- Federico Fellini Films Analysis Words: 1939

- Issues in the Film Industry Words: 2226

- Dunkirk: Analysis of Film by Nolan Words: 675

- The American Gangster Film Analysis Words: 1117

- Predicting the Future of Film Narrative Words: 2840

- “Psycho” Film by Alfred Hitchcock Words: 1688

- Films and Their Role in Society Words: 2414

- The Autumn Sonata Film by Ingmar Bergman Words: 1240

- Ideology in “The Matrix” Film Words: 1089

- Film Terms, Aesthetic and Cultural Analysis Words: 2768

- Horror Films: Articles Analysis and Comparison Words: 1950

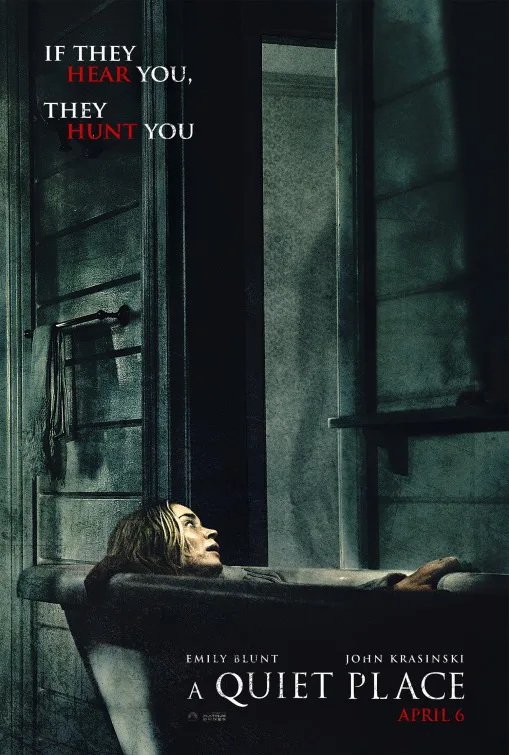

“A Quiet Place”: Film Analysis

A Quiet Place is a 2018 horror and mystery thriller directed by John Krasinski. The plot revolves around a family—wife Evelyn (Emily Blunt), husband Lee (John Krasinski), and their children Regan (Millicent Simmonds), Marcus (Noah Jupe), and Beau (Cade Woodward)—who struggle to survive in a post-apocalyptic world dominated by blind aliens with hypersensitive hearing. The film heavily relies on sound effects and narrative structure to convey its central motif, a dreadful life in which silence is a means of survival.

The film A Quiet Place tells a story of a world where predatory monsters have annihilated the Earth and made anything that makes a sound their prey. The plot focuses on the life of a family that seemed to have survived for more than a year by communicating in American Sign Language. The couple struggles with more than just survival after the tragic death of their youngest son. What is more, Emily Blunt’s character is pregnant, so she has to manage to stay silent during labor and muffle the cries of a newborn baby. The characters have to adapt and find a way to combat the mysterious, dangerous creatures—without making a single sound.

Auditory impressions are pivotal to the story’s presentation in a world where noises are virtually fatal. The director heavily relies on the use of sounds to convey the immediate surroundings of the characters. By providing the viewer with what the characters hear, Krasinski creates a deeper connection between the plot and the audience. He includes a wide range of sounds, as loud as a roaring stream or as minute as a crackling fire, to fully immerse the viewer into the atmosphere of the dystopic world ( A Quiet Place 34:49-36:00). Moreover, the occasional contrast between the degree of loudness of the sounds adds to the tension essential to the film.

For instance, the soft sound of rolling dice is suddenly interrupted by the sharp noise of a shattering lantern ( A Quiet Place 19:00-19:30). The film’s atmosphere benefits from adding a variety of ubiquitous sounds as it enables the complete immersion of the audience in the world filled with aliens.

The effect mentioned above is supported by a more conventional usage of sound in cinema, namely short musical compositions. Rather than conveying what the characters hear, short pieces of music are used to establish the characters’ inner state. For example, as the father and son prepare to go foraging, the director inserts a mellow instrumental composition to develop a sense of serenity ( A Quiet Place 30:00-32:30). In contrast, the viewer hears an increasingly unsettling melody, which helps understand that the characters become uneasy and filled with dread as they realize that the aliens are approaching ( A Quiet Place 46:05-47:50). The usage of music in the film is appropriate and contributes to the general perception of the events.

The sounds—and often the absence of any—are intertwined with the narrative structure. A technique frequently used in the film is contrasting silent scenes with loud episodes. For example, the encounter with another survivor in the woods, ending in a piercing scream and an attack from the alien, is followed by a seemingly peaceful scene in the nursery ( A Quiet Place 42:35-45:00). Although the events’ respective sites were not in geographical proximity to each other, the contrast still keeps the viewer engaged and uncertain of what comes next. Moreover, such an approach conveys the pace at which a situation can escalate in this post-apocalyptic world—essentially, at the speed of sound.

It is also worth noting that Krasinski has created an individual narrative for each character. Most notably, he juxtaposes the deaf daughter Reagan’s perception of the world to that of her family by removing sound from her perspective ( A Quiet Place 3:40-4:30). This approach adds another facet to Reagan’s story, mainly to emphasize her guilt over her brother’s death because he could not hear his mistake. Moreover, the character’s journey is also central to the movie as she ultimately becomes the solution and the weapon to distress the creatures.

A Quiet Place proves to be a worthwhile watch for several reasons. First, although the film shows a quintessential horror film scenario—a group of survivors trying to outsmart a vicious unknown creature— the presentation of the narrative, particularly reliance on auditory techniques, makes it a singular cinematographic piece. Second, the plot touches upon classic problems, such as parents’ unconditional love and willingness to sacrifice themselves for the sake of their offspring. Finally, conveying the general ideas of the film in the virtual absence of dialogue makes the piece even more exhilarating. If one is looking for an engaging and nerve-racking visual and auditory piece, the masterful combination of various film forms in A Quiet Place makes it the perfect recommendation.

A Quiet Place . Directed by John Krasinski, performances by Emily Blunt and John Krasinski, Paramount Pictures, 2018.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2022, October 4). “A Quiet Place”: Film Analysis. https://studycorgi.com/a-quiet-place-film-analysis/

"“A Quiet Place”: Film Analysis." StudyCorgi , 4 Oct. 2022, studycorgi.com/a-quiet-place-film-analysis/.

StudyCorgi . (2022) '“A Quiet Place”: Film Analysis'. 4 October.

1. StudyCorgi . "“A Quiet Place”: Film Analysis." October 4, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/a-quiet-place-film-analysis/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "“A Quiet Place”: Film Analysis." October 4, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/a-quiet-place-film-analysis/.

StudyCorgi . 2022. "“A Quiet Place”: Film Analysis." October 4, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/a-quiet-place-film-analysis/.

This paper, ““A Quiet Place”: Film Analysis”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: October 4, 2022 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

A Quiet Place

John Krasinski ’s “A Quiet Place” is a nerve-shredder. It’s a movie designed to make you an active participant in a game of tension, not just a passive observer in an unfolding horror. Most of the great horror movies are so because we become actively invested in the fate of the characters and involved in the cinematic exercise playing out before us. It is a tight thrill ride—the kind of movie that quickens the heart rate and plays with the expectations of the audience, while never treating them like idiots. In other words, it’s a really good horror movie.

With his script, co-written by Bryan Woods and Scott Beck , Krasinski wastes no time. We see a family—Krasinski plays the unnamed father, his real-life wife Emily Blunt plays the mother, and Noah Jupe (“ Suburbicon ”), Millicent Simmonds (“ Wonderstruck ”), and Cade Woodward play their three children. The eldest, the girl, is deaf (as is the remarkable young actress who plays her). A title card says it’s “Day 89,” and we can tell we’re in a recently-post-apocalyptic world. The family very slowly—on tiptoes—moves around a small-town store, taking some of the few remaining supplies and some prescription drugs for the older boy, who looks like he has the flu. They communicate in sign language and are incredibly careful not to make a sound, but the youngest boy draws a picture of a rocket on the floor—the thing that he signs will take them all away.

We quickly discern that sound in this world is dangerous. And the danger is intensified in the following sequence as the youngest child finds a toy that makes noise and … things don’t end well. The bulk of “A Quiet Place” takes place over a year later, as the family continues to grieve and the mother is about 38 weeks pregnant. Preparing for the arrival of a newborn baby in a world without noise is difficult, and the father continues to pore over newspaper articles and research, looking for a way to stop the creatures that kill at the slightest sound.

Larger-than-life enemies that can detect their prey aurally have been a part of great cinema for years, from the xenomorph hunting the crew of the Nostromo in “ Alien ” to the dinosaurs of “ Jurassic Park ,” and Krasinski knows that lineage. He’s incredibly smart about the way he brings the viewer into this auditory game. He’s regularly—but not too regularly—setting up what could be called ‘auditory expectations.’ He’ll show us a shotgun or an exposed nail in the floor or a timer in silence—and we know full well what sounds those are likely to produce. Don’t worry—Krasinski doesn’t overplay it at all. There aren’t rooms of wind chimes or broken glass. It’s a very subtle, clever storytelling tool to build tension when a director and his co-screenwriters aren’t allowed to use dialogue to do so, and it pulls us into this world in a way that’s unexpected and incredibly enjoyable.

It also helps that Krasinski displays a sense of composition and economic storytelling that he hasn’t really before in other films. “A Quiet Place” is a no-nonsense, lean movie—the best kind when it comes to thrillers. It feels like every shot has been considered incredibly carefully as the film ticks like a clock on a bomb, perfectly balancing scares with scenes that set up the emotional stakes and the world of these characters. The film has a beautiful sense of geography, almost all of it taking place on a farm that Krasinski and his technical team lay out in a way that allows us to feel like we know it. This is not one of those films that mistakes shaky camerawork for horror storytelling. It’s got a refined visual language that plays beautifully with perspective and the terrifying nature of a world in which we can’t yell to warn/find people or, in the case of the deaf daughter, hear what’s coming.

On that note, there’s also—without spoiling anything—a strong, enabling message at the core of “A Quiet Place.” It’s a film that’s about empowerment more than sheltering, and it’s that emotional hook that really elevates the final act. It helps a great deal that Krasinski completely sticks the landing. It has one of the best final shots in horror in years—and, of course, it comes with a familiar auditory cue that had the audience here at SXSW cheering.

With almost no dialogue, “A Quiet Place” relies a great deal on visual storytelling, but I’ll admit that it also uses the crutches of composer Marco Beltrami’s strings for jump scares a bit too much. It’s total conjecture, but one can almost sense Platinum Dunes head Michael Bay insisting on those devices, and I’d love to see a version of “A Quiet Place” that’s even sparser in terms of on-the-nose choices like sound-scares and an overheated score.

We live in a such a noisy world that it’s hard to imagine that constant sound being taken away. We use noise to express ourselves—it’s a part of who we are as people. And “A Quiet Place” weaponizes that part of the human condition in a way that owes a debt to films like “Alien” but also charts its own new ground. So many great horror films are about people who have to adapt to survive—they have to challenge their own insecurities or preconceptions to make it through the night. In that sense, great horror films are often about empowerment, taking away that which some might perceive as weak. “A Quiet Place” shreds the nerves, but it does so in a way that feels rewarding. You don’t just walk out having experienced a thrill ride, you walk out on a high, the kind of high that only comes from the best horror movies.

This review was filed from the World Premiere at the SXSW Film Festival in Austin on March 10, 2018.

Brian Tallerico

Brian Tallerico is the Managing Editor of RogerEbert.com, and also covers television, film, Blu-ray, and video games. He is also a writer for Vulture, The Playlist, The New York Times, and GQ, and the President of the Chicago Film Critics Association.

- Millicent Simmonds as

- Noah Jupe as Marcus

- John Krasinski as

- Emily Blunt as

- Cade Woodward as Beau

Writer (story by)

- Bryan Woods

- John Krasinski

Cinematographer

- Charlotte Bruus Christensen

- Christopher Tellefsen

- Marco Beltrami

Leave a comment

Now playing.

Speak No Evil (2024)

Saturday Night

The Killer’s Game

Girls Will Be Girls

The 4:30 Movie

Sweetheart Deal

¡Casa Bonita Mi Amor!

Latest articles

TIFF 2024: Table of Contents

TIFF 2024: Village Keeper, 40 Acres, Flow

TIFF 2024: The Shadow Strays, Friendship, The Shrouds

TIFF 2024: Babygirl, All We Imagine as Light, Queer

The best movie reviews, in your inbox.

24/7 writing help on your phone

To install StudyMoose App tap and then “Add to Home Screen”

A Quiet Place by John Krasinski: Film Analysis

Save to my list

Remove from my list

Works cited

- Krasinski, J. (Director & Actor). (2018). A Quiet Place [Film]. Paramount Pictures.

- Miska, B. (2018, April 3). ‘A Quiet Place’ is a Perfectly Constructed, Beautifully Acted Horror Masterpiece [Review]. Bloody Disgusting. https://bloody-disgusting.com/reviews/3480347/quiet-place-perfectly-constructed-beautifully-acted-horror-masterpiece-review/

- Peters, M. (2018, April 5). A Quiet Place: A horror movie for people who don’t like horror movies [Review]. The Arizona Republic. https://www.azcentral.com/story/entertainment/movies/2018/04/05/a-quiet-place-horror-movie-people-who-dont-like-horror-movies/485573002/

- Pulver, A. (2018, April 5). A Quiet Place review – a nerve-shredding, if flawed, horror original [Review]. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2018/apr/05/a-quiet-place-review-john-krasinski-emily-blunt-monster-movie

- Schager, N. (2018, April 6). Film Review: ‘A Quiet Place’. Variety. https://variety.com/2018/film/reviews/a-quiet-place-review-john-krasinski-emily-blunt-1202743209/

- Seitz, M. Z. (2018, April 5). A Quiet Place Is an Apocalyptic Horror Film That Will Give You Platinum-Grade Anxiety [Review]. Vulture. https://www.vulture.com/2018/04/movie-review-a-quiet-place-is-a-terrific-horror-film.html

- Tambay Obenson, T. (2018, April 8). ‘A Quiet Place’: John Krasinski Explains Why He Cast Millicent Simmonds and Emily Blunt [Interview]. IndieWire. https://www.indiewire.com/2018/04/a-quiet-place-john-krasinski-emily-blunt-millicent-simmonds-1201944473/

- Travers, P. (2018, April 5). ‘A Quiet Place’ Review: Silence Has Never Been Scarier in New Horror Classic [Review]. Rolling Stone. https://www.rollingstone.com/movies/movie-reviews/a-quiet-place-review-silence-has-never-been-scarier-in-new-horror-classic-629348/

- Weaver, C. (2018, April 4). ‘A Quiet Place’ is a riveting horror film that will keep you on the edge of your seat [Review]. Chicago Tribune. https://www.chicagotribune.com/entertainment/movies/sc-mov-quiet-place-rev-0403-story.html

- White, A. (2018, April 4). A Quiet Place review: John Krasinski’s monster movie makes a deafening statement [Review]. The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/reviews/a-quiet-place-review-john-krasinski-emily-blunt-monster-movie-alien-horror-a8291271.html

A Quiet Place by John Krasinski: Film Analysis. (2024, Feb 12). Retrieved from https://studymoose.com/a-quiet-place-by-john-krasinski-film-analysis-essay

"A Quiet Place by John Krasinski: Film Analysis." StudyMoose , 12 Feb 2024, https://studymoose.com/a-quiet-place-by-john-krasinski-film-analysis-essay

StudyMoose. (2024). A Quiet Place by John Krasinski: Film Analysis . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/a-quiet-place-by-john-krasinski-film-analysis-essay [Accessed: 17 Sep. 2024]

"A Quiet Place by John Krasinski: Film Analysis." StudyMoose, Feb 12, 2024. Accessed September 17, 2024. https://studymoose.com/a-quiet-place-by-john-krasinski-film-analysis-essay

"A Quiet Place by John Krasinski: Film Analysis," StudyMoose , 12-Feb-2024. [Online]. Available: https://studymoose.com/a-quiet-place-by-john-krasinski-film-analysis-essay. [Accessed: 17-Sep-2024]

StudyMoose. (2024). A Quiet Place by John Krasinski: Film Analysis . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/a-quiet-place-by-john-krasinski-film-analysis-essay [Accessed: 17-Sep-2024]

- Beautiful Scenery of Mery Quiet Place Pages: 2 (354 words)

- Exploring the Profound Realities of War: An Analysis of "All Quiet on the Western Front" Pages: 2 (575 words)

- Quiet Logistics Case Analysis: Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities And Recommendation Of Alternatives Pages: 5 (1403 words)

- All Quiet On The Western Front Novel Analysis Pages: 4 (1026 words)

- Analysis of Peter Leer's character and the influence of family background in "All Quiet on the Western Front" Pages: 2 (558 words)

- An Analysis of the Two Themes in All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque Pages: 2 (540 words)

- Analysis of "All Quiet On The Western Front" Pages: 3 (624 words)

- Review Of The Alfred Hitchcock's Film "Psycho": Groundbreaking Film In The History Of American Film Industry Pages: 5 (1466 words)

- Book Review of Not So Quiet Pages: 5 (1489 words)

- All Quiet on the Western Front Literary Devices essay Pages: 3 (652 words)

👋 Hi! I’m your smart assistant Amy!

Don’t know where to start? Type your requirements and I’ll connect you to an academic expert within 3 minutes.

University of Notre Dame

Fresh Writing

A publication of the University Writing Program

- Home ›

- Essays ›

Silence Is Golden: A Visual Analysis of A Quiet Place

By Christina Park

Published: July 31, 2019

A horror film is a lot like bleu cheese. You either love it or you hate it. There is rarely ever an in-between. Of those people who do enjoy horror, some watch it purely for the thrill of the scare and the adrenaline rush that keeps your heart pumping and your muscles tense. Others, however, watch horror for the plot and the bone-chilling backstory that messes with your mind and makes you think. Whether you associate with the former or the latter, the 2018 film A Quiet Place has what you are looking for. It has jump-scares, terrifying monsters, and life-or-death odds, but it also has deeper themes interwoven into its gripping plot. Many acclaim the film for its strong portrayal of parental love, the sacrifices that accompany parenting, and the great fears every parent has for their children. Others find feminist ideas about strength and matriarchy in the main female characters. While both of these themes and others are present during the film, the entire plot also encompasses a compelling and overarching message about silence. A Quiet Place combines elements of modern horror with minimal dialogue in a way that emphasizes the art of listening and the value of meaningful communication in the midst of a society that is consumed by countless voices and opinions.

In multiple scenes throughout A Quiet Place , we are given glimpses of media that point toward its questionable role in our society as an outlet for noise. When the characters are seen walking through the abandoned town, newspapers are blowing around among the garbage and other abandoned items on the sidewalks. Instead of just being placed there as a filler or thoughtless prop, these papers add to the underlying plot. A few minutes into the first scene, a newspaper blows open and the front page is visible for a moment. It reads "It's Sound!" in large letters, referring to the realization that the creatures hunt using sound. Here, only a single, silent form of media is surviving in a world where noise is deadly. This hints at the notion that modern forms of media, which are often loud and overbearing, are not as important as they may seem. In an additional scene, we see a strategy room of sorts with a wall of snowy TVs. The appearance of these signal-less TVs shows us that media as we know it today is non-existent in this post-apocalyptic world, while the appearance of the newspapers shows that only a simplistic form of "old-school" media can still manage to survive. When compared with our society today, where we see the media's influence in everything we do, these small scenes beg the question: "What is the real importance of the media?" Today's media is constantly speaking out and adding noise to our lives, whether we want it to or not. When it was simply composed of journalism and newspapers, the media started out much quieter, solely speaking to audiences that wanted to listen. However, the dysfunctional examples of media in the film suggest that the modern media's booming voice is not as important as we may believe, and it may be distracting us from what really matters in the world around us.

In addition to this criticism of deafening media, we can see the representation of the creatures throughout A Quiet Place as yet another archetype for the media-encroached society as it stands today. These creatures have only one acute sense, hearing, and that is the only way they are able to hunt. In this way, they "feed off" of noise in a very literal sense. From the beginning of the film, the creatures seem to be unbeatable, with no small sound getting past their supernatural ears. In a similar but theoretical way to that of the creatures, society also feeds off of noise. Speaking out with one's opinions and beliefs is an inherently powerful thing, just as the creatures are all-powerful throughout the movie. However, these voices and opinions tend to build on each other, answering and arguing with one another until they reach a deafening pitch. By the ending scene of the film, the creatures' weakness is discovered, and it proves to be the same thing that has allowed them to thrive throughout the course of the movie: their sense of hearing. Too high of a pitch, like that created by Regan's malfunctioning hearing aid, is extremely painful to the creatures, debilitating them long enough for the Abbotts to overtake and kill them. Today's examples of heated social media arguments, flashy accusations, and fake news are representative of this dangerously high pitch of noise. Just like the destruction of the creatures, the same noise that society feeds on today may result in its ultimate demise and a state of chaos, if the frequency is allowed to climb any higher.

Another way in which A Quiet Place challenges societal norms with silence is through the eyes, or more literally the ears, of Regan, the daughter of the Abbott family, who can experience the world in ways others deafened by noise cannot. A short time into the movie, viewers are given clues that lead to an important discovery: Regan is deaf. This revelation adds a whole new layer to the plot of the story, while at the same time it lends a new respect to Regan's character. She is tasked with surviving in a world where noise means death, while not knowing what makes noise in the first place. In this way, we see the plot taking on a theme concerning disability in society. Regan portrays the immense difficulties many disabled people have to endure, and she exemplifies the misconceptions many have about the capabilities of this group of people. In an early scene, Regan is shown as irresponsible, and perhaps even culpable for her brother's death, when she gives him a toy that his parents had taken away from him. The toy makes noise, so their parents could only view it as a source of danger. Regan, on the other hand, sees a different perspective because she cannot hear it; she sees her brother's happiness in relation to the toy. In this way, Regan cannot be blamed completely for her actions because she saw a different side of the situation. In a similar way, the movie shows later on that the disabled can be better enabled than any "normal" person to take on certain situations. To that end, disabled people can provide a new perspective that others may not otherwise be able to experience.

The complete lack of music or noise that dominates the film allows us as viewers to connect with Regan and her disability in an intimate way, leading to a deeper appreciation and understanding of her strength and the power of silence. In the moments when we can hear the characters being stalked and chased by creatures, the stress of the situation rises and the suspense of the scene feels much like that of a typical horror film. However, when a similar scene plays out in Regan's perspective and all is quiet, the scene is still suspenseful, but it also takes on a clarity that can only come from silence. Without noise, our senses are not overstimulated, and we can focus better on what we see in the scene. By the end of the movie, we find that it is Regan who provides the main solution to debilitate and kill the creatures, a solution that stems from both her possession of hearing aids and her ability to see situations more clearly. Without her disability, she never could have known that her hearing aids could injure the creatures, and the clarity she experiences in these stressful situations allows her to come to this important conclusion before any of her family. Disability is often treated as a burden that can lower quality of life, but for Regan, it is just a different form of ability. As Regan shows us, silence is a powerful tool that can be used to our advantage if we allow ourselves to find it.

Although I have referred to A Quiet Place as a silent film, it does incorporate minimal sounds that accentuate the underlying messages of meaningful noise. During the most intense scenes, background music typical of horror movies is played, usually meant to build up suspense and thrill when the characters are in a scary situation. The viewer may not even consciously recognize that the music is playing until it abruptly cuts out, and the resulting silence is truly deafening. In these instances, we are meant to be viewing the scene through Regan's point of view. Sometimes we experience complete silence, while other times we experience a slight high-pitched ringing. The stark change from music to silence adds a deeper feeling to the intense scene, one that emphasizes the excessive stimulation that occurs when we are bombarded with noise. The realization that Regan experiences this choked silence all the time relates back to the idea that she sees situations from a different point-of-view, one that exemplifies the art of listening even though she cannot physically hear.

In addition to small samples of music, we are given a handful of powerful scenes in which the characters are able to speak aloud, and the gravity and importance of these situations is amplified by the stark contrast of sound against the silence of the rest of the film. During the two main dialogue scenes at the waterfall and in the sound-proof room, the characters' speeches are still hushed and cautious. There is a sense of physical relief through their facial expressions and body language. Because the characters hardly ever speak aloud to each other, dialogue adds a strong sentiment to the scenes that would had otherwise been lost. This is a direct example of the power of silence and the importance and meaning communication can have when it is not just noise.

From the start, A Quiet Place sets the stage for a powerful message hidden in a clever and entertaining plot. Silence in film is very uncommon, which places this film in a genre all its own. At the same time, it argues a strong point about the future of society and media. Listening to one another, whether it be through speech or action, is truly an art that has been lost in the jumble of media, politics, and social outcry that exists in our society today. Through its setting, plot, characters, creatures, and lack of dialogue, A Quiet Place creates a story that questions society's motives for being distracting and loud. In an interview, director and lead male actor John Krasinski describes the Abbott family's struggle when he says, "Living silently is impossible" ("A Quiet Place," YouTube). This is a fact proved throughout the movie, and it is also something that society struggles with in real life. Yes, living silently is impossible, but living loudly, without stopping to listen every once in a while, is not necessarily the answer either. If we want to avoid the societal "ruins" that the movie suggests, we must work to find a middle ground, where we speak only when we need to, listen fervently to those around us, and work diligently to be more observant and meaningful in our communication with others.

Works Cited

"A Quiet Place (2018) - Director John Krasinski Interview - Paramount Pictures." YouTube , uploaded by Paramount Pictures, 4 Feb. 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=oe0nJbdqzGE . Accessed 4 Sept. 2018.

"A Quiet Place (2018)." IMDb , www.imdb.com/title/tt6644200/ . Accessed 4 Sept. 2018.

Krasinski, John, director. A Quiet Place . Paramount Pictures, 2018.

- Interpretive arguments about art are often tasked with the difficult challenge of making an original claim and sufficiently grounding it in evidence from the art itself. How does Park's essay navigate those two sides (thesis and evidence)? Does it matter whether the connections that Park is making between the film and "modern media's booming voice" was intended by the film's director and co-writer, John Krasinski? In the absence of directorial intentionality, what evidence does Park use to defend her claims?

- This essay is a visual analysis, but it spends a good portion of its analysis not on the visual but on the audial, on sound. Such a focus is, of course, appropriate to the specific film it's analyzing, but what are the rhetorical ways in which the author perceives sound functioning? Can sound itself be "rhetorical," and if so, how might we understand its rhetorical function in relation to (and independent from) the very thing sound so often produces: language.

- Some readers of this essay may have seen A Quiet Place ; others may not have. Do we have a clear sense of whether Park is writing to one audience or the other? Another way to put it is, what is the ratio of description to analysis in her argument? If you've seen the film, is there too much description? If you haven't, is there too little?

If you'd like to see the original prompt for this essay, please contact Prof. Nathaniel Myers at [email protected] .

Christina Park

The inspiration for Christina Park's "Silence is Golden: A Visual Analysis of A Quiet Place "stems from her interests in psychological thrillers and in complex, evocative plots of both literary and film media. Originally from Tiffin, OH, Christina is a Biological Sciences major and a member of the class of 2022, currently living in Farley Hall. After graduation, she intends to pursue a graduate degree with a concentration in genetics and genomics research. Christina would like to thank her Writing & Rhetoric professor, Dr. Nathaniel Myers, for challenging her to reach outside of her comfort zone and become a stronger, more confident writer.

Our centuries-long quest for ‘a quiet place’

Associate Professor of Media Studies, Penn State

Disclosure statement

Matthew Jordan does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Penn State provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation US.

View all partners

The 2018 film “ A Quiet Place ” is an edge-of-your-seat tale about a family struggling to avoid being heard by monsters with hypersensitive ears. Conditioned by fear, they know the slightest noise will provoke a violent response – and almost certain death.

Audiences came out in droves to dip their toes into its quiet terror, and loved it: It raked in over $100 million at the box office and got a 95 percent rating on Rotten Tomatoes.

Like fairy tales and fables that dramatize cultural phobias or anxieties, the movie may be resonating with audiences because something about it rings true. For hundreds of years, Western culture has been at war with noise.

Yet the history of this quest for quietness, which I’ve explored by digging through archives, reveals something of a paradox: The more time and money people spend trying to keep unwanted sound out, the more sensitive to it they become.

Be quiet – I’m thinking!

As long as people have lived in close quarters, they’ve been complaining about the noises other people make and yearning for quiet.

In the 1660s, the French philosopher Blaise Pascal speculated , “the sole cause of man’s unhappiness is that he does not know how to stay quietly in his room.” Pascal surely knew it was harder than it sounds.

But in modern times, the problem seems to have gotten exponentially worse. During the Industrial Revolution, people swarmed to cities roaring with factory furnaces and shrieking with train whistles. German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer called the cacophony “torture for intellectual people,” arguing that thinkers needed quietness in order to do good work . Only stupid people, he thought, could tolerate noise.

Charles Dickens described feeling “ harassed, worried, wearied, driven nearly mad, by street musicians ” in London. In 1856, The Times echoed his annoyance with the “noisy, dizzy, scatterbrain atmosphere” and called on Parliament to legislate “a little quiet.”

It seems the more people started to complain about noise, the more sensitive to it they became. Take the Scottish polemicist Thomas Carlyle. In 1831, he moved to London.

“I have been more annoyed with noises,” he wrote , “which get free access through my open windows.”

He became so triggered by noisy peddlers that he spent a fortune soundproofing the study in his Chelsea Row house. It didn’t work. His hypersensitive ears perceived the slightest sound as torture, and he was forced to retreat to the countryside.

The war on noise

By the 20th century, governments all over the world were engaged in an endless war on noisy people and things. After successfully silencing the tug boats whose tooting tormented her on the porch of her Riverside Avenue mansion, Mrs. Julia Barnett Rice, the wife of venture capitalist Isaac Rice, founded the Society for the Suppression of Unnecessary Noise in New York in order to combat what she called “one of the greatest banes of city life.”

Counting as members over 40 governors, and with Mark Twain as their spokesman, the group used its political clout to get “quiet zones” established around hospitals and schools. Violating a quiet zone was punishable by fine , imprisonment or both.

But focusing on noise only made her more sensitive to it. Like Carlyle, Rice turned to architects and built a quiet place deep under the ground , where her husband, Isaac, could work out his chess gambits in peace.

Inspired by Rice, anti-noise organizations sprang up around the globe. After World War I, with ears across Europe still ringing from explosions, the transnational culture war against noise really took off.

Cities all over the world targeted noisy technologies, like the Klaxon automobile horn , which Paris, London and Chicago banned by ordinance in the 1920s. In the 1930s, New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia launched a “noiseless nights” campaign aided by sensitive noise-measuring devices stationed throughout the city. New York passed dozens of laws over the next several decades to muzzle the worst offenders, and cities throughout the world followed suit. By the 1970s, governments were treating noise as environmental pollution to be regulated like any industrial byproduct.

Planes were forced to fly higher and slower around populated areas, while factories were required to mitigate the noise they produced. In New York, the Department of Environmental Protection – aided by a van filled with sound-measuring devices and the words “noise makes you nervous & nasty” on the side – went after noisemakers as part of “Operation Soundtrap.”

After Mayor Michael Bloomberg instituted new noise codes in 2007 to ensure “well-deserved peace and quiet,” the city installed hypersensitive listening devices to monitor the soundscape and citizens were encouraged to call 311 to report violations.

Consuming quietness

Yet legislating against noisemakers rarely satisfied our growing desire for quietness, so products and technologies emerged to meet the demand of increasingly sensitive consumers. In the early 20th century, sound-muffling curtains , softer floor materials, room dividers and ventilators kept the noise from the outside from coming in, while preventing sounds from bothering neighbors or the police.

But as Carlyle, Rice and the family in “A Quiet Place” found out, creating a sound-free lifeworld is nearly impossible. Certainly, as Hugo Gernsback learned with his 1925 invention the Isolator – a lead helmet with viewing holes connected to a breathing apparatus – it was impractical.

No matter how thoughtful the design, unwanted sound continued to be a part of everyday life.

Unable to suppress noise, disquieted consumers started trying to mask it with wanted sound, buying gadgets like the Sleepmate white noise machine or by playing recorded sounds of nature, from breaking waves to rustling forests, on their stereos.

Today, the quietness industry is a booming international market. There are hundreds of digital apps and technologies created by psychoacoustic engineers for consumers, including noise cancellation products with adaptive algorithms that detect outside sounds and produce anti-phase sonic waves, rendering them inaudible.

Headphones like Beats by Dr. Dre promise a life “Above the Noise”; Cadillac’s “Quiet Cabin” claims it can protect people from “the silent horror film out there.”

The marketing efforts for these products aim to convince us that noise is intolerable and the only way to be happy is to shut out other people and their unwanted sounds. This same fantasy is mirrored in “A Quiet Place”: The only moment of relief in the whole “silent horror film” is when Evelyn and Lee are wired in together, swaying gently to their own music and silencing the world outside their earbuds.

In a Sony ad for their noise canceling headphones, the company depicts a world in which the consumer exists in a sonic bubble in an eerily empty cityscape.

Content as some may feel in their ready-made acoustic cocoons, the more people accustom themselves to life without unwanted sounds from others, the more they become like the family in “A Quiet Place.” To hypersensitized ears, the world becomes noisy and hostile.

Maybe more than any alien species, it’s this intolerant quietism that’s the real monster.

- Right to silence

- Urban noise

Professor of Indigenous Cultural and Creative Industries (Identified)

Communications Director

Associate Director, Post-Award, RGCF

University Relations Manager

2024 Vice-Chancellor's Research Fellowships

Script Analysis: “A Quiet Place” — Part 4: Themes

Scott Myers

Go Into The Story

Read the script for the hit horror movie and analyze it all this week.

Reading scripts. Absolutely critical to learn the craft of screenwriting. The focus of this bi-weekly series is a deep structural and thematic analysis of each script we read. Our daily schedule:

Monday: Scene-By-Scene Breakdown Tuesday: Plot Wednesday: Characters Thursday: Themes Friday: Dialogue Saturday: Takeaways

Today: Themes.

I have this theory about theme. In two parts. First, a principle: Theme = Meaning. What does the story mean? Second, while there is almost always a Central Theme, there are multiple other Sub-Themes at play in a story. Therefore the question, What does a story mean takes on several layers of meaning?

Time to ponder themes in A Quiet Place . You may download a PDF of the script — free and legal — here .

Screenplay by Bryan Woods & Scott Beck and John Krasinski, story by Bryan Woods & Scott Beck.

IMDb plot summary: In a post-apocalyptic world, a family is forced to live in silence while hiding from monsters with ultra-sensitive hearing.

Writing Exercise: Explore the themes in A Quiet Place . What is its Central Theme? What are some of the related Sub-Themes?

Tomorrow we shift our focus to the script’s dialogue.

Major kudos to Mark Furney for doing this week’s scene-by-scene breakdown.

To download a PDF of the breakdown for A Quiet Place , go here .

For Part 1, to read the Scene-By-Scene Breakdown discussion, go here .

For Part 2, to read the Major Plot Points discussion, go here .

For Part 3, to read Characters discussion, go here .

To access 69 analyses of previous movie scripts we have read and discussed at Go Into The Story, go here .

I hope to see you in the RESPONSE section about this week’s script: A Quiet Place .

Written by Scott Myers

Text to speech

Advertisement

Supported by

Making the Sound of Silence in ‘A Quiet Place’

- Share full article

By Mekado Murphy

- April 5, 2018

In the horror film “ A Quiet Place ,” a family is afraid of themselves going bump in the night.

The postapocalyptic tale, which opens April 6, is propelled by one central menace: creatures with enhanced hearing that attack when they detect noise. Living isolated in the woods, a couple and their children have crafted a very hushed existence to keep the threat at bay: they walk barefoot, communicate via sign language, and play Monopoly with cotton game pieces.

When characters have to keep mum to stay alive, sound design can go to some innovative places. Anxious moments are created from the slightest creaks of a floor, footsteps on sand or even a heartbeat. Being inventive with sound, and frequently with the absence of it, was the idea that propelled the director, John Krasinski, who also stars in the movie with his wife, Emily Blunt.

[ Read our review of “A Quiet Place.” ]

“We live in a world now where you see all these movies, like Marvel movies, and there’s so much sound going on, so many explosions,” Mr. Krasinski said during an interview in New York. “ I love those movies, but there’s something about all that noise that assaults you, in a way. We thought, what if you pulled it all back? Would that make it feel just as disconcerting and just as uncomfortable and tense?”

To help make quiet frightening, Mr. Krasinski worked with the sound editors Ethan Van Der Ryn and Erik Aadahl , who have experience with the loud (“Godzilla”) and the louder (“Transformers”), but were interested in taking things down more than a few notches.

They worked to create what they called “sound envelopes,” putting audiences in a character’s shoes to hear what they hear and how they might hear it. The most intriguing one was for the young Regan, who is deaf and played by the deaf actress Millicent Simmonds. Regan wears a cochlear implant that gives her extremely minimal hearing; she has more of a physical sense of presence than an auditory one. For that, the editors wanted to mimic the feeling of being in an anechoic chamber, a room that absorbs sound to the point where all you can hear are the heightened noises of your own body. Regan’s envelope is rendered with a kind of low, muffled feel punctuated by the gentle pulse of her heart. But when she takes the hearing aid out, we experience a moment of complete screen silence, an idea that Mr. Krasinski debated with his colleagues.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

The Making Of A Quiet Place, by John Krasinski

Once Jim in The Office. Now director of this year’s most high-concept chiller. John Krasinski writes exclusively for Empire about his journey to A Quiet Place , and how the near-silent film became a family affair.

People ask me if I always wanted to be a director. And the truth is, no. When I first started out, I felt so lucky to be able to make a living as an actor it didn’t even cross my mind... and I didn’t want to jinx it. I was never one of those actors that said, “Well, when this acting thing is over… I’ll just direct.” I had way too much respect for the directors I had worked with to view the transition as some kind of foregone conclusion.

In order for me to choose to direct something, I have to feel that I am the best person for the job.

My first directing gig actually came about by total happenstance. Before I got The Office I had adapted this book by David Foster Wallace that had meant a great deal to me called Brief Interviews With Hideous Men . I remember The Office had just come on the air and I was having lunch with Rainn. At the time I was looking for a director to direct the movie and so I asked him for his opinion. His response? “Why don’t you just direct it yourself?” My mouth opened, but no response came. Then he said, “Listen, you now know this material better and care about it more than anyone. So just direct it.”

Not only did that line inspire me to take on my first movie as a director, but those words have become the exact criteria for what it is I choose to direct. I am well aware of the large and vast pool of extremely talented directors out there. And the truth is, most scripts I read, I’d love to see directed by one of those names. In order for me to choose to direct something, I have to feel that I am the best person for the job, that I have a unique connection to a piece of material, and can see it more clearly than I think anyone else could. That’s certainly what happened on A Quiet Place ... Though, yet again, it wasn’t initially my idea.

A Quiet Place first came to me as a spec script that the producers Drew Form and Brad Fuller had with Paramount. We were prepping for [TV series] Jack Ryan and Drew said to me, “Hey, quick question. Would you ever do a genre movie?” “You mean like a horror movie?” I asked. “I can’t watch horror movies, I’m way too scared. But yeah, maybe I could act in one if it was a cool idea.” So then he pitched me the one-liner — a family who can’t make a sound… or terrible things happen. I was immediately hooked.

At the time, we had just had our second daughter, Violet. So Emily and I were actually living through the terrifying first days of new parenthood. I was already an open nerve of emotions and fears — so as I read through the spec script I couldn’t help but obsess over the idea that this story could be so much more than just a scary movie. It could actually be one of the best metaphors for parenthood ever: “What would you REALLY do for your kids?” I immediately started writing down pages and pages of ideas. Those ideas quickly turned into scenes and I suddenly found myself rushing down the stairs to enlist my secret weapon: my wife. I’ll never forget Emily sitting on the couch, watching me bounce all over the living room as I pitched her one new scene after the next. I may or may not have been out of breath as I finally finished (definitely out of breath) and looked up to her. And then? Silence. I remember Emily just looking back at me with the most curious look on her face. (“Oh God, she hated it.”) Then suddenly — after a brilliantly delivered stage pause, btw — she finally said, “You need to direct this.” By the time I called the producers back only 48 hours later, I was indeed agreeing to be in the movie… if they would let me rewrite it... and direct.

After that phone call, we were off to the races. I finished the script in three months just before Christmas and by mid-January I was in idyllic upstate New York, scouting for the perfect location. And boy did we find it in this beautiful 19th century farm in the town of Pawling, NY. It was almost weird how perfect this place was. I remember crew members literally not believing me when I told them I hadn’t been there before I wrote the script. There was a beautiful farmhouse that faced a large weather-worn barn about 50 or 60 yards away, exactly as I’d written it. Those buildings were surrounded by hundreds of acres of crop fields, exactly as I’d written it. There was even a waterfall right nearby EXACTLY as I’d—you get the point! It was magic. And the coolest part was, not only was the location perfect, but there was a horse-riding school nearby that wasn’t currently in use, that we got to use as our soundstages. So for 90 per cent of the shoot, every member of the cast and crew got to call that magical farm home.

It wasn’t the convenience that made it all so special: it was the vibe. Everybody came on set and the first thing they saw was the farm and the last thing they saw was the farm. The dust in the air was from real corn; we got to shoot scenes with real sunrises and real sunsets. Some days it didn’t even feel like we were making a movie. It just felt like we were all at summer camp.

When it came to casting the movie, one of the most important things to me was that we were able to cast a deaf actress in the role of my daughter. I wanted to have someone who could not only understand the world of this character, but also help me to understand. Someone I could learn from. Well, it just so happens that one of the best actors I can now say I have had the pleasure of working with is deaf. Her name is Millicent Simmonds and she is phenomenal in every way. I was first introduced to Millie’s work by the tremendous casting director Laura Rosenthal, who had just cast Todd Haynes’ movie Wonderstruck . When I called Laura and pitched her the part she actually said the words, “There’s only one girl for this.” When I reached out to Todd directly his response was, “Millie is not only a fantastic actress… but one of the more special human beings you’ll ever meet.” Boy, was he right.

My luck continued in my quest to cast the part of my son. As luck would have it, the exact week I started casting happened to be the week of the SAG awards. Emily had been nominated for her part in The Girl On The Train , so we were there. After the ceremony, Emily and I were walking into the afterparty when one of my agent’s old assistants came running up to me. “Hey man, I’m an agent now and there’s this kid, Noah, I represent. I haven’t read your script but you gotta put him in your movie!” I don’t think he even knew what age the kid was supposed to be, but he told me Noah was in The Night Manager , and that Noah had just finished shooting Suburbicon . So I wrote to George Clooney to ask about him. His email back was almost exactly what Todd had said about Millie: “Not only is Noah one of the greatest child actors I’ve ever worked with (and I worked with them all on E.R. ), but he’s one of the best actors I’ve worked with, period. Not to mention, he’s just the greatest kid.” Well, now I can attest he was exactly right. Noah is amazing.

When it came to casting the part of my wife, Emily had actually recommended several different actresses based on my pitch of some of the scenes. Her being in the movie, we really hadn’t even considered. We had certainly talked about working together one day, but we never wanted the story of our being married to supersede the story of the movie we chose to do. So up until this point we just had never found the right script. Then one day Emily and I were on a flight to LA together. Emily asked if I felt far enough along with the script for her to read it. I was. But to be honest, holding her opinion higher than anyone’s, I have to admit I was the most nervous to have her read it. The flight continued and I was deeply engrossed in some huge action movie, when a shadow appeared next to me. I looked up to see Emily standing there. Her face looked different. At first, I thought she was feeling sick. Just before I was able to reach for a barf bag Emily simply said, “I have to play this part.” I was so stunned I asked her, “What?” She replied, “You can’t let anyone else play this part. I have to do it.”

I have to be completely honest when I tell you that that exact moment — having this woman that I admire and respect agree to do this movie with me — was the best compliment of my career.

The other question I get about directing is what is it like to direct myself. Well, for starters, it’s tough to deal with such a diva. But once we realise we’re both just here to make the best movie, things go fine. In all seriousness, I have actually found there are great advantages of being an actor in the movies I direct. One of the biggest is being able to stay in the scene with my actors. Sometimes, having a director behind the monitors calling cut after every take can ruin a flow or a groove that the actors are getting into. Especially in a movie like this, where there are so many intense scenes and emotional scenes, it helped a whole lot to keep the scene going, giving small notes right then and there in the moment. It almost felt at times like we were doing a play.

We shot on film, which was an easy decision and a hard fight.

The other major advantage is that on many occasions it just saves a ton of time. Having one of your lead actors on set every minute that you are… is great! Actually, writing these next benefits down it sounds like some riddle delivered by Yoda, haha, but it’s true! If I think of a last-minute shot I need to add me into — bam, there I am! If I need to make sure I don’t take too long in hair and make-up — bam, I pull myself out of hair and make-up. And if I’m shooting on the top of a silo with only ten minutes of perfect light, I don’t have to worry about me suddenly turning and asking, “What’s my motivation?” I’d already talked to myself about that the week before.

Our DP was Charlotte Bruus Christensen, who had shot The Girl On The Train , and Emily had had such a great experience with her that she was at the top of my list. I was extremely impressed by her work not only in that movie, but all her other movies as well. For our film, I was especially taken by all the movies she had done with Thomas Vinterberg. Charlotte has this unique perspective, and I thought she would be perfect to bring an intangible magic to the film. She’s a monster talent. We shot on film, which was an easy decision and a hard fight. There’s all sorts of reasons and benefits for shooting on digital; I shot my last movie on digital and loved it. But there was something about this movie that I wanted to harken back to a more classic look, a feeling of nostalgia one could immediately connect to. We both decided the only way to capture that was to shoot on film.

I had a lot of fun coming up with all these different visuals to explain that this family cannot make any noise, not ever. That’s why there’s paint on the floor of the house, showing where to put your feet to avoid creaking boards, and paths made of sand around the farm. It was also fun to play with perspective. The idea that you can hear a footstep on a close-up lens, but when you jump to medium you can’t. Things like that deliver information and the rules of the film to the audience subconsciously. Making a mostly silent movie was thrilling… and terrifying. But there were upsides. I remember one day we were shooting by this beautiful river. Aaaaand that just happened to be the day that two guys decided to race their ATVs in the woods right behind us. We had crew members running through the woods trying to find them to tell them to stop, but could never get to them. Normally you lose a whole day of shooting if that happens. The dialogue would be unusable. But in our scene? There was no dialogue. It didn’t matter.

Honestly, one of the most amazing aspects of this process has been working with our incredible sound team. This film is a sound department’s dream, because the tiniest sound matters. Usually you might just put one big atmos microphone up to record ambient sound. Here, the sound guys came for a full weekend to capture different wind directions, and recorded at multiple times of day to catch all the local insects. They even put lapel mics on individual corn stalks to get all these layers of sound. Marco Beltrami, who’s incredible, is writing the score, and the first thing he did was call them and say, “You gotta give me all of that because I can compose with it!” Marco said it was only the second time in his career he’d been able to visit a set; he was so excited after coming to visit that at the end he just turned to us and said, “Man, I gotta get home and start writing.”

And then there’s the creature. Oh man, I can’t even describe how I feel about the fact that ILM is working on my movie. We have Scott Farrar supervising our VFX, one of the original ILM guys. In between takes I would sit totally engrossed as he casually told us how they shot the Imperial Star Destroyer in Star Wars , or how they shot the Raptor kitchen scene in Jurassic Park . I remember someone telling me that one of the strongest things someone can do is say, “I don’t know.” So the first thing I told Scott was, “Look, I’ve never done this before, so I’m going to tell you my ideas and you tell me how I can make them all better.” We spent the whole day talking about shots, and he gave me incredible tips like making sure to move the camera a little on the creature shots. They learned on Transformers that a static shot, no matter what you do with it, is just not that scary — but if the camera moves and the creature’s head goes out of frame for a moment, it seems more real.

One cool thing about working with VFX is that you learn very fast… you have to!

As I’m sure is evident from my ramblings, the experience of this movie was incredible. I remember the last night we shot, one guy in the crew came up to say goodbye and as he turned to leave, actually laughed and said, “There’s something about this one. I don’t know. It feels special.” And he’s right. I have to give a tremendous amount of credit and gratitude to Paramount. It’s not every day that a major studio allows you to go off and shoot a mostly silent movie. But, from the moment I pitched them what I hoped this movie could be, they saw it. It’s special because it was treated as special, by every single person that came on board. This is one of those rare experiences where it all came together in the right way. I know you don’t get many experiences like that. And, hey, if I never have another one as good as this, that’d be okay. I just feel lucky as hell to have been able to have one that I care this much about.

Hear John Krasinski talk A Quiet Place in our Spoiler Special Podcast episode , and read about some of the most surprising things he told us here .

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Silently Regressive Politics of “A Quiet Place”

The success of “A Quiet Place,” the new horror thriller directed by John Krasinski, is a sign of viewers craving emptiness, of a yearning for some cinematic white noise to drown out troubling thoughts and observations with a potently simple and high-impact countermyth. The noise of “A Quiet Place” is the whitest since the release of “ Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri ”; as horror films go, it’s the antithesis of “Get Out,” inasmuch as its symbolic realm is both apparently unconscious and conspicuously regressive.

“A Quiet Place” is the story of a white family living in rustic isolation that’s reduced to silence because a bunch of big, dark, stealthy, predatory creatures who can hear their every noise are marauding in the woods and, at any conspicuous sound, will emerge as if from nowhere and instantly maul them to death. I won’t spoil the plot twists, but Krasinski ultimately delivers a pair of exemplary images, a lone bearded man (whom he himself plays) with a rifle, and a lone woman (played by his real-life wife, Emily Blunt) aiming a rifle into the camera.

The movie is a fantasy of survivalism that starts eighty-nine days into the rampage. The Abbotts, a family of five—mother, Evelyn; father, Lee; Regan, a daughter of about eleven (Millicent Simmonds); Marcus, a son of about eight (Noah Jupe), and a small boy of about four named Beau (Cade Woodward)—are trawling a ghost city for supplies, wandering through a pharmacy and gathering medicine. (The characters’ first names are given on IMDb , though, to the best of my recollection, they’re not mentioned in the film itself.) The Abbotts are the only people making their way through town, across an old wooden bridge, and to their remote country farmhouse amid a series of other farms. If they’ve survived so far—and most of the action takes place later, more than a year into the invasion—it’s due in part to one circumstance: Regan is deaf (as Simmonds is in real life), and, as a result, the family is skilled in sign language, which enables them to communicate and strategize while eluding the monsters.

Except for its blaring music, “A Quiet Place” is in fact mostly a very quiet movie (with one clever, if obvious, element of sound design—shots suggesting Regan’s point of view remove all background sound and are delivered silent, to reproduce her deafness on the soundtrack and contrast it with the hearing of other characters and the enforced speechlessness of their environment). The farmhouse, however, has been the site of relentless labors—both the daily domestic work on which physical subsistence depends (the action suggests that Evelyn does most of that) and some high-tech wizardry that turns the family’s basement into an elaborate video-surveillance module, with cameras scattered throughout the wide property, more video screens at work than in the back room of a shopping mall, and strings of red lights that wind through the farmland and can be lit at the flip of a switch. (Scenes of Lee at work with wire and solder suggest that the electronics workshop is solely his domain.)

The Abbotts have to maintain their quiet (though Lee has discovered that, when there’s a big and steady sound nearby, such as the rush of a waterfall, it’s safe to speak, since the voices don’t escape it), and so, there’s almost no verbal dialogue in the film (there’s more dialogue in sign language, which is subtitled). The near-wordless soundtrack is a directorial choice on Krasinski’s part—as silent as its characters may be, “A Quiet Place” could easily have been transformed into a voluble movie, in which the characters’ thoughts and experiences would be delivered on the soundtrack, as interior monologues, even if they’re compelled not to express them aloud to each other. But Krasinski (who wrote the script with Bryan Woods and Scott Beck) chose to keep his characters blank and undefined, their memories and musings out of bounds. What dialogue there is (whether spoken or signed) is confined to the demands of the action (with one twist of psychology involving an element of guilt that figures only trivially in the plot).

The only moment of authentic inner expression, the acknowledgment of any identity at all, arises when, under siege from the creatures, Evelyn challenges Lee when their children are in danger: “Who are we? Who are we if we can’t protect them?” In that moment, “A Quiet Place” disgorges its entire stifled and impacted ideological content. The movie’s survivalist horror-fantasy offers the argument for turning a rustic farmhouse into a virtual fortress, for the video surveillance and the emergency lighting and, above all, the stash of firearms that (along with a bit of high-tech trickery that is too good to spoil) is the ultimate game changer, the ultimate and decisive defense against home intruders.

In effect, “A Quiet Place” is an oblivious, unself-conscious version of Clint Eastwood’s recent movies, such as “ The 15:17 to Paris ,” which bring to the fore the idealistic elements of gun culture while dramatizing the tragic implications that inevitably shadow that idealism. The one sole avowed identity of the Abbott parents is as their children’s defenders; their more obvious public identity is as a white rural family. The only other people in the film, who are more vulnerable to the marauding creatures, are white as well. In their enforced silence, these characters are a metaphorical silent—white—majority, one that doesn’t dare to speak freely for fear of being heard by the super-sensitive ears of the dark others. It’s significant that when characters—two white men—commit suicide-by-noisemaking, they do so by howling as if with rage, rather than by screeching or singing or shouting words of love to their families. (Those death bellows are the wordless equivalent of “I’m as mad as hell and I’m not going to take this anymore!”) Whether the Abbotts’ insular, armed way of life might put them into conflict with other American families of other identities is the unacknowledged question hanging over “A Quiet Place,” the silent horror to which the movie doesn’t give voice.

'A Quiet Place Part II' is another terrifyingly silent ride through a land of monsters

The first "A Quiet Place" turned on the death of a child: what it did to the Abbott family, how quickly and horribly widespread calamities affect children and what recovery from that particular trauma looked like.

Since it came out in 2018, the sudden alteration of daily life around the Covid-19 pandemic made real-life parenthood more difficult for everybody, too — not just in terms of marshaling resources but in terms of the already huge psychic burden of being responsible for another little person who doesn’t know how to be careful. The disease, which felt like it was everywhere, at first led to a whole host of terrifying questions for parents: Did I orphan him by kissing his scraped knee? Have I traumatized him by refusing to let him play at his friends’ house? Should I have kept him out of day care longer?

Opinion The pandemic's made me rethink much of my life — including my parenting style

John Krasinski’s “A Quiet Place” and now its sequel externalize all these questions in the form of terrifying blind monsters with super-hearing. Break a glass, drop an empty soda can or cry out in pain from stepping on a nail and they’ll come crashing through the walls to disembowel you.

Krasinski uses the grammar of sci-fi to lull audiences into lowering their guard for just long enough to sneak up on them.

Krasinski's monsters are more visible than the coronavirus, but, somehow, so are all a parent's fears and efforts at mitigation of the last year, contained in a little coffin that the Abbotts in “A Quiet Place Part II” have built for their newborn — a soundproof box with an oxygen tube running into it, in which he can cry like a baby cries until he is old enough to stay quiet and keep everyone safe.

Shhhhhh. The movie is starting.

“A Quiet Place Part II” follows the first movie’s family, Lee (Krasinski), Evelyn (Emily Blunt, Krasinski’s IRL wife) and their two surviving children, 12-year-old Marcus (Noah Jupe) and 17 year-old Regan (a wonderful Millicent Simmonds). The first movie was Lee’s story; part two, appropriately, tells a story in two parts, following the kids. Marcus must learn to manage his home and take care of his new baby brother while big sister Regan — who is deaf — must figure out how to dispatch the monsters using their weakness to her hearing aid, which was discovered at the end of the first film.

I’ve never seen movies that amplify the experience of being around other people who might make a noise when you need them not to in quite the same way these movies do.

Her disability is, once again, the family’s most significant strength: Because of her, they all know American Sign Language and can live a normal-ish life with one another (especially by comparison to their ruined neighbor Emmett) and then have a weapon against the monsters.

I’ve never seen movies that amplify the experience of being around other people who might make a noise when you need them not to in quite the same way these movies do, and if you see the sequel in theaters, go in soft shoes and buy a snack that doesn’t come in a plastic bag. It's like feature-length “turn off your cellphone” ads but with some melancholy for the world that was alongside, of course, nearly unbearable tension.

Opinion 'Army of the Dead' almost makes you root for the zombies. At least their lines are better.

The second film isn’t as efficient as its predecessor, but it enlarges the world of the first in inventive ways. The line between horror and science fiction has always been blurry, and Krasinski uses the grammar of sci-fi in this film to lull audiences into lowering their guard for just long enough to sneak up on us. At one point, for instance, we watch with transfixed parents at a Little League game as a ball of fire descends slowly from the sky, its languorous descent a clever distraction from the terrifying speed of the films’ monsters.

The playwright Anton Chekhov famously told a friend that "one must never place a loaded rifle on the stage if it isn't going to go off”; Krasinski creates a full-blown Chekhov’s gun show with this film, using the limited oxygen supplies, breakable lifesaving devices, small-but-vital weaknesses and booby traps strewn throughout. Keeping track of them is stressful in the best way: When watching something exciting, my 4-year-old often climbs up me like I’m a tree and stands on my shoulders until the moment has passed, and while I didn’t exactly do that to the person in the row behind me, I thought about it. (I also thought a lot about my kid.)

Opinion We want to hear what you THINK. Please submit a letter to the editor.

But one of the most striking things about these films is how brief they are. The first movie didn’t even hit the 90-minute mark before the credits started to roll; for all its expansiveness, the sequel has barely 10 minutes on its predecessor.

The other shocking aspect to the movie is that it’s a ton of fun. “Army of the Dead” bills itself as the biggest and most eccentric horror summer blockbuster of the season, but I’d rather watch “A Quiet Place Part II” twice more than “Army” ever again. Krasinski's film is an adventure movie, a grisly family film, a thriller and a domestic drama, all without breaking a sweat. The characters will stay with you and the themes will resonate, but you’ll also be glad you went back to the movies.

Sam Thielman is a reporter and critic based in New York. He is the creator, with film critic Alissa Wilkinson, of Young Adult Movie Ministry, a podcast about Christianity and movies, and his writing has been featured in The Columbia Journalism Review, The Guardian, Talking Points Memo and Variety. In 2017 he was a political consultant for Comedy Central's "The President Show."

Home — Essay Samples — Entertainment — Film Analysis — The Role Music Plays in the Film a Quiet Place

The Role Music Plays in The Film a Quiet Place

- Categories: Film Analysis Sound

About this sample

Words: 579 |

Published: May 19, 2020

Words: 579 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Heisenberg

Verified writer

- Expert in: Entertainment Science

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 416 words

6 pages / 2606 words

2 pages / 939 words

2.5 pages / 1050 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Film Analysis

Suzanne Collins' dystopian novel series, "The Hunger Games," has captured the imaginations of readers and moviegoers alike with its compelling themes that resonate with contemporary society. The story, set in a bleak future [...]

The film 'Schindler's List' begins in September 1939 in the Krakow village of Poland, which was occupied by German troops during World War II. In the case of Jews, they register their family number and more than 10,000 Jews [...]

Inside out is a film that revolves around Riley and takes us on an emotional journey she experiences throughout the entire film. There are three main psychological principles that are very evident to me in the reading as well as [...]

Silver Linings Playbook is a 2012 American romantic-comedy-drama film written and directed by David O.Russell. The film was based on Matthew Quick’s 2008 novel The Silver Linings Playbook. It stars Bradley Cooper and Jennifer [...]

Introduction of the movie "Fight Club" and its initial reception Mention of the movie's actual genre and surprise ending Brief summary of the movie's plot, including the protagonist's transformation into Tyler [...]

While the short film, 2081, has many common similarities with its adapted version of the short story, Harrison Bergeron, they differ from each other to the point where it can change our whole view on who Harrison Bergeron [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Forgot Your Password?

New to The Nation ? Subscribe

Print subscriber? Activate your online access

Current Issue

How Historical Fiction Redefined the Literary Canon

In contemporary publishing, novels fixated on the past rather than the present have garnered the most attention and prestige.

The 68th National Book Awards at Cipriani Wall Street, 2017.

On Friday, the judges of the National Book Awards will announce the long list for this year’s prize for fiction. On Monday, the Booker Prize jury will winnow their own long list down to just six finalists. And while betting on literary prizes is something of a fool’s game, odds are both lists will cover quite a lot of historical ground. The likely honorees include Percival Everett’s James , set in the antebellum South; Tommy Orange’s Wandering Stars , which spans 150 years, beginning in the 1860s; Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s Long Island Compromise , split between 1980, World War II, and the present; and Claire Messud’s This Strange Eventful History , whose multigenerational plot runs from 1940 to 2010. Two different prizes, with two different juries, with two lists of books that—I’d wager—will have a lot in common.

That’s because, over the last several decades, a quiet revolution has taken place in American fiction: The novels recognized by major literary prizes have largely abandoned the present in favor of the past. Contemporary fiction has never been less contemporary.

If we look back to the middle of the 20th century, we can see that the kinds of books that were short-listed for the Pulitzer Prize or the National Book Award then were mostly about contemporary life: J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye , Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man , and a host of others by the likes of Saul Bellow, John Cheever, and John Updike. And these aren’t outliers. Between 1950 and 1980, about half of the novels short-listed for these and the National Book Critics Circle Award were set in the present, narrating “the way we live now” in all its complexity.

Fast-forward to the present, and the past has taken over. A historical novel has won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 12 out of the last 15 years, and historical fiction has made up 70 percent of all novels short-listed for these three major American prizes since the turn of the 21st century. Today, writers like Colson Whitehead, Viet Thanh Nguyen, Louise Erdrich, and Hernan Diaz are less interested in the way we live now than the way we were .