%20(1).png)

- May 31, 2022

Hidden in Plain Sight: The Secret Epidemic of Illiteracy in the United States

America has a literacy problem, and it’s worse than you think.

Amelia Lake | [email protected]

The ability to read is an essential skill for navigating the modern world, yet millions of adults in the United States have such poor literacy skills that they are unable to read basic sentences, fill out a job application form, or understand the instructions on their prescription labels. Without intervention, illiteracy has wide-reaching and devastating consequences, condemning its sufferers to shame, isolation, and poverty. Kirsten Levinsohn, executive director of New Haven Reads, a New Haven-based organization that works to foster children’s literacy skills, explains current legislative and community efforts to address this issue.

Text messages. Emails. News articles. Road signs. There is a good chance that you have encountered one of these things today, and odds are, decoding them from letters, to words, to meaning took about as much effort as breathing. The ability to read is something the majority of us take for granted, and yet it is one of the most fundamental skills needed to navigate and be successful in our modern world. But for all too many people—maybe some you know—it is an insurmountable barrier and a source of deep shame.

The numbers are staggering. As of 2022, ThinkImpact reports that an estimated 79% of American adults are literate. To put it another way, one out of every five American adults are functionally illiterate, meaning that today in the United States, almost 65 million people are unable to read basic sentences, fill out a job application form, or understand the instructions on their prescription labels. This is not merely a crisis of the illiterate, but also of the underliterate: a whopping 54 percent of all American adults read at or below a sixth grade level.

“Literacy is a basic human right,” says Kirsten Levinsohn , executive director of the New Haven-based nonprofit New Haven Reads. “Reading is fundamental. You can’t be successful by any measure if you don’t first learn to read…It’s easy not to think about it, especially if it doesn’t impact you. But it’s a tragedy for every child who doesn’t learn how to read, and it’s a tragedy for the family, the community, and the state as well.”

The root of the problem is in early childhood. All too often, students who perform poorly in school are allowed to fall through the cracks. Without proper access to services that can help a struggling reader or identify an undiagnosed reading disability early on, children who are most in need of intervention are simply passed over. “If you haven’t been taught how to read before third grade,” says Levinsohn, “it’s unlikely that you ever will, because teachers are moving on. You miss the transition from ‘learning to read’ to ‘reading to learn’.”

The social and economic toll is nothing short of devastating. Starting in school, illiteracy leads to feelings of inadequacy, shame, and isolation. Students with low levels of literacy are more likely to be chronically absent, suffer behavioral problems, and drop out of school, leading to a cascading chain reaction of negative consequences. Literacy Mid-South estimates that high school dropouts , lacking employment prospects, are almost four times more likely to be arrested and 63 percent more likely to be incarcerated than their peers. The burden is lifelong, with morbid outcomes—illiteracy has strong links to poverty , with some 43 percent of illiterate adults living under the poverty line, and a reduced ability to access health services. According to a study by Nursing , elderly individuals who are illiterate are more likely to die within 6 years than those who can read well enough to understand basic health information.

This suffering is not felt evenly across the board. Illiteracy is strongly generational, meaning that individuals who are illiterate are much more likely to have been raised by illiterate and undereducated parents. “Some people say, ‘Oh, the kids can’t read because the parents don’t care,’ ” says Levinsohn. “First of all, the parents do care. They care a lot—they just don’t have the opportunities that higher-earners have access to.” Indeed, family wealth, along with parental literacy level, is among the strongest predictors of a child’s academic success. According to Regis College , exposure to literature—specifically, being read to and having access to age-appropriate books—is a critical part of fostering a child’s reading skills outside the classroom. Yet more than half of all American families living in poverty (who are disproportionately likely to be people of color, rural, Indigenous, or foreign-born) do not have children’s books in the home. Low-income earners, facing additional financial stress and grueling working hours, have less energy and time to engage in their child’s education. As the saying goes, you don’t know what you don’t know, and this is no less true when it comes to education; illiterate adults often lack the knowledge to recognize when their child is falling behind. The end result is that parents who themselves are illiterate, through no fault of their own, are simply ill-equipped to properly support a child’s academic development.

Says Levinsohn, “what’s happening now in Connecticut is that there are huge gaps in reading attainment, often having to do with disparities in income and race, which reflect the inequities in our society. In New Haven right now, about 30 percent of kids are reading at grade level or better—which, if you say it the other way, means 70 percent aren’t, which is horrendous.”

It is worth noting that these statistics are all pre-pandemic. With school closures interrupting the education of millions of students, the situation has only worsened.

The blame lies partly in curriculum design. “This is not to bash teachers,” says Levinsohn, a former teacher herself. “They went into this field for a reason. They’re all working so hard. But not all of them have been trained in the science of reading, and the science of reading is not universally accepted.”

Levinsohn is referring to the so-called “reading wars” , an ongoing debate over how reading should be taught. This rivalry, which dates back to the 1800s, consists of two opposing schools of thought: whole-language and phonics. Proponents of whole-language theory see learning to read and write English as analogous to learning to speak—“a natural, unconscious process” that is best taught through “unstructured immersion”. Words are taught individually, much like Chinese characters, and children are encouraged to decipher their meaning through context clues. Phonics, on the other hand, sees written language more as a code to be deciphered. This method emphasizes phonemic awareness, meaning that it teaches children to identify the constituent sounds of words to sound them out. Despite overwhelming evidence that the phonics approach leads to better reading outcomes, there is no federal requirement for schools to implement it in their curricula.

For the past 20 years, there has been little change in reading outcomes. As Levinsohn puts it: “Obviously, doing the same thing over and over is not working.”

The “ Right to Read ” Act, passed last June by the Connecticut General Assembly under the sponsorship of Senator Patricia Miller, aims to close some of the gaps. With its $12.8 million budget, the bill makes provisions to ensure school districts can hire reading coaches for students who are falling behind. Furthermore, it establishes a Center for Literacy Research and Reading Success, which will oversee the development of reading curricula for students in grades PreK-3. Its focus is, in part, on ensuring that school districts—which previously had complete autonomy in designing their reading curricula—adhere to evidence-based practices of reading instruction. “There is a proven method for literacy instruction,” wrote Miller in an opinion piece for the Stamford Advocate, “and that we need to use it in all of our Connecticut classrooms. Our students are entitled to it.”

Levinsohn is optimistic about the bill’s potential. “It just needs to become a priority,” she says. “There needs to be money and resources at the lowest level so kids are getting the support they need.”

But legislation isn’t the only means of intervention. Community-based organizations like New Haven Reads can and do have a tremendous impact . The nonprofit, initially founded as a book bank, has been a part of the New Haven community for over 20 years and offers a number of programs intended to support literacy development in struggling children. Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, it sponsored school field trips for grades PreK-5 where students got to pick out five books to take home with them. “Unfortunately, a lot of kids don’t have books at home, or maybe they only have one or two,” Levinsohn explains. “We really try to put out books that would be at their grade level and their interest level. We also try very hard with this program and our tutoring program to have books that are diverse and have characters that represent our child readers.” All in all, New Haven Reads donates over 100,000 books a year , and has donated almost 2 million since its founding.

While the pandemic has forced New Haven Reads to temporarily shutter some of its usual activities, “we are still giving out books,” says Levinsohn. “Frankly, a lot to teachers. A lot of them don’t have books in their classrooms, which is quite sad. And even more sad is that a lot of schools have had to close their libraries for financial reasons, so the kids have less access to books.”

In addition to its book bank, New Haven Reads also offers a one-on-one tutoring program, which trains volunteers and matches them with a student with the intention of creating a long-lasting partnership. The program, which serves about 600 children per week, relies on the support of its roughly 400 volunteer tutors, many of them Yale affiliated—students and faculty alike. “For most of the children who come to us, all they need is a little extra individualized help,” Levinsohn says. “A lot of it is confidence for these kids. They feel that they’re stupid if they can’t read, and it’s so far from the truth. To see them grow and become more confident, it’s amazing.”

Despite the squeeze of the pandemic, New Haven Reads only intends to expand its array of services. In the works is an upcoming program intended to serve recent immigrants through a partnership with Integrated Refugee & Immigrant Services . And volunteers are always welcome.

“It’s the community at its best,” says Levinsohn. “It’s people from all walks of life coming together to support our city’s greatest asset—our kids.”

Writer’s reflection:

As a lover of language and a passionate learner, it’s difficult for me to fathom what it must be like to navigate everyday life, never mind education or work, without the ability to read. Yet for millions of Americans—our community members, friends, maybe even our own family—that is their reality. I want to extend my sincerest thanks to Kirsten Levinsohn for sharing her knowledge with me, and encourage readers to consider volunteering or donating to New Haven Reads and other organizations doing important work to tackle this issue.

- 2022 Spring Issue

- United States

Recent Posts

Breathing as a Human Right: Cancer Alley as a Case Study of Environmental Racism

The State of Reproductive Rights in Latin America-Ripples and Rollbacks

Resettlement and the Road Ahead

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Continuing Education

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why publish with this journal?

- About Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology

- About the National Academy of Neuropsychology

- Journals Career Network

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, conceptual issues in the study of illiteracy, the illiterate brain, neuropsychological test performance in illiterates, educational effects in test performance, brain damage and illiteracy, conclusions regarding human cognition through the study of illiteracy, conflict of interest.

- < Previous

Illiteracy: The Neuropsychology of Cognition Without Reading

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Alfredo Ardila, Paulo H. Bertolucci, Lucia W. Braga, Alexander Castro-Caldas, Tedd Judd, Mary H. Kosmidis, Esmeralda Matute, Ricardo Nitrini, Feggy Ostrosky-Solis, Monica Rosselli, Illiteracy: The Neuropsychology of Cognition Without Reading, Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology , Volume 25, Issue 8, December 2010, Pages 689–712, https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acq079

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Illiterates represent a significant proportion of the world's population. Written language not only plays a role in mediating cognition, but also extends our knowledge of the world. Two major reasons for illiteracy can be distinguished, social (e.g., absence of schools), and personal (e.g., learning difficulties). Without written language, our knowledge of the external world is partially limited by immediate sensory information and concrete environmental conditions. Literacy is significantly associated with virtually all neuropsychological measures, even though the correlation between education and neuropsychological test scores depends on the specific test. The impact of literacy is reflected in different spheres of cognitive functioning. Learning to read reinforces and modifies certain fundamental abilities, such as verbal and visual memory, phonological awareness, and visuospatial and visuomotor skills. Functional imaging studies are now demonstrating that literacy and education influence the pathways used by the brain for problem-solving. The existence of partially specific neuronal networks as a probable consequence of the literacy level supports the hypothesis that education impacts not only the individual's day-to-day strategies, but also the brain networks. A review of the issues related to dementia in illiterates is presented, emphasizing that the association between the education level and age-related cognitive changes and education remains controversial. The analysis of the impact of illiteracy on neuropsychological test performance represents a crucial approach to understanding human cognition and its brain organization under normal and abnormal conditions.

Illiterates represent a significant proportion of the world's population. In 2000–2004, close to onefifth of the world's population was illiterate: 13% of men over 15 years of age and 23% of women ( UNESCO, 2005 ). Only a few centuries ago, reading and writing abilities were simply uncommon among the general population. Writing has only a 6,000-year history; for about 95% of our history, Homo sapiens were preliterate. We hypothesize that the acquisition of literacy skills has somehow changed the brain organization of cognition.

When studying illiteracy, the most obvious factor is the generational effect found in most countries (Table 1 ). Elders in most societies generally have a lower-educational level than their children and grandchildren. Moving back in history, the duration of education is progressively shorter on average.

World-wide illiteracy rate during 1970–2015 (projected) ( UNESCO, 2005 )

| Year . | Illiteracy rate (%) . |

|---|---|

| 1970 | 37 |

| 1980 | 30 |

| 1990 | 25 |

| 2000 | 20 |

| 2005 | 18 |

| 2010 | 16 |

| 2015 | 15 |

| Year . | Illiteracy rate (%) . |

|---|---|

| 1970 | 37 |

| 1980 | 30 |

| 1990 | 25 |

| 2000 | 20 |

| 2005 | 18 |

| 2010 | 16 |

| 2015 | 15 |

Reasons for Illiteracy

Two major classes of reasons account for illiteracy: There is a significant diversity in literacy rates among countries, from 99% (e.g., Japan, Canada, and Finland) to below 20% (e.g., Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso; International Adult Literacy Survey, 1998 ). Illiteracy due to personal reasons (learning difficulties, mental retardation, significant motor and/or sensory problems, early central nervous system pathologies, and similar conditions) likely accounts for only a small percentage of illiteracy in industrialized countries and potentially somewhat higher in poor countries with increased prevalence of early central nervous system pathologies.

Social reasons. Illiteracy may be due to the absence of schools, social disapproval of literacy, child labor, and/or poverty.

Personal reasons . For a subgroup of illiterates, learning difficulties, mental retardation, significant motor and/or sensory problems, early central nervous system pathologies, and similar conditions may account for their failure to learn to read despite adequate exposure to education.

These two main classes of reasons for illiteracy present potential confounds for research. Populations that are illiterate for social reasons are likely to differ in important ways other than literacy from the schooled, literate populations that have been the subjects of most research in cognitive psychology (prototypically U.S. college students). In general, illiterates are more likely to be of a lower socioeconomic class, they may have a variety of health problems, they may have less exposure to media of communication, and they may have limited experience with testing and, thus, distrust of researchers, among other differences. Those who are illiterate due to personal reasons are quite likely to have atypically functioning brains and cognitive systems.

One way around this problem is to compare individuals to themselves rather than to other populations. Studies of adults before and after they acquire literacy can help to control for these factors and can furthermore control, to a large extent, for the effects of development. An alternative is the sample used in a series of Portuguese studies (e.g., Reis & Castro-Caldas, 1997 ) comparing sisters, one of whom is literate and the other illiterate due to social demands placed on the eldest daughter to take on the responsibility of child care of younger siblings.

Why Is It Important to Study Illiteracy?

Different fundamental and practical reasons to study illiteracy could be distinguished ( Olson & Torrance, 2009 ). There are, however, at least four important reasons to study the neuropsychology of illiteracy: This article will focus primarily on those aspects of the study of illiteracy most pertinent to the neurocognitive theory, and clinical neuropsychology, as well as the analysis of the effects of education on neuropsychological functioning.

(Neuro)cognitive Theory. The study of illiteracy can contribute to a broader understanding of the organization of cognition.

Clinical Neuropsychology. The analysis of illiteracy can help to discern the influence of both literacy and schooling on cognitive test performance. Educational variables significantly influence performance on a diversity of neuropsychological tests ( Lezak, Howieson, & Loring, 2004 ).

Teaching Literacy. Understanding the basic brain mechanisms, subserving cognition in illiterates may contribute to improving reading and writing teaching methods for illiterate adults (e.g., Ardila, Ostrosky & Mendoza, 2000 ).

Literacy and Neuropsychological Functioning. Exploring the effects of education on literacy and neuropsychological functioning.

A fundamental conceptual presumption of neuropsychology is that the potential for basic cognitive abilities, and correspondingly, their brain mechanisms, are universal and inherent for any human being with normal brain development, regardless of the specific language spoken and one's environmental conditions. Literacy (i.e., extending spoken language to a symbolic visual representation) plays a major role in mediating cognitive processes. Luria (1931 , 1933 , 1966 , 1973 ) and Vygotsky (1934/1978) developed the concept of extracortical “organization of higher mental functions” to account for the interaction of biological and cultural factors in the development of human cognition ( Kotik-Friedgut & Ardila, 2004 ).

Historical Development of Writing and Schools

Several existing writing systems use a mixture of logograms, syllabic graphemes, phonemic graphemes, and extraphonemic markers such as capitalization, punctuation, and spatial layout. The relative emphasis on each level of representation varies from system to system. For example, the Chinese system is predominantly based on logograms with some phonemic graphemes, and extraphonetic markers, and with an alternate phonemic grapheme system available. Likewise, the above sequence is not meant to imply that any one system is more efficient or superior.

Thus, initial writing (or rather, prewriting) was a visuoconstructive ability (i.e., representing external elements visually), and only later did it become an ideomotor praxis ability (i.e., making specific learned and fixed sequences of movements with the hand to create a pictogram—a standardized representation of external elements). Still later, writing became a linguistic ability (i.e., associating the pictogram with a word, and further analyzing the word into its constituent sounds; Ardila, 2004 ). It is not surprising that three major disorders in writing can be observed as a result of brain pathology: Visuoconstructive (spatial or visuospatial agraphia: Impairment in letter, word, and text formation due to disturbed visuospatial skills), ideomotor (apraxic agraphia: Selective disorder of letter formation caused by ideomotor apraxia), and linguistic (aphasic agraphia: Writing impairment due to a language disturbance; Table 2 ). The evolution of writing has continued with the development of different technical instruments for writing: The stylus for etching in clay, feathers, the pencil, the typewriter, and the computer, as well as the development of different writing styles (e.g., handwriting, script, uppercase, lowercase) and different media (e.g., clay, papyrus, paper, computer screens). Moreover, images first and writing later allowed the possibility of representation; thus, they enable humans to think and act beyond their immediate needs ( Suddendorf & Corballis, 1997 ) and promote abstract thinking.

Representational forms of writing and corresponding cognitive skills

| Representational form . | Historical example . | Neurocognitive skill . | Form of agraphia . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drawings pictograms | Cave paintings Egyptian hieroglyphics | Visuoconstructive ability | Visuospatial |

| Logograms | Sumerian | Ideomotor praxis | Apraxic |

| Syllabic graphemes | Japanese Kana | Linguistic ability | Aphasic |

| Phonemic graphemes | Spanish |

| Representational form . | Historical example . | Neurocognitive skill . | Form of agraphia . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drawings pictograms | Cave paintings Egyptian hieroglyphics | Visuoconstructive ability | Visuospatial |

| Logograms | Sumerian | Ideomotor praxis | Apraxic |

| Syllabic graphemes | Japanese Kana | Linguistic ability | Aphasic |

| Phonemic graphemes | Spanish |

Defining Literacy

The definition of literacy is not definitive, nor is there an overt cut-off point; consequently, intermediate stages, such as semiliteracy and functional illiteracy, are often recognized. UNESCO ( http://www.uis.unesco.org/i_pages/indspec/TecSpe_literacy.htm ) defines adult illiteracy as the percentage of the population aged 15 years and over who cannot both read and write a comprehensible short simple statement on their everyday life. Literate does not necessarily mean schooled, even though literacy is usually highly associated with formal schooling. Reading can be transmitted from parents or tutors to children without formal school attendance ( Berry & Bennett, 1992 ; Scribner & Cole, 1981 ). Under normal conditions, reading is not learned by simple exposure, even though illiterates can develop some ability to holistically recognize a few highly frequent words, such as the name of their country, and the name of some popular commercial products ( Goldblum & Matute, 1986 ). Extremely infrequently, the ability to read can be acquired without any deliberate training (so-called “hyperlexia” usually associated with autism, Martos-Perez & Ayuda-Pascual, 2003 ; Nation, 1999 ).

The degree to which contemporary illiterates are confined to access to immediate sensory information probably also reflects the degree to which they are confined in their access to various media of information and communication and, possibly, also to formal education. Da Silva, Petersson, Faísca, Ingvar, and Reis (2004) demonstrated in Portugal that whereas literates and illiterates perform equally well on a fluency task asking for elements known through direct sensory information (“items that can be found in a supermarket”), the two groups differed on a semantic fluency task requiring naming animals. In contrast, literate people can name dinosaurs, camels, or kangaroos, evidently unknown in Portugal, but learned by reading; whereas illiterates can only name cats, dogs, horses, and other animals existing in the immediate surrounding environment and known through direct sensory experience. When the information is related to real life and direct experience, it can be considerably easier to understand. Thus, for the illiterate person, it is easier to repeat a word than to repeat a pseudoword ( Castro-Caldas, Petersson, Reis, Stone-Elander, et al., 1998 ; Kosmidis, Tsapkini, & Folia, 2006 ) and to remember objects presented to them visually than word lists ( Folia & Kosmidis, 2003 ).

The impact of literacy is reflected in all spheres of cognitive functioning. Learning to read reinforces certain fundamental abilities, such as verbal and visual memory, phonological awareness, executive functioning, and visuospatial and visuomotor skills ( Bramão et al., 2007 ; Matute, Leal, Zarabozo, Robles, & Cedillo, 2000 ; Petersson, Reis, Askelof, Castro-Caldas, & Ingvar, 2000 ; Petersson et al., 2001 ). It is not surprising that illiterate people underachieve on cognitive tests that assess these particular abilities. Furthermore, attending school also reinforces certain attitudes and values that may speed the learning process, such as the attitude that memorizing information is important or that knowledge is highly valuable; that learning is a step-by-step process moving from the simple to the more complex. It has been emphasized that schooling improves an individual's ability to explain the basis of performance in cognitive tasks ( Laboratory of Comparative Human Cognition, 1983 ). Whether a fundamental aim of education, or a by-product, the fact remains that all schools and schooling, regardless of their location, have a common influence on those who go through the system, namely, they train students and reinforce certain values. Hence, school may be seen as a culture unto itself, a transnational culture, and the culture of school.

School not only teaches, but also helps in developing certain strategies and attitudes that will be useful for future learning. Ciborowski (1979) observed that schooled and nonschooled children can learn a new rule equally well, but once acquired, schooled children tend to apply it more frequently in subsequent similar cases. School attendance, however, does not mean that educated people simply possess certain abilities that less-educated individuals lack. It does not mean that highly educated people have the same abilities as less-educated individuals, plus something else ( Ardila, Ostrosky & Mendoza, 2000 ). The individual with no formal education most likely has acquired knowledge, skills, and values that educated people have not. Nonetheless, formal cognitive testing evaluates those abilities in which educated people were trained; therefore, it is not surprising that they will outperform those with no formal education. In fact, one study demonstrated that once the effects of education and literacy were separated from each other, some types of language processing were enhanced by any level of literacy, whereas others continued to improve with an increasing level of education ( Kosmidis et al., 2006 ). It is noteworthy that the educational level has a substantial relationship with performance on some cognitive tests, but is not systematically related to everyday problem-solving (functional criterion of intelligence; Cornelious & Caspi, 1987 ). As a matter of fact, when functionally oriented tests, such as the Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test ( Wilson, Cockburn, & Baddeley, 1985 ) and the Fuld Object Memory Evaluation ( Fuld, 1980 ), are administered to people with low education, no significant differences with high-educated people have been observed ( Yassuda et al., 2009 ).

Although schooling represents, in some respects, a transnational culture, that culture is not uniform. Literacy and numeracy are almost universal as the major focus of primary education, but beyond that the qualities of the educational experience vary considerably. Wealthy educational systems are likely to have low student:teacher ratios, abundant teaching materials, extensive communication outside the school (Internet, field trips, visiting instructors), ancillary services (psychologists, therapists, parent services), and instruction in a wide variety of subjects and skills. Schools with less funding often lack these resources. Manly (2006) has demonstrated a relationship between school expenditure and neuropsychological test performance.

School qualities depend on much more than funding. Schools vary greatly in their formal curricula and also in unwritten characteristics. There is much variability in schools’ behavioral expectations and institutional cultures, as well as in their emphasis on bilingualism, visual-spatial skills, abstract reasoning, problem-solving, speeded performance, social skills, individualism, collectivism, moral values, and religious instruction, among other themes. These varying characteristics can reasonably be expected to have an impact on neuropsychological test performance, and this impact is not likely to be entirely linear nor unifactorial, but these relationships have not yet been systematically explored.

Contemporary illiteracy is not the same as historical preliteracy. Literacy facilitates a number of cognitive technologies that may have replaced preliterate cognitive skills. Those preliterate cognitive skills may require intact preliterate societies and may be extinct or vestigial in the contemporary world and in contemporary marginalized illiterates. A functioning illiterate or preliterate society may be required to foster the full flowering of such skills. For example, there are many cultural traditions of bards who memorize long poems and pass them on through generations ( Lord, 1995 ). We tend to think of illiterates as concrete thinkers, yet the fables, proverbs, myths, idioms, and even the metaphors built into the very structure of our languages that have come to us from largely preliterate societies from millennia ago are often quite abstract.

Literacy Versus Schooling

Very important cognitive consequences of learning to read and write have been suggested: Changes in visual perception, logical reasoning (i.e., executive functions), remembering strategies ( Laboratory of Comparative Human Cognition, 1983 ), as well as access to lexical storage and explicit phonological processing ( Kosmidis et al., 2006 ) and improved working memory. Schooling appears to influence formal operational thinking ( Laurendeau-Bendavid, 1977 ) and functional brain organization ( Castro-Caldas, Petersson, Reis, Stone-Elander, et al., 1998 ; Ostrosky-Solis, Ramirez, Lozano, Picasso, & Velez, 2004 ) and to reinforce particular attitudes and values related to learning. Conversely, training these abilities may make it easier to learn to read and write. Interestingly, adults who received training in those abilities in which illiterates significantly underscore (e.g., verbal memory, phonological abstraction, etc.) showed a significant improvement in neuropsychological test scores and a facilitation in their learning-to-read process ( Ostrosky-Solís et al., 2003 ).

Literacy without schooling: The Vai

Scribner and Cole (1981) attempted to separate the effects of literacy from the effects of formal schooling by studying Vai people in Liberia who were literate in the Vai script, but who had not attended school. Vai people have their own script. The script is taught at home, rather than school, allowing the researchers to separate school-based education from literacy. Indeed, there are three educational systems in the Vai culture: (a) Traditional socialization—the bush school, taught by men for boys, and by women for girls; (b) English schooling—much like American schooling, and (c) Quranic schooling—conducted in Arabic. They found that there were no general effects of literacy on a battery of cognitive tests, but performance on some tests was related to particular features of the Vai script and literacy practices. Scribner and Cole proposed that there are definite cognitive skills associated with literacy, but not necessarily with classroom learning. And these cognitive skills are dictated by each culture and situation. Berry and Bennet (1989) carried out a partial replication of this study among the Cree of Northern Ontario.

Comparison of groups with low and high education

Kosmidis, Tsapkini, Folia, Vlahou, and Kiosseoglou (2004 ) and Kosmidis et al. (2006 ) attempted to disentangle the effect of education from literacy in a sample of urban dwellers (illiterates, low-education literates, and high-education literates). They found that education influenced lexical decision-making, concluding that the greater the amount of education, the more effective access to, and, perhaps, the greater the size of the lexical store. In contrast, literacy influenced the capacity of the phonological loop: Low- and high-education literates performed equally well on pseudoword repetition, and better than illiterates. Therefore, they concluded that literacy influences the effectiveness of the direct route from the auditory analysis system to the phoneme level, whereas education influences lexical processing. Similarly, Kosmidis and colleagues (2004) found that semantic processing was affected by the level of education attained, whereas phonological processing depended on whether the individual had attained symbolic representation per se through learning grapheme–phoneme correspondence or had been exposed to formal schooling.

Neither literacy nor school attendance is a simple and linear variable. Reading ability is not only correlated with training time, but also with the idiosyncrasies of the reading system. For example, learning to read is easier in a transparent writing system (regular spelling, e.g., Spanish, German, Greek) than in an opaque writing system (irregular spelling, e.g., English, French; Paulesu et al., 2001 ). Furthermore, school attendance goes far beyond learning to read, write, and calculate. School provides background knowledge in many areas (geography, history, language, etc.), but also contributes to developing learning skills. In school, children are exposed to information that is neither part of their immediate environment nor part of their direct experience. They learn how to establish taxonomies of their newly learned concepts, they learn to use paper and pencil, and they use a language different from that used in their everyday life ( Montiel & Matute 2006 ). School develops and reinforces certain cultural and socialization values by creating alternative parental and authority images; certain forms of group behavior; attitudes toward government, church, or other institutions sponsoring their education; and the process of being tested ( Serpell, 1993 ). Children learn from their teachers, their peers, the group activities at school, and the new context.

Two different approaches can be used to understand the potential differences between the literate and the illiterate brain: Functional and anatomic measures.

Traditional Functional Measures: Dichotic Listening

Several studies have used dichotic listening paradigms to study the potential influence of literacy on cerebral lateralization for language ( Castro & Morais, 1987 ; Damasio, Damasio, Castro-Caldas, & Ferro, 1979 ; Karavatos et al., 1984 ; Kosmidis et al., 2004 ; Tzavaras, Kaprinis, & Gatzoyas, 1981 ) yielding conflicting results. Some investigators reported decreased laterality for language among illiterates relative to literates ( Joanette et al., 1983 ), others no laterality differences ( Damasio, Castro-Caldas, Grosso, & Ferro, 1976 ; Kosmidis et al., 2004 ), and yet others stronger lateralization among illiterates relative to literates ( Tzavaras et al., 1981 ). Potential reasons for the conflicting results may relate to characteristics of the stimuli used in each investigation, such as the nature of the stimuli (i.e., words, pseudowords, numbers, syllables), the phonetic and the acoustic characteristics of the sounds (i.e., stop, nasal, fricative and liquid consonants, or consonants with abrupt onset), and differences in onset and intensity of stimuli in a pair ( Ahonniska et al., 1993 ; Castro & Morais, 1987 ). More recent investigations of the dichotic listening process (among literate individuals) have highlighted the role of attentional resource activity in addition to cerebral dominance for language ( Reinvang et al., 1994 ; van Ettinger-Veenstra et al., 2010 ; Westerhausen & Hugdahl, 2008 ). Unfortunately, none of the studies of dichotic listening in illiteracy took this parameter into account. Therefore, although not informative with regard to the question of hemispheric dominance for language processing in illiterates in general, past studies on dichotic listening among illiterates highlight the need for breaking down language processing into more specific cognitive mechanisms.

Contemporary Functional Measures

Recent studies using different functional measures have demonstrated that literacy and education influence the pathways used by the brain for problem-solving. Schooled literates and illiterates show equivalent left hemisphere attenuation of cortical event-related potentials during a verbal memory task (for instance, memorizing words), but intrahemispheric differences at parietotemporal areas, suggesting that learning literacy produces intrahemispheric specialization ( Ostrosky-Solis et al., 2004 ).

Similarly, several studies using positron emission tomography (PET) and statistical parametric mapping or functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) found additional differences between schooled literates and illiterates in the brain areas activated during language-based tests (i.e., left hemisphere perisylvian area). Interestingly, in one study using repetition of words and repetition of pseudowords, these differences were much more relevant during pseudoword repetition suggesting that the inability to process phonological segmentation was the inability to activate the brain regions responsible for doing it; the only activation in words versus pseudowords that was greater in the literate than in the illiterate group was the more prominent left-sided posterior parietal activation. In particular, when masking with the activation pattern defined by the words–pseudowords contrast in literates, there was increased activation of a left inferior parietal region (BA 40) in literates compared with illiterates in words versus pseudowords. During real-word repetition, the difference was confined to a left parietal region that can be related to the process of writing ( Castro-Caldas, Petersson, Reis, Stone-Elander, et al., 1998 ; Fig. 1 ). This differential activation of neural structures to real versus nonreal words suggested fundamental differences in cognitive processing based on phonological information. A subsequent replication of the aforementioned PET findings ( Petersson et al., 2000 ) traced differences in the neuronal networks used by illiterates versus schooled literates in pseudoword repetition to the interaction between Broca's area and the inferior parietal lobe, as well as the posterior-midinsula bridge between Wernicke's and Broca's areas. Finally, education-related differences were reported in an fMRI study of the effects of education on neural activation in healthy right-handed Chinese subjects ( Li et al., 2006) . These differences in activation patterns emerged in the left inferior/middle frontal gyrus and both sides of the superior temporal gyrus for a silent word recognition task and in the bilateral inferior/middle frontal gyrus and limbic cingulate gyrus for a silent word and picture-naming task. It was suggested that these results indicate that the patterns of neural activation associated with language tasks are strongly influenced by education. Education appears to have enhanced cognitive processing efficiency in language tasks.

Maximum intensity projections of all significant activations thresholded. Results of the interaction analysis (A) word repetition (literate–illiterate) and (B) pseudo-word repetition (literate–illiterate; adapted from Castro-Caldas, Petersson, Reis, Stone-Elander, et al., 1998 ).

Even when their cognitive performance is equivalent, schooled literates and illiterates appear to use different brain activation patterns to perform the same task. Deloche, Souza, Braga, and Dellatolas (1999 ) studied healthy right-handed Brazilians (unschooled illiterates and college graduates) on a task judging the magnitude of numbers within a familiar context (e.g., 10 people in a standard-sized car, 9 students in a school: Is this a lot, average, or too little?). Both groups performed similarly well with regard to the correctness of their judgments. Functional MRI scans, however, demonstrated different brain activation patterns: The college graduates used the left hemisphere exclusively, specifically, the left frontal (BA 47), inferior parietal (BA 40), and temporal lobes (BA 42, 21, and 22). In contrast, the illiterates activated both hemispheres during the task, specifically, the temporal (BA 39, 20, and 22) and the occipital lobes (BA 19 and 37) bilaterally. Activation of the left temporal lobe (BA 21 and 22) was the only finding common to both groups in the number processing task. In post-fMRI interviews inquiring about the strategies that the participants used to perform the judgment task, 95% of the illiterates reported having used visual images, which may explain the activation of the occipital lobe in this group. The college graduates predominantly used abstraction to solve the problems, which corresponds to their left hemisphere activation.

Carreiras and colleagues (2009) compared structural brain scans from those who learned to read as adults (late literates) with matched illiterates. It was observed that late literates had more white matter in the splenium of the corpus callosum and more grey matter in bilateral angular, dorsal occipital, middle temporal, and left supramarginal and superior temporal gyri. It was also disclosed that the anatomical connections linking the left and right angular and dorsal occipital gyri through the area of the corpus callosum white matter was larger in late literates than in illiterates. Results were interpreted to suggest that reading increased the interhemispheric functional connectivity between the left and right angular gyri.

In sum, the data produced by functional imaging studies on brain activation during cognitive tasks support the contention that learning literacy impacts not only the individual's day-to-day strategies, but also influences the functional architecture of the adult human brain.

Anatomical Interhemispheric Comparisons

Comparing schooled literates and illiterates, Castro-Caldas and colleagues (1999) observed a slightly thinner corpus callosum in illiterates, specifically the region where parietal fibers are thought to cross. The morphology of the corpus callosum appears sensitive to the quality of the information content of the brain. The corpus callosum is larger for instance, in musicians presumably because their performance with musical instruments requires the involvement of both hemispheres ( Norton et al., 2005 ). In the aforementioned PET scan study ( Castro-Caldas, Petersson, Reis, Stone-Elander, et al., 1998 ), differences between groups indicated a dissociation between the superior and the inferior parts of the angular-supramarginal regions, that is, the superior parts being more active on the left than on the right in illiterates compared with literates, whereas the reverse was the case for the inferior parts and the precuneus. This suggests differential recruitment of right and left regions of the parietal lobe related to literacy and is in accordance with the finding reported above for magnitude judgments.

Some authors have postulated that hemispheric specialization is dependent on the nature of the task rather than the nature of the stimulus; for instance, Stephan and colleagues (2003) used fMRI in a group of normal subjects during letter and visuospatial decision tasks with identical word stimuli to address two unresolved problems. It was noted that hemispheric specialization depended on the nature of the task rather than on the nature of the stimulus. Furthermore, the increased coupling between left anterior cingulate cortex and left inferior frontal gyrus during letter decisions was observed, whereas right anterior cingulate cortex showed enhanced coupling with right parietal areas during visuospatial decisions; these authors suggested that cognitive control is thus localized in the same hemisphere as task execution. We would propose an additional point based on the aforementioned findings: Hemispheric specialization may also be related to the strategy used to solve the problem (verbal, spatial, etc.), which is dependent on the individual's skills acquired by learning.

General Cognitive Functioning

Mini-mental state exam.

The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a brief exam widely used by physicians primarily to screen for the level of delirium or dementia. It consists of items of orientation, memory, attention, drawing, reading, writing, repetition, naming, and following directions, scored on a 30-point scale ( Folstein, Folstein, & Mchugh, 1975 ). The total MMSE scores for illiterate samples average around 15–20 points (Table 3 ), in the range of severe cognitive alterations according to the 23 of 24 point cut-off suggested by Folstein and colleagues (1975) .

Given its widespread use as a screening instrument for cognitive dysfunction, potential effects of literacy on performance may be biased against those who are illiterate (Table 3 ). In fact, Bertolucci, Brucki, Campacci, and Juliano (1994) found that illiterates differed from schooled literates on the MMSE not only on items related to writing and arithmetic (calculation, reading a command, writing a sentence, and copying a line drawing), but also on orientation to time. Other studies have found even more extensive differences; in one study, 16 of 19 questions differentiated schooled literates from illiterates at a level of significance of P < .001, where only repetition, recall, and naming were unrelated to literacy ( Rosselli et al., 2000 ), with differences in performance being observed even between illiterates and people with as little as 1 year of education at a level of significance of P < .0001 ( Brucki, Nitrini, Caramelli, Bertolucci, & Okamoto, 2003 ).

Scores for illiterates on the MMSE in different normative studies

| Author . | Age . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ostrosky and colleagues (2000) | 16–50 | 19.7 | 3.7 |

| 51–65 | 16.7 | 4.4 | |

| 66–89 | 16.4 | 4.2 | |

| ) | 65–92 | 18.8 | 2.9 |

| Laks and colleagues (2003) | 65–84 | 17.2 | 4.4 |

| >84 | 14.3 | 3.9 |

| Author . | Age . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ostrosky and colleagues (2000) | 16–50 | 19.7 | 3.7 |

| 51–65 | 16.7 | 4.4 | |

| 66–89 | 16.4 | 4.2 | |

| ) | 65–92 | 18.8 | 2.9 |

| Laks and colleagues (2003) | 65–84 | 17.2 | 4.4 |

| >84 | 14.3 | 3.9 |

Note: MMSE = Mini Mental State Exam.

Motor Functions

Writing is a fine movement activity; therefore, illiterate people may be less proficient with complex motor tests when compared with people able to write. In fact, several studies have supported this hypothesis. Rosselli, Ardila, and Rosas (1990) found statistically significant differences between illiterates and university-educated individuals in clinical tests of apraxia (buccofacial and ideomotor praxis, finger alternating movements, meaningless movements, coordinated movements with both hands, and motor impersistence tasks). When mimicking movements, illiterates frequently used the hand as instrument (body-part-as-object). Illiterates also tended to replace the movement for the corresponding verbalization. Nitrini, Caramelli, Herrera, Charchat-Fichman, and Porto (2005) administered Luria's fist-edge-palm test to 745 individuals with different educational levels, including 238 illiterates. Logistic regression showed that illiteracy was associated with failure, whereas gender and age were not. The proportion of individuals failing was inversely related to years of schooling. For those able to reproduce the sequence, the number of demonstrations for successful reproduction was also inversely related to years of schooling. Finally, Ostrosky, Ardila, and Rosselli (1999) investigated performance on four motor tests—changing left–hand position, changing right–hand position, alternating movements with both hands, and Luria's opposite reactions test—across different educational levels. On all four motor tests, performance was higher in the participants with a higher educational level. The effect of level of education was robust on the first three tests, but minimal on the fourth.

Bramäo and colleagues (2007) corroborated the association between reading skills and performance on visuomotor tasks. They instructed illiterate and literate (Portuguese) participants to use the right or the left index finger to touch a randomly presented target on the right or left side of a touch screen. The literate subjects were significantly faster in detecting and touching targets on the left compared with the right side of the screen. Presentation side did not affect performance of the illiterate group.

In conclusion, illiterates demonstrate poorer performance in a diversity of motor tests, including reproducing movements and sequences of movements, alternating movements with both hands, and imitating meaningless movements.

Calculation and Number Processing

The assessment of calculation and number processing in illiterates and semiliterates after a brain injury is often a complex task because these processes are closely linked to education. On the other hand, calculation is present in myriad daily life situations, such as in the use of money, means of transportation (bus routes, subways, trains), telephone numbers, and mental calculations.

An international group of neuropsychologists created a battery of tests (EC 301) for evaluating calculation and number processing in literate brain-damaged adults ( Deloche et al., 1994 ). This instrument was adapted into several languages (English, Finnish, French, German, Greek, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish), thus providing a common tool for structurally equivalent evaluations of examinees’ abilities. Nevertheless, the use of this tool in illiterates and semiliterates was shown to be ineffective. A standardized, validated version of the original EC 301 Battery in Portuguese was developed in Brazil. Ten simple tasks assessing counting, number processing, elementary calculation, and quantity estimation were presented to 122 normal Brazilian adults, aged between 18 and 58 years with 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 years of education ( Deloche et al., 1999 ). Tasks such as counting the number of elements in small sets were almost perfectly mastered by these illiterates and semiliterates; however, a sizeable proportion of the sample made errors on other tasks (e.g., those assessing knowledge of the correspondence between numbers and banknotes).

Language abilities have been strongly correlated with a socioeducational level. Low socioeconomic parents use more nonverbal than verbal strategies with children ( Robinson, 1974 ). Along the same lines, the language used by people with a low socioeconomic level is less fluent and has a simpler grammatical structure; it relies much more on emotional than on logical strategies ( Bernstein, 1974 ). Similarly, rural, unschooled children may lack symbolic representation skills because their linguistic ability is tied to the immediate context of the referent ( Bruner, Oliver, & Greenfield, 1966 ). Thus, it appears that formal education facilitates the development of language into a fully symbolic tool. At least one study ( Lantz, 1979 ), however, showed that rural unschooled children performed better than schooled Indian or American children in coding and decoding culturally relevant objects, such as grain, and seeds. Thus, children without formal schooling were able to separate language symbols from the physical referent and to use those symbols for communicating accurately, but display of this ability depended on the cultural relevance of the stimuli used ( Laboratory of Comparative Human Cognition, 1983 ). In fact, the significance of schooling lies not just in the acquisition of new knowledge, but in the creation of new motives and formal modes of discursive verbal and logical thinking divorced from immediate practical experience ( Luria, 1976 ).

Verbal fluency tests have been administered to illiterate populations in several countries. Table 4 presents the results of the available normative studies for the category “animals.” Most frequently, the number of animals found in 1 min is about 10–12. With increasing education, the number of items progressively increases.

Animal fluency in illiterates

| Author . | Place . | . | Mean age . | . | Animals . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aruaco Indians (Colombia) | 5 | 26.2 | 2.9 | 9.8 | 1.5 | |

| Brazil | — | — | — | 11.9 | — | |

| Brazil | — | — | — | 12.1 | — | |

| Greece | 19 | 72.0 | 7.6 | 11.8 | 3.2 | |

| USA | 43 | 74.8 | 5.7 | 11.5 | 3.1 | |

| Mexico | 10 | 38.2 | 10.7 | 13.5 | 3.0 | |

| Mexico | 25 | 46 | — | 10.4 | — | |

| Mexico | 50 | 21.3 | 3.3 | 13.2 | 3.7 | |

| Mexico | 50 | 39.6 | 6.7 | 13.7 | 4.5 | |

| Mexico | 49 | 58.8 | 4.1 | 12.7 | 5.0 | |

| Mexico | 50 | 71.2 | 4.0 | 13.1 | 7.1 | |

| Ostrosky and colleagues (2004) | Maya Indians (Mexico) | 7 | 58.4 | 8.8 | 11.0 | 2.5 |

| Ostrosky, Ramirez, and Ardila (2004) | Pame Indians | 7 | 53.6 | 6.1 | 11.8 | 4.0 |

| ) | Portugal | 23 F | 62.0 | 7.1 | 10.8 | 3.7 |

| Colombia | 100 | 16–65 | — | 10.6 | 3.4 |

| Author . | Place . | . | Mean age . | . | Animals . | . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aruaco Indians (Colombia) | 5 | 26.2 | 2.9 | 9.8 | 1.5 | |

| Brazil | — | — | — | 11.9 | — | |

| Brazil | — | — | — | 12.1 | — | |

| Greece | 19 | 72.0 | 7.6 | 11.8 | 3.2 | |

| USA | 43 | 74.8 | 5.7 | 11.5 | 3.1 | |

| Mexico | 10 | 38.2 | 10.7 | 13.5 | 3.0 | |

| Mexico | 25 | 46 | — | 10.4 | — | |

| Mexico | 50 | 21.3 | 3.3 | 13.2 | 3.7 | |

| Mexico | 50 | 39.6 | 6.7 | 13.7 | 4.5 | |

| Mexico | 49 | 58.8 | 4.1 | 12.7 | 5.0 | |

| Mexico | 50 | 71.2 | 4.0 | 13.1 | 7.1 | |

| Ostrosky and colleagues (2004) | Maya Indians (Mexico) | 7 | 58.4 | 8.8 | 11.0 | 2.5 |

| Ostrosky, Ramirez, and Ardila (2004) | Pame Indians | 7 | 53.6 | 6.1 | 11.8 | 4.0 |

| ) | Portugal | 23 F | 62.0 | 7.1 | 10.8 | 3.7 |

| Colombia | 100 | 16–65 | — | 10.6 | 3.4 |

Performance on phonemic or letter fluency tests is extremely difficult for illiterates. Available data suggest that letter fluency in illiterates may be about 3–4 words in 1 min, at least for Spanish and Greek, although this could vary by language (e.g., Kosmidis et al., 2004 ; Montiel & Matute, 2006 ; Ostrosky et al., 1999 , 2004).

Language repetition ability in illiterates is equivalent to that of schooled literates if real, high-frequency words are presented. However, when using pseudowords, difficulties are observed ( Kosmidis et al., 2004 ; Petersson et al., 2000 ; Reis & Castro-Caldas, 1997 ). Similarly, illiterates repeat high-frequency, but not low-frequency, words normally ( Rosselli et al., 1990 ). Of course, low-frequency words may be equivalent to pseudowords for a person with a limited vocabulary. Reis and Castro-Caldas (1997) proposed that illiterate individuals (a) have difficulties in repeating pseudowords, (b) are worse at memorizing pairs of phonologically related words compared with pairs of semantically related words, and (c) have difficulties in generating words according to a formal criterion. Illiterate persons use strategies that are good for semantic processing, but inadequate for explicit phonological analysis, while literate individuals are able to use several parallel running strategies.

It can be conjectured that vocabulary size is significantly correlated with educational level, considering that current educational systems are especially directed toward reinforcing verbal abilities and verbal knowledge. Reis, Guerreiro, and Castro-Caldas (1994 ) and Reis, Petersson, Castro-Caldas, and Ingvar (2001) compared schooled literates and illiterates on the task of naming real objects, naming photographs of these objects, and naming drawings of them. Results showed that although both groups performed similarly at naming real objects, illiterates performed more poorly on naming photographs and even more poorly on naming drawings. The authors suggested that introducing color information was useful in improving the performance of illiterates in naming drawings ( Reis et al., 2001 ). Therefore, increasing the amount of information contributed to better access to the name.

Metalinguistic Awareness

It has been observed that illiterate versus literate people do not differ in categorical perception of phonemes, but illiterate people display a less precise categorical boundary and a stronger lexical bias ( Serniclaes et al., 2005 ; Ventura, Kolinsky, Querido, Fernandes, & Morais, 2007 ). Literacy, however, has been related to metalinguistic awareness (which can be regarded as an executive function), since it is by means of the latter that it is possible to turn aspects of language into objects of reflection. Specifically, studies associated with phonological awareness suggest that learning to read leads children to dissect language into small, nonmeaningful units. Illiterate adults find it difficult to consider words and nonwords as sequences of phonemes ( Morais, Cary, Alegria, & Bertelson, 1979 ) and, as a consequence, they underperform on tasks that require thinking about the words’ phonemic characteristics (e.g., phonemic fluency tasks; Kosmidis et al., 2004 ; Reis & Castro Caldas, 1997 ).

However, illiterate performance is better, although still inferior to that of schooled literates, when the critical unit is the syllable rather than a phoneme, as well as on rhyme detection ( Morais, Bertelson, Cary, & Alegria, 1987 ). When comparing illiterate to literate nonschooled groups on explicit phonological awareness tasks, Montiel and Matute (2006) found equivalent performance between groups when dealing with syllables, but differences on the onset detection task and on the initial phoneme detection test. Nonetheless, both groups diverge from the schooled literate group on more complex phonemic awareness tasks, such as phonemic segmentation, phoneme blending, and initial phoneme deletion. Illiterate children had difficulty in identifying the number of words in an oral sentence, suggesting that illiterate children find it difficult to think about language as a string of words.

The aforementioned findings suggest that the influence of literacy extends beyond mere explicit phonemic awareness to affect metalinguistic awareness, as well.

Visuoperceptual and Spatial Abilities

One visual-spatial effect of reading is the training of a specific direction of visual scanning (left to right, for most European-origin writing systems). Using nonlinguistic stimuli, Ostrosky-Solís, Efron, and Yund (1991) studied the scanning mechanism through a computer target detection paradigm in 60 illiterate and 60 literate individuals matched on a socioeconomic level. Although target detection accuracy was identical in the two groups, there were significant differences between the dectectability gradients of the literate and illiterate groups, suggesting that learning to read trains the scanning mechanisms toward more consistent scan paths. Padakannaya and colleagues (2002) administered a picture array naming and recall task to three groups of child readers—unidirectional right-to-left readers of Arabic, unidirectional left-to-right readers of Kannada, and bidirectional readers of Urdu and English—and one group of Urdu illiterate adults. The results showed a right-to-left direction of visual scanning in the Arabic and Urdu readers. In the latter group, the strength of the scanning effect decreased with more schooling in English. No right-to-left effect was observed in Kannada readers or Urdu illiterates. These results suggest that the reading direction can affect scan habits in nonlinguistic tasks. The same effect has been documented in drawing.

Vaid, Singh, Sakhuja, and Gupta (2002) analyzed the influence of reading/writing direction and handedness on the direction of stroke movement in free-hand figure drawing. Adult readers of scripts with opposing directionality (Hindi vs. Urdu) and illiterate controls were observed while drawing a tree, a hand, a house, an arrow, a pencil, and a fish. Right-handers (including right-handed illiterates) and left-to-right readers drew most figures from left to right, whereas left-handers (including left handed illiterates) and right-to-left readers more often drew the figures from right to left.

Various neuropsychological studies have shown significant differences between schooled literates and illiterates in performing spatial and visuoperceptual tests. Ardila, Rosselli, and Rosas (1989 ) administered a basic neuropsychological test battery to two extreme educational groups: Illiterate and professional adults, matched by sex and age. All of the visuospatial tasks (copying a cube, a house, and the Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure; telling the time on a clock; recognizing superimposed figures; recognizing the national map; and drawing the plan of the room) differentiated the two extreme educational groups. Matute and colleagues (2000) used four stick construction tasks (a test with a higher ecological validity for illiterates than copying figures) in illiterate, semiliterate, and literate participants. Although illiterates generally made more errors than semiliterates and semiliterates more than schooled literates, only some of these differences were statistically significant. Significant differences were found for lack of global fidelity and disarticulation errors when all four figures were considered together. Dansilio and Charamelo (2005) used both figure copying and constructional abilities in 15 illiterates and a matched group with about 6–7 years of school. The most frequent and relevant findings in illiterates in figure copying were an inability to reproduce the perspective (13 of 15), unfolding (4 of 15), and unstructured copying (3 of 15). No errors were observed on the stick construction task.

Gonçalves (2004) emphasized the difficulty illiterates had in copying drawings. As can be seen in Fig. 2 (reproduced from Castro-Caldas, 2004 ), an illiterate copied one of the Bender drawings following a sequence that did not respect the idea of two separate but connected elements, which is the way literate individuals tend to read the drawing. This resembles the concept of integrative agnosia proposed by Riddoch and Humphreys (1987) . Visually guided hand motor behavior may also be biased by literacy. In a test paradigm in which literate and illiterate individuals were asked to direct the cursor toward a target on the screen of a computer using the mouse, illiterate individuals were slower then literate controls, in particular when the right hand had to move the cursor to the left side of the screen. This crossed condition is apparently trained by writing ( Reis & Castro-Caldas, 1997 ).

Sequence of copying (right) of a Bender drawing (left).

Culture and literacy can affect strategies used to recall information. Barltlett (1932) proposed that illiterates more frequently use rote learning whereas literate people use more active information integration procedures (“metamemory”). Cole and Scribner (1974) observed that when memorizing information, schooled literates and illiterates make use of their own groupings to structure their recall; for instance, high-school students rely mainly on taxonomic categories, whereas illiterate bush farmers make little use of this principle. The authors argue that cultural differences in memorizing do not consist in the presence or the absence of mnemonic techniques in general, but in the utilization of a specific technique: Reorganization of the to-be-remembered material. This particular strategy for recall could be tied to school learning experiences.

Illiterates generally perform more poorly than schooled literates on conventional neuropsychological memory measures such as wordlist learning and recall ( Ardila et al., 1989 ; Cole, Frankel, & Sharp, 1971 ; Cole, Gay, Glick, & Sharp, 1971 ; Folia & Kosmidis, 2003 ; Montiel & Matute, 2006 ; Nitrini et al., 2004 ), story learning and recall ( Montiel & Matute, 2006 ), verbal paired associates ( Montiel & Matute, 2006 ; Reis & Castro-Caldas, 1997 ), digits backwards ( Montiel & Matute, 2006 ), number-months (an adaptation of the Wechsler Memory Scale III Letter-Number Sequencing task), and complex figure drawing ( Ardila et al., 1989 ). However, the performance of illiterates seems to approach that of literates on object memory ( Folia & Kosmidis, 2003 ; Nitrini, Caramelli, Herrera, Porto, et al., 2004 ) and wordlist recognition memory ( Ardila et al., 1989 ). Illiterates’ low performance in memory tests may be specific to some of the psychometric procedures generally used in testing memory.

The discrepancy observed between poor free recall and good recognition of illiterate individuals on object learning tasks suggests inefficient encoding and retrieval strategies or poor organization of the material to be learned ( Eslinger & Grattan, 1993 ). Recall of learned information generally occurs without cues or external support, requiring considerable self-initiated activity and executive skills in addition to memory abilities ( see Parkin & Leng, 1993 ). Among illiterates, these skills may be adequate for a relatively passive cognitive process such as efficient recognition of stimuli learned through repetition, yet inadequate to support a relatively active and effortful cognitive process such as free recall. This contention is supported by the findings of an improvement in cognitive functions, including verbal memory, not specifically targeted in an adult learning-to-read program; presumably, learning to read enhanced metacognitive abilities such as using analytic strategies, planning, and organizing output sequences, in this sample ( Ardila, Ostrosky & Mendoza, 2000 ). Whether this improvement is a direct result of literacy acquisition or of schooling is not clear.

A PET scan study found no group differences between schooled literates and illiterates on encoding and retrieving paired associate words ( Petersson et al., 2000 ). Both groups showed a positive correlation between cued-recall success and the activation of the left inferior prefrontal cortex and the medial temporal lobes during encoding, suggesting that literacy and schooling do not alter the basic neuroanatomy of encoding verbal material.

Test-Wiseness

Test-wiseness refers to the examinee's knowledge of how tests are designed, the expectations behind tests, and strategies for taking tests, independent of the content the tests are designed to measure Thorndike (1951) . It is seen as a nuisance variable that gives its possessors better scores on tests which may not necessarily reflect better abilities on the capacity being measured. Much of the literature on test-wiseness has investigated students well-entrenched in an educational career and examined relatively sophisticated test strategies in group administered tests, suggesting that effects are modest ( Green & Stewart, 1984 ). However, what few studies are available for very young children and for those from developing countries suggest that the effect is more substantial for these populations. Therefore, an important part of the differences between illiterates and literates on cognitive tests may have to do not so much with cognitive abilities per se , as with test-taking abilities and familiarity. Test taking and, consequently, test-wiseness are most likely skills learned primarily in school ( Nell, 2000 ).

The Effect of Increasing Schooling Time

Even 1 or 2 years of school can make a significant difference in performance on some neuropsychological tests. Ostrosky, Ardila, Rosselli, López-Arango, and Uriel-Mendoza (1998) examined 64 illiterates, 64 adults with 1–2 years of school, and 64 adults with 3–4 years of school with the NEUROPSI. Statistically significant differences were found between the illiterates versus 1–2 years of school—favoring the latter—on the Language Comprehension, Phonological Verbal Fluency, and Similarities subtests. Significant differences were observed between illiterates versus 3–4 years of school—favoring the latter—in the following subtests: Visual Detection, 20–3, Copy of a Semicomplex Figure, Calculation Abilities, Sequences, Alternating movements, Recall of words: Cueing, and Recall of a Semicomplex Figure (Table 5 ).

Mean ( SD ) performance and comparisons of groups by the level of education on NEUROPSI neuropsychological tests (adapted from Ostrosky et al., 1998 )

| Tests . | Score range . | Years of schooling | Significant differences . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 0 . | 1–2 . | 3–4 . | . |

| Visual detection | 0–16 | 9.9 (4.5) | 11.2 (4.1) | 12.5 (3.2) | G3 versus G1 |

| 20 minus 3 | 0–5 | 3.1 (1.9) | 3.1 (1.7) | 4.1 (1.2) | G3 versus G1,G2 |

| Semicomplex figure (copy) | 0–12 | 7.5 (2.0) | 8.8 (2.4) | 9.4 (1.9) | G3 versus G1,G2 |

| Language: Comprehension | 0–6 | 3.7 (1.2) | 4.4 (0.8) | 4.6 (1.0) | G1 versus G2,G3 |

| Phonological fluency | 0–15 | 3.1 (3.7) | 6.5 (4.0) | 7.0 (4.1) | G1 versus G2,G3 |

| Similarities | 0–6 | 2.1 (2.2) | 3.5 (2.1) | 3.9 (1.9) | G1 versus G2,G3 |

| Calculation abilities | 0–3 | 0.9 (1.0) | 1.5 (1.1) | 1.6 (1.1) | G3 versus G1,G2 |

| Sequences | 0–1 | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.4 (0.5) | G3 versus G1,G2 |

| Alternating movements | 0–2 | 0.8 (0.7) | 1.1 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.7) | G3 versus G1 |

| Recall: Words Cueing | 0–6 | 4.1 (1.4) | 4.3 (1.4) | 4.7 (1.4) | G3 versus G1 |

| Semicomplex figure | 0–12 | 6.3 (2.2) | 7.0 (2.4) | 8.4 (2.3) | G3 versus G1,G2 |

| Tests . | Score range . | Years of schooling | Significant differences . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | . | 0 . | 1–2 . | 3–4 . | . |

| Visual detection | 0–16 | 9.9 (4.5) | 11.2 (4.1) | 12.5 (3.2) | G3 versus G1 |

| 20 minus 3 | 0–5 | 3.1 (1.9) | 3.1 (1.7) | 4.1 (1.2) | G3 versus G1,G2 |

| Semicomplex figure (copy) | 0–12 | 7.5 (2.0) | 8.8 (2.4) | 9.4 (1.9) | G3 versus G1,G2 |

| Language: Comprehension | 0–6 | 3.7 (1.2) | 4.4 (0.8) | 4.6 (1.0) | G1 versus G2,G3 |

| Phonological fluency | 0–15 | 3.1 (3.7) | 6.5 (4.0) | 7.0 (4.1) | G1 versus G2,G3 |

| Similarities | 0–6 | 2.1 (2.2) | 3.5 (2.1) | 3.9 (1.9) | G1 versus G2,G3 |

| Calculation abilities | 0–3 | 0.9 (1.0) | 1.5 (1.1) | 1.6 (1.1) | G3 versus G1,G2 |

| Sequences | 0–1 | 0.1 (0.3) | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.4 (0.5) | G3 versus G1,G2 |

| Alternating movements | 0–2 | 0.8 (0.7) | 1.1 (0.7) | 1.3 (0.7) | G3 versus G1 |

| Recall: Words Cueing | 0–6 | 4.1 (1.4) | 4.3 (1.4) | 4.7 (1.4) | G3 versus G1 |

| Semicomplex figure | 0–12 | 6.3 (2.2) | 7.0 (2.4) | 8.4 (2.3) | G3 versus G1,G2 |

Notes: G1 = illiterates; G2 = 1–2 years of school; G3 = 3–4 years of school.

Nonetheless, when comparing the scores in the same NEUROPSI test battery of participants with 10–12, 13–17, and 18–24 years of school, only a few significant differences were found. These observations indicate that the educational effect on neuropsychological test performance is “not” linear. Differences between zero and 3 years of education are usually highly significant; differences between 3 and 6 years of education can be lower; between 6 and 9 are even lower; and so forth, with virtually no differences between, for example, 12 and 15 years of education . This means that on neuropsychological tests, education effects represent a negatively accelerated curve, tending to plateau. This is not surprising, considering that, in general, neuropsychological tests have a low ceiling. Another consequence of this finding is that neuropsychological tests that show no education effect between, for example, North Americans with fewer and greater than 12 years of education (but with no fewer than 8 years of education) cannot be safely extrapolated to assume no educational effect for fewer than 8 or as low as 0 years of education.

The length, qualities, and content of the school day and year vary considerably from country to country and even from school to school. More refined measures of length and qualities of schooling are needed in future studies.

Studies in Illiterate Children

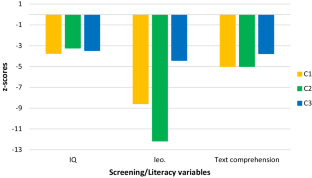

In almost all occidental cultures, formal reading acquisition starts as soon as aged 5–6. Thus, the process to become literate starts early in childhood; however, little attention has been paid to illiterate condition in children. A pioneer study in illiterate children was performed in Mexico, with the aim to investigate whether or not the effects of literacy on neuropsychological test performance are already evident during childhood, as has been reported previously for illiterate adult populations. Seeking that purpose, the performance of 21 illiterate children and 22 literate children aged 6–13 was compared on 13 cognitive domains of the “Evaluación Neuropsicológica Infantil” (ENI; “Child Neuropsychological Assessment”): Attention, constructional abilities, verbal memory coding and delayed recall, visual memory coding and delayed recall, tactile perception, visual perception, auditory perception, oral language, metalinguistic awareness, calculation, and spatial abilities. Demographic variables were controlled to avoid effect of socioeconomic characteristics. For the illiterate group, school nonattendance was due to social-family reasons, thus controlling learning disabilities effects. Results showed that the illiterate group significantly underperformed the literate group in mostly all measures except tactile perception. Moreover, age was a significant covariant, where higher scores were related to older ages in both groups. However, when analyzing the cognitive domains that it is known that are related to schooling (metalinguistic awareness and calculation), it was found that metalinguistic awareness task performance improve with age in literate children but it was not the case for the illiterate group; at the same time for the calculation abilities, an effect of age was evident in both groups suggesting that math learning is school and environment-dependent ( Matute et al., Submitted ).

Executive Function was also investigated in these two groups (Matute et al., unpublished) four domains were analyzed: Verbal fluency, mental flexibility, planning and concept formation, and reasoning where 8 measures were compared: Verbal fluency, semantic verbal fluency, phonemic verbal fluency, categories achieved in the card sorting test (mental flexibility test), number of correct designs done with the minimum number of movements in the Pyramid of Mexico Test (a planning and organization test), similarities, and matrices and arithmetic problems. With the exception of the matrices test, the illiterate children scored significantly below the literate children suggesting that differences in the development of executive functions between these two populations are already evident in childhood. The absence of difference in matrices test is related to low score in both groups; thus, it could be possible that those skills underlying this type of test are acquired at a later stage, and intergroup differences would not be evident in childhood.

Learning to Read in Children Versus Learning to Read in Adults