Q&A: Here’s when boycotts have worked — and when they haven’t

- Copy Link URL Copied!

Actress Alyssa Milano was one of thousands who called for a one-day boycott on Thursday of FedEx, Apple TV and Amazon for not severing their ties with the National Rifle Assn. In a tweet, she included a photo of herself in front of the White House, with the words “Never Again” written on her hands in red ink.

The call for action came after Delta and United airlines, parent companies for Avis and Budget, Enterprise, National and Alamo car rentals, financial institutions and more have dropped deals with the gun rights lobbying organization since the Feb. 14 mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., where 17 people were killed.

In an effort to undermine the NRA’s clout and to pressure lawmakers to pass gun control legislation, organizations and individuals have been calling for a variety of boycotts. Among them is David Hogg, a 17-year-old senior at the school, who in a Feb. 24 tweet said that people should boycott Florida for spring break until gun reform happens. If lawmakers won’t listen to students, Hogg wrote, “maybe [they’ll] listen to the billion dollar tourism industry in FL.”

Boycotts are nothing new. Here’s a quick look at how they’ve played out in the U.S. and abroad.

Are boycotts successful?

The answer depends partly in how you define success.

“Very few boycotts have led to changes,” said Maurice Schweitzer, a professor of operations and information management at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. “Most boycotts lack a sustained effort” and people lose interest or stop paying attention, he said.

“In practice, most boycotts achieve the more modest goal of attracting media attention,” Schweitzer wrote in an email. “There are, however, hundreds of calls for boycotts each year, and most accomplish very little.”

Some targets of boycotts in recent years include BP for its role in the 2010 Gulf of Mexico oil spill, and Chick-fil-A, after Chief Operating Officer Dan T. Cathy’s comments against same-sex marriage in 2012.

Is it possible to measure a boycott’s impact?

No, not always, simply because multiple factors can influence events. Consider the case of former San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick, who took a knee during the national anthem to protest racism and police brutality, launching similar protests across the National Football League. In the aftermath of his protest, Kaepernick was not signed by any team.

Kaepernick supporters urged fans to stop watching NFL games, and a Change.org petition calling for a boycott gained more than 200,000 supporters.

“Knowing that NFL owners only respond to ratings, which in turn brings money from advertisers and network partners, I felt the only way to get the owners' attention was to create a petition asking for a full boycott until Colin Kaepernick got signed,” Vic Oyedeji, founder of Unstripped Voice, a platform that promotes racial, social and economic equity, wrote in an email.

The boycott will end if Kaepernick is signed by an NFL team, Oyedeji wrote.

Viewership for the NFL’s 2017 season dropped by 9.7% compared to the previous season, according to Sports Illustrated. However, the NFL’s ratings had also dropped by 8% for the 2016 season — a year before the NFL boycott started. There is no conclusive evidence that the boycott contributed to the ratings decline when other factors — a plunge in the quality of games, growing concern of the game’s violence — are at play.

“Boycotts are rarely the precipitating factor for change. Rather, they bring attention to an issue and signal the magnitude and intensity with which a group feels a particular way,” Schweitzer said. “In most cases, a small minority of people call for a boycott that the wider community fails to support by taking substantive action.”

Have boycotts helped change public opinion?

Yes, and perhaps one of the best examples comes from the civil rights era, when a boycott rose out of tensions over public buses in Montgomery, Ala.

One day in 1955, 15-year-old Claudette Colvin was dragged off a bus by police officers for sitting in the whites-only section. Nine months later, Rosa Parks refused to leave her seat on a Montgomery bus.

Blacks began boycotting the public buses, and soon the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., the Rev. Ralph Abernathy and other civil rights leaders joined their cause. Despite King and Abernathy’s houses being firebombed, they did not stop. “My intimidations are a small price to pay if victory can be won," King said .

A federal court eventually ruled that bus segregation was unconstitutional and violated the equal protection provisions of the 14th Amendment. The boycott, along with Parks’ arrest, cast a harsh spotlight on the inequities African Americans suffered in the Jim Crow South.

Are there other examples of boycotts influencing public opinion?

In 1965, Cesar Chavez and the National Farm Workers Assn. urged the public to boycott grapes to compel growers to provide better pay and working conditions. The boycott targeted nonunion grape businesses.

The National Farm Workers Assn. joined the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee to form United Farm Workers and increase attention on their boycott. Millions showed solidarity by not purchasing grapes until the UFW signed its first union contracts.

Another major boycott, which won support from across the globe as well as the U.S., targeted South Africa and its system of racial segregation known as apartheid. Individuals as well as companies and governments boycotted the country. Tourists refused to travel there, companies would not do business there, artists would not perform there. South Africa was excluded from the Olympics for decades.

In 1986, Congress voted to override a veto by President Reagan to enact the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act. The act banned South African imports, airlines and foreign aid from the U.S. International companies began leaving South Africa in droves, causing significant losses in revenue and jobs there.

Leader P.W. Botha resigned in 1989, and his successor, F.W. de Klerk, lifted a ban on the African National Congress and freed Nelson Mandela and all political prisoners in 1990.

In 1993, the U.S. sanctions against South Africa were lifted after De Klerk announced a completely representative democratic process for their presidential election. The following year, Mandela was elected as South Africa’s first black leader and apartheid was dismantled.

The Montgomery bus and South Africa boycotts “are the exceptions, rather than the rule, of boycotts that ended with the desired policy change,” Schweitzer said.

Do boycotts inflict economic harm?

Sometimes, yes. The liberal polling firm Center for American Progress wrote a 2010 report called "Stop the Conference" that estimated that Arizona lost $45 million in convention business because of a boycott called after passage of SB 1070, a tough law targeting illegal immigration.

Most recently, boycotts targeted North Carolina after the passage of the Public Facilities Privacy & Security Act, commonly known as House Bill 2, which blocked localities from passing protections for the LGBTQ community and instructed transgender people to use the bathroom of the sex they were assigned at birth.

In response to the passage of HB2, several organizations and agencies boycotted North Carolina. The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors wrote a letter to then-North Carolina Gov. Pat McCrory to say county employees were barred from visiting the state for county business.

“We echo the overwhelming criticism expressed by local governments in your state and throughout the nation that have passed resolutions calling for the repeal of HB2,” the letter read. The board joined 28 other counties, seven states and the District of Columbia, and 29 cities in barring employees from traveling to North Carolina.

Professional and collegiate sports leagues like the National Collegiate Athletic Assn., Atlantic Coast Conference and the Central Intercollegiate Athletic Assn. all pulled significant events from the state. The NBA announced on July 21, 2016, that the league would move its 2017 All-Star Weekend from Charlotte to New Orleans. The loss of revenue to North Carolina was estimated at $100 million.

Entertainment company Lionsgate canceled filming of its Hulu series “Crushed” in Charlotte. 21st Century Fox, A&E Networks and Turner Broadcasting said they would not consider North Carolina for future production if HB2 were not repealed.

In all, the state lost more than $3.76 billion, according to an Associated Press analysis.

Once HB2 was repealed and replaced, those corporations and organizations agreed to do business with North Carolina again.

Twitter: @mikelive06

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Michael Livingston was a Metpro trainee from 2017-18 at the Los Angeles Times. He previously worked as a crime reporter at the Herald in Rock Hill, S.C. and the Danville Register & Bee in Virginia. While at the Register & Bee, he won multiple Virginia Press Assn. awards for crime and breaking news reporting. He graduated from Virginia Union University in Richmond.

More From the Los Angeles Times

Column: Trump talks tough on Russia now, but as president he bowed to Putin

Science & Medicine

Are tiny black holes zipping through our solar system? Scientists hope to find out.

Opinion: Authoritarianism and hatred are no match for a politics of love

California enacts law reviving a Jewish family’s claim to Nazi-looted art, bucking 9th Circuit

Sept. 16, 2024

Most Read in World & Nation

World & Nation

How a memorial to WWII sex slaves ignited a battle in Berlin

Sex tourism in Indonesia sells itself as Islamic temporary marriage

Sept. 11, 2024

How 3 Americans ended up in the middle of a coup attempt in Congo and face the death penalty

Sept. 15, 2024

A secretive group recruited far-right candidates in key U.S. House races. It could help Democrats

- TeachableMoment

The Boycott, Then and Now

Two student readings (with discussion questions) examine the historical development of the boycott as a tactic used by both progressives and conservatives, and recent boycotts targeting Glenn Beck and Florida's Stand Your Ground law.

by Mark Engler

To The Teacher:

The boycott is one of the most powerful, time-tested tactics that social movements have at their disposal. History offers many examples of people joining together to exercise their power as consumers in support of movements for social justice, civil rights, and workers' rights. By calling for people to not spend their money on a target good or service, boycotts can aid these movements by drawing on a wider base of supporters who would otherwise be unable to participate.

This lesson examines the historical development of the boycott as a tactic - with examples of its use by both progressives and conservatives - and looks at some recent boycotts that are related to hot-button political issues.

The first student reading considers the history of the boycott in the United States, reviewing some famous examples of how it has been used. The second reading examines some recent boycotts, with focus on the online advocacy group ColorOfChange.org. This group launched a campaign pressuring advertisers that supported controversial right-wing commentator Glenn Beck. They also launched a boycott targeting a group that championed Florida's "Stand Your Ground" gun law, which drew attention in the wake of the Trayvon Martin shooting. The reading explores how these campaigns developed and considers responses from conservative critics - including calls for a counter-boycott.

Questions for student discussion follow each reading.

Student Reading 1:

The boycott: an american tradition.

The boycott is one of the most powerful, time-tested tactics that activists have at their disposal. History offers many examples of people joining together to exercise their power as consumers in support of movements for social justice, civil rights, and workers' rights. By calling for people to not spend their money on a target good or service, boycotts can compel a targeted company to change its behavior so it can win back customers and ward off economic damage.

Two of the most famous American boycotts are the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the United Farm Workers' (UFW) grape boycott. Both of these successful boycotts emerged in the context of the social and political upheavals of the 1950s and 60s.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott is the first boycott most Americans learn about in school. The boycott is considered one of the most important episodes in the southern struggle for civil rights, and is best remembered for some of its central participants: Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr., and Ralph Abernathy.

Like many Southern cities, Montgomery, Alabama, rigidly enforced "Jim Crow" laws for racial segregation. On buses, this meant that black riders were required to sit in the back while white riders got seats in the front. Black riders were expected to surrender their seats to white riders when a bus was full.

The boycott began on December 1, 1955 when Rosa Parks, a trained activist, refused to surrender her seat to a white rider and was arrested. For more than a year, the black community of Montgomery overwhelmingly avoided using the city's buses, organizing carpools or walking long distances instead. Protesters faced a harsh, often violent backlash. Nevertheless, their persistence started paying off in June 1956, when a federal district court ruled that Alabama's segregation of buses was unconstitutional. In November, the United States Supreme Court upheld the district court's ruling and a Montgomery ordinance finally desegregated buses in the city.

Not only was the Montgomery Bus Boycott successful in ending segregation on a local level, news images of the action galvanized public support for the civil rights cause nationally. As The Nation magazine explains:

For 381 days, despite brutal harassment, and no protection from the state or federal government, the boycott endured. When it finally ended on December 27, 1956, not only was it a complete victory for the black community, but the civil rights movement had a new leader in King and a momentum that over the next ten years would destroy nearly every vestige of Jim Crow that had plagued the South and the nation since the Civil War. ( http://www.thenation.com/learning-pack/montgomery-bus-boycott )

Another important boycott was organized by the United Farm Workers (UFW). Through much of the first half of the 20th century, labor union organizers had attempted unsuccessfully to bring California's farm workers into a union. These workers were largely immigrants from Latin America and Asia who labored under harsh conditions with little pay. Organizers finally began to make headway in the 1950s under the leadership of Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez, who in 1962 co-founded the organization that later became the UFW.

To build support for their on-the-ground organizing efforts, the UFW called on people throughout the country to stop eating grapes. Documentarian Rick Tejada-Flores writes on the PBS website:

By 1967 farmworkers were enlisting consumers in their battle. When the Giumarra Corporation tried to disguise their shipments by using other grape growers' labels, the farmworkers began a national boycott of all table grapes. Striking farmworkers spread out across the country, forging alliances with students, churches, and consumers and other union members to try to stop the sale of grapes... At its height, more than 14 million Americans helped by not buying grapes. The pressure was irresistible, and the [California] growers signed historic contracts with UFWOC in 1969. ( http://www.pbs.org/itvs/fightfields/cesarchavez1.html )

The boycott was effective because it allowed people across the country who were sympathetic to the UFW organizing effort but unable to participate directly to lend meaningful support to the cause.

While boycotts are often associated with politically liberal causes, they are sometimes used for conservative ends. In 1997, the Southern Baptist Convention launched a boycott of the Walt Disney Company in response to the company's decision to extend health care and other benefits to the partners of gay employees. As the Associated Press reported in June 2005, when the boycott officially ended:

Southern Baptists ended an eight-year boycott of the Walt Disney Co. (DIS) for violating "moral righteousness and traditional family values" in a vote on the final day of the faith's annual convention Wednesday... The Disney resolution, passed at the SBC's 1997 convention in Dallas, called for Southern Baptists to refrain from patronizing Disney theme parks and Disney products, mainly because of the entertainment company's decision to give benefits to companions of gay employees. ( http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,160382,00.html )

Unlike the grape boycott and the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the Disney boycott was ultimately unsuccessful in forcing any substantive changes in behavior from the campaign's target.

For Discussion:

1. Do students have any questions about the reading? How might they be answered?

2. What is a boycott? What does it aim to do?

3. What was the goal of the Montgomery Bus Boycott? What impacts did it ultimately have?

4. While the Montgomery Bus Boycott primarily drew on local participation, the UFW grape boycott depended on the participation of people from across the country. How do you think this affected the character of the action?

5. Why do you think the Montgomery Bus Boycott and UFW grape boycott were successful while the SBC's boycott of Disney failed?

Student Reading 2:

Colorofchange.org and the boycott today .

The boycott remains a tactic that is regularly deployed in political life, including in the past year. A progressive online advocacy group called ColorofChange.org has gained notable success with two campaigns: one to encourage sponsors to leave conservative pundit Glenn Beck's television program and another to put pressure on companies supporting a right-wing legislative group called ALEC. Liberals see these two campaigns as effective political interventions. But conservatives say that the campaigns unfairly sought to limit the free expression of ideas.

On July 28, 2009, the controversial conservative commentator and Fox News Channel host Glenn Beck appeared on the daily talk show "Fox and Friends" to discuss recent news. When the conversation turned to President Obama's response to a racially charged incident that was in the headlines, Beck called the president himself a racist, charging that President Obama held "a deep seated hatred for white people or the white culture."

Beck's inflammatory remark provoked an immediate backlash. ColorOfChange.org launched a petition calling on Beck's advertisers to terminate their sponsorship of the program. The petition received nearly 300,000 signatures and advertisers began leaving in droves. In total, nearly 400 advertisers ended their support of Beck's program. To strengthen their case to advertisers, ColorOfChange activists also documented other extreme comments that Beck had made.

Ultimately, Fox News chose not to renew its contract with Beck, whose program on that network ended in June 2011. Fox News executives denied that ColorOfChange had anything to do with their decision not to extend Beck's contract, stating, "The advertisers referenced have all moved their spots from Beck to other day parts on the network, so there has been no revenue lost." But Eric Boehlert of the progressive media watchdog group Media Matters offered a contrary view in an April 7, 2011 article:

The television industry is built around supply and demand. Glenn Beck has supply in the form of roughly 20 minutes of advertising time sold each episode. And it wants to build demand. Usually, healthy ratings drive that demand since advertisers want to reach the masses. But if suddenly hundreds of advertisers raise their hand and announce they'd be happy to spend money with Fox News, but not on Glenn Beck, then the show's demand plummets, but the supply - the 20 minutes of advertising inventory - remains the same. Bottom line? The ad rates go down.... As Brad Adgate, director of research for the ad-buying giant Horizon Media, noted in an email to me yesterday: "Ad rates are predicated on supply and demand, not ratings. If the show has low demand and an oversupply of advertiser inventory, the show will not get premium ad pricing no matter how many viewers." ( http://mediamatters.org/blog/201104070011 )

In a typical boycott, a group of consumers withhold their patronage of a particular good or service until the company heeds its demands. In the case of ColorOfChange.org's campaign against Glenn Beck, it was the implied threat of a consumer boycott that led companies that advertised on Beck's program to withdraw their sponsorship.

A similar dynamic appeared in early 2012 when ColorOfChange.org set its sights on the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), a conservative thinktank known for championing right-wing causes. One such cause is the Florida "Stand Your Ground" gun law, which drew attention in the wake of the Trayvon Martin shooting. ( Under the law, an individual has no "duty to retreat" before resorting to the use of deadly force for self-defense. See our TeachableMoment lesson .)

ColorOfChange.org decided to act on public outrage about ALEC's support of Stand Your Ground and of "voter ID laws," which critics say disproportionately prevent poor people and people of color from voting. ColorOfChange.org decided to focus public pressure on the various companies that pay $25,000-per-year dues to ALEC. ColorOfChange.org launched a petition drive, urging people to write to these organizations expressing their concern. A sample letter written by ColorOfChange.org stated:

I presume your company does not want to support voter suppression, nor have your products or services associated with discrimination and large-scale voter disenfranchisement. I urge you to immediately stop funding ALEC and issue a public statement making it clear that your company does not support discriminatory voter ID laws and voter suppression.

In response to the campaign, a string of companies, including Wendy's, McDonald's, Coke, Pepsi, and Kraft, all announced that they were leaving ALEC. In response, ALEC retreated from some of its most controversial positions, stating that it was "eliminating [its] Public Safety and Elections task force that dealt with non-economic issues" such as Stand Your Ground and Voter ID.

Liberal critics of ALEC regarded the announcement as a victory. However, many conservatives were unhappy that corporations had backed away from their financial commitment to the group's legislative advocacy. In a column for the Concord Monitor entitled, " Why Are Liberals So Scared of ALEC, " State Representative Jordan Ulery argued that the boycott represented an unfair suppression of ideas. "[T]he fringe left is apparently opposed to open thinking and discussion of legislation," he wrote.

Ulery's complaint notwithstanding, others called for conservatives to adopt the boycott tactic for their own purposes: namely, punishing companies that decided to leave ALEC. At National Review Online , commentator Michelle Malkin wrote:

Let's stipulate: Activists on the left are free to exercise their rights of speech and assembly to boycott businesses whose politics they oppose. Conversely, activists on the right are free to exercise the power of their pocketbooks and refrain from supporting businesses that shun their values... It's time for conservatives to stand their ground and stop showing these corporate cowards their money.

1. Do students have any questions about the reading? How might they be answered?

2. Why did ColorOfChange.org choose to target Glenn Beck? Why did it later target the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC)?

3. With its two campaigns, ColorOfChange.org did not actually boycott any specific corporation, it merely created the implied threat of a boycott. How did the group do this?

4. Conservative legislator Jordan Ulery believes that the ColorOfChange.org boycotts represented an unfair suppression of ideas. Do you agree or disagree? Why?

5. In contrast, Michelle Malkin argues that conservatives should launch a boycott of their own. What do you think would be the result of two competing boycotts?

6. ColorOfChange.org used the internet as a primary vehicle for spreading the word about its petitions and getting people to sign on. How do you think the existence of the Internet has affected the boycott tactic? In what ways might the tactic evolve further in the future?

This lesson was written by Mark Engler for TeachableMoment.Org, with research assistance by Eric Augenbraun.

We welcome your comments. Please email them to: [email protected] .

Share this Page

Top of page

Presentation U.S. History Primary Source Timeline

The civil rights movement.

In the middle of the 20th century, a nationwide movement for equal rights for African Americans and for an end to racial segregation and exclusion arose across the United States. This movement took many forms, and its participants used a wide range of means to make their demands felt, including sit-ins, boycotts, protest marches, freedom rides, and lobbying government officials for legislative action. They faced opposition on many fronts and fell victim to bombings and beatings, arrest and assassination. By the end of the 1960s, the civil rights movement had brought about dramatic changes in the law and in public practice, and had secured legal protection of rights and freedoms for African Americans that would shape American life for decades to come.

A few key moments include:

- Brown v. Board of Education The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Legal Defense and Educational Fund, led by Thurgood Marshall, spent decades fighting against racial segregation in education. This long campaign culminated when the U.S. Supreme Court heard Brown v. Board of Education, which gathered together five separate cases related to school segregation with Marshall leading the arguments before the Court. On May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” legally ending racial segregation in public schools and overruling the “separate but equal” principle set forth in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1889.

- Rosa Parks arrested On December 1, 1955, civil rights activist Rosa Parks was arrested when she refused to surrender her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama, bus to a white passenger. The arrest led to the Montgomery Bus Boycott, a pivotal event in the U.S. Civil Rights Movement, and was a defining moment in Parks' long career as an activist. The Montgomery Bus Boycott also saw the rise to prominence of a young Montgomery minister, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

- Little Rock school integration crisis After the Brown v. Board, Supreme Court decision, state and local officials in a number of states resisted school integration. In September of 1957, nine African American students attempted to attend Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. The governor ordered the state’s National Guard to surround the high school, and the Black students were harassed and kept from entering the building. President Dwight Eisenhower nationalized the Arkansas National Guard and sent U.S. troops to protect the students and enforce the desegregation order of the federal courts.

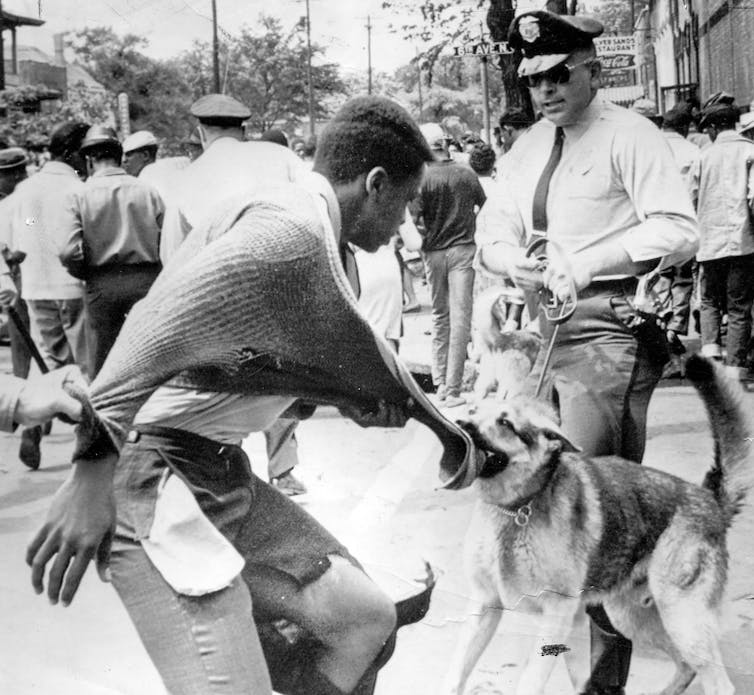

- Birmingham campaign In the spring of 1963, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., launched a large-scale campaign of sit-ins and marches in Birmingham, Alabama, to protest the city’s brutal segregation policies. Many of the protestors and leaders were jailed, and while behind bars, Dr. King wrote a long public letter that explained his philosophy of non-violent protest. This document, which became known as “The Letter from Birmingham Jail,” went on to be widely republished and regarded as a classic defense of the principles of civil disobedience.

- The March on Washington On August 28, 1963, hundreds of thousands of people arrived in Washington, D.C., for the largest non-violent civil rights demonstration that the nation had ever seen: The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The march was organized in a few months, coordinated by veteran strategist Bayard Rustin, and was meant to demonstrate an urgent need for substantive change. The demands in the event program began with “Comprehensive and effective civil rights legislation from the present Congress” and included the end of discrimination in education, housing, employment, and more. Leaders and organizers met with members of Congress and with President John F. Kennedy, while the march ended at the Lincoln Memorial with music and speeches, including Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

- The Selma civil rights marches On March 7, 1965, a civil rights march in Selma, Alabama, led by 25-year-old activist leader John Lewis, was attacked by state troopers and sheriff’s deputies as the marchers attempted to cross the city’s Edmund Pettus Bridge. Coverage of the marchers being beaten, tear-gassed, and trampled by police horses prompted outrage across the nation, and activists, religious leaders, and everyday citizens flooded into Selma to lend their support. On March 9, a second group of marchers, led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., approached the bridge, prayed there, and returned to church. On March 21, thousands of marchers crossed the bridge, this time protected by federalized National Guard troops, and headed to Montgomery.

- The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 The two most significant pieces of civil rights legislation since Reconstruction were passed within two years of each other. Between the two, these Acts outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. They banned discrimination in public accommodations, public education, and employment, and prohibited race-based restrictions on voting. Such sweeping legislation had been a longtime goal of the civil rights movement, and it brought many of the laws and practices of the Jim Crow Era to an end.

- Holding a poster against racial bias in Mississippi are four of the most active leaders in the NAACP movement

- Poster for an appearance by Rosa Parks

- Freeman A. Hrabowski oral history

- Vivian Malone entering Forster Auditorium to register for class at the University of Alabama

- Final plans for the march on Washington for jobs and freedom, August 28, 1963

- The Civil Rights Act of 1964

Breadcrumbs Section. Click here to navigate to respective pages.

Consumer Boycotts

DOI link for Consumer Boycotts

Get Citation

Despite the increasing occurrence of consumer boycotts, little has been written about this form of social and economic protest. This timely volume fills the knowledge gap by examining boycotts both historically and currently. Drawing on both published and unpublished material as well as personal interviews with boycott groups and their targets, Monroe Friedman discusses different types of boycotts-from their historical focus on labor and economic concerns to the more recent inclusion of issues such as minority rights, animal welfare, and environmental protection. He also documents the shift in strategic emphasis from the marketplace (cutting consumer sales) to the media (securing news coverage to air criticism of a targeted firm). In turn, these changes in boycott substance and style offer insights into larger upheavals in the social and economic fabric of 20th century America.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter 1 | 20 pages, consumer boycott basics, chapter 2 | 12 pages, factors affecting boycott success, chapter 3 | 30 pages, labor boycotts, chapter 4 | 26 pages, consumer economic boycotts, chapter 5 | 42 pages, minority group initiatives: african american boycotts, chapter 6 | 28 pages, boycott initiatives of other minority groups, chapter 7 | 22 pages, boycotts by religious groups, chapter 8 | 20 pages, ecological boycotts, chapter 9 | 12 pages, consumer “buycotts”, chapter 10 | 14 pages, boycott issues and tactics in historical perspective.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Taylor & Francis Online

- Taylor & Francis Group

- Students/Researchers

- Librarians/Institutions

Connect with us

Registered in England & Wales No. 3099067 5 Howick Place | London | SW1P 1WG © 2024 Informa UK Limited

Black economic boycotts of the civil rights era still offer lessons on how to achieve a just society

Associate Professor of History, UMass Amherst

Disclosure statement

Kevin A. Young does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

UMass Amherst provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation US.

View all partners

Signed into law 60 years ago, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed discrimination in the U.S. based on “race, color, sex, religion, or national origin.”

Yet, as a historian who studies social movements and political change, I think the law’s most important lesson for today’s movements is not its content but rather how it was achieved.

As firsthand accounts from the era make clear, the movement won because it directly hurt the interests of white business owners. The 1955 Montgomery bus boycott , the 1963 boycott of Birmingham businesses and many lesser-known local boycotts inflicted major costs on local business owners and forced them to support integration.

The conventional narrative

A view common among scholars, activists and the general public holds that the Civil Rights Movement succeeded because violent attacks against peaceful Black protesters mobilized white public opinion in the movement’s favor.

One of the most famous incidents occurred in Birmingham, Alabama, in May 1963, when the city’s public safety commissioner, Eugene “Bull” Connor , turned fire hoses and dogs on Black demonstrators.

The conventional wisdom is that Connor’s actions outraged Northern whites, and in response, the Kennedy administration sent federal troops to Birmingham and a civil rights bill to Congress.

But this view misunderstands the source of the movement’s power.

For one thing, it overstates public sympathy for the Civil Rights Movement. Three months after the attacks against Black protesters in Birmingham, for instance, almost two-thirds of the public opposed the famous March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom of August 1963.

Moreover, the Kennedy administration predicted that civil rights legislation would hurt the Democrats electorally . “The President never had any illusions about the political advantages of equal rights,” wrote Kennedy aide Arthur Schlesinger in his memoir “ A Thousand Days .” “But he saw no alternative” given the movement’s actions.

So what were those actions?

Black organizers aimed to inflict maximal disruption on the white power structure, particularly economic elites. As Martin Luther King Jr. later recounted , “The political power structure listens to the economic power structure.”

By disrupting white businesses, often in a highly organized way, Black activists won social change.

A ‘devastatingly effective’ weapon

Economic boycotts in Southern cities such as Birmingham and Nashville, Tennessee , played crucial roles during the civil rights era.

A 20-month boycott by Black shoppers of downtown businesses in Greenwood, Mississippi , brought legal changes to the city’s hiring practices in 1964.

The most famous boycott occurred in 1955–56 in Montgomery, Alabama, where the nearly 13-month protest against segregated public transportation caused the city’s bus service to lose an estimated US$3,000 a day in fares.

Black people made up about 75% of public transportation riders. Instead of using city buses, they walked, formed car pools and used Black-owned taxi services. The boycott ended on Dec. 20, 1956, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Browder v. Gayle that segregation on buses was unconstitutional.

By 1960, civil rights organizers were widely embracing this “economic weapon to fight segregation,” reported the national magazine Business Week.

Three years later, Time magazine wrote that boycotts had proved “devastatingly effective” in pushing white business owners and government officials to desegregate.

In Birmingham, for example, real estate tycoon Sidney Smyer led the elite push for integration. Smyer was a staunch racist , but he capitulated amid the boycott and related disruption.

“I’m still a segregationist,” he said in May 1963, but “I’m not a damn fool.”

During five weeks of boycotts, sit-ins and marches, Birmingham businesses had lost millions in sales .

Smyer and his fellow executives decided to cut their losses by integrating. They then dragged along the politicians, judges, school administrators and law enforcement officials.

That had been civil rights strategists’ plan from the start.

According to civil rights organizer Abraham Woods , they hoped that business owners hurt by the boycott in Birmingham would “ pressure the city ” to integrate.

Andrew Young, an adviser to King, later said that “Bull Connor made the impact greater, but the dynamics would have taken effect without Bull Connor and the dogs. … When the demonstrations were so massive and the economic withdrawal program was so tight, literally, the town was paralyzed.”

Changing the law after Birmingham

The Birmingham victory inspired other Black people to rise up. Kennedy’s Department of Justice reported another 2,062 Black protests in 40 states by the end of 1963.

It also led Kennedy – 28 months into his presidency – to propose a civil rights bill , in June 1963.

Even as he tried to dissuade Black leaders from marching on Washington, Kennedy admitted that the disruptive boycotts and protests “had made the executive branch act faster and were now forcing Congress to entertain legislation,” as Schlesinger reported in his book “A Thousand Days.”

Kennedy also feared the radicalization of Black consciousness after Birmingham. If the federal government didn’t deliver moderate reform, the “colored masses” might embrace “the mindless radicalism of the Negro militants,” as Schlesinger described the president’s logic.

Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963 meant the civil rights bill fell to his successor, Lyndon Johnson. After a heated battle in Congress, Johnson signed the bill into law on July 2, 1964.

By causing massive and sustained disruption to ruling-class interests, particularly businesses, Black organizers who were formally excluded from political power were able to force legal change.

The lesson is that major legislative reform requires mass disruption outside the electoral and legislative spheres. Without that disruption, it will be very difficult to win any law that negatively affects entrenched power-holders.

- Montgomery bus boycott

- Racial segregation

- Civil Rights Act

- Martin Luther King, Jr. (MLK)

- John F. Kennedy

Professor of Indigenous Cultural and Creative Industries (Identified)

Communications Director

Associate Director, Post-Award, RGCF

University Relations Manager

2024 Vice-Chancellor's Research Fellowships

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

‘Could I really cut it?’

For this ring, I thee sue

Speech is never totally free

In her book, “Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict,” Harvard Professor Erica Chenoweth explains why civil resistance campaigns attract more absolute numbers of people.

Photo by Hossam el-Hamalawy

Nonviolent resistance proves potent weapon

Michelle Nicholasen

Weatherhead Center Communications

Erica Chenoweth discovers it is more successful in effecting change than violent campaigns

Recent research suggests that nonviolent civil resistance is far more successful in creating broad-based change than violent campaigns are, a somewhat surprising finding with a story behind it.

When Erica Chenoweth started her predoctoral fellowship at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs in 2006, she believed in the strategic logic of armed resistance. She had studied terrorism, civil war, and major revolutions — Russian, French, Algerian, and American — and suspected that only violent force had achieved major social and political change. But then a workshop led her to consider proving that violent resistance was more successful than the nonviolent kind. Since the question had never been addressed systematically, she and colleague Maria J. Stephan began a research project.

For the next two years, Chenoweth and Stephan collected data on all violent and nonviolent campaigns from 1900 to 2006 that resulted in the overthrow of a government or in territorial liberation. They created a data set of 323 mass actions. Chenoweth analyzed nearly 160 variables related to success criteria, participant categories, state capacity, and more. The results turned her earlier paradigm on its head — in the aggregate, nonviolent civil resistance was far more effective in producing change.

The Weatherhead Center for International Affairs (WCFIA) sat down with Chenoweth, a new faculty associate who returned to the Harvard Kennedy School this year as professor of public policy, and asked her to explain her findings and share her goals for future research. Chenoweth is also the Susan S. and Kenneth L. Wallach Professor at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study.

Erica Chenoweth

WCFIA: In your co-authored book, “ Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict ,” you explain clearly why civil resistance campaigns attract more absolute numbers of people — in part it’s because there’s a much lower barrier to participation compared with picking up a weapon. Based on the cases you have studied, what are the key elements necessary for a successful nonviolent campaign?

CHENOWETH: I think it really boils down to four different things. The first is a large and diverse participation that’s sustained.

The second thing is that [the movement] needs to elicit loyalty shifts among security forces in particular, but also other elites. Security forces are important because they ultimately are the agents of repression, and their actions largely decide how violent the confrontation with — and reaction to — the nonviolent campaign is going to be in the end. But there are other security elites, economic and business elites, state media. There are lots of different pillars that support the status quo, and if they can be disrupted or coerced into noncooperation, then that’s a decisive factor.

The third thing is that the campaigns need to be able to have more than just protests; there needs to be a lot of variation in the methods they use.

The fourth thing is that when campaigns are repressed — which is basically inevitable for those calling for major changes — they don’t either descend into chaos or opt for using violence themselves. If campaigns allow their repression to throw the movement into total disarray or they use it as a pretext to militarize their campaign, then they’re essentially co-signing what the regime wants — for the resisters to play on its own playing field. And they’re probably going to get totally crushed.

In 2006, Erica Chenoweth believed in the strategic logic of armed resistance. Then she was challenged to prove it.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

WCFIA: Is there any way to resist or protest without making yourself more vulnerable?

CHENOWETH: People have done things like bang pots and pans or go on electricity strikes or something otherwise disruptive that imposes costs on the regime even while people aren’t outside. Staying inside for an extended period equates to a general strike. Even limited strikes are very effective. There were limited and general strikes in Tunisia and Egypt during their uprisings and they were critical.

WCFIA: A general strike seems like a personally costly way to protest, especially if you just stop working or stop buying things. Why are they effective?

CHENOWETH: This is why preparation is so essential. Where campaigns have used strikes or economic noncooperation successfully, they’ve often spent months preparing by stockpiling food, coming up with strike funds, or finding ways to engage in community mutual aid while the strike is underway. One good example of that comes from South Africa. The anti-apartheid movement organized a total boycott of white businesses, which meant that black community members were still going to work and getting a paycheck from white businesses but were not buying their products. Several months of that and the white business elites were in total crisis. They demanded that the apartheid government do something to alleviate the economic strain. With the rise of the reformist Frederik Willem de Klerk within the ruling party, South African leader P.W. Botha resigned. De Klerk was installed as president in 1989, leading to negotiations with the African National Congress [ANC] and then to free elections, where the ANC won overwhelmingly. The reason I bring the case up is because organizers in the black townships had to prepare for the long term by making sure that there were plenty of food and necessities internally to get people by, and that there were provisions for things like Christmas gifts and holidays.

WCFIA: How important is the overall number of participants in a nonviolent campaign?

CHENOWETH: One of the things that isn’t in our book, but that I analyzed later and presented in a TEDx Boulder talk in 2013 , is that a surprisingly small proportion of the population guarantees a successful campaign: just 3.5 percent. That sounds like a really small number, but in absolute terms it’s really an impressive number of people. In the U.S., it would be around 11.5 million people today. Could you imagine if 11.5 million people — that’s about three times the size of the 2017 Women’s March — were doing something like mass noncooperation in a sustained way for nine to 18 months? Things would be totally different in this country.

“Countries in which there were nonviolent campaigns were about 10 times likelier to transition to democracies within a five-year period compared to countries in which there were violent campaigns — whether the campaigns succeeded or failed.” Erica Chenoweth

WCFIA: Is there anything about our current time that dictates the need for a change in tactics?

CHENOWETH: Mobilizing without a long-term strategy or plan seems to be happening a lot right now, and that’s not what’s worked in the past. However, there’s nothing about the age we’re in that undermines the basic principles of success. I don’t think that the factors that influence success or failure are fundamentally different. Part of the reason I say that is because they’re basically the same things we observed when Gandhi was organizing in India as we do today. There are just some characteristics of our age that complicate things a bit.

WCFIA: You make the surprising claim that even when they fail, civil resistance campaigns often lead to longer-term reforms than violent campaigns do. How does that work?

CHENOWETH: The finding is that civil resistance campaigns often lead to longer-term reforms and changes that bring about democratization compared with violent campaigns. Countries in which there were nonviolent campaigns were about 10 times likelier to transition to democracies within a five-year period compared to countries in which there were violent campaigns — whether the campaigns succeeded or failed. This is because even though they “failed” in the short term, the nonviolent campaigns tended to empower moderates or reformers within the ruling elites who gradually began to initiate changes and liberalize the polity.

One of the best examples of this is the Kefaya movement in the early 2000s in Egypt. Although it failed in the short term, the experiences of different activists during that movement surely informed the ability to effectively organize during the 2011 uprisings in Egypt. Another example is the 2007 Saffron Revolution in Myanmar, which was brutally suppressed at the time but which ultimately led to voluntary democratic reforms by the government by 2012. Of course, this doesn’t mean that nonviolent campaigns always lead to democracies — or even that democracy is a cure-all for political strife. As we know, in Myanmar, relative democratization in the country’s institutions has been accompanied by extreme violence against the Rohingya community there. But it’s important to note that such cases are the exceptions rather than the norm. And democratization processes tend to be much bumpier when they occur after large-scale armed conflict instead of civil resistance campaigns, as was the case in Myanmar.

WCFIA: What are your current projects?

CHENOWETH: I’m still collecting data on nonviolent campaigns around the world. And I’m also collecting data on the nonviolent actions that are happening every day in the United States through a project called the Crowd Counting Consortium , with Jeremy Pressman of the University of Connecticut. It began in 2017, when Jeremy and I were collecting data during the Women’s March. Someone tweeted a link to our spreadsheet, and then we got tons of emails overnight from people writing in to say, “Oh, your number in Portland is too low; our protest hasn’t made the newspapers yet, but we had this many people.” There were the most incredible appeals. There was a nursing home in Encinitas, Calif., where 50 octogenarians organized an indoor women’s march with their granddaughters. Their local news had shot a video of them and they asked to be counted, and we put them in the sheet. People are very active and it’s not part of the broader public discourse about where we are as a country. I think it’s important to tell that story.

This originally appeared on the Weatherhead Center website . Part two of the series is now online.

The artwork, “Love and Revolution,” revolutionary graffiti at Saleh Selim Street on the island of Zamalek, Cairo, was photographed by Hossam el-Hamalawy on Oct. 23, 2011.

Share this article

You might like.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson discusses new memoir, ‘unlikely path’ from South Florida to Harvard to nation’s highest court

Unhappy suitor wants $70,000 engagement gift back. Now court must decide whether 1950s legal standard has outlived relevance.

Cass Sunstein suggests universities look to First Amendment as they struggle to craft rules in wake of disruptive protests

Harvard releases race data for Class of 2028

Cohort is first to be impacted by Supreme Court’s admissions ruling

Parkinson’s may take a ‘gut-first’ path

Damage to upper GI lining linked to future risk of Parkinson’s disease, says new study

High doses of Adderall may increase psychosis risk

Among those who take prescription amphetamines, 81% of cases of psychosis or mania could have been eliminated if they were not on the high dose, findings suggest

Boycotts: From the American Revolution to BDS

- First Online: 30 December 2018

Cite this chapter

- David Feldman 3

Part of the book series: Palgrave Critical Studies of Antisemitism and Racism ((PCSAR))

669 Accesses

3 Altmetric

This chapter surveys the history of boycott movements from the late eighteenth century to better understand the global campaign for boycott, divestment, and sanctions (BDS) directed against Israel. The chapter argues that boycott movements have often been both instrumental and expressive in character and have had an ambiguous relationship to the rule of law. The debate on whether or not BDS is antisemitic has drawn attention away from these other, more significant, ambiguities and tensions within the movement.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The Emergence of the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions Movement

Islamophobia and Antisemitism in the Balkans

Anti-plurality and Genocide: Hannah Arendt’s Understanding of Holocaust Perpetrators and Contemporary Holocaust Research

The origins of the movement have been traced to the World Conference Against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia, and Related Intolerance, held in Durban, South Africa in 2001, where the NGO forum called for the ‘complete and total isolation of Israel as an apartheid state’. Kenneth Marcus, The Definition of Antisemitism (Oxford, 2015), 204.

http://www.waronwant.org/bds ; https://www.alaraby.co.uk/english/blog/2016/12/10/university-of-manchester-must-follow-students-and-endorse-bds

Omar Barghouti, BDS: Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions. The Global Struggle for Palestinian Rights (Chicago, 2011), 63.

http://www.jpost.com/Opinion/BDS-is-the-modern-form-of-anti-Semitism-449415

http://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/1.577920

Joel S. Fishman, ‘The BDS message of anti-Zionism, anti-Semitism, and incitement to discrimination’, Israel Affairs , vol. 18, no. 3, (July 2012), 412–25; Gary Nelson and Gabriel Noah Brahm, The Case Against Academic Boycotts of Israel (Chicago, 2015); Maia Carter Hallward, Transnational Activism and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict (New York, 2013).

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2010/jun/24/artists-bp-protest-tate

In this regard BDS is different from the boycott of Israel pursued by Arab states. Gil Feiler, From Boycott to Economic Cooperation: The Political Economy of the Arab Boycott of Israel (London, 1988).

But not only in North America. See M. O’Dowd, ‘Politics, Patriotism and Women in Ireland, Britain and Colonial America, 1700–80’, Journal of Women’s History , vol. 22, no. 4, (2010), 15–38; On the United States, see T.H. Breen, <Emphasis Type="Italic">The Marketplace of Revolution. How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence (2004).

Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, ‘Political Protest and the World of Goods’, in: The Oxford Handbook of the American Revolution , eds. Edward Gray and Jane Kamensky, (Oxford, 2013), 75.

Breen, The Marketplace , ch. 7.

Breen, The Marketplace, xvii.

Breen, The Marketplace , 254–67; Lawrence B. Glickman, Buying Power. A History of Consumer Activism in America (Chicago, 2009), 46–8.

Clare Midgely, Women Against Slavery. The British Campaigns, 1780–1870 (London, 1992), 35–37.

Midgley, Women against Slavery , 60–2, 103–4.

Peter Gurney, ‘Exclusive Dealing in the Chartist Movement’, Labour History Review, vol. 74, no. 1, (April 2009), 90–110.

R.C. Comerford, ‘The land war and the politics of distress’. in: In A New History of Ireland. VI Ireland Under the Union II , ed. WE Vaughan, (Oxford, 1996), 28–45.

T.W. Moody, Davitt and the Irish Revolution 1848–82 (Oxford, 1982), 418–9.

The Times, 18 October 1880, 6.

Donnacha Seán Lucey, Land, Popular Politics and Agrarian Violence in Ireland: The Case of County Kerry, 1872–1886 (Dublin, 2011).

R.V. Comerford, ‘The impediments to freehold ownership of land and the character of the Irish Land War’, in: Uncertain Futures: Essays about the Irish Past for Roy Foster , ed. Senia Paseta, (Oxford, 2016), 60.

Donald Jordan, Land and Popular Politics in Ireland. County Mayo from the Plantation to the Land War (Cambridge, 1994), 221, 226–7.

R.F. Foster, Modern Ireland, 1600–1972 (London, 1988), 405–13.

Moody, Davitt, 377–81, 458.

John McKivigan, Forgotten Firebrand. James Redpath and the Making of Nineteenth-Century America (Ithaca, 2008), 159.

Glickman, Buying Power , 122–4.

Leo Wolman, The Boycott in American Trade Union (Baltimore, 1916), 24–5.

Harry Laidler, Boycotts and the Labor Struggle (New York, 1913), 58–94.

Glickman, Buying Power, 128–31.

Paula Hyman, ‘Immigrant women and consumer protest: The New York City kosher meat boycott of 1902’, American Jewish History , vol. 70, no. 1, (September 1980), 91–105.

Tehila Sasson, ‘Milking the Third World? Humanitarianism, Capitalism and Moral Economy of the Nestlé Boycott’, American Historical Review, vol. 121, no. 4, (October 2016), 1196–1224; Matthew Hilton, Prosperity for All: Consumer Activism in an Era of Glaobalization (Ithaca, 2009), ch. 5; Frank Trentmann, Empire of Things: How We Became a World of Consumers from the Fifteenth Century to the Present (London, 2016), 562–80.

Sasson, ‘Milking’, 1217.

This dimension to the practice of boycott was present from the earliest occasions, when we find collective action to restrict the markets of an individual or group of individuals as a way of effecting political or social change. Wollman, The Boycott, 12.

Maneklal H. Vakil, Boycott of British goods and foreign cloth , (Bombay, 1930), 14.

Laidler, Boycotts, 75.

Torsten Lorenz, ‘Introduction’ 11, in: Cooperatives in Ethnic Conflicts. Eastern Europe in the Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century, ed. Lorenz, (Berlin, 2006).

Miloslav Szabo, ‘Because Words are not Deeds.’ Antisemitic Practice and Nationality Politics in Upper Hungary around 1900, Quest. Issues in Contemporary Jewish History, Journal of Fondazione CDEC , no. 3, (July 2012), url: www.quest.cdecjournal.it/focus.php?id=299 , 176.

Szabo, ‘Because Words’, 179.

Klaus Richter, ‘Antisemitism, “Economic Emancipation” and the Lithuanian Co-operative movement Before World War 1’, Quest. Issues in Contemporary Jewish History, Journal of Fondazione CDEC , no. 3, (July 2012), url: www.quest.cdecjournal.it/focus.php?id=300 , 187.

M. Gottleib, ‘The anti-Nazi boycott movement in the United States: an ideological and sociological appreciation’, Jewish Social Studies , vol. 35, no. 3–4, (July–October 1973), 198–227.

James Sanders, South Africa and the International Media, 1972–79 (London, 1999), 56.

http://www.spiked-online.com/newsite/article/singling-out-israel-singling-out-the-jews/18904#.WuGteG4vxR0 ; Alan Dershowitz, The Case Against BDS: Why Singling Out Israel is Anti-Semitic and Anti-Peace (New York, 2018).

Barghouti, BDS.

Tara Zahra, ‘Zionism, emigration and East European Colonialism’, in: Colonialism and the Jews , eds. Lisa Moses Leff and Maud Mandel, (Bloomington, 2017), 166–92.

Maxim Rodinson, Israel and the Arabs (Harmondsworth, 1968) was important in establishing this formulation.

Derek J Penslar, ‘Zionism, Colonialism and Postcolonialism’, Journal of Israeli History, vol. 20, no. 2–3, (2001), 84–98.

Anthony Julius, Trials of the Diaspora . A History of Anti-Semitism in England (Oxford, 2010), 476–83.

Marcus, The Definition, 207, 213.

Marcus, The Definition, 207–9; David Feldman and Brendan McGeever, ‘Labour and antisemitism: what went wrong and what is to be done?’ https://www.independent.co.uk/news/long_reads/labour-party-antisemitism-jeremy-corbyn-jewish-left-wing-holocaust-a8306936.html

Marcus, The Definition, 207.

Marcus, The Definition, 181–5, 209.

Stephen Miller, Margaret Harris, and Colin Shindler, The Attitudes of British Jews Towards Israel (London, 2015); European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, Discrimination and Hate Crime Against Jews in EU Member States: Perceptions and Experiences (Luxembourg, 2013), 27.

Discrimination and Hate , figure 1, p. 16.

Marcus appears to concede this point: The Definition , 210.

https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2014/sep/09/gove-against-boycotting-israeli-goods-gaza-conflict ; Julius, Trials of the Diaspora, 477–82.

http://socialtextjournal.org/periscope_topic/the-academic-boycott-movement/

Bashir Bashir, ‘Reconciling historical injustices: deliberative democracy and the politics of reconcilation’, Res Publica, vol. 18, no. 2, (2012), 127–43.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of History, Classics & Archaeology, Birkbeck College – University of London, London, UK

David Feldman

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to David Feldman .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations, rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Feldman, D. (2019). Boycotts: From the American Revolution to BDS. In: Feldman, D. (eds) Boycotts Past and Present. Palgrave Critical Studies of Antisemitism and Racism. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-94872-0_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-94872-0_1

Published : 30 December 2018

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-94871-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-94872-0

eBook Packages : History History (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

15 corporate boycotts from 2019

Boycotts hold an honored place in history.

The Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott—a 13-month campaign that started in 1955 when Rosa Parks refused to move to the back of a segregated bus—fueled the nation's civil rights movement. In the 1960s, a five-year boycott of California grapes organized by Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers led to better pay and improved working conditions and union contracts for thousands of agricultural laborers. A global boycott of South Africa , with international sanctions on trade, embargos, and travel bans, spanned decades in the 20th centuryand played an indispensable role in ending the nation's apartheid system of harsh racial segregation.

The word "boycott" has its origins in an Englishman named Captain Charles Boycott , who lived in Ireland in the late 1800s and worked collecting rents for a landlord. One year during a particularly poor harvest, local tenants asked him to lower their rents, and he refused. In response, the tenants organized and ostracized him. Almost no one would speak to him, work for him, or even acknowledge him, and he eventually left. The tactic caught on and soon tenant farmers were using boycotts successfully to improve their circumstances.

Modern-day boycotts use essentially the same strategy of shunning, although these days a campaign calling for consumers to stop buying products or frequent a business can spread online across social media at unprecedented speed. A public relations misstep by a company or an unfortunate turn of phrase by a top official can prompt an avalanche of calls for a boycott within minutes.

Assessing the impact of a boycott is tricky. It may take a toll on a company's sales or stock price, but experts say the most effective result is the difficult-to-measure impact on a company's reputation . Companies like Coors Brewing Co., the target of a boycott for its anti-union policies, and Exxon, boycotted after one of its tankers ran aground in 1989 and caused a huge oil spill, were long colored by public condemnation .

Stacker has compiled a list of the 15 most significant and effective boycotts of 2019, looking at their origins, how they spread, and what impact they made.

You may also like: Billion-dollar companies that didn't exist 10 years ago

Chick-fil-A

Chick-fil-A announced in November 2019 that it would stop donating money to two religious organizations that opposed same-sex marriage and give to groups working in areas of education, homelessness, and hunger. The fast-food giant had been the target of a boycott since 2012 by LGBT-rights advocates. Some saw its change of heart as capitulation , and others saw it as a business strategy. During the boycott, the company grew to become the nation’s third-largest fast-food company, and it was repeatedly named the favorite fast-food restaurant by a leading index of 23,000 consumers.

Toyota, General Motors, Fiat Chrysler

Deciding to set its own greenhouse gas emission standards, California in November announced a boycott of automakers Toyota, General Motors, and Fiat Chrysler, who all opposed the plan. The automakers had opted to stand with the administration of President Donald Trump , which has proposed to weaken federal auto emission standards. Gov. Gavin Newsom said the state will no longer buy vehicles from the three companies. Filmmaker Michael Moore on Twitter has asked his followers, who number over 6 million, to join the boycott.

Agricultural industries in Brazil

Officials in New York City and Los Angeles in November 2019 proposed a boycott of businesses linked to the devastating fires in Brazil’s Amazon rainforests. They are calling for divestment from agricultural industries that promote deforestation and climate change. Beef is one of Brazil’s biggest exports, and environmentalists say demand for meat has moved cattle ranchers to clear the Amazon for grazing, increasing the risk of fire and cutting down trees essential to cleaning greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. The proposals have not become official city policies.

Pokémon Sword and Shield

Hard-core fans called for a boycott of the Pokémon Sword and Pokemon Shield games, complaining the new versions did not allow the transfer of many of the original characters. The game’s developer apologized but said there were technical restrictions and that Pokémon was moving in a new direction. In November, Nintendo said the games sold over 6 million units worldwide on the weekend they were launched and sold more than 2 million units in the first two days in the United States—Pokémon’s highest-grossing game launch.

Calls for a fresh boycott of Uber arose recently after the ride-sharing company's chief executive referred to Saudi Arabia's killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi as " a serious mistake " in a television interview. CEO Dara Khosrowshahi later apologized on Twitter. In France, meanwhile, calls have arisen to boycott Uber by users who say the company deleted riders' comments about sexual assault by drivers on its Instagram account. Uber in 2017 was the subject of a nationwide U.S. boycott stemming from its decision to stop surge pricing at Kennedy International Airport while local cabs were striking in protest of President Trump's immigration ban. Critics said the company was profiting from the protest, and Uber later said hundreds of thousands of consumers stopped using its platform within days.

You may also like: How many of these 50 GED test questions can you get right?

Backcountry.com

Backcountry.com , a giant vendor of outdoor goods, has been hit with a consumer boycott over its legal campaign to stop other businesses from using “backcountry” as a registered trademark with cease-and-desist letters and lawsuits. The company’s chief executive published an online apology, saying it had made a mistake and was reexamining its approach. But many of the more than 22,000 people on Facebook’s Boycott BackcountryDOTcom page want the company to go further by dropping all of its remaining legal actions and making amends to businesses and groups harmed by its strategy.

Macmillan Publishers

Libraries across America have announced boycotts of Macmillan Publishers over its policy, effective as of November 2019, of placing a two-month embargo on library e-book sales . The policy limits libraries to buying one perpetual access e-book during the first eight weeks of publication. The company said it was a move to protect book sales, but libraries argue it limits access for readers who depend upon libraries for information.

More than 1,000 musicians in 2019 signed an open letter to boycott Amazon-sponsored festivals and events in response to the online giant’s business with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and its Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency. The “ No Music for ICE! ” letter calls on Amazon to terminate all existing contracts with the military, law enforcement, and government agencies that commit human-rights abuses; stop providing cloud computing used by the government in deportations; and end projects such as its facial-recognition technology that promotes racial profiling and discrimination. The letter was triggered by the announcement of Amazon’s first music festival set for December in Las Vegas.

The University of California, Los Angeles has been the target of a three-year boycott launched by labor unions and this year, honoring the boycott, the Democratic National Committee moved a December 2019 debate that was scheduled to be held at UCLA’s Luskin School of Public Affairs. The American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees called for the speakers boycott on behalf of patient-care workers locked in a labor dispute with the university. The union says the school is outsourcing jobs to lower-paid non-union workers.

Some Fitbit users have made recent calls for a boycott of the devices after it was announced on Nov. 1, 2019, that the maker of the wearable activity trackers would be purchased by Google. Google said it would not sell users' data, but on social media Fitbit users have expressed doubts. Calls have been made for federal regulators to examine the proposed tech purchase very closely.

Workers’ rights advocates have been waging a boycott of Wendy’s over its refusal to join the Fair Food Program , an initiative that benefits farm laborers, largely in Florida. The program calls on giant buyers to pay slightly more for tomatoes and in exchange, growers pay agricultural workers at least minimum wage and adhere to certain working condition standards. This year the Wendy’s lease at the University of Michigan campus was not renewed, and local Ann Arbor officials voiced the city’s support for the three-year boycott, as have actresses Amy Schumer and Alyssa Milano .

In June 2019, consumers made calls to boycott Wayfair , the online furniture and home goods company, angered over its sale of mattresses and bunk beds to an organization that runs a detention camp in Texas for unaccompanied migrant children.The boycott was prompted by hundreds of Wayfair employees who walked off their jobs at the company’s headquarters in Boston. The company in response made a donation to the American Red Cross but calls for the boycott continue on social media.

A giant national teachers’ union threatened to boycott Walmart over its gun sales following the mass shooting in August 2019 in an El Paso, Texas Walmart that killed 22 people. Walmart a few weeks later said it would stop selling some kinds of ammunition and asked customers not to carry guns inside its stores. The company’s announcement spurred calls on social media to #BoycottWalmart by both gun opponents and enthusiasts.

Equinox, SoulCycle

A boycott of Equinox and SoulCycle started in the summer of 2019 after Stephen Ross, who owns a majority stake in Related Companies, the parent of Equinox Fitness, hosted a fundraiser for President Donald Trump. Supporters of LGBT rights said they were particularly incensed because Equinox had marketed heavily to an LGBT clientele . The fitness companies issued a statement saying they had nothing to do with the fundraiser, but independent business data showed purchases and attendance at SoulCycle dropped.

In June 2019, President Donald Trump put out a call for a boycott of AT&T so it would make "big changes" at CNN, part of Turner Broadcasting System, a division of AT&T's WarnerMedia. In a tweet, the president wrote that CNN was "All negative & so much Fake News." AT&T's stock price rose some 20% in the months that followed.

Trending Now

50 best crime tv shows of all time.

50 best colleges on the East Coast

Best black and white films of all time

50 best movies of the '60s

Exploring why consumers engage in boycotts: Toward a unified model

- Journal of Public Affairs 13(2):180-189

- 13(2):180-189

- This person is not on ResearchGate, or hasn't claimed this research yet.

- University of San Diego

- Deutsches Forschungszentrum für Künstliche Intelligenz

Abstract and Figures

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Azrul Afrillana Awaludin

- Zixuan Zhang

- Wasim Ahmad

- Aloysius Sabog

- Miloslava Chovancova

- Daniel J. Petzer

- Suvodip Sen

- J MARKETING

- James C. Anderson

- M. Friedman

- Claes Fornell

- David F. Larcker

- Sociol Soc Res

- Gilbert A. Churchill

- Adv Consum Res

- D.E. Garrett

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Abolitionism to Jim Crow

- Du Bois to Brown

- Montgomery bus boycott to the Voting Rights Act

- From Black power to the assassination of Martin Luther King

- Into the 21st century

- Black Lives Matter and Shelby County v. Holder

When did the American civil rights movement start?

- What did Martin Luther King, Jr., do?

- What is Martin Luther King, Jr., known for?

- Who did Martin Luther King, Jr., influence and in what ways?

- What was Martin Luther King’s family life like?

American civil rights movement

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- NeoK12 - Educational Videos and Games for School Kids - Civil Rights Movement

- History Learning Site - The Civil Rights Movement in America 1945 to 1968

- Library of Congress - The Civil Rights Movement

- National Humanities Center - Freedom's Story - The Civil Rights Movement: 1919-1960s

- John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum - Civil Rights Movement

- civil rights movement - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- civil rights movement - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

The American civil rights movement started in the mid-1950s. A major catalyst in the push for civil rights was in December 1955, when NAACP activist Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a public bus to a white man.

Who were some key figures of the American civil rights movement?

Martin Luther King, Jr. , was an important leader of the civil rights movement. Rosa Parks , who refused to give up her seat on a public bus to a white customer, was also important. John Lewis , a civil rights leader and politician, helped plan the March on Washington .

What did the American civil rights movement accomplish?

The American civil rights movement broke the entrenched system of racial segregation in the South and achieved crucial equal-rights legislation.

What were some major events during the American civil rights movement?

The Montgomery bus boycott , sparked by activist Rosa Parks , was an important catalyst for the civil rights movement. Other important protests and demonstrations included the Greensboro sit-in and the Freedom Rides .

What are some examples of civil rights?

Examples of civil rights include the right to vote, the right to a fair trial, the right to government services, the right to a public education, and the right to use public facilities.

Recent News