- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

Global Modernism

- Modern Literature

- Finding Articles

- Books & E-Books

- Image Resources

- Individual Artists

- Modern Architecture

- Colonialism & Postcolonialism

- Film and Video Collections

- Streaming Video Collections

- Museums, Archives, & Special Collections

Modern Literature Resources

- General Books

- Selected Books

Searches multiple literary sources, including: Dictionary of Literary Biography, Literature Criticism Online, Literature Resource Center, Scribner Writer Series, and Twayne's Authors Series. Scroll down to click on Gale's Literary Index , a master index to the major literature products published by Gale.

Full text of core scholarly journals from their beginning to approximately five years ago. Disciplines include botany, business, ecology, general science, humanities, mathematics, social sciences, statistics. Browsable by discipline and full-text searchable across all disciplines. UCLA has access to selected JSTOR e-books.

Full text of current issues (from about 1990) of scholarly journals published by university presses, chiefly in the arts, humanities and social sciences. Browsable by discipline and full-text searchable across all disciplines. UCLA has access to Muse e-books published from 2017-present, plus a selected number of other e-book titles.

- << Previous: Modern Art

- Next: Colonialism & Postcolonialism >>

- Last Updated: Aug 22, 2024 3:43 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/globalmodernism

We’re fighting to restore access to 500,000+ books in court this week. Join us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Literature in the modern world : critical essays and documents

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

467 Previews

11 Favorites

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

EPUB and PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station45.cebu on March 7, 2020

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Literature › Postmodernism

Postmodernism

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on March 31, 2016 • ( 22 )

Postmodernism broadly refers to a socio-cultural and literary theory, and a shift in perspective that has manifested in a variety of disciplines including the social sciences, art, architecture, literature, fashion, communications, and technology. It is generally agreed that the postmodern shift in perception began sometime back in the late 1950s, and is probably still continuing. Postmodernism can be associated with the power shifts and dehumanization of the post- Second World War era and the onslaught of consumer capitalism.

The very term Postmodernism implies a relation to Modernism . Modernism was an earlier aesthetic movement which was in vogue in the early decades of the twentieth century. It has often been said that Postmodernism is at once a continuation of and a break away from the Modernist stance.

Postmodernism shares many of the features of Modernism. Both schools reject the rigid boundaries between high and low art. Postmodernism even goes a step further and deliberately mixes low art with high art, the past with the future, or one genre with another. Such mixing of different, incongruous elements illustrates Postmodernism’s use of lighthearted parody, which was also used by Modernism. Both these schools also employed pastiche , which is the imitation of another’s style. Parody and pastiche serve to highlight the self-reflexivity of Modernist and Postmodernist works, which means that parody and pastiche serve to remind the reader that the work is not “real” but fictional, constructed. Modernist and Postmodernist works are also fragmented and do not easily, directly convey a solid meaning. That is, these works are consciously ambiguous and give way to multiple interpretations. The individual or subject depicted in these works is often decentred, without a central meaning or goal in life, and dehumanized, often losing individual characteristics and becoming merely the representative of an age or civilization, like Tiresias in The Waste Land .

In short, Modernism and Postmodernism give voice to the insecurities, disorientation and fragmentation of the 20th century western world. The western world, in the 20th century, began to experience this deep sense of security because it progressively lost its colonies in the Third World, worn apart by two major World Wars and found its intellectual and social foundations shaking under the impact of new social theories an developments such as Marxism and Postcolonial global migrations, new technologies and the power shift from Europe to the United States. Though both Modernism and Postmodernism employ fragmentation, discontinuity and decentredness in theme and technique, the basic dissimilarity between the two schools is hidden in this very aspect.

Modernism projects the fragmentation and decentredness of contemporary world as tragic. It laments the loss of the unity and centre of life and suggests that works of art can provide the unity, coherence, continuity and meaning that is lost in modern life. Thus Eliot laments that the modern world is an infertile wasteland, and the fragmentation, incoherence, of this world is effected in the structure of the poem. However, The Waste Land tries to recapture the lost meaning and organic unity by turning to Eastern cultures, and in the use of Tiresias as protagonist

In Postmodernism, fragmentation and disorientation is no longer tragic. Postmodernism on the other hand celebrates fragmentation. It considers fragmentation and decentredness as the only possible way of existence, and does not try to escape from these conditions.

This is where Postmodernism meets Poststructuralism —both Postmodernism and Poststructuralism recognize and accept that it is not possible to have a coherent centre . In Derridean terms, the centre is constantly moving towards the periphery and the periphery constantly moving towards the centre. In other words, the centre, which is the seat of power, is never entirely powerful. It is continually becoming powerless, while the powerless periphery continually tries to acquire power. As a result, it can be argued that there is never a centre, or that there are always multiple centres. This postponement of the centre acquiring power or retaining its position is what Derrida called differance . In Postmodernism’s celebration of fragmentation, there is thus an underlying belief in differance , a belief that unity, meaning, coherence is continually postponed.

The Postmodernist disbelief in coherence and unity points to another basic distinction between Modernism and Postmodernism. Modernism believes that coherence and unity is possible, thus emphasizing the importance of rationality and order. The basic assumption of Modernism seems to be that more rationality leads to more order, which leads a society to function better. To establish the primacy of Order, Modernism constantly creates the concept of Disorder in its depiction of the Other—which includes the non-white, non-male, non-heterosexual, non-adult, non-rational and so on. In other words, to establish the superiority of Order, Modernism creates the impression- that all marginal, peripheral, communities such as the non-white, non-male etc. are contaminated by Disorder. Postmodernism, however, goes to the other extreme. It does not say that some parts of the society illustrate Order, and that other parts illustrate Disorder. Postmodernism, in its criticism of the binary opposition, cynically even suggests that everything is Disorder.

Jean Francois Lyotard

The Modernist belief in order, stability and unity is what the Postmodernist thinker Lyotard calls a metanarrative . Modernism works through metanarratives or grand narratives, while Postmodernism questions and deconstructs metanarratives. A metanarrative is a story a culture tells itself about its beliefs and practices.

Postmodernism understands that grand narratives hide, silence and negate contradictions, instabilities and differences inherent in any social system. Postmodernism favours “mini-narratives,” stories that explain small practices and local events, without pretending universality and finality. Postmodernism realizes that history, politics and culture are grand narratives of the power-wielders, which comprise falsehoods and incomplete truths.

Having deconstructed the possibility of a stable, permanent reality, Postmodernism has revolutionized the concept of language. Modernism considered language a rational, transparent tool to represent reality and the activities of the rational mind. In the Modernist view, language is representative of thoughts and things. Here, signifiers always point to signifieds. In Postmodernism, however, there are only surfaces, no depths. A signifier has no signified here, because there is no reality to signify.

Jean Baudrillard

The French philosopher Baudrillard has conceptualized the Postmodern surface culture as a simulacrum. A simulacrum is a virtual or fake reality simulated or induced by the media or other ideological apparatuses. A simulacrum is not merely an imitation or duplication—it is the substitution of the original by a simulated, fake image. Contemporary world is a simulacrum, where reality has been thus replaced by false images. This would mean, for instance, that the Gulf war that we know from newspapers and television reports has no connection whatsoever to what can be called the “real” Iraq war. The simulated image of Gulf war has become so much more popular and real than the real war, that Baudrillard argues that the Gulf War did not take place. In other words, in the Postmodern world, there are no originals, only copies; no territories, only maps; no reality, only simulations. Here Baudrillard is not merely suggesting that the postmodern world is artificial; he is also implying that we have lost the capacity to discriminate between the real and the artificial.

Fredric Jameson

Just as we have lost touch with the reality of our life, we have also moved away from the reality of the goods we consume. If the media form one driving force of the Postmodern condition, multinational capitalism and globalization is another. Fredric Jameson has related Modernism and Postmodernism to the second and third phases of capitalism. The first phase of capitalism of the 18th -19th centuries, called Market Capitalism, witnessed the early technological development such as that of the steam-driven motor, and corresponded to the Realist phase. The early 20th century, with the development of electrical and internal combustion motors, witnessed the onset of Monopoly Capitalism and Modernism. The Postmodern era corresponds to the age of nuclear and electronic technologies and Consumer Capitalism, where the emphasis is on marketing, selling and consumption rather than production. The dehumanized, globalized world, wipes out individual and national identities, in favour of multinational marketing.

It is thus clear from this exposition that there are at least three different directions taken by Postmodernim, relating to the theories of Lyotard, Baudrillard and Jameson. Postmodernism also has its roots in the theories Habermas and Foucault . Furthermore, Postmodernism can be examined from Feminist and Post-colonial angles. Therefore, one cannot pinpoint the principles of Postmodernism with finality, because there is a plurality in the very constitution of this theory.

Postmodernism, in its denial of an objective truth or reality, forcefully advocates the theory of constructivism—the anti-essentialist argument that everything is ideologically constructed. Postmodernism finds the media to be a great deal responsible for “constructing” our identities and everyday realiites. Indeed, Postmodernism developed as a response to the contemporary boom in electronics and communications technologies and its revolutionizing of our old world order.

Constructivism invariably leads to relativism. Our identities are constructed and transformed every moment in relation to our social environment. Therefore there is scope for multiple and diverse identities, multiple truths, moral codes and views of reality.

The understanding that an objective truth does not exist has invariably led the accent of Postmodernism to fall on subjectivity. Subjectivity itself is of course plural and provisional. A stress on subjectivity will naturally lead to a renewed interest in the local and specific experiences, rather than the and universal and abstract; that is on mini-narratives rather than grand narratives.

Finally, all versions of Postmodernism rely on the method of Deconstruction to analyze socio-cultural situations. Postmodernism has often been vehemently criticized. The fundamental characteristic of Postmodernism is disbelief, which negates social and personal realities and experiences. It is easy to claim that the Gulf War or Iraq War does not exist; but then how does one account for the deaths, the loss and pain of millions of people victimized by these wars? Also, Postmodernism fosters a deep cynicism about the one sustaining force of social life—culture. By entirely washing away the ground beneath our feet, the ideological presumptions upon which human civilization is built, Postmodernism generates a feeling of lack and insecurity in contemporary societies, which is essential for the sustenance of a capitalistic world order. Finally, when the Third World began to assert itself over Euro-centric hegemonic power, Postmodernism had rushed in with the warning, that the empowerment of the periphery is but transient and temporary; and that just as Europe could not retain its imperialistic power for long, the new-found power of the erstwhile colonies is also under erasure.

In literature, postmodernism (relying heavily on fragmentation, deconstruction, playfulness, questionable narrators etc.) reacted against the Enlightenment ideas implicit in modernist literature – informed by Lyotard’s concept of the “metanarrative”, Derrida’s concept of “play”, and Budrillard’s “simulacra.” Deviating from the modernist quest for meaning in a chaotic world, the postmodern. writers eschew, often playfully, the possibility of meaning, and the postmodern novel is often a parody of this. quest. Marked by a distrust of totalizing mechanisms and self-awareness, postmodern writers often celebrate chance over craft and employ metafiction to undermine the author’s “univocation”. The distinction between high and low culture is also attacked with the employment of pastiche, the combination of multiple cultural elements including subjects and genres not previously deemed fit for literature. Postmodern literature can be considered as an umbrella term for the post-war developments in literature such as Theatre of the Absurd , Beat Generation and Magical Realism .

Postmodern literature, as expressed in the writings of Beckett, Robbe Grillet , Borges , Marquez , Naguib Mahfouz and Angela Carter rests on a recognition of the complex nature of reality and experience, the role of time and memory in human perception, of the self and the world as historical constructions, and the problematic nature of language.

Postmodern literature reached its peak in the ’60s and ’70s with the publication of Catch-22 by Joseph Heller, Lost in the Funhouse and Sot-Weed Factor by John Barth , Gravity’s Rainbow, V., and Crying of Lot 49 by Thomas Pynchon , “factions” like Armies in the Night and In Cold Blood by Norman Mailer and Truman Capote , postmodern science fiction novels like Neoromancer by William Gibson , Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut and many others. Some declared the death of postmodernism in the ’80’s with a new surge of realism represented and inspired by Raymond Carver . Tom Wolfe in his 1989 article Stalking the Billion-Footed Beas t called for a new emphasis on realism in fiction to replace postmodernism. With this new emphasis on realism in mind, some declared White Noise in (1985) or The Satanic Verses (1988) to be the last great novels of the postmodern era.

Postmodern film describes the articulation of ideas of postmodernism trough the cinematic medium – by upsetting the mainstream conventions of narrative structure and characterization and destroying (or playing with) the audience’s “suspension of disbelief,” to create a work that express through less-recognizable internal logic. Two such examples are Jane Campion ‘s Two Friends, in which the story of two school girls is shown in episodic segments arranged in reverse order; and Karel Reisz ‘s The French Lieutenant’s Woman, in which the story being played out on the screen is mirrored in the private lives of the actors playing it, which the audience also sees. However, Baudrillard dubbed Sergio Leone ‘s epic 1968 spaghetti western Once Upon a Time in the West as the first postmodern film. Other examples include Michael Winterbottom ‘s 24 Hour Party People, Federico Fellini ‘s Satyricon and Amarcord, David Lynch ‘ s Mulholland Drive, Quentin Tarantino ‘s Pulp Fiction.

In spite of the rather stretched, cynical arguments of Postmodernism, the theory has exerted a fundamental influence on late 20th century thought. It has indeed revolutionized all realms of intellectual inquiry in varying degrees.

Share this:

Categories: Literature

Tags: Amarcord , Angela Carter , Armies in the Night , Baudrillard , Beat Generation , Catch-22 , Crying of Lot 49 , Federico Fellini , Fredric Jameson , Gabriel Garcia Marquez , Gravity's Rainbow , Habermas , Jane Campion , Jorge Luis Borges , Joseph Heller , Karel Reisz , Kurt Vonnegut , Literary Criticism , Literary Theory , Lost in the Funhouse , Lyotard , Magical Realism , Marxism , metanarrative , Michael Winterbottom , Michel Foucault , Modernism , Naguib Mahfouz , Neoromancer , Norman Mailer , Once Upon a Time in the Wes , Postmodern film , Postmodernism , Raymond Carver , Robbe Grillet , Salman Rushdie , Sergio Leone , simulacrum , Sot-Weed Factor , Stalking the Billion-Footed Beas , The Satanic Verses , The Waste Land , Truman Capote , White Noise , William Gibson

Related Articles

If modernism was an aesthetic movement how come postmodernism becomes bad for society? I think modernism caused more struggle and stress for ordinary people and they found relief in postmodernism. Contemporary people always found reasons not to be part of any movements and they did nothing good or bad, it’s very strange that small groups of people make big movements in literature, movies, architecture and the rest majority are forced to read, watch and entertain. In my view, marketing play a big role here considering the fact that human races have tendency to follow and react what they see and what they hear. Reality is not just about the sufferings and losses. A moving window in a computer screen is a virtual reality. Watching and enjoying that window movement while a war is going on in some other countries is very much better than going there and being participating in it. No-one wants to think the war doesn’t exist. They know war does exist and they don’t want to make it more worse. So whenever you talk about postmodernism, make sure you are not completely against this.

So informative, expressed in limpid way

Hello Can you please add up more to your excerpts With more original, important translated articles by the theorists with examples and analysis please

Hi Kindly find this category https://literariness.org/category/postmodernism/ if you are in search of Postmodernism related articles. You could also find articles on the key theorists by just browsing through http://www.literariness.org . Thank You. Share the site with your friends

Nasrullah Mambrol

HI! how can i give references to your articles?

- Frankfurt School’s Contribution to Postmodern Thought – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Edward Said’s Orientalism – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Terry Eagleton and Marxist Literary Theory – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Shoshana Felman and Psychoanalytic Crtiticism – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Shoshana Felman and Psychoanalytic Criticism – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Homi K Bhabha and Film Thoery – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Narrative Theory – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Key Theories of Jean Francois Lyotard – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Modernism, Postmodernism and Film Criticism – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Postmodern Paranoia – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Looseness of Association in Postmodern Works – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Spatial Criticism: Critical Geography, Space, Place and Textuality – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Shakespeare and Post-Modernism – Literary Theory and Criticism Notes

- Postcolonial Novels and Novelists | Literary Theory and Criticism

- Assignment #6 – Janaina Coimbra – Tópicos de Literatura em Língua Inglesa II

- Spatial Criticism: Critical Geography, Space, Place and Textuality | Literary Theory and Criticism

- 16 David Foster Wallace Quotes to Help You Understand Life

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Forgot Your Password?

New to The Nation ? Subscribe

Print subscriber? Activate your online access

Current Issue

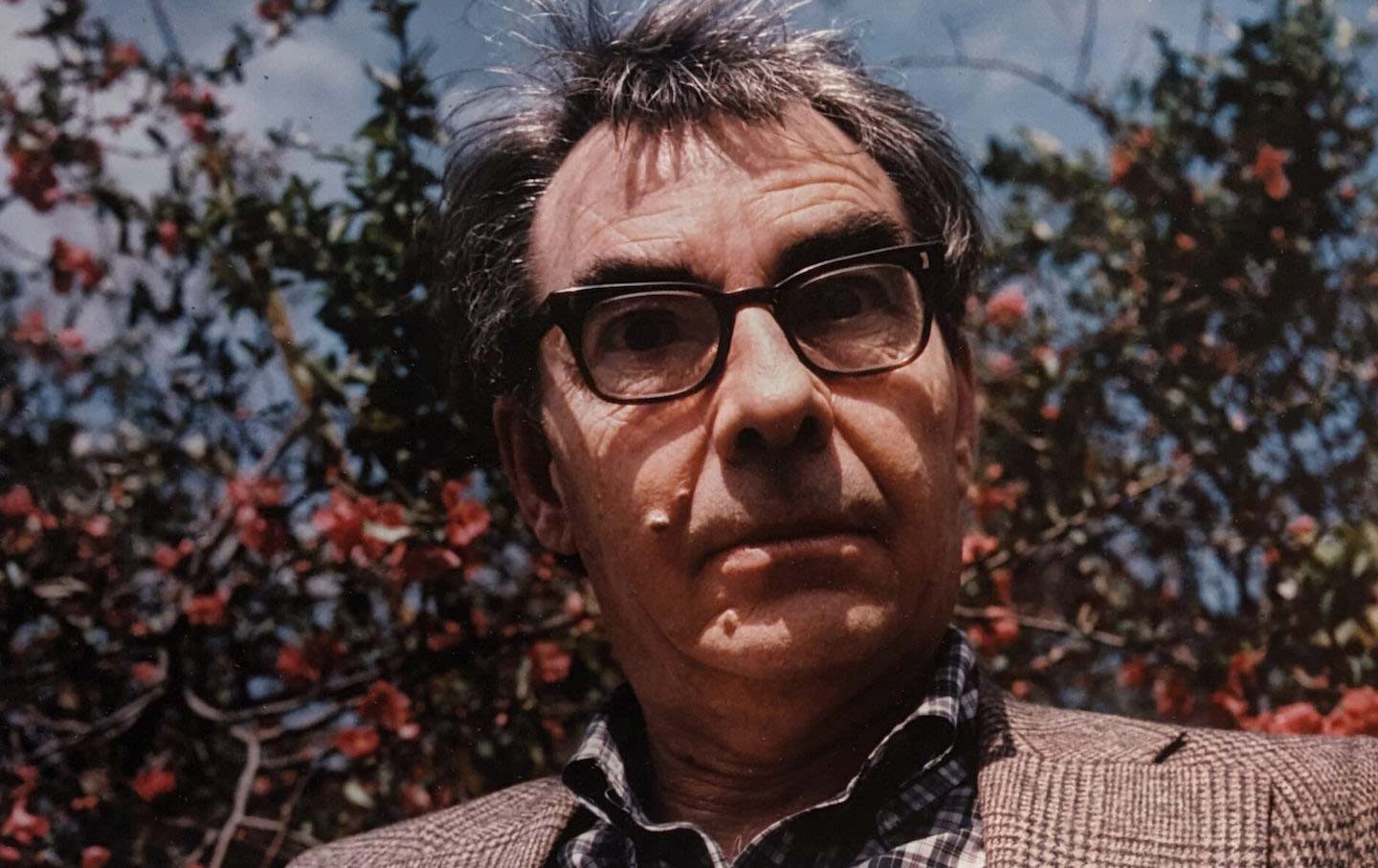

Guy Davenport—the Last High Modernist

In the essays collected in Geography of the Imagination , one can glimpse the inner workings of the mind of a 20th-century literary genius.

Whitman appearing at Poe’s funeral, toward the back. A young Picasso catching a glimpse of the prehistoric bull paintings at Altamira. Allen Ginsberg, mid-chant at Charles Olson’s funeral, accidentally pressing the pedal to lower the coffin, leaving Olson’s remains “wedged neither in nor out of the grave.” Whittaker Chambers sponsoring Louis Zukofsky’s Communist Party membership bid. Kafka observing an air show as the first pilots took flight. Emerson expressing his dismay at the dinner-table talk of Thoreau and Louis Aggasiz on the sexual habits of turtles.

Books in review

The geography of the imagination: forty essays.

These are among the meetings of the minds gathered together in Guy Davenport’s masterpiece The Geography of the Imagination , a wide-ranging collection of essays that fuses together the multifaceted author’s long engagements with his cultural ancestors . The fruits of serious time spent reading, Davenport’s gift is a kind of literary eros: His affinity for these artists is so great that, even as he brilliantly analyzes their texts, he can’t help but try to conjure them to life. Scholar, critic, and artist rolled into one, Davenport was the standard-bearer for a variety of serious belles lettres, the likes of which is rare today—who now has done so much homework? Returned to print with a new introduction by John Jeremiah Sullivan, Geography is a powerful reminder of the pleasures of erudition, and perhaps a barometer of today’s literary culture and its diminished capacity for difficulty.

For Davenport, the literary anecdote mattered; he recognized it as the “last survivor of an oral tradition.” And it was part of how his mind moved: Revolutionary ideas were embodied by great men (and, tellingly, less often women)—heroes of the past who came into contact, often fleetingly, and exchanged their genius. In his view, the flowering of culture is the product of these meetings rippling through history. Davenport himself was no stranger to these anecdotal encounters—he seems to have met a fair number of his artistic gods.

Here are some of the stories he sorts through: stumbling upon Ezra Pound’s original blueprint for The Cantos while helping the aged, mad poet move into a new apartment in Rapallo; a coffee chat with Samuel Beckett; attending boring Oxford classes taught by J.R.R. Tolkien; lunching in Kentucky with the photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard, the monk and writer Thomas Merton (“in mufti, dressed as a tobacco farmer with a tonsure”), and “an editor of Fortune who had wrecked his Hertz car coming from the airport and was covered in spattered blood from head to toe.” He reports that the restaurant treated them with impeccable manners. Perhaps more importantly, these morsels of storytelling lend Davenport’s formidable learning a voice, one with charm and humility, even a kind of boyishness (hero worship is always at hand). Moreover, they stitch together his unconventional leaps of logic and arcane references, grounding the reader even when the path of the essay may be unfamiliar.

The pleasure of reading Davenport is not just in spending time with someone who has read more widely and deeply than you have—though it’s that, too—but rather in his power of making surprising connections. The memorable lines that open the collection’s title essay propose to put all of culture, across all time, into some kind of relationship:

The difference between the Parthenon and the World Trade Center, between a French wine glass and a German beer mug, between Bach and John Philip Sousa, between Sophocles and Shakespeare, between a bicycle and a horse, though explicable by historical moment, necessity, and destiny, is before all a difference of imagination.

This assertion is, at its heart, a question of style: All cultures have buildings, beverages, music, theater, and modes of transportation, but the contrasts between them are central to how we understand ourselves and others. How these choices came to be, however, requires an investigation that can span centuries and vast distances. “Every force evolves a form,” taken from the Shakers and the seemingly inevitable simplicity of their art, is one of Davenport’s most cherished phrases—even as artists choose, forces of nature always work upon those choices. Chance and circumstance are key, but Davenport still insists on that most elusive of qualities, the imagination, to explain the particulars: People dream, guess, and suppose (to paraphrase him slightly), and these intangible urges press up against their material conditions and lead to moments of creativity. Even if you grew up in a cornfield, you might still dream of the sea.

“The imagination; that is, the way we shape and use the world, indeed the way we see the world,” Davenport writes, “has geographical boundaries like islands, continents, and countries. These boundaries can be crossed.” The title essay labors to construct an elusive third option between cultural determinism (that you are inevitably a product of your origins) and a free-floating subjectivity (that we can escape our contexts entirely). Davenport’s sprawling project as an essayist, then, is to try to track those boundary crossings and detect influences that might have escaped our notice at first. The essay’s culmination is an extended close reading of Grant Wood’s American Gothic , drawing a map out of every item in the frame. The bamboo screen from China (“by way of Sears Roebuck”), the glass from Venice, the pose of the couple out of the whole history of portraiture—this most American of images was created by a global flow of ideas and materials. Davenport’s “geography” is a kind of spatial aid to the way we think about culture: The painting isn’t just one exhibit in a long gallery of “periods” that follow one after the other. Instead, it’s a demonstration of many traditions all intertwined on the same canvas. Like a map—if one knows how to read it. And taking it all in at once is how we might begin to understand how the boundaries blur.

Another pleasure of reading Davenport is in his roaming, in never knowing his exact destination. He is just as likely to resort to simile and metaphor (“The imagination is like the drunk man who lost his watch, and must get drunk again to find it”) or swerve into a subject that is completely fascinating but also somewhat unclear in exactly how it connects to his original point. On the way to American Gothic is an extended examination of Edgar Allan Poe’s tripartite imagination: grotesque, arabesque, and classical, in Davenport’s telling. The close reading itself is elaborate and entertaining enough to quell the reader’s doubts of how, exactly, everything will fit together. Onward, then, he leaps to the Goncourt brothers, Spengler, Joyce, and so on. With Davenport, the reader is always on a journey, and it can feel good to know that there is someone a few steps ahead of you, guiding the way even if you’re temporarily lost.

Peripatetic as his writing was, Davenport was, by his own admission, someone who hated travel. He was born in South Carolina in 1927, and his Southern roots occasionally surface when his writing dips into the personal (particularly memorable is his story of being taken to his Black nurse’s house to eat clay in order to cure his indigestion). The majority of his life took place in the university: Duke, Oxford, Harvard, and eventually a post at the University of Kentucky. “The farthest away for the highest pay,” he is reported to have said. There were brief interruptions for travel as well as time spent in the US Army during the Korean War—his main memory of the latter seems to be reading Thomas Mann’s Joseph and His Brothers in the Fort Bragg rec room. Davenport would teach at Kentucky for decades, although his attitude toward the experience seems to have been ambivalent at best—he considered teaching noble in the abstract, but in practice a futile chore. Meanwhile, he toiled away inside his immense library at his brilliant and often arcane writing.

The Nation Weekly

After winning a MacArthur “genius grant” in 1990, Davenport retired to write full-time. Before his death from lung cancer at the age of 77 (he was a lifelong smoker), he was incredibly productive, with numerous volumes of essays, fiction, poetry, and translations of ancient Greek poets and philosophers to his name. He was also a painter and often an illustrator of his own work. In another essay collection, Davenport approvingly notes the wisdom of Montaigne in leaving the world of business and court intrigue to spend his days in peaceful, humanistic introspection. It’s not hard to see the older Davenport in this image: a gentleman squire, intellectually engaged but essentially aloof. He took pleasure in life outside his library, but his understanding came through the texts that structured his world.

At times, Davenport has the aura of “The Last Man Who Knew Everything,” the epithet once bestowed on the English polymath Thomas Young. However, a closer inspection shows that Davenport’s breadth of subjects, while impressive, has a focus. High modernism is his home, particularly in literature (Joyce for his master’s thesis, Pound for his PhD), though he writes compellingly about the visual arts as well. Around half of Geography ’s essays are about, or at least significantly involve, poets: Poe, Whitman, Stevens, Moore, Olson, Zukofsky, and others more obscure (a fascinating essay on the lesser-known Ronald Johnson is one of the collection’s best). In general, he is more content to root around in the text—if it is complex enough, he will find food for thought. His essays often have no fixed thesis or argument to speak of, and some of his sprawling close readings are more convincing than others: While his dissection of Olson’s famously opaque “The Kingfishers” is genuinely illuminating, his theory of Ulysses as based, chapter by chapter, on an ancient Celtic alphabet is perhaps more technically impressive than it is useful. He has many touchstones, or hobby horses, that he returns to again and again: Leonardo da Vinci (one of the first books Davenport read as a child was the artist’s biography, an obsession that seems to have molded him for a lifetime), prehistoric cave painting, Dogon theology, the ancient Greeks, Fourier, Wittgenstein, and above all, those demigods of the earlier 20th century—Picasso, Joyce, and Pound.

If “imagination” is the key to Davenport’s thinking on culture, he did not mean it in the way that it is often invoked today: a disruptive idea that strikes like a bolt from the blue. Tradition was indispensable, even inescapable, in the act of creation, he believed. In one of the collection’s most famous essays, “The Symbol of the Archaic,” Davenport provides another axiom of his thought: namely, that modernism needed to look backward, deep into the past, to advance. “What is most modern in our time frequently turns out to be the most archaic,” Davenport writes. “The sculpture of Brancusi belongs to the art of the Cyclades in the ninth century B.C. Corbusier’s buildings in their Cubist phase look like the white clay houses of Anatolia and Malta.” If The Geography of the Imagination asks us to think spatially or cross-culturally, Davenport here asserts the power of the “midden” of history, what he sees as the 20th century’s reabsorption of the past to create new, more vital work: “Archaic art, then, was springtime art in any culture.”

This attitude is itself characteristically high modernist, and Davenport saw his own style as a kind of primitivism, perhaps more in the “naïve” spirit of self-taught artists like Balthus and Henri Rousseau—the claim is debatable, but perhaps can be chalked up to Davenport’s modesty. This insight, or tension, lies at the heart of Davenport’s peculiar aesthetic: Returning to the archaic is a source of art’s freshness, but it simultaneously requires a huge scholarly apparatus to fully unwind the connections. In effect, his role as one of modernism’s great interpreters came with a downside: Davenport’s own archaic impulse, his desire to make art visceral, was always at risk of being overwhelmed by his learning.

Davenport was, of course, more than an essayist. His large body of fiction—mostly stories—has its champions, such as Sullivan. It also has its moments, but to my ears his essayistic experiments in fiction lack the grace of his “nonfiction” voice. Given that he had no real skill with character or plot, Davenport’s layerings can feel overworked, top-heavy with the relay of information in baroque language. And his conceits (Kafka, again, at the air show, or Robert Walser’s early career as a butler), which summon the hero worship that is central to his thinking, feel more at home in the realm of criticism. In “The Critic as Artist,” an essay collected elsewhere that perhaps best articulates Davenport’s own strengths, he concludes with a rather surprising cliché by his standards: “Literature does not ever say anything. It shows. It makes us feel. It is, in the world’s language, as inarticulate as music and painting. It is critics who can tell us what they think it means.” Perhaps Davenport was simply too articulate to re-create the absorption that he believed was literature’s highest achievement. His essays, which show more of his personality (though he is ultimately not a “personal essayist”), accomplish far more.

As Sullivan puts it in his breezy, pleasingly personal introduction, Davenport saw himself as “somebody who was working at the end of a civilization or tradition.” For him, “Modernism had been a cultural summit, like the Athenian Golden Age,” and now we were living “in the radioactive ash-lands of whatever that involved.” Of course, emphasizing that you stand on the shoulders of giants can tend toward diminishment—because of his density and his allusions, it’s easy to think of Davenport as a “writer’s writer.” Nostalgia can bring out the crank in him, although the stance is characteristically charming. His greatest contemporary antipathy was for the automobile, which Davenport blamed for the ravaging of American cities and culture, a quite defensible and prescient position.

Although Davenport is undoubtedly encyclopedic in many ways, it’s also worth noting what he omits—the most noticeable absence is any trace of pop culture. So many essayists today who claim a unique style (particularly those who aspire to “creative” or “literary” nonfiction) often seem duty-bound to rope in contemporary culture—Taylor Swift, say, or the latest Internet ephemera. Today, the poptimism wars are over (or, to put it differently, the “unpacking” of cultural ephemera as seen in Barthes’s Mythologies simply became the dominant form of cultural analysis), and pop won. Writers, fearing their irrelevance, feel they must insist that they belong to the “now.” Not so for Davenport: He stays firmly entrenched in his books, looking for deeper and deeper symbols in his masters. Although Davenport’s era is long past, there’s something appealing, almost romantic, in how little he fears irrelevance. Instead, he asks you to give things time: You may not understand everything in a difficult text, but that is itself the extended pleasure of reading. There will always be something further to encounter, if you choose to go on.

Davenport’s imagination always returns to Pound, that ever-troublesome modernist founding father, and a paragon of the ambiguity and density that Davenport valued. Pound is mentioned in or the subject of 26 of the 40 essays in Geography . His extreme eclecticism is perhaps the master key to Davenport’s imagination, as Pound’s best-known work, The Cantos , operates by extensive, almost uncontrollable, analogy. Incredibly disparate references are juxtaposed—Dante and Woodrow Wilson, Confucius and Odysseus—attempting to force the reader into thinking about what their relationship might be. Davenport is Pound’s ideal reader, able to grasp the threads of connection where those less booked-up might simply throw up their hands in bewilderment (and maybe for good reason). Davenport is not particularly forthcoming on Pound’s antisemitism or fascism, eliding it as madness. A political reticence, or at least mildness, is obvious. Rarely does Davenport acknowledge the perils of over-reading a text—the conspiratorial germ in Pound, for instance, is neutralized by ignoring how it might spill over into life. Complexity can be its own kind of safety, too.

As a supercharged reader, Davenport always tries to make the most of the texts he loves. Another of Geography ’s best essays is a fascinating but far-fetched dive into the work of Eudora Welty, reading her fiction largely through the myth of Persephone. The intention is to situate Welty as a major modernist in the mold of Pound or Joyce, giving deep symbolic readings of her major novels and stories. Davenport recounts elsewhere, somewhat bashfully, that Welty wrote him once to say that his interpretation did not at all conform with her own sense of her work. “Death of the author” pending, Davenport’s humility at recounting this exchange breathes warmth into the analysis. And perhaps there’s something to be grasped from this ever-deeper excavation: the unconscious patterns in art and literature that hum in the air around any enduring work.

In the literary theorist Anna Kornbluh’s recent book Immediacy , Kornbluh writes about the dominance of a contemporary style that pretends to have no style at all: autofiction, streaming television, the low-friction churn of memes and social-media posts. In our hurry to move through the flow of stuff , we have become subject to a kind of art that feeds us “effortlessness” while depleting art’s essential power to make us stop and reflect. Davenport, in his labyrinths, his constraints, his obscure references, is the model of an artist who believes in dwelling with artworks. There is a density to his writing, a willingness to embrace the uncertain and to make us work a little harder to capture the meaning or the beauty of an image.

It’s Not Too Early to Ask: Who Should Replace Merrick Garland? It’s Not Too Early to Ask: Who Should Replace Merrick Garland?

Elie Mystal

Roberts’s Rule of Disorder in Voting Rights Law Roberts’s Rule of Disorder in Voting Rights Law

David Daley

The Beltway Media Got Its Harris Interview. Can We Move on Now? The Beltway Media Got Its Harris Interview. Can We Move on Now?

The harris-walz vision for public schools the harris-walz vision for public schools.

Comment / Jennifer C. Berkshire

His work feels salutary exactly because such ambitions are increasingly rare—modernism and its ambitions are receding from our culture, warts and all. At the same time, we experience a massive crush of information every day, a circumstance that more than ever requires a mind capable of describing, or inventing, relationships between the disparate works of art that populate the feed. Davenport asks us to practice invention in our associations, to not just settle for the catch-alls of “everything” and “all the time.”

Through the effort of thinking through those connections, even when they’re perplexing, a critic—or an artist—manages to make something from the information “midden” that might otherwise have been lost. As Davenport observes in “Finding,” one of the few purely autobiographical essays in the collection, “I learned from a whole childhood of looking in fields how the purpose of things ought perhaps to remain invisible, no more than half known. People who know exactly what they are doing seem to me to miss the vital part of any doing.” To take up Davenport, we should make haste slowly. Unhurriedness, distance, the eye unfocused at first: Through these patient arts, something rare might emerge.

- Submit a correction

- Send a letter to the editor

- Reprints & permissions

Can we count on you?

In the coming election, the fate of our democracy and fundamental civil rights are on the ballot. The conservative architects of Project 2025 are scheming to institutionalize Donald Trump’s authoritarian vision across all levels of government if he should win.

We’ve already seen events that fill us with both dread and cautious optimism—throughout it all, The Nation has been a bulwark against misinformation and an advocate for bold, principled perspectives. Our dedicated writers have sat down with Kamala Harris and Bernie Sanders for interviews, unpacked the shallow right-wing populist appeals of J.D. Vance, and debated the pathway for a Democratic victory in November.

Stories like these and the one you just read are vital at this critical juncture in our country’s history. Now more than ever, we need clear-eyed and deeply reported independent journalism to make sense of the headlines and sort fact from fiction. Donate today and join our 160-year legacy of speaking truth to power and uplifting the voices of grassroots advocates.

Throughout 2024 and what is likely the defining election of our lifetimes, we need your support to continue publishing the insightful journalism you rely on.

Thank you, The Editors of The Nation

David Schurman Wallace

David Schurman Wallace is a writer living in New York City.

More from The Nation

Move Over Hollywood, Here Comes Chick-fil-A Move Over Hollywood, Here Comes Chick-fil-A

The fast-food giant is poised to move the entertainment world further to the right.

Ben Schwartz

Natasha Trethewey’s Life in Poetry and Prose Natasha Trethewey’s Life in Poetry and Prose

A work of biography, an essay on literature and memory and the South, a prose poem full of lyrical dexterity, Trethewey's latest book is like all of her others: a master study of ...

Books & the Arts / Edna Bonhomme

The Genius of Garth Greenwell The Genius of Garth Greenwell

Set abroad or at home, in unfamiliar worlds an ocean away or in an intensive care unit in Iowa, Greenwell's novels are songs of the self and of the United States as a whole.

Books & the Arts / Hannah Gold

Stay-at-Home Stay-at-Home

Poems / Matthew Buckley Smith

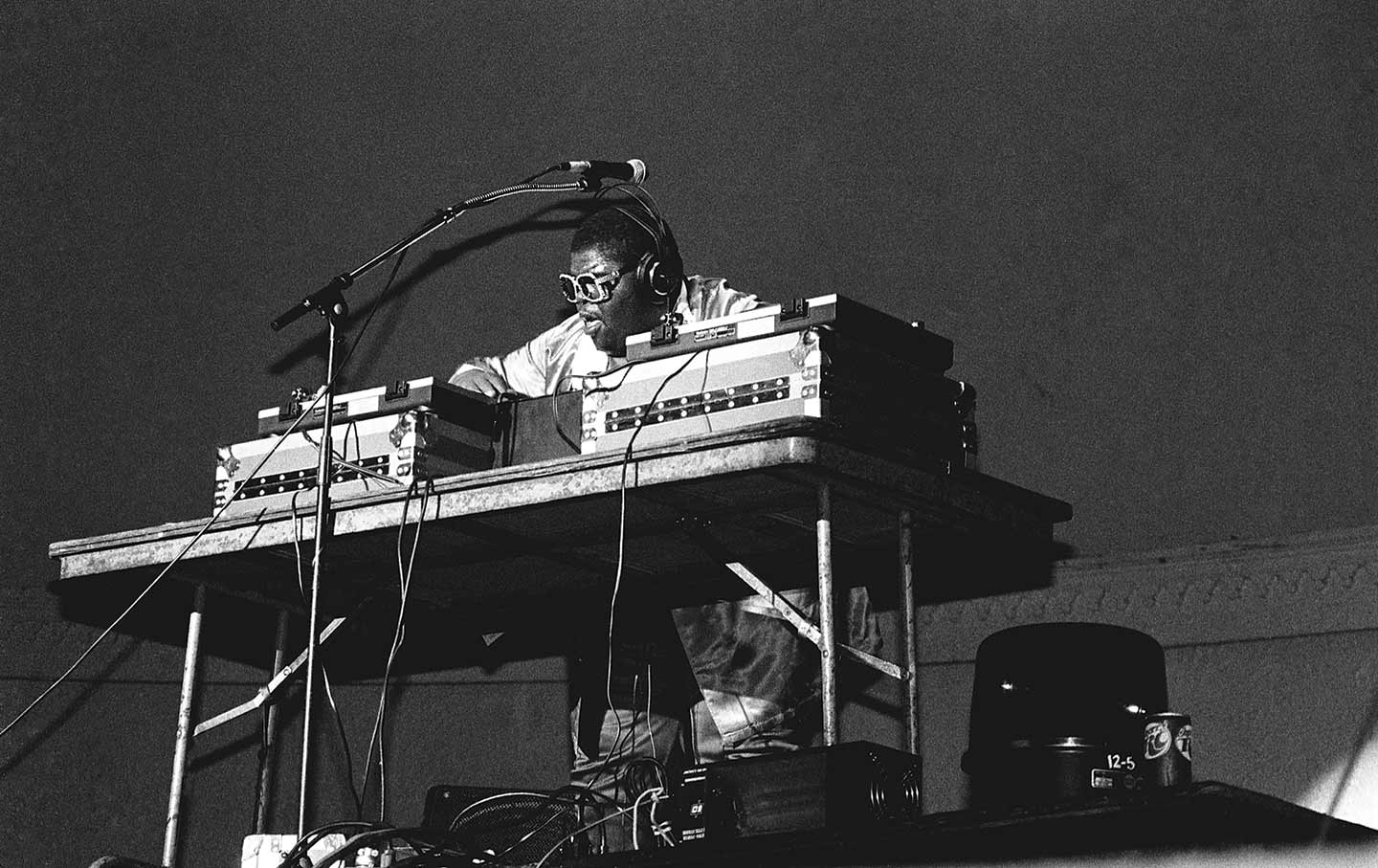

Questlove’s Personal History of Hip-Hop Questlove’s Personal History of Hip-Hop

An elegiac retelling of rap's origins, Hip-Hop Is History also ends with a sense of hope.

Books & the Arts / Bijan Stephen

Danzy Senna’s Acerbic Satires of Art and Money Danzy Senna’s Acerbic Satires of Art and Money

Having gnawed away at literary and political conventions from within their hallowed forms, Senna has now set her eyes on Hollywood.

Books & the Arts / Lovia Gyarkye

Latest from the nation

White backlash, the beltway media got its harris interview. can we move on now, i’m still hoping to vote for kamala harris, campaigns and elections, don’t underestimate donald trump’s coalition of the weird, big tech is very afraid of a very modest ai safety bill, editor's picks.

VIDEO: People in Denmark Are a Lot Happier Than People in the United States. Here’s Why.

Historical Amnesia About Slavery Is a Tool of White Supremacy

Advertisement

The 100 Best Books of the 21st Century: A Printable List

By The New York Times Books Staff Aug. 26, 2024

- Share full article

Print this version to keep track of what you’ve read and what you’d like to read. See the full project, including commentary about the books, here.

A PDF version of this document with embedded text is available at the link below:

Download the original document (pdf)

The New York Times Book Review I've I want THE 100 BEST BOOKS OF THE 21ST CENTURY read to it read it 1 My Brilliant Friend, by Elena Ferrante 26 26 Atonement, by lan McEwan 2 The Warmth of Other Suns, by Isabel Wilkerson 27 Americanah, by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie 3 Wolf Hall, by Hilary Mantel 28 Cloud Atlas, by David Mitchell 4 The Known World, by Edward P. Jones 29 The Last Samurai, by Helen DeWitt 5 The Corrections, by Jonathan Franzen 30 Sing, Unburied, Sing, by Jesmyn Ward 6 2666, by Roberto Bolaño 31 White Teeth, by Zadie Smith 7 The Underground Railroad, by Colson Whitehead 32 The Line of Beauty, by Alan Hollinghurst 8 Austerlitz, by W.G. Sebald 33 Salvage the Bones, by Jesmyn Ward 9 Never Let Me Go, by Kazuo Ishiguro 34 Citizen, by Claudia Rankine 10 Gilead, by Marilynne Robinson 35 Fun Home, by Alison Bechdel 11 The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, by Junot Díaz 36 Between the World and Me, by Ta-Nehisi Coates 12 The Year of Magical Thinking, by Joan Didion 37 The Years, by Annie Ernaux 13 The Road, by Cormac McCarthy 38 The Savage Detectives, by Roberto Bolaño 14 Outline, by Rachel Cusk 39 A Visit From the Goon Squad, by Jennifer Egan 15 Pachinko, by Min Jin Lee 40 H Is for Hawk, by Helen Macdonald 16 The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, by Michael Chabon 41 Small Things Like These, by Claire Keegan 17 The Sellout, by Paul Beatty 42 A Brief History of Seven Killings, by Marlon James 18 Lincoln in the Bardo, by George Saunders 43 Postwar, by Tony Judt 19 Say Nothing, by Patrick Radden Keefe 44 The Fifth Season, by N.K. Jemisin 20 Erasure, by Percival Everrett 45 The Argonauts, by Maggie Nelson 21 Evicted, by Matthew Desmond 46 The Goldfinch, by Donna Tartt 22 22 Behind the Beautiful Forevers, by Katherine Boo 47 A Mercy, by Toni Morrison 23 Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage, by Alice Munro 48 Persepolis, by Marjane Satrapi 24 The Overstory, by Richard Powers 49 The Vegetarian, by Han Kang 25 25 Random Family, by Adrian Nicole LeBlanc 50 Trust, by Hernan Diaz I've I want read to it read it

The New York Times Book Review I've I want THE 100 BEST BOOKS OF THE 21ST CENTURY read to it read it 51 Life After Life, by Kate Atkinson 52 52 Train Dreams, by Denis Johnson 53 Runaway, by Alice Munro 76 77 An American Marriage, by Tayari Jones 78 Septology, by Jon Fosse Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, by Gabrielle Zevin 54 Tenth of December, by George Saunders 55 The Looming Tower, by Lawrence Wright 56 The Flamethrowers, by Rachel Kushner 57 Nickel and Dimed, by Barbara Ehrenreich ཤྲཱ རྒྱ སྐྱ A Manual for Cleaning Women, by Lucia Berlin The Story of the Lost Child, by Elena Ferrante Pulphead, by John Jeremiah Sullivan. Hurricane Season, by Fernanda Melchor 58 Stay True, by Hua Hsu 83 When We Cease to Understand the World, by Benjamín Labatut 59 Middlesex, by Jeffrey Eugenides 84 The Emperor of All Maladies, by Siddhartha Mukherjee 60 Heavy, by Kiese Laymon 85 Pastoralia, by George Saunders 61 Demon Copperhead, by Barbara Kingsolver 86 Frederick Douglass, by David W. Blight 62 10:04, by Ben Lerner 87 Detransition, Baby, by Torrey Peters 63 Veronica, by Mary Gaitskill 88 The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis 64 The Great Believers, by Rebecca Makkai 89 The Return, by Hisham Matar 65 The Plot Against America, by Philip Roth 90 The Sympathizer, by Viet Thanh Nguyen 66 We the Animals, by Justin Torres 91 The Human Stain, by Philip Roth 67 Far From the Tree, by Andrew Solomon 92 The Days of Abandonment, by Elena Ferrante 68 The Friend, by Sigrid Nunez 93 Station Eleven, by Emily St. John Mandel 69 59 The New Jim Crow, by Michelle Alexander 94 On Beauty, by Zadie Smith 10 70 All Aunt Hagar's Children, by Edward P. Jones 95 Bring Up the Bodies, by Hilary Mantel 71 The Copenhagen Trilogy, by Tove Ditlevsen 96 Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, by Saidiya Hartman 72 22 Secondhand Time, by Svetlana Alexievich 97 Men We Reaped, by Jesmyn Ward 73 The Passage of Power, by Robert A. Caro 98 Bel Canto, by Ann Patchett 74 Olive Kitteridge, by Elizabeth Strout 99 How to Be Both, by Ali Smith 75 15 Exit West, by Mohsin Hamid 100 Tree of Smoke, by Denis Johnson I've I want read to it read it

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The modernism movement has many credos: Ezra Pound's exhortation to "make it new" and Virginia Woolf's assertion that sometime around December 1910 "human character changed" are but two of the most famous. It is important to remember that modernism is not a monolithic movement. There are, in fact, many modernisms, ranging from the "high" or…

Essays and criticism on Modernism - Critical Essays. (the New York Intellectuals). By the 1930s and 1940s the modernist aesthetic was taking over Anglo-American literary criticism.

The project of identifying a modernist criticism and theory is vexed not only by the imprecision and contradictory overtones of the word "modernist" but also by the category "theory.". Certainly many modernist writers wrote criticism: Virginia Woolf published hundreds of essays and reviews; W. B. Yeats's most important literary ...

It was an era of turbulence, socio-political changes and the beginning of a new world order in global politics and word order in literature and arts. Modernism thus designates a broad literary and cultural movement that spanned all of the arts and even spilled into politics and philosophy. It was the fear of an impending war that dominated the ...

Source: Greg Barnhisel, Critical Essay on Modernism, in Literary Movements for Students, The Gale Group, 2003. Cite this page as follows: "Modernism - Process Leading to Modernism."

Modernism was a literary movement that lasted from the late nineteenth century to around the mid-twentieth century, and encapsulated a series of burgeoning writing techniques that influenced the course of literary history. Get 50% off this Labor Day. Get 50% off this Labor Day. Get 50% off this Labor Day.

students a survey of literature and art in England, Ireland, and Europe at the beginning of the twentieth century. He also provides an overview of critical thought on modernism and its continuing influence on the arts today, reflecting the interests of current scholarship in the social and cultural contexts of modernism. The comparative ...

Modernist literature, then, relied especially heavily on advances in narrative technique, for narration (a voice speaking) is the essential building block of all literature. ... Critical Essays ...

Modernist literature originated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and is characterised by a self-conscious separation from traditional ways of writing in both poetry and prose fiction writing.Modernism experimented with literary form and expression, as exemplified by Ezra Pound's maxim to "Make it new." [1] This literary movement was driven by a conscious desire to overturn ...

However, a sweeping critical reassessment of literary modernism since the early 1990s has transformed the literary cartography of modernism. While the lyric and long poem (or poem sequence), modernist novel, avant‐garde play, and literary essay still hold pride of place, a new, or at least a different, set of genres¬—the manifesto ...

twentieth- and twenty-first-century literature, these essays reveal how the most innovative writers working today draw on the legacies of modernist literature. Dynamics of influence and adaptation are traced in dialogues between authors from across the twentieth cen-tury: Lawrence and A. S. Byatt, Woolf and J. M. Coetzee, Forster and Zadie Smith.

sive and authoritative overview of American literary modernism from 1890 to 1939. These original essays by twelve distinguished scholars of international reputation offer critical accounts of the major genres, literary culture, and social contexts that define the current state of modern American literature and cultural studies.

Exploring the transnational dimension of literary modernism and its increasing centrality to our understanding of 20th-century literary culture, Modernism in a Global Context surveys the key issues and debates central to the 'global turn' in contemporary Modernist Studies. ... This volume of critical essays provides the first major guide to ...

Literature in the modern world : critical essays and documents. Publication date 2004 Topics Criticism -- History -- 20th century, Literature, Modern -- 20th century -- History and criticism, Developing countries -- Literatures -- Western influences Publisher Oxford ; New York : Oxford University Press

THE MODERN WORLD Critical Essays and Documents Edited by DENNIS WALDER at the Open University OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS in association with THE OPEN UNIVERSITY ... Canon and Period 17 3 Terry Eagleton, Literature and the Rise of English 21 4 Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar, Women Poets 27 5 Edward Said, Yeats and Decolonization 34 II ...

Encyclopedia of Literary and Cultural Theory, vol. 1 (2011). He has published essays on Joyce, Yeats, Wilde, and other Irish writers, and he is currently working on an edited volume (with Patrick Bixby) on Standish O'Grady's historical works and a collection of essays under the title Modernism and the Temporalities of Irish Revival.

Postmodernism broadly refers to a socio-cultural and literary theory, and a shift in perspective that has manifested in a variety of disciplines including the social sciences, art, architecture, literature, fashion, communications, and technology. It is generally agreed that the postmodern shift in perception began sometime back in the late 1950s, and is probably still continuing.…

In the essays collected in Geography of the Imagination, one can glimpse the inner workings of the mind of a 20th-century literary genius. Whitman appearing at Poe's funeral, toward the back. A ...

(Critical essays in modern literature) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Fall of man in literature. 2. Literature, Modern-19th century-History and criticism. 3. Literature, Modern-20th century-History and criticism. 1. Title. II. Series. PN56.F2908 809' .93353 ISBN -8229-3453-1 81-11538 AACR2

Science and Modern Literature Criticism. Introduction. Representative Works. Overviews. The Dilemma of Literature in an Age of Science. Chaos as Orderly Disorder: Shifting Ground in Contemporary ...

The New York Times Book Review I've I want THE 100 BEST BOOKS OF THE 21ST CENTURY read to it read it 51 Life After Life, by Kate Atkinson 52 52 Train Dreams, by Denis Johnson 53 Runaway, by Alice ...