- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

- The visual arts

- Common traditions

- Social conditions

- Concepts of music

- Theoretical systems

- Musical traits common to East Asian cultures

- What is Japanese art?

- What is Japanese art known for?

- How does religion influence Japanese art?

East Asian arts

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art - Painting Formats in East Asian Art

- Table Of Contents

East Asian arts , the visual arts, performing arts, and music of China , Korea ( North Korea and South Korea ), and Japan . (The literature of this region is treated in separate articles on Chinese literature , Korean literature , and Japanese literature .) Some studies of East Asia also include the cultures of the Indochinese peninsula and adjoining islands, as well as Mongolia to the north. The logic of this occasional inclusion is based on a strict geographic definition as well as a recognition of common bonds forged through the acceptance of Buddhism by many of these cultures. China, Korea, and Japan, however, have been uniquely linked for several millennia by a common written language and by broad cultural and political connections that have ranged in spirit from the uncritically adorational to the contentious .

A broad introduction to East Asian arts—their common characteristics, traditions, and values—follows. More detailed and focused treatment is presented elsewhere. For detailed coverage of the visual art of East Asia, see Chinese art; Chinese bronzes ; Chinese calligraphy ; Chinese jade ; Chinese lacquerwork ; Chinese painting ; Chinese pottery ; Japanese art; Japanese calligraphy ; Japanese pottery ; Korean art ; Korean calligraphy ; and Korean pottery . For detailed coverage of the architecture of East Asia, see Chinese architecture ; Japanese architecture ; and Korean architecture . For detailed coverage of the music of East Asia, see Chinese music ; Japanese music ; and Korean music . Likewise, for detailed coverage of the dance and theatre of East Asia, see Chinese performing arts ; Japanese performing arts ; and Korean performing arts .

Publications

Essays on East Asian Art in Honor of Professor Wen C. Fong

Wen C. Fong established America’s first program in East Asian art history at Princeton University, where he taught Chinese art from 1954 to 1999. During this time, he supervised more than thirty PhDs, most of whom have gone on to hold professorships or museum positions throughout the United States, East Asia, and Europe. This two-volume book honors Professor Fong’s extraordinary half-century career at Princeton and The Metropolitan Museum of Art by gathering thirty-nine essays on Chinese, Japanese, and Korean art history, written by his students and by some of his lifelong colleagues in this field of study. These full-length essays address a wide range of subjects, building bridges in many directions, from early jades and bronzes through traditional painting and prints, to photography, cinema, and modern museum practice. The diversity, depth, and originality of these essays make this work a monumental contribution to the study of the arts of East Asia. The book includes an interview with Professor Fong, conducted by Jerome Silbergeld, and a bibliography of Fong’s work.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Southeast Asian Art's Contemporary Turn: the role of siting, audience, and performativity STEALING PUBLIC SPACE

2020, The Substation, Singapore

On Southeast Asian art's modern-to-contemporary shift: argues a distinctive Southeast Asian contemporary art methodology whereby public space and intangibles (money, national anthems, history, so on) are co-opted to engage audiences on social issues. Analysing seminal Southeast art from the 1970s onwards, author shows how these strategies emerged and persisted from contextual necessity, and are fundamental to Southeast Asian art's transition to contemporary modes.

Related Papers

Francis Maravillas , Associate Professor Michelle Antoinette

Co-authored with Michelle Antoinette This essay positions the rapidly changing field of contemporary art in Southeast Asia, and the shifting structure, dynamics and influence of the region's contemporary ‘art worlds' and ‘art publics’. It seeks to open up new horizons and frameworks for understanding the particular character of art worlds and art publics in Southeast Asia by being especially attuned to the local contexts and histories of contemporary art in the region and their particular ecologies. We contend that while contemporary art worlds and art publics in Southeast Asia might bear similar structures and dynamics to contemporary art worlds and publics elsewhere, they are nevertheless indicative of culturally specific and localised developments. Indeed, the various past and present practices and mediation of art and its publics in the region are suggestive of the ways in which art worlds take on nuanced character and meaning in Southeast Asia, are diversely configured and imagined, and are multiply located and complexly interconnected. The worldliness of these practices are, moreover, indicative of the ways in which Southeast Asian artists continue to respond to the exigencies of the everyday and the political economy of survival in an increasingly challenging world.

Obieg quarterly, no. 2/ 2016, Warsaw

Southeast Asian artists, from the 1970s onwards, developed conceptual strategies that, combined with siting and physical involvement, engaged viewers in critical conversations about society and politics. Installations and performances, designed for collective zones, were often structured in a way reminiscent of games. This paper argues the linkage between methodologies of play, critical interrogations, and conceptual strategies as characterising trait of Southeast Asian contemporary art.

Art Journal

Roger Nelson

Published in "Art Journal" 81:4 (2022): 146-149. Review of Pamela N. Corey, "The City in Time: Contemporary Art and Urban Form in Vietnam and Cambodia" (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2021) and Viêt Lê, "Return Engagements: Contemporary Art’s Traumas of Modernity and History in Sài Gòn and Phnom Penh (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021).

Bharti Lalwani

SUNSHOWER Exhibition catalogue: SUNSHOWER – Contemporary Art from Southeast Asia 1980s to Now, Date of Issue: August 9, 2017 >>Exhibition-catalogues are significant. However big the show, once taken down, it is primarily the catalogue, that speaks for the exhibition-artworks’ relationship with each other and the larger field. When the field is young and undecided, the catalogue, embodying the curator’s vision and position, matters more. This critic’s own knowledge of Southeast Asian art is grounded in the scholarship built through multiple-essay catalogues of historically relevant shows. A number of these were produced by Japan’s institutions, particularly with the opening of the Fukuoka Art Museum in 1979. Take for instance the principal text from the catalogue of one such regional exhibition, ‘Art in Southeast Asia 1997: Glimpses into the Future’, produced by The Japan Foundation Asia Centre in ‘97. Curator Junichi Shioda’s essay ‘Glimpses into the Future of Southeast Asian Art: A Vision of what Art should be’, constructed and cross-examined the idea of a regional canon, independent from Euramerican modernism, through the socially-rooted practices of artists from five Southeast Asian countries. Two other academic essays in this exhibition-catalogue further provided analyses of art in Southeast Asia and contemporary art in Indonesia. Around the same time, a similarly vital exhibition ‘Contemporary Art in Asia: Traditions/Tensions’ was curated by Thai scholar Apinan Poshyananda. This exhibition’s catalogue included seven essays that built the discourse around the politically charged practices of various Southeast Asian artists among others from Asia. Such exhibition-catalogues sought intellectual contributions from field-scholars who connect socio-economic complexities, and ground artistic practices in their respective historical, cultural and political contexts. Such catalogue-essays, written two decades ago or today, are important to establishing the canon around Southeast Asian art because scholarly analyses of exhibition artworks, and their comparison with other pieces, permit the discerning of larger currents and parallels that give shape to the field. That artists from Southeast Asia have been potent voices for social change and reformation is established through scholars’ analyses of artworks presented in writing for exhibition-catalogues, past and present.<<

Eva Bentcheva

The international symposium Pathways of Performativity in Contemporary Southeast Asian Art casts a spotlight on the fascinating histories of performance practices which speak to the postcolonial, Cold War and politico-economic forces that have shaped Southeast Asia after the Second World War. It brings together renowned scholars and curators from the disciplines of art history, film and music studies, whose work explores the central role of performance in bridging the visual arts, theatre, dance, music and political activism in the region from the 1960s to the present. The conference aims to deepen historical awareness of the long-standing performance-based practices in Southeast Asia, while opening up dialogues around diasporic and migrant entanglements. It explores the relationship between intermediality and historical developments, especially performative practices that have been impacted by advances in technology. This discussion takes on more urgent resonances as it is framed in relation to the notions of 'identity' and 'activism' within the region in light of an increasing policing of the public media platforms. Projecting these discussions into the future, the conference concludes by exploring the intersection of performance and archiving, questioning the possibilities yielded through historicisation and research. The symposium is accompanied by the launch of the exhibition Archives in Residence: Southeast Asia Performance Collection, curated by Eva Bentcheva, Annie Jael Kwan and Damian Lentini, as part of the series 'Archives in Residence' in Haus der Kunst's Archive Gallery. It presents video documentation from the 'Southeast Asia Performance Collection', an expansive research project and digital archive compiled by an international team of researchers and curators in the UK and Asia between 2015 and 2017. This archive contains documentation of performance-based works such as live art, urban and social interventions by over fifty artists from across Southeast Asia and its diasporas. The exhibition presents a selection of these materials for the first time in Germany, and explores the relationship between performativity and digital exchanges, networks and virtual preservation across Southeast Asia, with a particular focus on Cambodia, Vietnam, Singapore and the Philippines. Bringing the ideas behind the symposium and exhibition to life will also be a curated program of live performances

Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 50(4)

Maurizio Peleggi

Southeast Asia Performance Collection: Archive as Resistance and Network Building

Yu Jin Seng

Pathways of Performativity in Contemporary Art of Southeast Asia

Eva Bentcheva , Annie J Kwan , Roger Nelson

Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia Volume 6, Number 1, March 2022

Co-opting the public, enticing them to confront questions of citizenship, to consider individual responsibilities and their consequences for the collective, is one of the tactics that were extensively explored in three recent landmark exhibitions on Southeast Asian contemporary art.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

The Third Avant-garde: contemporary art from Southeast Asia recalling tradition

Leonor Veiga

Southeast of Now: Directions in Contemporary and Modern Art in Asia

Southeast of Now: Directions in Modern and Contemporary Art

Australian National University, Intersections

Wacana, Journal of the Humanities of Indonesia

Alia Swastika

Afterall: A Journal of Art, Context and Enquiry

kathleen ditzig

Shaping the History of Art in Southeast Asia

Asian Journal of German and European Studies

Dirk Michel Schertges

ISEA (International Symposium of Electronic Art)

Alessandra Campoli

C. J. W.-L. Wee

ART IN AMERICA

Gregory Galligan, PhD

Translation Quarterly

Loredana Pazzini - Paracciani

Symposium: “Asian Contemporary Art Reconsidered"

Asian Culture and History

thasnai sethaseree

Art Journal 79:1

Pamela N Corey

suedostasien.net

Weng Choy Lee , Ray Langenbach

Public Art Dialogue

Associate Professor Michelle Antoinette

Eileen Ramirez

Brian Curtin

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Art Journal Open

Art History and the Modern in Southeast Asia

From art journal 79, no. 1 (spring 2020).

T. K. Sabapathy. Writing the Modern: Selected Texts on Art and Art History in Singapore, Malaysia, and Southeast Asia, 1973–2015 . Ed. Ahmad Mashadi, Susie Lingham, Peter Schoppert, and Joyce Toh. Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 2018. 448 pp.; 70 color ills., 5 b/w. $48

A serious volume testifying to the contributions of T. K. Sabapathy to the field of modern and contemporary Southeast Asian art history seems long overdue, and in this regard, this anthology published by the Singapore Art Museum in 2018 is a welcome development. For the first time, the Singaporean art historian’s prolific body of writing, extracted from such sources as newspaper columns, exhibition catalogs, artist monographs, and symposium proceedings, is presented in a formidable more-than-four-hundred-page compendium of fifty-seven selected texts. The editorial team comprises Ahmad Mashadi (director of the National University of Singapore Museum), Susie Lingham (former director of the Singapore Art Museum), Peter Schoppert (director of National University of Singapore Press), and Joyce Toh (senior curator at the Singapore Art Museum).

The book surveys the development of Sabapathy’s grappling with several interrelated inquiries as they have come to shape studies of modern and contemporary art in Southeast Asia over nearly half a century. Interrogated as fields, in terms of Sabapathy’s concerns with the nature of their discursive formation and utility, these frameworks may be construed as art history, the modern (and the contemporary), and regionalism. How these topics have been imaginatively, even forensically, explored in Sabapathy’s attempt arguably to define a field of study—concomitant with his wariness of definition as an act of prescription—is unparalleled in terms of a scholarly perspective shaped from Singaporean, Malaysian, American, and British institutions. Enriching this body of work is a historical outlook shaped by memories of 1950s and 1960s postcolonial fervor in former British Malaya and the respective national projects of newly split Singapore and Malaysia, followed by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)’s spearheading regional artistic affairs in the 1980s and 1990s. As much as Sabapathy wrote about art and artists to create the building blocks of an art history, he never ceased to rigorously tackle art’s frames of representation, from the written text to the gallery space to the exhibition symposium, highly attentive to his own role in interpellating readers from within these constituent elements at every turn.

Thiagarajan Kanaga Sabapathy, more commonly referred to as T. K. Sabapathy, was born in the British Straits Settlements and began his study of art history as an undergraduate history major at then Singapore-based University of Malaya in 1958, a year after the territories proclaimed independence as the Federation of Malaya. He studied art history as an elective, as no major provision was available, a situation that he laments has not changed. He found the teachings of his art history lecturer, esteemed scholar of Chinese art history Michael Sullivan, deeply influential, and subsequently pursued a master’s degree in the history of art at the University of California, Berkeley. He departed for California in 1962, making the journey by sea. At Berkeley he received training in the classical traditions of art and art historical method, both European and Asian: “The grandeur of history of art as an academic discipline was revealed to me when I commenced studies in Berkeley in the fall of 1962. The propelling scheme was the survey.” 1 However, to gain specialist knowledge in Southeast Asian art, he continued his studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London in the later 1960s, where he undertook research into premodern narrative representations. He continued his studies supported by a research fellowship over two years, while supplementing his income through teaching. 2 His focus was the classical, and the means of interpretation primarily iconological; when he encountered modern art through the divergent approaches of Philip Rawson and Claire Holt, he recounts feeling unequipped, and that “the modern was strange.” 3

With the establishment of an art history course (focusing on modern Malaysian art) at the newly launched Universiti Sains Malaysia in 1970, Sabapathy returned to Southeast Asia to take up a post as a lecturer. He undertook the significant challenge of creating a curriculum and body of teaching materials from scratch, from foraging for teachable writings to photographing artworks to create lecture slides. As part of this endeavor, he frequently collaborated with celebrated Malaysian artist and critic Redza Piyadasa: “Our early writings on art and artists in Malaysia were collected and published in 1982. In them are also nuclear attempts at ascertaining the modern in this region, critically and historically. Hence I began involvement with the modern and have largely stayed with it, since I could no longer traverse parallel worlds. Indeed, I had to turn away from one of them effectively, returning intermittently.” 4 Sabapathy returned to Singapore in 1980, where he began contributing to the Straits Times until he ceased writing art criticism—in that form—in 1993. In 1981 he was appointed lecturer in the history of art in the department of architecture at the National University of Singapore, where he has continued to teach to this day.

As one of the editors, Peter Schoppert, notes, “The goal in republishing a set of Sabapathy’s writings in an anthology and mapping them against different themes, and against a timeline of changing art practices and institutions, is to heed Sabapathy’s call to begin the hard work required to build the foundation for a more historically aware and regionally grounded practice of art writing” (225). Writing the Modern is organized into four sections, following opening materials that include a foreword, an editors’ preface, short editorial notes by Chu Chu Yuan, and an introduction authored by Ahmad Mashadi. Each of the four sections is introduced by a short essay that provides the editorial rationale for the selection of texts. Within each section, the texts are organized chronologically, from earliest to most recent, to give a sense of Sabapathy’s development of a methodological inclination over time. The book concludes with a timeline of all his writings. Unfortunately, images are scarce and are reproduced at an almost thumbnail scale, which leaves the reader feeling somewhat bereft in the face of Sabapathy’s committed formalist scrutiny of the artwork.

The first section, “The Southeast Asian Artist in Relation to Art History,” with an editorial overview by Joyce Toh, features Sabapathy’s writings about individual artists, extracted from monographs, exhibition reviews, newspaper columns (the “Art and Artists” feature in the Straits Times ), and catalog essays. The first essay—the 1978 “Towards a Mystical Reality” from his monograph on Piyadasa—is of major significance for his theorizing of what many consider to be an example of the earliest conceptual practices in Southeast Asia. Other artists covered include those affiliated with the Nanyang artists, such as Lim Hak Tai, Cheong Soo Pieng, and Georgette Chen, and those celebrated as heralding the contemporary, including Tang Da Wu and Cheo Chai-Hiang. The span is wide, in terms of both the period covered and the spectrum of practices that are articulated as illustrating the modern or the contemporary. This is one challenge to the volume’s coherence in its framing of the modern: many of Sabapathy’s essays articulate the contemporary, and the conditions for such a distinction from—and its glossing with—the modern are not clearly addressed by the editors within the book’s purview.

The first section does illuminate how “Sabapathy’s interest in biography as a means and method of writing art history arches back to a practice with centuries-old historical roots, in both Western and Asian art“ (30), demonstrating his sourcing of familiar and unfamiliar methods to navigate what was a new field of art historical representation not only in Southeast Asia. 5 For Sabapathy, “It was a way of writing [that was] unlike the historical traditions of art in which I was schooled—to write on the modern was also to write on the artist” (31). Important topics introduced in this section, and recurring throughout the book, include the figure of Malaya in the artistic imagination, the centrality of art in the cultural debates in the 1950s and 1960s in the British postcolonies, and the context of Singapore’s divorce from historical traditions to realize its ideology of “installing the modern/new at the very centre of its strategy” (110). Witnessing such a claim to tabula rasa would appear to have fueled Sabapathy’s own commitment to historicization, and to connect to premodern models to conjecture on regional hypotheses in the present.

The second section, “A Mind for Method, and an Eye for Medium, Materiality, and Form,” with an editorial overview by Susie Lingham, highlights Sabapathy’s sensitivity to artistic process and the problem of medium. These issues are relayed through writings on artworks grounded in such mediums as drawing, sculpture, ceramics, and installation, which further illustrate aspects of artistic formation responsive to site, mobilities, personal and professional relationships, institutions, and alternative forms of education. One example is an analysis of new approaches to artmaking by Sulaiman Esa and Piyadasa, whose conceptual orientations were significantly shaped by their studies in Britain when major shifts in artistic pedagogy were taking place. 6 While some of the emphases in this section would appear to repeat those of the first, a distinguishing feature is Sabapathy’s consideration of the vantage points offered through medium-based discourses attached to both classical art and modernism: “I have leaned towards texts on sculpture in the Anglo-Saxon critical tradition that open up paths along which one can traverse in order to approach sculptural practices and ideals here and offer explanations for them” (194). This strategy is reiterated as a first point of recourse in what he describes as an ahistorical state of artistic discourse in both Singapore and Malaysia: “If one of the features identifying the modern artist is in the adoption of a critical and self-regulating stance towards traditions as such, then the modern artist in Malaysia must also embrace the tradition of the new as it has been personified in this country. Ignorance of it may well produce a context that is sterile” (171). The third section, “Art Institutions and the Exhibition,” with an editorial overview by Peter Schoppert, focuses on Sapapathy’s writing for and about exhibitions and exhibitionmaking institutions. A salient feature within this group is Sabapathy’s trenchant commitment to wide-reaching politico-cultural critique. In response to the rise of region-facing projects vis-à-vis the ASEAN cultural agenda, Sabapathy challenged the hollowness of such endeavors as diplomatic lip service:

Exhibitions are acts of avowal and engagement, and the curator assumes a formative role in these processes. In this regard, the ASEAN exhibition has not fulfilled its role. There are three objectives underpinning this enterprise. I have mentioned one—consciousness. The other two are the provision of a base for comparative study and a glimpse of cultures of the countries. Comparative bases for study have to be structured and continually tested. Glimpses need positions of advantage. These are means by which what has been produced is rendered intelligible, sensible. . . . So far, curators in the ASEAN shows have been coy. (237)

His desire to see more substantial critical thinking on regional representation of and from within Southeast Asia is strongly emphasized throughout this and the following section. However, of importance here is his elaboration of the exhibition as a crucial vehicle through which regional propositions can be tested. Other essays demonstrate Sabapathy’s holding of national institutions to account for the lagging development of art history as a public resource: “[The National Museum Art Gallery] cannot avoid this responsibility. It has to purchase such works and not depend on donations by artists. Only then can it begin to shape the history of art in Singapore, and thereby fulfil its role” (242).

The fourth section, “Regionalist Perspectives in Southeast Asian Art,” with an editorial overview by Ahmad Mashadi, draws out an enduring preoccupation in Sabapathy’s writing, but because the question of region appears throughout the book, thematic isolation feels somewhat unnecessary. Sabapathy frequently invited regional hypotheses through historiographical analyses, drawing on the works of celebrated scholars, such as Georges Cœdès and Ananda Coomaraswamy, and art, for instance by returning to the Nanyang and regionality within the nation. Mashadi attributes the how and why of this preoccupation to Sabapathy’s own itinerant academic formation and to his scrutiny of art’s alignment with national horizons: “Sabapathy distinguishes modern art history from the national, reminding his readers that discernable and coherent developments started well before Malaysia’s independence in 1957” (333). Mashadi refreshingly situates Sabapathy among a rising community of art historians in 1990s Southeast Asia producing what today are considered foundational studies, yet the question of cross-border research remained elusive for Sabapathy:

How do we perceive the region today, and how do we perceive it art historically? Or is the quest for a regionalist perspective a futile, self-defeating quest? I ask this question because there is a pronounced tendency for art writers/scholars in Southeast Asia to focus on the constituent parts of Southeast Asia rather than to develop a perception of the region as a whole and as a suitable object of study. (376)

In a parallel deconstructive endeavor to that undertaken by scholars rethinking “the West” or “Europe,” Sabapathy similarly analogizes Europe as a regional construct:

As an issue, region and regionness have historical and current pertinence for Europeans. Indeed, it reaches into and shapes mythological domains. . . . The euro as currency presupposes that there are capacities and symbolic means for narrating Europe as an integrated region. It marks an ascendency of region-ness over nation-states as nominal constructions. (393) 7

This is a unique volume in that there are no comparable anthologies by a single author devoted to writing about modern and contemporary Southeast Asian art as a field of study. 8 The editors are to be seriously commended for the task of compiling such a wealth of materials into an invaluable resource for researchers of Southeast Asian art. To some extent, an engagement with Sabapathy’s writings as categorized through the themes selected here enables the parsing of certain discursive priorities and the ways in which they beckoned deeper engagement from what we might assume to be a regional readership at the time of their production. However, Sabapathy’s writings were often prescient queries into disciplinary and interdisciplinary problems beyond the region, such as those that lie at the intersection of art history and the decolonial project. As such, it is tempting to imagine what other forms the anthology might have taken to more closely align with Sabapathy’s intellectual ambitions.

One avenue might have been through a retooling of the editorial themes. Despite the editors’ respective efforts to distinctively foreground the overarching tenor of each section, the effectiveness of this mode of organization is uncertain. In Mashadi’s introduction to the volume, he notes that

some of these texts are iterations that have evolved over time, where passages may reappear, albeit somewhat repurposed, contextualized within and in relation to specific circumstances of their delivery and intentions. As a collection of Sabapathy’s writings rationalized along key subjects or interests, this publication also hopes to construct grounds on which the texts may converse with and be regarded in relation to other texts written variously by other writers and historians, including his contemporaries. (19)

The breadth of writings compiled here is both an asset and a challenge. Those less familiar with Sabapathy’s work may have difficulty mining the book for conceptual threads given the extent to which the abovementioned themes recur across so much of his writing and in diverse forms (e.g., from newspaper columns to lengthy monograph essays). The extensive overlaps across the sections undermine the coherence of separate themes, as Sabapathy’s writings wove together compelling strains of inquiry that should be seen as the warp and weft of the same fabric of discourse rather than thematically segregated.

A more challenging alternative—or perhaps a future prospect—may have been to focus on a more tightly curated selection of more substantial texts so that each could evince a more unique identity, a legibly individualized offering to the field. An example would be the omitted 1996 essay “Developing Regionalist Perspectives in Southeast Asian Art Historiography,” published in the catalog for the second Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art. The essay consolidates sections of several texts included in the volume, and demonstrates Sabapathy’s finely honed thinking on historiography in critical response to a perceived nativist turn in the theorizing of the modern within Asia. It furthermore stands out as an excellent resource for teaching. The significance of the essay’s contribution, and that of others, could be explored through more specific editorial annotation or through partnered responses by interlocutors in the field of Southeast Asian art history and beyond—for example, an art historian of China (perhaps another former student of Michael Sullivan) reflecting on the Nanyang within Chinese art historiography, or another scholar preoccupied with the question of regionalism in Asian art history, and so on. Perhaps such a project could be the next step in furthering Sabapathy’s historiographical pursuits while constructing the grounds for continued conversation.

Pamela N. Corey is an assistant professor of Southeast Asian art at SOAS University of London. She is currently completing a book manuscript titled “The City in Time: Contemporary Art and Urban Form in Vietnam and Cambodia .”

- T. K. Sabapathy, Road to Nowhere: The Quick Rise and the Long Fall of Art History in Singapore (Singapore: National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, 2010), 18. ↩

- He also taught Asian art at Farnham School of Art, Surrey, in 1966—the first such appointment in the British school and college system—and at St. Martins School of Art in 1969–70. ↩

- Sabapathy, Road to Nowhere , 26. The books he encountered are Philip Rawson, The Art of Southeast Asia: Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand, Laos, Burma, Java, Bali (1967; repr., London: Thames and Hudson, 2002); and Claire Holt, Art in Indonesia: Continuities and Change (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1967). ↩

- Sabapathy, Road to Nowhere , 32. ↩

- See, for example, Richard Meyer, What Was Contemporary Art? (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013). ↩

- See Thierry de Duve, “When Form Has Become Attitude and Beyond,” in Theory in Contemporary Art since 1985 , ed. Zoya Kocur and Simon Leung (Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 2013), 21–33. ↩

- Such works on Europe include Dipesh Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000); and Iftikhar Dadi and Salah Hassan, eds., Unpacking Europe: Towards a Critical Reading (Rotterdam, the Netherlands: Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, 2001). ↩

- Comparable figures include Australia-based art historian John Clark, renowned for establishing a formative comparative approach to modern art in Asia, and Stanley J. O’Connor, the first professor of Southeast Asian art history appointed at a university in the United States, but neither wrote exclusively on modern and contemporary Southeast Asian art, nor have similar anthologies of their work been published. ↩

Publications of the Tang Center for East Asian Art, Princeton University 14

Books in this series present new research and histories on works of art and material culture from across East Asia, including China, Japan, and Korea, and ranging from the ancient period to today.

A beautifully illustrated, interdisciplinary look at the ceremonies and protocols of the dynastic court of Joseon Korea

Available in a limited print run of 1,000 sets—the stunning nine-volume presentation of the incredible Buddhist caves at Dunhuang in northwestern China

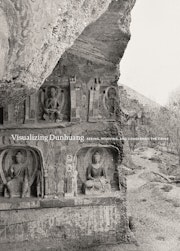

A beautifully illustrated study of the caves at Dunhuang, exploring how this important Buddhist site has been visualized from its creation to today

An in-depth look at the dynamic cultural world of tea in Japan during its formative period

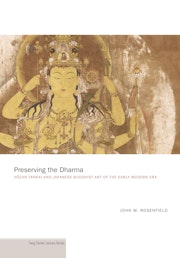

In this beautifully illustrated book, eminent art historian John Rosenfield explores the life and art of the Japanese Buddhist monk Hozan Tankai (1629–1716). Through a close examination of sculptures, paintings, ritual implements, and...

This richly illustrated book provides an anthology and summation of the work of one of the world's leading historians of Chinese painting and calligraphy. Wen Fong helped create the field of East Asian art history during a distinguished...

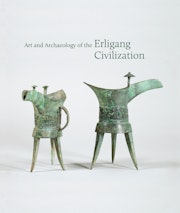

Named after an archaeological site discovered in 1951 in Zhengzhou, China, the Erligang civilization arose in the Yellow River valley around the middle of the second millennium BCE. Shortly thereafter, its distinctive elite material...

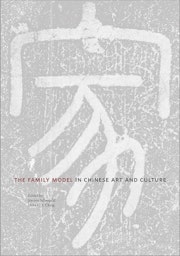

The family model has been central to patterns of social organization and cultural articulation throughout Chinese history, influencing all facets of the content and style of Chinese art. With contributors drawn from the disciplines of...

Yoshiaki Shimizu, one of the foremost scholars of Japanese art history, taught at Princeton University for more than twenty-five years, during which time he trained many students who have become respected professors and museum...

When is a landscape more than a landscape? This is a richly illustrated study of an important genre of Ming-dynasty Chinese painting in which landscapes are actually disguised portraits that celebrate an individual and his achievements...

Wen C. Fong established America's first program in East Asian art history at Princeton University, where he taught Chinese art from 1954 to 1999. During this time, he supervised more than thirty PhD students, most of whom have gone on...

What does it mean to say that some of the best Chinese contemporary art is made in America, by Americans? Through words and images, this book challenges the artificial and narrowly conceived definitions of Chinese contemporary art that...

The art world is currently enthralled with contemporary Chinese art. This thoughtful book argues, however, that American audiences have been exposed only to a narrow range of what is available—with the majority of attention having...

The “Wu Family Shrines” pictorial carvings from Han dynasty China (206 BCE–220 CE) are among the earliest works of Chinese art examined in an international arena. Since the eleventh century, the carvings have been identified by...

Stay connected for new books and special offers. Subscribe to receive a welcome discount for your next order.

Buy a gift card for the book lover in your life and let them choose their next great read.

- ebook & Audiobook Cart

- AsianStudies.org

- Annual Conference

- EAA Articles

- 2025 Annual Conference March 13-16, 2025

- AAS Community Forum Log In and Participate

Education About Asia: Online Archives

Ap art history and chinese art.

Editor’s Note: Images featured in this essay are similar to AP Art History curriculum images which could not be republished due to permissions issues. A link to these AP images are included in each entry.

The AP art history curriculum identifies 250 works students are required to know, spanning 20,000 years of history and cultures across the globe. The list includes thirty works of Asian art.

I teach in a rural fringe district and am committed to giving my students “equal access” to non-Western artistic traditions, and have taken several courses with NCTA, including the 2011 China study tour. My study tour began with Shanghai at night (with its river of lights), the gardens at Hangzhou, Chengdu, the Yellow Mountains, the ancient capital at Xi’an, and the museums and the contemporary scene in Beijing. In the beautiful national museums and historical spots, I was moved as I came face to face with six of the required Chinese works in the AP art history curriculum. My observation is that the College Board (and NCTA) chose these works with care to provide a single masterpiece from each of the significant historical periods, representing most major styles and media. So my understanding of the AP curriculum is that it takes us sequentially through historical periods, but allows us to experience a different medium in each. These do not provide a complete picture of Chinese art, but they are representative.

There are no significant opportunities for my students to encounter Chinese or other examples of Asian art. However, my students are open, curious, and hungry to understand. When facing Chinese art, they seem first drawn to structures of meaning that appear at first unfamiliar. I encourage this opening. The earliest artifact from China is the jade Cong from the Neolithic Liangzhu culture. The Cong is highly abstract, with a circle inside a square. Terra Cotta Warriors from the Qin dynasty situates each component in highly structured political, economic, artistic, and military relationships.

We try to understand aspects of structure, such as Dao, connecting one with na ture, as evident in later landscape paintings of mountains, trees, and rivers; or Confucian ethical narratives for order, as apparent in the scroll paintings with people, leaders, and ways of life. Having opened the door through curious exploration of shifts in cosmic and religious meaning, materials, methods, and visual identifiers become fundamental to the real understanding of art history for high school students. We try to understand how the Neolithic artist imprinted the jade with subtle meaning using the simplest tools, string, and sand to create stylized facial details on each corner. We reflect on casting methods for large sculptures. We research traditional ink painting on paper or silk, traded and reworked between China and Japan. We find images of mudras (hand positions found on Buddha) on Christian iconography gathered from the Silk Road. Prophets such as Buddha remind one to pray and be mindful and peaceful; ancestor worship places the individual in continuity with heaven and earth. My students and I make a pact to tread lightly with gentle hearts open to listening, research, and understanding another, and with the utmost respect of cultural nuances that are new-and-not within their experiences. I arrange field trips to the Metropolitan Museum of Art (hereafter “the Met”) in New York City. Firsthand experiences in front of authentic artwork are crucial to learning and understanding art history. With patient meditation on both abstract and concrete aspects of each object, the world slowly opens up to them.

The students create a journal/sketchbook capturing a visual understanding of the following works as we learn about the five largest religions across time, digital notecards, actual index cards with information and images, or essays based on past AP art history questions from previous exams. The students are offered participation grades for critical issues and answers to peer questions.

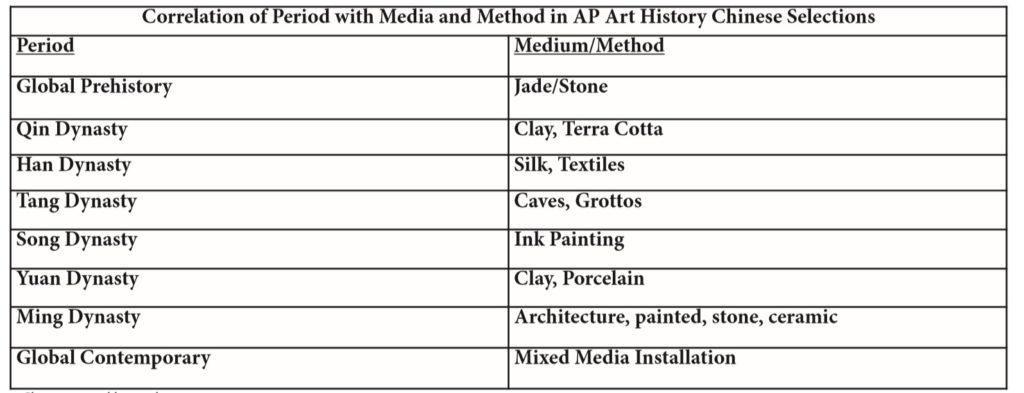

In the essay that follows, I will offer brief observations on the period and medium of each object to introduce what I see as the structure of the AP selection, and end with ideas for reading the interplay with tradition in the works of contemporary global artists. The chart on page ten is a specific organizational guide for Asia art image included in the essay.

AP Art History Image #7. Similar to Jade Cong. Liangzhu, China. Prehistoric stone

Image: Tube (cong) with masks Google Arts and Culture https://tinyurl.com/yyv6r6dt

Original College Board image: https://tinyurl.com/y29yy5r4

Global Prehistoric: Jade cong . This semiprecious stone, with a circle in the center representing the heavens and sky, has squared edges that represent earth; the four corners of the world on the cylinder convey possible spiritual aspects of heaven and earth as the earliest evidence of duality. The jade was carved using string, sand, and primitive tools, yet has excellent facial details on each corner. Neolithic period anthropomorphic works feature art that memorializes those of importance in the Liangzhu culture. Carved and uncarved stone provide understanding to students, as they convey an understanding of the difficult and time-consuming process of carving. Ask students in-depth questions. Why was this person selected to receive this object? What is the significance of the patterns in connection with your understanding of spirituality?

AP Art History Image #193. Terra cotta warriors of the first Qin emperor. Qin Dynasty. Terra Cotta clay.

Image: Terra cotta army, pit no. 1, mausoleum complex of Qin Shihuangdi (d. 210 B.C.), Lintong (Xi’an), Shaanxi Province, China. Qin dynasty (221–206 B.C.). Photo by Maros Mraz, 2007. Photo via Wikimedia Commons Available at the Metropolitan Museum of Art site: https://tinyurl.com/y4khwkqq

Original College Board image: https://tinyurl.com/yygwaj9q

Qin dynasty: Terra cotta clay. Statues of terra cotta warriors represent the highly structured political, economic, artistic, and militaristic Qin period. The burial tomb of the first Qin emperor is filled with thousands of clay soldiers and horses. The warriors are fully painted and secured with bronze weapons and chariots. Offering clay and examples of press mold objects, as well as souvenir replicas that I picked up in Xi’an, China, helps students understand the process of clay mold design and making. Given that some students have not had firsthand experiences with East Asian art or museums, artifact samples are vital to understanding sculpture. Watching documentaries on Terra cotta warriors, such as the following link on YouTube from BBC News, teaches the preservation and conservation process of unearthing Terra cotta warriors, which is essential to understanding the vastness of this space.

“Terracotta Army: The Greatest Archaeological Find of the 20th Century,” BBC News, YouTube, https://tinyurl.com/ybkc5aqr

AP Art History Image #194. Funner banner of Lady Dai (Xin Zhui). Han Dynasty.

Image: T-Shaped Painting on Silk China Modern Contemporary Art Document, Hunan Provincial Museum https://tinyurl.com/y5h2qzmn

Original CollegeBoard image: https://tinyurl.com/yygwaj9q

Han dynasty: Silk textiles. The funeral banner of Lady Dai (Xin Zhui) of woven and painted silk was found draped over a coffin. This robe banner, fit for an empress, with images of heavenly birds and earthly dragons, offers evidence of the yin-yang of duality. Her mortality is evident in the painting on the banner with her ascent into heaven and her immortality with the sun and moon. I bring in silk to teach students about various textiles. I offer examples of hand silk scarves and embroidery for students to touch the material, as this will help students understand the complexity in textiles. Weaving, embroidery, and painting on fabric are demonstrated. We watch videos such as this one by the Asian Civilizations Museum on silkworms making silk.

“Silk Making in China,” YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zgWVJGRsC90 .

AP Art History Image #195. Similar to Longmen Caves. Tang Dynasty

Images: Left: Yungang Giant Buddha Long Museum West Bund via Google Arts & Culture: https://tinyurl.com/y45zfr84

Right: Monk, probably Ananda (Anantuo) Tang Dynasty (618–907) Metropolitan Museum of Art https://tinyurl.com/y3gzzzx8

Original College Board images: https://tinyurl.com/yygwaj9q

Tang dynasty and Northern Wei dynasty: Cave carving. “Longmen Caves” houses a colossal Buddha, bodhisattvas, Fengxian Temple, and guard protector warriors. The forty-four-foot Buddha of Limestone is in a cave. In situ (on site) works are discussed and compared to art removed from its original location. Buddhism and the Silk Road are researched and traced on a map to gain an understanding of how the essence of this spiritual sculpture inspires future sacred statues across cultures. The students keep a religions journal; Buddhism is a crucial component, with its noble truths and paths to enlightenment. The mudras(hand positions) show up in Christian iconography. My students compare and contrast stone figurative sculptures in marble from the ancient Near East (actually, Southwest Asia), Egypt, Greece, and Rome to the panoply of ancient Buddha sculptures. Romanesque, gothic, and baroque works featuring images of Jesus are examined and contrasted with pictures of early Tang Buddhas. We also discuss patrons of sacred works, such as Empress Wu Zetian, and the artistic women who elevate the arts over time and cultures.

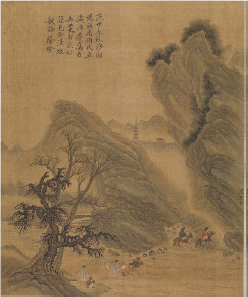

AP Art History Image #201. Similar to Travelers among Mountains and Streams, Fan Kuan. Northern Song Dynasty

Image: Travelers crossing a mountain stream, Freer and Sackler Galleries, Washington, DC, via Google Arts and Culture. https://tinyurl.com/y6bpopac

Song dynasty: landscape painting. “Travelers among Mountains and Streams” by Fan Kuan in ink and colors on silk is part of a larger body of work. Beyond the symbolism of strength in the mountains and cleansing waters as nature’s bounty and resilience resides our power to sit and, as in Dao, “be one with nature.” The power of Qi is also in the observation, practice, and process of painting atmospheric Asian landscape ink work on silk, rolled in scrolls, or on paper. An understanding of East Asian and Chinese traditional ink painting on paper, silk, and a narrative in scrolls is required, so I share authentic examples of landscape scrolls, 2–D flat lithographs of ink paintings, and screen miniatures of both. I encourage my students to try ink watercolor wash painting, touch a real scroll painting, and handle a Japanese screen, as well as atmospheric lithographs. The students study basics in Confucianism as ethical narratives for order with people, leaders, and ways of life in the scroll paintings. Beyond the understanding of religious shifts, materials, methods, and specific visual identifiers are keys to social and traditional belief. Sharing the following YouTube videos on Met art exhibits is also crucial to understanding landscape painting and 2–D narratives in ink on paper or silk. Before visiting the Met, we watch these videos on Chinese landscape painting:

“Streams and Mountains without End: Landscape Traditions of China,” Beijing Review, YouTube, https://tinyurl.com/y5o74h4k .

“Ancient Art Links–Chinese Landscape Paintings at the Metropolitan Museum,” YouTube, https://tinyurl.com/y5zkb999 .

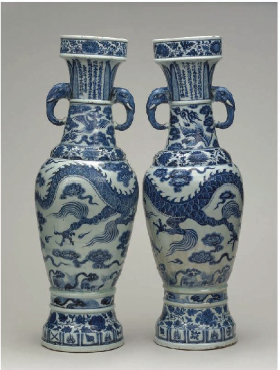

AP Art History Image #204. David Vases, Porcelain Clay. Yuan Dynasty.

Image: The David Vases, British Museum via Google Arts and Culture https://tinyurl.com/y48uk568 Original College Board images: https://tinyurl.com/yygwaj9q

Yuan dynasty: Porcelain clay. The David Vases porcelains (Percival David) are white porcelain with cobalt blue underglaze and a clear overglaze to seal the shiny surface. Dragons, representing earth and power, cover the body, and there is a phoenix rising around the necks with lotus symbols representing spiritual rebirth, reincarnation, and resilience. There are leaf patterns from nature to keep us connected to earthly realms and to male and female energies. These vases were created to sit upon the altar of a Daoist temple. The following links are comprehensive observations of the David vessels including videos and essays from the China Online Museum and Khan Academy. Students are offered clay with blue underglaze to try painting on this surface.

“The David Vases,” China Online Museum, accessed April 24, 2019, https://tinyurl.com/yyqw5yb5 .

“The David Vases,” Khan Academy, accessed April 24, 2019, https://tinyurl.com/yc5u9d99 .

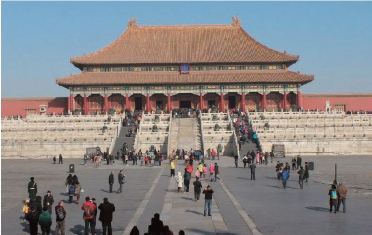

AP Art History Image #206. Forbidden City, Hall of Supreme Harmony. Ming Dynasty.

Image: Imperial Palaces of the Ming and Qing Dynasties in Beijing and Shenyang, Namhansanseong World Hertiage Center via Google Arts and Culture https://tinyurl.com/y4nxqh92

Ming dynasty: Architecture. In Beijing during the Ming dynasty, stonemasonry, marble, brick, wood, ceramic tile, and fully painted wooden soffits and doors adorned the spaces. Students explore an aerial view of the Forbidden City on iPads with links to short videos and essays about this architecture. NCTA offers a comprehensive site (nctasia.org) that connects to several resources, including Asia for Educators, that features history, art, culture, geography, and literature links. We examine the protective dragons, colorful roof soffit designs outside the Hall of Supreme Harmony, and spectacular ceilings inside the Palace of Tranquility and Longevity. Students are encouraged to compare and contrast the marble sculptures, including stone scholar rocks, to another culture and list possible references to the sacred and philosophical scholars of the time across the globe. Understanding maps and floor plans is essential to the study of architecture, and this image maps out the progression of entering a sacred portal; again, the students are encouraged to find similar aspects of progress in Greco–Roman and Christian city complexes. Each progression through the floor plan offers a red gate to go deeper into the Forbidden City. The Noon Gate in the central portal was for the emperor. Other paths were for lower ranks. Students try to understand the auspicious colors and meaning behind some of the flowers and birds. At the end of the compound, the largest wooden building in China, Hall of Supreme Harmony, features seventy-two carved columns. In the emperor’s throne room, we discuss the murals, floral patterns, carvings, gold gilding, and perspective in the paintings. See the link to the Asian Art Museum video of the Forbidden City from Khan Academy below.

“The Forbidden City,” Khan Academy, accessed April 24, 2019, https://tinyurl.com/yc4zgvug .

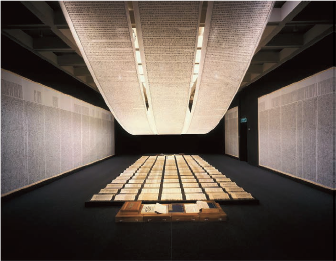

AP Art History Image #229. A Book from the Sky. Xu Bing

Image: A Book From The Sky, Hong Kong Museum of Art via Google Images and Culture https://tinyurl.com/y5s4qp9g

Original College Board images: https://tinyurl.com/y52j9qyj

Global Contemporary: Installation. Xu Bing creates mixed-media installations, such as “A Book from the Sky.” This installation of woodblock prints in scrolls and books features characters that are not as they seem. The characters are his creation; my students enjoy deciphering some of the words in art forms that look like Chinese characters but are English words. Students respectfully conclude that understanding the calligraphy content and context is complex. The essence of the works as sacred texts is evocative, as the books are offered from above and sit as an offering below. His square word, English calligraphy, is featured in the below list of YouTube video resources by Smart History.

I teach a lesson on ink painting with authentic brushes, ink blocks, and paper to allow students to try their hand at this art form. I share examples of block prints, antique Chinese books, scrolls, and screens. The following quotation from the Met’s digital catalog entry on “A Book from the Sky” should assist student thinking about the work: “This set of four books forms part of an eponymous installation first displayed in Beijing in 1988. The books contain 4,000 invented characters that cannot be decoded, raising fundamental questions about the Chinese identity and its relationship to the written word. The artist believes that writing is the ‘essence of culture.’ His subversion of it speaks to our need to communicate and the dangers of distorting or eliminating intended meaning.” 1

“Xu Bing, Book From The Sky,” Khan Academy Smart History, YouTube, https://tinyurl.com/y68hxm8k .

“Xu Bing: Square Word Calligraphy Classroom,” ColumbiaNews, YouTube, https://tinyurl.com/y45vnm5n .

“The Chinese Garden Court at The Metropolitan Museum of Art,” The Met, YouTube, https://tinyurl.com/y3nflmn6 .

Finally, in approaching these objects from China and Asian traditions, it is almost an ethical issue to take the time to examine and appreciate the brilliance of each individual piece. We teach our students to afford the same careful attention and time to non-European traditions and objects as we give to European traditions. But what I have tried to argue here is that the significance of the Asian objects in the AP exam goes beyond the sum of their individual brilliance. There is an argument about the material underpinnings of art and the rich, dense texture of artistic media, embodied in single masterpieces, that invite students to explore more. Students gain a deeper understanding of the art after trying to use the material, so encourage students to explore with traditional materials and techniques in new ways. Those are the two things I want to convey to my students. First, take your time; really look at the auspicious symbols and materials inherent within each dynasty. Second, research and appreciate the intricate power of the Jade Cong, of Lady Dai’s funeral robe; appreciate the confident expression of the Terra Cotta Warriors and the David Vases, the subtlety of ink and canvas in Travelers Among Mountains and Streams, and the allegorical expertise of the Forbidden City to the Book from the Sky. Accept this invitation to explore Asian art with these structures within the material categories: stone, clay, fiber, cave in situ carving, paint on paper or silk, ceramics, wooden architecture, and contemporary installations.

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

Resources for Asian Art Sources on the Web:

Asia For Educators: afe.easia.columbia.edu

Online Museum Resources on Asian Art: afe.museums.easia.columbia.edu

The Metropolitan Museum of Art: www.metmuseum.org

Smarthistory: https://smarthistory.org

1.“ Book from the Sky, ca. 1987–1991,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, accessed April 24, 2019, https://tinyurl.com/y4ahfz5c .

- Latest News

- Join or Renew

- Education About Asia

- Education About Asia Articles

- Asia Shorts Book Series

- Asia Past & Present

- Key Issues in Asian Studies

- Journal of Asian Studies

- The Bibliography of Asian Studies

- AAS-Gale Fellowship

- Council Grants

- Book Prizes

- Graduate Student Paper Prizes

- Distinguished Contributions to Asian Studies Award

- The AAS First Book Subvention Program

- External Grants & Fellowships

- AAS Career Center

- Asian Studies Programs & Centers

- Study Abroad Programs

- Language Database

- Conferences & Events

- #AsiaNow Blog

Contemporary Asian Art in the Twenty-First Century Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Contemporary Asian Art History

Studies show that Asia started creating contemporary or modern art in the 1980s. This aspect indicates that the exhibitions of Asian arts have lagged compared to other countries, which started art exhibitions as early as the 1870s. Research on how Asian arts were acquired and exhibited indicates that items like biennials have experienced an upsurge worldwide since the 1990s (Chua, 2014). This aspect shows how such an upsurge foregrounded the development of new and inventive mods of displaying modern art, which was presumed to put such art in shadow. The process shows that the exhibition of contemporary art in Asia experienced a lag of modernism which had a significant impact on the delay in the development of art exhibitions.

Contemporary Asian Art Exhibition

The development of curatorial products generated twists, turns, trials, and tensions that catalyzed the exhibition of Asian and Southeast Asian contemporary (Chua, 2014). Such processes are presumed to influence the development of new ideas from the curators, artists, editors, and educators who used such ideas to push for the advancement of modern exhibitions, which are not limited to a mere container of objects. On the contrary, the use of such exhibitions aimed at developing narratives that were open-minded (Chua, 2014). However, despite such advancements, the collection and exhibition of Asian and Southeast Asian arts are presumed to experience numerous challenges that create barriers to the effective presentation of contemporary art in Asia.

Historiography of Southeast Asian Contemporary Art

Studies on Asian contemporary art show that it gained relevance in the past two decades. The market for such arts is attributed to the emergence of promising emergent market for investors (Teh, 2020). The lack of dedicated academic structures dealing in the history of the region has not succeeded in the interpretation and historicizing the art making it unfamiliar (Teh, 2020). In addition, the existing history show that the disconnect between the regionalist pioneers and the current nationalists significantly influence the market for contemporary art.

Reasons for Contemporary Art Exhibition

The development of exhibition for contemporary Asian art sought to locate distinctive arts that portrayed modernism in the region. The exhibitions also wanted to privilege the uptake of Asian art in the global market (Chua, 2014). collection of paintings about the war in Asia was considered critical for the development of advanced history of the region during the war (Chua, 2014). In addition, the arts were used to reflect on the aspects that were real during the war in the different parts of the region.

Challenges that Faced Exhibition of Contemporary Asian Art

The development of Asian exhibitions experienced numerous challenges, which made them lack originality. Among the issues the exhibitors experienced was the confusion linked to the theory to apply as they found themselves at a crossroads between utilizing the mimetic theory of art and the stylistic attitude of realism (Chua, 2014). It was due to this reason that the exhibitors experienced the collapse of social realism to optical realism, which was inadequate in the understanding of reality. In addition, the Asian exhibitions had a cliché of the west which they used as a foundation to set their art going (Teh, 2020). Such aspects challenged the originality of the content exhibited, where their art was considered simplification.

Issues Raised by Authors About Asian Exhibitions

An analysis of the variables that significantly influenced the development and success of the exhibition of contemporary Asian arts shows that the continent spends more on understanding realism’s epistemology. The continent needed to be more conceptualized as it was in the western countries where the artists organized different salons where they would exhibit their art (Chua, 2014). In Asia, the lack of convenient space for the orientation of such arts was another issue that the authors raised, as the exhibition required sufficient spaces where different artists would showcase their works. The issue of originality among Asian artists was another critical issue due to the influence of western arts (Chua, 2014). Western cultures influenced the AS in that they could not develop much of their original styles of art. Asians were also perceived to experience progressive infantilism, making them learn new skills that would make their art real (Chua, 2014). Idealistic politics led to the development of psychological blockage, anxiety, and trauma, which had significant impacts on the development of art and paintings.

Strategies Used for the Selection of Arts for Exhibition

The selection of the first 25 pieces of contemporary art presented in the National Art Gallery utilized various strategies to create a distinctive picture of modern Asia art. Realism was a factor that aimed to represent the culture and identity of Asians (Chua, 2014). Due to this reason, the images selected for the exhibition portrayed authentic Asian identity. Furthermore, the exhibition aimed to contain a representation of politics that were coherent, sophisticated, and integrated artistic vision to promote political balance (Chua, 2014). Space was also another factor that was highly considered during the exhibition, as it was structured in constellations structured in a nonlinear manner to showcase time and moments. The strategy brought past arts to the present, the past in the present. The selection of paintings contained imagery and the different themes they produced (Teh, 2020). In addition, the strategy led to the effective collection of art from different parts of the continent. The collection of different paints made it easy for the exhibitors to portray the diversity in arts and paintings linked to the Asian continent (Chua, 2014). Realism is presumed to end static, leading to the development of more dynamic strategies characterized by the respective organized institutions.

Acquisition and Collection of modern and Contemporary Asian Art

Acquiring modern and contemporary art in the different global museums takes different ways. The numerous processes make it easy to identify potential artists and their works and arrange to collect such artworks for a specific gallery. The most common way is through museum boards which can search for such works and purchase them from mainstream galleries (Desai, 2013). Through such processes, the galleries can accumulate resources necessary for acquiring such arts that require large sums of money. In addition, the galleries, at times, engage in long-term work relationships with prominent Artists where they can acquire their works after they complete them (Desai, 2013). Such relationships ensure the flow of artworks directly from the artists (Teh, 2020). In other cases, the galleries can engage in single purchase agreements with artists, enabling them to get various artworks from the Asian continent.

Role of Immigrant in Acquisition and Collection of Asian Arts

Immigrants have also played a critical role in identifying new artists and acquiring artworks from the Asian continent. This is because immigrants have perfect knowledge of the artists from their native countries and can present their works in foreign countries (Desai, 2013). Therefore, the emergence of the immigrant leader is presumed to play a critical role in enabling the transfer of artworks from Asia to the United States, where they find avenues for the sale of native artifacts. In addition, museums and galleries can acquire contemporary Asian art through public auctions.

Issues Facing Acquisition and Collection of Contemporary Asian Arts

The acquisition and collection of artworks from the Asian continent have numerous issues that make the process challenging. The west’s lack of interest in twentieth-century arts has significantly impacted the acquisition of arts in the global market. The west has always influenced Asia’s art in development and consumption. Such aspects are linked to the lack of artistic touch in modern Asian art (Desai, 2013). They focus on developing arts that portray nationalism suited to their national market rather than the global market. Traditional cultural divisions have also played a critical role in representing contemporary art in the global market (Teh, 2020). Although Asian countries’ histories are critical in understanding the development of modern art, the dismissal of national heroes is perceived to be a lack of focus on the art acquisition bodies in the collection of twentieth-century art. The international market is presumed to ignore the national art heroes as they are more suited for portraying nationalism than impressing the global market. Globalization trends are another factor that has influenced the acquisition and collection of contemporary arts where an individual of Asian descent who lives abroad is not acknowledged as they have to return to their country of origin from their country of residence (Desai, 2013).

Local Issues That Influenced Acquisition of Contemporary Arts in the International Markets

Traditional curatorial divisions are presumed to ignore some parts of Asia, where only parts of the continent are represented while others are left out. Such aspects defy the geopolitical definition in Asia, which includes vast areas in south, southeast, east, and central Asia (Desai, 2013). The materials used to develop contemporary art are presumed to influence the acquisition of modern Asian art. The availability of such materials from different parts of the world has made the categorization of such arts challenges. This aspect has acquired Asian art more complex and challenging. in addition, there existed a variety of art acquisition platforms which focused on different types of arts making the market disintegrated.

Acquisition Policies and Re-Think Existing Collection Models

Due to the existing challenges experienced in acquiring modern Asian arts, policies should be developed to ensure that hybrid departments would be made to purchase both modern and contemporary art and take them to the encyclopedic museum. Gallery boards and other independent art collectors should recognize that contemporary Asian art is obtained worldwide (Desai, 2013). In addition, the two existing curatorial departments should be merged to provide a single acquisition scholarship. Such a mechanism would ease the art acquisition process making it more effective. In addition, placing the art acquisition under the department of Asian art would make it easy for the acquiring department to acquire such art from the Asian art market (Teh, 2020). There is also the need to develop a joint fund to acquire twentieth-century art since the lack of funds is a central issue in contemporary art collections. Lastly, there is the need to develop new patterns of art acquisition and collection to incorporate art from new and young talents. Therefore, the mechanisms for art acquisitions should develop a model that should go beyond the existing rivalry and one-upmanship (Desai, 2013). These mechanisms effectively bridge the gap present in the knowledge of contemporary Asian art and embrace the future development of art acquisition and collection.

Chua, K. (2014). Exhibiting Modern Asian Art in Southeast Asia. Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art , 13(2), 105–116. Web.

Desai, V. N. (2013). Beyond the “authentic-exotic”: Collecting contemporary Asian art in the twenty-first century . Collecting the New , 103–114. Web.

Teh, D. (2020). Regionality and Contemporaneity . World Art, 10(2-3), 351–370. Web.

- Decolonizing Museums: Perspectives and Progress

- Arguing against minimalism, and the notion that - less is more

- School Leadership in the Twenty-First Century

- How to Lead and Manage in the Twenty-First Century

- The Whitney, David Zwirner's and Pierogi Galleries

- The Aesthetic Movement and Arts and Crafts Era

- Aspects of the Renaissance in Florence

- The 15th Century Italian Renaissance

- The Difference Between Impressionism and Expressionism

- Contemporary Art as an Example of Social Commentary

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, April 17). Contemporary Asian Art in the Twenty-First Century. https://ivypanda.com/essays/contemporary-asian-art-in-the-twenty-first-century/

"Contemporary Asian Art in the Twenty-First Century." IvyPanda , 17 Apr. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/contemporary-asian-art-in-the-twenty-first-century/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Contemporary Asian Art in the Twenty-First Century'. 17 April.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Contemporary Asian Art in the Twenty-First Century." April 17, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/contemporary-asian-art-in-the-twenty-first-century/.

1. IvyPanda . "Contemporary Asian Art in the Twenty-First Century." April 17, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/contemporary-asian-art-in-the-twenty-first-century/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Contemporary Asian Art in the Twenty-First Century." April 17, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/contemporary-asian-art-in-the-twenty-first-century/.

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

- Our History

- Management Team

- Board of Directors

- Financial and Impact Reports

- Primary Care

- AACI Family Dentistry

- Insurance and Enrollment

- Integrated Behavioral Health

- Patient Portal

- Meet Your Doctors and Care Team

- COVID-19 Info

- Adult and Older Adult (AOA)

- Center for Survivors of Torture (CST)

- Clinical Internship

- Adolescent Drug and Alcohol Prevention & Treatment (ADAPT) Program

- Katie A Program

- Asian Women’s Home

- Driving Under the Influence (DUI) Program

- Senior Wellness Program

- Friday Night Live

- Youth In Technology Incubator

- Growing Up in America (GUA)

- Corporate Engagement

- Better Together 2024

- News & Press Releases

- Client Success Stories

- Healthy Living Blog

- MyChart Login

- Growing Up Asian in America (GUAA)

Stay Tuned! New Contest Details Coming Soon!

Growing up Asian in America

Hosted by AACI and in partnership with NBC Bay Area, Growing Up Asian in America (GUAA) is an annual art, essay and video contest that reaches thousands of Bay Area students in Kindergarten through 12th grade. Founded 25+ years ago, GUAA encourages young Asian Americans to take pride in their identities, and helps others understand the varied experiences of our youth growing up in the Bay Area’s diverse communities.

Founded by Lance Lew of NBC Bay Area in 1995, the contest provides a unique platform for young artists to creatively explore and celebrate being both Asian or Pacific Islander and American. It remains one of the essential celebrations of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month and 10 students will be selected for a cash award and a chance to appear on NBC Bay Area!

Our submission form is now open until March 15th, 2023 and can be accessed here . Learn more below and share the contest widely to Bay Area students! For questions, please contact AACI at (408) 975-2075 or e-mail [email protected]

How to Participate

Become a sponsor.

Press & Media for Growing Up Asian in American and our Media Toolkit is available here .

THANK YOU TO OUR PARTNER, NBC BAY AREA!

THANK YOU TO OUR VISONARY SPONSORS!

THANK YOU TO OUR CHAMPION SPONSORS!

THANK YOU TO OUR CREATOR SPONSORS!

THANK YOU TO OUR PATRON SPONSORS!

THANK YOU TO OUR MEDIA SPONSORS!

- President Barack Obama Main Library

- Childs Park Community Library

- Johnson Community Library

- Mirror Lake Community Library

- North Community Library

- South Community Library

- West Community Library

- Library Administration

- Mission Statement

- Library Policies

- Main Library PDF

- Johnson Branch PDF

- Mirror Lake Branch PDF

- North Branch PDF

- South Branch PDF

- West Community

- St. Petersburg College

- Pinellas County Libraries

- Pinellas Public Library Coop (PPLC)

- Other Area Libraries

- Literacy Council of St. Petersburg

- St. Petersburgs Recreation Centers

- Employment Opportunities

- INFO GUIDES

- cloudLibrary

- TumbleBooks

- ABC Mouse (In Library Only)

- Ancestry (In Library Only)

- AtoZdatabases

- Author Check

- Coronavirus Research Database

- Florida Electronic Library

- Gale Databases

- LinkedIn Learning

- New Book Alerts

- ProCitizen (English)

- ProCitizen (Spanish)

- Pronunciator

- ProQuest Database

- SelectReads

- Tampa Bay Times 1987-Current

- Tampa Bay Times 1901-2009

- Apply for Meeting Room

- Ask a Librarian

- Career Online High School

- Government Documents

- Interlibrary Loan

- Libraries Unshelved

- Microfilm Collection

- Obituary Research

- Online Book Club

- Pinellas Talking Books Library

- READsquared

- SHINE Medicare Counseling

- Take Home Storytime Bundle

- Wi-Fi Hotspots

- Wireless Internet Access

- Yearbook Collection

The President Barack Obama Main Library is temporarily closed for renovations. Click here for more information.

President barack obama main library.

Phone Number : (727) 893-7724 3745 9th Ave. North St. Petersburg, FL 33713

CHILDS PARK LIBRARY

Phone Number : (727) 893-7714 691 43rd St. South St. Petersburg, FL 33711

JAMES W. JOHNSON LIBRARY

Phone Number : (727) 893-7113 1059 18th Ave. South St. Petersburg, FL 33705

MIRROR LAKE LIBRARY

Phone Number : (727) 893-7268 280 5th St. North St. Petersburg, FL 33701

NORTH LIBRARY

Phone Number : (727) 893-7214 861 70th Ave. North St. Petersburg, FL 33702

SOUTH LIBRARY

Phone Number : (727) 893-7244 2300 Roy Hanna Dr. South St. Petersburg, FL 33712

WEST LIBRARY, SPC

Phone Number : (727) 341-7186 6700 8th Ave. North St. Petersburg, FL 33710

APPLY FOR MEETING ROOM

MOBILE PRINTING

Library Wireless Hot Spot Info

home · library catalog · my account · contact us · mobile site Page last updated March 2nd , 2023.

Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

- The Collection