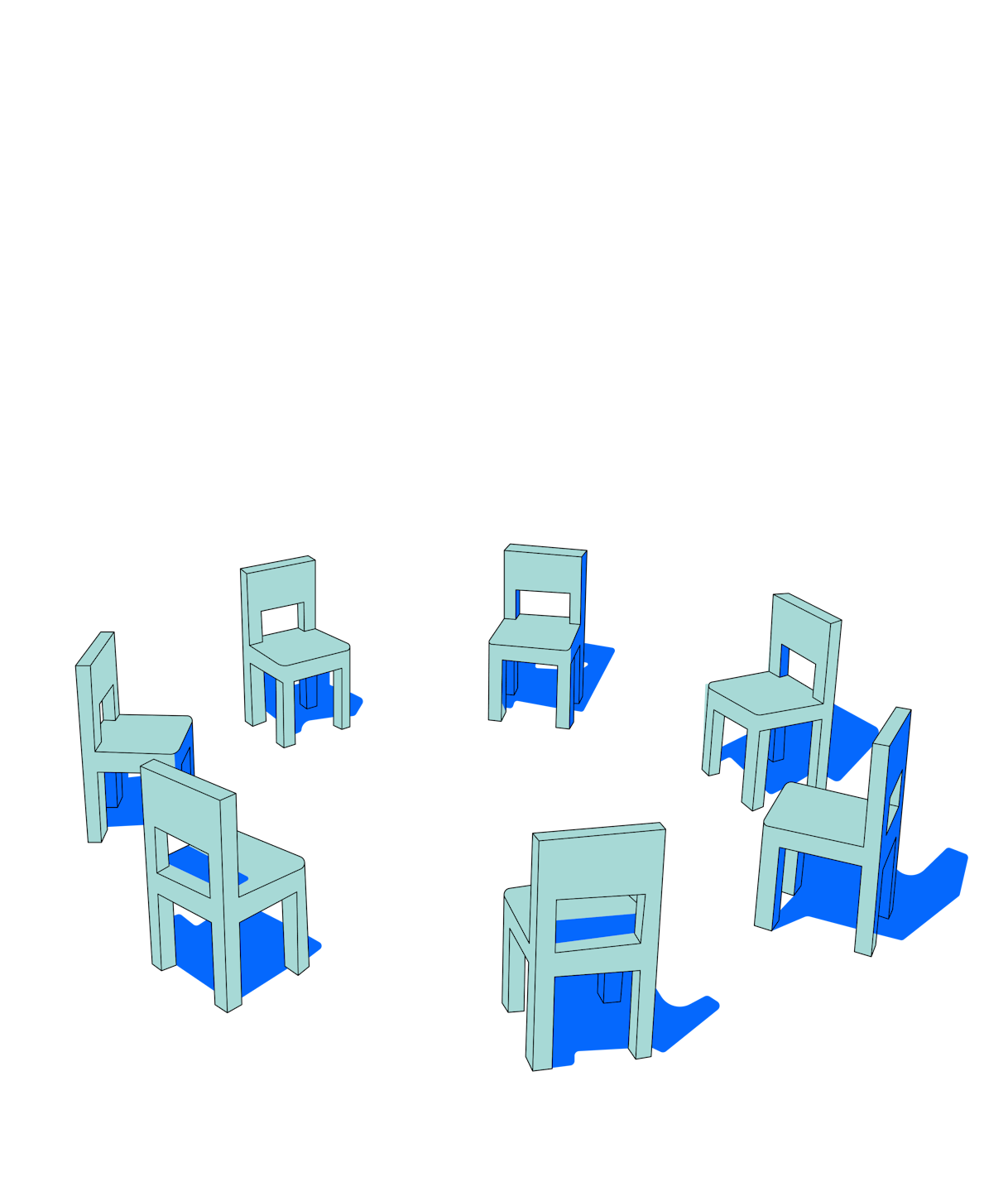

A Guide to Asking the Right Focus Group Questions

Moderated discussions with multiple participants to gather diverse opinions on a topic.

Maximize Your Research Potential

Experience why teams worldwide trust our Consumer & User Research solutions.

Book a Demo

- Request new password

- Create a new account

30 Essential Skills for the Qualitative Researcher

Welcome to the sage edge site for 30 essential skills for the qualitative researcher , second edition.

The second edition of 30 Essential Skills for the Qualitative Researcher provides practical, applied information for the novice qualitative researcher, addressing the "how" of conducting qualitative research in one brief guide. Author John W. Creswell and new co-author Johanna Creswell Báez draw on many examples from their own research experiences, sharing them throughout the book. The 30 listed skills are competencies that can help qualitative researchers conduct more thorough, more rigorous, and more efficient qualitative studies. Innovative chapters on thinking like a qualitative research and engaging with the emotional side of doing qualitative research go beyond the topics of a traditional research methods text and offer crucial support for qualitative practitioners. By starting with a strong foundation of a skills-based approach to qualitative research, readers can continue to develop their skills over the course of a career in research.

This revised edition updates skills to follow the research process, using new research from a wide variety of disciplines like social work and sociology as examples. Chapters on research designs now tie back explicitly to the five approaches to qualitative research so readers can better integrate their new skills into these designs. Additional figures and tables help readers better visualize data collection through focus groups and interviews and better organize and implement validity checks. The new edition provides further examples on how to incorporate reflexivity into a study, illuminating a challenging aspect of qualitative research. Information on writing habits now addresses co-authorship and provides more context and variation from the two authors.

This site features an array of free resources you can access anytime, anywhere.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge John W. Creswell and Johanna Creswell Báez for writing an excellent text. Special thanks are also due to Hope Cornelis for developing the resources on this site.

For instructors

Access resources that are only available to Faculty and Administrative Staff.

Want to explore the book further?

Order Review Copy

- Request new password

- Create a new account

30 Essential Skills for the Qualitative Researcher

Student resources, welcome to the companion website.

This site is intended to enhance your use of 30 Essential Skills for the Qualitative Researcher by John W. Creswell. Please note that all the materials on this site are especially geared toward maximizing your understanding of the material.

30 Essential Skills for the Qualitative Researcher fills a gap in introductory literature on qualitative inquiry by providing practical "how-to" information for beginning researchers in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. Author John W. Creswell draws on years of teaching, writing, and conducting his own projects to offer effective techniques and procedures with many applied examples from research design, qualitative inquiry, and mixed methods. Creswell defines what a skill is, and acknowledges that while there may be more than 30 that an individual will use and perfect, the skills presented in this book are crucial for a new qualitative researcher starting a qualitative project.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge John W. Creswell for writing an excellent text and for reviewing the assets on this site. Special thanks are also due to Tim Guetterman of University of Michigan for creating the ancillaries on this site.

For instructors

Access resources that are only available to Faculty and Administrative Staff.

Want to explore the book further?

Order Review Copy

What are Key Skills Qualitative Researchers Need?

- March 18, 2022

Qualitative research is a burgeoning field, thanks to the proliferation of UX researchers, and the popularity of human-centered design and design thinking. For people who work in tech or are drowning in data at their jobs, qualitative research is a refreshing career path that puts people in-front of humans and helps researchers understand how people use products, think about marketing advertisements, interact with services, and perceive ideas.

Getting a job in qualitative research can be challenging, especially if one does not have the training or past experience in research. If you’ve ever asked yourself, “how do I become a qualitative researcher?” keep reading. This post will explore the key skills that qualitative researchers need — and this applies to people interested in working in user experience, qualitative consulting, or in marketing and ad agencies as a planner and strategist.

Key qualitative research skill #1: Curiosity

Qualitative research — regardless of the setting or whether it’s done online or in-person — involves studying human behavior. For those who didn’t study psychology, sociology, anthropology, or design, that’s okay. Qualitative research professionals often come to their careers through a variety of paths, even if it wasn’t through a traditional college major that focuses on human behavior.

A fundamental trait that qualitative researchers share is curiosity. Having a natural aptitude and disposition of curiosity is a huge asset for researchers, because qualitative research is all about inquiry: asking questions, observing, guiding, and wanting to dig deeper into understanding peoples’ behaviors and actions. Before you consider if qualitative research is the right career path for you, this is a good place to start: how curious are you? Is your curiosity a motivation that drives you to investigate, seek out solutions, and probe for better answers? If so, qualitative research can be a rewarding career.

Key qualitative research skill #2: The right training

Though many learn qualitative research on-the-job, by observing other researchers, there are still underlying skills, theory, and coaching that are crucial to develop the skillset and confidence required to be a great qualitative researcher. This requires training in how define and understand the study objectives; choose the right methodology; work with various stakeholders; write discussion guides; set up questions correctly when interviewing; build rapport with participants; moderate interviews (note that moderating groups versus individual interviews requires specific group training); communicate with clients key findings; and then distill the themes into an actionable report.

Whew! That’s a lot, right? Fortunately, there are specialized qualitative research training companies that focus on how to teach moderating skills, report writing skills, and the essential building blocks of qualitative research.

Key qualitative research skill #3: Experience in business, branding, marketing & technology design

Depending on where you desire to work in qualitative research, the best researchers come from backgrounds or have work experience in the underlying product output that is being studied. For example, those who have worked in marketing and advertising can explore jobs as ad agency planners and strategists; by being exposed to how marketing first works, and the teams and strategies involved, one can better understand how the research output will be used. Similarly, for those who have worked in tech, whether that’s through user interface design, software, or product management, they’ll have an advantage as a researcher since they understand the underlying components that go into technology. And for those who are working in-house for business products and services, having previous roles in business, or a degree in business, gives the researcher a foundation in how business strategy is applied.

Qualitative research is a growing field with a rewarding career — and great pay!

If you’ve read the above article and nodded your head throughout, qualitative research could be a great career path for you. If you’re interested in exploring research as a career option, start networking with researchers on sites like LinkedIn, and even see if you can job-shadow researchers at your current job. Another bonus is that researchers can make a great living! If you’re curious, have some business and strategy chops, and want to spend your time understanding how and why people make the decisions they do, you just may have found your next career move.

- Request Proposal

- Participate in Studies

- Our Leadership Team

- Our Approach

- Mission, Vision and Core Values

- Qualitative Research

- Quantitative Research

- Research Insights Workshops

- Customer Journey Mapping

- Millennial & Gen Z Market Research

- Market Research Services

- Our Clients

- InterQ Blog

- Why QR Works

- When to Use QR

- Types of QR

- Types of QR Careers

- Maximize Your Experience

- What is QRCA

- Star Volunteer Program

- Advance Program

- Thought Leaders

- QualPower Blog

- Young Professionals Central

- Inclusive Culture Committee

- VIEWS Magazine

- QRCA Merchandise

- Industry Partners

- Press Releases

- 2025 Annual Conference

- Worldwide Conference

- Past Conferences

- Board of Directors

- Past Presidents

- Get Involved

- Strategic Plan

- Membership Options

- Reasons to Join

- Annual Conference

- Advertising Opportunities

- Visit QualBook Directory

- Find a Qualitative Professional

- Find a Support Partner

- VIEWS Podcasts

- Qcast Webinars

- QualBook Directory

- Post a Career Opening

- Qualology Learning Hub

- Core Competencies

- Resource Library

- Member Forum

- New Member Benefits Overview

- Health Care Program

- Connections News

- Annual Reports

- Calendar of Events

- Qualitative Fundamentals Program

- International Market Research Day

- Ycast Webinars

- SIG Meetings

- Chapter Meetings

- My QRCA Advance

- My Member Pages

| Name: | |

| Category: | |

| Share: | |

| Core Competencies |

| In order to ensure that the industry and its practitioners continue to develop and mature, it is essential to have a shared and explicit definition of the specific elements that comprise “professional competency.” This set of eight Core Competencies (an update of our 2003 edition) outlines the key skills that are required to demonstrate proficiency as a qualitative research professional in today’s world, and QRCA urges the entire qualitative research industry to adopt these competencies as a significant step toward maintaining the level of professionalism in qualitative research. Want to Learn More?All content in QRCA’s Qualology Learning Hub is categorized into one or more of these areas. Click on any area above or below to learn more and link to relevant Qualology content. We further encourage the global qualitative research community to use these criteria to:

Thank you for your interest and happy learning! Core Competencies: Develop this Competency Research professionals competent in Research Design:

Research professionals competent in Project Management can:

Research professionals competent in Moderating/Facilitation can:

Research professionals competent in A nalysis and Reporting can:

Research professionals competent in Communication can:

Research professionals competent in Consulting can:

Research professionals competent in Business Practices can:

Research professionals competent in Professionalism can:

8/22/2024 August 2024 – Young Professionals Coffee Chat: Shift to Starting an Agency 8/23/2024 DC Chapter Virtual Meeting – AI Presentation 8/23/2024 Rocky Mountain Chapter: Into the Wild: Cultivating the Hidden Power of Intercepts QRCA 1601 Utica Ave S, Suite 213 Minneapolis, MN 55416 phone: 651. 290. 7491 fax: 651. 290. 2266 [email protected] Please share your ideas or concerns with QRCA leaders at [email protected]. Privacy Policy | Email Deliverability | Site Map | Sign Out © 2024 QRCA

This website is optimized for Firefox and Chrome. If you have difficulties using this site, see complete browser details . An official website of the United States government The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site. The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

Qualitative Research: Getting StartedIntroduction. As scientifically trained clinicians, pharmacists may be more familiar and comfortable with the concept of quantitative rather than qualitative research. Quantitative research can be defined as “the means for testing objective theories by examining the relationship among variables which in turn can be measured so that numbered data can be analyzed using statistical procedures”. 1 Pharmacists may have used such methods to carry out audits or surveys within their own practice settings; if so, they may have had a sense of “something missing” from their data. What is missing from quantitative research methods is the voice of the participant. In a quantitative study, large amounts of data can be collected about the number of people who hold certain attitudes toward their health and health care, but what qualitative study tells us is why people have thoughts and feelings that might affect the way they respond to that care and how it is given (in this way, qualitative and quantitative data are frequently complementary). Possibly the most important point about qualitative research is that its practitioners do not seek to generalize their findings to a wider population. Rather, they attempt to find examples of behaviour, to clarify the thoughts and feelings of study participants, and to interpret participants’ experiences of the phenomena of interest, in order to find explanations for human behaviour in a given context. WHAT IS QUALITATIVE RESEARCH?Much of the work of clinicians (including pharmacists) takes place within a social, clinical, or interpersonal context where statistical procedures and numeric data may be insufficient to capture how patients and health care professionals feel about patients’ care. Qualitative research involves asking participants about their experiences of things that happen in their lives. It enables researchers to obtain insights into what it feels like to be another person and to understand the world as another experiences it. Qualitative research was historically employed in fields such as sociology, history, and anthropology. 2 Miles and Huberman 2 said that qualitative data “are a source of well-grounded, rich descriptions and explanations of processes in identifiable local contexts. With qualitative data one can preserve chronological flow, see precisely which events lead to which consequences, and derive fruitful explanations.” Qualitative methods are concerned with how human behaviour can be explained, within the framework of the social structures in which that behaviour takes place. 3 So, in the context of health care, and hospital pharmacy in particular, researchers can, for example, explore how patients feel about their care, about their medicines, or indeed about “being a patient”. THE IMPORTANCE OF METHODOLOGYSmith 4 has described methodology as the “explanation of the approach, methods and procedures with some justification for their selection.” It is essential that researchers have robust theories that underpin the way they conduct their research—this is called “methodology”. It is also important for researchers to have a thorough understanding of various methodologies, to ensure alignment between their own positionality (i.e., bias or stance), research questions, and objectives. Clinicians may express reservations about the value or impact of qualitative research, given their perceptions that it is inherently subjective or biased, that it does not seek to be reproducible across different contexts, and that it does not produce generalizable findings. Other clinicians may express nervousness or hesitation about using qualitative methods, claiming that their previous “scientific” training and experience have not prepared them for the ambiguity and interpretative nature of qualitative data analysis. In both cases, these clinicians are depriving themselves of opportunities to understand complex or ambiguous situations, phenomena, or processes in a different way. Qualitative researchers generally begin their work by recognizing that the position (or world view) of the researcher exerts an enormous influence on the entire research enterprise. Whether explicitly understood and acknowledged or not, this world view shapes the way in which research questions are raised and framed, methods selected, data collected and analyzed, and results reported. 5 A broad range of different methods and methodologies are available within the qualitative tradition, and no single review paper can adequately capture the depth and nuance of these diverse options. Here, given space constraints, we highlight certain options for illustrative purposes only, emphasizing that they are only a sample of what may be available to you as a prospective qualitative researcher. We encourage you to continue your own study of this area to identify methods and methodologies suitable to your questions and needs, beyond those highlighted here. The following are some of the methodologies commonly used in qualitative research:

ROLE OF THE RESEARCHERFor any researcher, the starting point for research must be articulation of his or her research world view. This core feature of qualitative work is increasingly seen in quantitative research too: the explicit acknowledgement of one’s position, biases, and assumptions, so that readers can better understand the particular researcher. Reflexivity describes the processes whereby the act of engaging in research actually affects the process being studied, calling into question the notion of “detached objectivity”. Here, the researcher’s own subjectivity is as critical to the research process and output as any other variable. Applications of reflexivity may include participant-observer research, where the researcher is actually one of the participants in the process or situation being researched and must then examine it from these divergent perspectives. 12 Some researchers believe that objectivity is a myth and that attempts at impartiality will fail because human beings who happen to be researchers cannot isolate their own backgrounds and interests from the conduct of a study. 5 Rather than aspire to an unachievable goal of “objectivity”, it is better to simply be honest and transparent about one’s own subjectivities, allowing readers to draw their own conclusions about the interpretations that are presented through the research itself. For new (and experienced) qualitative researchers, an important first step is to step back and articulate your own underlying biases and assumptions. The following questions can help to begin this reflection process:

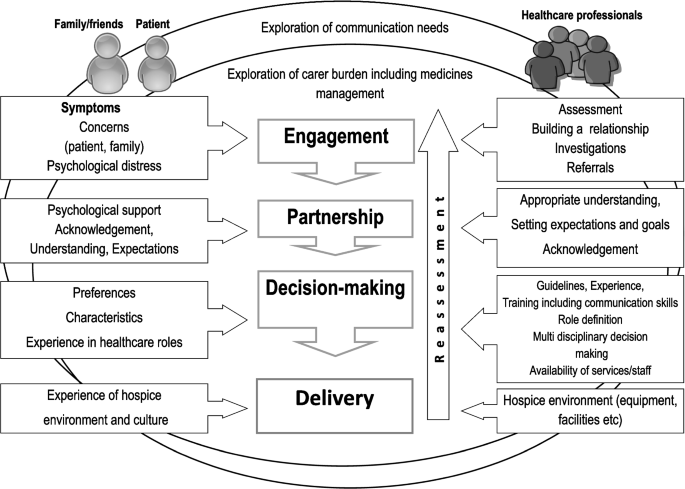

FROM FRAMEWORKS TO METHODSQualitative research methodology is not a single method, but instead offers a variety of different choices to researchers, according to specific parameters of topic, research question, participants, and settings. The method is the way you carry out your research within the paradigm of quantitative or qualitative research. Qualitative research is concerned with participants’ own experiences of a life event, and the aim is to interpret what participants have said in order to explain why they have said it. Thus, methods should be chosen that enable participants to express themselves openly and without constraint. The framework selected by the researcher to conduct the research may direct the project toward specific methods. From among the numerous methods used by qualitative researchers, we outline below the three most frequently encountered. DATA COLLECTIONPatton 12 has described an interview as “open-ended questions and probes yielding in-depth responses about people’s experiences, perceptions, opinions, feelings, and knowledge. Data consists of verbatim quotations and sufficient content/context to be interpretable”. Researchers may use a structured or unstructured interview approach. Structured interviews rely upon a predetermined list of questions framed algorithmically to guide the interviewer. This approach resists improvisation and following up on hunches, but has the advantage of facilitating consistency between participants. In contrast, unstructured or semistructured interviews may begin with some defined questions, but the interviewer has considerable latitude to adapt questions to the specific direction of responses, in an effort to allow for more intuitive and natural conversations between researchers and participants. Generally, you should continue to interview additional participants until you have saturated your field of interest, i.e., until you are not hearing anything new. The number of participants is therefore dependent on the richness of the data, though Miles and Huberman 2 suggested that more than 15 cases can make analysis complicated and “unwieldy”. Focus GroupsPatton 12 has described the focus group as a primary means of collecting qualitative data. In essence, focus groups are unstructured interviews with multiple participants, which allow participants and a facilitator to interact freely with one another and to build on ideas and conversation. This method allows for the collection of group-generated data, which can be a challenging experience. ObservationsPatton 12 described observation as a useful tool in both quantitative and qualitative research: “[it involves] descriptions of activities, behaviours, actions, conversations, interpersonal interactions, organization or community processes or any other aspect of observable human experience”. Observation is critical in both interviews and focus groups, as nonalignment between verbal and nonverbal data frequently can be the result of sarcasm, irony, or other conversational techniques that may be confusing or open to interpretation. Observation can also be used as a stand-alone tool for exploring participants’ experiences, whether or not the researcher is a participant in the process. Selecting the most appropriate and practical method is an important decision and must be taken carefully. Those unfamiliar with qualitative research may assume that “anyone” can interview, observe, or facilitate a focus group; however, it is important to recognize that the quality of data collected through qualitative methods is a direct reflection of the skills and competencies of the researcher. 13 The hardest thing to do during an interview is to sit back and listen to participants. They should be doing most of the talking—it is their perception of their own life-world that the researcher is trying to understand. Sophisticated interpersonal skills are required, in particular the ability to accurately interpret and respond to the nuanced behaviour of participants in various settings. More information about the collection of qualitative data may be found in the “Further Reading” section of this paper. It is essential that data gathered during interviews, focus groups, and observation sessions are stored in a retrievable format. The most accurate way to do this is by audio-recording (with the participants’ permission). Video-recording may be a useful tool for focus groups, because the body language of group members and how they interact can be missed with audio-recording alone. Recordings should be transcribed verbatim and checked for accuracy against the audio- or video-recording, and all personally identifiable information should be removed from the transcript. You are then ready to start your analysis. DATA ANALYSISRegardless of the research method used, the researcher must try to analyze or make sense of the participants’ narratives. This analysis can be done by coding sections of text, by writing down your thoughts in the margins of transcripts, or by making separate notes about the data collection. Coding is the process by which raw data (e.g., transcripts from interviews and focus groups or field notes from observations) are gradually converted into usable data through the identification of themes, concepts, or ideas that have some connection with each other. It may be that certain words or phrases are used by different participants, and these can be drawn together to allow the researcher an opportunity to focus findings in a more meaningful manner. The researcher will then give the words, phrases, or pieces of text meaningful names that exemplify what the participants are saying. This process is referred to as “theming”. Generating themes in an orderly fashion out of the chaos of transcripts or field notes can be a daunting task, particularly since it may involve many pages of raw data. Fortunately, sophisticated software programs such as NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd) now exist to support researchers in converting data into themes; familiarization with such software supports is of considerable benefit to researchers and is strongly recommended. Manual coding is possible with small and straightforward data sets, but the management of qualitative data is a complexity unto itself, one that is best addressed through technological and software support. There is both an art and a science to coding, and the second checking of themes from data is well advised (where feasible) to enhance the face validity of the work and to demonstrate reliability. Further reliability-enhancing mechanisms include “member checking”, where participants are given an opportunity to actually learn about and respond to the researchers’ preliminary analysis and coding of data. Careful documentation of various iterations of “coding trees” is important. These structures allow readers to understand how and why raw data were converted into a theme and what rules the researcher is using to govern inclusion or exclusion of specific data within or from a theme. Coding trees may be produced iteratively: after each interview, the researcher may immediately code and categorize data into themes to facilitate subsequent interviews and allow for probing with subsequent participants as necessary. At the end of the theming process, you will be in a position to tell the participants’ stories illustrated by quotations from your transcripts. For more information on different ways to manage qualitative data, see the “Further Reading” section at the end of this paper. ETHICAL ISSUESIn most circumstances, qualitative research involves human beings or the things that human beings produce (documents, notes, etc.). As a result, it is essential that such research be undertaken in a manner that places the safety, security, and needs of participants at the forefront. Although interviews, focus groups, and questionnaires may seem innocuous and “less dangerous” than taking blood samples, it is important to recognize that the way participants are represented in research can be significantly damaging. Try to put yourself in the shoes of the potential participants when designing your research and ask yourself these questions:

Where possible, attempting anonymization of data is strongly recommended, bearing in mind that true anonymization may be difficult, as participants can sometimes be recognized from their stories. Balancing the responsibility to report findings accurately and honestly with the potential harm to the participants involved can be challenging. Advice on the ethical considerations of research is generally available from research ethics boards and should be actively sought in these challenging situations. GETTING STARTEDPharmacists may be hesitant to embark on research involving qualitative methods because of a perceived lack of skills or confidence. Overcoming this barrier is the most important first step, as pharmacists can benefit from inclusion of qualitative methods in their research repertoire. Partnering with others who are more experienced and who can provide mentorship can be a valuable strategy. Reading reports of research studies that have utilized qualitative methods can provide insights and ideas for personal use; such papers are routinely included in traditional databases accessed by pharmacists. Engaging in dialogue with members of a research ethics board who have qualitative expertise can also provide useful assistance, as well as saving time during the ethics review process itself. The references at the end of this paper may provide some additional support to allow you to begin incorporating qualitative methods into your research. CONCLUSIONSQualitative research offers unique opportunities for understanding complex, nuanced situations where interpersonal ambiguity and multiple interpretations exist. Qualitative research may not provide definitive answers to such complex questions, but it can yield a better understanding and a springboard for further focused work. There are multiple frameworks, methods, and considerations involved in shaping effective qualitative research. In most cases, these begin with self-reflection and articulation of positionality by the researcher. For some, qualitative research may appear commonsensical and easy; for others, it may appear daunting, given its high reliance on direct participant– researcher interactions. For yet others, qualitative research may appear subjective, unscientific, and consequently unreliable. All these perspectives reflect a lack of understanding of how effective qualitative research actually occurs. When undertaken in a rigorous manner, qualitative research provides unique opportunities for expanding our understanding of the social and clinical world that we inhabit. Further Reading

This article is the seventh in the CJHP Research Primer Series, an initiative of the CJHP Editorial Board and the CSHP Research Committee. The planned 2-year series is intended to appeal to relatively inexperienced researchers, with the goal of building research capacity among practising pharmacists. The articles, presenting simple but rigorous guidance to encourage and support novice researchers, are being solicited from authors with appropriate expertise. Previous article in this series: Bond CM. The research jigsaw: how to get started. Can J Hosp Pharm . 2014;67(1):28–30. Tully MP. Research: articulating questions, generating hypotheses, and choosing study designs. Can J Hosp Pharm . 2014;67(1):31–4. Loewen P. Ethical issues in pharmacy practice research: an introductory guide. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2014;67(2):133–7. Tsuyuki RT. Designing pharmacy practice research trials. Can J Hosp Pharm . 2014;67(3):226–9. Bresee LC. An introduction to developing surveys for pharmacy practice research. Can J Hosp Pharm . 2014;67(4):286–91. Gamble JM. An introduction to the fundamentals of cohort and case–control studies. Can J Hosp Pharm . 2014;67(5):366–72. Competing interests: None declared. Exploring Qualitative Researcher Skills: What They Are and How to Develop Them?Qualitative research entails gathering and evaluating non-numerical data to gain deeper insights into thoughts, concepts, and opinions. Recognizing essential qualitative research skills is crucial for understanding researchers’ needs and enhancing personal proficiency. Qualitative Research SkillsQualitative researchers engage in surveys, conversations, and interviews with subjects, emphasizing strong interpersonal and communication skills. What skills does qualitative researcher needs?1. framing questions. For instance, they could ask follow-up inquiries or seek clarification regarding a response. 2. ListeningKey components of good listening skills include actively responding to comments and queries, treating the speaker with respect, and showing curiosity to get deeper into their insights. 3. Data collection4. building rapport. Building rapport quickly is a critical skill in qualitative research as it makes a sense of comfort and ease for the subject during conversations. Techniques for establishing rapport include using non-threatening body language, mirroring the subject’s gestures, and maintaining an approachable demeanor that encourages easy communication. Tips for improving qualitative researcher skills1. enroll in training courses. For instance, sales training can enhance qualities like empathy, active listening, and effective communication, which are valuable in qualitative research. Additionally, consider courses that focus on technical aspects such as data gathering and sharing findings. 2. Consult with Experienced ResearchersLearning from professionals in the field can offer valuable insights into your strengths and areas for development. 3. Conduct Your Own Research4. create qualitative research projects. If you’re not currently engaged in a role involving qualitative research, take the initiative to create or accept projects that allow you to practice and enhance your skills. 5. Request FeedbackWhen conducting qualitative research, it’s beneficial to seek feedback from those you’ve engaged with. Workplace Qualitative Research SkillsQualitative research plays a crucial role in achieving various objectives within the workplace, such as enhancing relationships, presenting information effectively, and managing project logistics. Highlighting Qualitative Researcher Skills1. qualitative researcher skills for resume. Some examples of qualitative research skills to showcase on your resume include: 2. Qualitative Researcher Skills for Cover Letter3. qualitative researcher skills for job interview. During the interview, effectively demonstrate your qualitative researcher skills with real-life examples. Emphasizing your achievements will substantiate your qualitative researcher skills and showcase your ability to drive positive outcomes. Other articlesRelated posts, 100 research methodology key terms | definitions, how to create table of contents for research paper, how to control extraneous variables, research paper outline template: examples of structured research paper outlines, alternative hypothesis: types and examples, dependent variable in research: examples, what is an independent variable, how to write a conclusion for research paper | examples, example of abstract for your research paper: tips, dos, and don’ts, journal publication ethics for authors. Qualitative Research DefinitionQualitative research methods and examples, advantages and disadvantages of qualitative approaches, qualitative vs. quantitative research, showing qualitative research skills on resumes, what is qualitative research methods and examples.

Forage puts students first. Our blog articles are written independently by our editorial team. They have not been paid for or sponsored by our partners. See our full editorial guidelines . Table of ContentsQualitative research seeks to understand people’s experiences and perspectives by studying social organizations and human behavior. Data in qualitative studies focuses on people’s beliefs and emotional responses. Qualitative data is especially helpful when a company wants to know how customers feel about a product or service, such as in user experience (UX) design or marketing . Researchers use qualitative approaches to “determine answers to research questions on human behavior and the cultural values that drive our thinking and behavior,” says Margaret J. King, director at The Center for Cultural Studies & Analysis in Philadelphia. Data in qualitative research typically can’t be assessed mathematically — the data is not sets of numbers or quantifiable information. Rather, it’s collections of images, words, notes on behaviors, descriptions of emotions, and historical context. Data is collected through observations, interviews, surveys, focus groups, and secondary research. However, a qualitative study needs a “clear research question at its base,” notes King, and the research needs to be “observed, categorized, compared, and evaluated (along a scale or by a typology chart) by reference to a baseline in order to determine an outcome with value as new and reliable information.”  Quantium Data AnalyticsExplore the power of data and its ability to power breakthrough possibilities for individuals, organisations and societies with this free job simulation from Quantium. Avg. Time: 4 to 5 hours Skills you’ll build: Data validation, data visualisation, data wrangling, programming, data analysis, commercial thinking, statistical testing, presentation skills  Who Uses Qualitative Research?Researchers in social sciences and humanities often use qualitative research methods, especially in specific areas of study like anthropology, history, education, and sociology. Qualitative methods are also applicable in business, technology , and marketing spaces. For example, product managers use qualitative research to understand how target audiences respond to their products. They may use focus groups to gain insights from potential customers on product prototypes and improvements or surveys from existing customers to understand what changes users want to see. Other careers that may involve qualitative research include: