Retail distribution evaluation in brand-level sales response models

- Original Article

- Published: 25 March 2022

- Volume 11 , pages 366–378, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Antonis A. Michis ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2610-8955 1

2915 Accesses

6 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The effectiveness of a product’s distribution network in retail stores is an important consideration for marketing managers. An effective distribution network typically covers a large number of stores in the geographic area of a market and establishes a continuous presence in the top-selling outlets of a product category at the same time. This study proposes a semiparametric, brand-level version of the SCAN*PRO sales model, to evaluate the impact of retail distribution changes on sales. The model is estimated using the iteratively reweighted least squares method and provides the following outputs: (i) least squares coefficient estimates for the price and promotional drivers in the model specification and (ii) two-dimensional plots of the nonmonotonic relationship between the weighted distribution and sales. The proposed model can be estimated with commonly available retail scanning data and is demonstrated using three laundry detergent brands from The Netherlands.

Similar content being viewed by others

Modeling total distribution velocity

A comparison of semiparametric and heterogeneous store sales models for optimal category pricing.

Planning Merchandising Decisions to Account for Regional and Product Assortment Differences

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The establishment and monitoring of an effective product distribution network of stores is a crucial part of the marketing strategy of an organization. The success of marketing activities such as new product introductions, promotions and temporary price reductions strongly depends on the existence and development of an effective distribution network. Such a network should provide access to a large number of retail outlets while covering the most important stores (in terms of sales volume) within the boundaries of the market. However, with the growing bargaining power of large retailers, manufacturers are nowadays required to allocate more financial resources in order to secure their products’ presence in the important retail chains of a market, which constrains the scale of the distribution coverage that a company can afford.

Effective distribution management is even more complex for multinational corporations that distribute products in countries where market infrastructures, retail technology and shoppers’ habits greatly differ from the North American and Western European standards (e.g., emerging markets). Guissoni et al. ( 2021 ) note that in emerging markets, the cost of expanding the retail distribution network of a brand represents a considerable percentage of consumer packaged goods sales. Frequently, one of the main challenges for a multinational corporation in these environments is to oversee the proper implementation of its marketing strategy by the independent distributors (Arnold 2000 ). This is due to the underdeveloped retail infrastructures and logistics systems that characterize these markets (Sharma et al. 2019 ).

Reibstein and Farris ( 1995 ), Krider et al. ( 2005 ), Krider et al. ( 2008 ), and Friberg and Sancturary ( 2017 ) emphasize that there is a cause and effect relationship between sales/market shares and distribution, which can be both highly nonlinear and difficult to estimate. Knowledge of the shape of this relationship, commonly known as the velocity curve (Hirche et al. 2021b ), provides marketing managers with a better understanding of the bi-directional causality between market share and distribution, as well as, the structure of the retail distribution environment. Furthermore, understanding the product characteristics that are associated with over- or underperformance relative to the velocity curve is an important consideration for marketing managers, particularly in cases related with SKU discontinuations, additional marketing support or new SKU introductions (Wilbur and Farris 2014 ; Hirche et al. 2021a ).

The sudden disruptions on consumer demand imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic had a negative impact on supply chain performance, with important implications for retail distribution management. For example, Pantano et al. ( 2020 ) note that consumers tend to cope with one time stock-outs by switching stores or brands, while the emergence of stockpiling behaviour should be expected to impact price sensitivity. Furthermore, the lower accessibility of store premises due to government imposed restrictions (e.g. lockdowns) and the increase in consumers’ health concerns can result in the adoption of alternative distribution channels (Erjavec and Manfreda 2022 ) and consumption patterns by consumers (Park, et al. 2022 ), as is the case with online shopping and/or switching to small grocery stores that are more accessible in terms of spatial proximity.

Understanding the market outcomes associated with these changes and developing appropriate marketing actions requires the development of analytical tools that are able to analyse the effects of marketing instruments (distribution, price, promotions) jointly. The sales response model proposed in this study therefore provides a managerial tool for continuously evaluating and monitoring the effectiveness of a product’s distribution network, jointly with the other instruments in the marketing mix. It is based on a semiparametric version of the SCAN*PRO sales model, which was designed for commercial applications and is particularly well suited for scenario analysis (see Leeflang et al. 2000 ; van Heerde et al. 2002 and Wittink et al. 2011 ). However, unlike the standard version model, it incorporates handling distribution as an additional explanatory variable that enters the model in nonparametric form.

Furthermore, our analysis contributes to the growing semiparametric modelling literature in marketing, which addresses several important questions that cannot be adequately addressed with parametric methods. Hruschkla, ( 2002 ), Steiner et al. ( 2007 ), Van Heerde ( 2017 ) and Guhl et al. ( 2018 ) note that semiparametric models are generally useful for studying the functional form characterising the relationship between marketing inputs and outputs, not only with respect to pricing but also in other areas of marketing where interactions exist. Even though the shape of the velocity curve (convex, concave, S-shaped, linear) is an important generalisation for marketing managers, it is not commonly incorporated in the sales response models frequently used by marketing managers. In this context, the semiparametric sales response model proposed in this study aims to address the following related gaps in the marketing literature:

It provides semiparametric estimates of the nonlinear sales–distribution relationship, which facilitates understanding of the expected returns from possible distributions expansions.

It enables the joint evaluation of all the main marketing drivers (e.g. price changes, promotions) that can increase performance over and above the levels predicted by the sales–distribution relationship.

It can be used for “what-if” scenario analyses, which are important for planning the efficient allocation of marketing resources.

It can be calibrated using commonly available scanning data, which facilitates its application by marketing managers.

The rest of the article is organized as follows. A review of the existing literature on retail distribution modelling is provided in the “ Literature review ” section, including the main shapes of the velocity curve that are likely to be encountered in retail markets. The proposed model and the associated semiparametric estimation method are explained in the “ Methodology ” section. In the “ Empirical study ” section, an empirical study, which uses three laundry detergent brands from the Netherlands, is presented to demonstrate the marketing insights associated with the proposed model. The “ Practical implications ” section elaborates on the practical implications associated with the empirical study and the “ Conclusions ” section concludes with a discussion of the main findings of the study.

Literature review

Increases in the retail distribution coverage of a product tend to be associated with relatively large sales (and market share) increases during the initial stages of a product’s life cycle. For this reason, Hanssens et al. ( 2001 , p. 347) emphasize that distribution elasticities should be expected to be greater than one. Progressively, as more stores are added to the distribution network of a product, decreasing or increasing returns could occur, and the sales impact might vary (see Lilien et al. 1992 , p. 435). This suggests a nonlinear relationship between the market response variables and distribution.

A related study by Farris et al. ( 1989 ) showed that the market share can be a convex function of the distribution; and Reibstein and Farris ( 1995 ) proposed several other nonlinear shapes of the relationship that are theoretically possible, such as concave and S-shaped functions. In addition, Frazier and Lassar ( 1996 ) showed that the distribution levels of brands within a product category can vary considerably since distribution intensity tends to be influenced by several moderator effects such as manufacturer channel practices, brand strategies and retailer credible commitments (e.g., contractual restrictions). These effects further complicate the impact of distribution changes on sales.

Bronnenberg et al. ( 2000 ) concentrated on feedback effects and showed that during the growth stage of a repeat-purchase product, the formation of market shares is influenced by a positive feedback mechanism with distribution. This is because retailers’ distribution decisions consider the prior market share performance of brands. The authors also found evidence of a time window that is crucial to the establishment of market shares. Beyond this time window, the feedback mechanism between distribution and market share changes weakens, retailers are less prone to distribution changes and late entrants find it difficult to seize considerable market shares.

Nishida ( 2017 ) provided further evidence for the existence of a nonmonotonic, inverted U relationship between the density of one’s own outlets and the sales performance per outlet in a market. First, through a detailed econometric study, the author found (on average) a 115.3% market share advantage for first entrants over later entrants in the Japanese convenience store industry. Of this significant advantage, 101.7% was due to a higher number of outlets (higher outlet share in the market), and the remaining 13.6% was due to higher sales per store.

Second, further analysis of the higher sales per store advantage (13.6%) revealed that during the early stages of a brand’s distribution development, the addition of new stores increases sales per outlet. However, after a certain threshold, sales per outlet start to decrease as new stores are added. This is due to the trade-off between the positive brand advertising effect associated with repeated purchases in one’s own outlets and the negative cannibalization effect associated with more intense competition between these outlets.

Sharma et al. ( 2019 ) examined the importance of retail distribution strategies in emerging markets that are characterized by underdeveloped road infrastructures and low levels of retail store penetration. Τo study the price and retail distribution strategies of manufacturers, the authors developed a competitive model for the insecticide market of India, where manufacturers compete across multiple channels and product forms.

The econometric results of this study suggest that distribution exerts a considerable influence on profits since ignoring distribution in the competitive model can result in serious profit overestimation (by 7% to 55%). Furthermore, the observed price and distribution strategies in the market suggest the existence of competition rather than collusion among manufacturers. It is also worth mentioning that the research by Tenn and Yun ( 2008 ) showed that price elasticity estimates can be significantly biased when limited retail distribution is not accounted for in demand models.

Hirche et al. ( 2021b ) proposed a metric for measuring deviations from the velocity curve, generated by the well-known Reibstein and Farris model (Reibstein and Farris 1995 ). These deviations were subsequently regressed on product related characteristics to identify the factors that generate performance over and above the levels predicted by the velocity curve. According to the author’s findings larger packs, private label status and medium-range price levels contribute to improved market share performance. Deviations from the velocity curve of a brand were also used by Hirche et al. ( 2021a ) in the context of a machine learning application, to identify the SKU characteristics that can explain these deviations. The proposed machine learning method was able to predict correctly 83% of the cases as either over-, in-line- or underperforming relative to their velocity curves.

In a recent study of the distribution-market share relationship for an emerging market, Guissoni et al. ( 2021 ) found that the convexity of the velocity curve varies by channel type, the economic situation in the country and the market share position of the brands under consideration. Convexity was found to be higher in the self-service (e.g. major chain stores) than in the traditional full-service (small owner-managed stores) channel. Furthermore, increases in distribution were found to be more effective in the self-service channel during times of economic decline and the degree of convexity in this channel was found to be higher for high-share brands.

Previous empirical studies that have incorporated distribution variables into various forms of market response models include the following: log-linear sales models (Brissimis and Kioulafas 1987 ), new product diffusion models (Jones and Ritz 1991 ), VAR market share models (Bronnenberg et al. 2000 ), EGARCH market share volatility models (Varkatsas 2008 ) and logit choice models (Bucklin et al. 2008 ). Krider et al. ( 2005 ) suggested an alternative methodology based on state-space diagrams to explore the lead–lag relationship between distribution and demand. This method is particularly suited for time series that are short in length and nonstationary. It was further extended in Krider et al. ( 2008 ) to assist econometric modelling decisions and improve inferences (e.g., regarding the speed of the market response) when long time series are available.

In this study, a semiparametric modelling method based on the SCAN*PRO sales model is used. Using locally weighted scatterplot smoothing in the context of the backfitting-algorithm, the proposed model generates two-dimensional plots of the nonlinearities characterizing the sales–distribution relationship. Apart from facilitating the visual inspection, the addition of a distribution variable also improves the specification of sales response models and enables marketing managers to perform market response predictions for given levels of distribution.

Following the analysis by Reibstein and Farris ( 1995 ), in the remaining paragraphs of this section we explain the main shapes of the sales/market share-distribution relationship that are likely to be encountered in retail markets:

Convex : This shape of the sales/market share-distribution relationship should be expected in the following cases: (i) when market share is not only a cause but also an effect of retail distribution and (ii) when the structure of the retail network in the market is such that there are a few large stores that stock many brands and many small stores that stock only the leading brands. This pattern of distribution effects is further amplified when search loyalty in the market is low. Friberg and Sancturary ( 2017 ) provided similar insights with respect to this shape of the distribution curve. Specifically, competing with successively fewer products (smaller assortments) in smaller stores as distribution expands, combined with a lower resistance to compromise by the consumers contributes to a convex relationship. More examples of this relationship are reported by Wilbur and Farris ( 2014 ).

Concave : This shape of the sales/market share-distribution relationship is more likely to exist when: (i) all stores carry approximately the same brands, but the distribution policy of the manufacturer concentrates on the stores with the greatest potential (initial handlers with higher shares); (ii) initial stores engage in significant in-store support activities that are not matched by later handlers; and (iii) brand loyalty is high in initial handlers, while subsequent stores in the brand’s distribution network are characterised by non-loyal consumers; (iv) a trade-off exists between the positive brand advertising effect associated with repeated purchases and the negative cannibalization effect associated with more intense competition between handlers (Nishida 2017 ).

S-shaped function : This shape of the sales market/share-distribution relationship is more frequently encountered when the ability of the brand to attract consumers tends to be associated with its availability and only a proportion of the customers is loyal. It can also be encountered in retail environments where in-store support programs and some levels of consumer loyalty co-exist. Examples of S-shaped functions are provided by Hirche et al. ( 2021a ).

Linear function : A linear sales/market share-distribution function tends to exist when distribution expansion provides access to consumers who prefer the brand and these distribution increases are associated constant within-store shares in the new handlers. Examples of linear market share-distribution functions are provided by Hirche et al. ( 2021b ).

Methodology

Variability in distribution.

A common problem in studies of distribution effectiveness concerns the lack of sufficient variation in the aggregated measures of distribution that are usually available to marketing managers. This is especially true for mature and well-established brands that are already available for purchase in the most important stores of a product category. As a result, there is limited scope for further development of the distribution network, and distribution aggregates exhibit only limited variability.

To overcome this limitation, Bucklin et al. ( 2008 ) used buyer-level data and the distances between buyers and car dealers in order to construct three distribution intensity measures. The resulting cross-sectional variation enabled an examination of the impact of the distribution intensity on market outcomes, which otherwise would not be possible with aggregated distribution variables.

In this study, a different approach is used. Detailed SKU level data are combined in order to create panel datasets that can be used for estimating brand level sales response models. The cross-sectional units in the panel dataset consist of all the SKUs included in a brand portfolio, and the time period is weekly observations. For each brand portfolio examined in this study, there were several SKUs available in the market that consisted of new and established SKUs. There were also SKUs towards the end of their life cycle that were gradually being withdrawn from the market. Since most SKUs in each brand portfolio differed in terms of their life cycle stage, they also exhibited different levels of distribution intensity. Consequently, incorporating all the SKUs in a common (panel data) sales response model provides sufficient variation to nonparametrically estimate the sales–distribution relationship at the brand level.

Fast-moving consumer goods manufacturers typically develop their retail distribution strategies at the brand level, and policy decisions with regards to distribution are then applied to all the SKUs in the respective brand portfolio. Therefore, by incorporating all the SKUs of a brand in a common modelling framework, it is possible to identify: (i) the shape of the sales–distribution relationship and (ii) whether the distribution strategy of the brand was successful in increasing sales.

A semiparametric brand level sales response model

Nonparametric and semiparametric models have been previously used in the marketing literature as more flexible alternatives to parametric models. This is especially true for cases where the relationships between the marketing variables are characterised by nonlinearities. Previous studies using nonparametric techniques in marketing applications include models for market shares (Hruschkla 2002 ), sales and price effects (Kalyanam and Shively 1998 ; Van Heerde et al. 2001 ; Sloot et al. 2006 ; Martínez-Ruiz et al. 2006 ; Steiner et al. 2007 ; Michis 2009 ), brand choice (Abe 1995 ; Guhl et al. 2018 ), media usage (Rust 1988 ) and sales forecasting (Michis 2015 ).

The inflexibility of parametric models can be especially problematic in cases of incorrect model specifications, which provide inconsistent parameter estimates and therefore lead to misleading conclusions regarding marketing effectiveness (Albers 2012 ). In contrast, nonparametric models do not impose any strict restrictions concerning the form of the joint distribution of the model’s data. However, the convergence rate of nonparametric estimators is generally slower and the precise estimation of regression surfaces requires significantly larger samples (Van Heerde 2000 ). This is not the case for correctly specified parametric models that are asymptotically efficient (maximal convergence rate to the true parameter values).

Semiparametric models combine elements of the two modelling methods in an attempt to benefit from the flexibility of nonparametric models and the efficiency of parametric models. However, as a midway solution they are not as flexible as nonparametric models and not as efficient as parametric models. Since they include both a nonparametric and a parametric component, the dimensionality of the nonparametric function is reduced, which also reduces the curse of dimensionality problem in the estimation procedure (Van Heerde 2000 ).

To evaluate the sales–distribution relationship in this study, a semiparametric extension of the SCAN*PRO model is proposed as follows:

where \(S_{it}^{j}\) : sales volume of SKU \(i\) in brand portfolio \(j\) in period \(t\) ; \(P_{it}^{j}\) : average price per unit of SKU \(i\) in brand portfolio \(j\) in period \(t\) ; \(\overline{P}_{t}^{j}\) : weighted average price of brand \(j\) in period \(t\) ; \(P_{it}^{g}\) : average price per unit of SKU \(i\) in competitive brand portfolio \(g\) in period \(t\) ; \(\overline{P}_{t}^{g}\) : weighted average price of competitive brand \(g\) in period \(t\) ; \(T\) : time trend variable; \(M_{k}\) : monthly indicator variable, where \(M_{k}\) = 1 if the observation is for month \(k\) and \(M_{k}\) = 0 otherwise; \(I_{i}^{j}\) : indicator variable for SKU \(i\) in brand portfolio \(j\) , where \(I_{i}^{j}\) = 1 if the observation is for SKU \(i\) and \(I_{i}^{j}\) = 0 otherwise; \(D_{it,l}^{j}\) : indicator variable for the use of promotional items or materials for SKU \(i\) in period \(t\) for feature-only ( \(D_{it,1}^{j} = 1\) ), display-only ( \(D_{it,2}^{j} = 1\) ), feature and display ( \(D_{it,3}^{j} = 1\) ) and special promo packs ( \(D_{it,4}^{j} = 1\) ); \(WD_{it}^{j}\) : weighted (handling) distribution of SKU \(i\) in brand portfolio \(j\) in period \(t\) (the percentage of retail outlets in the store population where SKU \(i\) is available for sale, weighted to the product category’s turnover volume within stores); \(a\) , \(\delta_{k}\) , \(\xi_{r}\) , \(\beta_{i}\) , \(\beta_{g}\) , \(\gamma_{l}\) and \(d\) : regression coefficients; and \(\varepsilon_{it}^{j}\) : error term of the model.

This specification differs from the standard SCAN*PRO model (Andrews et al. 2008 ) in two important aspects: (i) the weighted distribution ( \(WD_{it}^{j}\) ) is included in nonparametric form ( f ) as an additional explanatory variable in the model and (ii) observations vary across SKUs ( i ) and weeks ( t ). In contrast, in the standard SCAN*PRO model, observations vary across stores and weeks. As explained above (see “Variability in distribution” section ), the differences in the distribution intensity across the different SKUs in each brand portfolio provide sufficient variation in order to nonparametrically estimate the sales–distribution relationship at the brand level. Furthermore, as is common for panel data models with fixed effects (Allison 2009 ), separate indicator variables ( \(I_{i}^{j}\) ) were included in the model for each SKU \(i\) in the dataset that is included under brand portfolio \(j\) .

The semiparametric model in Eq. ( 1 ) can also be extended to include additional nonparametric components as follows:

Consequently, in addition to weighted distribution ( \(WD_{it}^{j}\) ) Eq. ( 2 ) now includes a second nonparametric term for own-price effects ( \(P_{it}^{j} /\overline{P}_{t}^{j}\) ). Empirical estimates of the shapes of these partial regression functions are presented in the “Own-price flexibility ” section, using three laundry detergent brands from the Netherlands.

Backfitting algorithm and scatterplot smoothing

Model (1) can be estimated with the iteratively reweighted least squares method, which can be combined with the backfitting algorithm developed by Hastie and Tibshirani ( 1990 ) in order to estimate the nonparametric part of the model. This algorithm proceeds in three stages:

The least squares estimation of the parametric part of the model.

The partial residuals obtained from step I are then used in a scatterplot smoothing procedure against the weighted distribution variable that enters the model in nonparametric form. This generates a first estimate of its partial regression function \(\hat{f}\left( {\log ND} \right).\)

The partial regression function generated in step II is then replaced in the regression model, and steps I and II are repeated several times until the estimates for the partial regression function stabilize (convergence).

Consequently, the backfitting algorithm involves an iterative smoothing procedure of the partial residuals against estimates of the partial regression function. In this study, scatterplot smoothing was performed using the local polynomial regression method.

The estimation procedure using the backfitting algorithm and the associated smoothing procedure are best explained by considering the semiparametric regression model

and the corresponding linear regression model with transformations in means

The backfitting algorithm starts by estimating the transformed model with the least squares method, which produces an initial estimate of the partial regression function \(\hat{f}_{r}^{0} = b_{r} (x_{ir} - \overline{x}_{r} )\) . The partial residuals, which retain the relationship between \(y_{i}\) and \(x_{ir}\) but remove from \(y_{i}\) its linear relationship to all the other explanatory variables, can be written as follows:

The backfitting algorithm then proceeds to smooth the partial residuals against the indicator variable \(x_{ir}\) that enters the regression model in nonparametric form. This first application of the smoothing procedure generates a first estimate of the partial regression function \(\hat{f}_{r}^{1}\) , which is then replaced in the regression model.

The partial residuals are calculated again and smoothed against the indicator variable \(x_{ir}\) in order to generate a second estimate of the partial regression function \(\hat{f}_{r}^{2}\) . This new estimate is again replaced in the regression model, and the procedure is iteratively repeated until the partial regression function estimates stabilize and the iteration procedure converges (see Fox 2000 , p. 32).

Consequently, the iterative scatterplot smoothing procedure is central to the operation of the backfitting algorithm. In the empirical applications of the next section, smoothing was performed with the local polynomial regression method, which is frequently employed in the context of the backfitting algorithm. Given a sample of observations for variable \(x_{ir}\) , this method starts by fitting the following polynomial equation around a focal point \(x_{0r}\) through a weighted least squares procedure that minimizes the weighted residual sum of squares \(\sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{n} {w_{i} E_{i}^{2} }\) :

The fitted value at point \(x_{0r}\) is equal to \(\hat{e}_{r} |x_{0r} = A\) . The same estimation procedure is then performed at several other focal points across the sample of observations in order to generate fitted values and form the smooth function associated with indicator variable \(x_{ir}\) . In this study, the weights used in the weighted least squares estimation procedure were based on the following kernel function, which gives greater weights to observations near the focal point \(x_{0r}\) :

The smoothness of the partial regression function can be controlled with the bandwidth or smoothing parameter ( \(h\) ). In this study, the nearest neighbourhood method was used, based on which the bandwidth parameter is adjusted to include a fixed portion of the data around each focal point. The final value of the bandwidth parameter in each application was selected based on the procedure suggested by Fox ( 2008 , p. 482). This procedure starts with cross validation in order to obtain an initial estimate of the parameter. It then proceeds with visually guided adjustments in order to achieve the smallest value of the parameter that provides a sufficiently smooth fit to the data.

The contribution of indicator variable \(x_{ir}\) to the semiparametric model can be tested with an F test (see Fox 2000 , pp. 34–35). This test is formed by using the differences in the residual sum of squares (RSS) and degrees of freedom between two models: one that includes the indicator variable \(x_{ir}\) and has \(df_{1}\) degrees of freedom (the full model) and one that excludes the indicator variable \(x_{ir}\) and has \(df_{0}\) degrees of freedom. The test has the following form, where \(n\) refers to the sample size:

Empirical study

The semiparametric sales response model in Eq. ( 1 ) was estimated for three leading detergent brands in the Netherlands. Due to confidentiality restrictions, the names of the brands cannot be provided. The dataset was kindly provided by The Nielsen Company and consists of weekly observations for all the SKUs included in each brand portfolio. For each SKU, Nielsen collects weekly scanning observations for all the variables included in model (1) using a representative sample of grocery stores in the Netherlands that also includes the major supermarket chains. Brand level aggregated data are derived through contemporaneous aggregation of the SKU level data. There are 120 weekly observations for each SKU in the dataset that cover the period from week 38 of 2002 to week 53 of 2004.

In order to incorporate a weighted distribution measure in the proposed modelling framework, we have utilised the weighted distribution metric produced by the Retail Measurement Services of The Nielsen Company in the analysis. To calculate this metric, numeric distribution is weighted to the product category’s turnover volume within stores (PCV). Similarly with numeric distribution, it is also expressed as a percentage and it is available for the same time periods and SKUs in the database.

As a weighted distribution metric, it provides an indication of the importance of the stores (in terms of turnover) into which a brand or SKU is available for sale. This is an important consideration for marketing managers since brands and SKUs can be associated with high numeric distribution levels in the market but still be listed in stores that do not account for a large percentage of the particular product category’s turnover. In such cases, the respective weighted distribution levels of the brands (or SKUs) will be low.

As explained in the “Variability in distribution” section, the brand level model in Eq. ( 1 ) will not be estimated using aggregated brand level data that exhibit limited variability in their retail distribution. In contrast, the SKUs are used as cross-sectional units in a panel dataset since each brand portfolio encompasses several SKUs that differ in their distribution development over the period examined in the dataset (e.g., new vs. established SKUs). In this way, sufficient variability is achieved for the estimation of the partial regression function associated with the weighted distribution in model (1). All brand portfolios examined in this study include both new and established SKUs, which permits the examination of the sales–distribution relationship throughout the range of values associated with the weighted distribution.

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for the main variables associated with each brand. Each brand portfolio includes at least 8 different SKUs, and the minimum value of the weighted distribution variable in all cases is zero. This suggests the existence of new products in each brand portfolio (introduced in the market after week 38 of 2002) or the withdrawal of established SKUs from the market (before week 53 of 2004). Furthermore, in all cases, the maximum value of this variable exceeds the 83% distribution level, suggesting the existence of established and well distributed SKUs in the market.

There is also considerable variability in prices (at the average SKU and weighted average brand levels), both within each brand portfolio (e.g., due to the existence of large and small packs) and across brands (e.g., brand 2 vs. brand 3). There are also considerable differences in terms of the average sales volume between the 3 brands and for each brand all the available types of promotional activities were used (feature, display, feature & display and special packs). It is therefore of interest to examine the impact of distribution changes on sales while controlling for the effect of the other marketing activities.

Estimation results

For all brands, model (1) was estimated with the backfitting algorithm using a smoothing parameter of \(h = 0.1\) in the local polynomial smoothing procedure of stage II. The estimation results are presented in Table 2 . In all cases, the model provided a good fit to the data, as demonstrated by the high (adjusted) R 2 values. As a result of their detailed marketing mix parameter specifications, sales response models like the SCAN*PRO model are frequently associated with high R 2 values (see for example Brissimis and Kioulafas 1987 , Andrews et al. 2008 and Kopalle et al. 1999 ).

All linear coefficients have the expected sign and in most cases are statistically significant at the 1% or 5% level. Similarly, the weighted distribution variable provided a statistically significant contribution in all models based on the results of the F test for the significance of the smoothing terms. The explanatory variables corresponding to nonstatistically significant coefficients were included in the final model specifications based on the F test for the joint significance of all coefficients. All brands are price elastic with brands 1 and 2 exhibiting the highest price sensitivity. Furthermore, in all cases the signs and magnitudes of the estimated own and cross-price elasticities are consistent with the average SCAN*PRO model parameter estimates reported by Leeflang et al. ( 2000 ).

With respect to the promotional variables, the results differ by brand. The “feature and display” promotional indicator ( \(D_{it,3}^{j}\) ) provided the highest impact on the sales of brands 1 and 2, which is consistent with the SCAN*PRO model estimation results reported by Foekens et al. ( 1994 ), while the indicator variable for “promotional packs” ( \(D_{it,4}^{j}\) ) provided the highest impact on the sales of brand 3. All the coefficients in Table 2 are statistically significant, except from the “Display” coefficients ( \(D_{it,1}^{j}\) ) for brands 2 and 3. The coefficient for the “feature and display” promotional variable ( \(D_{it,3}^{j}\) ) is also statistically significant for brand 3, albeit at the 10% significance level.

For brand 3, the “Promotion” variable ( \(D_{it,4}^{j}\) ) which concerns the use of special promo packs has the highest coefficient. This specific promotional activity is also important for brands 1 and 2, since it provided the second highest coefficient among the four types of promotional activities included in the respective models.

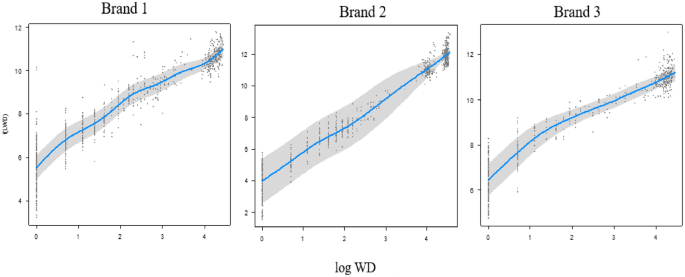

The weighted distribution ( \(WD_{ijt}\) ) partial regression functions generated by the estimation procedure are presented in the three panels of Fig. 1 . The shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals for the estimates. Each graph demonstrates the sales volume development for different levels of the weighted distribution while holding the other marketing activities constant. These partial regression functions can be used to monitor the expansion of brand distribution networks and to identify the inclusion of less important stores in the retail network of a brand at higher levels of distribution coverage.

Weighted distribution partial regression functions

For brand 1, the shape of the curve is slightly concave. Even though the weighted distribution function is approximately linear during the initial stages of its distribution development, there are indications of decreasing returns in its partial regression function when moving progressively to higher weighted distribution levels, eventually providing a slightly more concave response function compared to brand 2. For brand 2, the shape of the weighted distribution partial regression function suggests that the relationship with sales is mostly linear, even at higher weighted distribution levels. This type of positive sales effect tends to be observed when distribution expansions are associated constant within-store shares in the new handlers as explained in the “ Literature review ” section.

With the introduction of a new brand into the market, an initial period of rapid distribution development starts with a high impact on sales. For established brands, a concave sales–distribution relationship at higher distribution levels suggests the presence of decreasing returns due to the addition of less important stores (in terms of sales volume) in the distribution network. In Fig. 1 , this is most evident for brand 3. Despite an increasing trend during the early stages of its distribution expansion, there are indications of decreasing returns in its partial regression function when moving to higher weighted distribution levels, thus giving rise to a concave weighted distribution function. A similar non-monotonic concave function was also reported in an empirical study by Nishida ( 2017 ). This finding suggests that the SKUs of brand 3 could have benefitted from a better selection of stores as part of the brand’s distribution network expansion at higher distribution levels, or from the introduction of in-store support activities.

As noted in the " Literature review " section, the slightly concave shape of the weighted distribution partial regression function is also indicative of support activities by initial handlers with higher shares that were not matched by latter handlers. Consequently, a possible course of action for the marketing manager of brand 3 would be the introduction of support programs in later handlers, in order to increase the brand’s sales returns.

For cases similar to brand 3 above, store evaluations for inclusion to the brands’ distribution networks can be improved when supported by indicators of the sales importance of the different outlets. Examples of such indicators include: the category’s sales volume, the sales volumes of other similar product categories or store turnover information from a retail census database. Furthermore, engaging in channel practices like supporting retailers’ investments (e.g. training of the sales personnel) and the introduction of in-store promotional activities can also increase the sales potential of the stores, towards levels that are more compatible with a linear shape of the sales–distribution relationship.

Own-price flexibility

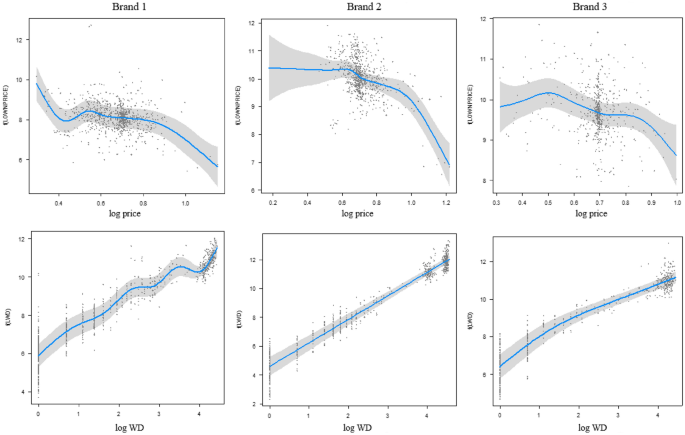

Table 3 includes the estimation results for model (2) above that includes nonparametric functions for both the own-price and the weighted distribution variables. It can be observed that for all brands, both variables provided statistically significant contributions based on the results of the F test for the significance of the smoothing terms. And the coefficient estimates for the parametric terms of the model are similar to those in Table 2 , where only the weighted distribution variable is included in nonparametric form.

The shapes of the partial regression functions generated by the estimation procedure are presented in the six panels of Fig. 2 . The own-price partial regression functions included in the first row provide some interesting insights. First, for all brands the estimated sales–price partial regression functions are highly nonlinear, which provides further support for the suitability of the semiparametric model specification. Second, in all cases a negative slope is observed that is consistent with economic theory. Third, for all brands there are indications of saturation effects in the shapes of the curves, since beyond a certain price reduction level (very large price discounts) the sales response is significantly reduced. Similar shapes and saturation effects were also reported by Van Heerde et al. ( 2001 ) and Hirche et al. ( 2021a ). The only exception is the lowest price range in the case of brand 1. It also worth mentioning that the lower price segment of the own-price partial regression function for brand 2 is associated with a particularly large confidence interval and should therefore be used with caution.

Own price and weighted distribution partial regression functions

With respect to the weighted distribution partial regression functions in the second row of Fig. 2 , it can be observed that the shapes of the sales–weighted distribution relationships are very similar to the ones presented in Fig. 1 (except from some small fluctuations in the response curve for brand 1) and the adjusted R 2 values are very similar to the ones derived from model (1) in Table 2 .

Practical implications

The modelling framework proposed in this study provides marketing managers with two important insights: (i) estimation of the sales–distribution relationship for their brands and (ii) correct identification of the marketing drivers that can increase brand performance over and above the levels predicted by the sales–distribution relationship. In practical terms, these insights improve managerial understanding of “what to expect” if a distribution expansion is planned but also indicate which marketing tools are suitable for improving the performance of specific brands.

These are key insights in the brand management process that can improve the effective allocation of marketing resources. For example, the distribution levels of brand 2 can be increased further since the sales–distribution relationship is mostly linear without any strong indications of decreasing returns. A distribution expansion can also be combined with “feature and display” and “special pack” promotions, which provided the highest returns according to the model’s results. Furthermore, due to the brand’s high price sensitivity, any significant price per unit increases should be avoided.

For brand 3 distribution expansions should be planned carefully, with due diligence in the store selection process since there are already indications of decreasing returns in its velocity curve. The same is true for brand 1. New store introductions should preferably be combined with in-store support programs that can include “special promo packs” and “displays” in the case of brand 3 and “features and displays” and “special promo packs” in the case of brand 1. Another possible course of action for the marketing managers of brands 1 and 3 would be to consider increasing demand with marketing activities first, before focusing on costly distribution expansions, and replace those SKUs that are not providing the expected distribution returns.

Our analysis is also useful for retailers who are considering methods for expanding the range of their assortments, through the allocation of shelf space to new brands. In addition to the insights mentioned above, retailers can work closely with their suppliers in order to choose the right promotional support programs for their brands and carefully adjust their prices when this is needed. For example, for the three brands examined in this study price decreases tend to increase sales when the prices (per unit) are already in the “medium-to-high” range. In contrast, due to saturation effects large price reductions in the “very low-to-low” price per unit range will not tend to be equally effective. Furthermore, the brand specific nature of our proposed method enables comparisons between brands, which entails useful category management insights for retailers.

Finally, for marketing managers considering the delisting of a product from a subset of its existing handling universe, the proposed model can provide indications of the likely impact on sales from the resulting distribution reduction. Consequently, our proposed modelling framework is also suitable for scenario analysis, by generating predictions regarding the possible market outcomes from changes in distribution, as well as, the price and promotional support activities of the brand portfolios.

Conclusions

In this study, a semiparametric version of the SCAN*PRO model that can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of a brand’s retail distribution network was proposed. The model is calibrated on panel data, where the cross-sectional units consist of all the SKUs included in a brand portfolio and the time period is weekly observations. By incorporating all the SKUs of a brand portfolio in a common panel dataset, sufficient variation is achieved that enables a nonparametric estimation of the sales–distribution relationship. Estimation is performed using the backfitting algorithm and commonly available scanning data, which produces least squares coefficient estimates for the price and promotional drivers and two-dimensional plots of the nonmonotonic relationship between the retail distribution coverage and sales. These plots demonstrate the nonlinearities that frequently characterize the sales–distribution relationship and facilitate visual inspection.

Marketing managers can use the modelling framework proposed in this study to evaluate the distribution network of their brands and perform market response predictions for given levels of distribution. This framework also enables the identification of gaps in the distribution coverage while at the same time controlling for the effect of other marketing activities on sales. It can also be used for the joint evaluation of all the main marketing drivers that can increase performance over and above the levels predicted by the sales–distribution relationship and facilitates “what-if” scenario analyses, which are important for planning the efficient allocation of marketing resources. The two-dimensional plots of the sales–distribution relationship should be updated frequently for the main brands in a product category. This is because changes in the number and characteristics of SKUs in a brand portfolio and changes in the population and the locations of stores in a market can change the partial regression functions.

The proposed model can also be estimated for specific market segments (e.g., channels or geographical areas) and can be used to compare the distribution expansion of brands produced by the same manufacturer. In evaluating the results, it is also useful to calculate the distribution gaps of all SKUs relative to their brand totals (brand weighted distribution–SKU weighted distribution) and the SKU sales per point of distribution (SKU sales volume/weighted distribution). This analysis enables the identification of the SKUs with high sales per point of distribution whose distribution network can therefore be expanded.

It is also worth mentioning that an updated and thoroughly informed retail census database can provide valuable inputs in the distribution evaluation process. Apart from basic business demographics, this database must contain a sufficient number of variables that can be used as indicators of the size and importance of each retail store. Lehmann and Winer ( 2001 , p. 179) provide some useful guidelines in this direction. A retail census database can also be combined with geographical information systems and econometric models to predict store performance. Retail distribution networks should be designed carefully with the proper identification of the important stores in a market prior to distribution expansion, and the impact of distribution changes on sales should be evaluated on a continuous basis. Further research should examine the application of our proposed semiparametric SCAN*PRO model in emerging markets where data are usually available with lower frequency (e.g. monthly or bi-monthly) and the structure of the retail trade is different (e.g. higher share of full-service stores).

Abe, M. 1995. A nonparametric density estimation method for brand choice using scanner data. Marketing Science 14 (3): 300–325.

Article Google Scholar

Albers, S. 2012. Optimizable and implementable aggregate response modelling for marketing decision support. International Journal of Research in Marketing 29: 111–122.

Allison, P.D. 2009. Fixed effects regression models . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Andrews, R.L., I.S. Currim, P.S.H. Leeflang, and J. Lim. 2008. Estimating the SCAN*PRO model of store sales: HB, FM or just OLS? Intern. Journal of Research in Marketing 25 (1): 22–33.

Arnold, D. (2000). Seven rules of international distribution. Harvard Business Review (November–December): 131–137.

Brissimis, S.N., and K.E. Kioulafas. 1987. An analysis of advertising and distribution effectiveness. European Journal of Operational Research 28: 175–179.

Bronnenberg, B.J., V. Mahajan, and W.R. Vanhonacker. 2000. The emergence of market structure in new repeat-purchase categories: The interplay of market share and distribution. Journal of Marketing Research 37 (February): 16–31.

Bucklin, R.E., S. Siddarth, and J.M. Silva-Risso. 2008. Distribution intensity and new car choice. Journal of Marketing Research 45 (August): 473–486.

Erjavec, J., and A. Manfreda. 2022. Online shopping adoption during COVID-19 and social isolation: Extending the UTAUT model with herd behaviour. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 65: 102867.

Farris, P., J. Olver, and C. de Kluyver. 1989. The relationship between distribution and market share. Marketing Science 8 (2): 107–128.

Foekens, E.W., P.S.H. Leeftang, and D.R. Wittink. 1994. A comparison and an exploration of the forecasting accuracy of a loglinear model at different levels of aggregation. International Journal of Forecasting 10 (2): 245–261.

Fox, J. 2000. Multiple and generalized nonparamatric regression . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Fox, J. 2008. Applied regression analysis and generalized linear models . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Google Scholar

Frazier, L.G., and W.M. Lassar. 1996. Determinants of distribution intensity. Journal of Marketing 60 (October): 39–51.

Friberg, R., and M. Sancturary. 2017. The effects of retail distribution on sales of alcoholic beverages. Marketing Science 36 (4): 626–641.

Guhl, D., B. Baumgartner, T. Kneib, and W. Steiner. 2018. Estimating time-varying parameters in brand choice models: A semiparametric approach. International Journal of Research in Marketing 35: 394–414.

Guissoni, L.A., J.M. Rodrigues, F. Zambaldi, and M.F. Navas. 2021. Distribution effectiveness through full- and self-service channels under economic fluctuations in an emerging market. Journal of Retailing . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2021.05.002 .

Hanssens, D.M., L.J. Parsons, and R.L. Schultz. 2001. Market response models: Econometric and time series analysis . Cambridge: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Hastie, T.J., and R.J. Tibshirani. 1990. Generalized additive models . London: Chapman & Hall.

Hirche, M., P.W. Farris, L. Greenacre, Y. Quan, and S. Wei. 2021a. Predicting Under- and overperforming SKUs within the distribution–market share relationship. Journal of Retailing . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2021.04.002 .

Hirche, M., L. Greenacre, M. Nenycz-Thiel, S. Loose, and L. Lockshin. 2021b. SKU performance and distribution: A large-scale analysis of the role of product characteristics with store scanner data. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 61: 102533.

Hruschkla, H. 2002. Market share analysis using semi-parametric attraction models. European Journal of Operational Research 138 (1): 212–225.

Jones, J.M., and C.J. Ritz. 1991. Incorporating distribution into new product diffusion models. International Journal of Research in Marketing 8: 91–112.

Kalyanam, K., and T.S. Shively. 1998. Estimating irregular price effects: A stochastic spline regression approach. Journal of Marketing Research 35 (1): 16–29.

Kopalle, R.K., C.F. Mela, and L. Marsch. 1999. The Dynamic effect of discounting on sales: Empirical analysis and normative pricing implications. Marketing Science 18 (3): 317–332.

Krider, R.E., L. Tieshan, L. Yong, Y. Liu, and C.B. Weinberg. 2008. Demand and distribution relationships in the ready-to-drink iced tea market: A graphical approach. Marketing Letters 19 (1): 1–12.

Krider, R.E., L. Tieshan, L. Yong, and C.B. Weinberg. 2005. The lead-lag puzzle of demand and distribution: A graphical method applied to movies. Marketing Science 24 (4): 635–645.

Leeflang, P.S.H., D.R. Wittink, M. Wedel, and P.A. Naert. 2000. Building Models for Marketing Decisions . Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Lehmann, D.R., and R.S. Winer. 2001. Analysis for marketing planning , 5th ed. Boston: McGraw Hill.

Lilien, G.L., P. Kotler, and K.S. Moorthy. 1992. Marketing models . Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Martínez-Ruiz, M.P., A. Mollá-Descals, M.A. Gómez-Borja, and J.L. Rojo-Álvarez. 2006. Using daily store-level data to understand price promotion effects in a semiparametric regression model. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 13: 193–204.

Michis, A.A. 2009. Regression analysis of marketing time series: A wavelet approach with some frequency domain insights. Review of Marketing Science 7 (1): 2.

Michis, A.A. 2015. A wavelet smoothing method to improve conditional sales forecasting. Journal of the Operational Research Society 66: 832–844.

Nishida, M. 2017. First-mover advantage through distribution: A decomposition approach. Marketing Science 36: 590–609.

Pantano, E., G. Pizzi, D. Scarpi, and C. Dennis. 2020. Competing during a pandemic? Retailers’ ups and downs during the COVID-19 outbreak. Journal of Business Research 116: 209–213.

Park, I., J. Lee, D. Lee, C. Lee, and W.Y. Chung. 2022. Changes in consumption patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic: Analyzing the revenge spending motivations of different emotional groups. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 65: 102874.

Reibstein, D.J., and P.W. Farris. 1995. Market share and distribution: A generalization, a speculation and some implications. Marketing Science 14 (3): 190–202.

Rust, R.T. 1988. Flexible regression. Journal of Marketing Research 25 (1): 10–24.

Sharma, A., V. Kumar, and K. Cosguner. 2019. Modeling emerging-market firms’ competitive retail distribution strategies. Journal of Marketing Research 56: 439–458.

Sloot, L.M., D. Fok, and P.C. Verhoef. 2006. The short and long-term impact of an assortment reduction on category sales. Journal of Marketing Research 43: 536–548.

Steiner, W.J., A. Brezger, and C. Belitz. 2007. Flexible estimation of price response function using retail scanner data. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 14 (6): 383–393.

Tenn, S., and J.M. Yun. 2008. Biases in demand analysis due to variation in retail distribution. Intern. Journal of Industrial Organization 26 (4): 984–997.

Van Heerde, H.J. 2000. Non- and semiparametric regression model. In Building models for marketing decisions , ed. P.S.H. Leeflang, D.R. Wittink, M. Wedel, and P.A. Naert, 555–579. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Van Heerde, H.J. 2017. Non- and semiparametric regression models. In Advanced methods for modeling markets , ed. P.S.H. Leeflang, J.E. Wieringa, T.H.A. Bijmolt, and K.H. Pauwels, 396–408. Cham: Springer.

Van Heerde, H., P.S.H. Leeflang, and D.R. Wittink. 2001. Semi-parametric analysis to estimate the deal effect curve. Journal of Marketing Research 38 (2): 197–215.

Van Heerde, H.J., P.S.H. Leeflang, and D.R. Wittink. 2002. How promotions work: SCAN*PRO-based evolutionary model building. Schmalenbach Business Review 54: 198–220.

Varkatsas, D. 2008. The effects of advertising, prices and distribution on market share volatility. European Journal of Operational Research 187 (1): 283–293.

Wilbur, K.C., and P.W. Farris. 2014. Distribution and market share. Journal of Retailing 90 (2): 154–167.

Wittink, D.R., M.J. Addona, W.J. Hawkes, and J.C. Porter. 2011. SCAN*PRO: The estimation, validation, and use of promotional effects based on scanner data. In Liber Amicorum in honor of Peter S.H. Leeflang, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen , ed. J.E. Wieringa, P.C. Verhoef, and J.C. Hoekstra, 135–162. Groningen: Faculteit Economie en Bedrijfskunde.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Barbara Van De Kerke for invaluable help in understanding the data used in this study and three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and suggestions.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Central Bank of Cyprus, 80 Kennedy Avenue, 1076, Nicosia, Cyprus

Antonis A. Michis

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Antonis A. Michis .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

There is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Michis, A.A. Retail distribution evaluation in brand-level sales response models. J Market Anal 11 , 366–378 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41270-022-00165-8

Download citation

Revised : 22 September 2021

Accepted : 09 March 2022

Published : 25 March 2022

Issue Date : September 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41270-022-00165-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Retail distribution

- Sales response model

- Price effects

- Semiparametric estimation

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, evaluating the effectiveness of sales and distribution systems: a study of marketing innovation.

International Journal of Physical Distribution

ISSN : 0020-7527

Article publication date: 1 February 1974

In the last decade increasing attention has been focussed upon the newer and creative areas of marketing such as consumer behaviour, new product development and the communications interchanges between producers and consumers. More recently, the subject of distribution has been receiving a wider conceptual treatment as “marketing logistics” than had been afforded to it earlier by operational researchers searching for optimum rather than acceptable solutions. Managers have come to realise that, not only can substantial cost savings be achieved in the physical distribution area but that the distribution function complements the selling activity at the interface between the company and its customers. In the case of consumer goods these customers are the channel intermediaries such as wholesalers, cash and carry operators, independent and multiple retailers as well as the voluntary chains.

Cunningham, M.T. and Hardy, S.M.R. (1974), "Evaluating the Effectiveness of Sales and Distribution Systems: A Study of Marketing Innovation", International Journal of Physical Distribution , Vol. 4 No. 3, pp. 133-148. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb014309

Copyright © 1974, MCB UP Limited

Related articles

All feedback is valuable.

Please share your general feedback

Report an issue or find answers to frequently asked questions

Contact Customer Support

International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management

- Submit your paper

- Author guidelines

- Editorial team

- Indexing & metrics

- Calls for papers & news

Before you start

For queries relating to the status of your paper pre decision, please contact the Editor or Journal Editorial Office. For queries post acceptance, please contact the Supplier Project Manager. These details can be found in the Editorial Team section.

Author responsibilities

Our goal is to provide you with a professional and courteous experience at each stage of the review and publication process. There are also some responsibilities that sit with you as the author. Our expectation is that you will:

- Respond swiftly to any queries during the publication process.

- Be accountable for all aspects of your work. This includes investigating and resolving any questions about accuracy or research integrity .

- Treat communications between you and the journal editor as confidential until an editorial decision has been made.

- Include anyone who has made a substantial and meaningful contribution to the submission (anyone else involved in the paper should be listed in the acknowledgements).

- Exclude anyone who hasn’t contributed to the paper, or who has chosen not to be associated with the research.

- In accordance with COPE’s position statement on AI tools , Large Language Models cannot be credited with authorship as they are incapable of conceptualising a research design without human direction and cannot be accountable for the integrity, originality, and validity of the published work. The author(s) must describe the content created or modified as well as appropriately cite the name and version of the AI tool used; any additional works drawn on by the AI tool should also be appropriately cited and referenced. Standard tools that are used to improve spelling and grammar are not included within the parameters of this guidance. The Editor and Publisher reserve the right to determine whether the use of an AI tool is permissible.

- If your article involves human participants, you must ensure you have considered whether or not you require ethical approval for your research, and include this information as part of your submission. Find out more about informed consent .

Generative AI usage key principles

- Copywriting any part of an article using a generative AI tool/LLM would not be permissible, including the generation of the abstract or the literature review, for as per Emerald’s authorship criteria, the author(s) must be responsible for the work and accountable for its accuracy, integrity, and validity.

- The generation or reporting of results using a generative AI tool/LLM is not permissible, for as per Emerald’s authorship criteria, the author(s) must be responsible for the creation and interpretation of their work and accountable for its accuracy, integrity, and validity.

- The in-text reporting of statistics using a generative AI tool/LLM is not permissible due to concerns over the authenticity, integrity, and validity of the data produced, although the use of such a tool to aid in the analysis of the work would be permissible.

- Copy-editing an article using a generative AI tool/LLM in order to improve its language and readability would be permissible as this mirrors standard tools already employed to improve spelling and grammar, and uses existing author-created material, rather than generating wholly new content, while the author(s) remains responsible for the original work.

- The submission and publication of images created by AI tools or large-scale generative models is not permitted.

Research and publishing ethics

Our editors and employees work hard to ensure the content we publish is ethically sound. To help us achieve that goal, we closely follow the advice laid out in the guidelines and flowcharts on the COPE (Committee on Publication Ethics) website .

We have also developed our research and publishing ethics guidelines . If you haven’t already read these, we urge you to do so – they will help you avoid the most common publishing ethics issues.

A few key points:

- Any manuscript you submit to this journal should be original. That means it should not have been published before in its current, or similar, form. Exceptions to this rule are outlined in our pre-print and conference paper policies . If any substantial element of your paper has been previously published, you need to declare this to the journal editor upon submission. Please note, the journal editor may use Crossref Similarity Check to check on the originality of submissions received. This service compares submissions against a database of 49 million works from 800 scholarly publishers.

- Your work should not have been submitted elsewhere and should not be under consideration by any other publication.

- If you have a conflict of interest, you must declare it upon submission; this allows the editor to decide how they would like to proceed. Read about conflict of interest in our research and publishing ethics guidelines .

- By submitting your work to Emerald, you are guaranteeing that the work is not in infringement of any existing copyright.

Third party copyright permissions

Prior to article submission, you need to ensure you’ve applied for, and received, written permission to use any material in your manuscript that has been created by a third party. Please note, we are unable to publish any article that still has permissions pending. The rights we require are:

- Non-exclusive rights to reproduce the material in the article or book chapter.

- Print and electronic rights.

- Worldwide English-language rights.

- To use the material for the life of the work. That means there should be no time restrictions on its re-use e.g. a one-year licence.

We are a member of the International Association of Scientific, Technical, and Medical Publishers (STM) and participate in the STM permissions guidelines , a reciprocal free exchange of material with other STM publishers. In some cases, this may mean that you don’t need permission to re-use content. If so, please highlight this at the submission stage.

Please take a few moments to read our guide to publishing permissions to ensure you have met all the requirements, so that we can process your submission without delay.

Open access submissions and information

All our journals currently offer two open access (OA) publishing paths; gold open access and green open access.

If you would like to, or are required to, make the branded publisher PDF (also known as the version of record) freely available immediately upon publication, you can select the gold open access route once your paper is accepted.

If you’ve chosen to publish gold open access, this is the point you will be asked to pay the APC (article processing charge) . This varies per journal and can be found on our APC price list or on the editorial system at the point of submission. Your article will be published with a Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 user licence , which outlines how readers can reuse your work.

Alternatively, if you would like to, or are required to, publish open access but your funding doesn’t cover the cost of the APC, you can choose the green open access, or self-archiving, route. As soon as your article is published, you can make the author accepted manuscript (the version accepted for publication) openly available, free from payment and embargo periods.

You can find out more about our open access routes, our APCs and waivers and read our FAQs on our open research page.

Find out about open

Transparency and Openness Promotion (TOP) Guidelines

We are a signatory of the Transparency and Openness Promotion (TOP) Guidelines , a framework that supports the reproducibility of research through the adoption of transparent research practices. That means we encourage you to:

- Cite and fully reference all data, program code, and other methods in your article.

- Include persistent identifiers, such as a Digital Object Identifier (DOI), in references for datasets and program codes. Persistent identifiers ensure future access to unique published digital objects, such as a piece of text or datasets. Persistent identifiers are assigned to datasets by digital archives, such as institutional repositories and partners in the Data Preservation Alliance for the Social Sciences (Data-PASS).

- Follow appropriate international and national procedures with respect to data protection, rights to privacy and other ethical considerations, whenever you cite data. For further guidance please refer to our research and publishing ethics guidelines . For an example on how to cite datasets, please refer to the references section below.

Prepare your submission

Manuscript support services.

We are pleased to partner with Editage, a platform that connects you with relevant experts in language support, translation, editing, visuals, consulting, and more. After you’ve agreed a fee, they will work with you to enhance your manuscript and get it submission-ready.

This is an optional service for authors who feel they need a little extra support. It does not guarantee your work will be accepted for review or publication.

Visit Editage

Manuscript requirements

Before you submit your manuscript, it’s important you read and follow the guidelines below. You will also find some useful tips in our structure your journal submission how-to guide.

|

| Article files should be provided in Microsoft Word format. While you are welcome to submit a PDF of the document alongside the Word file, PDFs alone are not acceptable. LaTeX files can also be used but only if an accompanying PDF document is provided. Acceptable figure file types are listed further below. |

|

| Articles should be between 6000 and 8000 words in length. This includes all text, for example, the structured abstract, references, all text in tables, and figures and appendices. There is a standard fixed allowance of 280 words for each Table, Figure, or Image as they occupy this equivalent words of space. |

|

| A concisely worded title should be provided. |

|

| The names of all contributing authors should be added to the ScholarOne submission; please list them in the order in which you’d like them to be published. Each contributing author will need their own ScholarOne author account, from which we will extract the following details: (institutional preferred). . We will reproduce it exactly, so any middle names and/or initials they want featured must be included. . This should be where they were based when the research for the paper was conducted.In multi-authored papers, it’s important that ALL authors that have made a significant contribution to the paper are listed. Those who have provided support but have not contributed to the research should be featured in an acknowledgements section. You should never include people who have not contributed to the paper or who don’t want to be associated with the research. Read about our for authorship. |

|

| If you want to include these items, save them in a separate Microsoft Word document and upload the file with your submission. Where they are included, a brief professional biography of not more than 100 words should be supplied for each named author. |

|

| Your article must reference all sources of external research funding in the acknowledgements section. You should describe the role of the funder or financial sponsor in the entire research process, from study design to submission. |

|

| All submissions must include a structured abstract, following the format outlined below. These four sub-headings and their accompanying explanations must always be included: The following three sub-headings are optional and can be included, if applicable:

The maximum length of your abstract should be 250 words in total, including keywords and article classification (see the sections below). |

|

| Your submission should include up to 12 appropriate and short keywords that capture the principal topics of the paper. Our how to guide contains some practical guidance on choosing search-engine friendly keywords. Please note, while we will always try to use the keywords you’ve suggested, the in-house editorial team may replace some of them with matching terms to ensure consistency across publications and improve your article’s visibility. |

|

| During the submission process, you will be asked to select a type for your paper; the options are listed below. If you don’t see an exact match, please choose the best fit:

You will also be asked to select a category for your paper. The options for this are listed below. If you don’t see an exact match, please choose the best fit: Reports on any type of research undertaken by the author(s), including: Covers any paper where content is dependent on the author's opinion and interpretation. This includes journalistic and magazine-style pieces. Describes and evaluates technical products, processes or services. Focuses on developing hypotheses and is usually discursive. Covers philosophical discussions and comparative studies of other authors’ work and thinking. Describes actual interventions or experiences within organizations. It can be subjective and doesn’t generally report on research. Also covers a description of a legal case or a hypothetical case study used as a teaching exercise. This category should only be used if the main purpose of the paper is to annotate and/or critique the literature in a particular field. It could be a selective bibliography providing advice on information sources, or the paper may aim to cover the main contributors to the development of a topic and explore their different views. Provides an overview or historical examination of some concept, technique or phenomenon. Papers are likely to be more descriptive or instructional (‘how to’ papers) than discursive. |

|

| Headings must be concise, with a clear indication of the required hierarchy. |

|

| Notes or endnotes should only be used if absolutely necessary. They should be identified in the text by consecutive numbers enclosed in square brackets. These numbers should then be listed, and explained, at the end of the article. |

|

| All figures (charts, diagrams, line drawings, webpages/screenshots, and photographic images) should be submitted electronically. Both colour and black and white files are accepted. |

|

| Tables should be typed and submitted in a separate file to the main body of the article. The position of each table should be clearly labelled in the main body of the article with corresponding labels clearly shown in the table file. Tables should be numbered consecutively in Roman numerals (e.g. I, II, etc.). Give each table a brief title. Ensure that any superscripts or asterisks are shown next to the relevant items and have explanations displayed as footnotes to the table, figure or plate. |

|

| Where tables, figures, appendices, and other additional content are supplementary to the article but not critical to the reader’s understanding of it, you can choose to host these supplementary files alongside your article on Insight, Emerald’s content hosting platform, or on an institutional or personal repository. All supplementary material must be submitted prior to acceptance. , you must submit these as separate files alongside your article. Files should be clearly labelled in such a way that makes it clear they are supplementary; Emerald recommends that the file name is descriptive and that it follows the format ‘Supplementary_material_appendix_1’ or ‘Supplementary tables’. . A link to the supplementary material will be added to the article during production, and the material will be made available alongside the main text of the article at the point of EarlyCite publication. Please note that Emerald will not make any changes to the material; it will not be copyedited, typeset, and authors will not receive proofs. Emerald therefore strongly recommends that you style all supplementary material ahead of acceptance of the article. Emerald Insight can host the following file types and extensions: , you should ensure that the supplementary material is hosted on the repository ahead of submission, and then include a link only to the repository within the article. It is the responsibility of the submitting author to ensure that the material is free to access and that it remains permanently available. Please note that extensive supplementary material may be subject to peer review; this is at the discretion of the journal Editor and dependent on the content of the material (for example, whether including it would support the reviewer making a decision on the article during the peer review process). |

|

| All references in your manuscript must be formatted using one of the recognised Harvard styles. You are welcome to use the Harvard style Emerald has adopted – we’ve provided a detailed guide below. Want to use a different Harvard style? That’s fine, our typesetters will make any necessary changes to your manuscript if it is accepted. Please ensure you check all your citations for completeness, accuracy and consistency.