- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

- Edison and the Lumière brothers

- Méliès and Porter

- Early growth of the film industry

- Pre-World War I American cinema

- Pre-World War I European cinema

- D.W. Griffith

- The Soviet Union

- Post-World War I American cinema

- Conversion to sound

- Postsynchronization

- Nontechnical effects of sound

- Introduction of color

- The Hollywood studio system

- Great Britain

- Germany and Italy

- Soviet Union

- Decline of the Hollywood studios

- The fear of communism

- The threat of television

- China, Taiwan, and Korea

- Russia, eastern Europe, and Central Asia

- Spain and Mexico

- The youth cult and other trends of the late 1960s

- The effect of new technologies

- The expansion of media culture

- South Korea

- Eastern Europe and Russia

- Australia, New Zealand, and Canada

- United States

- What are some of the major film festivals?

history of film

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- ExplorePAhistory.com - Motion Pictures

- University of Minnesota Libraries - Understanding Media and Culture - The History of Movies

- Table Of Contents

Recent News

history of film , history of cinema , a popular form of mass media , from the 19th century to the present.

(Read Martin Scorsese’s Britannica essay on film preservation.)

Early years, 1830–1910

The illusion of films is based on the optical phenomena known as persistence of vision and the phi phenomenon . The first of these causes the brain to retain images cast upon the retina of the eye for a fraction of a second beyond their disappearance from the field of sight, while the latter creates apparent movement between images when they succeed one another rapidly. Together these phenomena permit the succession of still frames on a film strip to represent continuous movement when projected at the proper speed (traditionally 16 frames per second for silent films and 24 frames per second for sound films). Before the invention of photography, a variety of optical toys exploited this effect by mounting successive phase drawings of things in motion on the face of a twirling disk (the phenakistoscope , c. 1832) or inside a rotating drum (the zoetrope, c. 1834). Then, in 1839, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre , a French painter, perfected the positive photographic process known as daguerreotype , and that same year the English scientist William Henry Fox Talbot successfully demonstrated a negative photographic process that theoretically allowed unlimited positive prints to be produced from each negative. As photography was innovated and refined over the next few decades, it became possible to replace the phase drawings in the early optical toys and devices with individually posed phase photographs, a practice that was widely and popularly carried out.

There would be no true motion pictures, however, until live action could be photographed spontaneously and simultaneously. This required a reduction in exposure time from the hour or so necessary for the pioneer photographic processes to the one-hundredth (and, ultimately, one-thousandth) of a second achieved in 1870. It also required the development of the technology of series photography by the British American photographer Eadweard Muybridge between 1872 and 1877. During that time, Muybridge was employed by Gov. Leland Stanford of California, a zealous racehorse breeder, to prove that at some point in its gallop a horse lifts all four hooves off the ground at once. Conventions of 19th-century illustration suggested otherwise, and the movement itself occurred too rapidly for perception by the naked eye, so Muybridge experimented with multiple cameras to take successive photographs of horses in motion. Finally, in 1877, he set up a battery of 12 cameras along a Sacramento racecourse with wires stretched across the track to operate their shutters. As a horse strode down the track, its hooves tripped each shutter individually to expose a successive photograph of the gallop, confirming Stanford’s belief. When Muybridge later mounted these images on a rotating disk and projected them on a screen through a magic lantern, they produced a “moving picture” of the horse at full gallop as it had actually occurred in life.

The French physiologist Étienne-Jules Marey took the first series photographs with a single instrument in 1882; once again the impetus was the analysis of motion too rapid for perception by the human eye . Marey invented the chronophotographic gun, a camera shaped like a rifle that recorded 12 successive photographs per second, in order to study the movement of birds in flight. These images were imprinted on a rotating glass plate (later, paper roll film), and Marey subsequently attempted to project them. Like Muybridge, however, Marey was interested in deconstructing movement rather than synthesizing it, and he did not carry his experiments much beyond the realm of high-speed, or instantaneous, series photography. Muybridge and Marey, in fact, conducted their work in the spirit of scientific inquiry; they both extended and elaborated existing technologies in order to probe and analyze events that occurred beyond the threshold of human perception. Those who came after would return their discoveries to the realm of normal human vision and exploit them for profit.

In 1887 in Newark, New Jersey , an Episcopalian minister named Hannibal Goodwin developed the idea of using celluloid as a base for photographic emulsions. The inventor and industrialist George Eastman , who had earlier experimented with sensitized paper rolls for still photography, began manufacturing celluloid roll film in 1889 at his plant in Rochester, New York . This event was crucial to the development of cinematography : series photography such as Marey’s chronophotography could employ glass plates or paper strip film because it recorded events of short duration in a relatively small number of images, but cinematography would inevitably find its subjects in longer, more complicated events, requiring thousands of images and therefore just the kind of flexible but durable recording medium represented by celluloid. It remained for someone to combine the principles embodied in the apparatuses of Muybridge and Marey with celluloid strip film to arrive at a viable motion-picture camera .

Such a device was created by French-born inventor Louis Le Prince in the late 1880s. He shot several short films in Leeds, England, in 1888, and the following year he began using the newly invented celluloid film. He was scheduled to show his work in New York City in 1890, but he disappeared while traveling in France. The exhibition never occurred, and Le Prince’s contribution to cinema remained little known for decades. Instead it was William Kennedy Laurie Dickson , working in the West Orange , New Jersey, laboratories of the Edison Company, who created what was widely regarded as the first motion-picture camera.

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Essay Film

Introduction, anthologies.

- Bibliographies

- Spectator Engagement

- Personal Documentary

- 1940s Watershed Years

- Chris Marker

- Alain Resnais

- Jean-Luc Godard

- Harun Farocki

- Latin American Cinema

- Installation and Exhibition

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Documentary Film

- Dziga Vertov

- Trinh T. Minh-ha

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Superhero Films

- Wim Wenders

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Essay Film by Yelizaveta Moss LAST REVIEWED: 24 March 2021 LAST MODIFIED: 24 March 2021 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199791286-0216

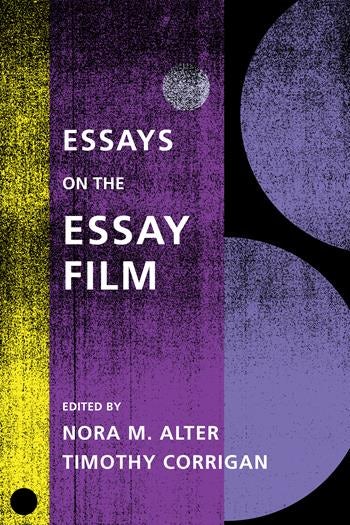

The term “essay film” has become increasingly used in film criticism to describe a self-reflective and self-referential documentary cinema that blurs the lines between fiction and nonfiction. Scholars unanimously agree that the first published use of the term was by Richter in 1940. Also uncontested is that Andre Bazin, in 1958, was the first to analyze a film, which was Marker’s Letter from Siberia (1958), according to the essay form. The French New Wave created a popularization of short essay films, and German New Cinema saw a resurgence in essay films due to a broad interest in examining German history. But beyond these origins of the term, scholars deviate on what exactly constitutes an essay film and how to categorize essay films. Generally, scholars fall into two camps: those who find a literary genealogy to the essay film and those who find a documentary genealogy to the essay film. The most commonly cited essay filmmakers are French and German: Marker, Resnais, Godard, and Farocki. These filmmakers are singled out for their breadth of essay film projects, as opposed to filmmakers who have made an essay film but who specialize in other genres. Though essay films have been and are being produced outside of the West, scholarship specifically addressing essay films focuses largely on France and Germany, although Solanas and Getino’s theory of “Third Cinema” and approval of certain French essay films has produced some essay film scholarship on Latin America. But the gap in scholarship on global essay film remains, with hope of being bridged by some forthcoming work. Since the term “essay film” is used so sparingly for specific films and filmmakers, the scholarship on essay film tends to take the form of single articles or chapters in either film theory or documentary anthologies and journals. Some recent scholarship has pointed out the evolutionary quality of essay films, emphasizing their ability to change form and style as a response to conventional filmmaking practices. The most recent scholarship and conference papers on essay film have shifted from an emphasis on literary essay to an emphasis on technology, arguing that essay film has the potential in the 21st century to present technology as self-conscious and self-reflexive of its role in art.

Both anthologies dedicated entirely to essay film have been published in order to fill gaps in essay film scholarship. Biemann 2003 brings the discussion of essay film into the digital age by explicitly resisting traditional German and French film and literary theory. Papazian and Eades 2016 also resists European theory by explicitly showcasing work on postcolonial and transnational essay film.

Biemann, Ursula, ed. Stuff It: The Video Essay in the Digital Age . New York: Springer, 2003.

This anthology positions Marker’s Sans Soleil (1983) as the originator of the post-structuralist essay film. In opposition to German and French film and literary theory, Biemann discusses video essays with respect to non-linear and non-logical movement of thought and a range of new media in Internet, digital imaging, and art installation. In its resistance to the French/German theory influence on essay film, this anthology makes a concerted effort to include other theoretical influences, such as transnationalism, postcolonialism, and globalization.

Papazian, Elizabeth, and Caroline Eades, eds. The Essay Film: Dialogue, Politics, Utopia . London: Wallflower, 2016.

This forthcoming anthology bridges several gaps in 21st-century essay film scholarship: non-Western cinemas, popular cinema, and digital media.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Cinema and Media Studies »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- 2001: A Space Odyssey

- À bout de souffle

- Accounting, Motion Picture

- Action Cinema

- Advertising and Promotion

- African American Cinema

- African American Stars

- African Cinema

- AIDS in Film and Television

- Akerman, Chantal

- Allen, Woody

- Almodóvar, Pedro

- Altman, Robert

- American Cinema, 1895-1915

- American Cinema, 1939-1975

- American Cinema, 1976 to Present

- American Independent Cinema

- American Independent Cinema, Producers

- American Public Broadcasting

- Anderson, Wes

- Animals in Film and Media

- Animation and the Animated Film

- Arbuckle, Roscoe

- Architecture and Cinema

- Argentine Cinema

- Aronofsky, Darren

- Arzner, Dorothy

- Asian American Cinema

- Asian Television

- Astaire, Fred and Rogers, Ginger

- Audiences and Moviegoing Cultures

- Australian Cinema

- Authorship, Television

- Avant-Garde and Experimental Film

- Bachchan, Amitabh

- Battle of Algiers, The

- Battleship Potemkin, The

- Bazin, André

- Bergman, Ingmar

- Bernstein, Elmer

- Bertolucci, Bernardo

- Bigelow, Kathryn

- Birth of a Nation, The

- Blade Runner

- Blockbusters

- Bong, Joon Ho

- Brakhage, Stan

- Brando, Marlon

- Brazilian Cinema

- Breaking Bad

- Bresson, Robert

- British Cinema

- Broadcasting, Australian

- Buffy the Vampire Slayer

- Burnett, Charles

- Buñuel, Luis

- Cameron, James

- Campion, Jane

- Canadian Cinema

- Capra, Frank

- Carpenter, John

- Cassavetes, John

- Cavell, Stanley

- Chahine, Youssef

- Chan, Jackie

- Chaplin, Charles

- Children in Film

- Chinese Cinema

- Cinecittà Studios

- Cinema and Media Industries, Creative Labor in

- Cinema and the Visual Arts

- Cinematography and Cinematographers

- Citizen Kane

- City in Film, The

- Cocteau, Jean

- Coen Brothers, The

- Colonial Educational Film

- Comedy, Film

- Comedy, Television

- Comics, Film, and Media

- Computer-Generated Imagery (CGI)

- Copland, Aaron

- Coppola, Francis Ford

- Copyright and Piracy

- Corman, Roger

- Costume and Fashion

- Cronenberg, David

- Cuban Cinema

- Cult Cinema

- Dance and Film

- de Oliveira, Manoel

- Dean, James

- Deleuze, Gilles

- Denis, Claire

- Deren, Maya

- Design, Art, Set, and Production

- Detective Films

- Dietrich, Marlene

- Digital Media and Convergence Culture

- Disney, Walt

- Downton Abbey

- Dr. Strangelove

- Dreyer, Carl Theodor

- Eastern European Television

- Eastwood, Clint

- Eisenstein, Sergei

- Elfman, Danny

- Ethnographic Film

- European Television

- Exhibition and Distribution

- Exploitation Film

- Fairbanks, Douglas

- Fan Studies

- Fellini, Federico

- Film Aesthetics

- Film and Literature

- Film Guilds and Unions

- Film, Historical

- Film Preservation and Restoration

- Film Theory and Criticism, Science Fiction

- Film Theory Before 1945

- Film Theory, Psychoanalytic

- Finance Film, The

- French Cinema

- Game of Thrones

- Gance, Abel

- Gangster Films

- Garbo, Greta

- Garland, Judy

- German Cinema

- Gilliam, Terry

- Global Television Industry

- Godard, Jean-Luc

- Godfather Trilogy, The

- Golden Girls, The

- Greek Cinema

- Griffith, D.W.

- Hammett, Dashiell

- Haneke, Michael

- Hawks, Howard

- Haynes, Todd

- Hepburn, Katharine

- Herrmann, Bernard

- Herzog, Werner

- Hindi Cinema, Popular

- Hitchcock, Alfred

- Hollywood Studios

- Holocaust Cinema

- Hong Kong Cinema

- Horror-Comedy

- Hsiao-Hsien, Hou

- Hungarian Cinema

- Icelandic Cinema

- Immigration and Cinema

- Indigenous Media

- Industrial, Educational, and Instructional Television and ...

- Invasion of the Body Snatchers

- Iranian Cinema

- Irish Cinema

- Israeli Cinema

- It Happened One Night

- Italian Americans in Cinema and Media

- Italian Cinema

- Japanese Cinema

- Jazz Singer, The

- Jews in American Cinema and Media

- Keaton, Buster

- Kitano, Takeshi

- Korean Cinema

- Kracauer, Siegfried

- Kubrick, Stanley

- Lang, Fritz

- Latina/o Americans in Film and Television

- Lee, Chang-dong

- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ) Cin...

- Lord of the Rings Trilogy, The

- Los Angeles and Cinema

- Lubitsch, Ernst

- Lumet, Sidney

- Lupino, Ida

- Lynch, David

- Marker, Chris

- Martel, Lucrecia

- Masculinity in Film

- Media, Community

- Media Ecology

- Memory and the Flashback in Cinema

- Metz, Christian

- Mexican Cinema

- Micheaux, Oscar

- Ming-liang, Tsai

- Minnelli, Vincente

- Miyazaki, Hayao

- Méliès, Georges

- Modernism and Film

- Monroe, Marilyn

- Mészáros, Márta

- Music and Cinema, Classical Hollywood

- Music and Cinema, Global Practices

- Music, Television

- Music Video

- Musicals on Television

- Native Americans

- New Media Art

- New Media Policy

- New Media Theory

- New York City and Cinema

- New Zealand Cinema

- Opera and Film

- Ophuls, Max

- Orphan Films

- Oshima, Nagisa

- Ozu, Yasujiro

- Panh, Rithy

- Pasolini, Pier Paolo

- Passion of Joan of Arc, The

- Peckinpah, Sam

- Philosophy and Film

- Photography and Cinema

- Pickford, Mary

- Planet of the Apes

- Poems, Novels, and Plays About Film

- Poitier, Sidney

- Polanski, Roman

- Polish Cinema

- Politics, Hollywood and

- Pop, Blues, and Jazz in Film

- Pornography

- Postcolonial Theory in Film

- Potter, Sally

- Prime Time Drama

- Queer Television

- Queer Theory

- Race and Cinema

- Radio and Sound Studies

- Ray, Nicholas

- Ray, Satyajit

- Reality Television

- Reenactment in Cinema and Media

- Regulation, Television

- Religion and Film

- Remakes, Sequels and Prequels

- Renoir, Jean

- Resnais, Alain

- Romanian Cinema

- Romantic Comedy, American

- Rossellini, Roberto

- Russian Cinema

- Saturday Night Live

- Scandinavian Cinema

- Scorsese, Martin

- Scott, Ridley

- Searchers, The

- Sennett, Mack

- Sesame Street

- Shakespeare on Film

- Silent Film

- Simpsons, The

- Singin' in the Rain

- Sirk, Douglas

- Soap Operas

- Social Class

- Social Media

- Social Problem Films

- Soderbergh, Steven

- Sound Design, Film

- Sound, Film

- Spanish Cinema

- Spanish-Language Television

- Spielberg, Steven

- Sports and Media

- Sports in Film

- Stand-Up Comedians

- Stop-Motion Animation

- Streaming Television

- Sturges, Preston

- Surrealism and Film

- Taiwanese Cinema

- Tarantino, Quentin

- Tarkovsky, Andrei

- Tati, Jacques

- Television Audiences

- Television Celebrity

- Television, History of

- Television Industry, American

- Theater and Film

- Theory, Cognitive Film

- Theory, Critical Media

- Theory, Feminist Film

- Theory, Film

- Theory, Trauma

- Touch of Evil

- Transnational and Diasporic Cinema

- Trinh, T. Minh-ha

- Truffaut, François

- Turkish Cinema

- Twilight Zone, The

- Varda, Agnès

- Vertov, Dziga

- Video and Computer Games

- Video Installation

- Violence and Cinema

- Virtual Reality

- Visconti, Luchino

- Von Sternberg, Josef

- Von Stroheim, Erich

- von Trier, Lars

- Warhol, The Films of Andy

- Waters, John

- Wayne, John

- Weerasethakul, Apichatpong

- Weir, Peter

- Welles, Orson

- Whedon, Joss

- Wilder, Billy

- Williams, John

- Wiseman, Frederick

- Wizard of Oz, The

- Women and Film

- Women and the Silent Screen

- Wong, Anna May

- Wong, Kar-wai

- Wood, Natalie

- Yang, Edward

- Yimou, Zhang

- Yugoslav and Post-Yugoslav Cinema

- Zinnemann, Fred

- Zombies in Cinema and Media

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [185.126.86.119]

- 185.126.86.119

The History of Film Timeline — All Eras of Film History Explained

M otion pictures have enticed and inspired artists, audiences, and critics for more than a century. Today, we’re going to explore the history of film by looking at the major movements that have defined cinema worldwide. We’re also going to explore the technical craft of filmmaking from the persistence of vision to colorization to synchronous sound. By the end, you’ll know all the broad strokes in the history of film.

Note: this article doesn’t cover every piece of film history. Some minor movements and technical breakthroughs have been left out – check out the StudioBinder blog for more content.

- Pre-Film: Photographic Techniques and Motion Picture Theory

- The Nascent Film Era (1870s-1910): The First Motion Pictures

- The First Film Movements: Dadaism, German Expressionism, and Soviet Montage Theory

- Manifest Destiny and the End of the Silent Era

- Hollywood Epics and the Pre-Code Era

- The Early Golden Age and the Introduction of Color

- Wartime Film and Cinematic Propaganda

- Post-War Film Movements: French New Wave, Italian Neorealism, Scandinavian Revival, and Bengali Cinema

- The Golden Age of Hollywood: The Studio System and Censorship

- New Hollywood: The Emergence of Global Blockbuster Cinema

- Dogme 95 and the Independent Movement

- New Methods of Cinematic Distribution and the Current State of Film

When Were Movies Invented?

Pre-film techniques and theory.

Movies refer to moving pictures and moving pictures can be traced all the way back to prehistoric times. Have you ever made a shadow puppet show? If you have, then you’ve made a moving picture.

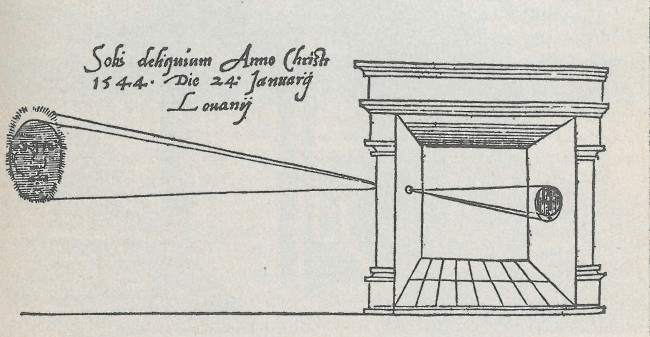

To create a moving picture with your hands is one thing, to utilize a device is another. The camera obscura (believed to have been circulated in the fifth century BCE) is perhaps the oldest photographic device in existence. The camera obscura is a device that’s used to reproduce images by reflecting light through a small peephole.

Here’s a picture of one from Gemma Frisius’ 1545 book De Radio Astronomica et Geometrica :

When Did Movies Start? • Camera Obscura in ‘De Radio Astronomica et Geometrica’

Through the camera obscura, we can trace the principles of filmmaking back thousands of years. But despite the technical achievement of the camera obscura, it took many of those years to develop the technology needed to capture moving images then later display them.

When Was Film Invented?

The first motion pictures.

When were movies invented ? The first motion pictures were incredibly simple – usually just a few frames of people or animals. Eadweard Muybridge’s The Horse in Motion is perhaps the most famous of these early motion pictures. In 1878, Muybridge set up a racing track with 24 cameras to photograph whether horses gallop with all four hooves off the ground at any time

The result was sensational. Muybridge’s pictures set the stage for all coming films; check out a short video on Muybridge and his work below.

When Did the First Movie Come Out? • Eadweard Muybridge’s ‘The Horse in Motion’ by San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Muybridge’s job wasn’t done after taking the photographs though; he still had to produce a projection machine to display them. So, Muybridge built a device called the zoopraxiscope, which was regarded as a breakthrough device for motion picture projecting.

Muybridge’s films (and tech) inspired Thomas Edison to study motion picture theory and develop his own camera equipment.

Films as we know them today emerged globally around the turn of the century, circa 1900. Much of that development can be attributed to the works of the Lumière Brothers, who together pioneered the technical craft of moviemaking with their cinematograph projection machine. The Lumière Brothers’ 1895 shorts are regarded as the first commercial films of all-time; though not technically true (remember Muybridge’s work).

French actor and illusionist Georges Méliès attempted to buy a cinematograph from the Lumière Brothers in 1895, but was denied. So, Méliès ventured elsewhere; eventually finding a partner in Englishman Robert W. Paul.

Over the following years, Méliès learned just about everything there was to know about movies and projection machines. Here’s a video on Méliès’ master of film and the illusory arts from Crash Course Film History.

When Were Movies Invented? • Georges Méliès – Master of Illusion by Crash Course

Méliès’ shorts The One Man Band (1900) and A Trip to the Moon (1902) are considered two of the most trailblazing films in all of film history. Over the course of his career, Méliès produced over 500 films. His contemporary mastery of visual effects , multiple exposure , and cinematography made him one of the greatest filmmakers of all-time .

Movie History

The first film movements.

War and cinema go together like two peas in a pod. As we continue on through our analysis of the history of film, you’ll start to notice that just about every major movement sprouted in the wake of war. First, the movements that sprouted in response to World War I:

DADAISM AND SURREALISM

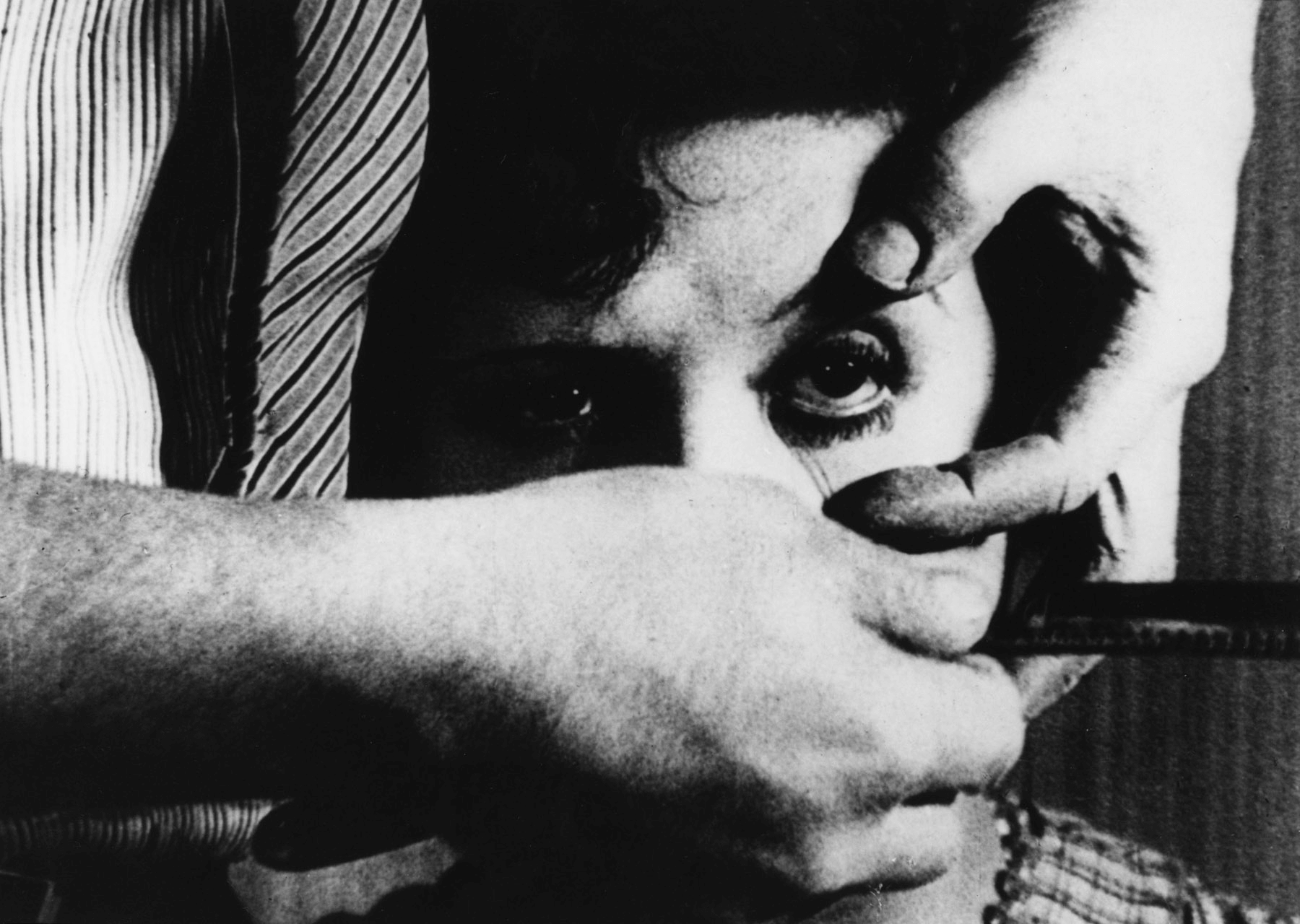

History of Motion Pictures • Still From ‘Un Chien Andalou’ by Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí

Major Dadaist filmmakers: Luis Buñuel, Salvador Dalí, Germaine Dulac.

Major Dadaist films: Return to Reason (1923), The Seashell and the Clergyman (1928), U n Chien Andalou (1929).

Dadaism – an art movement that began in Zurich, Switzerland during World War I (1915) – rejected authority; effectively laying the groundwork for surrealist cinema .

Dadaism may have begun in Zurich circa 1915, but it didn’t take off until years later in Paris, France. By 1920, the people of France had expressed a growing disillusionment with the country’s government and economy. Sound familiar?

That’s because they’re the same points of conflict that incited the French Revolution. But this time around, the French people revolted in a different way: with art. And not just any art: bonkers, crazy, absurd, anti-this, anti-that art.

It’s important to note that Paris wasn’t the only place where dadaist art was being created. But it was the place where most of the dadaist, surrealist film was being created. We’ll get to dadaist film in a short bit, but first, let’s review a quick video on Dada art from Curious Muse.

Where Did Film Originate? • Dadaism in 8 Minutes by Curious Muse

Salvador Dalí, Germaine Dulac, and Luis Buñuel were some of the forefront faces of the surrealist film movement of the 1920s. French filmmakers, such as Jean Epstein and Jean Renoir experimented with surrealist films during this era as well.

Dalí and Buñuel’s 1929 film Un Chien Andalou is undoubtedly one of the most influential surrealist/dadaist films. Let’s check out a clip:

History of Movies • ‘Un Chien Andalou’ Clip

The influence of Un Chien Andalou on surrealist cinema can’t be quantified; key similarities can be seen between the film and the works of Walt Disney, David Lynch , Terry Gilliam , and other surrealist directors.

Learn more about surrealism in film →

GERMAN EXPRESSIONISM

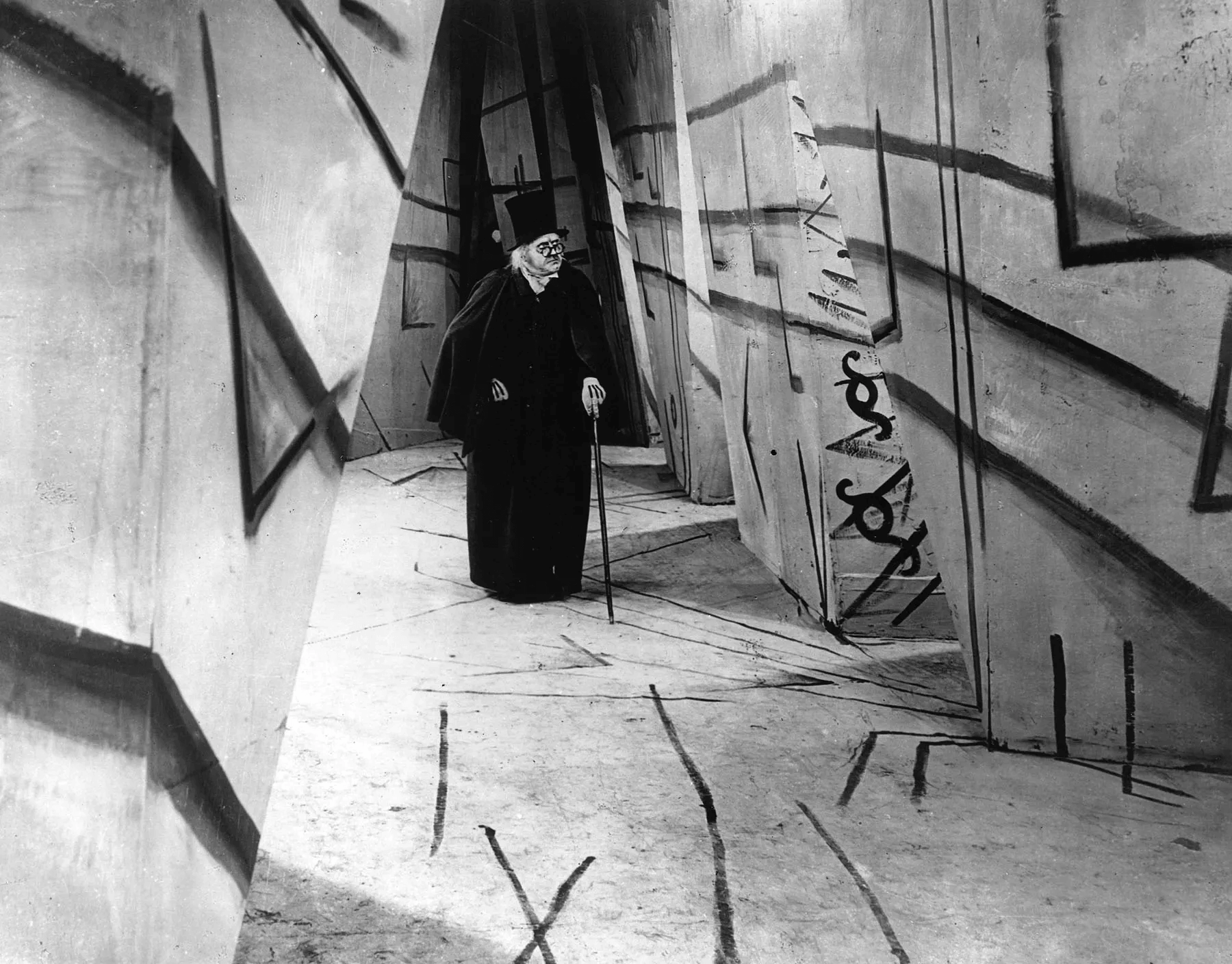

The Creation of Film and German Expressionism • Still From ‘The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari’ by Robert Wiene

- German Expressionism – an art movement defined by monumentalist structures and ideas – began before World War I but didn’t take off in popularity until after the war, much like the Dadaist movement.

- Major German Expressionist filmmakers: Fritz Lang, F.W. Murnau, Robert Wiene

- Major German Expressionist films: The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), Nosferatu (1922), and Metropolis (1927).

German Expressionism changed everything for the “look” and “feel” of cinema. When you think of German Expressionism, think contrast, gothic, dark, brooding imagery and colored filters. Here’s a quick video on the German Expressionist movement from Crash Course:

History of Film Timeline • German Expressionism Explained

The great works of the German Expressionist movement are some of the earliest movies I consider accessible to modern audiences. Perhaps no German Expressionist film proves this point better than Fritz Lang’s M ; which was the ultimate culmination of the movement’s stylistic tenets. Check out the trailer for M below.

Most Important Film in History of German Expressionism • ‘M’ (1931) Trailer, Restored by BFI

M not only epitomized the “monster” tone of the German Expressionist era, it set the stage for all future psychological thrillers. The film also pioneered sound engineering in film through the clever use of diegetic and non-diegetic sound . Fun fact: it was also one of the first movies to incorporate a leitmotif as part of its soundtrack.

Over time, the stylistic flourishes of the German Expressionist movement gave way to new voices – but its influence lived on in monster-horror and chiaroscuro lighting techniques.

Learn more about German Expressionism →

SOVIET MONTAGE THEORY

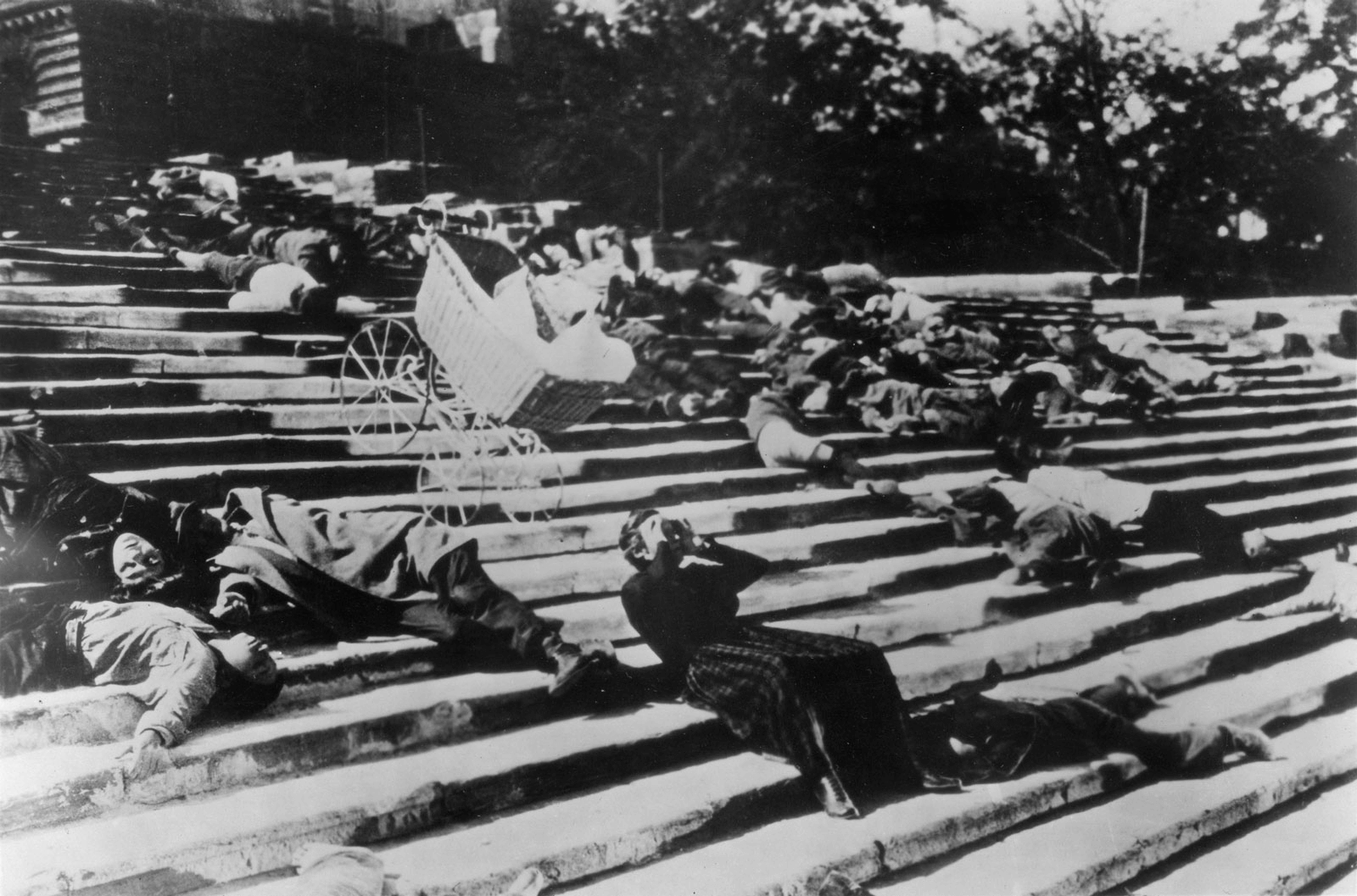

Film History 101 • The Odessa Steps in ‘Battleship Potemkin’

- Soviet Montage Theory – a Soviet Russian film movement that helped establish the principles of film editing – took place from the 1910s to the 1930s.

- Major Soviet Montage Theory filmmakers: Lev Kuleshov, Sergei Eisenstein , Dziga Vertov.

- Major Soviet Montage Theory films: Kino-Eye (1924), Battleship Potemkin (1925), Man With a Movie Camera (1929).

Soviet Montage Theory was a deconstructionist film movement, so as to say it wasn’t as interested in making movies as it was taking movies apart… or seeing how they worked. That being said, Soviet Montage Theory did produce some classics.

Here’s a video on Soviet Montage Theory from Filmmaker IQ:

Eras of Movies • The History of Cutting in Soviet Montage Theory by Filmmaker IQ

The Bolshevik government set-up a film school called VGIK (the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography) after the Russian Revolution. The practitioners of Soviet Montage Theory were the OG members of the “film school generation;” Kuleshov and Eisenstein were their teachers.

Battleship Potemkin was the most noteworthy film to come out of the Soviet Montage Theory movement. Check out an awesome analysis from One Hundred Years of Cinema below.

History of Film Summary • How Sergei Eisenstein Used Montage to Film the Unfilmable by One Hundred Years of Cinema

Soviet Montage Theory begged filmmakers to arrange, deconstruct, and rearrange film clips to better communicate emotional associations to audiences. The legacy of Soviet Montage Theory lives on in the form of the Kuleshov effect and contemporary montages .

Learn more about Soviet Montage Theory →

When Did Movies Become Popular?

The end of the silent era.

There was no Hollywood in the early years of American cinema – there was only Thomas Edison’s Motion Picture Patents Company in New Jersey.

Ever wonder why Europe seemed to dominate the early years of film? Well it was because Thomas Edison sued American filmmakers into oblivion. Edison owned a litany of U.S. patents on camera tech – and he wielded his stamps of ownership with righteous fury. The Edison Manufacturing Company did produce some noteworthy early films – such as 1903’s The Great Train Robbery – but their gaps were few and far between.

To escape Edison’s legal monopoly, filmmakers ventured west, all the way to Southern California.

Fortunate for the nomads: the arid temperature and mountainous terrain of Southern California proved perfect for making movies. By the early 1910s, Hollywood emerged as the working capital of the United States’s movie industry.

Director/actors like Charlie Chaplin , Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton became stars – but remember, movies were silent, and people knew there would be an acoustic revolution in cinema. Before we move on from the Silent Era, check out this great video from Crash Course.

When Did Movies Become Popular? • The Silent Era by Crash Course

The Silent Era holds an important place in film history – but it was mostly ushered out in 1927 with The Jazz Singer . Al Jolson singing in The Jazz Singer is considered the first time sound ever synchronized with a feature film . Over the next few years, Hollywood cinema exploded in popularity. This short period from 1927-1934 is known as pre-Code Hollywood.

When Did Hollywood Start?

Pre-code hollywood.

In our previous section, we touched on the rise of Hollywood, but not the Hollywood epic. The Hollywood epic, which we regard as longer in duration and wider in scope than the average movie, set the stage for blockbuster cinema. So, let’s quickly touch on the history of Hollywood epics before jumping into pre-code Hollywood.

It’s impossible to talk about Hollywood epics without bringing up D.W. Griffith. Griffith was an American film director who created a lot of what we consider “the structure” of feature films. His 1915 epic The Birth of a Nation brought the technique of cinematic storytelling into the future, while consequently keeping its subject matter in the objectionable past.

For more on Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (and its complicated legacy), check out this poignant interview clip with Spike Lee .

History of Filmmaking • Spike Lee on ‘The Birth of a Nation’

As Lee suggests, it’s important to acknowledge the technical achievement of films like The Birth of a Nation and Gone With the Wind without condoning their horrid subject matter.

As another great director once said: “tomorrow’s democracy discriminates against discrimination. Its charter won’t include the freedom to end freedom.” – Orson Welles.

Griffith made more than a few Hollywood epics in his time, but none were more famous than The Birth of a Nation .

Okay, now that we reviewed the foundations of the Hollywood epic, let’s move on to pre-code Hollywood.

PRE-CODE HOLLYWOOD

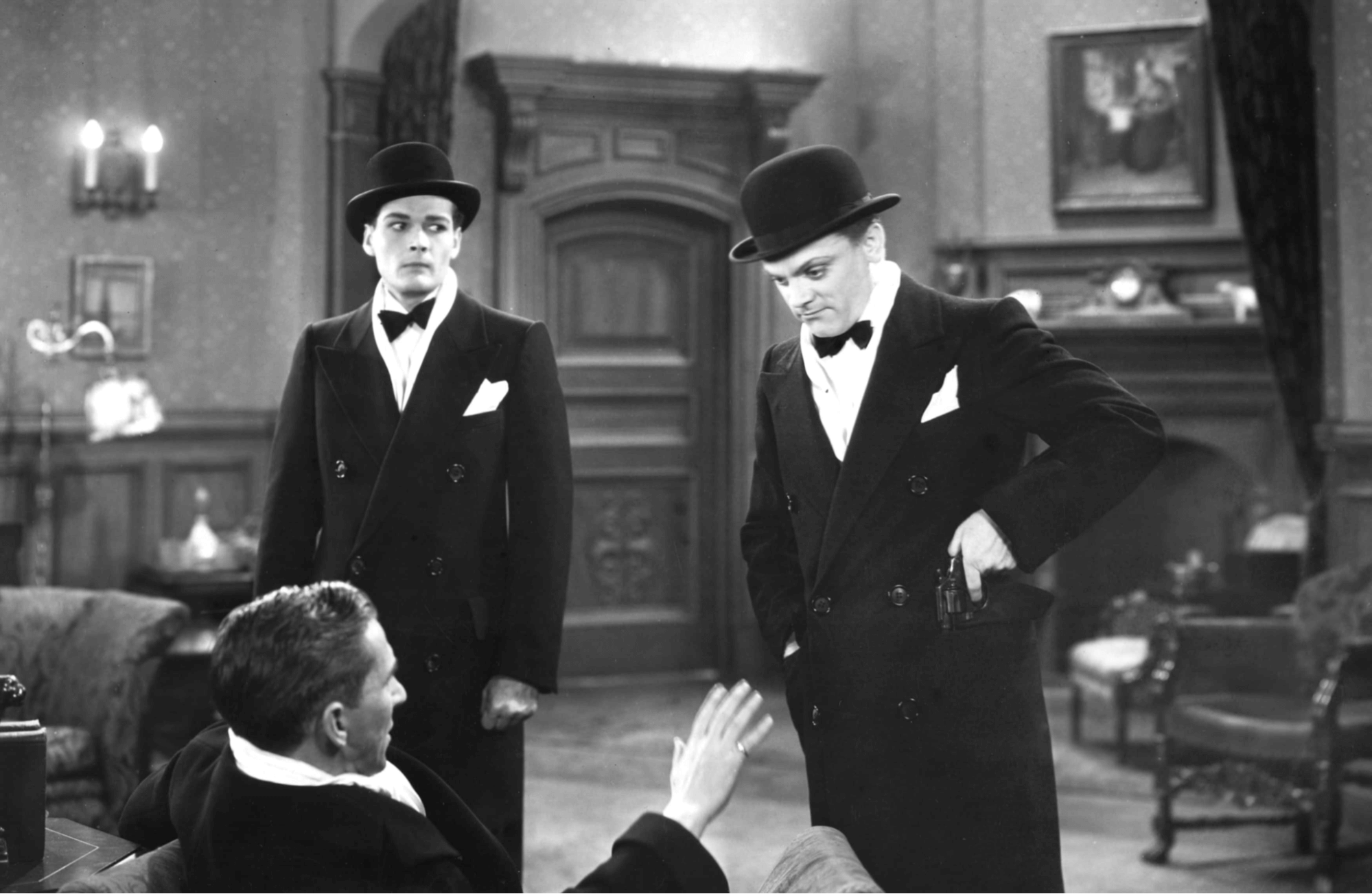

A History of Film • James Cagney in ‘The Public Enemy’

- Pre-Code Hollywood – a period in Hollywood history after the advent of sound but before the institution of the Hays Code – circa ~1927-1934.

- Major Pre-Code stars: Ruth Chatterton, Warren William, James Cagney.

- Major Pre-Code films: Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931), The Public Enemy (1931), Baby Face (1933).

Pre-Code Hollywood was wild. Not just wild in an uninhibited sense, but in a thematic sense too. Films produced during the pre-Code era often focused on illicit subject matter, like bootlegging, prostitution, and murder – that wasn't the status quo for Hollywood – and it wouldn’t be again until 1968.

We’ll get to why that year is important for film history in a bit, but first let’s review pre-Code Hollywood with a couple of selected scenes from Kevin Wentink on YouTube.

Movie Film History • Pre-Code Classic Clips

Pre-Code movies were jubilant in their creativity; largely because they were uncensored . But alas, their period was short-lived. In 1934, MPPDA Chairman William Hays instituted the Motion Picture Production Code banning explicit depictions of sex, violence, and other “sinful” deeds in movies.

Learn more about Pre-Code Hollywood →

Development of Movies

The early golden age and color in film.

The 1930s and early 1940s produced some of the greatest movies of all-time – but they also changed everything about the movie-making process. By the end of the Pre-Code era, the free independent spirit of filmmaking had all but evaporated; Hollywood studios had vertically integrated their business operations, which meant they conceptualized, produced, and distributed everything “in-house.”

That doesn’t mean movies made during these years were bad though. Quite the contrary – perhaps the two greatest American films ever made, Citizen Kane and Casablanca , were made between 1934 and 1944.

But despite their enormous influence, neither Citizen Kane nor Casablanca could hold a candle to the influence of another film from this decade: The Wizard of Oz .

The Wizard of Oz wasn’t the first film to use Technicolor , but it was credited with bringing color to the masses. For more on the industry-altering introduction of color, check out this video on The Wizard of Oz from Vox.

When Was Color Movies Invented? • How Technicolor Changed Movies

Technicolor was groundbreaking for cinema, but the dye-transfer process of its colorization was hard… and cost prohibitive for studios. So, camera manufacturers experimented with new processes to streamline color photography. Overtime, they were rewarded with new technologies and techniques.

Learn more about Technicolor →

Cinema Eras

Wartime and propaganda films.

In 1937, Benito Mussolini founded Cinecittà , a massive studio that operated under the slogan “Il cinema è l'arma più forte,” which translates to “the cinema is the strongest weapon.” During this time, countries all around the world used cinema as a weapon to influence the minds and hearts of their citizens.

This was especially true in the United States – prolific directors like Frank Capra, John Ford, John Huston, George Stevens, and William Wyler enlisted in the U.S. Armed Forces to make movies to support the U.S. war cause.

Documentarian Laurent Bouzereau made a three-part series about the war films of Capra, Ford, Huston, Stevens, and Wyler. Check out the trailer for Five Came Back below.

A History of Film • Five Came Back Trailer

Wartime film is important to explore because it teaches us about how people interpret propaganda. For posterity’s sake, let’s define propaganda as biased information that’s used to promote political points.

Propaganda films are often regarded with a negative connotation because they sh0w a one-sided perspective. Films of this era – such as those commissioned for the US Department of War’s Why We Fight series – were one-sided because they were made to counter the enemy’s rhetoric. It’s important to note that “one-sided” doesn’t mean “wrong” – in the case of the Why We Fight series, I think most people would agree that the one-sidedness was appropriate.

Over time, wartime film became more nuanced – a point proven by the 1966 masterwork The Battle of Algiers .

History of Movies

Post-war film movements.

Global cinema underwent a renaissance after World War II; technically, creatively, and conceptually. We’re going to cover a few of the most prominent post-war film movements, starting with Italian Neorealism.

ITALIAN NEOREALISM

Movie Film History • Still from Vittorio De Sica’s ‘Umberto D.’

- Italian Neorealism (1944-1960) – an Italian film movement that brought filmmaking to the streets; defined by depictions of the Italian state after World War II.

- Major Italian Neorealist film-makers: Vittorio De Sica, Roberto Rossellini, Michelangelo Antonioni, Luchino Visconti, Federico Fellini .

- Major Italian Neorealist films: Rome, Open City (1945), Bicycle Thieves (1948), La Strada (1954), Il Posto (1961).

Martin Scorcese called Italian Neorealism “the rehabilitation of an entire culture and people through cinema.” World War II devastated the Italian state: socially, economically, and culturally.

It took people’s lives and jobs, but perhaps more importantly, it took their humanity. After the War, the people needed an outlet of expression, and a place to reconstruct a new national identity. Here’s a quick video on Italian Neorealism.

Movie History • How Italian Neorealism Brought the Grit of the Streets to the Big Screen by No Film School

Italian Neorealism produced some of the greatest films ever made. There’s some debate as to when the movement started and ended – some say 1943-1954, others say 1945-1955 – but I say it started with Rome, Open City and ended with Il Posto . Why? Because those movies perfectly encompass the defining arc of Italian Neorealism, from street-life after World War II to the rise of bureaucracy. Rome, Open City shows Italy in the thick of chaos, and Il Posto shows Italy on the precipice of a new era.

The legacy of Italian Neorealism lives on in the independent filmmaking of directors like Richard Linklater, Steven Soderbergh, and Sean Baker.

Learn more about Italian Neorealism →

FRENCH NEW WAVE

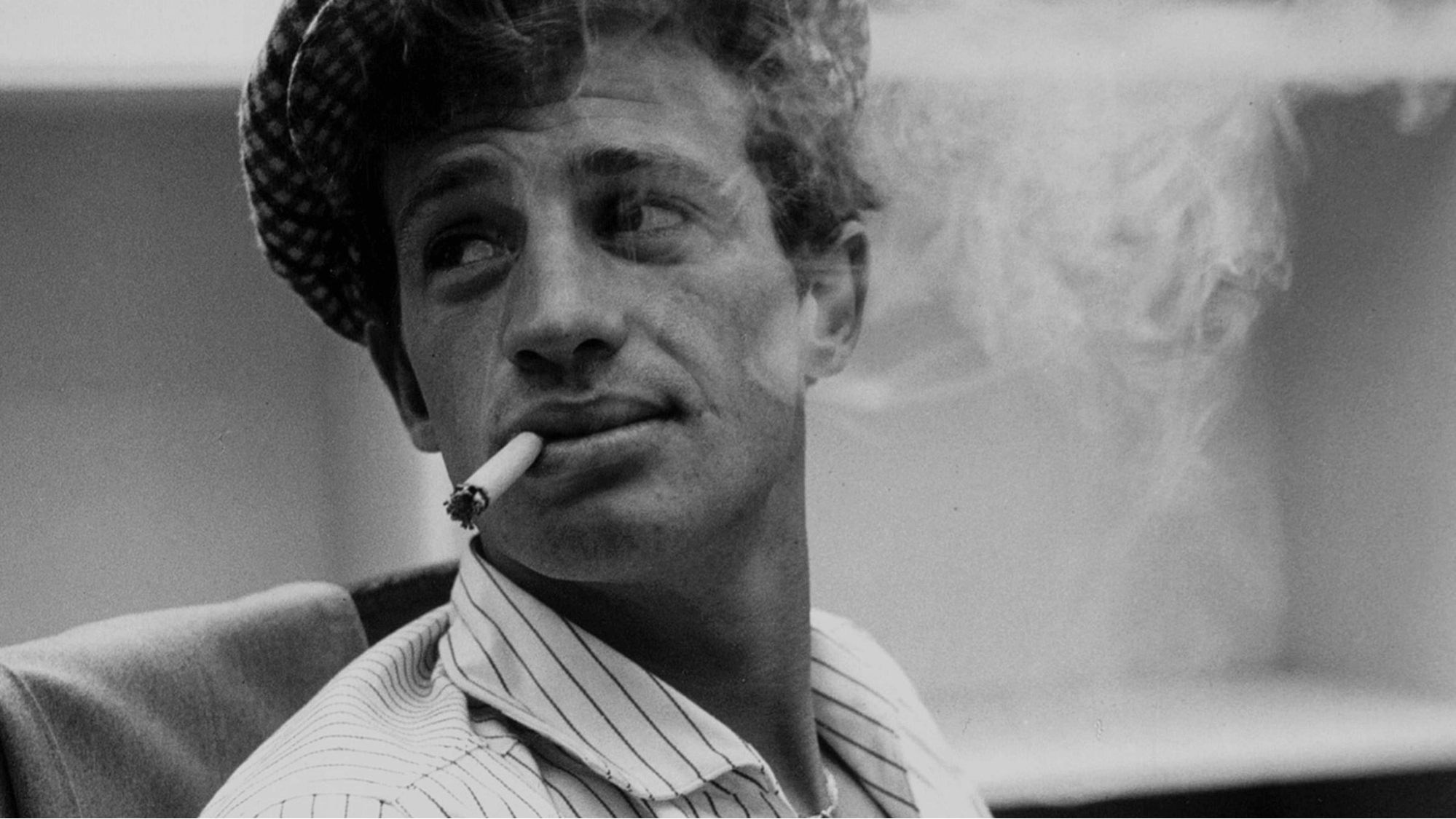

Development of Movies • Still From Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless

- French New Wave (1950s onwards) – or La Nouvelle Rogue, a French art movement popularized by critics, defined by experimental ideas – inspired by old-Hollywood and progressive editing techniques from Orson Welles and Alfred Hitchcock.

- Major French New Wave filmmakers: Jean-Luc Godard , François Truffaut , Agnes Varda.

- Major French New Wave films: The 400 Blows (1959), Breathless (1960), Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962).

The French New Wave proliferated the auteur theory , which suggests the director is the author of a movie; which makes sense considering a lot of the best French New Wave films featured minimalist narratives. Take Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless for example: the story is secondary to audio and visuals. The French New Wave was about independent filmmaking – taking a camera into the streets and making a movie by any means necessary.

Here’s a quick video on The French New Wave by The Cinema Cartography.

History of Filmmaking • Breaking the Rules With the French New Wave by The Cinema Cartography

It’s important to note that the pioneers of the French New Wave weren’t amateurs – most (but not all) were critics at Cahiers du cinéma , a respected French film magazine. Writers like Godard, Rivette, and Chabrol knew what they were doing long before they released their great works.

Other directors, like Agnes Varda and Alain Resnais, were members of the Left Bank, a somewhat more traditionalist art group. Left Bank directors tended to put more emphasis on their narratives as opposed to their Cahiers du cinéma counterparts.

The French New popularized (but did not invent) innovative filmmaking techniques like jump cuts and tracking shots . The influence of the French New Wave can be seen in music videos, existentialist cinema, and French film noir .

Learn more about the French New Wave →

Learn more about the Best French New Wave Films →

SCANDINAVIAN REVIVAL

A History of Film • Still from Ingmar Bergman’s ‘The Seventh Seal’

- Scandinavian Revival (1940s-1950s) – a filmmaking movement in Scandinavia, particularly Denmark and Sweden, defined by monochrome visuals, philosophical quandaries, and reinterpretations of religious ideals.

- Major Scandinavian Revival filmmakers: Carl Theodor Dreyer and Ingmar Bergman.

- Major Scandinavian Revival films: Day of Wrath (1943), The Seventh Seal (1957), Wild Strawberries (1957).

Swedish, Danish, and Finnish films have played an important role in cinema for more than 100 years. The Scandinavian Revival – or renaissance of Scandinavian-centric films from the 1940s-1950s – put the films of Sweden, Denmark, and Finland in front of the world stage.

Here’s a quick video on the works of the most famous Scandinavian director of all-time: Ingmar Bergman .

History of Cinema • Ingmar Bergman’s Cinema by The Criterion Collection

The influence of Scandinavian Revival can be seen in the works of Danish directors like Thomas Vinterberg and Lars von Trier , as well as countless other filmmakers around the world.

BENGALI CINEMA

History of Motion Pictures • Still from Satyajit Ray’s ‘Pather Panchali’

- Bengali Cinema – or the cinema of West Bengal; also known as Tollywood, helped develop arthouse films parallel to the mainstream Indian cinema.

- Major Bengali filmmakers: Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen.

- Major Bengali films: Pather Panchali (1955) and Bhuvan Shome (1969).

The Indian film industry is the biggest film industry in the world. Each year, India produces more than a thousand feature-films. When most people think of Indian cinema, they think of Bollywood “song and dance” masalas – but did you know the country underwent a New Wave (similar to France, Italy, and Scandinavia) after World War II? The influence of the Indian New Wave, or classic Bengali cinema, is hard to quantify; perhaps it’s better expressed by the efforts of the Academy Film Archive, Criterion Collection, and L'Immagine Ritrovata film restoration artists. Here's an introduction to one of India's greatest directors, Satyajit Ray.

Evolution of Cinema • How Satyajit Ray Directs a Movie

In 2020, Martin Scorsese said, “In the relatively short history of cinema, Satyajit Ray is one of the names that we all need to know, whose films we all need to see.” Ray is undoubtedly one of the preeminent masters of international cinema – and his name belongs in the conversation with Hitchcock, Renoir, Kurosawa, Welles, and all the other trailblazing filmmakers of the mid-20th century.

Learn more about Indian Cinema →

OTHER POST-WAR & NEW WAVE MOVEMENTS

How Has Film Changed Over Time? • Still from Akira Kurosawa’s ‘Stray Dog’

Italy, France, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, and India weren’t the only countries that underwent “New Waves” after World War II; Japan, Iran, Great Britain, and Russia had minor film revolutions as well.

In Japan, directors like Akira Kurosawa and Yasujirō Ozu introduced new filmmaking techniques to the masses; their 1940s-1950s films were great, but some filmmakers, like Hiroshi Teshigahara and Nagisa Ōshima felt they were better suited to make films about “modern” Japan.

Here’s a quick video on the Japanese New Wave from Film Studies for YouTube.

Cinema Eras • Japanese New Wave Video Essay by Film Studies for YouTube

Some cinema historians combine the Japanese New Wave with the post-war era. For simplicity’s sake, we’ll do the same: the major films of this era (1940s-1960s) include Rashomon (1950), Tokyo Story (1953), and Seven Samurai (1954).

The Iranian New Wave began about fifteen years after the end of World War II, circa 1960-onwards. Iranian cinema is an important part of Iranian culture. Here’s a quick video on Iranian cinema from BBC News.

Important Dates in Film History • Spotlight on Iran’s Film Industry via BBC News

Cinema historians widely consider Dariush Mehrjui’s The Cow (1969) to be a foundational film for the movement. Abbas Kiarostami is perhaps the most famous Iranian filmmaker of all-time. His film Close-Up (1990) is regarded as one of the greatest films ever produced in Iran.

The British New Wave was a minor film movement that was defined by kitchen-sink realism – or depictions of ordinary life. Many filmmakers of the British New Wave were critics before they were directors; and they wanted to depict the average life of Britain through a filmic eye.

Here’s a lecture on the British New Wave from Professor Ian Christie at Gresham College.

History of Filmmaking • Street-Life and New Wave British Cinema by Gresham College

The British New Wave became synonymous with Cinéma vérité (cinema of truth) over the course of its brief existence. Some of the major pictures of the movement include: Look Back in Anger (1959) and Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960).

Russian cinema is complex… probably just as complex as American cinema. We could spend 100 pages talking about Russian cinema – but that’s not the focus of this article. We already talked about Soviet Montage Theory, so let’s skip ahead to post World War II Soviet cinema.

When I think of post-war Soviet cinema, I think of one name: Andrei Tarkovsky . Tarkovsky directed internationally-renowned films like Andrei Rublev (1969), Solaris (1972), and Stalker (1979) in his brief career as the Soviet Union’s pre-eminent maestro.

Here’s a deep dive into the works of Tarkovsky by “Like Stories of Old.”

Film Industry Timeline • Praying Through Cinema – Understanding Andrei Tarkovsky by Like Stories of Old

Tarkovsky wasn’t the only great filmmaker in the post-war Soviet Union – but he was probably the best. I’d be remiss if I didn’t use this section to focus on him.

History of Film Timeline

The golden age of hollywood.

The Hollywood Golden Age began with the fall of pre-Code Hollywood (1934) and lasted until the birth of New Hollywood (1968).

- Major stars of the Hollywood Golden Age: Humphrey Bogart, Cary Grant, Katharine Hepburn, Audrey Hepburn, Elizabeth Taylor, Clark Gable, Ingrid Bergman, Henry Fonda, Kirk Douglas, Gregory Peck, Lauren Bacall, Grace Kelly, James Dean, Marlon Brando.

- Major filmmakers of the Hollywood Golden Age: Cecil B. DeMille , Orson Welles , Billy Wilder , Frank Capra , John Huston , Alfred Hitchcock , John Ford , Elia Kazan , David Lean , Joseph Manckiewicz.

Notice how many names we included? It’s ridiculous – it would be wrong to omit any of them; and still, there are probably dozens of iconic figures missing. The Hollywood Golden Age was all about stars. Stars sold pictures and the studios knew it. “Hepburn” could sell a movie every time; it didn’t matter which Hepburn – or what the movie was about.

Here’s a breakdown of the Hollywood Golden Age from Crash Course.

History of Movies • The Golden Age of Hollywood by Crash Course

There are a few sub-eras within the Hollywood Golden Age era; let’s break them down in detail.

Important Dates in Film History • Photo of MPPDA Chairman William Hays

In 1934, Chairman William Hays of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America instituted a production code that banned graphic cinematic depictions of sex, violence, and other illicit deeds.

The “Production Code” or “ Hays Code ” was responsible for the censorship of Hollywood films for 34 years.

For more on the history of Hollywood censorship and movie ratings, check out the video from Filmmaker IQ below.

How Has Film Changed Over Time? • History of Hollywood Censorship by Filmmaker IQ

The Hays Code kept cinema tame, which led to Hollywood romanticism. But it also made cinema unrealistic, which made the American public yearn for improbable outcomes. Not to mention that it set race relations back an indeterminable amount of years. The Hays Code specifically forbade miscegenation, or “the breeding of people of different races.”

Ultimately, the censorship of Hollywood films was about keeping power in the hands of people with power. It had some positive unintended outcomes – but it wasn’t worth the cost of suppression.

Learn more about the Hays Code →

Learn more about the history of movie censorship →

Film Industry Timeline • Still from Nicholas Ray’s ‘In a Lonely Place’

Film noir is a style of film that’s defined by moralistic themes, high contrast lighting, and mysterious plots. Oftentimes, film noirs feature hardboiled protagonists . It’s important to note that film noir is a style, not a film movement. As such, we won’t list “film noir directors,” but we will list some iconic examples of film noir.

Major Hollywood film noirs: The Maltese Falcon (1941), Double Indemnity (1944), Sunset Boulevard (1950).

Hollywood film noirs were inspired by classic detective fiction stories, like those of Arthur Conan Doyle and Edgar Allan Poe. Over time, film noir was adopted as a style around the world – most famously in Great Britain with Carol Reed’s The Third Man .

Here’s a video on defining film noir from Jack’s Movie Reviews.

Eras of Movies • Defining Film Noir by Jack’s Movie Reviews

We could spend another 50 pages on film noir (like many other topics in this compendium) – but instead, let’s continue on.

Learn more about film noir →

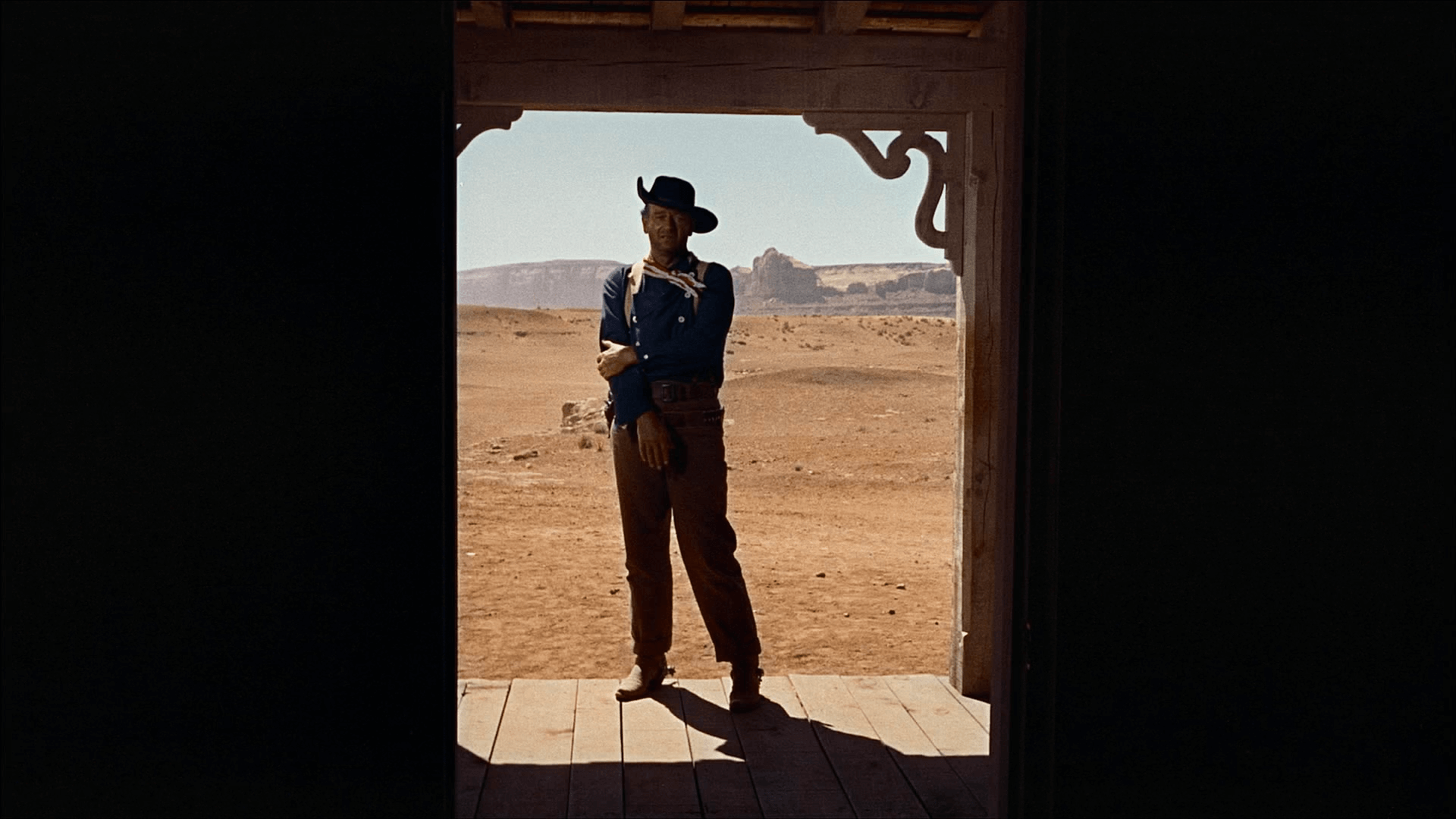

How Movies Have Changed Over Time • Still from John Ford’s ‘The Searchers’

Hollywood westerns were incredibly popular during the Golden Age. Why? Because the American people loved stories of lawlessness and expansion, dating all the way back to Erastus Beadle’s dime novels – making the western the perfect subgenre for vicarious cinema.

Major Hollywood westerns: Stagecoach (1939), High Noon (1952), The Searchers (1956).

Westerns, much like film noirs, allowed repressed audiences to feel alive at the movie theater. Remember: Hollywood films were censored during the Golden Age, which meant you couldn’t find graphic violence or pornography at the theaters. So, audiences took what they could get – which was usually film noirs and Westerns.

Here’s a video on the history of Westerns in Hollywood cinema.

Evolution of Film • Western Movies History by Ministry of Cinema

Hollywood westerns inspired a global fascination with cowboys, mercenaries, and gunslingers, directly leading to samurai cinema, spaghetti westerns, zapata westerns, and neo-westerns.

Learn more about Spaghetti Westerns →

Learn more about Neo-Westerns →

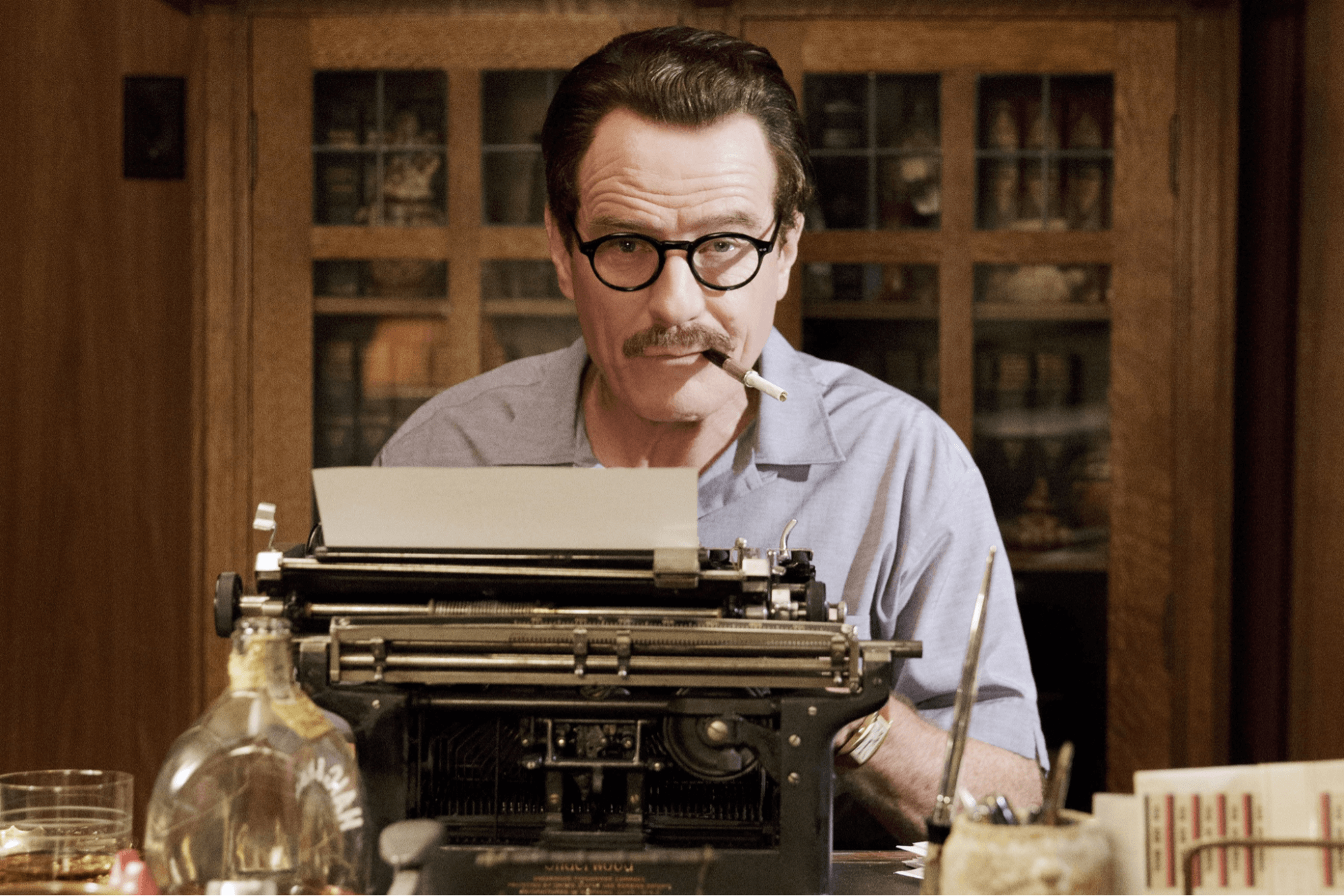

McCARTHYISM & THE BLACKLIST

How Movies Have Changed Over Time • Bryan Cranston as Blacklisted Screenwriter Dalton Trumbo

In 1947, the state of Wisconsin elected notorious fear-monger Joseph McCarthy as senator of their state. McCarthy hated free-speech – that’s not a one-sided perspective, that’s the truth. McCarthy spent his entire career demagoguing, and his legacy shows that.

In 1950, ten Hollywood screenwriters were summoned to appear before the United States Congress House of Un-American Activities, largely because of McCarthy's divisive rhetoric against communist sympathizers. The screenwriters were cited for contempt of congress and fired from their jobs, and thus, the blacklist was born.

For more on McCarthyism and the Hollywood blacklist , check out the video from Ted-Ed below.

The History of Film • McCarthyism and the Blacklist by Ted-Ed

The Hollywood blacklist derailed the careers of hundreds of writers, directors, and producers from 1950-1960. The blacklist ended when Kirk Douglas credited Dalton Trumbo – one of the most famous blacklisted screenwriters – as the screenwriter of Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus , effectively taking back control of Hollywood.

Learn more about the Hollywood Blacklist →

THE PARAMOUNT CASE

The History of Film • Paramount Studios Classic Style Logo

In 1948, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the five major motion picture studios: Paramount, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), Warner Bros., 20th Century Fox, and RKO violated the U.S. Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890.

As a result of the decision, movie studios could no longer solely create and distribute movies to their own theaters.

It may not sound important, but the Paramount Case changed everything for American cinema. Here’s a quick video on the Case and its lasting impact on Hollywood.

The History of Filmmaking • Film History 101: The Paramount Decree by Omar Rivera

The Paramount Case opened the door for international films and independent theaters. It also gave businesses more freedom to show movies outside of the MPPDA ratings system.

Evolution of Cinema

New hollywood.

Movie History • Still from Arthur Penn’s’ Bonnie and Clyde’

- New Hollywood, otherwise known as the Hollywood New Wave, introduced “the film school generation” to Hollywood. New Hollywood films are defined as larger in scope, darker in subject matter, and overtly more graphic than their Golden Age predecessors.

- Major New Hollywood filmmakers: George Lucas , Steven Spielberg , Martin Scorsese , Brian De Palma , Peter Bogdanovich, Woody Allen , Francis Ford Coppola , James Cameron .

- Major New Hollywood films: Bonnie and Clyde (1967), The Graduate (1967), Easy Rider (1969), Midnight Cowboy (1969), The Godfather (1972), American Graffiti (1973).

New Hollywood ushered American filmmaking into a new era by returning to the popular genres of the pre-Code era, such as gangster films and sex-centric films. It also marked the emergence of “film-school” directors like George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, and Martin Scorsese. It’s clear from watching New Hollywood films that the writers and directors who produced them were acutely aware of cinema history.

During this era, writers like Woody Allen employed themes of existentialist cinema found in the French New Wave and Italian Neorealism (among other movements). Directors like Martin Scorsese utilized advanced framing techniques pioneered by masters of the pre-war era.

For more on New Hollywood, check out this feature documentary based Peter Biskind's seminal book "Easy Riders, Raging Bulls."

Movie History • How New Hollywood Was Born

New Hollywood (and its immediate aftermath) produced some of the greatest films of all-time: such as The Godfather (1972), The Godfather Part II (1974), Chinatown (1974), Taxi Driver (1976), Network (1976), and Annie Hall (1977).

Somewhat tragically, New Hollywood ended with the emergence of blockbuster films – such as Jaws (1975) and Star Wars (1977) – in the mid to late 1970s.

Learn more about New Hollywood →

Eras of Movies

Dogme 95 and independent movements.

Big-budget movies dominated the movie-scene after New Hollywood ended. Suddenly, cinema became more of a spectacle than an art-form. That’s not to say movies produced during this era (1975-1995) were bad – some big-budget films, like Back to the Future (1985) and Jurassic Park (1993) were financially successful and critically acclaimed; and writer/directors like John Hughes found enormous success making studio films about seemingly mundane life.

But despite the financial prospect of making contrived studio films, some filmmakers decided to go back to their roots and make films independently, much in the vein of the artists of the French New Wave. This spirit inspired the Danish Dogme 95 movement and the American Independent movement.

Evolution of Film • Photo Still from ‘Festen’ by Thomas Vinterberg

D0gme 95 – a Danish film movement that brought filmmaking back to its primal roots: no non-diegetic sound, no superficial action, and no director credit.

Major Dogme 95 filmmakers: Thomas Vinterberg and Lars von Trier

Major Dogme 95 films: Dogme #1 – Festen (1998), Dogme #2 – The Idiots (1998), Dogme #12 – Italian for Beginners (2000).

It’s ironic that Dogme 95 , which states the director must not be credited, is perhaps best known for the fame of two of its founders: Thomas Vinterberg and Lars von Trier. Dogme 95 sought to rid cinema of extravagant special effects and challenging productions by making the filmmaking process as simple as possible. To do this, its founders created the Vows of Chastity: a ten-part manifesto for Dogme 95 filmmaking.

Check out a video on the Vows of Chastity and Dogme 95 below.

History of Cinema • Vows of Chastity – Films of Dogme 95 by FilmStruck

Ultimately, the Vows of Chastity proved too limiting for filmmakers – but their influence lives on in New Danish cinema and independent films all over the world.

Learn more about Dogme 95 →

History of Cinema • Still from Kevin Smith’s ‘Clerks’

Indie film – or late 80s, early 90s cinema produced outside of the major motion picture system – was about experimenting with new cinematic forms, pushing the Generation Next agenda, and making art by any means necessary.

Major indie filmmakers: Richard Linklater , Wes Anderson , Steven Soderbergh , Jim Jarmusch .

Major indie films: Sex, Lies, and Videotape (1989), Slacker (1990), and Bottle Rocket (1994).

The American indie movement launched the careers of a myriad of great directors. It also marked the beginning of a major decline for film. The advent of digital cameras and DVDs meant film was becoming a luxury. Conversely, it meant procuring the necessary equipment needed to make movies was easier than ever.

Indie-films introduced the idea that anybody could make movies. For better or worse, the point proved to be true. The '90s and early 2000s were littered with independently produced, scarcely funded movies. It was unrestrained, but it was also liberating.

Check out this video on no-budget filmmaking from The Royal Ocean Film Society to learn more about the indie movement.

Evolution of Cinema • Lessons for the No-Budget Feature by The Royal Ocean Film Society

The indie movement (as it was known then) ended when the major studios (like Disney and Turner) bought the independent studios (like Miramax and New Line). Today, we often refer to minimalist, low-budget movies as independent, but the truth is just about every production studio is owned by a conglomerate.

How Has the Film Industry Changed?

New distribution methods.

The current state of cinema is in flux due to a wide array of issues, including (but not limited to) the economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, the wide-adoption of new streaming services from first-party producers, i.e. Netflix, Disney, Paramount, etc., and the growth of new media forms.

Over the last few years, big-budget epics like Marvel’s The Avengers and Star Wars have performed well at the U.S. and Chinese box-office, but their success has often come at the expense of medium-budget movies; the result being a deeper lining of the pockets of exorbitantly wealthy corporations.

Still, there’s a lot of money to be made – a point perhaps best proven by the rise of the Chinese film industry. In 2020, China overtook North America as the world’s biggest box-office market, per THR. Check out a video on Hengdian, China’s largest film studio from South China Morning Report.

Movie History • Inside China’s Largest Film Studio by South China Morning Report

Movies seem to get bigger and bigger every year but the development of computer-generated-imagery and compositing techniques has given filmmakers the technology to create vast worlds in limited spaces.

So: what’s next for film? Who’s to say for certain? The future of the industry looks cloudy – but there’s definite promise on the horizon. More people have cinema-capable cameras in their pocket today than ever before. Perhaps the next great movement will take off soon.

Related Posts

- What is CinemaScope →

- When Was the Camera Invented →

- What Was the First Movie Ever Made →

100 Years of Cinematography

The history of film includes a lot more than what we went over here. In 2019, the American Society of Cinematographers celebrated 100 years of great cinematography with a list of legendary works. In our next article, we break down some of the ASC’s choices with video examples. Follow along as we look at the work of Conrad Hall, Vittorio Storaro, and more.

Up Next: Best Cinematography of All-Time →

Showcase your vision with elegant shot lists and storyboards..

Create robust and customizable shot lists. Upload images to make storyboards and slideshows.

Learn More ➜

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Pricing & Plans

- Featured On

- StudioBinder Partners

- Ultimate Guide to Call Sheets

- How to Break Down a Script (with FREE Script Breakdown Sheet)

- The Only Shot List Template You Need — with Free Download

- Managing Your Film Budget Cashflow & PO Log (Free Template)

- A Better Film Crew List Template Booking Sheet

- Best Storyboard Softwares (with free Storyboard Templates)

- Movie Magic Scheduling

- Gorilla Software

- Storyboard That

A visual medium requires visual methods. Master the art of visual storytelling with our FREE video series on directing and filmmaking techniques.

We’re in a golden age of TV writing and development. More and more people are flocking to the small screen to find daily entertainment. So how can you break put from the pack and get your idea onto the small screen? We’re here to help.

- Making It: From Pre-Production to Screen

- What is a Femme Fatale — Definition, Characteristics, Examples

- What is Method Acting — 3 Different Types Explained

- How to Make a Mood Board — A Step-by-Step Guide

- What is a Mood Board — Definition, Examples & How They Work

- How to Make a Better Shooting Schedule with a Stripboard

- 1 Pinterest

Art & Photography

Film & tv, life & culture.

The secret history of the essay film

Charting the resurgence of ‘sort of documentaries’ to celebrate chris marker, king of the essay film.

“Essay films are arguably the most innovative and popular form of filmmaking since the 1990s,” wrote Timothy Corrigan in his notable 2011 book, The Essay Film . True, perhaps, but mention of the genre to your average joe won’t spark the instant recognition of today’s romcoms, sci-fis and period dramas. The thing is, essay films have been around since the dawn of cinema: they emerged not long after the Lumière brothers recorded the first ever motion pictures of Lyonnaise factory workers in 1894, yet their definition is still ambiguous.

They are similar to documentary and non-fiction film in that they are often based in reality, using words, images and sounds to convey a message. But according to Chris Darke – co-curator of the Whitechapel Gallery’s current retrospective of the great essay filmmaker Chris Marker – it is “the personal aspect and style of address” that makes the essay film distinct. It is this flexibility that has appealed to contemporary filmmakers, permitting a fresh, nuanced viewing experience.

Geoff Andrew, a senior programmer at the BFI who helped curate last year’s landmark essay film season, explained, “they are sort of documentaries, sort of non-fiction films.” The issue is that some filmmakers try to provide an objective point of view when it is just not possible. “There’s always somebody manipulating footage and manipulating reality to present some sort of message.” Andrew continued, “So, in a way, all documentaries are essay films.”

But the essay film is particularly resurgent these days, with filmmakers like Michael Moore , Werner Herzog , and Nick Broomfield molding the genre in their own ways. Their popularity isn’t just due to incendiary topics like men getting eaten by bears as in Herzog’s Grizzly Man and high school massacres as in Moore’s Bowling for Columbine ; essay films are capable of compelling beauty. Now, with the Whitechapel Gallery ’s retrospective of the late Frenchman, Chris Marker , arguably the greatest essay filmmaker there’s ever been, we take a look at the essay film’s secret history.

1909 - D. W. Griffith ’s A Corner in Wheat

Considered by some to be the first essay film ever, A Corner in Wheat is a little subversive thorn in the side of the man. Lasting only 14 minutes, it tells the tale of a ruthless crop gambler who amasses riches by monopolising the wheat market, exploits the agricultural poor, and is promptly killed under a pile of his own grain. Think twice, greedy capitalists.

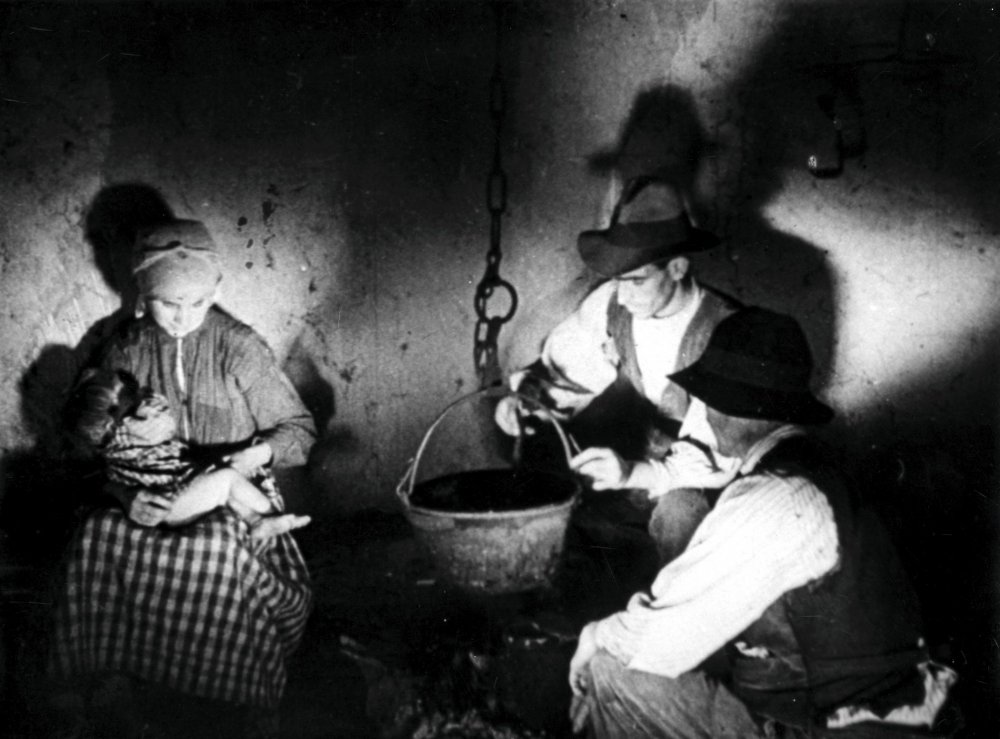

1929 - Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera

“The film drama is the opium of the people,” proclaimed Soviet film pioneer Dziga Vertov , “down with Bourgeois fairy-tale scenarios.” He was the most radical of his fellow Soviet filmmaker compatriots, and Man with a Movie Camera was his masterpiece. In it, he tried to create an “international language of cinema” through a beguiling mix of jump cuts, split screens and superimpositions. Vertov’s idea was to uncover the artifice of filmmaking, with one scene of the film depicting a cameraman inside a giant beer.

1940 - Hans Richter’s The Film Essay

The term “essay film” was originally coined by German artist Hans Richter, who wrote in his 1940 paper, The Film Essay : “The film essay enables the filmmaker to make the ‘invisible’ world of thoughts and ideas visible on the screen... The essay film produces complex thought – reflections that are not necessarily bound to reality, but can also be contradictory, irrational, and fantastic.” So while World War II was blazing away, a new cinema was born.

1982 - Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil

You know that this brilliant, freewheeling travelogue is something special when it suggests that Pac-Man is “a perfect graphic metaphor for the human condition.” It takes in anti-colonial struggles, sumo wrestling, a volcanic eruption in Iceland, the antiquities of the Vatican, Marker’s love of cats and more. An unnamed female narrates a circuitous journey from Africa to Japan, in an engaging style never seen before. Some might say he laid down a marker.

1993 - Derek Jarman’s Blue

Diagnosed with HIV and beginning to lose his eyesight, Jarman decided to turn his illness into his art. Although the premise of nothing but a dim, blue background accompanied by voiceovers for 79 minutes might not seem enthralling, it really is. Jarman recalls memories of his past lovers, and his current life of endless pill-popping, with a poignant score by Brian Eno and Simon Fisher Turner .

1998 - Jean -Luc Godard’s Histoire(s) du cinema

Comprised of hundreds of clips of films, music and poetry, this eight part series – that took over a decade to make – remained a secret seen only at a precious few film festivals thanks to the gargantuan amount of rights needed to be cleared. Histoire(s) du cinema is an epic of free association whose central theme is voyeurism, since Godard believes that cinema consists of a man looking at a woman. Harriet Andersson , topless and alluring on a beach in Ingmar Bergman ’s Monika , is one of many examples.

2004 - Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11

The most successful documentary at the US box office ever, Fahrenheit 9/11 is a prime example of the essay film’s wild popularisation (it also won the Palme d’Or at Cannes). Michael Moore ’s swipe at the Republican jugular was a classic example of the essay filmmaker’s prominence, outrightly mocking President George W. Bush and questioning the fairness of his election. Disney refused to distribute the film, and the rest is history.

2010 - Errol Morris’ Tabloid

Tabloid is the outrageous story of a former Miss Wyoming, Joyce McKinney, who was alleged to have kidnapped an American mormon missionary living in England, handcuffed him to a bed in a Devonshire cottage and made him a sex slave. The woman claimed she was saving the man from a cult, but then fleed to Canada wearing a red wig, where she posed as part of a mime troupe. As ever, Errol Morris deftly offers alternate explanations, which led to McKinney suing him after the release of the film.

2014 - Hito Steyerl’s How Not To Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educationa l

After touring galleries of the world and a recent stint at the ICA, Hito Steyerl ’s How Not To Be Seen made waves as “an art for our times”. It is a disembowelling satire that mocks the idea that it we can become invisible and have genuine privacy, in this digital age. If we want to disappear, it suggests, we should become poor, or hide in plain sight, or get “disappeared” by the authorities.

Chris Marker: A Grin Without a Cat is on until 22 June at Whitechapel Gallery

Text size: A A A

About the BFI

Strategy and policy

Press releases and media enquiries

Jobs and opportunities

Join and support

Become a Member

Become a Patron

Using your BFI Membership

Corporate support

Trusts and foundations

Make a donation

Watch films on BFI Player

BFI Southbank tickets

- Follow @bfi

Watch and discover

In this section

Watch at home on BFI Player

What’s on at BFI Southbank

What’s on at BFI IMAX

BFI National Archive

Explore our festivals

BFI film releases

Read features and reviews

Read film comment from Sight & Sound

I want to…

Watch films online

Browse BFI Southbank seasons

Book a film for my cinema

Find out about international touring programmes

Learning and training

BFI Film Academy: opportunities for young creatives

Get funding to progress my creative career

Find resources and events for teachers

Join events and activities for families

BFI Reuben Library

Search the BFI National Archive collections

Browse our education events

Use film and TV in my classroom

Read research data and market intelligence

Funding and industry

Get funding and support

Search for projects funded by National Lottery

Apply for British certification and tax relief

Industry data and insights

Inclusion in the film industry

Find projects backed by the BFI

Get help as a new filmmaker and find out about NETWORK

Read industry research and statistics

Find out about booking film programmes internationally

You are here

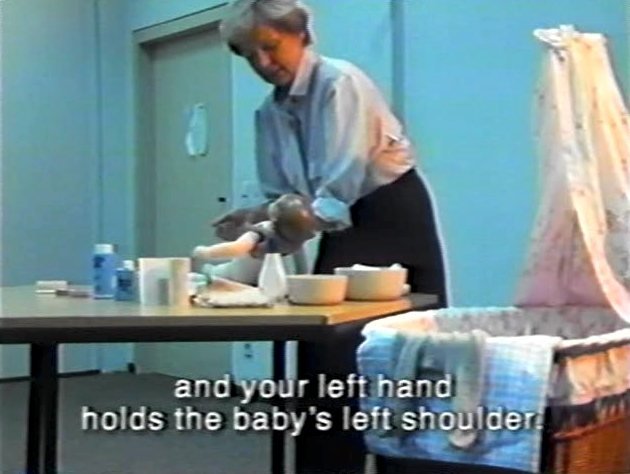

The essay film

In recent years the essay film has attained widespread recognition as a particular category of film practice, with its own history and canonical figures and texts. In tandem with a major season throughout August at London’s BFI Southbank, Sight & Sound explores the characteristics that have come to define this most elastic of forms and looks in detail at a dozen influential milestone essay films.

Andrew Tracy , Katy McGahan , Olaf Möller , Sergio Wolf , Nina Power Updated: 7 May 2019

from our August 2013 issue

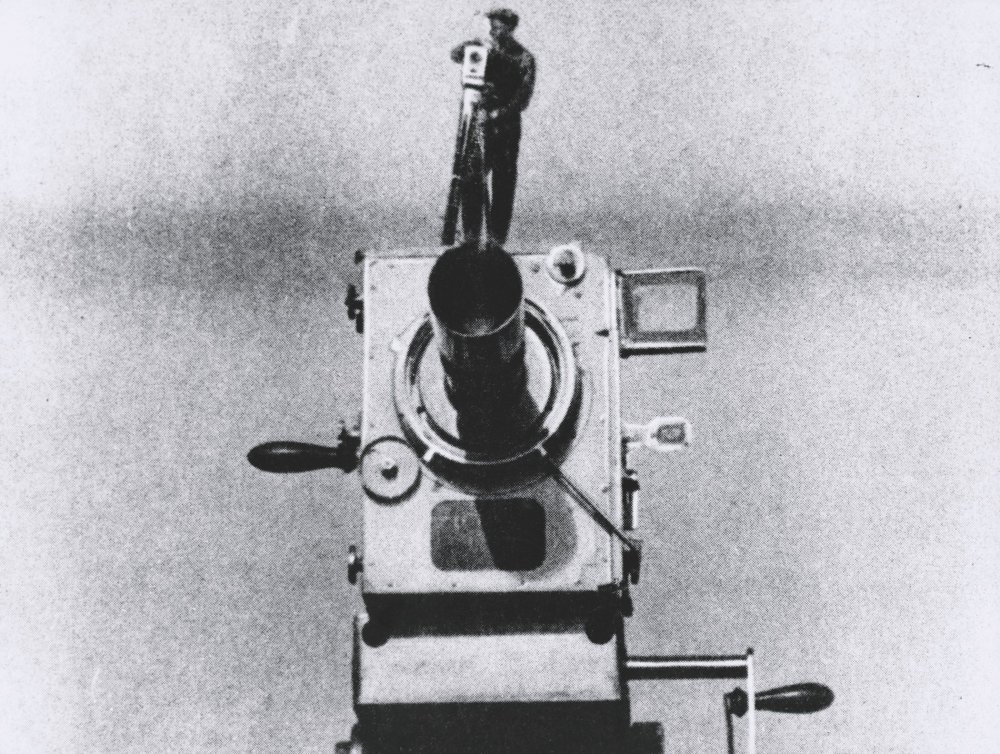

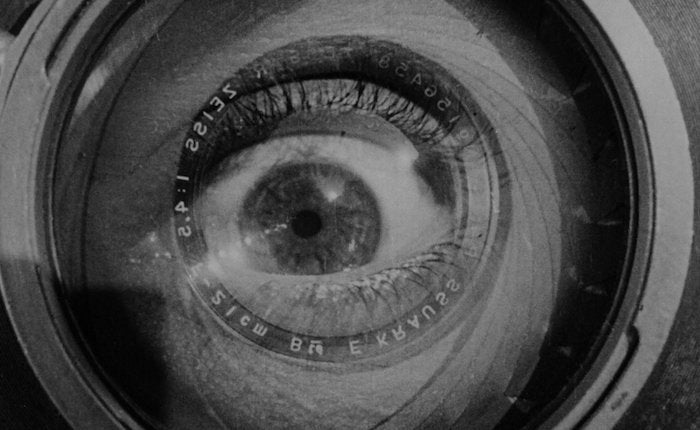

Le camera stylo? Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929)

I recently had a heated argument with a cinephile filmmaking friend about Chris Marker’s Sans soleil (1983). Having recently completed her first feature, and with such matters on her mind, my friend contended that the film’s power lay in its combinations of image and sound, irrespective of Marker’s inimitable voiceover narration. “Do you think that people who can’t understand English or French will get nothing out of the film?” she said; to which I – hot under the collar – replied that they might very well get something, but that something would not be the complete work.

The Sight & Sound Deep Focus season Thought in Action: The Art of the Essay Film runs at BFI Southbank 1-28 August 2013, with a keynote lecture by Kodwo Eshun on 1 August, a talk by writer and academic Laura Rascaroli on 27 August and a closing panel debate on 28 August.

To take this film-lovers’ tiff to a more elevated plane, what it suggests is that the essentialist conception of cinema is still present in cinephilic and critical culture, as are the difficulties of containing within it works that disrupt its very fabric. Ever since Vachel Lindsay published The Art of the Moving Picture in 1915 the quest to secure the autonomy of film as both medium and art – that ever-elusive ‘pure cinema’ – has been a preoccupation of film scholars, critics, cinephiles and filmmakers alike. My friend’s implicit derogation of the irreducible literary element of Sans soleil and her neo- Godard ian invocation of ‘image and sound’ touch on that strain of this phenomenon which finds, in the technical-functional combination of those two elements, an alchemical, if not transubstantiational, result.