ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

A comparative analysis of student performance in an online vs. face-to-face environmental science course from 2009 to 2016.

- Department of Biology, Fort Valley State University, Fort Valley, GA, United States

A growing number of students are now opting for online classes. They find the traditional classroom modality restrictive, inflexible, and impractical. In this age of technological advancement, schools can now provide effective classroom teaching via the Web. This shift in pedagogical medium is forcing academic institutions to rethink how they want to deliver their course content. The overarching purpose of this research was to determine which teaching method proved more effective over the 8-year period. The scores of 548 students, 401 traditional students and 147 online students, in an environmental science class were used to determine which instructional modality generated better student performance. In addition to the overarching objective, we also examined score variabilities between genders and classifications to determine if teaching modality had a greater impact on specific groups. No significant difference in student performance between online and face-to-face (F2F) learners overall, with respect to gender, or with respect to class rank were found. These data demonstrate the ability to similarly translate environmental science concepts for non-STEM majors in both traditional and online platforms irrespective of gender or class rank. A potential exists for increasing the number of non-STEM majors engaged in citizen science using the flexibility of online learning to teach environmental science core concepts.

Introduction

The advent of online education has made it possible for students with busy lives and limited flexibility to obtain a quality education. As opposed to traditional classroom teaching, Web-based instruction has made it possible to offer classes worldwide through a single Internet connection. Although it boasts several advantages over traditional education, online instruction still has its drawbacks, including limited communal synergies. Still, online education seems to be the path many students are taking to secure a degree.

This study compared the effectiveness of online vs. traditional instruction in an environmental studies class. Using a single indicator, we attempted to see if student performance was effected by instructional medium. This study sought to compare online and F2F teaching on three levels—pure modality, gender, and class rank. Through these comparisons, we investigated whether one teaching modality was significantly more effective than the other. Although there were limitations to the study, this examination was conducted to provide us with additional measures to determine if students performed better in one environment over another ( Mozes-Carmel and Gold, 2009 ).

The methods, procedures, and operationalization tools used in this assessment can be expanded upon in future quantitative, qualitative, and mixed method designs to further analyze this topic. Moreover, the results of this study serve as a backbone for future meta-analytical studies.

Origins of Online Education

Computer-assisted instruction is changing the pedagogical landscape as an increasing number of students are seeking online education. Colleges and universities are now touting the efficiencies of Web-based education and are rapidly implementing online classes to meet student needs worldwide. One study reported “increases in the number of online courses given by universities have been quite dramatic over the last couple of years” ( Lundberg et al., 2008 ). Think tanks are also disseminating statistics on Web-based instruction. “In 2010, the Sloan Consortium found a 17% increase in online students from the years before, beating the 12% increase from the previous year” ( Keramidas, 2012 ).

Contrary to popular belief, online education is not a new phenomenon. The first correspondence and distance learning educational programs were initiated in the mid-1800s by the University of London. This model of educational learning was dependent on the postal service and therefore wasn't seen in American until the later Nineteenth century. It was in 1873 when what is considered the first official correspondence educational program was established in Boston, Massachusetts known as the “Society to Encourage Home Studies.” Since then, non-traditional study has grown into what it is today considered a more viable online instructional modality. Technological advancement indubitably helped improve the speed and accessibility of distance learning courses; now students worldwide could attend classes from the comfort of their own homes.

Qualities of Online and Traditional Face to Face (F2F) Classroom Education

Online and traditional education share many qualities. Students are still required to attend class, learn the material, submit assignments, and complete group projects. While teachers, still have to design curriculums, maximize instructional quality, answer class questions, motivate students to learn, and grade assignments. Despite these basic similarities, there are many differences between the two modalities. Traditionally, classroom instruction is known to be teacher-centered and requires passive learning by the student, while online instruction is often student-centered and requires active learning.

In teacher-centered, or passive learning, the instructor usually controls classroom dynamics. The teacher lectures and comments, while students listen, take notes, and ask questions. In student-centered, or active learning, the students usually determine classroom dynamics as they independently analyze the information, construct questions, and ask the instructor for clarification. In this scenario, the teacher, not the student, is listening, formulating, and responding ( Salcedo, 2010 ).

In education, change comes with questions. Despite all current reports championing online education, researchers are still questioning its efficacy. Research is still being conducted on the effectiveness of computer-assisted teaching. Cost-benefit analysis, student experience, and student performance are now being carefully considered when determining whether online education is a viable substitute for classroom teaching. This decision process will most probably carry into the future as technology improves and as students demand better learning experiences.

Thus far, “literature on the efficacy of online courses is expansive and divided” ( Driscoll et al., 2012 ). Some studies favor traditional classroom instruction, stating “online learners will quit more easily” and “online learning can lack feedback for both students and instructors” ( Atchley et al., 2013 ). Because of these shortcomings, student retention, satisfaction, and performance can be compromised. Like traditional teaching, distance learning also has its apologists who aver online education produces students who perform as well or better than their traditional classroom counterparts ( Westhuis et al., 2006 ).

The advantages and disadvantages of both instructional modalities need to be fully fleshed out and examined to truly determine which medium generates better student performance. Both modalities have been proven to be relatively effective, but, as mentioned earlier, the question to be asked is if one is truly better than the other.

Student Need for Online Education

With technological advancement, learners now want quality programs they can access from anywhere and at any time. Because of these demands, online education has become a viable, alluring option to business professionals, stay-at home-parents, and other similar populations. In addition to flexibility and access, multiple other face value benefits, including program choice and time efficiency, have increased the attractiveness of distance learning ( Wladis et al., 2015 ).

First, prospective students want to be able to receive a quality education without having to sacrifice work time, family time, and travel expense. Instead of having to be at a specific location at a specific time, online educational students have the freedom to communicate with instructors, address classmates, study materials, and complete assignments from any Internet-accessible point ( Richardson and Swan, 2003 ). This type of flexibility grants students much-needed mobility and, in turn, helps make the educational process more enticing. According to Lundberg et al. (2008) “the student may prefer to take an online course or a complete online-based degree program as online courses offer more flexible study hours; for example, a student who has a job could attend the virtual class watching instructional film and streaming videos of lectures after working hours.”

Moreover, more study time can lead to better class performance—more chapters read, better quality papers, and more group project time. Studies on the relationship between study time and performance are limited; however, it is often assumed the online student will use any surplus time to improve grades ( Bigelow, 2009 ). It is crucial to mention the link between flexibility and student performance as grades are the lone performance indicator of this research.

Second, online education also offers more program choices. With traditional classroom study, students are forced to take courses only at universities within feasible driving distance or move. Web-based instruction, on the other hand, grants students electronic access to multiple universities and course offerings ( Salcedo, 2010 ). Therefore, students who were once limited to a few colleges within their immediate area can now access several colleges worldwide from a single convenient location.

Third, with online teaching, students who usually don't participate in class may now voice their opinions and concerns. As they are not in a classroom setting, quieter students may feel more comfortable partaking in class dialogue without being recognized or judged. This, in turn, may increase average class scores ( Driscoll et al., 2012 ).

Benefits of Face-to-Face (F2F) Education via Traditional Classroom Instruction

The other modality, classroom teaching, is a well-established instructional medium in which teaching style and structure have been refined over several centuries. Face-to-face instruction has numerous benefits not found in its online counterpart ( Xu and Jaggars, 2016 ).

First and, perhaps most importantly, classroom instruction is extremely dynamic. Traditional classroom teaching provides real-time face-to-face instruction and sparks innovative questions. It also allows for immediate teacher response and more flexible content delivery. Online instruction dampens the learning process because students must limit their questions to blurbs, then grant the teacher and fellow classmates time to respond ( Salcedo, 2010 ). Over time, however, online teaching will probably improve, enhancing classroom dynamics and bringing students face-to face with their peers/instructors. However, for now, face-to-face instruction provides dynamic learning attributes not found in Web-based teaching ( Kemp and Grieve, 2014 ).

Second, traditional classroom learning is a well-established modality. Some students are opposed to change and view online instruction negatively. These students may be technophobes, more comfortable with sitting in a classroom taking notes than sitting at a computer absorbing data. Other students may value face-to-face interaction, pre and post-class discussions, communal learning, and organic student-teacher bonding ( Roval and Jordan, 2004 ). They may see the Internet as an impediment to learning. If not comfortable with the instructional medium, some students may shun classroom activities; their grades might slip and their educational interest might vanish. Students, however, may eventually adapt to online education. With more universities employing computer-based training, students may be forced to take only Web-based courses. Albeit true, this doesn't eliminate the fact some students prefer classroom intimacy.

Third, face-to-face instruction doesn't rely upon networked systems. In online learning, the student is dependent upon access to an unimpeded Internet connection. If technical problems occur, online students may not be able to communicate, submit assignments, or access study material. This problem, in turn, may frustrate the student, hinder performance, and discourage learning.

Fourth, campus education provides students with both accredited staff and research libraries. Students can rely upon administrators to aid in course selection and provide professorial recommendations. Library technicians can help learners edit their papers, locate valuable study material, and improve study habits. Research libraries may provide materials not accessible by computer. In all, the traditional classroom experience gives students important auxiliary tools to maximize classroom performance.

Fifth, traditional classroom degrees trump online educational degrees in terms of hiring preferences. Many academic and professional organizations do not consider online degrees on par with campus-based degrees ( Columbaro and Monaghan, 2009 ). Often, prospective hiring bodies think Web-based education is a watered-down, simpler means of attaining a degree, often citing poor curriculums, unsupervised exams, and lenient homework assignments as detriments to the learning process.

Finally, research shows online students are more likely to quit class if they do not like the instructor, the format, or the feedback. Because they work independently, relying almost wholly upon self-motivation and self-direction, online learners may be more inclined to withdraw from class if they do not get immediate results.

The classroom setting provides more motivation, encouragement, and direction. Even if a student wanted to quit during the first few weeks of class, he/she may be deterred by the instructor and fellow students. F2F instructors may be able to adjust the structure and teaching style of the class to improve student retention ( Kemp and Grieve, 2014 ). With online teaching, instructors are limited to electronic correspondence and may not pick-up on verbal and non-verbal cues.

Both F2F and online teaching have their pros and cons. More studies comparing the two modalities to achieve specific learning outcomes in participating learner populations are required before well-informed decisions can be made. This study examined the two modalities over eight (8) years on three different levels. Based on the aforementioned information, the following research questions resulted.

RQ1: Are there significant differences in academic performance between online and F2F students enrolled in an environmental science course?

RQ2: Are there gender differences between online and F2F student performance in an environmental science course?

RQ3: Are there significant differences between the performance of online and F2F students in an environmental science course with respect to class rank?

The results of this study are intended to edify teachers, administrators, and policymakers on which medium may work best.

Methodology

Participants.

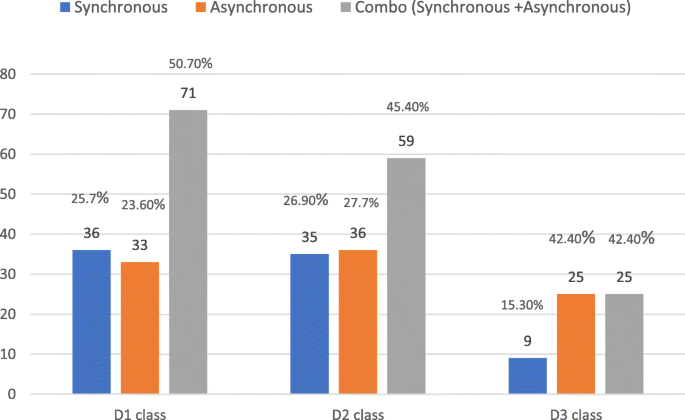

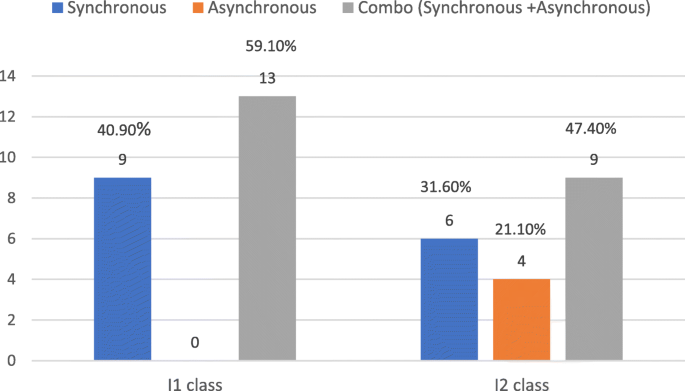

The study sample consisted of 548 FVSU students who completed the Environmental Science class between 2009 and 2016. The final course grades of the participants served as the primary comparative factor in assessing performance differences between online and F2F instruction. Of the 548 total participants, 147 were online students while 401 were traditional students. This disparity was considered a limitation of the study. Of the 548 total students, 246 were male, while 302 were female. The study also used students from all four class ranks. There were 187 freshmen, 184 sophomores, 76 juniors, and 101 seniors. This was a convenience, non-probability sample so the composition of the study set was left to the discretion of the instructor. No special preferences or weights were given to students based upon gender or rank. Each student was considered a single, discrete entity or statistic.

All sections of the course were taught by a full-time biology professor at FVSU. The professor had over 10 years teaching experience in both classroom and F2F modalities. The professor was considered an outstanding tenured instructor with strong communication and management skills.

The F2F class met twice weekly in an on-campus classroom. Each class lasted 1 h and 15 min. The online class covered the same material as the F2F class, but was done wholly on-line using the Desire to Learn (D2L) e-learning system. Online students were expected to spend as much time studying as their F2F counterparts; however, no tracking measure was implemented to gauge e-learning study time. The professor combined textbook learning, lecture and class discussion, collaborative projects, and assessment tasks to engage students in the learning process.

This study did not differentiate between part-time and full-time students. Therefore, many part-time students may have been included in this study. This study also did not differentiate between students registered primarily at FVSU or at another institution. Therefore, many students included in this study may have used FVSU as an auxiliary institution to complete their environmental science class requirement.

Test Instruments

In this study, student performance was operationalized by final course grades. The final course grade was derived from test, homework, class participation, and research project scores. The four aforementioned assessments were valid and relevant; they were useful in gauging student ability and generating objective performance measurements. The final grades were converted from numerical scores to traditional GPA letters.

Data Collection Procedures

The sample 548 student grades were obtained from FVSU's Office of Institutional Research Planning and Effectiveness (OIRPE). The OIRPE released the grades to the instructor with the expectation the instructor would maintain confidentiality and not disclose said information to third parties. After the data was obtained, the instructor analyzed and processed the data though SPSS software to calculate specific values. These converted values were subsequently used to draw conclusions and validate the hypothesis.

Summary of the Results: The chi-square analysis showed no significant difference in student performance between online and face-to-face (F2F) learners [χ 2 (4, N = 548) = 6.531, p > 0.05]. The independent sample t -test showed no significant difference in student performance between online and F2F learners with respect to gender [ t (145) = 1.42, p = 0.122]. The 2-way ANOVA showed no significant difference in student performance between online and F2F learners with respect to class rank ( Girard et al., 2016 ).

Research question #1 was to determine if there was a statistically significant difference between the academic performance of online and F2F students.

Research Question 1

The first research question investigated if there was a difference in student performance between F2F and online learners.

To investigate the first research question, we used a traditional chi-square method to analyze the data. The chi-square analysis is particularly useful for this type of comparison because it allows us to determine if the relationship between teaching modality and performance in our sample set can be extended to the larger population. The chi-square method provides us with a numerical result which can be used to determine if there is a statistically significant difference between the two groups.

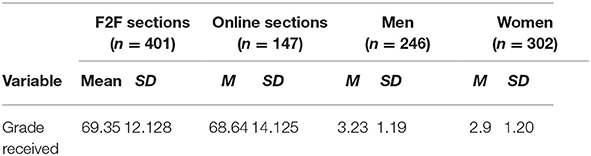

Table 1 shows us the mean and SD for modality and for gender. It is a general breakdown of numbers to visually elucidate any differences between scores and deviations. The mean GPA for both modalities is similar with F2F learners scoring a 69.35 and online learners scoring a 68.64. Both groups had fairly similar SDs. A stronger difference can be seen between the GPAs earned by men and women. Men had a 3.23 mean GPA while women had a 2.9 mean GPA. The SDs for both groups were almost identical. Even though the 0.33 numerical difference may look fairly insignificant, it must be noted that a 3.23 is approximately a B+ while a 2.9 is approximately a B. Given a categorical range of only A to F, a plus differential can be considered significant.

Table 1 . Means and standard deviations for 8 semester- “Environmental Science data set.”

The mean grade for men in the environmental online classes ( M = 3.23, N = 246, SD = 1.19) was higher than the mean grade for women in the classes ( M = 2.9, N = 302, SD = 1.20) (see Table 1 ).

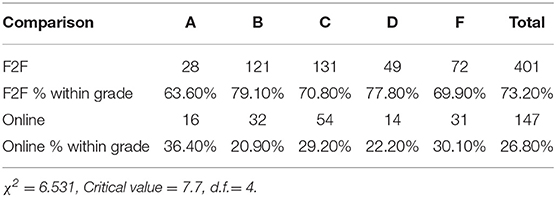

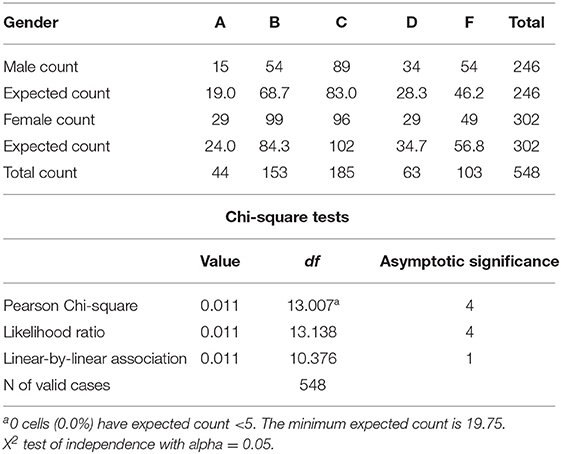

First, a chi-square analysis was performed using SPSS to determine if there was a statistically significant difference in grade distribution between online and F2F students. Students enrolled in the F2F class had the highest percentage of A's (63.60%) as compared to online students (36.40%). Table 2 displays grade distribution by course delivery modality. The difference in student performance was statistically significant, χ 2 (4, N = 548) = 6.531, p > 0.05. Table 3 shows the gender difference on student performance between online and F2F students.

Table 2 . Contingency table for student's academic performance ( N = 548).

Table 3 . Gender * performance crosstabulation.

Table 2 shows us the performance measures of online and F2F students by grade category. As can be seen, F2F students generated the highest performance numbers for each grade category. However, this disparity was mostly due to a higher number of F2F students in the study. There were 401 F2F students as opposed to just 147 online students. When viewing grades with respect to modality, there are smaller percentage differences between respective learners ( Tanyel and Griffin, 2014 ). For example, F2F learners earned 28 As (63.60% of total A's earned) while online learners earned 16 As (36.40% of total A's earned). However, when viewing the A grade with respect to total learners in each modality, it can be seen that 28 of the 401 F2F students (6.9%) earned As as compared to 16 of 147 (10.9%) online learners. In this case, online learners scored relatively higher in this grade category. The latter measure (grade total as a percent of modality total) is a better reflection of respective performance levels.

Given a critical value of 7.7 and a d.f. of 4, we were able to generate a chi-squared measure of 6.531. The correlating p -value of 0.163 was greater than our p -value significance level of 0.05. We, therefore, had to accept the null hypothesis and reject the alternative hypothesis. There is no statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of performance scores.

Research Question 2

The second research question was posed to evaluate if there was a difference between online and F2F varied with gender. Does online and F2F student performance vary with respect to gender? Table 3 shows the gender difference on student performance between online and face to face students. We used chi-square test to determine if there were differences in online and F2F student performance with respect to gender. The chi-square test with alpha equal to 0.05 as criterion for significance. The chi-square result shows that there is no statistically significant difference between men and women in terms of performance.

Research Question 3

The third research question tried to determine if there was a difference between online and F2F varied with respect to class rank. Does online and F2F student performance vary with respect to class rank?

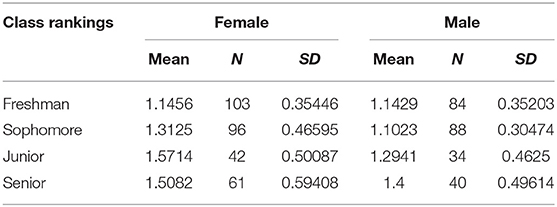

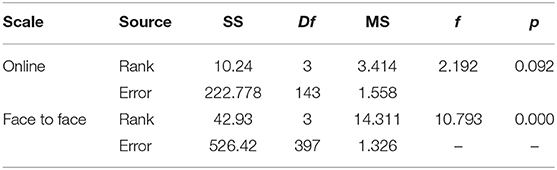

Table 4 shows the mean scores and standard deviations of freshman, sophomore, and junior and senior students for both online and F2F student performance. To test the third hypothesis, we used a two-way ANOVA. The ANOVA is a useful appraisal tool for this particular hypothesis as it tests the differences between multiple means. Instead of testing specific differences, the ANOVA generates a much broader picture of average differences. As can be seen in Table 4 , the ANOVA test for this particular hypothesis states there is no significant difference between online and F2F learners with respect to class rank. Therefore, we must accept the null hypothesis and reject the alternative hypothesis.

Table 4 . Descriptive analysis of student performance by class rankings gender.

The results of the ANOVA show there is no significant difference in performance between online and F2F students with respect to class rank. Results of ANOVA is presented in Table 5 .

Table 5 . Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for online and F2F of class rankings.

As can be seen in Table 4 , the ANOVA test for this particular hypothesis states there is no significant difference between online and F2F learners with respect to class rank. Therefore, we must accept the null hypothesis and reject the alternative hypothesis.

Discussion and Social Implications

The results of the study show there is no significant difference in performance between online and traditional classroom students with respect to modality, gender, or class rank in a science concepts course for non-STEM majors. Although there were sample size issues and study limitations, this assessment shows both online learners and classroom learners perform at the same level. This conclusion indicates teaching modality may not matter as much as other factors. Given the relatively sparse data on pedagogical modality comparison given specific student population characteristics, this study could be considered innovative. In the current literature, we have not found a study of this nature comparing online and F2F non-STEM majors with respect to three separate factors—medium, gender, and class rank—and the ability to learn science concepts and achieve learning outcomes. Previous studies have compared traditional classroom learning vs. F2F learning for other factors (including specific courses, costs, qualitative analysis, etcetera, but rarely regarding outcomes relevant to population characteristics of learning for a specific science concepts course over many years) ( Liu, 2005 ).

In a study evaluating the transformation of a graduate level course for teachers, academic quality of the online course and learning outcomes were evaluated. The study evaluated the ability of course instructors to design the course for online delivery and develop various interactive multimedia models at a cost-savings to the respective university. The online learning platform proved effective in translating information where tested students successfully achieved learning outcomes comparable to students taking the F2F course ( Herman and Banister, 2007 ).

Another study evaluated the similarities and differences in F2F and online learning in a non-STEM course, “Foundations of American Education” and overall course satisfaction by students enrolled in either of the two modalities. F2F and online course satisfaction was qualitatively and quantitative analyzed. However, in analyzing online and F2F course feedback using quantitative feedback, online course satisfaction was less than F2F satisfaction. When qualitative data was used, course satisfaction was similar between modalities ( Werhner, 2010 ). The course satisfaction data and feedback was used to suggest a number of posits for effective online learning in the specific course. The researcher concluded that there was no difference in the learning success of students enrolled in the online vs. F2F course, stating that “in terms of learning, students who apply themselves diligently should be successful in either format” ( Dell et al., 2010 ). The author's conclusion presumes that the “issues surrounding class size are under control and that the instructor has a course load that makes the intensity of the online course workload feasible” where the authors conclude that the workload for online courses is more than for F2F courses ( Stern, 2004 ).

In “A Meta-Analysis of Three Types of Interaction Treatments in Distance Education,” Bernard et al. (2009) conducted a meta-analysis evaluating three types of instructional and/or media conditions designed into distance education (DE) courses known as interaction treatments (ITs)—student–student (SS), student–teacher (ST), or student–content (SC) interactions—to other DE instructional/interaction treatments. The researchers found that a strong association existed between the integration of these ITs into distance education courses and achievement compared with blended or F2F modalities of learning. The authors speculated that this was due to increased cognitive engagement based in these three interaction treatments ( Larson and Sung, 2009 ).

Other studies evaluating students' preferences (but not efficacy) for online vs. F2F learning found that students prefer online learning when it was offered, depending on course topic, and online course technology platform ( Ary and Brune, 2011 ). F2F learning was preferred when courses were offered late morning or early afternoon 2–3 days/week. A significant preference for online learning resulted across all undergraduate course topics (American history and government, humanities, natural sciences, social, and behavioral sciences, diversity, and international dimension) except English composition and oral communication. A preference for analytical and quantitative thought courses was also expressed by students, though not with statistically significant results ( Mann and Henneberry, 2014 ). In this research study, we looked at three hypothesis comparing online and F2F learning. In each case, the null hypothesis was accepted. Therefore, at no level of examination did we find a significant difference between online and F2F learners. This finding is important because it tells us traditional-style teaching with its heavy emphasis on interpersonal classroom dynamics may 1 day be replaced by online instruction. According to Daymont and Blau (2008) online learners, regardless of gender or class rank, learn as much from electronic interaction as they do from personal interaction. Kemp and Grieve (2014) also found that both online and F2F learning for psychology students led to similar academic performance. Given the cost efficiencies and flexibility of online education, Web-based instructional systems may rapidly rise.

A number of studies support the economic benefits of online vs. F2F learning, despite differences in social constructs and educational support provided by governments. In a study by Li and Chen (2012) higher education institutions benefit the most from two of four outputs—research outputs and distance education—with teaching via distance education at both the undergraduate and graduate levels more profitable than F2F teaching at higher education institutions in China. Zhang and Worthington (2017) reported an increasing cost benefit for the use of distance education over F2F instruction as seen at 37 Australian public universities over 9 years from 2003 to 2012. Maloney et al. (2015) and Kemp and Grieve (2014) also found significant savings in higher education when using online learning platforms vs. F2F learning. In the West, the cost efficiency of online learning has been demonstrated by several research studies ( Craig, 2015 ). Studies by Agasisti and Johnes (2015) and Bartley and Golek (2004) both found the cost benefits of online learning significantly greater than that of F2F learning at U.S. institutions.

Knowing there is no significant difference in student performance between the two mediums, institutions of higher education may make the gradual shift away from traditional instruction; they may implement Web-based teaching to capture a larger worldwide audience. If administered correctly, this shift to Web-based teaching could lead to a larger buyer population, more cost efficiencies, and more university revenue.

The social implications of this study should be touted; however, several concerns regarding generalizability need to be taken into account. First, this study focused solely on students from an environmental studies class for non-STEM majors. The ability to effectively prepare students for scientific professions without hands-on experimentation has been contended. As a course that functions to communicate scientific concepts, but does not require a laboratory based component, these results may not translate into similar performance of students in an online STEM course for STEM majors or an online course that has an online laboratory based co-requisite when compared to students taking traditional STEM courses for STEM majors. There are few studies that suggest the landscape may be changing with the ability to effectively train students in STEM core concepts via online learning. Biel and Brame (2016) reported successfully translating the academic success of F2F undergraduate biology courses to online biology courses. However, researchers reported that of the large-scale courses analyzed, two F2F sections outperformed students in online sections, and three found no significant difference. A study by Beale et al. (2014) comparing F2F learning with hybrid learning in an embryology course found no difference in overall student performance. Additionally, the bottom quartile of students showed no differential effect of the delivery method on examination scores. Further, a study from Lorenzo-Alvarez et al. (2019) found that radiology education in an online learning platform resulted in similar academic outcomes as F2F learning. Larger scale research is needed to determine the effectiveness of STEM online learning and outcomes assessments, including workforce development results.

In our research study, it is possible the study participants may have been more knowledgeable about environmental science than about other subjects. Therefore, it should be noted this study focused solely on students taking this one particular class. Given the results, this course presents a unique potential for increasing the number of non-STEM majors engaged in citizen science using the flexibility of online learning to teach environmental science core concepts.

Second, the operationalization measure of “grade” or “score” to determine performance level may be lacking in scope and depth. The grades received in a class may not necessarily show actual ability, especially if the weights were adjusted to heavily favor group tasks and writing projects. Other performance indicators may be better suited to properly access student performance. A single exam containing both multiple choice and essay questions may be a better operationalization indicator of student performance. This type of indicator will provide both a quantitative and qualitative measure of subject matter comprehension.

Third, the nature of the student sample must be further dissected. It is possible the online students in this study may have had more time than their counterparts to learn the material and generate better grades ( Summers et al., 2005 ). The inverse holds true, as well. Because this was a convenience non-probability sampling, the chances of actually getting a fair cross section of the student population were limited. In future studies, greater emphasis must be placed on selecting proper study participants, those who truly reflect proportions, types, and skill levels.

This study was relevant because it addressed an important educational topic; it compared two student groups on multiple levels using a single operationalized performance measure. More studies, however, of this nature need to be conducted before truly positing that online and F2F teaching generate the same results. Future studies need to eliminate spurious causal relationships and increase generalizability. This will maximize the chances of generating a definitive, untainted results. This scientific inquiry and comparison into online and traditional teaching will undoubtedly garner more attention in the coming years.

Our study compared learning via F2F vs. online learning modalities in teaching an environmental science course additionally evaluating factors of gender and class rank. These data demonstrate the ability to similarly translate environmental science concepts for non-STEM majors in both traditional and online platforms irrespective of gender or class rank. The social implications of this finding are important for advancing access to and learning of scientific concepts by the general population, as many institutions of higher education allow an online course to be taken without enrolling in a degree program. Thus, the potential exists for increasing the number of non-STEM majors engaged in citizen science using the flexibility of online learning to teach environmental science core concepts.

Limitations of the Study

The limitations of the study centered around the nature of the sample group, student skills/abilities, and student familiarity with online instruction. First, because this was a convenience, non-probability sample, the independent variables were not adjusted for real-world accuracy. Second, student intelligence and skill level were not taken into consideration when separating out comparison groups. There exists the possibility that the F2F learners in this study may have been more capable than the online students and vice versa. This limitation also applies to gender and class rank differences ( Friday et al., 2006 ). Finally, there may have been ease of familiarity issues between the two sets of learners. Experienced traditional classroom students now taking Web-based courses may be daunted by the technical aspect of the modality. They may not have had the necessary preparation or experience to efficiently e-learn, thus leading to lowered scores ( Helms, 2014 ). In addition to comparing online and F2F instructional efficacy, future research should also analyze blended teaching methods for the effectiveness of courses for non-STEM majors to impart basic STEM concepts and see if the blended style is more effective than any one pure style.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Fort Valley State University Human Subjects Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

JP provided substantial contributions to the conception of the work, acquisition and analysis of data for the work, and is the corresponding author on this paper who agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. FJ provided substantial contributions to the design of the work, interpretation of the data for the work, and revised it critically for intellectual content.

This research was supported in part by funding from the National Science Foundation, Awards #1649717, 1842510, Ñ900572, and 1939739 to FJ.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their detailed comments and feedback that assisted in the revising of our original manuscript.

Agasisti, T., and Johnes, G. (2015). Efficiency, costs, rankings and heterogeneity: the case of US higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 40, 60–82. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2013.818644

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ary, E. J., and Brune, C. W. (2011). A comparison of student learning outcomes in traditional and online personal finance courses. MERLOT J. Online Learn. Teach. 7, 465–474.

Google Scholar

Atchley, W., Wingenbach, G., and Akers, C. (2013). Comparison of course completion and student performance through online and traditional courses. Int. Rev. Res. Open Dist. Learn. 14, 104–116. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v14i4.1461

Bartley, S. J., and Golek, J. H. (2004). Evaluating the cost effectiveness of online and face-to-face instruction. Educ. Technol. Soc. 7, 167–175.

Beale, E. G., Tarwater, P. M., and Lee, V. H. (2014). A retrospective look at replacing face-to-face embryology instruction with online lectures in a human anatomy course. Am. Assoc. Anat. 7, 234–241. doi: 10.1002/ase.1396

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bernard, R. M., Abrami, P. C., Borokhovski, E., Wade, C. A., Tamim, R. M., Surkesh, M. A., et al. (2009). A meta-analysis of three types of interaction treatments in distance education. Rev. Educ. Res. 79, 1243–1289. doi: 10.3102/0034654309333844

Biel, R., and Brame, C. J. (2016). Traditional versus online biology courses: connecting course design and student learning in an online setting. J. Microbiol. Biol. Educ. 17, 417–422. doi: 10.1128/jmbe.v17i3.1157

Bigelow, C. A. (2009). Comparing student performance in an online versus a face to face introductory turfgrass science course-a case study. NACTA J. 53, 1–7.

Columbaro, N. L., and Monaghan, C. H. (2009). Employer perceptions of online degrees: a literature review. Online J. Dist. Learn. Administr. 12.

Craig, R. (2015). A Brief History (and Future) of Online Degrees. Forbes/Education . Available online at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/ryancraig/2015/06/23/a-brief-history-and-future-of-online-degrees/#e41a4448d9a8

Daymont, T., and Blau, G. (2008). Student performance in online and traditional sections of an undergraduate management course. J. Behav. Appl. Manag. 9, 275–294.

Dell, C. A., Low, C., and Wilker, J. F. (2010). Comparing student achievement in online and face-to-face class formats. J. Online Learn. Teach. Long Beach 6, 30–42.

Driscoll, A., Jicha, K., Hunt, A. N., Tichavsky, L., and Thompson, G. (2012). Can online courses deliver in-class results? A comparison of student performance and satisfaction in an online versus a face-to-face introductory sociology course. Am. Sociol. Assoc . 40, 312–313. doi: 10.1177/0092055X12446624

Friday, E., Shawnta, S., Green, A. L., and Hill, A. Y. (2006). A multi-semester comparison of student performance between multiple traditional and online sections of two management courses. J. Behav. Appl. Manag. 8, 66–81.

Girard, J. P., Yerby, J., and Floyd, K. (2016). Knowledge retention in capstone experiences: an analysis of online and face-to-face courses. Knowl. Manag. ELearn. 8, 528–539. doi: 10.34105/j.kmel.2016.08.033

Helms, J. L. (2014). Comparing student performance in online and face-to-face delivery modalities. J. Asynchr. Learn. Netw. 18, 1–14. doi: 10.24059/olj.v18i1.348

Herman, T., and Banister, S. (2007). Face-to-face versus online coursework: a comparison of costs and learning outcomes. Contemp. Issues Technol. Teach. Educ. 7, 318–326.

Kemp, N., and Grieve, R. (2014). Face-to-Face or face-to-screen? Undergraduates' opinions and test performance in classroom vs. online learning. Front. Psychol. 5:1278. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01278

Keramidas, C. G. (2012). Are undergraduate students ready for online learning? A comparison of online and face-to-face sections of a course. Rural Special Educ. Q . 31, 25–39. doi: 10.1177/875687051203100405

Larson, D.K., and Sung, C. (2009). Comparing student performance: online versus blended versus face-to-face. J. Asynchr. Learn. Netw. 13, 31–42. doi: 10.24059/olj.v13i1.1675

Li, F., and Chen, X. (2012). Economies of scope in distance education: the case of Chinese Research Universities. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 13, 117–131.

Liu, Y. (2005). Effects of online instruction vs. traditional instruction on student's learning. Int. J. Instruct. Technol. Dist. Learn. 2, 57–64.

Lorenzo-Alvarez, R., Rudolphi-Solero, T., Ruiz-Gomez, M. J., and Sendra-Portero, F. (2019). Medical student education for abdominal radiographs in a 3D virtual classroom versus traditional classroom: a randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Roentgenol. 213, 644–650. doi: 10.2214/AJR.19.21131

Lundberg, J., Castillo-Merino, D., and Dahmani, M. (2008). Do online students perform better than face-to-face students? Reflections and a short review of some Empirical Findings. Rev. Univ. Soc. Conocim . 5, 35–44. doi: 10.7238/rusc.v5i1.326

Maloney, S., Nicklen, P., Rivers, G., Foo, J., Ooi, Y. Y., Reeves, S., et al. (2015). Cost-effectiveness analysis of blended versus face-to-face delivery of evidence-based medicine to medical students. J. Med. Internet Res. 17:e182. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4346

Mann, J. T., and Henneberry, S. R. (2014). Online versus face-to-face: students' preferences for college course attributes. J. Agric. Appl. Econ . 46, 1–19. doi: 10.1017/S1074070800000602

Mozes-Carmel, A., and Gold, S. S. (2009). A comparison of online vs proctored final exams in online classes. Imanagers J. Educ. Technol. 6, 76–81. doi: 10.26634/jet.6.1.212

Richardson, J. C., and Swan, K. (2003). Examining social presence in online courses in relation to student's perceived learning and satisfaction. J. Asynchr. Learn. 7, 68–88.

Roval, A. P., and Jordan, H. M. (2004). Blended learning and sense of community: a comparative analysis with traditional and fully online graduate courses. Int. Rev. Res. Open Dist. Learn. 5. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v5i2.192

Salcedo, C. S. (2010). Comparative analysis of learning outcomes in face-to-face foreign language classes vs. language lab and online. J. Coll. Teach. Learn. 7, 43–54. doi: 10.19030/tlc.v7i2.88

Stern, B. S. (2004). A comparison of online and face-to-face instruction in an undergraduate foundations of american education course. Contemp. Issues Technol. Teach. Educ. J. 4, 196–213.

Summers, J. J., Waigandt, A., and Whittaker, T. A. (2005). A comparison of student achievement and satisfaction in an online versus a traditional face-to-face statistics class. Innov. High. Educ. 29, 233–250. doi: 10.1007/s10755-005-1938-x

Tanyel, F., and Griffin, J. (2014). A Ten-Year Comparison of Outcomes and Persistence Rates in Online versus Face-to-Face Courses . Retrieved from: https://www.westga.edu/~bquest/2014/onlinecourses2014.pdf

Werhner, M. J. (2010). A comparison of the performance of online versus traditional on-campus earth science students on identical exams. J. Geosci. Educ. 58, 310–312. doi: 10.5408/1.3559697

Westhuis, D., Ouellette, P. M., and Pfahler, C. L. (2006). A comparative analysis of on-line and classroom-based instructional formats for teaching social work research. Adv. Soc. Work 7, 74–88. doi: 10.18060/184

Wladis, C., Conway, K. M., and Hachey, A. C. (2015). The online STEM classroom-who succeeds? An exploration of the impact of ethnicity, gender, and non-traditional student characteristics in the community college context. Commun. Coll. Rev. 43, 142–164. doi: 10.1177/0091552115571729

Xu, D., and Jaggars, S. S. (2016). Performance gaps between online and face-to-face courses: differences across types of students and academic subject areas. J. Higher Educ. 85, 633–659. doi: 10.1353/jhe.2014.0028

Zhang, L.-C., and Worthington, A. C. (2017). Scale and scope economies of distance education in Australian universities. Stud. High. Educ. 42, 1785–1799. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2015.1126817

Keywords: face-to-face (F2F), traditional classroom teaching, web-based instructions, information and communication technology (ICT), online learning, desire to learn (D2L), passive learning, active learning

Citation: Paul J and Jefferson F (2019) A Comparative Analysis of Student Performance in an Online vs. Face-to-Face Environmental Science Course From 2009 to 2016. Front. Comput. Sci. 1:7. doi: 10.3389/fcomp.2019.00007

Received: 15 May 2019; Accepted: 15 October 2019; Published: 12 November 2019.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2019 Paul and Jefferson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jasmine Paul, paulj@fvsu.edu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

A systematic review of research on online teaching and learning from 2009 to 2018

Associated data.

Systematic reviews were conducted in the nineties and early 2000's on online learning research. However, there is no review examining the broader aspect of research themes in online learning in the last decade. This systematic review addresses this gap by examining 619 research articles on online learning published in twelve journals in the last decade. These studies were examined for publication trends and patterns, research themes, research methods, and research settings and compared with the research themes from the previous decades. While there has been a slight decrease in the number of studies on online learning in 2015 and 2016, it has then continued to increase in 2017 and 2018. The majority of the studies were quantitative in nature and were examined in higher education. Online learning research was categorized into twelve themes and a framework across learner, course and instructor, and organizational levels was developed. Online learner characteristics and online engagement were examined in a high number of studies and were consistent with three of the prior systematic reviews. However, there is still a need for more research on organization level topics such as leadership, policy, and management and access, culture, equity, inclusion, and ethics and also on online instructor characteristics.

- • Twelve online learning research themes were identified in 2009–2018.

- • A framework with learner, course and instructor, and organizational levels was used.

- • Online learner characteristics and engagement were the mostly examined themes.

- • The majority of the studies used quantitative research methods and in higher education.

- • There is a need for more research on organization level topics.

1. Introduction

Online learning has been on the increase in the last two decades. In the United States, though higher education enrollment has declined, online learning enrollment in public institutions has continued to increase ( Allen & Seaman, 2017 ), and so has the research on online learning. There have been review studies conducted on specific areas on online learning such as innovations in online learning strategies ( Davis et al., 2018 ), empirical MOOC literature ( Liyanagunawardena et al., 2013 ; Veletsianos & Shepherdson, 2016 ; Zhu et al., 2018 ), quality in online education ( Esfijani, 2018 ), accessibility in online higher education ( Lee, 2017 ), synchronous online learning ( Martin et al., 2017 ), K-12 preparation for online teaching ( Moore-Adams et al., 2016 ), polychronicity in online learning ( Capdeferro et al., 2014 ), meaningful learning research in elearning and online learning environments ( Tsai, Shen, & Chiang, 2013 ), problem-based learning in elearning and online learning environments ( Tsai & Chiang, 2013 ), asynchronous online discussions ( Thomas, 2013 ), self-regulated learning in online learning environments ( Tsai, Shen, & Fan, 2013 ), game-based learning in online learning environments ( Tsai & Fan, 2013 ), and online course dropout ( Lee & Choi, 2011 ). While there have been review studies conducted on specific online learning topics, very few studies have been conducted on the broader aspect of online learning examining research themes.

2. Systematic Reviews of Distance Education and Online Learning Research

Distance education has evolved from offline to online settings with the access to internet and COVID-19 has made online learning the common delivery method across the world. Tallent-Runnels et al. (2006) reviewed research late 1990's to early 2000's, Berge and Mrozowski (2001) reviewed research 1990 to 1999, and Zawacki-Richter et al. (2009) reviewed research in 2000–2008 on distance education and online learning. Table 1 shows the research themes from previous systematic reviews on online learning research. There are some themes that re-occur in the various reviews, and there are also new themes that emerge. Though there have been reviews conducted in the nineties and early 2000's, there is no review examining the broader aspect of research themes in online learning in the last decade. Hence, the need for this systematic review which informs the research themes in online learning from 2009 to 2018. In the following sections, we review these systematic review studies in detail.

Comparison of online learning research themes from previous studies.

| 1990–1999 ( ) | 1993–2004 ( ) | 2000–2008 (Zawacki-Richter et al., 2009) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Most Number of Studies | |||

| Lowest Number of Studies |

2.1. Distance education research themes, 1990 to 1999 ( Berge & Mrozowski, 2001 )

Berge and Mrozowski (2001) reviewed 890 research articles and dissertation abstracts on distance education from 1990 to 1999. The four distance education journals chosen by the authors to represent distance education included, American Journal of Distance Education, Distance Education, Open Learning, and the Journal of Distance Education. This review overlapped in the dates of the Tallent-Runnels et al. (2006) study. Berge and Mrozowski (2001) categorized the articles according to Sherry's (1996) ten themes of research issues in distance education: redefining roles of instructor and students, technologies used, issues of design, strategies to stimulate learning, learner characteristics and support, issues related to operating and policies and administration, access and equity, and costs and benefits.

In the Berge and Mrozowski (2001) study, more than 100 studies focused on each of the three themes: (1) design issues, (2) learner characteristics, and (3) strategies to increase interactivity and active learning. By design issues, the authors focused on instructional systems design and focused on topics such as content requirement, technical constraints, interactivity, and feedback. The next theme, strategies to increase interactivity and active learning, were closely related to design issues and focused on students’ modes of learning. Learner characteristics focused on accommodating various learning styles through customized instructional theory. Less than 50 studies focused on the three least examined themes: (1) cost-benefit tradeoffs, (2) equity and accessibility, and (3) learner support. Cost-benefit trade-offs focused on the implementation costs of distance education based on school characteristics. Equity and accessibility focused on the equity of access to distance education systems. Learner support included topics such as teacher to teacher support as well as teacher to student support.

2.2. Online learning research themes, 1993 to 2004 ( Tallent-Runnels et al., 2006 )

Tallent-Runnels et al. (2006) reviewed research on online instruction from 1993 to 2004. They reviewed 76 articles focused on online learning by searching five databases, ERIC, PsycINFO, ContentFirst, Education Abstracts, and WilsonSelect. Tallent-Runnels et al. (2006) categorized research into four themes, (1) course environment, (2) learners' outcomes, (3) learners’ characteristics, and (4) institutional and administrative factors. The first theme that the authors describe as course environment ( n = 41, 53.9%) is an overarching theme that includes classroom culture, structural assistance, success factors, online interaction, and evaluation.

Tallent-Runnels et al. (2006) for their second theme found that studies focused on questions involving the process of teaching and learning and methods to explore cognitive and affective learner outcomes ( n = 29, 38.2%). The authors stated that they found the research designs flawed and lacked rigor. However, the literature comparing traditional and online classrooms found both delivery systems to be adequate. Another research theme focused on learners’ characteristics ( n = 12, 15.8%) and the synergy of learners, design of the online course, and system of delivery. Research findings revealed that online learners were mainly non-traditional, Caucasian, had different learning styles, and were highly motivated to learn. The final theme that they reported was institutional and administrative factors (n = 13, 17.1%) on online learning. Their findings revealed that there was a lack of scholarly research in this area and most institutions did not have formal policies in place for course development as well as faculty and student support in training and evaluation. Their research confirmed that when universities offered online courses, it improved student enrollment numbers.

2.3. Distance education research themes 2000 to 2008 ( Zawacki-Richter et al., 2009 )

Zawacki-Richter et al. (2009) reviewed 695 articles on distance education from 2000 to 2008 using the Delphi method for consensus in identifying areas and classified the literature from five prominent journals. The five journals selected due to their wide scope in research in distance education included Open Learning, Distance Education, American Journal of Distance Education, the Journal of Distance Education, and the International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning. The reviewers examined the main focus of research and identified gaps in distance education research in this review.

Zawacki-Richter et al. (2009) classified the studies into macro, meso and micro levels focusing on 15 areas of research. The five areas of the macro-level addressed: (1) access, equity and ethics to deliver distance education for developing nations and the role of various technologies to narrow the digital divide, (2) teaching and learning drivers, markets, and professional development in the global context, (3) distance delivery systems and institutional partnerships and programs and impact of hybrid modes of delivery, (4) theoretical frameworks and models for instruction, knowledge building, and learner interactions in distance education practice, and (5) the types of preferred research methodologies. The meso-level focused on seven areas that involve: (1) management and organization for sustaining distance education programs, (2) examining financial aspects of developing and implementing online programs, (3) the challenges and benefits of new technologies for teaching and learning, (4) incentives to innovate, (5) professional development and support for faculty, (6) learner support services, and (7) issues involving quality standards and the impact on student enrollment and retention. The micro-level focused on three areas: (1) instructional design and pedagogical approaches, (2) culturally appropriate materials, interaction, communication, and collaboration among a community of learners, and (3) focus on characteristics of adult learners, socio-economic backgrounds, learning preferences, and dispositions.

The top three research themes in this review by Zawacki-Richter et al. (2009) were interaction and communities of learning ( n = 122, 17.6%), instructional design ( n = 121, 17.4%) and learner characteristics ( n = 113, 16.3%). The lowest number of studies (less than 3%) were found in studies examining the following research themes, management and organization ( n = 18), research methods in DE and knowledge transfer ( n = 13), globalization of education and cross-cultural aspects ( n = 13), innovation and change ( n = 13), and costs and benefits ( n = 12).

2.4. Online learning research themes

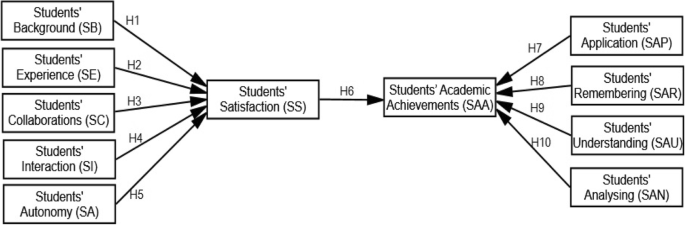

These three systematic reviews provide a broad understanding of distance education and online learning research themes from 1990 to 2008. However, there is an increase in the number of research studies on online learning in this decade and there is a need to identify recent research themes examined. Based on the previous systematic reviews ( Berge & Mrozowski, 2001 ; Hung, 2012 ; Tallent-Runnels et al., 2006 ; Zawacki-Richter et al., 2009 ), online learning research in this study is grouped into twelve different research themes which include Learner characteristics, Instructor characteristics, Course or program design and development, Course Facilitation, Engagement, Course Assessment, Course Technologies, Access, Culture, Equity, Inclusion, and Ethics, Leadership, Policy and Management, Instructor and Learner Support, and Learner Outcomes. Table 2 below describes each of the research themes and using these themes, a framework is derived in Fig. 1 .

Research themes in online learning.

| Research Theme | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Learner Characteristics | Focuses on understanding the learner characteristics and how online learning can be designed and delivered to meet their needs. Online learner characteristics can be broadly categorized into demographic characteristics, academic characteristics, cognitive characteristics, affective, self-regulation, and motivational characteristics. |

| 2 | Learner Outcomes | Learner outcomes are statements that specify what the learner will achieve at the end of the course or program. Examining learner outcomes such as success, retention, and dropouts are critical in online courses. |

| 3 | Engagement | Engaging the learner in the online course is vitally important as they are separated from the instructor and peers in the online setting. Engagement is examined through the lens of interaction, participation, community, collaboration, communication, involvement and presence. |

| 4 | Course or Program Design and Development | Course design and development is critical in online learning as it engages and assists the students in achieving the learner outcomes. Several models and processes are used to develop the online course, employing different design elements to meet student needs. |

| 5 | Course Facilitation | The delivery or facilitation of the course is as important as course design. Facilitation strategies used in delivery of the course such as in communication and modeling practices are examined in course facilitation. |

| 6 | Course Assessment | Course Assessments are adapted and delivered in an online setting. Formative assessments, peer assessments, differentiated assessments, learner choice in assessments, feedback system, online proctoring, plagiarism in online learning, and alternate assessments such as eportfolios are examined. |

| 7 | Evaluation and Quality Assurance | Evaluation is making a judgment either on the process, the product or a program either during or at the end. There is a need for research on evaluation and quality in the online courses. This has been examined through course evaluations, surveys, analytics, social networks, and pedagogical assessments. Quality assessment rubrics such as Quality Matters have also been researched. |

| 8 | Course Technologies | A number of online course technologies such as learning management systems, online textbooks, online audio and video tools, collaborative tools, social networks to build online community have been the focus of research. |

| 9 | Instructor Characteristics | With the increase in online courses, there has also been an increase in the number of instructors teaching online courses. Instructor characteristics can be examined through their experience, satisfaction, and roles in online teaching. |

| 10 | Institutional Support | The support for online learning is examined both as learner support and instructor support. Online students need support to be successful online learners and this could include social, academic, and cognitive forms of support. Online instructors need support in terms of pedagogy and technology to be successful online instructors. |

| 11 | Access, Culture, Equity, Inclusion, and Ethics | Cross-cultural online learning is gaining importance along with access in global settings. In addition, providing inclusive opportunities for all learners and in ethical ways is being examined. |

| 12 | Leadership, Policy and Management | Leadership support is essential for success of online learning. Leaders perspectives, challenges and strategies used are examined. Policies and governance related research are also being studied. |

Online learning research themes framework.

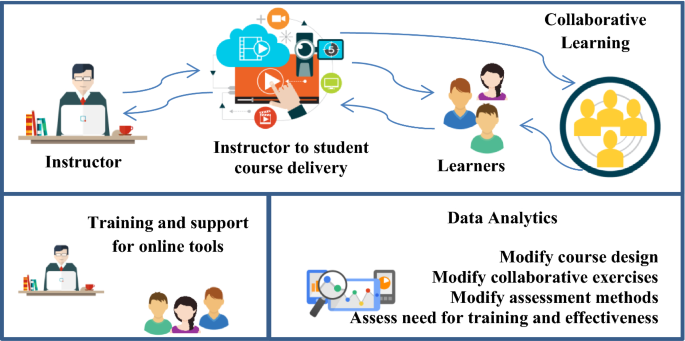

The collection of research themes is presented as a framework in Fig. 1 . The themes are organized by domain or level to underscore the nested relationship that exists. As evidenced by the assortment of themes, research can focus on any domain of delivery or associated context. The “Learner” domain captures characteristics and outcomes related to learners and their interaction within the courses. The “Course and Instructor” domain captures elements about the broader design of the course and facilitation by the instructor, and the “Organizational” domain acknowledges the contextual influences on the course. It is important to note as well that due to the nesting, research themes can cross domains. For example, the broader cultural context may be studied as it pertains to course design and development, and institutional support can include both learner support and instructor support. Likewise, engagement research can involve instructors as well as learners.

In this introduction section, we have reviewed three systematic reviews on online learning research ( Berge & Mrozowski, 2001 ; Tallent-Runnels et al., 2006 ; Zawacki-Richter et al., 2009 ). Based on these reviews and other research, we have derived twelve themes to develop an online learning research framework which is nested in three levels: learner, course and instructor, and organization.

2.5. Purpose of this research

In two out of the three previous reviews, design, learner characteristics and interaction were examined in the highest number of studies. On the other hand, cost-benefit tradeoffs, equity and accessibility, institutional and administrative factors, and globalization and cross-cultural aspects were examined in the least number of studies. One explanation for this may be that it is a function of nesting, noting that studies falling in the Organizational and Course levels may encompass several courses or many more participants within courses. However, while some research themes re-occur, there are also variations in some themes across time, suggesting the importance of research themes rise and fall over time. Thus, a critical examination of the trends in themes is helpful for understanding where research is needed most. Also, since there is no recent study examining online learning research themes in the last decade, this study strives to address that gap by focusing on recent research themes found in the literature, and also reviewing research methods and settings. Notably, one goal is to also compare findings from this decade to the previous review studies. Overall, the purpose of this study is to examine publication trends in online learning research taking place during the last ten years and compare it with the previous themes identified in other review studies. Due to the continued growth of online learning research into new contexts and among new researchers, we also examine the research methods and settings found in the studies of this review.

The following research questions are addressed in this study.

- 1. What percentage of the population of articles published in the journals reviewed from 2009 to 2018 were related to online learning and empirical?

- 2. What is the frequency of online learning research themes in the empirical online learning articles of journals reviewed from 2009 to 2018?

- 3. What is the frequency of research methods and settings that researchers employed in the empirical online learning articles of the journals reviewed from 2009 to 2018?

This five-step systematic review process described in the U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, What Works Clearinghouse Procedures and Standards Handbook, Version 4.0 ( 2017 ) was used in this systematic review: (a) developing the review protocol, (b) identifying relevant literature, (c) screening studies, (d) reviewing articles, and (e) reporting findings.

3.1. Data sources and search strategies

The Education Research Complete database was searched using the keywords below for published articles between the years 2009 and 2018 using both the Title and Keyword function for the following search terms.

“online learning" OR "online teaching" OR "online program" OR "online course" OR “online education”

3.2. Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The initial search of online learning research among journals in the database resulted in more than 3000 possible articles. Therefore, we limited our search to select journals that focus on publishing peer-reviewed online learning and educational research. Our aim was to capture the journals that published the most articles in online learning. However, we also wanted to incorporate the concept of rigor, so we used expert perception to identify 12 peer-reviewed journals that publish high-quality online learning research. Dissertations and conference proceedings were excluded. To be included in this systematic review, each study had to meet the screening criteria as described in Table 3 . A research study was excluded if it did not meet all of the criteria to be included.

Inclusion/Exclusion criteria.

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Focus of the article | Online learning | Articles that did not focus on online learning |

| Journals Published | Twelve identified journals | Journals outside of the 12 journals |

| Publication date | 2009 to 2018 | Prior to 2009 and after 2018 |

| Publication type | Scholarly articles of original research from peer reviewed journals | Book chapters, technical reports, dissertations, or proceedings |

| Research Method and Results | There was an identifiable method and results section describing how the study was conducted and included the findings. Quantitative and qualitative methods were included. | Reviews of other articles, opinion, or discussion papers that do not include a discussion of the procedures of the study or analysis of data such as product reviews or conceptual articles. |

| Language | Journal article was written in English | Other languages were not included |

3.3. Process flow selection of articles

Fig. 2 shows the process flow involved in the selection of articles. The search in the database Education Research Complete yielded an initial sample of 3332 articles. Targeting the 12 journals removed 2579 articles. After reviewing the abstracts, we removed 134 articles based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria. The final sample, consisting of 619 articles, was entered into the computer software MAXQDA ( VERBI Software, 2019 ) for coding.

Flowchart of online learning research selection.

3.4. Developing review protocol

A review protocol was designed as a codebook in MAXQDA ( VERBI Software, 2019 ) by the three researchers. The codebook was developed based on findings from the previous review studies and from the initial screening of the articles in this review. The codebook included 12 research themes listed earlier in Table 2 (Learner characteristics, Instructor characteristics, Course or program design and development, Course Facilitation, Engagement, Course Assessment, Course Technologies, Access, Culture, Equity, Inclusion, and Ethics, Leadership, Policy and Management, Instructor and Learner Support, and Learner Outcomes), four research settings (higher education, continuing education, K-12, corporate/military), and three research designs (quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods). Fig. 3 below is a screenshot of MAXQDA used for the coding process.

Codebook from MAXQDA.

3.5. Data coding

Research articles were coded by two researchers in MAXQDA. Two researchers independently coded 10% of the articles and then discussed and updated the coding framework. The second author who was a doctoral student coded the remaining studies. The researchers met bi-weekly to address coding questions that emerged. After the first phase of coding, we found that more than 100 studies fell into each of the categories of Learner Characteristics or Engagement, so we decided to pursue a second phase of coding and reexamine the two themes. Learner Characteristics were classified into the subthemes of Academic, Affective, Motivational, Self-regulation, Cognitive, and Demographic Characteristics. Engagement was classified into the subthemes of Collaborating, Communication, Community, Involvement, Interaction, Participation, and Presence.

3.6. Data analysis

Frequency tables were generated for each of the variables so that outliers could be examined and narrative data could be collapsed into categories. Once cleaned and collapsed into a reasonable number of categories, descriptive statistics were used to describe each of the coded elements. We first present the frequencies of publications related to online learning in the 12 journals. The total number of articles for each journal (collectively, the population) was hand-counted from journal websites, excluding editorials and book reviews. The publication trend of online learning research was also depicted from 2009 to 2018. Then, the descriptive information of the 12 themes, including the subthemes of Learner Characteristics and Engagement were provided. Finally, research themes by research settings and methodology were elaborated.

4.1. Publication trends on online learning

Publication patterns of the 619 articles reviewed from the 12 journals are presented in Table 4 . International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning had the highest number of publications in this review. Overall, about 8% of the articles appearing in these twelve journals consisted of online learning publications; however, several journals had concentrations of online learning articles totaling more than 20%.

Empirical online learning research articles by journal, 2009–2018.

| Journal Name | Frequency of Empirical Online Learning Research | Percent of Sample | Percent of Journal's Total Articles |

|---|---|---|---|

| International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning | 152 | 24.40 | 22.55 |

| Internet & Higher Education | 84 | 13.48 | 26.58 |

| Computers & Education | 75 | 12.04 | 18.84 |

| Online Learning | 72 | 11.56 | 3.25 |

| Distance Education | 64 | 10.27 | 25.10 |

| Journal of Online Learning & Teaching | 39 | 6.26 | 11.71 |

| Journal of Educational Technology & Society | 36 | 5.78 | 3.63 |

| Quarterly Review of Distance Education | 24 | 3.85 | 4.71 |

| American Journal of Distance Education | 21 | 3.37 | 9.17 |

| British Journal of Educational Technology | 19 | 3.05 | 1.93 |

| Educational Technology Research & Development | 19 | 3.05 | 10.80 |

| Australasian Journal of Educational Technology | 14 | 2.25 | 2.31 |

| Total | 619 | 100.0 | 8.06 |

Note . Journal's Total Article count excludes reviews and editorials.

The publication trend of online learning research is depicted in Fig. 4 . When disaggregated by year, the total frequency of publications shows an increasing trend. Online learning articles increased throughout the decade and hit a relative maximum in 2014. The greatest number of online learning articles ( n = 86) occurred most recently, in 2018.

Online learning publication trends by year.

4.2. Online learning research themes that appeared in the selected articles

The publications were categorized into the twelve research themes identified in Fig. 1 . The frequency counts and percentages of the research themes are provided in Table 5 below. A majority of the research is categorized into the Learner domain. The fewest number of articles appears in the Organization domain.

Research themes in the online learning publications from 2009 to 2018.

| Research Themes | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Engagement | 179 | 28.92 |

| Learner Characteristics | 134 | 21.65 |

| Learner Outcome | 32 | 5.17 |

| Evaluation and Quality Assurance | 38 | 6.14 |

| Course Technologies | 35 | 5.65 |

| Course Facilitation | 34 | 5.49 |

| Course Assessment | 30 | 4.85 |

| Course Design and Development | 27 | 4.36 |

| Instructor Characteristics | 21 | 3.39 |

| Institutional Support | 33 | 5.33 |

| Access, Culture, Equity, Inclusion, and Ethics | 29 | 4.68 |

| Leadership, Policy, and Management | 27 | 4.36 |

The specific themes of Engagement ( n = 179, 28.92%) and Learner Characteristics ( n = 134, 21.65%) were most often examined in publications. These two themes were further coded to identify sub-themes, which are described in the next two sections. Publications focusing on Instructor Characteristics ( n = 21, 3.39%) were least common in the dataset.

4.2.1. Research on engagement