- Religion and its Role in the Society Words: 1453

- Impact of Religion on Individuals, Society, and the World Words: 556

- Religion Role in the Society Words: 1090

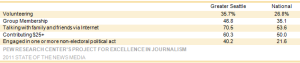

- Researching Religion in America Words: 656

- American Religion Now and Then Words: 2764

- Science and Religion: Historical Relationship Words: 2500

- Religion and Belief: Comprehensive Review Words: 2504

- Is Religion Still Vital for Society? Words: 1649

- The Relationship between Religion and Politics Words: 2254

- The Concept of Education and Religion Words: 591

The Impact of Religion in Society

Have you ever wondered how different religions influence society? In this impact of religion on society essay sample, you’ll find an answer to this and other questions about impact of religion on society. Keep reading to gain some inspiration for your paper!

Impact of Religion on Society: Essay Introduction

Impact of religion on society: essay main body, impact of religion on society: essay conclusion, works cited.

Let us start by saying that in the course of the development of human society, there were a lot of factors that influenced it and caused dramatic changes.

Among these factors, there is one that deserves special attention: religion. Points of view concerning religion are the most controversial that can be imagined, and religion is always at the center of heated arguments. Religion is a paradox because it is opposite to science, but still, it does not disappear with the development of science.

First of all, the influence of religion on society should be studied on a large scale – a historical scale. Since times immemorial, religion has occupied a considerable place in the human soul. It is characteristic for a human being to be scared by everything he does not understand, and that was the case with ancient people.

Religion was the source of information for them; they got the answers they needed from shamans and, as a result, from different religious ceremonies and interpretations of “signs” sent by gods. In this case, such a strong impact of religion may be explained by a lack of scientific knowledge.

If we move further by a historical scale, we should mention the impact of religion in medieval society, where it was predominantly negative. At that time, religion caused a number of serious problems that may even be called catastrophes: Crusades, which took the lives of hundreds of people, and the Inquisition, which murdered and deceived even more people, may be given as examples of the destructive influence of religion on society.

Moreover, it is commonly known that in medieval society, God stood in the center of the Universe, and the significance of man was enormously underestimated. Medieval people thought that a person was a mere toy in the hands of an omnipotent God.

Luckily, the situation changed with the development of knowledge, education, and science, and a man got his level of significance. However, even later, when the Dark Ages ended, religion was still very powerful in many countries. It may be proved by such a historical personality as Cardinal Richelieu, who managed to become the unofficial ruler of France (Levi).

Nowadays, in the contemporary world, there exist societies in which state and religion are separated from each other and those where they are united (Islamic countries). In the latter, the ties between state and religion may be illustrated by strict observance of the rules of the Koran, though it must be mentioned that some attempts to lessen its influence are being made.

In the USA, the First Amendment “declares freedom of religion to be a fundamental civil right of all Americans” (Neusner 316). So, it is up to people to decide what place should be occupied by religion in their life.

Religious people insist that religion helps to improve the relationship in the family, can help overcome poverty, and can help struggle against social problems like divorce, crimes, and drug addiction. Religion can strengthen a person’s self-esteem and help to avoid depression. They say that if each person is an element of society, religion helps to organize the functioning of society successfully.

One more thing to be mentioned here is the contemporary decline of religion observed by sociologists nowadays. It is seen as part of “secularization” (Herbert 4). “Secularization, in turn, is understood to be the result of modernization… as a worldwide process consisting of ‘industrialization … urbanization, mass education, bureaucratization, and communications development’” (Herbert 4).

Still, the question of secularization is a very debatable one; many sociologists question its validity, proving that religion is not in decline everywhere (Herbert 4).

In conclusion, let us say that religion has always occupied an important place in society. The attitude towards religion is a very personal matter, and everyone may treat religion in the way that he/she finds the most appropriate; unless he/she takes actions that can harm other members of society.

Herbert, David. Religion and Civil Society: Rethinking Public Religion in the Contemporary World. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2003.

Levi, Anthony. Cardinal Richelieu: And the Making of France. NY: Carroll & Graf, 2002.

Neusner, Jacob. World Religions in America: An Introduction. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2003.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2020, January 9). The Impact of Religion in Society. https://studycorgi.com/the-impact-of-religion-in-society/

"The Impact of Religion in Society." StudyCorgi , 9 Jan. 2020, studycorgi.com/the-impact-of-religion-in-society/.

StudyCorgi . (2020) 'The Impact of Religion in Society'. 9 January.

1. StudyCorgi . "The Impact of Religion in Society." January 9, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/the-impact-of-religion-in-society/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "The Impact of Religion in Society." January 9, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/the-impact-of-religion-in-society/.

StudyCorgi . 2020. "The Impact of Religion in Society." January 9, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/the-impact-of-religion-in-society/.

This paper, “The Impact of Religion in Society”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: November 9, 2023 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

17.3 Sociological Perspectives on Religion

Learning objectives.

- Summarize the major functions of religion.

- Explain the views of religion held by the conflict perspective.

- Explain the views of religion held by the symbolic interactionist perspective.

Sociological perspectives on religion aim to understand the functions religion serves, the inequality and other problems it can reinforce and perpetuate, and the role it plays in our daily lives (Emerson, Monahan, & Mirola, 2011). Table 17.1 “Theory Snapshot” summarizes what these perspectives say.

Table 17.1 Theory Snapshot

| Theoretical perspective | Major assumptions |

|---|---|

| Functionalism | Religion serves several functions for society. These include (a) giving meaning and purpose to life, (b) reinforcing social unity and stability, (c) serving as an agent of social control of behavior, (d) promoting physical and psychological well-being, and (e) motivating people to work for positive social change. |

| Conflict theory | Religion reinforces and promotes social inequality and social conflict. It helps convince the poor to accept their lot in life, and it leads to hostility and violence motivated by religious differences. |

| Symbolic interactionism | This perspective focuses on the ways in which individuals interpret their religious experiences. It emphasizes that beliefs and practices are not sacred unless people regard them as such. Once they are regarded as sacred, they take on special significance and give meaning to people’s lives. |

The Functions of Religion

Much of the work of Émile Durkheim stressed the functions that religion serves for society regardless of how it is practiced or of what specific religious beliefs a society favors. Durkheim’s insights continue to influence sociological thinking today on the functions of religion.

First, religion gives meaning and purpose to life . Many things in life are difficult to understand. That was certainly true, as we have seen, in prehistoric times, but even in today’s highly scientific age, much of life and death remains a mystery, and religious faith and belief help many people make sense of the things science cannot tell us.

Second, religion reinforces social unity and stability . This was one of Durkheim’s most important insights. Religion strengthens social stability in at least two ways. First, it gives people a common set of beliefs and thus is an important agent of socialization (see Chapter 4 “Socialization” ). Second, the communal practice of religion, as in houses of worship, brings people together physically, facilitates their communication and other social interaction, and thus strengthens their social bonds.

The communal practice of religion in a house of worship brings people together and allows them to interact and communicate. In this way religion helps reinforce social unity and stability. This function of religion was one of Émile Durkheim’s most important insights.

Erin Rempel – Worship – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

A third function of religion is related to the one just discussed. Religion is an agent of social control and thus strengthens social order . Religion teaches people moral behavior and thus helps them learn how to be good members of society. In the Judeo-Christian tradition, the Ten Commandments are perhaps the most famous set of rules for moral behavior.

A fourth function of religion is greater psychological and physical well-being . Religious faith and practice can enhance psychological well-being by being a source of comfort to people in times of distress and by enhancing their social interaction with others in places of worship. Many studies find that people of all ages, not just the elderly, are happier and more satisfied with their lives if they are religious. Religiosity also apparently promotes better physical health, and some studies even find that religious people tend to live longer than those who are not religious (Moberg, 2008). We return to this function later.

A final function of religion is that it may motivate people to work for positive social change . Religion played a central role in the development of the Southern civil rights movement a few decades ago. Religious beliefs motivated Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights activists to risk their lives to desegregate the South. Black churches in the South also served as settings in which the civil rights movement held meetings, recruited new members, and raised money (Morris, 1984).

Religion, Inequality, and Conflict

Religion has all of these benefits, but, according to conflict theory, it can also reinforce and promote social inequality and social conflict. This view is partly inspired by the work of Karl Marx, who said that religion was the “opiate of the masses” (Marx, 1964). By this he meant that religion, like a drug, makes people happy with their existing conditions. Marx repeatedly stressed that workers needed to rise up and overthrow the bourgeoisie. To do so, he said, they needed first to recognize that their poverty stemmed from their oppression by the bourgeoisie. But people who are religious, he said, tend to view their poverty in religious terms. They think it is God’s will that they are poor, either because he is testing their faith in him or because they have violated his rules. Many people believe that if they endure their suffering, they will be rewarded in the afterlife. Their religious views lead them not to blame the capitalist class for their poverty and thus not to revolt. For these reasons, said Marx, religion leads the poor to accept their fate and helps maintain the existing system of social inequality.

As Chapter 11 “Gender and Gender Inequality” discussed, religion also promotes gender inequality by presenting negative stereotypes about women and by reinforcing traditional views about their subordination to men (Klassen, 2009). A declaration a decade ago by the Southern Baptist Convention that a wife should “submit herself graciously” to her husband’s leadership reflected traditional religious belief (Gundy-Volf, 1998).

As the Puritans’ persecution of non-Puritans illustrates, religion can also promote social conflict, and the history of the world shows that individual people and whole communities and nations are quite ready to persecute, kill, and go to war over religious differences. We see this today and in the recent past in central Europe, the Middle East, and Northern Ireland. Jews and other religious groups have been persecuted and killed since ancient times. Religion can be the source of social unity and cohesion, but over the centuries it also has led to persecution, torture, and wanton bloodshed.

News reports going back since the 1990s indicate a final problem that religion can cause, and that is sexual abuse, at least in the Catholic Church. As you undoubtedly have heard, an unknown number of children were sexually abused by Catholic priests and deacons in the United States, Canada, and many other nations going back at least to the 1960s. There is much evidence that the Church hierarchy did little or nothing to stop the abuse or to sanction the offenders who were committing it, and that they did not report it to law enforcement agencies. Various divisions of the Church have paid tens of millions of dollars to settle lawsuits. The numbers of priests, deacons, and children involved will almost certainly never be known, but it is estimated that at least 4,400 priests and deacons in the United States, or about 4% of all such officials, have been accused of sexual abuse, although fewer than 2,000 had the allegations against them proven (Terry & Smith, 2006). Given these estimates, the number of children who were abused probably runs into the thousands.

Symbolic Interactionism and Religion

While functional and conflict theories look at the macro aspects of religion and society, symbolic interactionism looks at the micro aspects. It examines the role that religion plays in our daily lives and the ways in which we interpret religious experiences. For example, it emphasizes that beliefs and practices are not sacred unless people regard them as such. Once we regard them as sacred, they take on special significance and give meaning to our lives. Symbolic interactionists study the ways in which people practice their faith and interact in houses of worship and other religious settings, and they study how and why religious faith and practice have positive consequences for individual psychological and physical well-being.

The cross, Star of David, and the crescent and star are symbols of Islam, Christianity, and Judaism, respectively. The symbolic interactionist perspective emphasizes the ways in which individuals interpret their religious experiences and religious symbols.

zeevveez – Star of David Coexistence- 2 – CC BY 2.0.

Religious symbols indicate the value of the symbolic interactionist approach. A crescent moon and a star are just two shapes in the sky, but together they constitute the international symbol of Islam. A cross is merely two lines or bars in the shape of a “t,” but to tens of millions of Christians it is a symbol with deeply religious significance. A Star of David consists of two superimposed triangles in the shape of a six-pointed star, but to Jews around the world it is a sign of their religious faith and a reminder of their history of persecution.

Religious rituals and ceremonies also illustrate the symbolic interactionist approach. They can be deeply intense and can involve crying, laughing, screaming, trancelike conditions, a feeling of oneness with those around you, and other emotional and psychological states. For many people they can be transformative experiences, while for others they are not transformative but are deeply moving nonetheless.

Key Takeaways

- Religion ideally serves several functions. It gives meaning and purpose to life, reinforces social unity and stability, serves as an agent of social control, promotes psychological and physical well-being, and may motivate people to work for positive social change.

- On the other hand, religion may help keep poor people happy with their lot in life, promote traditional views about gender roles, and engender intolerance toward people whose religious faith differs from one’s own.

- The symbolic interactionist perspective emphasizes how religion affects the daily lives of individuals and how they interpret their religious experiences.

For Your Review

- Of the several functions of religion that were discussed, which function do you think is the most important? Why?

- Which of the three theoretical perspectives on religion makes the most sense to you? Explain your choice.

Emerson, M. O., Monahan, S. C., & Mirola, W. A. (2011). Religion matters: What sociology teaches us about religion in our world . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Gundy-Volf, J. (1998, September–October). Neither biblical nor just: Southern Baptists and the subordination of women. Sojourners , 12–13.

Klassen, P. (Ed.). (2009). Women and religion . New York, NY: Routledge.

Marx, K. (1964). Karl Marx: Selected writings in sociology and social philosophy (T. B. Bottomore, Trans.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Moberg, D. O. (2008). Spirituality and aging: Research and implications. Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging, 20 , 95–134.

Morris, A. (1984). The origins of the civil rights movement: Black communities organizing for change . New York, NY: Free Press.

Terry, K., & Smith, M. L. (2006). The nature and scope of sexual abuse of minors by Catholic priests and deacons in the United States: Supplementary data analysis . Washington, DC: United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.

Sociology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Communication and Culture

- Communication and Social Change

- Communication and Technology

- Communication Theory

- Critical/Cultural Studies

- Gender (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Studies)

- Health and Risk Communication

- Intergroup Communication

- International/Global Communication

- Interpersonal Communication

- Journalism Studies

- Language and Social Interaction

- Mass Communication

- Media and Communication Policy

- Organizational Communication

- Political Communication

- Rhetorical Theory

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Religion, culture, and communication.

- Stephen M. Croucher , Stephen M. Croucher School of Communication, Journalism, and Marketing, Massey Business School, Massey University

- Cheng Zeng , Cheng Zeng Department of Communication, University of Jyväskylä

- Diyako Rahmani Diyako Rahmani Department of Communication, University of Jyväskylä

- and Mélodine Sommier Mélodine Sommier School of History, Culture, and Communication, Eramus University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.166

- Published online: 25 January 2017

Religion is an essential element of the human condition. Hundreds of studies have examined how religious beliefs mold an individual’s sociology and psychology. In particular, research has explored how an individual’s religion (religious beliefs, religious denomination, strength of religious devotion, etc.) is linked to their cultural beliefs and background. While some researchers have asserted that religion is an essential part of an individual’s culture, other researchers have focused more on how religion is a culture in itself. The key difference is how researchers conceptualize and operationalize both of these terms. Moreover, the influence of communication in how individuals and communities understand, conceptualize, and pass on religious and cultural beliefs and practices is integral to understanding exactly what religion and culture are.

It is through exploring the relationships among religion, culture, and communication that we can best understand how they shape the world in which we live and have shaped the communication discipline itself. Furthermore, as we grapple with these relationships and terms, we can look to the future and realize that the study of religion, culture, and communication is vast and open to expansion. Researchers are beginning to explore the influence of mediation on religion and culture, how our globalized world affects the communication of religions and cultures, and how interreligious communication is misunderstood; and researchers are recognizing the need to extend studies into non-Christian religious cultures.

- communication

- intercultural communication

Intricate Relationships among Religion, Communication, and Culture

Compiling an entry on the relationships among religion, culture, and communication is not an easy task. There is not one accepted definition for any of these three terms, and research suggests that the connections among these concepts are complex, to say the least. Thus, this article attempts to synthesize the various approaches to these three terms and integrate them. In such an endeavor, it is impossible to discuss all philosophical and paradigmatic debates or include all disciplines.

It is difficult to define religion from one perspective and with one encompassing definition. “Religion” is often defined as the belief in or the worship of a god or gods. Geertz ( 1973 ) defined a religion as

(1) a system which acts to (2) establish powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in men by (3) formulating conceptions of a general order of existence and (4) clothing these conceptions with such an aura of factuality that (5) the moods and motivations seem uniquely realistic. (p. 90)

It is essential to recognize that religion cannot be understood apart from the world in which it takes place (Marx & Engels, 1975 ). To better understand how religion relates to and affects culture and communication, we should first explore key definitions, philosophies, and perspectives that have informed how we currently look at religion. In particular, the influences of Karl Marx, Max Weber, Emile Durkheim, and Georg Simmel are discussed to further understand the complexity of religion.

Karl Marx ( 1818–1883 ) saw religion as descriptive and evaluative. First, from a descriptive point of view, Marx believed that social and economic situations shape how we form and regard religions and what is religious. For Marx, the fact that people tend to turn to religion more when they are facing economic hardships or that the same religious denomination is practiced differently in different communities would seem perfectly logical. Second, Marx saw religion as a form of alienation (Marx & Engels, 1975 ). For Marx, the notion that the Catholic Church, for example, had the ability or right to excommunicate an individual, and thus essentially exclude them from the spiritual community, was a classic example of exploitation and domination. Such alienation and exploitation was later echoed in the works of Friedrich Nietzsche ( 1844–1900 ), who viewed organized religion as society and culture controlling man (Nietzsche, 1996 ).

Building on Marxist thinking, Weber ( 1864–1920 ) stressed the multicausality of religion. Weber ( 1963 ) emphasized three arguments regarding religion and society: (1) how a religion relates to a society is contingent (it varies); (2) the relationship between religion and society can only be examined in its cultural and historical context; and (3) the relationship between society and religion is slowly eroding. Weber’s arguments can be applied to Catholicism in Europe. Until the Protestant Reformation of the 15th and 16th centuries, Catholicism was the dominant religious ideology on the European continent. However, since the Reformation, Europe has increasingly become more Protestant and less Catholic. To fully grasp why many Europeans gravitate toward Protestantism and not Catholicism, we must consider the historical and cultural reasons: the Reformation, economics, immigration, politics, etc., that have all led to the majority of Europeans identifying as Protestant (Davie, 2008 ). Finally, even though the majority of Europeans identify as Protestant, secularism (separation of church and state) is becoming more prominent in Europe. In nations like France, laws are in place that officially separate the church and state, while in Northern Europe, church attendance is low, and many Europeans who identify as Protestant have very low religiosity (strength of religious devotion), focusing instead on being secularly religious individuals. From a Weberian point of view, the links among religion, history, and culture in Europe explain the decline of Catholicism, the rise of Protestantism, and now the rise of secularism.

Emile Durkheim ( 1858–1917 ) focused more on how religion performs a necessary function; it brings people and society together. Durkheim ( 1976 ) thus defined a religion as

a unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things, that is to say, things which are set apart and forbidden—beliefs and practices which unite into one single moral community called a Church, all those who adhere to them. (p. 47)

From this perspective, religion and culture are inseparable, as beliefs and practices are uniquely cultural. For example, religious rituals (one type of practice) unite believers in a religion and separate nonbelievers. The act of communion, or the sharing of the Eucharist by partaking in consecrated bread and wine, is practiced by most Christian denominations. However, the frequency of communion differs extensively, and the ritual is practiced differently based on historical and theological differences among denominations.

Georg Simmel ( 1858–1918 ) focused more on the fluidity and permanence of religion and religious life. Simmel ( 1950 ) believed that religious and cultural beliefs develop from one another. Moreover, he asserted that religiosity is an essential element to understand when examining religious institutions and religion. While individuals may claim to be part of a religious group, Simmel asserted that it was important to consider just how religious the individuals were. In much of Europe, religiosity is low: Germany 34%, Sweden 19%, Denmark 42%, the United Kingdom 30%, the Czech Republic 23%, and The Netherlands 26%, while religiosity is relatively higher in the United States (56%), which is now considered the most religious industrialized nation in the world ( Telegraph Online , 2015 ). The decline of religiosity in parts of Europe and its rise in the U.S. is linked to various cultural, historical, and communicative developments that will be further discussed.

Combining Simmel’s ( 1950 ) notion of religion with Geertz’s ( 1973 ) concept of religion and a more basic definition (belief in or the worship of a god or gods through rituals), it is clear that the relationship between religion and culture is integral and symbiotic. As Clark and Hoover ( 1997 ) noted, “culture and religion are inseparable” and “religion is an important consideration in theories of culture and society” (p. 17).

Outside of the Western/Christian perception of religion, Buddhist scholars such as Nagarajuna present a relativist framework to understand concepts like time and causality. This framework is distinct from the more Western way of thinking, in that notions of present, past, and future are perceived to be chronologically distorted, and the relationship between cause and effect is paradoxical (Wimal, 2007 ). Nagarajuna’s philosophy provides Buddhism with a relativist, non-solid dependent, and non-static understanding of reality (Kohl, 2007 ). Mulla Sadra’s philosophy explored the metaphysical relationship between the created universe and its singular creator. In his philosophy, existence takes precedence over essence, and any existing object reflects a part of the creator. Therefore, every devoted person is obliged to know themselves as the first step to knowing the creator, which is the ultimate reason for existence. This Eastern perception of religion is similar to that of Nagarajuna and Buddhism, as they both include the paradoxical elements that are not easily explained by the rationality of Western philosophy. For example, the god, as Mulla Sadra defines it, is beyond definition, description, and delamination, yet it is absolutely simple and unique (Burrell, 2013 ).

How researchers define and study culture varies extensively. For example, Hall ( 1989 ) defined culture as “a series of situational models for behavior and thought” (p. 13). Geertz ( 1973 ), building on the work of Kluckhohn ( 1949 ), defined culture in terms of 11 different aspects:

(1) the total way of life of a people; (2) the social legacy the individual acquires from his group; (3) a way of thinking, feeling, and believing; (4) an abstraction from behavior; (5) a theory on the part of the anthropologist about the way in which a group of people in fact behave; (6) a storehouse of pooled learning; (7) a set of standardized orientations to recurrent problems; (8) learned behavior; (9) a mechanism for the normative regulation of behavior; (10) a set of techniques for adjusting both to the external environment and to other men; (11) a precipitate of history. (Geertz, 1973 , p. 5)

Research on culture is divided between an essentialist camp and a constructivist camp. The essentialist view regards culture as a concrete and fixed system of symbols and meanings (Holiday, 1999 ). An essentialist approach is most prevalent in linguistic studies, in which national culture is closely linked to national language. Regarding culture as a fluid concept, constructionist views of culture focus on how it is performed and negotiated by individuals (Piller, 2011 ). In this sense, “culture” is a verb rather than a noun. In principle, a non-essentialist approach rejects predefined national cultures and uses culture as a tool to interpret social behavior in certain contexts.

Different approaches to culture influence significantly how it is incorporated into communication studies. Cultural communication views communication as a resource for individuals to produce and regulate culture (Philipsen, 2002 ). Constructivists tend to perceive culture as a part of the communication process (Applegate & Sypher, 1988 ). Cross-cultural communication typically uses culture as a national boundary. Hofstede ( 1991 ) is probably the most popular scholar in this line of research. Culture is thus treated as a theoretical construct to explain communication variations across cultures. This is also evident in intercultural communication studies, which focus on misunderstandings between individuals from different cultures.

Religion, Community, and Culture

There is an interplay among religion, community, and culture. Community is essentially formed by a group of people who share common activities or beliefs based on their mutual affect, loyalty, and personal concerns. Participation in religious institutions is one of the most dominant community engagements worldwide. Religious institutions are widely known for creating a sense of community by offering various material and social supports for individual followers. In addition, the role that religious organizations play in communal conflicts is also crucial. As religion deals with the ultimate matters of life, the differences among different religious beliefs are virtually impossible to settle. Although a direct causal relationship between religion and violence is not well supported, religion is, nevertheless, commonly accepted as a potential escalating factor in conflicts. Currently, religious conflicts are on the rise, and they are typically more violent, long-lasting, and difficult to resolve. In such cases, local religious organizations, places facilitating collective actions in the community, are extremely vital, as they can either preach peace or stir up hatred and violence. The peace impact of local religious institutions has been largely witnessed in India and Indonesia where conflicts are solved at the local level before developing into communal violence (De Juan, Pierskalla, & Vüllers, 2015 ).

While religion affects cultures (Beckford & Demerath, 2007 ), it itself is also affected by culture, as religion is an essential layer of culture. For example, the growth of individualism in the latter half of the 20th century has been coincident with the decline in the authority of Judeo-Christian institutions and the emergence of “parachurches” and more personal forms of prayer (Hoover & Lundby, 1997 ). However, this decline in the authority of the religious institutions in modernized society has not reduced the important role of religion and spirituality as one of the main sources of calm when facing painful experiences such as death, suffering, and loss.

When cultural specifications, such as individualism and collectivism, have been attributed to religion, the proposed definitions and functions of religion overlap with definitions of culture. For example, researchers often combine religious identification (Jewish, Christian, Muslim, etc.) with cultural dimensions (Hofstede, 1991 ) like individualism/collectivism to understand and compare cultural differences. Such combinations for comparison and analytical purposes demonstrate how religion and religious identification in particular are often relegated to a micro-level variable, when in fact the true relationship between an individual’s religion and culture is inseparable.

Religion as Part of Culture in Communication Studies

Religion as a part of culture has been linked to numerous communication traits and behaviors. Specifically, religion has been linked with media use and preferences (e.g., Stout & Buddenbaum, 1996 ), health/medical decisions and communication about health-related issues (Croucher & Harris, 2012 ), interpersonal communication (e.g., Croucher, Faulkner, Oommen, & Long, 2012b ), organizational behaviors (e.g., Garner & Wargo, 2009 ), and intercultural communication traits and behaviors (e.g., Croucher, Braziunaite, & Oommen, 2012a ). In media and religion scholarship, researchers have shown how religion as a cultural variable has powerful effects on media use, preferences, and gratifications. The research linking media and religion is vast (Stout & Buddenbaum, 1996 ). This body of research has shown how “religious worldviews are created and sustained in ongoing social processes in which information is shared” (Stout & Buddenbaum, 1996 , pp. 7–8). For example, religious Christians are more likely to read newspapers, while religious individuals are less likely to have a favorable opinion of the internet (Croucher & Harris, 2012 ), and religious individuals (who typically attend religious services and are thus integrated into a religious community) are more likely to read media produced by the religious community (Davie, 2008 ).

Research into health/medical decisions and communication about health-related issues is also robust. Research shows how religion, specifically religiosity, promotes healthier living and better decision-making regarding health and wellbeing (Harris & Worley, 2012 ). For example, a religious (or spiritual) approach to cancer treatment can be more effective than a secular approach (Croucher & Harris, 2012 ), religious attendance promotes healthier living, and people with HIV/AIDS often turn to religion for comfort as well. These studies suggest the significance of religion in health communication and in our health.

Research specifically examining the links between religion and interpersonal communication is not as vast as the research into media, health, and religion. However, this slowly growing body of research has explored areas such as rituals, self-disclosure (Croucher et al., 2012b ), and family dynamics (Davie, 2008 ), to name a few.

The role of religion in organizations is well studied. Overall, researchers have shown how religious identification and religiosity influence an individual’s organizational behavior. For example, research has shown that an individual’s religious identification affects levels of organizational dissent (Croucher et al., 2012a ). Garner and Wargo ( 2009 ) further showed that organizational dissent functions differently in churches than in nonreligious organizations. Kennedy and Lawton ( 1998 ) explored the relationships between religious beliefs and perceptions about business/corporate ethics and found that individuals with stronger religious beliefs have stricter ethical beliefs.

Researchers are increasingly looking at the relationships between religion and intercultural communication. Researchers have explored how religion affects numerous communication traits and behaviors and have shown how religious communities perceive and enact religious beliefs. Antony ( 2010 ), for example, analyzed the bindi in India and how the interplay between religion and culture affects people’s acceptance of it. Karniel and Lavie-Dinur ( 2011 ) showed how religion and culture influence how Palestinian Arabs are represented on Israeli television. Collectively, the intercultural work examining religion demonstrates the increasing importance of the intersection between religion and culture in communication studies.

Collectively, communication studies discourse about religion has focused on how religion is an integral part of an individual’s culture. Croucher et al. ( 2016 ), in a content analysis of communication journal coverage of religion and spirituality from 2002 to 2012 , argued that the discourse largely focuses on religion as a cultural variable by identifying religious groups as variables for comparative analysis, exploring “religious” or “spiritual” as adjectives to describe entities (religious organizations), and analyzing the relationships between religious groups in different contexts. Croucher and Harris ( 2012 ) asserted that the discourse about religion, culture, and communication is still in its infancy, though it continues to grow at a steady pace.

Future Lines of Inquiry

Research into the links among religion, culture, and communication has shown the vast complexities of these terms. With this in mind, there are various directions for future research/exploration that researchers could take to expand and benefit our practical understanding of these concepts and how they relate to one another. Work should continue to define these terms with a particular emphasis on mediation, closely consider these terms in a global context, focus on how intergroup dynamics influence this relationship, and expand research into non-Christian religious cultures.

Additional definitional work still needs to be done to clarify exactly what is meant by “religion,” “culture,” and “communication.” Our understanding of these terms and relationships can be further enhanced by analyzing how forms of mass communication mediate each other. Martin-Barbero ( 1993 ) asserted that there should be a shift from media to mediations as multiple opposing forces meet in communication. He defined mediation as “the articulations between communication practices and social movements and the articulation of different tempos of development with the plurality of cultural matrices” (p. 187). Religions have relied on mediations through various media to communicate their messages (oral stories, print media, radio, television, internet, etc.). These media share religious messages, shape the messages and religious communities, and are constantly changing. What we find is that, as media sophistication develops, a culture’s understandings of mediated messages changes (Martin-Barbero, 1993 ). Thus, the very meanings of religion, culture, and communication are transitioning as societies morph into more digitally mediated societies. Research should continue to explore the effects of digital mediation on our conceptualizations of religion, culture, and communication.

Closely linked to mediation is the need to continue extending our focus on the influence of globalization on religion, culture, and communication. It is essential to study the relationships among culture, religion, and communication in the context of globalization. In addition to trading goods and services, people are increasingly sharing ideas, values, and beliefs in the modern world. Thus, globalization not only leads to technological and socioeconomic changes, but also shapes individuals’ ways of communicating and their perceptions and beliefs about religion and culture. While religion represents an old way of life, globalization challenges traditional meaning systems and is often perceived as a threat to religion. For instance, Marx and Weber both asserted that modernization was incompatible with tradition. But, in contrast, globalization could facilitate religious freedom by spreading the idea of freedom worldwide. Thus, future work needs to consider the influence of globalization to fully grasp the interrelationships among religion, culture, and communication in the world.

A review of the present definitions of religion in communication research reveals that communication scholars approach religion as a holistic, total, and unique institution or notion, studied from the viewpoint of different communication fields such as health, intercultural, interpersonal, organizational communication, and so on. However, this approach to communication undermines the function of a religion as a culture and also does not consider the possible differences between religious cultures. For example, religious cultures differ in their levels of individualism and collectivism. There are also differences in how religious cultures interact to compete for more followers and territory (Klock, Novoa, & Mogaddam, 2010 ). Thus, localization is one area of further research for religion communication studies. This line of study best fits in the domain of intergroup communication. Such an approach will provide researchers with the opportunity to think about the roles that interreligious communication can play in areas such as peacemaking processes (Klock et al., 2010 ).

Academic discourse about religion has focused largely on Christian denominations. In a content analysis of communication journal discourse on religion and spirituality, Croucher et al. ( 2016 ) found that the terms “Christian” or “Christianity” appeared in 9.56% of all articles, and combined with other Christian denominations (Catholicism, Evangelism, Baptist, Protestantism, and Mormonism, for example), appeared in 18.41% of all articles. Other religious cultures (denominations) made up a relatively small part of the overall academic discourse: Islam appeared in 6.8%, Judaism in 4.27%, and Hinduism in only 0.96%. Despite the presence of various faiths in the data, the dominance of Christianity and its various denominations is incontestable. Having religions unevenly represented in the academic discourse is problematic. This highly unbalanced representation presents a biased picture of religious practices. It also represents one faith as being the dominant faith and others as being minority religions in all contexts.

Ultimately, the present overview, with its focus on religion, culture, and communication points to the undeniable connections among these concepts. Religion and culture are essential elements of humanity, and it is through communication, that these elements of humanity are mediated. Whether exploring these terms in health, interpersonal, intercultural, intergroup, mass, or other communication contexts, it is evident that understanding the intersection(s) among religion, culture, and communication offers vast opportunities for researchers and practitioners.

Further Reading

The references to this article provide various examples of scholarship on religion, culture, and communication. The following list includes some critical pieces of literature that one should consider reading if interested in studying the relationships among religion, culture, and communication.

- Allport, G. W. (1950). Individual and his religion: A psychological interpretation . New York: Macmillan.

- Campbell, H. A. (2010). When religion meets new media . New York: Routledge.

- Cheong, P. H. , Fischer-Nielson, P. , Gelfgren, S. , & Ess, C. (Eds.). (2012). Digital religion, social media and culture: Perspectives, practices and futures . New York: Peter Lang.

- Cohen, A. B. , & Hill, P. C. (2007). Religion as culture: Religious individualism and collectivism among American Catholics, Jews, and Protestants . Journal of Personality , 75 , 709–742.

- Coomaraswamy, A. K. (2015). Hinduism and buddhism . New Delhi: Munshiram Monoharlal Publishers.

- Coomaraswamy, A. K. (2015). A new approach to the Vedas: Essays in translation and exegesis . Philadelphia: Coronet Books.

- Harris, T. M. , Parrott, R. , & Dorgan, K. A. (2004). Talking about human genetics within religious frameworks . Health Communication , 16 , 105–116.

- Hitchens, C. (2007). God is not great . New York: Hachette.

- Hoover, S. M. (2006). Religion in the media age (media, religion and culture) . New York: Routledge.

- Lundby, K. , & Hoover, S. M. (1997). Summary remarks: Mediated religion. In S. M. Hoover & K. Lundby (Eds.), Rethinking media, religion, and culture (pp. 298–309). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Mahan, J. H. (2014). Media, religion and culture: An introduction . New York: Routledge.

- Parrott, R. (2004). “Collective amnesia”: The absence of religious faith and spirituality in health communication research and practice . Journal of Health Communication , 16 , 1–5.

- Russell, B. (1957). Why I am not a Christian . New York: Touchstone.

- Sarwar, G. (2001). Islam: Beliefs and teachings (5th ed.). Tigard, OR: Muslim Educational Trust.

- Stout, D. A. (2011). Media and religion: Foundations of an emerging field . New York: Routledge.

- Antony, M. G. (2010). On the spot: Seeking acceptance and expressing resistance through the Bindi . Journal of International and Intercultural Communication , 3 , 346–368.

- Beckford, J. A. , & Demerath, N. J. (Eds.). (2007). The SAGE handbook of the sociology of religion . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Burrell, D. B. (2013). The triumph of mercy: Philosophy and scripture in Mulla Sadra—By Mohammed Rustom . Modern Theology , 29 , 413–416.

- Clark, A. S. , & Hoover, S. M. (1997). At the intersection of media, culture, and religion. In S. M. Hoover , & K. Lundby (Eds.), Rethinking media, religion, and culture (pp. 15–36). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Croucher, S. M. , Braziunaite, R. , & Oommen, D. (2012a). The effects of religiousness and religious identification on organizational dissent. In S. M. Croucher , & T. M. Harris (Eds.), Religion and communication: An anthology of extensions in theory, research, and method (pp. 69–79). New York: Peter Lang.

- Croucher, S. M. , Faulkner , Oommen, D. , & Long, B. (2012b). Demographic and religious differences in the dimensions of self-disclosure among Hindus and Muslims in India . Journal of Intercultural Communication Research , 39 , 29–48.

- Croucher, S. M. , & Harris, T. M. (Eds.). (2012). Religion and communication: An anthology of extensions in theory, research, & method . New York: Peter Lang.

- Croucher, S. M. , Sommier, M. , Kuchma, A. , & Melnychenko, V. (2016). A content analysis of the discourses of “religion” and “spirituality” in communication journals: 2002–2012. Journal of Communication and Religion , 38 , 42–79.

- Davie, G. (2008). The sociology of religion . Los Angeles: SAGE.

- De Juan, A. , Pierskalla, J. H. , & Vüllers, J. (2015). The pacifying effects of local religious institutions: An analysis of communal violence in Indonesia . Political Research Quarterly , 68 , 211–224.

- Durkheim, E. (1976). The elementary forms of religious life . London: Harper Collins.

- Garner, J. T. , & Wargo, M. (2009). Feedback from the pew: A dual-perspective exploration of organizational dissent in churches. Journal of Communication & Religion , 32 , 375–400.

- Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays by Clifford Geertz . New York: Basic Books.

- Hall, E. T. (1989). Beyond culture . New York: Anchor Books.

- Harris, T. M. , & Worley, T. R. (2012). Deconstructing lay epistemologies of religion within health communication research. In S. M. Croucher , & T. M. Harris (Eds.), Religion & communication: An anthology of extensions in theory, research, and method (pp. 119–136). New York: Peter Lang.

- Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind . London: McGraw-Hill.

- Holiday, A. (1999). Small culture . Applied Linguistics , 20 , 237–264.

- Hoover, S. M. , & Lundby, K. (1997). Introduction. In S. M. Hoover & K. Lundby (Eds.), Rethinking media, religion, and culture (pp. 3–14). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Karniel, Y. , & Lavie-Dinur, A. (2011). Entertainment and stereotype: Representation of the Palestinian Arab citizens of Israel in reality shows on Israeli television . Journal of Intercultural Communication Research , 40 , 65–88.

- Kennedy, E. J. , & Lawton, L. (1998). Religiousness and business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics , 17 , 175–180.

- Klock, J. , Novoa, C. , & Mogaddam, F. M. (2010). Communication across religions. In H. Giles , S. Reid , & J. Harwood (Eds.), The dynamics of intergroup communication (pp. 77–88). New York: Peter Lang

- Kluckhohn, C. (1949). Mirror for man: The relation of anthropology to modern life . Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Kohl, C. T. (2007). Buddhism and quantum physics . Contemporary Buddhism , 8 , 69–82.

- Mapped: These are the world’s most religious countries . (April 13, 2015). Telegraph Online .

- Martin-Barbero, J. (1993). Communication, culture and hegemony: From the media to the mediations . London: SAGE.

- Marx, K. , & Engels, F. (1975). Collected works . London: Lawrence and Wishart.

- Nietzsche, F. (1996). Human, all too human: A book for free spirits . R. J. Hollingdale (Trans.). Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

- Piller, I. (2011). Intercultural communication: A critical introduction . Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Philipsen, G. (2002). Cultural communication. In W. B. Gudykunst (Ed.), Cross-cultural and intercultural communication (pp. 35–51). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Simmel, G. (1950). The sociology of Georg Simmel . K. Wolff (Trans.). Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

- Stout, D. A. , & Buddenbaum, J. M. (Eds.). (1996). Religion and mass media: Audiences and adaptations . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Weber, M. (1963). The sociology of religion . London: Methuen.

- Wimal, D. (2007). Nagarjuna and modern communication theory. China Media Research , 3 , 34–41.

- Applegate, J. , & Sypher, H. (1988). A constructivist theory of communication and culture. In Y. Y. Kim & W. B. Gudykunst (Eds.), Theories of intercultural communication (pp. 41-65). Newbury Park, CA: SAGE.

Related Articles

- Christianity as Public Religion in the Post-Secular 21st Century

- Legal Interpretations of Freedom of Expression and Blasphemy

- Public Culture

- Communicating Religious Identities

- Religion and Journalism

- Global Jihad and International Media Use

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Communication. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 05 September 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [195.158.225.230]

- 195.158.225.230

Character limit 500 /500

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- Americans Have Positive Views About Religion’s Role in Society, but Want It Out of Politics

Most say religion is losing influence in American life

Table of contents.

- 1. Many in U.S. see religious organizations as forces for good, but prefer them to stay out of politics

- 2. Most congregants trust clergy to give advice about religious issues, fewer trust clergy on personal matters

- 3. Americans trust both religious and nonreligious people, but most rarely discuss religion with family or friends

- Acknowledgments

- Methodology

A large majority of Americans feel that religion is losing influence in public life, according to a 2019 Pew Research Center survey. While some say this is a good thing, many more view it as a negative development, reflecting the broad tendency of Americans to see religion as a positive force in society.

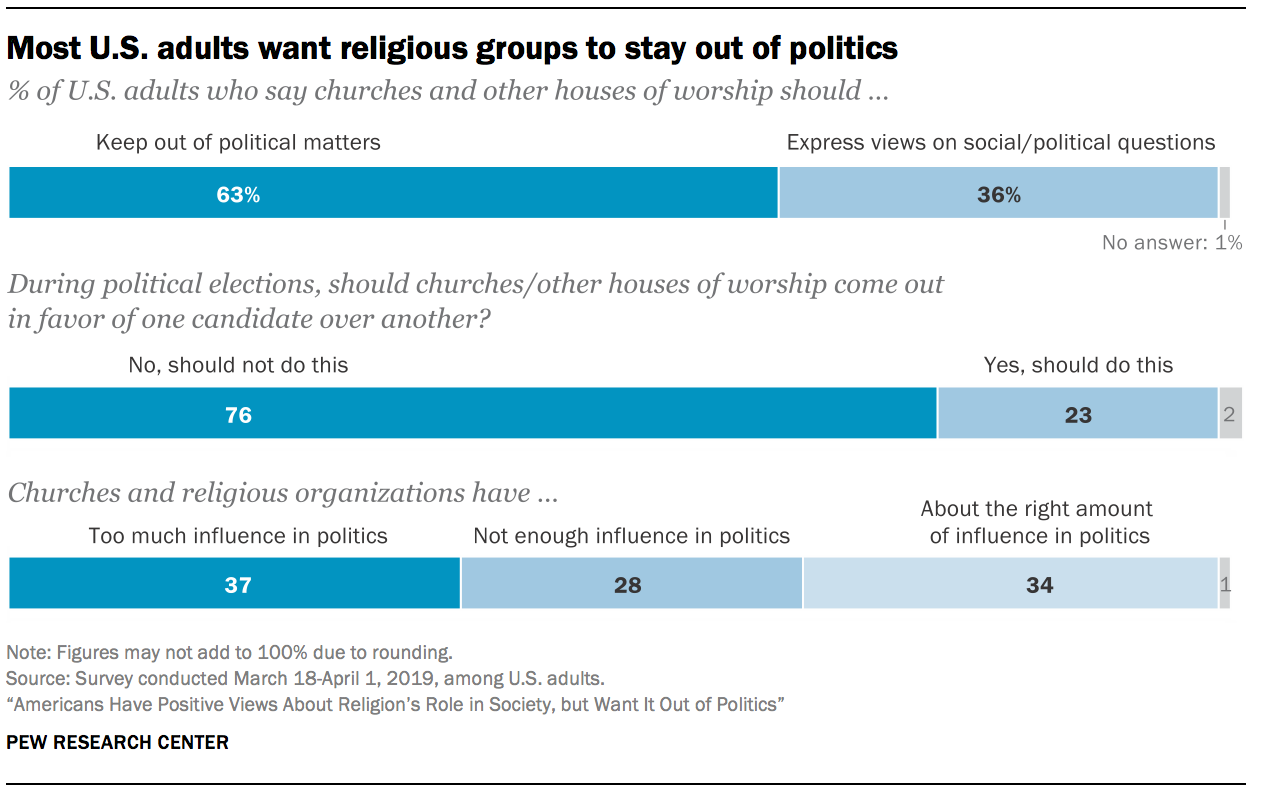

At the same time, U.S. adults are resoundingly clear in their belief that religious institutions should stay out of politics. Nearly two-thirds of Americans in the new survey say churches and other houses of worship should keep out of political matters, while 36% say they should express their views on day-to-day social and political questions. And three-quarters of the public expresses the view that churches should not come out in favor of one candidate over another during elections, in contrast with efforts by President Trump to roll back existing legal limits on houses of worship endorsing candidates. 1

In addition, Americans are more likely to say that churches and other houses of worship currently have too much influence in politics (37%) rather than too little (28%), while the remaining one-third (34%) say religious groups’ current level of influence on politics is about right.

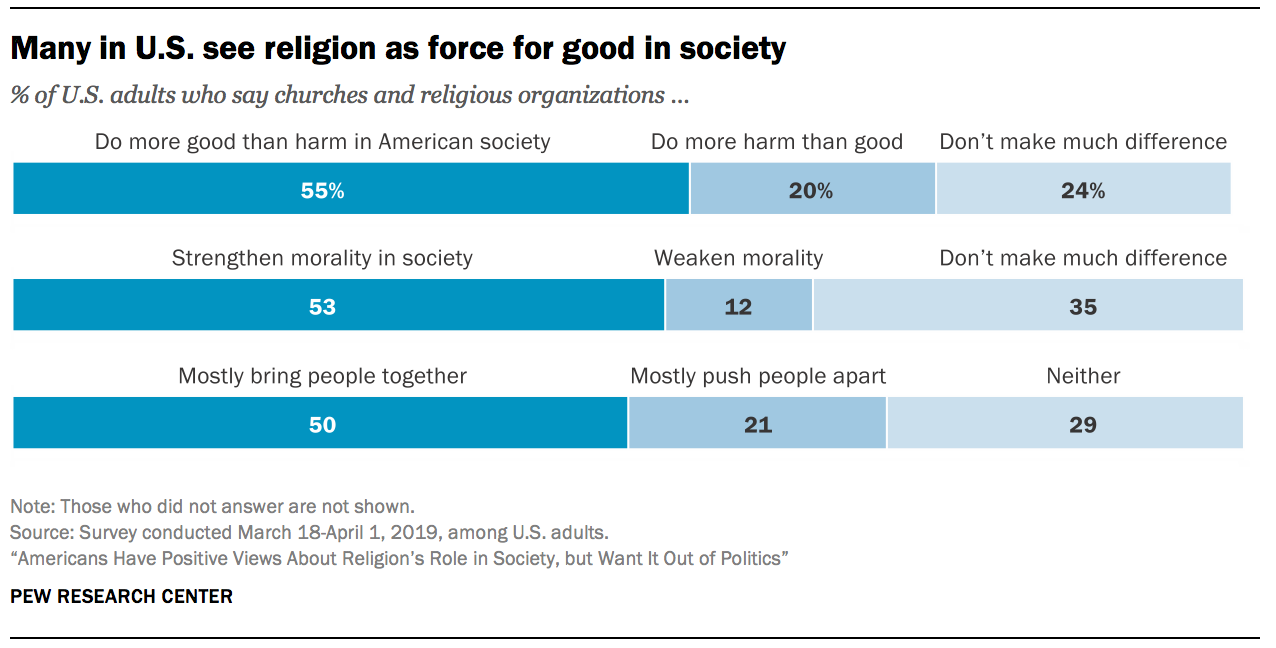

On balance, U.S. adults have a favorable view about the role religious institutions play in American life more broadly – beyond politics. More than half of the public believes that churches and religious organizations do more good than harm in American society, while just one-in-five Americans say religious organizations do more harm than good. Likewise, there are far more U.S. adults who say that religious organizations strengthen morality in society and mostly bring people together than there are who say that religious organizations weaken morality and mostly push people apart. On all three of these questions, views have held steady since 2017 , the last time the Center measured opinions on these issues.

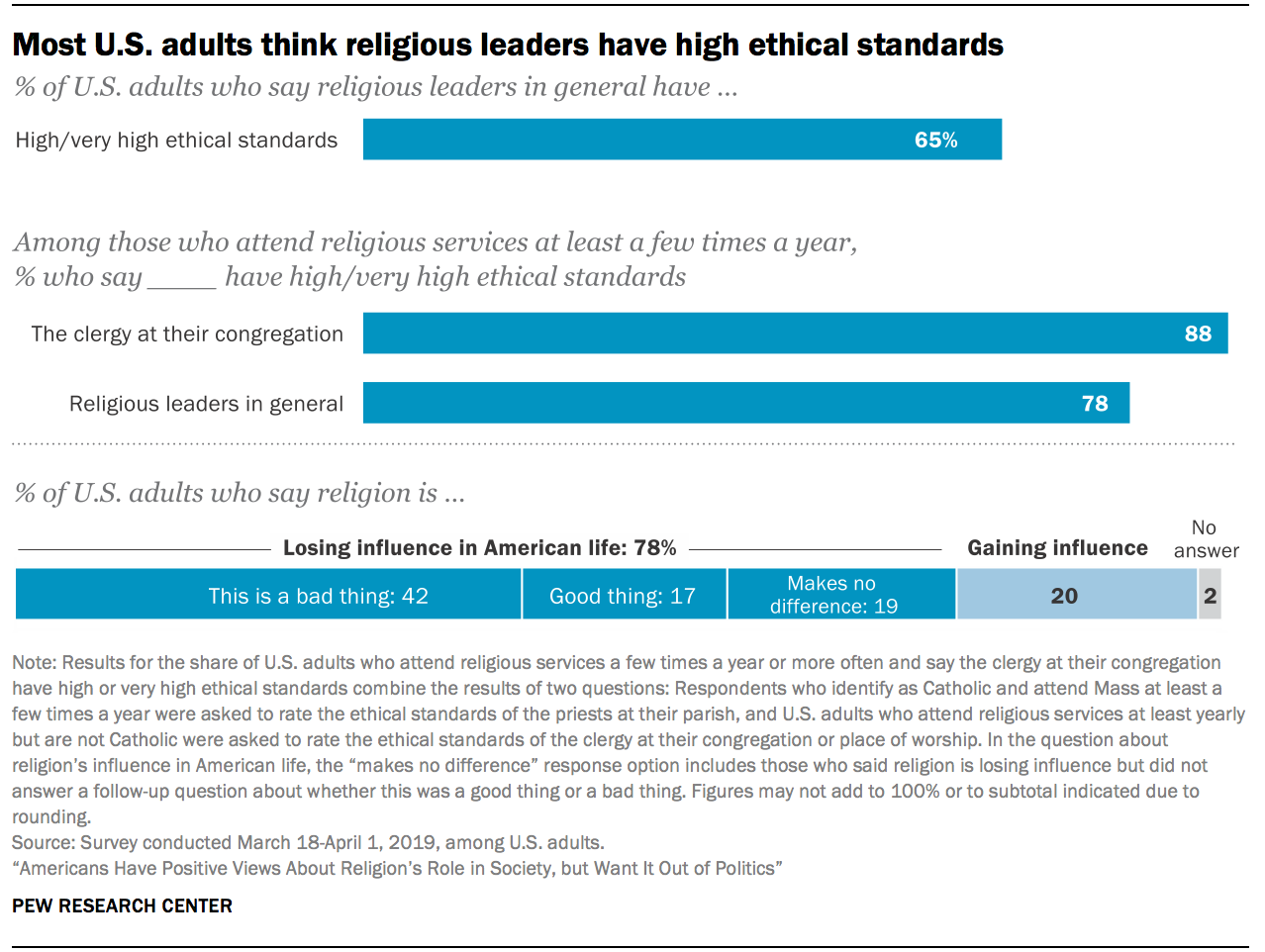

The survey also shows that roughly four-in-ten U.S. adults – including a majority of Christians – lament what they perceive as religion’s declining influence on American society, while fewer than two-in-ten say they think religion is losing influence in American life and that this is a good thing. In addition, roughly two-thirds of the public believes that religious leaders in general have high or very high ethical standards, and a larger share of Americans who attend religious services at least a few times a year say this about the clergy in their own congregations. Among these U.S. adults who attend religious services, majorities express at least “some” confidence in their clergy to provide useful guidance not only on clearly religious topics (such as how to interpret scripture) but also on other matters, such as parenting and personal finance (see Chapter 2 ).

These are among the key findings from a nationally representative survey of 6,364 U.S. adults conducted online from March 18 to April 1, 2019, using Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel. The margin of sampling error for the full sample is plus or minus 1.7 percentage points. Many of the questions in the survey were asked only of U.S. adults who attend religious services a few times a year or more often; results for that group have a margin of error of plus or minus 2.4 percentage points.

The survey, part of an ongoing effort by the Center to explore the role of trust, facts and democracy in American society, was designed to gauge the public’s views about many aspects of religion’s role in public life, as well as asking how much U.S. adults trust clergy to provide various kinds of guidance, what messages Americans receive from their clergy about other religious groups, how satisfied they are with the sermons they hear, how close they feel to their religious leaders, and whether they know – and share – the political views of the clergy in their houses of worship.

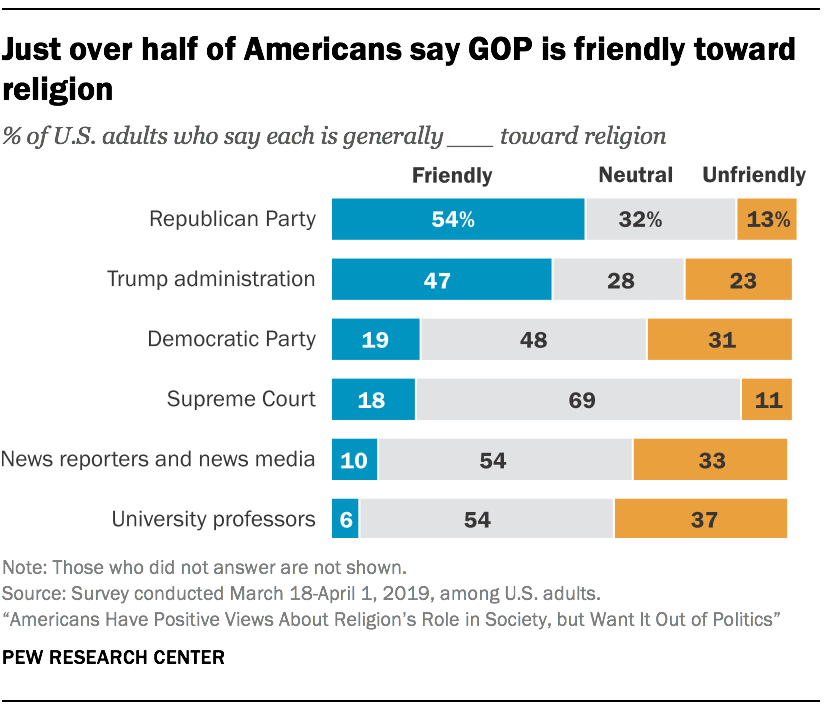

The survey shows that slightly more than half of U.S. adults say that the Republican Party is friendly toward religion (54%), while just under half say the same about the Trump administration (47%). Far fewer say these two groups are unfriendly toward religion. Other major societal institutions are viewed by majorities or pluralities of the public as neutral toward religion; for instance, roughly seven-in-ten U.S. adults say the Supreme Court is neutral toward religion.

Equal shares say that reporters and the news media (54%) and university professors (54%) are neutral toward religion, and 48% say this about the Democratic Party. In each of these cases, however, Americans are considerably more likely to say these groups are unfriendly toward religion than to say they are friendly. For instance, more than one-third of the public (37%) says university professors are unfriendly to religion, while just 6% say professors are friendly to religion.

On balance, Republicans and Democrats mostly agree with each other that the GOP is friendly toward religion. They disagree, however, in their views about the Democratic Party; most Republicans and those who lean toward the Republican Party say the Democratic Party is unfriendly toward religion, while most Democrats and those who lean to the Democratic Party view their own party as neutral toward religion.

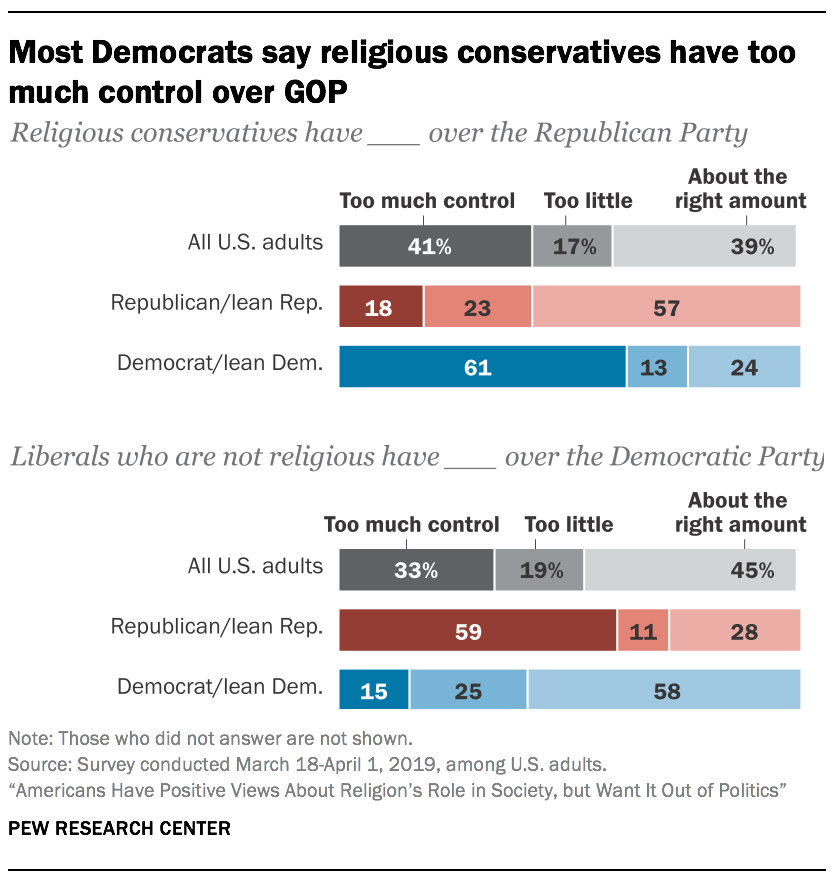

Partisan differences in views toward religion in public life

The survey also finds that four-in-ten U.S. adults (including six-in-ten among those who identify with or lean toward the Democratic Party) think religious conservatives have too much control over the Republican Party. At the same time, one-third of Americans (including six-in-ten among those who identify with or lean toward the GOP) say liberals who are not religious have too much control over the Democratic Party.

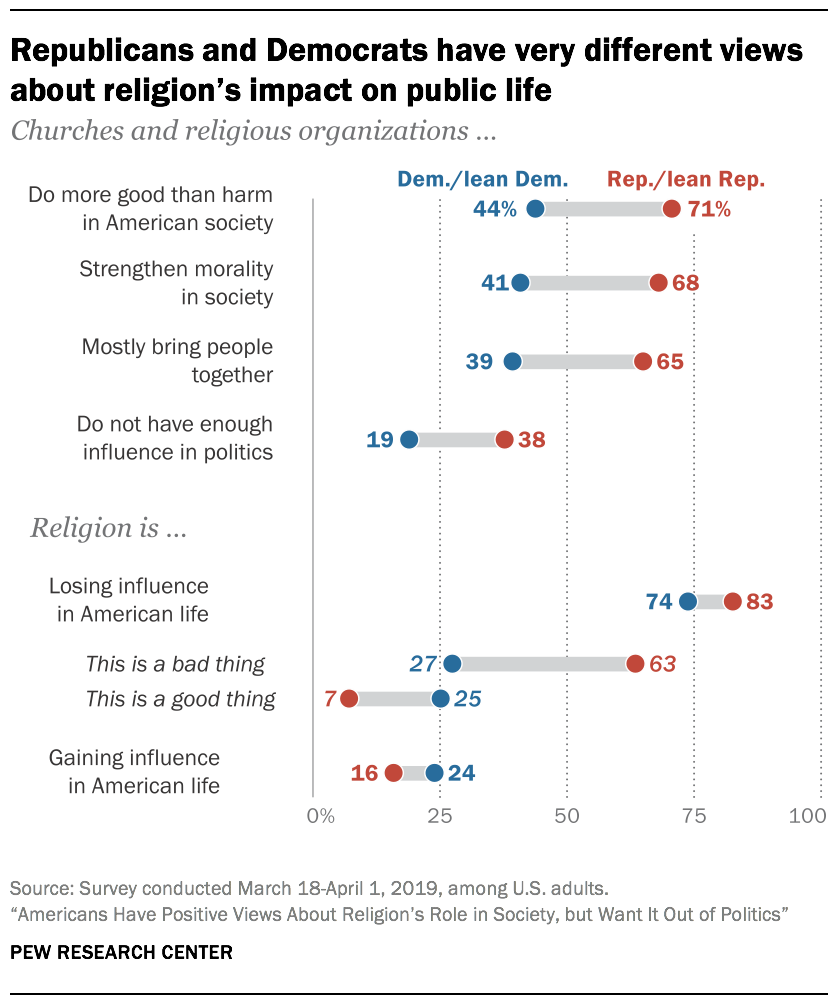

More broadly, Republicans and Democrats express very different opinions about religion’s impact on American public life. Seven-in-ten Republicans say churches and religious organizations do more good than harm in the U.S., and two-thirds say these institutions strengthen morality in American society and mostly bring people together (rather than push them apart). On all three of these measures, Democrats are less likely to share these positive views of religious organizations. 2

Furthermore, most Republicans say religion either has about the right amount of influence (44%) or not enough influence (38%) in the political sphere, while a slim majority of Democrats say that religion has too much influence in politics (54%). And although most Republicans and Democrats (including those who lean toward each party) agree that religion is losing influence in American life, Republicans are far more likely than Democrats to view this as a regrettable development (63% vs. 27%). There are about as many Democrats who say religion’s decline is a good thing (25%) as there are who say it is a bad thing (27%), with 22% of Democrats saying religion’s declining influence doesn’t make much difference either way.

Feelings about religion vary among Democrats based on race and ethnicity

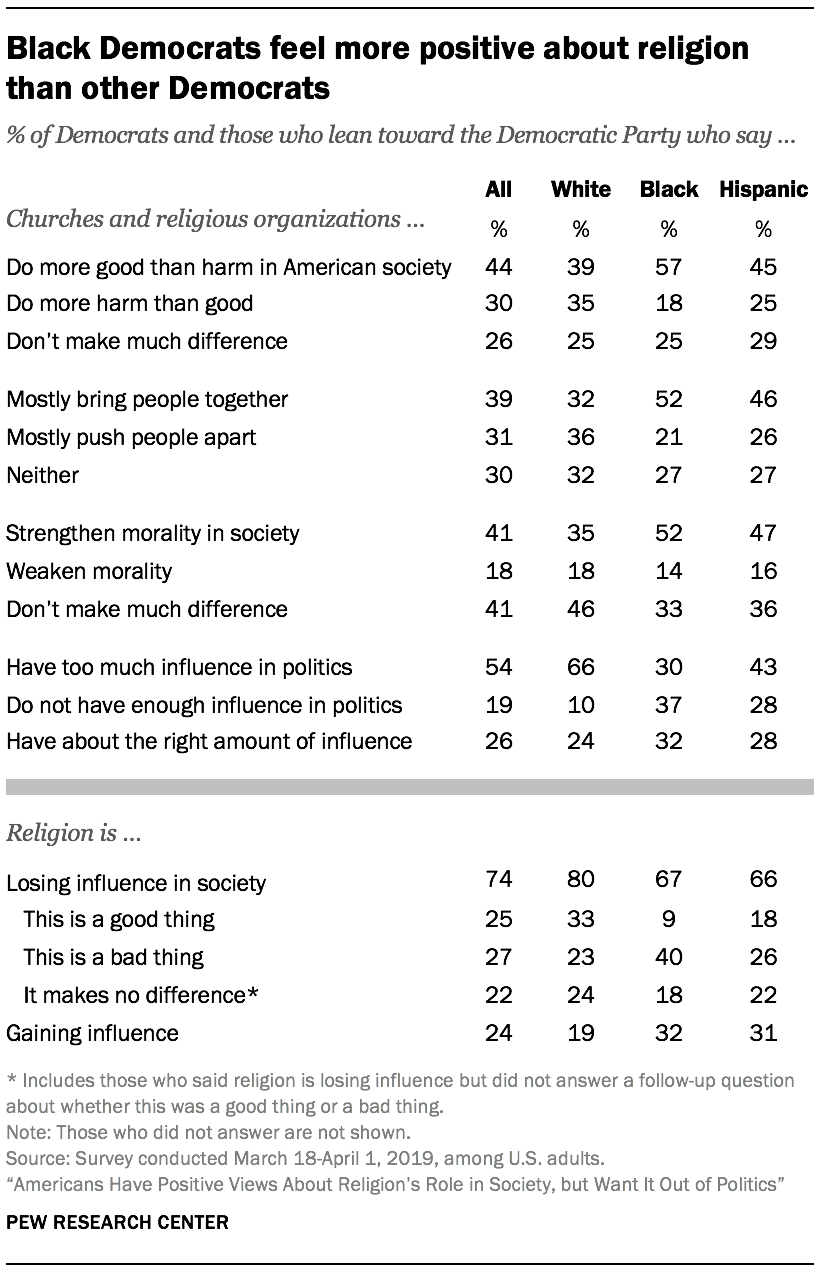

There are stark racial differences among Democrats and those who lean toward the Democratic Party in views on religion’s role in society: Black Democrats consistently express more positive views of religious institutions than do white Democrats. For example, half or more of black Democrats say churches and religious organizations do more good than harm in American society, mostly bring people together (rather than push them apart), and strengthen morality in society. White Democrats are substantially less inclined than black Democrats to hold these views.

In addition, two-thirds of white Democrats say churches have too much political power, compared with only three-in-ten black Democrats and four-in-ten Hispanic Democrats who say this. In fact, black Democrats are just as likely as white Republicans to say churches do not have enough influence in politics (37% each). 3 And while one-third of white Democrats (33%) say that religion is losing influence in society more broadly and that this is a good thing, far fewer black (9%) and Hispanic (18%) Democrats agree.

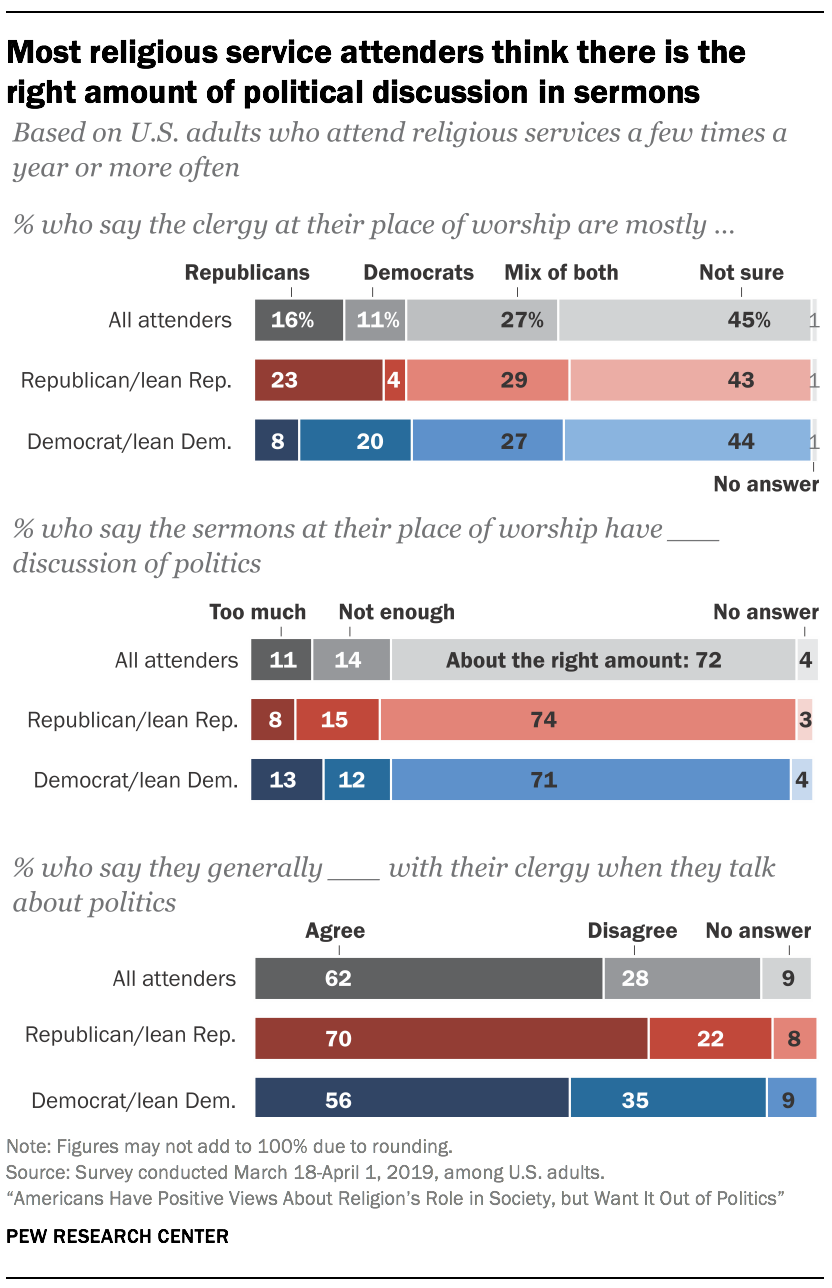

Americans who attend religious services largely satisfied with political talk by clergy

The survey also sought to gauge people’s perceptions about the politics of their clergy, finding that relatively few Americans say their clergy are united on one side of the partisan divide. In fact, many Americans who attend religious services at least a few times a year say they are unsure of the party affiliation of the clergy at their place of worship (45%), while about one-in-four say their clergy are a mix of both Republicans and Democrats (27%). 4 When those who attend religious services think they know their leaders’ party affiliation, slightly more say their clergy are mostly Republicans (16%) than say they are mostly Democrats (11%).

Among partisans, few say their clergy are mostly members of the opposite party. For example, among those who attend religious services at least a few times a year and identify with or lean toward the Republican Party, just 4% say their clergy are mostly Democrats, while 23% say they are Republicans. Similarly, among Democrats and Democratic leaners, 8% say their clergy are Republicans, while 20% say their clergy are Democrats. Among both groups, most say they are unsure of the political leanings of their clergy, or say that there is a mix of both Republicans and Democrats in the religious leadership of their congregation.

Most attenders – including majorities in both parties – are satisfied with the amount of political discussion they’re hearing in sermons. About seven-in-ten say the sermons at their place of worship have about the right amount of political discussion, while 14% say there is not enough political talk and 11% say there is too much political talk in the sermons they hear.

Furthermore, congregants tend to agree with their clergy when politics is discussed: Overall, about six-in-ten say they generally agree with their clergy about politics (62%), although Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say this (70% vs. 56%).

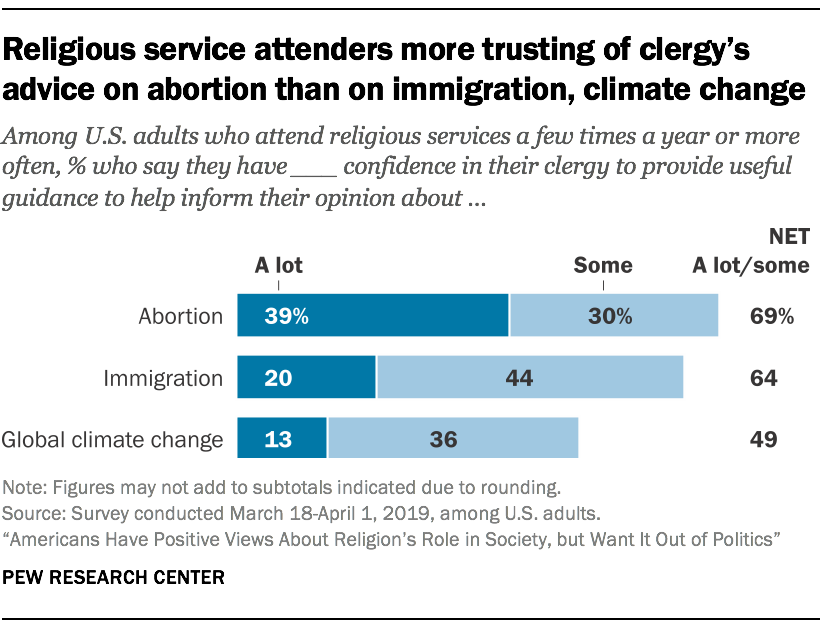

The survey asked those who attend religious services at least a few times a year the extent to which religious leaders help inform their opinion about three social and political issues: abortion, immigration and global climate change. Four-in-ten religious service attenders have a lot of confidence in their clergy to provide useful guidance to inform their opinion on abortion. Smaller shares have a lot of trust in their clergy’s guidance about immigration (20%) or global climate change (13%).

Republican attenders are much more likely than Democrats who go to religious services to say they have a lot of confidence in their clergy to provide guidance about abortion (53% vs. 25%). Catholics are consistently less likely than Protestants – particularly evangelical Protestants – to say they trust their clergy on all three issues. On abortion, for example, 34% of Catholics say they have a lot of trust in their clergy to provide guidance that helps form their opinion, compared with 46% of Protestants overall and 57% of evangelical Protestants who say this. Mainline Protestants (33%) and members of the historically black Protestant tradition (32%) look similar to Catholics on this question.

Other key findings from the survey include:

- Americans who attend religious services with any regularity express “a lot” of trust in the clergy or other religious leaders at their place of worship to provide advice about religious questions, such as growing closer to God or how to interpret scripture. They are more skeptical about advice from their religious leaders on other common life milestones and issues, such as marriage and relationships, parenting, mental health problems, and personal finances, although most express at least “some” confidence in their clergy to weigh in on these topics. And in general, Catholics are less likely than Protestants to say they trust their clergy to provide advice on these issues. (For more, see here .)

- Most adults who attend religious services a few times a year or more describe themselves as having at least a “somewhat close” relationship with the clergy at their place of worship, although respondents are much more likely to say they have a “somewhat close” relationship with their clergy (50%) than a “very close” one (19%). About three-in-ten say they are not close with the clergy at their congregation (29%). Just 8% of Catholics say they are very close with their clergy, a much lower share than in any other major U.S. Christian group analyzed. (For more, see here .)

- Many U.S. adults hear messages about religious groups other than their own from their clergy or other religious leaders. About four-in-ten religious service attenders have heard their clergy speak out about atheists (43%), while slightly fewer have heard clergy speak out about Catholics or Jews (37% each). About one-third of attenders say they’ve heard their clergy mention evangelical Christians (33%) or Muslims (31%). In terms of the types of messages congregants are hearing from their clergy, the messages about atheists tend to be more negative than positive, while the sentiments toward Jews are mostly positive. 5 (For more, see here .)

- When searching for information about their religion’s teachings, religiously affiliated adults say scripture is the most trusted source. Six-in-ten U.S. adults who identify with a religious group say they have “a lot” of confidence in the information they’d find in scripture, and an additional three-in-ten say they have “some” confidence in this source. Four-in-ten would have a lot of confidence in the clergy at their congregation to give information about religious teachings. Fewer place a high level of trust in family, professors of religion, friends, religious leaders with a large national or international following, or information found online. (For more, see here .)

- Most Americans (66%) say religious and nonreligious people generally are equally trustworthy, while fewer think religious people are more trustworthy than nonreligious people (21%) or that nonreligious people are the more trustworthy ones (12%). Majorities across religious groups say religious and nonreligious people are equally trustworthy, but evangelical Protestants are more likely than others to say religious people are especially trustworthy, and self-described atheists are particularly likely to put more trust in nonreligious people. (For more, see here .)

- When U.S. adults find themselves in an argument about religion, most say they approach the conversation in a nonconfrontational manner. About six-in-ten say that when someone disagrees with them about religion, they try to understand the other person’s point of view and agree to disagree. One-third say they simply avoid discussing religion when a disagreement arises, and only 4% say they try to change the other person’s mind. (For more, see here .)

The remainder of this report examines the public’s views about religion in public life and religious leaders in further detail, including differences in opinions across religious groups. Chapter 1 looks at Americans’ views about religion in public life. Chapter 2 explores levels of confidence in clergy (and other clergy-related opinions) held by Americans who attend religious services at least a few times a year. And Chapter 3 looks at religion’s role in some of Americans’ interpersonal relationships, including levels of trust in religious and nonreligious people.

- This is not the first time Pew Research Center has asked these questions of the U.S. public. However, previous surveys were conducted over the phone by a live interviewer, and are not directly comparable to the new survey, which respondents self-administered online as part of the Center’s American Trends Panel . ↩

- Another question asked on a different 2019 Pew Research Center survey – conducted by telephone – found that Republicans and those who lean toward the Republican Party also are much more likely than Democrats and their leaners to say churches and other religious organizations are having a positive effect on the way things are going in the country (68% vs. 38%). The overall share of Americans who say churches are having a positive impact has declined in recent years, according to telephone surveys. ↩

- Researchers were not able to separately compare the views of black and Hispanic Republicans due to limited sample size. Previous Pew Research Center telephone surveys have found that majorities of black and Hispanic adults identify with or lean toward the Democratic Party while minorities in these groups identify as Republicans or lean toward the GOP. ↩

- Many places of worship have multiple clergy, while others have just one. The question was asked this way so that it would apply to respondents regardless of how many clergy work at their place of worship. ↩

- Results are based only on respondents who are not a member of the group in question. For example, results about Catholics do not include the views of Catholics themselves. See topline for filtering and question wording. ↩

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Religion & Government

- Religion & Politics

- Trust in Government

- Trust, Facts & Democracy

Korean Americans are much more likely than people in South Korea to be Christian

Many around the globe say it’s important their leader stands up for people’s religious beliefs, the religious composition of the world’s migrants, religious composition of the world’s migrants, 1990-2020, where is the most religious place in the world, most popular, report materials.

- American Trends Panel Wave 46

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

student opinion

What Role Does Religion Play in Your Life?

Did you attend religious services or observe religious traditions as a child? How has religion shaped who you are today?

By Nicole Daniels and Michael Gonchar

When you were younger, did you attend religious services or participate in religious observations with your family? Did you belong to any kind of religious community? What about now, as a teenager?

Has religion played an important role in your life? If so, in what ways?

In her recent Opinion essay, “ I Followed the Lives of 3,290 Teenagers. This Is What I Learned About Religion and Education ,” Ilana M. Horwitz discusses the effects of a religious upbringing on academic success:

American men are dropping out of college in alarming numbers. A slew of articles over the past year depict a generation of men who feel lost , detached and lacking in male role models . This sense of despair is especially acute among working-class men, fewer than one in five of whom completes college. Yet one group is defying the odds: boys from working-class families who grow up religious. As a sociologist of education and religion, I followed the lives of 3,290 teenagers from 2003 to 2012 using survey and interview data from the National Study of Youth and Religion , and then linking those data to the National Student Clearinghouse in 2016. I studied the relationship between teenagers’ religious upbringing and its influence on their education: their school grades, which colleges they attend and how much higher education they complete. My research focused on Christian denominations because they are the most prevalent in the United States. I found that what religion offers teenagers varies by social class. Those raised by professional-class parents, for example, do not experience much in the way of an educational advantage from being religious. In some ways, religion even constrains teenagers’ educational opportunities (especially girls’) by shaping their academic ambitions after graduation; they are less likely to consider a selective college as they prioritize life goals such as parenthood, altruism and service to God rather than a prestigious career. However, teenage boys from working-class families, regardless of race, who were regularly involved in their church and strongly believed in God were twice as likely to earn bachelor’s degrees as moderately religious or nonreligious boys. Religious boys are not any smarter , so why are they doing better in school? The answer lies in how religious belief and religious involvement can buffer working-class Americans — males in particular — from despair.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Where does Confucianism come from?

- How did Confucianism spread?

- What are the basic teachings of Daoism?

- Who were the great teachers of Daoism?

- How does Daoism differ from Confucianism?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- The Guardian - Religion: why faith is becoming more and more popular

- Verywell Mind - What is Religion?

- World History Encyclopedia - Religion in the Ancient World

- Live Science - The Origins of Religion: How Supernatural Beliefs Evolved

- Learn Religions - What's the Difference Between Religion and Spirituality?

- Social Sciences LibreTexts - Religion

- McClintock and Strong Biblical Cyclopedia - Religion

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - The Concept of Religion

- Pressbooks - Perspectives: An Open Introduction to Cultural Anthropology, 2nd Edition - Religion

- religion - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- religion - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

religion , human beings’ relation to that which they regard as holy, sacred, absolute, spiritual, divine, or worthy of especial reverence. It is also commonly regarded as consisting of the way people deal with ultimate concerns about their lives and their fate after death . In many traditions, this relation and these concerns are expressed in terms of one’s relationship with or attitude toward gods or spirits; in more humanistic or naturalistic forms of religion, they are expressed in terms of one’s relationship with or attitudes toward the broader human community or the natural world. In many religions, texts are deemed to have scriptural status, and people are esteemed to be invested with spiritual or moral authority. Believers and worshippers participate in and are often enjoined to perform devotional or contemplative practices such as prayer , meditation , or particular rituals . Worship , moral conduct, right belief , and participation in religious institutions are among the constituent elements of the religious life.