Four of the biggest problems facing education—and four trends that could make a difference

Eduardo velez bustillo, harry a. patrinos.

In 2022, we published, Lessons for the education sector from the COVID-19 pandemic , which was a follow up to, Four Education Trends that Countries Everywhere Should Know About , which summarized views of education experts around the world on how to handle the most pressing issues facing the education sector then. We focused on neuroscience, the role of the private sector, education technology, inequality, and pedagogy.

Unfortunately, we think the four biggest problems facing education today in developing countries are the same ones we have identified in the last decades .

1. The learning crisis was made worse by COVID-19 school closures

Low quality instruction is a major constraint and prior to COVID-19, the learning poverty rate in low- and middle-income countries was 57% (6 out of 10 children could not read and understand basic texts by age 10). More dramatic is the case of Sub-Saharan Africa with a rate even higher at 86%. Several analyses show that the impact of the pandemic on student learning was significant, leaving students in low- and middle-income countries way behind in mathematics, reading and other subjects. Some argue that learning poverty may be close to 70% after the pandemic , with a substantial long-term negative effect in future earnings. This generation could lose around $21 trillion in future salaries, with the vulnerable students affected the most.

2. Countries are not paying enough attention to early childhood care and education (ECCE)

At the pre-school level about two-thirds of countries do not have a proper legal framework to provide free and compulsory pre-primary education. According to UNESCO, only a minority of countries, mostly high-income, were making timely progress towards SDG4 benchmarks on early childhood indicators prior to the onset of COVID-19. And remember that ECCE is not only preparation for primary school. It can be the foundation for emotional wellbeing and learning throughout life; one of the best investments a country can make.

3. There is an inadequate supply of high-quality teachers

Low quality teaching is a huge problem and getting worse in many low- and middle-income countries. In Sub-Saharan Africa, for example, the percentage of trained teachers fell from 84% in 2000 to 69% in 2019 . In addition, in many countries teachers are formally trained and as such qualified, but do not have the minimum pedagogical training. Globally, teachers for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) subjects are the biggest shortfalls.

4. Decision-makers are not implementing evidence-based or pro-equity policies that guarantee solid foundations

It is difficult to understand the continued focus on non-evidence-based policies when there is so much that we know now about what works. Two factors contribute to this problem. One is the short tenure that top officials have when leading education systems. Examples of countries where ministers last less than one year on average are plentiful. The second and more worrisome deals with the fact that there is little attention given to empirical evidence when designing education policies.

To help improve on these four fronts, we see four supporting trends:

1. Neuroscience should be integrated into education policies

Policies considering neuroscience can help ensure that students get proper attention early to support brain development in the first 2-3 years of life. It can also help ensure that children learn to read at the proper age so that they will be able to acquire foundational skills to learn during the primary education cycle and from there on. Inputs like micronutrients, early child stimulation for gross and fine motor skills, speech and language and playing with other children before the age of three are cost-effective ways to get proper development. Early grade reading, using the pedagogical suggestion by the Early Grade Reading Assessment model, has improved learning outcomes in many low- and middle-income countries. We now have the tools to incorporate these advances into the teaching and learning system with AI , ChatGPT , MOOCs and online tutoring.

2. Reversing learning losses at home and at school

There is a real need to address the remaining and lingering losses due to school closures because of COVID-19. Most students living in households with incomes under the poverty line in the developing world, roughly the bottom 80% in low-income countries and the bottom 50% in middle-income countries, do not have the minimum conditions to learn at home . These students do not have access to the internet, and, often, their parents or guardians do not have the necessary schooling level or the time to help them in their learning process. Connectivity for poor households is a priority. But learning continuity also requires the presence of an adult as a facilitator—a parent, guardian, instructor, or community worker assisting the student during the learning process while schools are closed or e-learning is used.

To recover from the negative impact of the pandemic, the school system will need to develop at the student level: (i) active and reflective learning; (ii) analytical and applied skills; (iii) strong self-esteem; (iv) attitudes supportive of cooperation and solidarity; and (v) a good knowledge of the curriculum areas. At the teacher (instructor, facilitator, parent) level, the system should aim to develop a new disposition toward the role of teacher as a guide and facilitator. And finally, the system also needs to increase parental involvement in the education of their children and be active part in the solution of the children’s problems. The Escuela Nueva Learning Circles or the Pratham Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL) are models that can be used.

3. Use of evidence to improve teaching and learning

We now know more about what works at scale to address the learning crisis. To help countries improve teaching and learning and make teaching an attractive profession, based on available empirical world-wide evidence , we need to improve its status, compensation policies and career progression structures; ensure pre-service education includes a strong practicum component so teachers are well equipped to transition and perform effectively in the classroom; and provide high-quality in-service professional development to ensure they keep teaching in an effective way. We also have the tools to address learning issues cost-effectively. The returns to schooling are high and increasing post-pandemic. But we also have the cost-benefit tools to make good decisions, and these suggest that structured pedagogy, teaching according to learning levels (with and without technology use) are proven effective and cost-effective .

4. The role of the private sector

When properly regulated the private sector can be an effective education provider, and it can help address the specific needs of countries. Most of the pedagogical models that have received international recognition come from the private sector. For example, the recipients of the Yidan Prize on education development are from the non-state sector experiences (Escuela Nueva, BRAC, edX, Pratham, CAMFED and New Education Initiative). In the context of the Artificial Intelligence movement, most of the tools that will revolutionize teaching and learning come from the private sector (i.e., big data, machine learning, electronic pedagogies like OER-Open Educational Resources, MOOCs, etc.). Around the world education technology start-ups are developing AI tools that may have a good potential to help improve quality of education .

After decades asking the same questions on how to improve the education systems of countries, we, finally, are finding answers that are very promising. Governments need to be aware of this fact.

To receive weekly articles, sign-up here

Get updates from Education for Global Development

Thank you for choosing to be part of the Education for Global Development community!

Your subscription is now active. The latest blog posts and blog-related announcements will be delivered directly to your email inbox. You may unsubscribe at any time.

Consultant, Education Sector, World Bank

Senior Adviser, Education

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

Center for Teaching

Teaching problem solving.

Print Version

Tips and Techniques

Expert vs. novice problem solvers, communicate.

- Have students identify specific problems, difficulties, or confusions . Don’t waste time working through problems that students already understand.

- If students are unable to articulate their concerns, determine where they are having trouble by asking them to identify the specific concepts or principles associated with the problem.

- In a one-on-one tutoring session, ask the student to work his/her problem out loud . This slows down the thinking process, making it more accurate and allowing you to access understanding.

- When working with larger groups you can ask students to provide a written “two-column solution.” Have students write up their solution to a problem by putting all their calculations in one column and all of their reasoning (in complete sentences) in the other column. This helps them to think critically about their own problem solving and helps you to more easily identify where they may be having problems. Two-Column Solution (Math) Two-Column Solution (Physics)

Encourage Independence

- Model the problem solving process rather than just giving students the answer. As you work through the problem, consider how a novice might struggle with the concepts and make your thinking clear

- Have students work through problems on their own. Ask directing questions or give helpful suggestions, but provide only minimal assistance and only when needed to overcome obstacles.

- Don’t fear group work ! Students can frequently help each other, and talking about a problem helps them think more critically about the steps needed to solve the problem. Additionally, group work helps students realize that problems often have multiple solution strategies, some that might be more effective than others

Be sensitive

- Frequently, when working problems, students are unsure of themselves. This lack of confidence may hamper their learning. It is important to recognize this when students come to us for help, and to give each student some feeling of mastery. Do this by providing positive reinforcement to let students know when they have mastered a new concept or skill.

Encourage Thoroughness and Patience

- Try to communicate that the process is more important than the answer so that the student learns that it is OK to not have an instant solution. This is learned through your acceptance of his/her pace of doing things, through your refusal to let anxiety pressure you into giving the right answer, and through your example of problem solving through a step-by step process.

Experts (teachers) in a particular field are often so fluent in solving problems from that field that they can find it difficult to articulate the problem solving principles and strategies they use to novices (students) in their field because these principles and strategies are second nature to the expert. To teach students problem solving skills, a teacher should be aware of principles and strategies of good problem solving in his or her discipline .

The mathematician George Polya captured the problem solving principles and strategies he used in his discipline in the book How to Solve It: A New Aspect of Mathematical Method (Princeton University Press, 1957). The book includes a summary of Polya’s problem solving heuristic as well as advice on the teaching of problem solving.

Teaching Guides

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

- Faculty & Staff

Teaching problem solving

Strategies for teaching problem solving apply across disciplines and instructional contexts. First, introduce the problem and explain how people in your discipline generally make sense of the given information. Then, explain how to apply these approaches to solve the problem.

Introducing the problem

Explaining how people in your discipline understand and interpret these types of problems can help students develop the skills they need to understand the problem (and find a solution). After introducing how you would go about solving a problem, you could then ask students to:

- frame the problem in their own words

- define key terms and concepts

- determine statements that accurately represent the givens of a problem

- identify analogous problems

- determine what information is needed to solve the problem

Working on solutions

In the solution phase, one develops and then implements a coherent plan for solving the problem. As you help students with this phase, you might ask them to:

- identify the general model or procedure they have in mind for solving the problem

- set sub-goals for solving the problem

- identify necessary operations and steps

- draw conclusions

- carry out necessary operations

You can help students tackle a problem effectively by asking them to:

- systematically explain each step and its rationale

- explain how they would approach solving the problem

- help you solve the problem by posing questions at key points in the process

- work together in small groups (3 to 5 students) to solve the problem and then have the solution presented to the rest of the class (either by you or by a student in the group)

In all cases, the more you get the students to articulate their own understandings of the problem and potential solutions, the more you can help them develop their expertise in approaching problems in your discipline.

Want a daily email of lesson plans that span all subjects and age groups?

Subjects all subjects all subjects the arts all the arts visual arts performing arts value of the arts back business & economics all business & economics global economics macroeconomics microeconomics personal finance business back design, engineering & technology all design, engineering & technology design engineering technology back health all health growth & development medical conditions consumer health public health nutrition physical fitness emotional health sex education back literature & language all literature & language literature linguistics writing/composition speaking back mathematics all mathematics algebra data analysis & probability geometry measurement numbers & operations back philosophy & religion all philosophy & religion philosophy religion back psychology all psychology history, approaches and methods biological bases of behavior consciousness, sensation and perception cognition and learning motivation and emotion developmental psychology personality psychological disorders and treatment social psychology back science & technology all science & technology earth and space science life sciences physical science environmental science nature of science back social studies all social studies anthropology area studies civics geography history media and journalism sociology back teaching & education all teaching & education education leadership education policy structure and function of schools teaching strategies back thinking & learning all thinking & learning attention and engagement memory critical thinking problem solving creativity collaboration information literacy organization and time management back, filter by none.

- Elementary/Primary

- Middle School/Lower Secondary

- High School/Upper Secondary

- College/University

- TED-Ed Animations

- TED Talk Lessons

- TED-Ed Best of Web

- Under 3 minutes

- Under 6 minutes

- Under 9 minutes

- Under 12 minutes

- Under 18 minutes

- Over 18 minutes

- Algerian Arabic

- Azerbaijani

- Cantonese (Hong Kong)

- Chinese (Hong Kong)

- Chinese (Singapore)

- Chinese (Taiwan)

- Chinese Simplified

- Chinese Traditional

- Chinese Traditional (Taiwan)

- Dutch (Belgium)

- Dutch (Netherlands)

- French (Canada)

- French (France)

- French (Switzerland)

- Kurdish (Central)

- Luxembourgish

- Persian (Afghanistan)

- Persian (Iran)

- Portuguese (Brazil)

- Portuguese (Portugal)

- Spanish (Argentina)

- Spanish (Latin America)

- Spanish (Mexico)

- Spanish (Spain)

- Spanish (United States)

- Western Frisian

sort by none

- Longest video

- Shortest video

- Most video views

- Least video views

- Most questions answered

- Least questions answered

A street librarian's quest to bring books to everyone - Storybook Maze

Lesson duration 08:44

40,075 Views

How the US is destroying young people’s future - Scott Galloway

Lesson duration 18:38

5,826,036 Views

This piece of paper could revolutionize human waste

Lesson duration 05:35

2,801,712 Views

Can you solve the magical maze riddle?

Lesson duration 04:51

488,386 Views

How to clear icy roads, with science

Lesson duration 06:13

194,545 Views

How to make smart decisions more easily

Lesson duration 05:16

1,360,252 Views

Can you solve a mystery before Sherlock Holmes?

Lesson duration 05:17

534,338 Views

Can you solve the secret assassin society riddle?

Lesson duration 05:01

921,214 Views

How to overcome your mistakes

Lesson duration 04:52

1,060,641 Views

What the fossil fuel industry doesn't want you to know - Al Gore

Lesson duration 25:45

756,506 Views

Can you solve the cursed dice riddle?

Lesson duration 04:31

808,615 Views

How the water you flush becomes the water you drink

Lesson duration 05:23

403,325 Views

The growing megafire crisis — and how to contain it - George T. Whitesides

Lesson duration 10:42

57,216 Views

Can you solve the time traveling car riddle?

Lesson duration 05:18

704,886 Views

4 epidemics that almost happened (but didn't)

Lesson duration 06:26

397,774 Views

The return of Mongolia's "wild" horses

Lesson duration 04:53

213,222 Views

Whatever happened to the hole in the ozone layer?

Lesson duration 05:13

554,483 Views

The most important century in human history

Lesson duration 05:20

355,434 Views

This one weird trick will get you infinite gold

Lesson duration 05:08

1,180,402 Views

How to quit your job — without ruining your career - Gala Jackson

118,177 Views

How to design climate-resilient buildings - Alyssa-Amor Gibbons

Lesson duration 14:12

46,546 Views

The case for free, universal basic services - Aaron Bastani

Lesson duration 19:09

82,465 Views

Can you steal the most powerful wand in the wizarding world?

840,006 Views

How college loans exploit students for profit - Sajay Samuel

Lesson duration 11:49

229,902 Views

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Problem solving.

- Richard E. Mayer Richard E. Mayer University of California, Santa Barbara

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.860

- Published online: 30 October 2019

Problem solving refers to cognitive processing directed at achieving a goal when the problem solver does not initially know a solution method. A problem exists when someone has a goal but does not know how to achieve it. Problems can be classified as routine or non-routine, and as well-defined or ill-defined. The major cognitive processes in problem solving are representing, planning, executing, and monitoring. The major kinds of knowledge required for problem solving are facts, concepts, procedures, strategies, and beliefs. The theoretical approaches that have developed over the history of research on problem are associationism, Gestalt, and information processing. Each of these approaches involves fundamental issues in problem solving such as the nature of transfer, insight, and goal-directed heuristics, respectively. Some current research topics in problem solving include decision making, intelligence and creativity, teaching of thinking skills, expert problem solving, analogical reasoning, mathematical and scientific thinking, everyday thinking, and the cognitive neuroscience of problem solving. Common theme concerns the domain specificity of problem solving and a focus on problem solving in authentic contexts.

- problem solving

- decision making

- intelligence

- expert problem solving

- analogical reasoning

- mathematical thinking

- scientific thinking

- everyday thinking

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Education. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 19 September 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [195.190.12.77]

- 195.190.12.77

Character limit 500 /500

The global education challenge: Scaling up to tackle the learning crisis

- Download the policy brief

Subscribe to Global Connection

Alice albright alice albright chief executive officer - global partnership for education.

July 25, 2019

The following is one of eight briefs commissioned for the 16th annual Brookings Blum Roundtable, “2020 and beyond: Maintaining the bipartisan narrative on US global development.”

Addressing today’s massive global education crisis requires some disruption and the development of a new 21st-century aid delivery model built on a strong operational public-private partnership and results-based financing model that rewards political leadership and progress on overcoming priority obstacles to equitable access and learning in least developed countries (LDCs) and lower-middle-income countries (LMICs). Success will also require a more efficient and unified global education architecture. More money alone will not fix the problem. Addressing this global challenge requires new champions at the highest level and new approaches.

Key data points

In an era when youth are the fastest-growing segment of the population in many parts of the world, new data from the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) reveals that an estimated 263 million children and young people are out of school, overwhelmingly in LDCs and LMICs. 1 On current trends, the International Commission on Financing Education Opportunity reported in 2016 that, a far larger number—825 million young people—will not have the basic literacy, numeracy, and digital skills to compete for the jobs of 2030. 2 Absent a significant political and financial investment in their education, beginning with basic education, there is a serious risk that this youth “bulge” will drive instability and constrain economic growth.

Despite progress in gender parity, it will take about 100 years to reach true gender equality at secondary school level in LDCs and LMICs. Lack of education and related employment opportunities in these countries presents national, regional, and global security risks.

Related Books

Amar Bhattacharya, Homi Kharas, John W. McArthur

November 15, 2023

Geoffrey Gertz, Homi Kharas, Johannes F. Linn

September 12, 2017

Esther Care, Patrick Griffin

April 11, 2017

Among global education’s most urgent challenges is a severe lack of trained teachers, particularly female teachers. An additional 9 million trained teachers are needed in sub-Saharan Africa by 2030.

Refugees and internally displaced people, now numbering over 70 million, constitute a global crisis. Two-thirds of the people in this group are women and children; host countries, many fragile themselves, struggle to provide access to education to such people.

Highlighted below are actions and reforms that could lead the way toward solving the crisis:

- Leadership to jump-start transformation. The next U.S. administration should convene a high-level White House conference of sovereign donors, developing country leaders, key multilateral organizations, private sector and major philanthropists/foundations, and civil society to jump-start and energize a new, 10-year global response to this challenge. A key goal of this decadelong effort should be to transform education systems in the world’s poorest countries, particularly for girls and women, within a generation. That implies advancing much faster than the 100-plus years required if current programs and commitments remain as is.

- A whole-of-government leadership response. Such transformation of currently weak education systems in scores of countries over a generation will require sustained top-level political leadership, accompanied by substantial new donor and developing country investments. To ensure sustained attention for this initiative over multiple years, the U.S. administration will need to designate senior officials in the State Department, USAID, the National Security Council, the Office of Management and Budget, and elsewhere to form a whole-of-government leadership response that can energize other governments and actors.

- Teacher training and deployment at scale. A key component of a new global highest-level effort, based on securing progress against the Sustainable Development Goals and the Addis 2030 Framework, should be the training and deployment of 9 million new qualified teachers, particularly female teachers, in sub-Saharan Africa where they are most needed. Over 90 percent of the Global Partnership for Education’s education sector implementation grants have included investments in teacher development and training and 76 percent in the provision of learning materials.

- Foster positive disruption by engaging community level non-state actors who are providing education services in marginal areas where national systems do not reach the population. Related to this, increased financial and technical support to national governments are required to strengthen their non-state actor regulatory frameworks. Such frameworks must ensure that any non-state actors operate without discrimination and prioritize access for the most marginalized. The ideological divide on this issue—featuring a strong resistance by defenders of public education to tap into the capacities and networks of non-state actors—must be resolved if we are to achieve a rapid breakthrough.

- Confirm the appropriate roles for technology in equitably advancing access and quality of education, including in the initial and ongoing training of teachers and administrators, delivery of distance education to marginalized communities and assessment of learning, strengthening of basic systems, and increased efficiency of systems. This is not primarily about how various gadgets can help advance education goals.

- Commodity component. Availability of appropriate learning materials for every child sitting in a classroom—right level, right language, and right subject matter. Lack of books and other learning materials is a persistent problem throughout education systems—from early grades through to teaching colleges. Teachers need books and other materials to do their jobs. Consider how the USAID-hosted Global Book Alliance, working to address costs and supply chain issues, distribution challenges, and more can be strengthened and supported to produce the model(s) that can overcome these challenges.

Annual high-level stock take at the G-7. The next U.S. administration can work with G-7 partners to secure agreement on an annual stocktaking of progress against this new global education agenda at the upcoming G-7 summits. This also will help ensure sustained focus and pressure to deliver especially on equity and inclusion. Global Partnership for Education’s participation at the G-7 Gender Equality Advisory Council is helping ensure that momentum is maintained to mobilize the necessary political leadership and expertise at country level to rapidly step up progress in gender equality, in and through education. 3 Also consider a role for the G-20, given participation by some developing country partners.

Related Content

Jenny Perlman Robinson, Molly Curtiss Wyss

July 3, 2018

Michelle Kaffenberger

May 17, 2019

Ramya Vivekanandan

February 14, 2019

- “263 Million Children and Youth Are Out of School.” UNESCO UIS. July 15, 2016. http://uis.unesco.org/en/news/263-million-children-and-youth-are-out-school.

- “The Learning Generation: Investing in education for a changing world.” The International Commission on Financing Global Education Opportunity. 2016. https://report.educationcommission.org/downloads/.

- “Influencing the most powerful nations to invest in the power of girls.” Global Partnership for Education. March 12, 2019. https://www.globalpartnership.org/blog/influencing-most-powerful-nations-invest-power-girls.

Global Education

Global Economy and Development

August 2, 2024

June 20, 2024

Elyse Painter, Emily Gustafsson-Wright

January 5, 2024

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

current events conversation

What Students Are Saying About How to Improve American Education

An international exam shows that American 15-year-olds are stagnant in reading and math. Teenagers told us what’s working and what’s not in the American education system.

By The Learning Network

Earlier this month, the Program for International Student Assessment announced that the performance of American teenagers in reading and math has been stagnant since 2000 . Other recent studies revealed that two-thirds of American children were not proficient readers , and that the achievement gap in reading between high and low performers is widening.

We asked students to weigh in on these findings and to tell us their suggestions for how they would improve the American education system.

Our prompt received nearly 300 comments. This was clearly a subject that many teenagers were passionate about. They offered a variety of suggestions on how they felt schools could be improved to better teach and prepare students for life after graduation.

While we usually highlight three of our most popular writing prompts in our Current Events Conversation , this week we are only rounding up comments for this one prompt so we can honor the many students who wrote in.

Please note: Student comments have been lightly edited for length, but otherwise appear as they were originally submitted.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

7 big problems–and solutions–in education

Solving these problems could be a key step to boosting innovation

Education has 99 problems, but the desire to solve those problems isn’t one. But because we can’t cover 99 problems in one story, we’ll focus on seven, which the League of Innovative Schools identified as critical to educational innovation.

While these aren’t the only challenges that education faces today, these seven problems are often identified as roadblocks that prevent schools and districts from embracing innovation.

Problem No. 1: There exist a handful of obstacles that prevent a more competency-based education system

( Next page: Problems and solutions )

Today’s education system includes ingrained practices, including policy and decades-old methods, that prevent schools from moving to competency-based models.

Solutions to this problem include:

- Creating and making available educational resources on competency-based learning. These resources might be best practices, rubrics or tools, or research.

- Convening a coalition of League of Innovative Schools districts that are working to build successful competency-based models.

- Creating a technical solution for flexible tracking of competencies and credits.

Problem No. 2: Leadership doesn’t always support second-order change, and those in potential leadership roles, such as teachers and librarians, aren’t always empowered to help effect change.

- Promoting League of Innovative Schools efforts to enable second-order change leadership

- Creating a framework, to be used in professional development, that would target and explain second-order change leadership discussions

- Schedule panel discussions about second-order change leadership

Problem No. 3: Communities and cultures are resistant to change, including technology-based change

- Identifying new and engaging ways to share cutting-edge and tech-savvy best practices with school and district stakeholders and community members

- Involve business leaders in technology-rich schools and create school-business partnerships

- Look to influential organizations to spearhead national ed-tech awareness campaigns

Problem No. 4: Education budgets aren’t always flexible enough to support the cost, sustainability, or scalability of innovations

- Build relationships with local businesses and career academies, and create incentives for companies to hire students, in order to create a revenue stream for schools

- Look to competitive pricing and creative solutions

- Leaders must not be afraid to take risks and support the changes needed to bring about this kind of budgeting

Problem No. 5: Professional development in the U.S. is stale and outdated

- Identifying best practices from other industries or sectors, and learn more about adult learning

- Create a community for teachers to access immediate help

- Personalize professional development

- Create and strengthen K-12 and higher education partnerships

- Create alternative modes of certification and reward forward-thinking practices

Problem No. 6: School districts do not have evidence-based processes to evaluate, select, and monitor digital content inclusive of aligned formative assessments

- Creating a marketplace or database to help educators identify and evaluate, as well as take ownership of, digital content

- Involve students in digital content evaluation

- Identify schools or districts to test digital content evaluation and storage systems

Problem No. 7: Current and traditional instructional methods leave students less engaged and less inclined to take ownership of their learning

- Creating working groups, within education organizations, with the aim of advancing authentic student learning

- Leverage the internet to create online tools and resources that offer innovative teaching strategies to help engage students

- Help teachers understand and practice authentic teaching and learning to help students master skills and standards

Sign up for our K-12 newsletter

- Recent Posts

- Confronting chronic absenteeism - September 16, 2024

- Educators outline 5 priorities for the new school year - September 13, 2024

- Skills gap, outdated infrastructure hinder AI use - September 11, 2024

Want to share a great resource? Let us know at [email protected] .

Comments are closed.

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

" * " indicates required fields

eSchool News uses cookies to improve your experience. Visit our Privacy Policy for more information.

5 Big Challenges Facing K-12 Education Today—And Ideas for Tackling Them

- Share article

Big Ideas is Education Week’s annual special report that brings the expertise of our newsroom to bear on the challenges educators are facing in classrooms, schools, and districts.

In the report , EdWeek reporters ask hard questions about K-12 education’s biggest issues and offer insights based on their extensive coverage and expertise.

The goal is to question the status quo and explore opportunities to help build a better, more just learning environment for all students.

In the 2023 edition , our newsroom sought to dig deeper into new and persistent challenges. Our reporters consider some of the big questions facing the field: Why is teacher pay so stubbornly stalled? What should reading instruction look like? How do we integrate—or even think about—AI? What does it mean for parents to be involved in the decisionmaking around classroom curriculum? And, perhaps the most existential, what does it mean for schools to be “public”?

The reported essays below tackle these vexing and pressing questions. We hope they offer fodder for robust discussions.

To see how your fellow educator peers are feeling about a number of these issues, we invite you to explore the EdWeek Research Center’s survey of more than 1,000 teachers and school and district leaders .

Please connect with us on social media by using #K12BigIdeas or by emailing [email protected].

1. What Does It Actually Mean for Schools to Be Public?

Over years of covering school finance, Mark Lieberman keep running up against one nagging question: Does the way we pay for public schools inherently contradict what we understand the goal of public education to be? Read more →

2. Public Schools Rely on Underpaid Female Labor. It’s Not Sustainable

School districts are still operating largely as if the labor market for women hasn’t changed in the last half century, writes Alyson Klein. Read more →

3. Parents’ Rights Groups Have Mobilized. What Does It Mean for Students?

Libby Stanford has been covering the parents’ rights groups that have led the charge to limit teaching about race, sexuality, and gender. In her essay, she explores what happens to students who miss out on that instruction. Read more→

4. To Move Past the Reading Wars, We Must Understand Where They Started

When it comes to reading instruction, we keep having the same fights over and over again, writes Sarah Schwartz. That’s because, she says, we have a fundamental divide about what reading is and how to study it. Read more→

5. No, AI Won’t Destroy Education. But We Should Be Skeptical

Lauraine Langreo makes the case for using AI to benefit teaching and learning while being aware of its potential downsides. Read more→

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

- Chronicle Conversations

- Article archives

- Issue archives

- Join our mailing list

Recognizing and Overcoming Inequity in Education

About the author, sylvia schmelkes.

Sylvia Schmelkes is Provost of the Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico City.

22 January 2020 Introduction

I nequity is perhaps the most serious problem in education worldwide. It has multiple causes, and its consequences include differences in access to schooling, retention and, more importantly, learning. Globally, these differences correlate with the level of development of various countries and regions. In individual States, access to school is tied to, among other things, students' overall well-being, their social origins and cultural backgrounds, the language their families speak, whether or not they work outside of the home and, in some countries, their sex. Although the world has made progress in both absolute and relative numbers of enrolled students, the differences between the richest and the poorest, as well as those living in rural and urban areas, have not diminished. 1

These correlations do not occur naturally. They are the result of the lack of policies that consider equity in education as a principal vehicle for achieving more just societies. The pandemic has exacerbated these differences mainly due to the fact that technology, which is the means of access to distance schooling, presents one more layer of inequality, among many others.

The dimension of educational inequity

Around the world, 258 million, or 17 per cent of the world’s children, adolescents and youth, are out of school. The proportion is much larger in developing countries: 31 per cent in sub-Saharan Africa and 21 per cent in Central Asia, vs. 3 per cent in Europe and North America. 2 Learning, which is the purpose of schooling, fares even worse. For example, it would take 15-year-old Brazilian students 75 years, at their current rate of improvement, to reach wealthier countries’ average scores in math, and more than 260 years in reading. 3 Within countries, learning results, as measured through standardized tests, are almost always much lower for those living in poverty. In Mexico, for example, 80 per cent of indigenous children at the end of primary school don’t achieve basic levels in reading and math, scoring far below the average for primary school students. 4

The causes of educational inequity

There are many explanations for educational inequity. In my view, the most important ones are the following:

- Equity and equality are not the same thing. Equality means providing the same resources to everyone. Equity signifies giving more to those most in need. Countries with greater inequity in education results are also those in which governments distribute resources according to the political pressure they experience in providing education. Such pressures come from families in which the parents attended school, that reside in urban areas, belong to cultural majorities and who have a clear appreciation of the benefits of education. Much less pressure comes from rural areas and indigenous populations, or from impoverished urban areas. In these countries, fewer resources, including infrastructure, equipment, teachers, supervision and funding, are allocated to the disadvantaged, the poor and cultural minorities.

- Teachers are key agents for learning. Their training is crucial. When insufficient priority is given to either initial or in-service teacher training, or to both, one can expect learning deficits. Teachers in poorer areas tend to have less training and to receive less in-service support.

- Most countries are very diverse. When a curriculum is overloaded and is the same for everyone, some students, generally those from rural areas, cultural minorities or living in poverty find little meaning in what is taught. When the language of instruction is different from their native tongue, students learn much less and drop out of school earlier.

- Disadvantaged students frequently encounter unfriendly or overtly offensive attitudes from both teachers and classmates. Such attitudes are derived from prejudices, stereotypes, outright racism and sexism. Students in hostile environments are affected in their disposition to learn, and many drop out early.

It doesn’t have to be like this

When left to inertial decision-making, education systems seem to be doomed to reproduce social and economic inequity. The commitment of both governments and societies to equity in education is both necessary and possible. There are several examples of more equitable educational systems in the world, and there are many subnational examples of successful policies fostering equity in education.

Why is equity in education important?

Education is a basic human right. More than that, it is an enabling right in the sense that, when respected, allows for the fulfillment of other human rights. Education has proven to affect general well-being, productivity, social capital, responsible citizenship and sustainable behaviour. Its equitable distribution allows for the creation of permeable societies and equity. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development includes Sustainable Development Goal 4, which aims to ensure “inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”. One hundred eighty-four countries are committed to achieving this goal over the next decade. 5 The process of walking this road together has begun and requires impetus to continue, especially now that we must face the devastating consequences of a long-lasting pandemic. Further progress is crucial for humanity.

Notes 1 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization , Inclusive Education. All Means All , Global Education Monitoring Report 2020 (Paris, 2020), p.8. Available at https://en.unesco.org/gem-report/report/2020/inclusion . 2 Ibid., p. 4, 7. 3 World Bank Group, World Development Report 2018: Learning to Realize Education's Promise (Washington, DC, 2018), p. 3. Available at https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2018 . 4 Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación, "La educación obligatoria en México", Informe 2018 (Ciudad de México, 2018), p. 72. Available online at https://www.inee.edu.mx/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/P1I243.pdf . 5 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization , “Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action for the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4” (2015), p. 23. Available at https://iite.unesco.org/publications/education-2030-incheon-declaration-framework-action-towards-inclusive-equitable-quality-education-lifelong-learning/ The UN Chronicle is not an official record. It is privileged to host senior United Nations officials as well as distinguished contributors from outside the United Nations system whose views are not necessarily those of the United Nations. Similarly, the boundaries and names shown, and the designations used, in maps or articles do not necessarily imply endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

Improving Diagnosis for Patient Safety: A Global Imperative for Health Systems

States are increasingly recognizing the importance of ensuring access to safe diagnostic tools and services, towards avoiding preventable harm and achieving positive patient outcomes.

How International Cooperation in Policing Promotes Peace and Security

The role of international policing is closely aligned with the principles of justice, peace, democracy and human rights, and is integral to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Voices for Peace: The Crucial Role of Victims of Terrorism as Peace Advocates and Educators

In the face of unimaginable pain and trauma, victims and survivors of terrorism emerge as strong advocates for community resilience, solidarity and peaceful coexistence.

Documents and publications

- Yearbook of the United Nations

- Basic Facts About the United Nations

- Journal of the United Nations

- Meetings Coverage and Press Releases

- United Nations Official Document System (ODS)

- Africa Renewal

Libraries and Archives

- Dag Hammarskjöld Library

- UN Audiovisual Library

- UN Archives and Records Management

- Audiovisual Library of International Law

- UN iLibrary

News and media

- UN News Centre

- UN Chronicle on Twitter

- UN Chronicle on Facebook

The UN at Work

- 17 Goals to Transform Our World

- Official observances

- United Nations Academic Impact (UNAI)

- Protecting Human Rights

- Maintaining International Peace and Security

- The Office of the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth

- United Nations Careers

The Education Crisis: Being in School Is Not the Same as Learning

First grade students in Pakistan’s Balochistan Province are learning the alphabet through child-friendly flash cards. Their learning materials help educators teach through interactive and engaging activities and are provided free of charge through a student’s first learning backpack. © World Bank

THE NAME OF THE DOG IS PUPPY. This seems like a simple sentence. But did you know that in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda, three out of four third grade students do not understand it? The world is facing a learning crisis . Worldwide, hundreds of millions of children reach young adulthood without even the most basic skills like calculating the correct change from a transaction, reading a doctor’s instructions, or understanding a bus schedule—let alone building a fulfilling career or educating their children. Education is at the center of building human capital. The latest World Bank research shows that the productivity of 56 percent of the world’s children will be less than half of what it could be if they enjoyed complete education and full health. For individuals, education raises self-esteem and furthers opportunities for employment and earnings. And for a country, it helps strengthen institutions within societies, drives long-term economic growth, reduces poverty, and spurs innovation.

One of the most interesting, large scale educational technology efforts is being led by EkStep , a philanthropic effort in India. EkStep created an open digital infrastructure which provides access to learning opportunities for 200 million children, as well as professional development opportunities for 12 million teachers and 4.5 million school leaders. Both teachers and children are accessing content which ranges from teaching materials, explanatory videos, interactive content, stories, practice worksheets, and formative assessments. By monitoring which content is used most frequently—and most beneficially—informed decisions can be made around future content.

In the Dominican Republic, a World Bank supported pilot study shows how adaptive technologies can generate great interest among 21st century students and present a path to supporting the learning and teaching of future generations. Yudeisy, a sixth grader participating in the study, says that what she likes doing the most during the day is watching videos and tutorials on her computer and cell phone. Taking childhood curiosity as a starting point, the study aimed to channel it towards math learning in a way that interests Yudeisy and her classmates.

Yudeisy, along with her classmates in a public elementary school in Santo Domingo, is part of a four-month pilot to reinforce mathematics using software that adapts to the math level of each student. © World Bank

Adaptive technology was used to evaluate students’ initial learning level to then walk them through math exercises in a dynamic, personalized way, based on artificial intelligence and what the student is ready to learn. After three months, students with the lowest initial performance achieved substantial improvements. This shows the potential of technology to increase learning outcomes, especially among students lagging behind their peers. In a field that is developing at dizzying speeds, innovative solutions to educational challenges are springing up everywhere. Our challenge is to make technology a driver of equity and inclusion and not a source of greater inequality of opportunity. We are working with partners worldwide to support the effective and appropriate use of educational technologies to strengthen learning.

When schools and educations systems are managed well, learning happens

Successful education reforms require good policy design, strong political commitment, and effective implementation capacity . Of course, this is extremely challenging. Many countries struggle to make efficient use of resources and very often increased education spending does not translate into more learning and improved human capital. Overcoming such challenges involves working at all levels of the system.

At the central level, ministries of education need to attract the best experts to design and implement evidence-based and country-specific programs. District or regional offices need the capacity and the tools to monitor learning and support schools. At the school level, principals need to be trained and prepared to manage and lead schools, from planning the use of resources to supervising and nurturing their teachers. However difficult, change is possible. Supported by the World Bank, public schools across Punjab in Pakistan have been part of major reforms over the past few years to address these challenges. Through improved school-level accountability by monitoring and limiting teacher and student absenteeism, and the introduction of a merit-based teacher recruitment system, where only the most talented and motivated teachers were selected, they were able to increase enrollment and retention of students and significantly improve the quality of education. "The government schools have become very good now, even better than private ones," said Mr. Ahmed, a local villager.

The World Bank, along with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the UK’s Department for International Development, is developing the Global Education Policy Dashboard . This new initiative will provide governments with a system for monitoring how their education systems are functioning, from learning data to policy plans, so they are better able to make timely and evidence-based decisions.

Education reform: The long game is worth it

In fact, it will take a generation to realize the full benefits of high-quality teachers, the effective use of technology, improved management of education systems, and engaged and prepared learners. However, global experience shows us that countries that have rapidly accelerated development and prosperity all share the common characteristic of taking education seriously and investing appropriately. As we mark the first-ever International Day of Education on January 24, we must do all we can to equip our youth with the skills to keep learning, adapt to changing realities, and thrive in an increasingly competitive global economy and a rapidly changing world of work.

The schools of the future are being built today. These are schools where all teachers have the right competencies and motivation, where technology empowers them to deliver quality learning, and where all students learn fundamental skills, including socio-emotional, and digital skills. These schools are safe and affordable to everyone and are places where children and young people learn with joy, rigor, and purpose. Governments, teachers, parents, and the international community must do their homework to realize the promise of education for all students, in every village, in every city, and in every country.

The Bigger Picture: In-depth stories on ending poverty

Asian Development Blog Straight Talk from Development Experts

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Education is in Crisis: How Can Technology be Part of the Solution?

By Paul Vandenberg , Kirsty Newman , Milan Thomas

Digital technologies and EdTech could play a role in addressing the learning crisis underway in Asia and the Pacific.

A learning crisis affects many developing countries in Asia. Millions of children attend school but are not learning enough. They cannot read, write, or do mathematics at their grade level, and yet they pass to the next grade, learning even less because they have not grasped the previous material. The magnitude of the crisis is staggering: in low- and middle-income countries more than half of children are not learning to read by age 10.

At the same time, there is an emerging revolution in learning brought on by digital technologies . These are collectively referred to as educational technology or EdTech . The coincident emergence of a problem in education and a new approach to learning naturally makes us ask how one may be a solution for the other.

Edtech may be one part of the solution – but it should be a means not an end. Our guiding principle should be to first diagnose what is going wrong in a system and then identify which solutions are best suited to solve those problems.

Some causes of the learning crisis are well understood. The poor quality of teaching is a key factor. Teachers often lack subject knowledge and have not had adequate training. There are ways in which technology could address this – and so EdTech may be equally valuable in teaching teachers as it is in teaching students. By offering distance learning, EdTech can provide in-service training or combine online and in-person training (blended learning).

There is also evidence that teachers need better incentives. The idea is that that they can teach well but are not motivated to do so. It is not clear how EdTech can address this problem. Digitized school management systems could better track teacher performance (by tracking their students’ performance) and then linking to pay or other incentives. However, the main need is to design the incentive system; digital applications may only make that system more efficient.

Computer-assisted learning is the direct means by which EdTech can help students. It can be seen as a partial solution for two fundamental learning crisis problems: addressing students at different learning levels and completing the syllabus. A classroom contains students with a range of baseline learning levels and teachers are often incentivized to teach to the upper stratum, leaving many students behind. Furthermore, teachers are pressured to cover the syllabus by year’s end. They move on to new material even if students have not mastered previous lessons. This also leaves students behind.

The solution to both problems is, of course, more tailored teaching, but a teacher is hard-pressed to provide one-on-one tutoring to 30 or 40 kids. EdTech might help provide one-to-one instruction (e.g., one student to one tablet) so pupils can learn at their own level and pace. The evidence from rigorous assessments (largely in the United States) is that packages that use artificial intelligence to adjust to a student’s level can improve results, especially in math.

However, we need to be cautious. Most of the evidence comes from contexts in which the quality of teaching is already quite good and is much above the average in developing countries. Digital systems can also help increase the efficiency of formative assessment and make it more likely that such assessment will be conducted. Tracking of students’ learning, through data collection and analysis, can help to better monitor a student’s learning level and provide level-appropriate teaching and remediation.

Computer-assisted learning is the direct means by which EdTech can help students.

Edtech software, introduced in conjunction with other reforms, holds some promise. One notable success is Mindspark in India , which improves math and Hindi learning. It has been evaluated as an after-hours supplement and combined with human teaching assistance. More assessments of programs would be helpful.

There is also evidence that low-tech interventions for “teaching at the right level" can also have large impacts on learning. Careful analysis is needed to determine whether high-tech or low-tech solutions are best, given that low tech is less costly, and finance is a constraint in poor countries.

The COVID-19 pandemic has given a big push to EdTech. We can learn from these experiences but need to keep them in context. EdTech is being used to overcome the need to social distance. Teachers are teaching by video but not necessarily teaching better than when standing in front of a classroom. Zoom fatigue is a problem. More mass open online courses are being offered and are being taken up – but much of this is not for basic education and therefore does not address the learning crisis.

Supporting EdTech solutions comes with four caveats. First, new initiatives need to be well-designed to address specific weaknesses. Low-quality teacher training delivered partially online is no better than low-quality in-person training. The same applies to computer-assisted learning.

Second, computer-assisted learning is often used in schools or in after-hours programs at or near schools. Delivering as distance learning is trickier. It requires hardware and connectivity at home, which is not available to children in low-income households in developing countries and even developed ones.

Third, EdTech programs used outside normal classroom hours adds to the time children spend learning. This is good but it is not always clear whether the benefits are coming from EdTech, per se, or simply more time spent learning. Nonetheless, gamification and other techniques may make children want to spend more time learning.

Finally, let us keep in mind that good learning outcomes can be achieved without EdTech. Developed countries got results before the advent of EdTech. So too did good schools in developing countries.

To be effective, EdTech must address key causes of the crisis and be part of a larger package of reforms. Those reforms include teacher training, incentives, monitoring, teaching at the right level, remediation for underperforming students, and others.

Digital technologies have changed our lives in many ways, mostly for the good. EdTech could do the same by playing a role in addressing the learning crisis.

Published: 23 July 2021

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Never miss a blog post. Get updates on development in Asia and the Pacific into your mailbox.

Straight Talk in Your Inbox

Adb blog team, browse adb.org, other adb sites.

ADB encourages websites and blogs to link to its web pages.

World leading higher education information and services Home News Blogs Courses Jobs function vqTrackId(){return'0a14b8cb-e32a-4bc4-ab7d-ff2b3cfe7090';}(function(d,e){var el=d.createElement(e);el.sa=function(an,av){this.setAttribute(an,av);return this;};el.sa('id','vq_tracking').sa('src','//t.visitorqueue.com/p/tracking.min.js?id='+vqTrackId()).sa('async',1).sa('data-id',vqTrackId());d.getElementsByTagName(e)[0].parentNode.appendChild(el);})(document,'script'); function vqTrackPc(){return 1;} (function(d,e){var el=d.createElement(e);el.sa=function(an,av){this.setAttribute(an,av);return this;};el.sa('id','vq_personalisation').sa('src','//personalisation.visitorqueue.com/p/personalisation.min.js?id='+vqTrackId()).sa('async',1).sa('data-id',vqTrackId());d.getElementsByTagName(e)[0].parentNode.appendChild(el);})(document,'script');

Top 8 modern education problems and ways to solve them.

| September 15, 2017 | 0 responses

In many ways, today’s system is better than the traditional one. Technology is the biggest change and the greatest advantage at the same time. Various devices, such as computers, projectors, tablets and smartphones, make the process of learning simpler and more fun. The Internet gives both students and teachers access to limitless knowledge.

However, this is not the perfect educational system. It has several problems, so we have to try to improve it.

- Problem: The Individual Needs of Low-Achievers Are Not Being Addressed

Personalized learning is the most popular trend in education. The educators are doing their best to identify the learning style of each student and provide training that corresponds to their needs.

However, many students are at risk of falling behind, especially children who are learning mathematics and reading. In the USA, in particular, there are large gaps in science achievements by middle school.

Solution: Address the Needs of Low-Achievers

The educators must try harder to reduce the number of students who are getting low results on long-term trajectories. If we identify these students at an early age, we can provide additional training to help them improve the results.

- Problem: Overcrowded Classrooms

In 2016, there were over 17,000 state secondary school children in the UK being taught in classes of 36+ pupils.

Solution: Reduce the Number of Students in the Classroom

Only a smaller class can enable an active role for the student and improve the level of individual attention they get from the teacher.

- Problem: The Teachers Are Expected to Entertain

Today’s generations of students love technology, so the teachers started using technology just to keep them engaged. That imposes a serious issue: education is becoming an entertainment rather than a learning process.

Solution: Set Some Limits

We don’t have to see education as opposed to entertainment. However, we have to make the students aware of the purpose of technology and games in the classroom. It’s all about learning.

- Problem: Not Having Enough Time for Volunteering in University

The students are overwhelmed with projects and assignments. There is absolutely no space for internships and volunteering in college .

Solution: Make Internships and Volunteering Part of Education

When students graduate, a volunteering activity can make a great difference during the hiring process. In addition, these experiences help them develop into complete persons. If the students start getting credits for volunteering and internships, they will be willing to make the effort.

- Problem: The Parents Are Too Involved

Due to the fact that technology became part of the early educational process, it’s necessary for the parents to observe the way their children use the Internet at home. They have to help the students to complete assignments involving technology.

What about those parents who don’t have enough time for that? What if they have time, but want to use it in a different way?

Solution: Stop Expecting Parents to Act Like Teachers at Home

The parent should definitely support their child throughout the schooling process. However, we mustn’t turn this into a mandatory role. The teachers should stop assigning homework that demands parental assistance.

- Problem: Outdated Curriculum

Although we transformed the educational system, many features of the curriculum remained unchanged.

Solution: Eliminate Standardised Exams

This is a radical suggestion. However, standardised exams are a big problem. We want the students to learn at their own pace. We are personalizing the process of education. Then why do we expect them to compete with each other and meet the same standards as everyone else? The teacher should be the one responsible of grading.

- Problem: Not All Teachers Can Meet the Standards of the New Educational System

Can we really expect all teachers to use technology? Some of them are near the end of their teaching careers and they have never used tablets in the lecturing process before.

Solution: Provide Better Training for the Teachers

If we want all students to receive high-quality education based on the standards of the system, we have to prepare the teachers first. They need more training, preparation, and even tests that prove they can teach today’s generations of students.

- Problem: Graduates Are Not Ready for What Follows

A third of the employers in the UK are not happy with the performance of recent graduates. That means the system is not preparing them well for the challenges that follow.

Solution: More Internships, More Realistic Education

Practical education – that’s a challenge we still haven’t met. We have to get more practical.

The evolution of the educational system is an important process. Currently, we have a system that’s more suitable to the needs of generations when compared to the traditional system. However, it’s still not perfect. The evolution never stops.

Author Bio: Chris Richardson is a journalist, editor, and a blogger. He loves to write, learn new things, and meet new outgoing people. Chris is also fond of traveling, sports, and playing the guitar. Follow him on Facebook and Google+ .

Tags: solutions

Higher Ed unions offer vision for colleges and universities

Eleven union organizations representing hundreds of thousands of faculty and staff at colleges and universities raised their voices Sept. 16 in a historic alliance of purpose, amplifying a vision of higher education for the public good and calling on the Harris-Walz ticket to join them in creating the policy changes necessary to attain it.

In a letter to Vice President Kamala Harris , the coalition, including the AFT, pointed out the crucial connection between higher education and democracy and called for full funding, affordability and access, sustainable working conditions for higher education employees, and a secretary of education with a “clear record” of supporting higher education as a public good.

“As unions representing U.S. higher education workers, we look forward to working with you and our elected partners to rebuild this country’s higher education system as a public good that works for students, workers, and communities,” the letter reads, before listing specific actions to reach that goal.

Recounting the problem, offering real solutions

“Higher education is under attack,” said Todd Wolfson, president of the American Association of University Professors, at a press conference at the Community College of Philadelphia on Sept. 16. Recounting all the ways colleges and universities have struggled in recent years, he pointed to 50 years of defunding, skyrocketing tuition, trillions in student debt and institutional debt, a lack of job security for workers, and “mission drift,” when administrators forget their core purpose: “teaching the next generation; creating critical, cutting-edge research; and serving our communities.”

Wolfson and his colleagues have an alternative vision of public colleges and universities “that are fully funded, and where everyone has access, no one will leave our campuses with a mountain of debt, and all of our workers are going to have real job security and an end to ‘adjunctification,’” a reference to how the majority of faculty are adjuncts—lower-paid professors with short-term contracts and little job security.

“If colleges are supposed to be about how we create innovation and research and [to be] an engine of the economy, and their teachers are running around cobbling jobs together trying to avoid pauperization, how are we actually being the engine of the economy, how are we being the anchor of democracy?” asked AFT President Randi Weingarten. Higher education’s over-reliance on adjuncts “needs to end. This coalition is fighting against it.”

Weingarten talked about the AFT’s particular commitment to academic freedom, accessibility and affordability, adding that she is “glad that the Harris-Walz campaign … believes in this coalition’s principals” and understands that its “rock solid, common good” principals will “really achieve the promise of America.”

Drilling down to specifics

The coalition has specific asks of elected or campaigning officials. The “key issues” listed below are taken directly from the letter to Harris, with paraphrased descriptions:

- Full federal funding of public higher education Funding incentives for full-time, secure, in-sourced employment and prevention of layoffs; an increase in federal research funding; support for minority-serving institutions; and a commitment to open-enrollment institutions.

- Expand access to higher education End student debt and enact comprehensive immigration reform to remove barriers for undocumented and international students and workers.

- Sustainable working conditions for higher education employees Pass the Public Service Freedom to Negotiate Act to protect the right to organize unions, and recognize the free expression of ideas; and ensure equitable salaries, benefits, and job protections for low-wage, part-time, unbenefited, subcontracted and temporary workers.

- Select a Secretary of Education who demonstrates a clear record of supporting higher education as a truly public good.

Unions and organizations participating in the action were the AAUP; the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees; the AFT; the Communications Workers of America; the United Auto Workers; the Office and Professional Employees International Union; Higher Ed Labor Unite; the National Education Association; the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America; UNITE Here; and the Service Employees International Union. As HELU’s statement noted, it represents community colleges, technical schools, and state colleges and research universities, including historically Black colleges and universities, Hispanic-serving institutions, Native American-serving nontribal institutions and minority-serving institutions.

[Virginia Myers]

Community Member

First time visit profile message with url to edit your profile

Choose content type

Create a post from the types below.

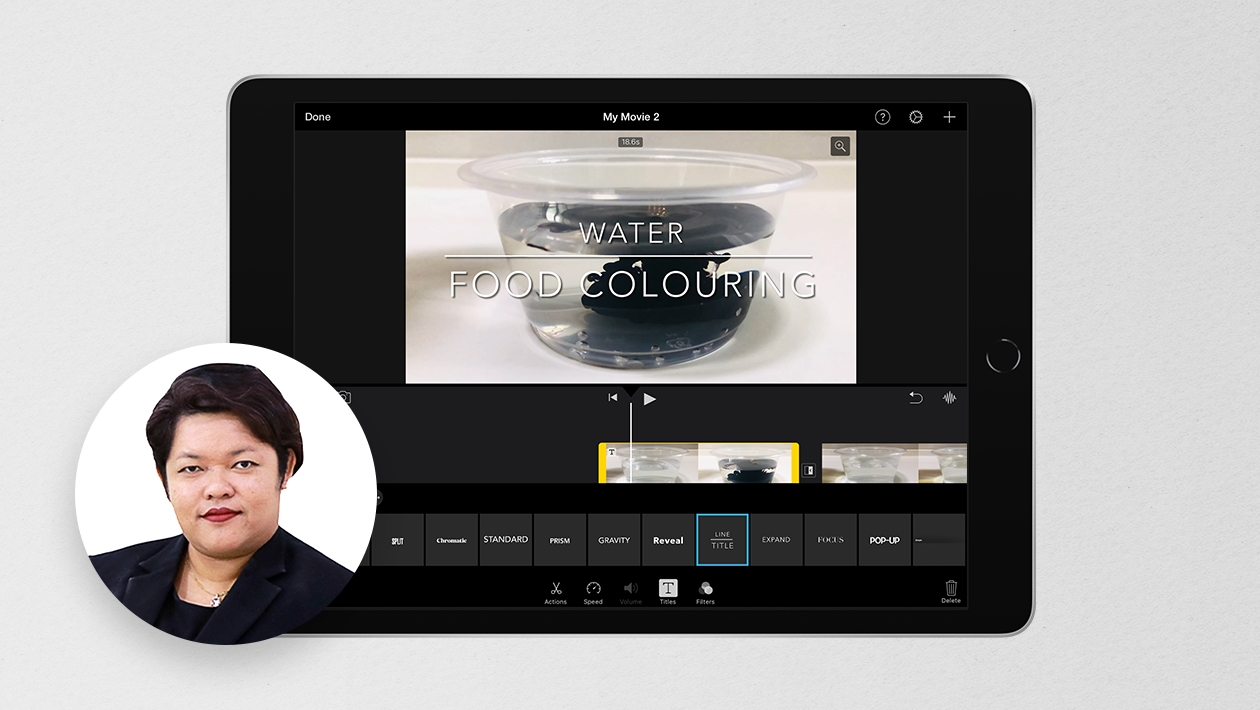

Plastic solution design challenge.

This is used in a 6th grade science classroom. Students learn about how plastic pollution affects organisms in the ocean. They are then challenged to create a way to decrease or eliminate the plastic pollution problem. Students can choose from 5 different projects and then 5 different ways to publicize and advertise their creation or ideas.

Attachments

This action is unavailable while under moderation.

You might also like

In Action: Document Observations in Slow Motion

Championing Sustainability

Loading page content

Page content loaded

250032751020

250013296027

Insert a video

Supported file types: .mov, .mp4, .mpeg. File size: up to 400MB.

Add a still image to display before your video is played. Image dimensions: 1280x720 pixels. File size: up to 5MB.

Make your video more accessible with a closed caption file (.vtt up to 5MB).

Insert an image

Add an image up to 5MB. Supported file types: .gif, .jpg, .png, .bmp, .jpeg, .pjpeg.

Add details about your image to make it more accessible.

Add a caption below your image, up to 220 characters.

This action can’t be undone.

Error message, are you sure you want to continue your changes will not be saved..

Sorry, Something went wrong, please try again

This post contains content from YouTube.

Sign in to continue..

You’ve already liked this post

Attach up to 5 files which will be available for other members to download.

You can upload a maximum of five files.

Choose language

Accept the following legal terms to submit your content.

I acknowledge that I have the rights to post the material contained in this reply.

Review the Apple Education Community Terms of Use and Privacy Policy

Your reply includes attachments that must be reviewed.

This content won’t be publicly available until it clears moderation. Learn more

Not a member yet? Join for free when you sign in.

Sign in to create a post.

Collaboration features of the Forum are currently available in the following countries: Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, United Kingdom, United States. Learn more

Sign in to like this content.

Sign in to post your reply.

Sign in to follow.

Sign in to save this post.

Sign in to view this profile.

This action is unavailable.

Some actions are unavailable in your country or region.

Please complete your registration.

You must complete your registration to perform this action.

This account may not publish.

This account has been restricted from publishing or editing content. If you think this is an error, please contact us.

Some actions are unavailable outside of your Apple Group.

Do you want to stay logged in?

Advertisement

Integrating social policy dimensions into entrepreneurship education: a perspective from India

- Original Paper

- Open access

- Published: 17 September 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Michael Snowden ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1218-7434 1 ,

- Liz Towns-Andrews 2 ,

- Jamie P. Halsall 1 ,

- Roopinder Oberoi 3 &

- Walter Mswaka 4