Top 20 Qualitative Research Interview Questions & Answers

Master your responses to Qualitative Research related interview questions with our example questions and answers. Boost your chances of landing the job by learning how to effectively communicate your Qualitative Research capabilities.

Diving into the intricacies of human behavior, thoughts, and experiences is the lifeblood of qualitative research. As a professional in this nuanced field, you are well-versed in the art of gathering rich, descriptive data that can provide deep insights into complex issues. Now, as you prepare to take on new challenges in your career, it’s time to demonstrate not only your expertise in qualitative methodologies but also your ability to think critically and adapt to various research contexts.

Whether you’re interviewing for an academic position, a role within a market research firm, or any other setting where qualitative skills are prized, being prepared with thoughtful responses to potential interview questions can set you apart from other candidates. In this article, we will discuss some of the most common questions asked during interviews for qualitative research roles, offering guidance on how best to articulate your experience and approach to prospective employers.

Common Qualitative Research Interview Questions

1. how do you ensure the credibility of your data in qualitative research.

Ensuring credibility in qualitative research is crucial for the trustworthiness of the findings. By asking about methodological rigor, the interviewer is assessing a candidate’s understanding of strategies such as triangulation, member checking, and maintaining a detailed audit trail, which are essential for substantiating the integrity of qualitative data.

When responding to this question, you should articulate a multi-faceted approach to establishing credibility. Begin by highlighting your understanding of the importance of a well-defined research design and data collection strategy. Explain how you incorporate methods like triangulation, using multiple data sources or perspectives to confirm the consistency of the information obtained. Discuss your process for member checking—obtaining feedback on your findings from the participants themselves—to add another layer of validation. Mention your dedication to keeping a comprehensive audit trail, documenting all stages of the research process, which enables peer scrutiny and adds to the transparency of the study. Emphasize your ongoing commitment to reflexivity, where you continually examine your biases and influence on the research. Through this detailed explanation, you demonstrate a conscientious and systematic approach to safeguarding the credibility of your qualitative research.

Example: “ To ensure the credibility of data in qualitative research, I employ a rigorous research design that is both systematic and reflective. Initially, I establish clear protocols for data collection, which includes in-depth interviews, focus groups, and observations, ensuring that each method is well-suited to the research questions. To enhance the validity of the findings, I apply triangulation, drawing on various data sources, theoretical frameworks, and methodologies to cross-verify the information and interpretations.

During the analysis phase, member checking is a critical step, where I return to participants with a summary of the findings to validate the accuracy and resonance of the interpreted data with their experiences. This not only strengthens the credibility of the results but also enriches the data by incorporating participant insights. Furthermore, I maintain a comprehensive audit trail, meticulously documenting the research process, decisions made, and data transformations. This transparency allows for peer review and ensures that the research can be followed and critiqued by others in the field.

Lastly, reflexivity is integral to my practice. I continuously engage in self-reflection to understand and articulate my biases and assumptions and how they may influence the research process. By doing so, I can mitigate potential impacts on the data and interpretations, ensuring that the findings are a credible representation of the phenomenon under investigation.”

2. Describe a situation where you had to adapt your research methodology due to unforeseen challenges.

When unexpected variables arise, adaptability in research design is vital to maintain the integrity and validity of the study. This question seeks to assess a candidate’s problem-solving skills, flexibility, and resilience in the face of research challenges.

When responding, share a specific instance where you encountered a challenge that impacted your research methodology. Detail the nature of the challenge, the thought process behind your decision to adapt, the steps you took to revise your approach, and the outcome of those changes. Emphasize your critical thinking, your ability to consult relevant literature or peers if necessary, and how your adaptability contributed to the overall success or learning experience of the research project.

Example: “ In a recent qualitative study on community health practices, I encountered a significant challenge when the planned in-person interviews became unfeasible due to a sudden public health concern. The initial methodology was designed around face-to-face interactions to capture rich, detailed narratives. However, with participant safety as a priority, I quickly pivoted to remote data collection methods. After reviewing relevant literature on virtual qualitative research, I adapted the protocol to include video conferencing and phone interviews, ensuring I could still engage deeply with participants. This adaptation required a reevaluation of our ethical considerations, particularly around confidentiality and informed consent in digital formats.

The shift to remote interviews introduced concerns about potential biases, as the change might exclude individuals without access to the necessary technology. To mitigate this, I also offered the option of asynchronous voice recordings or email responses as a means to participate. This inclusive approach not only preserved the integrity of the study but also revealed an unexpected layer of data regarding digital literacy and access in the community. The study’s findings were robust, and the methodology adaptation was reflected upon in the final report, contributing to the discourse on the flexibility and resilience of qualitative research in dynamic contexts.”

3. What strategies do you employ for effective participant observation?

For effective participant observation, a balance between immersion and detachment is necessary to gather in-depth understanding without influencing the natural setting. This method allows the researcher to collect rich, contextual data that surveys or structured interviews might miss.

When responding to this question, highlight your ability to blend in with the participant group to minimize your impact on their behavior. Discuss your skills in active listening, detailed note-taking, and ethical considerations such as informed consent and maintaining confidentiality. Mention any techniques you use to reflect on your observations critically and how you ensure that your presence does not alter the dynamics of the group you are studying. It’s also effective to provide examples from past research where your participant observation led to valuable insights that informed your study’s findings.

Example: “ In participant observation, my primary strategy is to achieve a balance between immersion and detachment. I immerse myself in the environment to gain a deep understanding of the context and participants’ perspectives, while remaining sufficiently detached to observe and analyze behaviors and interactions objectively. To blend in, I adapt to the cultural norms and social cues of the group, which often involves a period of learning and adjustment to minimize my impact on their behavior.

Active listening is central to my approach, allowing me to capture the subtleties of communication beyond verbal exchanges. I complement this with meticulous note-taking, often employing a system of shorthand that enables me to record details without disrupting the flow of interaction. Ethically, I prioritize informed consent and confidentiality, ensuring participants are aware of my role and the study’s purpose. After observations, I engage in reflexive practice, critically examining my own biases and influence on the research setting. This reflexivity was instrumental in a past project where my awareness of my impact on group dynamics led to the discovery of underlying power structures that were not immediately apparent, significantly enriching the study’s findings.”

4. In what ways do you maintain ethical standards while conducting in-depth interviews?

Maintaining ethical standards during in-depth interviews involves respecting participant confidentiality, ensuring informed consent, and being sensitive to power dynamics. Ethical practice in this context is not only about adhering to institutional guidelines but also about fostering an environment where interviewees feel respected and understood.

When responding to this question, it’s vital to articulate a clear understanding of ethical frameworks such as confidentiality and informed consent. Describe specific strategies you employ, such as anonymizing data, obtaining consent through clear communication about the study’s purpose and the participant’s role, and ensuring the interviewee’s comfort and safety during the conversation. Highlight any training or certifications you’ve received in ethical research practices and give examples from past research experiences where you navigated ethical dilemmas successfully. This approach demonstrates your commitment to integrity in the research process and your ability to protect the well-being of your subjects.

Example: “ Maintaining ethical standards during in-depth interviews is paramount to the integrity of the research process. I ensure that all participants are fully aware of the study’s purpose, their role within it, and the ways in which their data will be used. This is achieved through a clear and comprehensive informed consent process. I always provide participants with the option to withdraw from the study at any point without penalty.

To safeguard confidentiality, I employ strategies such as anonymizing data and using secure storage methods. I am also attentive to the comfort and safety of interviewees, creating a respectful and non-threatening interview environment. In situations where sensitive topics may arise, I am trained to handle these with the necessary care and professionalism. For instance, in a past study involving vulnerable populations, I implemented additional privacy measures and worked closely with an ethics review board to navigate the complexities of the research context. My approach is always to prioritize the dignity and rights of the participants, adhering to ethical guidelines and best practices established in the field.”

5. How do you approach coding textual data without personal biases influencing outcomes?

When an interviewer poses a question about coding textual data free from personal biases, they are probing your ability to maintain objectivity and adhere to methodological rigor. This question tests your understanding of qualitative analysis techniques and your awareness of the researcher’s potential to skew data interpretation.

When responding, it’s essential to articulate your familiarity with established coding procedures such as open, axial, or thematic coding. Emphasize your systematic approach to data analysis, which might include multiple rounds of coding, peer debriefing, and maintaining a reflexive journal. Discuss the importance of bracketing your preconceptions during data analysis and how you would seek to validate your coding through methods such as triangulation or member checking. Your answer should convey a balance between a structured approach to coding and an openness to the data’s nuances, demonstrating your commitment to producing unbiased and trustworthy qualitative research findings.

Example: “ In approaching textual data coding, I adhere to a structured yet flexible methodology that mitigates personal bias. Initially, I engage in open coding to categorize data based on its manifest content, allowing patterns to emerge organically. This is followed by axial coding, where I explore connections between categories, and if applicable, thematic coding to identify overarching themes. Throughout this process, I maintain a reflexive journal to document my thought process and potential biases, ensuring transparency and self-awareness.

To ensure the reliability of my coding, I employ peer debriefing sessions, where colleagues scrutinize my coding decisions, challenging assumptions and offering alternative interpretations. This collaborative scrutiny helps to counteract any personal biases that might have crept into the analysis. Additionally, I utilize methods such as triangulation, comparing data across different sources, and member checking, soliciting feedback from participants on the accuracy of the coded data. These strategies collectively serve to validate the coding process and ensure that the findings are a credible representation of the data, rather than a reflection of my preconceptions.”

6. What is your experience with utilizing grounded theory in qualitative studies?

Grounded theory is a systematic methodology that operates almost in a reverse fashion from traditional research. Employers ask about your experience with grounded theory to assess your ability to conduct research that is flexible and adaptable to the data.

When responding, you should outline specific studies or projects where you’ve applied grounded theory. Discuss the nature of the data you worked with, the process of iterative data collection and analysis, and how you developed a theoretical framework as a result. Highlight any challenges you faced and how you overcame them, as well as the outcomes of your research. This will show your practical experience and your ability to engage deeply with qualitative data to extract meaningful theories and conclusions.

Example: “ In applying grounded theory to my qualitative studies, I have embraced its iterative approach to develop a theoretical framework grounded in empirical data. For instance, in a project exploring the coping mechanisms of individuals with chronic illnesses, I conducted in-depth interviews and focus groups, allowing the data to guide the research process. Through constant comparative analysis, I coded the data, identifying core categories and the relationships between them. This emergent coding process was central to refining and saturating the categories, ensuring the development of a robust theory that encapsulated the lived experiences of the participants.

Challenges such as data saturation and ensuring theoretical sensitivity were navigated by maintaining a balance between openness to the data and guiding research questions. The iterative nature of grounded theory facilitated the identification of nuanced coping strategies that were not initially apparent, leading to a theory that emphasized the dynamic interplay between personal agency and social support. The outcome was a substantive theory that not only provided a deeper understanding of the participants’ experiences but also had practical implications for designing support systems for individuals with chronic conditions.”

7. Outline the steps you take when conducting a thematic analysis.

Thematic analysis is a method used to identify, analyze, and report patterns within data, and it requires a systematic approach to ensure validity and reliability. This question assesses whether a candidate can articulate a clear, methodical process that will yield insightful findings from qualitative data.

When responding, you should outline a step-by-step process that begins with familiarization with the data, whereby you immerse yourself in the details, taking notes and highlighting initial ideas. Proceed to generating initial codes across the entire dataset, which involves organizing data into meaningful groups. Then, search for themes by collating codes into potential themes and gathering all data relevant to each potential theme. Review these themes to ensure they work in relation to the coded extracts and the entire dataset, refining them as necessary. Define and name themes, which entails developing a detailed analysis of each theme and determining the essence of what each theme is about. Finally, report the findings, weaving the analytic narrative with vivid examples, within the context of existing literature and the research questions. This methodical response not only showcases your technical knowledge but also demonstrates an organized thought process and the ability to communicate complex procedures clearly.

Example: “ In conducting a thematic analysis, I begin by thoroughly immersing myself in the data, which involves meticulously reading and re-reading the content to gain a deep understanding of its breadth and depth. During this stage, I make extensive notes and begin to mark initial ideas that strike me as potentially significant.

Following familiarization, I generate initial codes systematically across the entire dataset. This coding process is both reflective and interpretative, as it requires me to identify and categorize data segments that are pertinent to the research questions. These codes are then used to organize the data into meaningful groups.

Next, I search for themes by examining the codes and considering how they may combine to form overarching themes. This involves collating all the coded data relevant to each potential theme and considering the interrelationships between codes, themes, and different levels of themes, which may include sub-themes.

The subsequent step is to review these themes, checking them against the dataset to ensure they accurately represent the data. This may involve collapsing some themes into each other, splitting others, and refining the specifics of each theme. The essence of this iterative process is to refine the themes so that they tell a coherent story about the data.

Once the themes are satisfactorily developed, I define and name them. This involves a detailed analysis of each theme and determining what aspect of the data each theme captures. I aim to articulate the nuances within each theme, identifying the story that each tells about the data, and considering how this relates to the broader research questions and literature.

Lastly, I report the findings, weaving together the thematic analysis narrative. This includes selecting vivid examples that compellingly illustrate each theme, discussing how the themes interconnect, and situating them within the context of existing literature and the research questions. This final write-up is not merely about summarizing the data but about telling a story that provides insights into the research topic.”

8. When is it appropriate to use focus groups rather than individual interviews, and why?

Choosing between focus groups and individual interviews depends on the research goals and the nature of the information sought. Focus groups excel in exploring complex behaviors, attitudes, and experiences through the dynamic interaction of participants.

When responding to this question, articulate the strengths of both methods, matching them to specific research scenarios. For focus groups, emphasize your ability to facilitate lively, guided discussions that leverage group dynamics to elicit a breadth of perspectives. For individual interviews, highlight your skill in creating a safe, confidential space where participants can share detailed, personal experiences. Demonstrate strategic thinking by discussing how you would decide on the most suitable method based on the research question, participant characteristics, and the type of data needed to achieve your research objectives.

Example: “ Focus groups are particularly apt when the research question benefits from the interaction among participants, as the group dynamics can stimulate memories, ideas, and experiences that might not surface in one-on-one interviews. They are valuable for exploring the range of opinions or feelings about a topic, allowing researchers to observe consensus formation, the diversity of perspectives, and the reasoning behind attitudes. This method is also efficient for gathering a breadth of data in a limited timeframe. However, it’s crucial to ensure that the topic is suitable for discussion in a group setting and that participants are comfortable speaking in front of others.

Conversely, individual interviews are more appropriate when the subject matter is sensitive or requires deep exploration of personal experiences. They provide a private space for participants to share detailed and nuanced insights without the influence of others, which can be particularly important when discussing topics that may not be openly talked about in a group. The method allows for a tailored approach, where the interviewer can adapt questions based on the participant’s responses, facilitating a depth of understanding that is harder to achieve in a group setting. The decision between the two methods ultimately hinges on the specific needs of the research, the nature of the topic, and the goals of the study.”

9. Detail how you would validate findings from a case study research design.

In case study research, validation is paramount to ensure that interpretations and conclusions are credible. A well-validated case study reinforces the rigor of the research method and bolsters the transferability of its findings to other contexts.

When responding to this question, detail your process, which might include triangulation, where you corroborate findings with multiple data sources or perspectives; member checking, which involves sharing your interpretations with participants for their input; and seeking peer debriefing, where colleagues critique the process and findings. Explain how these methods contribute to the dependability and confirmability of your research, showing that you are not just collecting data but actively engaging with it to construct a solid, defensible narrative.

Example: “ In validating findings from a case study research design, I employ a multi-faceted approach to ensure the dependability and confirmability of the research. Triangulation is a cornerstone of my validation process, where I corroborate evidence from various data sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents. This method allows for cross-validation and helps in constructing a robust narrative by revealing consistencies and discrepancies in the data.

Member checking is another essential step in my process. By sharing my interpretations with participants, I not only honor their perspectives but also enhance the credibility of the findings. This iterative process ensures that the conclusions drawn are reflective of the participants’ experiences and not solely based on my own interpretations.

Lastly, peer debriefing serves as a critical checkpoint. By engaging colleagues who critique the research process and findings, I open the study to external scrutiny, which helps in mitigating any potential biases and enhances the study’s rigor. These colleagues act as devil’s advocates, challenging assumptions and conclusions, thereby strengthening the study’s validity. Collectively, these strategies form a comprehensive approach to validating case study research, ensuring that the findings are well-substantiated and trustworthy.”

10. What measures do you take to ensure the transferability of your qualitative research findings?

When asked about ensuring transferability, the interviewer is assessing your ability to articulate the relevance of your findings beyond the specific context of your study. They want to know if you can critically appraise your research design and methodology.

To respond effectively, you should discuss the thoroughness of your data collection methods, such as purposive sampling, to gather diverse perspectives that enhance the depth of the data. Explain your engagement with participants and the setting to ensure a rich understanding of the phenomenon under study. Highlight your detailed documentation of the research process, including your reflexivity, to allow others to follow your footsteps analytically. Finally, speak about how you communicate the boundaries of your research applicability and how you encourage readers to consider the transferability of findings to their contexts through clear and comprehensive descriptions of your study’s context, participants, and assumptions.

Example: “ In ensuring the transferability of my qualitative research findings, I prioritize a robust and purposive sampling strategy that captures a wide range of perspectives relevant to the research question. This approach not only enriches the data but also provides a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon across varied contexts. By doing so, I lay a foundation for the findings to resonate with similar situations, allowing others to judge the applicability of the results to their own contexts.

I meticulously document the research process, including the setting, participant interactions, and my own reflexivity, to provide a transparent and detailed account of how conclusions were reached. This level of documentation serves as a roadmap for other researchers or practitioners to understand the intricacies of the study and evaluate the potential for transferability. Furthermore, I ensure that my findings are presented with a clear delineation of the context, including any cultural, temporal, or geographic nuances, and discuss the assumptions underpinning the study. By offering this rich, contextualized description, I invite readers to engage critically with the findings and assess their relevance to other settings, thus facilitating a responsible and informed application of the research outcomes.”

11. How do you determine when data saturation has been reached in your study?

Determining data saturation is crucial because it signals when additional data does not yield new insights, ensuring efficient use of resources without compromising the depth of understanding. This question is posed to assess a candidate’s experience and judgment in qualitative research.

When responding to this question, one should highlight their systematic approach to data collection and analysis. Discuss the iterative process of engaging with the data, constantly comparing new information with existing codes and themes. Explain how you monitor for emerging patterns and at what point these patterns become consistent and repeatable, indicating saturation. Mention any specific techniques or criteria you employ, such as the use of thematic analysis or constant comparison methods, and how you document the decision-making process to ensure transparency and validity in your research findings.

Example: “ In determining data saturation, I employ a rigorous and iterative approach to data collection and analysis. As I engage with the data, I continuously compare new information against existing codes and themes, carefully monitoring for the emergence of new patterns or insights. Saturation is approached when the data begins to yield redundant information, and no new themes or codes are emerging from the analysis.

I utilize techniques such as thematic analysis and constant comparison methods to ensure a systematic examination of the data. I document each step of the decision-making process, noting when additional data does not lead to new theme identification or when existing themes are fully fleshed out. This documentation not only serves as a checkpoint for determining saturation but also enhances the transparency and validity of the research findings. Through this meticulous process, I can confidently assert that data saturation has been achieved when the collected data offers a comprehensive understanding of the research phenomenon, with a rich and well-developed thematic structure that accurately reflects the research scope.”

12. Relate an instance where member checking significantly altered your research conclusions.

Member checking serves as a vital checkpoint to ensure accuracy, credibility, and resonance of the data with those it represents. It can reveal misunderstandings or even introduce new insights that substantially shift the study’s trajectory or outcomes.

When responding, candidates should recount a specific project where member checking made a pivotal difference in their findings. They should detail the initial conclusions, how the process of member checking was integrated, what feedback was received, and how it led to a re-evaluation or refinement of the research outcomes. This response showcases the candidate’s methodological rigor, flexibility in incorporating feedback, and dedication to producing research that authentically reflects the voices and experiences of the study’s participants.

Example: “ In a recent qualitative study on community responses to urban redevelopment, initial findings suggested broad support for the initiatives among residents. However, during the member checking phase, when participants reviewed and commented on the findings, a nuanced perspective emerged. Several participants highlighted that their apparent support was, in fact, resignation due to a lack of viable alternatives, rather than genuine enthusiasm for the redevelopment plans.

This feedback prompted a deeper dive into the data, revealing a pattern of resigned acceptance across a significant portion of the interviews. The conclusion was substantially revised to reflect this sentiment, emphasizing the complexity of community responses to redevelopment, which included both cautious optimism and skeptical resignation. This critical insight not only enriched the study’s validity but also had profound implications for policymakers interested in understanding the true sentiment of the affected communities.”

13. What are the key considerations when selecting a sample for phenomenological research?

The selection of a sample in phenomenological research is not about quantity but about the richness and relevance of the data that participants can provide. It requires an intimate knowledge of the research question and a deliberate choice to include participants who have experienced the phenomenon in question.

When responding to this question, it’s essential to emphasize the need for a purposeful sampling strategy that aims to capture a broad spectrum of perspectives on the phenomenon under study. Discuss the importance of sample diversity to ensure the findings are robust and reflect varied experiences. Mention the necessity of establishing clear criteria for participant selection and the willingness to adapt as the research progresses. Highlighting your commitment to ethical considerations, such as informed consent and the respectful treatment of participants’ information, will also demonstrate your thorough understanding of the nuances in qualitative sampling.

Example: “ In phenomenological research, the primary goal is to understand the essence of experiences concerning a particular phenomenon. Therefore, the key considerations for sample selection revolve around identifying individuals who have experienced the phenomenon of interest and can articulate their lived experiences. Purposeful sampling is essential to ensure that the participants chosen can provide rich, detailed accounts that contribute to a deep understanding of the phenomenon.

The diversity of the sample is also crucial. It is important to select participants who represent a range of perspectives within the phenomenon, not just a homogenous group. This might involve considering factors such as age, gender, socio-economic status, or other relevant characteristics that could influence their experiences. While the sample size in phenomenological studies is often small to allow for in-depth analysis, it is vital to ensure that the sample is varied enough to uncover a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon.

Lastly, ethical considerations are paramount. Participants must give informed consent, understanding the nature of the study and their role in it. The researcher must also be prepared to handle sensitive information with confidentiality and respect, ensuring the participants’ well-being is prioritized throughout the study. Adapting the sample selection criteria as the study progresses is also important, as initial interviews may reveal additional nuances that require the inclusion of further varied perspectives to fully grasp the phenomenon.”

14. Which software tools do you prefer for qualitative data analysis, and for what reasons?

The choice of software tools for qualitative data analysis reflects a researcher’s approach to data synthesis and interpretation. It also indicates their proficiency with technology and their ability to leverage sophisticated features to deepen insights.

When responding, it’s essential to discuss specific features of the software tools you prefer, such as coding capabilities, ease of data management, collaborative features, or the ability to handle large datasets. Explain how these features have enhanced your research outcomes in the past. For example, you might highlight the use of NVivo for its robust coding structure that helped you organize complex data efficiently or Atlas.ti for its intuitive interface and visualization tools that made it easier to detect emerging patterns. Your response should demonstrate your analytical thought process and your commitment to rigorous qualitative analysis.

Example: “ In my qualitative research endeavors, I have found NVivo to be an invaluable tool, primarily due to its advanced coding capabilities and its ability to manage large and complex datasets effectively. The node structure in NVivo facilitates a hierarchical organization of themes, which streamlines the coding process and enhances the reliability of the data analysis. This feature was particularly beneficial in a recent project where the depth and volume of textual data required a robust system to ensure consistency and comprehensiveness in theme development.

Another tool I frequently utilize is Atlas.ti, which stands out for its user-friendly interface and powerful visualization tools. These features are instrumental in identifying and illustrating relationships between themes, thereby enriching the interpretive depth of the analysis. The network views in Atlas.ti have enabled me to construct clear visual representations of the data interconnections, which not only supported my analytical narrative but also facilitated stakeholder understanding and engagement. The combination of these tools, leveraging their respective strengths, has consistently augmented the quality and impact of my qualitative research outcomes.”

15. How do you handle discrepancies between participants’ words and actions in ethnographic research?

Ethnographic research hinges on the researcher’s ability to interpret both verbal and non-verbal data to draw meaningful conclusions. This question allows the interviewer to assess a candidate’s methodological rigor and analytical skills.

When responding, it’s essential to emphasize your systematic approach to reconciling such discrepancies. Discuss the importance of context, the use of triangulation to corroborate findings through multiple data sources, and the strategies you employ to interpret and integrate conflicting information. Highlight your commitment to ethical research practices, the ways you ensure participant understanding and consent, and your experience with reflective practice to mitigate researcher bias. Showcasing your ability to remain flexible and responsive to the data, while maintaining a clear analytical framework, will demonstrate your proficiency in qualitative research.

Example: “ In ethnographic research, discrepancies between participants’ words and actions are not only common but also a valuable source of insight. When I encounter such discrepancies, I first consider the context in which they occur, as it often holds the key to understanding the divergence. Cultural norms, social pressures, or even the presence of the researcher can influence participants’ behaviors and self-reporting. I employ triangulation, utilizing multiple data sources such as interviews, observations, and relevant documents to construct a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomena at hand.

I also engage in reflective practice to examine my own biases and assumptions that might influence data interpretation. By maintaining a stance of cultural humility and being open to the participants’ perspectives, I can better understand the reasons behind their actions and words. When integrating conflicting information, I look for patterns and themes that can reconcile the differences, often finding that they reveal deeper complexities within the social context being studied. Ethical research practices, including ensuring participant understanding and consent, are paramount throughout this process, as they help maintain the integrity of both the data and the relationships with participants.”

16. What role does reflexivity play in your research process?

Reflexivity is an ongoing self-assessment that ensures research findings are not merely a reflection of the researcher’s preconceptions, thereby increasing the credibility and authenticity of the work.

When responding, illustrate your understanding of reflexivity with examples from past research experiences. Discuss how you have actively engaged in reflexivity by questioning your assumptions, how this shaped your research design, and the methods you employed to ensure that your findings were informed by the data rather than your personal beliefs. Demonstrate your commitment to ethical research practice by highlighting how you’ve maintained an open dialogue with your participants and peers to challenge and refine your interpretations.

Example: “ Reflexivity is a cornerstone of my qualitative research methodology, as it allows me to critically examine my own influence on the research process and outcomes. In practice, I maintain a reflexive journal throughout the research process, documenting my preconceptions, emotional responses, and decision-making rationales. This ongoing self-analysis ensures that I remain aware of my potential biases and the ways in which my background and perspectives might shape the data collection and analysis.

For instance, in a recent ethnographic study, I recognized my own cultural assumptions could affect participant interactions. To mitigate this, I incorporated member checking and peer debriefing as integral parts of the research cycle. By actively seeking feedback on my interpretations from both participants and fellow researchers, I was able to challenge my initial readings of the data and uncover deeper, more nuanced insights. This reflexive approach not only enriched the research findings but also upheld the integrity and credibility of the study, fostering a more authentic and ethical representation of the participants’ experiences.”

17. Describe a complex qualitative dataset you’ve managed and how you navigated its challenges.

Managing a complex qualitative dataset requires meticulous organization, a strong grasp of research methods, and the ability to discern patterns and themes amidst a sea of words and narratives. This question evaluates the candidate’s analytical and critical thinking skills.

When responding to this question, you should focus on a specific project that exemplifies your experience with complex qualitative data. Outline the scope of the data, the methods you used for organization and analysis, and the challenges you encountered—such as data coding, thematic saturation, or ensuring reliability and validity. Discuss the strategies you implemented to address these challenges, such as iterative coding, member checking, or triangulation. By providing concrete examples, you demonstrate not only your technical ability but also your methodological rigor and dedication to producing insightful, credible research findings.

Example: “ In a recent project, I managed a complex qualitative dataset that comprised over 50 in-depth interviews, several focus groups, and field notes from participant observation. The data was rich with nuanced perspectives on community health practices, but it presented challenges in ensuring thematic saturation and maintaining a systematic approach to coding across multiple researchers.

To navigate these challenges, I employed a rigorous iterative coding process, utilizing NVivo software to facilitate organization and analysis. Initially, I conducted a round of open coding to identify preliminary themes, followed by axial coding to explore the relationships between these themes. As the dataset was extensive, I also implemented a strategy of constant comparison to refine and merge codes, ensuring thematic saturation was achieved. To enhance the reliability and validity of our findings, I organized regular peer debriefing sessions, where the research team could discuss and resolve discrepancies in coding and interpretation. Additionally, I conducted member checks with a subset of participants, which not only enriched the data but also validated our thematic constructs. This meticulous approach enabled us to develop a robust thematic framework that accurately reflected the complexity of the community’s health practices and informed subsequent policy recommendations.”

18. How do you integrate quantitative data to enhance the richness of a primarily qualitative study?

Integrating quantitative data with qualitative research can add a layer of objectivity, enhance validity, and offer a scalable dimension to the findings. This mixed-methods approach can help in identifying outliers or anomalies in qualitative data.

When responding to this question, a candidate should articulate their understanding of both qualitative and quantitative research methodologies. They should discuss specific techniques such as triangulation, where quantitative data serves as a corroborative tool for qualitative findings, or embedded analysis, where quantitative data provides a backdrop for deep qualitative exploration. The response should also include practical examples of past research scenarios where the candidate successfully merged both data types to strengthen their study, highlighting their ability to create a symbiotic relationship between numbers and narratives for richer, more robust research outcomes.

Example: “ Integrating quantitative data into a qualitative study can significantly enhance the depth and credibility of the research findings. In my experience, I employ triangulation to ensure that themes emerging from qualitative data are not only rich in context but also empirically grounded. For instance, in a study exploring patient satisfaction, while qualitative interviews might reveal nuanced patient experiences, quantitative satisfaction scores can be used to validate and quantify the prevalence of these experiences across a larger population.

Furthermore, I often use quantitative data as a formative tool to guide the qualitative inquiry. By initially analyzing patterns in quantitative data, I can identify areas that require a deeper understanding through qualitative methods. For example, if a survey indicates a trend in consumer behavior, follow-up interviews or focus groups can explore the motivations behind that trend. This embedded analysis approach ensures that qualitative findings are not only contextually informed but also quantitatively relevant, leading to a more comprehensive understanding of the research question.”

19. What is your rationale for choosing narrative inquiry over other qualitative methods in storytelling contexts?

Narrative inquiry delves into individual stories to find broader truths and patterns. This method captures the richness of how people perceive and make sense of their lives, revealing the interplay of various factors in shaping narratives.

When responding, articulate your understanding of narrative inquiry, emphasizing its strengths in capturing lived experiences and its ability to provide a detailed, insider’s view of a phenomenon. Highlight your knowledge of how narrative inquiry can uncover the nuances of storytelling, such as the role of language, emotions, and context, which are essential for a deep understanding of the subject matter. Demonstrate your ability to choose an appropriate research method based on the research question, objectives, and the nature of the data you aim to collect.

Example: “ Narrative inquiry is a powerful qualitative method that aligns exceptionally well with the exploration of storytelling contexts due to its focus on the richness of personal experience and the construction of meaning. By delving into individuals’ stories, narrative inquiry allows researchers to capture the complexities of lived experiences, which are often embedded with emotions, cultural values, and temporal elements that other methods may not fully grasp. The longitudinal nature of narrative inquiry, where stories can be collected and analyzed over time, also offers a dynamic perspective on how narratives evolve, intersect, and influence the storyteller’s identity and worldview.

In choosing narrative inquiry, one is committing to a methodological approach that honors the subjectivity and co-construction of knowledge between the researcher and participants. This approach is particularly adept at uncovering the layers of language use, symbolism, and the interplay of narratives with broader societal discourses. It is this depth and nuance that makes narrative inquiry the method of choice when the research aim is not just to catalog events but to understand the profound implications of storytelling on individual and collective levels. The method’s flexibility in accommodating different narrative forms – be it oral, written, or visual – further underscores its suitability for research that seeks to holistically capture the essence of storytelling within its natural context.”

20. How do you address potential power dynamics that may influence a participant’s responses during interviews?

Recognizing and mitigating the influence of power dynamics is essential to maintain the integrity of the data collected in qualitative research, ensuring that findings reflect the participants’ genuine perspectives.

When responding to this question, one should emphasize their awareness of such dynamics and articulate strategies to minimize their impact. This could include techniques like establishing rapport, using neutral language, ensuring confidentiality, and employing reflexivity—being mindful of one’s own influence on the conversation. Furthermore, demonstrating an understanding of how to create a safe space for open dialogue and acknowledging the importance of participant empowerment can convey a commitment to ethical and effective qualitative research practices.

Example: “ In addressing potential power dynamics, my approach begins with the conscious effort to create an environment of trust and safety. I employ active listening and empathetic engagement to establish rapport, which helps to level the conversational field. I am meticulous in using neutral, non-leading language to avoid inadvertently imposing my own assumptions or perspectives on participants. This is complemented by an emphasis on the voluntary nature of participation and the assurance of confidentiality, which together foster a space where participants feel secure in sharing their authentic experiences.

Reflexivity is a cornerstone of my practice; I continuously self-assess and acknowledge my positionality and its potential influence on the research process. By engaging in this critical self-reflection, I am better equipped to recognize and mitigate any power imbalances that may arise. Moreover, I strive to empower participants by validating their narratives and ensuring that the interview process is not just extractive but also offers them a platform to be heard and to contribute meaningfully to the research. This balanced approach not only enriches the data quality but also adheres to the ethical standards that underpin responsible qualitative research.”

Top 20 Stakeholder Interview Questions & Answers

Top 20 multicultural interview questions & answers, you may also be interested in..., top 20 quantitative interview questions & answers, top 20 organizational interview questions & answers, top 20 verbal communication interview questions & answers, top 20 technical design interview questions & answers.

How to conduct qualitative interviews (tips and best practices)

Last updated

18 May 2023

Reviewed by

Miroslav Damyanov

However, conducting qualitative interviews can be challenging, even for seasoned researchers. Poorly conducted interviews can lead to inaccurate or incomplete data, significantly compromising the validity and reliability of your research findings.

When planning to conduct qualitative interviews, you must adequately prepare yourself to get the most out of your data. Fortunately, there are specific tips and best practices that can help you conduct qualitative interviews effectively.

- What is a qualitative interview?

A qualitative interview is a research technique used to gather in-depth information about people's experiences, attitudes, beliefs, and perceptions. Unlike a structured questionnaire or survey, a qualitative interview is a flexible, conversational approach that allows the interviewer to delve into the interviewee's responses and explore their insights and experiences.

In a qualitative interview, the researcher typically develops a set of open-ended questions that provide a framework for the conversation. However, the interviewer can also adapt to the interviewee's responses and ask follow-up questions to understand their experiences and views better.

- How to conduct interviews in qualitative research

Conducting interviews involves a well-planned and deliberate process to collect accurate and valid data.

Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to conduct interviews in qualitative research, broken down into three stages:

1. Before the interview

The first step in conducting a qualitative interview is determining your research question . This will help you identify the type of participants you need to recruit . Once you have your research question, you can start recruiting participants by identifying potential candidates and contacting them to gauge their interest in participating in the study.

After that, it's time to develop your interview questions. These should be open-ended questions that will elicit detailed responses from participants. You'll also need to get consent from the participants, ideally in writing, to ensure that they understand the purpose of the study and their rights as participants. Finally, choose a comfortable and private location to conduct the interview and prepare the interview guide.

2. During the interview

Start by introducing yourself and explaining the purpose of the study. Establish a rapport by putting the participants at ease and making them feel comfortable. Use the interview guide to ask the questions, but be flexible and ask follow-up questions to gain more insight into the participants' responses.

Take notes during the interview, and ask permission to record the interview for transcription purposes. Be mindful of the time, and cover all the questions in the interview guide.

3. After the interview

Once the interview is over, transcribe the interview if you recorded it. If you took notes, review and organize them to make sure you capture all the important information. Then, analyze the data you collected by identifying common themes and patterns. Use the findings to answer your research question.

Finally, debrief with the participants to thank them for their time, provide feedback on the study, and answer any questions they may have.

Free AI content analysis generator

Make sense of your research by automatically summarizing key takeaways through our free content analysis tool.

- What kinds of questions should you ask in a qualitative interview?

Qualitative interviews involve asking questions that encourage participants to share their experiences, opinions, and perspectives on a particular topic. These questions are designed to elicit detailed and nuanced responses rather than simple yes or no answers.

Effective questions in a qualitative interview are generally open-ended and non-leading. They avoid presuppositions or assumptions about the participant's experience and allow them to share their views in their own words.

In customer research , you might ask questions such as:

What motivated you to choose our product/service over our competitors?

How did you first learn about our product/service?

Can you walk me through your experience with our product/service?

What improvements or changes would you suggest for our product/service?

Have you recommended our product/service to others, and if so, why?

The key is to ask questions relevant to the research topic and allow participants to share their experiences meaningfully and informally.

- How to determine the right qualitative interview participants

Choosing the right participants for a qualitative interview is a crucial step in ensuring the success and validity of the research . You need to consider several factors to determine the right participants for a qualitative interview. These may include:

Relevant experiences : Participants should have experiences related to the research topic that can provide valuable insights.

Diversity : Aim to include diverse participants to ensure the study's findings are representative and inclusive.

Access : Identify participants who are accessible and willing to participate in the study.

Informed consent : Participants should be fully informed about the study's purpose, methods, and potential risks and benefits and be allowed to provide informed consent.

You can use various recruitment methods, such as posting ads in relevant forums, contacting community organizations or social media groups, or using purposive sampling to identify participants who meet specific criteria.

- How to make qualitative interview subjects comfortable

Making participants comfortable during a qualitative interview is essential to obtain rich, detailed data. Participants are more likely to share their experiences openly when they feel at ease and not judged.

Here are some ways to make interview subjects comfortable:

Explain the purpose of the study

Start the interview by explaining the research topic and its importance. The goal is to give participants a sense of what to expect.

Create a comfortable environment

Conduct the interview in a quiet, private space where the participant feels comfortable. Turn off any unnecessary electronics that can create distractions. Ensure your equipment works well ahead of time. Arrive at the interview on time. If you conduct a remote interview, turn on your camera and mute all notetakers and observers.

Build rapport

Greet the participant warmly and introduce yourself. Show interest in their responses and thank them for their time.

Use open-ended questions

Ask questions that encourage participants to elaborate on their thoughts and experiences.

Listen attentively

Resist the urge to multitask . Pay attention to the participant's responses, nod your head, or make supportive comments to show you’re interested in their answers. Avoid interrupting them.

Avoid judgment

Show respect and don't judge the participant's views or experiences. Allow the participant to speak freely without feeling judged or ridiculed.

Offer breaks

If needed, offer breaks during the interview, especially if the topic is sensitive or emotional.

Creating a comfortable environment and establishing rapport with the participant fosters an atmosphere of trust and encourages open communication. This helps participants feel at ease and willing to share their experiences.

- How to analyze a qualitative interview

Analyzing a qualitative interview involves a systematic process of examining the data collected to identify patterns, themes, and meanings that emerge from the responses.

Here are some steps on how to analyze a qualitative interview:

1. Transcription

The first step is transcribing the interview into text format to have a written record of the conversation. This step is essential to ensure that you can refer back to the interview data and identify the important aspects of the interview.

2. Data reduction

Once you’ve transcribed the interview, read through it to identify key themes, patterns, and phrases emerging from the data. This process involves reducing the data into more manageable pieces you can easily analyze.

The next step is to code the data by labeling sections of the text with descriptive words or phrases that reflect the data's content. Coding helps identify key themes and patterns from the interview data.

4. Categorization

After coding, you should group the codes into categories based on their similarities. This process helps to identify overarching themes or sub-themes that emerge from the data.

5. Interpretation

You should then interpret the themes and sub-themes by identifying relationships, contradictions, and meanings that emerge from the data. Interpretation involves analyzing the themes in the context of the research question .

6. Comparison

The next step is comparing the data across participants or groups to identify similarities and differences. This step helps to ensure that the findings aren’t just specific to one participant but can be generalized to the wider population.

7. Triangulation

To ensure the findings are valid and reliable, you should use triangulation by comparing the findings with other sources, such as observations or interview data.

8. Synthesis

The final step is synthesizing the findings by summarizing the key themes and presenting them clearly and concisely. This step involves writing a report that presents the findings in a way that is easy to understand, using quotes and examples from the interview data to illustrate the themes.

- Tips for transcribing a qualitative interview

Transcribing a qualitative interview is a crucial step in the research process. It involves converting the audio or video recording of the interview into written text.

Here are some tips for transcribing a qualitative interview:

Use transcription software

Transcription software can save time and increase accuracy by automatically transcribing audio or video recordings.

Listen carefully

When manually transcribing, listen carefully to the recording to ensure clarity. Pause and rewind the recording as necessary.

Use appropriate formatting

Use a consistent format for transcribing, such as marking pauses, overlaps, and interruptions. Indicate non-verbal cues such as laughter, sighs, or changes in tone.

Edit for clarity

Edit the transcription to ensure clarity and readability. Use standard grammar and punctuation, correct misspellings, and remove filler words like "um" and "ah."

Proofread and edit

Verify the accuracy of the transcription by listening to the recording again and reviewing the notes taken during the interview.

Use timestamps

Add timestamps to the transcription to reference specific interview sections.

Transcribing a qualitative interview can be time-consuming, but it’s essential to ensure the accuracy of the data collected. Following these tips can produce high-quality transcriptions useful for analysis and reporting.

- Why are interview techniques in qualitative research effective?

Unlike quantitative research methods, which rely on numerical data, qualitative research seeks to understand the richness and complexity of human experiences and perspectives.

Interview techniques involve asking open-ended questions that allow participants to express their views and share their stories in their own words. This approach can help researchers to uncover unexpected or surprising insights that may not have been discovered through other research methods.

Interview techniques also allow researchers to establish rapport with participants, creating a comfortable and safe space for them to share their experiences. This can lead to a deeper level of trust and candor, leading to more honest and authentic responses.

- What are the weaknesses of qualitative interviews?

Qualitative interviews are an excellent research approach when used properly, but they have their drawbacks.

The weaknesses of qualitative interviews include the following:

Subjectivity and personal biases

Qualitative interviews rely on the researcher's interpretation of the interviewee's responses. The researcher's biases or preconceptions can affect how the questions are framed and how the responses are interpreted, which can influence results.

Small sample size

The sample size in qualitative interviews is often small, which can limit the generalizability of the results to the larger population.

Data quality

The quality of data collected during interviews can be affected by various factors, such as the interviewee's mood, the setting of the interview, and the interviewer's skills and experience.

Socially desirable responses

Interviewees may provide responses that they believe are socially acceptable rather than truthful or genuine.

Conducting qualitative interviews can be expensive, especially if the researcher must travel to different locations to conduct the interviews.

Time-consuming

The data analysis process can be time-consuming and labor-intensive, as researchers need to transcribe and analyze the data manually.

Despite these weaknesses, qualitative interviews remain a valuable research tool . You can take steps to mitigate the impact of these weaknesses by incorporating the perspectives of other researchers or participants in the analysis process, using multiple data sources , and critically analyzing your biases and assumptions.

Mastering the art of qualitative interviews is an essential skill for businesses looking to gain deep insights into their customers' needs , preferences, and behaviors. By following the tips and best practices outlined in this article, you can conduct interviews that provide you with rich data that you can use to make informed decisions about your products, services, and marketing strategies.

Remember that effective communication, active listening, and proper analysis are critical components of successful qualitative interviews. By incorporating these practices into your customer research, you can gain a competitive edge and build stronger customer relationships.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 16 August 2024

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

Root out friction in every digital experience, super-charge conversion rates, and optimize digital self-service

Uncover insights from any interaction, deliver AI-powered agent coaching, and reduce cost to serve

Increase revenue and loyalty with real-time insights and recommendations delivered to teams on the ground

Know how your people feel and empower managers to improve employee engagement, productivity, and retention

Take action in the moments that matter most along the employee journey and drive bottom line growth

Whatever they’re are saying, wherever they’re saying it, know exactly what’s going on with your people

Get faster, richer insights with qual and quant tools that make powerful market research available to everyone

Run concept tests, pricing studies, prototyping + more with fast, powerful studies designed by UX research experts

Track your brand performance 24/7 and act quickly to respond to opportunities and challenges in your market

Explore the platform powering Experience Management

- Free Account

- Product Demos

- For Digital

- For Customer Care

- For Human Resources

- For Researchers

- Financial Services

- All Industries

Popular Use Cases

- Customer Experience

- Employee Experience

- Net Promoter Score

- Voice of Customer

- Customer Success Hub

- Product Documentation

- Training & Certification

- XM Institute

- Popular Resources

- Customer Stories

- Artificial Intelligence

Market Research

- Partnerships

- Marketplace

The annual gathering of the experience leaders at the world’s iconic brands building breakthrough business results, live in Salt Lake City.

- English/AU & NZ

- Español/Europa

- Español/América Latina

- Português Brasileiro

- REQUEST DEMO

- Experience Management

- Qualitative Research Interviews

Try Qualtrics for free

How to carry out great interviews in qualitative research.

11 min read An interview is one of the most versatile methods used in qualitative research. Here’s what you need to know about conducting great qualitative interviews.

What is a qualitative research interview?

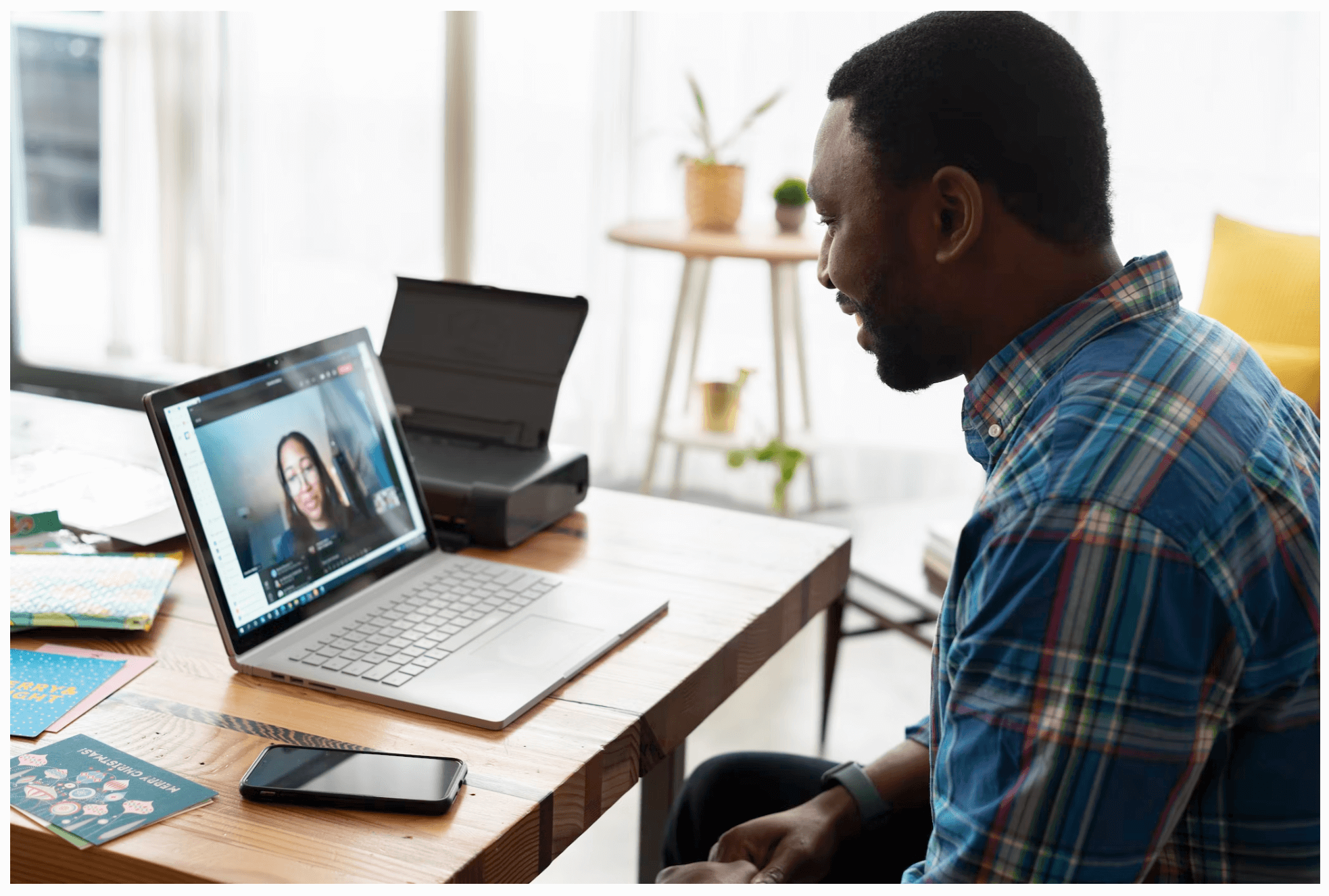

Qualitative research interviews are a mainstay among q ualitative research techniques, and have been in use for decades either as a primary data collection method or as an adjunct to a wider research process. A qualitative research interview is a one-to-one data collection session between a researcher and a participant. Interviews may be carried out face-to-face, over the phone or via video call using a service like Skype or Zoom.

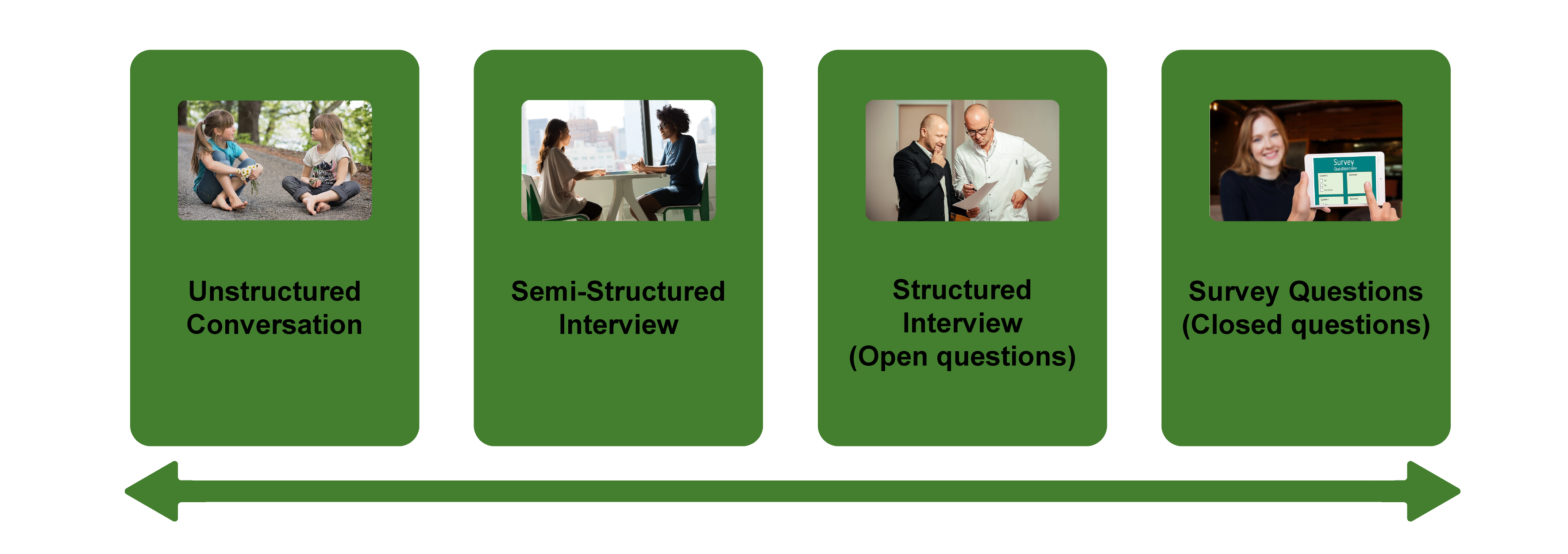

There are three main types of qualitative research interview – structured, unstructured or semi-structured.

- Structured interviews Structured interviews are based around a schedule of predetermined questions and talking points that the researcher has developed. At their most rigid, structured interviews may have a precise wording and question order, meaning that they can be replicated across many different interviewers and participants with relatively consistent results.

- Unstructured interviews Unstructured interviews have no predetermined format, although that doesn’t mean they’re ad hoc or unplanned. An unstructured interview may outwardly resemble a normal conversation, but the interviewer will in fact be working carefully to make sure the right topics are addressed during the interaction while putting the participant at ease with a natural manner.

- Semi-structured interviews Semi-structured interviews are the most common type of qualitative research interview, combining the informality and rapport of an unstructured interview with the consistency and replicability of a structured interview. The researcher will come prepared with questions and topics, but will not need to stick to precise wording. This blended approach can work well for in-depth interviews.

Free eBook: The qualitative research design handbook

What are the pros and cons of interviews in qualitative research?

As a qualitative research method interviewing is hard to beat, with applications in social research, market research, and even basic and clinical pharmacy. But like any aspect of the research process, it’s not without its limitations. Before choosing qualitative interviewing as your research method, it’s worth weighing up the pros and cons.

Pros of qualitative interviews:

- provide in-depth information and context

- can be used effectively when their are low numbers of participants

- provide an opportunity to discuss and explain questions

- useful for complex topics

- rich in data – in the case of in-person or video interviews , the researcher can observe body language and facial expression as well as the answers to questions

Cons of qualitative interviews:

- can be time-consuming to carry out

- costly when compared to some other research methods

- because of time and cost constraints, they often limit you to a small number of participants

- difficult to standardize your data across different researchers and participants unless the interviews are very tightly structured

- As the Open University of Hong Kong notes, qualitative interviews may take an emotional toll on interviewers

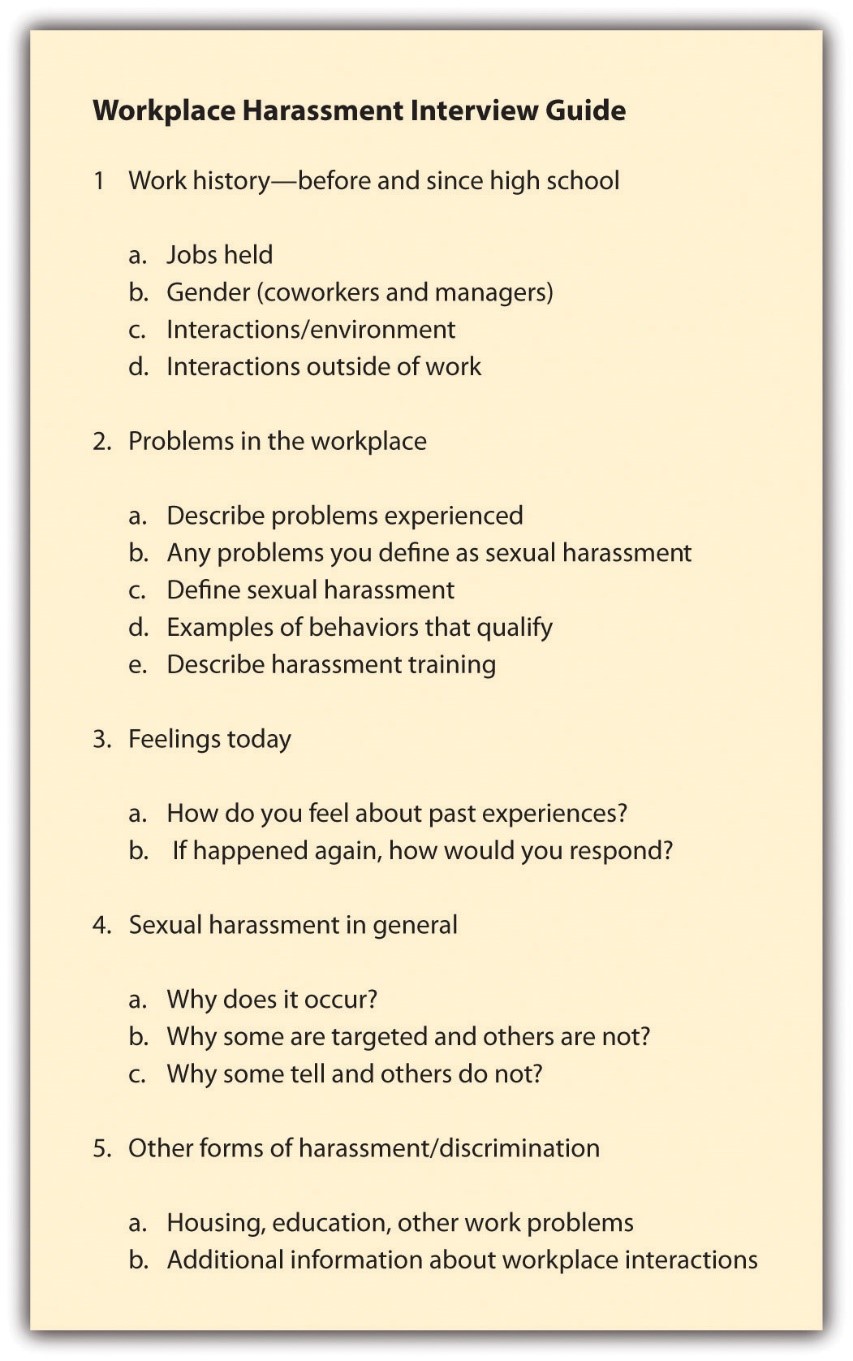

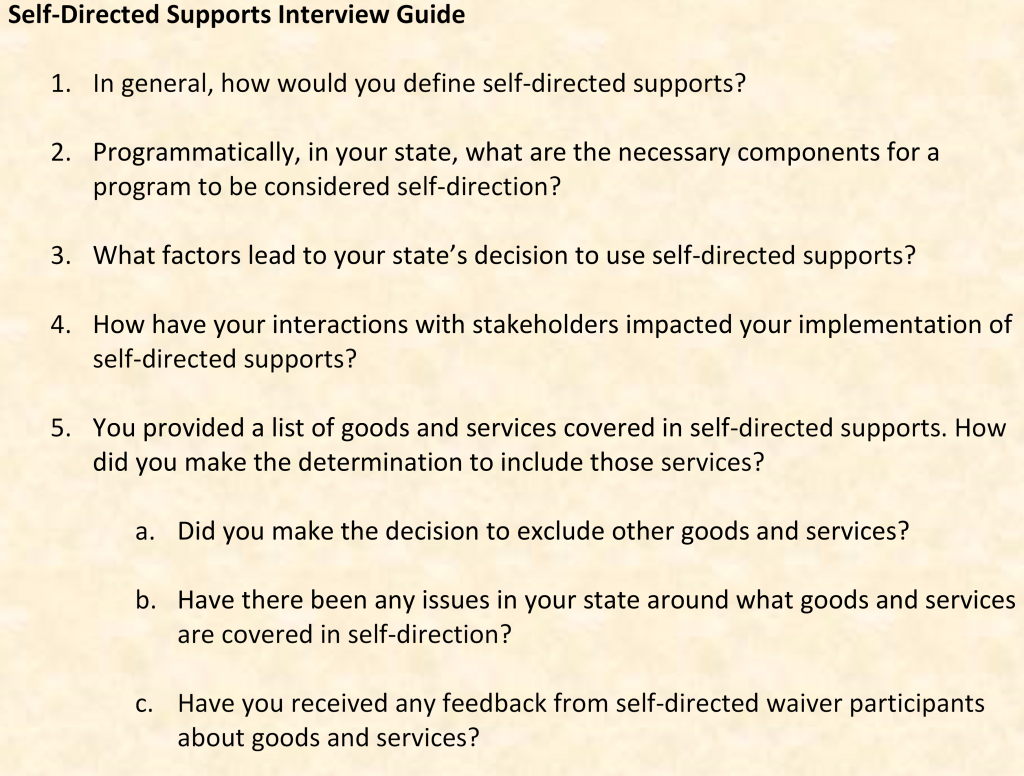

Qualitative interview guides

Semi-structured interviews are based on a qualitative interview guide, which acts as a road map for the researcher. While conducting interviews, the researcher can use the interview guide to help them stay focused on their research questions and make sure they cover all the topics they intend to.

An interview guide may include a list of questions written out in full, or it may be a set of bullet points grouped around particular topics. It can prompt the interviewer to dig deeper and ask probing questions during the interview if appropriate.

Consider writing out the project’s research question at the top of your interview guide, ahead of the interview questions. This may help you steer the interview in the right direction if it threatens to head off on a tangent.

Avoid bias in qualitative research interviews

According to Duke University , bias can create significant problems in your qualitative interview.

- Acquiescence bias is common to many qualitative methods, including focus groups. It occurs when the participant feels obliged to say what they think the researcher wants to hear. This can be especially problematic when there is a perceived power imbalance between participant and interviewer. To counteract this, Duke University’s experts recommend emphasizing the participant’s expertise in the subject being discussed, and the value of their contributions.

- Interviewer bias is when the interviewer’s own feelings about the topic come to light through hand gestures, facial expressions or turns of phrase. Duke’s recommendation is to stick to scripted phrases where this is an issue, and to make sure researchers become very familiar with the interview guide or script before conducting interviews, so that they can hone their delivery.

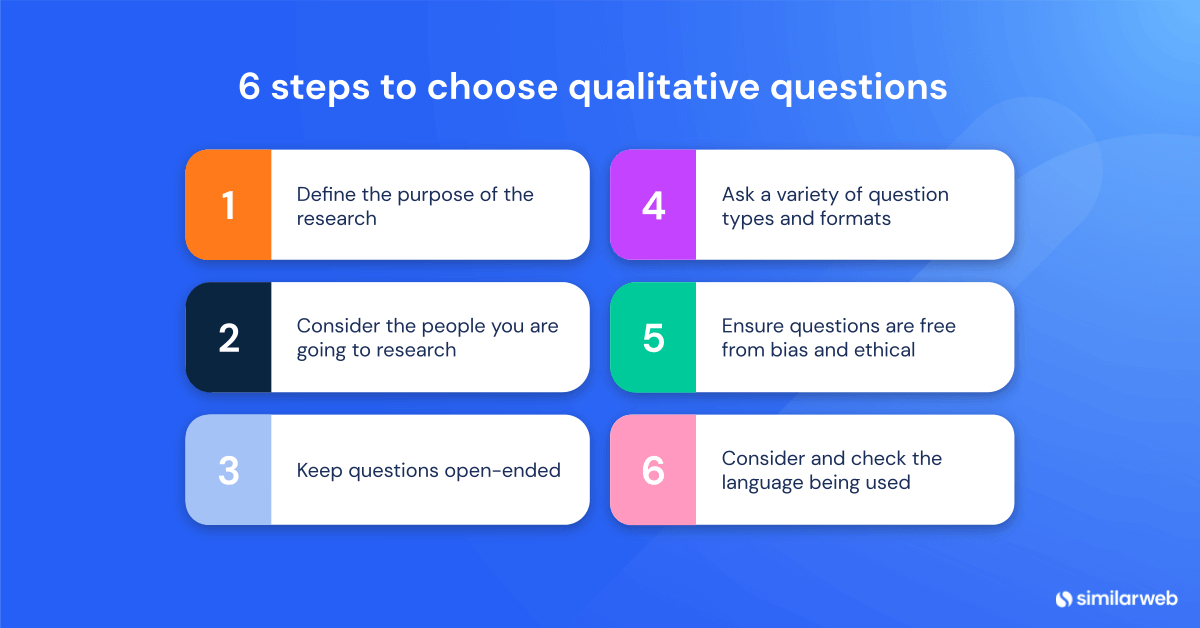

What kinds of questions should you ask in a qualitative interview?

The interview questions you ask need to be carefully considered both before and during the data collection process. As well as considering the topics you’ll cover, you will need to think carefully about the way you ask questions.

Open-ended interview questions – which cannot be answered with a ‘yes’ ‘no’ or ‘maybe’ – are recommended by many researchers as a way to pursue in depth information.

An example of an open-ended question is “What made you want to move to the East Coast?” This will prompt the participant to consider different factors and select at least one. Having thought about it carefully, they may give you more detailed information about their reasoning.

A closed-ended question , such as “Would you recommend your neighborhood to a friend?” can be answered without too much deliberation, and without giving much information about personal thoughts, opinions and feelings.

Follow-up questions can be used to delve deeper into the research topic and to get more detail from open-ended questions. Examples of follow-up questions include:

- What makes you say that?

- What do you mean by that?

- Can you tell me more about X?

- What did/does that mean to you?

As well as avoiding closed-ended questions, be wary of leading questions. As with other qualitative research techniques such as surveys or focus groups, these can introduce bias in your data. Leading questions presume a certain point of view shared by the interviewer and participant, and may even suggest a foregone conclusion.

An example of a leading question might be: “You moved to New York in 1990, didn’t you?” In answering the question, the participant is much more likely to agree than disagree. This may be down to acquiescence bias or a belief that the interviewer has checked the information and already knows the correct answer.

Other leading questions involve adjectival phrases or other wording that introduces negative or positive connotations about a particular topic. An example of this kind of leading question is: “Many employees dislike wearing masks to work. How do you feel about this?” It presumes a positive opinion and the participant may be swayed by it, or not want to contradict the interviewer.

Harvard University’s guidelines for qualitative interview research add that you shouldn’t be afraid to ask embarrassing questions – “if you don’t ask, they won’t tell.” Bear in mind though that too much probing around sensitive topics may cause the interview participant to withdraw. The Harvard guidelines recommend leaving sensitive questions til the later stages of the interview when a rapport has been established.

More tips for conducting qualitative interviews

Observing a participant’s body language can give you important data about their thoughts and feelings. It can also help you decide when to broach a topic, and whether to use a follow-up question or return to the subject later in the interview.

Be conscious that the participant may regard you as the expert, not themselves. In order to make sure they express their opinions openly, use active listening skills like verbal encouragement and paraphrasing and clarifying their meaning to show how much you value what they are saying.

Remember that part of the goal is to leave the interview participant feeling good about volunteering their time and their thought process to your research. Aim to make them feel empowered , respected and heard.

Unstructured interviews can demand a lot of a researcher, both cognitively and emotionally. Be sure to leave time in between in-depth interviews when scheduling your data collection to make sure you maintain the quality of your data, as well as your own well-being .

Recording and transcribing interviews

Historically, recording qualitative research interviews and then transcribing the conversation manually would have represented a significant part of the cost and time involved in research projects that collect qualitative data.

Fortunately, researchers now have access to digital recording tools, and even speech-to-text technology that can automatically transcribe interview data using AI and machine learning. This type of tool can also be used to capture qualitative data from qualitative research (focus groups,ect.) making this kind of social research or market research much less time consuming.

Data analysis

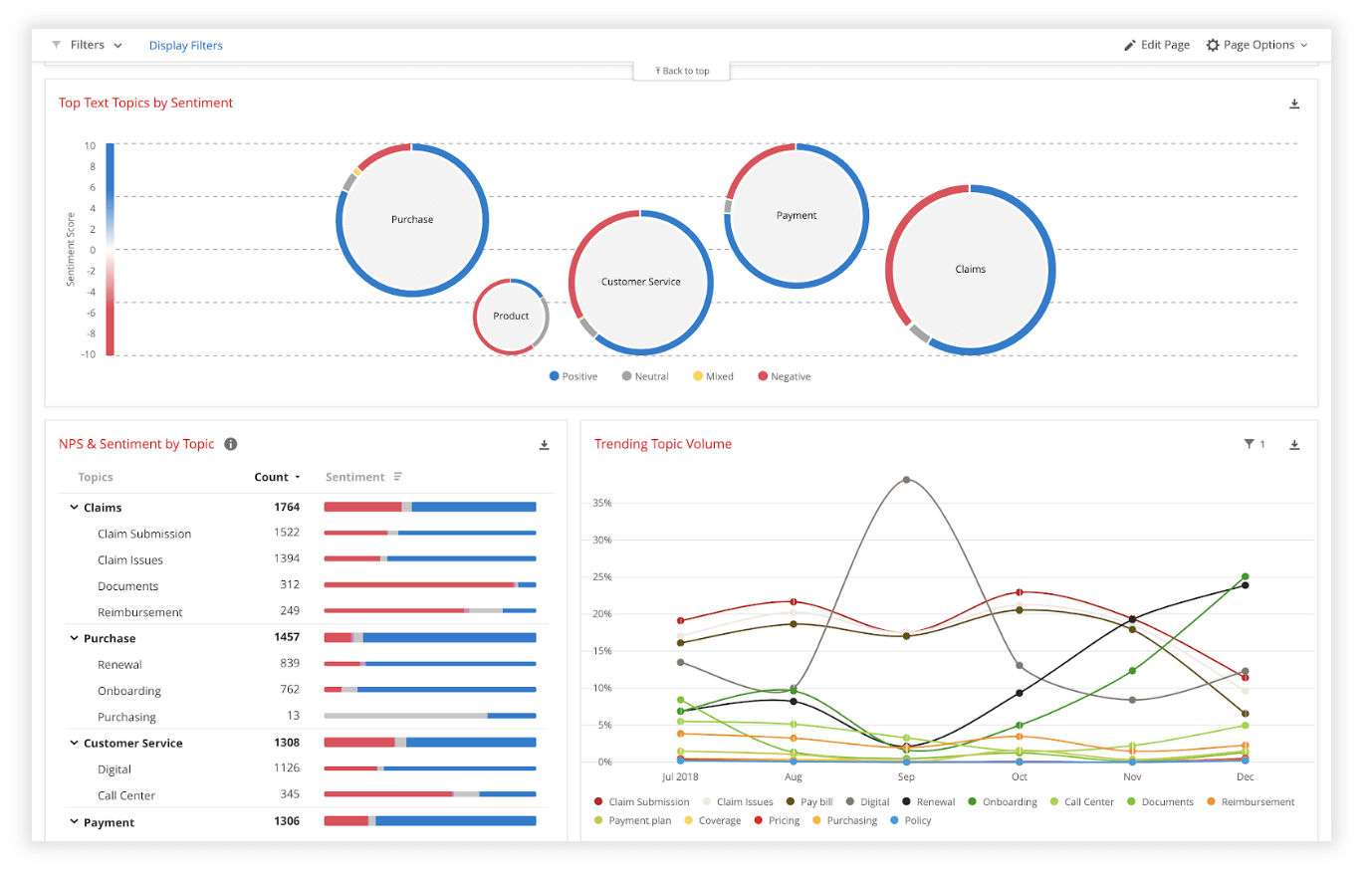

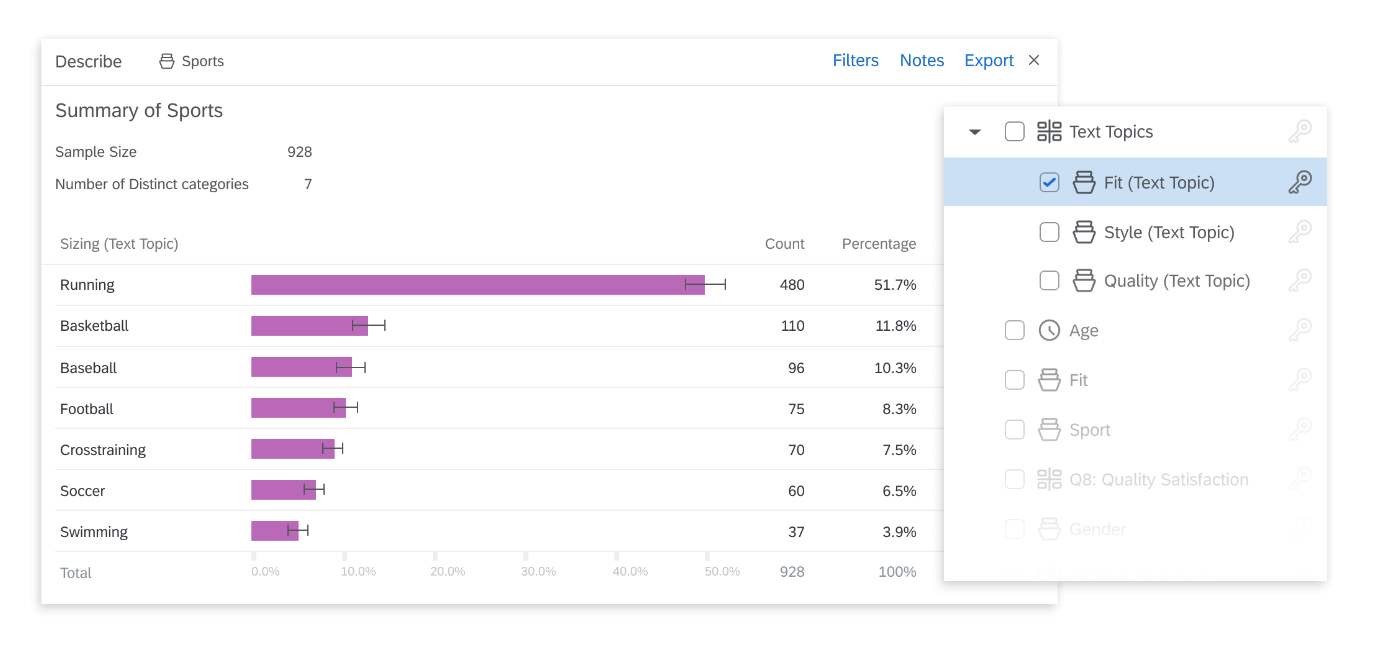

Qualitative interview data is unstructured, rich in content and difficult to analyze without the appropriate tools. Fortunately, machine learning and AI can once again make things faster and easier when you use qualitative methods like the research interview.

Text analysis tools and natural language processing software can ‘read’ your transcripts and voice data and identify patterns and trends across large volumes of text or speech. They can also perform khttps://www.qualtrics.com/experience-management/research/sentiment-analysis/

which assesses overall trends in opinion and provides an unbiased overall summary of how participants are feeling.

Another feature of text analysis tools is their ability to categorize information by topic, sorting it into groupings that help you organize your data according to the topic discussed.

All in all, interviews are a valuable technique for qualitative research in business, yielding rich and detailed unstructured data. Historically, they have only been limited by the human capacity to interpret and communicate results and conclusions, which demands considerable time and skill.

When you combine this data with AI tools that can interpret it quickly and automatically, it becomes easy to analyze and structure, dovetailing perfectly with your other business data. An additional benefit of natural language analysis tools is that they are free of subjective biases, and can replicate the same approach across as much data as you choose. By combining human research skills with machine analysis, qualitative research methods such as interviews are more valuable than ever to your business.

Related resources

Market intelligence 10 min read, marketing insights 11 min read, ethnographic research 11 min read, qualitative vs quantitative research 13 min read, qualitative research questions 11 min read, qualitative research design 12 min read, primary vs secondary research 14 min read, request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?