Research Problem vs. Research Question

What's the difference.

Research problem and research question are two essential components of any research study. The research problem refers to the issue or gap in knowledge that the researcher aims to address through their study. It identifies the area of research that requires further investigation and highlights the significance of the study. On the other hand, the research question is a specific inquiry that the researcher formulates to guide their investigation. It is a concise and focused query that helps to narrow down the research problem and provides a clear direction for the study. While the research problem sets the broader context, the research question provides a specific and measurable objective for the research study.

| Attribute | Research Problem | Research Question |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | A statement that identifies an area of concern or knowledge gap to be addressed through research. | An interrogative statement that seeks to explore or investigate a specific aspect of the research problem. |

| Focus | Identifies the broader issue or topic that needs to be studied. | Specifically targets a particular aspect or dimension of the research problem. |

| Scope | Can be broad and encompass multiple sub-issues or dimensions. | Usually narrower in scope, focusing on a specific aspect or relationship. |

| Format | Typically presented as a declarative statement. | Presented as an interrogative sentence. |

| Role | Forms the basis for the research study and guides the entire research process. | Provides a specific direction for the research study and helps in generating hypotheses. |

| Complexity | Can be complex and multifaceted, involving various factors and variables. | Can be relatively simpler, focusing on a specific aspect or relationship. |

Further Detail

Introduction.

Research is a systematic process that involves the exploration and investigation of a particular topic or issue. It aims to generate new knowledge, solve problems, or answer specific questions. In any research endeavor, it is crucial to clearly define the research problem and research question. While they are closely related, they have distinct attributes that shape the research process. This article will delve into the characteristics of research problems and research questions, highlighting their similarities and differences.

Research Problem

A research problem is the foundation of any research study. It refers to an area of concern or a gap in knowledge that requires investigation. Identifying a research problem is the initial step in the research process, as it sets the direction and purpose of the study. A research problem should be specific, clear, and well-defined to guide the research process effectively.

One of the key attributes of a research problem is that it should be significant. It should address an issue that has practical or theoretical implications and contributes to the existing body of knowledge. A significant research problem has the potential to make a positive impact on society, industry, or academia.

Furthermore, a research problem should be researchable. This means that it should be feasible to investigate and gather relevant data to address the problem. It should be within the researcher's capabilities and resources to conduct the study. A research problem that is too broad or vague may hinder the research process and lead to inconclusive results.

Additionally, a research problem should be specific and well-defined. It should clearly state the variables or concepts under investigation and provide a clear focus for the study. A well-defined research problem helps in formulating research questions and hypotheses, as it narrows down the scope of the study.

Lastly, a research problem should be original. It should contribute to the existing body of knowledge by addressing a gap or extending previous research. Originality ensures that the research study adds value and novelty to the field, making it relevant and interesting to researchers and practitioners.

Research Question

A research question is a specific inquiry that guides the research process and aims to provide an answer or solution to the research problem. It is derived from the research problem and helps in focusing the study, collecting relevant data, and analyzing the findings. A well-formulated research question is crucial for conducting a successful research study.

Similar to a research problem, a research question should be clear and specific. It should be concise and focused on a particular aspect of the research problem. A clear research question helps in determining the appropriate research design, methodology, and data collection techniques.

Furthermore, a research question should be answerable. It should be feasible to gather data and evidence to address the research question. An answerable research question ensures that the research study is practical and achievable within the given constraints.

A research question should also be relevant. It should directly relate to the research problem and contribute to the existing body of knowledge. A relevant research question ensures that the study has significance and value in the field, making it meaningful to researchers and stakeholders.

Lastly, a research question should be specific to the research context. It should consider the scope, objectives, and limitations of the study. A specific research question helps in avoiding ambiguity and ensures that the research study remains focused and coherent.

While research problems and research questions share some similarities, they also have distinct attributes that differentiate them. Both research problems and research questions should be clear, specific, and relevant to the research study. They should address a gap in knowledge and contribute to the existing body of knowledge.

However, a research problem is broader in scope compared to a research question. It sets the overall direction and purpose of the study, while a research question focuses on a specific aspect or inquiry within the research problem. A research problem provides a broader context for the study, while a research question narrows down the focus and guides the investigation.

Another difference lies in their formulation. A research problem is typically formulated as a statement or a declarative sentence, highlighting the area of concern or gap in knowledge. On the other hand, a research question is formulated as an interrogative sentence, posing a specific inquiry that needs to be answered or explored.

Furthermore, a research problem is often derived from a literature review or an analysis of existing research. It identifies the gap or area of concern based on the current state of knowledge. On the contrary, a research question is derived from the research problem itself. It is formulated to address the specific aspect or inquiry identified in the research problem.

Lastly, a research problem is usually stated at the beginning of a research study, while research questions are developed during the research design phase. The research problem sets the foundation for the study, while research questions are refined and finalized based on the research problem and objectives.

In conclusion, research problems and research questions are essential components of any research study. While they share similarities in terms of being clear, specific, and relevant, they also have distinct attributes that shape the research process. A research problem sets the overall direction and purpose of the study, while research questions focus on specific inquiries within the research problem. Both are crucial in guiding the research process, collecting relevant data, and generating new knowledge. By understanding the attributes of research problems and research questions, researchers can effectively design and conduct their studies, contributing to the advancement of knowledge in their respective fields.

Comparisons may contain inaccurate information about people, places, or facts. Please report any issues.

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- The Research Problem/Question

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A research problem is a definite or clear expression [statement] about an area of concern, a condition to be improved upon, a difficulty to be eliminated, or a troubling question that exists in scholarly literature, in theory, or within existing practice that points to a need for meaningful understanding and deliberate investigation. A research problem does not state how to do something, offer a vague or broad proposition, or present a value question. In the social and behavioral sciences, studies are most often framed around examining a problem that needs to be understood and resolved in order to improve society and the human condition.

Bryman, Alan. “The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role?” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10 (2007): 5-20; Guba, Egon G., and Yvonna S. Lincoln. “Competing Paradigms in Qualitative Research.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, editors. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994), pp. 105-117; Pardede, Parlindungan. “Identifying and Formulating the Research Problem." Research in ELT: Module 4 (October 2018): 1-13; Li, Yanmei, and Sumei Zhang. "Identifying the Research Problem." In Applied Research Methods in Urban and Regional Planning . (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2022), pp. 13-21.

Importance of...

The purpose of a problem statement is to:

- Introduce the reader to the importance of the topic being studied . The reader is oriented to the significance of the study.

- Anchors the research questions, hypotheses, or assumptions to follow . It offers a concise statement about the purpose of your paper.

- Place the topic into a particular context that defines the parameters of what is to be investigated.

- Provide the framework for reporting the results and indicates what is probably necessary to conduct the study and explain how the findings will present this information.

In the social sciences, the research problem establishes the means by which you must answer the "So What?" question. This declarative question refers to a research problem surviving the relevancy test [the quality of a measurement procedure that provides repeatability and accuracy]. Note that answering the "So What?" question requires a commitment on your part to not only show that you have reviewed the literature, but that you have thoroughly considered the significance of the research problem and its implications applied to creating new knowledge and understanding or informing practice.

To survive the "So What" question, problem statements should possess the following attributes:

- Clarity and precision [a well-written statement does not make sweeping generalizations and irresponsible pronouncements; it also does include unspecific determinates like "very" or "giant"],

- Demonstrate a researchable topic or issue [i.e., feasibility of conducting the study is based upon access to information that can be effectively acquired, gathered, interpreted, synthesized, and understood],

- Identification of what would be studied, while avoiding the use of value-laden words and terms,

- Identification of an overarching question or small set of questions accompanied by key factors or variables,

- Identification of key concepts and terms,

- Articulation of the study's conceptual boundaries or parameters or limitations,

- Some generalizability in regards to applicability and bringing results into general use,

- Conveyance of the study's importance, benefits, and justification [i.e., regardless of the type of research, it is important to demonstrate that the research is not trivial],

- Does not have unnecessary jargon or overly complex sentence constructions; and,

- Conveyance of more than the mere gathering of descriptive data providing only a snapshot of the issue or phenomenon under investigation.

Bryman, Alan. “The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role?” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10 (2007): 5-20; Brown, Perry J., Allen Dyer, and Ross S. Whaley. "Recreation Research—So What?" Journal of Leisure Research 5 (1973): 16-24; Castellanos, Susie. Critical Writing and Thinking. The Writing Center. Dean of the College. Brown University; Ellis, Timothy J. and Yair Levy Nova. "Framework of Problem-Based Research: A Guide for Novice Researchers on the Development of a Research-Worthy Problem." Informing Science: the International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 11 (2008); Thesis and Purpose Statements. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Thesis Statements. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Selwyn, Neil. "‘So What?’…A Question that Every Journal Article Needs to Answer." Learning, Media, and Technology 39 (2014): 1-5; Shoket, Mohd. "Research Problem: Identification and Formulation." International Journal of Research 1 (May 2014): 512-518.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Types and Content

There are four general conceptualizations of a research problem in the social sciences:

- Casuist Research Problem -- this type of problem relates to the determination of right and wrong in questions of conduct or conscience by analyzing moral dilemmas through the application of general rules and the careful distinction of special cases.

- Difference Research Problem -- typically asks the question, “Is there a difference between two or more groups or treatments?” This type of problem statement is used when the researcher compares or contrasts two or more phenomena. This a common approach to defining a problem in the clinical social sciences or behavioral sciences.

- Descriptive Research Problem -- typically asks the question, "what is...?" with the underlying purpose to describe the significance of a situation, state, or existence of a specific phenomenon. This problem is often associated with revealing hidden or understudied issues.

- Relational Research Problem -- suggests a relationship of some sort between two or more variables to be investigated. The underlying purpose is to investigate specific qualities or characteristics that may be connected in some way.

A problem statement in the social sciences should contain :

- A lead-in that helps ensure the reader will maintain interest over the study,

- A declaration of originality [e.g., mentioning a knowledge void or a lack of clarity about a topic that will be revealed in the literature review of prior research],

- An indication of the central focus of the study [establishing the boundaries of analysis], and

- An explanation of the study's significance or the benefits to be derived from investigating the research problem.

NOTE: A statement describing the research problem of your paper should not be viewed as a thesis statement that you may be familiar with from high school. Given the content listed above, a description of the research problem is usually a short paragraph in length.

II. Sources of Problems for Investigation

The identification of a problem to study can be challenging, not because there's a lack of issues that could be investigated, but due to the challenge of formulating an academically relevant and researchable problem which is unique and does not simply duplicate the work of others. To facilitate how you might select a problem from which to build a research study, consider these sources of inspiration:

Deductions from Theory This relates to deductions made from social philosophy or generalizations embodied in life and in society that the researcher is familiar with. These deductions from human behavior are then placed within an empirical frame of reference through research. From a theory, the researcher can formulate a research problem or hypothesis stating the expected findings in certain empirical situations. The research asks the question: “What relationship between variables will be observed if theory aptly summarizes the state of affairs?” One can then design and carry out a systematic investigation to assess whether empirical data confirm or reject the hypothesis, and hence, the theory.

Interdisciplinary Perspectives Identifying a problem that forms the basis for a research study can come from academic movements and scholarship originating in disciplines outside of your primary area of study. This can be an intellectually stimulating exercise. A review of pertinent literature should include examining research from related disciplines that can reveal new avenues of exploration and analysis. An interdisciplinary approach to selecting a research problem offers an opportunity to construct a more comprehensive understanding of a very complex issue that any single discipline may be able to provide.

Interviewing Practitioners The identification of research problems about particular topics can arise from formal interviews or informal discussions with practitioners who provide insight into new directions for future research and how to make research findings more relevant to practice. Discussions with experts in the field, such as, teachers, social workers, health care providers, lawyers, business leaders, etc., offers the chance to identify practical, “real world” problems that may be understudied or ignored within academic circles. This approach also provides some practical knowledge which may help in the process of designing and conducting your study.

Personal Experience Don't undervalue your everyday experiences or encounters as worthwhile problems for investigation. Think critically about your own experiences and/or frustrations with an issue facing society or related to your community, your neighborhood, your family, or your personal life. This can be derived, for example, from deliberate observations of certain relationships for which there is no clear explanation or witnessing an event that appears harmful to a person or group or that is out of the ordinary.

Relevant Literature The selection of a research problem can be derived from a thorough review of pertinent research associated with your overall area of interest. This may reveal where gaps exist in understanding a topic or where an issue has been understudied. Research may be conducted to: 1) fill such gaps in knowledge; 2) evaluate if the methodologies employed in prior studies can be adapted to solve other problems; or, 3) determine if a similar study could be conducted in a different subject area or applied in a different context or to different study sample [i.e., different setting or different group of people]. Also, authors frequently conclude their studies by noting implications for further research; read the conclusion of pertinent studies because statements about further research can be a valuable source for identifying new problems to investigate. The fact that a researcher has identified a topic worthy of further exploration validates the fact it is worth pursuing.

III. What Makes a Good Research Statement?

A good problem statement begins by introducing the broad area in which your research is centered, gradually leading the reader to the more specific issues you are investigating. The statement need not be lengthy, but a good research problem should incorporate the following features:

1. Compelling Topic The problem chosen should be one that motivates you to address it but simple curiosity is not a good enough reason to pursue a research study because this does not indicate significance. The problem that you choose to explore must be important to you, but it must also be viewed as important by your readers and to a the larger academic and/or social community that could be impacted by the results of your study. 2. Supports Multiple Perspectives The problem must be phrased in a way that avoids dichotomies and instead supports the generation and exploration of multiple perspectives. A general rule of thumb in the social sciences is that a good research problem is one that would generate a variety of viewpoints from a composite audience made up of reasonable people. 3. Researchability This isn't a real word but it represents an important aspect of creating a good research statement. It seems a bit obvious, but you don't want to find yourself in the midst of investigating a complex research project and realize that you don't have enough prior research to draw from for your analysis. There's nothing inherently wrong with original research, but you must choose research problems that can be supported, in some way, by the resources available to you. If you are not sure if something is researchable, don't assume that it isn't if you don't find information right away--seek help from a librarian !

NOTE: Do not confuse a research problem with a research topic. A topic is something to read and obtain information about, whereas a problem is something to be solved or framed as a question raised for inquiry, consideration, or solution, or explained as a source of perplexity, distress, or vexation. In short, a research topic is something to be understood; a research problem is something that needs to be investigated.

IV. Asking Analytical Questions about the Research Problem

Research problems in the social and behavioral sciences are often analyzed around critical questions that must be investigated. These questions can be explicitly listed in the introduction [i.e., "This study addresses three research questions about women's psychological recovery from domestic abuse in multi-generational home settings..."], or, the questions are implied in the text as specific areas of study related to the research problem. Explicitly listing your research questions at the end of your introduction can help in designing a clear roadmap of what you plan to address in your study, whereas, implicitly integrating them into the text of the introduction allows you to create a more compelling narrative around the key issues under investigation. Either approach is appropriate.

The number of questions you attempt to address should be based on the complexity of the problem you are investigating and what areas of inquiry you find most critical to study. Practical considerations, such as, the length of the paper you are writing or the availability of resources to analyze the issue can also factor in how many questions to ask. In general, however, there should be no more than four research questions underpinning a single research problem.

Given this, well-developed analytical questions can focus on any of the following:

- Highlights a genuine dilemma, area of ambiguity, or point of confusion about a topic open to interpretation by your readers;

- Yields an answer that is unexpected and not obvious rather than inevitable and self-evident;

- Provokes meaningful thought or discussion;

- Raises the visibility of the key ideas or concepts that may be understudied or hidden;

- Suggests the need for complex analysis or argument rather than a basic description or summary; and,

- Offers a specific path of inquiry that avoids eliciting generalizations about the problem.

NOTE: Questions of how and why concerning a research problem often require more analysis than questions about who, what, where, and when. You should still ask yourself these latter questions, however. Thinking introspectively about the who, what, where, and when of a research problem can help ensure that you have thoroughly considered all aspects of the problem under investigation and helps define the scope of the study in relation to the problem.

V. Mistakes to Avoid

Beware of circular reasoning! Do not state the research problem as simply the absence of the thing you are suggesting. For example, if you propose the following, "The problem in this community is that there is no hospital," this only leads to a research problem where:

- The need is for a hospital

- The objective is to create a hospital

- The method is to plan for building a hospital, and

- The evaluation is to measure if there is a hospital or not.

This is an example of a research problem that fails the "So What?" test . In this example, the problem does not reveal the relevance of why you are investigating the fact there is no hospital in the community [e.g., perhaps there's a hospital in the community ten miles away]; it does not elucidate the significance of why one should study the fact there is no hospital in the community [e.g., that hospital in the community ten miles away has no emergency room]; the research problem does not offer an intellectual pathway towards adding new knowledge or clarifying prior knowledge [e.g., the county in which there is no hospital already conducted a study about the need for a hospital, but it was conducted ten years ago]; and, the problem does not offer meaningful outcomes that lead to recommendations that can be generalized for other situations or that could suggest areas for further research [e.g., the challenges of building a new hospital serves as a case study for other communities].

Alvesson, Mats and Jörgen Sandberg. “Generating Research Questions Through Problematization.” Academy of Management Review 36 (April 2011): 247-271 ; Choosing and Refining Topics. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; D'Souza, Victor S. "Use of Induction and Deduction in Research in Social Sciences: An Illustration." Journal of the Indian Law Institute 24 (1982): 655-661; Ellis, Timothy J. and Yair Levy Nova. "Framework of Problem-Based Research: A Guide for Novice Researchers on the Development of a Research-Worthy Problem." Informing Science: the International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 11 (2008); How to Write a Research Question. The Writing Center. George Mason University; Invention: Developing a Thesis Statement. The Reading/Writing Center. Hunter College; Problem Statements PowerPoint Presentation. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Procter, Margaret. Using Thesis Statements. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Shoket, Mohd. "Research Problem: Identification and Formulation." International Journal of Research 1 (May 2014): 512-518; Trochim, William M.K. Problem Formulation. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Thesis and Purpose Statements. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Thesis Statements. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Pardede, Parlindungan. “Identifying and Formulating the Research Problem." Research in ELT: Module 4 (October 2018): 1-13; Walk, Kerry. Asking an Analytical Question. [Class handout or worksheet]. Princeton University; White, Patrick. Developing Research Questions: A Guide for Social Scientists . New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2009; Li, Yanmei, and Sumei Zhang. "Identifying the Research Problem." In Applied Research Methods in Urban and Regional Planning . (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2022), pp. 13-21.

- << Previous: Background Information

- Next: Theoretical Framework >>

- Last Updated: Sep 4, 2024 9:40 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Research Problem vs. Research Question: What's the Difference?

Key Differences

Comparison chart, formulation, role in research, research problem and research question definitions, research problem, research question, what makes a good research question, what is a research problem, can a research problem lead to multiple research questions, why is identifying a research problem important, should a research problem be solvable, is the research problem part of the research proposal, how is a research question different from a research problem, what role does literature review play in defining a research problem, how specific should a research question be, can a research problem be too broad, can a research problem be theoretical, how does one validate a research problem, how does one identify a research problem, why is clarity important in a research problem, do all research questions require empirical data, what impact does the research problem have on methodology, is the research problem always stated explicitly in a study, can research questions evolve during a study, how is a research question formulated, what is the relationship between a research problem and hypothesis.

Trending Comparisons

Popular Comparisons

New Comparisons

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What is a Research Problem? Characteristics, Types, and Examples

A research problem is a gap in existing knowledge, a contradiction in an established theory, or a real-world challenge that a researcher aims to address in their research. It is at the heart of any scientific inquiry, directing the trajectory of an investigation. The statement of a problem orients the reader to the importance of the topic, sets the problem into a particular context, and defines the relevant parameters, providing the framework for reporting the findings. Therein lies the importance of research problem s.

The formulation of well-defined research questions is central to addressing a research problem . A research question is a statement made in a question form to provide focus, clarity, and structure to the research endeavor. This helps the researcher design methodologies, collect data, and analyze results in a systematic and coherent manner. A study may have one or more research questions depending on the nature of the study.

Identifying and addressing a research problem is very important. By starting with a pertinent problem , a scholar can contribute to the accumulation of evidence-based insights, solutions, and scientific progress, thereby advancing the frontier of research. Moreover, the process of formulating research problems and posing pertinent research questions cultivates critical thinking and hones problem-solving skills.

Table of Contents

What is a Research Problem ?

Before you conceive of your project, you need to ask yourself “ What is a research problem ?” A research problem definition can be broadly put forward as the primary statement of a knowledge gap or a fundamental challenge in a field, which forms the foundation for research. Conversely, the findings from a research investigation provide solutions to the problem .

A research problem guides the selection of approaches and methodologies, data collection, and interpretation of results to find answers or solutions. A well-defined problem determines the generation of valuable insights and contributions to the broader intellectual discourse.

Characteristics of a Research Problem

Knowing the characteristics of a research problem is instrumental in formulating a research inquiry; take a look at the five key characteristics below:

Novel : An ideal research problem introduces a fresh perspective, offering something new to the existing body of knowledge. It should contribute original insights and address unresolved matters or essential knowledge.

Significant : A problem should hold significance in terms of its potential impact on theory, practice, policy, or the understanding of a particular phenomenon. It should be relevant to the field of study, addressing a gap in knowledge, a practical concern, or a theoretical dilemma that holds significance.

Feasible: A practical research problem allows for the formulation of hypotheses and the design of research methodologies. A feasible research problem is one that can realistically be investigated given the available resources, time, and expertise. It should not be too broad or too narrow to explore effectively, and should be measurable in terms of its variables and outcomes. It should be amenable to investigation through empirical research methods, such as data collection and analysis, to arrive at meaningful conclusions A practical research problem considers budgetary and time constraints, as well as limitations of the problem . These limitations may arise due to constraints in methodology, resources, or the complexity of the problem.

Clear and specific : A well-defined research problem is clear and specific, leaving no room for ambiguity; it should be easily understandable and precisely articulated. Ensuring specificity in the problem ensures that it is focused, addresses a distinct aspect of the broader topic and is not vague.

Rooted in evidence: A good research problem leans on trustworthy evidence and data, while dismissing unverifiable information. It must also consider ethical guidelines, ensuring the well-being and rights of any individuals or groups involved in the study.

Types of Research Problems

Across fields and disciplines, there are different types of research problems . We can broadly categorize them into three types.

- Theoretical research problems

Theoretical research problems deal with conceptual and intellectual inquiries that may not involve empirical data collection but instead seek to advance our understanding of complex concepts, theories, and phenomena within their respective disciplines. For example, in the social sciences, research problem s may be casuist (relating to the determination of right and wrong in questions of conduct or conscience), difference (comparing or contrasting two or more phenomena), descriptive (aims to describe a situation or state), or relational (investigating characteristics that are related in some way).

Here are some theoretical research problem examples :

- Ethical frameworks that can provide coherent justifications for artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms, especially in contexts involving autonomous decision-making and moral agency.

- Determining how mathematical models can elucidate the gradual development of complex traits, such as intricate anatomical structures or elaborate behaviors, through successive generations.

- Applied research problems

Applied or practical research problems focus on addressing real-world challenges and generating practical solutions to improve various aspects of society, technology, health, and the environment.

Here are some applied research problem examples :

- Studying the use of precision agriculture techniques to optimize crop yield and minimize resource waste.

- Designing a more energy-efficient and sustainable transportation system for a city to reduce carbon emissions.

- Action research problems

Action research problems aim to create positive change within specific contexts by involving stakeholders, implementing interventions, and evaluating outcomes in a collaborative manner.

Here are some action research problem examples :

- Partnering with healthcare professionals to identify barriers to patient adherence to medication regimens and devising interventions to address them.

- Collaborating with a nonprofit organization to evaluate the effectiveness of their programs aimed at providing job training for underserved populations.

These different types of research problems may give you some ideas when you plan on developing your own.

How to Define a Research Problem

You might now ask “ How to define a research problem ?” These are the general steps to follow:

- Look for a broad problem area: Identify under-explored aspects or areas of concern, or a controversy in your topic of interest. Evaluate the significance of addressing the problem in terms of its potential contribution to the field, practical applications, or theoretical insights.

- Learn more about the problem: Read the literature, starting from historical aspects to the current status and latest updates. Rely on reputable evidence and data. Be sure to consult researchers who work in the relevant field, mentors, and peers. Do not ignore the gray literature on the subject.

- Identify the relevant variables and how they are related: Consider which variables are most important to the study and will help answer the research question. Once this is done, you will need to determine the relationships between these variables and how these relationships affect the research problem .

- Think of practical aspects : Deliberate on ways that your study can be practical and feasible in terms of time and resources. Discuss practical aspects with researchers in the field and be open to revising the problem based on feedback. Refine the scope of the research problem to make it manageable and specific; consider the resources available, time constraints, and feasibility.

- Formulate the problem statement: Craft a concise problem statement that outlines the specific issue, its relevance, and why it needs further investigation.

- Stick to plans, but be flexible: When defining the problem , plan ahead but adhere to your budget and timeline. At the same time, consider all possibilities and ensure that the problem and question can be modified if needed.

Key Takeaways

- A research problem concerns an area of interest, a situation necessitating improvement, an obstacle requiring eradication, or a challenge in theory or practical applications.

- The importance of research problem is that it guides the research and helps advance human understanding and the development of practical solutions.

- Research problem definition begins with identifying a broad problem area, followed by learning more about the problem, identifying the variables and how they are related, considering practical aspects, and finally developing the problem statement.

- Different types of research problems include theoretical, applied, and action research problems , and these depend on the discipline and nature of the study.

- An ideal problem is original, important, feasible, specific, and based on evidence.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is it important to define a research problem?

Identifying potential issues and gaps as research problems is important for choosing a relevant topic and for determining a well-defined course of one’s research. Pinpointing a problem and formulating research questions can help researchers build their critical thinking, curiosity, and problem-solving abilities.

How do I identify a research problem?

Identifying a research problem involves recognizing gaps in existing knowledge, exploring areas of uncertainty, and assessing the significance of addressing these gaps within a specific field of study. This process often involves thorough literature review, discussions with experts, and considering practical implications.

Can a research problem change during the research process?

Yes, a research problem can change during the research process. During the course of an investigation a researcher might discover new perspectives, complexities, or insights that prompt a reevaluation of the initial problem. The scope of the problem, unforeseen or unexpected issues, or other limitations might prompt some tweaks. You should be able to adjust the problem to ensure that the study remains relevant and aligned with the evolving understanding of the subject matter.

How does a research problem relate to research questions or hypotheses?

A research problem sets the stage for the study. Next, research questions refine the direction of investigation by breaking down the broader research problem into manageable components. Research questions are formulated based on the problem , guiding the investigation’s scope and objectives. The hypothesis provides a testable statement to validate or refute within the research process. All three elements are interconnected and work together to guide the research.

R Discovery is a literature search and research reading platform that accelerates your research discovery journey by keeping you updated on the latest, most relevant scholarly content. With 250M+ research articles sourced from trusted aggregators like CrossRef, Unpaywall, PubMed, PubMed Central, Open Alex and top publishing houses like Springer Nature, JAMA, IOP, Taylor & Francis, NEJM, BMJ, Karger, SAGE, Emerald Publishing and more, R Discovery puts a world of research at your fingertips.

Try R Discovery Prime FREE for 1 week or upgrade at just US$72 a year to access premium features that let you listen to research on the go, read in your language, collaborate with peers, auto sync with reference managers, and much more. Choose a simpler, smarter way to find and read research – Download the app and start your free 7-day trial today !

Related Posts

What is Research Impact: Types and Tips for Academics

Research in Shorts: R Discovery’s New Feature Helps Academics Assess Relevant Papers in 2mins

Organizing Academic Research Papers: The Research Problem/Question

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Executive Summary

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tertiary Sources

- What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Annotated Bibliography

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- How to Manage Group Projects

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Essays

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Acknowledgements

A research problem is a statement about an area of concern, a condition to be improved, a difficulty to be eliminated, or a troubling question that exists in scholarly literature, in theory, or in practice that points to the need for meaningful understanding and deliberate investigation. In some social science disciplines the research problem is typically posed in the form of a question. A research problem does not state how to do something, offer a vague or broad proposition, or present a value question.

Importance of...

The purpose of a problem statement is to:

- Introduce the reader to the importance of the topic being studied . The reader is oriented to the significance of the study and the research questions or hypotheses to follow.

- Places the problem into a particular context that defines the parameters of what is to be investigated.

- Provides the framework for reporting the results and indicates what is probably necessary to conduct the study and explain how the findings will present this information.

In the social sciences, the research problem establishes the means by which you must answer the "So What?" question. The "So What?" question refers to a research problem surviving the relevancy test [the quality of a measurement procedure that provides repeatability and accuracy]. Note that answering the "So What" question requires a commitment on your part to not only show that you have researched the material, but that you have thought about its significance.

To survive the "So What" question, problem statements should possess the following attributes:

- Clarity and precision [a well-written statement does not make sweeping generalizations and irresponsible statements],

- Identification of what would be studied, while avoiding the use of value-laden words and terms,

- Identification of an overarching question and key factors or variables,

- Identification of key concepts and terms,

- Articulation of the study's boundaries or parameters,

- Some generalizability in regards to applicability and bringing results into general use,

- Conveyance of the study's importance, benefits, and justification [regardless of the type of research, it is important to address the “so what” question by demonstrating that the research is not trivial],

- Does not have unnecessary jargon; and,

- Conveyance of more than the mere gathering of descriptive data providing only a snapshot of the issue or phenomenon under investigation.

Castellanos, Susie. Critical Writing and Thinking . The Writing Center. Dean of the College. Brown University; Ellis, Timothy J. and Yair Levy Nova Framework of Problem-Based Research: A Guide for Novice Researchers on the Development of a Research-Worthy Problem. Informing Science: the International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 11 (2008); Thesis and Purpose Statements . The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Thesis Statements . The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements . The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Types and Content

There are four general conceptualizations of a research problem in the social sciences:

- Casuist Research Problem -- this type of problem relates to the determination of right and wrong in questions of conduct or conscience by analyzing moral dilemmas through the application of general rules and the careful distinction of special cases.

- Difference Research Problem -- typically asks the question, “Is there a difference between two or more groups or treatments?” This type of problem statement is used when the researcher compares or contrasts two or more phenomena.

- Descriptive Research Problem -- typically asks the question, "what is...?" with the underlying purpose to describe a situation, state, or existence of a specific phenomenon.

- Relational Research Problem -- suggests a relationship of some sort between two or more variables to be investigated. The underlying purpose is to investigate qualities/characteristics that are connected in some way.

A problem statement in the social sciences should contain :

- A lead-in that helps ensure the reader will maintain interest over the study

- A declaration of originality [e.g., mentioning a knowledge void, which would be supported by the literature review]

- An indication of the central focus of the study, and

- An explanation of the study's significance or the benefits to be derived from an investigating the problem.

II. Sources of Problems for Investigation

Identifying a problem to study can be challenging, not because there is a lack of issues that could be investigated, but due to pursuing a goal of formulating a socially relevant and researchable problem statement that is unique and does not simply duplicate the work of others. To facilitate how you might select a problem from which to build a research study, consider these three broad sources of inspiration:

Deductions from Theory This relates to deductions made from social philosophy or generalizations embodied in life in society that the researcher is familiar with. These deductions from human behavior are then fitted within an empirical frame of reference through research. From a theory, the research can formulate a research problem or hypothesis stating the expected findings in certain empirical situations. The research asks the question: “What relationship between variables will be observed if theory aptly summarizes the state of affairs?” One can then design and carry out a systematic investigation to assess whether empirical data confirm or reject the hypothesis and hence the theory.

Interdisciplinary Perspectives Identifying a problem that forms the basis for a research study can come from academic movements and scholarship originating in disciplines outside of your primary area of study. A review of pertinent literature should include examining research from related disciplines, which can expose you to new avenues of exploration and analysis. An interdisciplinary approach to selecting a research problem offers an opportunity to construct a more comprehensive understanding of a very complex issue than any single discipline might provide.

Interviewing Practitioners The identification of research problems about particular topics can arise from formal or informal discussions with practitioners who provide insight into new directions for future research and how to make research findings increasingly relevant to practice. Discussions with experts in the field, such as, teachers, social workers, health care providers, etc., offers the chance to identify practical, “real worl” problems that may be understudied or ignored within academic circles. This approach also provides some practical knowledge which may help in the process of designing and conducting your study.

Personal Experience Your everyday experiences can give rise to worthwhile problems for investigation. Think critically about your own experiences and/or frustrations with an issue facing society, your community, or in your neighborhood. This can be derived, for example, from deliberate observations of certain relationships for which there is no clear explanation or witnessing an event that appears harmful to a person or group or that is out of the ordinary.

Relevant Literature The selection of a research problem can often be derived from an extensive and thorough review of pertinent research associated with your overall area of interest. This may reveal where gaps remain in our understanding of a topic. Research may be conducted to: 1) fill such gaps in knowledge; 2) evaluate if the methodologies employed in prior studies can be adapted to solve other problems; or, 3) determine if a similar study could be conducted in a different subject area or applied to different study sample [i.e., different groups of people]. Also, authors frequently conclude their studies by noting implications for further research; this can also be a valuable source of problems to investigate.

III. What Makes a Good Research Statement?

A good problem statement begins by introducing the broad area in which your research is centered and then gradually leads the reader to the more narrow questions you are posing. The statement need not be lengthy but a good research problem should incorporate the following features:

Compelling topic Simple curiosity is not a good enough reason to pursue a research study. The problem that you choose to explore must be important to you and to a larger community you share. The problem chosen must be one that motivates you to address it. Supports multiple perspectives The problem most be phrased in a way that avoids dichotomies and instead supports the generation and exploration of multiple perspectives. A general rule of thumb is that a good research problem is one that would generate a variety of viewpoints from a composite audience made up of reasonable people. Researchable It seems a bit obvious, but you don't want to find yourself in the midst of investigating a complex research project and realize that you don't have much to draw on for your research. Choose research problems that can be supported by the resources available to you. Not sure? Seek out help from a librarian!

NOTE: Do not confuse a research problem with a research topic. A topic is something to read and obtain information about whereas a problem is something to solve or framed as a question that must be answered.

IV. Mistakes to Avoid

Beware of circular reasoning . Don’t state that the research problem as simply the absence of the thing you are suggesting. For example, if you propose, "The problem in this community is that it has no hospital."

This only leads to a research problem where:

- The need is for a hospital

- The objective is to create a hospital

- The method is to plan for building a hospital, and

- The evaluation is to measure if there is a hospital or not.

This is an example of a research problem that fails the "so what?" test because it does not reveal the relevance of why you are investigating the problem of having no hospital in the community [e.g., there's a hospital in the community ten miles away] and because the research problem does not elucidate the significance of why one should study the fact that no hospital exists in the community [e.g., that hospital in the community ten miles away has no emergency room].

Choosing and Refining Topics . Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Ellis, Timothy J. and Yair Levy Nova Framework of Problem-Based Research: A Guide for Novice Researchers on the Development of a Research-Worthy Problem. Informing Science: the International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 11 (2008); How to Write a Research Question . The Writing Center. George Mason University; Invention: Developing a Thesis Statement . The Reading/Writing Center. Hunter College; Problem Statements PowerPoint Presentation . The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Procter, Margaret. Using Thesis Statements . University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Trochim, William M.K. Problem Formulation . Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Thesis and Purpose Statements . The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Thesis Statements . The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements . The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University.

- << Previous: Background Information

- Next: Theoretical Framework >>

- Last Updated: Jul 18, 2023 11:58 AM

- URL: https://library.sacredheart.edu/c.php?g=29803

- QuickSearch

- Library Catalog

- Databases A-Z

- Publication Finder

- Course Reserves

- Citation Linker

- Digital Commons

- Our Website

Research Support

- Ask a Librarian

- Appointments

- Interlibrary Loan (ILL)

- Research Guides

- Databases by Subject

- Citation Help

Using the Library

- Reserve a Group Study Room

- Renew Books

- Honors Study Rooms

- Off-Campus Access

- Library Policies

- Library Technology

User Information

- Grad Students

- Online Students

- COVID-19 Updates

- Staff Directory

- News & Announcements

- Library Newsletter

My Accounts

- Interlibrary Loan

- Staff Site Login

FIND US ON

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Problem – Examples, Types and Guide

Research Problem – Examples, Types and Guide

Table of Contents

Research Problem

Definition:

Research problem is a specific and well-defined issue or question that a researcher seeks to investigate through research. It is the starting point of any research project, as it sets the direction, scope, and purpose of the study.

Types of Research Problems

Types of Research Problems are as follows:

Descriptive problems

These problems involve describing or documenting a particular phenomenon, event, or situation. For example, a researcher might investigate the demographics of a particular population, such as their age, gender, income, and education.

Exploratory problems

These problems are designed to explore a particular topic or issue in depth, often with the goal of generating new ideas or hypotheses. For example, a researcher might explore the factors that contribute to job satisfaction among employees in a particular industry.

Explanatory Problems

These problems seek to explain why a particular phenomenon or event occurs, and they typically involve testing hypotheses or theories. For example, a researcher might investigate the relationship between exercise and mental health, with the goal of determining whether exercise has a causal effect on mental health.

Predictive Problems

These problems involve making predictions or forecasts about future events or trends. For example, a researcher might investigate the factors that predict future success in a particular field or industry.

Evaluative Problems

These problems involve assessing the effectiveness of a particular intervention, program, or policy. For example, a researcher might evaluate the impact of a new teaching method on student learning outcomes.

How to Define a Research Problem

Defining a research problem involves identifying a specific question or issue that a researcher seeks to address through a research study. Here are the steps to follow when defining a research problem:

- Identify a broad research topic : Start by identifying a broad topic that you are interested in researching. This could be based on your personal interests, observations, or gaps in the existing literature.

- Conduct a literature review : Once you have identified a broad topic, conduct a thorough literature review to identify the current state of knowledge in the field. This will help you identify gaps or inconsistencies in the existing research that can be addressed through your study.

- Refine the research question: Based on the gaps or inconsistencies identified in the literature review, refine your research question to a specific, clear, and well-defined problem statement. Your research question should be feasible, relevant, and important to the field of study.

- Develop a hypothesis: Based on the research question, develop a hypothesis that states the expected relationship between variables.

- Define the scope and limitations: Clearly define the scope and limitations of your research problem. This will help you focus your study and ensure that your research objectives are achievable.

- Get feedback: Get feedback from your advisor or colleagues to ensure that your research problem is clear, feasible, and relevant to the field of study.

Components of a Research Problem

The components of a research problem typically include the following:

- Topic : The general subject or area of interest that the research will explore.

- Research Question : A clear and specific question that the research seeks to answer or investigate.

- Objective : A statement that describes the purpose of the research, what it aims to achieve, and the expected outcomes.

- Hypothesis : An educated guess or prediction about the relationship between variables, which is tested during the research.

- Variables : The factors or elements that are being studied, measured, or manipulated in the research.

- Methodology : The overall approach and methods that will be used to conduct the research.

- Scope and Limitations : A description of the boundaries and parameters of the research, including what will be included and excluded, and any potential constraints or limitations.

- Significance: A statement that explains the potential value or impact of the research, its contribution to the field of study, and how it will add to the existing knowledge.

Research Problem Examples

Following are some Research Problem Examples:

Research Problem Examples in Psychology are as follows:

- Exploring the impact of social media on adolescent mental health.

- Investigating the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy for treating anxiety disorders.

- Studying the impact of prenatal stress on child development outcomes.

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to addiction and relapse in substance abuse treatment.

- Examining the impact of personality traits on romantic relationships.

Research Problem Examples in Sociology are as follows:

- Investigating the relationship between social support and mental health outcomes in marginalized communities.

- Studying the impact of globalization on labor markets and employment opportunities.

- Analyzing the causes and consequences of gentrification in urban neighborhoods.

- Investigating the impact of family structure on social mobility and economic outcomes.

- Examining the effects of social capital on community development and resilience.

Research Problem Examples in Economics are as follows:

- Studying the effects of trade policies on economic growth and development.

- Analyzing the impact of automation and artificial intelligence on labor markets and employment opportunities.

- Investigating the factors that contribute to economic inequality and poverty.

- Examining the impact of fiscal and monetary policies on inflation and economic stability.

- Studying the relationship between education and economic outcomes, such as income and employment.

Political Science

Research Problem Examples in Political Science are as follows:

- Analyzing the causes and consequences of political polarization and partisan behavior.

- Investigating the impact of social movements on political change and policymaking.

- Studying the role of media and communication in shaping public opinion and political discourse.

- Examining the effectiveness of electoral systems in promoting democratic governance and representation.

- Investigating the impact of international organizations and agreements on global governance and security.

Environmental Science

Research Problem Examples in Environmental Science are as follows:

- Studying the impact of air pollution on human health and well-being.

- Investigating the effects of deforestation on climate change and biodiversity loss.

- Analyzing the impact of ocean acidification on marine ecosystems and food webs.

- Studying the relationship between urban development and ecological resilience.

- Examining the effectiveness of environmental policies and regulations in promoting sustainability and conservation.

Research Problem Examples in Education are as follows:

- Investigating the impact of teacher training and professional development on student learning outcomes.

- Studying the effectiveness of technology-enhanced learning in promoting student engagement and achievement.

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to achievement gaps and educational inequality.

- Examining the impact of parental involvement on student motivation and achievement.

- Studying the effectiveness of alternative educational models, such as homeschooling and online learning.

Research Problem Examples in History are as follows:

- Analyzing the social and economic factors that contributed to the rise and fall of ancient civilizations.

- Investigating the impact of colonialism on indigenous societies and cultures.

- Studying the role of religion in shaping political and social movements throughout history.

- Analyzing the impact of the Industrial Revolution on economic and social structures.

- Examining the causes and consequences of global conflicts, such as World War I and II.

Research Problem Examples in Business are as follows:

- Studying the impact of corporate social responsibility on brand reputation and consumer behavior.

- Investigating the effectiveness of leadership development programs in improving organizational performance and employee satisfaction.

- Analyzing the factors that contribute to successful entrepreneurship and small business development.

- Examining the impact of mergers and acquisitions on market competition and consumer welfare.

- Studying the effectiveness of marketing strategies and advertising campaigns in promoting brand awareness and sales.

Research Problem Example for Students

An Example of a Research Problem for Students could be:

“How does social media usage affect the academic performance of high school students?”

This research problem is specific, measurable, and relevant. It is specific because it focuses on a particular area of interest, which is the impact of social media on academic performance. It is measurable because the researcher can collect data on social media usage and academic performance to evaluate the relationship between the two variables. It is relevant because it addresses a current and important issue that affects high school students.

To conduct research on this problem, the researcher could use various methods, such as surveys, interviews, and statistical analysis of academic records. The results of the study could provide insights into the relationship between social media usage and academic performance, which could help educators and parents develop effective strategies for managing social media use among students.

Another example of a research problem for students:

“Does participation in extracurricular activities impact the academic performance of middle school students?”

This research problem is also specific, measurable, and relevant. It is specific because it focuses on a particular type of activity, extracurricular activities, and its impact on academic performance. It is measurable because the researcher can collect data on students’ participation in extracurricular activities and their academic performance to evaluate the relationship between the two variables. It is relevant because extracurricular activities are an essential part of the middle school experience, and their impact on academic performance is a topic of interest to educators and parents.

To conduct research on this problem, the researcher could use surveys, interviews, and academic records analysis. The results of the study could provide insights into the relationship between extracurricular activities and academic performance, which could help educators and parents make informed decisions about the types of activities that are most beneficial for middle school students.

Applications of Research Problem

Applications of Research Problem are as follows:

- Academic research: Research problems are used to guide academic research in various fields, including social sciences, natural sciences, humanities, and engineering. Researchers use research problems to identify gaps in knowledge, address theoretical or practical problems, and explore new areas of study.

- Business research : Research problems are used to guide business research, including market research, consumer behavior research, and organizational research. Researchers use research problems to identify business challenges, explore opportunities, and develop strategies for business growth and success.

- Healthcare research : Research problems are used to guide healthcare research, including medical research, clinical research, and health services research. Researchers use research problems to identify healthcare challenges, develop new treatments and interventions, and improve healthcare delivery and outcomes.

- Public policy research : Research problems are used to guide public policy research, including policy analysis, program evaluation, and policy development. Researchers use research problems to identify social issues, assess the effectiveness of existing policies and programs, and develop new policies and programs to address societal challenges.

- Environmental research : Research problems are used to guide environmental research, including environmental science, ecology, and environmental management. Researchers use research problems to identify environmental challenges, assess the impact of human activities on the environment, and develop sustainable solutions to protect the environment.

Purpose of Research Problems

The purpose of research problems is to identify an area of study that requires further investigation and to formulate a clear, concise and specific research question. A research problem defines the specific issue or problem that needs to be addressed and serves as the foundation for the research project.

Identifying a research problem is important because it helps to establish the direction of the research and sets the stage for the research design, methods, and analysis. It also ensures that the research is relevant and contributes to the existing body of knowledge in the field.

A well-formulated research problem should:

- Clearly define the specific issue or problem that needs to be investigated

- Be specific and narrow enough to be manageable in terms of time, resources, and scope

- Be relevant to the field of study and contribute to the existing body of knowledge

- Be feasible and realistic in terms of available data, resources, and research methods

- Be interesting and intellectually stimulating for the researcher and potential readers or audiences.

Characteristics of Research Problem

The characteristics of a research problem refer to the specific features that a problem must possess to qualify as a suitable research topic. Some of the key characteristics of a research problem are:

- Clarity : A research problem should be clearly defined and stated in a way that it is easily understood by the researcher and other readers. The problem should be specific, unambiguous, and easy to comprehend.

- Relevance : A research problem should be relevant to the field of study, and it should contribute to the existing body of knowledge. The problem should address a gap in knowledge, a theoretical or practical problem, or a real-world issue that requires further investigation.

- Feasibility : A research problem should be feasible in terms of the availability of data, resources, and research methods. It should be realistic and practical to conduct the study within the available time, budget, and resources.

- Novelty : A research problem should be novel or original in some way. It should represent a new or innovative perspective on an existing problem, or it should explore a new area of study or apply an existing theory to a new context.

- Importance : A research problem should be important or significant in terms of its potential impact on the field or society. It should have the potential to produce new knowledge, advance existing theories, or address a pressing societal issue.

- Manageability : A research problem should be manageable in terms of its scope and complexity. It should be specific enough to be investigated within the available time and resources, and it should be broad enough to provide meaningful results.

Advantages of Research Problem

The advantages of a well-defined research problem are as follows:

- Focus : A research problem provides a clear and focused direction for the research study. It ensures that the study stays on track and does not deviate from the research question.

- Clarity : A research problem provides clarity and specificity to the research question. It ensures that the research is not too broad or too narrow and that the research objectives are clearly defined.

- Relevance : A research problem ensures that the research study is relevant to the field of study and contributes to the existing body of knowledge. It addresses gaps in knowledge, theoretical or practical problems, or real-world issues that require further investigation.

- Feasibility : A research problem ensures that the research study is feasible in terms of the availability of data, resources, and research methods. It ensures that the research is realistic and practical to conduct within the available time, budget, and resources.

- Novelty : A research problem ensures that the research study is original and innovative. It represents a new or unique perspective on an existing problem, explores a new area of study, or applies an existing theory to a new context.

- Importance : A research problem ensures that the research study is important and significant in terms of its potential impact on the field or society. It has the potential to produce new knowledge, advance existing theories, or address a pressing societal issue.

- Rigor : A research problem ensures that the research study is rigorous and follows established research methods and practices. It ensures that the research is conducted in a systematic, objective, and unbiased manner.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Future Research – Thesis Guide

Research Methods – Types, Examples and Guide

Chapter Summary & Overview – Writing Guide...

Research Approach – Types Methods and Examples

Research Report – Example, Writing Guide and...

Research Contribution – Thesis Guide

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples

Writing Strong Research Questions | Criteria & Examples

Published on October 26, 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 21, 2023.

A research question pinpoints exactly what you want to find out in your work. A good research question is essential to guide your research paper , dissertation , or thesis .

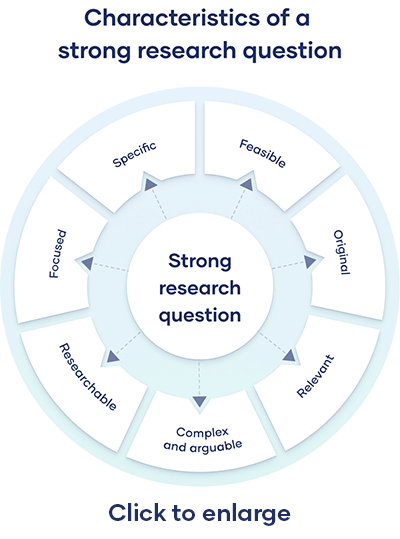

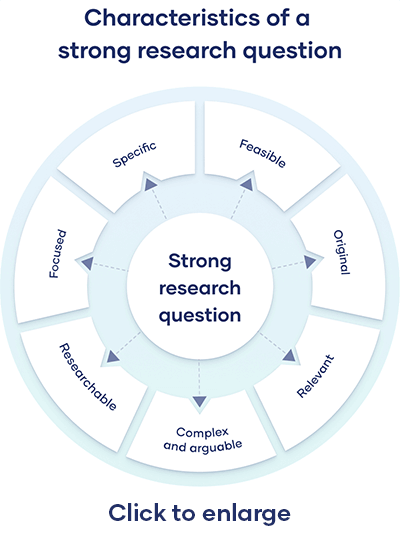

All research questions should be:

- Focused on a single problem or issue

- Researchable using primary and/or secondary sources

- Feasible to answer within the timeframe and practical constraints

- Specific enough to answer thoroughly

- Complex enough to develop the answer over the space of a paper or thesis

- Relevant to your field of study and/or society more broadly

Table of contents

How to write a research question, what makes a strong research question, using sub-questions to strengthen your main research question, research questions quiz, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research questions.

You can follow these steps to develop a strong research question:

- Choose your topic

- Do some preliminary reading about the current state of the field

- Narrow your focus to a specific niche

- Identify the research problem that you will address

The way you frame your question depends on what your research aims to achieve. The table below shows some examples of how you might formulate questions for different purposes.

| Research question formulations | |

|---|---|

| Describing and exploring | |

| Explaining and testing | |

| Evaluating and acting | is X |

Using your research problem to develop your research question

| Example research problem | Example research question(s) |

|---|---|

| Teachers at the school do not have the skills to recognize or properly guide gifted children in the classroom. | What practical techniques can teachers use to better identify and guide gifted children? |

| Young people increasingly engage in the “gig economy,” rather than traditional full-time employment. However, it is unclear why they choose to do so. | What are the main factors influencing young people’s decisions to engage in the gig economy? |

Note that while most research questions can be answered with various types of research , the way you frame your question should help determine your choices.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Research questions anchor your whole project, so it’s important to spend some time refining them. The criteria below can help you evaluate the strength of your research question.

Focused and researchable

| Criteria | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Focused on a single topic | Your central research question should work together with your research problem to keep your work focused. If you have multiple questions, they should all clearly tie back to your central aim. |

| Answerable using | Your question must be answerable using and/or , or by reading scholarly sources on the to develop your argument. If such data is impossible to access, you likely need to rethink your question. |

| Not based on value judgements | Avoid subjective words like , , and . These do not give clear criteria for answering the question. |

Feasible and specific

| Criteria | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Answerable within practical constraints | Make sure you have enough time and resources to do all research required to answer your question. If it seems you will not be able to gain access to the data you need, consider narrowing down your question to be more specific. |

| Uses specific, well-defined concepts | All the terms you use in the research question should have clear meanings. Avoid vague language, jargon, and too-broad ideas. |

| Does not demand a conclusive solution, policy, or course of action | Research is about informing, not instructing. Even if your project is focused on a practical problem, it should aim to improve understanding rather than demand a ready-made solution. If ready-made solutions are necessary, consider conducting instead. Action research is a research method that aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as it is solved. In other words, as its name suggests, action research conducts research and takes action at the same time. |

Complex and arguable

| Criteria | Explanation |

|---|---|