Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

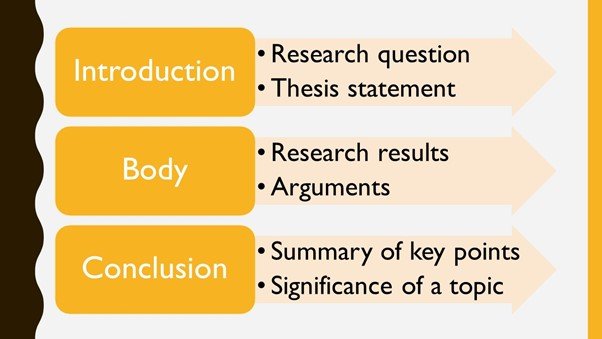

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- PLoS Comput Biol

- v.9(7); 2013 Jul

Ten Simple Rules for Writing a Literature Review

Marco pautasso.

1 Centre for Functional and Evolutionary Ecology (CEFE), CNRS, Montpellier, France

2 Centre for Biodiversity Synthesis and Analysis (CESAB), FRB, Aix-en-Provence, France

Literature reviews are in great demand in most scientific fields. Their need stems from the ever-increasing output of scientific publications [1] . For example, compared to 1991, in 2008 three, eight, and forty times more papers were indexed in Web of Science on malaria, obesity, and biodiversity, respectively [2] . Given such mountains of papers, scientists cannot be expected to examine in detail every single new paper relevant to their interests [3] . Thus, it is both advantageous and necessary to rely on regular summaries of the recent literature. Although recognition for scientists mainly comes from primary research, timely literature reviews can lead to new synthetic insights and are often widely read [4] . For such summaries to be useful, however, they need to be compiled in a professional way [5] .

When starting from scratch, reviewing the literature can require a titanic amount of work. That is why researchers who have spent their career working on a certain research issue are in a perfect position to review that literature. Some graduate schools are now offering courses in reviewing the literature, given that most research students start their project by producing an overview of what has already been done on their research issue [6] . However, it is likely that most scientists have not thought in detail about how to approach and carry out a literature review.

Reviewing the literature requires the ability to juggle multiple tasks, from finding and evaluating relevant material to synthesising information from various sources, from critical thinking to paraphrasing, evaluating, and citation skills [7] . In this contribution, I share ten simple rules I learned working on about 25 literature reviews as a PhD and postdoctoral student. Ideas and insights also come from discussions with coauthors and colleagues, as well as feedback from reviewers and editors.

Rule 1: Define a Topic and Audience

How to choose which topic to review? There are so many issues in contemporary science that you could spend a lifetime of attending conferences and reading the literature just pondering what to review. On the one hand, if you take several years to choose, several other people may have had the same idea in the meantime. On the other hand, only a well-considered topic is likely to lead to a brilliant literature review [8] . The topic must at least be:

- interesting to you (ideally, you should have come across a series of recent papers related to your line of work that call for a critical summary),

- an important aspect of the field (so that many readers will be interested in the review and there will be enough material to write it), and

- a well-defined issue (otherwise you could potentially include thousands of publications, which would make the review unhelpful).

Ideas for potential reviews may come from papers providing lists of key research questions to be answered [9] , but also from serendipitous moments during desultory reading and discussions. In addition to choosing your topic, you should also select a target audience. In many cases, the topic (e.g., web services in computational biology) will automatically define an audience (e.g., computational biologists), but that same topic may also be of interest to neighbouring fields (e.g., computer science, biology, etc.).

Rule 2: Search and Re-search the Literature

After having chosen your topic and audience, start by checking the literature and downloading relevant papers. Five pieces of advice here:

- keep track of the search items you use (so that your search can be replicated [10] ),

- keep a list of papers whose pdfs you cannot access immediately (so as to retrieve them later with alternative strategies),

- use a paper management system (e.g., Mendeley, Papers, Qiqqa, Sente),

- define early in the process some criteria for exclusion of irrelevant papers (these criteria can then be described in the review to help define its scope), and

- do not just look for research papers in the area you wish to review, but also seek previous reviews.

The chances are high that someone will already have published a literature review ( Figure 1 ), if not exactly on the issue you are planning to tackle, at least on a related topic. If there are already a few or several reviews of the literature on your issue, my advice is not to give up, but to carry on with your own literature review,

The bottom-right situation (many literature reviews but few research papers) is not just a theoretical situation; it applies, for example, to the study of the impacts of climate change on plant diseases, where there appear to be more literature reviews than research studies [33] .

- discussing in your review the approaches, limitations, and conclusions of past reviews,

- trying to find a new angle that has not been covered adequately in the previous reviews, and

- incorporating new material that has inevitably accumulated since their appearance.

When searching the literature for pertinent papers and reviews, the usual rules apply:

- be thorough,

- use different keywords and database sources (e.g., DBLP, Google Scholar, ISI Proceedings, JSTOR Search, Medline, Scopus, Web of Science), and

- look at who has cited past relevant papers and book chapters.

Rule 3: Take Notes While Reading

If you read the papers first, and only afterwards start writing the review, you will need a very good memory to remember who wrote what, and what your impressions and associations were while reading each single paper. My advice is, while reading, to start writing down interesting pieces of information, insights about how to organize the review, and thoughts on what to write. This way, by the time you have read the literature you selected, you will already have a rough draft of the review.

Of course, this draft will still need much rewriting, restructuring, and rethinking to obtain a text with a coherent argument [11] , but you will have avoided the danger posed by staring at a blank document. Be careful when taking notes to use quotation marks if you are provisionally copying verbatim from the literature. It is advisable then to reformulate such quotes with your own words in the final draft. It is important to be careful in noting the references already at this stage, so as to avoid misattributions. Using referencing software from the very beginning of your endeavour will save you time.

Rule 4: Choose the Type of Review You Wish to Write

After having taken notes while reading the literature, you will have a rough idea of the amount of material available for the review. This is probably a good time to decide whether to go for a mini- or a full review. Some journals are now favouring the publication of rather short reviews focusing on the last few years, with a limit on the number of words and citations. A mini-review is not necessarily a minor review: it may well attract more attention from busy readers, although it will inevitably simplify some issues and leave out some relevant material due to space limitations. A full review will have the advantage of more freedom to cover in detail the complexities of a particular scientific development, but may then be left in the pile of the very important papers “to be read” by readers with little time to spare for major monographs.

There is probably a continuum between mini- and full reviews. The same point applies to the dichotomy of descriptive vs. integrative reviews. While descriptive reviews focus on the methodology, findings, and interpretation of each reviewed study, integrative reviews attempt to find common ideas and concepts from the reviewed material [12] . A similar distinction exists between narrative and systematic reviews: while narrative reviews are qualitative, systematic reviews attempt to test a hypothesis based on the published evidence, which is gathered using a predefined protocol to reduce bias [13] , [14] . When systematic reviews analyse quantitative results in a quantitative way, they become meta-analyses. The choice between different review types will have to be made on a case-by-case basis, depending not just on the nature of the material found and the preferences of the target journal(s), but also on the time available to write the review and the number of coauthors [15] .

Rule 5: Keep the Review Focused, but Make It of Broad Interest

Whether your plan is to write a mini- or a full review, it is good advice to keep it focused 16 , 17 . Including material just for the sake of it can easily lead to reviews that are trying to do too many things at once. The need to keep a review focused can be problematic for interdisciplinary reviews, where the aim is to bridge the gap between fields [18] . If you are writing a review on, for example, how epidemiological approaches are used in modelling the spread of ideas, you may be inclined to include material from both parent fields, epidemiology and the study of cultural diffusion. This may be necessary to some extent, but in this case a focused review would only deal in detail with those studies at the interface between epidemiology and the spread of ideas.

While focus is an important feature of a successful review, this requirement has to be balanced with the need to make the review relevant to a broad audience. This square may be circled by discussing the wider implications of the reviewed topic for other disciplines.

Rule 6: Be Critical and Consistent

Reviewing the literature is not stamp collecting. A good review does not just summarize the literature, but discusses it critically, identifies methodological problems, and points out research gaps [19] . After having read a review of the literature, a reader should have a rough idea of:

- the major achievements in the reviewed field,

- the main areas of debate, and

- the outstanding research questions.

It is challenging to achieve a successful review on all these fronts. A solution can be to involve a set of complementary coauthors: some people are excellent at mapping what has been achieved, some others are very good at identifying dark clouds on the horizon, and some have instead a knack at predicting where solutions are going to come from. If your journal club has exactly this sort of team, then you should definitely write a review of the literature! In addition to critical thinking, a literature review needs consistency, for example in the choice of passive vs. active voice and present vs. past tense.

Rule 7: Find a Logical Structure

Like a well-baked cake, a good review has a number of telling features: it is worth the reader's time, timely, systematic, well written, focused, and critical. It also needs a good structure. With reviews, the usual subdivision of research papers into introduction, methods, results, and discussion does not work or is rarely used. However, a general introduction of the context and, toward the end, a recapitulation of the main points covered and take-home messages make sense also in the case of reviews. For systematic reviews, there is a trend towards including information about how the literature was searched (database, keywords, time limits) [20] .

How can you organize the flow of the main body of the review so that the reader will be drawn into and guided through it? It is generally helpful to draw a conceptual scheme of the review, e.g., with mind-mapping techniques. Such diagrams can help recognize a logical way to order and link the various sections of a review [21] . This is the case not just at the writing stage, but also for readers if the diagram is included in the review as a figure. A careful selection of diagrams and figures relevant to the reviewed topic can be very helpful to structure the text too [22] .

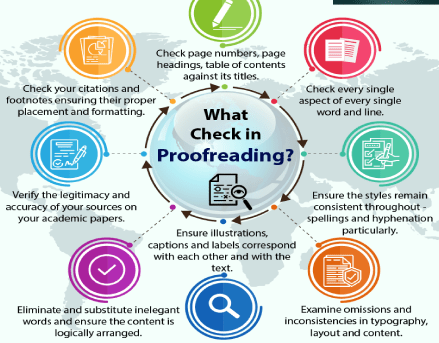

Rule 8: Make Use of Feedback

Reviews of the literature are normally peer-reviewed in the same way as research papers, and rightly so [23] . As a rule, incorporating feedback from reviewers greatly helps improve a review draft. Having read the review with a fresh mind, reviewers may spot inaccuracies, inconsistencies, and ambiguities that had not been noticed by the writers due to rereading the typescript too many times. It is however advisable to reread the draft one more time before submission, as a last-minute correction of typos, leaps, and muddled sentences may enable the reviewers to focus on providing advice on the content rather than the form.

Feedback is vital to writing a good review, and should be sought from a variety of colleagues, so as to obtain a diversity of views on the draft. This may lead in some cases to conflicting views on the merits of the paper, and on how to improve it, but such a situation is better than the absence of feedback. A diversity of feedback perspectives on a literature review can help identify where the consensus view stands in the landscape of the current scientific understanding of an issue [24] .

Rule 9: Include Your Own Relevant Research, but Be Objective

In many cases, reviewers of the literature will have published studies relevant to the review they are writing. This could create a conflict of interest: how can reviewers report objectively on their own work [25] ? Some scientists may be overly enthusiastic about what they have published, and thus risk giving too much importance to their own findings in the review. However, bias could also occur in the other direction: some scientists may be unduly dismissive of their own achievements, so that they will tend to downplay their contribution (if any) to a field when reviewing it.

In general, a review of the literature should neither be a public relations brochure nor an exercise in competitive self-denial. If a reviewer is up to the job of producing a well-organized and methodical review, which flows well and provides a service to the readership, then it should be possible to be objective in reviewing one's own relevant findings. In reviews written by multiple authors, this may be achieved by assigning the review of the results of a coauthor to different coauthors.

Rule 10: Be Up-to-Date, but Do Not Forget Older Studies

Given the progressive acceleration in the publication of scientific papers, today's reviews of the literature need awareness not just of the overall direction and achievements of a field of inquiry, but also of the latest studies, so as not to become out-of-date before they have been published. Ideally, a literature review should not identify as a major research gap an issue that has just been addressed in a series of papers in press (the same applies, of course, to older, overlooked studies (“sleeping beauties” [26] )). This implies that literature reviewers would do well to keep an eye on electronic lists of papers in press, given that it can take months before these appear in scientific databases. Some reviews declare that they have scanned the literature up to a certain point in time, but given that peer review can be a rather lengthy process, a full search for newly appeared literature at the revision stage may be worthwhile. Assessing the contribution of papers that have just appeared is particularly challenging, because there is little perspective with which to gauge their significance and impact on further research and society.

Inevitably, new papers on the reviewed topic (including independently written literature reviews) will appear from all quarters after the review has been published, so that there may soon be the need for an updated review. But this is the nature of science [27] – [32] . I wish everybody good luck with writing a review of the literature.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to M. Barbosa, K. Dehnen-Schmutz, T. Döring, D. Fontaneto, M. Garbelotto, O. Holdenrieder, M. Jeger, D. Lonsdale, A. MacLeod, P. Mills, M. Moslonka-Lefebvre, G. Stancanelli, P. Weisberg, and X. Xu for insights and discussions, and to P. Bourne, T. Matoni, and D. Smith for helpful comments on a previous draft.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the French Foundation for Research on Biodiversity (FRB) through its Centre for Synthesis and Analysis of Biodiversity data (CESAB), as part of the NETSEED research project. The funders had no role in the preparation of the manuscript.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Literature Reviews

- Getting started

What is a literature review?

Why conduct a literature review, stages of a literature review, lit reviews: an overview (video), check out these books.

- Types of reviews

- 1. Define your research question

- 2. Plan your search

- 3. Search the literature

- 4. Organize your results

- 5. Synthesize your findings

- 6. Write the review

- Artificial intelligence (AI) tools

- Thompson Writing Studio This link opens in a new window

- Need to write a systematic review? This link opens in a new window

Guide Owner

Contact a Librarian

Ask a Librarian

Definition: A literature review is a systematic examination and synthesis of existing scholarly research on a specific topic or subject.

Purpose: It serves to provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of knowledge within a particular field.

Analysis: Involves critically evaluating and summarizing key findings, methodologies, and debates found in academic literature.

Identifying Gaps: Aims to pinpoint areas where there is a lack of research or unresolved questions, highlighting opportunities for further investigation.

Contextualization: Enables researchers to understand how their work fits into the broader academic conversation and contributes to the existing body of knowledge.

tl;dr A literature review critically examines and synthesizes existing scholarly research and publications on a specific topic to provide a comprehensive understanding of the current state of knowledge in the field.

What is a literature review NOT?

❌ An annotated bibliography

❌ Original research

❌ A summary

❌ Something to be conducted at the end of your research

❌ An opinion piece

❌ A chronological compilation of studies

The reason for conducting a literature review is to:

| What has been written about your topic? What is the evidence for your topic? What methods, key concepts, and theories relate to your topic? Are there current gaps in knowledge or new questions to be asked? | |

| Bring your reader up to date Further your reader's understanding of the topic | |

| Provide evidence of... - your knowledge on the topic's theory - your understanding of the research process - your ability to critically evaluate and analyze information - that you're up to date on the literature |

Literature Reviews: An Overview for Graduate Students

While this 9-minute video from NCSU is geared toward graduate students, it is useful for anyone conducting a literature review.

Writing the literature review: A practical guide

Available 3rd floor of Perkins

Writing literature reviews: A guide for students of the social and behavioral sciences

Available online!

So, you have to write a literature review: A guided workbook for engineers

Telling a research story: Writing a literature review

The literature review: Six steps to success

Systematic approaches to a successful literature review

Request from Duke Medical Center Library

Doing a systematic review: A student's guide

- Next: Types of reviews >>

- Last Updated: Aug 29, 2024 11:40 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.duke.edu/litreviews

Services for...

- Faculty & Instructors

- Graduate Students

- Undergraduate Students

- International Students

- Patrons with Disabilities

- Harmful Language Statement

- Re-use & Attribution / Privacy

- Support the Libraries

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jun 20, 2024 9:08 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

PSYC 210: Foundations of Psychology

- Tips for Searching for Articles

What is a literature review?

Conducting a literature review, organizing a literature review, writing a literature review, helpful book.

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Google Scholar

A literature review is a compilation of the works published in a particular field of study or line of research, usually over a specific period of time, in the form of an in-depth, critical bibliographic essay or annotated list in which attention is drawn to the most significant works.

- Summarizes and analyzes previous research relevant to a topic

- Includes scholarly books and articles published in academic journals

- Can be an specific scholarly paper or a section in a research paper

The objective of a Literature Review is to find previous published scholarly works relevant to an specific topic

- Help gather ideas or information

- Keep up to date in current trends and findings

- Help develop new questions

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area

- Helps focus your own research questions or problems

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas

- Suggests unexplored ideas or populations

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic

- Tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias

- Identifies critical gaps, points of disagreement, or potentially flawed methodology or theoretical approaches

Source: "What is a Literature Review?", Old Dominion University, https://guides.lib.odu.edu/c.php?g=966167&p=6980532

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by a central research question. It represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted, and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow.

- Write down terms that are related to your question for they will be useful for searches later.

2. Decide on the scope of your review.

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment.

- Consider these things when planning your time for research.

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

- By Research Guide

4. Conduct your searches and find the literature.

- Review the abstracts carefully - this will save you time!

- Many databases will have a search history tab for you to return to for later.

- Use bibliographies and references of research studies to locate others.

- Use citation management software such as Zotero to keep track of your research citations.

5. Review the literature.

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question you are reviewing? What are the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze the literature review, samples and variables used, results, and conclusions. Does the research seem complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicted studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Are they experts or novices? Has the study been cited?

Source: "Literature Review", University of West Florida, https://libguides.uwf.edu/c.php?g=215113&p=5139469

A literature review is not a summary of the sources but a synthesis of the sources. It is made up of the topics the sources are discussing. Each section of the review is focused on a topic, and the relevant sources are discussed within the context of that topic.

1. Select the most relevant material from the sources

- Could be material that answers the question directly

- Extract as a direct quote or paraphrase

2. Arrange that material so you can focus on it apart from the source text itself

- You are now working with fewer words/passages

- Material is all in one place

3. Group similar points, themes, or topics together and label them

- The labels describe the points, themes, or topics that are the backbone of your paper’s structure

4. Order those points, themes, or topics as you will discuss them in the paper, and turn the labels into actual assertions

- A sentence that makes a point that is directly related to your research question or thesis

This is now the outline for your literature review.

Source: "Organizing a Review of the Literature – The Basics", George Mason University Writing Center, https://writingcenter.gmu.edu/writing-resources/research-based-writing/organizing-literature-reviews-the-basics

- Literature Review Matrix Here is a template on how people tend to organize their thoughts. The matrix template is a good way to write out the key parts of each article and take notes. Downloads as an XLSX file.

The most common way that literature reviews are organized is by theme or author. Find a general pattern of structure for the review. When organizing the review, consider the following:

- the methodology

- the quality of the findings or conclusions

- major strengths and weaknesses

- any other important information

Writing Tips:

- Be selective - Select only the most important points in each source to highlight in the review. It should directly relate to the review's focus.

- Use quotes sparingly.

- Keep your own voice - Your voice (the writer's) should remain front and center. .

- Aim for one key figure/table per section to illustrate complex content, summarize a large body of relevant data, or describe the order of a process

- Legend below image/figure and above table and always refer to them in text

Source: "Composing your Literature Review", Florida A&M University, https://library.famu.edu/c.php?g=577356&p=3982811

- << Previous: Tips for Searching for Articles

- Next: Citing Your Sources >>

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2024 3:43 PM

- URL: https://infoguides.pepperdine.edu/PSYC210

Explore. Discover. Create.

Copyright © 2022 Pepperdine University

Workshop: Literature Reviews- What you need to know

- How to write a literature review

Useful Titles for All of your Boxes

The Seven Steps to Producing a Literature Review:

1. Identify your question

2. Review discipline style

3. Search the literature

4. Manage your references

5. Critically analyze and evaluate

6. Synthisize

7. Write the review

- University of North Carolina Writing Center "How To" UNC Chapel Hill Writing Center "How To" on writing a literature review.

- Purdue Owl Purdue Owl help on writing a literature review

Feedback and Additional Information

- Library Workshop Evaluation Brief survey for workshop participants. Your feedback is greatly appreciated.

- TTU Library Workshops Additional information about TTU Library Workshops. All workshops are taught by Personal Librarians in Instruction Lab 150 unless otherwise noted.

- Last Updated: Aug 27, 2024 8:06 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.ttu.edu/litreview

Literature Review - what is a Literature Review, why it is important and how it is done

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Literature Reviews and Sources

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

Literature Reviews: Useful Sites

Writing tutorials & other resources.

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

- Useful Resources

The majority of these sites focus on literature reviews in the social sciences unless otherwise noted. For systematic literature reviews, we recommend you to contact directly your subject librarian for help.

- How to Write a Literature Review Nice and concise handout on how to write a literature review

- Six Steps to Writing a Literature Review This blog, written by Tanya Golash-Boza, an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of California at Merced, a successful PhD, offers a very nice and simple advice on how to write a literature review from the point of view of an experience professional. Tanya's current research is on racial identities and immigration policies. She is currently writing a book on deportees.

- Literature Review and Synthesis (University Writing Center, Indiana University) Excellent handout to teach you how to synthesize (make connections between) multiple sources in your literature review

- How to Write a Historiography (Literature Review for History) This is an excellent site to learn how to write this particular literature review in History.

Literature Reviews: An Overview for Graduate Students. (NCSU Libraries) What is a literature review? What purpose does it serve in research? What should you expect when writing one?

A selection of sites that offer tutorials and handouts to learn how to write literature reviews and how to use specific writing skills such as paraphrasing and synthesis.

- Literature Review Online Tutorial (North Carolina State University Libraries)

- Literature Review Tutorial (CQ University-Australia)

- Paraphrase: Write it in Your Own Words (OWL Purdue Writing Lab)

- Acknowledging, Paraphrasing and Quoting Sources (UW-Madison's Writing Center) This is an open PDF document with the whole guide on Acknowledging, Paraphrasing and Quoting Sources.

- Synthesize - The Literature Review: A Research Journey Nice explanation by Harvard's Graduate School of Education on what is synthesis. Also, check out the rest of the guide for definitions and videos of faculty and students about the literature review process.

- Introduction to Syntheses Excellent presentation of what is syntheses, different types of it, etc...

- << Previous: Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Next: Citation Resources >>

- Last Updated: Jul 3, 2024 10:56 AM

- URL: https://lit.libguides.com/Literature-Review

The Library, Technological University of the Shannon: Midwest

17 strong academic phrases to write your literature review (+ real examples)

A well-written academic literature review not only builds upon existing knowledge and publications but also involves critical reflection, comparison, contrast, and identifying research gaps. The following 17 strong academic key phrases can assist you in writing a critical and reflective literature review.

Academic key phrases to present existing knowledge in a literature review

The topic has received significant interest within the wider literature..

Example: “ The topic of big data and its integration with AI has received significant interest within the wider literature .” ( Dwivedi et al. 2021, p. 4 )

The topic gained considerable attention in the academic literature in…

Studies have identified….

Example: “ Studies have identified the complexities of implementing AI based systems within government and the public sector .” ( Dwivedi et al. 2021, p. 6 )

Researchers have discussed…

Recent work demonstrated that….

Example: “Recent work demonstrated that dune grasses with similar morphological traits can build contrasting landscapes due to differences in their spatial shoot organization.” ( Van de Ven, 2022 et al., p. 1339 )

Existing research frequently attributes…

Prior research has hypothesized that…, prior studies have found that….

Example: “ Prior studies have found that court-referred individuals are more likely to complete relationship violence intervention programs (RVIP) than self-referred individuals. ” ( Evans et al. 2022, p. 1 )

Academic key phrases to contrast and compare findings in a literature review

While some scholars…, others…, the findings of scholar a showcase that… . scholar b , on the other hand, found….

Example: “ The findings of Arinto (2016) call for administrators concerning the design of faculty development programs, provision of faculty support, and strategic planning for online distance learning implementation across the institution. Francisco and Nuqui (2020) on the other hand found that the new normal leadership is an adaptive one while staying strong on their commitment. ” ( Asio and Bayucca, 2021, p. 20 )

Interestingly, all the arguments refer to…

This argument is similar to….

If you are looking to elevate your writing and editing skills, I highly recommend enrolling in the course “ Good with Words: Writing and Editing Specialization “, which is a 4 course series offered by the University of Michigan. This comprehensive program is conveniently available as an online course on Coursera, allowing you to learn at your own pace. Plus, upon successful completion, you’ll have the opportunity to earn a valuable certificate to showcase your newfound expertise!

Academic key phrases to highlight research gaps in a literature review

Yet, it remains unknown how…, there is, however, still little research on…, existing studies have failed to address….

Example: “ University–industry relations (UIR) are usually analysed by the knowledge transfer channels, but existing studies have failed to address what knowledge content is being transferred – impacting the technology output aimed by the partnership.” (Dalmarco et al. 2019, p. 1314 )

Several scholars have recommended to move away…

New approaches are needed to address…, master academia, get new content delivered directly to your inbox, 26 powerful academic phrases to write your introduction (+ real examples), 13 awesome academic phrases to write your methodology (+ real examples), related articles, 10 tips on how to use reference management software smartly and efficiently, separating your self-worth from your phd work, how to introduce yourself in a conference presentation (in six simple steps), how to write effective cover letters for a paper submission.

10 Best Literature Review Tools for Researchers

Boost your research game with these Best Literature Review Tools for Researchers! Uncover hidden gems, organize your findings, and ace your next research paper!

Researchers struggle to identify key sources, extract relevant information, and maintain accuracy while manually conducting literature reviews. This leads to inefficiency, errors, and difficulty in identifying gaps or trends in existing literature.

Table of Contents

Top 10 Literature Review Tools for Researchers: In A Nutshell (2023)

| 1. | Semantic Scholar | Researchers to access and analyze scholarly literature, particularly focused on leveraging AI and semantic analysis |

| 2. | Elicit | Researchers in extracting, organizing, and synthesizing information from various sources, enabling efficient data analysis |

| 3. | Scite.Ai | Determine the credibility and reliability of research articles, facilitating evidence-based decision-making |

| 4. | DistillerSR | Streamlining and enhancing the process of literature screening, study selection, and data extraction |

| 5. | Rayyan | Facilitating efficient screening and selection of research outputs |

| 6. | Consensus | Researchers to work together, annotate, and discuss research papers in real-time, fostering team collaboration and knowledge sharing |

| 7. | RAx | Researchers to perform efficient literature search and analysis, aiding in identifying relevant articles, saving time, and improving the quality of research |

| 8. | Lateral | Discovering relevant scientific articles and identify potential research collaborators based on user interests and preferences |

| 9. | Iris AI | Exploring and mapping the existing literature, identifying knowledge gaps, and generating research questions |

| 10. | Scholarcy | Extracting key information from research papers, aiding in comprehension and saving time |

#1. Semantic Scholar – A free, AI-powered research tool for scientific literature

Not all scholarly content may be indexed, and occasional false positives or inaccurate associations can occur. Furthermore, the tool primarily focuses on computer science and related fields, potentially limiting coverage in other disciplines.

#2. Elicit – Research assistant using language models like GPT-3

Elicit is a game-changing literature review tool that has gained popularity among researchers worldwide. With its user-friendly interface and extensive database of scholarly articles, it streamlines the research process, saving time and effort.

However, users should be cautious when using Elicit. It is important to verify the credibility and accuracy of the sources found through the tool, as the database encompasses a wide range of publications.

#3. Scite.Ai – Your personal research assistant

However, while Scite.Ai offers numerous advantages, there are a few aspects to be cautious about. As with any data-driven tool, occasional errors or inaccuracies may arise, necessitating researchers to cross-reference and verify results with other reputable sources.

Rayyan offers the following paid plans:

#4. DistillerSR – Literature Review Software

Despite occasional technical glitches reported by some users, the developers actively address these issues through updates and improvements, ensuring a better user experience.

#5. Rayyan – AI Powered Tool for Systematic Literature Reviews

However, it’s important to be aware of a few aspects. The free version of Rayyan has limitations, and upgrading to a premium subscription may be necessary for additional functionalities.

#6. Consensus – Use AI to find you answers in scientific research

With Consensus, researchers can save significant time by efficiently organizing and accessing relevant research material.People consider Consensus for several reasons.

Consensus offers both free and paid plans:

#7. RAx – AI-powered reading assistant

#8. lateral – advance your research with ai.

Additionally, researchers must be mindful of potential biases introduced by the tool’s algorithms and should critically evaluate and interpret the results.

#9. Iris AI – Introducing the researcher workspace

Researchers are drawn to this tool because it saves valuable time by automating the tedious task of literature review and provides comprehensive coverage across multiple disciplines.

#10. Scholarcy – Summarize your literature through AI

Scholarcy’s automated summarization may not capture the nuanced interpretations or contextual information presented in the full text.

Final Thoughts

In conclusion, conducting a comprehensive literature review is a crucial aspect of any research project, and the availability of reliable and efficient tools can greatly facilitate this process for researchers. This article has explored the top 10 literature review tools that have gained popularity among researchers.

Q1. What are literature review tools for researchers?

Q2. what criteria should researchers consider when choosing literature review tools.

When choosing literature review tools, researchers should consider factors such as the tool’s search capabilities, database coverage, user interface, collaboration features, citation management, annotation and highlighting options, integration with reference management software, and data extraction capabilities.

Q3. Are there any literature review tools specifically designed for systematic reviews or meta-analyses?

Meta-analysis support: Some literature review tools include statistical analysis features that assist in conducting meta-analyses. These features can help calculate effect sizes, perform statistical tests, and generate forest plots or other visual representations of the meta-analytic results.

Q4. Can literature review tools help with organizing and annotating collected references?

Integration with citation managers: Some literature review tools integrate with popular citation managers like Zotero, Mendeley, or EndNote, allowing seamless transfer of references and annotations between platforms.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 24, Issue 2

- Five tips for developing useful literature summary tables for writing review articles

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0157-5319 Ahtisham Younas 1 , 2 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7839-8130 Parveen Ali 3 , 4

- 1 Memorial University of Newfoundland , St John's , Newfoundland , Canada

- 2 Swat College of Nursing , Pakistan

- 3 School of Nursing and Midwifery , University of Sheffield , Sheffield , South Yorkshire , UK

- 4 Sheffield University Interpersonal Violence Research Group , Sheffield University , Sheffield , UK

- Correspondence to Ahtisham Younas, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St John's, NL A1C 5C4, Canada; ay6133{at}mun.ca

https://doi.org/10.1136/ebnurs-2021-103417

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Introduction

Literature reviews offer a critical synthesis of empirical and theoretical literature to assess the strength of evidence, develop guidelines for practice and policymaking, and identify areas for future research. 1 It is often essential and usually the first task in any research endeavour, particularly in masters or doctoral level education. For effective data extraction and rigorous synthesis in reviews, the use of literature summary tables is of utmost importance. A literature summary table provides a synopsis of an included article. It succinctly presents its purpose, methods, findings and other relevant information pertinent to the review. The aim of developing these literature summary tables is to provide the reader with the information at one glance. Since there are multiple types of reviews (eg, systematic, integrative, scoping, critical and mixed methods) with distinct purposes and techniques, 2 there could be various approaches for developing literature summary tables making it a complex task specialty for the novice researchers or reviewers. Here, we offer five tips for authors of the review articles, relevant to all types of reviews, for creating useful and relevant literature summary tables. We also provide examples from our published reviews to illustrate how useful literature summary tables can be developed and what sort of information should be provided.

Tip 1: provide detailed information about frameworks and methods

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Tabular literature summaries from a scoping review. Source: Rasheed et al . 3

The provision of information about conceptual and theoretical frameworks and methods is useful for several reasons. First, in quantitative (reviews synthesising the results of quantitative studies) and mixed reviews (reviews synthesising the results of both qualitative and quantitative studies to address a mixed review question), it allows the readers to assess the congruence of the core findings and methods with the adapted framework and tested assumptions. In qualitative reviews (reviews synthesising results of qualitative studies), this information is beneficial for readers to recognise the underlying philosophical and paradigmatic stance of the authors of the included articles. For example, imagine the authors of an article, included in a review, used phenomenological inquiry for their research. In that case, the review authors and the readers of the review need to know what kind of (transcendental or hermeneutic) philosophical stance guided the inquiry. Review authors should, therefore, include the philosophical stance in their literature summary for the particular article. Second, information about frameworks and methods enables review authors and readers to judge the quality of the research, which allows for discerning the strengths and limitations of the article. For example, if authors of an included article intended to develop a new scale and test its psychometric properties. To achieve this aim, they used a convenience sample of 150 participants and performed exploratory (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on the same sample. Such an approach would indicate a flawed methodology because EFA and CFA should not be conducted on the same sample. The review authors must include this information in their summary table. Omitting this information from a summary could lead to the inclusion of a flawed article in the review, thereby jeopardising the review’s rigour.

Tip 2: include strengths and limitations for each article

Critical appraisal of individual articles included in a review is crucial for increasing the rigour of the review. Despite using various templates for critical appraisal, authors often do not provide detailed information about each reviewed article’s strengths and limitations. Merely noting the quality score based on standardised critical appraisal templates is not adequate because the readers should be able to identify the reasons for assigning a weak or moderate rating. Many recent critical appraisal checklists (eg, Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool) discourage review authors from assigning a quality score and recommend noting the main strengths and limitations of included studies. It is also vital that methodological and conceptual limitations and strengths of the articles included in the review are provided because not all review articles include empirical research papers. Rather some review synthesises the theoretical aspects of articles. Providing information about conceptual limitations is also important for readers to judge the quality of foundations of the research. For example, if you included a mixed-methods study in the review, reporting the methodological and conceptual limitations about ‘integration’ is critical for evaluating the study’s strength. Suppose the authors only collected qualitative and quantitative data and did not state the intent and timing of integration. In that case, the strength of the study is weak. Integration only occurred at the levels of data collection. However, integration may not have occurred at the analysis, interpretation and reporting levels.

Tip 3: write conceptual contribution of each reviewed article

While reading and evaluating review papers, we have observed that many review authors only provide core results of the article included in a review and do not explain the conceptual contribution offered by the included article. We refer to conceptual contribution as a description of how the article’s key results contribute towards the development of potential codes, themes or subthemes, or emerging patterns that are reported as the review findings. For example, the authors of a review article noted that one of the research articles included in their review demonstrated the usefulness of case studies and reflective logs as strategies for fostering compassion in nursing students. The conceptual contribution of this research article could be that experiential learning is one way to teach compassion to nursing students, as supported by case studies and reflective logs. This conceptual contribution of the article should be mentioned in the literature summary table. Delineating each reviewed article’s conceptual contribution is particularly beneficial in qualitative reviews, mixed-methods reviews, and critical reviews that often focus on developing models and describing or explaining various phenomena. Figure 2 offers an example of a literature summary table. 4

Tabular literature summaries from a critical review. Source: Younas and Maddigan. 4

Tip 4: compose potential themes from each article during summary writing