15 Types of Research Methods

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

Research methods refer to the strategies, tools, and techniques used to gather and analyze data in a structured way in order to answer a research question or investigate a hypothesis (Hammond & Wellington, 2020).

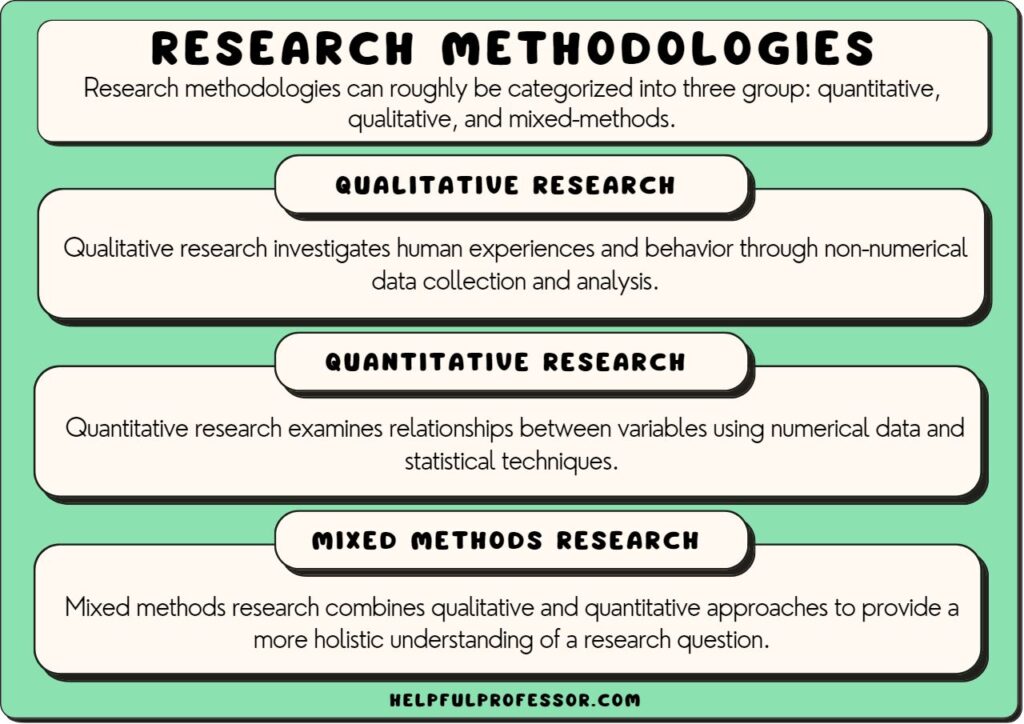

Generally, we place research methods into two categories: quantitative and qualitative. Each has its own strengths and weaknesses, which we can summarize as:

- Quantitative research can achieve generalizability through scrupulous statistical analysis applied to large sample sizes.

- Qualitative research achieves deep, detailed, and nuance accounts of specific case studies, which are not generalizable.

Some researchers, with the aim of making the most of both quantitative and qualitative research, employ mixed methods, whereby they will apply both types of research methods in the one study, such as by conducting a statistical survey alongside in-depth interviews to add context to the quantitative findings.

Below, I’ll outline 15 common research methods, and include pros, cons, and examples of each .

Types of Research Methods

Research methods can be broadly categorized into two types: quantitative and qualitative.

- Quantitative methods involve systematic empirical investigation of observable phenomena via statistical, mathematical, or computational techniques, providing an in-depth understanding of a specific concept or phenomenon (Schweigert, 2021). The strengths of this approach include its ability to produce reliable results that can be generalized to a larger population, although it can lack depth and detail.

- Qualitative methods encompass techniques that are designed to provide a deep understanding of a complex issue, often in a specific context, through collection of non-numerical data (Tracy, 2019). This approach often provides rich, detailed insights but can be time-consuming and its findings may not be generalizable.

These can be further broken down into a range of specific research methods and designs:

| Primarily Quantitative Methods | Primarily Qualitative methods |

|---|---|

| Experimental Research | Case Study |

| Surveys and Questionnaires | Ethnography |

| Longitudinal Studies | Phenomenology |

| Cross-Sectional Studies | Historical research |

| Correlational Research | Content analysis |

| Causal-Comparative Research | Grounded theory |

| Meta-Analysis | Action research |

| Quasi-Experimental Design | Observational research |

Combining the two methods above, mixed methods research mixes elements of both qualitative and quantitative research methods, providing a comprehensive understanding of the research problem . We can further break these down into:

- Sequential Explanatory Design (QUAN→QUAL): This methodology involves conducting quantitative analysis first, then supplementing it with a qualitative study.

- Sequential Exploratory Design (QUAL→QUAN): This methodology goes in the other direction, starting with qualitative analysis and ending with quantitative analysis.

Let’s explore some methods and designs from both quantitative and qualitative traditions, starting with qualitative research methods.

Qualitative Research Methods

Qualitative research methods allow for the exploration of phenomena in their natural settings, providing detailed, descriptive responses and insights into individuals’ experiences and perceptions (Howitt, 2019).

These methods are useful when a detailed understanding of a phenomenon is sought.

1. Ethnographic Research

Ethnographic research emerged out of anthropological research, where anthropologists would enter into a setting for a sustained period of time, getting to know a cultural group and taking detailed observations.

Ethnographers would sometimes even act as participants in the group or culture, which many scholars argue is a weakness because it is a step away from achieving objectivity (Stokes & Wall, 2017).

In fact, at its most extreme version, ethnographers even conduct research on themselves, in a fascinating methodology call autoethnography .

The purpose is to understand the culture, social structure, and the behaviors of the group under study. It is often useful when researchers seek to understand shared cultural meanings and practices in their natural settings.

However, it can be time-consuming and may reflect researcher biases due to the immersion approach.

| Pros of Ethnographic Research | Cons of Ethnographic Research |

|---|---|

| 1. Provides deep cultural insights | 1. Time-consuming |

| 2. Contextually relevant findings | 2. Potential researcher bias |

| 3. Explores dynamic social processes | 3. May |

Example of Ethnography

Liquidated: An Ethnography of Wall Street by Karen Ho involves an anthropologist who embeds herself with Wall Street firms to study the culture of Wall Street bankers and how this culture affects the broader economy and world.

2. Phenomenological Research

Phenomenological research is a qualitative method focused on the study of individual experiences from the participant’s perspective (Tracy, 2019).

It focuses specifically on people’s experiences in relation to a specific social phenomenon ( see here for examples of social phenomena ).

This method is valuable when the goal is to understand how individuals perceive, experience, and make meaning of particular phenomena. However, because it is subjective and dependent on participants’ self-reports, findings may not be generalizable, and are highly reliant on self-reported ‘thoughts and feelings’.

| Pros of Phenomenological Research | Cons of Phenomenological Research |

|---|---|

| 1. Provides rich, detailed data | 1. Limited generalizability |

| 2. Highlights personal experience and perceptions | 2. Data collection can be time-consuming |

| 3. Allows exploration of complex phenomena | 3. Requires highly skilled researchers |

Example of Phenomenological Research

A phenomenological approach to experiences with technology by Sebnem Cilesiz represents a good starting-point for formulating a phenomenological study. With its focus on the ‘essence of experience’, this piece presents methodological, reliability, validity, and data analysis techniques that phenomenologists use to explain how people experience technology in their everyday lives.

3. Historical Research

Historical research is a qualitative method involving the examination of past events to draw conclusions about the present or make predictions about the future (Stokes & Wall, 2017).

As you might expect, it’s common in the research branches of history departments in universities.

This approach is useful in studies that seek to understand the past to interpret present events or trends. However, it relies heavily on the availability and reliability of source materials, which may be limited.

Common data sources include cultural artifacts from both material and non-material culture , which are then examined, compared, contrasted, and contextualized to test hypotheses and generate theories.

| Pros of Historical Research | Cons of Historical Research |

|---|---|

| 1. | 1. Dependent on available sources |

| 2. Can help understand current events or trends | 2. Potential bias in source materials |

| 3. Allows the study of change over time | 3. Difficult to replicate |

Example of Historical Research

A historical research example might be a study examining the evolution of gender roles over the last century. This research might involve the analysis of historical newspapers, advertisements, letters, and company documents, as well as sociocultural contexts.

4. Content Analysis

Content analysis is a research method that involves systematic and objective coding and interpreting of text or media to identify patterns, themes, ideologies, or biases (Schweigert, 2021).

A content analysis is useful in analyzing communication patterns, helping to reveal how texts such as newspapers, movies, films, political speeches, and other types of ‘content’ contain narratives and biases.

However, interpretations can be very subjective, which often requires scholars to engage in practices such as cross-comparing their coding with peers or external researchers.

Content analysis can be further broken down in to other specific methodologies such as semiotic analysis, multimodal analysis , and discourse analysis .

| Pros of Content Analysis | Cons of Content Analysis |

|---|---|

| 1. Unobtrusive data collection | 1. Lacks contextual information |

| 2. Allows for large sample analysis | 2. Potential coder bias |

| 3. Replicable and reliable if done properly | 3. May overlook nuances |

Example of Content Analysis

How is Islam Portrayed in Western Media? by Poorebrahim and Zarei (2013) employs a type of content analysis called critical discourse analysis (common in poststructuralist and critical theory research ). This study by Poorebrahum and Zarei combs through a corpus of western media texts to explore the language forms that are used in relation to Islam and Muslims, finding that they are overly stereotyped, which may represent anti-Islam bias or failure to understand the Islamic world.

5. Grounded Theory Research

Grounded theory involves developing a theory during and after data collection rather than beforehand.

This is in contrast to most academic research studies, which start with a hypothesis or theory and then testing of it through a study, where we might have a null hypothesis (disproving the theory) and an alternative hypothesis (supporting the theory).

Grounded Theory is useful because it keeps an open mind to what the data might reveal out of the research. It can be time-consuming and requires rigorous data analysis (Tracy, 2019).

| Pros of Grounded Theory Research | Cons of Grounded Theory Research |

|---|---|

| 1. Helps with theory development | 1. Time-consuming |

| 2. Rigorous data analysis | 2. Requires iterative data collection and analysis |

| 3. Can fill gaps in existing theories | 3. Requires skilled researchers |

Grounded Theory Example

Developing a Leadership Identity by Komives et al (2005) employs a grounded theory approach to develop a thesis based on the data rather than testing a hypothesis. The researchers studied the leadership identity of 13 college students taking on leadership roles. Based on their interviews, the researchers theorized that the students’ leadership identities shifted from a hierarchical view of leadership to one that embraced leadership as a collaborative concept.

6. Action Research

Action research is an approach which aims to solve real-world problems and bring about change within a setting. The study is designed to solve a specific problem – or in other words, to take action (Patten, 2017).

This approach can involve mixed methods, but is generally qualitative because it usually involves the study of a specific case study wherein the researcher works, e.g. a teacher studying their own classroom practice to seek ways they can improve.

Action research is very common in fields like education and nursing where practitioners identify areas for improvement then implement a study in order to find paths forward.

| Pros of Action Research | Cons of Action Research |

|---|---|

| 1. Addresses real-world problems and seeks to find solutions. | 1. It is time-consuming and often hard to implement into a practitioner’s already busy schedule |

| 2. Integrates research and action in an action-research cycle. | 2. Requires collaboration between researcher, practitioner, and research participants. |

| 3. Can bring about positive change in isolated instances, such as in a school or nursery setting. | 3. Complexity of managing dual roles (where the researcher is also often the practitioner) |

Action Research Example

Using Digital Sandbox Gaming to Improve Creativity Within Boys’ Writing by Ellison and Drew was a research study one of my research students completed in his own classroom under my supervision. He implemented a digital game-based approach to literacy teaching with boys and interviewed his students to see if the use of games as stimuli for storytelling helped draw them into the learning experience.

7. Natural Observational Research

Observational research can also be quantitative (see: experimental research), but in naturalistic settings for the social sciences, researchers tend to employ qualitative data collection methods like interviews and field notes to observe people in their day-to-day environments.

This approach involves the observation and detailed recording of behaviors in their natural settings (Howitt, 2019). It can provide rich, in-depth information, but the researcher’s presence might influence behavior.

While observational research has some overlaps with ethnography (especially in regard to data collection techniques), it tends not to be as sustained as ethnography, e.g. a researcher might do 5 observations, every second Monday, as opposed to being embedded in an environment.

| Pros of Qualitative Observational Research | Cons of Qualitative Observational Research |

|---|---|

| 1. Captures behavior in natural settings, allowing for interesting insights into authentic behaviors. | 1. Researcher’s presence may influence behavior |

| 2. Can provide rich, detailed data through the researcher’s vignettes. | 2. Can be time-consuming |

| 3. Non-invasive because researchers want to observe natural activities rather than interfering with research participants. | 3. Requires skilled and trained observers |

Observational Research Example

A researcher might use qualitative observational research to study the behaviors and interactions of children at a playground. The researcher would document the behaviors observed, such as the types of games played, levels of cooperation , and instances of conflict.

8. Case Study Research

Case study research is a qualitative method that involves a deep and thorough investigation of a single individual, group, or event in order to explore facets of that phenomenon that cannot be captured using other methods (Stokes & Wall, 2017).

Case study research is especially valuable in providing contextualized insights into specific issues, facilitating the application of abstract theories to real-world situations (Patten, 2017).

However, findings from a case study may not be generalizable due to the specific context and the limited number of cases studied (Walliman, 2021).

| Pros of Case Study Research | Cons of Case Study Research |

|---|---|

| 1. Provides detailed insights | 1. Limited generalizability |

| 2. Facilitates the study of complex phenomena | 2. Can be time-consuming |

| 3. Can test or generate theories | 3. Subject to observer bias |

See More: Case Study Advantages and Disadvantages

Example of a Case Study

Scholars conduct a detailed exploration of the implementation of a new teaching method within a classroom setting. The study focuses on how the teacher and students adapt to the new method, the challenges encountered, and the outcomes on student performance and engagement. While the study provides specific and detailed insights of the teaching method in that classroom, it cannot be generalized to other classrooms, as statistical significance has not been established through this qualitative approach.

Quantitative Research Methods

Quantitative research methods involve the systematic empirical investigation of observable phenomena via statistical, mathematical, or computational techniques (Pajo, 2022). The focus is on gathering numerical data and generalizing it across groups of people or to explain a particular phenomenon.

9. Experimental Research

Experimental research is a quantitative method where researchers manipulate one variable to determine its effect on another (Walliman, 2021).

This is common, for example, in high-school science labs, where students are asked to introduce a variable into a setting in order to examine its effect.

This type of research is useful in situations where researchers want to determine causal relationships between variables. However, experimental conditions may not reflect real-world conditions.

| Pros of Experimental Research | Cons of Experimental Research |

|---|---|

| 1. Allows for determination of causality | 1. Might not reflect real-world conditions |

| 2. Allows for the study of phenomena in highly controlled environments to minimize research contamination. | 2. Can be costly and time-consuming to create a controlled environment. |

| 3. Can be replicated so other researchers can test and verify the results. | 3. Ethical concerns need to be addressed as the research is directly manipulating variables. |

Example of Experimental Research

A researcher may conduct an experiment to determine the effects of a new educational approach on student learning outcomes. Students would be randomly assigned to either the control group (traditional teaching method) or the experimental group (new educational approach).

10. Surveys and Questionnaires

Surveys and questionnaires are quantitative methods that involve asking research participants structured and predefined questions to collect data about their attitudes, beliefs, behaviors, or characteristics (Patten, 2017).

Surveys are beneficial for collecting data from large samples, but they depend heavily on the honesty and accuracy of respondents.

They tend to be seen as more authoritative than their qualitative counterparts, semi-structured interviews, because the data is quantifiable (e.g. a questionnaire where information is presented on a scale from 1 to 10 can allow researchers to determine and compare statistical means, averages, and variations across sub-populations in the study).

| Pros of Surveys and Questionnaires | Cons of Surveys and Questionnaires |

|---|---|

| 1. Data can be gathered from larger samples than is possible in qualitative research. | 1. There is heavy dependence on respondent honesty |

| 2. The data is quantifiable, allowing for comparison across subpopulations | 2. There is limited depth of response as opposed to qualitative approaches. |

| 3. Can be cost-effective and time-efficient | 3. Static with no flexibility to explore responses (unlike semi- or unstrcutured interviewing) |

Example of a Survey Study

A company might use a survey to gather data about employee job satisfaction across its offices worldwide. Employees would be asked to rate various aspects of their job satisfaction on a Likert scale. While this method provides a broad overview, it may lack the depth of understanding possible with other methods (Stokes & Wall, 2017).

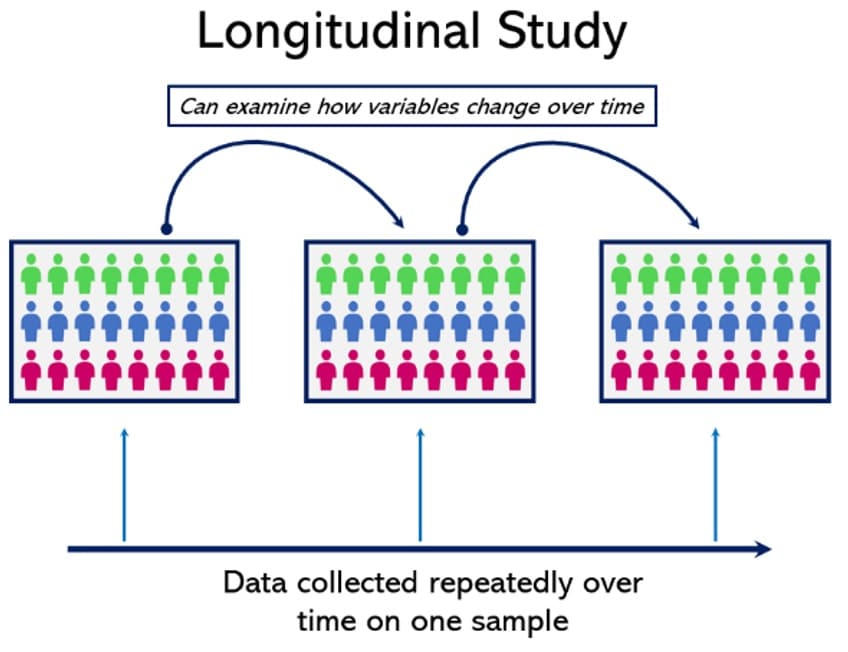

11. Longitudinal Studies

Longitudinal studies involve repeated observations of the same variables over extended periods (Howitt, 2019). These studies are valuable for tracking development and change but can be costly and time-consuming.

With multiple data points collected over extended periods, it’s possible to examine continuous changes within things like population dynamics or consumer behavior. This makes a detailed analysis of change possible.

Perhaps the most relatable example of a longitudinal study is a national census, which is taken on the same day every few years, to gather comparative demographic data that can show how a nation is changing over time.

While longitudinal studies are commonly quantitative, there are also instances of qualitative ones as well, such as the famous 7 Up study from the UK, which studies 14 individuals every 7 years to explore their development over their lives.

| Pros of Longitudinal Studies | Cons of Longitudinal Studies |

|---|---|

| 1. Tracks changes over time allowing for comparison of past to present events. | 1. Is almost by definition time-consuming because time needs to pass between each data collection session. |

| 2. Can identify sequences of events, but causality is often harder to determine. | 2. There is high risk of participant dropout over time as participants move on with their lives. |

Example of a Longitudinal Study

A national census, taken every few years, uses surveys to develop longitudinal data, which is then compared and analyzed to present accurate trends over time. Trends a census can reveal include changes in religiosity, values and attitudes on social issues, and much more.

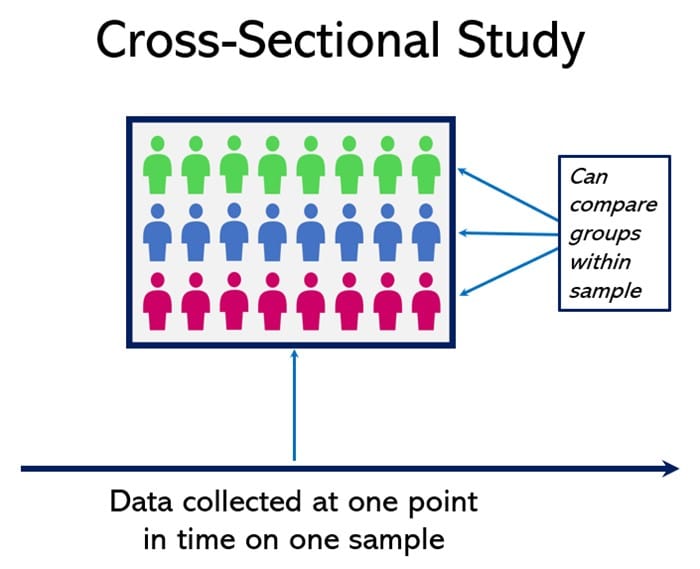

12. Cross-Sectional Studies

Cross-sectional studies are a quantitative research method that involves analyzing data from a population at a specific point in time (Patten, 2017). They provide a snapshot of a situation but cannot determine causality.

This design is used to measure and compare the prevalence of certain characteristics or outcomes in different groups within the sampled population.

The major advantage of cross-sectional design is its ability to measure a wide range of variables simultaneously without needing to follow up with participants over time.

However, cross-sectional studies do have limitations . This design can only show if there are associations or correlations between different variables, but cannot prove cause and effect relationships, temporal sequence, changes, and trends over time.

| Pros of Cross-Sectional Studies | Cons of Cross-Sectional Studies |

|---|---|

| 1. Quick and inexpensive, with no long-term commitment required. | 1. Cannot determine causality because it is a simple snapshot, with no time delay between data collection points. |

| 2. Good for descriptive analyses. | 2. Does not allow researchers to follow up with research participants. |

Example of a Cross-Sectional Study

Our longitudinal study example of a national census also happens to contain cross-sectional design. One census is cross-sectional, displaying only data from one point in time. But when a census is taken once every few years, it becomes longitudinal, and so long as the data collection technique remains unchanged, identification of changes will be achievable, adding another time dimension on top of a basic cross-sectional study.

13. Correlational Research

Correlational research is a quantitative method that seeks to determine if and to what degree a relationship exists between two or more quantifiable variables (Schweigert, 2021).

This approach provides a fast and easy way to make initial hypotheses based on either positive or negative correlation trends that can be observed within dataset.

While correlational research can reveal relationships between variables, it cannot establish causality.

Methods used for data analysis may include statistical correlations such as Pearson’s or Spearman’s.

| Pros of Correlational Research | Cons of Correlational Research |

|---|---|

| 1. Reveals relationships between variables | 1. Cannot determine causality |

| 2. Can use existing data | 2. May be |

| 3. Can guide further experimental research | 3. Correlation may be coincidental |

Example of Correlational Research

A team of researchers is interested in studying the relationship between the amount of time students spend studying and their academic performance. They gather data from a high school, measuring the number of hours each student studies per week and their grade point averages (GPAs) at the end of the semester. Upon analyzing the data, they find a positive correlation, suggesting that students who spend more time studying tend to have higher GPAs.

14. Quasi-Experimental Design Research

Quasi-experimental design research is a quantitative research method that is similar to experimental design but lacks the element of random assignment to treatment or control.

Instead, quasi-experimental designs typically rely on certain other methods to control for extraneous variables.

The term ‘quasi-experimental’ implies that the experiment resembles a true experiment, but it is not exactly the same because it doesn’t meet all the criteria for a ‘true’ experiment, specifically in terms of control and random assignment.

Quasi-experimental design is useful when researchers want to study a causal hypothesis or relationship, but practical or ethical considerations prevent them from manipulating variables and randomly assigning participants to conditions.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| 1. It’s more feasible to implement than true experiments. | 1. Without random assignment, it’s harder to rule out confounding variables. |

| 2. It can be conducted in real-world settings, making the findings more applicable to the real world. | 2. The lack of random assignment may of the study. |

| 3. Useful when it’s unethical or impossible to manipulate the independent variable or randomly assign participants. | 3. It’s more difficult to establish a cause-effect relationship due to the potential for confounding variables. |

Example of Quasi-Experimental Design

A researcher wants to study the impact of a new math tutoring program on student performance. However, ethical and practical constraints prevent random assignment to the “tutoring” and “no tutoring” groups. Instead, the researcher compares students who chose to receive tutoring (experimental group) to similar students who did not choose to receive tutoring (control group), controlling for other variables like grade level and previous math performance.

Related: Examples and Types of Random Assignment in Research

15. Meta-Analysis Research

Meta-analysis statistically combines the results of multiple studies on a specific topic to yield a more precise estimate of the effect size. It’s the gold standard of secondary research .

Meta-analysis is particularly useful when there are numerous studies on a topic, and there is a need to integrate the findings to draw more reliable conclusions.

Some meta-analyses can identify flaws or gaps in a corpus of research, when can be highly influential in academic research, despite lack of primary data collection.

However, they tend only to be feasible when there is a sizable corpus of high-quality and reliable studies into a phenomenon.

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Increased Statistical Power: By combining data from multiple studies, meta-analysis increases the statistical power to detect effects. | Publication Bias: Studies with null or negative findings are less likely to be published, leading to an overestimation of effect sizes. |

| Greater Precision: It provides more precise estimates of effect sizes by reducing the influence of random error. | Quality of Studies: of a meta-analysis depends on the quality of the studies included. |

| Resolving Discrepancies: Meta-analysis can help resolve disagreements between different studies on a topic. | Heterogeneity: Differences in study design, sample, or procedures can introduce heterogeneity, complicating interpretation of results. |

Example of a Meta-Analysis

The power of feedback revisited (Wisniewski, Zierer & Hattie, 2020) is a meta-analysis that examines 435 empirical studies research on the effects of feedback on student learning. They use a random-effects model to ascertain whether there is a clear effect size across the literature. The authors find that feedback tends to impact cognitive and motor skill outcomes but has less of an effect on motivational and behavioral outcomes.

Choosing a research method requires a lot of consideration regarding what you want to achieve, your research paradigm, and the methodology that is most valuable for what you are studying. There are multiple types of research methods, many of which I haven’t been able to present here. Generally, it’s recommended that you work with an experienced researcher or research supervisor to identify a suitable research method for your study at hand.

Hammond, M., & Wellington, J. (2020). Research methods: The key concepts . New York: Routledge.

Howitt, D. (2019). Introduction to qualitative research methods in psychology . London: Pearson UK.

Pajo, B. (2022). Introduction to research methods: A hands-on approach . New York: Sage Publications.

Patten, M. L. (2017). Understanding research methods: An overview of the essentials . New York: Sage

Schweigert, W. A. (2021). Research methods in psychology: A handbook . Los Angeles: Waveland Press.

Stokes, P., & Wall, T. (2017). Research methods . New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Tracy, S. J. (2019). Qualitative research methods: Collecting evidence, crafting analysis, communicating impact . London: John Wiley & Sons.

Walliman, N. (2021). Research methods: The basics. London: Routledge.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

Here's What You Need to Understand About Research Methodology

Table of Contents

Research methodology involves a systematic and well-structured approach to conducting scholarly or scientific inquiries. Knowing the significance of research methodology and its different components is crucial as it serves as the basis for any study.

Typically, your research topic will start as a broad idea you want to investigate more thoroughly. Once you’ve identified a research problem and created research questions , you must choose the appropriate methodology and frameworks to address those questions effectively.

What is the definition of a research methodology?

Research methodology is the process or the way you intend to execute your study. The methodology section of a research paper outlines how you plan to conduct your study. It covers various steps such as collecting data, statistical analysis, observing participants, and other procedures involved in the research process

The methods section should give a description of the process that will convert your idea into a study. Additionally, the outcomes of your process must provide valid and reliable results resonant with the aims and objectives of your research. This thumb rule holds complete validity, no matter whether your paper has inclinations for qualitative or quantitative usage.

Studying research methods used in related studies can provide helpful insights and direction for your own research. Now easily discover papers related to your topic on SciSpace and utilize our AI research assistant, Copilot , to quickly review the methodologies applied in different papers.

The need for a good research methodology

While deciding on your approach towards your research, the reason or factors you weighed in choosing a particular problem and formulating a research topic need to be validated and explained. A research methodology helps you do exactly that. Moreover, a good research methodology lets you build your argument to validate your research work performed through various data collection methods, analytical methods, and other essential points.

Just imagine it as a strategy documented to provide an overview of what you intend to do.

While undertaking any research writing or performing the research itself, you may get drifted in not something of much importance. In such a case, a research methodology helps you to get back to your outlined work methodology.

A research methodology helps in keeping you accountable for your work. Additionally, it can help you evaluate whether your work is in sync with your original aims and objectives or not. Besides, a good research methodology enables you to navigate your research process smoothly and swiftly while providing effective planning to achieve your desired results.

What is the basic structure of a research methodology?

Usually, you must ensure to include the following stated aspects while deciding over the basic structure of your research methodology:

1. Your research procedure

Explain what research methods you’re going to use. Whether you intend to proceed with quantitative or qualitative, or a composite of both approaches, you need to state that explicitly. The option among the three depends on your research’s aim, objectives, and scope.

2. Provide the rationality behind your chosen approach

Based on logic and reason, let your readers know why you have chosen said research methodologies. Additionally, you have to build strong arguments supporting why your chosen research method is the best way to achieve the desired outcome.

3. Explain your mechanism

The mechanism encompasses the research methods or instruments you will use to develop your research methodology. It usually refers to your data collection methods. You can use interviews, surveys, physical questionnaires, etc., of the many available mechanisms as research methodology instruments. The data collection method is determined by the type of research and whether the data is quantitative data(includes numerical data) or qualitative data (perception, morale, etc.) Moreover, you need to put logical reasoning behind choosing a particular instrument.

4. Significance of outcomes

The results will be available once you have finished experimenting. However, you should also explain how you plan to use the data to interpret the findings. This section also aids in understanding the problem from within, breaking it down into pieces, and viewing the research problem from various perspectives.

5. Reader’s advice

Anything that you feel must be explained to spread more awareness among readers and focus groups must be included and described in detail. You should not just specify your research methodology on the assumption that a reader is aware of the topic.

All the relevant information that explains and simplifies your research paper must be included in the methodology section. If you are conducting your research in a non-traditional manner, give a logical justification and list its benefits.

6. Explain your sample space

Include information about the sample and sample space in the methodology section. The term "sample" refers to a smaller set of data that a researcher selects or chooses from a larger group of people or focus groups using a predetermined selection method. Let your readers know how you are going to distinguish between relevant and non-relevant samples. How you figured out those exact numbers to back your research methodology, i.e. the sample spacing of instruments, must be discussed thoroughly.

For example, if you are going to conduct a survey or interview, then by what procedure will you select the interviewees (or sample size in case of surveys), and how exactly will the interview or survey be conducted.

7. Challenges and limitations

This part, which is frequently assumed to be unnecessary, is actually very important. The challenges and limitations that your chosen strategy inherently possesses must be specified while you are conducting different types of research.

The importance of a good research methodology

You must have observed that all research papers, dissertations, or theses carry a chapter entirely dedicated to research methodology. This section helps maintain your credibility as a better interpreter of results rather than a manipulator.

A good research methodology always explains the procedure, data collection methods and techniques, aim, and scope of the research. In a research study, it leads to a well-organized, rationality-based approach, while the paper lacking it is often observed as messy or disorganized.

You should pay special attention to validating your chosen way towards the research methodology. This becomes extremely important in case you select an unconventional or a distinct method of execution.

Curating and developing a strong, effective research methodology can assist you in addressing a variety of situations, such as:

- When someone tries to duplicate or expand upon your research after few years.

- If a contradiction or conflict of facts occurs at a later time. This gives you the security you need to deal with these contradictions while still being able to defend your approach.

- Gaining a tactical approach in getting your research completed in time. Just ensure you are using the right approach while drafting your research methodology, and it can help you achieve your desired outcomes. Additionally, it provides a better explanation and understanding of the research question itself.

- Documenting the results so that the final outcome of the research stays as you intended it to be while starting.

Instruments you could use while writing a good research methodology

As a researcher, you must choose which tools or data collection methods that fit best in terms of the relevance of your research. This decision has to be wise.

There exists many research equipments or tools that you can use to carry out your research process. These are classified as:

a. Interviews (One-on-One or a Group)

An interview aimed to get your desired research outcomes can be undertaken in many different ways. For example, you can design your interview as structured, semi-structured, or unstructured. What sets them apart is the degree of formality in the questions. On the other hand, in a group interview, your aim should be to collect more opinions and group perceptions from the focus groups on a certain topic rather than looking out for some formal answers.

In surveys, you are in better control if you specifically draft the questions you seek the response for. For example, you may choose to include free-style questions that can be answered descriptively, or you may provide a multiple-choice type response for questions. Besides, you can also opt to choose both ways, deciding what suits your research process and purpose better.

c. Sample Groups

Similar to the group interviews, here, you can select a group of individuals and assign them a topic to discuss or freely express their opinions over that. You can simultaneously note down the answers and later draft them appropriately, deciding on the relevance of every response.

d. Observations

If your research domain is humanities or sociology, observations are the best-proven method to draw your research methodology. Of course, you can always include studying the spontaneous response of the participants towards a situation or conducting the same but in a more structured manner. A structured observation means putting the participants in a situation at a previously decided time and then studying their responses.

Of all the tools described above, it is you who should wisely choose the instruments and decide what’s the best fit for your research. You must not restrict yourself from multiple methods or a combination of a few instruments if appropriate in drafting a good research methodology.

Types of research methodology

A research methodology exists in various forms. Depending upon their approach, whether centered around words, numbers, or both, methodologies are distinguished as qualitative, quantitative, or an amalgamation of both.

1. Qualitative research methodology

When a research methodology primarily focuses on words and textual data, then it is generally referred to as qualitative research methodology. This type is usually preferred among researchers when the aim and scope of the research are mainly theoretical and explanatory.

The instruments used are observations, interviews, and sample groups. You can use this methodology if you are trying to study human behavior or response in some situations. Generally, qualitative research methodology is widely used in sociology, psychology, and other related domains.

2. Quantitative research methodology

If your research is majorly centered on data, figures, and stats, then analyzing these numerical data is often referred to as quantitative research methodology. You can use quantitative research methodology if your research requires you to validate or justify the obtained results.

In quantitative methods, surveys, tests, experiments, and evaluations of current databases can be advantageously used as instruments If your research involves testing some hypothesis, then use this methodology.

3. Amalgam methodology

As the name suggests, the amalgam methodology uses both quantitative and qualitative approaches. This methodology is used when a part of the research requires you to verify the facts and figures, whereas the other part demands you to discover the theoretical and explanatory nature of the research question.

The instruments for the amalgam methodology require you to conduct interviews and surveys, including tests and experiments. The outcome of this methodology can be insightful and valuable as it provides precise test results in line with theoretical explanations and reasoning.

The amalgam method, makes your work both factual and rational at the same time.

Final words: How to decide which is the best research methodology?

If you have kept your sincerity and awareness intact with the aims and scope of research well enough, you must have got an idea of which research methodology suits your work best.

Before deciding which research methodology answers your research question, you must invest significant time in reading and doing your homework for that. Taking references that yield relevant results should be your first approach to establishing a research methodology.

Moreover, you should never refrain from exploring other options. Before setting your work in stone, you must try all the available options as it explains why the choice of research methodology that you finally make is more appropriate than the other available options.

You should always go for a quantitative research methodology if your research requires gathering large amounts of data, figures, and statistics. This research methodology will provide you with results if your research paper involves the validation of some hypothesis.

Whereas, if you are looking for more explanations, reasons, opinions, and public perceptions around a theory, you must use qualitative research methodology.The choice of an appropriate research methodology ultimately depends on what you want to achieve through your research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about Research Methodology

1. how to write a research methodology.

You can always provide a separate section for research methodology where you should specify details about the methods and instruments used during the research, discussions on result analysis, including insights into the background information, and conveying the research limitations.

2. What are the types of research methodology?

There generally exists four types of research methodology i.e.

- Observation

- Experimental

- Derivational

3. What is the true meaning of research methodology?

The set of techniques or procedures followed to discover and analyze the information gathered to validate or justify a research outcome is generally called Research Methodology.

4. Where lies the importance of research methodology?

Your research methodology directly reflects the validity of your research outcomes and how well-informed your research work is. Moreover, it can help future researchers cite or refer to your research if they plan to use a similar research methodology.

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Using AI for research: A beginner’s guide

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Methods | Definition, Types, Examples

Research methods are specific procedures for collecting and analysing data. Developing your research methods is an integral part of your research design . When planning your methods, there are two key decisions you will make.

First, decide how you will collect data . Your methods depend on what type of data you need to answer your research question :

- Qualitative vs quantitative : Will your data take the form of words or numbers?

- Primary vs secondary : Will you collect original data yourself, or will you use data that have already been collected by someone else?

- Descriptive vs experimental : Will you take measurements of something as it is, or will you perform an experiment?

Second, decide how you will analyse the data .

- For quantitative data, you can use statistical analysis methods to test relationships between variables.

- For qualitative data, you can use methods such as thematic analysis to interpret patterns and meanings in the data.

Table of contents

Methods for collecting data, examples of data collection methods, methods for analysing data, examples of data analysis methods, frequently asked questions about methodology.

Data are the information that you collect for the purposes of answering your research question . The type of data you need depends on the aims of your research.

Qualitative vs quantitative data

Your choice of qualitative or quantitative data collection depends on the type of knowledge you want to develop.

For questions about ideas, experiences and meanings, or to study something that can’t be described numerically, collect qualitative data .

If you want to develop a more mechanistic understanding of a topic, or your research involves hypothesis testing , collect quantitative data .

| Qualitative | ||

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | . |

You can also take a mixed methods approach, where you use both qualitative and quantitative research methods.

Primary vs secondary data

Primary data are any original information that you collect for the purposes of answering your research question (e.g. through surveys , observations and experiments ). Secondary data are information that has already been collected by other researchers (e.g. in a government census or previous scientific studies).

If you are exploring a novel research question, you’ll probably need to collect primary data. But if you want to synthesise existing knowledge, analyse historical trends, or identify patterns on a large scale, secondary data might be a better choice.

| Primary | ||

|---|---|---|

| Secondary |

Descriptive vs experimental data

In descriptive research , you collect data about your study subject without intervening. The validity of your research will depend on your sampling method .

In experimental research , you systematically intervene in a process and measure the outcome. The validity of your research will depend on your experimental design .

To conduct an experiment, you need to be able to vary your independent variable , precisely measure your dependent variable, and control for confounding variables . If it’s practically and ethically possible, this method is the best choice for answering questions about cause and effect.

| Descriptive | ||

|---|---|---|

| Experimental |

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

| Research method | Primary or secondary? | Qualitative or quantitative? | When to use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Quantitative | To test cause-and-effect relationships. | |

| Primary | Quantitative | To understand general characteristics of a population. | |

| Interview/focus group | Primary | Qualitative | To gain more in-depth understanding of a topic. |

| Observation | Primary | Either | To understand how something occurs in its natural setting. |

| Secondary | Either | To situate your research in an existing body of work, or to evaluate trends within a research topic. | |

| Either | Either | To gain an in-depth understanding of a specific group or context, or when you don’t have the resources for a large study. |

Your data analysis methods will depend on the type of data you collect and how you prepare them for analysis.

Data can often be analysed both quantitatively and qualitatively. For example, survey responses could be analysed qualitatively by studying the meanings of responses or quantitatively by studying the frequencies of responses.

Qualitative analysis methods

Qualitative analysis is used to understand words, ideas, and experiences. You can use it to interpret data that were collected:

- From open-ended survey and interview questions, literature reviews, case studies, and other sources that use text rather than numbers.

- Using non-probability sampling methods .

Qualitative analysis tends to be quite flexible and relies on the researcher’s judgement, so you have to reflect carefully on your choices and assumptions.

Quantitative analysis methods

Quantitative analysis uses numbers and statistics to understand frequencies, averages and correlations (in descriptive studies) or cause-and-effect relationships (in experiments).

You can use quantitative analysis to interpret data that were collected either:

- During an experiment.

- Using probability sampling methods .

Because the data are collected and analysed in a statistically valid way, the results of quantitative analysis can be easily standardised and shared among researchers.

| Research method | Qualitative or quantitative? | When to use |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | To analyse data collected in a statistically valid manner (e.g. from experiments, surveys, and observations). | |

| Meta-analysis | Quantitative | To statistically analyse the results of a large collection of studies. Can only be applied to studies that collected data in a statistically valid manner. |

| Qualitative | To analyse data collected from interviews, focus groups or textual sources. To understand general themes in the data and how they are communicated. | |

| Either | To analyse large volumes of textual or visual data collected from surveys, literature reviews, or other sources. Can be quantitative (i.e. frequencies of words) or qualitative (i.e. meanings of words). |

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to test a hypothesis by systematically collecting and analysing data, while qualitative methods allow you to explore ideas and experiences in depth.

In mixed methods research , you use both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis methods to answer your research question .

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Methodology refers to the overarching strategy and rationale of your research project . It involves studying the methods used in your field and the theories or principles behind them, in order to develop an approach that matches your objectives.

Methods are the specific tools and procedures you use to collect and analyse data (e.g. experiments, surveys , and statistical tests ).

In shorter scientific papers, where the aim is to report the findings of a specific study, you might simply describe what you did in a methods section .

In a longer or more complex research project, such as a thesis or dissertation , you will probably include a methodology section , where you explain your approach to answering the research questions and cite relevant sources to support your choice of methods.

Is this article helpful?

More interesting articles.

- A Quick Guide to Experimental Design | 5 Steps & Examples

- Between-Subjects Design | Examples, Pros & Cons

- Case Study | Definition, Examples & Methods

- Cluster Sampling | A Simple Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- Confounding Variables | Definition, Examples & Controls

- Construct Validity | Definition, Types, & Examples

- Content Analysis | A Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- Control Groups and Treatment Groups | Uses & Examples

- Controlled Experiments | Methods & Examples of Control

- Correlation vs Causation | Differences, Designs & Examples

- Correlational Research | Guide, Design & Examples

- Critical Discourse Analysis | Definition, Guide & Examples

- Cross-Sectional Study | Definitions, Uses & Examples

- Data Cleaning | A Guide with Examples & Steps

- Data Collection Methods | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

- Descriptive Research Design | Definition, Methods & Examples

- Doing Survey Research | A Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

- Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples

- Explanatory Research | Definition, Guide, & Examples

- Explanatory vs Response Variables | Definitions & Examples

- Exploratory Research | Definition, Guide, & Examples

- External Validity | Types, Threats & Examples

- Extraneous Variables | Examples, Types, Controls

- Face Validity | Guide with Definition & Examples

- How to Do Thematic Analysis | Guide & Examples

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Guide & Examples

- Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria | Examples & Definition

- Independent vs Dependent Variables | Definition & Examples

- Inductive Reasoning | Types, Examples, Explanation

- Inductive vs Deductive Research Approach (with Examples)

- Internal Validity | Definition, Threats & Examples

- Internal vs External Validity | Understanding Differences & Examples

- Longitudinal Study | Definition, Approaches & Examples

- Mediator vs Moderator Variables | Differences & Examples

- Mixed Methods Research | Definition, Guide, & Examples

- Multistage Sampling | An Introductory Guide with Examples

- Naturalistic Observation | Definition, Guide & Examples

- Operationalisation | A Guide with Examples, Pros & Cons

- Population vs Sample | Definitions, Differences & Examples

- Primary Research | Definition, Types, & Examples

- Qualitative vs Quantitative Research | Examples & Methods

- Quasi-Experimental Design | Definition, Types & Examples

- Questionnaire Design | Methods, Question Types & Examples

- Random Assignment in Experiments | Introduction & Examples

- Reliability vs Validity in Research | Differences, Types & Examples

- Reproducibility vs Replicability | Difference & Examples

- Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- Sampling Methods | Types, Techniques, & Examples

- Semi-Structured Interview | Definition, Guide & Examples

- Simple Random Sampling | Definition, Steps & Examples

- Stratified Sampling | A Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- Structured Interview | Definition, Guide & Examples

- Systematic Review | Definition, Examples & Guide

- Systematic Sampling | A Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

- Textual Analysis | Guide, 3 Approaches & Examples

- The 4 Types of Reliability in Research | Definitions & Examples

- The 4 Types of Validity | Types, Definitions & Examples

- Transcribing an Interview | 5 Steps & Transcription Software

- Triangulation in Research | Guide, Types, Examples

- Types of Interviews in Research | Guide & Examples

- Types of Research Designs Compared | Examples

- Types of Variables in Research | Definitions & Examples

- Unstructured Interview | Definition, Guide & Examples

- What Are Control Variables | Definition & Examples

- What Is a Case-Control Study? | Definition & Examples

- What Is a Cohort Study? | Definition & Examples

- What Is a Conceptual Framework? | Tips & Examples

- What Is a Double-Barrelled Question?

- What Is a Double-Blind Study? | Introduction & Examples

- What Is a Focus Group? | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

- What Is a Likert Scale? | Guide & Examples

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

- What Is a Prospective Cohort Study? | Definition & Examples

- What Is a Retrospective Cohort Study? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Action Research? | Definition & Examples

- What Is an Observational Study? | Guide & Examples

- What Is Concurrent Validity? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Content Validity? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Convenience Sampling? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Convergent Validity? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Criterion Validity? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Deductive Reasoning? | Explanation & Examples

- What Is Discriminant Validity? | Definition & Example

- What Is Ecological Validity? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Ethnography? | Meaning, Guide & Examples

- What Is Non-Probability Sampling? | Types & Examples

- What Is Participant Observation? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

- What Is Predictive Validity? | Examples & Definition

- What Is Probability Sampling? | Types & Examples

- What Is Purposive Sampling? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Qualitative Observation? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

- What Is Quantitative Observation? | Definition & Examples

- What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition & Methods

- What Is Quota Sampling? | Definition & Examples

- What is Secondary Research? | Definition, Types, & Examples

- What Is Snowball Sampling? | Definition & Examples

- Within-Subjects Design | Explanation, Approaches, Examples

Community Blog

Keep up-to-date on postgraduate related issues with our quick reads written by students, postdocs, professors and industry leaders.

Types of Research – Explained with Examples

- By DiscoverPhDs

- October 2, 2020

Types of Research

Research is about using established methods to investigate a problem or question in detail with the aim of generating new knowledge about it.

It is a vital tool for scientific advancement because it allows researchers to prove or refute hypotheses based on clearly defined parameters, environments and assumptions. Due to this, it enables us to confidently contribute to knowledge as it allows research to be verified and replicated.

Knowing the types of research and what each of them focuses on will allow you to better plan your project, utilises the most appropriate methodologies and techniques and better communicate your findings to other researchers and supervisors.

Classification of Types of Research

There are various types of research that are classified according to their objective, depth of study, analysed data, time required to study the phenomenon and other factors. It’s important to note that a research project will not be limited to one type of research, but will likely use several.

According to its Purpose

Theoretical research.

Theoretical research, also referred to as pure or basic research, focuses on generating knowledge , regardless of its practical application. Here, data collection is used to generate new general concepts for a better understanding of a particular field or to answer a theoretical research question.

Results of this kind are usually oriented towards the formulation of theories and are usually based on documentary analysis, the development of mathematical formulas and the reflection of high-level researchers.

Applied Research

Here, the goal is to find strategies that can be used to address a specific research problem. Applied research draws on theory to generate practical scientific knowledge, and its use is very common in STEM fields such as engineering, computer science and medicine.

This type of research is subdivided into two types:

- Technological applied research : looks towards improving efficiency in a particular productive sector through the improvement of processes or machinery related to said productive processes.

- Scientific applied research : has predictive purposes. Through this type of research design, we can measure certain variables to predict behaviours useful to the goods and services sector, such as consumption patterns and viability of commercial projects.

According to your Depth of Scope

Exploratory research.

Exploratory research is used for the preliminary investigation of a subject that is not yet well understood or sufficiently researched. It serves to establish a frame of reference and a hypothesis from which an in-depth study can be developed that will enable conclusive results to be generated.

Because exploratory research is based on the study of little-studied phenomena, it relies less on theory and more on the collection of data to identify patterns that explain these phenomena.

Descriptive Research

The primary objective of descriptive research is to define the characteristics of a particular phenomenon without necessarily investigating the causes that produce it.

In this type of research, the researcher must take particular care not to intervene in the observed object or phenomenon, as its behaviour may change if an external factor is involved.

Explanatory Research

Explanatory research is the most common type of research method and is responsible for establishing cause-and-effect relationships that allow generalisations to be extended to similar realities. It is closely related to descriptive research, although it provides additional information about the observed object and its interactions with the environment.

Correlational Research

The purpose of this type of scientific research is to identify the relationship between two or more variables. A correlational study aims to determine whether a variable changes, how much the other elements of the observed system change.

According to the Type of Data Used

Qualitative research.

Qualitative methods are often used in the social sciences to collect, compare and interpret information, has a linguistic-semiotic basis and is used in techniques such as discourse analysis, interviews, surveys, records and participant observations.

In order to use statistical methods to validate their results, the observations collected must be evaluated numerically. Qualitative research, however, tends to be subjective, since not all data can be fully controlled. Therefore, this type of research design is better suited to extracting meaning from an event or phenomenon (the ‘why’) than its cause (the ‘how’).

Quantitative Research

Quantitative research study delves into a phenomena through quantitative data collection and using mathematical, statistical and computer-aided tools to measure them . This allows generalised conclusions to be projected over time.

According to the Degree of Manipulation of Variables

Experimental research.

It is about designing or replicating a phenomenon whose variables are manipulated under strictly controlled conditions in order to identify or discover its effect on another independent variable or object. The phenomenon to be studied is measured through study and control groups, and according to the guidelines of the scientific method.

Non-Experimental Research

Also known as an observational study, it focuses on the analysis of a phenomenon in its natural context. As such, the researcher does not intervene directly, but limits their involvement to measuring the variables required for the study. Due to its observational nature, it is often used in descriptive research.

Quasi-Experimental Research

It controls only some variables of the phenomenon under investigation and is therefore not entirely experimental. In this case, the study and the focus group cannot be randomly selected, but are chosen from existing groups or populations . This is to ensure the collected data is relevant and that the knowledge, perspectives and opinions of the population can be incorporated into the study.

According to the Type of Inference

Deductive investigation.

In this type of research, reality is explained by general laws that point to certain conclusions; conclusions are expected to be part of the premise of the research problem and considered correct if the premise is valid and the inductive method is applied correctly.

Inductive Research

In this type of research, knowledge is generated from an observation to achieve a generalisation. It is based on the collection of specific data to develop new theories.

Hypothetical-Deductive Investigation

It is based on observing reality to make a hypothesis, then use deduction to obtain a conclusion and finally verify or reject it through experience.

According to the Time in Which it is Carried Out

Longitudinal study (also referred to as diachronic research).

It is the monitoring of the same event, individual or group over a defined period of time. It aims to track changes in a number of variables and see how they evolve over time. It is often used in medical, psychological and social areas .

Cross-Sectional Study (also referred to as Synchronous Research)

Cross-sectional research design is used to observe phenomena, an individual or a group of research subjects at a given time.

According to The Sources of Information

Primary research.

This fundamental research type is defined by the fact that the data is collected directly from the source, that is, it consists of primary, first-hand information.

Secondary research

Unlike primary research, secondary research is developed with information from secondary sources, which are generally based on scientific literature and other documents compiled by another researcher.

According to How the Data is Obtained

Documentary (cabinet).

Documentary research, or secondary sources, is based on a systematic review of existing sources of information on a particular subject. This type of scientific research is commonly used when undertaking literature reviews or producing a case study.

Field research study involves the direct collection of information at the location where the observed phenomenon occurs.

From Laboratory

Laboratory research is carried out in a controlled environment in order to isolate a dependent variable and establish its relationship with other variables through scientific methods.

Mixed-Method: Documentary, Field and/or Laboratory

Mixed research methodologies combine results from both secondary (documentary) sources and primary sources through field or laboratory research.

If you’re about to sit your PhD viva, make sure you don’t miss out on these 5 great tips to help you prepare.

Multistage sampling is a more complex form of cluster sampling for obtaining sample populations. Learn their pros and cons and how to undertake them.

The purpose of research is to enhance society by advancing knowledge through developing scientific theories, concepts and ideas – find out more on what this involves.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

Browse PhDs Now

Stay up to date with current information being provided by the UK Government and Universities about the impact of the global pandemic on PhD research studies.

Learn 10 ways to impress a PhD supervisor for increasing your chances of securing a project, developing a great working relationship and more.

Clara is in the first year of her PhD at the University of Castilla-La Mancha in Spain. Her research is based around understanding the reactivity of peroxynitrite with organic compounds such as commonly used drugs, food preservatives, or components of atmospheric aerosols.

Gareth is getting ready for his PhD viva at Aberystwyth University and has been researching bacteria living inside coastal plants that can help other plants grow in salt contaminated soils.

Join Thousands of Students

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 6. The Methodology

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The methods section describes actions taken to investigate a research problem and the rationale for the application of specific procedures or techniques used to identify, select, process, and analyze information applied to understanding the problem, thereby, allowing the reader to critically evaluate a study’s overall validity and reliability. The methodology section of a research paper answers two main questions: How was the data collected or generated? And, how was it analyzed? The writing should be direct and precise and always written in the past tense.

Kallet, Richard H. "How to Write the Methods Section of a Research Paper." Respiratory Care 49 (October 2004): 1229-1232.

Importance of a Good Methodology Section

You must explain how you obtained and analyzed your results for the following reasons:

- Readers need to know how the data was obtained because the method you chose affects the results and, by extension, how you interpreted their significance in the discussion section of your paper.

- Methodology is crucial for any branch of scholarship because an unreliable method produces unreliable results and, as a consequence, undermines the value of your analysis of the findings.

- In most cases, there are a variety of different methods you can choose to investigate a research problem. The methodology section of your paper should clearly articulate the reasons why you have chosen a particular procedure or technique.

- The reader wants to know that the data was collected or generated in a way that is consistent with accepted practice in the field of study. For example, if you are using a multiple choice questionnaire, readers need to know that it offered your respondents a reasonable range of answers to choose from.

- The method must be appropriate to fulfilling the overall aims of the study. For example, you need to ensure that you have a large enough sample size to be able to generalize and make recommendations based upon the findings.

- The methodology should discuss the problems that were anticipated and the steps you took to prevent them from occurring. For any problems that do arise, you must describe the ways in which they were minimized or why these problems do not impact in any meaningful way your interpretation of the findings.

- In the social and behavioral sciences, it is important to always provide sufficient information to allow other researchers to adopt or replicate your methodology. This information is particularly important when a new method has been developed or an innovative use of an existing method is utilized.

Bem, Daryl J. Writing the Empirical Journal Article. Psychology Writing Center. University of Washington; Denscombe, Martyn. The Good Research Guide: For Small-Scale Social Research Projects . 5th edition. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press, 2014; Lunenburg, Frederick C. Writing a Successful Thesis or Dissertation: Tips and Strategies for Students in the Social and Behavioral Sciences . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 2008.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Groups of Research Methods

There are two main groups of research methods in the social sciences:

- The e mpirical-analytical group approaches the study of social sciences in a similar manner that researchers study the natural sciences . This type of research focuses on objective knowledge, research questions that can be answered yes or no, and operational definitions of variables to be measured. The empirical-analytical group employs deductive reasoning that uses existing theory as a foundation for formulating hypotheses that need to be tested. This approach is focused on explanation.

- The i nterpretative group of methods is focused on understanding phenomenon in a comprehensive, holistic way . Interpretive methods focus on analytically disclosing the meaning-making practices of human subjects [the why, how, or by what means people do what they do], while showing how those practices arrange so that it can be used to generate observable outcomes. Interpretive methods allow you to recognize your connection to the phenomena under investigation. However, the interpretative group requires careful examination of variables because it focuses more on subjective knowledge.

II. Content

The introduction to your methodology section should begin by restating the research problem and underlying assumptions underpinning your study. This is followed by situating the methods you used to gather, analyze, and process information within the overall “tradition” of your field of study and within the particular research design you have chosen to study the problem. If the method you choose lies outside of the tradition of your field [i.e., your review of the literature demonstrates that the method is not commonly used], provide a justification for how your choice of methods specifically addresses the research problem in ways that have not been utilized in prior studies.

The remainder of your methodology section should describe the following:

- Decisions made in selecting the data you have analyzed or, in the case of qualitative research, the subjects and research setting you have examined,

- Tools and methods used to identify and collect information, and how you identified relevant variables,

- The ways in which you processed the data and the procedures you used to analyze that data, and

- The specific research tools or strategies that you utilized to study the underlying hypothesis and research questions.

In addition, an effectively written methodology section should:

- Introduce the overall methodological approach for investigating your research problem . Is your study qualitative or quantitative or a combination of both (mixed method)? Are you going to take a special approach, such as action research, or a more neutral stance?

- Indicate how the approach fits the overall research design . Your methods for gathering data should have a clear connection to your research problem. In other words, make sure that your methods will actually address the problem. One of the most common deficiencies found in research papers is that the proposed methodology is not suitable to achieving the stated objective of your paper.

- Describe the specific methods of data collection you are going to use , such as, surveys, interviews, questionnaires, observation, archival research. If you are analyzing existing data, such as a data set or archival documents, describe how it was originally created or gathered and by whom. Also be sure to explain how older data is still relevant to investigating the current research problem.

- Explain how you intend to analyze your results . Will you use statistical analysis? Will you use specific theoretical perspectives to help you analyze a text or explain observed behaviors? Describe how you plan to obtain an accurate assessment of relationships, patterns, trends, distributions, and possible contradictions found in the data.