- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in A - General Economics and Teaching

- Browse content in A1 - General Economics

- A13 - Relation of Economics to Social Values

- Browse content in B - History of Economic Thought, Methodology, and Heterodox Approaches

- Browse content in B4 - Economic Methodology

- B41 - Economic Methodology

- Browse content in B5 - Current Heterodox Approaches

- B52 - Institutional; Evolutionary

- B54 - Feminist Economics

- Browse content in C - Mathematical and Quantitative Methods

- Browse content in C0 - General

- C01 - Econometrics

- Browse content in C1 - Econometric and Statistical Methods and Methodology: General

- C11 - Bayesian Analysis: General

- C12 - Hypothesis Testing: General

- C13 - Estimation: General

- C14 - Semiparametric and Nonparametric Methods: General

- C15 - Statistical Simulation Methods: General

- Browse content in C2 - Single Equation Models; Single Variables

- C21 - Cross-Sectional Models; Spatial Models; Treatment Effect Models; Quantile Regressions

- C22 - Time-Series Models; Dynamic Quantile Regressions; Dynamic Treatment Effect Models; Diffusion Processes

- C23 - Panel Data Models; Spatio-temporal Models

- C24 - Truncated and Censored Models; Switching Regression Models; Threshold Regression Models

- C25 - Discrete Regression and Qualitative Choice Models; Discrete Regressors; Proportions; Probabilities

- C26 - Instrumental Variables (IV) Estimation

- Browse content in C3 - Multiple or Simultaneous Equation Models; Multiple Variables

- C31 - Cross-Sectional Models; Spatial Models; Treatment Effect Models; Quantile Regressions; Social Interaction Models

- C32 - Time-Series Models; Dynamic Quantile Regressions; Dynamic Treatment Effect Models; Diffusion Processes; State Space Models

- C33 - Panel Data Models; Spatio-temporal Models

- C34 - Truncated and Censored Models; Switching Regression Models

- C35 - Discrete Regression and Qualitative Choice Models; Discrete Regressors; Proportions

- C36 - Instrumental Variables (IV) Estimation

- Browse content in C4 - Econometric and Statistical Methods: Special Topics

- C41 - Duration Analysis; Optimal Timing Strategies

- C43 - Index Numbers and Aggregation

- Browse content in C5 - Econometric Modeling

- C53 - Forecasting and Prediction Methods; Simulation Methods

- Browse content in C6 - Mathematical Methods; Programming Models; Mathematical and Simulation Modeling

- C60 - General

- C68 - Computable General Equilibrium Models

- Browse content in C8 - Data Collection and Data Estimation Methodology; Computer Programs

- C80 - General

- C81 - Methodology for Collecting, Estimating, and Organizing Microeconomic Data; Data Access

- C82 - Methodology for Collecting, Estimating, and Organizing Macroeconomic Data; Data Access

- C83 - Survey Methods; Sampling Methods

- Browse content in C9 - Design of Experiments

- C90 - General

- C91 - Laboratory, Individual Behavior

- C92 - Laboratory, Group Behavior

- C93 - Field Experiments

- Browse content in D - Microeconomics

- Browse content in D0 - General

- D01 - Microeconomic Behavior: Underlying Principles

- D02 - Institutions: Design, Formation, Operations, and Impact

- D03 - Behavioral Microeconomics: Underlying Principles

- D04 - Microeconomic Policy: Formulation; Implementation, and Evaluation

- Browse content in D1 - Household Behavior and Family Economics

- D10 - General

- D11 - Consumer Economics: Theory

- D12 - Consumer Economics: Empirical Analysis

- D13 - Household Production and Intrahousehold Allocation

- D14 - Household Saving; Personal Finance

- Browse content in D2 - Production and Organizations

- D22 - Firm Behavior: Empirical Analysis

- D23 - Organizational Behavior; Transaction Costs; Property Rights

- D24 - Production; Cost; Capital; Capital, Total Factor, and Multifactor Productivity; Capacity

- D25 - Intertemporal Firm Choice: Investment, Capacity, and Financing

- Browse content in D3 - Distribution

- D31 - Personal Income, Wealth, and Their Distributions

- D33 - Factor Income Distribution

- D4 - Market Structure, Pricing, and Design

- Browse content in D5 - General Equilibrium and Disequilibrium

- D58 - Computable and Other Applied General Equilibrium Models

- Browse content in D6 - Welfare Economics

- D60 - General

- D63 - Equity, Justice, Inequality, and Other Normative Criteria and Measurement

- D64 - Altruism; Philanthropy

- Browse content in D7 - Analysis of Collective Decision-Making

- D71 - Social Choice; Clubs; Committees; Associations

- D72 - Political Processes: Rent-seeking, Lobbying, Elections, Legislatures, and Voting Behavior

- D73 - Bureaucracy; Administrative Processes in Public Organizations; Corruption

- D74 - Conflict; Conflict Resolution; Alliances; Revolutions

- D78 - Positive Analysis of Policy Formulation and Implementation

- Browse content in D8 - Information, Knowledge, and Uncertainty

- D81 - Criteria for Decision-Making under Risk and Uncertainty

- D82 - Asymmetric and Private Information; Mechanism Design

- D83 - Search; Learning; Information and Knowledge; Communication; Belief; Unawareness

- D84 - Expectations; Speculations

- Browse content in D9 - Micro-Based Behavioral Economics

- D91 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making

- Browse content in E - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Browse content in E0 - General

- E01 - Measurement and Data on National Income and Product Accounts and Wealth; Environmental Accounts

- Browse content in E2 - Consumption, Saving, Production, Investment, Labor Markets, and Informal Economy

- E20 - General

- E21 - Consumption; Saving; Wealth

- E22 - Investment; Capital; Intangible Capital; Capacity

- E27 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E3 - Prices, Business Fluctuations, and Cycles

- E31 - Price Level; Inflation; Deflation

- E32 - Business Fluctuations; Cycles

- E39 - Other

- Browse content in E4 - Money and Interest Rates

- E41 - Demand for Money

- E42 - Monetary Systems; Standards; Regimes; Government and the Monetary System; Payment Systems

- E44 - Financial Markets and the Macroeconomy

- E47 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E5 - Monetary Policy, Central Banking, and the Supply of Money and Credit

- E50 - General

- E52 - Monetary Policy

- E58 - Central Banks and Their Policies

- Browse content in E6 - Macroeconomic Policy, Macroeconomic Aspects of Public Finance, and General Outlook

- E60 - General

- E61 - Policy Objectives; Policy Designs and Consistency; Policy Coordination

- E62 - Fiscal Policy

- E63 - Comparative or Joint Analysis of Fiscal and Monetary Policy; Stabilization; Treasury Policy

- Browse content in F - International Economics

- Browse content in F0 - General

- F01 - Global Outlook

- Browse content in F1 - Trade

- F10 - General

- F12 - Models of Trade with Imperfect Competition and Scale Economies; Fragmentation

- F13 - Trade Policy; International Trade Organizations

- F14 - Empirical Studies of Trade

- F15 - Economic Integration

- F16 - Trade and Labor Market Interactions

- F17 - Trade Forecasting and Simulation

- F18 - Trade and Environment

- Browse content in F2 - International Factor Movements and International Business

- F20 - General

- F21 - International Investment; Long-Term Capital Movements

- F22 - International Migration

- F23 - Multinational Firms; International Business

- F24 - Remittances

- Browse content in F3 - International Finance

- F31 - Foreign Exchange

- F32 - Current Account Adjustment; Short-Term Capital Movements

- F33 - International Monetary Arrangements and Institutions

- F34 - International Lending and Debt Problems

- F35 - Foreign Aid

- F36 - Financial Aspects of Economic Integration

- F37 - International Finance Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in F4 - Macroeconomic Aspects of International Trade and Finance

- F41 - Open Economy Macroeconomics

- F42 - International Policy Coordination and Transmission

- F43 - Economic Growth of Open Economies

- Browse content in F5 - International Relations, National Security, and International Political Economy

- F53 - International Agreements and Observance; International Organizations

- F54 - Colonialism; Imperialism; Postcolonialism

- F55 - International Institutional Arrangements

- F59 - Other

- Browse content in F6 - Economic Impacts of Globalization

- F60 - General

- Browse content in G - Financial Economics

- Browse content in G0 - General

- G01 - Financial Crises

- Browse content in G1 - General Financial Markets

- G11 - Portfolio Choice; Investment Decisions

- G14 - Information and Market Efficiency; Event Studies; Insider Trading

- G17 - Financial Forecasting and Simulation

- Browse content in G2 - Financial Institutions and Services

- G20 - General

- G21 - Banks; Depository Institutions; Micro Finance Institutions; Mortgages

- G22 - Insurance; Insurance Companies; Actuarial Studies

- G23 - Non-bank Financial Institutions; Financial Instruments; Institutional Investors

- G24 - Investment Banking; Venture Capital; Brokerage; Ratings and Ratings Agencies

- G28 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G3 - Corporate Finance and Governance

- G31 - Capital Budgeting; Fixed Investment and Inventory Studies; Capacity

- Browse content in H - Public Economics

- Browse content in H1 - Structure and Scope of Government

- H11 - Structure, Scope, and Performance of Government

- H12 - Crisis Management

- Browse content in H2 - Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H20 - General

- H21 - Efficiency; Optimal Taxation

- H22 - Incidence

- H24 - Personal Income and Other Nonbusiness Taxes and Subsidies; includes inheritance and gift taxes

- H26 - Tax Evasion and Avoidance

- Browse content in H3 - Fiscal Policies and Behavior of Economic Agents

- H30 - General

- H31 - Household

- Browse content in H4 - Publicly Provided Goods

- H40 - General

- H41 - Public Goods

- H42 - Publicly Provided Private Goods

- H43 - Project Evaluation; Social Discount Rate

- Browse content in H5 - National Government Expenditures and Related Policies

- H50 - General

- H51 - Government Expenditures and Health

- H52 - Government Expenditures and Education

- H54 - Infrastructures; Other Public Investment and Capital Stock

- H56 - National Security and War

- Browse content in H6 - National Budget, Deficit, and Debt

- H60 - General

- H61 - Budget; Budget Systems

- H62 - Deficit; Surplus

- H63 - Debt; Debt Management; Sovereign Debt

- Browse content in H7 - State and Local Government; Intergovernmental Relations

- H70 - General

- H71 - State and Local Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H77 - Intergovernmental Relations; Federalism; Secession

- Browse content in I - Health, Education, and Welfare

- Browse content in I1 - Health

- I10 - General

- I11 - Analysis of Health Care Markets

- I12 - Health Behavior

- I13 - Health Insurance, Public and Private

- I14 - Health and Inequality

- I15 - Health and Economic Development

- I18 - Government Policy; Regulation; Public Health

- I19 - Other

- Browse content in I2 - Education and Research Institutions

- I20 - General

- I21 - Analysis of Education

- I22 - Educational Finance; Financial Aid

- I23 - Higher Education; Research Institutions

- I25 - Education and Economic Development

- I26 - Returns to Education

- I28 - Government Policy

- Browse content in I3 - Welfare, Well-Being, and Poverty

- I30 - General

- I31 - General Welfare

- I32 - Measurement and Analysis of Poverty

- I38 - Government Policy; Provision and Effects of Welfare Programs

- Browse content in J - Labor and Demographic Economics

- Browse content in J0 - General

- J01 - Labor Economics: General

- Browse content in J1 - Demographic Economics

- J10 - General

- J11 - Demographic Trends, Macroeconomic Effects, and Forecasts

- J12 - Marriage; Marital Dissolution; Family Structure; Domestic Abuse

- J13 - Fertility; Family Planning; Child Care; Children; Youth

- J15 - Economics of Minorities, Races, Indigenous Peoples, and Immigrants; Non-labor Discrimination

- J16 - Economics of Gender; Non-labor Discrimination

- J17 - Value of Life; Forgone Income

- J18 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J2 - Demand and Supply of Labor

- J21 - Labor Force and Employment, Size, and Structure

- J22 - Time Allocation and Labor Supply

- J23 - Labor Demand

- J24 - Human Capital; Skills; Occupational Choice; Labor Productivity

- J26 - Retirement; Retirement Policies

- Browse content in J3 - Wages, Compensation, and Labor Costs

- J31 - Wage Level and Structure; Wage Differentials

- J38 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J4 - Particular Labor Markets

- J41 - Labor Contracts

- J42 - Monopsony; Segmented Labor Markets

- J43 - Agricultural Labor Markets

- J45 - Public Sector Labor Markets

- J46 - Informal Labor Markets

- Browse content in J5 - Labor-Management Relations, Trade Unions, and Collective Bargaining

- J51 - Trade Unions: Objectives, Structure, and Effects

- Browse content in J6 - Mobility, Unemployment, Vacancies, and Immigrant Workers

- J61 - Geographic Labor Mobility; Immigrant Workers

- J62 - Job, Occupational, and Intergenerational Mobility

- J64 - Unemployment: Models, Duration, Incidence, and Job Search

- J68 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J7 - Labor Discrimination

- J71 - Discrimination

- J78 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J8 - Labor Standards: National and International

- J82 - Labor Force Composition

- Browse content in K - Law and Economics

- Browse content in K4 - Legal Procedure, the Legal System, and Illegal Behavior

- K42 - Illegal Behavior and the Enforcement of Law

- K49 - Other

- Browse content in L - Industrial Organization

- Browse content in L1 - Market Structure, Firm Strategy, and Market Performance

- L10 - General

- L11 - Production, Pricing, and Market Structure; Size Distribution of Firms

- L13 - Oligopoly and Other Imperfect Markets

- L14 - Transactional Relationships; Contracts and Reputation; Networks

- Browse content in L2 - Firm Objectives, Organization, and Behavior

- L21 - Business Objectives of the Firm

- L22 - Firm Organization and Market Structure

- L23 - Organization of Production

- L26 - Entrepreneurship

- Browse content in L3 - Nonprofit Organizations and Public Enterprise

- L31 - Nonprofit Institutions; NGOs; Social Entrepreneurship

- L33 - Comparison of Public and Private Enterprises and Nonprofit Institutions; Privatization; Contracting Out

- Browse content in L6 - Industry Studies: Manufacturing

- L60 - General

- L67 - Other Consumer Nondurables: Clothing, Textiles, Shoes, and Leather Goods; Household Goods; Sports Equipment

- Browse content in L7 - Industry Studies: Primary Products and Construction

- L72 - Mining, Extraction, and Refining: Other Nonrenewable Resources

- Browse content in L8 - Industry Studies: Services

- L83 - Sports; Gambling; Recreation; Tourism

- Browse content in M - Business Administration and Business Economics; Marketing; Accounting; Personnel Economics

- Browse content in M5 - Personnel Economics

- M50 - General

- Browse content in N - Economic History

- N0 - General

- Browse content in N1 - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics; Industrial Structure; Growth; Fluctuations

- N10 - General, International, or Comparative

- N15 - Asia including Middle East

- N17 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in N2 - Financial Markets and Institutions

- N27 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in N3 - Labor and Consumers, Demography, Education, Health, Welfare, Income, Wealth, Religion, and Philanthropy

- N30 - General, International, or Comparative

- N37 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in N4 - Government, War, Law, International Relations, and Regulation

- N47 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in N5 - Agriculture, Natural Resources, Environment, and Extractive Industries

- N57 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in N6 - Manufacturing and Construction

- N67 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in N7 - Transport, Trade, Energy, Technology, and Other Services

- N77 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in O - Economic Development, Innovation, Technological Change, and Growth

- Browse content in O1 - Economic Development

- O10 - General

- O11 - Macroeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O12 - Microeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O13 - Agriculture; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Other Primary Products

- O14 - Industrialization; Manufacturing and Service Industries; Choice of Technology

- O15 - Human Resources; Human Development; Income Distribution; Migration

- O16 - Financial Markets; Saving and Capital Investment; Corporate Finance and Governance

- O17 - Formal and Informal Sectors; Shadow Economy; Institutional Arrangements

- O18 - Urban, Rural, Regional, and Transportation Analysis; Housing; Infrastructure

- O19 - International Linkages to Development; Role of International Organizations

- Browse content in O2 - Development Planning and Policy

- O20 - General

- O21 - Planning Models; Planning Policy

- O22 - Project Analysis

- O23 - Fiscal and Monetary Policy in Development

- O24 - Trade Policy; Factor Movement Policy; Foreign Exchange Policy

- O25 - Industrial Policy

- O29 - Other

- Browse content in O3 - Innovation; Research and Development; Technological Change; Intellectual Property Rights

- O31 - Innovation and Invention: Processes and Incentives

- O38 - Government Policy

- Browse content in O4 - Economic Growth and Aggregate Productivity

- O40 - General

- O41 - One, Two, and Multisector Growth Models

- O43 - Institutions and Growth

- O47 - Empirical Studies of Economic Growth; Aggregate Productivity; Cross-Country Output Convergence

- O49 - Other

- Browse content in O5 - Economywide Country Studies

- O50 - General

- O53 - Asia including Middle East

- O55 - Africa

- O56 - Oceania

- O57 - Comparative Studies of Countries

- Browse content in P - Economic Systems

- Browse content in P1 - Capitalist Systems

- P11 - Planning, Coordination, and Reform

- P16 - Political Economy

- P2 - Socialist Systems and Transitional Economies

- Browse content in P4 - Other Economic Systems

- P47 - Performance and Prospects

- P48 - Political Economy; Legal Institutions; Property Rights; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Regional Studies

- Browse content in Q - Agricultural and Natural Resource Economics; Environmental and Ecological Economics

- Browse content in Q0 - General

- Q00 - General

- Q01 - Sustainable Development

- Q02 - Commodity Markets

- Browse content in Q1 - Agriculture

- Q10 - General

- Q11 - Aggregate Supply and Demand Analysis; Prices

- Q12 - Micro Analysis of Farm Firms, Farm Households, and Farm Input Markets

- Q13 - Agricultural Markets and Marketing; Cooperatives; Agribusiness

- Q14 - Agricultural Finance

- Q15 - Land Ownership and Tenure; Land Reform; Land Use; Irrigation; Agriculture and Environment

- Q16 - R&D; Agricultural Technology; Biofuels; Agricultural Extension Services

- Q17 - Agriculture in International Trade

- Q18 - Agricultural Policy; Food Policy

- Q19 - Other

- Browse content in Q2 - Renewable Resources and Conservation

- Q22 - Fishery; Aquaculture

- Q23 - Forestry

- Q25 - Water

- Browse content in Q3 - Nonrenewable Resources and Conservation

- Q32 - Exhaustible Resources and Economic Development

- Q33 - Resource Booms

- Q34 - Natural Resources and Domestic and International Conflicts

- Q38 - Government Policy

- Browse content in Q4 - Energy

- Q40 - General

- Q42 - Alternative Energy Sources

- Q48 - Government Policy

- Browse content in Q5 - Environmental Economics

- Q50 - General

- Q54 - Climate; Natural Disasters; Global Warming

- Q55 - Technological Innovation

- Q56 - Environment and Development; Environment and Trade; Sustainability; Environmental Accounts and Accounting; Environmental Equity; Population Growth

- Browse content in R - Urban, Rural, Regional, Real Estate, and Transportation Economics

- Browse content in R1 - General Regional Economics

- R11 - Regional Economic Activity: Growth, Development, Environmental Issues, and Changes

- R12 - Size and Spatial Distributions of Regional Economic Activity

- R13 - General Equilibrium and Welfare Economic Analysis of Regional Economies

- Browse content in R2 - Household Analysis

- R20 - General

- R23 - Regional Migration; Regional Labor Markets; Population; Neighborhood Characteristics

- R28 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R3 - Real Estate Markets, Spatial Production Analysis, and Firm Location

- R32 - Other Spatial Production and Pricing Analysis

- Browse content in R4 - Transportation Economics

- R41 - Transportation: Demand, Supply, and Congestion; Travel Time; Safety and Accidents; Transportation Noise

- Browse content in R5 - Regional Government Analysis

- R53 - Public Facility Location Analysis; Public Investment and Capital Stock

- R58 - Regional Development Planning and Policy

- Browse content in Z - Other Special Topics

- Browse content in Z1 - Cultural Economics; Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology

- Z12 - Religion

- Z13 - Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology; Social and Economic Stratification

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish

- About Journal of African Economies

- About the Centre for the Study of African Economies

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1. introduction, 2. a brief review of the current state of education in africa, 3. what do earlier syntheses say about education in africa, 6. discussion.

- < Previous

Education in Africa: What Are We Learning?

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

David K Evans, Amina Mendez Acosta, Education in Africa: What Are We Learning?, Journal of African Economies , Volume 30, Issue 1, January 2021, Pages 13–54, https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/ejaa009

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Countries across Africa continue to face major challenges in education. In this review, we examine 145 recent empirical studies (from 2014 onward) on how to increase access to and improve the quality of education across the continent, specifically examining how these studies update previous research findings. We find that 64% of the studies evaluate government-implemented programs, 36% include detailed cost analysis and 35% evaluate multiple treatment arms. We identify several areas where new studies provide rigorous evidence on topics that do not figure prominently in earlier evidence syntheses. New evidence shows promising impacts of structured pedagogy interventions (which typically provide a variety of inputs, such as lesson plans and training for teachers together with new materials for students) and of mother tongue instruction interventions, as well as from a range of teacher programs, including both remunerative (pay-for-performance of various designs) and non-remunerative (coaching and certain types of training) programs. School feeding delivers gains in both access and learning. New studies also show long-term positive impacts of eliminating school fees for primary school and positive impacts of eliminating fees in secondary school. Education technology interventions have decidedly mixed impacts, as do school grant programs and programs providing individual learning inputs (e.g., uniforms or textbooks).

Education has expanded dramatically in Sub-Saharan Africa over the past half century. From 1970 to 2010, the percentage of children across the region who complete primary school rose by almost 50% (from 46% of children to 68%). The proportion of children completing lower secondary school nearly doubled (from 22% to 40%). 1 Despite these massive gains, nearly one in three children still does not complete primary school. Efforts to measure the quality of that schooling have revealed high numbers of students who have limited literacy or numeracy skills even after several years of school ( Bold et al. , 2017 ; Adeniran et al. , 2020 ). The international community has characterised this situation as a ‘learning crisis’ ( World Bank, 2018a ). The past two decades have seen a large rise in evidence on how to most effectively expand access and increase learning, 2 but actual changes in access and learning in that period have not shown dramatic improvements. 3

In this paper, we synthesise recent research on how to expand access to education and improve the quality of learning in Africa. 4 Our analysis reveals two trends. First, we observe growing sophistication in evaluating education programs in Africa. An increasing number of studies not only examine whether a given intervention is effective but also test multiple permutations. For example, Mbiti et al. (2019b) test two alternative teacher incentive programs and Duflo et al. (2020) report on four alternative programs to target instruction to students’ learning levels. Evaluations are also testing alternative combinations of interventions, such as teacher incentives, school grants or the combination of the two in Tanzania ( Mbiti et al. , 2019a ). Other studies compare alternative programs to achieve a common goal, as in education subsidies versus the government HIV curriculum to reduce sexually transmitted infections in Duflo et al. (2015b ). Testing multiple treatments is certainly not unprecedented in African countries, but it is growing more common. 5 Second, we observe growth in evidence that previously was largely confined to other regions of the world, including early child development, mother tongue instruction and public–private partnerships.

In terms of substantive findings, we identify that certain multi-faceted programs deliver large gains in education quality: a program that includes teacher training, teacher coaching, semi-scripted lessons, learning materials and mother tongue instruction delivered sizeable gains in literacy both as a pilot and at-scale ( Piper et al. , 2018a , 2018b ); the average impacts for second-grade students in Kiswahili and English are both above the 99th percentile of education interventions ( Evans and Yuan, 2020 ; Kraft, 2020 ). A literacy program providing a similar array of supports delivered literacy gains in Uganda ( Brunette et al. , 2019 ). The combination of teacher incentives and school grants delivered higher learning gains than either on its own in Tanzania ( Mbiti et al. , 2019a ).

We also observe consistent gains across various other types of programs: mother tongue instruction seems to provide consistent learning gains across programs, eliminating school fees offers consistent gains in access, and school feeding offers consistent gains in access and learning. There are relatively few school construction studies, but they also tend to yield gains in both access and learning. Other inputs are inconsistent: cash transfers are reasonably consistent in increasing access to school but not at improving learning, which may be unsurprising given that the programs may relax an economic constraint to access for the children but do not directly affect the learning process beyond that. Similarly, eliminating school fees has inconsistent impacts on the quality of education.

Our collection of evidence does not offer a single solution that will apply in every school system. Programs adapted to new contexts will often yield distinct impacts. In our discussion section, we elaborate on factors to consider when translating a program from one setting to another. Still, this accumulation of recent evidence offers promising areas for investment and wide avenues for further study.

This review updates findings from earlier reviews with results from new research. Evans and Popova (2016b) synthesise evidence from six reviews on how to improve learning outcomes from low- and middle-income countries, only one of which— Conn (2017) —focuses exclusively on evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa, while others include significant research from the region. 6 This review focuses on how research in Africa from the past 5 years updates our ideas on making education effective and accessible.

In Section 2 , we briefly review the current state of education in Africa. In Section 3 , we summarise earlier evidence on how to expand access to and improve the quality of education on the continent. In Section 4 , we discuss our strategy for collecting and analysing new research. In Section 5 , we synthesise the findings. In Section 6 , we draw conclusions from our findings, highlight areas for needed future research and discuss implications for policy.

Primary Completion Rates in Sub-Saharan Africa, 1971–2015 Source: Author tabulations using data from World Development Indicators (2020) .

Lower Secondary Completion Rates in Sub-Saharan Africa, 1971–2015 Source: Author tabulations using data from World Development Indicators (2020) .

Education in Africa has expanded dramatically in recent years ( Figures 1 and 2 ). The median proportion of children completing primary school across countries has risen from 27% to 67% between 1971 and 2015 ( World Bank, 2020 ). The median proportion of children completing lower secondary school across countries has also risen dramatically, from a mere 5% in 1971 to 40% in 2015. 7 These are enormous increases; they also demonstrate just how far there is to go. Nearly one in three children in the median country does not complete primary school, and three in five fail to complete lower secondary. Africa is the lowest performing region in the world in terms of school access by a significant margin ( Figure 3 ): for primary completion, all other countries achieve higher than 90%. For lower secondary, the next lowest performing region has a completion rate of 75%, more than 70% higher than Africa’s numbers. Median completion rates at both levels of education have been increasing at a roughly consistent rate between 2000 and 2015, between 1.2 (primary) and 1.1 (lower secondary) percentage points a year. With linear improvements at that same rate, Africa would achieve universal primary education in 28 years and universal lower secondary education in 56 years. Yet, access will likely not increase at a linear rate, given the increasing marginal cost of enroling the most difficult-to-reach children (the ‘last mile’ challenge), leading these to be underestimates.

Primary and Lower Secondary Completion Rates across Regions in 2015 Source: Author tabulations using data from World Development Indicators (2020) .

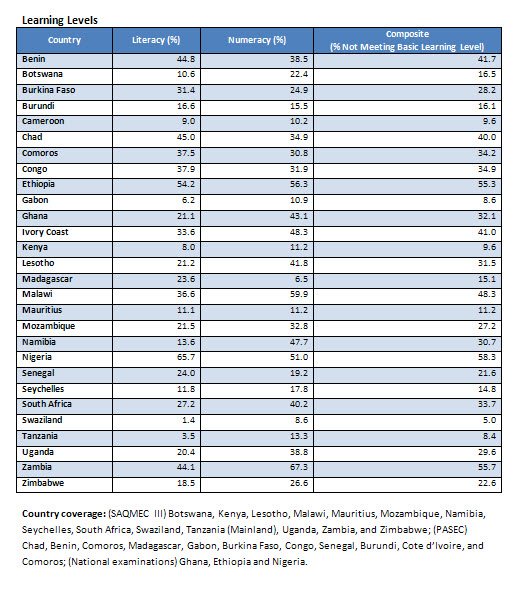

At the same time, the education quality in Africa also suffers. Recent evidence across seven countries in Sub-Saharan Africa found that in third grade, less than two in three children could read a letter and only about half of the children could read a word or put numbers in order ( Bold et al. , 2017 ; Table 1 ). 8 The harmonised learning outcomes, an effort by Patrinos and Angrist (2018) to combine data from different tests across regions, finds that learning outcomes for countries in Sub-Saharan Africa concentrated in the bottom half of the learning spectrum; although they are not substantively lower than what would be expected for Africa’s income levels ( Figure 4 ). A combined measure of schooling quantity and quality—the learning-adjusted years of schooling ( Filmer et al. , 2020 )—shows more African countries performing below what their income level would predict ( Figure 5 ). Further, the quality of learning outcomes does not appear to be rising in recent years. Le Nestour et al. (2020 ) document steady increases in adult literacy rates between 1940 and 2000, mostly linked to increases in enrollment. However, the test score data from the World Bank’s Human Capital Project show that for 35 African countries with two data points between 2000 and 2017, scores fell for 18 countries and rose for 17 countries ( Table 1 ; Angrist et al. , 2019 ). Some of the inconsistent gains in learning may result from expanding access: as children with less preparation gain access to school and participate in tests, average scores could fall even while learning is rising. Despite weaknesses in education quality, recent studies demonstrate significant returns to education in Africa ( Appendix Section 1, Supplementary Material ).

Change in Learning Outcomes in African Countries for Two Time Periods between 2000 and 2017

| Country . | Year of first data . | Year of last data . | Number of years between first and last data . | Harmonised learning outcomes, earliest year . | Harmonised learning outcomes, latest year . | Difference . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | 2004 | 2014 | 10 | 385 | 376 | −9 |

| Burundi | 2006 | 2014 | 8 | 425 | 423 | −2 |

| Benin | 2006 | 2014 | 8 | 377 | 384 | 7 |

| Burkina Faso | 2006 | 2014 | 8 | 402 | 404 | 2 |

| Botswana | 2000 | 2015 | 15 | 397 | 391 | −5 |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 2006 | 2014 | 8 | 377 | 373 | −3 |

| Cameroon | 2006 | 2014 | 8 | 451 | 379 | −72 |

| Congo, Dem. Rep. | 2006 | 2012 | 6 | 429 | 318 | −112 |

| Congo, Rep. | 2006 | 2014 | 8 | 398 | 371 | −28 |

| Egypt, Arab Rep. | 2003 | 2015 | 12 | 414 | 356 | −58 |

| Ghana | 2003 | 2013 | 10 | 266 | 307 | 42 |

| Gambia, The | 2007 | 2011 | 4 | 356 | 338 | −18 |

| Kenya | 2000 | 2013 | 13 | 426 | 455 | 29 |

| Liberia | 2011 | 2013 | 2 | 343 | 332 | −12 |

| Lesotho | 2000 | 2013 | 13 | 345 | 393 | 48 |

| Morocco | 2003 | 2015 | 12 | 354 | 367 | 13 |

| Madagascar | 2006 | 2015 | 9 | 434 | 351 | −83 |

| Mali | 2002 | 2015 | 13 | 387 | 307 | −79 |

| Mozambique | 2000 | 2007 | 7 | 402 | 368 | −33 |

| Mauritius | 2000 | 2013 | 13 | 430 | 473 | 43 |

| Malawi | 2000 | 2013 | 13 | 331 | 359 | 29 |

| Namibia | 2000 | 2013 | 13 | 337 | 407 | 69 |

| Niger | 2002 | 2014 | 12 | 370 | 305 | −65 |

| Rwanda | 2015 | 2016 | 1 | 343 | 358 | 15 |

| Senegal | 2006 | 2014 | 8 | 415 | 412 | −2 |

| South Sudan | 2016 | 2017 | 1 | 334 | 336 | 2 |

| Eswatini | 2000 | 2013 | 13 | 401 | 440 | 39 |

| Seychelles | 2000 | 2013 | 13 | 436 | 463 | 27 |

| Chad | 2006 | 2014 | 8 | 403 | 333 | −70 |

| Togo | 2001 | 2014 | 13 | 423 | 384 | −40 |

| Tunisia | 2003 | 2015 | 12 | 376 | 384 | 8 |

| Tanzania | 2000 | 2013 | 13 | 410 | 388 | −21 |

| Uganda | 2000 | 2013 | 13 | 379 | 397 | 18 |

| South Africa | 2000 | 2015 | 15 | 375 | 343 | −33 |

| Zambia | 2000 | 2013 | 13 | 336 | 358 | 22 |

| Zimbabwe | 2007 | 2013 | 6 | 394 | 396 | 2 |

| Country . | Year of first data . | Year of last data . | Number of years between first and last data . | Harmonised learning outcomes, earliest year . | Harmonised learning outcomes, latest year . | Difference . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | 2004 | 2014 | 10 | 385 | 376 | −9 |

| Burundi | 2006 | 2014 | 8 | 425 | 423 | −2 |

| Benin | 2006 | 2014 | 8 | 377 | 384 | 7 |

| Burkina Faso | 2006 | 2014 | 8 | 402 | 404 | 2 |

| Botswana | 2000 | 2015 | 15 | 397 | 391 | −5 |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 2006 | 2014 | 8 | 377 | 373 | −3 |

| Cameroon | 2006 | 2014 | 8 | 451 | 379 | −72 |

| Congo, Dem. Rep. | 2006 | 2012 | 6 | 429 | 318 | −112 |

| Congo, Rep. | 2006 | 2014 | 8 | 398 | 371 | −28 |

| Egypt, Arab Rep. | 2003 | 2015 | 12 | 414 | 356 | −58 |

| Ghana | 2003 | 2013 | 10 | 266 | 307 | 42 |

| Gambia, The | 2007 | 2011 | 4 | 356 | 338 | −18 |

| Kenya | 2000 | 2013 | 13 | 426 | 455 | 29 |

| Liberia | 2011 | 2013 | 2 | 343 | 332 | −12 |

| Lesotho | 2000 | 2013 | 13 | 345 | 393 | 48 |

| Morocco | 2003 | 2015 | 12 | 354 | 367 | 13 |

| Madagascar | 2006 | 2015 | 9 | 434 | 351 | −83 |

| Mali | 2002 | 2015 | 13 | 387 | 307 | −79 |

| Mozambique | 2000 | 2007 | 7 | 402 | 368 | −33 |

| Mauritius | 2000 | 2013 | 13 | 430 | 473 | 43 |

| Malawi | 2000 | 2013 | 13 | 331 | 359 | 29 |

| Namibia | 2000 | 2013 | 13 | 337 | 407 | 69 |

| Niger | 2002 | 2014 | 12 | 370 | 305 | −65 |

| Rwanda | 2015 | 2016 | 1 | 343 | 358 | 15 |

| Senegal | 2006 | 2014 | 8 | 415 | 412 | −2 |

| South Sudan | 2016 | 2017 | 1 | 334 | 336 | 2 |

| Eswatini | 2000 | 2013 | 13 | 401 | 440 | 39 |

| Seychelles | 2000 | 2013 | 13 | 436 | 463 | 27 |

| Chad | 2006 | 2014 | 8 | 403 | 333 | −70 |

| Togo | 2001 | 2014 | 13 | 423 | 384 | −40 |

| Tunisia | 2003 | 2015 | 12 | 376 | 384 | 8 |

| Tanzania | 2000 | 2013 | 13 | 410 | 388 | −21 |

| Uganda | 2000 | 2013 | 13 | 379 | 397 | 18 |

| South Africa | 2000 | 2015 | 15 | 375 | 343 | −33 |

| Zambia | 2000 | 2013 | 13 | 336 | 358 | 22 |

| Zimbabwe | 2007 | 2013 | 6 | 394 | 396 | 2 |

Source: Authors’ construction, using all African countries with at least two data points. For countries with more than two data points, we used the first and last data point. Data provided by Angrist et al. (2019) .

Test Scores for Countries at All Income Levels around the World Relative to Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa Source: Authors’ construction using the harmonised test scores from the Human Capital Project ( World Bank, 2018b,c ).

Learning-adjusted Years of Schooling for 158 Countries around the World Relative to Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa Source: Authors’ construction using the data from the Human Capital Project ( World Bank, 2018b,c ).

This is not the first study to synthesise evidence on education, even in Africa. Bashir et al. (2018) provide a comprehensive descriptive analysis of the current state of education across the continent, highlighting that many children remain out of school, that learning levels are low for those in school and that ‘the problem of low learning emerges in the early grades’. In terms of priorities for improvement, Evans and Popova (2016b) review the following six syntheses of evidence on how to improve the quality of education in low- and middle-income countries: Conn (2017) , Glewwe et al. (2014) , Kremer et al. (2013) , Krishnaratne et al. (2013) , McEwan (2015) and Ganimian and Murnane (2016) . Another review focused on learning, released slightly later, was Masino and Niño-Zarazúa (2016) . Across the reviews that focused on boosting learning, the authors recommend many different interventions, but Evans and Popova (2016b) identify two classes of interventions that are recommended with some consistency: pedagogical interventions that help teachers to tailor instruction to student learning levels and individualised, repeated efforts to improve teacher’s ability and practice.

Of these reviews, only Conn (2017) focuses exclusively on Sub-Saharan Africa, although several others draw heavily on evidence from the region. Based on a meta-analysis of 56 studies available through 2013, Conn finds the largest learning impacts for programs that ‘alter teacher pedagogy or classroom instructional techniques’. Snilstveit et al. (2015) is the most comprehensive review, examining 238 studies focused on both access and learning across low- and middle-income countries (not exclusive to Sub-Saharan Africa). 9 They find the strongest, most consistent gains in access from cash transfer programs and the best gains to quality from ‘structured pedagogy’ programs; those that provide a variety of inputs to improve teaching, such as lesson plans and training for teachers together with new materials for students (similarly to Conn, 2017 ). They also find promising evidence that school feeding programs can increase both access and learning. Glewwe and Muralidharan (2016) also examine both access and learning, finding strong gains from improved pedagogy—especially for foundational literacy and numeracy skills, improved governance—including teacher accountability and cost reductions.

In this review, we complement this previous work with evidence published in 2014 or later, most of which came out later than the scope of the searches conducted by previous reviews.

4.1. Inclusion criteria

For this paper, we limited our focus to research studies that (i) were published in 2014 or later, either as a journal article, a conference paper or a working paper; (ii) were conducted in or used data from at least one African country; and (iii) report on outcomes from education-related interventions. We included interventions that may not focus exclusively on education outcomes but do report them, such as cash transfers and school feeding programs. We also limited our search to papers that include a quantitative analysis of results that seeks to establish a counterfactual including a variety of estimation designs such as randomised controlled trial, difference-in-differences, matching, regression discontinuity and instrumental variable analysis. As a result, studies that report purely descriptive data or carried out a case study were not included in our primary analysis. Some descriptive studies are used to provide context to our discussion of results.

4.2. Search strategy

We began by compiling a database of papers that complied with the above criteria from published systematic reviews such as Conn (2014) , Glewwe et al. (2014) , Snilsveit et al. (2015) , Evans and Popova (2016b) and Evans and Yuan (2019) . We also reviewed papers from the National Bureau of Economic Research working paper series, the World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series, the Centre for the Study of African Economies 2017–2020 conference papers and the North East Universities Development Consortium conference papers 2017–2019. We included papers identified in the African Education Research Database ( Education Sub Saharan Africa, 2020 ). Finally, we searched Google Scholar and journal databases using variations of the search terms ‘education’, ‘learning’ and ‘students’ and confirmed the location of the intervention or the source of the data used. The journal databases searched included the American Economic Review, the Quarterly Journal of Economics, the Journal of Political Economy, the Journal of African Economies, World Development, the Economics of Education Review, the Journal of Development Effectiveness, the International Journal of Educational Development and the International Journal of Educational Research. We included studies from other journals as turned up by our database searches. We also added studies known to the authors that are eligible but did not come up in the original search. We conducted the search between September 2019 and May 2020 and compiled a list of 195 papers eligible for review. See Appendix Table 2 for the breakdown of the papers by provenance. In this study, we review 145 of those papers on topics of current interest in education (excluding, for example, a study on the historical impact of Christian missions on education performance in later generations).

4.3. Analytical strategy

The purpose of this review is to understand the direction and scope of recent education research in Africa, including the choice of topics and interventions studied, the countries where these studies are being conducted and the key trends and messages in their findings.

In order to answer these questions, we reviewed the title, abstract and full text of the papers to extract and code the following data: country of intervention, year of publication, type of intervention (if there is one), type of intervention target (student, teacher, household, school or system), type of outcomes reported (learning, access or both), education level of intervention (pre-primary, primary, secondary, tertiary, vocational or adult learning), education level of outcomes reported, research method, scale (i.e., number of treatment arms and the size of the treatment sample) and key findings. We also encoded the choice of implementation partner (government agencies, non-government organisations, other partners or researchers only) and any cost-effectiveness data provided in the paper.

We grouped the studies according to common themes and interventions and present a narrative review of the findings. We avoid the other two main types of review (meta-analysis and vote counting) because of large variation in the design of interventions within categories: an average effect of a teacher training intervention—for example—is not informative when one is averaging across programs as varied as a one-time half-day lecture for teachers and a full-year program of classroom observations with feedback. 10 This narrative approach is more helpful for solving some problems and less helpful for solving others. Our approach is intended to help readers to update their prior beliefs within key classes of educational interventions that are commonly—and in many cases—increasingly used across the continent. It can guide the design of educational interventions within categories: for example, many countries have cash transfer programs or school feeding programs and this analysis can guide decisions about the optimal design of those programs. On the other hand, not providing meta-analytic results means that this review will not answer the question, should a given country implement a cash transfer program or a school feeding program (i.e., is the expected impact of one class of program greater than the other)? While there is certainly insight to be gleaned from that approach (and other reviews have used it, including McEwan, 2015 ; Snilstveit et al. , 2015 ; and Conn, 2017 ), the wide variety of designs and effect sizes within categories incline us—in this review—to focus on characterising the range of evidence within groups and encouraging researchers and policymakers to dig deeper into individual studies that may be most relevant to a context and class of program that they are considering.

4.4. The studies

The collection of studies reveals interesting findings on what is studied and where. We identify a high concentration of studies in Kenya (41) and Uganda (21) with fewer but still significant numbers of studies in Ethiopia (17), Ghana (15), Nigeria (13) and Tanzania (13) ( Figure 6 ). Most studies we identify focus on primary education (61%) and almost a quarter of studies examine secondary education (24%). Fewer studies examine pre-primary (8%), with just a handful examining tertiary, adult education or technical-vocational training (6% and under each) ( Figure 7 ).

Distribution of Identified Education Studies (2014–2020) across Countries in Africa. The countries with the most studies are Kenya (41), Uganda (21), Ethiopia (17), Ghana (15), Nigeria (13) and Tanzania (13). This figure includes the 195 studies that passed the eligibility criteria of our search. In the Results section, we restrict the sample to 145 studies on topics that are of current interest in education

Distribution of Identified Education Studies (2014–2020) across Levels of Education and Classes of Outcomes. Access includes all outcomes related to students staying in school such as rates of enrollment, attendance and drop-out. Sum of values may exceed 100% since interventions can be implemented in more than one phase of education. Other outcomes include labour market outcomes and other life outcomes. This figure includes the 195 studies that passed the eligibility criteria of our search. In the Results section, we restrict the sample to 145 studies on topics that are of current interest in education

The majority of the interventions (72%) evaluated by the studies are administered through the school system, including interventions targeting teachers, school management and students, while only about 38% of the studies are targeted at the household level ( Figure 8 ). School-system interventions usually aim to increase students’ enrollment and retention and improve the quality of the learning environment. These interventions are (i) teacher- and teaching-targeted programs such as pedagogy, mother tongue instruction, education technology, teacher incentives and trainings and hiring practices; (ii) student-level interventions including health and nutrition programs (e.g., school feeding), incentives for students and individual inputs such as uniforms, solar lamps or bicycles; and (iii) school-level interventions such as school construction, school grants, public–private partnerships and other non-government school provision and community-based monitoring. The household-level interventions usually aim to reduce the economic and social barriers that keep households from sending their children to school—providing cash transfers, low-cost early child development care centres and learning and attendance information to parents.

Distribution of the Studies by Targeting the Level and Class of Intervention. Our sample includes household-targeted interventions (75 studies, 38%), teacher-targeted (81 studies, 42%), student-targeted (38 studies, 19%) and school-targeted (22 studies, 11%). The sum of the percentages is more than 100 since each intervention may target more than one group. This figure includes the 195 studies that passed the eligibility criteria of our search. In the Results section, we restrict the sample to 145 studies on topics that are of current interest in education.

A significant number of studies were implemented through government channels ( Table 2 ). In addition to the 19% of the studies that examined national policy reforms (such as free primary education), 46% of the 145 studies partnered with government agencies, most often the ministry of education for school construction, teacher trainings or incentive policies; the ministry of health for school feeding; or the relevant government agency for cash transfers. In total, 40% of the studies in our sample worked with non-government organisations such as the BRAC, the World Food Programme, the Aga Khan Foundation or the Twaweza. A smaller number (17 studies) worked with private partners such as for-profit schools, clinics or educational companies. About 15% of the studies did not employ any implementing partner aside from the research teams themselves. Some of these researcher-only studies evaluated smaller, less intensive interventions (e.g., a specific pedagogical technique). More than half of the interventions were evaluated using randomised controlled trials (58% of the studies); the next most common empirical method was difference-in-differences (25%), which was the most common method for evaluating national policies.

Studies According to the Implementing Partner. Private partners include for-profit schools, clinics and educational companies. Some studies have multiple implementing partners (e.g., public–private partnerships that are implemented by both government and private partners)

| . | Count of studies . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Government | 66 | 46% |

| Non-government organisations | 58 | 40% |

| Private partners | 17 | 12% |

| Researchers only | 22 | 15% |

| National policies | 27 | 19% |

| Total studies | 145 | 100% |

| . | Count of studies . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Government | 66 | 46% |

| Non-government organisations | 58 | 40% |

| Private partners | 17 | 12% |

| Researchers only | 22 | 15% |

| National policies | 27 | 19% |

| Total studies | 145 | 100% |

Source: Authors’ calculations based on underlying studies.

A limited number of studies offer cost information ( Table 3 ). Two out of five studies in our sample have no cost analysis at all. About one-quarter provide a full cost-effectiveness analysis, and the others provide limited information on costs, usually only the cost of one specific input, such as a stipend for the trainer or the value of a voucher provided to students. A handful of studies make claims such as an intervention being a ‘cost-effective measure’ or ‘scalable (low-cost)’ without providing any cost details.

Distribution of Cost Analyses within Studies

| . | Count of studies . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Studies with cost-effectiveness analysis | 41 | 28% |

| Studies with quantitative discussion of costs (but not cost-effectiveness) - total program cost | 11 | 8% |

| Studies with quantitative discussion of costs (but not cost-effectiveness) - costs of specific inputs but not the total program cost | 31 | 21% |

| Studies with other claims regarding cost (low-cost, affordable, etc.) but no substantiating data | 7 | 5% |

| Studies with no cost analysis or claims | 55 | 38% |

| Total studies | 145 | 100% |

| . | Count of studies . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| Studies with cost-effectiveness analysis | 41 | 28% |

| Studies with quantitative discussion of costs (but not cost-effectiveness) - total program cost | 11 | 8% |

| Studies with quantitative discussion of costs (but not cost-effectiveness) - costs of specific inputs but not the total program cost | 31 | 21% |

| Studies with other claims regarding cost (low-cost, affordable, etc.) but no substantiating data | 7 | 5% |

| Studies with no cost analysis or claims | 55 | 38% |

| Total studies | 145 | 100% |

In terms of scale, 27 of our 145 studies evaluate national reform policies. For studies that are not national in scale and that report schools as treatment units, we find an average treatment group size of 96 schools (median: 66 schools). There are some larger studies: the 90th percentile includes 211 treated schools ( Carneiro et al. , 2020 ). Table 4 shows the average treatment group size for studies reporting other treatment units such as districts, communities or individuals.

Studies Reporting the Size of the Treatment Group. Other treatment units reported are households (two studies) and classrooms (one study)

| Unit . | Number of studies . | Mean of treated units . | Median of treated units . |

|---|---|---|---|

| National scale | 27 | ||

| Schools | 88 | 96 | 66 |

| Districts/clusters | 7 | 39 | 19 |

| Communities | 8 | 105 | 114 |

| Individuals | 12 | 5,637 | 338 |

| Others | 3 | 845 | 1008 |

| Total studies | 145 |

| Unit . | Number of studies . | Mean of treated units . | Median of treated units . |

|---|---|---|---|

| National scale | 27 | ||

| Schools | 88 | 96 | 66 |

| Districts/clusters | 7 | 39 | 19 |

| Communities | 8 | 105 | 114 |

| Individuals | 12 | 5,637 | 338 |

| Others | 3 | 845 | 1008 |

| Total studies | 145 |

Source: Author calculations based on underlying studies.

In addition to the 19% of the studies that evaluate national policies, almost half of the studies evaluate the impact of a single treatment. The other 35% have multiple treatment arms ( Table 5 ). Twenty-eight studies evaluate two treatment arms, seventeen studies test three treatment arms and six studies test four or more treatment arms. One outlier, Haushofer and Shapiro (2016) , randomised cash transfers to gender of the recipient, frequency of instalment and size of instalment, in addition to the spill-over group (nine treatment arms in total).

Studies Reporting the Number of Treatment Arms

| Number of treatment arms . | Count of studies . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 67 | 46% |

| 2 | 28 | 19% |

| 3 | 17 | 12% |

| 4 | 4 | 3% |

| ≥5 | 2 | 1% |

| National policies | 27 | 19% |

| Total studies | 145 | 100% |

| Number of treatment arms . | Count of studies . | % . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 67 | 46% |

| 2 | 28 | 19% |

| 3 | 17 | 12% |

| 4 | 4 | 3% |

| ≥5 | 2 | 1% |

| National policies | 27 | 19% |

| Total studies | 145 | 100% |

We review the studies in four broad categories. Studies in the first group focus on what happens in the classroom and on policies around the person who manages the classroom—the teacher. These include studies on mother tongue instruction, structured pedagogy and policies around teacher pay and teacher professional development and accountability. Studies in the second group focus on a variety of inputs: school feeding, education technology, school construction and other inputs. Studies in the third group focus on financing: cash transfers, school grants and the elimination of school fees. Studies in the fourth and final group focus on three other topics: early child education, for which there has been little experimental or quasi-experimental evidence in Africa in the past, but for which that literature is growing; girls’ education; and public–private partnerships.

5.1. Teachers and pedagogy

5.1.1. mother tongue instruction.

Mother tongue instruction usually refers to teaching students basic skills in a language that they already know when they arrive at school. In many African countries, the historical norm has been to teach children in a colonial language (e.g., English, French or Portuguese), even though most children arrive at school with little or no ability in that language. 11 Most earlier syntheses have little or nothing to say about mother tongue instruction, but evidence has grown dramatically in recent years ( Appendix Table 3 ). Teaching children to read in a language they speak at home increased the rate at which children learn to read in Cameroon ( Laitin et al. , 2019 ), Kenya ( Piper et al. , 2016c ) and Uganda ( Brunette et al. , 2019 ; Kerwin and Thornton, 2020 ). 12

While impacts on initial reading ability in the mother tongue are promising, the objective of many parents is for their children to be literate in the colonial language, which may explain some of the resistance that parents have posed to mother tongue instruction reforms, as in Kenya ( Piper et al. , 2016c ). Several recent studies suggest that mother tongue instruction has positive impacts on children’s ability to subsequently learn a second language in Cameroon ( Laitin et al. , 2019 ), Ethiopia ( Seid, 2019 ) and South Africa ( Taylor and von Fintel, 2016 ). However, Piper et al. (2018c) find the effect is not as strong: students taught in mother tongue do not perform any better in English and perform worse in mathematics compared with students taught in a non-mother tongue.

Finally, there is some evidence of impact beyond literacy. In Ethiopia, where mother tongue instruction reforms took place in 1994, researchers have identified long-term impacts on educational attainment and civic engagement ( Ramachandran, 2017 ; Seid, 2017 ).

5.1.2. Structured pedagogy

Recent years have also shown growing rigorous evidence for approaches to improve literacy that incorporate a range of elements ( Appendix Table 4 ). Piper et al. (2014 , 2015) used a randomised controlled trial to evaluate a literacy program in Kenya that included teacher professional development, the provision of textbooks for students (including textbooks in Kiswahili), the provision of structured teacher guides for teachers and classroom observation and feedback to teachers, among other elements. The program led to sizeable literacy gains. Seeking to isolate the most important elements of the program, Piper et al. (2018b) find that structured teacher guides are the most cost-effective element of the program. The program was effective at boosting literacy for low-income students ( Piper et al. , 2015 ). The program was subsequently scaled up nationally and continued to demonstrate literacy gains ( Piper et al. , 2018a ). Similarly, a mathematics-focused version of the program provided teacher guides and teacher professional development training and yielded statistically significant improvements in test scores ( Piper et al. , 2016a ).

A combination of training principals and teachers as well as mentoring for teachers and new instructional materials was effective in boosting literacy in Uganda but not in Kenya, potentially because the language of testing was different from the language used in instruction in Kenya, despite national policy ( Lucas et al. , 2014 ). Brunette et al. (2019 ), already discussed in the section on mother tongue instruction, evaluated a program that not only encouraged mother tongue instruction in 12 different mother tongue languages but also provided teacher training, detailed teachers’ guides, textbooks for pupils and feedback from school leaders, resulting in sizeable literacy gains.

Beyond these literacy interventions, many interventions seek to improve the quality of teaching particular skills using a particular method, such as using graphics (e.g., Venn diagrams) in teaching to improve prose comprehension among secondary school students in Nigeria ( Uba et al. , 2017 ). These studies are of value mostly to those seeking to improve the teaching of these specific skills; as such, they are summarised in the appendix but not discussed at length here.

5.1.3. Teacher policies

Teacher remuneration and accountability Because teachers play such an instrumental role in students’ education, recent evidence on high rates of absenteeism and low levels of pedagogical and content knowledge suggests that better teacher policies may be useful to boost education outcomes ( Mbiti, 2016 ; Bold et al. , 2017 ). There is no general pattern in the level of teacher pay relative to comparable professions across Africa ( Evans et al. , 2020 ). There is evidence of a premium to civil service teachers relative to private school teachers ( Barton et al. , 2017 ). A new generation of evidence has arisen on bonus payments for teachers based on student performance. Earlier evidence on performance pay for teachers in Africa was limited and mixed: a randomised trial in Kenya showed that performance bonuses for students increased test scores on the exams directly linked to the incentives, but not on general exams ( Glewwe et al. , 2010 ).

A new generation of studies adds much more to our knowledge base ( Appendix Table 5 ). All these new pay-for-performance programs take place in primary schools. In one study in Tanzania, performance-based bonuses to teachers had positive impacts on student learning in only one of the two tests administered, but when those bonuses were coupled with school grants, students performed consistently better in both tests and across all subjects ( Mbiti et al. , 2019a ). Schools that received grants alone showed no performance gains. Teachers also support these programs in Tanzania, both in theory and in practice, reporting higher levels of satisfaction in schools that have performance pay ( Mbiti and Schipper, this issue ). In Rwanda, a novel experimental design separates the impact of performance pay on recruitment and on effort and finds favourable effects on both, with a significant net increase in student test scores ( Leaver et al. , 2019 ). A pay-for-performance program in Uganda had test score impacts only for the subset of students who attended schools that had books; although it did reduce dropout rates, which were not directly incentivized by the program ( Gilligan et al. , 2019 ). In Kenya, using contracts that are renewable based on performance to hire teachers also boosted student learning ( Duflo et al. , 2015a ); although an effort to scale up those contracts nationwide did not result in learning gains, potentially due to a combination of political opposition, reduced monitoring and delayed salaries ( Bold et al. , 2018 ).

New studies are exploring the nuances of how to implement these programs. In Tanzania, researchers tested two alternative incentive designs: one, a pay-for-percentile system where a teacher’s bonus is based on students’ ranks against other students with similar baseline scores; and the other program, where a teacher’s bonus is based on students achieving benchmark proficiency levels, which the authors argue is easier to implement and gives teachers clearer targets. Both designs boosted test scores, but the latter program had larger impacts at a lower cost ( Mbiti et al. , 2019b ).

Recent evaluations have also shown impacts from non-remunerative accountability interventions. In Côte d’Ivoire, providing twice-a-week text messages to either parents or teachers reduced dropout by between 2 and 2.5 percentage points (about 50% of the dropout rate in control schools). Texting both parents and teachers resulted in a much smaller, statistically insignificant impact. For low-attendance teachers, all three treatments had positive impacts ( Lichand and Wolf, 2020 ). In Tanzania, a nationwide program that simply published school performance on primary school leaving exams led to more students passing the exam among schools that initially performed poorly. However, in an example of how even a low-stakes intervention can also adversely affect behaviours, the program also increased dropouts ( Cilliers et al. , 2020c ). In Niger, a low-stakes, randomised intervention that complemented regular class inspections with phone calls to the village chief, the teacher and two randomly selected students to check on whether adult education classes were being held and how they were going led to improved student learning ( Aker and Ksoll, 2019 ).

Beyond improving performance and accountability, dozens of countries have designed incentive programs to recruit and retain teachers in less attractive teaching posts, and these have had little rigourous evaluation in the past ( Pugatch and Schroeder, 2014 ). Teacher turnover is high in Africa, especially in low-performing schools (Zeitlin, this issue), making teacher retention a policy priority. In Zambia, salary increases of 20% for rural teachers show at least some impact on an increased stock of teachers in beneficiary areas, albeit no impacts on student test scores ( Chelwa et al. , 2019 ). In the Gambia, a salary premium of 30%–40% significantly increased the share of trained teachers in remote areas ( Pugatch and Schroeder, 2014 ). 13 Ultimately, the impact of all of these teacher remuneration interventions—and their relevance to other settings—likely hinge both on existing teacher remuneration relative to other professions and on other aspects of the labour market.

Teacher professional development Another class of teacher intervention seeks to boost their content and pedagogical skills. Earlier reviews showed promising evidence on pedagogical interventions ( Conn, 2017 ), but that is not to say that most teacher professional development programs are effective. On the contrary, the vast majority of at-scale teacher professional development programs in Africa (and elsewhere) go unevaluated in any serious way and many among those do not have the characteristics common to programs that have been shown to be effective ( Popova et al. , 2018 ). Still, recent evidence bolsters the view that teacher professional development—particularly coaching programs—can be effective at boosting student learning outcomes. 14 Importantly, most multi-faceted literacy programs highlighted earlier include teacher training as one aspect of the intervention.

In Ghana, training teachers to target instruction to children’s learning levels by dividing the class by ability group for part of the day increased student learning ( Duflo et al. , 2020 ). In another study in Ghana, training teachers to do targeted instruction (including by dividing students by learning level rather than grade level) increased student scores on a combined Math and English test ( Beg et al. , 2020 ). Adding training for school principals and school inspectors had no additional impact. In South Africa, the government tested traditional, centralised training for teachers versus in-class coaching, with the impact of coaching more than double of that of the centralised training ( Cilliers et al. , 2019 ). In the subsequent cohort of students, only those with teachers who benefitted from coaching show learning gains, although even those are half the size of effects for the first cohort ( Cilliers et al. , 2020a ).

Another teacher training program, combined with partially scripted lesson plans and weekly text message support for teachers, improved teacher practice and children’s literacy ( Jukes et al. , 2017 ). Four trials invested in boosting teacher skills focus on pre-primary education. In Ghana, teacher training for preschool teachers led to small increases in children’s school readiness. When that training was coupled with parental awareness meetings, the outcomes were reversed, potentially because parents preferred traditional teaching over age-appropriate play-based learning in preschool ( Wolf et al. , 2019 ). Attanasio et al. (2019 ) evaluate a program—also in Ghana—that trained volunteer mothers and kindergarten teachers in stimulation and play curriculum; the intervention improved kindergarten children’s cognitive and socio-emotional skills. In Kenya, a combined package of teacher coaching and training, along with instructional materials, boosted learning in early child education centres ( Donfouet et al. , 2018 ). In Malawi, teacher training only boosted outcomes in informal preschools when combined with parent training ( Özler et al. , 2018 ). Finally, a teacher training program in Rwanda designed to complement a new entrepreneurship curriculum in secondary schools did not improve student test scores, although it did boost student participation in school business clubs ( Blimpo and Pugatch, 2020 ).

An alternative strategy is to train teaching assistants to assist teachers. In Ghana, schools were randomly assigned to hire teaching assistants from among the country’s youth employment program to either work with students who had fallen behind during school, work with students who had fallen behind after school or just work with half of the class, thereby reducing class size ( Duflo et al. , 2020 ). All three interventions improved student learning, although the first two had the largest impacts. Interestingly, relative to the Ghana-based, teacher-led targeted instruction intervention mentioned above, the remedially targeted teaching assistant interventions not only doubled the impact on student test scores but also doubled the cost, so cost-effectiveness was comparable.

5.2. Inputs

5.2.1. school feeding.

Just one earlier review highlights school feeding as a possibility for boosting both access and learning ( Snilstveit et al. , 2015 ), and most of the evidence behind that recommendation stems from other regions in the world. Recent evidence from Africa supports that finding ( Appendix Table 6 ). From a randomised evaluation of Ghana’s nationwide school feeding program, Aurino et al. (2019) find gains in test scores as a result of school feeding, with particularly large gains for girls and for children from the poorest households. In rural Senegal, Azomahou et al. (2019) use a randomised design to find gains in both enrollment and test scores from the provision of school meals, as do Diagne et al. (2014) in an earlier evaluation of the same program. Mensah and Nsabimana (2020) exploit staggered implementation of a school feeding program in Rwanda and find small (less than 0.03 standard deviations) but significant impacts on student test scores. Nikiema (2019) uses a difference-in-differences strategy to show that providing take-home rations in Burkina Faso increases school attendance for both boys and girls and increases enrollment for girls in particular. Parker et al. (2015) measure only health outcomes (haemoglobin and anaemia) in a cluster randomised trial of school feeding in rural Burundi and find no clear impacts.

In addition to evaluating the impact of providing school meals, studies are venturing into the details of the meals themselves. Hulett et al. (2014) examine the impact of introducing animal protein into school meals in Kenya with a randomised trial and find that the ‘meat group’ showed higher test score gains than other groups.

These results greatly strengthen earlier global evidence that school feeding is a promising strategy for boosting cognitive outcomes as well as access to school, particularly in food-insecure areas and especially for girls.

5.2.2. Education technology

A previous synthesis that highlighted the promise of education technology ( McEwan 2015 ) draws on evidence from 32 different treatments in five different countries, none of them on the African continent. Recent years have shown a rapid increase in evidence in this area with a mixed track record ( Appendix Table 7 ). 15 In some cases, technology complements existing inputs. In Kenya, researchers experimented with different technology complements (e-readers for students, tablets for teachers or tablets for instructional supervisors): none boosted literacy scores significantly relative to a non-technology-based intervention ( Piper et al. , 2016b ). In South Africa, a randomised trial comparing on-site teacher coaches with virtual teacher coaches (i.e., coaches who communicated with teachers by tablet) led to comparable outcomes in the first year, but over time, the gains from in-person coaches translated to other skills, whereas the gains from virtual coaches did not ( Kotze et al. , 2019 ; Cilliers et al. , 2020b ). A quasi-experimental evaluation of the impact of introducing interactive whiteboards—a complement to teachers—found higher test scores for urban students in Senegal ( Lehrer et al. , 2019 ). De Hoop et al. (2020 ) evaluate a program in Zambia where teachers receive tablets (and projectors) with lesson plans for teachers and interactive lessons for students. Complemented with weekly teacher professional development, the program shows gains for first graders in both reading and math.

In Angola, a randomised controlled trial of learning software together with the technological equipment needed to use the software had no consistent impact on primary school student learning, although it did boost teacher and student familiarity with technology ( Cardim et al. , 2019 ). An experimental evaluation that provided secondary school students in Malawi with access to Wikipedia—the students otherwise had little to no internet access—had small, positive impacts in two subjects but not in others ( Derksen et al. , 2020 ). Also in Zambia, a phone-based literacy game provided to a few hundred randomly selected first-grade students boosted their spelling ability relative to a control group ( Jere-Folotiya et al. , 2014 ). In Kenyan primary schools, interactive literacy software coupled with a library of digital books and stories boosted reading scores ( Lysenko et al. , 2019 ).

In other cases, technology seeks to substitute for other inputs. Providing e-readers to secondary school students in urban Nigeria only increased learning if they included curricular content and were distributed in areas with limited textbook access, essentially substituting e-readers for traditional textbooks ( Habyarimana and Sabarwal, 2018 ). In Ghana, broadcasting live instruction—where students can interact with the instructors—from teachers in the capital to students in rural areas improved literacy and numeracy scores, essentially substituting for teacher ability ( Johnston and Ksoll, 2017 ). Alternatively, technology can fill an input gap in terms of role models: Riley (2019) finds that showing secondary students in Uganda a film featuring a low-income adolescent Ugandan girl succeeding at chess improved student test scores and closed the gender gap in enrollment in subsequent years.

While the findings are certainly not universally positive, they suggest that technology in education can effectively complement or substitute for existing inputs when the infrastructure is in place to support it. This pattern is consistent with earlier evidence ( Bulman and Fairlie, 2016 ). However, most of the technologies evaluated in the studies are used in school settings, with more stable access to electricity and internet connectivity (with the exception of e-readers that students can take home). There is still limited evidence for technology that allows for distance learning where access to school is not available.

5.2.3. School construction