How to write a Reflection on Group Work Essay

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

Here are the exact steps you need to follow for a reflection on group work essay.

- Explain what Reflection Is

- Explore the benefits of group work

- Explore the challenges group

- Give examples of the benefits and challenges your group faced

- Discuss how your group handled your challenges

- Discuss what you will do differently next time

Do you have to reflect on how your group work project went?

This is a super common essay that teachers assign. So, let’s have a look at how you can go about writing a superb reflection on your group work project that should get great grades.

The essay structure I outline below takes the funnel approach to essay writing: it starts broad and general, then zooms in on your specific group’s situation.

Disclaimer: Make sure you check with your teacher to see if this is a good style to use for your essay. Take a draft to your teacher to get their feedback on whether it’s what they’re looking for!

This is a 6-step essay (the 7 th step is editing!). Here’s a general rule for how much depth to go into depending on your word count:

- 1500 word essay – one paragraph for each step, plus a paragraph each for the introduction and conclusion ;

- 3000 word essay – two paragraphs for each step, plus a paragraph each for the introduction and conclusion;

- 300 – 500 word essay – one or two sentences for each step.

Adjust this essay plan depending on your teacher’s requirements and remember to always ask your teacher, a classmate or a professional tutor to review the piece before submitting.

Here’s the steps I’ll outline for you in this advice article:

Step 1. Explain what ‘Reflection’ Is

You might have heard that you need to define your terms in essays. Well, the most important term in this essay is ‘reflection’.

So, let’s have a look at what reflection is…

Reflection is the process of:

- Pausing and looking back at what has just happened; then

- Thinking about how you can get better next time.

Reflection is encouraged in most professions because it’s believed that reflection helps you to become better at your job – we could say ‘reflection makes you a better practitioner’.

Think about it: let’s say you did a speech in front of a crowd. Then, you looked at video footage of that speech and realised you said ‘um’ and ‘ah’ too many times. Next time, you’re going to focus on not saying ‘um’ so that you’ll do a better job next time, right?

Well, that’s reflection: thinking about what happened and how you can do better next time.

It’s really important that you do both of the above two points in your essay. You can’t just say what happened. You need to say how you will do better next time in order to get a top grade on this group work reflection essay.

Scholarly Sources to Cite for Step 1

Okay, so you have a good general idea of what reflection is. Now, what scholarly sources should you use when explaining reflection? Below, I’m going to give you two basic sources that would usually be enough for an undergraduate essay. I’ll also suggest two more sources for further reading if you really want to shine!

I recommend these two sources to cite when explaining what reflective practice is and how it occurs. They are two of the central sources on reflective practice:

- Describe what happened during the group work process

- Explain how you felt during the group work process

- Look at the good and bad aspects of the group work process

- What were some of the things that got in the way of success? What were some things that helped you succeed?

- What could you have done differently to improve the situation?

- Action plan. What are you going to do next time to make the group work process better?

- What? Explain what happened

- So What? Explain what you learned

- Now What? What can I do next time to make the group work process better?

Possible Sources:

Bassot, B. (2015). The reflective practice guide: An interdisciplinary approach to critical reflection . Routledge.

Brock, A. (2014). What is reflection and reflective practice?. In The Early Years Reflective Practice Handbook (pp. 25-39). Routledge.

Gibbs, G. (1988) Learning by Doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods . Further Education Unit, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford.

Rolfe, G., Freshwater, D., Jasper, M. (2001). Critical reflection in nursing and the helping professions: a user’s guide. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Extension Sources for Top Students

Now, if you want to go deeper and really show off your knowledge, have a look at these two scholars:

- John Dewey – the first major scholar to come up with the idea of reflective practice

- Donald Schön – technical rationality, reflection in action vs. reflection on action

Get a Pdf of this article for class

Enjoy subscriber-only access to this article’s pdf

Step 2. Explore the general benefits of group work for learning

Once you have given an explanation of what group work is (and hopefully cited Gibbs, Rolfe, Dewey or Schon), I recommend digging into the benefits of group work for your own learning.

The teacher gave you a group work task for a reason: what is that reason?

You’ll need to explain the reasons group work is beneficial for you. This will show your teacher that you understand what group work is supposed to achieve. Here’s some ideas:

- Multiple Perspectives. Group work helps you to see things from other people’s perspectives. If you did the task on your own, you might not have thought of some of the ideas that your team members contributed to the project.

- Contribution of Unique Skills. Each team member might have a different set of skills they can bring to the table. You can explain how groups can make the most of different team members’ strengths to make the final contribution as good as it can be. For example, one team member might be good at IT and might be able to put together a strong final presentation, while another member might be a pro at researching using google scholar so they got the task of doing the initial scholarly research.

- Improved Communication Skills. Group work projects help you to work on your communication skills. Communication skills required in group work projects include speaking in turn, speaking up when you have ideas, actively listening to other team members’ contributions, and crucially making compromises for the good of the team.

- Learn to Manage Workplace Conflict. Lastly, your teachers often assign you group work tasks so you can learn to manage conflict and disagreement. You’ll come across this a whole lot in the workplace, so your teachers want you to have some experience being professional while handling disagreements.

You might be able to add more ideas to this list, or you might just want to select one or two from that list to write about depending on the length requirements for the essay.

Scholarly Sources for Step 3

Make sure you provide citations for these points above. You might want to use google scholar or google books and type in ‘Benefits of group work’ to find some quality scholarly sources to cite.

Step 3. Explore the general challenges group work can cause

Step 3 is the mirror image of Step 2. For this step, explore the challenges posed by group work.

Students are usually pretty good at this step because you can usually think of some aspects of group work that made you anxious or frustrated. Here are a few common challenges that group work causes:

- Time Consuming. You need to organize meetups and often can’t move onto the next component of the project until everyone has agree to move on. When working on your own you can just crack on and get it done. So, team work often takes a lot of time and requires significant pre-planning so you don’t miss your submission deadlines!

- Learning Style Conflicts. Different people learn in different ways. Some of us like to get everything done at the last minute or are not very meticulous in our writing. Others of us are very organized and detailed and get anxious when things don’t go exactly how we expect. This leads to conflict and frustration in a group work setting.

- Free Loaders. Usually in a group work project there’s people who do more work than others. The issue of free loaders is always going to be a challenge in group work, and you can discuss in this section how ensuring individual accountability to the group is a common group work issue.

- Communication Breakdown. This is one especially for online students. It’s often the case that you email team members your ideas or to ask them to reply by a deadline and you don’t hear back from them. Regular communication is an important part of group work, yet sometimes your team members will let you down on this part.

As with Step 3, consider adding more points to this list if you need to, or selecting one or two if your essay is only a short one.

8 Pros And Cons Of Group Work At University

| Pros of Group Work | Cons of Group Work |

|---|---|

| Members of your team will have different perspectives to bring to the table. Embrace team brainstorming to bring in more ideas than you would on your own. | You can get on with an individual task at your own pace, but groups need to arrange meet-ups and set deadlines to function effectively. This is time-consuming and requires pre-planning. |

| Each of your team members will have different skills. Embrace your IT-obsessed team member’s computer skills; embrace the organizer’s skills for keeping the group on track, and embrace the strongest writer’s editing skills to get the best out of your group. | Some of your team members will want to get everything done at once; others will procrastinate frequently. You might also have conflicts in strategic directions depending on your different approaches to learning. |

| Use group work to learn how to communicate more effectively. Focus on active listening and asking questions that will prompt your team members to expand on their ideas. | Many groups struggle with people who don’t carry their own weight. You need to ensure you delegate tasks to the lazy group members and be stern with them about sticking to the deadlines they agreed upon. |

| In the workforce you’re not going to get along with your colleagues. Use group work at university to learn how to deal with difficult team members calmly and professionally. | It can be hard to get group members all on the same page. Members don’t rely to questions, get anxiety and shut down, or get busy with their own lives. It’s important every team member is ready and available for ongoing communication with the group. |

You’ll probably find you can cite the same scholarly sources for both steps 2 and 3 because if a source discusses the benefits of group work it’ll probably also discuss the challenges.

Step 4. Explore the specific benefits and challenges your group faced

Step 4 is where you zoom in on your group’s specific challenges. Have a think: what were the issues you really struggled with as a group?

- Was one team member absent for a few of the group meetings?

- Did the group have to change some deadlines due to lack of time?

- Were there any specific disagreements you had to work through?

- Did a group member drop out of the group part way through?

- Were there any communication break downs?

Feel free to also mention some things your group did really well. Have a think about these examples:

- Was one member of the group really good at organizing you all?

- Did you make some good professional relationships?

- Did a group member help you to see something from an entirely new perspective?

- Did working in a group help you to feel like you weren’t lost and alone in the process of completing the group work component of your course?

Here, because you’re talking about your own perspectives, it’s usually okay to use first person language (but check with your teacher). You are also talking about your own point of view so citations might not be quite as necessary, but it’s still a good idea to add in one or two citations – perhaps to the sources you cited in Steps 2 and 3?

Step 5. Discuss how your group managed your challenges

Step 5 is where you can explore how you worked to overcome some of the challenges you mentioned in Step 4.

So, have a think:

- Did your group make any changes part way through the project to address some challenges you faced?

- Did you set roles or delegate tasks to help ensure the group work process went smoothly?

- Did you contact your teacher at any point for advice on how to progress in the group work scenario?

- Did you use technology such as Google Docs or Facebook Messenger to help you to collaborate more effectively as a team?

In this step, you should be showing how your team was proactive in reflecting on your group work progress and making changes throughout the process to ensure it ran as smoothly as possible. This act of making little changes throughout the group work process is what’s called ‘Reflection in Action’ (Schön, 2017).

Scholarly Source for Step 5

Schön, D. A. (2017). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action . Routledge.

Step 6. Conclude by exploring what you will do differently next time

Step 6 is the most important step, and the one far too many students skip. For Step 6, you need to show how you not only reflected on what happened but also are able to use that reflection for personal growth into the future.

This is the heart and soul of your piece: here, you’re tying everything together and showing why reflection is so important!

This is the ‘action plan’ step in Gibbs’ cycle (you might want to cite Gibbs in this section!).

For Step 6, make some suggestions about how (based on your reflection) you now have some takeaway tips that you’ll bring forward to improve your group work skills next time. Here’s some ideas:

- Will you work harder next time to set deadlines in advance?

- Will you ensure you set clearer group roles next time to ensure the process runs more smoothly?

- Will you use a different type of technology (such as Google Docs) to ensure group communication goes more smoothly?

- Will you make sure you ask for help from your teacher earlier on in the process when you face challenges?

- Will you try harder to see things from everyone’s perspectives so there’s less conflict?

This step will be personalized based upon your own group work challenges and how you felt about the group work process. Even if you think your group worked really well together, I recommend you still come up with one or two ideas for continual improvement. Your teacher will want to see that you used reflection to strive for continual self-improvement.

Scholarly Source for Step 6

Step 7. edit.

Okay, you’ve got the nuts and bolts of the assessment put together now! Next, all you’ve got to do is write up the introduction and conclusion then edit the piece to make sure you keep growing your grades.

Here’s a few important suggestions for this last point:

- You should always write your introduction and conclusion last. They will be easier to write now that you’ve completed the main ‘body’ of the essay;

- Use my 5-step I.N.T.R.O method to write your introduction;

- Use my 5 C’s Conclusion method to write your conclusion;

- Use my 5 tips for editing an essay to edit it;

- Use the ProWritingAid app to get advice on how to improve your grammar and spelling. Make sure to also use the report on sentence length. It finds sentences that are too long and gives you advice on how to shorten them – such a good strategy for improving evaluative essay quality!

- Make sure you contact your teacher and ask for a one-to-one tutorial to go through the piece before submitting. This article only gives general advice, and you might need to make changes based upon the specific essay requirements that your teacher has provided.

That’s it! 7 steps to writing a quality group work reflection essay. I hope you found it useful. If you liked this post and want more clear and specific advice on writing great essays, I recommend signing up to my personal tutor mailing list.

Let’s sum up with those 7 steps one last time:

- Explain what ‘Reflection’ Is

- Explore the benefits of group work for learning

- Explore the challenges of group work for learning

- Explore the specific benefits and challenges your group faced

- Discuss how your group managed your challenges

- Conclude by exploring what you will do differently next time

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 15 Green Flags in a Relationship

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 15 Signs you're Burnt Out, Not Lazy

2 thoughts on “How to write a Reflection on Group Work Essay”

Great instructions on writing a reflection essay. I would not change anything.

Thanks so much for your feedback! I really appreciate it. – Chris.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Group Writing

What this handout is about.

Whether in the academic world or the business world, all of us are likely to participate in some form of group writing—an undergraduate group project for a class, a collaborative research paper or grant proposal, or a report produced by a business team. Writing in a group can have many benefits: multiple brains are better than one, both for generating ideas and for getting a job done. However, working in a group can sometimes be stressful because there are various opinions and writing styles to incorporate into one final product that pleases everyone. This handout will offer an overview of the collaborative process, strategies for writing successfully together, and tips for avoiding common pitfalls. It will also include links to some other handouts that may be especially helpful as your group moves through the writing process.

Disclaimer and disclosure

As this is a group writing handout, several Writing Center coaches worked together to create it. No coaches were harmed in this process; however, we did experience both the pros and the cons of the collaborative process. We have personally tested the various methods for sharing files and scheduling meetings that are described here. However, these are only our suggestions; we do not advocate any particular service or site.

The spectrum of collaboration in group writing

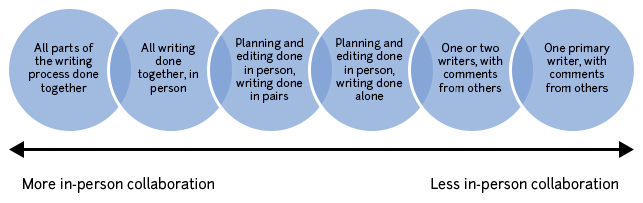

All writing can be considered collaborative in a sense, though we often don’t think of it that way. It would be truly surprising to find an author whose writing, even if it was completed independently, had not been influenced at some point by discussions with friends or colleagues. The range of possible collaboration varies from a group of co-authors who go through each portion of the writing process together, writing as a group with one voice, to a group with a primary author who does the majority of the work and then receives comments or edits from the co-authors.

Group projects for classes should usually fall towards the middle to left side of this diagram, with group members contributing roughly equally. However, in collaborations on research projects, the level of involvement of the various group members may vary widely. The key to success in either case is to be clear about group member responsibilities and expectations and to give credit (authorship) to members who contribute an appropriate amount. It may be useful to credit each group member for their various contributions.

Overview of steps of the collaborative process

Here we outline the steps of the collaborative process. You can use these questions to focus your thinking at each stage.

- Share ideas and brainstorm together.

- Formulate a draft thesis or argument .

- Think about your assignment and the final product. What should it look like? What is its purpose? Who is the intended audience ?

- Decide together who will write which parts of the paper/project.

- What will the final product look like?

- Arrange meetings: How often will the group or subsets of the group meet? When and where will the group meet? If the group doesn’t meet in person, how will information be shared?

- Scheduling: What is the deadline for the final product? What are the deadlines for drafts?

- How will the group find appropriate sources (books, journal articles, newspaper articles, visual media, trustworthy websites, interviews)? If the group will be creating data by conducting research, how will that process work?

- Who will read and process the information found? This task again may be done by all members or divided up amongst members so that each person becomes the expert in one area and then teaches the rest of the group.

- Think critically about the sources and their contributions to your topic. Which evidence should you include or exclude? Do you need more sources?

- Analyze the data. How will you interpret your findings? What is the best way to present any relevant information to your readers-should you include pictures, graphs, tables, and charts, or just written text?

- Note that brainstorming the main points of your paper as a group is helpful, even if separate parts of the writing are assigned to individuals. You’ll want to be sure that everyone agrees on the central ideas.

- Where does your individual writing fit into the whole document?

- Writing together may not be feasible for longer assignments or papers with coauthors at different universities, and it can be time-consuming. However, writing together does ensure that the finished document has one cohesive voice.

- Talk about how the writing session should go BEFORE you get started. What goals do you have? How will you approach the writing task at hand?

- Many people find it helpful to get all of the ideas down on paper in a rough form before discussing exact phrasing.

- Remember that everyone has a different writing style! The most important thing is that your sentences be clear to readers.

- If your group has drafted parts of the document separately, merge your ideas together into a single document first, then focus on meshing the styles. The first concern is to create a coherent product with a logical flow of ideas. Then the stylistic differences of the individual portions must be smoothed over.

- Revise the ideas and structure of the paper before worrying about smaller, sentence-level errors (like problems with punctuation, grammar, or word choice). Is the argument clear? Is the evidence presented in a logical order? Do the transitions connect the ideas effectively?

- Proofreading: Check for typos, spelling errors, punctuation problems, formatting issues, and grammatical mistakes. Reading the paper aloud is a very helpful strategy at this point.

Helpful collaborative writing strategies

Attitude counts for a lot.

Group work can be challenging at times, but a little enthusiasm can go a long way to helping the momentum of the group. Keep in mind that working in a group provides a unique opportunity to see how other people write; as you learn about their writing processes and strategies, you can reflect on your own. Working in a group inherently involves some level of negotiation, which will also facilitate your ability to skillfully work with others in the future.

Remember that respect goes along way! Group members will bring different skill sets and various amounts and types of background knowledge to the table. Show your fellow writers respect by listening carefully, talking to share your ideas, showing up on time for meetings, sending out drafts on schedule, providing positive feedback, and taking responsibility for an appropriate share of the work.

Start early and allow plenty of time for revising

Getting started early is important in individual projects; however, it is absolutely essential in group work. Because of the multiple people involved in researching and writing the paper, there are aspects of group projects that take additional time, such as deciding and agreeing upon a topic. Group projects should be approached in a structured way because there is simply less scheduling flexibility than when you are working alone. The final product should reflect a unified, cohesive voice and argument, and the only way of accomplishing this is by producing multiple drafts and revising them multiple times.

Plan a strategy for scheduling

One of the difficult aspects of collaborative writing is finding times when everyone can meet. Much of the group’s work may be completed individually, but face-to-face meetings are useful for ensuring that everyone is on the same page. Doodle.com , whenisgood.net , and needtomeet.com are free websites that can make scheduling easier. Using these sites, an organizer suggests multiple dates and times for a meeting, and then each group member can indicate whether they are able to meet at the specified times.

It is very important to set deadlines for drafts; people are busy, and not everyone will have time to read and respond at the last minute. It may help to assign a group facilitator who can send out reminders of the deadlines. If the writing is for a co-authored research paper, the lead author can take responsibility for reminding others that comments on a given draft are due by a specific date.

Submitting drafts at least one day ahead of the meeting allows other authors the opportunity to read over them before the meeting and arrive ready for a productive discussion.

Find a convenient and effective way to share files

There are many different ways to share drafts, research materials, and other files. Here we describe a few of the potential options we have explored and found to be functional. We do not advocate any one option, and we realize there are other equally useful options—this list is just a possible starting point for you:

- Email attachments. People often share files by email; however, especially when there are many group members or there is a flurry of writing activity, this can lead to a deluge of emails in everyone’s inboxes and significant confusion about which file version is current.

- Google documents . Files can be shared between group members and are instantaneously updated, even if two members are working at once. Changes made by one member will automatically appear on the document seen by all members. However, to use this option, every group member must have a Gmail account (which is free), and there are often formatting issues when converting Google documents back to Microsoft Word.

- Dropbox . Dropbox.com is free to join. It allows you to share up to 2GB of files, which can then be synched and accessible from multiple computers. The downside of this approach is that everyone has to join, and someone must install the software on at least one personal computer. Dropbox can then be accessed from any computer online by logging onto the website.

- Common server space. If all group members have access to a shared server space, this is often an ideal solution. Members of a lab group or a lab course with available server space typically have these resources. Just be sure to make a folder for your project and clearly label your files.

Note that even when you are sharing or storing files for group writing projects in a common location, it is still essential to periodically make back-up copies and store them on your own computer! It is never fun to lose your (or your group’s) hard work.

Try separating the tasks of revising and editing/proofreading

It may be helpful to assign giving feedback on specific items to particular group members. First, group members should provide general feedback and comments on content. Only after revising and solidifying the main ideas and structure of the paper should you move on to editing and proofreading. After all, there is no point in spending your time making a certain sentence as beautiful and correct as possible when that sentence may later be cut out. When completing your final revisions, it may be helpful to assign various concerns (for example, grammar, organization, flow, transitions, and format) to individual group members to focus this process. This is an excellent time to let group members play to their strengths; if you know that you are good at transitions, offer to take care of that editing task.

Your group project is an opportunity to become experts on your topic. Go to the library (in actuality or online), collect relevant books, articles, and data sources, and consult a reference librarian if you have any issues. Talk to your professor or TA early in the process to ensure that the group is on the right track. Find experts in the field to interview if it is appropriate. If you have data to analyze, meet with a statistician. If you are having issues with the writing, use the online handouts at the Writing Center or come in for a face-to-face meeting: a coach can meet with you as a group or one-on-one.

Immediately dividing the writing into pieces

While this may initially seem to be the best way to approach a group writing process, it can also generate more work later on, when the parts written separately must be put together into a unified document. The different pieces must first be edited to generate a logical flow of ideas, without repetition. Once the pieces have been stuck together, the entire paper must be edited to eliminate differences in style and any inconsistencies between the individual authors’ various chunks. Thus, while it may take more time up-front to write together, in the end a closer collaboration can save you from the difficulties of combining pieces of writing and may create a stronger, more cohesive document.

Procrastination

Although this is solid advice for any project, it is even more essential to start working on group projects in a timely manner. In group writing, there are more people to help with the work-but there are also multiple schedules to juggle and more opinions to seek.

Being a solo group member

Not everyone enjoys working in groups. You may truly desire to go solo on this project, and you may even be capable of doing a great job on your own. However, if this is a group assignment, then the prompt is asking for everyone to participate. If you are feeling the need to take over everything, try discussing expectations with your fellow group members as well as the teaching assistant or professor. However, always address your concerns with group members first. Try to approach the group project as a learning experiment: you are learning not only about the project material but also about how to motivate others and work together.

Waiting for other group members to do all of the work

If this is a project for a class, you are leaving your grade in the control of others. Leaving the work to everyone else is not fair to your group mates. And in the end, if you do not contribute, then you are taking credit for work that you did not do; this is a form of academic dishonesty. To ensure that you can do your share, try to volunteer early for a portion of the work that you are interested in or feel you can manage.

Leaving all the end work to one person

It may be tempting to leave all merging, editing, and/or presentation work to one person. Be careful. There are several reasons why this may be ill-advised. 1) The editor/presenter may not completely understand every idea, sentence, or word that another author wrote, leading to ambiguity or even mistakes in the end paper or presentation. 2) Editing is tough, time-consuming work. The editor often finds himself or herself doing more work than was expected as they try to decipher and merge the original contributions under the time pressure of an approaching deadline. If you decide to follow this path and have one person combine the separate writings of many people, be sure to leave plenty of time for a final review by all of the writers. Ask the editor to send out the final draft of the completed work to each of the authors and let every contributor review and respond to the final product. Ideally, there should also be a test run of any live presentations that the group or a representative may make.

Entirely negative critiques

When giving feedback or commenting on the work of other group members, focusing only on “problems” can be overwhelming and put your colleagues on the defensive. Try to highlight the positive parts of the project in addition to pointing out things that need work. Remember that this is constructive feedback, so don’t forget to add concrete, specific suggestions on how to proceed. It can also be helpful to remind yourself that many of your comments are your own opinions or reactions, not absolute, unquestionable truths, and then phrase what you say accordingly. It is much easier and more helpful to hear “I had trouble understanding this paragraph because I couldn’t see how it tied back to our main argument” than to hear “this paragraph is unclear and irrelevant.”

Writing in a group can be challenging, but it is also a wonderful opportunity to learn about your topic, the writing process, and the best strategies for collaboration. We hope that our tips will help you and your group members have a great experience.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Cross, Geoffrey. 1994. Collaboration and Conflict: A Contextual Exploration of Group Writing and Positive Emphasis . Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Ede, Lisa S., and Andrea Lunsford. 1990. Singular Texts/Plural Authors: Perspectives on Collaborative Writing . Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Speck, Bruce W. 2002. Facilitating Students’ Collaborative Writing . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Eberly Center

Teaching excellence & educational innovation, what are the benefits of group work.

“More hands make for lighter work.” “Two heads are better than one.” “The more the merrier.”

These adages speak to the potential groups have to be more productive, creative, and motivated than individuals on their own.

Benefits for students

Group projects can help students develop a host of skills that are increasingly important in the professional world (Caruso & Woolley, 2008; Mannix & Neale, 2005). Positive group experiences, moreover, have been shown to contribute to student learning, retention and overall college success (Astin, 1997; Tinto, 1998; National Survey of Student Engagement, 2006).

Properly structured, group projects can reinforce skills that are relevant to both group and individual work, including the ability to:

- Break complex tasks into parts and steps

- Plan and manage time

- Refine understanding through discussion and explanation

- Give and receive feedback on performance

- Challenge assumptions

- Develop stronger communication skills.

Group projects can also help students develop skills specific to collaborative efforts, allowing students to...

- Tackle more complex problems than they could on their own.

- Delegate roles and responsibilities.

- Share diverse perspectives.

- Pool knowledge and skills.

- Hold one another (and be held) accountable.

- Receive social support and encouragement to take risks.

- Develop new approaches to resolving differences.

- Establish a shared identity with other group members.

- Find effective peers to emulate.

- Develop their own voice and perspectives in relation to peers.

While the potential learning benefits of group work are significant, simply assigning group work is no guarantee that these goals will be achieved. In fact, group projects can – and often do – backfire badly when they are not designed , supervised , and assessed in a way that promotes meaningful teamwork and deep collaboration.

Benefits for instructors

Faculty can often assign more complex, authentic problems to groups of students than they could to individuals. Group work also introduces more unpredictability in teaching, since groups may approach tasks and solve problems in novel, interesting ways. This can be refreshing for instructors. Additionally, group assignments can be useful when there are a limited number of viable project topics to distribute among students. And they can reduce the number of final products instructors have to grade.

Whatever the benefits in terms of teaching, instructors should take care only to assign as group work tasks that truly fulfill the learning objectives of the course and lend themselves to collaboration. Instructors should also be aware that group projects can add work for faculty at different points in the semester and introduce its own grading complexities .

Astin, A. (1993). What matters in college? Four critical years revisited. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Caruso, H.M., & Wooley, A.W. (2008). Harnessing the power of emergent interdependence to promote diverse team collaboration. Diversity and Groups. 11, 245-266.

Mannix, E., & Neale, M.A. (2005). What differences make a difference? The promise and reality of diverse teams in organizations. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 6(2), 31-55.

National Survey of Student Engagement Report. (2006). http://nsse.iub.edu/NSSE_2006_Annual_Report/docs/NSSE_2006_Annual_Report.pdf .

Tinto, V. (1987). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Our Mission

Group Work That Works

Educators weigh in on solutions to the common pitfalls of group work.

Mention group work and you’re confronted with pointed questions and criticisms. The big problems, according to our audience: One or two students do all the work; it can be hard on introverts; and grading the group isn’t fair to the individuals.

But the research suggests that a certain amount of group work is beneficial.

“The most effective creative process alternates between time in groups, collaboration, interaction, and conversation... [and] times of solitude, where something different happens cognitively in your brain,” says Dr. Keith Sawyer, a researcher on creativity and collaboration, and author of Group Genius: The Creative Power of Collaboration .

So we looked through our archives and reached out to educators on Facebook to find out what solutions they’ve come up with for these common problems.

Making Sure Everyone Participates

“How many times have we put students in groups only to watch them interact with their laptops instead of each other? Or complain about a lazy teammate?” asks Mary Burns, a former French, Latin, and English middle and high school teacher who now offers professional development in technology integration.

Unequal participation is perhaps the most common complaint about group work. Still, a review of Edutopia’s archives—and the tens of thousands of insights we receive in comments and reactions to our articles—revealed a handful of practices that educators use to promote equal participation. These involve setting out clear expectations for group work, increasing accountability among participants, and nurturing a productive group work dynamic.

Norms: At Aptos Middle School in San Francisco, the first step for group work is establishing group norms. Taji Allen-Sanchez, a sixth- and seventh-grade science teacher, lists expectations on the whiteboard, such as “everyone contributes” and “help others do things for themselves.”

For ambitious projects, Mikel Grady Jones, a high school math teacher in Houston, takes it a step further, asking her students to sign a group contract in which they agree on how they’ll divide the tasks and on expectations like “we all promise to do our work on time.” Heather Wolpert-Gawron, an English middle school teacher in Los Angeles, suggests creating a classroom contract with your students at the start of the year, so that agreed-upon norms can be referenced each time a new group activity begins.

Group size: It’s a simple fix, but the size of the groups can help establish the right dynamics. Generally, smaller groups are better because students can’t get away with hiding while the work is completed by others.

“When there is less room to hide, nonparticipation is more difficult,” says Burns. She recommends groups of four to five students, while Brande Tucker Arthur, a 10th-grade biology teacher in Lynchburg, Virginia, recommends even smaller groups of two or three students.

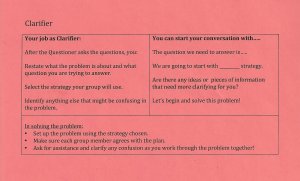

Meaningful roles: Roles can play an important part in keeping students accountable, but not all roles are helpful. A role like materials manager, for example, won’t actively engage a student in contributing to a group problem; the roles must be both meaningful and interdependent.

At University Park Campus School , a grade 7–12 school in Worcester, Massachusetts, students take on highly interdependent roles like summarizer, questioner, and clarifier. In an ongoing project, the questioner asks probing questions about the problem and suggests a few ideas on how to solve it, while the clarifier attempts to clear up any confusion, restates the problem, and selects a possible strategy the group will use as they move forward.

At Design 39, a K–8 school in San Diego, groups and roles are assigned randomly using Random Team Generator , but ClassDojo , Team Shake , and drawing students’ names from a container can also do the trick. In a practice called vertical learning, Design 39 students conduct group work publicly, writing out their thought processes on whiteboards to facilitate group feedback. The combination of randomizing teams and public sharing exposes students to a range of problem-solving approaches, gets them more comfortable with making mistakes, promotes teamwork, and allows kids to utilize different skill sets during each project.

Rich tasks: Making sure that a project is challenging and compelling is critical. A rich task is a problem that has multiple pathways to the solution and that one person would have difficulty solving on their own.

In an eighth-grade math class at Design 39, one recent rich task explored the concept of how monetary investments grow: Groups were tasked with solving exponential growth problems using simple and compound interest rates.

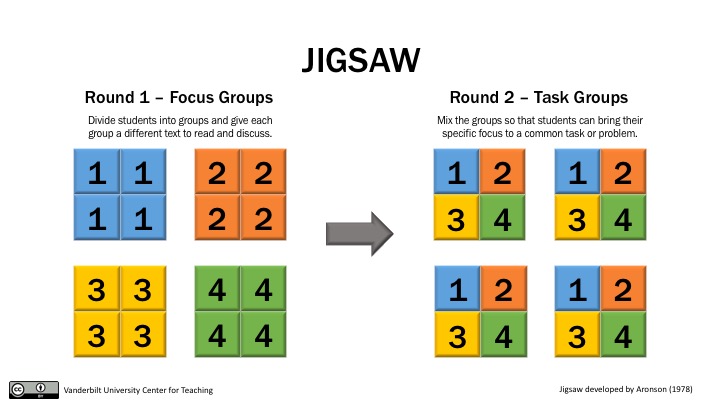

Rich tasks are not just for math class. When Dan St. Louis, the principal of University Park, was a teacher, he asked his English students to come up with a group definition of the word Orwellian . They did this through the jigsaw method, a type of grouping strategy that John Hattie’s study Visible Learning ranked as highly effective.

“Five groups of five students might each read a different news article about the modern world,” says St. Louis. “Then each student would join a new group of five where they need to explain their previous group’s article to each other and make connections to each. Using these connections, the group must then construct a definition of the word Orwellian .” For another example of the jigsaw approach, see this video from Cult of Pedagogy.

Supporting Introverts

Teachers worry about the impact of group work on introverts. Some of our educators suggest that giving introverts choice in who they’re grouped with can help them feel more comfortable.

“Even the quietest students are usually comfortable and confident when they are with peers with whom they connect,” says Shelly Kunkle, a veteran teacher at Wasawee Middle School in North Webster, Indiana. Wolpert-Gawron asks her students to list four peers they want to work with and then makes sure to pair them with one from their list.

Having defined roles within groups—like clarifier or questioner—also provides structure for students who may be less comfortable within complex social dynamics, and ensures that introverts don’t get overshadowed by their more extroverted peers.

Finally, be mindful that introverted students often simply need time to recharge. “Many introverts do not mind and even enjoy interacting in groups as long as they get some quiet time and solitude to recharge. It’s not about being shy or feeling unsafe in a large group,” says Barb Larochelle, a recently retired high school English teacher in Edmonton, Alberta, who taught for 29 years.

“I planned classes with some time to work quietly alone, some time to interact in smaller groups or as a whole class, and some time to get up and move around a little. A whole class of any one of those is going to be hard on one group, but a balance works well.”

Assessing Group Work

Grading group work is problematic. Often, you don’t have a clear understanding of what each student knows, and a single student’s lack of effort can torpedo the group grade. To some degree, strategies that assign meaningful roles or that require public presentations from groups provide a window in to each student’s knowledge and contributions.

But not all classwork needs to be graded. Suzanna Kruger, a high school science teacher in Seaside, Oregon, doesn’t grade group work—there are plenty of individual assignments that receive grades, and plenty of other opportunities for formative assessment.

John McCarthy, a former high school English and social studies teacher and current education consultant and adjunct professor at Madonna University for the graduate department for education, suggests using group presentations or group products as a non-graded review for a test. But if you want to grade group work, he recommends making all academic assessments within group work individual assessments. For example, instead of grading a group presentation, McCarthy grades each student on an essay, which the students then use to create their group presentation.

Laura Moffit, a fifth-grade teacher in Wilmington, North Carolina, uses self and peer evaluations to shed light on how each student is contributing to group work—starting with a lesson on how to do an objective evaluation. “Just have students circle :), :|, or :( on three to five statements about each partner, anonymously,” Moffit commented on Facebook. “Then give the evaluations back to each group member. Finding out what people really think of your performance is a wake-up call.”

And Ted Malefyt, a middle school science teacher in Hamilton, Michigan, carries a clipboard with the class list formatted in a spreadsheet and walks around checking in on students while they do group work.

“Using this spreadsheet, you have your own record of which student is meeting your expectations and who needs extra help,” explains Malefyt. “As formative assessment takes place, quickly document with simple checkmarks.”

Working in Groups

Working in a group can be enjoyable or frustrating--sometimes both. The best way to ensure a good working experience in groups is to think hard about whether a project is best done in a group, and, if so, to have a clear set of expectations about group work.

Why Work in Groups?

You might choose to work or write a paper in a group rather than individually for many reasons. Some of the reasons include practical experience while others highlight why group work might provide a better learning experience:

- In group work, you can draw on each group member's knowledge and perspectives, frequently giving you a more well thought out paper at the end or a better understanding of the class material for exams, labs, etc.

- You can also draw on people's different strengths. For example, you might be a great proofreader while someone else is much better at organizing papers.

- Groups are great for motivation: they force you to be responsible to others and frequently, then, do more and better work on a project than you might when only responsible to yourself.

- Group work helps keep you on task. It's harder to procrastinate when working with others.

- Working in groups, especially writing texts together, mirrors working styles common outside school. In business, industry, and research organizations, collaborative work is the norm rather than the exception.

Writing Tasks Suited to Group Work

Although any piece of writing can be group-authored, some types of writing simply "make more sense" to be written in groups or are ideal for cutting down on certain aspects of the work load.

Whether you've chosen to do a group project or have been assigned to work together, any group works better if all members know the reason why more than one person is involved in writing the paper. Understanding what a group adds to the project helps alleviate some of the problems associated with group work, such as thinking you need to do it all yourself. While not exhaustive, the following are some of the types of papers that are typically better written when worked on in groups. To read more, choose any of the items below:

Papers Requiring "Original" Research

Whenever you have a paper that requires you to observe things, interview other experts, conduct surveys, or do any other kind of "field" research, having more than one person to divide these tasks among allows you to write a more thoroughly researched paper. Also, because these kinds of sources are frequently hard to "make sense" of, having more than one perspective on what you find is a great help in deciding how to use the information in a paper. For example, having more than one person observe the same thing frequently gives you two different perspectives on what happened.

Papers Requiring Library Research

Although most of us might be satisfied with two or three sources in a research paper using written sources, instructors usually expect more. Working with multiple people allows you to break up library tasks more easily and do a more thorough search for relevant material. For example, one person can check Internet sources, another might have to check a certain database in the library (like SAGE) while another works on a different database more specific to your topic (e.g. ERIC for education, MLA for literature, etc.). Also, the diversity of perspectives in a group helps you decide which sources are most relevant for your argument and audience.

Any Type of Argument

Arguments, by their very nature, involve having a good sense of audience, including audiences that may not agree with you. Imagining all the possible reactions to your audience is a difficult task with these types of papers. The diversity of perspectives and experiences of multiple people are a great advantage here. This is particularly true of "public" issues which affect many people because it is easy to assume your perspective on what the public thinks is "right" as opposed to being subject to your own, limited experience. This is equally true of more "academic" arguments because each member of a group might have a different sense, depending on their past course work and field experience, of what a disciplinary audience is expecting and what has already been said about a topic.

Interpretations

A paper that requires some type of interpretation--of literature, a design structure, a piece of art, etc.--always includes various perspectives, whether it be the historical perspective of the piece, the context of the city in which a landscape is designed, or the perspective of the interpreter. Given how important perspective is to this type of writing and thinking, reviewing or interpreting work from a variety of perspectives helps strengthen these papers. Such variety is a normal part of group work but much harder to get at individually.

Cultural Analyses

Any analysis of something cultural, whether it be from an anthropological perspective, a political science view of a public issue, or an analysis of a popular film, involves a "reading" or interpretation of the culture's context as well. However, context is never simply one thing and can be "read", much like a poem, in many ways. Having a variety of "eyes" to analyze a cultural scene, then, gives your group an advantage over single-authored papers that may be more limited.

Lab/Field Reports

Any type of experiment or field research involving observation and/or interpretation of data can benefit from multiple participants. More observers help lessen the work load and provide more data from a single observation which can lead to better, or even more objective, interpretations. For these reasons, much work in science is collaborative.

Any Type of Evaluation

An evaluation paper, such as reviews, critiques, or case reports, implies the ability to make and defend a judgment. judgments, as we all know, can be very idiosyncratic when only one person interprets the data or object at hand. As a result, performing an evaluation in a group allows you to gain multiple perspectives, challenge each other's ideas and assumptions, and thus defend a judgment that may not be as subject to bias.

Fact and Fiction: Common Fears about Group Work

Group work can be a frightening prospect for many people, especially in a school setting when so much of what we do is only "counted" (i.e. graded) if it's been completed individually. Some of these fears are fictions, but others are well founded and can be addressed by being careful about how group work is set up.

My individual ideas will be lost

Fact or Fiction? Both

In any group, no one's ideas count more than another's; as a result, you will not always get a given idea into a paper exactly as you originally thought it. However, getting your ideas challenged and changed is the very reason to do a group project. The key is to avoid losing your ideas entirely (i.e. being silenced in a group) without trying to control the group and silencing others.

Encourage Disagreement

It's okay to argue. Only through arguing with other members can you test the strength of not only others' ideas but also your own. Just be careful to keep the disagreement on the issue, not on personalities.

Encourage a Collaborative Attitude

No paper, even if you write it alone, is solely a reflection of your own ideas; the paper includes ideas you've gotten from class, from reading, from research. Think of your group members, and encourage them to think of you, as yet another source of knowledge.

Be Ready to Compromise

Look for ways in which differing ideas might be used to come up with a "new" idea that includes parts of both. It's okay to "stick to your guns," but remember everyone gives up a little in a group interaction. You must determine when you're willing to bend and when you're not.

Consider Including the Disagreement in the Paper

Depending on the type of paper you're writing, it's frequently okay to include more than one "right" answer by showing both are supportable with available evidence. In fact, papers which present disagreement without resolutions can sometimes be better than those that argue for only one solution or point of view.

I could write it better myself

Fact or Fiction? Usually both

Even if you are an excellent writer, collaboratively written papers are usually better than a single-authored one if for no other reason than the content is better: it is better researched, more well thought out, includes more perspectives, etc. The only time this is not true is if you've chosen to group-author a paper that does not need collaboration. However, writing a good final draft of a collaboratively written paper does take work that all group members should be prepared to do. To read more about collaborating successfully, choose any of the items below:

Divide the Writing Tasks

While everyone is not necessarily a great writer in all aspects, they usually know what they do well. Someone may be great at organizing but not be a good proofreader. Someone else might be great using vivid language, but lose their writing focus. Have group members write what they're best at and/or ask them to read the first draft for specific things they know well.

Leave Enough Time for Revising

First drafts of collaborative papers are frequently much worse than first drafts of individual papers because many disagreements are still being worked out when writing. Leave yourselves, then, a lot of time to critique the first draft and rewrite it.

Divide the Paper into Sections

People in your group may know a lot more about certain topics in the paper because they did the research for that section or may have more experience writing, say, a methods section than others. To get a good first draft going, divide tasks up according to what people feel the most comfortable with. Be sure, however, to do a lot of peer review as well.

Be Critical

One of the advantages of group work is you learn to read your own and others' writing more critically. Since this is your work too, don't be afraid to suggest and make changes on parts of the paper, even if you didn't write them in the drafting process. Every section, including yours, belongs to everyone in the group.

My grade will depend on what others do

Fact or Fiction? Fact

Although some instructors make provisions for individual grades even on a collaborative project, the fact remains that at least a part, if not the whole grade will depend on what others do. Although this may be frightening, the positive side to this is that it increases people's motivation and investment in the project. Of course, not everyone will care about grades as much as others. In this case, the group needs to make decisions early on for the "slacker" contingency. To read more about how to deal with unequal investments in the task, choose any of the items below:

Make Rules and Stick to Them

Before you even start work on a project, make rules about what will happen to those members not doing their part and outline the consequences. Here are some possible "consequences" other groups have used:

- If someone misses a meeting, or doesn't do a certain task, he/she has to type the final paper, buy pizza for the next meeting, etc.

- If more than one meeting is missed or a member consistently fails to do what she/he is supposed to, the group can decide not to include that name on the project. (Check this one with your instructor)

- In the same scenario, the group can decide to write a written evaluation of the member's work and pass it in to the instructor with the paper.

No one, usually, wants to anger their peers. When someone isn't doing his/her work, other group members need to tell that member. Many times people who end up doing more than their share do so because they don't complain.

Deal with It

This may sound harsh, but the reality of life outside of school is that some people do more work than others but are not necessarily penalized for it. You need to learn how to deal with these issues given that in the working world, you are frequently dependent on others you work with. Learning how to handle such situations now is a good learning experience in itself.

Group work will take more time than if I did it myself

There is no way around this, so be prepared. Even if you divide up many of the early tasks (research, etc.) which lessens the time you might put in individually, writing a collaborative paper takes a lot of time. It's time well spent as the final project is usually better than what any one individual could do, but don't fool yourself into thinking choosing a group option will mean less work. It hardly ever does.

My group members aren't as smart as I am

Fact or Fiction? Fiction

This is a dangerous attitude to bring into a group situation. If you honestly believe it's true, you should probably not choose group work if it's optional. If you don't have a choice, then consider the fact that other people might be thinking the same of you. To read about how your group can avoid this, choose any of the items below:

Discuss Member's Strengths and Weaknesses

At the first meeting, have each group member do a personal inventory covering a wide range of issues relevant to the work you'll do together. Remember that while one person may be good at ideas/course content, someone else may have strengths as a critical reader, researcher, or writer. Some questions might include: what do you know about our topic already? What experiences do you have that might be relevant? What have you done the best on in other parts of the course? What have you been complimented on about your writing in the past from teachers or peers? What kind of reader of other people's papers are you?

Practice Listening

It's too easy to judge someone based on personal assumptions. Assign someone each meeting to take careful notes on everything said, not just what that person thinks is relevant. Many good ideas are lost because we judge the person rather than what he/she says.

Think of your group members, and encourage them to think of you, as yet another source of knowledge just as you might a teacher, a book, or any other source you consult for a paper. Sometimes you can learn the most from someone you think is "wrong" because they can provide a perspective you've ignored.

We won't be able to agree

Group work is messy; you will disagree often. The best groups don't silence disagreement because it's usually in arguing that you can challenge each other to think more about the topic. However, groups that only disagree are no more functional than those that agree to everything. The key is balancing the two. To read more about how to handle disagreements, choose any of the items below:

Assign a Monitor/Mediator

For every meeting, ask someone to keep careful track of the differing opinions and reasons for them. At a certain point in the meeting (or for the next meeting), the mediator's job is to present all the views and try to reach a consensus which includes parts of them. To do this, the mediator must stay out of the arguments for that meeting only.

Decide Whether You Have to Agree

This won't work in every instance, but sometimes you might decide to include the disagreement in the paper itself. Presenting why two different sides of an issue are equally supportable can sometime strengthen the paper, rather than weaken it, depending on the purpose of the paper.

Make Discussion Rules

While arguing about ideas is good, personal attacks are not. Early on, decide as a group what is acceptable behavior toward each other and follow the rule: call someone on it when they go too far.

I don't have time to meet out of class

Fact or Fiction? Sometimes a Fact

Most of us, even if we're very busy, can find two hours to meet with a group. The key is having those two hours in common with other people, which is why, when forming a group, time in common is the first thing to consider. If you are assigned a group, however, this may not be possible. In this case, consider alternative ways of meeting: telephone, e-mail, meetings with some group members, etc. To read more about different alternatives, choose any of the items below:

Everyone on campus can get an e-mail account. You can work on much of the logistical (who needs to do what when) work of a group through e-mail communication. This is also a good way to exchange drafts of the paper, with each person making revisions when the draft gets to them. Or, it can serve as a way to send your "section" before you have a complete draft and/or to exchange research notes. It's not as useful for hashing out ideas or coming up with your thesis for the paper, however.

Talk to your instructor about setting up a chat room through the WWW. Although sometimes frustrating because you will be writing instead of talking, you can use a chat room to do much of the idea generation that e-mail isn't as useful for because of the time lag.

Partial Meetings

Meet in two different groups, with one person in common. Take good notes so that one person can communicate what you decided/talked about to the next group. This can work until the "final" decision stage of what the focus of the paper will be and the final changes to the draft. For these, you'll need probably to meet at least once (for the decision making) or pass the draft around continuously until everyone is ready to sign off on it.

Weekend Meetings

No one loves this option, but if you have no other free time together, you might be able to find a Sunday morning or Friday night when everyone can meet for the one or two meetings that seem as if they must be face-to-face.

I would learn more doing it on my own

While this may seem true because you'd have to do all the work, group work usually allows you to include more research than you could alone, exposes you to perspectives you wouldn't hear otherwise, and teaches you about your own writing strengths and weaknesses in ways writing alone and just getting a response never can. Thus, in group work, you learn more about writing itself, and, if done right, the topic as well.

I'll end up doing all the work

Unless you are unwilling to give up control or speak up for yourself, this shouldn't happen. Although the reality is that some people will try to get away with doing less, the chances of having a completely uncommitted group are rare. As a result, you simply have to watch for the tendency to think you "know better" than others and thus must do it all yourself and/or the attitude that your grade will suffer because everything isn't done the way you want it. To read about how not to do all the work, choose any of the items below:

- If you miss a meeting, or don't do a certain task, you have to type the final paper, buy pizza for the next meeting, etc.

- If more than one meeting is missed or a member consistently fails to do what she/he is supposed to, the group can decide not to include their name on the project. (Check this one with your instructor)

No one, usually, wants to anger his/her peers. When someone isn't doing their work, other group members need to tell them. Many times people who end up doing more than their share do so because they don't complain.

While everyone is not necessarily a great writer in all aspects, they usually know what they do well. Someone may be great at organizing but not be a good proofreader. Someone else might be great a vivid language, but lose their focus. Have group members write what they're best at and/or ask them to read the first draft for specific things they know well. Even if you're good at all aspects, this doesn't mean you can't draw on the others' strengths.

One of the advantages of group work is you learn to read your own and others' writing more critically. Since this is your work too, don't be afraid to suggest and make changes on parts of the paper, even if you didn't write them in the drafting process. Every section, including yours, belongs to everyone in the group. Thus, one way to get a better product without doing all the work yourself is to be a good reader.

What to Expect in Group Work

Several factors we may not always think about when working in a group are vital to a successful group project. You should always establish how your group will handle each of these. To learn more about these factors, choose any of the items below:

Although we might assume productive groups will always be in complete agreement and focused on task, the reality of groups, as we have probably all experienced, is much messier than this. "Ideal" productive groups do not exist. In fact, some of the most productive groups will disagree, spend a lot of time goofing around, and even follow many blind alleys before achieving consensus. It's important to be aware of the rather messy nature of group work.

Student groups will fight--in fact, they should fight, but only in particular ways. Research shows that "substantive" conflict, conflict directed toward the work at hand and issues pertaining to it, is highly productive and should be encouraged. "Personal" conflict, conflict directed toward group members' egos, however, is damaging and unproductive. The lesson is that students need to respect each other. Some groups decide to negotiate respect by making rules against inappropriate comments or personal attacks. When a damaging instance arises in a certain situation, any group member can immediately censor back the comment by saying "inappropriate comment."

Socializing

Of course, groups will not continually argue nor will they continually stay on task. Socializing, joking around, or telling stories are a natural part of group interaction and should be encouraged. It is primarily through "goofing off&qout; that group members learn about each other's personalities, communication styles, and senses of humor. Such knowledge builds trust and community among the members. Although groups should be counseled not to spend inappropriately long amounts of time simply gossiping or telling stories, they should also realize the importance and influence such interactions can have on achieving a group identity that all members come to share.

Wrong Decisions

Group members should be aware of and comfortable with the frequently frustrating reality of making the wrong decisions. Making mistakes, trying out options that don't work, and so on are not "a waste of time." In any creative situation, particularly in writing, trying out unsuccessful options is frequently the only way to discover what needs to be done. Although such frustrations take place even in individual contexts, they are particularly hard to negotiate in a group context because our immediate instinct is to blame another group member for a faulty suggestion. Students should be aware that all time spent on a task is productive even if it does not lead to any tangible product.

Unequal Commitments

In a perfect world, everyone would have as much time and desire in a group as others to create the best paper possible, but the reality is some people are procrastinators or care more about their grades in certain classes. Expect this and make contingencies for it by deciding early on what the "penalty" will be for those who miss meetings or fail to pull their weight.

Choosing Group Members

Sometimes in class assignments, you won't be able to choose your group, but if you have this option or are forming a group for your own purposes (e.g. study groups for exams), be careful of how you choose members. To read more about how to construct a group, choose any of the items below:

Time in Common to Meet

You'll want to have at least a two-hour chunk of time that everyone in the group can meet each week. While you'll probably not meet every week, everyone should be willing to keep this time free during the group project. If you plan to gather to write the text together, you'll need much larger chunks of time toward the end of the project.

Individual Strengths and Weaknesses

Any collaboratively written paper will include research, idea-generating, and writing abilities. For other groups, such as study groups, only idea-generating or understanding of class material may be relevant. As you ask people to join your group, have a specific reason why they would "add" to the group mix in terms of abilities. Choosing your friends is not always the best way to get a "balanced" group. For example, your friends might all be good at research but all lack writing skills.

If you're doing a group paper or studying together, including a diversity of people might be a real asset. For example, gender diversity may or may not be relevant depending on the topic. Past course work or job experience may or may not be relevant. Prepare a list of the types of diversity that may help strengthen your paper because of the different perspectives or types of expertise people can bring to the group.

Next to enough time to meet, this criterion is most important. Try to choose group members who have an equal investment in the project or study group as you do. It's unfair to invite someone because you think they'll do most of the work; it's equally unfair to you to invite someone you like but who will probably miss meetings or procrastinate.

Guidelines for Group Work

The members of student groups may benefit from keeping some common-sense rules and aphorisms in mind as they come to collaborate.

Collaboration teaches us what we know how to do , not just what we know. Collaboration teaches method. The activities of collaboration are as important as the material results.

Collaboration works best when it is apparent--when you know that you are collaborating. A certain amount of formality (e.g., established meeting times, a recorder to take minutes perhaps, a group monitor) is called for.

Collaboration succeeds when everybody succeeds--individual members as well as the group as a whole.

Collaboration is a key responsibility in the class experience--it means being involved in the teaching of the course.

No one ever knows how a collaborative activity will turn out.

Initial Decision-Making

This section provides suggestions about the types of decisions any group should make before getting into the work on a paper itself in order to prevent future problems.

Where many groups go wrong is not being clear about expectations from the onset. Problems are much easier to deal with when you discuses their possibility in the abstract rather than when they involve individual people and feelings. As such, making the following decisions early on can help deflect feelings of personal attack later and also help organize the group.

Agree on a Meeting Format

While many groups will (and should) spend time socializing, talking about class, etc., it's helpful to set up expectations for how much of this type of talk should/can occur during a meeting. Also, because of how much typically gets said during meetings, you need a way to keep track of what occurred and plan for the next meeting. For instance, you should:

- Appoint a secretary for each meeting

- Plan for the next meeting (set an agenda) at the end of each meeting

- Plan a short amount of time at the beginning of each meeting for chatting and appoint someone to get the group "started" after that time has passed

Construct Rules for Discussion

Although it usually seems unlikely in the beginning, a healthy disagreement can easily turn nasty when people are invested in a topic. Decide early on what will be considered inappropriate comments and make sure someone monitors these in later meetings. Here are some rules to consider:

- No personal attacks on a person's intelligence, background, way of speaking, etc.

- No yelling; all disagreements should be kept in a rational tone

- No name calling

- If a person objects to a comment directed at them, the conversation stops there, no matter anyone's opinion of the objection

- Out of Line Comments: "That's a dumb idea;" "You don't know what you're talking about;" "It figures a man/woman would say that"

Construct a Timeline

It's very easy to get lost in people's individual schedules week to week and put off certain tasks "just this time." Also, it's easy for a group project to seem "huge" until the tasks are broken down. For these reasons, it's useful to decide what tasks need to be done and when they need to be finished in order for the group to meet its final deadline.

Make a schedule and keep to it. This will also help group members monitor each other so that someone isn't stuck with all the work at the end. Consider the following:

- When will a final decision on the topic/focus be made?

- What kinds of research do we need to do? Who will do what? By when?

- When will people report back on research? What notes should they write up for others? By when?

- When must a final decision on the major point (thesis) of the paper be made?

- When will the paper be drafted initially?

- When will the comments/suggestions for revision be completed?

- When will the revisions be done by?

- When will the final proofreading occur?

Agree on Penalties for Missing Meetings or Deadlines

Although it would be great if this weren't true, the reality is some people are going to miss meetings and deadlines; some might even try to get others to do their work by not completing tasks. Groups need to be prepared for these contingencies by constructing rules and their consequences that can be applied later if individuals "drop the ball." Consider the following:

Discuss What Each Member Brings to the Group

While you might know your other group members as friends, you probably don't know as much about them as students as you might think. A very productive topic for the first meeting, after all the logistics have been worked out, is to discuss what individual members' strengths and weaknesses are. In short, have everyone conduct a "personal inventory" and share it with the other members on their experiences relevant to the collaborative assignment. Doing this also helps alleviate the feeling that some group members are "smarter" or "know more" than others. Everyone has strengths they bring to the group; we're simply not always aware of them. Consider the following:

- What's your previous experience with the topic?