- Peoplefinder

- Graduate Education

How to Read Like a Graduate Student

by Katrina Dunlap

If you are in graduate school — whether part-time or full-time — chances are you are inundated with multiple reading assignments. From reading dissertations to textbooks, these assignments can be time-wasted without a having a strategic approach to pull something useful out of it. While there are lots of acronym-driven reading techniques, like “SQ3R” or “Survey-Question-Read-Recite-Review,” which aim to help you build a framework to understand your reading assignment, I personally believe that these techniques take too much time to understand and are cumbersome. Below, I’ve outlined some helpful tips for you to consider with respect to your graduate-level reading assignments.

Skim it! The longer the readings are, the more likely the paragraphs in those readings are going to be “filler” which include background and tangential details. Often you don’t really need to read these paragraphs in depth to get the information you need for your classes. So by skimming each paragraph very quickly, you then get a feel for the reading and figure out which paragraphs hold the most pertinent information.

Read backwards. Knowing how the story will end will help your comprehension of what you are reading. If you want to figure out what a certain chapter is all about, you can first go to the back of the text and review the summary, vocabulary lists, chapter questions. Additionally, look for a “review” section if it is a standard textbook to get a feel for what the actual chapter wants you to learn. When you go through the chapter, you’ll be able to identify the vocabulary or a graphic that was referenced in the review section.

Think of questions. By coming up with questions while you read, you deepen your comprehension and understanding. When you are going through the chapter, if you are skimming and something comes up that you don’t really know about, then write it down as a question. Additionally, use headings and sub-headings in the chapter as potential questions. So if there’s a sub-heading that talks about a specific concept, re-word the sub-heading as a question, write it down, and when you go through the actual content of that section, answer the question for yourself.

Pay attention to text format. Take a glance at bold and italicized text because these are almost certainly going to appear on the exam or discussed during class. Pay attention to things that stand out, and write those down.

Highlight or take notes. Never read anything without a highlighter and pencil nearby. Note taking while reading is critical to comprehension and recollection. Using flags are helpful in marking up texts in a non-damaging way. Recording your notes in a central hub such as Evernote , Zotero , or Microsoft’s OneNote software, allows you to reinforce what you’ve read and catalog your notes for future use.

In conclusion, no matter which method or technique you use, you have to figure out what works best for you. If you find yourself struggling to complete your assignments, it may be time to re-evaluate your approach and try something new. Mason’s Learning Services offers additional resources to aid graduate students with reading strategies, including workshops, academic coaching, and online videos . Visit the Learning Services website for more information.

The proceeding blog has been edited and updated to showcase the most current information about Mason’s resources for graduate and professional students. Changes and edits were made by the editor. Edited on 10/13/2020 and 1/25/2022.

FounderScholar

- Kevin’s List (Invite Only)

How to Read Like a Doctoral Student

In his wildly popular 1986 book, All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten , author Robert Fulghum reminds readers of simple lessons they once learned but may have forgotten, lessons such as share everything, wash your hands before you eat, and of course, flush. During the past year, I’ve experienced the opposite of what Fulghum describes. Some things I’ve done my entire post-kindergarten life—that I thought I was pretty good at—I’ve had to relearn.

Things like reading and writing.

You see, I’ve just recently finished the first year of a business doctorate and the program forced me to revisit reading and writing skills I’ve always taken for granted.

In a recent twitter thread, I described my admittedly still brief experience in the program:

1/ Coming from industry to work on a business doctorate, many friends ask first, "Why the hell would you do something like that?" Then, they follow with, "So what do you do in a doctorate?" #phdchat — Kevin P. Taylor (@ktaylor) May 30, 2018

When friends, family, and people in my industry hear that I am pursuing a doctorate in my forties after a career in technology and entrepreneurship, they fall into one of two camps.

Firstly, there are the people who subconsciously savor the sight of a train wreck. These are the people who slow down and lean over to get a better view when passing a three-car pileup on the highway.

From these dear friends and relatives, I hear comments such as, “Wow, kudos to you but I’m so done with school. No way! So, what does it involve, anyway?”

When I tell the second group of friends and family about my educational plans and the “interesting” research projects I am pursuing, I’ll catch a sparkle in eye.

From these folks, I hear comments like, “I would love to do that someday. I almost applied to a Ph.D. program after undergrad but, you know, I had student loans to pay off. So, what does it involve, anyway?”

The short answer is reading, reading, and more reading.

In this blog post, I’ll share five techniques I’ve learned over the past year while learning how to read as a doctoral student, where I’m required to read, retain, and recall large amounts of complex information.

If you must absorb and make use of large quantities of information (everyone?), then you too will benefit from learning the powerful—but not easy—reading techniques that follow.

This is not the reading you learned in kindergarten.

5 Advanced Techniques to Learn How to Read More Effectively

In the past month, I’ve read 575 pages from scientific journals and academic book chapters in electronic format (either a PDF or a Kindle book). I’ve read several hundred additional pages in paper books.

This is a normal reading load in my program.

The reading doesn’t always go smoothly. Many time over the past year—usually after 10-12 hours of binge reading—my eyes would quiver and water.

At one point I could no longer focus my eyeballs on words. Imagine that feeling when trying to do your…let’s imagine…50th push-up but your arms just stop taking orders from your brain.

So, how do doctoral students read so much dense material and keep it all straight? Scientific articles are not reading cliffhangers. No Harry Potter or The Hunger Games 1 for doctoral students.

And, just as important, how do doctoral students retain and recall everything we’ve read?

During the first few months of my doctoral studies, it was clear I was coming into the program ill-equipped for the amount and type of reading that was expected. The techniques that follows are what I found work best for me. 2

Read with a Purpose in Mind

Do you read novels at work?

Probably not, if you’re like most people. You have job to do, for crying out loud. But, when you read like a doctoral student, reading is your job. You must treat it as such.

Keeping that in mind, every time I crack open a book or journal article, I do so with a clear purpose in mind.

I read to accomplish a predefined goal. When done, I don’t linger in the material, I move on. If you don’t take anything else away from this article, remember to read for a specific purpose.

Let’s look at some reasons I might need to read something. Depending on your job, you may come up with a different list.

Purpose for Reading

- When I start a new research topic, I likely don’t know much about it. I won’t be sure what research questions 3 to ask. What has already been discussed and researched? Who is writing and working in the area? When doing this type of survey-level reading, I stay at 30,000 feet. My goal is to understand terminology, categorization, schools of thought, common research methods, seminal works, and prolific authors.

- The world evolves over time and scientific knowledge is no exception. The state-of-the-art knowledge a year ago could now be refuted, retracted, or otherwise out-of-favor. Assuming I’ve developed a specific research question on a topic and understand the area broadly, I’ll want to delve into the specifics—detailed information on hypotheses, constructs, phenomena, models, methods, and theories.

- If I have a general understanding of a topic and know the current state of knowledge, I’ll want to learn what gaps exist in the current knowledge about a topic (e.g. the effect of passion on launching new ventures). If I have a specific question in mind, has it already been answered? If it has, am I convinced the answer is plausible? Or, are there reasons to doubt (e.g. are currently accepted conclusions built on shaky research or are the conclusions over-generalized)? If my research question hasn’t been answered yet, this could point to a possible research opportunity.

- Sometimes I need to acquire a new skill. For instance, I may need to test the reliability of a set of survey questions or I may need to perform a statistical analysis that I haven’t used before. In what ways have previous researchers already done the same things? (Precedent is important in science.)

Your method of reading should be driven by its purpose. To gather the right level of information with the least time investment, I read in layers.

Read in Layers

Imagine a journal article or academic book is an onion. Both consist of layers of material. And, both can make you cry.

Thinking of reading material as a series of layers to be peeled focuses my time and energy on only the layer that will best serve my purpose at that moment.

Layer One Scanning

The first layer of a piece is its outer shell. Layer one scanning reveals the most basic information. I use that information to decide if it is relevant to my purposes.

The output of layer one scanning is simply a list of relevant pieces I will later read for layer two survey-level information.

For a journal article, 4 the first layer is comprised of just the title and abstract.

Together the title and abstract should contain enough information to decide if the article warrants closer examination.

The first layer of a book includes its title, cover material, table of contents, and any relevant book reviews.

If I believe a piece could be useful to my research, I move it to a second layer reading to understand its background, conclusions, and key points.

Layer Two Reading

Layer two reading is the scientific equivalent of CliffNotes™.

The second layer of a journal article is comprised of the abstract, introduction, and conclusion, also known as the AIC . In layer two reading, I quickly read the abstract, introduction and conclusion and lightly skim the method and analysis sections and all tables and figures.

A book’s second layer consists of its preface, introduction, table of contents, chapter introductions and conclusions, and, again, any figures and tables. In addition, I skim the body of each relevant chapter looking for important nuggets. This will give me a fair approximation of a book’s contents with only a few hours investment.

Layer Three Reading

The third layer of a piece represents its nitty-gritty details.

A third layer reading is a full, detailed examination of the entire piece (article or book). At this level of reading, I engage deeply with the material, reading it front to back, closely examining every figure and table, every claim or finding, every step of its narrative.

Clearly, I reserve third layer reading to pieces that are highly relevant to my topic of interest.

While reading each progressive layer of material, I highlight and annotate. In other words, I engage the author in a conversation via the margins of the piece.

Converse with the Author

Active learning increases information retention and recall. In fact, systems such as the SQ3R Method provide a well-trodden approach to active reading.

My version of active reading includes reading in layers (action) and conversing with the author (another action) at increasing levels of detail. Conversing with the author requires both systematically highlighting text and scribbling comments in the margins.

The deeper I read, the more I converse. The conversation should heat up as I develop a more nuanced view of the piece.

Highlight and Annotate

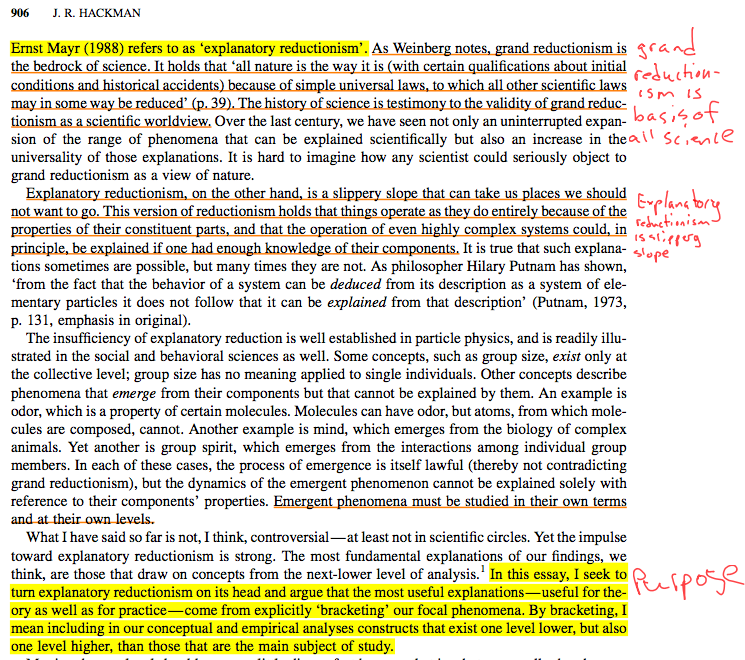

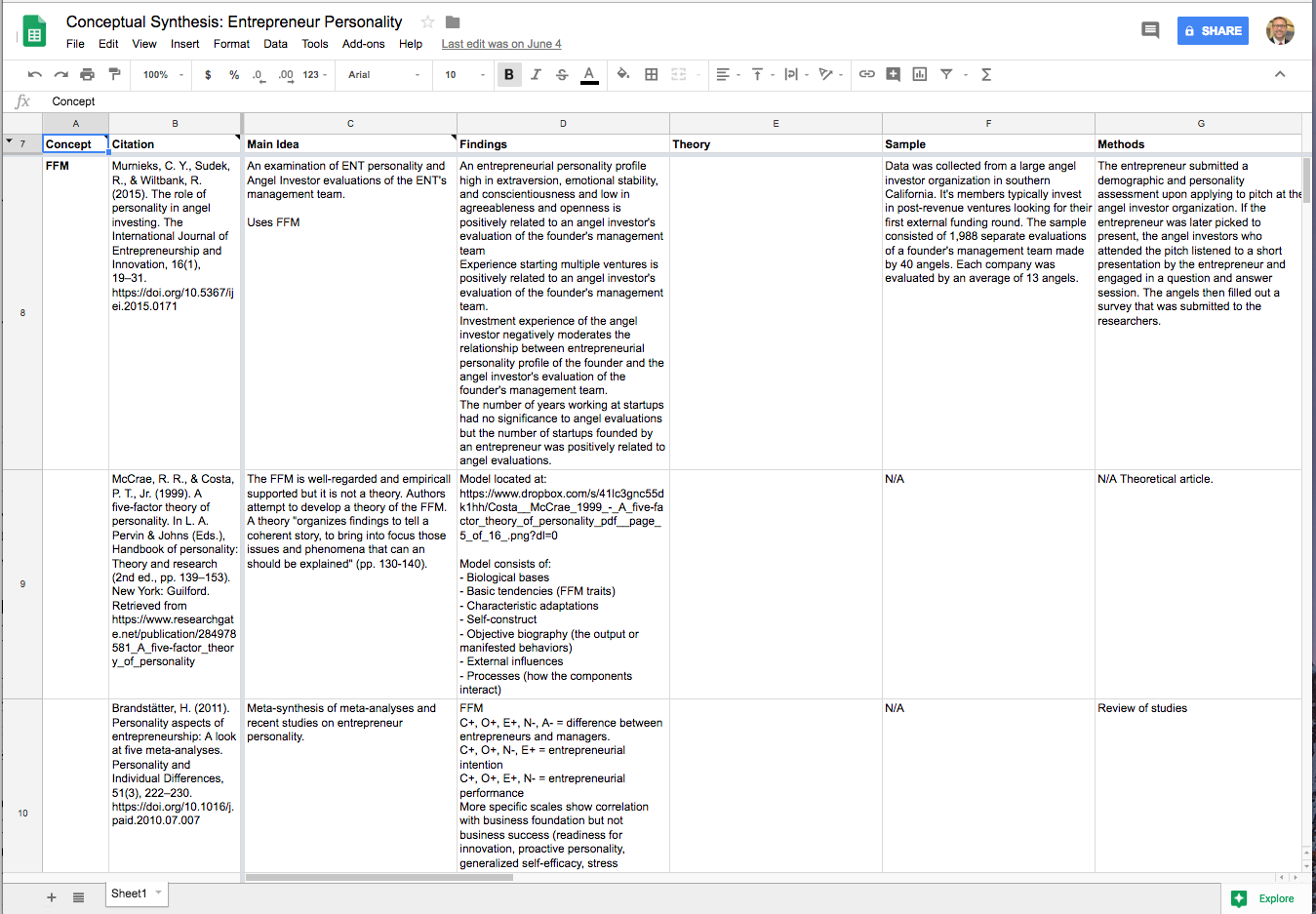

When I read in layer two, focusing on the abstract, introduction, and conclusion, I highlight the most important points in yellow, usually less than one sentence per paragraph. Orange highlighting designates supporting points, while sky blue marks any references I need to further examine.

In addition to structured highlighting, I write brief notes in the margins, questions, cross-references, etc. I specifically annotate the following:

- Purpose of the piece,

- Gaps addresses,

- Gaps not addressed,

- Sketch out the theoretical model,

- Hypotheses,

- Sample and methods used (survey, experiment, etc.),

- Findings, and

- Obvious inconsistencies, questions, or cross references to related material.

Make Up Your Own Shorthand

I use my own homemade shorthand:

- “RI” is for a research idea,

- “Q” is for a question,

- Empty Square is a to-do item (i.e. a checkbox),

- “Gap” identifies a gap in the literature,

- “RQ” is the piece’s research question.

Here is an example of an article I recently read at layer three for a research methods class:

Consume instead of Preserve

If you are anything like me, you love books. You probably have stacks of books sitting near your chair as you read this. Like me, you might even have some in protective covers.

But when I read to learn, I consume my material. I destroy books and journal articles with highlighters and red pens.

Yes, deface, mutilate.

Here’s a recently defaced PDF:

I should be clear, though. I only deface books in electronic format or books still in print that I can easily replaced.

If a book is out-of-print or borrowed (e.g. from a library), I never mark in it but instead use plenty of sticky notes.

The point is that purposeful reading of a book or article is important work. Work often requires consuming resources.

The book or journal article is there to serve my purpose.

Summarize and Synthesize the Material

After spending time reading, highlighting and annotating an article or book, it is time to put the new information in context and make sure it is available for future recall.

Unlike the ancients and their method of loci 5 people today are not trained to retain and recall vast quantities of detailed information using memory alone.

Instead of trying to remember everything using my sketchy-at-best memory, I use a structured process of summarizing and synthesizing new information. How in-depth I do this depends on the reading layer in which I’m operating.

During layer one reading I’m simply trying to collect and organize relevant sources for later use. During my searches, if a piece looks interesting based on its title and abstract, I simply import the reference into Zotero 6 7 , my citation management software.

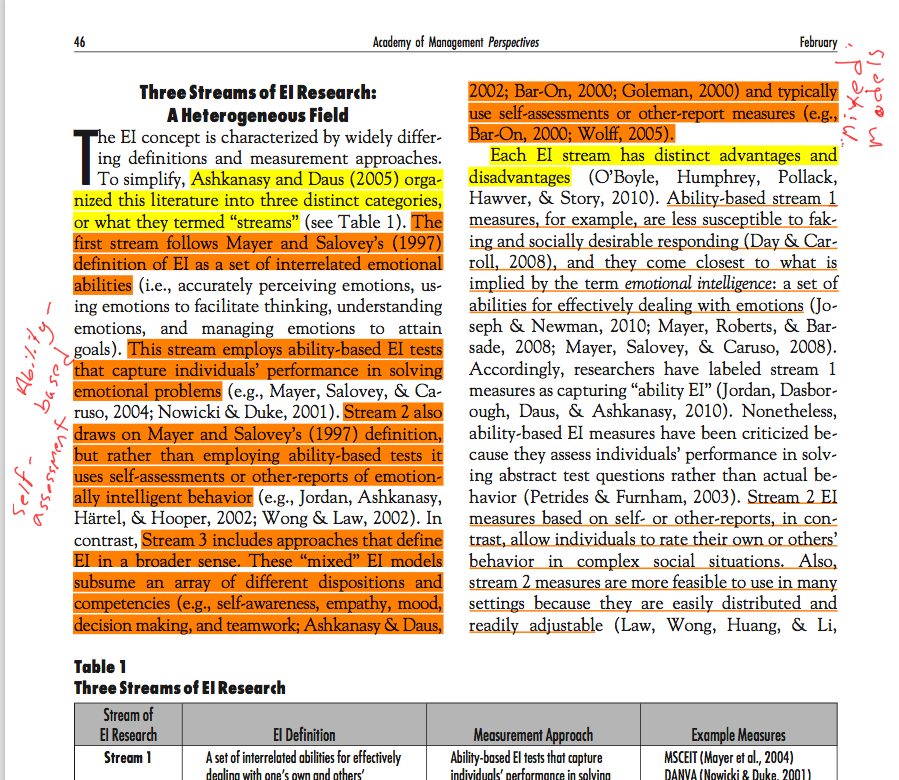

After a layer two reading, I will have highlighted and annotated the most important parts of the book or article. Immediately after reading—or better, while reading—I put notes into a structured Google Sheet called a “conceptual synthesis worksheet.”

I create one conceptual synthesis worksheet for each important keyword or concept in my research topic. These worksheets also correspond to the subfolders in my Zotero citation management software. For example, a current project has worksheets and Zotero subfolders for the following topics: Entrepreneur Personality, Angel Decision-Making, Angel Motivation, and Angel Investor Characteristics.

After layer two reading, in addition to populating a row in a conceptual synthesis worksheet, I often write (meaning sometimes write) a prose summary and synthesis of the piece in a structured “Journal Reading Summary Form.” In the JRSF, I address the following questions:

- What is the aim of the research? Specifically, what “big picture” practical question is highlighted and what more focused research question is addressed?

- Why should anyone care?

- What major theory(ies) are used to support the work?

- What methods are used to test the study’s hypotheses or research questions?

- What are the major findings/conclusions?

- What are the most important contributions of the research?

Early in my doctoral program, a professor handed out these questions to the class. But, there are several “how to read a journal article” documents floating around the Internet with similarly structured note-taking forms.

Layer three reading helps develop a deep understanding of a piece. In my experience, this only occurs after attempting to synthesizing the material with other research I’ve read and with my own thoughts.

Layer Three

Synthesizing material during level three reading requires developing an understanding of how the piece relates to the work of others and the work that I am doing. This is where I really question the material, think critically. Question everything: assumptions, methods, sample, validity, and reliability. Where are the contradictions? Do the conclusions make sense in the real world? What are the flaws (all research is flawed) and how could those flaws be overcome in future research?

I use one of two ways to synthesize material during layer three reading (deep reading). If a piece is not immediately needed, I write a stand-alone memorandum and store it in Zotero.

If I need the synthesis for a current project, I might also create a shortened version of the memorandum and include it in the project’s annotated bibliography , if it exists. In any case, I also save the AB entry in Zotero for future use.

Go Read Like a Doctoral Student

Whether you are a doctoral student, an entrepreneur, or engage in other knowledge work, the skills to efficiently filter through large amounts of information and purposefully capture and use just what you need can be a competitive advantage.

For example, I follow over a thousand blogs in my Feedly account . I check my account once a week or so and there are always hundreds of new posts.

I use similar techniques to what we’ve explored in this article to quickly scan at layer one, survey-level read at layer two and, rarely, dive deep at layer three. Blog posts and web pages that pass my layer one scan go into an Instapaper folder until I have time to read it at layer two.

My challenge to you today is, think about what we’ve discussed in this article. How can you use these techniques to stop reading…all…the…words…in a book or article and just read to accomplish your specific purpose?

What information organization system can you set up this week using Zotero, Evernote, Feedly, Instapaper, Google Drive, etc. to organize and manage the information you consume and want to recall?

Robert Fulghum, the author of All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten shared many useful lessons from kindergarten. But, even he assumed reading was a given. But reading at an advanced level, for a purpose, takes a systematic approach. Now you have the necessary tools to do just that.

Share this post:

- Well, unless you happen to be a scholar researching Harry Potter or The Hunger Games .

- The techniques are not my invention and have been shamelessly borrowed from other smart people.

- Good research questions are ones that investigate something interesting, that are valuable either practically or theoretically, and that can possibly be answered given the researcher’s resources, time frame, and skill set.

- Journal articles follow consistent formats. Quantitative articles often contain an abstract, introduction, method, analysis, discussion, and conclusion section.

- Also know as memory palaces.

- Zotero has a powerful “Connector,” or browser plugin, that makes it easy to import sources directly from web pages and library databases.

- Each of my writing projects might use 5-8 Zotero subfolders to organize the material. You could alternatively use another citation database, or even Evernote , Google Drive , or Dropbox for organization.

Related Articles

Sign up to explore the intersection of evidence-based knowledge and hands-on startup experience..

Several times a month you’ll receive an article with practical insight and guidance on launching and growing your business. In addition, you’ll be exposed to interesting, influential or useful research, framed for those in the startup community.

Thanks a lot for this article, so helpful as a new PhD candidate. I especially liked the Layer reading method and conceptual synthesis worksheet.

Thanks, Sarah — good luck with your PhD.

This is really a helpful article,I have gotten a couple of nuggets from it,I plan to use them during my researches.Glad I stumbled on this article.

Really helpful article. I know I am replying multiple years later, but I have a question. How do you do all this and still read multiple journal articles? It takes me several hours just to finish a single article by reading through, so I can barely get to the next article I have to read. What enabled you to do all of this layered reading and writing for one paper that you read and still be able to read other papers without it taking millenia?

Scott, thanks for the questions. In short, the point of the layers is to save myself time. I only read papers at layer 2 if layer 1 indicated it is relevant to my project. If not, I’ve just saved myself a lot of time. Layer 3 papers are the ones I spend the most time with but those are the most important papers and deserve the time.

If you are taking several hours to read each paper, let me reassure you that it will get faster, especially if you use a triage system like the one I describe here. As you get to know a particular literature well, you will skim much of the front end of a paper because it’s repeating what you already know. You’ll be looking for the results and any anomalies or issues with the methods.

Good luck in your journey.

Wow I read this and got inspired, I did not feel anxious about the idea of reading until my eyes hurt or felt some discomfort. Wonderful writing! This is an article most PhD students need to see.

Thank you for this information. The conceptual synthesis worksheet will be very helpful to current and future research and assignments.

You’re welcome!

Kevin- This is awesome and incisive work. Love the practicality. Well Done!

Thanks for reading!

Glad you enjoyed the post. Thanks for the recommendation for “Digital Paper.” I’m eager to learn more techniques. I’ve read the skimming, scanning, extracting terminology the book description mentions but it looks like it is more extensive than what I’ve seen previously. I’ll check it out.

Great writeup Kevin!

I wanted to pass on a related reading, “Digital Paper” by Andrew Abbott (Sociology prof @UChicago), which is about the art of scholarly library research. He has 7 stages (“design, search, scanning/browsing, reading, analyzing, filing, and writing”), which has some similarities to how you outlined your process in this post.

http://www.press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/D/bo18508006.html

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

- Another Degree of Success

- Graduate School Blog

How to Read Like a Grad Student

If you follow our Instagram stories, you know that we are fans of Zachary Shore’s Grad School Essentials. Your interest is peaked, and you’re now here to dive deeper.

Congratulations, you are already thinking like a grad student!

Now let’s get you reading like a grad student!

Understanding how to dissect and critique texts efficiently can be a huge time saver in grad school. Professors assign so much reading, and you’re left wondering if there are enough hours in the day to read them, especially if you’re expected to read every single word. What happens if you try? In Shore’s words, you're likely to become a “book zombie.” How often have you read a page, or even several pages, stopped and thought, “What did I just read?” That is the entryway to becoming a book zombie.

Whether reading a scholarly book or an article in a research journal, the following tips will help you comprehend more and save time.

Read for the thesis. The thesis is the author’s main argument. Your goal as a grad student is to find the argument and, ultimately, to critique it.

1. Analyze the Title & Subtitle: The title provides a first clue to the thesis. Subtitles can dig a little deeper into the direction the author is heading. Think actively by dissecting the meaning behind the title and subtitle. Ask yourself what the author might be trying to convey.

2. Scrutinize the Table of Contents: Review the titles of each chapter next. Just like the title of the book, they provide clues as to what the author is arguing. Each chapter serves as a key piece of evidence in the argument, with the chapter titles identifying the main point.

3. Read the Conclusion First: Conclusions summarize the big idea that the author has worked so hard to convey. Once you locate the thesis within the conclusion, restate or rephrase it and write it down in the simplest terms possible.

4. Read the Introduction: Now it’s time to start from the beginning. Find the thesis in the introduction. It will likely be worded differently than the conclusion, but the point is the same. Restate or rephrase the argument and write it down. Compare your intro summary to your summary from the conclusion. If they match, you found your thesis. If they don’t align, it means you need to take a look again. You may have misidentified the thesis or misunderstood it.

5. Target Key Chapters & Sections: Once the thesis is clear, it’s time to identify and understand the evidence the author uses to back up the argument. The evidence is found in individual chapters and sections of the book or article. Write down the big claim being made in each chapter, later you can review and determine if each claim is supported with sufficient evidence and logic. Now you’re thinking about the bigger picture. How does the thesis and evidence link to a larger question?

6. Concentrate on Subheadings & Topic-Sentences: Analyzing a text needs to be done in an efficient way to save time. Actively skim the chapters with an eye to the argument and evidence. Read subheadings and topic sentences to determine how much to give to the entire paragraph. As you identify the key evidence, restate or rephrase it and write it down.

After identifying the thesis and supporting arguments, focus on the sections and evidence that matters most.

Adopt this approach, and you’ll be ready to discuss the assigned readings. Whether in class or in a written assignment, your professor will have no doubt that you understood what you read.

A key strategy for Shore is to restate or rephrase what you read in your own words. Doing so helps you understand and retain the thesis and supporting arguments. Plus, being able to articulate the thesis and evidence in your own words is essential when critiquing the text.

Next Up: How to Critique Texts Like a Pro: A Summary From Grad School Essentials

- Graduate School

Keep Exploring

Celebrating excellence: dr. susanna garcia, our 2024 grand marshal.

Today, we celebrate Professor Emerita Susanna Garcia, a pianist and educator, whose 31 years of service in the School of Music and Performing Arts at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette are marked by her impressive dedication, innovation, and mentorship.

- Request Information

- Visit Campus

- [email protected]

- Login / Register

How to Read Research Papers Like a PhD Student

Article 28 Jul 2024 226 0

Reading research papers is an essential skill for any academic or student, especially those pursuing advanced degrees. However, it can be a daunting task for many. This post will explore effective methods for reading academic papers, strategies for understanding scientific research papers, techniques for analyzing research papers, and how to critically evaluate academic articles. By the end of this guide, you will be equipped with PhD-level techniques for reading research papers effectively.

Common Mistakes Students Make While Reading Papers

| Reading research papers can be challenging, and many students make several common mistakes that hinder their understanding and analysis of the material. Here are a few: : Many students read research papers from start to finish without prioritizing sections that provide the most valuable information first. : Skimming for main ideas and key points is a crucial skill that many students overlook. : Research papers follow a specific structure, and understanding this can help in comprehending the content better. : Effective note-taking is essential for summarizing and remembering key points. : The references section can provide valuable context and additional sources of information. |

Differences in Reading Approaches Between Undergraduate Students and PhD Students

Undergraduate students often approach reading research papers differently than PhD students. Understanding these differences can help in adopting more effective reading strategies.

Undergraduate Students

- Surface Reading : Often focus on getting through the material rather than understanding it deeply.

- Limited Context : May not have enough background knowledge to fully grasp complex concepts.

- Passive Approach : Tend to read passively without questioning or critically analyzing the content.

PhD Students

- Deep Reading : Focus on understanding the content deeply and critically.

- Extensive Context : Have a broader background knowledge, enabling them to understand complex concepts better.

- Active Approach : Actively question and analyze the content, looking for gaps, assumptions, and implications.

Step-by-Step Guide on How to Read a Research Paper Efficiently

Reading a research paper efficiently requires a structured approach. Here’s a step-by-step guide:

Step 1: Skim the Paper First

Before diving deep into the content, skim the paper to get an overview of its structure and main points. Focus on:

- Title and Abstract : Provides a summary of the research question, methods, results, and conclusions.

- Introduction : Sets the context and states the research question or hypothesis.

- Headings and Subheadings : Gives an idea of the paper’s structure and main sections.

- Figures and Tables : Visuals often highlight key data and findings.

Step 2: Read the Introduction and Conclusion

The introduction provides background information and states the research question or hypothesis. The conclusion summarizes the findings and their implications. Reading these sections first gives you a context for understanding the rest of the paper.

Step 3: Understand the Methodology

The methodology section explains how the research was conducted. Understanding this section is crucial for evaluating the validity and reliability of the findings. Look for details on:

- Study Design : Type of study (e.g., experimental, observational).

- Participants : Who was involved in the study.

- Procedures : Steps taken to conduct the research.

- Data Analysis : Methods used to analyze the data.

Step 4: Analyze the Results

The results section presents the findings of the research. Focus on:

- Key Findings : What the study found.

- Figures and Tables : Visual representations of the data.

- Statistical Analysis : Significance of the results.

Step 5: Critically Evaluate the Discussion

The discussion section interprets the results and places them in context. Look for:

- Interpretation of Results : How the authors interpret their findings.

- Limitations : Acknowledged weaknesses or limitations of the study.

- Future Research : Suggestions for future research directions.

Step 6: Review the References

The references section can provide valuable additional sources of information and context. Reviewing the references can help you understand the broader research landscape.

Tips on Identifying the Main Argument and Key Points

| Identifying the main argument and key points of a research paper is crucial for understanding its significance. Here are some tips: : Usually found in the introduction, the thesis statement presents the main argument or research question. : Look for points that support the main argument. These are often highlighted in the headings and subheadings. : The first sentence of each paragraph often indicates the main point of that paragraph. : After reading each section, summarize it in your own words to ensure you understand the key points. |

Strategies for Note-Taking and Summarizing

Effective note-taking and summarizing are essential for retaining information and understanding research papers. Here are some strategies:

Note-Taking Techniques

- Annotation : Annotate the paper by highlighting important points and writing notes in the margins.

- Mind Mapping : Create a mind map to visualize the structure and main points of the paper.

- Digital Tools : Use digital tools like Evernote or OneNote to organize your notes.

Summarizing Techniques

- Paraphrasing : Rewrite the main points in your own words.

- Bullet Points : Use bullet points to list key points and findings.

- Abstract Summary : Write a brief summary that includes the main argument, methods, results, and conclusions.

Importance of Understanding the Paper’s Structure

Understanding the structure of a research paper is crucial for efficient reading and comprehension. Research papers typically follow a standard structure:

A brief summary of the research question, methods, results, and conclusions.

Introduction

Sets the context, states the research question or hypothesis, and outlines the paper's structure.

Methodology

Describes how the research was conducted, including the study design, participants, procedures, and data analysis methods.

Presents the findings of the research, often using figures and tables.

Interprets the results, discusses their implications, and suggests future research directions.

Lists the sources cited in the paper, providing additional context and information.

Examples of Effective Reading Techniques

Here are some examples of effective reading techniques that can help you read research papers like a PhD student:

Skimming for Main Ideas

Before diving into the details, skim the paper to get an overview of its structure and main points. Focus on the title, abstract, introduction, headings, and conclusion.

Highlighting Key Points

Use a highlighter to mark important points, key arguments, and significant findings. This makes it easier to review the paper later.

Making Margin Notes

Write notes in the margins to summarize key points, ask questions, or highlight important concepts. This helps in retaining information and making connections between different parts of the paper.

Creating Summaries

After reading each section, write a brief summary in your own words. This ensures you understand the content and helps in retaining information.

Using Digital Tools

Utilize digital tools like Mendeley, EndNote, or Zotero to organize and annotate research papers. These tools can help you manage your reading list, take notes, and cite sources.

Resources and Tools to Assist in Reading and Understanding Research Papers

| Several resources and tools can assist you in reading and understanding research papers more effectively: : A freely accessible web search engine that indexes the full text or metadata of scholarly literature. : A free search engine accessing primarily the MEDLINE database of references and abstracts on life sciences and biomedical topics. : A digital library for academic journals, books, and primary sources. : A reference manager and academic social network that can help you organize your research, collaborate with others online, and discover the latest research. : A reference management software package used to manage bibliographies and references when writing essays and articles. : A free, easy-to-use tool to help you collect, organize, cite, and share research. : An app designed for note-taking, organizing, task management, and archiving. : A digital notebook for capturing and organizing everything across your devices. : An all-in-one workspace where you can write, plan, collaborate, and get organized. |

Reading research papers like a PhD student requires a strategic and structured approach. By avoiding common mistakes, understanding the differences in reading approaches, and following a step-by-step guide, you can improve your ability to read, understand, and analyze academic papers effectively. Utilizing effective note-taking and summarizing strategies, understanding the paper’s structure, and using various resources and tools can further enhance your research comprehension and academic literacy. Implement these techniques to elevate your reading skills and achieve academic success.

- Latest Articles

Why Prompt Engineering? Benefits & Impact on AI Efficiency

The role of technology in education: opportunities & challenges, innovative ways to expand knowledge beyond the classroom, social and emotional learning for student well-being, ai and the future of humans: impact, ethics, and collaboration, why ai is the future: innovations driving global change, why critical thinking is important: skills and benefits explained, how information technology is shaping the future of education, the impact of ai on employment: positive and negative effects on jobs, ai’s influence on job market trends | future of employment, improve your writing skills: a beginner's guide, shifts in pop culture & their societal implications, personalized learning: tailored education for every student, 9 practical tips to start reading more every day, philosophy’s role in the 21st century: modern relevance, how to read faster and effectively | top reading strategies, negative impact of ai on employment: automation and job loss, apply online.

Find Detailed information on:

- Top Colleges & Universities

- Popular Courses

- Exam Preparation

- Admissions & Eligibility

- College Rankings

Sign Up or Login

Not a Member Yet! Join Us it's Free.

Already have account Please Login

How to Read Research Papers: A Cheat Sheet for Graduate Students

- August 4, 2022

- PRODUCTIVITY

It is crucial to stay on top of the scientific literature in your field of interest. This will help you shape and guide your experimental plans and keep you informed about what your competitors are working on.

To get the most out of your literature reading time, you need to learn how to read scientific papers efficiently. The problem is that we simply don’t have enough time to read new scientific papers in our results-driven world.

It takes a great deal of time for researchers to learn how to read research papers. Unfortunately, this skill is rarely taught.

I wasted a lot of time reading unnecessary papers in the past since I didn’t have an appropriate workflow to follow. In particular, I needed a way to determine if a paper would interest me before I read it from start to finish.

So, what’s the solution?

This is where I came across the Three-pass method for reading research papers.

Here’s what I’ve learned from using the three pass methods and what tweaks I’ve made to my workflow to make it more personalized.

Build time into your schedule

Before you read anything, you should set aside a set amount of time to read research papers. It will be very hard to read research papers if you do not have a schedule because you will only try to read them for a week or two, and then you will feel frustrated. An organized schedule reduces procrastination significantly.

For example, I take 30-40 minutes each weekday morning to read a research paper I come across.

After you have determined a time “only” to read research papers, you have to have a proper workflow.

Develop a workflow

For example, I follow a customized version of the popular workflow, the “Three-pass method”.

When you are beginning, you may follow the method exactly as described, but as you get more experienced, you can make some changes down the road.

Why you shouldn’t read the entire paper at once?

Oftentimes, the papers you think are so important and that you should read every single word are actually worth only 10 minutes of your time.

Unlike reading an article about science in a blog or newspaper, reading research papers is an entirely different experience. In addition to reading the sections in a different order, you must take notes, read them several times, and probably look up other papers for details.

It may take you a long time to read one paper at first. But that’s okay because you are investing yourself in the process.

However, you’re wasting your time if you don’t have a proper workflow.

Oftentimes, reading a whole paper might not be necessary to get the specific information you need.

The Three-pass concept

The key idea is to read the paper in up to three passes rather than starting at the beginning and plowing through it. With each pass, you accomplish specific goals and build upon the previous one.

The first pass gives you a general idea of the paper. A second pass will allow you to understand the content of the paper, but not its details. A third pass helps you understand the paper more deeply.

The first pass (Maximum: 10 minutes)

The paper is scanned quickly in the first pass to get an overview. Also, you can decide if any more passes are needed. It should take about five to ten minutes to complete this pass.

Carefully read the title, abstract, and introduction

You should be able to tell from the title what the paper is about. In addition, it is a good idea to look at the authors and their affiliations, which may be valuable for various reasons, such as future reference, employment, guidance, and determining the reliability of the research.

The abstract should provide a high-level overview of the paper. You may ask, What are the main goals of the author(s) and what are the high-level results? There are usually some clues in the abstract about the paper’s purpose. You can think of the abstract as a marketing piece.

As you read the introduction, make sure you only focus on the topic sentences, and you can loosely focus on the other content.

What is a topic sentence?

Topic sentences introduce a paragraph by introducing the one topic that will be the focus of that paragraph.

The structure of a paragraph should match the organization of a paper. At the paragraph level, the topic sentence gives the paper’s main idea, just as the thesis statement does at the essay level. After that, the rest of the paragraph supports the topic.

In the beginning, I read the whole paragraph, and it took me more than 30 minutes to complete the first pass. By identifying topic sentences, I have revolutionized my reading game, as I am now only reading the summary of the paragraph, saving me a lot of time during the second and third passes.

Read the section and sub-section headings, but ignore everything else

Regarding methods and discussions, do not attempt to read even topic sentences because you are trying to decide whether this article is useful to you.

Reading the headings and subheadings is the best practice. It allows you to get a feel for the paper without taking up a lot of time.

Read the conclusions

It is standard for good writers to present the foundations of their experiment at the beginning and summarize their findings at the end of their paper.

Therefore, you are well prepared to read and understand the conclusion after reading the abstract and introduction.

Many people overlook the importance of the first pass. In adopting the three-pass method into my workflow, I realized that many papers that I thought had high relevance did not require me to spend more time reading.

Therefore, after the first pass, I can decide not to read it further, saving me a lot of time.

Glance over the references

You can mentally check off the ones you’ve already read.

As you read through the references, you will better understand what has been studied previously in the field of research.

First pass objectives

At the end of the first pass, you should be able to answer these questions:

- What is the category of this paper? Is it an analytical paper? Is it only an “introductory” paper? (if this is the case, probably, you might not want to read further, but it depends on the information you are after)or is it an argumentative research paper?

- Does the context of the paper serve the purpose for what you are looking for? If not, this paper might not be worth passing on to the second stage of this method.

- Does the basic logic of the paper seem to be valid? How do you comment on the correctness of the paper?

- What is the main output of the paper, or is there output at all?

- Is the paper well written? How do you comment on the clarity of the paper?

After the first pass, you should have a good idea whether you want to continue reading the research paper.

Maybe the paper doesn’t interest you, you don’t understand the area enough, or the authors make an incorrect assumption.

In the first pass, you should be able to identify papers that are not related to your area of research but may be useful someday.

You can store your paper with relevant tags in your reference manager, as discussed in the previous blog post in the Bulletproof Literature Management System series.

This is the third post of the four-part blog series: The Bulletproof Literature Management System . Follow the links below to read the other posts in the series:

- How to How to find Research Papers

- How to Manage Research Papers

- How to Read Research Papers (You are here)

- How to Organize Research Papers

The second pass (Maximum: 60 minutes)

You are now ready to make a second pass through the paper if you decide it is worth reading more.

You should now begin taking some high-level notes because there will be words and ideas that are unfamiliar to you.

Most reference managers come with an in-built PDF reader. In this case, taking notes and highlighting notes in the built-in pdf reader is the best practice. This method will prevent you from losing your notes and allow you to revise them easily.

Don’t be discouraged by everything that does not make sense. You can just mark it and move on. It is recommended that you only spend about an hour working on the paper in the second pass.

In the second pass:

- Start with the abstract, skim through the introduction, and give the methods section a thorough look.

- Make sure you pay close attention to the figures, diagrams, and other illustrations on the paper. By just looking at the captions of the figures and tables in a well-written paper, you can grasp 90 percent of the information.

- It is important to pay attention to the overall methodology . There is a lot of detail in the methods section. At this point, you do not need to examine every part.

- Read the results and discussion sections to better understand the key findings.

- Make sure you mark the relevant references in the paper so you can find them later.

Objectives of the second pass

You should be able to understand the paper’s content. Sometimes, it may be okay if you cannot comprehend some details. However, you should now be able to see the main idea of the paper. Otherwise, it might be better to rest and go through the second pass without entering the third.

This is a good time to summarize the paper. During your reading, make sure to make notes.

After the second pass, you can:

- Return to the paper later(If you did not understand the basic idea of the paper)

- Move onto the thirst pass.

The third pass (Maximum: four hours)

You should go to the third stage (the third pass) for a complete understanding of the paper. It may take you a few hours this time to read the paper. However, you may want to avoid reading a single paper for longer than four hours, even at the third pass.

A great deal of attention to detail is required for this pass. Every statement should be challenged, and every assumption should be identified.

By the third pass, you will be able to summarize the paper so that not only do you understand the content, but you can also comment on limitations and potential future developments.

Color coding when reading research papers

Highlighting is one way I help myself learn the material when I read research papers. It is especially helpful to highlight an article when you return to it later.

Therefore, I use different colors for different segments. To manage my references, I use Zotero. There is an inbuilt PDF reader in Zotero. I use the highlighting colors offered by this software. The most important thing is the concept or phrase I want to color code, not the color itself.

Here is my color coding system.

- Problem statement: Violet

- Questions to ask: Red (I highlight in red where I want additional questions to be asked or if I am unfamiliar with the concept)

- Conclusions: Green (in the discussion section, authors draw conclusions based on their data. I prefer to highlight these in the discussion section rather than in the conclusion section since I can easily locate the evidence there)

- Keywords: Blue

- General highlights and notes: Yellow

Minimize distractions

Even though I’m not a morning person, I forced myself to read papers in the morning just to get rid of distractions. In order to follow through with this process (at least when you are starting out), you must have minimum to no distractions because research papers contain a great deal of highly packed information.

It doesn’t mean you can’t have fun doing it, though. Make a cup of coffee and enjoy reading!

Images courtesy : Online working vector created by storyset – www.freepik.com

Aruna Kumarasiri

Founder at Proactive Grad, Materials Engineer, Researcher, and turned author. In 2019, he started his professional carrier as a materials engineer with the continuation of his research studies. His exposure to both academic and industrial worlds has provided many opportunities for him to give back to young professionals.

Did You Enjoy This?

Then consider getting the ProactiveGrad newsletter. It's a collection of useful ideas, fresh links, and high-spirited shenanigans delivered to your inbox every two weeks.

I accept the Privacy Policy

Hand-picked related articles

Why do graduate students struggle to establish a productive morning routine? And how to handle it?

- March 17, 2024

How to stick to a schedule as a graduate student?

- October 10, 2023

The best note-taking apps for graduate students: How to choose the right note-taking app

- September 20, 2022

Leave a Reply Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Name *

Email *

Add Comment *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Post Comment

10 Reading Strategies for PhD Students To Improve Long-Term Accessibility of Information

Dec 18, 2020

Have you checked out the rest of The PhD Knowledge Base ? It’s home to hundreds more free resources and guides, written especially for PhD students.

Author: Paul Druschke

Everyone’s PhD is different, but one aspect of this academic journey is a constant: There is a lot to read. No matter the discipline, there are always hundreds of articles, books, and other media that are relevant to your research – and even more literature that is not.

A PhD is therefore more than your typical term paper for which you consult a dozen or so texts. Instead of tens, there are hundreds of articles, chapters, graphs, tables, videos and more you need to keep an eye on. As it is difficult to judge a book by its cover, you will probably also spend a lot of time reading texts that turn out to be insignificant.

No matter its importance, new information is first stored in your short-term memory, which makes it susceptible to two limiting factors: duration and capacity.

View it like a continuously recording surveillance camera. It is always taking in and saving new information, but once the file gets too big, previous data gets deleted. To preserve something noteworthy, that piece gets saved and can be accessed later on.

Hello, Doctor…

Sounds good, doesn’t it? Be able to call yourself Doctor sooner with our five-star rated How to Write A PhD email-course. Learn everything your supervisor should have taught you about planning and completing a PhD.

Now half price. Join hundreds of other students and become a better thesis writer, or your money back.

Why should I use reading strategies?

Now there is good news and bad news. While we unfortunately cannot transfer information to the easily accessible long-term memory by simply pushing a button, we can employ consolidation methods such as repetition and mnemonic devices to store our knowledge in our long-term memory. The bad news, though, is that our long-term memory is only theoretically unlimited, and it is also not safe from decay over time.

However, not all is lost. There are strategies that will help you to retain the information you find in articles, books, or any other type of media. In fact, there is quite a range of products. We have… C2R, PQ4R, SQP2RS, maybe even some OK5R or SQRQCQ.

No, these aren’t black market cognition-enhancing drugs. They are actually abbreviating strategies aimed at structuring the reading process. They each propose various steps to be followed when reading a text to guide you through certain sections with various means. Feel free to try some of them for yourself, but be aware that there is always more to it than just working on the text itself.

The benefits of a structured approach to reading

You need to acknowledge that reading isn’t something you can just do on the side. It requires your attention from the beginning to the end, or else you will keep needing to re-read because you missed a connection. Especially for complicated literature, using a structured approach can help your understanding.

No matter which steps each strategy wants you to follow throughout the reading process, all of them share a common goal: to make reading easier for you and to gain quicker access to the information you actually need. And once you find a method that works for you, you can save both time and energy, while also building up your literary knowledge and becoming an expert in your field.

Taking the amount of literature and the limitations of our cognitive capacity into account, we need to consider strategies that’ll help keep important information accessible in the long run.

There are three major areas which you can manipulate when it comes to reading for your PhD: before, while, and after working on a text.

So, let us explore which actions you can take to read better and improve long-term accessibility of new information.

Your PhD thesis. All on one page.

Use our free PhD structure template to quickly visualise every element of your thesis.

Pre-Reading

- You don’t just put a dozen chemicals into a container, shake them up, and hope for them to turn into gold. (Chemists, please correct me if I am wrong.) So why should it be the same with literature? While it might be possible to just read whatever you find and make sense of it later on, you should consider getting an overview of your bibliography first, group texts on the same domain together, and differentiate between basic and advanced literature.

- Create a distraction-free environment. Your smartphone’s notifications will only disrupt your reading flow, so turn them off. The text in front of you should be the only thing keeping your mind busy. It might be hard to disconnect for a while, but being in the right state of mind will help you process the text more effectively.

- Get an idea of the text in front of you. Skim the text for its headings to understand how it is divided. Taking visual material such as graphs, pictures, or tables into account can also point you toward crucial sections. The point is to narrow down which sections of a text are relevant to you, so you are not wasting time with reading irrelevant chapters.

While-Reading

- Even if you have selected the parts you deem necessary, do not read them from the beginning to the end immediately. Instead, search for specific keywords that are of interest for your research in the introductory paragraphs as well as the summaries. This can reduce your final workload even more. You can always go back to an article or text later on, but remember that unnecessary information can overwrite important information in your short-term memory.

- Depending on how much time you have, the difficulty of the text, and how fast you can read, you can now choose between reading the remaining sections from start to finish (this may be better for understanding logical connections), or scanning the text for keywords and surrounding sentences.

- Take the pressure off your short-term memory by highlighting important sections of the text, adding comments to help you reconstruct your thoughts and deductions during a later reading, and adding page markers to point to relevant paragraphs. Once you have dealt with the text, create a summary, e.g. on a flashcard, containing basic metadata such as author(s), year, and the title, and the information you want to take away from it. When done right, looking at these notes can replace the need to go back into the original text. There are many programs you can use to make digital libraries of your literature. While their primary purpose is to collect all the metadata and help you to generate citations, you can also add keywords, comments, and reviews to each entry. Much to the flashcards, such organization can make specific information readily accessible at a later point in time, and you can integrate cross-references between your texts

- Take breaks, ideally after some breakthrough or a completed section as defined by yourself, e.g. one article, two chapters, thirty minutes. You can use them to give the new information a second thought, get your dopamine rush by checking all the ever so important notifications on your smartphone, or to relax for a moment.

- Reading for a long period of time, especially on a digital display, can cause your eyes to get dry and you might develop trouble focusing. Give them some rest, e.g. by closing them for a while or looking into the distance. You may consider increasing the font size for digital texts or adjusting the lights when reading from paper.

Post-Reading

- To transfer the knowledge into your long-term memory, you should periodically repeat the information and deductions you gathered from the texts. By revisiting previously read literature, you may now view them with a different perspective or make new connections.

- It can be difficult to change your habits and you may not have liked the approach you took with the first few texts. Take some time to reflect on the strategy used to work on the literature and whether it really saved you time, helped you in narrowing down the essential information, and increased the information’s accessibility. Figure out which step causes you trouble and try fine-tuning it.

No matter the length or difficulty of the next text on your pile of literature, you should now be well-equipped to work on it. Changing your typical way of reading might at first feel a bit unfamiliar, but I encourage you to embrace this feeling and to knowingly reflect upon the changes you experience. Academic reading is not easy, but you can make it easier.

Paul Druschke is an early career academic and PhD researcher at the Technische Universität Dresden in Germany. Aside from his research at the Institute of Geography, he is teaching courses on academic writing, time and stress management, and leadership competencies. Find him on Twitter and Instagram @pauldruschke.

Share this:

Hi, do you have a document/pdf article on this?

You should be able to click ‘file>save page as’ in your web browser and then select save as PDF.

Hi, thank you for this article! As a new PhD student, I find this really helpful!

Great! Best of luck as you go along the PhD journey. It’s a wild ride, but 100% worth it.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Search The PhD Knowledge Base

Most popular articles from the phd knowlege base.

The PhD Knowledge Base Categories

- Your PhD and Covid

- Mastering your theory and literature review chapters

- How to structure and write every chapter of the PhD

- How to stay motivated and productive

- Techniques to improve your writing and fluency

- Advice on maintaining good mental health

- Resources designed for non-native English speakers

- PhD Writing Template

- Explore our back-catalogue of motivational advice

Doctoral Student Guide

- Kemp Library Video Tutorials

- Advanced Search Techniques

- Tools for Educators

- D.H.Sc. Resources

- Database Video Tutorials

- Online/Electronic Resources

- Google Scholar

- Peer Reviewed

- How to confirm and cite peer review

- What are...

- Action Research

- ESU Off Campus Log In

- Primary/Secondary Sources

- Legal Research Resources

- Evidence Based Practice/Appraisal Resources

- Apps You Didn't Know You Needed

- Internet Searching

- Online Learning Study Tips

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Reviews

- Thesis Guide

- Who is citing me?

- Dissertation/Thesis Resources

- Citations APA

- Journal Impact Factors

- Class Pages

- We Don't Have It? / Interlibrary Loan

- Questions After Hours

This page contains resources on how to be a better reader (for specific help on reading journal articles look under the Find Articles tab). It also includes various ideas on note-taking, and ideas and strategies for studying. There are written articles/editorials and videos. Resources are listed in no particular order.

Please review for what works best for you. If you have a method that you find works better for you that is not here, please let me know so I can include it!

Need help with writing? Try these resources from the University of North Carolina.

- Videos on reading

- Note-Taking

- Videos on Note-taking

- Videos on studying

- Aimed more towards for-fun reading, but has some good advice

- Again towards for-fun reading, but has tons of additional links and good advice.

- How to improve reading comprehension advice

- Reading a textbook quickly and effectively

There are a bunch of videos in the next tabs that discuss a variety of different types of reading strategies - how to read faster, how to read a textbook, how to increase reading comprehension, etc.

- Taking notes while reading from the University of North Carolina

- 5 Effective Note Taking strategies from Oxford Learning.com

- 5 Note Strategies, with written and video explanations. And Street Fighter characters to illustrate.

- Not techniques so much as practical advice

- 36 Examples and Free Templates on the Cornell Method

- Blank note taking templates

- LifeHack notetaking tips

- The complete study guide for every type of learner - explains different kinds of learners and what study methods might work best for you based on how you learn information best

- Studying 101: Study Smarter Not Harder : from the University of North Carolina

- Studying Guide from Oregon State University

- << Previous: Internet Searching

- Next: Online Learning Study Tips >>

- Last Updated: Sep 13, 2024 12:01 PM

- URL: https://esu.libguides.com/doc

News & Stories

Copyright © 2023 EduEarth - All Rights Reserved.

- Privacy Policy

Cookie Policy

This website uses cookies. By continuing to use this site, you accept our use of cookies. Read our Privacy Policy .

how to: 5 ways to read like a lit scholar

[a few critical reading tactics i learned during my 3 english degrees].

Oh, hi. It’s been a while! I took an unexpected hiatus from publishing here over the last 2 months, but I’m very excited to be back with some new ideas and formats to try out. Today, I’m sharing 5 ways you can start reading like a literature scholar, based on the reading best practices I learned in my decade as a literature student.

Thank you, as always,…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Closely Reading to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.

- EN Action Another action

- Free Counselling

Thanks for visiting TopUniversities.com today! So that we can show you the most relevant information, please select the option that most closely relates to you.

- Looking for undergraduate studies

- Looking for postgraduate studies

- Student but not looking for further education at the moment

- Parent or Guardian

- University administrator

- Professional

Thanks for sending your response.

Your input will help us improve your experience. You can close this popup to continue using the website or choose an option below to register in or login.

Already have an account? Sign in

6 Essential Study Tips for the PhD Student

Guest Writer

Share this Page

Table of contents

- Introduction

PhD study tip #1: Write early and write often

Phd study tip #2: read lots of papers, phd study tip #3: read other things, phd study tip #4: work in short sprints, phd study tip #5: focus on small signs of progress, phd study tip #6: don’t cut corners.

Guest post: Julio Peironcely

A PhD is definitely not a walk in the park. I know; I had my fair share of struggles as a PhD student . Productivity, motivation or coming up with scientifically sound ideas, you name it.

Luckily I had good mentors and I read inspiring books. I got good advice and study tips from both of these sources, and I would like to share some of the most useful advice I came across. These PhD tips are based on my own experience. Some I learned early on during my struggle as a PhD student, and others I wish had had learned earlier. I hope they can help you.

Obviously the more papers you write the better – but that’s not what I mean. I mean write as often as possible, even if you don’t have a paper on the horizon.

Start writing as early as possible in your PhD, and write regularly. Some people write daily, others once a week. The goal is to consistently document your progress, what you did, how, and the obstacles you encountered.

Writing early will help you to develop and maintain your writing skills for when the time comes to write a full-fledged paper. By writing often you will accumulate content that you can reuse when you need to write abstracts, papers or proposals.

I didn’t follow this PhD study tip myself and I regret it. I think I could have written my papers in half the time if I had. Not only this, their quality would have been much higher.

At the beginning of your PhD you have to read lots of papers. The goal is that you get a clear overview of your research field. You must understand all the important research already done. This is what people call the "state of the art”.

Once you know the state of the art in your field, you can see where your PhD fits in. How you are going to contribute and expand the scope of research? It also gives you a roadmap to avoid duplicating existing research and reinventing the wheel.

Once you have done most of the reading, you will need to keep track of new developments in your field, by reading new papers and speaking to others about what research is underway.

PhD students don’t just encounter academic problems; they also face challenges in time management, motivation or creativity. Reading papers may help you in some of these areas – but not always. That’s why you need to read other types of material.

Productivity, personal skills and business books can help you grow as a PhD student. They provide practical advice, including study tips and also general guidance on how to develop essential skills applicable in all kinds of roles.

Following blogs such as Thesis Whisperer, Next Scientist or TopUniversities.com can also help you boost your motivation and show you inspiring stories from other PhD students.

Remember that you must think creatively, and reading only one type of content (scientific papers in your specific field) may narrow your thoughts.

Another study tip that boosted my productivity came from the world of software development. Some people call this agile development, others talk about fast prototyping, short sprints, or ‘ship it fast and get feedback’.

Have you ever waited a long time to show something until you felt it was perfect, only to find that, well, the other person disagreed?

That waste of time is what you want to avoid. The idea here is to work very fast to produce something that is just good enough, show it, get feedback and improve it in another sprint. And iterate on and on.

One great time management technique based on the idea of working in short sprints is the Pomodoro Technique .

Halfway through my PhD I lost motivation because I felt I hadn’t produced anything substantial. My mistake was to bind my satisfaction to having reached important milestones like publishing a paper.

Wrong. Those things take too long. I needed some small doses of sweet PhD love along the way.

Once I started focusing on smaller signs of progress, everything started to look brighter. I knew that if on a given day I finished three small tasks then I was on the right track, I was making enough progress.

Instead of thinking “Am I there yet?” you should ask yourself, “Am I closer than I was three months ago?”

Testimonials

"CUHK’s MBA programme provided me with the stepping stone into a larger sports Asian market wherein I could leverage the large alumni network to make the right connections for relevant discussions and learning."

Read my story

Abhinav Singh Bhal Chinese University of Hong Kong graduate

"I have so many wonderful memories of my MBA and I think, for me, the biggest thing that I've taken away was not what I learned in the classroom but the relationships, the friendships, the community that I'm now part of."

Alex Pitt QS scholarship recipient

"The best part of my degree is getting to know more about how important my job as an architect is: the hidden roles I play, that every beautiful feature has significance, and that even the smallest details are well thought out."

Rayyan Sultan Said Al-Harthy University of Nizwa student

"An MBA at EAHM is superior due to the nature of the Academy’s academic and industry strength. The subject matter, the curriculum structure and the access to opportunities within the hospitality industry is remarkable."

Sharihan Al Mashary Emirates Academy of Hospitality Management graduate

So far we’ve focused on productivity study tips for the PhD student. These allow you to skip unnecessary tasks and focus on what really matters for your PhD. But there is one area where you cannot find shortcuts. That’s in your reputation.

During your PhD you may be tempted to do things that seem like a benefit in the short term, but that could harm your reputation in the long term. These shortcuts involve your credibility, your thoroughness and your accountability.

Imagine: after six months of preparing your paper, you are almost there. You find there’s a little mistake in the data, but you don’t think it will harm the overall outcome. So why waste your time fixing it? Or why cite all the relevant papers when with a few will do? Even worse, why not use somebody else’s method but not acknowledge that, so it looks like it was your own creation?

This sloppiness will eventually come back to haunt you. Sooner or later people won’t trust you. They will not want to collaborate with you. They will not cite your papers. So, even it if means extra work, stay away from cutting corners!

Julio Peironcely is the founder of NextScientist.com , a blog that aims to help PhD students succeed. He’s also the author of the free e-book 17 Simple Strategies to Survive Your PhD .

Want more content like this? Register for free site membership to get regular updates and your own personal content feed.

+ 3 others saved this article

+ 4 others saved this article

Recommended articles Last year

Top universities in Australia

How Future17 inspired me to work for human rights and social justice

How to get a full scholarship

Discover top-ranked universities!

universities

events every year

Sign up to continue reading

Ask me about universities, programs, or rankings!

Our chatbot is here to guide you.

QS SearchBot

Stack Exchange Network

Stack Exchange network consists of 183 Q&A communities including Stack Overflow , the largest, most trusted online community for developers to learn, share their knowledge, and build their careers.

Q&A for work

Connect and share knowledge within a single location that is structured and easy to search.

Am I reading enough of the scientific literature? Should I read for breadth or depth?

Ever since starting graduate school I've tried to make scientific reading a part of my daily ritual; I track pages read using Beeminder , and the graph doesn't lie. It keeps me honest.

I aim to closely read and summarize 5 pages per day and skim a few other abstracts besides that. I spend about half my time looking at data and figures which doesn't contribute to my daily "page count." When I'm reading about a new topic these five pages can take several hours, but on topics I have more background in five pages might only take an hour per day.

I guess since everybody defines "read" in a different way it's hard to get an objective answer about how much reading is enough. How much people read seems like a bit of a sensitive topic among real-life colleagues because everyone has a bit of anxiety that they aren't reading enough. But for those further along in their academic path, I'd like to hear how you approached the literature early in your graduate school career and what you think is a sufficient amount.

I guess this all distills down into two main topics:

When deciding what to read each day, should I focus on depth or breadth?

Is five pages of close reading per day enough? I know it doesn't sound like much, but it takes significant mental energy to meet that goal. And consistently reading 5 pages per day adds up to a lot over time.

Edited to add: I mostly read about petrology, volcanology, structural geology, and tectonics if that makes a difference. By "page" I mean "page of text" so if I'm reading a structural geology paper with lots of maps and figures I discount for those and a "ten page" paper becomes a 5 page paper for my purposes.

- productivity

- graduate-school

- 2 I have a blog post about how to sift the literature that you may find relevant: scienceinthesands.blogspot.com/2011/10/… – David Ketcheson Commented Feb 15, 2012 at 7:08

- 11 +1 for "consistently reading 5 pages per day adds up to a lot over time." To quote Benjamin Disraeli: "The secret of success is constancy of purpose." – Dan C Commented Aug 23, 2012 at 14:19

- 1 I'm doing this as well for the past few months. In addition, I'm keeping a track of what I read on my website and on citeulike, so that I can participate in discussions with the knowledge gained and cite papers when required to do so. – Naresh Commented Nov 20, 2012 at 3:31

9 Answers 9

My experience is almost exclusively with mathematics papers, and applies little or not at all to other fields.

Much of eykanal's post applies to math as well, but one big difference is that math papers are much more varied in their structure, not having an actual experiment to tie them together. A good paper will generally explain its organization in the introduction, however.

One point worth emphasizing is that reading a paper from front to back, trying to understand everything at each step, is usually inefficient. The most common instance is that a paper often starts with definitions which may be hard to make sense of without understanding the theorems they're used in. It's generally more effective to skim the paper several times, trying to understand more and more with each pass.

Relatedly, you'll eventually pick up the skill of picking out the most interesting ideas from a paper without reading the whole thing. Early on, though, it's probably better to read things carefully; it's very easy to fool yourself into thinking you've understood something.