You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

How to Teach Creative Writing | 7 Steps to Get Students Wordsmithing

“I don’t have any ideas!”

“I can’t think of anything!”

While we see creative writing as a world of limitless imagination, our students often see an overwhelming desert of “no idea.”

But when you teach creative writing effectively, you’ll notice that every student is brimming over with ideas that just have to get out.

So what does teaching creative writing effectively look like?

We’ve outlined a seven-step method that will scaffold your students through each phase of the creative process from idea generation through to final edits.

7. Create inspiring and original prompts

Use the following formats to generate prompts that get students inspired:

- personal memories (“Write about a person who taught you an important lesson”)

- imaginative scenarios

- prompts based on a familiar mentor text (e.g. “Write an alternative ending to your favorite book”). These are especially useful for giving struggling students an easy starting point.

- lead-in sentences (“I looked in the mirror and I couldn’t believe my eyes. Somehow overnight I…”).

- fascinating or thought-provoking images with a directive (“Who do you think lives in this mountain cabin? Tell their story”).

Don’t have the time or stuck for ideas? Check out our list of 100 student writing prompts

6. unpack the prompts together.

Explicitly teach your students how to dig deeper into the prompt for engaging and original ideas.

Probing questions are an effective strategy for digging into a prompt. Take this one for example:

“I looked in the mirror and I couldn’t believe my eyes. Somehow overnight I…”

Ask “What questions need answering here?” The first thing students will want to know is:

What happened overnight?

No doubt they’ll be able to come up with plenty of zany answers to that question, but there’s another one they could ask to make things much more interesting:

Who might “I” be?

In this way, you subtly push students to go beyond the obvious and into more original and thoughtful territory. It’s even more useful with a deep prompt:

“Write a story where the main character starts to question something they’ve always believed.”

Here students could ask:

- What sorts of beliefs do people take for granted?

- What might make us question those beliefs?

- What happens when we question something we’ve always thought is true?

- How do we feel when we discover that something isn’t true?

Try splitting students into groups, having each group come up with probing questions for a prompt, and then discussing potential “answers” to these questions as a class.

The most important lesson at this point should be that good ideas take time to generate. So don’t rush this step!

5. Warm-up for writing

A quick warm-up activity will:

- allow students to see what their discussed ideas look like on paper

- help fix the “I don’t know how to start” problem

- warm up writing muscles quite literally (especially important for young learners who are still developing handwriting and fine motor skills).

Freewriting is a particularly effective warm-up. Give students 5–10 minutes to “dump” all their ideas for a prompt onto the page for without worrying about structure, spelling, or grammar.

After about five minutes you’ll notice them starting to get into the groove, and when you call time, they’ll have a better idea of what captures their interest.

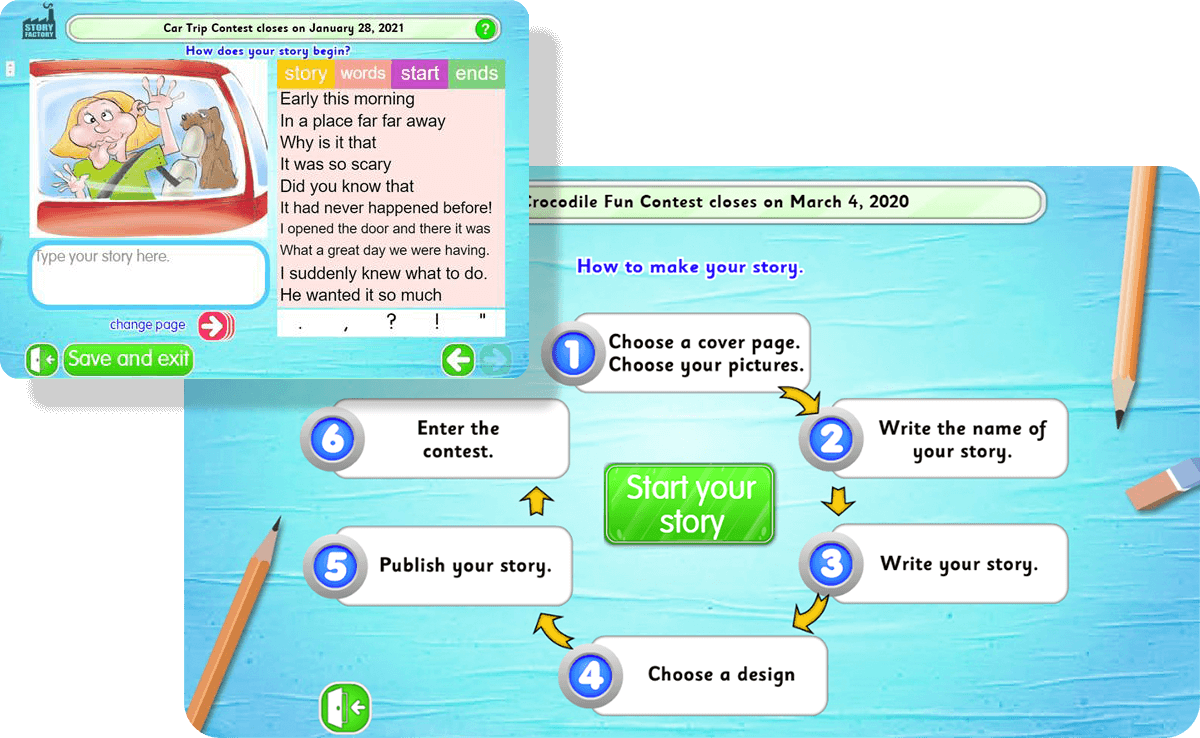

Did you know? The Story Factory in Reading Eggs allows your students to write and publish their own storybooks using an easy step-by-step guide.

4. Start planning

Now it’s time for students to piece all these raw ideas together and generate a plan. This will synthesize disjointed ideas and give them a roadmap for the writing process.

Note: at this stage your strong writers might be more than ready to get started on a creative piece. If so, let them go for it – use planning for students who are still puzzling things out.

Here are four ideas for planning:

Graphic organisers

A graphic organiser will allow your students to plan out the overall structure of their writing. They’re also particularly useful in “chunking” the writing process, so students don’t see it as one big wall of text.

Storyboards and illustrations

These will engage your artistically-minded students and give greater depth to settings and characters. Just make sure that drawing doesn’t overshadow the writing process.

Voice recordings

If you have students who are hesitant to commit words to paper, tell them to think out loud and record it on their device. Often they’ll be surprised at how well their spoken words translate to the page.

Write a blurb

This takes a bit more explicit teaching, but it gets students to concisely summarize all their main ideas (without giving away spoilers). Look at some blurbs on the back of published books before getting them to write their own. Afterward they could test it out on a friend – based on the blurb, would they borrow it from the library?

3. Produce rough drafts

Warmed up and with a plan at the ready, your students are now ready to start wordsmithing. But before they start on a draft, remind them of what a draft is supposed to be:

- a work in progress.

Remind them that if they wait for the perfect words to come, they’ll end up with blank pages .

Instead, it’s time to take some writing risks and get messy. Encourage this by:

- demonstrating the writing process to students yourself

- taking the focus off spelling and grammar (during the drafting stage)

- providing meaningful and in-depth feedback (using words, not ticks!).

Reading Eggs also gives you access to an ever-expanding collection of over 3,500 online books!

2. share drafts for peer feedback.

Don’t saddle yourself with 30 drafts for marking. Peer assessment is a better (and less exhausting) way to ensure everyone receives the feedback they need.

Why? Because for something as personal as creative writing, feedback often translates better when it’s in the familiar and friendly language that only a peer can produce. Looking at each other’s work will also give students more ideas about how they can improve their own.

Scaffold peer feedback to ensure it’s constructive. The following methods work well:

Student rubrics

A simple rubric allows students to deliver more in-depth feedback than “It was pretty good.” The criteria will depend on what you are ultimately looking for, but students could assess each other’s:

- use of language.

Whatever you opt for, just make sure the language you use in the rubric is student-friendly.

Two positives and a focus area

Have students identify two things their peer did well, and one area that they could focus on further, then turn this into written feedback. Model the process for creating specific comments so you get something more constructive than “It was pretty good.” It helps to use stems such as:

I really liked this character because…

I found this idea interesting because it made me think…

I was a bit confused by…

I wonder why you… Maybe you could… instead.

1. The editing stage

Now that students have a draft and feedback, here’s where we teachers often tell them to “go over it” or “give it some final touches.”

But our students don’t always know how to edit.

Scaffold the process with questions that encourage students to think critically about their writing, such as:

- Are there any parts that would be confusing if I wasn’t there to explain them?

- Are there any parts that seem irrelevant to the rest?

- Which parts am I most uncertain about?

- Does the whole thing flow together, or are there parts that seem out of place?

- Are there places where I could have used a better word?

- Are there any grammatical or spelling errors I notice?

Key to this process is getting students to read their creative writing from start to finish .

Important note: if your students are using a word processor, show them where the spell-check is and how to use it. Sounds obvious, but in the age of autocorrect, many students simply don’t know.

A final word on teaching creative writing

Remember that the best writers write regularly.

Incorporate them into your lessons as often as possible, and soon enough, you’ll have just as much fun marking your students’ creative writing as they do producing it.

Need more help supporting your students’ writing?

Read up on how to get reluctant writers writing , strategies for supporting struggling secondary writers , or check out our huge list of writing prompts for kids .

Watch your students get excited about writing and publishing their own storybooks in the Story Factory

You might like....

Six principles for high-quality, effective writing instruction for all students

Editor’s note: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute recently launched “ The Acceleration Imperative ,” a crowd-sourced, evidence-based resource designed to aid instructional leaders’ efforts to address the enormous challenges faced by their students, families, teachers, and staff over the past year. It comprises four chapters split into nineteen individual topics. Over the coming weeks, we will publish each of these as a stand-alone blog post. This is the eighth. Read the first , second , third , fourth , fifth , sixth , and seventh .

Explicit writing instruction not only improves students’ writing skills but also helps build and deepen their content knowledge, boosts reading comprehension and oral language ability, and fosters habits of critical and analytical thinking. The process of planning, writing, and revising can be taught in intentional, sequential steps. In following this process, students can improve their skills and overall comprehension and retention of information. [1] It’s imperative that schools not scrimp on writing instruction as they help students recover from the pandemic.

To be effective, writing should be embedded in the content of the core curriculum and begin at the sentence level. As Judith Hochman and Natalie Wexler describe in The Writing Revolution: A Guide to Advancing Thinking Through Writing in All Subjects and Grades , “Writing and content knowledge are intimately related. You can’t write well about something you don’t know well. The more students know about a topic before they begin to write, the better they’ll be able to write about it. At the same time, the process of writing will deepen their understanding of a topic and help cement that understanding in their memory.” They go on to establish six key principles of the Hochman method, which include explicit skills instruction, the infusion of grammar in practice, and an emphasis on planning and revising. These form a strong basis for high-quality, effective writing instruction for all students.

Recommendations

- Adopt and implement a high-quality English language arts curriculum (see the section on “Reading”).

- Select a writing curriculum and activities that feature explicit, carefully focused instruction and connect to a variety of content areas, including building writing time into all subjects. To date, “ The Writing Revolution ,” also known as the Hochman method, is the only curriculum that combines these two elements.

- Writing activities should start at the sentence level. Tasking young students with longer assignments will overtax them and short-circuit learning. Sentences are the building blocks for all writing.

- Expand teachers’ awareness and enthusiasm for the role that frequent sentence-level writing, sentence expansion and combining, and even note-taking activities can play in enhancing any kind of instruction. A school-wide study of The Writing Revolution can serve as a sound starting point.

- Invest in ongoing curriculum-based professional learning for leaders, instructional coaches, and teachers to build expertise and fully leverage the power of high-quality writing instruction.

Content and cognitive science

There is a robust body of research indicating that writing has the potential to boost comprehension and retention, extending back to the 1970s.

In a landmark study , undergraduates were given five minutes to read an article. They then were randomly assigned to one of four tasks: reading the article once; studying it for fifteen additional minutes; creating a “concept map” or bubble diagram of the ideas in the article; or writing what they could remember from the passage, known as “retrieval practice.” When tested a week later, the group that had engaged in writing had a clear advantage in recalling information and making inferences. [2]

Writing about a topic is akin to preparing to teach something you have learned, which has also been shown to improve recall, a phenomenon called the “protégé effect.” [3] Essentially, writing requires students to recall something they have slightly forgotten (the mechanism at work in retrieval practice) and explain it in their own words (the mechanism at work in the protégé effect). A recent meta-analysis found that writing about content in science, social studies, and math reliably enhances learning in all three subjects. [4]

But most existing approaches to writing instruction fail to take full advantage of these potential benefits. Instead, they ask students to write about their own experiences or about random topics, without providing much background information.

In addition, most instructional approaches vastly underestimate how difficult it is to learn to write. [5] Young students may be juggling everything from letter formation and spelling to putting their thoughts in a logical order. Yet virtually all strategies expect inexperienced writers, including kindergartners, to write multiple-paragraph essays. The theory is that students need to develop their voice, fluency, and writing stamina from the earliest stages. But writing at length only increases cognitive load, potentially overwhelming working memory and depriving students of the cognitive capacity to absorb and analyze the information they’re writing about, much less acquire target skills. [6]

The Institute of Education Science’s Practice Guide on elementary writing cites twenty-five studies finding a variety of positive effects that follow from paying close attention to the writing process. It also recommends that one hour a day be devoted to students’ writing beginning in the first grade, and acknowledges that this is unlikely to be achieved unless writing practice occurs in the context of non-ELA content area instruction. [7]

Starting at the sentence level

Studies have shown the positive effects of interventions such as sentence combining and sentence expansion and teaching sentence-construction skills generally. [8] The IES Practice Guide recommends that students be taught to construct sentences. There are also indications in the literature on “writing to learn” that shorter writing assignments, including poems, yield larger benefits. [9] In addition, focusing on learning to construct sentences before moving on to paragraphs lightens the load on students’ working memory, freeing up cognitive space for absorbing and analyzing the content they’re writing about.

And yet for some reason, there appears to have been no studies testing whether there are greater benefits from an approach that explicitly teaches students to write sentences before asking them to embark on lengthier writing.

In the meantime, it’s best to begin writing at the sentence level. Sentence-level instruction not only lightens cognitive load, it also makes instruction in the conventions of written language—such as grammar, punctuation, etc.—far more manageable. Teachers confronted with page after page of error-filled writing often don’t know where to begin, and they don’t want to discourage students by handing back a sea of red ink. And if students can’t write a good sentence, they’ll never be able to write a good paragraph or a good essay.

Many students don’t easily absorb the mechanics of constructing sentences from their reading, as most approaches to writing instruction assume. Rather, they need to practice how to use conjunctions, appositives, transition words, and so forth. Activities that teach these skills, when embedded in the content of the curriculum, simultaneously build writing skills, content knowledge, and analytical abilities.

For example, students learning about the Civil War might be given the sentence stem “Abraham Lincoln was a great president _____________.” and then asked to finish it in three different ways, using “because,” “but,” and “so.” This kind of explicit instruction can also familiarize students with the syntax and vocabulary that are found in written but not spoken language, and can boost reading comprehension. Once you have learned to use a word like “despite” or a construction like the passive voice in your own writing, you’re in a much better position to understand it when you encounter it while reading.

Example: The Writing Revolution

The potential of explicit writing instruction that is embedded in the content of the curriculum and begins with sentence-level strategies is enormous. As far as can be determined, the Writing Revolution method is currently the only approach to writing instruction that combines these two features. It rests on six key principles:

- Students need explicit instruction in writing, beginning in the early elementary grades.

- Sentences are the building blocks of all writing.

- When embedded in the content of the curriculum, writing instruction is a powerful teaching tool.

- The content of the curriculum drives the rigor of the writing activities.

- Grammar is best taught in the context of student writing.

- The two most important phases of the writing process are planning and revising.

Once students are ready for lengthier pieces, the Writing Revolution focuses considerable attention on teaching students to construct clear, linear outlines. When students transform their outlines into finished pieces of writing, they are able to construct coherent, fluent paragraphs and essays by drawing on the sentence-level strategies they have been taught.

Reading List

Arnold, K., Umanath, S., Thio. K., Reilly, W., McDaniel, M., Marsh, E. (2017). Understanding the cognitive processes involved in writing to learn. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied. 23(2), 115-127.

Bangert-Drowns, R., Hurley, M. and Wilkinson, B. (2004). The Effects of School-Based Writing-to-Learn Interventions on Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analysis. Review of Educational Research. 74(1), 29-58.

Graham, S., and Hebert, M. A. (2010). “ Writing to Read: Evidence for how Writing Can Improve Reading. Carnegie Corporation Time to Act Report. ” Washington, D.C.: Alliance for Excellent Education.

- Teaching sentence-construction skills has improved reading fluency and comprehension.

Graham, S. and Perin, D. (2007). “ Writing Next: Effective Strategies to Improve Writing of Adolescents in Middle and High Schools – A report to Carnegie Corporation of New York. ” Washington, D.C.: Alliance for Excellent Education.

Graham, S., Kiuhara, S.A., and MacKay, M. (2020). The effects of writing on learning in science, social studies, and mathematics: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research. 90(2), 179-226.

- Embedding writing instruction in content and having students write about what they are learning in English language arts, social studies, science, and math has boosted reading comprehension and learning across grade levels.

Hochman, J. and Wexler, N. (2017). The Writing Revolution: A Guide to Advancing Thinking Through Writing in All Subjects and Grades . Jossey-Bass.

Graham, S., Bollinger, A., Booth Olson, C., D’Aoust, C., MacArthur, C., McCutchen, D., and Olinghouse, N.(2012). “ Teaching elementary school students to be effective writers: A practice guide (NCEE 2012-4058).” Washington, D.C.: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

Karpicke, J., and Blunt, J. (2011). Retrieval Practice Produces More Learning than Elaborative Studying with Concept Mapping. Science. 331(6018) 772-775.

Mueller, P. A., and Oppenheimer, D. M. (2014). The Pen Is Mightier Than the Keyboard: Advantages of Longhand Over Laptop Note Taking. Psychological Science , 25(6), 1159–1168.

- Two key takeaways: the benefits of writing for information retention are strongest with writing by hand rather than on the computer; and the act of writing solidifies students’ knowledge of a subject.

Naka, M., & Naoi, H. (1995). The effect of repeated writing on memory. Memory & Cognition, 23(2), 201–212.

- Demonstrates the crucial link between writing about something and remembering the content involved.

Panero, N.S. (2016). Progressive mastery through deliberate practice: A promising approach for improving writing. Improving Schools , 19(3), 229-245.

- Summarizes the research on improving writing quality as well as writing strategies that improve reading comprehension, and connects those to practices taught in The Writing Revolution.

Seven, S., Koksal, A.P., Kocak, G. (2017). The Effect of Carrying out Writing to Learn Activities on Academic Success of Fifth Grade Students in Secondary School on the Subject of ‘Force and Motion. Universal Journal of Educational Research. 5(5), 744-749.

Tindle, R. and Longstaff, M.G. (2015). Writing, Reading and Listening Differentially Overload Working Memory Performance Across the Serial Position Curve. Advances in Cognitive Psychology. 11(4), 147-155.

Wexler, N. (2019). “Writing and cognitive load theory,” ResearchED , Issue 4,

- “Writing can impose such a heavy burden on working memory that students become overwhelmed, unable either to improve their writing skill or to benefit from the positive effects that writing can have on reading comprehension and learning in general.”

Willingham, D. (2003). Students remember … what they think about. American Educator, 27(2), 37–41.

- Writing can facilitate students’ thinking about what they are supposed to learn.

[1] From Brian Pick: I think it is important here to address both the writing process and the writing mechanics. Both matter but sometimes schools focus almost exclusively on only one or the other.

[2] From the editors: See “ Retrieval Practice Produces More Learning than Elaborative Studying with Concept Mapping .” For more about writing and retrieval, see “The effect of repeated writing on memory,” which compares memorization among Japanese and American students using writing as a memorization strategy.

[3] From the editors: For example, in a study by Muis et al., elementary students who were solving complex math problems used more metacognitive strategies when preparing to teach those strategies compared to a control group. In a study by Nestojko et al. , participants who were told they would be teaching a passage had better recall than those who were told they would be tested on the passage.

[4] From the editors: See “ The Effects of Writing on Learning in Science, Social Studies, and Mathematics: A Meta-Analysis. ”

[5] From the editors: Research shows that writing imposes a heavier cognitive load on working memory than reading. See “ Writing, Reading, and Listening Differentially Overload Working Memory Performance Across the Serial Position Curve .”

[6] From Jamila Newman: I think it's important that schools see writing as gateway to student independence and agency. Reading and listening often position students as consumers, but writing and speaking position students as producers of argument, opinion, and ideas.

[7] From the editors: See “Teaching Elementary School Students to Be Effective Writers.”

[8] From the editors: See both “ Writing Next” and “Writing to Read,” two Carnegie Corporation of New York reports published by the Alliance for Excellent Education.

[9] From the editors: See “The Effects of School-Based Writing-to-Learn Interventions on Academic Achievement” and “The Effect of Carrying out Writing to Learn Activities on Academic Success of Fifth Grade Students in Secondary School on the Subject of ‘Force and Motion’.”

CAO Central is a new wiki-style website on which the Fordham Institute is hosting “ The Acceleration Imperative ,” an open-source, evidence-based document created with input from dozens of current and former chief academic officers, scholars, and others with deep expertise and experience in high-performing, high-poverty elementary schools. The…

Related Content

Gadfly Bites 9/9/24—Monday is a good news day

By refusing to bus students, Columbus City Schools sinks to a new low

Ohio Charter News Weekly – 9.6.24

4 strategies for teaching creative writing

- Share Article

Tip 1: Crossing out

Tip 2: explicitly teach sentence stems, tip 3: build a planning routine, tip 4: go big or go home.

A blank page can be a fearful thing. As I sit typing this (cocooned in the corner of a bustling coffee shop), it seems a fearful thing to me, too. One by one, words tentatively appear, and yet the whiteness of the page dominates and suffocates the lettered blackness.

It can be an especially fearful thing for our students. Surrounded by the silence of an examination hall, pens scratching cold paper, they sit and stare at the mountainous alps of their booklet. The summit stretches out a great distance away, with so little time to plot and navigate their way.

This is often most keenly felt in creative writing. Being creative on demand is no easy task. The blankness of the paper is only compounded by the apparent blankness of ideas. And still, the clock ticks. In this article, I’ll share four top tips for helping students get better at creative writing, ensuring they always have something ready to fill the whiteness of the page.

One of the biggest conceptual shifts I’ve made in my teaching of creative writing is to focus on crossing out . When we—or our students— cross something out in their writing, what does it imply? It invariably implies a moment of thought and consideration. Is this the best word the gesture suggests, or should I use a different one?

Encouraging students to adopt a crossing-out mentality can be hugely powerful. As we write, I’ll often remind students to look for any words they could cross out, modelling this in my own writing. As I write, I cross out, always being sure to narrate why I’ve crossed something out and what is replacing it .

Of course, in and of itself, crossing out does not guarantee progress. It is a proxy, but a helpful one. Crossing out becomes a concrete and easily understood analogy for the kind of deliberate, sustained crafting that so often characterises the best writing. We don’t just want students to fill up their blank pages; we want them to fill them up with excellent writing .

In order to cross out, students need something to cross out in the first place. This is where repeatable and recyclable sentence stems come into their own. They provide students with snippets of excellent writing they can drag and drop into their response, adapting as necessary.

Students often complain—rightly so—that creative writing can be bereft of content to revise. Sentence stems give them something tangible to rehearse. Teach them in advance, show students how to manipulate them, and get students to experiment on their own.

If the sentence occupies the micro, then students also need a sharp and cohesive macro structure in order to succeed. This is where planning becomes essential.

To help students with this, I explicitly teach and model a particular planning routine that can be adapted and adopted at the start of an examination. This helps students make sure they’re asking the best questions as well as get them into the zone.

This routine always looks the same, sketched out on a single side of A4, and goes like this:

- POV: Students decide the narrative point of view they wish to adopt, which is especially valuable if responding to an image, like many questions require.

- Happy or sad: Students now consider if their point of view is happy or sad. I purposely keep this question very broad, but they may wish to be a little more nuanced in their emotional choice. The key is that they’re thinking about an emotional groove for their piece.

- Why? Now, students can reflect on why their point of view is happy or sad, beginning to build some kind of backstory or narrative thrust to their writing.

At this point, and with some basics covered, students can sketch out an overall structure for their response. At the most basic level possible, I like: First, Next, Next, And Then . What happens first, and then next, and then next, and then how does it end?

Finally, I ask students to consider a big idea they would like to convey within their writing.

With all of this mapped out, students can now begin to write.

Let’s pause for a moment on this idea of a ‘big idea’. It is easy to imagine what this means when teaching a literature text, and we probably spend a lot of time considering it with our classes.

What is Shakespeare trying to accomplish in Macbeth, we might explore? Interwoven with our discussion of the play, we consider Shakespeare’s depiction of power and the way it corrupts, as well as his depiction of kingship or femininity. These are some of the play’s big ideas.

A consideration of the ‘big’ is just as important for a student’s own writing as it is for the literature they study. What is it that they wish to show or explore in their writing? What do they want to do? Helping students to appreciate they can have something to say within their own writing can be truly empowering and liberating.

In my own modelling, I like to return to the concept of time . This unlocks so many interesting directions: transience, time passing, memory, recapturing youth. But it also provides a wealth of imagery for students to leverage. Wrinkled hands, a faded wedding ring, a scratched and crumpled photograph, an item of clothing lovingly stored away at the back of a wardrobe, gathering dust.

This block is currently empty. Please add some content.

A blank page can be a fearful thing, it’s true. But one filled with scribbled writing, well, that can be joyful.

These four strategies will hopefully help your students make sure they turn their blank pages into a piece of writing they can be truly proud of.

Andrew Atherton

Andrew Atherton is an English teacher at a school in Berkshire. He runs the popular blog site Codexterous , which includes a wealth of posts outlining strategies for teaching English Literature and English Language as well as lots of resources.

Recent Posts

Understanding the different types of UK secondary schools

Navigating the world of secondary schools can be daunting for any parent. Our comprehensive guide breaks down the different types of UK secondary schools, from state-funded options to independent schools. Learn about key factors to consider, including academic performance, school ethos, and admissions criteria.

Essential maths skills for A Level Biology

Strong maths skills are essential for success in A Level Biology. In this article, expert examiner Teresa outlines which math skills you need to know and how you can practice them effectively. With practical tips and clear guidance, you'll gain the confidence to tackle maths questions with ease.

How I learned to love the mini whiteboard!

Mini whiteboards are a game-changer in the classroom. They allow teachers to quickly assess every student's understanding, enforce accountability, and encourage risk-taking. This article by science teacher Dan explores how these simple tools can boost participation and transform your teaching.

Search by Topic

- Behaviour (1)

- Diversity (1)

- Finances (4)

- Inspection and Observation (2)

- Leadership (1)

- Pedagogy (15)

- Planning and Organisation (3)

- Post-16 Options (7)

- Revision and Exams (13)

- Science Teaching (3)

- SEND Teaching (2)

- Study Skills (11)

- Tuition (10)

- University (12)

- Wellbeing (13)

Related Posts

Metacognitive marking: Boosting student reflection

Boost student metacognition with 'blue sky highlighting'. Learn how this simple feedback strategy can transform your classroom, encouraging students to think deeply about their work and become more independent learners. Discover easy-to-implement techniques to make feedback more engaging and effective.

Teacher CPD: Will yours be in the 1%?

Discover how to make your teacher CPD truly impactful with expert insights from Evidence Lead in Education, Jade Pearce. With only 1% of CPD changing teacher practice, learn 10 actionable strategies to ensure your professional development programs enhance both teacher performance and pupil outcomes.

Join Our Community

Sign up to our monthly newsletter to be kept in the loop about new resources, blogs and more.

Our ambition is to guide students from secondary school into their adult life.

- Uni Admissions

- Bursary Scheme

- For Schools

- Revision Resources

- Computer Science

- Find a Tutor

- How it Works

- Teacher Resources

- Information

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Safeguarding Policies

- The Student Experience

- Financial Aid

- Degree Finder

- Undergraduate Arts & Sciences

- Departments and Programs

- Research, Scholarship & Creativity

- Centers & Institutes

- Geisel School of Medicine

- Guarini School of Graduate & Advanced Studies

- Thayer School of Engineering

- Tuck School of Business

Campus Life

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Athletics & Recreation

- Student Groups & Activities

- Residential Life

Writing Program

- [email protected] Contact & Department Info Mail

- Writing Instruction

- Writing Support

- Past Prize Winners

- Writing 2-3 Teaching Assistantships

- Apply to Tutor

- Writing Requirement & Scheduling

- Differences Among First-Year Writing Courses

- Writing 2-3

- Humanities 1-2

- First-Year Seminars

- Directed Self-Placement

- Writing 2-3 Registration

- Writing 5 Registration

- First-year Seminar Registration

- Registration FAQ

- Teaching Writing in the First Year

- Expectations for Teaching Writing 2-3

- Expectations for Teaching Writing 5

- Expectations for Teaching First-Year Seminar

- Active Learning

- Syllabus and Assignment Design

- Teaching Writing as Process

- Integrating Reading and Writing

- Diagnosing and Responding

- Conducting Writing Workshops

- Collaborative Learning

- Teaching Argument

- Teaching Research

- Addressing Grammar

- Useful Links

- Academic Integrity

- Processes & Practices of a Scholarly Community

- Quality of Sources

- The Writing Center

- Multilingual Support

- News & Events

Search form

- Teaching Guidelines

Active Learning in the First-Year Writing Classroom

Active learning: aims and implications.

The Writing Program's Faculty Resource pages aim to:

- Outline a pedagogy that coheres the various methods commonly used in Dartmouth's writing classrooms;

- Offer strategies to make these methods even more effective;

- Introduce our methods and philosophies to instructors who are new to the program.

Dartmouth's writing instructors employ an array of effective instructional methods as they teach writing. Many of these methods are drawn from the pedagogy known as Active Learning (sometimes referred to as "engaged learning," or "student-centered learning"). Active Learning pedagogy seeks to overhaul the model of education in which students impassively receive knowledge from their instructors. In Active Learning classrooms, students are challenged to forego passivity in favor of contribution and participation. Responsibility for learning changes hands as instructors and students collaborate to teach and learn from one another

Active Learning classrooms are distinguished by three principles:

- Active Learning is student-driven. In the Active Learning classroom, students might be asked to lead discussion, to design their own writing assignments, to instruct their peers, and to collaborate with their instructor to determine course aims and assess course work.

- Active Learning teaches students how to learn in collaboration with their peers, creating a community that facilitates learning. This community, properly designed, helps students to understand the expectations and conventions of the community of scholars that they are about to join.

- Active Learning asks instructors to transfer to students some portion of the authority that has traditionally been theirs. Students, in turn, take increased responsibility for their writing educations. Transferring authority requires instructors to shift their focus from setting standards to diagnosing problems, from giving direction to facilitating learning, from focusing exclusively on product to supporting process. In the Active Learning classroom, instructors, like students, remain actively engaged.

Effective Methods

Instructors employ active learning principles in our writing classrooms in a number of ways.

Let students teach one another. One of the best ways to master something is to teach it. Students become better writers when you put teaching responsibilities into their hands. Placing your students into peer editing groups in which they diagnose and respond to problems in their classmates' papers not only sharpens their critical skills but also shows them how to talk and think about writing. Students eventually internalize these discussions and draw on them as they write. For a fuller discussion of the benefits and the methods of peer instruction, see Collaborative Learning . For specific advice regarding sharpening students' peer editing skills, see Diagnosing and Responding .

Make student writing a text in the class. Instructors who embrace the student-centered principles of Active Learning understand how important it is to conduct Writing Workshops, in which student papers are read and discussed in class. Making student writing a text in the class signals to students not only that you take their writing seriously, but also that they are now part of the ongoing conversation of scholarship. Making student writing a text in the class also allows you to teach students to diagnose and respond to problems that come up in their writing. For a fuller discussion regarding why and how to make student writing a text in the class, see Conducting Writing Workshops .

Expect students to direct discussion; invite them to teach a class. Writing instructors conduct their classes via discussion rather than lectures. But even in discussion classes, professors exert authority. Too often in discussion students are more concerned with performing to please the professor than they are with genuinely pursuing a line of inquiry. Active Learning instructors expect students to determine the focus of the discussion. Some invite students to co-facilitate discussions. Others assign presentations. In all cases instructors ask students NOT to position their classmates as passive listeners. Like the instructor, student facilitators are expected to teach using Active Learning methods.

Ask students to design their own writing assignments. Developing elaborate, well-articulated prompts has certain pedagogical advantages. But letting students discover their own questions and letting them design their own writing prompts not only gives them the power to approach assignments on their own terms, but also gives them practice in the methods of scholarly inquiry. For more information, see Syllabus and Assignment Design .

Involve students in assessment. Those of us who routinely practice Active Learning principles understand that the act of grading can undo the transfer of power that we've been working so hard to achieve. One way of avoiding this "undo" is to involve students in the assessment process. Devote a class to discussing the qualities of good writing; collaborate with the students to define standards or to design a rubric for grading; invite the students to grade an assignment with you, and let those grades have weight equal to yours. (The last strategy works particularly well when grading class presentations, when effectively engaging the audience is a concern.)

Adopt a descriptive, rather than a prescriptive, attitude toward grammar and style. Presenting grammar and style as a series of rules insures that students will remain in the position of "apprentice" writers. Describing grammar in terms of reader expectations and discourse conventions helps students to figure out how to write for an academic audience. Students are thereby positioned as fully responsible participators in the academic conversation. For fuller discussions, see Addressing Grammar .

Provide students with opportunities to fail and to revise. Active Learning theorist Ken Bain argues in his book, What the Best College Teachers Do , that real teaching requires three steps: 1) Show your students that their models fail/are inadequate; 2) Make them care enough to find new models; 3) Support them while they do. Once you've convinced students their high-school models for thinking and writing won't work, you'll need to give them plenty of time to find new models. This means that you'll have to give them time to draft and redraft their papers, so that they can see where their work is coming up short and will have the time (and the desire) to revise it.

Common Concerns

Many instructors resist adopting Active Learning methods. They are concerned that these methods require considerable amounts of time. They worry about letting go of their control over the classroom. They are concerned that students won't understand these methods, will find them frustrating, and will express this frustration on course evaluations. They are also hesitant to use methods in class that they haven't used before. If these methods fail, students will leave their writing classes without the requisite skills.

We address these concerns in turn.

Time. Active Learning does take time: class time, conference time, and preparation time. But it's not as time-intensive as many instructors think. We offer the following reassurances:

- Class time: Not all Active Learning instruction needs to happen in class. One of the benefits of adopting this model is that you are asking students to teach one another. You can therefore ask students to meet outside of class to talk about their papers; you can also ask them to conduct peer critique on the Canvas discussion board. You'll want to oversee peer instruction by monitoring Canvas postings or by asking students to summarize, in writing, the peer work they do outside of class. Either way, class time needn't be overwhelmed by Active Learning exercises.

- Conference time: One advantage of the Active Learning classroom is that collaborative learning techniques can be extended to the conference dynamic. If you've divided your students into editing groups, confer with students in groups rather than individually. This method is not only time-efficient, it's also effective. Too often the one-one-one conference turns into a fix-it session, with students seeking specific instruction about how to make a paper work. In group conferences, students engage in debates about writing. Reading three or four papers rather than one encourages students to determine more generally what works (and what doesn't). They'll take with them a better sense of the principles (rather than simply the particulars) of good writing.

- Preparation: The shift to Active Learning is more qualitative than quantitative. That is, Active Learning requires you to position yourself differently vis a vis your class and your teaching. In this way, Active Learning requires not more work, but different work. If students are indeed sharing the work of teaching, preparation time can be reduced. The hours spent crafting an assignment or determining discussion questions are eliminated if students are entrusted to do these things for themselves.

Control. Instructors who are hesitant to give up control don't trust that first-year students are ready to take charge of their own educations. First-year students are newcomers to the academy. How can they decode its conventions or its expectations? How can they be expected to take charge of their learning? We respond by saying that students in Active Learning classrooms can puzzle out the conventions together. Rather than telling them what is expected of them and then turning them loose to write, you'll be presenting them with models of academic writing (student and scholarly) and then working with them to determine conventions. The latter methodology is far more likely to "stick."

Evaluations. Some instructors worry that students will not understand the rationale for active learning, and that these "strange" methods might be remarked upon in evaluations. Students do sometimes find Active Learning methods frustrating. For instance, students, who are "loner learners" don't like to work in groups. Others who are result-oriented don't see the point in spending time talking about process. We've found, however, that resistant students can be brought on board by making the rationale for Active Learning clear. When your methods are transparent, students (in particular first-year students) will generally be willing to give them a chance. They'll also be more likely to evaluate your success in meeting your goals if you've clearly stated them.

Failure. Instructors are justifiably concerned that a new, unfamiliar teaching method might fail. Indeed, not every method or exercise you employ will succeed. But both you and your students can learn from these failures. If an assignment or exercise doesn't work, talk with your students. Get them to brainstorm reasons for why the method isn't succeeding. This will not only help you to make adjustments, it will require your students to reflect upon teaching and learning methods. It will also prove to your students that you care what they think.

Using Technology to Support Active Learning

Canvas is an excellent tool to support Active Learning goals in the writing classroom. Discussion boards can be used to facilitate peer commentary; wikis can be used for collaborative writing and research assignments. Best of all, Canvas is flexible enough that it can be adapted to meet almost any of your teaching goals.

Week One Creative Writing Lesson Plans: Expert Guide

Looking for creative writing lesson plans? I am developing creative writing lesson ideas!

I’ve written and revamped my creative writing lesson plans and learned that the first week is vital in establishing a community of writers, in outlining expectations, and in working with a new class.

What are some good creative writing exercises?

Some good creative writing exercises include writing prompts, free writing, character development exercises, and fun writing games.

The first week, though, we establish trust—and then we begin powerful creative writing exercises to engage young writers and our community.

How can add encouragement in creative writing lesson plans?

I’ve found students are shy about writing creatively, about sharing pieces of themselves. A large part of the first week of class is setting the atmosphere, of showing everyone they are free to create. And! These concepts will apply to most writing lesson plans for secondary students.

Feel free to give me feedback and borrow all that you need! Below, find my detailed my day-by-day progression for creative writing lesson plans for week one.

Creative Writing Lesson Day One: Sharing my vision

Comfort matters for young writers. I’m not a huge “ice breaker” type of teacher—I build relationships slowly. Still, to get student writing, we must establish that everyone is safe to explore, to write, to error.

Here are some ideas.

Tone and attitude

For day one with any lesson plan for creative writing, I think it is important to set the tone, to immediately establish what I want from my creative writing students. And that is…

them not to write for me, but for them. I don’t want them writing what they think I want them to write.

Does that make sense? Limitations hurt young writers. My overall tone and attitude toward young writers is that we will work together, create and write together, provide feedback, and invest in ourselves. Older kiddos think that they must provide teachers with the “correct” writing. In such a course, restrictions and boundaries largely go out the window.

Plus, I specifically outline what I believe they can produce in a presentation to set people at ease.

The presentation covers expectations for the class. As the teacher, I am a sort of writing coach with ideas that will not work for everyone. Writers should explore different methods and realize what works for them. First, not everyone will appreciate every type of writing—which is fine. But as a writing community, we must accept that we may not be the target audience for every piece of work.

Therefore, respect is a large component of the class. Be sure to outline what interactions you find acceptable within your classroom community.

Next, as their writing coach, I plan to provide ideas and tools for use. Their job is to decide what tools work for their creative endeavors. My overall message is uplifting and encouraging.

Finally, when we finish, I share the presentation with students so they can consult it throughout the semester. The presentation works nicely for meet-the-teacher night, too!

After covering classroom procedures and rules, I show students a TED Talk. We watch The Danger of a Single Story by Chimamanda Adichie. My goal is to show students that I don’t have a predetermined idea concerning what they should write. This discussion takes the rest of the class period.

Establishing comfort and excitement precedents my other creative writing activities. Personalize your “vision” activities for your lessons in creative writing. Honestly, doing this pre-work builds relationships with students and creates a positive classroom atmosphere.

Creative Writing Lesson Day Two: Activating prior knowledge

Students possess prior knowledge concerning creative writing, but they might not consider that. Students should realize that they know what constitutes a great story. They might not realize that yet. An easy lesson plan for creative writing that will pay off later is to activate prior knowledge. Brainstorm creative, memorable, unforgettable stories with students. Share your thoughts too! You will start to build relationships with students who share the same tastes as you (and those that are completely different!).

Activation activity

During this activity, I want to see how students work together, and I want to build a rapport with students. Additionally, activating prior knowledge provides a smooth transition into other creative writing activities.

This creative writing activity is simple:

I ask students to tell me memorable stories—books, play, tv shows, movies—and I write them on the board. I add and veto as appropriate. Normally doing these classroom discussions, we dive deeper into comedies and creative nonfiction. Sometimes as we work, I ask students to research certain stories and definitions. I normally take a picture of our work so that I can build creative writing lessons from students’ interests.

This takes longer than you might think, but I like that aspect. This information can help me shape my future lessons.

With about twenty minutes left in class, I ask students to form small groups. I want them to derive what makes these stories memorable. Since students complete group and partner activities in this class, I also watch and see how they interact.

Students often draw conclusions about what makes a story memorable:

- Realistic or true-to-life characters.

- Meaningful themes.

- Funny or sad events.

All of this information will be used later as students work on their own writing. Many times, my creative writing lessons overlap, especially concerning the feedback from young writers.

Creative Writing Lesson Day Three: Brainstorming and a graphic organizer

From building creative writing activities and implementing them, I now realize that students think they will sit and write. Ta-da! After all, this isn’t academic writing. Coaching creative writing students is part of the process.

Young writers must accept that a first draft is simply that, a first draft. Building a project requires thought and mistakes. (Any writing endeavor does, really.) Students hear ‘creative writing’ and they think… easy. Therefore, a first week lesson plan for creative writing should touch on what creativity is.

Really, creativity is everywhere. We complete a graphic organizer titled, “Where is Creativity?” Students brainstorm familiar areas that they may not realize have such pieces.

The ideas they compile stir all sorts of conversations:

- Restaurants

- Movie theaters

- Amusement parks

By completing this graphic organizer, we discuss how creativity surrounds us, how we can incorporate different pieces in our writing, and how different areas influence our processes.

Creative Writing Lesson, Days Four and Five: Creative Nonfiction

Students need practice writing, and they need to understand that they will not use every word they write. Cutting out lines is painful for them! Often, a lesson plan for creative writing involves providing time for meaningful writing.

For two days, we study and discuss creative nonfiction. Students start by reading an overview of creative nonfiction . (If you need mentor texts, that website has some as well.) When I have books available, I show the class examples of creative nonfiction.

We then continue through elements of a narrative . Classes are sometimes surprised that a narrative can be nonfiction.

The narrative writing is our first large project. As we continue, students are responsible for smaller projects as well. This keeps them writing most days.

Overall, my students and I work together during the first week of any creative writing class. I encourage them to write, and I cheer on their progress. My message to classes is that their writing has value, and an audience exists for their creations.

And that is my week one! The quick recap:

Week One Creative Writing Lesson Plans

Monday: Rules, procedures, TED Talk, discussion.

Tuesday: Prior knowledge—brainstorm the modeling of memorable stories. Draw conclusions about storytelling with anchor charts. Build community through common knowledge.

Wednesday: Graphic organizer.

Thursday and Friday: Creative nonfiction. Start narrative writing.

Students do well with this small assignment for the second week, and then we move to longer creative writing assignments . When classesexperience success with their first assignment, you can start constructive editing and revising with them as the class continues.

These creative writing activities should be easy implement and personalize for your students.

Would you like access to our free library of downloads?

Marketing Permissions

We will send you emails, but we will never sell your address.

You can change your mind at any time by clicking the unsubscribe link in the footer of any email you receive from us, or by contacting us at [email protected] . We will treat your information with respect. For more information about our privacy practices please visit our website. By clicking below, you agree that we may process your information in accordance with these terms.

We use Mailchimp as our marketing platform. By clicking below to subscribe, you acknowledge that your information will be transferred to Mailchimp for processing. Learn more about Mailchimp’s privacy practices.

Are you interested in more creative writing lesson ideas? My Facebook page has interactive educators who love to discuss creative writing for middle school and high school creative writing lesson plans. Join us!

creative writing creative writing activities

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Without cookies your experience may not be seamless.

An Experiential Approach to Teaching Creative Writing

- Rosalind Buckton-Tucker

- Duke University Press

- Volume 22, Issue 2, April 2022

- pp. 325-337

- View Citation

Additional Information

Is it possible to teach creative writing? Although creative talent may be innate, all individuals have the capacity to create, and creativity can be nurtured through specific approaches. The works of David Kolb in relation to experiential learning pedagogy are explored and adapted to creative writing courses, and examples of potential exercises are given.

Project MUSE Mission

Project MUSE promotes the creation and dissemination of essential humanities and social science resources through collaboration with libraries, publishers, and scholars worldwide. Forged from a partnership between a university press and a library, Project MUSE is a trusted part of the academic and scholarly community it serves.

2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland, USA 21218

+1 (410) 516-6989 [email protected]

©2024 Project MUSE. Produced by Johns Hopkins University Press in collaboration with The Sheridan Libraries.

Now and Always, The Trusted Content Your Research Requires

Built on the Johns Hopkins University Campus

- Course search

Institute of Continuing Education (ICE)

Please go to students and applicants to login

- Course search overview

Postgraduate Certificate in Teaching Creative Writing

- Courses by subject overview

- Archaeology, Landscape History and Classics

- Biological Sciences

- Business and Entrepreneurship

- Creative Writing and English Literature

- Education Studies and Teaching

- Engineering and Technology

- History overview

- Holocaust Studies

- International Relations and Global Studies

- Leadership and Coaching overview

- Coaching FAQs

- Medicine and Health Sciences

- Philosophy, Ethics and Religion

- History of Art and Visual Culture

- Undergraduate Certificates & Diplomas overview

- Postgraduate Certificates & Diplomas overview

- Applying for a Master of Studies (MSt) or Postgraduate programme

- Part-time Master's Degrees overview

- What is a Master's Degree (MSt)?

- Apprenticeships

- Online Courses

- Career Accelerators overview

- Career Accelerators

- Weekend Courses overview

- Student stories

- Booking terms and conditions

- International Summer Programme overview

- Accommodation overview

- Newnham College

- Queens' College

- Selwyn College

- St Catharine's College

- Evaluation and academic credit

- Language requirements

- Visa guidance

- Make a Donation

- Register your interest

- Creative Writing Retreats

- Gift vouchers for courses overview

- Terms and conditions

- Financial Support overview

- Concessions

- External Funding

- Ways to Pay

- Information for Students overview

- Student login and resources

- Earn your digital badge with Accredible

- Student Support

- Events overview

- Open Days/Weeks overview

- Master's Open Week 2023

- Postgraduate Open Day 2024

- STEM Open Week 2024

- MSt in English Language Assessment Open Session

- Undergraduate Open Day 2024

- Lectures and Talks

- Cultural events

- In Your Own Words: Open Mic

- In Conversation with...

- International Events

- About Us overview

- Our Mission

- Our anniversary

- Academic staff

- Administrative staff

- Student stories overview

- Advanced Diploma

- Archaeology and Landscape History

- Architecture

- Classical Studies

- Creative Writing

- English Literature

- Leadership and Coaching

- Online courses

- Politics and International Studies

- Visual Culture

- Tell us your student story!

- News overview

- Madingley Hall overview

- Make a donation

- Digital Credentials

- Centre for Creative Writing overview

- Creative Writing Mentoring

- BBC Short Story Awards

- Latest News

- How to find us

- The Director's Welcome

This course is not open for online applications. If you would like to enquire about this course please do so using the 'Ask a question' button.

Calling writers who teach, teachers who write, and those interested in applying creative writing (or its theory) within their professional field!

The Postgraduate Certificate in Teaching Creative Writing is structured around 3 modules that are designed with a focus on a different area of teaching creative writing. By the end of the course you will have an enhanced knowledge of relevant existing pedagogical theory, acquired new practical skills for teaching, assessment and planning and you will have developed reflective awareness and innovation in your own teaching practice.

We will be running a Postgraduate Certificate in Teaching Creative Writing Information Session on 15th February at 18:30 GMT as part of our Postgraduate Open Day 2024. Book now .

Watch the recording from our Open Morning on 10 February 2023.

Who is the course designed for ?

The course is aimed at:

- published writers who wish to teach or offer writing workshops;

- existing creative writing tutors who want to improve or develop a more cohesive and defined pedagogy;

- graduates of postgraduate level Creative Writing programmes who wish to become teachers of creative writing;.

- Healthcare or industry professionals who wish to offer creative writing classes;

- professional development for qualified teachers interested in exploring the theory of teaching creative writing or who include creative exercises as part of their teaching of core subjects (eg. History or English).

Aims of the programme

The programme aims to enable participants to:

• develop their skills as a teacher of creative writing and strategies for their intended teaching contexts;

• develop and or extend their knowledge of the theories and practices of the teaching of creative writing;

• develop their repertoire of teaching, course design and assessment methods appropriate to creative writing in their context;

• develop a reflexive and critical awareness of their own teaching practice and to transmit what they have learned from their own experience of being a writer into a classroom setting.

Teaching and Learning

The course is taught over three modules, each of which students must attend. A Virtual Learning Environment (VLE) offers learning support to students while they are on the programme, including learning resources and peer-to-peer and student-to-tutor discussion between modules to build a virtual community of practice.

Module 1: The Philosophy and Context of Teaching Creative Writing

04 - 06 October 2024

This module will introduce students to the Postgraduate Certificate and will address:

- the background and history of teaching creative writing;

- the concept of ‘creativity’ and the arguments surrounding whether or not creative writing can be taught;

- the methodologies surrounding teaching creative writing;

- how teaching creative writing may vary within different settings such as schools, higher education and prisons.

Module 2: Designing a Creative Writing Course

17 - 19 January 2025

This module will address:

- different models of creative writing courses and the advantages and challenges of each;

- the pedagogical theories behind different types of courses;

- the use of close reading in different settings and what makes a good extract;

- the quality assurance aspects of designing a creative writing course;

- the emotional and psychological impact of teaching creative writing for tutors and students.

Module 3: Assessment and Feedback in a Creative Writing Course

04 - 06 April 2025

- different ways of providing feedback in different contexts;

- the pedagogical theories behind different types of feedback;

- the challenges of providing written feedback to a range of students;

- the historical roots of the workshop and its appropriateness in different settings.

You will be awarded a course grade on the basis of a portfolio of three summative assignments totalling 10,000 words.

Please note that this course does not lead to a formal teaching qualification.

Find out more

If you have any questions about this course, would like an informal discussion on academic matters before making your application, or would like to know more about the admissions process, please complete this enquiry form with your questions .

Applicants should hold a good undergraduate degree (good 2.1 or overseas equivalent) and would need to be competent in the English language. There is provision to accept non-standard applicants who do not satisfy the standard academic criterion. Such applicants must produce evidence of relevant and equivalent experience and their suitability for the course.

Language requirement

- IELTS Academic: Overall band score of 7.5 (with a minimum of 7.0 in each individual component)

- CAE: Grade A or B (with at least 193 in each individual element) plus a language centre assessment

- CPE: Grade A, B, or C (with at least 200 in each individual element)

- TOEFL iBT: Overall score of at least 110 with no element below 25

Applicants might come from an existing teaching environment, (primary, secondary or tertiary), be practising writers or postgraduate students who wish to develop the skills to lead workshops, those looking to improve or develop a more cohesive or defined creative writing pedagogy, or professionals in other industries who would like to explore using creative writing as a development tool within their field.

International Students : If you are not a UK resident please visit our international students' page to read about visas for part-time students. Please make sure you have investigated your visa requirements in advance of booking as we cannot offer a refund if you find you are unable to take up the place due to visa constraints after you have booked your place on the course.

The fee will be £4,750.00 for Home and for EU/Overseas students the fee is £8,240.00. Students will be expected to cover the application fee (£50 online), accommodation whilst in Cambridge and any costs of travel to Cambridge.

You can pay in one of two ways:

- In full on enrolment (by cheque payable to the University of Cambridge or by credit or debit card)

- in four instalments (credit/debit card only)

ICE fees and refunds policy

First story - Institute of Continuing Education Tuition Fee Bursary Scheme

The University of Cambridge Institute of Continuing Education (ICE) and the creative writing charity First Story have collaborated to provide four partial tuition fee bursaries for this course. The First Story - Institute of Continuing Education Tuition Fee Bursary Scheme will enable teachers, librarians or other literary professionals working in deprived and/or disadvantaged settings to enrol on the part-time University of Cambridge Postgraduate Certificate in Teaching Creative Writing .

These bursaries, which will cover up to £2000 of the course fee, are intended to support applicants who work in state funded settings such as state schools, public libraries, local authorities, the NHS or HM Prisons Service and will be interested in using creative writing as a development tool within their field. We will also consider applicants from third-sector organisations and not-for-profit organisations. (If you are awarded a bursary you would be responsible for paying the remaining tuition fee.).

How to apply for a bursary

Step one: Apply for a place on the course. Applicants can only apply for a bursary after making an application for the Postgraduate Certificate in Teaching Creative Writing course through the online application portal.

Step two: Complete this online Bursary Application Form . You will be required to provide your course application payment reference number, a personal statement about how you will benefit from the course and bursary, and a copy of your CV.

First Story - Institute of Continuing Education Tuition Fee Bursary Scheme Terms and Conditions .

The deadline for bursary applications is 20 June 2024.

Other sources of funding

Sources of government funding and financial support - including Professional and Career Development Loans.

This course will require a minimum number of students in order to run. Applicants for this course will be notified by September 2024 if the course is not going to be running at which point students will be offered a refund of the fees they have paid so far (please see our Cancellation policy) .

Applications close on the 20th June 2024 and interviews for shortlisted candidates will be held in July. Interviews will take place either in person or by remote software if candidates are unable to attend in person. Candidates will be contacted to arrange convenient times during the previous week.”

Applicants will be required to apply online and will need to provide a CV and a personal statement of around 500 words in addition to:

- Copies of relevant qualification certificates and transcripts

- Language proficiency if required

- Contact details of two referees who will be contacted on your behalf

We welcome learners of all backgrounds and abilities at the Institute of Continuing Education (ICE), and for this reason we have robust learning support in place for any student who needs it.

The Accessibility & Disability Resource Centre (ADRC) provides advice, guidance, and resources to disabled students on ICE award-bearing undergraduate and postgraduate courses.

If you have a disability or medical condition including a mental health condition, then please indicate this on your application form so we can work with you on supporting your studies. If you would like to access support from the ADRC please complete their online Student Information Form as soon as possible. If you are able to, please upload your evidence (written in English) within the Student Information Form where prompted. The following links to guidance on medical evidence or diagnostic evidence will help to answer any questions you may have.

If you have any questions concerning disability support then please contact the ADRC NMS team via [email protected] or view their website via https://www.disability.admin.cam.ac.uk/non-matriculated-students

You can also disclose a disability at any time during your course by contacting either the ADRC NMS team, or ICE’s Student Support team via [email protected]

Student wellbeing is a key priority at ICE, and we have a dedicated Student Support team who can provide wellbeing support and guidance. Please contact the team via [email protected]

How often does the Postgraduate Certificate run? The Postgraduate Certificate in Teaching Creative Writing course currently has an annual intake.

Is the course taught online, or is it possible to complete the course by distance-learning? This is not a distance-learning course. You will be required to attend teaching sessions in Cambridge.

Are there any sources of funding available? Please view the "Fees and Funding" tab for further details.

How many references are required? We require two references. References need to be submitted from professional e-mail addresses, so please ensure that you enter the relevant details into the online application form.

What kind of references should I provide? We prefer academic references from people who, if at all possible, are able to comment on your writing skills and experience, and your ability to study at Master’s level.

What happens if I am not able to provide academic references? We can accept professional references.

Can I nominate an ICE tutor as my referee? Yes, you may nominate an ICE tutor to act as your referee.

How long should the Personal Statement be? As a guide, we suggest that the Personal Statement is about 500 words in length.

Course dates

Course duration.

Academic Directors, Course Directors and Tutors are subject to change, when necessary.

Qualifications / Credits

Course code.

Institute of Continuing Education Madingley Hall Madingley Cambridge CB23 8AQ

Find us Contact us

Useful information

- Jobs and other opportunities

- Gift vouchers

- Student policies

- Privacy policy

- Data protection policy

- General terms and conditions

Connect with us

© 2024 University of Cambridge

- University A-Z

- Contact the University

- Accessibility

- Freedom of information

Study at Cambridge

- Undergraduate

- Postgraduate

- International students

- Continuing education

- Executive and professional education

- Courses in education

About the University

- How the University and Colleges work

- Visiting the University

- Giving to Cambridge

Research at Cambridge

- Spotlight on...

- About research at Cambridge

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

THE IMPLEMENTATION OF CREATIVE WRITING IN EFL CONTEXT FOR STUDENTS' CREATIVITY

Related Papers

Herri Mulyono

This article documents an English as a foreign language (EFL) classroom writing activity to promote students’ creativity. This classroom writing activity had two main objectives: to provide students with writing exercises that would promote practical use of written English language as a means of communication, and to facilitate students’ creativity in engaging with and solving problems in their social community. A real-world pedagogic writing task was developed to achieve these two objectives. The activity was carried out in a junior secondary school extracurricular program with 16 students from Years 7 and 8. Students’ perceptions of the writing activity were positive, and more importantly, their awareness of social issues in the community improved as students became engaged in meaningful communicative situations in their real social environment.

Bambang Harmanto

Journal of Advocacy, Research and Education

Anastasiia Riabokrys

The article is devoted to the actual problem of teaching creative writing at the English lessons. The value of writing in the process of teaching English language is revealed. The principles and peculiarities of evaluation of creative writing are analyzed. The strategy of choosing methods in teaching creative writing is identified. The benefits of creative writing for learner and teachers are considered.

faridha azmy

This study aims to analysis creative writing poetry in EFL students when creative writing for EFL students will found a lack in writing process. This study belongs to qualitative research with case study approach. This study belongs to qualitative research with case study approach. According to Bogdan and Taylor (1975) in Moleong (2004: 3) qualitative methods is a procedure that produces descriptive data in the form of words written or spoken of people and behaviors that can be observed. This research taken place in Islamic University of Labuhan Batu. There are one classes registered from students of VII semester. The essay question from this study are 1) get inspired in writing poetry, 2) students lack in writing poetry is think about rhyme. So from this study, the researcher will know what are the problem and will know how to solve the problem in this study. This study will useful for English Department student or EFL students. A. Introduction English is a general language for communication. People can use English in every place of the world. English can contribute for people in communicate and interact. English as an international language, get a special attention in every country in this world. English put in a lesson of school, although English not the first or second language in Indonesia. Students who are studying English called EFL students. EFL is English for foreign language also EFL is the teaching of English to people whose first language is not English. English itself has four skills. They are reading, speaking, writing and listening. EFL students' writing can produce a good writing grammatically. Students also can produce a writing with good level of vocabulary. In the other hand, the importantly is students can gain the writing with critical thinking.

Alief Noor Farida