29 Organizations Promoting Food Literacy in Schools

Food literacy, the understanding that food choices affect human and planetary health, can be an important tool for building resilient individuals and communities. A combination of nutrition knowledge, culinary skill, food systems awareness, and behavioral change, food literacy is a multifaceted concept that has the power to shape local food systems.

Increasing food literacy can also help reduce health inequities, according to research from Western Michigan University and the University of Cologne. And research from Griffith University shows that schools are ideal settings for young people to learn and practice healthy dietary behaviors, and that food literacy boosts academic achievement.

“We know that if we make nutrition education hands-on and make it fun, we can engage students and get them excited about eating their veggies,” Food Literacy Center CEO Amber Stott tells Food Tank.

Around the world, organizations are using school-based culinary and agricultural programs to promote environmental stewardship and improve student health outcomes. Here are 29 organizations enriching student lives through food literacy education.

1. Ann Sullivan Centre, Peru

The Center Ann Sullivan del Peru (CASP) serves persons with disabilities and their families at every phase of life. Founded in 1979, CASP was inspired by international farm-to-school programs and built an on-site kitchen and garden for students in 2015 . Students practice cooking and team-building skills, and attend classes led by some of Peru’s top chefs.

2. Bright Bites, Canada

Bright Bites is a free program designed to improve school nutrition in Ontario, Canada. Entire schools or individual classes complete activities and earn badges, and are rewarded on social media. The Cook It Up badge, for example, requires students to cook a healthy meal together. And the Green Thumb badge encourages planting an indoor or outdoor garden. Participating schools have completed cafeteria beautification projects, distributed nutrient-dense holiday recipes to families, and blended homemade hummus in their classrooms.

3. Cidades Sem Fome, Brazil

Cidades Sem Fome (Cities Without Hunger) develops sustainable agrarian projects in São Paulo, Brazil. Founded in 2004, Cidades Sem Fome teaches individuals to manage organic farming businesses and achieve financial independence. In addition to greenhouse and community garden projects, the organization builds gardens in public schools, which provide fresh food for students and create opportunities for family involvement. Cidades Sem Fome has built 38 school gardens reaching 14,506 children.

4. CultivaCiudad, Mexico

Mexican nonprofit CultivaCiudad established the Huerto Tlatelolco Urban Garden on the side of an abandoned public housing unit in 2012. Now home to a seed bank and 45 tree varieties, Huerto Tlateloclo welcomes school groups to engage in urban agriculture. Since reclaiming the space, Huerto Tlateloclo has hosted 40 school groups and special events like markets and create-your-own meal workshops.

5. Edible Garden City, Singapore

Edible Garden City designs, builds, and maintains urban gardens across Singapore. In addition to commercial properties and private residences, Edible Garden City creates outdoor classrooms at primary schools and university residence halls that feature herbs, spinach, papaya, edible flowers, and tapioca. Nature-based workshops help demystify growing food in an urban environment, and virtual programs make learning accessible for remote learners.

6. Edible Schoolyard, Global

Edible Schoolyard offers food education programs at 5,691 schools worldwide. Founded in 1995 by chef and activist Alice Waters , Edible Schoolyard uses organic school gardens and cafeterias to teach academic subjects and sustainable food principles. Students plant, harvest, and prepare their own food while learning cornerstone practices of organic farming like composting, tillage, and cover cropping. Students also visit local farms, grocers, and restaurants. Edible Schoolyard has trained more than 1,000 education leaders and impacted over 1 million students worldwide.

7) Farm to School Network, United States

The National Farm to School Network (NFSN) seeks to transform the ways young people eat and learn about food in early care and education settings. Since 2007, NFSN helps schools purchase cafeteria food from local farmers, offer experiential learning through school gardens, and develop student activities related agriculture and nutrition. NFSN also works with Native producers from Hawaii to Alaska, planting heritage crops and including traditional foods like blue corn in cafeterias to revitalize Native foodways.

8. First Nations Development Institute, United States

The First Nations Development Initiative seeks to strengthen and support Native communities in the United States. They provide a Native farm-to-school resource guide that helps Native schools introduce students to traditional foods and practices, as well as promote self-reliance and sustainability. First Nations also offers scholarships to Native college students pursuing agriculture-related fields.

9. Food and Nutrition Education in Communities, United States

Cornell University’s Food and Nutrition Education in Communities (FNEC) program provides training and curricula to improve nutrition literacy in marginalized communities. In New York, FNEC administers the federally-funded Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program ( EFNEP ) and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program – Education ( SNAP-Ed ). In 2020, FNEC delivered EFNEP nutrition education to 7,484 students through hands-on, interactive lessons at school. FNEC also hosts independent courses teaching parents how to model healthy behaviors, increase breastfeeding awareness, and manage diabetes.

10. FoodCorps, United States

FoodCorps works with district leaders, food manufacturers, and government officials across the United States to provide sustainable school meals for students. The Flavor Bar program encourages students to experiment with condiments and flavor combinations from different cultures. The Tasty Challenge program allows students to sample ingredients prepared in different ways, then adds the most favored preparation to school lunch menus. After one year of participation, 73 percent of FoodCorps schools have measurably healthier food environments.

11. Food Literacy Center, United States

The Food Literacy Center in Sacramento, California teaches nutrition and gardening skills to children in 16 under-resourced elementary schools. Weekly after school programs teach students how to read nutrition labels and cook nourishing meals. Participants also study the environmental impact of food choices. The Food Literacy Center will open a zero net energy cooking school in 2021 that will house community and student gardens and continue integrating cooking into STEM curricula.

12. Food Literacy Project, United States

The Food Literacy Project ’s Youth Community Agriculture Program ( YCAP ) provides food-based education for immigrant and refugee students in Louisville, Kentucky. Prioritizing students in danger of aging out of traditional high school, YCAP helps accelerate English language skills and promote food systems engagement. Cohorts have built outdoor earthen ovens and translated recipes from their countries of origin for a virtual cookbook . In the summer, Food Literacy Project offers a seven-week employment opportunity for teenagers to complete a harvest cycle, cook with local chefs, and develop entrepreneurial skills with local business owners.

13. Fresh Roots, Canada

Fresh Roots is an edible schoolyard project in Vancouver, Canada that began in 2009. The organization hosts professional development workshops for educators demonstrating how gardens promote inquiry-based learning, hone leadership skills, and excite students. Together with the Vancouver School Board , Fresh Roots established the Schoolyard Market Gardens Program in 2013 to connect students with the effort involved in farming. Harvested produce is distributed to school cafeterias, a local Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) program, and nearby food security initiatives.

14. Gardeneers, United States

Founded in 2013, Gardeneers promotes racial justice and nutrition equity through school gardens in Chicago, Illinois. Custom gardens have been established at 19 schools in food insecure neighborhoods, impacting over 1,800 students. Students learn the nutritional benefits of fruits and vegetables, and bring home food they grow during the program. Gardeneers programs also encourage outdoor physical activity, and stress the importance of environmental stewardship.

15. Gitxaała Nation, Canada

Gitxaala Nation’s Community Garden and Lach Klan School work to decolonize food literacy education through a summer reading program and traditional food workshop program. With researchers from the University of British Columbia, they develop hands-on activities that integrate local Indigenous knowledge and language. Participants plant seeds, harvest seaweed, study Gitxaała Summer Foods books in English and Sm’algyax, and learn food preservation techniques. Guided by the idea of diduuls, the Sm’algyax concept meaning good life, program developers hope that connecting with the land, wellbeing, culture, and community will help students shape their current and future food systems.

16. Great Kids Farm, United States

Great Kids Farm provides opportunities for students to make the connection between farm and fork in Baltimore, Maryland. The 33 acre farm includes greenhouses, fields, and streams that offer a variety of agricultural experiences. On average, over 2,000 students visit the farm each year to plant seedlings or harvest food. In 2020, Great Kids Farm produced their first annual African American Foodways Summit , and offered seven paid internships to local high school students. In 2021, offerings include virtual field trips, recorded lectures, and a Facetime the Farmer program.

17. Green Bronx Machine, United States

Green Bronx Machine uses school-based urban agriculture to empower historically marginalized communities in the Bronx, New York. Rated one of the top ten health and wellness programs in the United States, Green Bronx Machine hosts a PBS television program, operates a community farm, and delivers backpacks full of food supplies to participating schools. In 2020, Green Bronx Machine grew over 5,000 pounds of food and served 2,300 meals daily.

18. Kitchen Garden Foundation, Australia

The Kitchen Garden Foundation helps children form lifelong healthy food habits at schools and childcare centers in Australia. The Foundation offers online resources and support to teachers at 1,598 locations. A 2017-2020 early childhood pilot program successfully trained 292 early childhood staff, and will be implemented nationally. Curricula focuses on the pleasurable aspects of food: taste, aroma, and social interaction.

19. Nourish, United States

Nourish increases health literacy through television and web content, short films, and classroom materials. A program of WorldLink , a sustainable education program developer, Nourish produces a free curriculum guide with videos for teachers to use in classrooms around the world. The organization’s self-titled film, Nourish, combines expert interviews with rich storytelling to examine the connection of food to public health, social justice, and climate change.

20. Ontario Edible Education Network, Canada

The Ontario Edible Education Network (OEEN) connects individuals and groups across Ontario that work with youth and healthy food systems. OEEN coordination allows non-profit organizations, public health units, farmers, teachers, administrators, and food service employees to work together on advocacy initiatives and share resources. Current initiatives include campaigning for Universal Student Nutrition Programs, and developing a searchable directory of mentor opportunities and food literacy resources across Ontario.

21. OzHarvest, Australia

OzHarvest is Australia’s leading food rescue organization. Founded in 2004, OzHarvest delivers surplus food to charities across the country and offers several education programs. FEAST encourages students to be food leaders in their communities through cooking classes and sustainability training. NOURISH trains vulnerable young adults for careers in hospitality and kitchen operation. To date, 165 students have graduated from NOURISH’s three program locations in Adelaide, Sydney, and Newcastle.

22. Project EATS, United States

New York City-based Project EATS combines art and urban agriculture to help communities thrive. Founded in 2009 by Guggenheim Fellow and Peabody Award recipient Linda Goode Bryant , Project EATS’ Enterprise Program works with neighborhoods to create small plot, high-yield farms that produce food for the community on a sliding scale. Roughly 3,000 public school students have participated in projects like farm apprenticeships, storytelling breakfasts, and school-wide projects. Project EATS holds eight farms across four boroughs, and publishes The Companion , a weekly English and Spanish magazine with recipes, stories, and art.

23. Rooftop Republic, Hong Kong

Rooftop Republic builds urban farms at schools, restaurants, and commercial spaces in Hong Kong. Through the Young Farmers Programme for students, Rooftop Republic teaches the principles of organic farming in classrooms. Classes include the science of plant growth and fermentation, nutrition fundamentals, waste reduction, and sustainability. If schools cannot accommodate an urban farm on campus, students are invited to participate in workshops like microgreen growing and natural soap making.

24. School Food Matters, United Kingdom

School Food Matters develops hands-on food education programs for schools in the United Kingdom. For example, the Breakfast Boxes program has delivered over 1 million healthy breakfasts to students at risk of food insecurity. The organization also offers grants to support school gardens, and allows students to build entrepreneurial skills by selling their harvest. School Food Matters participates in national advocacy campaigns as well, including requesting a school food policy review following the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic.

25. School + Home Gardens, Philippines

School + Home Gardens (S+HG) is a pilot program to increase student nutrition knowledge in the province of Laguna, Philippines. A collaboration between the Southeast Asian Regional Center for Graduate Study and Research in Agriculture (SEARCA), the University of the Philippines Los Baños (UPLB), and the Department of Education of the Philippines, S+HG has expanded from six to 28 locations. Participants harvest food from school gardens for use in school meals and share seeds and resources with families to encourage home gardening.

26. Slow Food, Global

Slow Food International is a global organization dedicated to preserving traditional food culture and sustainable production. Through programs in 160 countries, Slow Food facilitates educational activities like school gardening, guided tastings, and farm visits. Organizers also created a multilingual educational kit for teachers to explore Slow Food themes like biodiversity with their students. In 2004, Slow Food founded the University of Gastronomic Sciences , where the Academic Tables initiative treats the on-site cafeteria as a training venue. Students meet visiting chefs, eat seasonal dishes, and use a reservation system to reduce waste.

27. Spoons Across America, United States

Spoons Across America promotes the long-term benefits of healthy diets in schools, community organizations, and health care centers in the United States. Programs engage students directly by encouraging observations about the appearance, texture, scent, and taste of different foods. Founded in 2001, Spoons Across America reached 25,000 children in New York City public schools through primary school curricula, family dinner parties , and afterschool programs. They also publish resources for homeschooled children and virtual learners.

28. The School Garden Doctor, United States

The School Garden Doctor puts food at the intersection of science and literacy instruction at schools in Napa, California. Founded in 2018, School Garden Doctor’s signature program Dirt Girls gives young women access to STEM learning through horticultural science. In 2021, Dirt Girls provided 100 plants to participants and hosted 36 virtual sessions. The organization’s blog, Gleaning the Field , provides garden-enhanced education resources for schools and families.

29. Wellness in the Schools, United States

Wellness in the Schools (WITS) works with school leadership to improve cafeteria menus and provide nutrition education to students in New York, New Jersey, Florida, and California. Founded in 2005 by a concerned public school parent, WITS’ Cook for Kids program trains food service workers to cook healthy foods, and provides a daily salad bar and fresh fruit at each location. Program participants eat 40 percent more fruits and vegetables than other students, and play more vigorously during activity time. WITS serves 95,000 students in over 190 schools.

Senator Booker’s Legislation Aims to Reform U.S. Farm Systems

Nyc nonprofit gives new life to brooklyn community garden.

Never miss an article:

Sign up and join more than 350,000 food tank newsletter subscribers:.

- Become A Member

- Upcoming Events + Webinars

- Write For Us

You have Successfully Subscribed!

- Submit Member Login

Access provided by

Nourishing Knowledge: Food Education Joins the Core Subjects in Schools

Download started

- Download PDF Download PDF

- Add to Mendeley

Article metrics

Related articles.

- Download Hi-res image

- Download .PPT

- Access for Developing Countries

- Articles & Issues

- Articles In Press

- Current Issue

- List of Issues

- Supplements

- For Authors

- Author Guidelines

- Submit Your Manuscript

- Statistical Methods

- Guidelines for Authors of Educational Material Reviews

- Permission to Reuse

- About Open Access

- Researcher Academy

- For Reviewers

- General Guidelines

- Methods Paper Guidelines

- Qualitative Guidelines

- Quantitative Guidelines

- Questionnaire Methods Guidelines

- Statistical Methods Guidelines

- Systematic Review Guidelines

- Perspective Guidelines

- GEM Reviewing Guidelines

- Journal Info

- About the Journal

- Disclosures

- Abstracting/Indexing

- Impact/Metrics

- Contact Information

- Editorial Staff and Board

- Info for Advertisers

- Member Access Instructions

- New Content Alerts

- Sponsored Supplements

- Statistical Reviewers

- Reviewer Appreciation

- New Resources

- New Resources for Nutrition Educators

- Submit New Resources for Review

- Guidelines for Writing Reviews of New Resources for Nutrition Educators

- Podcast/Webinars

- New Resources Podcasts

- Press Release & Other Podcasts

- Collections

- Society News

The content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Accessibility

- Help & Contact

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- E-Collections

- Virtual Roundtables

- Author Videos

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- About The European Journal of Public Health

- About the European Public Health Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Explore Publishing with EJPH

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

Food and Nutrition Literacy as means to fight against inequalities in diet and nutrition

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

G Bonaccorsi, C Lorini, Food and Nutrition Literacy as means to fight against inequalities in diet and nutrition, European Journal of Public Health , Volume 33, Issue Supplement_2, October 2023, ckad160.210, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckad160.210

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The concepts of nutrition (or nutritional) (NL) literacy, food literacy (FL), and the extensively described concept of health literacy (HL) are based on the same idea of increasing the degree to which individuals and groups can access and use specific information needed to make health decisions that benefit the community. More specifically, the terms of FL and NL refer to a set of knowledge, competencies, and abilities that are necessary for people to use information regarding food and nutrition in order to achieve and preserve a healthful diet. Nonetheless, the core elements of the two constructs partially differ, since NL mostly involves nutritional information and individuals’ capacity or interest in relation to accessing and using such information in order to maintain nutritional health status, while FL considers mainly the relationship between people and food (or food system) and the capacity to use food responsibly. From a public health nutrition perspective, NL/FL could help to identify individuals with low diet quality and unhealthy eating habits that make them at higher risk of chronic diseases and other health consequences. In fact, although a very large amount of information about food and nutrition is now available to citizens/consumers, they often struggle to recognize evidence-based information and effectively manage their diet in the current “dietary infodemic”. Thus, there is a need to develop and implement interventions in order to increase the public's NL/FL level, beginning from establishing valid instruments to measure the NL/FL and finding specific targets on which to intervene by education and other preventive measures, so as to develop specific awareness to counteract the pressure from GDOs and the effects generated by commercial determinants.

- chronic disease

- health status

- science of nutrition

- public health medicine

- health literacy

- evidence-based practice

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2023 | 4 |

| November 2023 | 16 |

| December 2023 | 3 |

| January 2024 | 6 |

| February 2024 | 1 |

| March 2024 | 4 |

| April 2024 | 7 |

| May 2024 | 6 |

| June 2024 | 7 |

| July 2024 | 7 |

| August 2024 | 15 |

| September 2024 | 2 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Contact EUPHA

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1464-360X

- Copyright © 2024 European Public Health Association

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

For immediate release | January 13, 2020

Food literacy programs, resources, and ideas for libraries

CHICAGO — Food is more than just a basic human need—learning about it and enjoying it can be important social activities. As Hillary Dodge demonstrates in her new book “ Gather ‘Round the Table: Food Literacy Programs, Resources, and Ideas for Libraries ,” published by ALA Editions, food literacy initiatives are a natural fit for libraries. Food programming such as cooking can be an important tool in helping English language learners discover a practical use for a new language, as well as providing opportunities for socialization and conversation. It can be used to help GED seekers practice basic math. And, playing with food can be a sensory-integrative way to help new parents and their babies learn about healthy food choices. Featuring a multi-pronged approach to incorporating food literacy in public, school, and special libraries, this all-in-one resource:

- presents a definition of food literacy that shows how the concept touches upon important topics such as culinary skills, food security, nutrition and dieting, food allergies, health literacy, and food ethics;

- discusses the community impacts of food-related issues;

- walks readers through planning and undertaking a community food assessment, a process that can be used to identify a need, justify a service response, build buy-in and engagement, and plan for the allocation of resources;

- shares a variety of innovative food literacy programs drawn from libraries across the country, from cookbook and recipe clubs to an edible education garden, teen cooking classes, and offsite cooking demos; and

- provides information about additional resources and reference sources relating to the culinary world, including advice on collection development.

Dodge is an author, editor, and librarian. She has worked in the library and information science field for over 15 years, most recently as the Director for the North Region with the Pikes Peak Library District in Colorado Springs, Colorado. In 2016, Hillary and her husband quit their jobs to relocate their family to South America to pursue a culinary research project. Their travels are detailed in their forthcoming cookbook, “The Chilean Family Table.” Her other publications include “Careers for Tech Girls in Digital Publishing” and “The Evolution of Medical Technology.”

ALA Store purchases fund advocacy, awareness and accreditation programs for library professionals worldwide. ALA Editions and ALA Neal-Schuman publishes resources used worldwide by tens of thousands of library and information professionals to improve programs, build on best practices, develop leadership, and for personal professional development. ALA authors and developers are leaders in their fields, and their content is published in a growing range of print and electronic formats. Contact ALA Editions at (800) 545-2433 ext. 5052 or [email protected].

Related Links

"Gather ‘Round the Table: Food Literacy Programs, Resources, and Ideas for Libraries"

"Rainy Day Ready: Financial Literacy Programs and Tools"

"50+ Programs for Tweens, Teens, Adults, and Families: 12 Months of Ideas"

Rob Christopher

Marketing Coordinator

American Library Association

ALA Publishing

Share This Page

Featured News

August 19, 2024

ALA Opens 2025 Annual Conference & Exhibition Call for Proposals

CHICAGO — ALA invites education program and poster proposals for the 2025 Annual Conference & Exhibition, taking place June 26 – July 1, 2025, in Philadelphia. The submission sites are open now through September 23, 2024.

press release

July 25, 2024

Sam Helmick chosen 2024-2025 American Library Association president-elect

The American Library Association Council decided on Tuesday, July 23, 2024, that Sam Helmick will be the 2024-2025 president-elect effective immediately.

July 9, 2024

New Public Library Technology Survey report details digital equity roles

Nearly half of libraries now lend internet hotspots; 95% offer digital literacy training CHICAGO — The Public Library Association (PLA) today published the 2023 Public Library Technology Survey report. The national survey updates emerging trends around...

July 2, 2024

Hohl inaugurated 2024-2025 ALA president

Cindy Hohl, director of policy analysis and operational support at Kansas City (Mo.) Public Library, was inaugurated ALA President for 2024-2025 on Tuesday, July 2, at the ALA Annual Conference in San Diego.

May 7, 2024

ALA partners with League of Women Voters to empower voters in 2024

The American Library Association and League of Women Voters today announced a new partnership to educate and empower voters in 2024.

April 17, 2024

The TRANSFORMERS Are Ready to Roll Out for Library Card Sign-Up Month

The American Library Association (ALA) is teaming up with Skybound Entertainment and Hasbro to encourage people to roll out to their libraries with the TRANSFORMERS franchise, featuring Optimus Prime, as part of Library Card Sign-Up Month in September.

April 10, 2024

American Library Association Launches Reader. Voter. Ready. Campaign to Equip Libraries for 2024 Elections

Today the American Library Association (ALA) kicks off its Reader. Voter. Ready. campaign, calling on advocates to sign a pledge to be registered, informed, and ready to vote in all local, state and federal elections in 2024.

April 8, 2024

ALA kicks off National Library Week revealing the annual list of Top 10 Most Challenged Books and the State of America’s Libraries Report

The American Library Association (ALA) launched National Library Week with today’s release of its highly anticipated annual list of the Top 10 Most Challenged Books of 2023 and the State of America’s Libraries Report, which highlights the ways libraries...

Pun wins 2025-2026 ALA presidency

Raymond Pun, Academic and Research Librarian at the Alder Graduate School of Education in California has been elected 2024-2025 president-elect of the American Library Association (ALA).

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Restaurant Food Safety

- Resources for Restaurants

- Publications

- Research Accomplishments

- Investigations Accomplishments

- Investigations

- Improving Practices

Food Safety Culture

At a glance.

We surveyed staff members from 331 restaurants across eight states and localities. We asked what they thought about their restaurant's food safety culture. Learn what contributes to a strong food safety culture in restaurants.

Key takeaways

Restaurant managers help set the tone for a strong food safety culture by showing a personal commitment to food safety and having food safety training and policies in place. Adequate supplies for food safety practices and employee commitment to food safety are also critical to having a strong food safety culture at a restaurant.

Restaurant managers can use our tool to assess their food safety culture. Explore workers' beliefs about food safety, track progress over time, and see what practices are strengthening or weakening your restaurant's food safety culture.

Download our food safety culture tool with:

- Tab 1 – Form to give restaurant workers

- Tab 2 – Scoring tool for restaurant managers

- Tab 3 – Scoring tool with automatic tallying based on workers' responses

- Tab 4 – Example of scoring tool with automatic tallying

Why this is important

A restaurant's food safety culture is the shared beliefs of restaurant personnel that affect their practices in ways that impact food safety. A weak food safety culture is emerging as a common risk factor for foodborne outbreaks.

The food safety beliefs and behaviors of restaurant personnel could affect a restaurant's food safety practices. The food safety culture of a restaurant either promotes or discourages safe food practices.

What we learned

We found four key components of a strong food safety culture in restaurants:

- Leadership – Managers offer food safety training and policies.

- Manager Commitment – Managers are committed to and prioritize food safety.

- Employee Commitment – Employees are committed to food safety.

- Resources – The restaurant has sufficient resources to support food safety, such as enough soap and sinks for handwashing.

A study in Southern Nevada also found that training promoted a strong food safety culture, along with restaurant managers expressing appreciation for staff and routine two-way communication between managers and staff. They found obstacles to strong food safety culture included staff reluctance to talk to managers, short staffing, and lack of space and resources.

More information

Food safety culture tool for restaurant managers

Journal article this plain language summary is based on

More practice summaries and investigation summaries in plain language

Persons with disabilities experiencing problems accessing the food safety culture tool for restaurant managers (spreadsheet) should contact CDC-INFO and ask for a 508 Accommodation [PR#9342] for A0209-NCEH-WBL8.

About this study

Restaurant practices and policies can increase or decrease risk of outbreaks

For Everyone

Public health.

- Teacher Center

- Student Center

- Get Involved

Login to MyBinder

Forgot password

Don't have an account? Create one now!

View a MyBinder tutorial

Agricultural Literacy Curriculum Matrix

Lesson plan, grade levels, type of companion resource, content area standards, agricultural literacy outcomes, common core, foodmaster middle: food safety, grade level.

Students will understand water-based state changes that occur at varying temperatures, recognize the importance of the proper hand washing technique for general health and disease prevention, understand the factors that impact mold growth and their application to food safety, and explore ways to prevent foodborne illness. Grades 6-8

Estimated Time

Four 1-hour activities

Materials Needed

Lab 1 Teacher Materials:

- Safety goggles, apron, oven mitt, hot plate or double burner, thermometer, kitchen timer/stopwatch, and 1 medium pot with water filled 1/2-3/4 full

Lab 1 Student Materials, per group of 4-5 students:

- Safe Practices student handout , 1 per student ( Key )

- Changing States lab sheet, 1 per student ( Key )

- 1 cup of ice chips in a 6-ounce styrofoam cup

- 1 styrofoam cup of water filled 1/2 way

- 1 thermometer

- 1 kitchen timer or stopwatch

Lab 2, per group of 4-5 students

- Invisible Creatures lab sheet , 1 per student

- Safety goggles

- Aprons (optional)

- Glo Germ TM

- Access to warm water

- Colored pencils or markers

Lab 3, per group of 4-5 students

- Multiplying Organisms lab sheet , 1 per student ( Key )

- Safety goggles and aprons (optional)

- 1 slice of white bread

- 2 slices of apple

- 2 pieces of cheese

- 1 paper plate

- 1 plastic sandwich bag

- 1 plastic knife

- 1 black permanent marker

- 1 microscope (optional)

- 2-3 microscope slides (optional)

Investigating Your Health Activity:

- Fearless Food Safety student handout, 1 per student ( Key )

Essential Files

- Safe Practices Teacher Key

aerobic: a chemical reaction that must have oxygen to occur

anaerobic: without the use of oxygen

bacteria: a group of single-celled living things that cannot be seen without a microscope that reproduce rapidly and sometimes cause diseases

celsius scale: a temperature scale characterized by a freezing point of 0 degrees and a boiling point of as 100 degrees

cross contamination: the process by which bacteria is unintentionally transferred from one substance or contaminated object to another

fahrenheit scale: a temperature scale characterized by a freezing point of 32 degrees and a boiling point of 212 degrees

food safety: the practice of handling, preparing, and storing food in a way that prevents food-borne illness

foodborne illness: any illness resulting from the consumption of food contaminated with viruses, parasites, or pathogenic bacteria

germ: a microorganism causing disease

microorganism: any organism, such as a bacterium, protozoan, or virus, of microscopic size

temperature: a measure of kinetic energy of a group of molecules; indirect measure of molecular motion

thermometer: an instrument used for measuring and indicating the temperature of a substance

Did You Know?

- Each year roughly one out of six Americans get sick from a foodborne disease. 1

- Everybody from the farm to your fork is responsible for keeping food safe.

- The majority of people will experience a food or water borne disease at some point in their lives, regardless of where they live in the world. 2

Background Agricultural Connections

FoodMASTER (Food, Math and Science Teaching Enhancement Resource) is a compilation of programs aimed at using food as a tool to teach mathematics and science. For more information see the Background & Introduction to FoodMASTER . This lesson is one in a series of lessons designed for middle school.

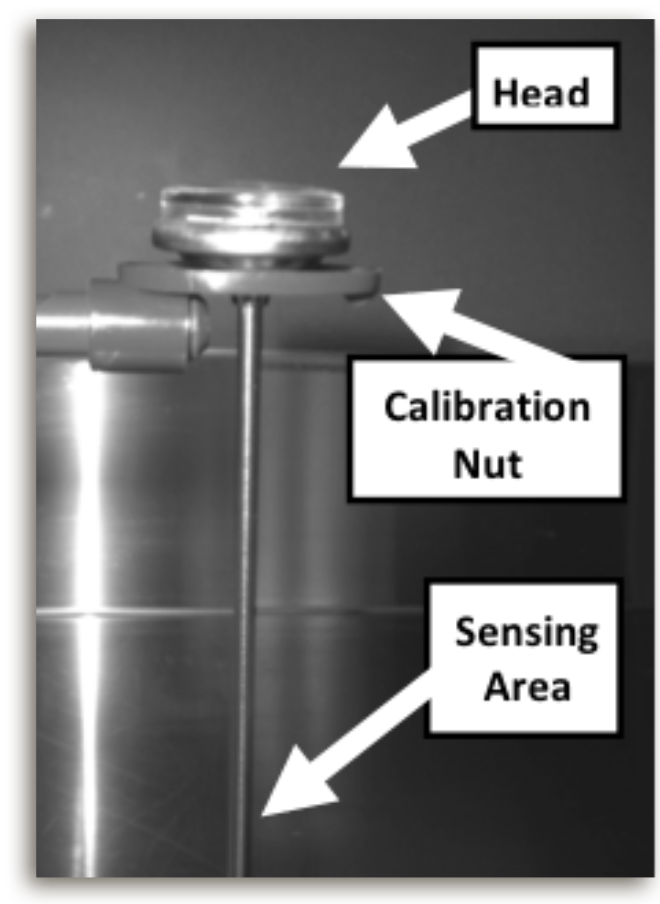

State changes, like melting and vaporization, can be used to calibrate thermometers for cooking. Thermometers must be calibrated to ensure accuracy and ultimately prevent under- or over-cooking food. Consumption of under-cooked food can lead to foodborne illness . For example, consuming chicken before it reaches an internal temperature of 165°F could lead to salmonella poisoning. A thermometer must be calibrated to within +/- 2 °F (1.1 °C) of the actual temperature to ensure accuracy. There are two simple methods used to determine actual temperature: Boiling Water Method and Ice Water Method. A thermometer can be submersed in either boiling or ice water and calibrated to the respective temperature. Boiling water undergoes the process of evaporation. The ice water method involves the process of melting, allowing the heat to break the molecular bonds in the ice to form more liquid and a consistent temperature.

- Fill a quart-size container with crushed ice and then add a small amount of clean tap water. You should have a lot of ice and only a little water.

- Insert the thermometer so that the whole sensing area (from tip to dimple) is completely submerged for 30 seconds or until the indicator stops moving. (See illustration to the right.)

- If the temperature is at 32°F, the thermometer is ready for use. If the temperature is not at 32°F, then hold the calibration nut (just below the temperature dial) securely with a wrench or other tool and rotate the head of the thermometer until it reads 32°F.

- You should recalibrate the thermometer if you drop or bang it during use.

More tips on using a bimetallic stemmed thermometer:

- Before testing temperatures, be sure your thermometer is cleaned, sanitized, and properly dried.

- When checking the temperature of food (e.g. meat), be sure to measure internal temperatures in the thickest part. Be sure the whole sensing area is inserted. The thermometer should not touch bone, fat, gristle or the pan. For thin items such as hamburgers, insert the thermometer from the side into the middle of the meat.

- Cooking temperatures are typically reported using the Fahrenheit scale. The Fahrenheit scale of water is a scale of temperatures ranging from 32° (melting point of ice) to 212° (boiling point of pure water under standard atmospheric pressure).

Proper Cooking Temperatures:

- Ground Beef 160 °F

- Poultry 165 °F

- Pork 145 °F

- Fish 145 °F

- Leftovers 165 °F

- Casseroles 165 °F

There are four main types of microorganisms that can cause disease: bacteria, viruses, molds, and fungi. These microorganisms are also referred to as pathogens . It is important to understand pathogens and how they grow to prevent disease. Bacteria are single-celled microorganisms that can be found in many environments. Some can even thrive in extreme temperatures. Not all bacteria are harmful, but it is important to prevent the spread of harmful bacteria by taking proper food safety precautions. Viruses require a living host, like people or animals, to survive. They only survive to multiply, which is harmful for its host. Molds are multi-celled organisms that can be found on food. Most molds prefer warmer temperatures; however, some molds can survive on salt and sugar, making it easier to survive in colder temperatures. These molds can thrive on foods in the refrigerator, like fruit and salty meats. There are many factors that can affect microbial growth. To remember what these factors are use the mnemonic device FAT TOM (Food, Acidity, Time, Temperature, Oxygen, Moisture). Fungi are eukaryotic organisms that are found in soil. Foods such as sweet potatoes, corn, and nuts have been found to grow pathogenic fungi. Food high in protein, like milk and eggs, are more susceptible to microbial growth. To prevent microbial growth, food must not be in the temperature danger zone (40 - 140 °F) for more than two hours. Foods susceptible to microbial growth contain certain nutrients that can be found in protein-rich foods, like milk and eggs. Foods with little to no acidity are considered the best host for pathogen growth; however, bacteria can thrive in a slightly acidic pH (4.6) as well. Most microbes, or pathogens in this case, are aerobic and require oxygen for growth. Those that do not require oxygen are called anaerobic . Foods high in moisture promote microbial growth because many pathogens require water for growth. In the end, molds can be harmful or beneficial. Harmful molds grow on the surface of dry foods like bread. Beneficial molds grow inside of foods, like Blue cheese.

- To introduce the lesson, begin by drawing on your student's prior knowledge. Ask them, "What principles do you follow at home in order to keep your food from spoiling or making you sick?" If necessary, use more guiding questions for students to identify that they keep some food in the refrigerator, they put groceries in the fridge/freezer as soon as they get home from the store, they cook foods thoroughly, etc.

- Hamburger (Cattle)

- Bacon (Pigs)

- Bread (Wheat)

- Sugar (Sugarbeets or sugar cane)

- Eggs (Chickens)

- Yogurt (Cows)

- Chicken (Chicken nuggets or chicken fingers)

- Cheese (Cows)

- Corn flour (corn)

- Sausage (Pigs)

- Farm: Farmers take good care of their animals and crops. They follow guidelines and practices to produce food that is healthy and safe. Dairy farmers cool their milk immediately and store it in a refrigerated tank to minimize the growth of bacteria that could make us sick. Farmers also work hard to keep their farm and equipment clean and sanitized to stop the spread of harmful bacteria.

- Processing Plant: The processing plant is where a raw food product is prepared for retail sale. For example, milk is pasteurized, homogenized and processed into butter, cheese, ice cream or other dairy products at a processing plant. Meat can be cut and packaged at a processing plant or made into hamburger, sausage or sandwich meat. Processing plants have strict guidelines for sanitation and cleanliness to keep our food safe. Workers wear hair nets and clean, protective clothing.

- Grocery Store: Most consumers purchase their food from a retail grocery store. Grocery stores ensure that food is kept at the proper temperature and that it is not kept on the shelf too long.

- Your Home: Today, students will be learning what they can do at home to help keep their food safe and healthy.

- How can temperature play a role in food safety

- How does bacteria (unicellular organisms) play a role in spreading disease?

- How can foodborne illness be prevented?

- Inform students that they will be learning the answers to these questions.

Explore and Explain

Food Exploration Lab 1: Changing States

Teacher Preparation:

- Review information found in the Background Agricultural Connections section of the lesson, lesson procedures ( Explore and Explain ), and the attached Essential Files.

- Styrofoam cup of water (filled half way) that has reached room temperature

- Consider identifying one student group to help you with the teacher demonstration (e.g. set-up, recording data on the board).

- You may use Celsius or Fahrenheit thermometers in this lab. Example answers are reported in Fahrenheit.

- Consider providing your students with time to practice using Celsius and/or Fahrenheit thermometers correctly prior to beginning the lab.

Lab Procedures:

- Distribute materials. It is recommended that materials are organized into stations for easier distribution. Students should be arranged in small groups of 4-5. Each group should receive the lab supplies outlined in the Materials section of this lesson and one copy of the Safe Practices student handout and Changing States lab sheet .

- Ask students to read Safe Practices (page 1-2) and complete the "Think About It" questions (page 3) for this lab investigation.

- Prepare to begin the lab investigation by requiring students to wash their hands and emphasizing the importance of practicing good food safety behaviors by not consuming substances used as part of the lab investigation.

- Fill a medium pot half way with room temperature water. Insert a thermometer to measure the temperature of the water prior to heating. The thermometer should not touch the sides or bottom of the pot when measuring the temperature of the water. Also, be sure to keep the thermometer immersed in the water when taking the temperature. Remind students to practice this as well.

- Turn on a burner and begin to warm the pot of water. Set your timer for 10 minutes.

- Important Note: Be careful when handling the thermometer. Due to heat transfer from the boiling water, the thermometer may be hot to touch. For safety, use an oven mitt when reading the thermometer.

- Measure the temperature of the water every two minutes for 10 minutes (water needs to be heated to the boiling point). Have students record these temperatures in their lab notes.

- Once the water reaches a rolling boil, wait 30 seconds and then read the temperature on the bimetallic thermometer. At sea level, the temperature should read 212°F while still submerged in the boiling water. If you are cooking at a higher altitude, water will boil at a slightly lower temperature due to the reduced air pressure. For example, at 2,000 feet above sea level, the boiling temperature of water is 208°F. If the thermometer reads a different temperature, adjust the thermometer to read the correct temperature. If you are unable to calibrate your thermometer simply add or subtract the difference (actual temperature +/- 32F). For more information on calibrating a bimetallic stemmed thermometer see information found in the Background Agricultural Connections section of this lesson.

- After mixing room temperature water with ice, students should begin to observe a decrease in the water’s temperature. After several minutes, the temperature should read approximately 32°F or 0°C (freezing) if the thermometer was properly calibrated. Students may not observe any immediate state changes; however, the warmer temperature of the water will cause the ice chips to slowly melt from a solid to a liquid. By the end of the class, students should clearly see this state change.

- Allow students to work in small groups to complete the remaining pages of their lab sheet.

- Follow-up with a class discussion about the importance of using accurate tools and methods of measurement. Remind students about the role temperature plays in food preparation and the prevention of foodborne illness.

Food Exploration Lab 2: Invisible Creatures

- Review information found in the Background Agricultural Connections section of the lesson, lesson Procedures , and the attached Essential Files.

- Student groups can share the Glo Germ™ and UV light.

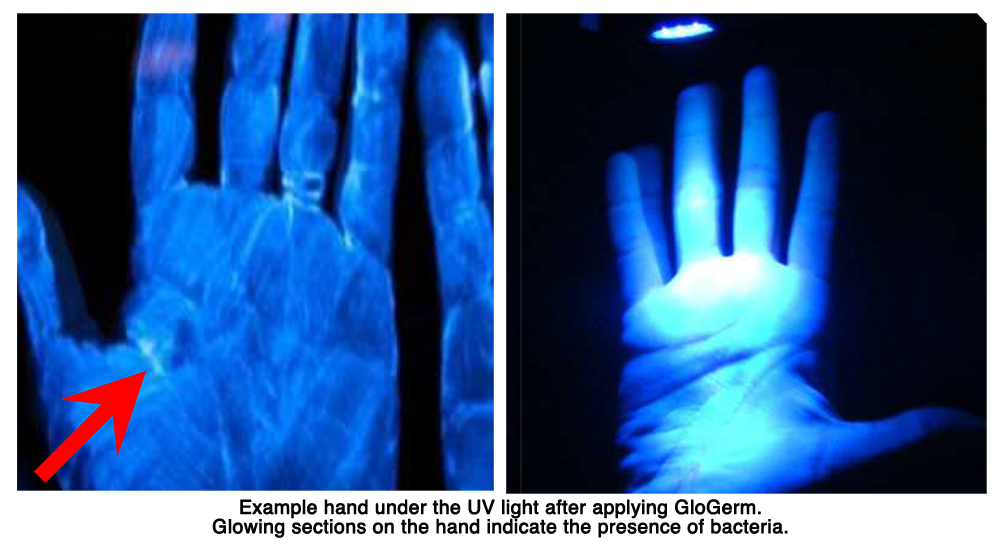

- Glo Germ™ is a liquid, gel or powder that contains plastic simulated bacteria. The UV light will illuminate the simulated bacteria to allow students to test the effectiveness of their hand washing practices. It is important for students to understand the glowing bacteria on their hands are not real bacteria, but rather simulated bacteria from the Glo Germ TM product.

- Glo Germ™ only works with a UV light, and simulated bacteria are best observed in a darkened room. Guide students through the procedure together, so that the room can be darkened during periods of observation.

- If you do not have access to a sink in your classroom, consider assigning 1-2 students (or 1 student per group) to participate in the hand-washing portion of the lab. These students can return to the classroom and demonstrate the remaining portions of the lab.

Laboratory Procedures:

- Note: Be sure students have already read Safe Practices and completed the "Think About It" questions as outlined in Lab 1 .

- In this lab, students should not wash their hands prior to beginning the lab investigation.

- Launch the lab by asking students to respond to the investigation question at the bottom of page 1 of their Food Safety Student Handbook about where bacteria are most concentrated on their hands.

- Palm: The palm of the hand should show simulated bacteria. The bacteria will likely be concentrated within the creases of the palm.

- Finger Nails: Fingernails should show a large concentration of simulated bacteria, particularly around the bed of the nail.

- Wrist: The wrist should show some simulated bacteria, particularly on the underside.

- Fingers: Fingers may show some simulated bacteria, especially within the creases of the knuckles.

- Thumb: The thumb should show a good amount of simulated bacteria present.

- Instruct the students to wash their hands using warm water and soap.

- After the hand washing, students should again view their hand under the UV light. Many may still observe a large amount of bacteria present around the nail bed, on the wrist, and the back of the hand. These are areas people tend to forget about when washing their hands.

- Allow students to work in small groups to complete the lab sheet and respond to lab questions.

Food Explorations Lab 3: Multiplying Organisms

Teacher Preparation

- Timesaver: Prepare food samples ahead of time for student observation and quicker lab completion. You may also consider having one set of samples for the entire class versus each group.

- Note: Be sure students have already read Safe Practices and completed the "Think About It" questions as outlined in Lab.

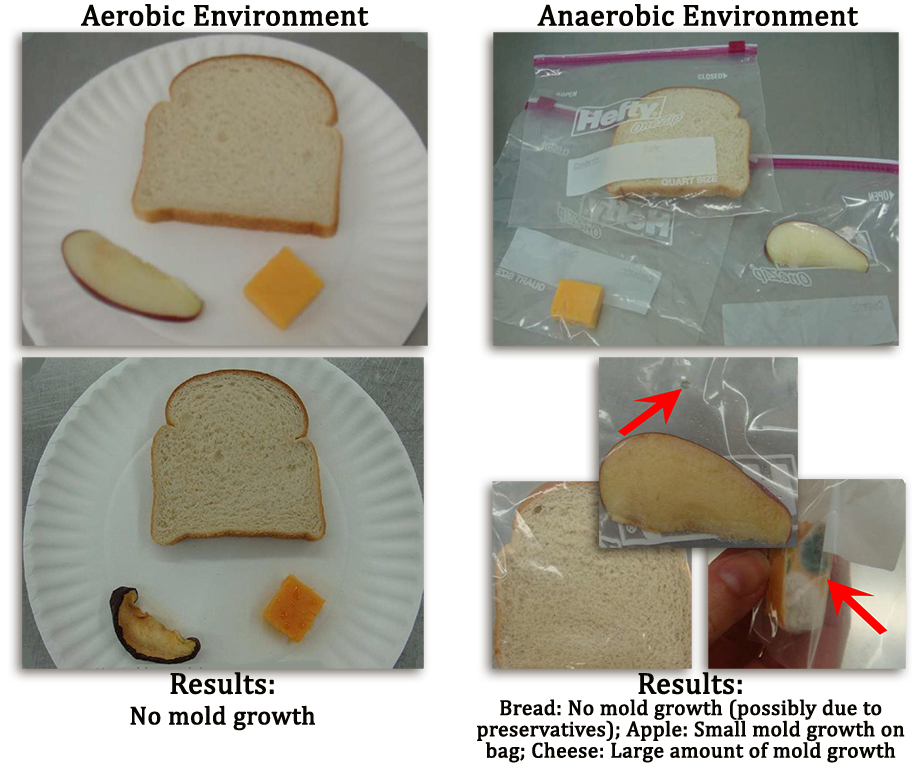

- Aerobic : Some mold growth may be observed on the foods that were exposed to the aerobic environment. The foods should be dry and in some cases smaller in size due to the loss of moisture content.

- Anaerobic : A significant amount of mold growth should be observed on the foods that were exposed to an anaerobic environment. The most mold growth will likely occur on the cheese.

- Follow-up with a class discussion about mold growth on food and its relevance to food safety.

- Give each student 1 copy of the Fearless Food Safety worksheet and assign students to complete. This activity is designed to be completed as homework or in class.

- See the attached Teacher Key for answers to the lab questions.

- If completed in-class, allow students to work in small groups on the worksheet to further explore the topic and respond to questions.

- Follow-up with a class discussion about the importance of hand washing and student generated ideas for preventing foodborne illness.

Use the calibrated thermometers to explore state changes in other substances.

Explore factors that can impact state changes (i.e. the addition of salt to ice or boiling water).

Explore the different boiling points of various liquid substances.

Use petri dishes to grow bacteria obtained on the body or from various surfaces in the school environment.

Explore how temperature impacts mold growth.

After conducting these activities, review and summarize the following key points:

- Substances undergo a phase change when they are converted from one state to another. Examples include freezing, evaporating, and melting.

- A properly calibrated thermometer should be used to check the cooking temperatures of meat to decrease the chances of foodborne illness.

- Bacteria, viruses, molds, and fungi are all microoganisms that can cause disease.

- Proper food safety procedures decrease the chances of foodborne illness.

- http://www.eatright.org/resource/homefoodsafety/safety-tips/food-poisoning/food-safety-facts-and-figure

- http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/2015/04/07/food-safety-world-health-day-2015_n_7017884.html

Acknowledgements

This lesson was partnered with East Carolina University. The FoodMASTER program was supported by the Science Education Partnership Award (SEPA) which is funded from the National Center for Research Resources , a component of the National Institutes of Health.

- Virginia Stage, PhD, RDN, LDN

- Ashley Roseno, MAEd, MS, RDN, LDN

- Melani W. Duffrin, PhD, RDN, LDN

- Graphic Design: Cara Cairns Design, LLC

Recommended Companion Resources

- Dirt to Dinner

- Eat Happy Project video series

- Food Safety A to Z Reference Guide

- Food Safety from Farm to Fork: How Fast Will They Grow?

- Food Safety from Farm to Fork: Mighty Microbes

- Food Safety from Farm to Fork: Operation Kitchen Impossible

- Food Safety from Farm to Fork: Playing it Safe

- Germ Stories

- Glo Germ Set

- Virtual Food Safety Labs

- Virtual Labs: Understanding Water Activity

Organization

| We welcome your feedback! If you have a question about this lesson or would like to report a broken link, please send us an email at . If you have used this lesson and are willing to , we will provide you with a coupon code for 10% off your next purchase at . |

Food, Health, and Lifestyle

- Identify forms and sources of food contamination relative to personal health and safety (T3.6-8.h)

- Demonstrate safe methods for food handling, preparation, and storage in the home. (T3.6-8.a)

Education Content Standards

Career & technical education (career).

FCSE (Grades 6-8) Food Production and Services 8.0

- 8.2.5 Practice standard personal hygiene and wellness procedures.

Science (SCIENCE)

MS-LS2 Ecosystems: Interactions, Energy, and Dynamics

- MS-LS2-1 Analyze and interpret data to provide evidence for the effects of resource availability on organisms and populations of organisms in an ecosystem.

- MS-LS2-2 Construct an explanation that predicts patterns of interactions among organisms across multiple ecosystems.

Common Core Connections

Anchor standards: language.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.L.1 Demonstrate command of the conventions of standard English grammar and usage when writing or speaking.

Anchor Standards: Reading

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.1 Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.3 Analyze how and why individuals, events, or ideas develop and interact over the course of a text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.4 Interpret words and phrases as they are used in a text, including determining technical, connotative, and figurative meanings, and analyze how specific word choices shape meaning or tone.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.7 Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse media and formats, including visually and quantitatively, as well as in words.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.R.10 Read and comprehend complex literary and informational texts independently and proficiently.

Anchor Standards: Speaking and Listening

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.SL.1 Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively.

Anchor Standards: Writing

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.W.2 Write informative/explanatory texts to examine and convey complex ideas and information clearly and accurately through the effective selection, organization, and analysis of content.

How can we help?

Send us a message with your question or comment.

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Research Tools

- Food Safety Research Projects Database

Low Literacy Food Safety Education for Food Service/Food Processing Employees

A significant portion of food-borne illness is caused by poor hygiene or poor food handling procedures of food service workers and food processing employees. The goal of this project is to improve food safety practices of low literacy food service and food processing employees. To achieve this goal, a packaged,efficient set of food safety training materials will be developed and tested. The curriculum will be largely pictorial (in the form of a pictorial flip chart) and will be adapted for use by both English- and Spanish- speaking clientele.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- PMC10378922

Food and Nutrition Literacy: Exploring the Divide between Research and Practice

Paula silva.

1 Laboratory of Histology and Embryology, Department of Microscopy, School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences (ICBAS), University of Porto (U.Porto), Rua Jorge Viterbo Ferreira 228, 4050-313 Porto, Portugal; tp.pu.sabci@avlisp

2 iNOVA Media Lab, ICNOVA-NOVA Institute of Communication, NOVA School of Social Sciences and Humanities, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa, 1069-061 Lisbon, Portugal

Associated Data

The data used to support the findings of this study can be made available by the corresponding author upon request.

This study addresses the growing recognition of the importance of food and nutrition literacy, while highlighting the limited research in this field, particularly the gap between research and practice. A bibliometric analysis of publications on food and nutrition literacy research from the Scopus database was carried out. Endnote 20, VOSviewer, and Harzing’s Publish or Perish were used to analyze the results. The growth of publications, authorship patterns, collaboration, prolific authors, country contributions, preferred journals, and top-cited articles were the bibliometric indicators used. Subsequently, articles aimed at measuring food or nutrition literacy-implemented programs were analyzed. Existing studies have primarily concentrated on defining and measuring food or nutrition literacy. Although interventions targeting food and nutritional literacy have shown promise in promoting healthy eating, further research is required to identify effective approaches in diverse populations and settings. This study emphasizes the need for additional research to measure intervention program efficacy to enhance the policies and practices in this critical area of public health. These findings underscore the importance of understanding food/nutrition literacy and developing effective interventions to promote healthy eating habits. By bridging the research–practice divide, this study provides valuable insights for policymakers, practitioners, and researchers to address the gaps and improve food/nutrition literacy in various contexts.

1. Introduction

Food and nutrition literacy are critical concepts that have acquired increasing attention in recent years. Food literacy comprises a variety of connected knowledge, skills, and actions to determine, manage, pick up, prepare, and consume food. It is having the capacity to make decisions that improve one’s health and contribute to a sustainable food system while considering all social, environmental, cultural, economic, and political variables [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ]. Nutrition literacy is the degree to which a person can obtain, process, and grasp basic dietetic information and services to make healthy food choices. It entails understanding nutritional concepts and having the capacity to comprehend, evaluate, and apply nutrition information, i.e., to be aware of the nutrients and their impact on health. It concerns an individual’s ability to gather, comprehend, and apply dietary data from various sources. Nutrition literacy also involves knowing how foods are metabolized, how they affect health, and how to use this knowledge to make good decisions [ 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. According to Krause et al. (2016), food and nutrition literacy are distinct types of health literacy [ 5 ]. The authors claimed that nutrition literacy is the competence to understand fundamental nutritional knowledge, which is a prerequisite for a range of abilities classified as food literacy. The authors recommended the use of food literacy rather than nutrition literacy since it is more inclusive and comprises the knowledge and abilities required for healthy and responsible eating [ 5 ].

The importance of food and nutrition literacy lies in its potential to promote healthy eating habits and prevent chronic diseases such as obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Enhancing individuals’ ability to make informed decisions about their food choices can help reduce the burden of these diseases and improve overall health outcomes [ 10 ]. Despite the growing recognition of the importance of food and nutrition literacy, there is limited research on this topic. Most studies have focused on measuring individuals’ levels of food and nutrition literacy and identifying the factors that influence these levels. However, ongoing discussions on definitions and measurement methods can result in delays in the implementation of interventions. This lack of consensus on the best approach to define and measure food and nutrition literacy has hindered progress in the field and created missed opportunities for intervention implementation. Moreover, while there is some evidence that food and nutrition literacy interventions can be effective in promoting healthy eating habits, more research is needed to identify the most effective approaches for different populations and settings. Overall, there is a need for more research on food and nutrition literacy to improve policies and practices in this critical area of public health.

Food and nutrition literacy has become an increasingly important research area in recent years. Many studies have been published on this topic, covering a range of issues, such as nutrition education, food labeling, and dietary behavior change. It is crucial to evaluate the underlying reasons for this wave in the number of research papers on food and nutrition literacy. By doing so, we can ensure that researchers’ efforts to promote food and nutrition literacy are based on sound scientific evidence and are not merely driven by a trend or the publish-and-perish effect. The evaluation of the reasons beyond the wave in research papers on food and nutrition literacy would not only help us gain a better understanding of the current state of research in this field, but also provide valuable insights into the underlying factors that drive this tendency.

In this study, the Scopus database was used as the first approach to conducting a bibliometric analysis of food and nutrition literacy research. It is crucial to note that the Scopus findings are only a small portion of the overall production on this subject, and that the scientific literature is likely to be much larger. In addition, new research is being published daily. Publication growth over time was analyzed to identify trends and study outlines, the authorship pattern to understand collaboration and communication practices among researchers, and the country’s contribution to spotting the geographic distribution of research activity. Moreover, prolific authors were identified to highlight the most active contributors to the field, the most active countries to highlight the ones that are leading the research in the field, and the preferred journals to realize the dissemination and impact of research output. Finally, the top-cited articles were analyzed to discover the most influential research in the field. In food and nutrition literacy research, it is essential to assess the impact of intervention programs aimed at enhancing individuals’ knowledge and identification of food- and nutrition-related topics. To address this, the original articles developed by the Scopus search were carefully selected, focusing on those that specifically aimed to measure food or nutrition literacy before and after the implementation of an intervention program. To ensure the validity and reliability of the studies, only articles that used previously validated and consolidated tools for measuring food or nutrition literacy were considered. This analysis seeks to determine whether a disparity exists between theoretical discussions and practical measures employed to increase food or nutrition literacy levels. This study aimed to carry out a bibliometric analysis in the field of food and nutrition literacy to assess the current landscape of publications. Specifically, the goal was to define the profile of existing literature and determine whether the focus remains predominantly on theoretical concepts and definitions, or whether publications have progressed to reporting intervention outcomes aimed at improving levels of food and nutrition literacy. By examining the existing literature, this study seeks to identify any gaps or advancements in this area, thereby providing valuable insights for further research and evidence-based practices.

2.1. Data Source and Search Strategy

Bibliometric analysis was performed using the Scopus database as of March 2023. The query used was: (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Nutrition literacy”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“food literacy”) OR TITLE-ABS-KEY (“nutritional literacy”)) to search for relevant articles published in any language. Two erratum and one retracted document types were excluded to avoid double or false counting of documents ( Figure 1 ).

Flow diagram of the search strategy for bibliometric analysis. The query used in the title, abstract, and keywords was: “Nutrition literacy” OR “food literacy” OR “nutritional literacy”.

2.2. Information Extraction

To prevent double counting and retracted papers that can lead to false-positive outcomes, errata materials were omitted from the analysis. A bibliometric analysis was performed for each document. The following tools were used: (i) VOSviewer (version 1.6.19) to create and visualize the bibliometric networks; (ii) Microsoft Excel to compute the frequencies and percentages of the published materials; and (iii) Harzing’s Publish and Perish program to compute the citation metrics. The Endnote 20 citation manager was used to import each citation.

2.3. Search Strategy and Study Selection

The primary source of literature was the one carried out in Scopus and described in the Section 2.1 . A total of 459 English language papers reporting original data on food and nutrition literacy were identified by screening through an Endnote search, which involved searching the PDFs of articles for at least one of the following terms: Critical Nutrition Literacy Instrument (CNLI), Electronic-Nutrition Literacy Tool (e-NutLit), Food Literacy Survey (FLS), Nutrition Literacy Assessment (NLA), Nutrition Literacy Scale (NLS), Short Food Literacy Questionnaire (SFLQ), Food Literacy Scale, or Food Literacy Assessment (FLA). The study designs that sought to enhance a skill domain, such as functional, interactive, and critical, without or in conjunction with a cognitive domain (food/nutrition knowledge, attitude, and food/nutrition information understanding), and where the outcome was assessed using one of the instruments, were considered eligible ( Figure 2 ).

Original papers selection.

Two reviewers (Rita Silva and Paula Silva) independently selected eligible papers based on their abstracts. The abstracts of all articles were reviewed, and articles that evaluated an intervention program aimed at increasing food or nutrition literacy and whose effectiveness was measured using at least one of the aforementioned tools were selected. The entire texts of all publications that could have been pertinent were then obtained and evaluated.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. description of retrieved literature.

In total, 654 documents were retrieved from the Scopus database. Document types included journal articles, review articles, book chapters, conference papers, notes, editorials, letters, conference reviews, short surveys, and books. Most of the documents consisted of original articles, accounting for more than three-quarters of the total publications (502 documents, 76.77%). Review articles accounted for 65 documents (9.94%), while book chapters contributed to 36 documents (5.50%). The remaining document types comprised less than 5% of the total publications. The retrieved documents received a cumulative total of 7249 citations, indicating their impact and influence on the academic community. Furthermore, the h-index of the retrieved documents was 41, providing a measure of the significance and productivity of the research output.

Most retrieved documents were published in English, accounting for 96.18% of the total. Chinese was the second most prevalent language, representing 2.45% of documents. Additionally, a variety of other languages were used, including German, Spanish, Portuguese, Czech, Italian, Korean, Persian, and Turkish. Four documents were published in dual languages, indicating accessibility to a broader audience.

Mapping with the VOSviewer technique of author keywords with minimum occurrences of 10 showed that ones such as health literacy, nutrition, nutrition education, diet, children, food security, food insecurity, obesity, and food were the most encountered author keywords after the exclusion of “nutrition literacy” and “food literacy”, which are the keywords used in the search query ( Figure 3 ). Circles of the same color signify that the papers have a common subject. Specifically, the red cluster (Cluster 1, 9 items) included keywords related to the influence of health literacy on the health-promoting behavior of adolescents with and without obesity. In the green cluster (cluster 2, seven items), the keywords point out studies related to the validation and use of nutrition literacy assessment instruments to measure nutrition literacy. Clusters 3 and 4 and the blue and yellow clusters included six keywords. Cluster 3 reports on the field of food insecurity, food skills, health literacy, and food preparation activities among young adults. Cluster 4 was related more to sustainable food systems and their reorientation towards healthy diets for children. Cluster 5, represented by purple, focuses on exploring the connection between nutrition knowledge, education, and various factors influencing adolescents’ dietary choices and lifestyle habits. Based on this ranking, researchers initially focused on comprehending the influence of health literacy on adolescents’ adoption of health-promoting behaviors. This knowledge can then be used to develop interventions aimed at promoting healthy eating and physical activity, considering the increasing concern surrounding the widespread occurrence of obesity and related chronic diseases among adolescents globally [ 11 ]. As nutrition education and intervention programs have been implemented, researchers have attempted to develop tools to accurately and reliably measure nutrition literacy, which is crucial for evaluating the effectiveness of those programs [ 12 ]. Later, scientific evidence recognized the complex interplay among food insecurity, food skills, health literacy, and sustainable food systems in shaping food choices and health outcomes among young adults. Some papers were then published to understand the broader socioeconomic and environmental determinants of food or nutrition literacy [ 13 ]. Scientific research on the factors that influence adolescents’ food intake and lifestyle habits may be considered relatively less studied than other topics.

Author’s keyword network visualization. Unit of analysis = author keywords; counting method: full counting; minimum number of occurrences of a keyword = 10; cluster size = 5. The size of the circle of a keyword is determined by the number of occurrences. The query used in the title, abstract, and keywords was: “Nutrition literacy” OR “food literacy” OR “nutritional literacy”.

3.2. Growth of Publications

The researcher can track the development and evolution of the study subject over time by looking at documents according to the year of publication. The first paper retrieved by Scopus was published in 1970 in the Journal of Nutrition Education and has the title “Nutritional literacy of high school students” and the authors are Johanna Dwyer, Jacob Feldman, and Jean Mayer. The goal of this first cross-sectional study was to evaluate nutrition instruction and knowledge among high school students in a major city [ 14 ]. The second article retrieved by Scopus was published in 1992. Papers were published every year after 2005 ( Figure 4 ). However, this does not necessarily mean that no scientific documents related to food literacy or nutrition were produced before 1970 or during the gap years. By examining the cited bibliography list of Scopus-retrieved papers and the list of papers that cite them, it is apparent that such documents exist. The reason for the absence of publications during those years could be the fact of researchers did not use the terms “nutrition literacy” and “food literacy”. Studies defining these concepts appeared only in the early 2000s, such as Blitstein et al.’s (2006) [ 6 ] paper on nutrition literacy and Kolasa et al.’s (2001) [ 1 ] paper on food literacy.

Growth of publications. The query used in the title, abstract, and keywords was: “Nutrition literacy” OR “food literacy” OR “nutritional literacy”.

The citation matrix for the retrieved documents per year after 2006 is presented in Table 1 . The year with the most papers produced was 2022, with a total of 160 papers produced. This bibliometric study revealed a noticeable upward trend in the number of publications, particularly after 2018. It can be speculated that this increase is related to non-communicable diseases as primary targets for global disease prevention by the WHO, as shown in the 2016 Global Burden of Disease Study [ 15 ]. Furthermore, an implementation plan was introduced during the 2017 World Health Assembly. This plan aimed to provide guidance to countries to implement the six recommendations outlined by the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity (2016). The recommendations specifically target the obesogenic environment and critical periods throughout the life course, aiming to address the issue of childhood obesity [ 16 ]. The total number of publications published was highest in the last three years (2019–2022); however, due to the short time that had elapsed since publications, those do not correspond to the years with the highest average citation per cited publication. Looking at Table 1 , we must consider that the number of citations per publication was the highest for documents published in 2014, since in 2009, only one document was published and cited. In summary, the topic of food and nutrition literacy has gained significant attention since 2016, driven by mounting concerns regarding health issues associated with diet, such as obesity, diabetes, and heart disease. As individuals become more conscious of the significance of healthy eating, there is a heightened demand for research in the field of food and nutrition literacy. This increased interest and demand can account for the observed upward trend in publications and citations on this subject.

Annual number of publications and citation matrix.

| Year | TP | NPC | TC | C/P | C/CP | h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 4 | 4 | 128 | 32.00 | 32.00 | 4 |

| 2007 | 3 | 2 | 76 | 25.33 | 38.00 | 2 |

| 2008 | 4 | 4 | 158 | 39.50 | 39.50 | 3 |

| 2009 | 1 | 1 | 86 | 86.00 | 86.00 | 1 |

| 2010 | 3 | 3 | 56 | 18.67 | 18.67 | 3 |

| 2011 | 10 | 9 | 545 | 54.50 | 60.56 | 7 |

| 2012 | 6 | 6 | 99 | 16.50 | 16.50 | 5 |

| 2013 | 10 | 10 | 304 | 30.40 | 30.40 | 9 |

| 2014 | 10 | 9 | 755 | 75.50 | 83.89 | 8 |

| 2015 | 24 | 24 | 818 | 34.08 | 34.08 | 14 |

| 2016 | 41 | 37 | 571 | 13.93 | 15.43 | 11 |

| 2017 | 36 | 32 | 772 | 21.44 | 24.13 | 14 |

| 2018 | 49 | 47 | 743 | 15.16 | 15.81 | 16 |

| 2019 | 61 | 56 | 718 | 11.77 | 12.82 | 15 |

| 2020 | 88 | 74 | 631 | 7.17 | 8.53 | 14 |

| 2021 | 110 | 88 | 459 | 4.17 | 5.22 | 10 |

| 2022 | 160 | 85 | 195 | 1.22 | 2.29 | 6 |

| 2023 | 27 | 4 | 5 | 0.19 | 1.25 | 1 |