Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- Systematic Review | Definition, Example, & Guide

Systematic Review | Definition, Example & Guide

Published on June 15, 2022 by Shaun Turney . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A systematic review is a type of review that uses repeatable methods to find, select, and synthesize all available evidence. It answers a clearly formulated research question and explicitly states the methods used to arrive at the answer.

They answered the question “What is the effectiveness of probiotics in reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?”

In this context, a probiotic is a health product that contains live microorganisms and is taken by mouth. Eczema is a common skin condition that causes red, itchy skin.

Table of contents

What is a systematic review, systematic review vs. meta-analysis, systematic review vs. literature review, systematic review vs. scoping review, when to conduct a systematic review, pros and cons of systematic reviews, step-by-step example of a systematic review, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about systematic reviews.

A review is an overview of the research that’s already been completed on a topic.

What makes a systematic review different from other types of reviews is that the research methods are designed to reduce bias . The methods are repeatable, and the approach is formal and systematic:

- Formulate a research question

- Develop a protocol

- Search for all relevant studies

- Apply the selection criteria

- Extract the data

- Synthesize the data

- Write and publish a report

Although multiple sets of guidelines exist, the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews is among the most widely used. It provides detailed guidelines on how to complete each step of the systematic review process.

Systematic reviews are most commonly used in medical and public health research, but they can also be found in other disciplines.

Systematic reviews typically answer their research question by synthesizing all available evidence and evaluating the quality of the evidence. Synthesizing means bringing together different information to tell a single, cohesive story. The synthesis can be narrative ( qualitative ), quantitative , or both.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Systematic reviews often quantitatively synthesize the evidence using a meta-analysis . A meta-analysis is a statistical analysis, not a type of review.

A meta-analysis is a technique to synthesize results from multiple studies. It’s a statistical analysis that combines the results of two or more studies, usually to estimate an effect size .

A literature review is a type of review that uses a less systematic and formal approach than a systematic review. Typically, an expert in a topic will qualitatively summarize and evaluate previous work, without using a formal, explicit method.

Although literature reviews are often less time-consuming and can be insightful or helpful, they have a higher risk of bias and are less transparent than systematic reviews.

Similar to a systematic review, a scoping review is a type of review that tries to minimize bias by using transparent and repeatable methods.

However, a scoping review isn’t a type of systematic review. The most important difference is the goal: rather than answering a specific question, a scoping review explores a topic. The researcher tries to identify the main concepts, theories, and evidence, as well as gaps in the current research.

Sometimes scoping reviews are an exploratory preparation step for a systematic review, and sometimes they are a standalone project.

A systematic review is a good choice of review if you want to answer a question about the effectiveness of an intervention , such as a medical treatment.

To conduct a systematic review, you’ll need the following:

- A precise question , usually about the effectiveness of an intervention. The question needs to be about a topic that’s previously been studied by multiple researchers. If there’s no previous research, there’s nothing to review.

- If you’re doing a systematic review on your own (e.g., for a research paper or thesis ), you should take appropriate measures to ensure the validity and reliability of your research.

- Access to databases and journal archives. Often, your educational institution provides you with access.

- Time. A professional systematic review is a time-consuming process: it will take the lead author about six months of full-time work. If you’re a student, you should narrow the scope of your systematic review and stick to a tight schedule.

- Bibliographic, word-processing, spreadsheet, and statistical software . For example, you could use EndNote, Microsoft Word, Excel, and SPSS.

A systematic review has many pros .

- They minimize research bias by considering all available evidence and evaluating each study for bias.

- Their methods are transparent , so they can be scrutinized by others.

- They’re thorough : they summarize all available evidence.

- They can be replicated and updated by others.

Systematic reviews also have a few cons .

- They’re time-consuming .

- They’re narrow in scope : they only answer the precise research question.

The 7 steps for conducting a systematic review are explained with an example.

Step 1: Formulate a research question

Formulating the research question is probably the most important step of a systematic review. A clear research question will:

- Allow you to more effectively communicate your research to other researchers and practitioners

- Guide your decisions as you plan and conduct your systematic review

A good research question for a systematic review has four components, which you can remember with the acronym PICO :

- Population(s) or problem(s)

- Intervention(s)

- Comparison(s)

You can rearrange these four components to write your research question:

- What is the effectiveness of I versus C for O in P ?

Sometimes, you may want to include a fifth component, the type of study design . In this case, the acronym is PICOT .

- Type of study design(s)

- The population of patients with eczema

- The intervention of probiotics

- In comparison to no treatment, placebo , or non-probiotic treatment

- The outcome of changes in participant-, parent-, and doctor-rated symptoms of eczema and quality of life

- Randomized control trials, a type of study design

Their research question was:

- What is the effectiveness of probiotics versus no treatment, a placebo, or a non-probiotic treatment for reducing eczema symptoms and improving quality of life in patients with eczema?

Step 2: Develop a protocol

A protocol is a document that contains your research plan for the systematic review. This is an important step because having a plan allows you to work more efficiently and reduces bias.

Your protocol should include the following components:

- Background information : Provide the context of the research question, including why it’s important.

- Research objective (s) : Rephrase your research question as an objective.

- Selection criteria: State how you’ll decide which studies to include or exclude from your review.

- Search strategy: Discuss your plan for finding studies.

- Analysis: Explain what information you’ll collect from the studies and how you’ll synthesize the data.

If you’re a professional seeking to publish your review, it’s a good idea to bring together an advisory committee . This is a group of about six people who have experience in the topic you’re researching. They can help you make decisions about your protocol.

It’s highly recommended to register your protocol. Registering your protocol means submitting it to a database such as PROSPERO or ClinicalTrials.gov .

Step 3: Search for all relevant studies

Searching for relevant studies is the most time-consuming step of a systematic review.

To reduce bias, it’s important to search for relevant studies very thoroughly. Your strategy will depend on your field and your research question, but sources generally fall into these four categories:

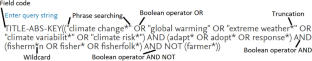

- Databases: Search multiple databases of peer-reviewed literature, such as PubMed or Scopus . Think carefully about how to phrase your search terms and include multiple synonyms of each word. Use Boolean operators if relevant.

- Handsearching: In addition to searching the primary sources using databases, you’ll also need to search manually. One strategy is to scan relevant journals or conference proceedings. Another strategy is to scan the reference lists of relevant studies.

- Gray literature: Gray literature includes documents produced by governments, universities, and other institutions that aren’t published by traditional publishers. Graduate student theses are an important type of gray literature, which you can search using the Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (NDLTD) . In medicine, clinical trial registries are another important type of gray literature.

- Experts: Contact experts in the field to ask if they have unpublished studies that should be included in your review.

At this stage of your review, you won’t read the articles yet. Simply save any potentially relevant citations using bibliographic software, such as Scribbr’s APA or MLA Generator .

- Databases: EMBASE, PsycINFO, AMED, LILACS, and ISI Web of Science

- Handsearch: Conference proceedings and reference lists of articles

- Gray literature: The Cochrane Library, the metaRegister of Controlled Trials, and the Ongoing Skin Trials Register

- Experts: Authors of unpublished registered trials, pharmaceutical companies, and manufacturers of probiotics

Step 4: Apply the selection criteria

Applying the selection criteria is a three-person job. Two of you will independently read the studies and decide which to include in your review based on the selection criteria you established in your protocol . The third person’s job is to break any ties.

To increase inter-rater reliability , ensure that everyone thoroughly understands the selection criteria before you begin.

If you’re writing a systematic review as a student for an assignment, you might not have a team. In this case, you’ll have to apply the selection criteria on your own; you can mention this as a limitation in your paper’s discussion.

You should apply the selection criteria in two phases:

- Based on the titles and abstracts : Decide whether each article potentially meets the selection criteria based on the information provided in the abstracts.

- Based on the full texts: Download the articles that weren’t excluded during the first phase. If an article isn’t available online or through your library, you may need to contact the authors to ask for a copy. Read the articles and decide which articles meet the selection criteria.

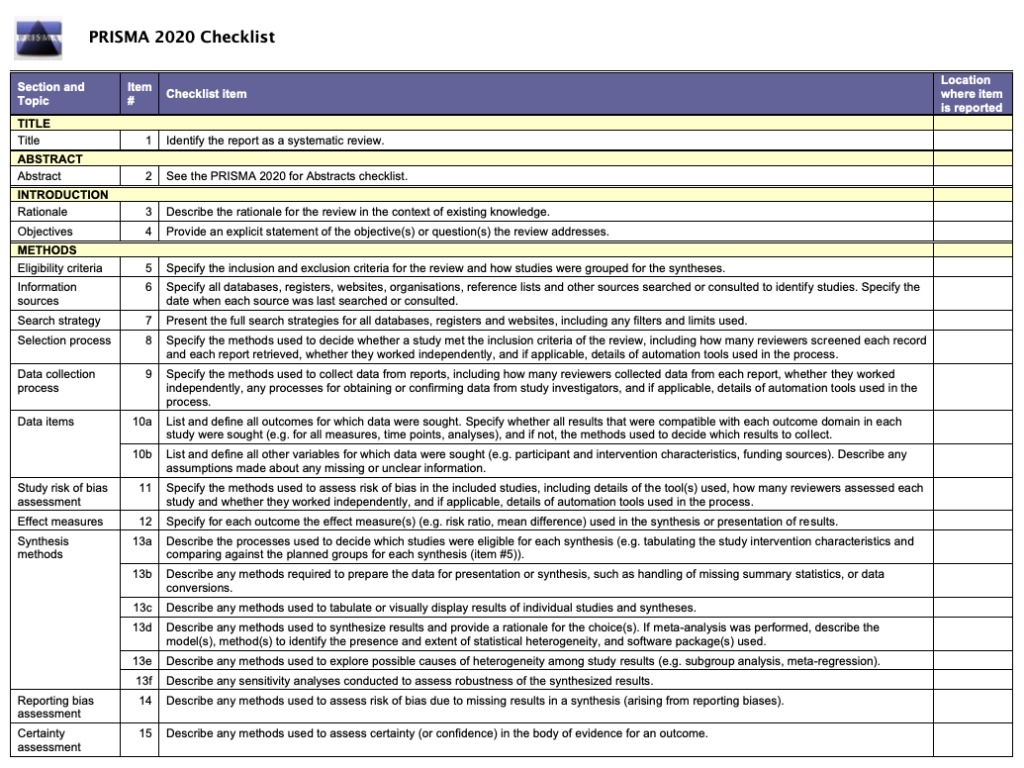

It’s very important to keep a meticulous record of why you included or excluded each article. When the selection process is complete, you can summarize what you did using a PRISMA flow diagram .

Next, Boyle and colleagues found the full texts for each of the remaining studies. Boyle and Tang read through the articles to decide if any more studies needed to be excluded based on the selection criteria.

When Boyle and Tang disagreed about whether a study should be excluded, they discussed it with Varigos until the three researchers came to an agreement.

Step 5: Extract the data

Extracting the data means collecting information from the selected studies in a systematic way. There are two types of information you need to collect from each study:

- Information about the study’s methods and results . The exact information will depend on your research question, but it might include the year, study design , sample size, context, research findings , and conclusions. If any data are missing, you’ll need to contact the study’s authors.

- Your judgment of the quality of the evidence, including risk of bias .

You should collect this information using forms. You can find sample forms in The Registry of Methods and Tools for Evidence-Informed Decision Making and the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations Working Group .

Extracting the data is also a three-person job. Two people should do this step independently, and the third person will resolve any disagreements.

They also collected data about possible sources of bias, such as how the study participants were randomized into the control and treatment groups.

Step 6: Synthesize the data

Synthesizing the data means bringing together the information you collected into a single, cohesive story. There are two main approaches to synthesizing the data:

- Narrative ( qualitative ): Summarize the information in words. You’ll need to discuss the studies and assess their overall quality.

- Quantitative : Use statistical methods to summarize and compare data from different studies. The most common quantitative approach is a meta-analysis , which allows you to combine results from multiple studies into a summary result.

Generally, you should use both approaches together whenever possible. If you don’t have enough data, or the data from different studies aren’t comparable, then you can take just a narrative approach. However, you should justify why a quantitative approach wasn’t possible.

Boyle and colleagues also divided the studies into subgroups, such as studies about babies, children, and adults, and analyzed the effect sizes within each group.

Step 7: Write and publish a report

The purpose of writing a systematic review article is to share the answer to your research question and explain how you arrived at this answer.

Your article should include the following sections:

- Abstract : A summary of the review

- Introduction : Including the rationale and objectives

- Methods : Including the selection criteria, search method, data extraction method, and synthesis method

- Results : Including results of the search and selection process, study characteristics, risk of bias in the studies, and synthesis results

- Discussion : Including interpretation of the results and limitations of the review

- Conclusion : The answer to your research question and implications for practice, policy, or research

To verify that your report includes everything it needs, you can use the PRISMA checklist .

Once your report is written, you can publish it in a systematic review database, such as the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews , and/or in a peer-reviewed journal.

In their report, Boyle and colleagues concluded that probiotics cannot be recommended for reducing eczema symptoms or improving quality of life in patients with eczema. Note Generative AI tools like ChatGPT can be useful at various stages of the writing and research process and can help you to write your systematic review. However, we strongly advise against trying to pass AI-generated text off as your own work.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

A systematic review is secondary research because it uses existing research. You don’t collect new data yourself.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Turney, S. (2023, November 20). Systematic Review | Definition, Example & Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved August 21, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/systematic-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shaun Turney

Other students also liked, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, what is critical thinking | definition & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

How to Do a Systematic Review: A Best Practice Guide for Conducting and Reporting Narrative Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-Syntheses

Affiliations.

- 1 Behavioural Science Centre, Stirling Management School, University of Stirling, Stirling FK9 4LA, United Kingdom; email: [email protected].

- 2 Department of Psychological and Behavioural Science, London School of Economics and Political Science, London WC2A 2AE, United Kingdom.

- 3 Department of Statistics, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, USA; email: [email protected].

- PMID: 30089228

- DOI: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

Systematic reviews are characterized by a methodical and replicable methodology and presentation. They involve a comprehensive search to locate all relevant published and unpublished work on a subject; a systematic integration of search results; and a critique of the extent, nature, and quality of evidence in relation to a particular research question. The best reviews synthesize studies to draw broad theoretical conclusions about what a literature means, linking theory to evidence and evidence to theory. This guide describes how to plan, conduct, organize, and present a systematic review of quantitative (meta-analysis) or qualitative (narrative review, meta-synthesis) information. We outline core standards and principles and describe commonly encountered problems. Although this guide targets psychological scientists, its high level of abstraction makes it potentially relevant to any subject area or discipline. We argue that systematic reviews are a key methodology for clarifying whether and how research findings replicate and for explaining possible inconsistencies, and we call for researchers to conduct systematic reviews to help elucidate whether there is a replication crisis.

Keywords: evidence; guide; meta-analysis; meta-synthesis; narrative; systematic review; theory.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- The future of Cochrane Neonatal. Soll RF, Ovelman C, McGuire W. Soll RF, et al. Early Hum Dev. 2020 Nov;150:105191. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105191. Epub 2020 Sep 12. Early Hum Dev. 2020. PMID: 33036834

- Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey CM, Holly C, Khalil H, Tungpunkom P. Aromataris E, et al. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015 Sep;13(3):132-40. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000055. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015. PMID: 26360830

- RAMESES publication standards: meta-narrative reviews. Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Buckingham J, Pawson R. Wong G, et al. BMC Med. 2013 Jan 29;11:20. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-20. BMC Med. 2013. PMID: 23360661 Free PMC article.

- A Primer on Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Nguyen NH, Singh S. Nguyen NH, et al. Semin Liver Dis. 2018 May;38(2):103-111. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1655776. Epub 2018 Jun 5. Semin Liver Dis. 2018. PMID: 29871017 Review.

- Publication Bias and Nonreporting Found in Majority of Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses in Anesthesiology Journals. Hedin RJ, Umberham BA, Detweiler BN, Kollmorgen L, Vassar M. Hedin RJ, et al. Anesth Analg. 2016 Oct;123(4):1018-25. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001452. Anesth Analg. 2016. PMID: 27537925 Review.

- Bridging disciplines-key to success when implementing planetary health in medical training curricula. Malmqvist E, Oudin A. Malmqvist E, et al. Front Public Health. 2024 Aug 6;12:1454729. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1454729. eCollection 2024. Front Public Health. 2024. PMID: 39165783 Free PMC article. Review.

- Strength of evidence for five happiness strategies. Puterman E, Zieff G, Stoner L. Puterman E, et al. Nat Hum Behav. 2024 Aug 12. doi: 10.1038/s41562-024-01954-0. Online ahead of print. Nat Hum Behav. 2024. PMID: 39134738 No abstract available.

- Nursing Education During the SARS-COVID-19 Pandemic: The Implementation of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT). Soto-Luffi O, Villegas C, Viscardi S, Ulloa-Inostroza EM. Soto-Luffi O, et al. Med Sci Educ. 2024 May 9;34(4):949-959. doi: 10.1007/s40670-024-02056-2. eCollection 2024 Aug. Med Sci Educ. 2024. PMID: 39099870 Review.

- Surveillance of Occupational Exposure to Volatile Organic Compounds at Gas Stations: A Scoping Review Protocol. Mendes TMC, Soares JP, Salvador PTCO, Castro JL. Mendes TMC, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024 Apr 23;21(5):518. doi: 10.3390/ijerph21050518. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024. PMID: 38791733 Free PMC article. Review.

- Association between poor sleep and mental health issues in Indigenous communities across the globe: a systematic review. Fernandez DR, Lee R, Tran N, Jabran DS, King S, McDaid L. Fernandez DR, et al. Sleep Adv. 2024 May 2;5(1):zpae028. doi: 10.1093/sleepadvances/zpae028. eCollection 2024. Sleep Adv. 2024. PMID: 38721053 Free PMC article.

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Ingenta plc

- Ovid Technologies, Inc.

Other Literature Sources

- scite Smart Citations

Miscellaneous

- NCI CPTAC Assay Portal

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- A-Z Publications

Annual Review of Psychology

Volume 70, 2019, review article, how to do a systematic review: a best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses.

- Andy P. Siddaway 1 , Alex M. Wood 2 , and Larry V. Hedges 3

- View Affiliations Hide Affiliations Affiliations: 1 Behavioural Science Centre, Stirling Management School, University of Stirling, Stirling FK9 4LA, United Kingdom; email: [email protected] 2 Department of Psychological and Behavioural Science, London School of Economics and Political Science, London WC2A 2AE, United Kingdom 3 Department of Statistics, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, USA; email: [email protected]

- Vol. 70:747-770 (Volume publication date January 2019) https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102803

- First published as a Review in Advance on August 08, 2018

- Copyright © 2019 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved

Systematic reviews are characterized by a methodical and replicable methodology and presentation. They involve a comprehensive search to locate all relevant published and unpublished work on a subject; a systematic integration of search results; and a critique of the extent, nature, and quality of evidence in relation to a particular research question. The best reviews synthesize studies to draw broad theoretical conclusions about what a literature means, linking theory to evidence and evidence to theory. This guide describes how to plan, conduct, organize, and present a systematic review of quantitative (meta-analysis) or qualitative (narrative review, meta-synthesis) information. We outline core standards and principles and describe commonly encountered problems. Although this guide targets psychological scientists, its high level of abstraction makes it potentially relevant to any subject area or discipline. We argue that systematic reviews are a key methodology for clarifying whether and how research findings replicate and for explaining possible inconsistencies, and we call for researchers to conduct systematic reviews to help elucidate whether there is a replication crisis.

Article metrics loading...

Full text loading...

Literature Cited

- APA Publ. Commun. Board Work. Group J. Artic. Rep. Stand. 2008 . Reporting standards for research in psychology: Why do we need them? What might they be?. Am. Psychol . 63 : 848– 49 [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF 2013 . Writing a literature review. The Portable Mentor: Expert Guide to a Successful Career in Psychology MJ Prinstein, MD Patterson 119– 32 New York: Springer, 2nd ed.. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF , Leary MR 1995 . The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 117 : 497– 529 [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF , Leary MR 1997 . Writing narrative literature reviews. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 3 : 311– 20 Presents a thorough and thoughtful guide to conducting narrative reviews. [Google Scholar]

- Bem DJ 1995 . Writing a review article for Psychological Bulletin. Psychol . Bull 118 : 172– 77 [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M , Hedges LV , Higgins JPT , Rothstein HR 2009 . Introduction to Meta-Analysis New York: Wiley Presents a comprehensive introduction to meta-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M , Higgins JPT , Hedges LV , Rothstein HR 2017 . Basics of meta-analysis: I 2 is not an absolute measure of heterogeneity. Res. Synth. Methods 8 : 5– 18 [Google Scholar]

- Braver SL , Thoemmes FJ , Rosenthal R 2014 . Continuously cumulating meta-analysis and replicability. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9 : 333– 42 [Google Scholar]

- Bushman BJ 1994 . Vote-counting procedures. The Handbook of Research Synthesis H Cooper, LV Hedges 193– 214 New York: Russell Sage Found. [Google Scholar]

- Cesario J 2014 . Priming, replication, and the hardest science. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9 : 40– 48 [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers I 2007 . The lethal consequences of failing to make use of all relevant evidence about the effects of medical treatments: the importance of systematic reviews. Treating Individuals: From Randomised Trials to Personalised Medicine PM Rothwell 37– 58 London: Lancet [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane Collab. 2003 . Glossary Rep., Cochrane Collab. London: http://community.cochrane.org/glossary Presents a comprehensive glossary of terms relevant to systematic reviews. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn LD , Becker BJ 2003 . How meta-analysis increases statistical power. Psychol. Methods 8 : 243– 53 [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HM 2003 . Editorial. Psychol. Bull. 129 : 3– 9 [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HM 2016 . Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis: A Step-by-Step Approach Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 5th ed.. Presents a comprehensive introduction to research synthesis and meta-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HM , Hedges LV , Valentine JC 2009 . The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis New York: Russell Sage Found, 2nd ed.. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming G 2014 . The new statistics: why and how. Psychol. Sci. 25 : 7– 29 Discusses the limitations of null hypothesis significance testing and viable alternative approaches. [Google Scholar]

- Earp BD , Trafimow D 2015 . Replication, falsification, and the crisis of confidence in social psychology. Front. Psychol. 6 : 621 [Google Scholar]

- Etz A , Vandekerckhove J 2016 . A Bayesian perspective on the reproducibility project: psychology. PLOS ONE 11 : e0149794 [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson CJ , Brannick MT 2012 . Publication bias in psychological science: prevalence, methods for identifying and controlling, and implications for the use of meta-analyses. Psychol. Methods 17 : 120– 28 [Google Scholar]

- Fleiss JL , Berlin JA 2009 . Effect sizes for dichotomous data. The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis H Cooper, LV Hedges, JC Valentine 237– 53 New York: Russell Sage Found, 2nd ed.. [Google Scholar]

- Garside R 2014 . Should we appraise the quality of qualitative research reports for systematic reviews, and if so, how. Innovation 27 : 67– 79 [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV , Olkin I 1980 . Vote count methods in research synthesis. Psychol. Bull. 88 : 359– 69 [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV , Pigott TD 2001 . The power of statistical tests in meta-analysis. Psychol. Methods 6 : 203– 17 [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT , Green S 2011 . Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0 London: Cochrane Collab. Presents comprehensive and regularly updated guidelines on systematic reviews. [Google Scholar]

- John LK , Loewenstein G , Prelec D 2012 . Measuring the prevalence of questionable research practices with incentives for truth telling. Psychol. Sci. 23 : 524– 32 [Google Scholar]

- Juni P , Witschi A , Bloch R , Egger M 1999 . The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta-analysis. JAMA 282 : 1054– 60 [Google Scholar]

- Klein O , Doyen S , Leys C , Magalhães de Saldanha da Gama PA , Miller S et al. 2012 . Low hopes, high expectations: expectancy effects and the replicability of behavioral experiments. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 7 : 6 572– 84 [Google Scholar]

- Lau J , Antman EM , Jimenez-Silva J , Kupelnick B , Mosteller F , Chalmers TC 1992 . Cumulative meta-analysis of therapeutic trials for myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 327 : 248– 54 [Google Scholar]

- Light RJ , Smith PV 1971 . Accumulating evidence: procedures for resolving contradictions among different research studies. Harvard Educ. Rev. 41 : 429– 71 [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW , Wilson D 2001 . Practical Meta-Analysis London: Sage Comprehensive and clear explanation of meta-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Matt GE , Cook TD 1994 . Threats to the validity of research synthesis. The Handbook of Research Synthesis H Cooper, LV Hedges 503– 20 New York: Russell Sage Found. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SE , Lau MY , Howard GS 2015 . Is psychology suffering from a replication crisis? What does “failure to replicate” really mean?. Am. Psychol. 70 : 487– 98 [Google Scholar]

- Moher D , Hopewell S , Schulz KF , Montori V , Gøtzsche PC et al. 2010 . CONSORT explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 340 : c869 [Google Scholar]

- Moher D , Liberati A , Tetzlaff J , Altman DG PRISMA Group. 2009 . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339 : 332– 36 Comprehensive reporting guidelines for systematic reviews. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison A , Polisena J , Husereau D , Moulton K , Clark M et al. 2012 . The effect of English-language restriction on systematic review-based meta-analyses: a systematic review of empirical studies. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 28 : 138– 44 [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LD , Simmons J , Simonsohn U 2018 . Psychology's renaissance. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 69 : 511– 34 [Google Scholar]

- Noblit GW , Hare RD 1988 . Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies Newbury Park, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- Olivo SA , Macedo LG , Gadotti IC , Fuentes J , Stanton T , Magee DJ 2008 . Scales to assess the quality of randomized controlled trials: a systematic review. Phys. Ther. 88 : 156– 75 [Google Scholar]

- Open Sci. Collab. 2015 . Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science 349 : 943 [Google Scholar]

- Paterson BL , Thorne SE , Canam C , Jillings C 2001 . Meta-Study of Qualitative Health Research: A Practical Guide to Meta-Analysis and Meta-Synthesis Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- Patil P , Peng RD , Leek JT 2016 . What should researchers expect when they replicate studies? A statistical view of replicability in psychological science. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 11 : 539– 44 [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R 1979 . The “file drawer problem” and tolerance for null results. Psychol. Bull. 86 : 638– 41 [Google Scholar]

- Rosnow RL , Rosenthal R 1989 . Statistical procedures and the justification of knowledge in psychological science. Am. Psychol. 44 : 1276– 84 [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson S , Tatt ID , Higgins JP 2007 . Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: a systematic review and annotated bibliography. Int. J. Epidemiol. 36 : 666– 76 [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber R , Crooks D , Stern PN 1997 . Qualitative meta-analysis. Completing a Qualitative Project: Details and Dialogue JM Morse 311– 26 Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE , Rodgers JL 2018 . Psychology, science, and knowledge construction: broadening perspectives from the replication crisis. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 69 : 487– 510 [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe W , Strack F 2014 . The alleged crisis and the illusion of exact replication. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 9 : 59– 71 [Google Scholar]

- Stroup DF , Berlin JA , Morton SC , Olkin I , Williamson GD et al. 2000 . Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE): a proposal for reporting. JAMA 283 : 2008– 12 [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S , Jensen L , Kearney MH , Noblit G , Sandelowski M 2004 . Qualitative meta-synthesis: reflections on methodological orientation and ideological agenda. Qual. Health Res. 14 : 1342– 65 [Google Scholar]

- Tong A , Flemming K , McInnes E , Oliver S , Craig J 2012 . Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 12 : 181– 88 [Google Scholar]

- Trickey D , Siddaway AP , Meiser-Stedman R , Serpell L , Field AP 2012 . A meta-analysis of risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 32 : 122– 38 [Google Scholar]

- Valentine JC , Biglan A , Boruch RF , Castro FG , Collins LM et al. 2011 . Replication in prevention science. Prev. Sci. 12 : 103– 17 [Google Scholar]

- Article Type: Review Article

Most Read This Month

Most cited most cited rss feed, job burnout, executive functions, social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective, on happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being, sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it, mediation analysis, missing data analysis: making it work in the real world, grounded cognition, personality structure: emergence of the five-factor model, motivational beliefs, values, and goals.

Covidence website will be inaccessible as we upgrading our platform on Monday 23rd August at 10am AEST, / 2am CEST/1am BST (Sunday, 15th August 8pm EDT/5pm PDT)

How to write the methods section of a systematic review

Home | Blog | How To | How to write the methods section of a systematic review

Covidence breaks down how to write a methods section

The methods section of your systematic review describes what you did, how you did it, and why. Readers need this information to interpret the results and conclusions of the review. Often, a lot of information needs to be distilled into just a few paragraphs. This can be a challenging task, but good preparation and the right tools will help you to set off in the right direction 🗺️🧭.

Systematic reviews are so-called because they are conducted in a way that is rigorous and replicable. So it’s important that these methods are reported in a way that is thorough, clear, and easy to navigate for the reader – whether that’s a patient, a healthcare worker, or a researcher.

Like most things in a systematic review, the methods should be planned upfront and ideally described in detail in a project plan or protocol. Reviews of healthcare interventions follow the PRISMA guidelines for the minimum set of items to report in the methods section. But what else should be included? It’s a good idea to consider what readers will want to know about the review methods and whether the journal you’re planning to submit the work to has expectations on the reporting of methods. Finding out in advance will help you to plan what to include.

Describe what happened

While the research plan sets out what you intend to do, the methods section is a write-up of what actually happened. It’s not a simple case of rewriting the plan in the past tense – you will also need to discuss and justify deviations from the plan and describe the handling of issues that were unforeseen at the time the plan was written. For this reason, it is useful to make detailed notes before, during, and after the review is completed. Relying on memory alone risks losing valuable information and trawling through emails when the deadline is looming can be frustrating and time consuming!

Keep it brief

The methods section should be succinct but include all the noteworthy information. This can be a difficult balance to achieve. A useful strategy is to aim for a brief description that signposts the reader to a separate section or sections of supporting information. This could include datasets, a flowchart to show what happened to the excluded studies, a collection of search strategies, and tables containing detailed information about the studies.This separation keeps the review short and simple while enabling the reader to drill down to the detail as needed. And if the methods follow a well-known or standard process, it might suffice to say so and give a reference, rather than describe the process at length.

Follow a structure

A clear structure provides focus. Use of descriptive headings keeps the writing on track and helps the reader get to key information quickly. What should the structure of the methods section look like? As always, a lot depends on the type of review but it will certainly contain information relating to the following areas:

- Selection criteria ⭕

- Data collection and analysis 👩💻

- Study quality and risk of bias ⚖️

Let’s look at each of these in turn.

1. Selection criteria ⭕

The criteria for including and excluding studies are listed here. This includes detail about the types of studies, the types of participants, the types of interventions and the types of outcomes and how they were measured.

2. Search 🕵🏾♀️

Comprehensive reporting of the search is important because this means it can be evaluated and replicated. The search strategies are included in the review, along with details of the databases searched. It’s also important to list any restrictions on the search (for example, language), describe how resources other than electronic databases were searched (for example, non-indexed journals), and give the date that the searches were run. The PRISMA-S extension provides guidance on reporting literature searches.

Systematic reviewer pro-tip:

Copy and paste the search strategy to avoid introducing typos

3. Data collection and analysis 👩💻

This section describes:

- how studies were selected for inclusion in the review

- how study data were extracted from the study reports

- how study data were combined for analysis and synthesis

To describe how studies were selected for inclusion , review teams outline the screening process. Covidence uses reviewers’ decision data to automatically populate a PRISMA flow diagram for this purpose. Covidence can also calculate Cohen’s kappa to enable review teams to report the level of agreement among individual reviewers during screening.

To describe how study data were extracted from the study reports , reviewers outline the form that was used, any pilot-testing that was done, and the items that were extracted from the included studies. An important piece of information to include here is the process used to resolve conflict among the reviewers. Covidence’s data extraction tool saves reviewers’ comments and notes in the system as they work. This keeps the information in one place for easy retrieval ⚡.

To describe how study data were combined for analysis and synthesis, reviewers outline the type of synthesis (narrative or quantitative, for example), the methods for grouping data, the challenges that came up, and how these were dealt with. If the review includes a meta-analysis, it will detail how this was performed and how the treatment effects were measured.

4. Study quality and risk of bias ⚖️

Because the results of systematic reviews can be affected by many types of bias, reviewers make every effort to minimise it and to show the reader that the methods they used were appropriate. This section describes the methods used to assess study quality and an assessment of the risk of bias across a range of domains.

Steps to assess the risk of bias in studies include looking at how study participants were assigned to treatment groups and whether patients and/or study assessors were blinded to the treatment given. Reviewers also report their assessment of the risk of bias due to missing outcome data, whether that is due to participant drop-out or non-reporting of the outcomes by the study authors.

Covidence’s default template for assessing study quality is Cochrane’s risk of bias tool but it is also possible to start from scratch and build a tool with a set of custom domains if you prefer.

Careful planning, clear writing, and a structured approach are key to a good methods section. A methodologist will be able to refer review teams to examples of good methods reporting in the literature. Covidence helps reviewers to screen references, extract data and complete risk of bias tables quickly and efficiently. Sign up for a free trial today!

Laura Mellor. Portsmouth, UK

Perhaps you'd also like....

Top 5 Tips for High-Quality Systematic Review Data Extraction

Data extraction can be a complex step in the systematic review process. Here are 5 top tips from our experts to help prepare and achieve high quality data extraction.

How to get through study quality assessment Systematic Review

Find out 5 tops tips to conducting quality assessment and why it’s an important step in the systematic review process.

How to extract study data for your systematic review

Learn the basic process and some tips to build data extraction forms for your systematic review with Covidence.

Better systematic review management

Head office, working for an institution or organisation.

Find out why over 350 of the world’s leading institutions are seeing a surge in publications since using Covidence!

Request a consultation with one of our team members and start empowering your researchers:

By using our site you consent to our use of cookies to measure and improve our site’s performance. Please see our Privacy Policy for more information.

What is a Systematic Literature Review?

A systematic literature review (SLR) is an independent academic method that aims to identify and evaluate all relevant literature on a topic in order to derive conclusions about the question under consideration. "Systematic reviews are undertaken to clarify the state of existing research and the implications that should be drawn from this." (Feak & Swales, 2009, p. 3) An SLR can demonstrate the current state of research on a topic, while identifying gaps and areas requiring further research with regard to a given research question. A formal methodological approach is pursued in order to reduce distortions caused by an overly restrictive selection of the available literature and to increase the reliability of the literature selected (Tranfield, Denyer & Smart, 2003). A special aspect in this regard is the fact that a research objective is defined for the search itself and the criteria for determining what is to be included and excluded are defined prior to conducting the search. The search is mainly performed in electronic literature databases (such as Business Source Complete or Web of Science), but also includes manual searches (reviews of reference lists in relevant sources) and the identification of literature not yet published in order to obtain a comprehensive overview of a research topic.

An SLR protocol documents all the information gathered and the steps taken as part of an SLR in order to make the selection process transparent and reproducible. The PRISMA flow-diagram support you in making the selection process visible.

In an ideal scenario, experts from the respective research discipline, as well as experts working in the relevant field and in libraries, should be involved in setting the search terms . As a rule, the literature is selected by two or more reviewers working independently of one another. Both measures serve the purpose of increasing the objectivity of the literature selection. An SLR must, then, be more than merely a summary of a topic (Briner & Denyer, 2012). As such, it also distinguishes itself from “ordinary” surveys of the available literature. The following table shows the differences between an SLR and an “ordinary” literature review.

- Charts of BSWL workshop (pdf, 2.88 MB)

- Listen to the interview (mp4, 12.35 MB)

Differences to "common" literature reviews

| Characteristic | SLR | common literature overview |

|---|---|---|

| Independent research method | yes | no |

| Explicit formulation of the search objectives | yes | no |

| Identification of all publications on a topic | yes | no |

| Defined criteria for inclusion and exclusion of publications | yes | no |

| Description of search procedure | yes | no |

| Literature selection and information extraction by several persons | yes | no |

| Transparent quality evaluation of publications | yes | no |

What are the objectives of SLRs?

- Avoidance of research redundancies despite a growing amount of publications

- Identification of research areas, gaps and methods

- Input for evidence-based management, which allows to base management decisions on scientific methods and findings

- Identification of links between different areas of researc

Process steps of an SLR

A SLR has several process steps which are defined differently in the literature (Fink 2014, p. 4; Guba 2008, Transfield et al. 2003). We distinguish the following steps which are adapted to the economics and management research area:

1. Defining research questions

Briner & Denyer (2009, p. 347ff.) have developed the CIMO scheme to establish clearly formulated and answerable research questions in the field of economic sciences:

C – CONTEXT: Which individuals, relationships, institutional frameworks and systems are being investigated?

I – Intervention: The effects of which event, action or activity are being investigated?

M – Mechanisms: Which mechanisms can explain the relationship between interventions and results? Under what conditions do these mechanisms take effect?

O – Outcomes: What are the effects of the intervention? How are the results measured? What are intended and unintended effects?

The objective of the systematic literature review is used to formulate research questions such as “How can a project team be led effectively?”. Since there are numerous interpretations and constructs for “effective”, “leadership” and “project team”, these terms must be particularized.

With the aid of the scheme, the following concrete research questions can be derived with regard to this example:

Under what conditions (C) does leadership style (I) influence the performance of project teams (O)?

Which constructs have an effect upon the influence of leadership style (I) on a project team’s performance (O)?

Research questions do not necessarily need to follow the CIMO scheme, but they should:

- ... be formulated in a clear, focused and comprehensible manner and be answerable;

- ... have been determined prior to carrying out the SLR;

- ... consist of general and specific questions.

As early as this stage, the criteria for inclusion and exclusion are also defined. The selection of the criteria must be well-grounded. This may include conceptual factors such as a geographical or temporal restrictions, congruent definitions of constructs, as well as quality criteria (journal impact factor > x).

2. Selecting databases and other research sources

The selection of sources must be described and explained in detail. The aim is to find a balance between the relevance of the sources (content-related fit) and the scope of the sources.

In the field of economic sciences, there are a number of literature databases that can be searched as part of an SLR. Some examples in this regard are:

- Business Source Complete

- ProQuest One Business

- EconBiz

Our video " Selecting the right databases " explains how to find relevant databases for your topic.

Literature databases are an important source of research for SLRs, as they can minimize distortions caused by an individual literature selection (selection bias), while offering advantages for a systematic search due to their data structure. The aim is to find all database entries on a topic and thus keep the retrieval bias low (tutorial on retrieval bias ). Besides articles from scientific journals, it is important to inlcude working papers, conference proceedings, etc to reduce the publication bias ( tutorial on publication bias ).

Our online self-study course " Searching economic databases " explains step 2 und 3.

3. Defining search terms

Once the literature databases and other research sources have been selected, search terms are defined. For this purpose, the research topic/questions is/are divided into blocks of terms of equal ranking. This approach is called the block-building method (Guba 2008, p. 63). The so-called document-term matrix, which lists topic blocks and search terms according to a scheme, is helpful in this regard. The aim is to identify as many different synonyms as possible for the partial terms. A precisely formulated research question facilitates the identification of relevant search terms. In addition, keywords from particularly relevant articles support the formulation of search terms.

A document-term matrix for the topic “The influence of management style on the performance of project teams” is shown in this example .

Identification of headwords and keywords

When setting search terms, a distinction must be made between subject headings and keywords, both of which are described below:

- appear in the title, abstract and/or text

- sometimes specified by the author, but in most cases automatically generated

- non-standardized

- different spellings and forms (singular/plural) must be searched separately

Subject headings

- describe the content

- are generated by an editorial team

- are listed in a standardized list (thesaurus)

- may comprise various keywords

- include different spellings

- database-specific

Subject headings are a standardized list of words that are generated by the specialists in charge of some databases. This so-called index of subject headings (thesaurus) helps searchers find relevant articles, since the headwords indicate the content of a publication. By contrast, an ordinary keyword search does not necessarily result in a content-related fit, since the database also displays articles in which, for example, a word appears once in the abstract, even though the article’s content does not cover the topic.

Nevertheless, searches using both headwords and keywords should be conducted, since some articles may not yet have been assigned headwords, or errors may have occurred during the assignment of headwords.

To add headwords to your search in the Business Source Complete database, please select the Thesaurus tab at the top. Here you can find headwords in a new search field and integrate them into your search query. In the search history, headwords are marked with the addition DE (descriptor).

The EconBiz database of the German National Library of Economics (ZBW – Leibniz Information Centre for Economics), which also contains German-language literature, has created its own index of subject headings with the STW Thesaurus for Economics . Headwords are integrated into the search by being used in the search query.

Since the indexes of subject headings divide terms into synonyms, generic terms and sub-aspects, they facilitate the creation of a document-term matrix. For this purpose it is advisable to specify in the document-term matrix the origin of the search terms (STW Thesaurus for Economics, Business Source Complete, etc.).

Searching in literature databases

Once the document-term matrix has been defined, the search in literature databases begins. It is recommended to enter each word of the document-term matrix individually into the database in order to obtain a good overview of the number of hits per word. Finally, all the words contained in a block of terms are linked with the Boolean operator OR and thereby a union of all the words is formed. The latter are then linked with each other using the Boolean operator AND. In doing so, each block should be added individually in order to see to what degree the number of hits decreases.

Since the search query must be set up separately for each database, tools such as LitSonar have been developed to enable a systematic search across different databases. LitSonar was created by Professor Dr. Ali Sunyaev (Institute of Applied Informatics and Formal Description Methods – AIFB) at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology.

Advanced search

Certain database-specific commands can be used to refine a search, for example, by taking variable word endings into account (*) or specifying the distance between two words, etc. Our overview shows the most important search commands for our top databases.

Additional searches in sources other than literature databases

In addition to literature databases, other sources should also be searched. Fink (2014, p. 27) lists the following reasons for this:

- the topic is new and not yet included in indexes of subject headings;

- search terms are not used congruently in articles because uniform definitions do not exist;

- some studies are still in the process of being published, or have been completed, but not published.

Therefore, further search strategies are manual search, bibliographic analysis, personal contacts and academic networks (Briner & Denyer, p. 349). Manual search means that you go through the source information of relevant articles and supplement your hit list accordingly. In addition, you should conduct a targeted search for so-called gray literature, that is, literature not distributed via the book trade, such as working papers from specialist areas and conference reports. By including different types of publications, the so-called publication bias (DBWM video “Understanding publication bias” ) – that is, distortions due to exclusive use of articles from peer-reviewed journals – should be kept to a minimum.

The PRESS-Checklist can support you to check the correctness of your search terms.

4. Merging hits from different databases

In principle, large amounts of data can be easily collected, structured and sorted with data processing programs such as Excel. Another option is to use reference management programs such as EndNote, Citavi or Zotero. The Saxon State and University Library Dresden (SLUB Dresden) provides an overview of current reference management programs . Software for qualitative data analysis such as NVivo is equally suited for data processing. A comprehensive overview of the features of different tools that support the SLR process can be found in Bandara et al. (2015).

Our online-self study course "Managing literature with Citavi" shows you how to use the reference management software Citavi.

When conducting an SLR, you should specify for each hit the database from which it originates and the date on which the query was made. In addition, you should always indicate how many hits you have identified in the various databases or, for example, by manual search.

Exporting data from literature databases

Exporting from literature databases is very easy. In Business Source Complete , you must first click on the “Share” button in the hit list, then “Email a link to download exported results” at the very bottom and then select the appropriate format for the respective literature program.

Exporting data from the literature database EconBiz is somewhat more complex. Here you must first create a marked list and then select each hit individually and add it to the marked list. Afterwards, articles on the list can be exported.

After merging all hits from the various databases, duplicate entries (duplicates) are deleted.

5. Applying inclusion and exclusion criteria

All publications are evaluated in the literature management program applying the previously defined criteria for inclusion and exclusion. Only those sources that survive this selection process will subsequently be analyzed. The review process and inclusion criteria should be tested with a small sample and adjustments made if necessary before applying it to all articles. In the ideal case, even this selection would be carried out by more than one person, with each working independently of one another. It needs to be made clear how discrepancies between reviewers are dealt with.

The review of the criteria for inclusion and exclusion is primarily based on the title, abstract and subject headings in the databases, as well as on the keywords provided by the authors of a publication in the first step. In a second step the whole article / source will be read.

You can create tag words for the inclusion and exclusion in your literature management tool to keep an overview.

In addition to the common literature management tools, you can also use software tools that have been developed to support SLRs. The central library of the university in Zurich has published an overview and evaluation of different tools based on a survey among researchers. --> View SLR tools

The selection process needs to be made transparent. The PRISMA flow diagram supports the visualization of the number of included / excluded studies.

Forward and backward search

Should it become apparent that the number of sources found is relatively small, or if you wish to proceed with particular thoroughness, a forward-and-backward search based on the sources found is recommendable (Webster & Watson 2002, p. xvi). A backward search means going through the bibliographies of the sources found. A forward search, by contrast, identifies articles that have cited the relevant publications. The Web of Science and Scopus databases can be used to perform citation analyses.

6. Perform the review

As the next step, the remaining titles are analyzed as to their content by reading them several times in full. Information is extracted according to defined criteria and the quality of the publications is evaluated. If the data extraction is carried out by more than one person, a training ensures that there will be no differences between the reviewers.

Depending on the research questions there exist diffent methods for data abstraction (content analysis, concept matrix etc.). A so-called concept matrix can be used to structure the content of information (Webster & Watson 2002, p. xvii). The image to the right gives an example of a concept matrix according to Becker (2014).

Particularly in the field of economic sciences, the evaluation of a study’s quality cannot be performed according to a generally valid scheme, such as those existing in the field of medicine, for instance. Quality assessment therefore depends largely on the research questions.

Based on the findings of individual studies, a meta-level is then applied to try to understand what similarities and differences exist between the publications, what research gaps exist, etc. This may also result in the development of a theoretical model or reference framework.

Example concept matrix (Becker 2013) on the topic Business Process Management

| Article | Pattern | Configuration | Similarities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thom (2008) | x | ||

| Yang (2009) | x | x | |

| Rosa (2009) | x | x |

7. Synthesizing results

Once the review has been conducted, the results must be compiled and, on the basis of these, conclusions derived with regard to the research question (Fink 2014, p. 199ff.). This includes, for example, the following aspects:

- historical development of topics (histogram, time series: when, and how frequently, did publications on the research topic appear?);

- overview of journals, authors or specialist disciplines dealing with the topic;

- comparison of applied statistical methods;

- topics covered by research;

- identifying research gaps;

- developing a reference framework;

- developing constructs;

- performing a meta-analysis: comparison of the correlations of the results of different empirical studies (see for example Fink 2014, p. 203 on conducting meta-analyses)

Publications about the method

Bandara, W., Furtmueller, E., Miskon, S., Gorbacheva, E., & Beekhuyzen, J. (2015). Achieving Rigor in Literature Reviews: Insights from Qualitative Data Analysis and Tool-Support. Communications of the Association for Information Systems . 34(8), 154-204.

Booth, A., Papaioannou, D., and Sutton, A. (2012) Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. London: Sage.

Briner, R. B., & Denyer, D. (2012). Systematic Review and Evidence Synthesis as a Practice and Scholarship Tool. In Rousseau, D. M. (Hrsg.), The Oxford Handbook of Evidenence Based Management . (S. 112-129). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Durach, C. F., Wieland, A., & Machuca, Jose A. D. (2015). Antecedents and dimensions of supply chain robustness: a systematic literature review . International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistic Management , 46 (1/2), 118-137. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-05-2013-0133

Feak, C. B., & Swales, J. M. (2009). Telling a Research Story: Writing a Literature Review. English in Today's Research World 2. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. doi: 10.3998/mpub.309338

Fink, A. (2014). Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper (4. Aufl.). Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington DC: Sage Publication.

Fisch, C., & Block, J. (2018). Six tips for your (systematic) literature review in business and management research. Management Review Quarterly, 68, 103–106 (2018). doi.org/10.1007/s11301-018-0142-x

Guba, B. (2008). Systematische Literaturrecherche. Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift , 158 (1-2), S. 62-69. doi: doi.org/10.1007/s10354-007-0500-0 Hart, C. Doing a literature review: releasing the social science research imagination. London: Sage.

Jesson, J. K., Metheson, L. & Lacey, F. (2011). Doing your Literature Review - traditional and Systematic Techniques . Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington DC: Sage Publication.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71.

Petticrew, M. and Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide . Oxford:Blackwell. Ridley, D. (2012). The literature review: A step-by-step guide . 2nd edn. London: Sage.

Chang, W. and Taylor, S.A. (2016), The Effectiveness of Customer Participation in New Product Development: A Meta-Analysis, Journal of Marketing , American Marketing Association, Los Angeles, CA, Vol. 80 No. 1, pp. 47–64.

Tranfield, D., Denyer, D. & Smart, P. (2003). Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management , 14 (3), S. 207-222. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.00375

Webster, J., & Watson, R. T. (2002). Analyzing the Past to Prepare for the Future: Writing a Literature Review. Management Information Systems Quarterly , 26(2), xiii-xxiii. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4132319

Durach, C. F., Wieland, A. & Machuca, Jose. A. D. (2015). Antecedents and dimensions of supply chain robustness: a systematic literature review. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 45(1/2), 118 – 137.

What is particularly good about this example is that search terms were defined by a number of experts and the review was conducted by three researchers working independently of one another. Furthermore, the search terms used have been very well extracted and the procedure of the literature selection very well described.

On the downside, the restriction to English-language literature brings the language bias into play, even though the authors consider it to be insignificant for the subject area.

Bos-Nehles, A., Renkema, M. & Janssen, M. (2017). HRM and innovative work behaviour: a systematic literature review. Personnel Review, 46(7), pp. 1228-1253

- Only very specific keywords used

- No precise information on how the review process was carried out (who reviewed articles?)

- Only journals with impact factor (publication bias)

Jia, F., Orzes, G., Sartor, M. & Nassimbeni, G. (2017). Global sourcing strategy and structure: towards a conceptual framework. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 37(7), 840-864

- Research questions are explicitly presented

- Search string very detailed

- Exact description of the review process

- 2 persons conducted the review independently of each other

Franziska Klatt

+49 30 314-29778

Privacy notice: The TU Berlin offers a chat information service. If you enable it, your IP address and chat messages will be transmitted to external EU servers. more information

The chat is currently unavailable.

Please use our alternative contact options.

Advertisement

The ABC of systematic literature review: the basic methodological guidance for beginners

- Published: 23 October 2020

- Volume 55 , pages 1319–1346, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Hayrol Azril Mohamed Shaffril 1 ,

- Samsul Farid Samsuddin 2 &

- Asnarulkhadi Abu Samah 1 , 3

20k Accesses

154 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

There is a need for more methodological-based articles on systematic literature review (SLR) for non-health researchers to address issues related to the lack of methodological references in SLR and less suitability of existing methodological guidance. With that, this study presented a beginner's guide to basic methodological guides and key points to perform SLR, especially for those from non-health related background. For that, a total of 75 articles that passed the minimum quality were retrieved using systematic searching strategies. Seven main points of SLR were discussed, namely (1) the development and validation of the review protocol/publication standard/reporting standard/guidelines, (2) the formulation of research questions, (3) systematic searching strategies, (4) quality appraisal, (5) data extraction, (6) data synthesis, and (7) data demonstration.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Reading and interpreting reviews for health professionals: a practical review

Definition of a systematic review used in overviews of systematic reviews, meta-epidemiological studies and textbooks

What do meta-analysts need in primary studies guidelines and the semi checklist for facilitating cumulative knowledge, explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

Athukorala, K., Głowacka, D., Jacucci, G., Oulasvirta, A., Vreeken, J.: Is exploratory search different?: A comparison of information search behavior for exploratory and lookup tasks. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 67 (11), 2635–2651 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23617

Article Google Scholar

Barnett-Page, E., Thomas, J.: Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-9-59

Bates, J., Best, P., McQuilkin, J., Taylor, B.: Will web search engines replace bibliographic databases in the systematic identification of research? J. Acad. Librariansh. 43 (1), 8–17 (2017)

Google Scholar

Berrang-Ford, L., Pearce, T., Ford, J.D.: Systematic review approaches for climate change adaptation research. Reg. Environ. Change 15 (5), 755–769 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-014-0708-7

Braun, V., Clarke, V.: Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3 (2), 77–101 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Burgers, C., Brugman, B.C., Boeynaems, A.: Systematic literature reviews: four applications for interdisciplinary research. J. Pragmat. 145 , 102–109 (2019)

Brunton, G., Oliver, S., Oliver, K., Lorenc, T.: A Synthesis of Research Addressing Children’s, Young People’s and Parents’ Views of Walking and Cycling for Transport. EPPI-Centre, Social. Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London, London (2006)

Cañón, M., Buitrago-Gómez, Q.: The research question in clinical practice: a guideline for its formulation. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr. 47 (3), 193–200 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcp.2016.06.004

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination.: Systematic Reviews: CRD’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care. University of York, York (2006)

Charrois, T.L.: Systematic reviews: What do you get to know to get started? Can. J. Hosp. Pharm. 68 (2), 144–148 (2015)

Cooke, A., Smith, D., Booth, A.: Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 22 (10), 1435–1443 (2012)

Cooper, C., Booth, A., Campbell, J., Britten, N., Garside, R.: Defining the process to literature searching in systematic reviews: a literature review of guidance and supporting studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 18 , 85 (2018)

Creswell, J.: Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 3rd edn. Sage Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA (2013)

del Amo, I.F., Erkoyuncu, J.A., Roy, R., Palmarini, R., Onoufriou, D.: A systematic review of augmented reality content-related techniques for knowledge transfer in maintenance applications. Comput. Ind. 103 , 47–71 (2018)

Delaney, A., Tamás, P.A.: Searching for evidence or approval? A commentary on database search in systematic reviews and alternative information retrieval methodologies. Res. Synth. Method 9 (1), 124–131 (2018)

Dixon-Woods, M., Agarwal, S., Jones, D., Young, B., Sutton, A.: Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 10 (1), 45–53 (2005)

Doody, O., Bailey, M.E.: Setting a research question, aim and objective. Nurse Res. 23 (4), 19–23 (2016)

Durach, C.F., Kembro, J., Wieland, A.: A new paradigm for systematic literature reviews in supply chain management. J. Supply Chain Manag. 53 (4), 67–85 (2017)

Fagan, J.C.: An evidence-based review of academic web search engines, 2014–2016: implications for Librarians’ Practice and Research Agenda. Inf. Technol. Libr. 36 (2), 7–47 (2017)

Flemming, K., Booth, A., Garside, R., Tunc¸alp, O., Noyes J.: Qualitative evidence synthesis for complex interventions and guideline development: clarification of the purpose, designs and relevant methods. BMJ Global Health (2018)

Gomersall, J.S., Jadotte, Y.T., Xue, Y., Lockwood, S., Riddle, D., Preda, A.: Conducting systematic reviews of economic evaluations. Int. J. Evid.-Based Healthc. 13 (3), 170–178 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000063

Green, B.N., Johnson, C.D., Adams, A.: Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. J. Chiropr. Med. 5 (3), 101–117 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0899-3467(07)60142-6

Greyson, D., Rafferty, E., Slater, L., MacDonald, N., Bettinger, J.A., Dubé, È., MacDonald, S.E.: Systematic review searches must be systematic, comprehensive, and transparent: a critique of Perman et al. BMC Public Health 19 (1), 1–6 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6275-y

Gusenbauer, M.: Google Scholar to overshadow them all? Comparing the sizes of 12 academic search engines and bibliographic databases. Sciencetometrics 118 (1), 177–214 (2019)

Gusenbauer M, Haddaway NR (2020) Which academic search systems are suitable for systematic reviews or meta-analyses? Evaluating retrieval qualities of Google Scholar, PubMed, and 26 other resources. Res. Synth. Methods. 11(2):181–217. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1378

Haddaway, N.R., Collins, A.M., Coughlin, D., Kirk, S.: The role of google scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching. PLoS ONE 10 (9), e0138237 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138237

Haddaway, N.R., Macura, B., Whaley, P., Pulin, A.S.: ROSES Reporting standards for Systematic Evidence Syntheses: pro forma, flow-diagram and descriptive summary of the plan and conduct of environmental systematic reviews and systematic maps. Environ. Evid 7 , 7 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-018-0121-7

Halevi, G., Moed, H., Bar-Illan, J.: Suitability of Google Scholar as a source of scientific information and as a source of data for scientific evaluation. Revi Lit 11 (3), 823–834 (2017)

Hannes, K.: Critical appraisal of qualitative research. In: Noyes, J., Hannes, K., Harden, A., Harris, J., Lewin, S., Lockwood, C. (eds.) Supplementary Guidance for Inclusion of Qualitative Research in Cochrane Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Collaboration Qualitative Methods Group, London (2011)

Higgins, J.P.T., Altman, D.G., Gotzsche, P.C., Juni, P., Moher, D., Oxman, A.D., Savovic, J., Schulz, K.F., Weeks, L., Sterne, J.A.C.: The cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 343 (7829), 1–9 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928

Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A. (eds.): Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd edn. Wiley, Chichester (UK) (2019)

Hong, Q.N., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M-P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M-C., Vedel, I.: Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018. Registration of Copyright (#1148552), Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada (2018)

Housyar, M., Sotudeh, H.: A reflection on the applicability of Google Scholar as a tool for comprehensive retrieval in bibliometric research and systematic reviews. Int. J. Inf. Sci. Manag. 16 (2), 1–17 (2018)

Hopia, H., Latvala, E., Liimatainen, L.: Reviewing the methodology of an integrative review. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 30 (4), 662–669 (2016)

Johnson, B.T., Hennessy, E.A.: Systematic reviews and meta-analyses in the health sciences: best practice methods for research syntheses. Soc. Sci. Med. 233 , 237–251 (2019)

Kastner, M., Straus, S., Goldsmith, C.H.: Estimating the horizon of articles to decide when to stop searching in systematic reviews: an example using a systematic review of RCTs evaluating osteoporosis clinical decision support tools. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. Arch. 2007 , 389–393 (2007)

Kitchenham, B.A., Charters, S.M.: Guidelines for performing systematic literature reviews in software engineering. EBSE Technical Report (2007)

Kraus, S., Breier, M., Dasí-Rodríguez, S.: The art of crafting a systematic literature review in entrepreneurship research. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 16 (3), 1023–1042 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-020-00635-4

Kushwah, S., Dhir, A., Sagar, M., Gupta, B.: Determinants of organic food consumption. A systematic literature review on motives and barriers. Appetite 143 , 104402 (2019)

Levy, Y., Ellis, T.J.: A systems approach to conduct an effective literature review in supports of information system research. Inf. Sci. J. 9 , 181–212 (2006)