The Science of Habit and Its Implications for Student Learning and Well-being

- Review Article

- Published: 17 March 2020

- Volume 32 , pages 603–625, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Logan Fiorella 1

11k Accesses

45 Citations

89 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Habits are critical for supporting (or hindering) long-term goal attainment, including outcomes related to student learning and well-being. Building good habits can make beneficial behaviors (studying, exercise, sleep, etc.) the default choice, bypassing the need for conscious deliberation or willpower and protecting against temptations. Yet educational research and practice tends to overlook the role of habits in student self-regulation, focusing instead on the role of motivation and metacognition in actively driving behavior. Habit theory may help explain ostensible failures of motivation or self-control in terms of contextual factors that perpetuate poor habits. Further, habit-based interventions may support durable changes in students’ recurring behaviors by disrupting cues that activate bad habits and creating supportive and stable contexts for beneficial ones. In turn, the unique features of educational settings provide a new area in which to test and adapt existing habit models.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The challenge of change: understanding the role of habits in university students’ self-regulated learning

Strategies and Interventions for Promoting Cognitive Engagement

The Triumph of Homework Completion: Instructional Approaches Promoting Self-regulation of Learning and Performance Among High School Learners

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

Ironically, one of the few articles on habits in Educational Psychology Review is an interview with the most productive educational psychologists, who cite consistent work habits as important for maintaining research productivity and work-life balance (Flanigan et al. 2018 ; see also Kiewra and Creswell 2000 ; Patterson-Hazley and Kiewra 2013 ). Accounts of writers, artists, musicians, and scientists concur that habits and ritual set the foundation for creativity and productivity (Currey 2013 , 2019 ).

The amount of repetition ultimately required to form a habit likely depends on the complexity of the habit (Mullan and Novoradovskaya 2018 ) and the suitability of the performance context (Wood 2019 ).

The term “study habits” is often defined broadly to include frequency of using various techniques, without specifying the nature or stability of specific context cues or the automaticity of the behavior. For example, Crede and Kuncel ( 2008 ) define study habits as “sound study routines, including but not restricted to, frequency of studying sessions, review of material, self-testing, rehearsal of learned material, and studying in a conductive environment” (p. 429).

Adriaanse, M. A., Kroese, F. M., Gillebaart, M., & De Ridder, D. T. D. (2014). Effortless inhibition: habit mediates the relation between self-control and healthy snack consumption. Frontiers in Psychology, 5 , 444.

Google Scholar

Alapin, I., Fitchen, C. S., Libman, E., Creti, L., Bailes, S., & Wright, J. (2000). How is good and poor sleep in older adults and college students related to daytime sleepiness, fatigue, and ability to concentrate? Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 49 (5), 381–390.

Anselme, P. (2013). Dopamine, motivation, and the evolutionary significance of gambling-like behavior. Behavioral Brain Research, 256 , 1–4.

Avni-Babad. (2011). Routine and feelings of safety, confidence, and well-being. The British Psychological Society, 102 , 223–244.

Babcock, P., & Marks, M. (2011). The falling cost of college: evidence from half a century of time use data. Review of Economics and Statistics, 93 (2), 468–478.

Bachman, R. (2017). How close do you need to be to your gym? The wall street journal. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-close-do-you-need-to-be-to-your-gym-1490111186 .

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., & Tice, D. M. (2007). The strength model of self-control. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16 , 351–355.

Bayer, J. B., & Larose, R. (2018). Technology habits: progress, problems, and prospects. In B. Verplanken (Ed.), The psychology of habit (pp. 111–130). Cham: Springer.

Bem, D. J. (1972). Self-perception theory. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 6 , 1–62.

Berry, T., Cook, L., Hills, N., & Stevens, K. (2010). An exploratory analysis of textbook usage and study habits: misperceptions and barriers to success. College Teaching, 59 (1), 31–39.

Bjork, R. A., Dunlosky, J., & Kornell, N. (2011). Self-regulated learning: beliefs, techniques, and illusions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64 , 417–444.

Blair, C., & Raver, C. C. (2015). School readiness and self-regulation: a developmental psychobiological approach. Annual Reviews of Psychology, 66 , 711–731.

Blasiman, R. N., Dunlosky, J., & Rawson, K. A. (2017). The what, how much, and when of study strategies: comparing intended versus actual study behaviour. Memory, 25 (6), 784–792.

Booker, L., & Mullan, B. (2012). Using the temporal self-regulation theory to examine the influence of environmental cues on maintaining a healthy lifestyle. British Journal of Health Psychology, 18 (4), 745–762.

Breslow, L., Pritchard, D. E., DeBoer, J., Stump, G. S., Ho, A. D., & Seaton, D. T. (2013). Studying learning in the worldwide classroom: research into edX’s first MOOC. Research & Practice in Assessment, 8 , 13–25.

Bui, D. C., Myerson, J., & Hale, S. (2013). Note-taking with computers: exploring alternative strategies for improved recall. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105 (2), 299–309.

Carden, L., & Wood, W. (2018). Habit formation and change. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 20 , 117–122.

Carden, L., Wood, W., Neal, D. T., & Pascoe, A. (2017). Incentives activate a control mind-set: good for deliberate behaviors, bad for habit performance. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 2 (3), 279–290.

Crede, M., & Kuncel, N. R. (2008). Study habits, skills, and attitudes. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3 (6), 425–453.

Currey, M. (2013). Daily rituals: how artists work . New York: Knopf.

Currey, M. (2019). Daily rituals: women at work . New York: Knopf.

Danner, U. N., Aarts, H., & de Vries, N. K. (2008). Habit vs. intention in the prediction of future behavior: the role of frequency, context stability and mental accessibility of past behavior. British Journal of Social Psychology, 47 (2), 245–265.

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (2001). Extrinsic rewards and intrinsic motivation in education: reconsidered once again. Review of Educational Research, 71 , 1–27.

Dewald, J. F., Meijer, A. M., Oort, F. J., Kerkhof, G. A., & Bogels, S. M. (2010). The influence of sleep quality, sleep duration and sleepiness on school performance in children and adolescents: a meta-analytic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 14 , 179–189.

Dickinson, A. (1985). Actions and habits: the development of behavioural automaticity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. B, Biological Sciences, 308 (1135), 67–78.

Diekelmann, S., Wilhelm, I., & Born, J. (2009). The whats and whens of sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 13 (5), 309–321.

Dillard, A. (1989). The writing life . New York City: Harper Collins Publishers, Inc.

Donker, A. S., De Boer, H., Kostons, D., van Ewijk, C. D., & Van der Werf, M. P. C. (2014). Effectiveness of learning strategy instruction on academic performance: a meta- analysis. Educational Research Review, 11 , 1–26.

Duckworth, A. L., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2005). Self-discipline outdoes IQ in predicting academic performance of adolescents. Psychological Science, 16 (12), 939–944.

Duckworth, A. L., Gendler, T. L., & Gross, J. J. (2014). Self-control in school-aged children. Educational Psychologist, 49 , 199–217.

Duckworth, A. L., Gendler, T. L., & Gross, J. J. (2016a). Situational strategies for self-control. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11 (1), 35–55.

Duckworth, A. L., White, R. E., Matteucci, A. J., Shearer, A., & Gross, J. J. (2016b). A stitch in time: strategic self-control in high school and college students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108 (3), 329–341.

Duckworth, A. L., Taxer, J. L., Eskreis-Winkler, L., Galla, B. M., & Gross, J. J. (2019). Self-control and academic achievement. Annual Review of Psychology, 70 , 373–399.

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques: promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14 (1), 4–58.

Englert, C., Zavery, A., & Bertrams, A. (2017). Too exhausted to perform at the highest level? On the importance of self-control strength in educational settings. Frontiers in Psychology, 8 , 1290.

Evans, J., & Stanovich, K. E. (2013). Dual process theories of higher cognition: advancing the debate. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8 (3), 223–241.

Eyal, N. (2014). Hooked: how to build habit-forming products . Penguin.

Fiorella, L., & Mayer, R. E. (2015). Learning as a generative activity: eight learning strategies that promote understanding . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Fiorella, L., & Mayer, R. E. (2016). Eight ways to promote generative learning. Educational Psychology Review, 28 (4), 717–741.

Fiorella, L., & Mayer, R. E. (2017). Spontaneous spatial strategy use in learning from scientific text. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 49 , 66–79.

Fiorella, L., & Mayer, R. E. (2018). What works and doesn’t work with instructional video. Computers in Human Behavior, 89 , 465–470.

Flanigan, A. E., Kiewra, K., & Luo, L. (2018). Conversations with four highly productive German educational psychologists: Frank Fischer, Hans Gruber, Heinz Mandl, and Alexander Renkl. Educational Psychology Review, 30 , 303–330.

Fries, S., Dietz, F., & Schmid, S. (2008). Motivational interference in learning: the impact of leisure alternatives on subsequent self-regulation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 33 , 119–133.

Galla, B. M., & Duckworth, A. L. (2015). More than resisting temptation: beneficial habits mediate the relationship between self-control and positive life outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109 (3), 508–525.

Galla, B. M., Shulman, E. P., Plummer, B. D., Gardner, M., Hutt, S. J., Goyer, J. P., ... & Duckworth, A. L. (2019). Why high school grades are better predictors of on-time college graduation than are admissions test scores: the roles of self-regulation and cognitive ability. American Educational Research Journal, 56 (6), 2077–2115.

Galvon, A. (2020). The need for sleep in the adolescent brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 24 (1), 79–89.

Gardner, B., & Lally, P. (2013). Does intrinsic motivation strengthen physical activity habit? Modeling relationships between self-determinism, past behavior, and habit strength. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 36 , 488–499.

Gillan, C. M., Otto, A. R., Phelps, E. A., & Daw, N. D. (2015). Model-based learning protects against forming habits. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 15 (3), 523–536.

Gillebaart, M., & Adriaanse, M. A. (2017). Self-control predicts exercise behavior by force of habit, a conceptual replication of Adriaanse et al. (2014). Frontiers in Psychology, 8 , 190.

Grave, B. S. (2011). The effect of student time allocation on academic achievement. Education Economics, 19 (3), 291–319.

Greene, J. A., & Azevedo, R. (2010). The measurement of learners’ self-regulated cognitive and metacognitive processes while using computer-based learning environments. Educational Psychologist, 45 , 203–209.

Gruber, R. (2017). School-based sleep education programs: a knowledge-to-action perspective regarding barriers, proposed solutions, and future directions. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 36 , 13–28.

Grund, A., Grunschel, C., Bruhn, D., & Fries, S. (2015a). Torn between want and should: an experience-sampling study on motivational conflict, well-being, self-control, and mindfulness. Motivation and Emotion, 39 , 506–520.

Grund, A., Schmid, S., & Fries, S. (2015b). Studying against your will: motivational interference in action. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41 , 209–217.

Hagger, M. S., Wood, C., Stiff, C., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. D. (2010). Ego depletion and the strength model of self-control: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136 (4), 495–525.

Hallal, P. C., Anderson, L. B., Bull, F. C., Guthold, R., Haskell, W., Ekelund, U., & Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. (2012). Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, gaps and prospects. The Lancet, 380 (9838), 247–257.

Harastzi, R. A., Ella, K., Gyongyosi, N., Roenneberg, T., & Kaldi, K. (2014). Social jetlag negatively correlates with academic performance in undergraduates. Chronobiology International, 31 (5), 603–612.

Harrison, Y., & Horne, J. A. (2000). The impact of sleep deprivation on decision making: a review. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 6 (3), 236–249.

Heatherton, T. F., & Nichols, P. A. (1994). Personal accounts of successful versus failed attempts at life change. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20 (6), 664–675.

Henderikx, M. A., Kreijns, K., & Kalz, M. (2017). Refining success and dropout in massive online courses based on the intention-behavior gap. Distance Education, 38 (3), 353–368.

Hirshkowitz, M., Whiton, K., Albert, S. M., Alessi, C., Burni, O., DonCarlos, L., et al. (2015). National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep Health, 1 (1), 40–43.

Hofmann, W., Baumeister, R. F., Forster, G., & Vohs, K. D. (2012). Everyday temptations: an experience sampling study of desire, conflict, and self-control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102 (6), 1318–1335.

Holland, R. W., Aarts, H., & Langendam, D. (2006). Breaking and creating habits on the working floor: a field experiment on the power of implementation intentions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42 (6), 776–783.

Howard-Jones, P. A., & Jay, T. (2016). Reward, learning and games. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 10 , 65–72.

James, W. (1890). Principles of psychology . New York: Holt.

James, W. (1899). Talks to teachers . New York: Holt.

Ji, M. F., & Wood, W. (2007). Purchase and consumption habits: not necessarily what you intend. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17 (4), 261–276.

Judah, G., Gardner, B., & Aunger, R. (2013). Forming a flossing habit: an exploratory study of the psychological determinants of habit formation. British Journal of Health Psychology, 18 (2), 338–353.

Kane, M. J., Smeekens, B. A., von Basian, C. C., Lurquin, J. H., Carruth, N. P., & Miyake, A. (2017). A combined experimental and individual-differences investigation into mind wandering during a video lecture. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 146 (11), 1649–1674.

Kaushal, N., & Rhodes, R. E. (2015). Exercise habit formation in new gym members: A longitudinal study. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 38 , 652–663.

Kaushal, N., Rhodes, R. E., Spence, J. C., & Meldrum, J. T. (2017). Increasing physical activity through principles of habit formation in new gym members: a randomized controlled trial. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 51 (4), 578–586.

Kiewra, K. A., & Creswell, J. W. (2000). Conversations with three highly productive educational psychologists: Richard Anderson, Richard Mayer, and Michael Pressley. Educational Psychology Review, 12 (1), 135–161.

Killingsworth, M. A., & Gilbert, D. T. (2010). A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science, 330 (6006), 932–932.

Kim, K. R., & Seo, E. H. (2015). The relationship between procrastination and academic performance: a meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 82 , 26–33.

Kocken, P. L., Eeuwijk, J., Van Kesteren, N. M., Dusseldorp, E., Buijs, G., Bassa-Dafesh, Z., & Snel, J. (2012). Promoting the purchase of low-calorie foods from school vending machines: a cluster-randomized control study. Journal of School Health, 82 (3), 115–122.

Lally, P., & Gardner, B. (2013). Promoting habit formation. Health Psychology Review, 7 (1), S137–S158.

Lally, P., Van Jaarsveld, C. H. M., Potts, H. W. W., & Wardle, J. (2010). How are habits formed: modeling habit formation in the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40 , 998–1009.

Lepper, M. R., & Greene, D. (Eds.). (1978). The hidden costs of reward . New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc..

Lim, J., & Dinges, D. F. (2010). A meta-analysis of the impact of short-term sleep deprivation on cognitive variables. Psychological Bulletin, 136 (3), 375–389.

Loh, K. K., Tan, B. Z. H., & Lim, S. W. H. (2016). Media multitasking predicts video-recorded lecture learning performance through mind wandering tendencies. Computers in Human Behavior, 63 , 943–947.

Manalo, E., Uesaka, Y., & Chinn, C. A. (Eds.). (2018). Promoting spontaneous use of learning and reasoning strategies . New York: Routledge.

Marteau, T. M., Hollands, G. J., & Fletcher, P. C. (2012). Changing human behavior to prevent disease: the importance of targeting automatic processes. Science, 337 (6101), 1492–1495.

Mazar, A., & Wood, W. (2018). Defining habit in psychology. In Verplanken (Ed.), Psychology of habit (pp. 13–30). Cham: Springer.

Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., Bakia, M., & Jones, K. (2009). Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning: a meta-analysis and review of online-learning studies . Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education.

Mega, C., Ronconi, L., & De Beni, R. (2014). What makes a good student? How emotions, self- regulated learning, and motivation contribute to academic achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106 (1), 121–131.

Milkman, K. L., Minson, J. A., & Volpp, K. G. (2014). Holding the hunger games hostage at the gym: an evaluation of temptation bundling. Management Science, 60 (2), 283–299.

Milyavskaya, M., & Inzlicht, M. (2017). What’s so great about self-control? Examining the importance of effortful self-control and temptation in predicting real-life depletion and goal attainment. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8 (6), 603–611.

Morehead, K., Dunlosky, J., & Rawson, K. A. (2019). How much mightier is the pen than the keyboard for note-taking? A replication and extension of Mueller and Oppenheimer (2014). Educational Psychology Review, 31 , 753–780.

Mueller, P. A., & Oppenheimer, D. M. (2014). The pen is mightier than the keyboard: advantages of longhand over laptop note taking. Psychological Science, 25 (6), 1159–1168.

Mullan, B., & Novoradovskaya, E. (2018). Habit mechanisms and behavioral complexity. In B. Verplanken (Ed.), The psychology of habit (pp. 71–90). Cham: Springer.

Neal, D. T., Wood, W., Wu, M., & Kurlander, D. (2011). The pull of the past: when do habits persist despite conflict with motives? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37 (11), 1428–1437.

Neal, D. T., Wood, W., Labrecque, J. S., & Lally, P. (2012). How do habits guide behavior? Perceived and actual triggers of habits in daily life. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48 , 492–498.

Neal, D. T., Wood, W., & Drolet, A. (2013). How do people adhere to goals when willpower is low? The profits (and pitfalls) of strong habits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104 (6), 959–975.

Neroni, J., Meijs, C., Gijselears, H. J. M., Kirschner, P. A., & de Groot, R. H. M. (2019). Learning strategies and academic performance in distance education. Learning and Individual Differences, 73 , 1–7.

Norris, E., van Steen, T., Direito, A., & Stamatakis, E. (2019). Physically active lessons in schools and their impact on physical activity, educational, health and cognition outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine . Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-100502 .

Oaten, M., & Cheng, K. (2005). Academic examination stress impairs self-control. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 24 , 254–279.

Okano, K., Kaczmarzyk, J. R., Dave, N., Gabrieli, J. D. E., & Grossman, J. C. (2019). Sleep quality, duration, and consistency are associated with better academic performance in college students. NPJ Science of Learning, 4 (1), 1–5.

Orzech, K. M., Salafsky, D. B., & Hamilton, L. A. (2011). The state of sleep among college students at a large public university. Journal of American College Health, 59 (7), 612–619.

Ouellette, J. A., & Wood, W. (1998). Habit and intention in everyday life: the multiple processes by which past behavior predicts future behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 124 (1), 54–74.

Patterson-Hazley, M., & Kiewra, K. A. (2013). Conversations with four highly productive educational psychologists: Patricia Alexander, Richard Mayer, Dale Schunk, & Barry Zimmerman. Educational Psychology Review, 25 (1), 19–45.

Pew Research Center. (2018). How teens and parents navigate screen time and device distractions . Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2018/08/22/how-teens-and-parents-navigate-screen-time-and-device-distractions/ .

Pintrich, P. R. (2004). A conceptual framework for assessing student motivation and self- regulated learning in college students. Educational Psychology Review, 16 , 385–407.

Quinn, J. M., Pascoe, A., Wood, W., & Neal, D. T. (2010). Can’t control yourself? Monitor those bad habits. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36 (4), 499–511.

Ravizza, S. M., Uitvlugt, M. G., & Fenn, K. M. (2017). Logged in and zoned out: how laptop internet use relates to classroom learning. Psychological Science, 28 (2), 171–180.

Rebar, A. L., Gardner, B., Rhodes, R. E., & Verplanken, B. (2018). The measurement of habit. In B. Verplanken (Ed.), The psychology of habit (pp. 31–50). Cham: Springer.

Reed, J. A., & Phillips, D. A. (2005). Relationships between physical activity and the proximity of exercise facilities and home exercise equipment used by undergraduate university students. Journal of American College Health, 53 (6), 285–290.

Rey, A. E., Guignard-Perret, A., Imler-Weber, F., Garcia-Larrea, L., & Mazza, S. (2020). Improving sleep, cognitive functioning and academic performance with sleep education at school in children. Learning and Instruction, 65 , 101270.

Roberts, J. A., Yaya, L. H. P., & Manolis, C. (2014). The invisible addiction: cell-phone activities and addiction among male and female college students. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 3 (4), 254–265.

Rompotis, C. J., Grove, J. R., & Byrne, S. M. (2014). Benefits of habit-based informational interventions: a randomized controlled trial of fruit and vegetable consumption. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 38 (3), 247–252.

Rothman, A. J., Gollwitzer, P. M., Grant, A. M., Neal, D. T., Sheeran, P., & Wood, W. (2015). Hale and hearty policies: how psychological science can create and maintain healthy habits. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10 (6), 701–705.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55 (1), 68–78.

Sappington, J., Kinsey, K., & Munsayac, K. (2002). Two studies of reading compliance among college students. Teaching of Psychology, 29 (4), 272–274.

Schneider, B. (2013). Sloan study of youth and social development, 1992-1997 [United States]. ICPSR04551-v2 (pp. 10–22). Ann Arbor: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor].

Schunk, D. H., & Greene, J. A. (2017). Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Shankland, R., & Rosset, E. (2017). Review of brief school-based positive psychological interventions: a taster for teachers and educators. Educational Psychology Review , 363–392.

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms . New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Solomon, L. J., & Rothblum, E. D. (1984). Academic procrastination: frequency and cognitive- behavioral correlates. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 31 (4), 503–509.

Stojanovic, M., Grund, A., & Fries, S. (2020). App-based habit building reduces motivational impairments during studying - An event sampling study. Froniers in Psychology, 11 (167), 1–15.

Susser, J. A., & McCabe, J. (2013). From the lab to the dorm room: metacognitive awareness and use of spaced study. Instructional Science, 41 , 345–363.

Sweller, J., Ayres, P., & Kalyuga, S. (2011). Cognitive load theory . New York: Springer.

Tappe, K., Tarves, E., Oltarzewski, J., & Frum, D. (2013). Habit formation among regular exercisers at fitness centers: an exploratory study. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 10 (4), 607–613.

Taraban, R., Maki, W. S., & Rynerson, K. (1999). Measuring study time distributions: implications for designing computer-based courses. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 31 (2), 263–369.

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2009). Nudge: improve decisions about health, wealth, and happiness . New York: Penguin.

Thorndike, E. L. (1906). The principles of teaching based on psychology . Syracuse: Mason- Henry Press.

Thorndike, A. N., Sonnenberg, L., Riis, J., Barraclough, S., & Levy, D. E. (2012). A 2-phase labeling and choice architecture intervention to improve health food and beverage choices. American Journal of Public Health, 102 (3), 527–533.

Tindell, D. R., & Bohlander, R. W. (2012). The use and abuse of cell phones and text messaging in the classroom: a survey of college students. College Teaching, 60 (1), 1–9.

Tokunaga, R. S. (2017). A meta-analysis of the relationships between psychosocial problems and internet habits: synthesizing internet addiction, problematic internet use, and deficient self-regulation research. Communication Monographs, 84 (4), 423–446.

Tricomi, E., Balleine, B. W., & O’Doherty, J. P. (2009). A specific role for posterior dorsolateral striatum in human habit learning. European Journal of Neuroscience, 29 (11), 2225–2232.

Verplanken, B. (2006). Beyond frequency: habit as a mental construct. British Journal of Social Psychology, 45 , 639–656.

Verplanken, B. (Ed.). (2018). The psychology of habit . Cham: Springer.

Verplanken, B., & Orbell, S. (2003). Reflections on past behavior: a self-report index of habit strength. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33 (6), 1313–1330.

Verplanken, B., & Roy. (2016). Empowering interventions to promote sustainable lifestyles: testing the habit discontinuity hypothesis. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 45 , 127–134.

Verplanken, B., Aarts, H., van Kippenberg, A., & Moonen, A. (1998). Habit versus planned behavior: a field experiment. British Journal of Social Psychology, 37 , 111–128.

Vettese, L. C., Toneatto, T., Stea, J. N., Nguyen, L., & Wang, J. J. (2009). Do mindfulness meditation participants do their homework? And does it make a difference? A review of the empirical evidence. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 23 (3), 198–225.

Wahlstrom, K., Dretzke, B., Gordon, M., Peterson, K., Edwards, K., & Gdula, J. (2014). Examining the impact of later school start times on the health and academic performance of high school students: a multi-site study. Center for Applied Research and Educational Improvement . St Paul: University of Minnesota.

Walker, M. P., & Stickgold, R. (2006). Sleep, memory, and plasticity. Annual Reviews of Psychology, 57 , 139–166.

Waters, L., Barsky, A., Ridd, A., & Allen, K. (2015). Contemplative education: a systematic, evidence-based review of the effect of meditation interventions in schools. Educational Psychology Review, 27 (1), 103–134.

Webb, T. L., & Sheeran, P. (2006). Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 132 (2), 249–268.

Williamson, L. Z., & Wilkowski, B. M. (2019). Nipping temptation in the bud: examining strategic self-control in daily life. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin . Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167219883606 .

Wilmer, H. H., Sherman, L. E., & Chein, J. M. (2017). Smartphones and cognition: a review of research exploring the links between mobile technology habits and cognitive functioning. Frontiers in Psychology, 8 (605).

Winne, P. H., & Hadwin, A. F. (1998). Studying as self-regulated learning. In D. J. Hacker, J. Dunlosky, & A. C. Graesse (Eds.), Metacognition in educational theory and practice (pp. 277–304). Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Wong, M. L., Lau, E. Y. Y., Wan, J. H. Y., Cheung, S. F., Hui, C. H., & Mok, D. S. Y. (2013). The interplay between sleep and mood in predicting academic functioning, physical health and psychological health: a longitudinal study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 74 (4), 271–277.

Wood, W. (2017). Habit in personality and social psychology. Personality and Social Psychology, 21 (4), 389–403.

Wood, W. (2019). Good habits, bad habits . New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

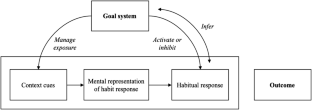

Wood, W., & Neal, D. T. (2007). A new look at habits and the habit-goal interface. Psychological Review, 114 (4), 843–863.

Wood, W., & Neal, D. T. (2016). Health through habit: interventions for initiating and maintaining health behavior change. Behavioral Science & Policy, 2 (1), 71–83.

Wood, W., & Runger, D. (2016). Psychology of habit. Annual Reviews of Psychology, 67 , 289–314.

Wood, W., Quinn, J. M., & Kashy, D. A. (2002). Habits in everyday life: thought, emotion, and action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83 (6), 1281–1297.

Wood, W., Tam, L., & Witt, M. G. (2005). Changing circumstances, disrupting habits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88 (6), 918–933.

Zedelius, C. M., Gross, M. E., & Schooler, J. W. (2018). Mind wandering: more than a bad habit. In B. Verplanken (Ed.), The psychology of habit (pp. 363–378). Cham: Springer.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: a social cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation: theory, research, and applications (pp. 13–39).

Zou, Q., Main, A., & Wang, Y. (2010). The relations of temperamental effortful control and anger/frustration to Chinese children’s academic achievement and social adjustment: a longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102 , 180–196.

Download references

Acknowledgments

I thank Wendy Wood and one anonymous reviewer for their constuctive feedback and suggestions. I also thank Deborah Barany, Qian Zhang, and Michele Lease for their helpful comments on an earlier draft of this article. Finally, I thank the students from my First Year Odyssey Seminar at the University of Georgia, Applying the Science of Habit, for their valuable insight into the role of habits in their lives.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Educational Psychology, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, 30605, USA

Logan Fiorella

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Logan Fiorella .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Fiorella, L. The Science of Habit and Its Implications for Student Learning and Well-being. Educ Psychol Rev 32 , 603–625 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09525-1

Download citation

Published : 17 March 2020

Issue Date : September 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09525-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Self-regulation

- Self-control

- Study habits

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- DOI: 10.31305/rrijm.2021.v06.i05.019

- Corpus ID: 242541756

Study Habits and Academic Performance among Students: A Systematic Review

- Published in RESEARCH REVIEW International… 15 June 2021

- Education, Psychology

2 Citations

Study habits and academic performance among public junior high school pupils in the ekumfi district: investigating the controlling effect of learning styles, analysis of learning and academic performance of education students before and during the coronavirus disease pandemic, 32 references, factors affecting the student’s study habit, study habits, skills, and attitudes: the third pillar supporting collegiate academic performance, relationship among self-concept , study habits and academic achievement of prence students in zamfara state college of education , nigeria, influence of study habits on the academic performance of physics students in federal university of agriculture makurdi, nigeria, academic stress and self efficacy in relation to study habits among adolescents, a handbook of educational technology, handbook of college reading and study strategy research, impact of family climate, mental health, study habits and self confidence on the academic achievement of senior secondary students, influence of study habits on academic achievement of senior secondary school students in relation to gender and community, a study of emotional intelligence school adjustment and study habits of secondary school students in relation to their academic achievement in social science, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

A Study on Study Habits and Academic Performance of Students

- January 2017

- 7(10):891-897

- Quaid-i-Azam University

- Govt. College Women University Sialkot

- Government College Women University, Sialkot

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- O O Akinnubi

- Jumoke Iyabode Oladele

- Catherine Palmer

- Shane O'Rourke

- Jeniffer O. Birech

- Pamela Awuor Onyango

- Maliha Kanwal

- Sadaf Abbasi

- Sidra Kiran

- Piyali Debnath

- Mulikat Bola Aliyu

- Herbert C. Richards

- Dana C. Sheridan

- Donald R. Gallo

- Rachael Deavers

- Sue Kerfoot

- J T Guthrie

- S Higginbotham

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Six research-tested ways to study better

Psychology’s latest insights for preparing students for their next exams.

- Learning and Memory

Many students are missing a lesson in a key area that can help guarantee their success: how to study effectively.

It’s common for students to prepare for exams by re-reading class notes and cramming textbook chapters—study techniques that hinge on the assumption that memories are like recording devices that can play back memories during an exam. “But the storage and retrieval operations of human memory differ from recording devices in almost every way possible,” says psychology professor Robert Bjork, PhD, co-director of the Learning and Forgetting Lab at University of California, Los Angeles.

What does help our brains retain information? Study strategies that require the brain to work to remember information—rather than passively reviewing material.

Bjork coined the term “desirable difficulty” to describe this concept, and psychologists are homing in on exactly how students can develop techniques to maximize the cognitive benefits of their study time.

Here are six research-tested strategies from psychology educators.

1. Remember and repeat

Study methods that involve remembering information more than once—known as repeated retrieval practice—are ideal because each time a memory is recovered, it becomes more accessible in the future, explains Jeffrey Karpicke, PhD, a psychology researcher at Purdue University in Indiana who studies human learning and memory.

The benefits of this technique were evident when Karpicke conducted a study in which students attempted to learn a list of foreign language words. Participants learned the words in one of four ways:

- Studying the list once.

- Studying until they had successfully recalled each word once.

- Studying until they had successfully recalled each word three times consecutively.

- Studying until they had recalled each word three times spaced throughout the 30-minute learning session.

In the last condition, the students would move on to other words after correctly recalling a word once, then recall it again after practicing other words.

A week later, the researchers tested the students on the words and discovered that participants who had practiced with repeated spaced retrieval—the last condition—far outperformed the other groups. Students in this group remembered 80% of the words, compared to 30% for those who had recalled the information three times in a row—known as massed retrieval practice—or once. The first group, which involved no recall, remembered the words less than 1% of the time ( Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition , Vol. 37, No. 5, 2011).

Many students assume that recalling something they’ve learned once is proof that they’ve memorized it. But, says Karpicke, just because you can retrieve a fact in a study session doesn’t mean you will remember it later on a test. “Just a few repeated retrievals can produce significant effects, and it’s best to do this in a spaced fashion.”

2. Adapt your favorite strategies

Other research finds support for online flashcard programs, such as Study Stack or Chegg, to practice retrieving information—as long as students continue retesting themselves in the days leading up to the test, says John Dunlosky, PhD, who studies self-regulated learning at Kent State University in Ohio. For flashcards with single-word answers, the evidence suggests that thinking of the answer is effective, but for longer responses like definitions, students should type, write down, or say aloud the answers, Dunlosky says. If the answer is incorrect, then study the correct one and practice again later in the study session. “They should continue doing that until they are correct, and then repeat the process in a couple more days,” he says.

Concept mapping — a diagram that depicts relationships between concepts—is another well-known learning technique that has become popular, but cognitive psychology researchers caution students to use this strategy only if they try to create a map with the book closed. Karpicke demonstrated this in a study in which students studied topics by creating concept maps or by writing notes in two different conditions: with an open textbook or with the textbook closed. With the closed textbook, they were recalling as much as they could remember. One week later, the students took an exam that tested their knowledge of the material, and students who had practiced retrieving the information with the book closed had better performances ( Journal of Educational Psychology , Vol. 106, No. 3, 2014).

“Concept maps can be useful, as long as students engage in retrieval practice while using this strategy,” Karpicke says.

3. Quiz yourself

Students should also take advantage of quizzes—from teachers, in textbooks or apps like Quizlet—to refine their ability to retain and recall information. It works even if students answer incorrectly on these quizzes, says Oregon State University psychology professor Regan Gurung, PhD. “Even the process of trying and failing is better than not trying at all,” he says. “Just attempting to retrieve something helps you solidify it in your memory.”

Gurung investigated different approaches to using quizzes in nine introductory psychology courses throughout the country. In the study, the researchers worked with instructors who agreed to participate in different conditions. Some required students to complete chapter quizzes once while others required them to take each quiz multiple times. Also, some students were told to complete all the chapter quizzes by one deadline before the exam, while others were expected to space their quizzes by meeting deadlines throughout the course. The students who spaced their quizzes and took them multiple times fared the best on the class exams ( Applied Cognitive Psychology , Vol. 33, No. 5, 2019).

Although trying and failing on practice quizzes may be an effective study strategy, psychology professor Nate Kornell, PhD, of Williams College in Massachusetts, was skeptical that students would choose to learn this way because many people inherently do not like getting things wrong. He was eager to explore whether it was possible to create a retrieval practice strategy that increased the odds of students getting the right answer without sacrificing the quality of learning. To test this possibility, he led a study in which participants tried to remember word pairs, such as “idea: seeker.” The goal was to remember the second word after seeing only the first one. The students could choose to practice by restudying all the pairs or by self-testing with different options for hints—seeing either two or four letters of the second word in the pair, or no letters at all ( Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications , Vol. 4, 2019).

Most of the students preferred self-testing over restudying, and the results showed that even with hints, the self-testing group performed better on the final test of the words than the restudying group. “It’s a win-win situation because the technique that worked most effectively was also the one that they enjoyed the most,” says Kornell.

Even more important, students think they are learning more effectively when they answer correctly while practicing, which means they’ll be even more motivated to try retrieval practice if hints are available, says Kornell. To apply this strategy, he suggests adding hints to self-generated flash cards or quizzes, such as the first letter of the answer or one of the words in a definition.

4. Make the most of study groups

Many students also enjoy studying with classmates. But when working in groups, it’s important for students to let everyone have an opportunity to think of the answers independently, says Henry Roediger, III, PhD, a professor in the psychology department at Washington University in St. Louis. One study highlighted the importance of this: Participants tried to learn words in a foreign language by either answering aloud or by listening to their partners give the answers ( Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied (PDF, 426KB) , Vol. 24, No. 3, 2018). As expected, those who had answered aloud outperformed the listeners on a test two days later. The researchers also compared participants who answered aloud with partners who silently tried to recall the answers. Everyone received feedback about whether they had gotten the correct answer. Both groups had comparable performances. “Waiting for others to think of answers may slow down the process, but it produces better retention for everyone because it requires individual effort,” Roediger says.

5. Mix it up

Researchers have also investigated the potential benefits of “interleaving,” or studying for different courses in one study session ( Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied , Vol. 23, Nov. 4, 2017). For example, rather than dedicating two hours to studying for a psychology exam, students could use that time to study for exams in psychology, biology and statistics courses. A few days later, students could study for the same courses again during another block of time. “This strategy, versus blocking one’s study by course, naturally introduces spacing, so students practice retrieving information over time,” Bjork says.

But the research on interleaving has had mixed results, says Aaron Richmond, PhD, a professor of educational psychology and human development at Metropolitan State University in Denver. “If the concepts from two subjects overlap too closely, then this could interfere with learning,” says Richmond. “But chemistry and introduction to psychology are so different that this doesn’t create interference.”

6. Figure out what works for you

The ability to effectively evaluate one’s approach to learning and level of attainment is known as metacognitive ability. Research has shown that “when people are new to learning about a topic, their subjective impressions of how much they know are the most inflated,” says Paul Penn, PhD, a senior lecturer in the psychology department at East London University and author of the 2019 book “The Psychology of Effective Studying.”

“If your impression of your learning is inflated, you have little incentive to look at the way you're approaching learning,” he says.

To increase awareness about the value of sound study strategies, administrators at Samford University in Alabama invited psychology professor Stephen Chew, PhD, to talk to first-year students about this topic during an annual convocation each fall semester. Though an assessment study, he realized that the lecture prompted immediate changes in beliefs and attitudes about studying, but long-term change was lacking. “Students forgot the specifics of the lecture and fell back into old habits under the stress of the semester,” Chew says.

To provide an accessible resource, he launched a series of five 7-minute videos on the common misconceptions about studying, how to optimize learning and more. Professors throughout the school assign the videos as required classwork, and the videos have been viewed 3 million times throughout the world by high school, college and medical students.

While this form of campus-wide education about studying is somewhat rare, psychology researchers are optimistic that this could become more common in the coming years. “There is a lot more discussion now than even 10 years ago among teachers about the science of learning,” Karpicke says. “Most students do not know how to study effectively, and teachers are increasingly eager to change that.”

Further reading

- Improving Self-Regulated Learning with a Retrieval Practice Intervention. Ariel, R., Karpicke, J.D., Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied , 2018.

- Practice Tests, Spaced Practice, and Successive Relearning: Tips for Classroom Use and for Guiding Students’ Learning (PDF, 53KB) . Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology , Dunlosky, J. & Rawson, K.A., 2015.

- Performance Bias: Why Judgments of Learning Are not Affected by Learning . Kornell, N. and Hausman, H., Memory & Cognition , 2017.

Recommended Reading

Contact education, you may also like.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Forget What You Know About Good Study Habits

By Benedict Carey

- Sept. 6, 2010

Every September, millions of parents try a kind of psychological witchcraft, to transform their summer-glazed campers into fall students, their video-bugs into bookworms. Advice is cheap and all too familiar: Clear a quiet work space. Stick to a homework schedule. Set goals. Set boundaries. Do not bribe (except in emergencies).

And check out the classroom. Does Junior’s learning style match the new teacher’s approach? Or the school’s philosophy? Maybe the child isn’t “a good fit” for the school.

Such theories have developed in part because of sketchy education research that doesn’t offer clear guidance. Student traits and teaching styles surely interact; so do personalities and at-home rules. The trouble is, no one can predict how.

Yet there are effective approaches to learning, at least for those who are motivated. In recent years, cognitive scientists have shown that a few simple techniques can reliably improve what matters most: how much a student learns from studying.

The findings can help anyone, from a fourth grader doing long division to a retiree taking on a new language. But they directly contradict much of the common wisdom about good study habits, and they have not caught on.

For instance, instead of sticking to one study location, simply alternating the room where a person studies improves retention. So does studying distinct but related skills or concepts in one sitting, rather than focusing intensely on a single thing.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

Developing Good Study Habits Really Works

Effective study habits really do work..

Posted February 27, 2012

- What Is a Career

- Take our Procrastination Test

- Find a career counselor near me

Knowledge is the essence of smart thinking. No matter how much raw intelligence you have, you are not going to succeed at solving complex problems without knowing a lot. That's why we spend the first 20 (or more) years of our lives in school.

Robert Bjork and fellow PT blogger Nate Kornell have explored some of the study habits of college students in a 2007 paper in Psychonomic Bulletin & Review . Research on memory provides a number of important suggestions about the most effective ways to study. One of the most important tips is that students should study by testing themselves rather than just reading over the material. It is also important to study over a period of days rather waiting until the last minute to study. Kornell and Bjork's studies suggest that only about 2/3 of college students routinely quiz themselves, and a majority of students study only one time for upcoming exams.

Of course, guidelines from memory research come from studies in idealized circumstances. Researchers bring participants (many of whom are college students) into a lab and ask them to learn material. Perhaps the recommendations drawn from these studies are not that helpful for real students dealing with real courses.

To address this question, Marissa Hartwig and John Dunlosky related the study habits of college students to their grade point average (GPA) in a 2012 paper in Psychonomic Bulletin & Review . They asked students about a number of study behaviors. They also had students report their current GPA.

The students with the highest GPA were more likely to study by testing themselves than the students with lower GPAs. What is the most effective way to test yourself, though? It turns out that most students report using flashcards, and the use of flashcards does not predict a student's grades. However, flash cards usually allow people to learn basic aspects of a domain like key vocabulary. Really understanding something new requires practice with explaining it. So, self-testing needs to involve deeper questions than the ones that are usually written on flash cards.

All college students tend to focus their study on upcoming assignments. That is no surprise, because college is a busy time. The most successful students, though, also schedule time to study for classes even before the exam is coming up. The students who make a schedule and stick with it tend to get better grades than those who just work on whatever is coming up.

Finally, the time of day that students study also matters. College students are notorious night owls. Indeed, few students reported studying in the morning, or even in the afternoon. Most students study in the evening and late at night. One of the interesting results of this research, though, is that the students who study late at night tend to get worse grades than those who study in the evening.

It is always nice when studies of real-world behavior mesh with recommendations from basic research. In the case of studying, though, it seems particularly important to ensure that basic research influences behavior. People invest several years and thousands of dollars in a college education . That education has an enormous effect on their future productivity . Cognitive science can ensure that students maximize the value of that experience.

Follow me on Twitter

And on Facebook

Check out my book Smart Thinking (Perigee Books)

Art Markman, Ph.D. , is a cognitive scientist at the University of Texas whose research spans a range of topics in the way people think.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Celebrating 150 years of Harvard Summer School. Learn about our history.

Top 10 Study Tips to Study Like a Harvard Student

Adjusting to a demanding college workload might be a challenge, but these 10 study tips can help you stay prepared and focused.

Lian Parsons

The introduction to a new college curriculum can seem overwhelming, but optimizing your study habits can boost your confidence and success both in and out of the classroom.

Transitioning from high school to the rigor of college studies can be overwhelming for many students, and finding the best way to study with a new course load can seem like a daunting process.

Effective study methods work because they engage multiple ways of learning. As Jessie Schwab, psychologist and preceptor at the Harvard College Writing Program, points out, we tend to misjudge our own learning. Being able to recite memorized information is not the same as actually retaining it.

“One thing we know from decades of cognitive science research is that learners are often bad judges of their own learning,” says Schwab. “Memorization seems like learning, but in reality, we probably haven’t deeply processed that information enough for us to remember it days—or even hours—later.”

Planning ahead and finding support along the way are essential to your success in college. This blog will offer study tips and strategies to help you survive (and thrive!) in your first college class.

1. Don’t Cram!

It might be tempting to leave all your studying for that big exam up until the last minute, but research suggests that cramming does not improve longer term learning.

Students may perform well on a test for which they’ve crammed, but that doesn’t mean they’ve truly learned the material, says an article from the American Psychological Association . Instead of cramming, studies have shown that studying with the goal of long-term retention is best for learning overall.

2. Plan Ahead—and Stick To It!

Having a study plan with set goals can help you feel more prepared and can give you a roadmap to follow. Schwab said procrastination is one mistake that students often make when transitioning to a university-level course load.

“Oftentimes, students are used to less intensive workloads in high school, so one of my biggest pieces of advice is don’t cram,” says Schwab. “Set yourself a study schedule ahead of time and stick to it.”

3. Ask for Help

You don’t have to struggle through difficult material on your own. Many students are not used to seeking help while in high school, but seeking extra support is common in college.

As our guide to pursuing a biology major explains, “Be proactive about identifying areas where you need assistance and seek out that assistance immediately. The longer you wait, the more difficult it becomes to catch up.”

There are multiple resources to help you, including your professors, tutors, and fellow classmates. Harvard’s Academic Resource Center offers academic coaching, workshops, peer tutoring, and accountability hours for students to keep you on track.

4. Use the Buddy System

Your fellow students are likely going through the same struggles that you are. Reach out to classmates and form a study group to go over material together, brainstorm, and to support each other through challenges.

Having other people to study with means you can explain the material to one another, quiz each other, and build a network you can rely on throughout the rest of the class—and beyond.

5. Find Your Learning Style

It might take a bit of time (and trial and error!) to figure out what study methods work best for you. There are a variety of ways to test your knowledge beyond simply reviewing your notes or flashcards.

Schwab recommends trying different strategies through the process of metacognition. Metacognition involves thinking about your own cognitive processes and can help you figure out what study methods are most effective for you.

Schwab suggests practicing the following steps:

- Before you start to read a new chapter or watch a lecture, review what you already know about the topic and what you’re expecting to learn.

- As you read or listen, take additional notes about new information, such as related topics the material reminds you of or potential connections to other courses. Also note down questions you have.

- Afterward, try to summarize what you’ve learned and seek out answers to your remaining questions.

Explore summer courses for high school students.

6. Take Breaks

The brain can only absorb so much information at a time. According to the National Institutes of Health , research has shown that taking breaks in between study sessions boosts retention.

Studies have shown that wakeful rest plays just as important a role as practice in learning a new skill. Rest allows our brains to compress and consolidate memories of what we just practiced.

Make sure that you are allowing enough time, relaxation, and sleep between study sessions so your brain will be refreshed and ready to accept new information.

7. Cultivate a Productive Space

Where you study can be just as important as how you study.

Find a space that is free of distractions and has all the materials and supplies you need on hand. Eat a snack and have a water bottle close by so you’re properly fueled for your study session.

8. Reward Yourself

Studying can be mentally and emotionally exhausting and keeping your stamina up can be challenging.

Studies have shown that giving yourself a reward during your work can increase the enjoyment and interest in a given task.

According to an article for Science Daily , studies have shown small rewards throughout the process can help keep up motivation, rather than saving it all until the end.

Next time you finish a particularly challenging study session, treat yourself to an ice cream or an episode of your favorite show.

9. Review, Review, Review

Practicing the information you’ve learned is the best way to retain information.

Researchers Elizabeth and Robert Bjork have argued that “desirable difficulties” can enhance learning. For example, testing yourself with flashcards is a more difficult process than simply reading a textbook, but will lead to better long-term learning.

“One common analogy is weightlifting—you have to actually “exercise those muscles” in order to ultimately strengthen your memories,” adds Schwab.

10. Set Specific Goals

Setting specific goals along the way of your studying journey can show how much progress you’ve made. Psychology Today recommends using the SMART method:

- Specific: Set specific goals with an actionable plan, such as “I will study every day between 2 and 4 p.m. at the library.”

- Measurable: Plan to study a certain number of hours or raise your exam score by a certain percent to give you a measurable benchmark.

- Realistic: It’s important that your goals be realistic so you don’t get discouraged. For example, if you currently study two hours per week, increase the time you spend to three or four hours rather than 10.

- Time-specific: Keep your goals consistent with your academic calendar and your other responsibilities.

Using a handful of these study tips can ensure that you’re getting the most out of the material in your classes and help set you up for success for the rest of your academic career and beyond.

Learn more about our summer programs for high school students.

About the Author

Lian Parsons is a Boston-based writer and journalist. She is currently a digital content producer at Harvard’s Division of Continuing Education. Her bylines can be found at the Harvard Gazette, Boston Art Review, Radcliffe Magazine, Experience Magazine, and iPondr.

Becoming Independent: Skills You’ll Need to Survive Your First Year at College

Are you ready? Here are a few ideas on what it takes to flourish on campus.

Harvard Division of Continuing Education

The Division of Continuing Education (DCE) at Harvard University is dedicated to bringing rigorous academics and innovative teaching capabilities to those seeking to improve their lives through education. We make Harvard education accessible to lifelong learners from high school to retirement.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

How to Form Good Habits? A Longitudinal Field Study on the Role of Self-Control in Habit Formation

Anouk van der weiden.

1 Department of Social Health and Organizational Psychology, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands

2 Department of Social Economic and Organizational Psychology, Leiden University, Leiden, Netherlands

Jeroen Benjamins

3 Department of Experimental Psychology, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands

Marleen Gillebaart

Jan fekke ybema, denise de ridder, associated data.

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

When striving for long-term goals (e.g., healthy eating, saving money, reducing energy consumption, or maintaining interpersonal relationships), people often get in conflict with their short-term goals (e.g., enjoying tempting snacks, purchasing must-haves, getting warm, or watching YouTube video’s). Previous research suggests that people who are successful in controlling their behavior in line with their long-term goals rely on effortless strategies, such as good habits. In the present study, we aimed to track how self-control capacity affects the development of good habits in real life over a period of 90 days. Results indicated that habit formation increased substantially over the course of three months, especially for participants who consistently performed the desired behavior during this time. Contrary to our expectations, however, self-control capacity did not seem to affect the habit formation process. Directions for future research on self-control and other potential moderators in the formation of good habits are discussed.

Introduction

Sometimes people find themselves mindlessly watching TV while they had the intention to be more physically active; eating sweets while they wanted to eat more healthily; or lashing out at others while they wanted to be more patient or open-minded. Sounds familiar? Although people may often be able to control themselves in order to attain long-term goals such as healthy living or maintaining satisfactory relationships, there are also many instances in which they are unable or unwilling to exert self-control (e.g., when temptations are strong or when tired; e.g., Muraven and Slessareva, 2003 ; Baumeister et al., 2007 ; Hofmann et al., 2010 ). Also, some people are less successful in controlling their behaviors than others ( Schmeichel and Zell, 2007 ). In these cases, people often revert to effortless, habitual behavior ( Ouellette and Wood, 1998 ; Webb and Sheeran, 2006 ; Neal et al., 2013 ) – often bad habits. This reliance on habits may, however, also be used to peoples’ advantage if they manage to form good habits that are in line with their long-term goals. Indeed, recent research suggests that people who are successful in controlling their behavior, more effortlessly rely on good habits ( Adriaanse et al., 2014 ; Gillebaart and de Ridder, 2015 ). But how are good habits formed?

Research on habit formation has shown that behavior is likely to become habitual when it is frequently and consistently performed in the same context (e.g., Ouellette and Wood, 1998 ). For example, when one frequently and consistently eats vegetables for lunch, at some point eating vegetables for lunch will become a habit. This is because the frequent co-occurrence of context and behavior instigates an association that may guide future behavior (e.g., Aarts and Dijksterhuis, 2000 ; Neal et al., 2012 ). Specifically, when encountering a context (e.g., having lunch) that is associated with a certain behavior (e.g., eating vegetables), this context will automatically trigger this associated behavior. Hence, once a good habit is formed, it is rather effortless to perform desired behavior. However, the process of habit formation itself may vary in the amount of effort needed – although some people manage to form certain habits as quickly as 18 days, others need as much as half a year ( Lally et al., 2010 ). This raises the question how exactly do habits form over time?

Although research on habit formation is still in its infancy, recent studies have uncovered some of the mechanisms that underlie the habit formation process. One of the main findings is that the habit formation process within individuals unfolds asymptotically ( Lally et al., 2010 ; Fournier et al., 2017 ). That is, habit strength increases steeply at first, and then levels off. In addition, studies that studied habit formation on the group level (i.e., averaging over participants) have provided insight into the processes that facilitate such increases in habit strength. Specifically, the frequency and consistency with which the desired behavior is performed, the inherently rewarding nature of the behavior, a comfortable environment (e.g., no threats or obstacles), and easy rather than difficult behaviors have been shown to facilitate the process of habit formation ( Kaushal and Rhodes, 2015 ; Fournier et al., 2017 ).

Besides these factors, there are still many others unexplored that may explain the variation in the time it takes people to form a habit. One such likely candidate is self-control capacity. That is, habit formation crucially depends on the repeated performance of behavior that is in line with one’s long-term goal. The initiation of such new behavior, as well as the inhibition of acting upon short-term temptations is likely to require effortful self-control, especially in the early stages of habit formation. Indeed a study among teenagers indicates that those who initially had higher self-control capacity reported having stronger meditation habits after three months of meditation sessions ( Galla and Duckworth, 2015 , Study 5). Other studies revealed that habit strength mediates the effect of self-control strength and behavior. Specifically, self-control was related to increased habit strength, which was in turn related to increased exercise behavior ( Gillebaart and Adriaanse, 2017 ) and decreased snack intake ( Adriaanse et al., 2014 ). However, although these studies have indicated that self-control is related to habit strength, they do not provide insight in the role of self-control capacity in the initial stages of habit formation.

The current study was a first attempt to track how self-control capacity affects the development of good habits in daily life over a relatively long period of time. We expected both repeated goal-congruent behavior performance and self-control capacity to facilitate the formation of good habits. Possibly, self-control capacity may affect habit formation via increased behavior performance (as the initiation of new behavior and inhibition of conflicting behavior requires self-control at first). To test these hypotheses, we recruited people who wanted to form a good habit in the domain of health behavior (eating fruit or vegetables, exercising, or drinking water), interpersonal relationships (making more contact with others, being more patient or open-minded, or having more attention for others), personal finance (saving money), or environmental-friendly behavior (recycling). Over the course of three months, we then measured their goal-congruent behavior performance, self-control capacity, and habit strength to examine how self-control related to behavior performance and habit strength over time.

Participants and Design

A community sample was recruited via the population register of the city of Utrecht in the Netherlands as well as social media and the alumni register of Utrecht University. Anyone between the age of 18 and 65 who possessed a smartphone was eligible (we could provide a limited number of participants with a smartphone for the duration of the study if they did not possess one, N = 5). All participants indicated they wanted to form a habit in the health, sustainability, interpersonal, or financial domain.

The within-subjects design consisted of a pre-measurement administered in groups of 2–13 participants at a university location, 1 followed by a three-month interval of daily measures administered through an in-house developed mobile application, and after 90–110 days, a post-measurement (again in group sessions at a university location). In total, 180 people participated in the pre-measurement, of whom 90 participated in the post-measurement. Participants took part in the daily measures over a range of 17–110 days ( M = 77.0, SD = 26.7). During this time period, the number of bi-weekly self-control assessments ranged from 1 to 10 ( M = 6.5, SD = 2.3), which were alternated with bi-weekly habit strength assessments, of which the number ranged from 2 to 9 ( M = 5.7, SD = 2.0). In total, 146 participants (118 women; M age = 31.9; SD age = 12.7; range 18–61 years) who completed at least one follow-up assessment of habit strength were included in the analyses. More than half of them (65.8%) were community residents (including alumni) and the remainder (34.2%) were bachelor students. Based on participants’ postal code (which is indicative of education, income, and work status; Netherlands Institute for Social Research), we inferred their socio-economic status. About 10.3% of the participants lived in underprivileged neighborhoods, 61.0% lived in middle class neighborhoods, and 26.0% came from privileged neighborhoods (postal code data was missing for 4 participants). Participants’ initial level of habit strength was moderate ( M = 3.1, SD = 1.1).

Procedure and Materials

Registration.

Those who were interested in participating received an information letter via e-mail, containing a link to register for the study with a unique participation code. In the registration form, participants were reminded of the terms and conditions (i.e., voluntary nature of participation, ability to withdraw without explanation, etc.), after which they were required to give their consent for participating in the study. Participants could then schedule an appointment for the pre-measurement.

Pre-measurement

Participants came to the university for a pre-measurement as part of a larger longitudinal prospective study on trait self-control (i.e., to see whether self-control could be trained by daily performance of a behavior that requires self-control – which indeed seemed to be the case; de Ridder et al., 2019 ). As such, the different measurements (pre-, app-, and post-) also included measures that were not of interest for the current study. 2

Goal setting

At the start of the study, participants selected a specific behavior they wanted to turn into a habit over the course of the study. Choices covered health, interpersonal, financial, and ecological behaviors (e.g., eating fruit, being patient, saving money, recycling). Depending on the type of behavior chosen, participants could then choose from three to seven contexts for behavioral practice (e.g., eating fruit when having breakfast, being patient when talking to someone, 3 saving money when in the supermarket, or recycling when tidying up). As such, participants could choose which habit they wanted to form based on 60 preset combinations of behaviors and contexts. See Figure 1 for an overview of which behaviors were selected by the participants. It was emphasized that the selected behavior needed to be personally relevant to them, had to be a behavior they did not regularly perform yet, and had to be feasible for them to perform on a daily basis. After selecting a behavior and context, participants had to specify for themselves what this behavior entailed (e.g., when they chose exercise as their goal, it was explained that a ten minute routine at home was more feasible on a daily basis than an hour at the gym). As such, participants were intrinsically motivated and there was room for forming a new habit.

Overview of the number of participants selecting each behavior. Please note that exercise (“sporten” in Dutch) and physical activity (“bewegen” in Dutch) refers to different types of behaviors. Whereas exercise is typically associated with certain rules and competitiveness, but most of all with high intensity (e.g., playing football, cross fit, running), physical activity refers to more casual and less intense behaviors (e.g., walking or biking, gardening, household chores).

App instructions

For the purpose of this study, we developed a mobile app (which ran on iOS and android) to assess self-control capacity and habit strength on a regular basis. At the end of the pre-measurement, participants were instructed to install and use this app for daily tests and questionnaires. Participants were also informed that they would receive a reminder every morning via the mobile app.

App Measurements

Habit strength.

Habit strength was assessed bi-weekly with the Self-Report Habit Index ( Verplanken and Orbell, 2003 ), which consists of 12 statements (e.g., ‘[self-chosen behavior (e.g., eating fruit)] is something I do …frequently; …automatically; …without thinking)’. For each statement, participants indicated to what extent they felt the statement applied to them on a scale from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree). The scale proved reliable with a Cronbach’s alpha of.94. 4

Goal-congruent behavior performance

On a daily basis, participants indicated (dichotomously) whether or not they had performed the self-chosen behavior that day, and whether they performed this behavior in their self-chosen context. 5

Self-control capacity

Self-control capacity was assessed bi-weekly with the Brief Self-Control Scale ( Tangney et al., 2004 ), which consists of 13 statements (e.g., “I am good at resisting temptation” or “People would say I have iron self-discipline”). For each statement, participants indicated to what extent they felt the statement applied to them on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). The scale proved reliable with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.79.

Data Analysis

Habit formation over time – individual level analysis.

First, following Lally et al. (2010) approach, we attempted to fit an asymptotic curve to individual participants’ habit strength scores over time (by means of a Least Squares Curve Fit algorithm in Matlab), to then see whether we could predict the individual (rate of) change in habit strength as a function of goal-congruent behavior performance and self-control capacity. However, the individual patterns fluctuated too much (possibly because bi-weekly measurements were too infrequent; M = 5.73, SD = 1.99, range = 2–9 observations per participant; see Figure 2 for the number of observations plotted against the number of participants 6 ), and curve fitting could only be achieved for 4.11% of our participants (see results under point 2, Supplementary Material ). As an alternative, we also tried fitting a less constrained power curve ( y = ax b ), with even less success (2.4%). We therefore decided to analyze the data on the group level instead.