Selecting the Perfect Case Study Project for Your Part 3 Submission: Insight from Architect Knowhow

Introduction.

Are you an aspiring architect in the United Kingdom getting ready to submit your Part 3 portfolio? Choosing the correct case study project is a vital step in displaying your professional skills. In this episode of the Architect Knowhow Channel, we look at the most important criteria to consider when choosing a case study project. We cover everything from complexity and commitment to principles to collaboration with consultants and technical challenges. Join us as we provide valuable insights and guidance to assist you in making the best decision possible.

Understanding the Importance of Case Study Selection:

Selecting the appropriate case study project can significantly impact your Part 3 submission. We explain why this decision holds importance and how it can influence your chances of success. By highlighting the project's complexity, your position and responsibilities, and adherence to ARB and RIBA principles, we emphasize the key elements to consider.

Exploring Crucial Factors:

In this section, we delve deeper into the factors that should influence your case study selection. We discuss the importance of demonstrating your involvement in the design process and how to effectively collaborate with consultants to ensure compliance with technical specifications. Additionally, we shed light on technical challenges specific to architecture, such as structural systems, building envelope systems, and mechanical and electrical systems.

Integrating Sustainability, Accessibility, and Context:

A well-rounded case study project should encompass sustainability, accessibility, and context. We provide valuable tips on how to incorporate these elements into your chosen project, allowing you to effectively showcase your design skills. By emphasizing the significance of sustainability, we encourage architects to embrace environmentally friendly practices and innovations.

Project Management Techniques:

Efficient project management is crucial for success as an architect. We highlight essential project management techniques such as leadership, compliance with the law, and effective communication. By mastering these skills, you can enhance your case study project and demonstrate your ability to oversee complex architectural endeavors.

The Role of Collaboration and Expertise:

Architects rarely work in isolation. Coordination and collaboration with various experts are integral to successful project delivery. We emphasize the importance of working with consultants, resolving disputes, and incorporating building techniques and sustainable design ideas into your case study project. Furthermore, we discuss technical topics like MEP engineering, structural and building envelope systems, and the latest tools and software.

Selecting the right case study project for your Part 3 submission is an opportunity to showcase your professional competence as an architect. By following the insights and guidance provided in this episode of Architect Knowhow, you can confidently choose a project that aligns with your goals and effectively demonstrates your design skills. Do not overthink the selection process; instead, utilize our simple yet effective framework to put your best foot forward. Remember to subscribe to Architect Knowhow for more valuable insights and stay tuned for their upcoming book on Attributes and Constraints, a valuable reference for site evaluation in architectural practice.

Popular Posts

Innovative building materials for modern architecture: a guide for practicing architects and part 3 case study development, how to craft an effective introduction for your architectural case study.

Part 3 Handbook

| Author/Editor | Brookhouse, Stephen (Author) |

| Pub Date | 01/11/2020 |

| Binding | Paperback |

| Pages | 264 |

| Edition | 4th Ed |

| Dimensions (mm) | 210(h) * 170(w) |

How to Thrive at Architecture School: A Student Guide

Riba job book (10th edition), architect's legal pocket book, architect's legal handbook: the law for architects, good practice guide: fees, contact info, information, newsletter subscription, newsletter subscription.

'Your part

Recording and downloads available here .

part 3 interview questions

Preparing for your interview.

A common question I receive is what advice I would offer to someone sitting their Part 3 interview. As an examiner, I offer the following advice with a pinch a salt, as they should be carefully adopted as over committing to any of these could potentially cause more harm than good. So, please remember the following:

You can influence the direction of conversation - don't forget it takes two to have a conversation, how you choose to expand or steer from one subject matter to another can set you up in other areas you maybe want to expand on or feel more comfortable in. If you leave it just up to the examiners, it'll be a Q&A interrogation which really doesn't bring the best out of any of you!

Own up to your mistakes - rather than waiting for the examiners to bring up your areas of weakness or highlight questions maybe you struggled on, own up to them. When you walk in and you get the cliche "How did the exams go?" feel free to totally own up and say "Q3 confused me because.... [x,y,z] and with hindsight I feel like I should have raised more... [1,2,3]". The quicker you get these off the table, the more you can focus on discussing things you feel stronger with!

Finally, remember - the interview is there to be a safety net , not necessarily another exam, but an opportunity for the examiners to verify any areas of weakness that may have appeared in your exams or coursework. In this sense, its a second chance with assistance you know better! With this in mind, hopefully its relaxing to know that the examiners are there to be working with you, not against you - so take a deep breath, you'll get there!

Below are example questions that I have asked, my colleagues have asked or have noted on students' coursework to raise within their interviews:

- Have you had any exposure to the profitability of the various work stages on your project?

- Can you explain what is present in appointments to protect architects from claims of a disproportionate liability?

- From the moment you submitted your planning application, can you please explain to us what happened and what other outcomes could have occurred?

- Talk us through the tendering process on your project...

- How did the public consultation process take place on this project? Was there a consultant? Did you embrace any significant changes? Was there a positive turnout?

- What is the difference between a Community Infrastructure Levy and a Section 106?

- Why did you choose to come to complete your studies in the UK?

- What drew you to the university of your choice for your Part 1 studies?

- What other methods of fee calculation are available for you to choose from?

- What is the role of the Quantity Surveyor (QS) on your project?

- Can a QS operate effectively if they're being supplied with only 50-70% of the detail design for the project?

- An Extension of Time (EOT) was issued for 25 weeks in total - can you break down the relevant evens that made up this total?

- Were you operating as a Lead Designer on your project? What are the responsibilities of a Lead Designer?

- How is most work procured within your office?

- What is the role of the Contractor Administrator?

- Should a dispute arise during works taking place on site, what options are available to you?

- Why did your Directors continue to use the old RIBA Plan of Work?

- What are the advantages of having a well-compiled Design Responsibility Matrix (DRM)?

- Are there any risks associated with an architect producing a cost-plan?

- If you saw bad health and safety practice taking place on a building site that you weren't involved on, would you say anything?

- If a discrepancy exists between the drawings and the specifications, which do you think overrides the other?

- When was Practical Completion issued? What's the importance of this certificate?

- What's the importance of understanding a contractor's critical path when evaluating Extensions of Time (EOT)?

- What is the difference between a relevant event, and a relevant matter?

- What are Liquidated Damages (LD) and how are they calculated?

- If during your tender a contractor wanted to propose significant changes for the benefit of the project, how can you maintain parity between all other tendering parties?

- Are you happy with the technical levels of competency you currently have and the creative satisfaction you've been searching for?

- Do you ever find that sustainability and heritage are opposing forces when working on a project?

- How do pay-less notices work in reference to Interim Certificates?

- Why did you choose to have an external Principal Designer on this project? What advantages did it offer you? Why didn't you choose a CDM coordinator?

- What was the purpose of an Information Release Schedule (IRS) on your project?

- Can you explain how Party Wall procedures diverged from a typical procedure as you mentioned in your case study?

- What is a Contractor's Design Portion and when might it be used?

- What's next in your career?

- Do you have access to the appointments and fee proposals within your office?

- What are important qualities to assume when operating as a 'Contractor Administrator'?

- In order to continue to trajectory of your career development, what CPDs (Continuing Professional Development) have you lined up over the next 12-months?

- How do you manage changes to a brief with your client? Is this recorded anywhere?

- What is the purpose of the 'Practical Completion Certificate'?

- How do you determine how much to invoice each month to the client?

- How does 'Intellectual Property' protect architects within appointment documents?

- Who are 'Historic England' and what are their role?

- What are 'Easements'? Can you give us an example?

- If you were setting up your own practice, what legal structure would you pick and why?

- How did your practice come to procure your case study project?

- Does your practice implement a 'Quality Assurance' System (QA)? What is its purpose?

- How do Directors within your practice approach resourcing for projects?

- Why did you opt to 'Selectively Tender' this project, were there any other options available to you?

- If quality had been the priority, would you have procured this project differently?

- If the client wanted to minimise their risk, what procurement route might you have been able to advise them on?

- What is the purpose of a 'back-to-back' clause?

- What is a 'Collateral Warranty' and what might you do should you find out your project has one?

- How were you recording progress on site?

- In the event that the project was not completed at the 'Date of Completion' written within the contract, what steps must the Contract Administrator take?

- Why might 'Adjudication' be preferred over 'Litigation'?

- What is the purpose of a 'Party Wall Agreement'?

- Why is parity important when handling tenders?

- If the Architect was not operating as the 'Contract Administrator' on the project, who might be a suitable candidate to fulfil this role?

- Why are timesheets important when recording time within your practice?

- Why did you choose to submit a 'Pre-Planning Application' for your project?

- What are 'Reserved Matters' when discussing an 'Outline Planning' Application?

- What are examples of 'Relevant Events'? What's the difference between 'Relevant Events' and 'Relevant Matters'?

- Did you assume the role of 'Principal Designer' on your project? And if not, why?

- What responsibilities does the 'Principal Designer' have during the Pre-Construction Phase?

- What is a 'Health and Safety File' and who would be in possession of it following the completion of a project?

- What is a 'Retention Fee'?

- How does 'Duty of Care' compare to 'Fit for Purpose'?

- What is the purpose of 'Professional Indemnity' insurance?

- If an accident was to occur on site, what might you do?

- What is an Architect's Instruction and when might you use one?

- What role did an 'Information Release Schedule' play in your programming of the next stage?

- Are you familiar with the different forms of action that the 'Professional Conduct Committee' (PCC) can take against architects?

- Whose interests are the ARB trying to protect?

- Why did you choose to appoint an 'Approved Inspector' over a 'Local Council Inspector'?

- What risks could you face if you didn't follow the planning permission you had obtained?

- What is a 'Community Infrastructure Levy' and how do they differ from Section 106 agreements?

- If you decided to go to appeal the planning decision, what is the process ahead of you?

- What is a 'covenant' when referring to Land Law?

- What advantages did 'Building Information Modelling' (BIM) offer your project?

- Would the presence of a 'Bill of Quantities' (BOQ) assisted your tendering process at all?

- Talk us through the process surrounding 'Interim Certificates'.

- In what ways can the Architect monitor quality on-site?

- What must we be weary of when clients and contractors propose additional clauses to appointments or construction contracts?

- Do you know what your cost is to practice on an hourly basis and how it is calculated?

- What is a 'Novation'?

- What benefits are available in becoming an 'RIBA Chartered Practice'?

- What methods of obtaining input on construction cost are available to you?

- What is the 'Final Account'?

- Who does 'Professional Indemnity Insurance' protect?

- What does it mean for a contract to be signed 'under deed', would you approach anything differently?

- Under Construction Design Management (CDM) Regulations (2015), who is responsible for putting together a 'Construction Phase Plan'?

- What extra considerations did you need to with your involvement on a 'Listed Building'?

- Does your practice ever sub-contract services? What considerations must you make in doing so?

- Was a 'Stakeholder Management Plan' utilised at all?

- How does your practice go about themes such as 'Staff Development'?

- Does your practice have a 'Marketing Plan'? Have you been exposed to it or strategies and tactics contained within it?

- How has your practice evolved over COVID? Do you currently have a flexible working arrangement?

- Why might your pursue 'International Organisation for Standardisation' (ISO) accreditation?

- What is your practice currently doing on the theme of sustainability? Do you think as an Architect you have a professional obligation to design sustainably?

Continued (questions from 2022)

- Why did you come to the this University for your Part III?

- You’ve been at [Practice Name] for your entire career to date? Was that calculated? Do you think it’s benefited your or limited your learning on this Part III course in any way?

- You have interesting soft skills prior to joining architecture, talk to me about how it’s prepared you for the profession?

- Can you tell me more about your opinion on working culture and the responsibility of studio mentors passing knowledge onto others?

- Y ou mention how History and Theory helped you understand how the role developed from master mason to architect what it means in the modern construction industry which led to a frustration into what the role and liability of an architect has become. Can you expand on this evolution and frustration?

- Do you think your expectations of your experiences in practice were valid? Which would you say is at the fault of academia not preparing you enough, and which is where your employer fell short?

- W hat lessons did you walk away with from your hands-on experience on site? Did you witness and bad habits that you have made you more cautious moving forward?

- You mentioned that you took on the role of the Office Manager during your employment. What did this include? Were there any formal changes to your employment contract? How did you manage your time?

- Does your employer have a Quality Management System in-place? ISO? RIBA Accreditation?

- How were the fees for the feasibility studies calculated? You’re critical of the speed of producing these one/two day studies, what would you propose differently?

- At present, the client is the QS, CA and Main Contractor. But if they weren’t the main contractor, could their operations as QS/CA be a problem? What problems do you foresee?

- C an you explain all the overlaps in work stages in your timeline? Any risks, problems, do you think this is best practice? When is it recommended for planning applications to be submitted? Why was it submitted at Stage 2?

- How important are Post Occupancy Evaluations to your practice and design methodology?

- What steps would you take if you were approached to sign bespoke appointment?

- Are there any considerations that should be made if an appointment is a deed?

- Y ou mention two types of fee calculation, a form of lump sum fee and an abridged unit-based fee, can you expand on the pros and cons of both?

- C an you give a high-level summary of a typical planning process? What are DRPs and Pre-Planning Applications and what do they offer?

- What planning conditions did your project have? What do you think is the purpose of planning conditions? Can you explain this scenario surrounding lifts, was this a planning condition? Why was it not coordinated, who made the recommendation to proceed without?

- Can you explain the key parties and key documents and how and when they are exchanged? Phased Construction Plan, (Construction Phase Plan), whose responsibility? H&S file? Pre-Construction Information?

- With regards to Party Wall Agreements, what is the legal definition of ‘on’ or ‘near’?

- Are verbal agreements enough? Would you ever conduct work under a verbal agreement with a client? Or changes to a construction contract verbally?

- What are the risks of having built something that doesn’t have a party wall award or listed building consent? What repercussions would you expect?

- You mentioned that as a contract it removes a lot of risk from your employer/practice? How so? Compared to what type of contract type?

- Why did the subcontractor alter the pre-cast system? How can you avoid this panelised system alteration incident in the future? Was early expertise sought?

- What role does technology play in Architecture? You’re obviously a big advocate, but I’d like your insights as to the strengths and weaknesses it offers to a project?

- How do you reconcile the differences between your initial ambition for craft, while working on such big projects that can span decades?

- Why did your employer choose to operate as an LLP? What other options did they have also?

- What does 'Joint and Several Liability' mean?

- Why do you think that 'Adjudication' was chosen?

- Why were other procurement routes deemed inappropriate?

- Your project has lots in terms of documents and guidance, how was this managed and disseminated within the team?

- Schedule 17 and High Speed Rail Act 2017, how do these differ from traditional planning routes? Please describe both.

- What is the significance of 'Practical Completion' under NEC but also typical JCT/traditional contracts?

- We all want to revise the Part-systems, how do you reflect on your foundation course? Was it pivotal? Did it provide something that the part system didn’t provide you?

- Most incoming work is through referrals, how else does the practice approach marketing and new work? If none, what options are available to them?

- £300/day assistant? Do you know how this figure is calculated? Can you determine profitability in the absence of timesheets?

- How do you feel about the appointment of the consultant team during Stage 03 and 04?

- When did you notify the client about their responsibilities under CDM? Did you charge a fee for undertaking the PD role? Does the submission of the DRA to the contractor days prior to commencement leave them enough time? Doesn’t the Principle Contractor need to produce documentation prior to starting also?

- If you didn’t want to use an Approved Inspector, who might you approach?

- You described what relevant events are, can you give me an example of some? Where might you look for an extensive list?

- Can you run through the tendering process? What was submitted? Looking back, would you share any other information? Were there any planning conditions imposed on the scheme? Moving forward, if a client insists they have a preferred contractor, would you only tender to one party again?

- Are there any alternatives available to Partial Possession Certificates under a different contract?

- Can you elaborate on the process surrounding practical completion, what would you do in the run-up, what happens after up until the Final Certificate?

- When is an amendment considered to be a non-material and when is it considered material?

- What does a BIM Execution Plan entail?

- How successful was having an in-house design team for the contractor in the end? Would you recommend it to others?

- how can you better prepare for engaging all these various stakeholders? Do they all have valid authority to provide you feedback that you have to take on?

- How important is being able to draw and sketch to you becoming an architect would you say? Is it still a prerequisite in education?

- ‘The contractor was unable to perform their duties competently which in turn accumulated in additional hours that [Practice Name] has had to resource towards’ - how was the contractor incompetent? How do you assess competency?

- How do you feel about having dedicated workforces for planning and technical delivery within the practice?

Copyright © 2024 Spare Part - RIBA Part III Learning Resource - All Rights Reserved.

Powered by GoDaddy

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Architecture

- Inspiration

RIBA ARB Part 3 Exams | Recommended Reading List

Two years ago, i wrote a blog post ” Becoming an Architect – My RIBA Part 3 Exam Experience” , in which I received many comments and emails regarding questions on Part 3 case study, PEDRs, interview questions and many more. One of the most popular questions I was being asked all the time was the Part 3 reading list. So I put together a full list here and divided them into the following 12 categories:

a. Architect Contract; b. Building Contract; c. Building Regulations; d. Code of Conducts; e. Design and Legislation; f. Dispute Resolution; g. Health and Safety; h. Law and Act; i. Practice Management; j. Project Management; k. Planning; l. Others

a. Architect Contract

B. Building Contract

c. Building Regulations

d. Code of Conducts

e. Design and Legislation

f. Dispute Resolution

g. Health and Safety

h. Law and Act

i. Practice Management

j. Project Management

| | |||

| tarting a Practice |

k. Planning

That’s a very long suggested book list for sure. I would recommend you sit down in the library for a weekend to flip through the books above so you have a basic idea where to look for information when needed. Once you begin writing Professional Case Study, then you can easily revert back to the specific books for detail information to fill in each chapter. This applies the same to short questions/Coursework and past paper too.

I hope you find this blog post useful! If you are taking part 3 exams, you might find my other blog post “ Becoming an Architect – My RIBA Part 3 Exam Experience” , useful. Feel free to drop comments below.

You may also like

Kick-off site meeting.

M+ Museum Visit

Important Notice: Sensing Cities Round Table Discussions will be cancelled

Thanks for sharing the booklist.

Thank you for the list.

You’re welcome!

Leave a Reply Cancel Reply

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Part 3 Handbook, 4th Edition by Stephen Brookhouse

Get full access to Part 3 Handbook, 4th Edition and 60K+ other titles, with a free 10-day trial of O'Reilly.

There are also live events, courses curated by job role, and more.

4The Case Study

This chapter covers the role of the case study in the RIBA Part 3 examination.

It includes:

- different Part 3 providers’ approaches to the case study

- the role of the case study in the Part 3 examination

- some key points

- getting started

- length – some words about words

- case study structure

- looking at each section in detail

- applying your analytical and critical skills to key issues

- a wider perspective

- good practice: feedback from examiners, and

- some case study myths.

In essence, the case study is a vehicle to show your knowledge and understanding of the Professional Criteria using your project and workplace experiences ...

Get Part 3 Handbook, 4th Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.

Don’t leave empty-handed

Get Mark Richards’s Software Architecture Patterns ebook to better understand how to design components—and how they should interact.

It’s yours, free.

Check it out now on O’Reilly

Dive in for free with a 10-day trial of the O’Reilly learning platform—then explore all the other resources our members count on to build skills and solve problems every day.

- Utility Menu

harvardchan_logo.png

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Case-Based Teaching & Learning Initiative

Teaching cases & active learning resources for public health education, teaching & learning with the case method.

2023. Case Compendium, University of California Berkeley Haas School of Business Center for Equity, Gender & Leadership . Visit website This resource, compiled by the Berkeley Haas Center for Equity, Gender & Leadership, is "a case compendium that includes: (a) case studies with diverse protagonists, and (b) case studies that build “equity fluency” by focusing on DEI-related issues and opportunities. The goal of the compendium is to support professors at Haas, and business schools globally, to identify cases they can use in their own classrooms, and ultimately contribute to advancing DEI in education and business."

Kane, N.M. , 2014. Benefits of Case-Based Teaching . Watch video Watch a demonstration of Prof. Nancy Kane teaching public health with the case method. (Part 3 of 3, 3 minutes)

Kane, N.M. , 2014. Case teaching demonstration: Should a health plan cover medical tourism? . Watch video Watch a demonstration of Prof. Nancy Kane teaching public health with the case method. (Part 2 of 3, 17 minutes)

Kane, N.M. , 2014. Case-based teaching at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health . Watch video Watch a demonstration of Prof. Nancy Kane teaching public health with the case method. (Part 1 of 3, 10 minutes)

2019. The Case Centre . Visit website A non-profit clearing house for materials on the case method, the Case Centre holds a large and diverse collection of cases, articles, book chapters and teaching materials, including the collections of leading business schools across the globe.

Austin, S.B. & Sonneville, K.R. , 2013. Closing the "know-do" gap: training public health professionals in eating disorders prevention via case-method teaching. International Journal of Eating Disorders , 46 (5) , pp. 533-537. Read online Abstract Expansion of our societies' capacity to prevent eating disorders will require strategic integration of the topic into the curricula of professional training programs. An ideal way to integrate new content into educational programs is through the case-method approach, a teaching method that is more effective than traditional teaching techniques. The Strategic Training Initiative for the Prevention of Eating Disorders has begun developing cases designed to be used in classroom settings to engage students in topical, high-impact issues in public health approaches to eating disorders prevention and screening. Dissemination of these cases will provide an opportunity for students in public health training programs to learn material in a meaningful context by actively applying skills as they are learning them, helping to bridge the "know-do" gap. The new curriculum is an important step toward realizing the goal that public health practitioners be fully equipped to address the challenge of eating disorders prevention. "Expansion of our societies' capacity to prevent eating disorders will require strategic integration of the topic into the curricula of professional training programs. An ideal way to integrate new content into educational programs is through the case-method approach, a teaching method that is more effective than traditional teaching techniques." Access full article with HarvardKey .

Ellet, W. , 2018. The Case Study Handbook, Revised Edition: A Student's Guide , Harvard Business School Publishing. Publisher's Version "If you're like many people, you may find interpreting and writing about cases mystifying and time-consuming. In The Case Study Handbook, Revised Edition , William Ellet presents a potent new approach for efficiently analyzing, discussing, and writing about cases."

Andersen, E. & Schiano, B. , 2014. Teaching with Cases: A Practical Guide , Harvard Business School Publishing. Publisher's Version "The class discussion inherent in case teaching is well known for stimulating the development of students' critical thinking skills, yet instructors often need guidance on managing that class discussion to maximize learning. Teaching with Cases focuses on practical advice for instructors that can be easily implemented. It covers how to plan a course, how to teach it, and how to evaluate it."

Honan, J. & Sternman Rule, C. , 2002. Case Method Instruction Versus Lecture-Based Instruction R. Reis, ed. Tomorrow's Professor . Read online "Faculty and discussion leaders who incorporate the case study method into their teaching offer various reasons for their enthusiasm for this type of pedagogy over more traditional, such as lecture-based, instructional methods and routes to learning." Exerpt from the book Using Cases in Higher Education: A Guide for Faculty and Administrators , by James P. Honan and Cheryl Sternman Rule.

Austin, J. , 1993. Teaching Notes: Communicating the Teacher's Wisdom , Harvard Business School Publishing. Publisher's Version "Provides guidance for the preparation of teaching notes. Sets forth the rationale for teaching notes, what they should contain and why, and how they can be prepared. Based on the experiences of Harvard Business School faculty."

Abell, D. , 1997. What makes a good case? . ECCHO–The Newsletter of the European Case Clearing House , 17 (1) , pp. 4-7. Read online "Case writing is both art and science. There are few, if any, specific prescriptions or recipes, but there are key ingredients that appear to distinguish excellent cases from the run-of-the-mill. This technical note lists ten ingredients to look for if you are teaching somebody else''s case - and to look out for if you are writing it yourself."

Herreid, C.F. , 2001. Don't! What not to do when teaching cases. Journal of College Science Teaching , 30 (5) , pp. 292. Read online "Be warned, I am about to unleash a baker’s dozen of 'don’ts' for aspiring case teachers willing to try running a classroom discussion armed with only a couple of pages of a story and a lot of chutzpah."

Garvin, D.A. , 2003. Making the case: Professional education for the world of practice . Harvard Magazine , 106 (1) , pp. 56-65. Read online A history and overview of the case-method in professional schools, which all “face the same difficult challenge: how to prepare students for the world of practice. Time in the classroom must somehow translate directly into real-world activity: how to diagnose, decide, and act."

- Writing a case (8)

- Writing a teaching note (4)

- Active learning (12)

- Active listening (1)

- Asking effective questions (5)

- Assessing learning (1)

- Engaging students (5)

- Leading discussion (10)

- Managing the classroom (4)

- Planning a course (1)

- Problem-based learning (1)

- Teaching & learning with the case method (14)

- Teaching inclusively (3)

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Creating Brand Value

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading Change and Organizational Renewal

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

5 Benefits of Learning Through the Case Study Method

- 28 Nov 2023

While several factors make HBS Online unique —including a global Community and real-world outcomes —active learning through the case study method rises to the top.

In a 2023 City Square Associates survey, 74 percent of HBS Online learners who also took a course from another provider said HBS Online’s case method and real-world examples were better by comparison.

Here’s a primer on the case method, five benefits you could gain, and how to experience it for yourself.

Access your free e-book today.

What Is the Harvard Business School Case Study Method?

The case study method , or case method , is a learning technique in which you’re presented with a real-world business challenge and asked how you’d solve it. After working through it yourself and with peers, you’re told how the scenario played out.

HBS pioneered the case method in 1922. Shortly before, in 1921, the first case was written.

“How do you go into an ambiguous situation and get to the bottom of it?” says HBS Professor Jan Rivkin, former senior associate dean and chair of HBS's master of business administration (MBA) program, in a video about the case method . “That skill—the skill of figuring out a course of inquiry to choose a course of action—that skill is as relevant today as it was in 1921.”

Originally developed for the in-person MBA classroom, HBS Online adapted the case method into an engaging, interactive online learning experience in 2014.

In HBS Online courses , you learn about each case from the business professional who experienced it. After reviewing their videos, you’re prompted to take their perspective and explain how you’d handle their situation.

You then get to read peers’ responses, “star” them, and comment to further the discussion. Afterward, you learn how the professional handled it and their key takeaways.

Learn more about HBS Online's approach to the case method in the video below, and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more.

HBS Online’s adaptation of the case method incorporates the famed HBS “cold call,” in which you’re called on at random to make a decision without time to prepare.

“Learning came to life!” said Sheneka Balogun , chief administration officer and chief of staff at LeMoyne-Owen College, of her experience taking the Credential of Readiness (CORe) program . “The videos from the professors, the interactive cold calls where you were randomly selected to participate, and the case studies that enhanced and often captured the essence of objectives and learning goals were all embedded in each module. This made learning fun, engaging, and student-friendly.”

If you’re considering taking a course that leverages the case study method, here are five benefits you could experience.

5 Benefits of Learning Through Case Studies

1. take new perspectives.

The case method prompts you to consider a scenario from another person’s perspective. To work through the situation and come up with a solution, you must consider their circumstances, limitations, risk tolerance, stakeholders, resources, and potential consequences to assess how to respond.

Taking on new perspectives not only can help you navigate your own challenges but also others’. Putting yourself in someone else’s situation to understand their motivations and needs can go a long way when collaborating with stakeholders.

2. Hone Your Decision-Making Skills

Another skill you can build is the ability to make decisions effectively . The case study method forces you to use limited information to decide how to handle a problem—just like in the real world.

Throughout your career, you’ll need to make difficult decisions with incomplete or imperfect information—and sometimes, you won’t feel qualified to do so. Learning through the case method allows you to practice this skill in a low-stakes environment. When facing a real challenge, you’ll be better prepared to think quickly, collaborate with others, and present and defend your solution.

3. Become More Open-Minded

As you collaborate with peers on responses, it becomes clear that not everyone solves problems the same way. Exposing yourself to various approaches and perspectives can help you become a more open-minded professional.

When you’re part of a diverse group of learners from around the world, your experiences, cultures, and backgrounds contribute to a range of opinions on each case.

On the HBS Online course platform, you’re prompted to view and comment on others’ responses, and discussion is encouraged. This practice of considering others’ perspectives can make you more receptive in your career.

“You’d be surprised at how much you can learn from your peers,” said Ratnaditya Jonnalagadda , a software engineer who took CORe.

In addition to interacting with peers in the course platform, Jonnalagadda was part of the HBS Online Community , where he networked with other professionals and continued discussions sparked by course content.

“You get to understand your peers better, and students share examples of businesses implementing a concept from a module you just learned,” Jonnalagadda said. “It’s a very good way to cement the concepts in one's mind.”

4. Enhance Your Curiosity

One byproduct of taking on different perspectives is that it enables you to picture yourself in various roles, industries, and business functions.

“Each case offers an opportunity for students to see what resonates with them, what excites them, what bores them, which role they could imagine inhabiting in their careers,” says former HBS Dean Nitin Nohria in the Harvard Business Review . “Cases stimulate curiosity about the range of opportunities in the world and the many ways that students can make a difference as leaders.”

Through the case method, you can “try on” roles you may not have considered and feel more prepared to change or advance your career .

5. Build Your Self-Confidence

Finally, learning through the case study method can build your confidence. Each time you assume a business leader’s perspective, aim to solve a new challenge, and express and defend your opinions and decisions to peers, you prepare to do the same in your career.

According to a 2022 City Square Associates survey , 84 percent of HBS Online learners report feeling more confident making business decisions after taking a course.

“Self-confidence is difficult to teach or coach, but the case study method seems to instill it in people,” Nohria says in the Harvard Business Review . “There may well be other ways of learning these meta-skills, such as the repeated experience gained through practice or guidance from a gifted coach. However, under the direction of a masterful teacher, the case method can engage students and help them develop powerful meta-skills like no other form of teaching.”

How to Experience the Case Study Method

If the case method seems like a good fit for your learning style, experience it for yourself by taking an HBS Online course. Offerings span eight subject areas, including:

- Business essentials

- Leadership and management

- Entrepreneurship and innovation

- Digital transformation

- Finance and accounting

- Business in society

No matter which course or credential program you choose, you’ll examine case studies from real business professionals, work through their challenges alongside peers, and gain valuable insights to apply to your career.

Are you interested in discovering how HBS Online can help advance your career? Explore our course catalog and download our free guide —complete with interactive workbook sections—to determine if online learning is right for you and which course to take.

About the Author

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

The PMC website is updating on October 15, 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Eur J Gen Pract

- v.23(1); 2017

Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 2: Context, research questions and designs

Irene korstjens.

a Faculty of Health Care, Research Centre for Midwifery Science, Zuyd University of Applied Sciences, Maastricht, The Netherlands;

Albine Moser

b Faculty of Health Care, Research Centre Autonomy and Participation of Chronically Ill People, Zuyd University of Applied Sciences, Heerlen, The Netherlands;

c Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Department of Family Medicine, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands

In the course of our supervisory work over the years, we have noticed that qualitative research tends to evoke a lot of questions and worries, so-called frequently asked questions (FAQs). This series of four articles intends to provide novice researchers with practical guidance for conducting high-quality qualitative research in primary care. By ‘novice’ we mean Master’s students and junior researchers, as well as experienced quantitative researchers who are engaging in qualitative research for the first time. This series addresses their questions and provides researchers, readers, reviewers and editors with references to criteria and tools for judging the quality of qualitative research papers. This second article addresses FAQs about context, research questions and designs. Qualitative research takes into account the natural contexts in which individuals or groups function to provide an in-depth understanding of real-world problems. The research questions are generally broad and open to unexpected findings. The choice of a qualitative design primarily depends on the nature of the research problem, the research question(s) and the scientific knowledge one seeks. Ethnography, phenomenology and grounded theory are considered to represent the ‘big three’ qualitative approaches. Theory guides the researcher through the research process by providing a ‘lens’ to look at the phenomenon under study. Since qualitative researchers and the participants of their studies interact in a social process, researchers influence the research process. The first article described the key features of qualitative research, the third article will focus on sampling, data collection and analysis, while the last article focuses on trustworthiness and publishing.

Key points on context, research questions and designs

- Research questions are generally, broad and open to unexpected findings, and depending on the research process might change to some extent.

- The SPIDER tool is more suited than PICO for searching for qualitative studies in the literature, and can support the process of formulating research questions for original studies.

- The choice of a qualitative design primarily depends on the nature of the research problem, the research question, and the scientific knowledge one seeks.

- Theory guides the researcher through the research process by providing a ‘lens’ to look at the phenomenon under study.

- Since qualitative researchers and the participants interact in a social process, the researcher influences the research process.

Introduction

In an introductory paper [ 1 ], we have described the key features of qualitative research. The current article addresses frequently asked questions about context, research questions and design of qualitative research.

Why is context important?

Qualitative research takes into account the natural contexts in which individuals or groups function, as its aim is to provide an in-depth understanding of real-world problems [ 2 ]. In contrast to quantitative research, generalizability is not a guiding principle. According to most qualitative researchers, the ‘reality’ we perceive is constructed by our social, cultural, historical and individual contexts. Therefore, you look for variety in people to describe, explore or explain phenomena in real-world contexts. Influence from the researcher on the context is inevitable. However, by striving to minimalize your interfering with people’s natural settings, you can get a ‘behind the scenes’ picture of how people feel or what other forces are at work, which may not be discovered in a quantitative investigation. Understanding what practitioners and patients think, feel or do in their natural context, can make clinical practice and evidence-based interventions more effective, efficient, equitable and humane. For example, despite their awareness of widespread family violence, general practitioners (GPs) seem to be hesitant to ask about intimate partner violence. By applying a qualitative research approach, you might explore how and why practitioners act this way. You need to understand their context to be able to interact effectively with them, to analyse the data, and report your findings. You might consider the characteristics of practitioners and patients, such as their age, marital status, education, health condition, physical environment or social circumstances, and how and where you conduct your observations, interviews and group discussions. By giving your readers a ‘thick description’ of the participants’ contexts you render their behaviour, experiences, perceptions and feelings meaningful. Moreover, you enable your readers to consider whether and how the findings of your study can be transferred to their contexts.

Research questions

Why should the research question be broad and open.

To enable a thorough in-depth description, exploration or explanation of the phenomenon under study, in general, research questions need to be broad and open to unexpected findings. Within more in-depth research, for example, during building theory in a grounded theory design, the research question might be more focused. Where quantitative research asks: ‘how many, how much, and how often?’ qualitative research would ask: ‘what?’ and even more ‘how, and why?’ Depending on the research process, you might feel a need for fine-tuning or additional questions. This is common in qualitative research as it works with ‘emerging design,’ which means that it is not possible to plan the research in detail at the start, as the researchers have to be responsive to what they find as the research proceeds. This flexibility within the design is seen as a strength in qualitative research but only within an overall coherent methodology.

What kind of literature would I search for when preparing a qualitative study?

You would search for literature that can provide you with insights into the current state of knowledge and the knowledge gap that your study might address ( Box 1 ). You might look for original quantitative, mixed-method and qualitative studies, or reviews such as quantitative meta-analyses or qualitative meta-syntheses. These findings would give you a picture of the empirical knowledge gap and the qualitative research questions that might lead to relevant and new insights and useful theories, models or concepts for studying your topic. When little knowledge is available, a qualitative study can be a useful starting point for subsequent studies. If in preparing your qualitative study, you cannot find sufficient literature about your topic, you might turn to proxy literature to explore the landscape around your topic. For example, when you are one of the very first researchers to study shared decision-making or health literacy in maternity care for disadvantaged parents-to-be, you might search for existing literature on these topics in other healthcare settings, such as general practice.

Searching the literature for qualitative studies: the SPIDER tool. Based on Cooke et al. [ 3 ].

| S | : qualitative research uses smaller samples, as findings are not intended to be generalized to the general population. |

| PI | : qualitative research examines how and why certain experiences, behaviours and decisions occur (in contrast to the effectiveness of intervention). |

| D | : refers to the theoretical framework and the corresponding method used, which influence the robustness of the analysis and findings. |

| E | : evaluation outcomes may include more subjective outcomes (views, attitudes, perspectives, experiences, etc.). |

| R | : qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods research could be searched for. |

Why do qualitative researchers prefer SPIDER to PICO?

The SPIDER tool (sample-phenomenon of interest-design-evaluation-research type) ( Box 1 ) is one of the available tools for qualitative literature searches [ 3 ]. It has been specifically developed for qualitative evidence synthesis, making it more suitable than PICO (population-intervention-comparison-outcome) in searching for qualitative studies that focus on understanding real-life experiences and processes of a variety of participants. PICO is primarily a tool for collecting evidence from published quantitative research on prognoses, diagnoses and therapies. Quantitative studies mostly use larger samples, comparing intervention and control groups, focusing on quantification of predefined outcomes at group level that can be generalized to larger populations. In contrast, qualitative research studies smaller samples in greater depth; it strives to minimalize manipulating their natural settings and is open to rich and unexpected findings. To suit this approach, the SPIDER tool was developed by adapting the PICO tool. Although these tools are meant for searching the literature, they can also be helpful in formulating research questions for original studies. Using SPIDER might support you in formulating a broad and open qualitative research question.

An example of an SPIDER-type question for a qualitative study using interviews is: ‘What are young parents’ experiences of attending antenatal education?’ The abstract and introduction of a manuscript might contain this broad and open research question, after which the methods section provides further operationalization of the elements of the SPIDER tool, such as (S) young mothers and fathers, aged 17–27 years, 1–12 months after childbirth, low to high educational levels, in urban or semi-urban regions; (PI) experiences of antenatal education in group sessions during pregnancy guided by maternity care professionals; (D) phenomenology, interviews; (E) perceived benefits and costs, psychosocial and peer support received, changes in attitude, expectations, and perceived skills regarding healthy lifestyle, childbirth, parenthood, etc.; and (R) qualitative.

Is it normal that my research question seems to change during the study?

During the research process, the research question might change to a certain degree because data collection and analysis sharpens the researcher’s lenses. Data collection and analysis are iterative processes that happen simultaneously as the research progresses. This might lead to a somewhat different focus of your research question and to additional questions. However, you cannot radically change your research question because that would mean you were performing a different study. In the methods section, you need to describe how and explain why the original research question was changed.

For example, let us return to the problem that GPs are hesitant to ask about intimate partner violence despite their awareness of family violence. To design a qualitative study, you might use SPIDER to support you in formulating your research question. You purposefully sample GPs, varying in age, gender, years of experience and type of practice (S-1). You might also decide to sample patients, in a variety of life situations, who have been faced with the problem (S-2). You clarify the phenomenon of family violence, which might be broadly defined when you design your study—e.g. family abuse and violence (PI-1). However, as your study evolves you might feel the need for fine-tuning—e.g. asking about intimate partner violence (PI-2). You describe the design, for instance, a phenomenological study using interviews (D), as well as the ‘think, feel or do’ elements you want to evaluate in your qualitative research. Depending on what is already known and the aim of your research, you might choose to describe actual behaviour and experiences (E-1) or explore attitudes and perspectives (E-2). Then, as your study progresses, you also might want to explain communication and follow-up processes (E-3) in your qualitative research (R).

Each of your choices will be a trade-off between the intended variety, depth and richness of your findings and the required samples, methods, techniques and efforts for data collection and analyses. These choices lead to different research questions, for example:

- ‘What are GPs’ and patients’ attitudes and perspectives towards discussing family abuse and violence?’ Or:

- ‘How do GPs behave during the communication and follow-up process when a patient’s signals suggest intimate partner violence?’

Designing qualitative studies

How do i choose a qualitative design.

As in quantitative research, you base the choice of a qualitative design primarily on the nature of the research problem, the research question and the scientific knowledge you seek. Therefore, instead of simply choosing what seems easy or interesting, it is wiser to first consider and discuss with other qualitative researchers the pros and cons of different designs for your study. Then, depending on your skills and your knowledge and understanding of qualitative methodology and your research topic, you might seek training or support from other qualitative researchers. Finally, just as in quantitative research, the resources and time available and your access to the study settings and participants also influence the choices you make in designing the study.

What are the most important qualitative designs?

Ethnography [ 4 ], phenomenology [ 5 ], and grounded theory [ 6 ] are considered the ‘big three’ qualitative approaches [ 7 ] ( Box 2 ). Box 2 shows that they stem from different theoretical disciplines and are used in various domains focusing on different areas of inquiry. Furthermore, qualitative research has a rich tradition of various designs [ 2 ]. Box 3 presents other qualitative approaches such as case studies [ 8 ], conversation analysis [ 9 ], narrative research [ 10 ], hermeneutic research [ 11 ], historical research [ 12 ], participatory action research and [ 13 ], participatory community research [ 14 ], and research based on critical social theory [ 15 ], for example, feminist research or empowerment evaluation [ 16 ]. Some researchers do not mention a specific qualitative approach or research tradition but use a descriptive generic research [ 17 ] or say that they used thematic analysis or content analysis, an analysis of themes and patterns that emerge in the narrative content from a qualitative study [ 2 ]. This form of data analysis will be addressed in Part 3 of our series.

The ‘big three’ approaches in qualitative study design. Based on Polit and Beck [ 2 ].

Definitions of other qualitative research approaches. Based on Polit and Beck [ 2 ].

| Ethnography | Phenomenology | Grounded theory | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | A branch of human enquiry, associated with anthropology that focuses on the culture of a group of people, with an effort to understand the world view of those under study. | A qualitative research tradition, with roots in philosophy and psychology, that focuses on the lived experience of humans. | A qualitative research methodology with roots in sociology that aims to develop theories grounded in real-world observations. |

| Discipline | Anthropology | Psychology, philosophy | Sociology |

| Domain | Culture | Lived experience | Social settings |

| Area of inquiry | Holistic view of a culture. | Experiences of individuals within their experiential world or ‘life-world’. | Social structural process within a social setting. |

| Focus | Understanding the meanings and behaviours associated with the membership of groups, teams, etc. | Exploring how individuals make sense of the world to provide insightful accounts of their subjective experience. | Building theories about social phenomena. |

| Case study | A research method involving a thorough, in-depth analysis of an individual, group or other social unit. |

| Conversation analysis | Form of discourse analysis, a qualitative tradition from the discipline of sociolinguistics that seeks to understand the rules, mechanisms, and structure of conversations. |

| Critical social theory | An approach to viewing the world that involves a critique of society, with the goal of envisioning new possibilities and effecting social change. |

| Feminist research | Research that seeks to understand, typically through qualitative approaches, how gender and a gendered social order shape women’s lives and their consciousness. |

| Hermeneutics | A qualitative research tradition, drawing on interpretative phenomenology that focuses on the lived experience of humans, and how they interpret those experiences. |

| Historical research | Systematic studies designed to discover facts and relationships about past events. |

| Narrative research | A narrative approach that focuses on the story as the object of the inquiry. |

| Participatory action research | A collaborative research approach between researchers and participants based on the premise that the production of knowledge can be political and used to exert power. |

| Community-based participatory research | A research approach that enlists those who are most affected by a community issue—typically in collaboration or partnership with others who have research skills—to conduct research on and analyse that issue, with the goal to resolve it. |

| Content analysis | The process or organizing and integrating material from documents, often-narrative information from a qualitative study, according to key concepts and themes. |

Depending on your research question, you might choose one of the ‘big three’ designs

Let us assume that you want to study the caring relationship in palliative care in a primary care setting for people with COPD. If you are interested in the care provided by family caregivers from different ethnic backgrounds, you will want to investigate their experiences. Your research question might be ‘What constitutes the caring relationship between GPs and family caregivers in the palliative care for people with COPD among family caregivers of Moroccan, Syrian, and Iranian ethnicity?’ Since you are interested in the caring relationship within cultural groups or subgroups, you might choose ethnography. Ethnography is the study of culture within a society, focusing on one or more groups. Data is collected mostly through observations, informal (ethnographic) conversations, interviews and/or artefacts. The findings are presented in a lengthy monograph where concepts and patterns are presented in a holistic way using context-rich description.

If you are interested in the experiential world or ‘life-world’ of the family caregivers and the impact of caregiving on their own lives, your research question might be ‘What is the lived experience of being a family caregiver for a family member with COPD whose end is near?’ In such a case, you might choose phenomenology, in which data are collected through in-depth interviews. The findings are presented in detailed descriptions of participants’ experiences, grouped in themes.

If you want to study the interaction between GPs and family caregivers to generate a theory of ‘trust’ within caring relationships, your research question might be ‘How does a relationship of trust between GPs and family caregivers evolve in end-of-life care for people with COPD?’ Grounded theory might then be the design of the first choice. In this approach, data are collected mostly through in-depth interviews, but may also include observations of encounters, followed by interviews with those who were observed. The findings presented consist of a theory, including a basic social process and relevant concepts and categories.

If you merely aim to give a qualitative description of the views of family caregivers about facilitators and barriers to contacting GPs, you might use content analysis and present the themes and subthemes you found.

What is the role of theory in qualitative research?

The role of theory is to guide you through the research process. Theory supports formulating the research question, guides data collection and analysis, and offers possible explanations of underlying causes of or influences on phenomena. From the start of your research, theory provides you with a ‘lens’ to look at the phenomenon under study. During your study, this ‘theoretical lens’ helps to focus your attention on specific aspects of the data and provides you with a conceptual model or framework for analysing them. It supports you in moving beyond the individual ‘stories’ of the participants. This leads to a broader understanding of the phenomenon of study and a wider applicability and transferability of the findings, which might help you formulate new theory, or advance a model or framework. Note that research does not need to be always theory-based, for example, in a descriptive study, interviewing people about perceived facilitators and barriers for adopting new behaviour.

What is my role as a researcher?

As a qualitative researcher, you influence the research process. Qualitative researchers and the study participants always interact in a social process. You build a relationship midst data collection, for the short-term in an interview, or for the long-term during observations or longitudinal studies. This influences the research process and its findings, which is why your report needs to be transparent about your perspective and explicitly acknowledge your subjectivity. Your role as a qualitative researcher requires empathy as well as distance. By empathy, we mean that you can put yourself into the participants’ situation. Empathy is needed to establish a trusting relationship but might also bring about emotional distress. By distance, we mean that you need to be aware of your values, which influence your data collection, and that you have to be non-judgemental and non-directive.

There is always a power difference between the researcher and participants. Especially, feminist researchers acknowledge that the research is done by, for, and about women and the focus is on gender domination and discrimination. As a feminist researcher, you would try to establish a trustworthy and non-exploitative relationship and place yourself within the study to avoid objectification. Feminist research is transformative to change oppressive structures for women [ 16 ].

What ethical issues do I need to consider?

Although qualitative researchers do not aim to intervene, their interaction with participants requires careful adherence to the statement of ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects as laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki [ 18 ]. It states that healthcare professionals involved in medical research are obliged to protect the life, health, dignity, integrity, right to self-determination, privacy and confidentiality of personal information of research subjects. The Declaration also warrants that all vulnerable groups and individuals should receive specifically considered protection. This is also relevant when working in contexts of low-income countries and poverty. Furthermore, researchers must consider the ethical, legal and regulatory norms and standards in their own countries, as well as applicable international norms and standards. You might contact your local Medical Ethics Committee before setting up your study. In some countries, Medical Ethics Committees do not review qualitative research [ 2 ]. In that case, you will have to adhere to the Declaration of Helsinki [ 18 ], and you might seek approval from a research committee at your institution or the board of your institution.

In qualitative research, you have to ensure anonymity by code numbering the tapes and transcripts and removing any identifying information from the transcripts. When you work with transcription offices, they will need to sign a confidentiality agreement. Even though the quotes from participants in your manuscripts are anonymized, you cannot always guarantee full confidentiality. Therefore, you might ask participants special permission for using these quotes in scientific publications.

The next article in this Series on qualitative research, Part 3, will focus on sampling, data collection, and analysis [ 19 ]. In the final article, Part 4, we address two overarching themes: trustworthiness and publishing [ 20 ].

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the following junior researchers who have been participating for the last few years in the so-called ‘Think tank on qualitative research’ project, a collaborative project between Zuyd University of Applied Sciences and Maastricht University, for their pertinent questions: Erica Baarends, Jerome van Dongen, Jolanda Friesen-Storms, Steffy Lenzen, Ankie Hoefnagels, Barbara Piskur, Claudia van Putten-Gamel, Wilma Savelberg, Steffy Stans, and Anita Stevens. The authors are grateful to Isabel van Helmond, Joyce Molenaar and Darcy Ummels for proofreading our manuscripts and providing valuable feedback from the ‘novice perspective’.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Pardon Our Interruption

As you were browsing something about your browser made us think you were a bot. There are a few reasons this might happen:

- You've disabled JavaScript in your web browser.

- You're a power user moving through this website with super-human speed.

- You've disabled cookies in your web browser.

- A third-party browser plugin, such as Ghostery or NoScript, is preventing JavaScript from running. Additional information is available in this support article .

To regain access, please make sure that cookies and JavaScript are enabled before reloading the page.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis

Affiliations.

- 1 a Faculty of Health Care, Research Centre Autonomy and Participation of Chronically Ill People , Zuyd University of Applied Sciences , Heerlen , The Netherlands.

- 2 b Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Department of Family Medicine , Maastricht University , Maastricht , The Netherlands.

- 3 c Faculty of Health Care, Research Centre for Midwifery Science , Zuyd University of Applied Sciences , Maastricht , The Netherlands.

- PMID: 29199486

- PMCID: PMC5774281

- DOI: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375091

In the course of our supervisory work over the years, we have noticed that qualitative research tends to evoke a lot of questions and worries, so-called frequently asked questions (FAQs). This series of four articles intends to provide novice researchers with practical guidance for conducting high-quality qualitative research in primary care. By 'novice' we mean Master's students and junior researchers, as well as experienced quantitative researchers who are engaging in qualitative research for the first time. This series addresses their questions and provides researchers, readers, reviewers and editors with references to criteria and tools for judging the quality of qualitative research papers. The second article focused on context, research questions and designs, and referred to publications for further reading. This third article addresses FAQs about sampling, data collection and analysis. The data collection plan needs to be broadly defined and open at first, and become flexible during data collection. Sampling strategies should be chosen in such a way that they yield rich information and are consistent with the methodological approach used. Data saturation determines sample size and will be different for each study. The most commonly used data collection methods are participant observation, face-to-face in-depth interviews and focus group discussions. Analyses in ethnographic, phenomenological, grounded theory, and content analysis studies yield different narrative findings: a detailed description of a culture, the essence of the lived experience, a theory, and a descriptive summary, respectively. The fourth and final article will focus on trustworthiness and publishing qualitative research.

Keywords: General practice/family medicine; analysis; data collection; general qualitative designs and methods; sampling.

PubMed Disclaimer

Conflict of interest statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Similar articles

- Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 2: Context, research questions and designs. Korstjens I, Moser A. Korstjens I, et al. Eur J Gen Pract. 2017 Dec;23(1):274-279. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375090. Eur J Gen Pract. 2017. PMID: 29185826 Free PMC article.

- Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. Korstjens I, Moser A. Korstjens I, et al. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018 Dec;24(1):120-124. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375092. Epub 2017 Dec 5. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018. PMID: 29202616 Free PMC article.

- Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 1: Introduction. Moser A, Korstjens I. Moser A, et al. Eur J Gen Pract. 2017 Dec;23(1):271-273. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375093. Eur J Gen Pract. 2017. PMID: 29185831 Free PMC article.

- Clinical research 4: qualitative data collection and analysis. Endacott R. Endacott R. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2005 Apr;21(2):123-7. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2004.10.001. Epub 2004 Nov 28. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2005. PMID: 15778077 Review.

- Qualitative research sampling: the very real complexities. Tuckett AG. Tuckett AG. Nurse Res. 2004;12(1):47-61. doi: 10.7748/nr2004.07.12.1.47.c5930. Nurse Res. 2004. PMID: 15493214 Review.

- Strabismic Adults' Experiences of Psychosocial Influence of Strabismus-A Qualitative Study. Mason A, Joronen K, Lindberg L, Kajander M, Fagerholm N, Rantanen A. Mason A, et al. SAGE Open Nurs. 2024 Sep 5;10:23779608241278456. doi: 10.1177/23779608241278456. eCollection 2024 Jan-Dec. SAGE Open Nurs. 2024. PMID: 39246297 Free PMC article.

- Nurses' perception about their role in reducing health inequalities in community contexts. Sotelo-Daza J, Jaramillo YE, Chacón MV. Sotelo-Daza J, et al. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2024 Aug 30;32:e4299. doi: 10.1590/1518-8345.7245.4299. eCollection 2024. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2024. PMID: 39230132 Free PMC article.

- Sample Size in Qualitative Research Using In-Depth Interviews: A View from The Associate Editor 12 Years Later. Dworkin SL. Dworkin SL. Arch Sex Behav. 2024 Sep 3. doi: 10.1007/s10508-024-02992-5. Online ahead of print. Arch Sex Behav. 2024. PMID: 39225844 No abstract available.

- Relevant factors affecting nurse staffing: a qualitative study from the perspective of nursing managers. Li G, Wang W, Pu J, Xie Z, Xu Y, Shen T, Huang H. Li G, et al. Front Public Health. 2024 Aug 14;12:1448871. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1448871. eCollection 2024. Front Public Health. 2024. PMID: 39220455 Free PMC article.

- ALLin4IPE- an international research study on interprofessional health professions education: a protocol for an ethnographic multiple-case study of practice architectures in sites of students' interprofessional clinical placements across four universities. Lindh Falk A, Abrandt Dahlgren M, Dahlberg J, Norbye B, Iversen A, Mansfield KJ, McKinlay E, Morgan S, Myers J, Gulliver L. Lindh Falk A, et al. BMC Med Educ. 2024 Aug 28;24(1):940. doi: 10.1186/s12909-024-05902-4. BMC Med Educ. 2024. PMID: 39198840 Free PMC article.

- Moser A, Korstjens I.. Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 1: Introduction. Eur J Gen Pract. 2017;23:271–273. - PMC - PubMed

- Korstjens I, Moser A.. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 2: Context, research questions and designs. Eur J Gen Pract. 2017;23:274–279. - PMC - PubMed

- Polit DF, Beck CT.. Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. 10th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2017.

- Moser A, van der Bruggen H, Widdershoven G.. Competency in shaping one’s life: Autonomy of people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in a nurse-led, shared-care setting; A qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43:417–427. - PubMed

- Moser A, Korstjens I, van der Weijden T, et al. . Patient’s decision making in selecting a hospital for elective orthopaedic surgery. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16:1262–1268. - PubMed

- Search in MeSH

Related information

- Cited in Books

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Europe PubMed Central

- PubMed Central

- Taylor & Francis

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Table of Contents

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Creating Trustworthy Guidelines

- Chapter 3: Overview of the Guideline Development Process

- Chapter 4: Formulating PICO Questions

- Chapter 5: Choosing and Ranking Outcomes

- Chapter 6: Systematic Review Overview

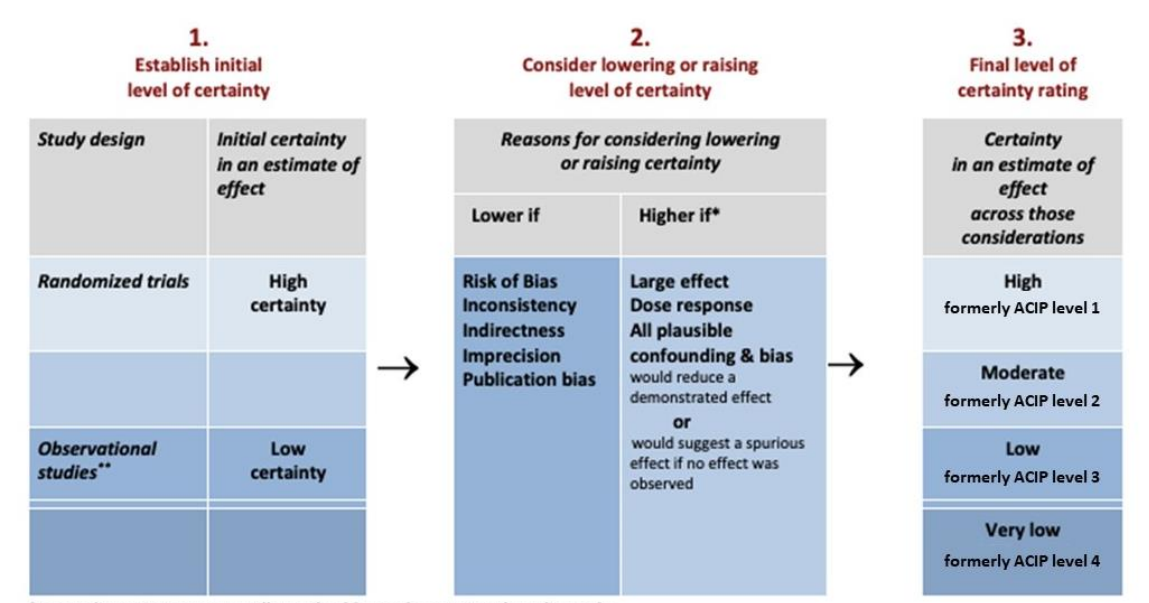

- Chapter 7: GRADE Criteria Determining Certainty of Evidence

- Chapter 8: Domains Decreasing Certainty in the Evidence

- Chapter 9: Domains Increasing One's Certainty in the Evidence

- Chapter 10: Overall Certainty of Evidence

- Chapter 11: Communicating findings from the GRADE certainty assessment

- Chapter 12: Integrating Randomized and Non-randomized Studies in Evidence Synthesis

Related Topics:

- Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)

- Vaccine-Specific Recommendations

- Evidence-Based Recommendations—GRADE

Chapter 7: GRADE Criteria Determining Certainty of Evidence