You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

Gr. 12 HISTORY REVISION: THE BLACK POWER MOVEMENT

REVISION: THE BLACK POWER MOVEMENT

Do you have an educational app, video, ebook, course or eResource?

Contribute to the Western Cape Education Department's ePortal to make a difference.

Home Contact us Terms of Use Privacy Policy Western Cape Government © 2024. All rights reserved.

National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Plan Your Visit

- Group Visits

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Accessibility Options

- Sweet Home Café

- Museum Store

- Museum Maps

- Our Mobile App

- Search the Collection

- Initiatives

- Museum Centers

- Publications

- Digital Resource Guide

- The Searchable Museum

- Exhibitions

- Freedmen's Bureau Search Portal

- Early Childhood

- Talking About Race

- Digital Learning

- Strategic Partnerships

- Ways to Give

- Internships & Fellowships

- Today at the Museum

- Upcoming Events

- Ongoing Tours & Activities

- Past Events

- Host an Event at NMAAHC

- About the Museum

- The Building

- Meet Our Curators

- Founding Donors

- Corporate Leadership Councils

- NMAAHC Annual Reports

The Foundations of Black Power

Black power emphasized black self-reliance and self-determination more than integration. Proponents believed African Americans should secure their human rights by creating political and cultural organizations that served their interests.

They insisted that African Americans should have power over their own schools, businesses, community services and local government. They focused on combating centuries of humiliation by demonstrating self-respect and racial pride as well as celebrating the cultural accomplishments of black people around the world. The black power movement frightened most of white America and unsettled scores of black Americans.

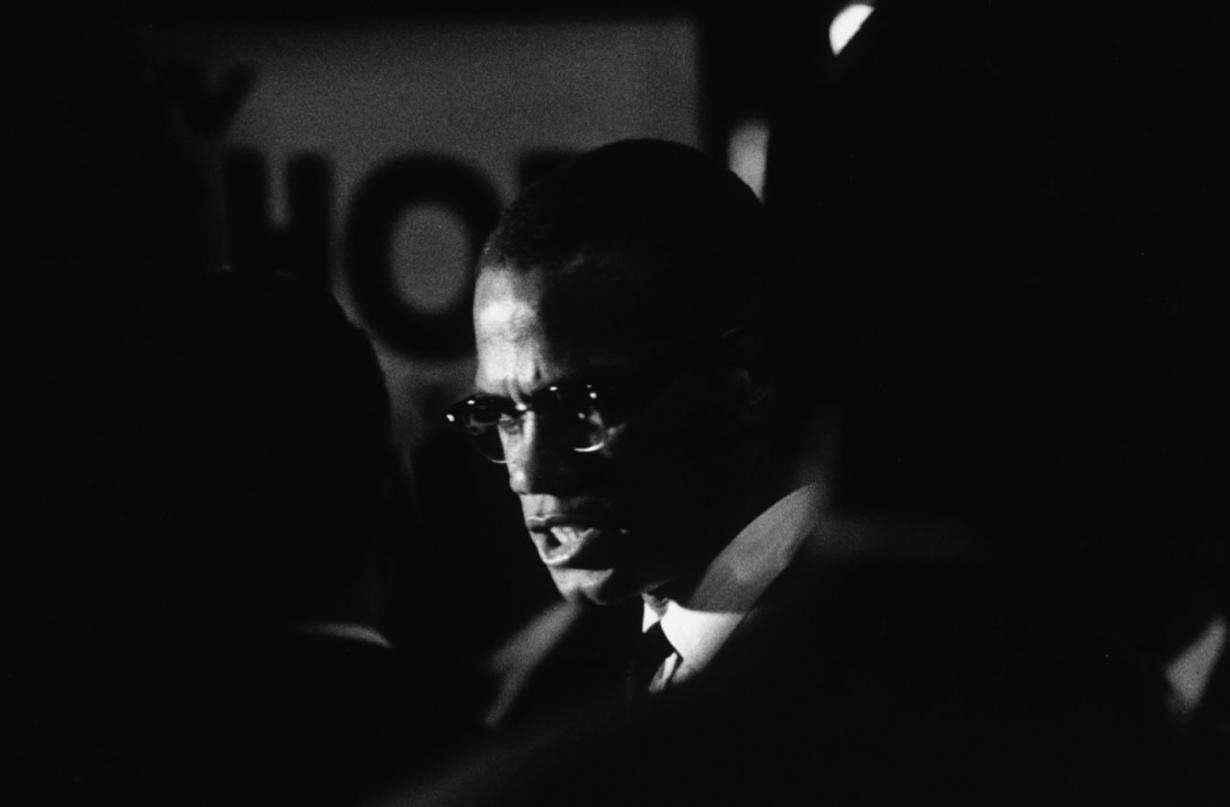

Malcolm X The inspiration behind much of the black power movement, Malcolm X’s intellect, historical analysis, and powerful speeches impressed friend and foe alike. The primary spokesman for the Nation of Islam until 1964, he traveled to Mecca that year and returned more optimistic about social change. He saw the African American freedom movement as part of an international struggle for human rights and anti-colonialism. After his assassination in 1965, his memory continued to inspire the rising tide of black power.

Malcolm X speaking in front of the 369th Regiment Armory, 1964.

More than any other person, Malcolm X was responsible for the growing consciousness and new militancy of black people. Julius Lester 1968

Malcolm X’s expression of black pride and self-determination continued to resonate with and engage many African Americans long after his death in February 1965. For example, listening to recordings of his speeches inspired African American soldiers to organize GIs United Against the War in Vietnam in 1969.

This 16mm film is a short documentary made by Madeline Anderson for National Education Television's Black Journal television program to commemorate the four year anniversary of the assassination of Malcolm X.

Stokely Carmichael Stokely Carmichael set a new tone for the black freedom movement when he demanded “black power” in 1966. Drawing on long traditions of racial pride and black nationalism, black power advocates enlarged and enhanced the accomplishments and tactics of the civil rights movement. Rather than settle for legal rights and integration into white society, they demanded the cultural, political, and economic power to strengthen black communities so they could determine their own futures.

Martin Luther King Jr.'s former associate Stokely Carmichael speaks at civil rights rally in Washington, April 4, 1970.

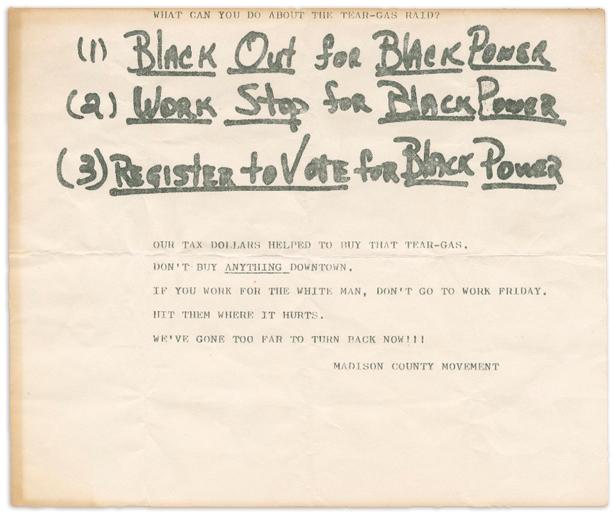

Black Power Intertwines with Civil Rights Organizers made no distinctions between black power and nonviolent civil rights boycotts in Madison County, Mississippi, 1966.

Flyer for the Madison County Movement, founded 1963.

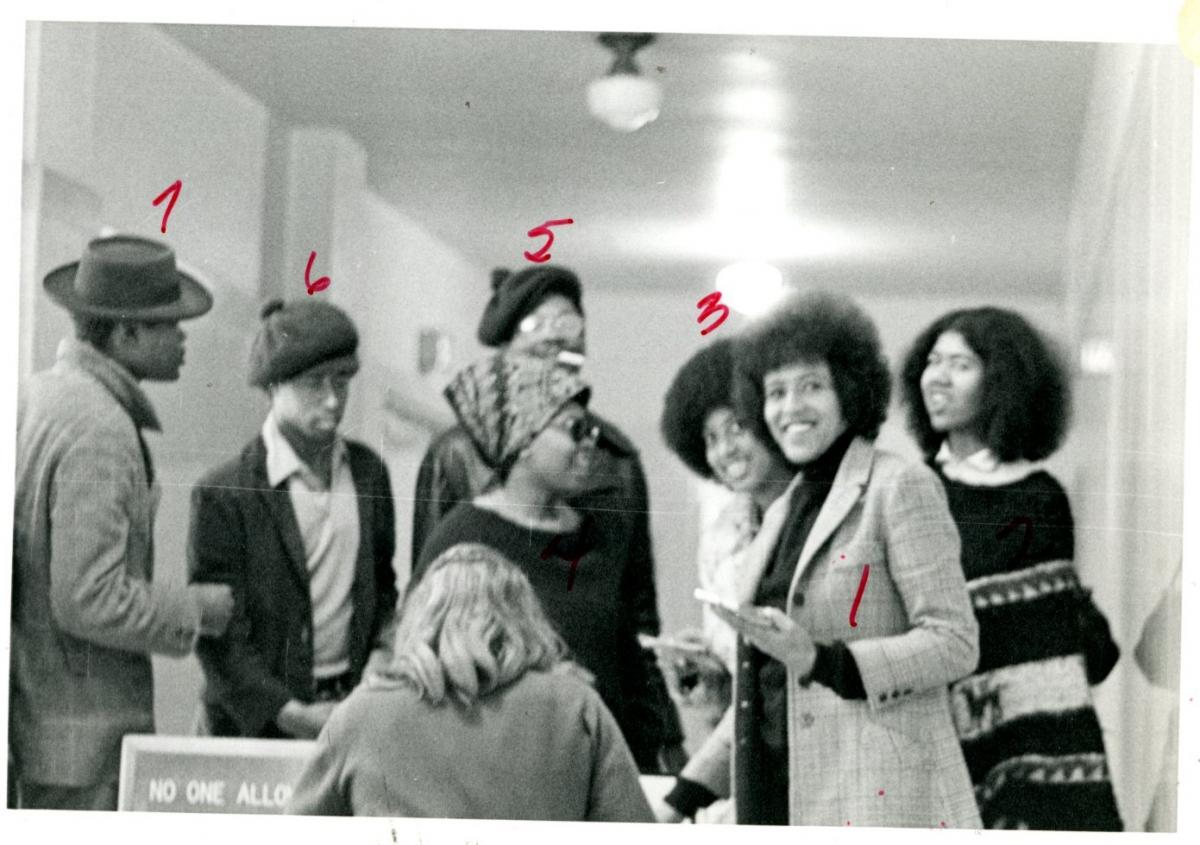

SNCC Supports Black Power SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, created in 1960, destroyed “the psychological shackles which had kept black southerners in physical and mental peonage,” according to its chairman, Julian Bond.

Julian Bond standing and writing as a young African American boy watches closely, 1976.

Protest, Teaneck, New Jersey Building on the successes of the civil rights movement in dismantling segregation, the black power movement sought a further transformation of American society and culture.

A woman sits on a bench outside the Black Panther office in Harlem circa 1970 in New York City. Pictured in the window are Panther founders Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale.

Black Power Around the World Revolutions in other nations inspired advocates of black power. The African revolutions against European colonialism in the 1950s and 1960s were exciting examples of success. Wars of national liberation in Southeast Asia and Northern Africa offered still more encouragement. Stokely Carmichael’s five-month world speaking tour in 1967 made black power a key to revolutionary language in places like Algeria, Cuba and Vietnam.

Sharpeville massacre: Dead and wounded rioters lie in the streets of Sharpeville, South Africa, following an anti-apartheid demonstration organized by the Pan-Africanist Congress which called upon Africans to leave their passes at home, March 21, 1960. The South African police opened fire on the crowd, killing 69 people and injuring 180 others.

Protesting Apartheid, Cape Town, South Africa In 1972 African Americans began annual celebrations of African Liberation Day to commemorate and support liberation movements in Africa.

This flyer announces a protest against apartheid in South Africa, 1977. Pan African Students Organization in the Americas (1960 - 1977) and Youth Against War & Fascism , founded 1961.

“Free All Political Prisoners!” Critics vilified black power organizations as separatist groups or street gangs. These critics ignored the movement’s political activism, cultural innovations and social programs. Of nearly 300 authorized FBI operations against black nationalist groups, more than 230 targeted the Black Panthers. This forced organizations to spend time, money, and effort toward legal defense rather than social programs.

A round, yellow pinback button with a photographic portrait of Angela Davis in the center, 1970-72.

The War on Black Power Between 1956 and 1971, the FBI and other government agencies waged a war against dissidents, especially African Americans and anti-war advocates. The FBI’s Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO) targeted Martin Luther King Jr., the Black Panthers, Us and other black groups. Activities included spying, wiretapping phones, making criminal charges on flimsy evidence, spreading rumors and even assassinating prominent individuals, like Black Panther Fred Hampton. By the mid-1970s, these actions helped to weaken or destroy many of the groups associated with the black power movement.

The Black Panther Party, without question, represents the greatest threat to the internal security of the country. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover 1969

Olympic Medalists Giving Black Power Sign, 1968 Tommie Smith (center) and John Carlos (right) gold and bronze medalists in the 200-meter run at the 1968 Olympic Games. During the national anthem, they stand with heads lowered and black-gloved fists raised in the black power salute to protest against unfair treatment of blacks in the United States. Australian Peter Norman is the silver medalist (left).

Subtitle here for the credits modal.

The Black Power Movement: Understanding Its Origins, Leaders, and Legacy

Politicians love to quote Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous line about the long arc of the moral universe slowly bending toward justice. But social justice movements have long been accelerated by radicals and activists who have tried to force that arc to bend faster. That was the case for the Black power movement, an outgrowth of the civil rights movement that emerged in the 1960s with calls to reject slow-moving integration efforts and embrace self-determination. The movement called for Black Americans to create their own cultural institutions, take pride in their heritage, and become economically independent. Its legacy is still felt today in the work of the movement for Black lives. Here’s what to know about how the Black power movement started and what it stood for.

What were the origins of the movement?

It started with a march. Four years after James Meredith became the first Black student to enroll at the University of Mississippi, he embarked on a solo walk from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi. Meredith’s “March Against Fear” was a protest against the fear instilled in Black Americans who attempted to register to vote, and the overall culture of fear that was part of day-to-day life. On June 5, 1966, he began his 220-mile trek, equipped with nothing but a helmet and walking stick . On his second day, June 6, Meredith crossed the Mississippi border (by this point he’d been joined by a small number of supporters, reporters, and photographers). That’s where a white man, Aubrey James Norvell, shot Meredith in the head, neck, and back. Meredith survived but was unable to continue marching.

In response, civil rights leaders including King and Stokely Carmichael, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), came together in Mississippi to continue Meredith’s march and push for voting rights. Carmichael, who King had considered to be one of the most promising leaders of the civil rights movement, had gone from embracing nonviolent protests in the early '60s to pushing for a more radical approach for change. "[Dr. King] only made one fallacious assumption: In order for nonviolence to work, your opponent has to have a conscience. The United States has no conscience," said Carmichael.

Carmichael was arrested when the march reached Greenwood, Mississippi, and after his release he led a crowd in a chant , at a rally , “We want Black power!” Although the slogan “Black power for Black people” was used by Alabama’s Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO) the year before, Carmichael’s use of the phrase, on June 16, 1966, is what drew national attention to the concept.

Who are some of the movement’s prominent leaders?

Malcolm X was assassinated before the rise of the Black power movement, but his life and teachings laid the groundwork for it and served as one of the movement’s greatest inspirations . The movement drew on Malcolm X’s declarations of Black pride and his understanding that the freedom movement for Black Americans was intertwined with the fight for global human rights and an anti-colonial future.

Carmichael, a Trinidad-born New Yorker (later known as Kwame Ture), and who popularized the phrase "Black power,” was a key leader of the movement. Carmichael was inspired to get involved with the civil rights movement after seeing Black protesters hold sit-ins at segregated lunch counters across the South. During his time at Howard University, he joined SNCC and became a Freedom Rider , joining other college students in challenging segregation laws as they traveled through the South.

Eventually, after being arrested more than 32 times and witnessing peaceful protesters get met with violence, Carmichael moved away from the passive resistance method of fighting for freedom. “I think Dr. King is a great man, full of compassion. He is full of mercy and he is very patient. He is a man who could accept the uncivilized behavior of white Americans, and their unceasing taunts; and still have in his heart forgiveness,” Carmichael once said , as quoted in The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975 documentary. “Unfortunately, I am from a younger generation. I am not as patient as Dr. King, nor am I as merciful as Dr. King. And their unwillingness to deal with someone like Dr. King just means they have to deal with this younger generation.”

Activist, author, and scholar Angela Davis , one of the most iconic faces of the movement, later told the Nation , "The movement was a response to what were perceived as the limitations of the civil rights movement.… Although Black individuals have entered economic, social, and political hierarchies, the overwhelming number of Black people are subject to economic, educational, and carceral racism to a far greater extent than during the pre-civil rights era.”

What did the movement stand for?

Dr. King believed “Black power” meant "different things to different people,” and he was right. After Carmichael uttered the slogan, Black power groups began forming across the country, putting forth different ideas of what the phrase meant. Carmichael once said , “When you talk about Black power, you talk about bringing this country to its knees any time it messes with the Black man…. Any white man in this country knows about power. He knows what white power is, and he ought to know what Black power is.”

Some Black civil rights leaders opposed the slogan. Dr. King, for example, believed it to be “essentially an emotional concept” and worried that it carried “connotations of violence and separatism.” Many white people did, in fact, interpret “Black power” as meaning a violently anti-white movement. In 2020, during Congressman John Lewis’s funeral, former president Bill Clinton said , “There were two or three years there where the movement went a little too far toward Stokely, but in the end, John Lewis prevailed.” By “Stokely,” he meant the Black power movement.

According to the National Museum of African American History & Culture (NMAAHC), the Black power movement aimed to “emphasize Black self-reliance and self-determination more than integration,” and supporters of the movement believed “African Americans should secure their human rights by creating political and cultural organizations that served their interests.” The Black power movement sought to give Black people control of their own lives by empowering them culturally, politically, and economically. At the same time, it instilled a sense of pride in Black people who began to further embrace Black art, history , and beauty .

Although Dr. King didn’t publicly support the movement, according to the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University, in November 1966, he told his staff that Black power “was born from the wombs of despair and disappointment. Black power is a cry of pain. It is, in fact, a reaction to the failure of white power to deliver the promises and to do it in a hurry…. The cry of Black power is really a cry of hurt.”

How did “Black power” relate to the civil rights movement and Black Panther Party?

At its core, the Black power movement was a movement for Black liberation . What made the Black power movement different from the civil rights movement of the early 1960s, and frightening to white people, was that it embraced forms of self-defense . In fact, the full name of the Black Panther Party was “the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense.”

Huey Newton [R], founder of the Black Panther Party, sits with Bobby Seale at party headquarters in San Francisco.

The Black Panthers were founded in 1966 by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, two students in Oakland, California. Like Carmichael, Newton and Seale couldn’t stand the brutality Black people faced at the hands of police officers and a legal system that empowered those officers while oppressing Black citizens. The Black power movement came to be as a result of the work and impact of the civil rights movement, but the Black Panther party, which also strayed from the idea of integration, was an extension of the Black power movement. According to the NMAAHC , it was the “most influential militant” Black power organization of the era.

The SNCC and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) embraced militant separatism in alignment with the Black power movement, while the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) opposed it. Subsequently, the movement was divided, and in the late 1960s and '70s, the slogan became synonymous with Black militant organizations. Peniel Joseph , founding director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at the University of Austin Texas’s LBJ School of Public Affairs, told NPR that although the movement is “remembered by the images of gun-toting black urban militants, most notably the Black Panther Party...it's really a movement that overtly criticized white supremacy.”

“You ask me whether I approve of violence? That just doesn’t make any sense at all," Angela Davis said in The Black Power Mixtape . “Whether I approve of guns? I grew up in Birmingham, Alabama. Some very, very good friends of mine were killed by bombs – bombs that were planted by racists. I remember, from the time I was very small, the sound of bombs exploding across the street and the house shaking. That’s why,” Davis explained further, "when someone asks me about violence, I find it incredible because it means the person asking that question has absolutely no idea what Black people have gone through and experienced in this country from the time the first Black person was kidnapped from the shores of Africa.”

What impact did the movement have on U.S. history?

The Black power movement empowered generations of Black organizers and leaders, giving them new figures to look up to and a new way to think of systemic racism in the U.S. The raised fist that became a symbol of Black power in the 1960s is one of the main symbols of today’s Black Lives Matter movement .

“When we think about its impact on democratic institutions, it's really on multiple levels,” Joseph told NPR . “On one level, politically, the first generation of African American elected officials, they owe their standing to both the civil rights and voting rights act of '64 and '65. But to actually get elected in places like Gary, Indiana, in 1967, it required Black power activism to help them build up new Black, urban political machines. So its impact is really, really profound.”

Want more from Teen Vogue ? Check this out: The Black Radical Tradition in the South Is Nothing to Sneer At

Stay up-to-date with the politics team. Sign up for the Teen Vogue Take!

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

How the Black Power Movement Influenced the Civil Rights Movement

By: Sarah Pruitt

Updated: July 27, 2023 | Original: February 20, 2020

By 1966, the civil rights movement had been gaining momentum for more than a decade, as thousands of African Americans embraced a strategy of nonviolent protest against racial segregation and demanded equal rights under the law.

But for an increasing number of African Americans, particularly young Black men and women, that strategy did not go far enough. Protesting segregation, they believed, failed to adequately address the poverty and powerlessness that generations of systemic discrimination and racism had imposed on so many Black Americans.

Inspired by the principles of racial pride, autonomy and self-determination expressed by Malcolm X (whose assassination in 1965 had brought even more attention to his ideas), as well as liberation movements in Africa, Asia and Latin America, the Black Power movement that flourished in the late 1960s and ‘70s argued that Black Americans should focus on creating economic, social and political power of their own, rather than seek integration into white-dominated society.

Crucially, Black Power advocates, particularly more militant groups like the Black Panther Party, did not discount the use of violence, but embraced Malcolm X’s challenge to pursue freedom, equality and justice “by any means necessary.”

The March Against Fear - June 1966

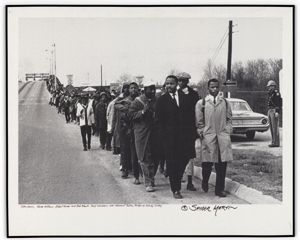

The emergence of Black Power as a parallel force alongside the mainstream civil rights movement occurred during the March Against Fear, a voting rights march in Mississippi in June 1966. The march originally began as a solo effort by James Meredith, who had become the first African American to attend the University of Mississippi, a.k.a. Ole Miss, in 1962. He had set out in early June to walk from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi, a distance of more than 200 miles, to promote Black voter registration and protest ongoing discrimination in his home state.

But after a white gunman shot and wounded Meredith on a rural road in Mississippi, three major civil rights leaders— Martin Luther King, Jr. of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Stokely Carmichael of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and Floyd McKissick of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) decided to continue the March Against Fear in his name.

In the days to come, Carmichael, McKissick and fellow marchers were harassed by onlookers and arrested by local law enforcement while walking through Mississippi. Speaking at a rally of supporters in Greenwood, Mississippi, on June 16, Carmichael (who had been released from jail that day) began leading the crowd in a chant of “We want Black Power!” The refrain stood in sharp contrast to many civil rights protests, where demonstrators commonly chanted “We want freedom!”

The Campus Walkout That Led to America’s First Black Studies Department

The 1968 strike was the longest by college students in American history. It helped usher in profound changes in higher education.

The 1969 Raid That Killed Black Panther Leader Fred Hampton

Details around the 1969 police shooting of Hampton and other Black Panther members took decades to come to light.

Civil Rights Movement

Jim Crow Laws During Reconstruction, Black people took on leadership roles like never before. They held public office and sought legislative changes for equality and the right to vote. In 1868, the 14th Amendment to the Constitution gave Black people equal protection under the law. In 1870, the 15th Amendment granted Black American men the […]

Stokely Carmichael’s Role in Black Power

Though the author Richard Wright had written a book titled Black Power in 1954, and the phrase had been used among other Black activists before, Stokely Carmichael was the first to use it as a political slogan in such a public way. As biographer Peniel E. Joseph writes in Stokely: A Life , the events in Mississippi “catapulted Stokely into the political space last occupied by Malcolm X,” as he went on TV news shows, was profiled in Ebony and written up in the New York Times under the headline “Black Power Prophet.”

Carmichael’s growing prominence put him at odds with King, who acknowledged the frustration among many African Americans with the slow pace of change but didn’t see violence and separatism as a viable path forward. With the country mired in the Vietnam War , (a war both Carmichael and King spoke out against) and the civil rights movement King had championed losing momentum, the message of the Black Power movement caught on with an increasing number of Black Americans.

Black Power Movement Growth—and Backlash

King and Carmichael renewed their alliance in early 1968, as King was planning his Poor People’s Campaign, which aimed to bring thousands of protesters to Washington, D.C., to call for an end to poverty. But in April 1968, King was assassinated in Memphis while in town to support a strike by the city’s sanitation workers as part of that campaign.

In the aftermath of King’s murder, a mass outpouring of grief and anger led to riots in more than 100 U.S. cities . Later that year, one of the most visible Black Power demonstrations took place at the Summer Olympics in Mexico City, where Black athletes John Carlos and Tommie Smith raised black-gloved fists in the air on the medal podium.

By 1970, Carmichael (who later changed his name to Kwame Ture) had moved to Africa, and SNCC had been supplanted at the forefront of the Black Power movement by more militant groups, such as the Black Panther Party , the US Organization, the Republic of New Africa and others, who saw themselves as the heirs to Malcolm X’s revolutionary philosophy. Black Panther chapters began operating in a number of cities nationwide, where they advocated a 10-point program of socialist revolution (backed by armed self-defense). The group’s more practical efforts focused on building up the Black community through social programs (including free breakfasts for school children ).

Many in mainstream white society viewed the Black Panthers and other Black Power groups negatively, dismissing them as violent, anti-white and anti-law enforcement. Like King and other civil rights activists before them, the Black Panthers became targets of the FBI’s counterintelligence program, or COINTELPRO, which weakened the group considerably by the mid-1970s through such tactics as spying, wiretapping, flimsy criminal charges and even assassination .

Legacy of Black Power

Even after the Black Power movement’s decline in the late 1970s, its impact would continue to be felt for generations to come. With its emphasis on Black racial identity, pride and self-determination, Black Power influenced everything from popular culture to education to politics, while the movement’s challenge to structural inequalities inspired other groups (such as Chicanos, Native Americans, Asian Americans and LGBTQ people) to pursue their own goals of overcoming discrimination to achieve equal rights.

The legacies of both the Black Power and civil rights movements live on in the Black Lives Matter movement . Though Black Lives Matter focuses more specifically on criminal justice reform, it channels the spirit of earlier movements in its efforts to combat systemic racism and the social, economic and political injustices that continue to affect Black Americans.

HISTORY Vault: Black History

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Black Power

Although African American writers and politicians used the term “Black Power” for years, the expression first entered the lexicon of the civil rights movement during the Meredith March Against Fear in the summer of 1966. Martin Luther King, Jr., believed that Black Power was “essentially an emotional concept” that meant “different things to different people,” but he worried that the slogan carried “connotations of violence and separatism” and opposed its use (King, 32; King, 14 October 1966). The controversy over Black Power reflected and perpetuated a split in the civil rights movement between organizations that maintained that nonviolent methods were the only way to achieve civil rights goals and those organizations that had become frustrated and were ready to adopt violence and black separatism.

On 16 June 1966, while completing the march begun by James Meredith , Stokely Carmichael of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) rallied a crowd in Greenwood, Mississippi, with the cry, “We want Black Power!” Although SNCC members had used the term during informal conversations, this was the first time Black Power was used as a public slogan. Asked later what he meant by the term, Carmichael said, “When you talk about black power you talk about bringing this country to its knees any time it messes with the black man … any white man in this country knows about power. He knows what white power is and he ought to know what black power is” (“Negro Leaders on ‘Meet the Press’”). In the ensuing weeks, both SNCC and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) repudiated nonviolence and embraced militant separatism with Black Power as their objective.

Although King believed that “the slogan was an unwise choice,” he attempted to transform its meaning, writing that although “the Negro is powerless,” he should seek “to amass political and economic power to reach his legitimate goals” (King, October 1966; King, 14 October 1966). King believed that “America must be made a nation in which its multi-racial people are partners in power” (King, 14 October 1966). Carmichael, on the other hand, believed that black people had to first “close ranks” in solidarity with each other before they could join a multiracial society (Carmichael, 44).

Although King was hesitant to criticize Black Power openly, he told his staff on 14 November 1966 that Black Power “was born from the wombs of despair and disappointment. Black Power is a cry of pain. It is in fact a reaction to the failure of White Power to deliver the promises and to do it in a hurry … The cry of Black Power is really a cry of hurt” (King, 14 November 1966).

As the Southern Christian Leadership Conference , the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People , and other civil rights organizations rejected SNCC and CORE’s adoption of Black Power, the movement became fractured. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Black Power became the rallying call of black nationalists and revolutionary armed movements like the Black Panther Party, and King’s interpretation of the slogan faded into obscurity.

“Black Power for Whom?” Christian Century (20 July 1966): 903–904.

Branch, At Canaan’s Edge , 2006.

Carmichael and Hamilton, Black Power , 1967.

Carson, In Struggle , 1981.

King, Address at SCLC staff retreat, 14 November 1966, MLKJP-GAMK .

King, “It Is Not Enough to Condemn Black Power,” October 1966, MLKJP-GAMK .

King, Statement on Black Power, 14 October 1966, TMAC-GA .

King, Where Do We Go from Here , 1967.

“Negro Leaders on ‘Meet the Press,’” 89th Cong., 2d sess., Congressional Record 112 (29 August 1966): S 21095–21102.

- Browse by Topic

- Browse by Partner

- Exhibitions

- Primary Source Sets

The Black Power Movement

The Black Power Movement of the 1960s and 1970s was a political and social movement whose advocates believed in racial pride, self-sufficiency, and equality for all people of Black and African descent. Credited with first articulating “Black Power” in 1966, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee leader Stokely Carmichael represented a generation of black activists who participated in both Civil Rights and the Black Power movements. By the mid 1960s, many of them no longer saw nonviolent protests as a viable means of combatting racism. New organizations, such as the Black Panther Party, the Black Women’s United Front, and the Nation of Islam, developed new cultural, political, and economic programs and grew memberships that reflected this shift. Desegregation was insufficient—only through the deconstruction of white power structures could a space be made for a black political voice to give rise to collective black power. Because of these beliefs, the movement is often represented as violent, anti-white, and anti-law enforcement. This primary source set addresses these representations through artifacts from the era, such as sermons, photographs, drawings, FBI investigations, and political manifestos.

- Lakisha Odlum, New York City Department of Education

Time Period

- Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

- Social Movements

- African Americans

Cite this set

- Additional Resources

- Teaching Guide

Related Primary Source Sets

These sets were created and reviewed by teachers. Explore resources and ideas for Using DPLA's Primary Source Sets in your classroom.

To give feedback, contact us at [email protected] . You can also view resources for National History Day .

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access Options

- Why Publish with JAH?

- About Journal of American History

- About the Organization of American Historians

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous

The Black Power Movement: A State of the Field

Peniel E. Joseph is a professor of history at Tufts University.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Peniel E. Joseph, The Black Power Movement: A State of the Field, Journal of American History , Volume 96, Issue 3, December 2009, Pages 751–776, https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/96.3.751

- Permissions Icon Permissions

“By all rights, there no longer should be much question about the meaning—at least the intended meaning—of Black Power,” the journalist Charles Sutton observed in January 1967. “Between the speeches and writings of Stokely Carmichael, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee ( sncc ),” Sutton continued, “the explanations of Floyd McKissick, director of the Congress of Racial Equality ( core ), and the writings of more than a score of scholars and commentators, the slogan and its various assumptions have been fairly thoroughly examined.” 1

Clearly Sutton was wrong. Despite efforts to define it both then and today, “black power” exists in the American imagination through a series of iconic, yet fleeting images—ranging from gun-toting Black Panthers to black-gloved sprinters at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics—that powerfully evoke the era's confounding mixture of triumph and tragedy. Indeed, the iconography of Stokely Carmichael in Greenwood, Mississippi, Black Panthers marching outside an Oakland, California, courthouse, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation's wanted poster for Angela Davis serves as a kind of visual shorthand to understanding the history of the era, but such images tell us very little about the movement that birthed them.

Organization of American Historians members

Personal account.

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Short-term Access

To purchase short-term access, please sign in to your personal account above.

Don't already have a personal account? Register

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| December 2016 | 12 |

| January 2017 | 32 |

| February 2017 | 47 |

| March 2017 | 115 |

| April 2017 | 130 |

| May 2017 | 131 |

| June 2017 | 19 |

| July 2017 | 11 |

| August 2017 | 17 |

| September 2017 | 20 |

| October 2017 | 71 |

| November 2017 | 67 |

| December 2017 | 82 |

| January 2018 | 153 |

| February 2018 | 65 |

| March 2018 | 48 |

| April 2018 | 119 |

| May 2018 | 69 |

| June 2018 | 75 |

| July 2018 | 126 |

| August 2018 | 33 |

| September 2018 | 43 |

| October 2018 | 84 |

| November 2018 | 100 |

| December 2018 | 44 |

| January 2019 | 49 |

| February 2019 | 58 |

| March 2019 | 73 |

| April 2019 | 148 |

| May 2019 | 94 |

| June 2019 | 41 |

| July 2019 | 33 |

| August 2019 | 35 |

| September 2019 | 35 |

| October 2019 | 114 |

| November 2019 | 74 |

| December 2019 | 78 |

| January 2020 | 57 |

| February 2020 | 198 |

| March 2020 | 158 |

| April 2020 | 356 |

| May 2020 | 36 |

| June 2020 | 40 |

| July 2020 | 23 |

| August 2020 | 16 |

| September 2020 | 46 |

| October 2020 | 56 |

| November 2020 | 84 |

| December 2020 | 82 |

| January 2021 | 73 |

| February 2021 | 113 |

| March 2021 | 96 |

| April 2021 | 122 |

| May 2021 | 101 |

| June 2021 | 32 |

| July 2021 | 15 |

| August 2021 | 38 |

| September 2021 | 81 |

| October 2021 | 78 |

| November 2021 | 87 |

| December 2021 | 100 |

| January 2022 | 86 |

| February 2022 | 61 |

| March 2022 | 94 |

| April 2022 | 97 |

| May 2022 | 73 |

| June 2022 | 36 |

| July 2022 | 21 |

| August 2022 | 31 |

| September 2022 | 57 |

| October 2022 | 111 |

| November 2022 | 114 |

| December 2022 | 55 |

| January 2023 | 103 |

| February 2023 | 79 |

| March 2023 | 104 |

| April 2023 | 120 |

| May 2023 | 100 |

| June 2023 | 38 |

| July 2023 | 10 |

| August 2023 | 11 |

| September 2023 | 54 |

| October 2023 | 95 |

| November 2023 | 95 |

| December 2023 | 71 |

| January 2024 | 54 |

| February 2024 | 94 |

| March 2024 | 69 |

| April 2024 | 125 |

| May 2024 | 82 |

| June 2024 | 28 |

| July 2024 | 26 |

| August 2024 | 10 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Process - a blog for american history

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1945-2314

- Print ISSN 0021-8723

- Copyright © 2024 Organization of American Historians

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

African American Heritage

Black Power

Black Power began as revolutionary movement in the 1960s and 1970s. It emphasized racial pride, economic empowerment, and the creation of political and cultural institutions. During this era, there was a rise in the demand for Black history courses, a greater embrace of African culture, and a spread of raw artistic expression displaying the realities of African Americans.

The term "Black Power" has various origins. Its roots can be traced to author Richard Wright’s non-fiction work Black Power , published in 1954. In 1965, the Lowndes County [Alabama] Freedom Organization (LCFO) used the slogan “Black Power for Black People” for its political candidates. The next year saw Black Power enter the mainstream. During the Meredith March against Fear in Mississippi, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) Chairman Stokely Carmichael rallied marchers by chanting “we want Black Power.”

This portal highlights records of Federal agencies and collections that related to the Black Power Movement of the 1960s and 1970s. The selected records contain information on various organizations, including the Nation of Islam (NOI), Deacons for Defense and Justice , and the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense (BPP). It also includes records on several individuals, including Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, Elaine Brown, Angela Davis, Fred Hampton, Amiri Baraka, and Shirley Chisholm. This portal is not meant to be exhaustive, but to provide guidance to researchers interested in the Black Power Movement and its relation to the Federal government.

The records in this guide were created by Federal agencies, therefore, the topics included had some sort of interaction with the United States Government. This subject guide includes textual and electronic records, photographs, moving images, audio recordings, and artifacts. Records can be found at the National Archives at College Park, as well as various presidential libraries and regional archives throughout the country.

A Note on Restrictions and the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)

Due to the type of possible content found in series related to Black Power, there may be restrictions associated with access and the use of these records. Several series in RG 60 - Department of Justice (DOJ) and RG 65 - Records of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) may need to be screened for FOIA (b)(1) National Security, FOIA (b)(6) Personal Information, and/or FOIA (b)(7) Law Enforcement prior to public release . Researchers interested in records that contain FOIA restrictions, should consult our Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) page.

Black Arts Movement

Black Panther Party

Congressional Black Caucus

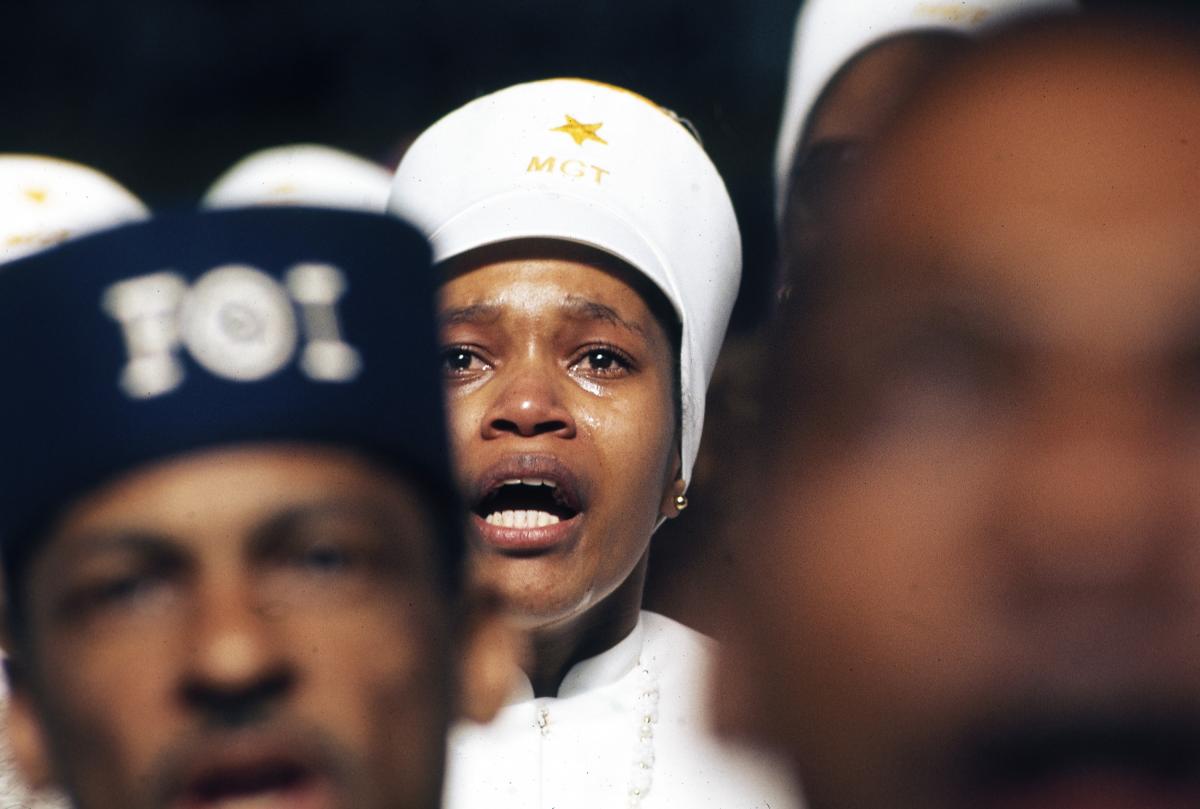

Nation of Islam

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

Women in Black Power

Rediscovering Black History: Blogs on Black Power

National Museum of African American History and Culture: The Foundations of Black Power

Library of Congress, American Folklife Center: Black Power Collections and Repositories

Digital Public Library of America: The Black Power Movement

Columbia University: Malcolm X Project Records, 1968-2008

Revolutionary Movements Then and Now: Black Power and Black Lives Matter, Oct 19, 2016

The people and the police, sep 8, 2016.

Black Power Movement in America Essay (Critical Writing)

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

In America, the beginning of the 1960s was characterized by a number of political and civil movements that were aimed at providing the Black people with rights, freedoms, and opportunities. Regarding the thoughts developed by Malcolm X and Mr. King and the outcomes of their murders, many people did not want to accept the fact that a Black man should not have the rights to power.

The fact that a Black man was deprived of power made people believe that they deserved that right and that they had all possibilities to achieve power and use it as they wished. Black Americans were constantly oppressed, and protests and revolutions turned out to be the only chance to change the situation. Though many Whites admitted that the Blacks promoted hate as the only weapon to demonstrate their intentions ( Eyes on the Prize ), the participants refused that idea underlining that the only strong desire they have is “to live with hope and human dignity that existence without them is impossible” (Newton 5).

The Black Power movement helped to provide people with a sense of racial pride. People had not to be afraid of the color of their skin. All they had to do was to comprehend that the white color is not better than the black color, and there was no person, who could give a clear explanation of why racial diversity should be developed in favor of the Whites. There were a number of attempts to prove the worth of the black nation, and the creation of the Black Panther Party was one of the brightest achievements in the middle of the 1960s.

Huey Newton and Bobby Seale were the founders of the party when they came to the conclusion that there was no other way to deal with white shotguns that spread fear among ordinary black citizens and the instability that deprived people of hope. The idea to create a new political party that could be legally approved was based on casual discussions and conversations (Newton 111). People were in need of something more than the white rooster that represented the Democratic Party, and the elephant that represented the Republican Party.

Now, it was a black cat that spoke for all Black communities ( Eyes on the Prize ). The ideas offered by the Black Panther Party were impressive. It was not enough for them to ask for freedoms, education, employment, etc. It was necessary to prove that the Black community was not worse for the communities organized by the white people, and certain systematic changes were necessary for America.

A ten-point program was developed by the representatives of the Black Panther Party within the frames of which the main ideas and intentions of the Black community were identified. One of the most interesting ideas was the necessity to deal with police brutality and murders of Black people (Newton 120). The organization of self-defense groups was the decision that proved the importance of patrolling.

According to the Second Amendment to the US Constitution, people had the right to bear arms, and Newton used that opportunity to help the Black people protect themselves against the police as “it was ridiculous to report the police to the police, but… by raising encounters to a higher level, by patrolling the police with arms, we would see a change in their behavior” (120). These were the first steps that helped to realize that the Black people could do a lot of things to improve their lives in case they did everything on their own.

Works Cited

Eyes on the Prize . Ex. Prod. Henry Hampton. Boston: Blackside, 1987-1990. Web.

Newton, Huey, P. Revolutionary Suicide , New York: Writers and Readers Publishing, 1995. Print.

- HIV/AIDS Activism in "How to Survive a Plague"

- The Popularity of Subcultures in Our Time

- Black Panthers and Black Lives Matter Movements

- Michelle Obama’s Tuskegee University Commencement Speech

- Response to Panther Film

- AIDS in New York in "How to Survive a Plague" Film

- Harrison Bergeron and Malcolm X as Revolutionaries

- Public Service and Volunteers in American Society

- Black Lives Matter Social Movement and Ideology

- Social Movements and Democracies in Kitschelt's View

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, September 26). Black Power Movement in America. https://ivypanda.com/essays/black-power-movement-in-america/

"Black Power Movement in America." IvyPanda , 26 Sept. 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/black-power-movement-in-america/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Black Power Movement in America'. 26 September.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Black Power Movement in America." September 26, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/black-power-movement-in-america/.

1. IvyPanda . "Black Power Movement in America." September 26, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/black-power-movement-in-america/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Black Power Movement in America." September 26, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/black-power-movement-in-america/.

- Paired Texts

- Related Media

- Teacher Guide

For full functionality of this site it is necessary to enable JavaScript. Click here for instructions on how to enable JavaScript in your web browser.

- CommonLit is a nonprofit that has everything teachers and schools need for top-notch literacy instruction: a full-year ELA curriculum, benchmark assessments, and formative data. Browse Content Who We Are About

Breadcrumbs Section. Click here to navigate to respective pages.

The Black Power Movement

DOI link for The Black Power Movement

Get Citation

The Black Power Movement remains an enigma. Often misunderstood and ill-defined, this radical movement is now beginning to receive sustained and serious scholarly attention.

Peniel Joseph has collected the freshest and most impressive list of contributors around to write original essays on the Black Power Movement. Taken together they provide a critical and much needed historical overview of the Black Power era. Offering important examples of undocumented histories of black liberation, this volume offers both powerful and poignant examples of 'Black Power Studies' scholarship.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter | 26 pages, introduction: toward a historiography of the black power movement, chapter 1 | 28 pages, “alabama on avalon” rethinking the watts uprising and the character of black protest in los angeles, chapter 2 | 24 pages, amiri baraka, the congress of politics from the 1961 united nations protest to the 1972 gary convention, chapter 3 | 26 pages, black women, urban politics, and engendering black power, chapter 4 | 14 pages, black feminists respond to black power masculinism, chapter 5 | 36 pages, the third world women’s alliance black feminist radicalism and black power politics, chapter 6 | 22 pages, the roots of black power armed resistance and the radicalization of the civil rights movement, chapter 7 | 26 pages, “a red, black and green liberation jumpsuit” roy wilkins, the black panthers, and the conundrum of black power, chapter 8 | 36 pages, rainbow radicalism the rise of the radical ethnic nationalism, chapter 9 | 22 pages, “a holiday of our own” kwanzaa, cultural nationalism, and the promotion of a black power holiday, 1966–1985, chapter 10 | 28 pages, black studies, student activism, and the black power movement.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Taylor & Francis Online

- Taylor & Francis Group

- Students/Researchers

- Librarians/Institutions

Connect with us

Registered in England & Wales No. 3099067 5 Howick Place | London | SW1P 1WG © 2024 Informa UK Limited

We’re fighting to restore access to 500,000+ books in court this week. Join us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

The Black power movement : rethinking the civil rights-Black power era

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

9 Favorites

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station40.cebu on May 29, 2023

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

IMAGES

COMMENTS

In the late 1950s and the early to mid-1960s, a Muslim minister named Malcolm X rose to prominence in the United States during the struggle for Civil Rights....

History essay grade 12explanation of black power movement in the USAIf you want an Full explanation of the Topic just Click the link belowhttps://youtu.be/t5...

REVISION: THE BLACK POWER MOVEMENT. Do you have an educational app, video, ebook, course or eResource? Contribute to the Western Cape Education Department's ePortal to make a difference.

About Press Copyright Contact us Creators Advertise Developers Terms Privacy Policy & Safety How YouTube works Test new features NFL Sunday Ticket Press Copyright ...

Overview. "Black Power" refers to a militant ideology that aimed not at integration and accommodation with white America, but rather preached black self-reliance, self-defense, and racial pride. Malcolm X was the most influential thinker of what became known as the Black Power movement, and inspired others like Stokely Carmichael of the ...

The black power movement frightened most of white America and unsettled scores of black Americans. Malcolm X The inspiration behind much of the black power movement, Malcolm X's intellect, historical analysis, and powerful speeches impressed friend and foe alike. The primary spokesman for the Nation of Islam until 1964, he traveled to Mecca ...

The Black Power movement emerged in the 1960s with calls to reject integration efforts and embrace self-determination and self-reliance.

Black Power Introduction. If the nonviolence of the Southern Freedom Movement frightened mainstream people in the United States, the Black Power movement confronted institutional racism with a youthful boldness and fearlessness unseen since enslaved Africans took up arms in the Civil War. Malcolm X, the Black Panther Party, Dr. Martin Luther ...

Black Power Movement Growth—and Backlash. Stokely Carmichael speaking at a civil rights gathering in Washington, D.C. on April 13, 1970. King and Carmichael renewed their alliance in early 1968 ...

Although African American writers and politicians used the term "Black Power" for years, the expression first entered the lexicon of the civil rights movement during the Meredith March Against Fear in the summer of 1966. Martin Luther King, Jr., believed that Black Power was "essentially an emotional concept" that meant "different ...

Client: International Slavery Museum Liverpool.One of a series of four short films about black political movements.

The black power movement or black liberation movement was a branch or counterculture within the civil rights movement of the United States, reacting against its more moderate, mainstream, or incremental tendencies and motivated by a desire for safety and self-sufficiency that was not available inside redlined African American neighborhoods. Black power activists founded black-owned bookstores ...

The Black Power Movement. The Black Power Movement of the 1960s and 1970s was a political and social movement whose advocates believed in racial pride, self-sufficiency, and equality for all people of Black and African descent. Credited with first articulating "Black Power" in 1966, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee leader Stokely ...

Peniel E. Joseph, Waiting 'Til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America (New York, 2007); James Smethurst, The Black Arts Movement: Literary Nationalism in the 1960s and 1970s (Chapel Hill, 2005); and Jeffrey O. G. Ogbar, Black Power: Radical Politics and African American Identity (Baltimore, 2005). On the role of Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam in the development of ...

Black Power began as revolutionary movement in the 1960s and 1970s. It emphasized racial pride, economic empowerment, and the creation of political and cultural institutions. During this era, there was a rise in the demand for Black history courses, a greater embrace of African culture, and a spread of raw artistic expression displaying the realities of African Americans. The term "Black Power ...

The Black Power Movement was a political and social movement whose advocates believed in racial pride, self sufficiency and equality for all people of black and African descent. This essay will critically discuss the significant roles played by various leaders during the black power movement in USA. To begin with, the black power movement is ...

This is the Black power movement History Topic full explanationthe black power movement Essayhttps://youtu.be/zZJXHO9P_Kc?si=M5apDtfxxWValRYt

Black Power Movement in America Essay (Critical Writing) In America, the beginning of the 1960s was characterized by a number of political and civil movements that were aimed at providing the Black people with rights, freedoms, and opportunities. Regarding the thoughts developed by Malcolm X and Mr. King and the outcomes of their murders, many ...

Adopting a High Quality Instructional Material like CommonLit 360 curriculum accelerates student growth with grade-level rigor and built-in support. Get a quote to roll out EdReports-green curriculum today! CommonLit is a nonprofit that has everything teachers and schools need for top-notch literacy instruction: a full-year ELA curriculum ...

Power! (1966-68) The call for Black Power takes various forms across communities in black America. In Cleveland, Carl Stokes wins election as the first black...

ABSTRACT. The Black Power Movement remains an enigma. Often misunderstood and ill-defined, this radical movement is now beginning to receive sustained and serious scholarly attention. Peniel Joseph has collected the freshest and most impressive list of contributors around to write original essays on the Black Power Movement.

xii, 385 p., 10 p. of plates : 23 cm Includes bibliographical references (p. 279-354) and index Introduction : toward a historiography of the Black power movement / Peniel E. Joseph -- "Alabama on Avalon" : rethinking the Watts uprising and the character of Black protest in Los Angeles / Jeanne Theoharis -- Amiri Baraka, the Congress of African People and Black power politics from the 1961 ...

In 1965, one of the last traceable remnants of Jim Crow ideology were thought to be taken off the books with the passage of the Voting Rights Act. Despite th...